But as the COVID-19 pandemic shows, South Korea – along with all other countries – should resolutely expand the scope of its national security to put non-traditional security dimensions at the center. In a sense, the COVID-19 pandemic further justifies the path South Korea has taken since the end of the Cold War. After all, South Korea is a resource-poor country that depends on international trade to fuel growth.

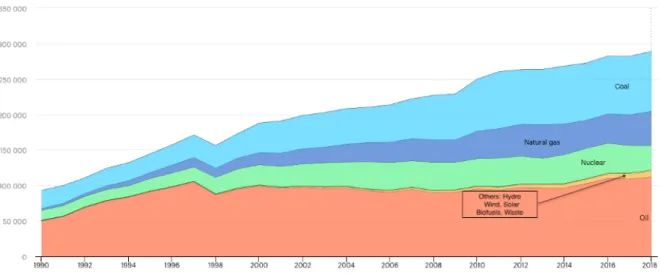

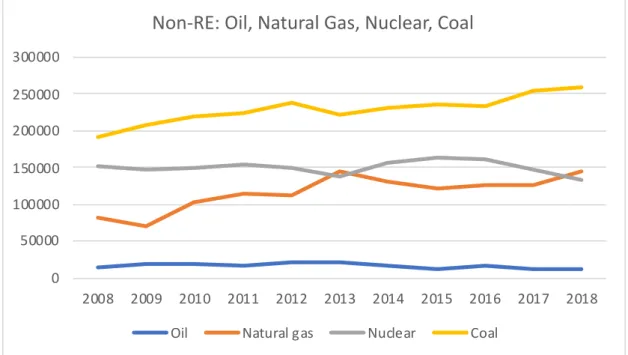

Cyber security has now become the issue of greatest concern for South Korea's non-traditional security. South Korea's traditional understanding of energy security was linked to a stable supply of fossil fuels, which was a prerequisite for the country's economic development. In traditional security areas with relatively clear military fronts, South Korea could contain threats with its conventional forces and the extended deterrence of the United States.

In addition, some countries around South Korea have been accused of not respecting international standards. Thus, it is likely that malicious cyber activities targeting South Korea will increase in the future. According to government figures, North Korea launched at least seven cyberattacks against South Korea between 2009 and 2014, aimed at disrupting South Korean infrastructure.13 There is no clear evidence of any North Korean cyberattack in 2015, according to the South Korean government.

South Korea's cyber security strategy has evolved in four phases, according to the threat posed by North Korea.

ENERGY SECURITY: FROM CRITICAL

INFRASTRUCTURE TO RENEWABLE ENERGY TRANSITION

MARITIME SECURITY: A MIDDLE POWER AMONGST WHALES

While the ocean is important to South Korea, South Korea is also a major player in the global maritime sphere. As a middle power, South Korea has an important role to play in the maritime security of Northeast Asia and beyond. South Korea's maritime security issues – like those of all other countries – encompass both traditional and non-traditional security, but it is important to note that these issues are to some extent intertwined.

For example, illegal fishing by Chinese vessels in the Yellow Sea not only affects the economic security of South Korea's fishing industry, but also the diplomatic relations between Beijing and Seoul. China and South Korea have a dispute over maritime boundaries, and illegal fishing by Chinese vessels has been a contentious issue, resulting in the deaths of Chinese fishermen and South Korean coast guard personnel. South Korea's maritime problems with Japan are political rather than military or economic in nature.

South Korea and Japan both claim Dokdo (known as Takeshima in Japan), small islands in the Sea of Japan or the Baltic Sea, as their territories. Mutual Defense Treaty.”93 A military conflict in the East China Sea or the South China Sea could seriously disrupt the world economy and South Korea's mutual defense treaty. Finally, due to its increased maritime capacity, South Korea has also contributed to maritime security outside Asia.

Geography and an export-focused economy require South Korea to pay close attention to maritime security issues, and the steady increase in South Korea's maritime capacity has led to a growing role for Seoul in this area, as discussed earlier. Furthermore, as in many other policy fields, South Korea's maritime security policy can be characterized as that of a middle power. Seoul therefore has a strong interest in establishing a multilateral international cooperation framework where South Korea – together with other middle powers and smaller states – can mitigate the negative effects of Sino-American competition.

In short, South Korea's maritime security policy has steadily expanded its geographic scope, and all administrations have recognized the increasing importance of the maritime domain. South Korea's maritime security policy, as with many other policy issues, can be characterized by a middle power approach that emphasizes the importance of multilateral and institutional frameworks. As has been the case since the division of the nation after World War II, however, North Korea will continue to cast a long shadow over the future of South Korean maritime security policy.

TRADE SECURITY: ENSURING ECONOMIC SURVIVAL

But the Trump administration is also involved in trade squabbles with allies, including Canada, the EU and Japan, as well as with South Korea.110 Regardless of who wins the upcoming US presidential election, trade tensions between the United States and China are unlikely to go away just like that. As a result, this body became de facto defunct in December 2019.111 South Korea has set up an interim appeals body together with China and the EU. Closer to home, South Korea is suffering from China's economic slowdown and a trade dispute with Japan.

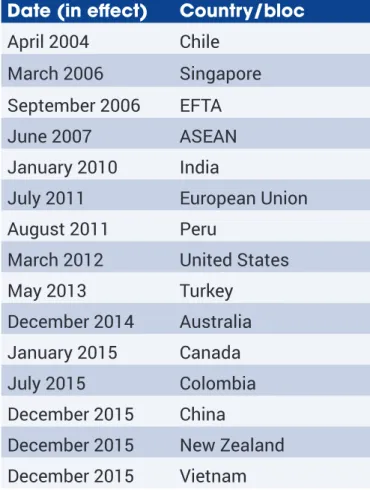

Although the trade conflict has been resolved, it has already affected South Korea's trade trend with its neighbor. The earliest indication of this consensus after South Korea's transition to democracy and the end of the Cold War was that Seoul was a founding member of the WTO.120. South Korea's trade security strategy, which focuses on support for multilateralism but crucially involves a push for bilateral and regional trade agreements that can be traced back to

MOFAT was established between 1998 and 2013,122 which allowed trade to be closely aligned with South Korea's overall foreign policy. Another factor behind South Korea's move toward bilateralism and regionalism was the fear of being "sandwiched" between low-cost China and high-tech Japan. The first strategy has been to appease the Trump administration by renegotiating the South Korea-US bilateral trade agreement (KORUS).

South Korea was the first country to renegotiate its FTA with the United States after Trump's election. The Moon administration has also launched several bilateral FTA negotiations with countries and regions located away from South Korea's immediate neighborhood. Most importantly, the United Kingdom had to make concessions in order to conclude the agreement compared to the provisions included in the EU-South Korea FTA of which London was a part.137.

South Korea already has a free trade agreement with ASEAN and deeper agreements with Singapore and Vietnam. Seoul also has a partnership agreement with India, albeit a very shallow one.140 The Moon administration has reframed South Korea's interest in the region to explain that it is central to the country's future trade security. Diversification of oil and gas supplies is as much a goal as increasing exports to the region, as South Korea is highly dependent on imports from the Persian Gulf.144 The Moon administration's fourth strategy focused on supporting efforts to resolve trade multilateralism.

CONCLUSIONS

China is also a cyber threat and poses a maritime and trade risk to South Korea. Nevertheless, it is important to remember that South Korea's geography determines the types of security threats and the types of issues that Seoul must prioritize. The Moon administration's approach to non-traditional security therefore addresses the long-term threats that South Korea will continue to face in the coming years.

In any case, Moon is helping to strengthen South Korea's national security by building on the policies and strategies of previous administrations and laying the groundwork for future administrations to continue to do so. 8 Terence Roehrig, "South Korea's Anti-Piracy Operations in the Gulf of Aden," in Global Korea: South Korea's Contribution to International Security (New York: Council on Foreign Relations Press, 2012), p. 44 Jane Chung, "South Korea Accelerating Clean Energy Transition, Setting Long-Term Renewable Energy Goals," Reuters, April 19, 2019.

50 World Nuclear Association, 'Nuclear Power in South Korea', Mei 2020, beskikbaar by 79 Terence Roehrig, ‘South Korea: The Challenges of a Maritime Nation’, Analyse van het Maritime Awareness Project, The National Bureau of Asian Research, 23 december 2019, p. 83 Kim Gamel, ‘South Korea to send destroyer to Strait of Hormuz amid tensions between US, Iran’, Stars and Stripes, 21 januari 2020. 87 Min Ye, China-South Korea Relations in the New Era: Challenges and Opportunities (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2017), p. 96 Kim Gamel, "South Korea to send destroyer to Strait of Hormuz amid US-Iran tensions", Stars and Stripes, 21 January 2020. 98 Tongfi Kim, "South Korea's Middle Power Response to China's Rise", ed. Bruce Gilley and Andrew O'Neil, Middle Powers and the Rise of China (Washington, DC: Georgetown University). Press, 2014), p. 99 Ramon Pacheco Pardo, "South Korea holds key to Indo-Pacific", The Hill, 18 August 2019; US Department of State, A Free and Open Indo-Pacific: Moving Forward a. 117 Choe Sang-Hun, 'Sydkorea retaliates Against Japan in Trade and Diplomatic Rift', The New York Times, 12. august 2019. Sydkorea-Kina Economic Relations and the Political (Non-)Divide', i Marco Milani, Antonio Fiori og Matteo Dian (red.), The Korean Foreign Political, South Korean Foreign Policy: Korean Foreign Political, South Korean Foreign Policy: Korean Foreign Political. 2019), s. BEYOND TRADITIONAL SECURITY SOUTH KOREA’S POSITIONING TOWARDS THE CYBER, ENERGY, MARITIME AND TRADE SECURITY DOMAINS