Most of these children are teenagers and many of these teen migrants are girls.1 The age of young migrants is critical because as they include teenagers and especially those who are legally children, policy and popular discourse undergo a marked shift. Girls are invisible in both quantitative and qualitative studies.2 The few existing academic studies are mainly of domestic workers in Africa (Erulkar 2006; Erulkar and Mekbib 2007) and Southeast Asia (Camacho 2006; Guo et al. 2011). or occasionally of sex workers. (Van Blerk 2008).

Locating girls’ and women’s migration to Sudan

Over the past decade, a number of international organizations and Ethiopian researchers have studied the migration of Ethiopian women to the Middle East (Kebede 2001; ILO 2011; Minaye 2012; Reda 2012). Most young Ethiopian women work in the informal sector in Sudan, as housekeepers, tea sellers or waitresses in restaurants.

City as a space: Khartoum: a multi-face city

Fighting still rages in the Nuba Mountains and tensions simmer in the east and west of the country. A large number of internal migrants and displaced people reside throughout the city, although mostly in the shantytowns.

Migration policies and regulations Main regulations

Much of the discourse and policies at national, regional and international levels in Sudan regarding migration issues focus on combating human trafficking and smuggling in the region. Sudan is the leader of the "EU-Horn of Africa Migration Route Initiative" called the Khartoum Process.

Specific regulations affecting adolescent girl migrants The Child Act

The act must be considered to be contrary to public morality if it is considered so in the religion of the performer or the custom of the country where the act takes place. The Habash girls, are perceived as not being 'human' in the same way that Sudanese girls and women are.

3 Methods and Fieldwork

Research methods Survey questionnaires

Two of the FGDs included groups of girls who had come in the last five years, and one included girls who had come more than five years earlier. I also conducted five in-depth discussions with family members of Eritrean migrant girls.

Constraints and limitations

One of the main ethical considerations I had was the impact of the research on the young women who worked as research assistants on the project. Two of the research assistants became very active in helping their own communities and identifying those in urgent need of help.

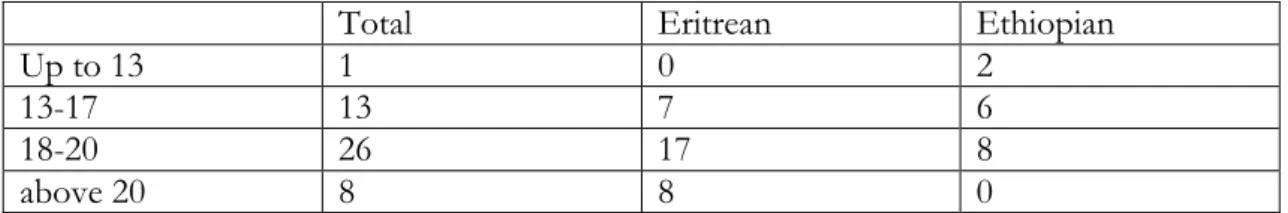

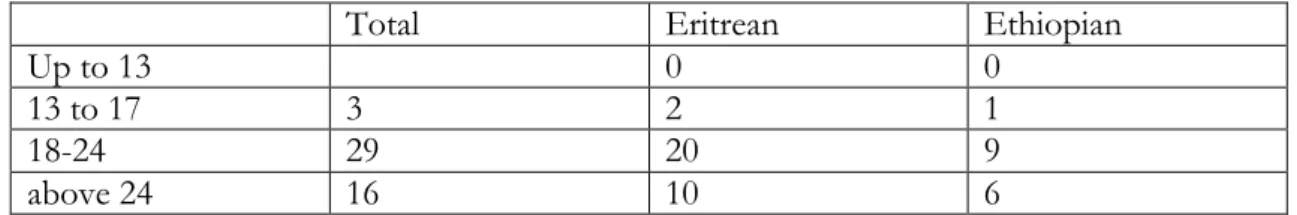

4 Social Profile of Respondents

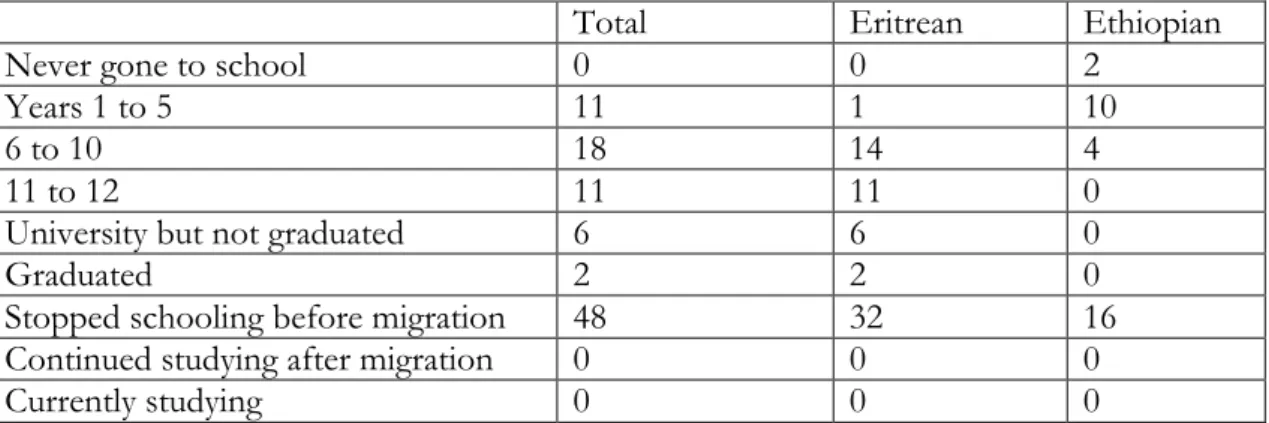

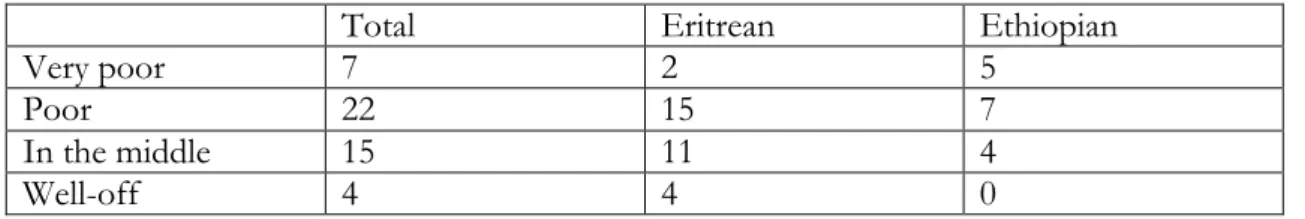

We were very poor and the situation got worse because of the economic crisis in Ethiopia. Among the Eritrean respondents, there were two younger girls (16 and 17) who were interviewed for life stories, who continued education on arrival in the country. Lack of sufficient financial means, long working hours, prevailing insecurity of traveling through the city at night and lack of evening classes made it impossible for many of the migrant and refugee girls to continue their education in Khartoum.

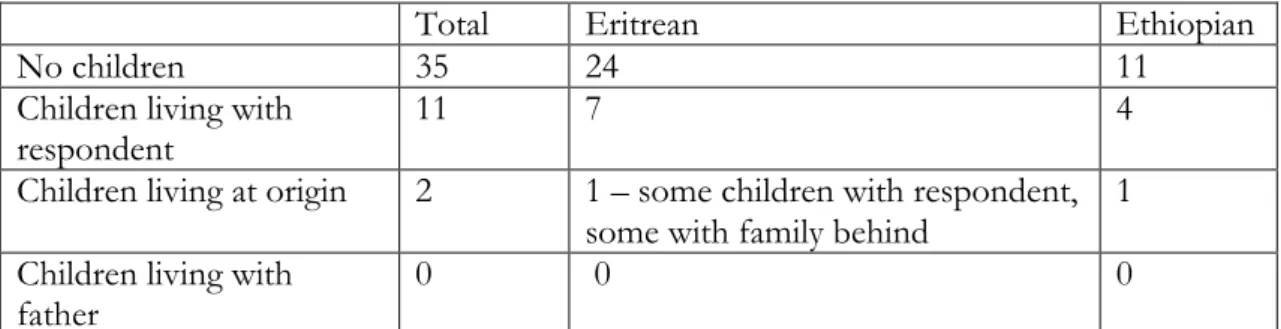

However, since the time of the survey, two more Eritreans and one Ethiopian girl have married. For the Eritrean girls and young women, marriage to Eritrean men who were either abroad in Europe or in North America was one of the strategies to continue their migration project. The majority of respondents both in the survey and in the life stories had no children.

5 Becoming a Migrant

- Migration motives

- Beyond ‘poverty and human rights discourse’ as reasons for migration Eritrea: no choice

- The gender order and gender norms

- Family circumstances

- Decision to leave

- The journey

I am the eldest in the family and they think this is my role. This also points to the general trend of increasing poverty, economic uncertainty and increasing volatility in the lives of poor and very poor families. In short, family circumstances were an important aspect in the girls' decision to migrate.

However, a number of Ethiopian and Eritrean girls who decided to come to Sudan did not know anyone in the country. But she was deeply traumatized and some Eritrean women in the camp helped her get to Khartoum. With the government's sweep-out, migrants no longer show up at the clinic, and the temporary shelter built for migrants in the middle of the city stands idle.

6 Being an Adolescent Migrant Girl in Khartoum

- First impressions and first encounters

- Settling in and living situation

- Working and earning

- Educational opportunities and aspirations

- Life in the city

- Risks, threats and set-backs Violence and death: If the desert could speak…

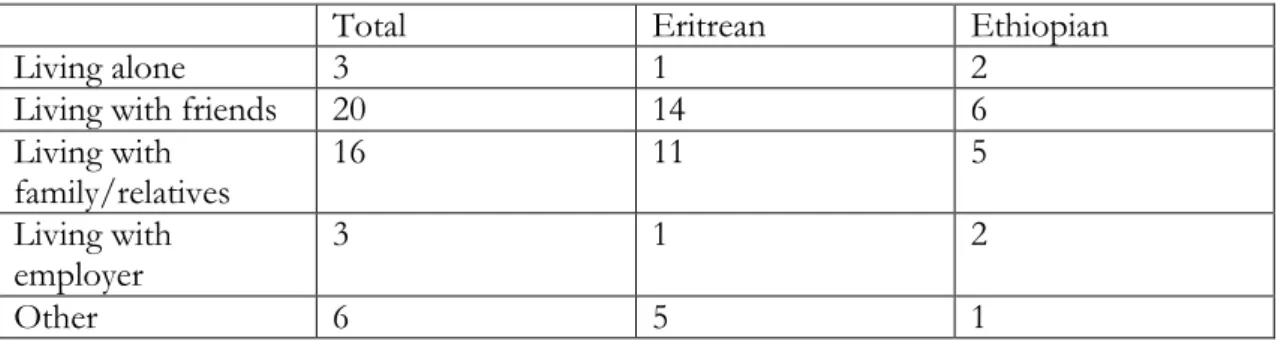

Most of the respondents told me that their living conditions in Eritrea are not that bad. In some cases, when the brothers of some respondents arrived in the city, the girls had to look for different ones. Rahel, who lives in one of the rooms, told me: 'I didn't know these people before.

This is one of the favorite moments for one of my researchers who belonged to the Church. Then they left her naked in the middle of the square in one of the popular neighborhoods. One of the other negative consequences of migration has been the detrimental impact on the health of girls and young women.

7 Vulnerability, Volatility and Protection

Sources of vulnerabilities

The precarious and unstable legal status in the country is also further undermined by the weak rule of law and deep-rooted corruption in the police and security forces. Low levels of education and lack of Arabic language skills are other sources of vulnerability for Ethiopian and Eritrean girls and young women. Newcomers to the country find it particularly difficult to navigate the city's dangerous and uncertain terrain.

Limited institutional support from their community organizations, international and national organizations, the Sudanese government, and in the case of Ethiopians, the embassy further marginalizes adolescent girls and young women. For Ethiopians, the meager income and lack of money for a return journey made it difficult to return. Even those who had been in the city longer (6-8 years) saw their lives as unstable and unsafe.

Volatility

Genet, an 18-year-old from Gondar had to stop working for a week at her tea stall. These uncontrolled terrains and spaces leave the girls at the mercy of their employers and clients. The perceived lack of options and the inability to return to their countries of origin further increase girls' vulnerability.

They worked as cleaners and coffee makers in one of the companies in Khartoum. Meanwhile, Sanayit has already given up her room because she thought she would soon move to Switzerland. This was especially true due to the difficult situation of adolescent and young migrant women as outside their protective environment, which reinforced the fragility and uncertainty of their lives.

Sources of support and protection

Most of the people hoped to go further to change their lives and to be able to enjoy them in. For example, one of the Pentecostal chapels rents a guest house and accommodates people who have just arrived in the country. However, none of the Eritrean girls who participated in the research were even aware of the presence of UNHCR in Khartoum.

In fact, IOM asked our research team to provide information on the lives of new migrants in the city. This is one of the few organizations. especially helping migrant and refugee girls and women. At the time of the interview, there were about seven women staying in the shelter, most of them with small children.

8 Transitions and Intersections

- Waiting in an ‘inbetween place’: mobility and immobility

- Alternative youth identities and transitions

- Marriage and migration

- Girls’ aspirations and evaluations of their lives

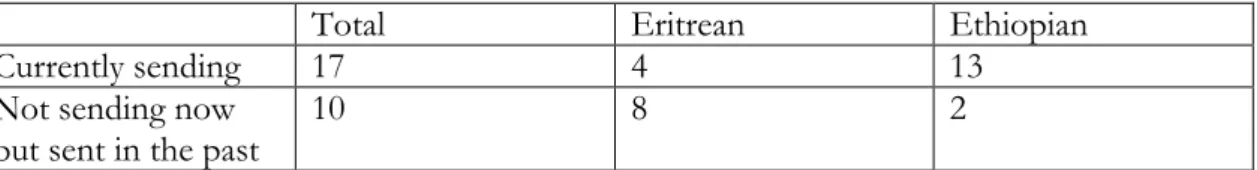

- Supporting those left behind: remittances, investments, emotions

- Long-term aspirations

When asked about their experiences in Khartoum, most girls and young women spoke of "no change". Most of the girls talked about how the experience of escaping from Eritrea brought changes in their lives. These observations should not diminish the seriousness of the suffering of girls and young women caused by migration and the situations in which they find themselves.

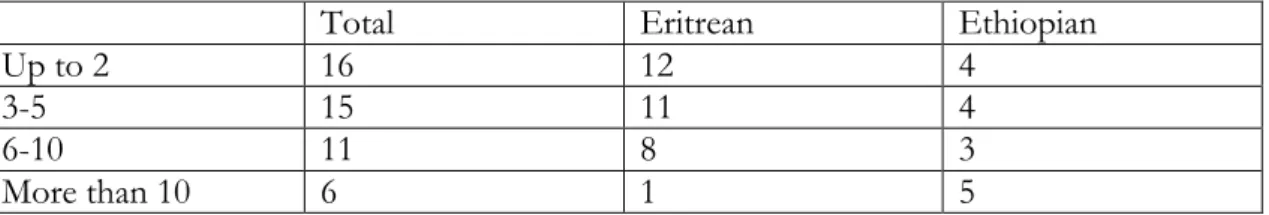

Due to limited data (difficulties in finding Eritrean respondents who have been in Khartoum for more than ten years, and the limited number of interviews with Ethiopians), it is not possible to make a broader analysis of long-term changes in the life cycle of new immigrants. Another dimension of the lives of young migrant and refugee girls and women in Khartoum was maintaining contact with those left behind. However, the direct difference in terms of improving the lives of girls and their families is quite minimal.

9 Key Implications for Policy and Interventions

- Addressing triggers of migration

- Protection and safer migration

- Provision of information for potential migrants in Ethiopia (and Eritrea)

- Safer migration experience in Sudan

- Raising the profile of young female migrants in Sudan

Third, issues of violence against girls and women must be addressed at the national level and at the level of Sudan's migrant communities. Campaigns against domestic violence should be organized with local organizations (such as SIHA and SEEMA) and with migrant communities (via migrant groups, churches and other religious institutions). Existing anti-trafficking laws in Sudan need careful review to keep the interests and protection of adolescent girls and young female migrants at the center.

First, better information should be available to adolescent and young migrant women upon arrival in Sudan. Both general and targeted specialized education should be provided to those girls and young women who wish to continue their studies. The needs and special circumstances of girls and young women, including their reproductive and sexual health, should be emphasized.

2006 Children and Migration: Understanding the Migration Experiences of Child Domestic Workers in the Philippines, The Hague: Institute for Social Sciences. 2004 Constructing 'New Ethnicities': Media, Sexuality and Diasporic Identity in the Lives of South Asian Immigrant Girls, Critical Studies in Media Communication. 2007 "Invisible and Vulnerable: Adolescent Domestic Workers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia", Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies.

2015 “Urban agriculture in the face of land pressure in Greater Khartoum: The case of new real estate projects in Tuti and Abū Seʿīd”, in Barbara Casciarri, Munzoul A.M. 2014 Rethinking Girls on the Move: The Intersection of Poverty, Exploitation and Violence Experienced by Ethiopian Adolescents Involved in the Middle Eastern 'Maid Trade', London: Overseas Development Institute. 2000 "Resistance, Displacement and Identity: The Case of Eritrean Refugees in Sudan", Canadian Journal of African Studies.