FUNDAÇÃO GETÚLIO VARGAS

ESCOLA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO DE EMPRESAS DE SÃO PAULO

LETÍCIA GERA GOUVÊA DE ALBUQUERQUE

DEBT MATURITY DETERMINANTS IN BRAZIL: EVIDENCE FROM

PRIVATE AND PUBLIC CORPORATE BORROWINGS

LETÍCIA GERA GOUVÊA DE ALBUQUERQUE

DEBT MATURITY DETERMINANTS IN BRAZIL: EVIDENCE FROM

PRIVATE AND PUBLIC CORPORATE BORROWINGS

Dissertação apresentada à Escola de Ad-ministração de Empresas de São Paulo da Fundação Getúlio Vargas, como requisito para obtenção do título de Mestre em Administração de Empresas Campo de Conhecimento:

Finanças Corporativas

Orientador: Prof. Dr. Richard Saito

Albuquerque, Letícia Gera Gouvêa de.

Debt maturity determinants in Brazil: evidence from private and public corporate borrowings / Letícia Gera Gouvêa de Albuquerque. - 2015. 32 f.

Orientador: Richard Saito

Dissertação (mestrado) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo.

1. Dívida externa - Brasil. 2. Debêntures. 3. Estrutura de capital. 4. Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social (Brasil). I. Saito, Richard. II. Dissertação (mestrado) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo. III. Título.

LETÍCIA GERA GOUVÊA DE ALBUQUERQUE

DEBT MATURITY DETERMINANTS IN BRAZIL: EVIDENCE FROM

PRIVATE AND PUBLIC CORPORATE BORROWINGS

Dissertação apresentada à Escola de Ad-ministração de Empresas de São Paulo da Fundação Getúlio Vargas, como requisito para obtenção do título de Mestre em Administração de Empresas Campo de Conhecimento:

Finanças Corporativas

Orientador: Prof. Dr. Richard Saito

Data de Aprovação:

/ /

Banca examinadora:

Prof. Dr. Richard Saito (Orientador) FGV-EAESP

Prof. Dr. Paulo Renato Soares Terra FGV-EASP

Acknowledgements

I would like to express the deepest appreciation to my supervisor, Dr. Richard Saito, to my committee members, Dr. Paulo Renato Soares Terra and Dr. João Zani and to the always helpful Dr. Rafael Felipe Schiozer.

I would also like to thank my colleagues at FGV, Adalto, Marcelo, Carlos Eduardo, Lucas, who have been incredibly collaborative and willing to share their knowledge.

Thanks also to my colleagues and professors at HEC Paris, for often keeping me motivated and inspired.

I am grateful to all the people at FGV who helped me one way or another: Pâmela, for her empathy and solicitousness; Maria Tereza; Luciana Gelain; Marta; among others.

I cannot thank these people enough for their time and generosity. I am also grateful for the support of CAPES.

RESUMO

Este trabalho investiga empiricamente os determinantes de prazo de dívida no Brasil. Nós construímos uma base de dados que inclui dívida privada e pública de 308 empresas brasileiras não-financeiras listadas em bolsa, de 2009 a 2013. Utilizamos uma análise GMM utilizando como variáveis explicativas os montantes de dívida de longo prazo a pagar em mais de um, três e cinco anos, para dívida total, dívida BNDES (Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social) e debêntures. Os resultados indicam que o BNDES financia firmas menos arriscadas, ou seja, maiores, mais antigas, mais tangíveis e mais transparentes. Também encontramos suporte para teorias de assimetria de informação, dado que firmas com maiores níveis de transparência apre-sentam níveis similares de alavancagem ao de firmas em outros segmentos, porém uma proporção maior de dívida de longo prazo em suas estruturas de capital. Quanto aos níveis de dívida, ob-servamos que firmas mais alavancadas são maiores, menos lucrativas, mais tangíveis e possuem menos oportunidades de crescimento. Acreditamos que este é o primeiro trabalho a abordar deter-minantes de endividamento de longo prazo com diversas medidas de longo prazo e com diferentes tipos de dívida.

ABSTRACT

This study provides an empirical investigation of the determinants of long-term debt maturity in Brazil. We built a unique database that includes privately placed debt and public debt for 308 publicly traded, non-financial Brazilian companies, from 2009 to 2013. We perform GMM panel analyses using as dependent variables the amount of long-term debt payable in more than one, three, and five years for total debt, BNDES (Brazilian Development Bank) debt and corporate bonds. The results show that the BNDES finances less risky firms, i.e., those that are larger, older, more tangible and more transparent. We also find support for information asymmetry theories, as companies with higher transparency levels have similar leverage levels relative to others but higher proportions of long-term debt in their capital structures. Regarding debt levels, we find that more levered companies are larger, less profitable, more tangible and have fewer growth opportunities. To our knowledge, this is the first paper to address the determinants of long-term debt maturity in Brazil that uses various specifications of long-term debt and that examines different types of debt.

Contents

INTRODUCTION . . . . 11

1 LITERATURE REVIEW . . . . 14

2 DATA, DESCRIPTION OF VARIABLES AND UNIVARIATE ANALYSES 16 3 EMPIRICAL ANALYSES . . . . 26

3.1 Total Debt Levels . . . 27

3.2 BNDES debt . . . 27

3.3 Corporate Bonds . . . 28

3.4 Comparative analysis . . . 28

4 CONCLUSION . . . . 31

List of Tables

Table 1 – Summary Statistics, BNDES Debt and Corporate Bond Maturities . . . 17

Table 2 – Summary Statistics of Leverage by Industry . . . 17

Table 3 – Descriptive Statistics of Explanatory Variables . . . 20

Table 4 – Summary Statistics of Debt Maturity by Trading Levels . . . 21

Table 5 – Correlation Matrix . . . 22

Table 6 – Characteristics of Firms Trading on NM Level and Other Levels . . . 23

Table 7 – Debt Maturity in Firms Trading in NM Level . . . 24

Table 8 – Debt Maturity in Firms with a 50% Blockholder . . . 25

11

INTRODUCTION

Brazilian companies operate in a rather anomalous financial and economic environment. Brazil’s legal tradition has led to an underdeveloped financial market, which, in turn, stimulates informa-tion asymmetries and induces aggregate players to behave in particular ways. For instance, the proportion of long-term debt in firms’ debt structures is remarkably lower in Brazilian firms than in U.S. firms (BARCLAY; SMITH, 1995) (BENMELECH, 2006). In our sample, approximately 29 percent of firms’ debt is short-term debt, but only 11 percent of total debt matures in more than five years1. Notably, Brazilian firms have highly concentrated ownership, small boards of directors,

and face an environment of higher information asymmetry and limited availability of long-term credit. We aim to shed light on the determinants of debt maturity choice in such an environment and to investigate whether different types of debt have particular sets of determinants.

In addition to analyzing firm characteristics such as size, receivables and tangibility, we also examine the relationship between corporate governance and long-term leverage levels, and we expect to find differences in the debt structure choices of more transparent firms. When going public in Brazil, firms can choose the level of corporate governance that they wish to trade on; that is, they can choose how much information they want to disclose beyond what is legally required. Novo Mercado (NM) stands for the highest level, and firms trading on that level must comply with certain rules, such as including minority shareholders on the board, enforcing a one-year mandate for board members, establishing an arbitrage board and not issuing preferred shares2. We add a

dummy variable that equals one if a company trades on NM and zero otherwise to proxy for higher standards of corporate governance. We expect companies with better governance and broader disclosure to mitigate information asymmetries and, consequently, to be more levered because lenders would be more willing to offer loans. We find that the differences between groups of companies trading on NM and on other levels are pronounced and are significantly different from zero. Theoretical models expect high-quality firms to have more short-term debt, but because NM firms are more transparent, they reduce asymmetry and are able to add more long-term debt to their capital structures without suffering the harmful effects of the market’s pooling equilibrium. Therefore, if there is indeed an impact of reduced asymmetry in debt maturity choices, we would expect it to increase long-term debt.

We find that the trade-off theory also does not fully explain leverage levels in Brazil, but it could explain long-term leverage. Because bankruptcy costs are higher and tax benefits are

1 Benmelech (2006) finds 76.2 percent of debt maturing in more than one year and 44.37 percent of debt

maturing in more than five years for a sample of U.S. firms.

2 In Brazil, it is possible to issue dual-class shares. In short, ordinary shares provide the right to vote, while

12

lower, we should expect to see lower leverage levels than those reported in the United States. In addition, Brazil’s legal origin offers little legal protection for creditors and minority shareholders, so capital markets were not able to develop as well or as broadly as those in countries with better protections, which jeopardized not only the development of the equity market but also that of debt markets. This characteristic strengthens families and the government’s role in the corporate environment(PORTA et al., 1997), and it is one of the reasons why these two institutions are dominant in the Brazilian market. The presumably risk-averse nature of these types of shareholders induces us to expect low leverage. Furthermore, high taxes make levering up even less attractive. However, we find similar leverage levels for Brazilian companies to those in the U.S.(FLANNERY; RANGAN, 2006). Porta et al. (1997) finds that common law countries offer firms better access to equity financing, which adds to the explanation of why Brazilian firms have higher leverage levels. When it comes to long-term debt, however, leverage levels in Brazil are remarkably lower, which leads us to infer that Brazilian firms take on much more short-term debt and little long-term debt. Asymmetric environments lead firms to issue short-term debt instead of long-term debt, as we explain in the literature review section, and also to rely more heavily on bank debt. Banks, in turn, prefer to offer short-term debt under asymmetric settings because it gives them more bargaining power over firms’ projects.

In addition to analyzing total long-term debt, we examine BNDES debt and corporate bonds separately. The BNDES is the Brazilian Development Bank, which is Brazil’s main long-term financing agent3. We add it to our analysis because of its economic relevance, given that it is

currently the main source of long-term financing for Brazilian firms. In 2010, BNDES disburse-ments reached R$ 168.4 billion and R$ 190.4 billion in 20134. In our sample, BNDES debt alone

accounts for an average of 13% of firms’ debt.

Thus, what firm characteristics determine long-term debt levels in Brazil? Is there a distin-guishable pattern of characteristics that leads firms to prefer a specific creditor over another? Using a sample of 308 publicly traded companies on the Brazilian stock exchange, we find that firms with lower asymmetry have more BNDES debt in their portfolios. Firm size is an important determinant of corporate bond issuance. An increase of 1% in firm size amounts on average to an increase of 6.2% in long-term bond payables. In line with the previous literature, we also find that more levered firms are larger, more tangible, less profitable and have fewer investment opportunities.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to address the determinants of the maturity of different types of debt in Brazil and also to consider several specifications of long-term debt (debt maturing in more than one, two, three, four and five years). It also adds to the empirical literature by 1)

13

using a new dataset, and 2) focusing on an underdeveloped financial market with high ownership concentration and few long-term financing options, as in the Brazilian market. Long-term debt maturity, with its various definitions5, has not yet been extensively studied because this information

is, although public, not available in any database.

Our dependent variable specification follows that of Barclay and Smith (1995) – debt maturity as the ratio of long-term debt to total debt – which allows us to separate debt maturity from leverage and obtain a more precise understanding of the maturity decision. As explanatory vari-ables, we employ variables that describe management characteristics, such as board features and ownership structure, as well as standard firm features, such as size, tangibility, and age, among others. Our methodology of choice is the GMM estimation, which provides the best fit for our model, as we explain further in the Regression Analysis section.

This paper relates to the literature on capital structure, with a focus on debt maturity. We extend the empirical analysis performed in previous studies(BENMELECH, 2006)(CÉSPEDES; GONZÁLEZ; MOLINA, 2010) by examining the maturity structure of debt in Brazil instead of only leverage levels by applying robust methodologies and by employing various measures of long-term debt. Additionally, we also extend the previous literature by analyzing the delong-terminants of BNDES debt and corporate bond maturities separately.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents a brief literature review with a discussion of previous findings on debt maturity and related subjects. Section 3 describes our data and presents the summary statistics of our sample. Section 4 provides our results on the determinants of debt maturity. Section 6 concludes the paper.

5 The conventional accounting notion of long term is debt maturing in more than one year. Barclay and Smith

14

1 LITERATURE REVIEW

Many studies have addressed the determinants of debt maturity; however, the majority of them focus on firms in developed economies, especially the U.S. First, firm size is widely taken as one of the main determinants of debt levels and debt maturity. Titman and Wessels (1988) argue that small firms prefer to short-term borrowing because long-term debt implies larger fixed costs. In addition, larger firms are more exposed and therefore have lower asymmetric information, which leads us to expect easier access to long-term debt and, consequently, longer debt maturities (ANTONIOU; GUNEY; PAUDYAL, 2006). Larger firms are usually also more diversified, which reduces risk. Barclay and Smith (1995) relate larger firms with lower market-to-book values to more long-term debt. In states in which there are contracting frictions, tangible assets should facilitate borrowing because creditors can repossess such assets in case of bankruptcy, so tangibility is another main determinant of debt choice(RAJAN; ZINGALES, 1995). Growth opportunities, proxied by the market-to-book ratio, has also been cited as an important determinant of capital structure. Barclay and Smith (1995) use this variable in their estimations but admit that it is a noisy proxy and employ it only as a specification check on an alternative measure using R&D data. They find, through both specifications, that firms with more growth opportunities take on more short-term debt. Profitability is also widely accepted for having an impact on leverage(BARCLAY; SMITH, 1995)(BENMELECH, 2006)(CÉSPEDES; GONZÁLEZ; MOLINA, 2010).

Another paradigm of determinants of corporate debt choices is the trade-off theory. Regarding debt levels, trade-off theory leads us to believe that Brazilian firms should be less levered because 1) the tax benefits are lower and financial distress costs are higher(BENMELECH, 2006), 2) macroeconomic uncertainty should also act to restrain firms’ financing options, and 3) a lack of diversification should increase shareholders’ aversion to debt. Conversely, however, given the high ownership concentration in Brazil relative to developed markets, shareholders can maintain their decision-making power and refrain from dispersing their ownership, so they may therefore prefer debt over equity issuance, as conjectured by Céspedes, González and Molina (2010).

15

manager and owner but instead between majority and minority shareholders. This environment makes Jensen’s (JENSEN, 1986) conception of debt as a monitoring mechanism not suitable.

We expect to observe some conflicting results when comparing studies that use samples of firms in developed economies with those whose samples are composed of firms operating in less developed economies. For instance, Demirgüç-Kunt and Maksimovic (1999) finds that firms in more developed economies have more long-term debt and a higher proportion of their outstanding debt as long-term debt. Systematic differences in the enforceability of contracts, the size of the banking sector and the development of the financial and legal sectors themselves shape the choice of debt and of debt maturity in distinct ways. Kirch and Terra (2012) find, through a cross-country study of South American firms, that the institutional quality of a country is a significant determinant of debt maturity decisions but the level of financial development is not, most likely because the latter is in fact an outcome of the former. This environment favors increased asymmetry between the different players in the market in a vicious cycle.

Given the high levels of asymmetric information in Latin American financial markets (CHONG; SILANES, 2007), we pay special attention to this paradigm. According to Flannery’s model (FLANNERY, 1986), in the presence of asymmetric information, lenders are unable to distinguish good borrowers from bad borrowers, so the market adjusts itself into a pooling equilibrium, and consequently, bond coupon rates end up reflecting average borrower quality. However, debt maturing in t=1 would be riskless; therefore, there is no default premium. Under this setting, good borrowers maximize value by issuing short-term debt and bad borrowers do so by issuing long-term debt. Good firms also issue short-long-term debt because they are likely to have few constraints to extending their level of debt. As a result, debt maturity decisions could work as a signaling device of company quality, and bad borrowers should issue short-term debt to mimic the behavior of good-quality firms. As a result, if this signaling hypothesis stands, there should be a high proportion of short-term debt in markets with asymmetric information because both good and bad borrowers choose short-term debt. In a previous work that uses a similar rationale, Barnea, Haugen and Senbet (1980) argue that short-term debt eliminates the agency problem of asset substitution, as does the issuance of callable debt.

16

2 DATA, DESCRIPTION OF VARIABLES AND UNIVARIATE

ANALY-SES

To conduct our tests, we use data from two sources. Accounting data are derived from Econo-matica. We disregard observations from financial institutions and utilities companies. All of the information concerning debt maturity was hand-collected from firms’ annual filings. This information is reported in the footnotes of the firms’ reports and is not available in any database. It was not until 2010 that the Securities and Exchange Commission of Brazil, the CVM, required companies to fulfill the Formulário de Referência, the broadest of their required filings. This report provides extensive information about firms’ risks and operations, thus increasing transparency. Because our regressions include corporate governance data that are only available in this report, our data cover the period from 2009 to 2013. Our final sample consists of 308 companies and 1,540 firm-year observations.

Our dependent variables are defined as the proportion of debt maturing in more than one, three and five years relative to total debt(BARCLAY; SMITH, 1995)(BENMELECH, 2006)(AN-TONIOU; GUNEY; PAUDYAL, 2006). We apply the same methodology for BNDES debt and for corporate bonds.

Our Novo Mercado Dummy equals 1 if a firm trades on the Novo Mercado level and zero otherwise. Size is defined as the natural logarithm of total assets. Profitability is defined as EBITDA over total assets. Tangibility is the ratio between fixed assets and total assets. Market to Book is the market value of equity plus the book value of assets minus the book value of equity. Receivables is defined as total receivables divided by total assets. Board size is the number of directors on the board. The percentage of independent directors is the ratio of the number of independent directors over the total number of directors. CEO Tenure is the log of the number of years in office of the CEO. Firm age is the log of the number of years since the firm’s founding.

Table 1 reports the distribution of the debt maturities for total debt, BNDES debt and corpo-rate bonds, from one to five years. The average amount of debt maturing in more than one year is approximately 71 percent of total debt, 30 percent in more than three years and 11 percent in more than five years. BNDES debt represents approximately 13 percent of firms’ long-term debt, which is approximately the same amount as corporate bonds. On average, approximately 9 percent of debt maturing in more than three years is from bonds and 6 percent of it is from the BNDES.

17

Table 1 – Summary Statistics, BNDES Debt and Corporate Bond Maturities

This table reports descriptive statistics for BNDES, bonds and total long-term debt. The variables are the ratio of BNDES, corporate bonds and total debt maturing in more than one, two, three, four and five years to total debt. Data were obtained from companies’ reports and Economatica.

BNDES Debt Corporate Bonds Total Debt

% Debt Maturing in More than Mean St. Dev. Mean St. Dev. Mean St. Dev.

One Year 0.1302 0.2158 0.1375 0.2673 0.7107 1.749

Two Years 0.0880 0.1875 0.1147 0.2565 0.5925 1.405

Three Years 0.0619 0.1708 0.0933 0.2349 0.3873 0.936

Four Years 0.0569 0.1708 0.0737 0.2135 0.2237 0.553

Five Years 0.0516 0.1675 0.0532 0.1947 0.1114 0.2698

Source: Authors.

meet their expenditure needs and to boost income generation. Electronics, Telecommunications and Software are the least levered sectors, which is in line with the theory because we expect companies with higher information asymmetry, as in the case of firms in the latter sectors, to be less levered.

Table 2 – Summary Statistics of Leverage by Industry

This table displays the summary statistics of our sample. The sample consists of 308 firms, all of which trade on the BMF&Bovespa, the Brazilian stock exchange. We exclude financial and utilities firms. Leverage is defined as the ratio of total debt to total assets.

Mean (%) Median St. Dev. Firms

Industrial 40.38 0.464 0.148 5

Transportation & Carriers 36.64 0.398 0.164 18

Auto & Auto parts 35.31 0.383 0.156 15

Pulp & Paper 33.20 0.388 0.168 5

Agricultural 33.09 0.363 0.188 4

Food & Beverage 30.34 0.334 0.155 16

Chemical 28.70 0.347 0.164 9

Building materials 28.68 0.263 0.169 4

Homebuilders 28.36 0.296 0.149 23

Steel 27.68 0.258 0.161 21

Textiles 25.96 0.259 0.172 23

Retail 24.37 0.243 0.243 18

Mining 18.09 0.196 0.139 5

Other 16.64 0.112 0.178 93

Software 16.45 0.193 0.118 5

Telecommunications 16.39 0 0.150 13

Oil & Gas 15.05 0.251 0.174 7

Electronics 14.78 0.148 0.180 7

Source: Authors.

18

Molina (2010) find a 29 percent ratio for Latin American firms, whereas we find a 23 percent ratio for our sample of Brazilian firms. Table 5 shows the correlation matrix of the variables.

Next, we split our sample between firms trading on the Novo Mercado level and firms trading at other levels. Table 4 shows descriptive statistics of long-term debt for both groups. NM firms and firms on other levels have similar amounts of debt maturing in more than one year, but the difference is pronounced for debt maturing in more than two years. NM firms have approximately 55 percent of their debt maturing in more than two years, and firms on other levels have 41 percent. The amount of debt maturing in more than four years is higher for NM firms, but the difference is much less distinct. These initial remarks lead us to hypothesize that trading on the Novo Mercado level reduces the problem of suboptimal decisions - and, in this particular case, capital structure decisions - due to the firms’ public exposure, which reduces asymmetry in an environment with high information asymmetry.

19

eyes of lenders, most likely due to reduced information asymmetry.

Next, we compare the characteristics of firms trading on NM to those of companies trading on other levels. As reported in Table 6, we find that firms trading on NM are more levered. This result could be due to either better financing strategies or, even prior to that, better credit supply. T-tests show that the differences between groups are significantly different from zero. Univariate evidence indicates that NM firms are consistently larger, less profitable, younger, and less tangible and have more growth opportunities, larger boards, more independent directors on the board, CEOs with shorter tenure, more receivables and less concentrated ownership. These characteristics suggest that an NM dummy is a good proxy for better governance, as these differences are related to a reduction in agency problems.

We perform means tests, which are reported in Table 7. They show that in most periods, the debt maturities of Novo Mercado firms are significantly different from zero relative to the debt maturities of firms trading on other governance levels. NM debt, even though they have similar overall leverage levels, as shown in Table 4 (approximately 28 percent). NM firms have 54 percent of their debt as long-term debt, while firms on other trading levels have 41 percent long-term debt relative to total debt. We understand that this result may provide more evidence that NM firms operate in a less asymmetrical environment and are therefore able to issue long-term debt, while creditors are able to distinguish a good investment from a bad investment, thus reducing the default premium.

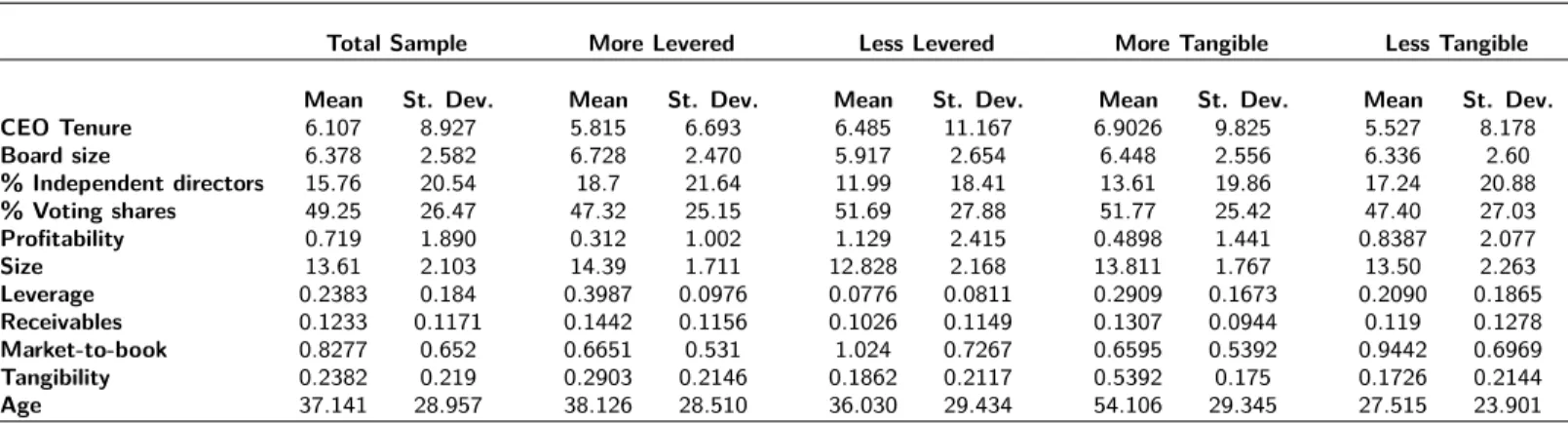

20 Table 3 – Descriptive Statistics of Explanatory Variables

This table reports descriptive statistics of our right-hand side variables. CEO Tenure and Firm age are in years. Percentage of independent directors is the proportion of outside directors relative to the total number of directors on the board. ROA is defined as EBITDA divided by total assets. Percentage of voting shares is the percentage of all voting shares held by majority shareholders. Size is defined as the log of total assets. Tangibility is the ratio of fixed assets to total assets. Market-to-book is the market value of equity plus the book value of assets minus the book value of equity. “More levered” indicates the 50 percent more levered firms, whereas “Less Levered” indicates the 50 percent less levered firms. The “More Tangible” group consists of the firms above the median tangibility and “Less Tangible” those below the median tangiblity. All accounting data are from Economatica, and the other data were obtained from firms’ reports.

Total Sample More Levered Less Levered More Tangible Less Tangible

Mean St. Dev. Mean St. Dev. Mean St. Dev. Mean St. Dev. Mean St. Dev.

CEO Tenure 6.107 8.927 5.815 6.693 6.485 11.167 6.9026 9.825 5.527 8.178

Board size 6.378 2.582 6.728 2.470 5.917 2.654 6.448 2.556 6.336 2.60

% Independent directors 15.76 20.54 18.7 21.64 11.99 18.41 13.61 19.86 17.24 20.88

% Voting shares 49.25 26.47 47.32 25.15 51.69 27.88 51.77 25.42 47.40 27.03

Profitability 0.719 1.890 0.312 1.002 1.129 2.415 0.4898 1.441 0.8387 2.077

Size 13.61 2.103 14.39 1.711 12.828 2.168 13.811 1.767 13.50 2.263

Leverage 0.2383 0.184 0.3987 0.0976 0.0776 0.0811 0.2909 0.1673 0.2090 0.1865

Receivables 0.1233 0.1171 0.1442 0.1156 0.1026 0.1149 0.1307 0.0944 0.119 0.1278

Market-to-book 0.8277 0.652 0.6651 0.531 1.024 0.7267 0.6595 0.5392 0.9442 0.6969

Tangibility 0.2382 0.219 0.2903 0.2146 0.1862 0.2117 0.5392 0.175 0.1726 0.2144

Age 37.141 28.957 38.126 28.510 36.030 29.434 54.106 29.345 27.515 23.901

21

Table 4 – Summary Statistics of Debt Maturity by Trading Levels

This table displays summary statistics of our sample. The sample consists of 308 firms, all of which trade on the BMF&Bovespa, the Brazilian stock exchange. We exclude financial and utilities firms.

Corporate Debt Maturity of Novo Mercado firms

% Debt Maturing in More than Mean 25th percentile Median 75th percentile St. Dev.

Leverage 0.281 0.1836 0.2847 0.3947 0.1519

One Year 0.5491 0.1650 0.4774 0.7239 1.142

Two Years 0.4868 0.1409 0.4024 0.6273 1.137

Three Years 0.3372 0.0302 0.2176 0.4246 0.9523

Four Years 0.174 0.0068 0.0927 0.2805 0.2130

Five Years 0.1044 0.0 0.030 0.1291 0.1732

Corporate Debt Maturity, other trading levels

% Debt Maturing in More than Mean 25th percentile Median 75th percentile St. Dev.

Leverage 0.283 0.1481 0.2873 0.415 0.1639

One Year 0.412 0.0384 0.4114 0.6532 0.3275

Two Years 0.3856 0.0384 0.3996 0.6183 0.3002

Three Years 0.2623 0.0083 0.2190 0.4220 0.2467

Four Years 0.1557 0.0 0.0811 0.2312 0.193

Five Years 0.0963 0.0 0.0231 0.1192 0.1599

22 Table 5 – Correlation Matrix

This table reports the correlations between our explanatory variables. Size is defined as the log of total assets. Profitability is the ratio of EBITDA to total assets. Tangibility is the ratio of fixed assets to total assets. Leverage is defined as total debt to total assets. Board size is the number of directors on the board. Independent directors is the ratio of the number of outside directors to the total number of directors on the board. CEO tenure is the log of the number of years in office of the CEO. Receivables is defined as total receivables divided by total assets. Percentage of voting shares controlling shareholder is the number of voting shares held by controlling shareholders divided by the total number of voting shares. Collateral is defined as the ratio of fixed assets plus receivables plus inventory to total assets. All accounting data are from Economatica, and the other data were obtained from firms’ reports.

Firm size Profitability Tangibility Market to

Book % Leverage

Board Size %

Indep. Directors %

CEO

Tenure % Receivables

Firm Age %

Firm size 1

Profitability -0.5385* 1

Tangibility 0.1104* -0.2607* 1

Market/Book -0.1517* 0.2224* -0.2310* 1

Leverage -0.4795* 0.6703* -0.1221* 0.0225 1

Board Size 0.6181* -0.2776* 0.0945* 0.0424 -0.3040* 1

Independent Directors % 0.2967* -0.1423* -0.1964* 0.1231* -0.1548* 0.2657* 1

CEO Tenure 0.011 -0.1213* -0.0719* -0.0261 -0.0938* -0.12* -0.0118 1

Receivables 0.1280* -0.1604* -0.1913* -0.0434 -0.1218* -0.0333 0.2365* 0.0784* 1

Firm age -0.0781* -0.0604* 0.3057* -0.2009* 0.0084 -0.1630* -0.2221* 0.1697* 0.0939* 1

% Voting shares control -0.2078* 0.1946* 0.0988* -0.0866* 0.0746* -0.2236* -0.3817* 0.0523 -0.1210* 0.0827*

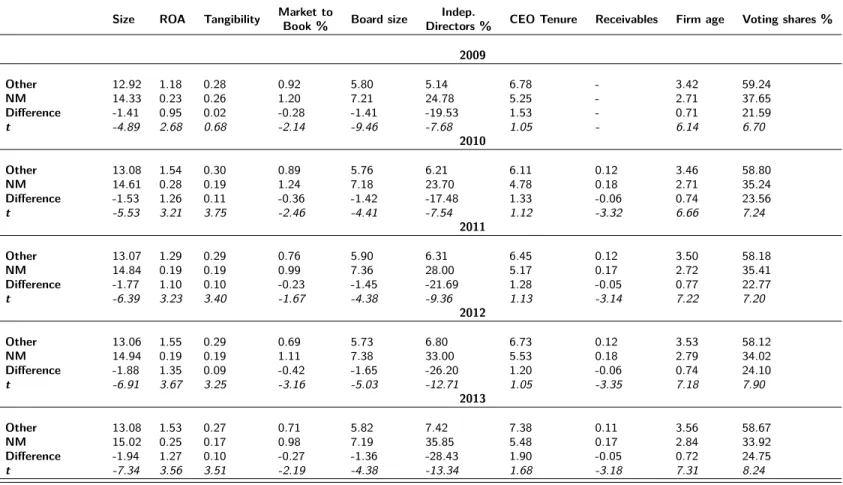

23 Table 6 – Characteristics of Firms Trading on NM Level and Other Levels

This table reports the results for the two-sample equal variance means test. Novo Mercado is the subsample of firms that trade on Brazil’s BM&F Bovespa Novo Mercado level. Firms trading on other levels are included in the "Other" subsample. We exclude financial and utilities firms. ROA is the ratio of EBITDA to total assets. Tangibility is the ratio of fixed assets to total assets. Board size is the number of directors on the board. Independent directors is the ratio of the number of outside directors to the total number of directors on the board. CEO tenure is the number of years in office of the CEO. Receivables is defined as total receivables divided by total assets. Voting shares is the ratio of voting shares held by controlling shareholders to total voting shares. All accounting data are from Economatica. Board size and composition, CEO tenure and firm age were obtained from firms’ reports.

Size ROA Tangibility Market to

Book % Board size

Indep.

Directors % CEO Tenure Receivables Firm age Voting shares %

2009

Other 12.92 1.18 0.28 0.92 5.80 5.14 6.78 - 3.42 59.24

NM 14.33 0.23 0.26 1.20 7.21 24.78 5.25 - 2.71 37.65

Difference -1.41 0.95 0.02 -0.28 -1.41 -19.53 1.53 - 0.71 21.59

t -4.89 2.68 0.68 -2.14 -9.46 -7.68 1.05 - 6.14 6.70

2010

Other 13.08 1.54 0.30 0.89 5.76 6.21 6.11 0.12 3.46 58.80

NM 14.61 0.28 0.19 1.24 7.18 23.70 4.78 0.18 2.71 35.24

Difference -1.53 1.26 0.11 -0.36 -1.42 -17.48 1.33 -0.06 0.74 23.56

t -5.53 3.21 3.75 -2.46 -4.41 -7.54 1.12 -3.32 6.66 7.24

2011

Other 13.07 1.29 0.29 0.76 5.90 6.31 6.45 0.12 3.50 58.18

NM 14.84 0.19 0.19 0.99 7.36 28.00 5.17 0.17 2.72 35.41

Difference -1.77 1.10 0.10 -0.23 -1.45 -21.69 1.28 -0.05 0.77 22.77

t -6.39 3.23 3.40 -1.67 -4.38 -9.36 1.13 -3.14 7.22 7.20

2012

Other 13.06 1.55 0.29 0.69 5.73 6.80 6.73 0.12 3.53 58.12

NM 14.94 0.19 0.19 1.11 7.38 33.00 5.53 0.18 2.79 34.02

Difference -1.88 1.35 0.09 -0.42 -1.65 -26.20 1.20 -0.06 0.74 24.10

t -6.91 3.67 3.25 -3.16 -5.03 -12.71 1.05 -3.35 7.18 7.90

2013

Other 13.08 1.53 0.27 0.71 5.82 7.42 7.38 0.11 3.56 58.67

NM 15.02 0.25 0.17 0.98 7.19 35.85 5.48 0.17 2.84 33.92

Difference -1.94 1.27 0.10 -0.27 -1.36 -28.43 1.90 -0.05 0.72 24.75

t -7.34 3.56 3.51 -2.19 -4.38 -13.34 1.68 -3.18 7.31 8.24

24

Table 7 – Debt Maturity in Firms Trading in NM Level

This table reports the two-sample equal means test between companies that trade on the Novo Mercado level and companies that trade on other levels. The variables are total debt maturing each year divided by total debt. Data were obtained from companies’ required filings and Economatica.

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

% of Debt Maturing in more than 3 years

Novo Mercado 0.186 0.2567 0.277 0.2581 0.2818

St. Err. (0.0201) (0.0225) (0.0256) (0.02304) (0.0261)

Other levels 0.1293 0.1533 0.1403 0.1822 0.17748

(0.0163) (0.0172) (0.0166) (0.0203) (0.0212)

Difference -0.0565 -0.1033 -0.1366 -0.0759 -0.1043

t -2.169 -3.707 -4.677 -2.457 -3.121

% of Debt Maturing in more than 4 years

Novo Mercado 0.0866 0.1404 0.17048 0.158 0.1752

(0.012) (0.1404) (0.0192) (0.0186) (0.0205)

Other levels 0.068 0.0936 0.0892 0.1111 0.1121

(0.0093) (0.0119) (0.0122) (0.0148) (0.0159)

Difference -0.0187 -0.0469 -0.0812 -0.0466 -0.0631

t -1.246 -2.426 -3.743 -1.98 -2.468

% of Debt Maturing in more than 5 years

Novo Mercado 0.0416 0.0749 0.091 0.0985 0.0939

(0.0074) (0.0101) (0.0131) (0.0153) (0.0140)

Other levels 0.0358 0.050 0.0497 0.0664 0.0560

(0.0057) (0.0076) (0.0077) (0.0112) (0.0560)

Difference -0.0058 -0.0250 -0.0419 -0.0322 -0.0379

c (-0.619) -2.007 -2.940 -1.733 -2.265

25

Table 8 – Debt Maturity in Firms with a 50% Blockholder

Blockholder equals one if a firm has one blockholder who holds at least 50 percent of the firm’s voting shares. This table reports results for a two-sample equal means test. The variable is total debt maturing each year divided by total debt. Data were obtained from companies’ required filings and Economatica.

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

% of Debt Maturing in more than 3 years

Blockholder 0.1412 0.1799 0.0970 0.1750 0.1925

(0.0164) (0.0183) (0.013) (0.0199) (0.0231)

No 50% blockholder 0.1629 0.2148 0.1513 0.2540 0.2503 (0.0201) (0.0217) (0.0177) (0.0231) (0.0242)

Difference -0.0217 -0.0349 -0.0543 -0.0789 -0.0577

t -0.844 -1.234 -2.502 -2.594 -1.728

% of Debt Maturing in more than 4 years

Blockholder 0.0719 0.1001 0.0970 0.1060 0.1219

(0.0093) (0.0118) (0.013) (0.0146) (0.0170)

No 50% blockholder 0.0789 0.1279 0.1513 0.1561 0.1554 (0.011) (0.0155) (0.0177) (0.0181) (0.0189)

Difference -0.0070 -0.0278 -0.0543 -0.0500995 -0.0335

t -0.476 -1.447 -2.502 -2.165 -1.316

% of Debt Maturing in more than 5 years

Blockholder 0.0349 0.0525 0.0515 0.0605 0.0731

(0.0058) (0.0077) (0.0084) (0.0111) (0.0118)

No 50% blockholder 0.0419 0.0692 0.0841 0.0997 0.0706 (0.0072) (0.009) (0.012) (0.015) (0.0118)

Difference -0.00701 -0.0167 -0.0326 -0.0392 0.0024911

t -0.767 -1.35 -2.312 -2.150 0.149

26

3 EMPIRICAL ANALYSES

For our empirical analyses, we choose a GMM approach, which addresses several types of problems. First, the observations may not be independent within industries and between periods. In addition, there may also be issues with the construction of the variables, omitted variables, and simultaneity and robustness over time. We address these issues in this section.

OLS regressions assume independence of observations; however, the observations may not be independent, especially across industries and across firms. The underlying assumption of zero observable individual effects is too strong. We run Breusch-Pagan tests to determine whether we can reject the null hypothesis that the error terms are independent across firms and industries. We reject the null hypothesis of non-correlated error terms.

Another issue of concern is heteroskedasticity across firms and industries. In unreported tests, we regress debt maturing in 5 years or more against all of our explanatory variables and obtain a Breusch-Pagan/Cook-Weisberh Chi-square statistic of 127.3, which leads us to reject the null hypothesis of homoskedasticity. We next assume that the heteroskedasticity is not linear and therefore apply White’s general test for heteroskedasticity. The Chi2 for White’s test is 204.22. Therefore, there is strong evidence in favor of heteroskedasticity. To control for heteroskedasticity, we use White’s correction in all of our regressions, which yields consistent standard errors1.

We acknowledge the possibility of collinearity. Table 5 shows the correlations between our independent variables. Leverage has the higher correlations with our explanatory variables, which will be addressed further in our GMM estimation. We calculate the variance inflation factor (VIF) to detect imperfect multicollinearity. For instance, for the "more than one year" OLS regression, we find a VIF of 1.80, which indicates that multicollinearity is not an issue.

Correlations between error terms across periods also present a limitation of our model. Omitted variables could cause our estimate to be biased. We run Ramsey RESET tests to detect whether our models are severely harmed by omitted variables and reject the null hypothesis that the model has no omitted variables. The Ramsey test can also indicate simultaneity bias or incorrect functional form. Because our variables are well established in the literature, we believe that endogeneity could be causing this disturbance.

Endogeneity is in fact the most serious problem with our model. We tackle this issue by running generalized method of moments estimations. Similar to Benmelech 2006(BENMELECH, 2006), we instrument leverage with profitability. According to that study, there is no natural instrument that could explain leverage but not maturity, while profitability is one of the main

27

determinants of leverage and has very little correlation with maturity2.

Taking all of these issues into consideration (endogeneity, heteroskedasticity, and serial cor-relation between error terms), we expect GMM estimators to be more efficient than 2SLS. For instance, in the presence of heteroskedasticity, 2SLS are consistent but not asymptotically ef-ficient. Additionally, the method of moments is more appropriate than fixed effects estimators because the latter implies that time-varying errors have zero means and zero correlations. The presence of heteroskedasticity and serial correlation causes fixed effects estimators to lose consis-tency (WOOLDRIDGE, 2001).

3.1

Total Debt Levels

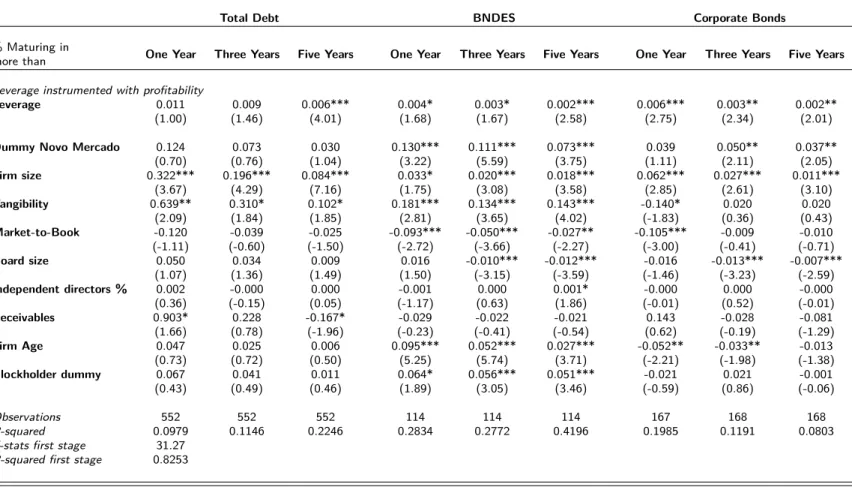

We run a GMM model to find the determinants of long-term leverage from firms’ characteristics. All of our explanatory variables have a one-period lag, as we expect leverage levels and debt maturity in t=1 to be a consequence of firm characteristics in t=0. We find that firm size is the main determinant of firms’ long-term total leverage as well as tangibility. Although the other coefficients are not statistically significant, their signs mostly accord with what was expected.

3.2

BNDES debt

Summary statistics show that BNDES debt accounts for approximately 13% of debt maturing in more than one year for the companies in our sample, which is practically the same amount as bonds. BNDES debt accounts for 5.7% of the debt maturing in four or more years, whereas bonds account for approximately 7.3%. These results are reported in Table 1.

We also run GMM estimations for BNDES debt and corporate bonds. With debt maturing in more than one year as the dependent variable, the Novo Mercado Dummy and firm age are positive and statistically significant at 5%, and tangibility is positive and significant at 10%. These results are also economically relevant. For instance, Novo Mercado firms have 13% more long-term BNDES debt relative to firms trading on other levels. With debt maturing in more than three years, the NM dummy, tangibility and firm age remain positive and statistically and economically significant. Firm size and the blockholder dummy are positive and significant at 10%, and market-to-book and board size are marginally significant. Therefore, firms with lower information asymmetry (that is, larger, older, more tangible firms with lower market-to-book values and better governance levels) are less levered with BNDES debt. With the five-year dependent

2 In an unreported test, we also used Tangibility as an instrument for Leverage, as we expected it to have a

28

variable, the results are rather similar to those with the three-year variable, except the NM dummy and firm age are now only marginally significant (at 10%) and market-to-book loses significance.

3.3

Corporate Bonds

We find that for corporate bond debt maturing in more than one year, size and leverage are positive and significant at 1% and 5%, respectively. A 1% increase in firm size implies a 6.2% increase in long-term corporate bond payables. Market-to-book is negative and significant at 1% for bonds maturing in more than one year. For bonds maturing in more than five years, leverage and size remain relevant, and board size shows a negative and significant coefficient. The addition of one member to the board of directors reduces the levels of bonds maturing in 5 or more years by 0.7%. Firm age has a negative relationship with long-term bonds. The NM dummy is positive and significant for debt maturing in more than 3 and more than 5 years. On average, NM firms have 3.7% more bonds maturing in five or more years than their counterparts.

Overall, we conclude that the maturity of corporate bonds is positively related to the NM dummy, firm size, and leverage and negatively related to board size and firm age.

3.4

Comparative analysis

29

30 Table 9 – GMM Regressions

This table reports generalized method of moments estimates. All of the regressions include an intercept (not reported). The dependent variables are the amount of debt maturing in more than one, three and five years. Size is defined as the log of total assets. Profitability is the ratio of EBITDA to total assets. Tangibility is the ratio of fixed assets to total assets. Leverage is defined as total debt to total assets. Board size is the number of directors on the board. Independent directors is the ratio of the number of outside directors to the total number of directors on the board. CEO tenure is the log of the number of years in office of the CEO. Receivables is defined as total receivables divided by total assets. Blockholder is a binary variable that equals one if the firm has one stockholder who holds at least 50 percent of the firm’s voting shares and zero otherwise. All of the accounting data are from Economatica, and the other data were obtained from firms’ reports. All of the variables are winsorised at the 5 percent level, and all of the regressors are lagged by one year. Heteroskedasticidy-consistent t statistics, clustered by firm, are in parentheses. *, ** and *** indicate significance levels of 10%, 5% and 1%, respectively.

Total Debt BNDES Corporate Bonds

% Maturing in

more than One Year Three Years Five Years One Year Three Years Five Years One Year Three Years Five Years

Leverage instrumented with profitability

Leverage 0.011 0.009 0.006*** 0.004* 0.003* 0.002*** 0.006*** 0.003** 0.002**

(1.00) (1.46) (4.01) (1.68) (1.67) (2.58) (2.75) (2.34) (2.01)

Dummy Novo Mercado 0.124 0.073 0.030 0.130*** 0.111*** 0.073*** 0.039 0.050** 0.037**

(0.70) (0.76) (1.04) (3.22) (5.59) (3.75) (1.11) (2.11) (2.05)

Firm size 0.322*** 0.196*** 0.084*** 0.033* 0.020*** 0.018*** 0.062*** 0.027*** 0.011***

(3.67) (4.29) (7.16) (1.75) (3.08) (3.58) (2.85) (2.61) (3.10)

Tangibility 0.639** 0.310* 0.102* 0.181*** 0.134*** 0.143*** -0.140* 0.020 0.020

(2.09) (1.84) (1.85) (2.81) (3.65) (4.02) (-1.83) (0.36) (0.43)

Market-to-Book -0.120 -0.039 -0.025 -0.093*** -0.050*** -0.027** -0.105*** -0.009 -0.010

(-1.11) (-0.60) (-1.50) (-2.72) (-3.66) (-2.27) (-3.00) (-0.41) (-0.71)

Board size 0.050 0.034 0.009 0.016 -0.010*** -0.012*** -0.016 -0.013*** -0.007***

(1.07) (1.36) (1.49) (1.50) (-3.15) (-3.59) (-1.46) (-3.23) (-2.59)

Independent directors % 0.002 -0.000 0.000 -0.001 0.000 0.001* -0.000 0.000 -0.000

(0.36) (-0.15) (0.05) (-1.17) (0.63) (1.86) (-0.01) (0.52) (-0.01)

Receivables 0.903* 0.228 -0.167* -0.029 -0.022 -0.021 0.143 -0.028 -0.081

(1.66) (0.78) (-1.96) (-0.23) (-0.41) (-0.54) (0.62) (-0.19) (-1.29)

Firm Age 0.047 0.025 0.006 0.095*** 0.052*** 0.027*** -0.052** -0.033** -0.013

(0.73) (0.72) (0.50) (5.25) (5.74) (3.71) (-2.21) (-1.98) (-1.38)

Blockholder dummy 0.067 0.041 0.011 0.064* 0.056*** 0.051*** -0.021 0.021 -0.001

(0.43) (0.49) (0.46) (1.89) (3.05) (3.46) (-0.59) (0.86) (-0.06)

Observations 552 552 552 114 114 114 167 168 168

R-squared 0.0979 0.1146 0.2246 0.2834 0.2772 0.4196 0.1985 0.1191 0.0803

F-stats first stage 31.27

R-squared first stage 0.8253

31

4 CONCLUSION

This paper examined the determinants of debt maturity in Brazil. We report higher levels of leverage than what we presume from the trade-off theory; however, a significant amount of that indebtedness comes from short-term debt, which is in line with theories of asymmetric information. Firms with alleviated asymmetry, as in the case of those trading on Novo Mercado, have similar leverage levels but a higher proportion of long-term debt. Univariate analysis showed that firms trading on NM are indeed different from firms trading on other levels regarding management characteristics. Our findings also suggest that the presence of a blockholder who holds at least 50% of the voting shares has a positive relationship with BNDES debt maturities. The decision to issue long-term corporate bonds is positively related to firm size, leverage, and the Novo Mercado dummy and negatively related to board size and tangibility. The BNDES finances less risky projects for older companies that provide collateral and have attenuated asymmetry (the relationship between BNDES maturity and the NM dummy is positive, as is its relationship with size, tangibility, age, and blockholder).

We contribute to the empirical literature in two ways. We consider different conceptions of long-term debt by using debt maturing in more than one through more than five years as our dependent variables and by employing several methodological approaches. Furthermore, we also study the determinants of different types of debt, namely, BNDES debt and corporate bonds, which also have not yet been included in previous works.

32

Bibliography

ANTONIOU, A.; GUNEY, Y.; PAUDYAL, K. The determinants of debt maturity structure: evidence from France, Germany and the UK. European Financial Management, Wiley Online Library, v. 12, n. 2, p. 161–194, 2006.

BARCLAY, M. J.; SMITH, C. W. The maturity structure of corporate debt. The Journal of Finance, Wiley Online Library, v. 50, n. 2, p. 609–631, 1995.

BARNEA, A.; HAUGEN, R. A.; SENBET, L. W. A rationale for debt maturity structure and call provisions in the agency theoretic framework. The Journal of Finance, Wiley Online Library, v. 35, n. 5, p. 1223–1234, 1980.

BENMELECH, E. Managerial entrenchment and debt maturity: Theory and evidence. Harvard University and The National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, Citeseer, 2006. BERGER, P. G.; OFEK, E.; YERMACK, D. L. Managerial entrenchment and capital structure decisions.The Journal of Finance, Wiley Online Library, v. 52, n. 4, p. 1411–1438, 1997. BLACK, B. S.; CARVALHO, A. G. D.; GORGA, E. Corporate governance in Brazil. Emerging Markets Review, Elsevier, v. 11, n. 1, p. 21–38, 2010.

CÉSPEDES, J.; GONZÁLEZ, M.; MOLINA, C. A. Ownership and capital structure in Latin America. Journal of Business Research, Elsevier, v. 63, n. 3, p. 248–254, 2010.

CHONG, A.; SILANES, F. López-de. Corporate governance in Latin America. IDB Working Paper, 2007.

DEMIRGÜÇ-KUNT, A.; MAKSIMOVIC, V. Institutions, financial markets, and firm debt maturity.Journal of Financial Economics, Elsevier, v. 54, n. 3, p. 295–336, 1999.

DIAMOND, D. W. Debt maturity structure and liquidity risk. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, JSTOR, p. 709–737, 1991.

FLANNERY, M. J. Asymmetric information and risky debt maturity choice. The Journal of Finance, Wiley Online Library, v. 41, n. 1, p. 19–37, 1986.

FLANNERY, M. J.; RANGAN, K. P. Partial adjustment toward target capital structures.Journal of Financial Economics, Elsevier, v. 79, n. 3, p. 469–506, 2006.

JENSEN, M. C. Agency cost of free cash flow, corporate finance, and takeovers. Corporate Finance and Takeovers. American Economic Review, v. 76, n. 2, 1986.

33

MYERS, S. C. The capital structure puzzle.The Journal of Finance, Wiley Online Library, v. 39, n. 3, p. 574–592, 1984.

PORTA, R. L. et al. Legal determinants of external finance. The Journal of Finance, JSTOR, p. 1131–1150, 1997.

RAJAN, R. G.; ZINGALES, L. What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from international data. The Journal of Finance, Wiley Online Library, v. 50, n. 5, p. 1421–1460, 1995.

TITMAN, S.; WESSELS, R. The determinants of capital structure choice. The Journal of Finance, Wiley Online Library, v. 43, n. 1, p. 1–19, 1988.