FUNDAÇÃO GETULIO VARGAS

ESCOLA BRASILEIRA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO PÚBLICA E DE EMPRESAS

MESTRADO EXECUTIVO EM GESTÃO EMPRESARIAL

IMPACT ASSESSMENT AND QUALITY ANALYSIS OF CORPORATE

SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY (CSR) PROGRAMS OF MINING

COMPANIES AND THEIR CONTRIBUTION TO SUSTAINABLE

DEVELOPMENT IN THE COMMUNITIES THEY OPERATE: CASE

STUDY: TENKE FUNGURUME MINING SA IN THE DEMOCRATIC

REPUBLIC OF CONGO (DRC).

Jaynet Desire Kabila

DISSERTAÇÃO APRESENTADA À ESCOLA BRASILEIRA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO

DEDICATION

Ficha catalográfica elaborada pela Biblioteca Mario Henrique Simonsen/FGV

Kabila, Jaynet Desire

Impact assessment and quality analysis of corporate social responsability (CSR) programs of mining companies and their contribution to sustainable development in the communities they operate: case study Tenke Fungurume Mining SA in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) / Jaynet Desire Kabila. – 2015.

142 f.

Dissertação (mestrado) - Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas, Centro de Formação Acadêmica e Pesquisa.

Orientador: Joaquim Rubens Fontes Filho Inclui bibliografia.

1. Responsabilidade social da empresa. 2. Desenvolvimento sustentável. 3. Administração local. 4. Indústria mineral. I. Fontes Filho, Joaquim Rubens. II. Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas. Centro de Formação Acadêmica e Pesquisa. III. Título.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Reaching this far meant that I had many shoulders to lean on all along the winding road and enduring journey.

To God the Lord Almighty for all;

My recognition and gratitude goes to:

My supervisor Professor Joaquim Rubens Fontes Filho, PhD for his valuable guidance and encouragement all along the preparation process of this thesis;

My family and friends, always supportive and caring;

All the participants physical and moral persons who contributed to this study in terms of their precious time and information;

The Tenke Fungurume Company for having accepted their Company to be the Case of Study for this thesis and to all the Company Executives, senior to junior officers for all their support during the field visits;

The habitants of Tenke and Fungurume areas for their valuable insight and information during the Focus Group Discussions, Interviews and field visits;

Thank you all for your invaluable and unconditional participation and support.

God Bless you all abundantly!

ABSTRACT

Purpose – This case study presents an impact assessment of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programs of the TFM Company in order to understand how they

contribute to the sustainable development of communities in areas in which they operate.

Design/Methodology/Approach - Data for this study was collected using qualitative data methods that included semi-structured interviews and Focus Group Discussions most of

them audio and video recorded. Documentary analysis and a field visit were also

undertaken for the purpose of quality analysis of the CSR programs on the terrain.

Data collected was analyzed using the Seven Questions to sustainability (7Qs) framework,

an evaluation tool developed by the Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development

(MMSD) North America chapter. Content analysis method was on the other hand used to

examine the interviews and FGDs of the study participants.

Findings - Results shows that CSR programs of TFM SA do contribute to community

development, as there have been notable changes in the communities’ living conditions.

But whether they have contributed to sustainable development is not yet the case as

programs that enhance the capacity of communities and other stakeholders to support these

projects development beyond the implementation stage and the mines operation lifetime

need to be considered and implemented.

Originality/Value – In DRC, there is paucity of information of research studies that focus on impact assessment of CSR programs in general and specifically those of mining

companies and their contribution to sustainable development of local communities. Many

of the available studies cover issues of minerals and conflict or conflict minerals as mostly

referred to. This study addressees this gap.

Africa, Assessment, CSR, Democratic Republic of Congo, Mining Industry, local

communities, Sustainable Development

LIST OF TABLES

TABLES Page

Table 1.1 Selected Minerals Production of African Countries, USGS 2005 6

Table 1.2 Cobalt Mine productions, Mining Reserves, Refinery production, 6

Refinery Capacity per Country. In metric tonnes (MT), 2006.

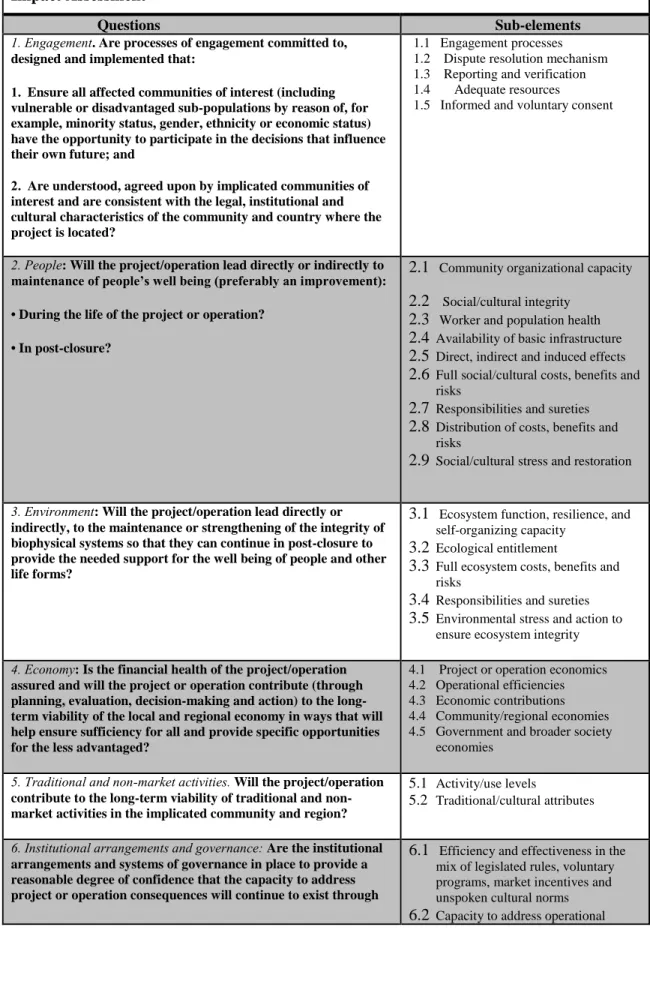

Table 3.1 Questions and Sub-elements of the 7Qs Assessment Framework

to be used for Impact Assessment 31

Table 3.2 Criterion of Study Sample Selection 33

Table 3.3 Criteria: 1,3,4,5 33

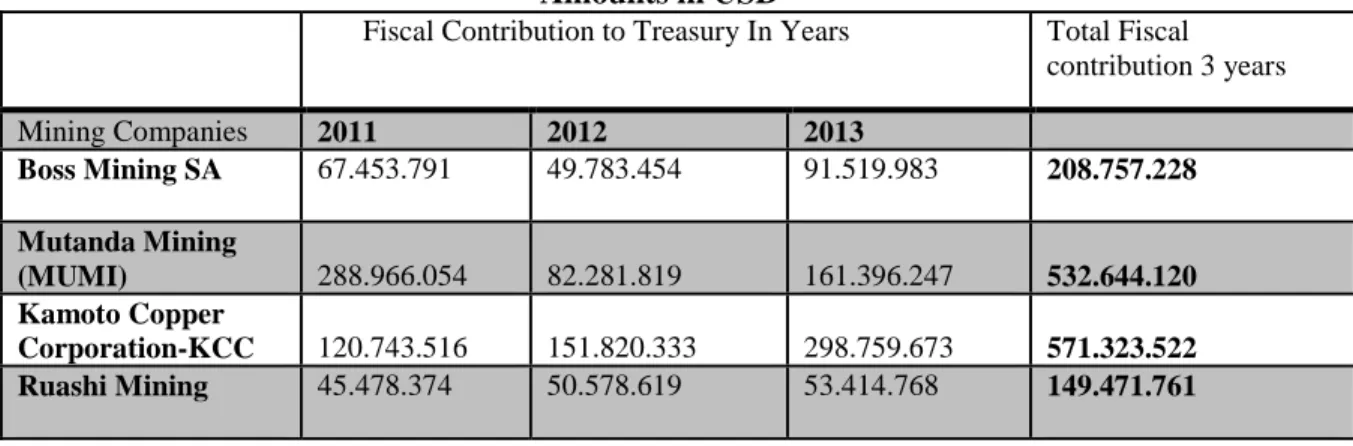

Table 3.4 Comparative Data for Top 5 Mining Companies 33

Table 3.5 Interview, Focus Group Discussions and Field Visit Respondents 40

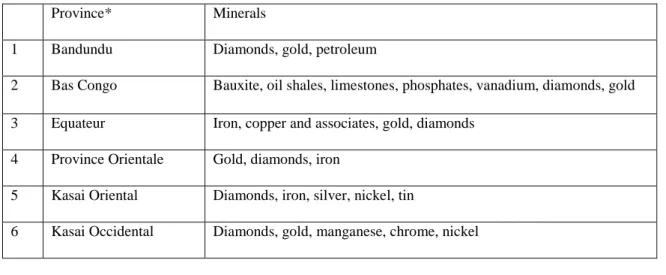

Table 4.1 Geographical Distributions of Minerals in DRC by Province 54

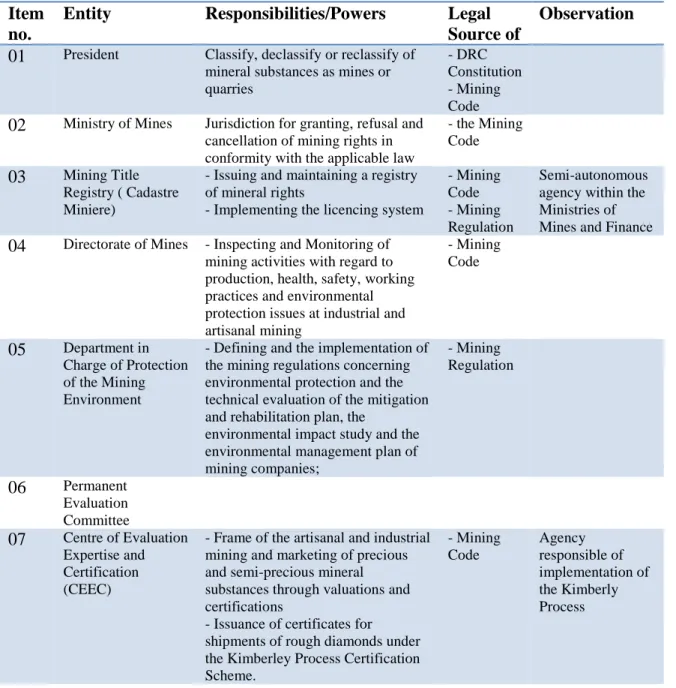

Table 4.2 Illustration of the Main / Key Entities Charged with regulation

in the Mining industry and their Key responsibilities 59

Table 4.3 Tenke Fungurume Mining Company SA at a glance 63

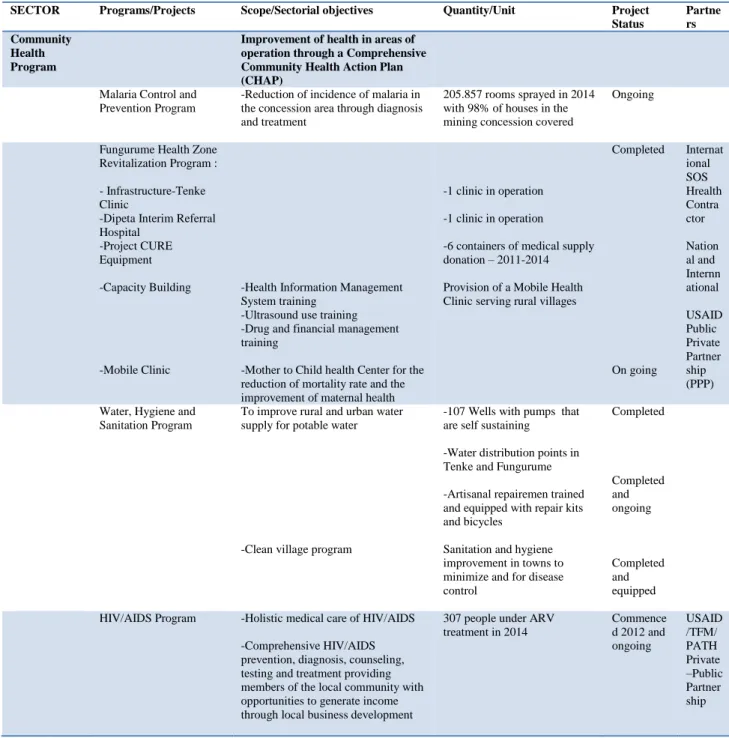

Table 4.4 Presentations of TFM Community Development Programs 66

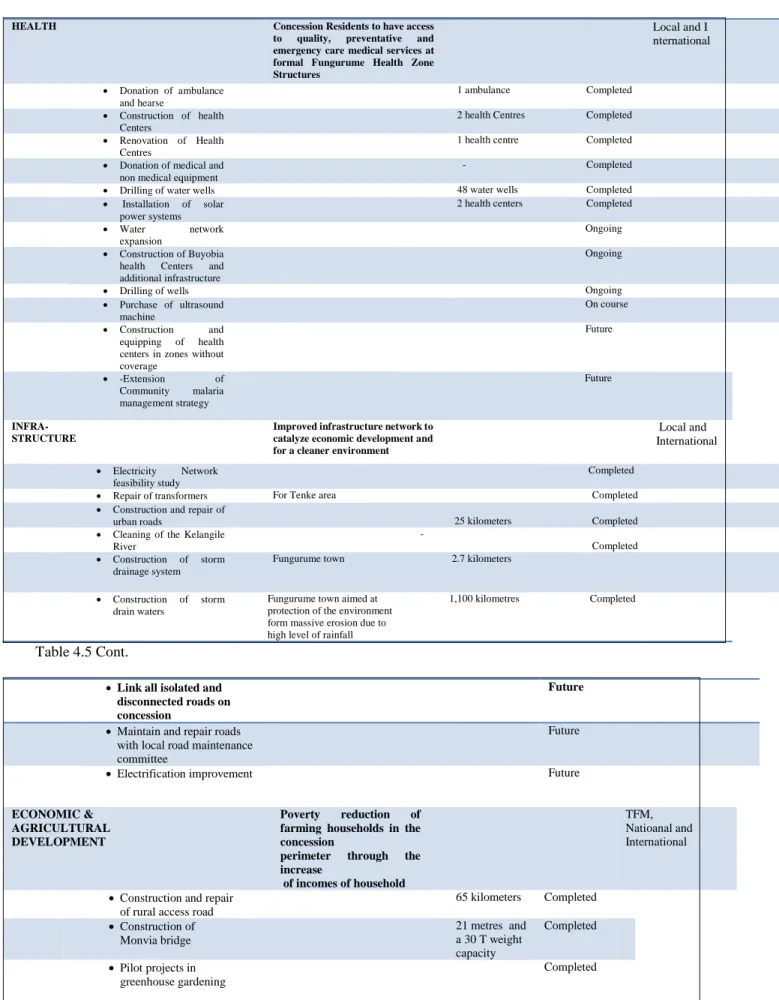

Table 4.5 Presentation of CSR Program and Detailed Projects of the

TFM Social Fund 67

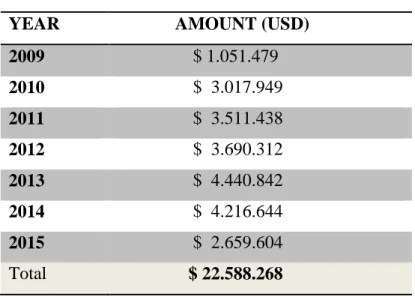

Table 4.6 TFM Annual 0.3% Net Values of Sales to the SCF 71

Table 4.7 TFM Contributions to SCF per Program (March 2009 August 2015) 72

within the 7Qs Impact Assessment Tool

Table 5.2 Presentation of the TFM CSR programs/Projects within the

7Qs Impact Assessment Tool 77

LIST OF IMAGES & FIGURES

IMAGES Page

Image: 4.1 An excerpt on Draining of a continent: The Case of Congo 50

Image: 4.2 ‘The status of the Congolese Economy’ 52

Image 4.3: Map of the DRC with the New 26 Constitutional Provinces 56

Image 4.4: TFM Mining Concession Area 67

Image 5.1 Integrated Development Zone Total Area 93

Image 5.2 First Phase of the New Town Development in the IDZ area 94

Image 5.3 The TFM Resettlement process 94

FIGURES

LIST OF ACRONYMS

ARN Africa Natural Resources

APP Africa Progress Panel

APR Africa Progress Report

AU African Union

BAD Banque Africaine de Developpement (African Development Bank)

CEPAS Centre d’Etudes pour l’Action Sociale – (The Centre of Study for social

Action)

CSR Corporate Social Responsibility

DRC Democratic Republic of Congo

EITI (ITIE) Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative

ESI Environmental and Social Impact Report

GDP Gross Domestic Product

GRI Global Reporting Initiative

ICMM International Council on Mining and Metal

IFC International Finance Corporation

IFM International Finance Management

IMF International Monetary Fund

KPMG Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler.

LACRPF Land Access, Compensation, and Resettlement Policy Framework (for TFM)

MAD Mining Africa Development

MMSD Mining Minerals and Sustainable Development

OECD Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

PWC Price Water Coopers

UNDP United Nations Development Programs

UNDP HDI United Nations Development Programs / Human Development Index

USGS United States Geological Survey

UN United Nations

WB World Bank

WBCSD World Business Council on Sustainable Development

WBG World Bank Group

WESD World Earth Summit Declaration

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Content

Page

DEDICATION PAGE I

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS II

ABSTRACT III

LIST OF TABLES IV

LIST OF IMAGES & FIGURES V

LIST OF ACRONYMS VI

CHAPTER ONE: Study Orientation and Basics

1.1 INTRODUCTION 1

1.1.1 Corporate Social Responsibility, the Global Context 4

1.1.2 Mining (Extractive) Industry in the Global Context 5

1.2 Contextual Background on CSR and the Mining Industry

in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) 7

1.3 Study Justification 8

1.4 General and Main Objectives of the Study 10 1.4.1 General Objective

1.4.2 Specific / Main Objectives

1.4.3 What is Impact Assessment then? 11

1.5 Conceptual Study Approach 11

1.6 Limitations of the Study 12

CHAPTER TWO: Literature Review and Conceptual Analysis

2.1 Introduction 13

Content Page 2.2.1 The Global outlook on CSR and the mining Industry 17

2.2.2 CSR in the Mining Industry in the Democratic Republic of Congo:

An Overview of Legal Obligations 18

2.3 Contextualizing of the Corporate Social Responsibility and

Sustainable Development concepts 19

2.4 Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) 21

2.4.1 Corporate Social Responsibility in the mining industry

2.5 Contextualising Sustainable Development 23 2.5.1 Sustainable Development, CSR and Theoretical Perspectives

CHAPTER THREE: Research Methodology

3.1 Introduction 24

3.2 Research Methodology and Design 24

3.2.1 Methodology 25

3.2.2 A Look at the Case Study Methods 26

3.2.3 Case Study as an Evaluation Research Method 28

3.3. Selecting and Defining the Case for Study 32 3.3.1 Study Sample

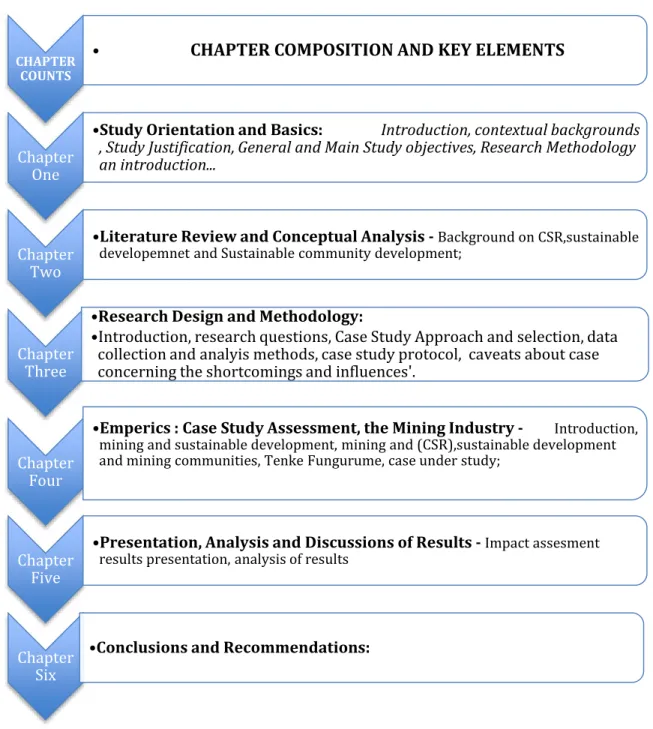

3.4 Research Action Plan 34

3.4.1 Structure of the Study 35

3.5 Data Collection Methods 35

3.5.1 Primary Sources 36

3.5.2 Secondary Sources

3.6 Data Analysis 42

3.6.1 Introduction

3.6.2 Qualitative Data Analysis 42

Content Page 3.7 Ethical issues and Trustworthiness of the Study 44

3.7.1 Trustworthiness (Integrity) 44

3.7.2 Ethical Issues 47

CHAPTER FOUR: Case Study Assessment

4.0 The Mining Industry in the Democratic Republic

of Congo (DRC) 49

4.1 Introduction

4.2 The Mining Industry in DRC: A brief history 49

4.2.1 Description of the DRC Mining Sector 54

4.2.2 The Mining Law and Regulatory Regimes 57

4.3 Mining Industry in the Sustainable Development Agenda 59 4.4 Sustainable Development and the Mining Communities 60 4.5 Tenke Fungurume Mining: The Case Study Assessment 61

4.5.1 A Brief History 61

4.6 Tenke Fungurume Mining CSR programs: An Overview 64

4.6.1 TFM Company Community Development (CD) 65

4.6.2 TFM Company Social Community Fund (SCF) 65 4.6.3 The Scope of the CSR Programs Coverage 67

4.6.4 CSR Programs Budget and Financing: An Overview 70

CHAPTER FIVE: Presentation, Analysis and Discussion of Results

5.1 Introduction 74

5.2 Presentation of Results 75

5.2.1 The Seven Questions to Sustainability (7Qs) Assessment

Content Page 5.3 Analysis and Discussion of the 7Qs Results 79

5.3.1 Introduction 79

5.3.2 Engagement 79

5.3.3 People 79

5.3.4 Environment 80

5.3.5 Economy 81

5.3.6 Traditional and Non Traditional Activities 81

5.3.7 Institutions and Governance 81

5.3.8. Synthesis Continuous Learning through periodic

Assessment results 82

5.4 Analyses and Discussion of Interview and FGDs Results 82

5.4.1 Introduction 83

5.4.2 Understanding CSR: What it entails for the Respondents 83

5.4.3 CSR and its Impact: General View 84

5.4.4 Health 85

5.4.5 Education 87

5.4.6 Infrastructure Development

89

5.5 Economic and Agricultural Development 94

5.5.1 Economic Development 94

5.5.2 Agricultural Development 95

5.6 Capacity Building 96

5.7 Community Resettlement Program 97

5.8 Environmental Program 101

5.9 Other Community Services 102

CHAPTER SIX: Conclusions and Recommendations 106

6.1 Conclusions 106

6.2 Recommendations 108

BIBLIOGRAPHY 1

ANNEXES 1

Interview Protocol Guide

Field Visit Photos:

Interviews

Chapter One

1. Study Orientation and Basics

1.1

Introduction

“ A transparent and inclusive mining sector that is environmentally and

socially-responsible…which provides lasting benefits to the community and pursues an integrated view of the rights of various stakeholders…is essential for addressing the adverse impacts of the mining sector and avoid conflicts induced by mineral exploitation…” -The African Mining Vision

Businesses, from a quick analysis and understanding of the above statement, should have

a ‘human heart’ in order to understand that if you want to settle in any environment you

have to be ready to become part of the puzzle and not an isolated or loose piece. This is

more of a reality at least in the developing world and in the emerging economies in Africa,

a continent today mostly revered as an important economic destination in terms of market

expansion, diversification and growth for regional, continental as well as global companies.

The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is among the countries in the top on the list of

the most mineral endowed countries in the African continent and globally. Hence, the

country has become one of the economic destinations of global companies dealing in

precious, ferrous and non-ferrous metals.

According to the Minerals and Africa’s Development (MAD), an International Study

Group Report on Africa’s Mineral Regimes, the development of mineral resources can

have diverse outcomes for different stakeholders implicated in the mining industry (MAD,

2011). These are diversified complications and consequences that cut across borders

depending on the countries and regions where the mining activities are taking place (ibid).

The belief that in the African mining industry, there are losers and winners in the mineral

extraction process has been held for a long time to the extent that it has been looked at as

a new type of colonialism commonly referred to as neo-colonialism. Such argument is

held to signify where rich countries dominate the poor countries’ economically such as in

and sell these minerals ore in their raw format to the developed countries where the refining

process is done. The refined product with a superior quality and added value is then sold

later at high prices sometimes over four hundred folds above the original purchase price.

This ‘winner and looser status’ can be attributed to the fact that there are disparities

between the stakeholders’ class whereby the broad interests of some key stakeholders such

as communities and even the state actors have been less secured and hence the sense of

vulnerability and exploitation. This narrative can surely be attributed to the continued high

poverty levels that characterize mining communities where these companies operate;

severe infrastructural deficits and contemporary build infrastructures that are prone to

climate change destruction and sometimes of low quality standard built. What is needed

to reverse this appalling situation according to Africa Mining Vision is for the developing

countries governments, especially African governments in this context “ to shift focus from

simple mineral extraction to much broader developmental imperatives in which mineral

policy integrates with developmental policy” (Africa Progress Report - APP, 2013).

Hundreds of trucks are loaded with minerals everyday and leave the mines for export

destinations, but it is argued by the communities living in the mining areas that the same

effort is not felt and witnessed on the ground when it comes to community development

agenda. This is a statement echoed in a mining community in the Eastern part of the

Democratic Republic of Congo in the Province Oriental in 2011 by members of one

community during a Social Humanitarian visit. This has been a centre of gravity that

sometimes causes social tensions between the communities and support groups of

‘vulnerable’ people on one side and sometimes the state, government entities who are seen as to be allowing such situation to prevail, and the mining companies on the other side.

Taking into consideration this discourse, felt and believed by different stakeholders on the

receiving end, the biggest challenges has been how to overcome the assumed if not proved

historical structural deficiencies of the mining industry. How can these issues be addressed

or how are they addressed today is a very key issue. This definitely calls for a long-term

strategy that focuses on the disparities evident and how the mining industry can contribute

efforts and strategies such as investing back in the communities through (sustainable)

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programs.

The World Earth Summit Declaration (WESD) 2002 recognized that “ mining minerals

and metals are important to the economic and social development of many countries. While

minerals are essential for modern living, enhancing the contribution of mining, minerals

and metals to sustainable development include having efforts at all levels.” This implies

that it is globally accepted that mining can be and is a vehicle that can contribute to

sustainable (Community) development at the lower echelon of society to the national level

of a country as a whole, at the regional as well as at the continental level; especially in

those minerals resources endowed countries and continents.

This study approaches the idealism to realism by interesting itself in understanding the

contribution of the mining industry CSR programs by evaluating their impact on the

community they operate in. It further interests itself in whether those programs and projects

are executed in a way that they will effectively stand the test of time. This is during the

mines lifespan or beyond, long when the mines have been depleted and closed down. The

status of these implemented projects for instance infrastructures in terms of quality as

linked to durability, longevity as well as adaptation and resistance to standard normal wear

and tear cycle of the environment is an important issue that needs analysis.

The Africa Progress Panel1suggest that “foreign investors have a key role to play and

global companies operating in Africa should apply the same accountability principles and

the same standards of governance as they are held to in rich countries. They should also

recognize that disclosure matters.” Not doing so among other things “… hurt Africa and

weaken the link between (mineral) resource wealth and poverty reduction.” (APR,

2013:10). Least to say is that poverty reduction can be achieved through sustainable

development starting at the grassroots levels taking into consideration the Human

1 The APP is comprised of distinguished individuals from the private and public sector who advocate for

shared responsibility between African leaders and their International partners to promote equitable and sustainable development for Africa and is chaired by Koffi Annan, former United Nations Secretary General and Nobel laureate. (I would suggest it should have read African ‘countries’ and not ‘leaders’ as leaders represent countries and since International Partners is a general identifying noun and not individual

Development Index as one of the probable indicators. There have been efforts of disclosure

ongoing by Global Companies working in Africa case specific those operating in the

mineral mining sector. It would be interesting to do a comparative study of the said

companies that have operations in developed countries as well as developing countries in

order to understand the level of compliance to disclosure rules that they have adhered to.

There is a notion that mining companies spend money in CSR programs and most often

when they do, they usually do not take a keen interest to assure that the end result in terms

of quality goes hand in hand with sustainability. In other words, a commitment to build for

example a hospital or schools does not entail the verification of the end product in terms

of its quality, which will in other words determine in part one element of sustainability.

Hence, the issue of quality is sometimes if not mostly secondary.

1.1.1 Corporate Social Responsibility in the Global Context and Africa

Most of the literature that exists and available about CSR presents the debate in a global

context but very little if not limited empirical research presents the picture on the nature

and extent of CSR in developing countries (Visser, 2006). Most countries on the African

continent fall under this category of developing nations. However, there is a notable

exception that can be referenced in this CSR field, and it is the study that was carried out

by Baskin (2006) that looked into the corporate responsibility behavior trends of 127

leading companies from 21 emerging economies across Asia, Africa, Latin America, and

Central and Eastern Europe, of which he compared with 1700 leading companies in

high-income countries members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and

Development - OECD, (Visser, 2006). As noted further, only 2 countries from the 53

African countries were included but this was a global study on Corporate Responsibility

behavior.

It can be argued that the limit to two countries would not present fairly enough a

picturesque view of a diversified Africa whose development is demarcated across

geographical regions. For example, countries in the Northern part of Africa are more

developed than those found in Sub Saharan Africa. This demarcation between North and

characteristics (McKinsey & Company, 1982). Today, this demarcation has shifted further

to economic characteristics with South Africa and Nigeria, by most measures standing out

to be the economic powerhouses in and of Sub Saharan Africa. South Africa alone is

producing a third of the continent’s manufactured goods, with the highest exports statistics

and overall with the highest Gross Domestic Product-GDP (McKinsey 1982).

Indeed the above-illustrated scenario is also reflected in the CSR discourse in Africa. It is

by far South Africa that dominates the CSR literature in Africa (Visser, 2005a).

Notwithstanding, other minimal studies exist for example for Ivory Coast (Schrage and

Ewing. 2005); Kenya (Dolan and Opondo, 2005); for Nigeria (Amaeshi et al, 2006);

Tanzania (Egels, 2005), Mali and Zambia (Hamann et al., 2005), all in (Visser, 2006).

CSR is an important part and paradigm of mineral extractive industries today and more

than ever the need to adopt CSR measures and conducts are pressing more with the

globalization of the mining industry. As mining companies on the set are considered as

responsible for hazardous related outcomes that affect the communities they operate in,

they have adopted ways and means to address these issues and appease the population in

those areas by mitigating the negative impacts in these communities.

1.1.2 Mining (Extractive) Industry in the Global Context

Africa by far dominates the world’s precious metals and precious stones as the table below shows. In some selected minerals, Africa ranks among the world’s top producing

countries. Although Africa, for example, contributed only 9% in terms of bauxite’s world

production, it is interesting to note that US imports 29% of its bauxite from Africa (Africa

Natural Resources - ARN, 2008). And again, the resource reserve base of some of the

mentioned minerals is changing due to known high grade reserves discovery and

investments during recent years. The DRC in this context can be added to the list of gold

producing countries.

Below is a table (Table 1.1) from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) site that shows some selected minerals production in 2005 from African countries.

Source: (Africa Natural Resources, 2008)

Table: 1.2 Cobalt Mine Production, Mining Reserves, Refinery production, Refinery capacity per Country. Unit: Metric Tonnes (MT), 2006.

Africa, despite that its mineral refinery capacity is limited according to elements in (Table

1.2), has highly contributed to the significant supply of mineral ores being refined in other

parts of the world. Such is the case of China with a mine production of 2.300 MT in 2006

had the refinery production capacity of 12.700 MT of refined cobalt out of the total world

75 to 90% of the cobalt that China imported (and refined) came from the DRC as the table

above illustrates the differences (ARN, 2008:31).

1.2

Contextual Background on CSR and the Mining Industry in theDemocratic Republic of Congo

To date, very few literature work exist on the Corporate Social Responsibility in the mining

industry in DRC. Of those few literatures that exist, most have been commissioned by

International entities and Development partners such as UNDP, IFC, hence are focused on

specific areas of interest such as minerals and conflict (Dweidary et al), and are neither

necessarily interested nor particularly concerned with impact assessment of CSR programs

of mining companies. Others studies done have been commissioned by mining companies

in efforts to respect the legal requirements of the country and fulfill internal processes of

the company.

The 2002 DRC Mining Code enacted by Law no. 007/2002 of 11 July 2002 is the basic

legal document that governs the extractive mineral mining sector in the DRC and is

supplemented for implementation purposes by the Mining Regulations Decree

no.038/2003 of 26 March 2003 adopted by the Council of Ministers and published in the

official Journal of the Democratic Republic of Congo. The Mining Regulations fix the

practical modalities and procedures for the implementation conditions of the mining code.

It further regulates all other connected issues that were not directly detailed by the law.

The Mining Code determines a number of obligatory provisions to all titleholders of any

mining rights. Amongst those obligations, the law provides for how a titleholder should

relate to the local population in the mining areas in which they operate. Articles 477 and

480 of the Mining regulations provide for the implementation responsibilities of the Mining

Code by different administrative entities as determined by the law and also provide for the

kind of relation that should exist between the local communities and the operators of the

mining activities.

Article 69, point g of the Mining Code stipulates that in the application of the exploitation

license the interested party has to submit along “ a plan that shows how the project will

operations”. Furthermore, chapter IV of annexes to the mining regulations gives an

explicit description of what should compose the plan of sociological environment. Vital

articles can be summarized as follows2:

(i) Article 38 determines that the titleholder or operator must identify explicitly the

population living in the areas of operation. There are a number of detailed

orientation as to what it implicates;

(ii) Article 93 provides that security measures in favor of the local population in

these mining areas should be well elaborated and presented;

(iii) Article 124 and 125 states that the titleholder should provide a budget line for

activities to be taken against negative environmental impacts;

(iv) Article 127 requires that the titleholder must prepare and organize a sustainable

development plan with a precise calendar and budget of execution.

The specific above-mentioned articles among other numerous ones can be said to be the

basis of the legal foundation of the CSR in the Democratic Republic of Congo in the mining

industry. However, in general the implementation process of the legal framework and other

regulations seem to be a very big challenge for the country as many other priorities take

centre stage and often the follow up of the implementation process is sometimes relegated

to the second level. This means that although the CSR programs for communities are of a

compulsory nature, the implementation phase in effect of the outlined programs are not

necessarily given the same attention in the follow up stage.

1.3 Study Justification

The importance of a sound relation in any business environment between the shareholders

and its stakeholders internal as well as external cannot be over emphasized enough. In order

to have a good business nurturing and human living environment, a shared environment

needs to sustain the people living there and maintaining a good standing for the business

being conducted in those areas. Today, with globalization taking place at all levels and

aided by communication, we can hear a lot of forms of CSR, which have become some sort

2 All articles mentioned are based on the provision of the Mining Regulation and its annexes which

of an approach as well of businesses to increase their competitive advantage by addressing

external factors as well as internal factors.

To date as mentioned earlier, there is very limited research conducted concerning the

mining sector in the Democratic Republic of Congo that look into the CSR concept, CSR

programs and their impacts in the extractive minerals mining industry. The purpose of this

study is therefore to do an impact assessment of the implemented CSR programs and a

quality analysis of mining companies in order to understand their contribution to

sustainable community development agenda. It is important also to understand how CSR

programs of these mining companies contribute to the companies’ performance both in

terms of financially or non-financially gains.

Hence the purpose of this study is specifically classified as follows:

(I) For the mining companies’ stakeholders such as the communities involved, the policy makers and implementers at the national level;

Comprehend the role of the mining companies to exhibit ethical behavior and moral

management of the environment they work in according to guidelines that they have

to abide by and liaise that with the responsibility of assuring the implementation of

the said.

Contribute and give impulse to a legal evaluation, review and amendment of

regulations that concern CSR policy;

Identify the existence of a tool for CSR impact assessment programs and in case of

non existence of such a tool advocate for the local adaptation or development of

one;

(II) For the field of study dealing with CSR and the mining industry;

Add andcontribute to the body of literature that already exist dealing with CSR in

the mining industry with case specific interest of this study the developing and

emerging markets in Africa with DRC as the country of case study. Why

developing countries because they represent the most rapidly expanding and

developing economies and hence the most lucrative growth markets for business

(IMF, 2006). With this comes into context the impact of the operations of these

1.4 General and Main Objectives of the Study 1.4.1 General Objective

This study is intended to gain further knowledge as well as contribute to the field of CSR

in the area of policy formulation that deal with the mining industry in the Democratic

Republic of Congo. To achieve this, the study embarked on the search for answers to the

below mentioned issues but first of all the task was to analyse mining companies’ CSR

programs contribution to sustainable development of communities they operate in by

further looking at:

The factors that lead to the mining company investment in CSR programs;

The significance of the CSR programs of mining companies to the group and the

communities they operate in;

The review of CSR programs input and outcome in terms of quality and

sustainability for communities.

The evaluation tools used by the mining companies to assess effective

implementation of their CSR programs.

1.4.2 Specific/ Main objective of Study

This study has in no specific way any intention to question whether the social investments

done by mining companies through CSR programs contribute to the development of

communities that they operate in and whether there are any added advantage to the

company itself. It is a generally agreed that CSR programs do and can contribute either in

a positive and /or negative way in the environment and communities they operate in. But,

this is rather, to understand such, in terms of impact assessment as to how much really of

that value is added in terms of addressing a need (relevance), changes accrued

(sustainability), and value for monetary investment (quality more than quantity) on the

basis of programs underway.

The main objective is to conduct an impact assessment of CSR programs of one of the

order to understand how such programs contribute if so, to Sustainable Community

Development and not simply Development. It further looks at challenges faced by the

selected company in the process and how they are overcome.

1.4.3 What is Impact Assessment then?

This study focuses on the impact assessment of the programs of a mining company and in

order to understanding what it is we take a look at what it involves. The International

association of Impact Assessment (IAIA) defines impact assessment as ‘the process of

identifying the future consequences of a current or proposed action’ (IAIA, 2009).

Fitz-Gibbon (1996) defined impact assessment as ‘ … any effect of the service or of an event

or initiative on an individual or group’. The impact can be positive as well as negative in

nature. Therefore this definition is the appropriate to be referenced for this paper as

measuring impact is about identifying and evaluating change (Streatfield & Markless,

2009). The whole idea is to get an understanding whether the programs are making a

difference in the people’s life in this case the local communities living in the zones of the mines’ operations.

1.5 Conceptual Study Approach

Leila Patel (2005) in her work on social developmental approach argued that this approach

seeks to make a link of social economic policies within a state a directed development

process involving civil society organizations and companies in promoting social goals

(Mushonga, 2012). Today, CSR as a concept refers to the general belief that is held by a

growing number of people that modern business have responsibilities to society that extend

beyond their obligations to the shareholders, stockholders, and or investors in the firm

(Archie Carroll, 2007).

The above has been the case in most developing countries in Africa as CSR practice is

legal binding and the legal requirements are embedded into different laws of the countries.

This is the case as has been noted with this study sample of the Democratic Republic of

the Congo. These provisions are found in the Fundamental Laws to legislative and also

executive generated legal rules and regulations of procedure and implementation. In an

have made it a point to include non-state actors and organisations as part of their

development partners in terms of funding, resource mobilization and implementing stages.

1.6 Limitations of the Study

This study is faced with a number of limitations. First the CSR discourses in Africa in

general and the DRC in particular are still in their early stages of development hence very

limited information is available in the field of research studies done. Most of CSR literature

available is on South Africa and few other countries as it has been noted earlier in the study

(point 1.1.1). For example in the context of the DRC there is no evidence till now in the

process of drafting this document of any independent study done on the particular theme

under study (Impact Assessment of CSR and mining companies) by any independent

researcher (moral or physical person) in the field.

Therefore, secondly, this leads in turn to limited literature relating to impact assessment

and sustainable development as more CSR studies conducted in DRC were more oriented

towards narratives examining the role of mining industry in relation to, among others,

armed conflict, peace building and good governance discourses.

And finally though not least, (Yin, 2016:146) evokes the fact that “experienced qualitative

researchers recognize that true neutrality may not exist”, and in fact the author of this study

does not fall in this category yet of being identified as an experienced qualitative

researcher. This implies that such a condition will have some consequences on the process

of probably data collection and more vehemently on the data analysis procedure therefore

making the data presented seems like a ‘negotiated text’ as the researcher’s point of view whether subjective or objective can affect the findings. Yin (2016: 286), emphasizes that

the author of the study who is at the same time the research instrument (i.e. the interviewer

Chapter Two

2. Literature Review and Conceptual Analysis

2.1 Introduction

This chapter takes a brief look at the academic and professional literatures on CSR in

general and CSR in mining industry, impact assessment tools and framework, sustainable

community development, mining companies in DRC and so forth. It further looked at two

sector and their contribution to sustainable development. Although there has not been an

independent assessment study conducted on any mining companies in the DRC, studies

conducted further afield in other countries have served as a basis for understanding the

field and raising issues that were not raised fully in those early studies carried out.

One common denominator of all these studies could said to be the fact that the mineral

mining sector all over the world is a sector that concerns the exploitation of ‘non

-renewable resources’ as the end result will be the same; depleted natural resources and

lifelong impacts to deal with. The biggest difference between countries who are mineral

mining countries is the way they deal with the present while sustaining for the future; after

the mines lifetime have been reached.

2.2 A brief Background of (Corporate) Social Responsibility

The concept of CSR is dynamic multifaceted and global and continues to be a contentious

matter around the world (Muthuri, 2012). There are a plethora of concepts that have

emerged to explain the concept and responsibilities of business in the society. Such

concepts are interchangeably used in different circumstances and different countries to

refer to the same practice but done with different modalities. These include such prominent

scholars and pioneers of the CSR dialogue that include; Giving (Friedman et al, 2005);

Grant making; Corporate Social Investment (CSI), Kapelus (2004) referred to it as

Corporate citizenship; and some recent development that has linked the concepts of

Sustainable Development and sustainability (Visser 2004) in Mushonga, 2012:18).

Lohman and Steinholtz (2003 in Mushonga 2012:17) have argued that CSR should be seen

as a combination of many areas, which include corporate governance, ethics,

accountability, sustainability and human rights. Today this is a reality as the concept of

CSR today evolves around all those sub-concepts but concepts of their own.

The notion that business has duties to society is firmly entrenched in the past several

decades although there is change in the way people view the relationship between business

and society. Archie Carroll (1979) and other researchers believe that we should judge

corporations not just on their economic success but also on non-economic criteria. Carroll

four responsibilities (Carroll, 2000, p.187) to fulfill to be good corporate citizens. These

are economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic.

(I) Economic Responsibilities

Whereby economic responsibilities focus mostly on the elements that the corporation

[managers] has to adhere to in order to deliver to its shareholders the benefits and profits

awaited from the business interaction with their stakeholders specifically in this case the

customers and clients by delivering added value. This goes beyond this boundary to

encompass the need to take the interest of other stakeholders into consideration. This is

clearly observed in Novak (1996) where there is the outline of the 7 economic

responsibilities to be fulfilled in this category as:

(I) Satisfy customers with goods and services of real value,

(II) Earn a fair return on the funds entrusted to the corporation by its investors,

(III) Create new wealth, which can accrue to nonprofit institutions that own shares of

publicly held companies and help lift the poor out of poverty as their wages rise,

(IV) Create new jobs,

(V) Defeat envy through generating upward mobility and giving people the sense that

their economic conditions can improve,

(VI) Promote innovation,

(VII) Diversify the economic interests of citizens so as to prevent the tyranny of the

majority

(II) Legal Responsibilities

Legal responsibilities entail complying with the law and playing by the rules of the game.

Laws regulating business conduct exist because society does not always trust business to

do what is right by being self-regulatory. However, laws have certain shortcomings to

ensure responsible behavior: they are of limited scope and cannot cover all contingencies;

but rather merely provide a moral minimum for business conduct. Sometimes these laws

are reactive in nature, telling us what ought not to be done, rather than proactive, telling us

what ought to be done; and might be followed involuntarily out of fear of punishment rather

(III) Ethical Responsibilities

Ethical responsibilities can be said to overcome the limitations of legal obligations. They

entail being moral, doing what is right, just, and fair; respecting the moral rights of

individuals singularly and collectively; and avoiding harm or social injury as well as

preventing harm caused by others (Smith and Quelch, 1993). Ethical responsibilities are

those policies, institutions, decisions, or practices that are either expected (positive duties)

or prohibited (negative duties) by members of society, although they are not necessarily

codified into law (Carroll, 2001). They derive their source of authority from religious

convictions, moral traditions, humane principles, and human rights commitments (Novak,

1996).

(IV) Philanthropic Responsibilities

Carroll’s philanthropic or discretionary responsibilities of corporations refer to society's

expectation that organizations become or rather are good citizens by being involvement in

such voluntary activities through the support of programs benefiting a community or the

nation.

However, the business case for CSR is far from clear-cut. In general, empirical studies on

this topic are not conclusive (Griffin and Mahon, 1997; Margolis and Walsh, 2003). Even

though mining companies may face particularly strong incentives for ensuring their ‘social

license to operate’ (Humphreys, 2000) due to the long- term, location-specific nature of

their investment, company leaders and investors are still unsure about the relationship

between CSR and profits (MMSD (Mining, Minerals, and Sustainable Development) &

PWC (PriceWaterhouseCoopers), 2001).

There are a growing number of schools of theory and practice in the field of CSR

advocating that companies and other orgnisations need to behave in a socially responsible

manner through corporate self regulation, voluntary community initiatives and

environment consciousness (Jenkins, 2005). Therefore CSR is a helpful conceptual

Mining has had a considerable role in shaping human development as it significantly

impacts on neighbouring and hosting communities where its operations take place (Petrova

& Marinova, 2012). The attention towards this issue has increased in the last 10 years with

the way the mining impacts on local communities and how the local communities are seen

to address these challenges that impact on their lives. Therefore with this awakening, comes

widespread community demands for the relevant, direct and sustainable benefits from

mineral wealth have been identified as a recent phenomenon (MMSD, 2002) that needs

suitable response from companies operating in those areas and the government at local to

national levels.

Several studies have been realized concerning the responsibilities of mining companies

towards the communities they operate in. Labone (1999) concurs that mineral exploitation

must among other issues encompass social dimensions apart from the technical and

economic points of views. Davis (1998) acknowledges that the success of any mining

depends not only on technical and economic mitigation of negative impacts but on

community concerns as well, hence the importance of the CSR programs that have been

adopted by several mining companies. But in order to understand these companies’

contribution to sustainable development of communities they operate in an impact

assessment as a tool that can be used to evaluate the results of these CSR investments.

The CSR concept and associated actions have become a way to demonstrate a company’s

commitment to minimise the negative impacts that germinate from mining activities

(Petrova & Marinova, 2012) but also a means to address unfavourable living conditions

that affect the community within the areas of operation. But more today, expectations

about the contribution of mining are on the rise and communities demand higher levels of

local investment outside the immediate areas of operations (Petrova &, Marinova 2012

p.2). This situation has been further reinforced by the emergence of International

Standards, Codes and Guidelines.

In most of the developing countries of Africa and specifically DRC, the most used

conceptual framework can be identified as the legal and ethical responsibilities framework

make sure that they have ‘a license to operate’ within the communities by maintaining

peace through addressing negative impacts that affect the community as a result of the

changes effectuated in the ecosystem by the mining operations.

The company hence becomes an important player in the development of the society through

its participation in community development efforts in terms of financial and material

contribution to different efforts that are aimed to mitigate the negative impacts that arise as

a result of environmental manipulation. To understand how this process works of

mitigation, a Social impact assessment (SIA) has to be conducted by the use of an

assessment tool to eventually identify the impact from those contributions.

2.2.1 The Global outlook on CSR and the Mining Industry

The CSR issues have been discussed around the mining industry as elaborated in (Jenkins,

2004; Kapelus, 2002; Cowell et al.,1999,). Because of the limited non-renewable mine

resources, the environmental hazards from the extraction activities and bad working

conditions, mining industry is on the embarrassment position among economic

development, environmental protection and social impacts (Tilt and Symes, 1999).

Mining companies it is argued, always operate in targeted areas without, sometimes,

consideration of legitimate and ethical regulations, this is because often times, mining

parameters are situated in the larger rural areas, and move to other areas after enormous

extraction and damage of the surrounding mine environment (Jenkins, 2004). Moreover,

the mining industry always hires indigenous employers but provides poor working and

living conditions. As a result, there appears to be a global tendency by communities and

Non Government Organizations, which doubt the development of mining industry from

sustainable aspect and approve the emancipation of the indigenous (Kapelus, 2002).

Based on the evidence and analysis of the data to be gathered, this study will come up with

recommendations and suggestions on how governments, businesses and communities can

individually or collectively address problems identified.

In the Mining Code, specifically articles 202 to 206 and the Mining regulation article 404,

have outlined obligations by law that mining societies and those involved in the mining

sector in general have to adhere to. The Mining Code and the accompanying regulations

provide a very comprehensive set of rules that govern the mining sector in all identified

areas that relate to the extractive industry. Issues addressed are acquisition, transfer,

operation and termination of mining rights, environment protection, cultural heritage,

protection of neighboring communities, and tax and customs incentives. This legislation

also has provisions concerning environment norms applicable to mining activities that also

include stone quarry rights and all other extractive activities.

Every mining company is by law legally bound to implement community developmental

projects in the limit of their mining concession and at times in the provincial limits of their

areas of operations. What is to be done though in terms of programs and projects is

proposed by the mining companies themselves but they have the responsibility to make

sure that implementation of the said takes place as presented in the Environmental and

Social Impact Report (ESI), a study that needs to be carried out and the report required to

be presented to designated government entities before any exploration or exploitation

license approval and rights can be granted.

2.3 Contextualizing of the Corporate Social Responsibility and Sustainable Development concepts

Corporate Social Responsibility and ‘sustainability’ are two terms that are mostly used in

describing social and environmental contributions and consequences (both negative as well

as positive) of business activity (Jenkins & Yakovleva, 2005). This is at least well so in the

mineral mining sector. More literally the sustainability concept has experienced an

evolution the past decades as sustainability in terms of corporate and business has steadily

broadened to encompass other broader social economic issues such as health, safety,

labour, community development from the initial focus on philanthropy and environmental

But is Corporate Sustainability, a term that is used to refer to essential and long term

corporate success for ensuring that markets deliver value across society. Is this more of a

strategy for the survival of the companies than strategies vehemently developed with the

first and foremost intention of servicing the societies in which they operate in? It can be

argued that without these companies’ operations in those societies or communities, there

are some issues that would have never been of concern but because of the transformation

taking place it demands demands that such measures to be adopted to safeguard against

overlapping effects. In the UN Global Compact3 the opening phrase is ‘Corporate

sustainability is imperative for business today’, meaning that for business to survive, to be successful, to continue producing intended results the corporate structure has to be

sustaining, to be able to survive.

The document further suggest that ‘ The well-being of a workers, communities and the planet is inextricably tied to the health of the business’, suggesting that these interest groups earlier mentioned survival is incontestably dependable on the status quo of the

corporate hence the business. I would argue that it is a two-way dependence lane. The well

being of one depends equally on the other but again, after all, communities existed long

before the existence or coming into being of today’s sophisticated businesses that trail

behind them all kinds of laudable and regrettable outcomes. The more sophisticated and

advanced the world becomes the more appropriate and adequate measures are needed to

address the status quo. For example the issue of climate change and its impact on the

environment was not highest on agenda in the 18th to 19th century during the industrial

revolution, a period predominantly agrarian, where rural societies in Europe and America

became industrial and urban.

With industrialization, the iron and textile industries along with the development of the

steam engine, played central roles in the Industrial Revolution. And neither prior to the

industrial revolution where manufacturing was often done in people’s homes using hand

tools or basic machines was an issue. Although it has been acknowledged that

3The UN Global Compact is the world s largest corporate sustainability initiative that has produced a

industrialization brought about an increased volume and variety of manufactured goods

and an improved standard of living for some, it also result in often-grim employment and

living conditions for the poor and working classes. Hence, it can also be argued that; ‘The

well-being of a business is inextricably tied to the health of the workers, communities and

the planet’. In this case the two concepts are dependable.

[Corporate] sustainability can then be understood as a discipline by which companies

ensure their own long-term survival as well as a field of thinking and practice by means of

which companies and other business organisations work to extent the life expectancy of

ecosystems, communities in which they operate and economies that provide financial and

market context for corporate competitive edge and survival in order to fulfill specific

objectives. (Elkington, 2007). This is the case why CSR and its contribution to sustainable

development has become an important topic that is under constant debate to-date non more

than the mining industry (Jenkins & Yakovleva, 2004), whereby the CSR agenda has

become the increasing need for individual companies to justify their existence and

document their performance through disclosure of their social and environmental

information (Jenkins & Yakovleva, pg. 271).

CSR is a term that has been defined by the World Business Council on Sustainable

Development as “the continuing commitment by business to behave ethically and

contribute to economic development while improving the quality of life of the workforce and their families as well as of the local community and society at large.” This involves the integration of economic activity with environmental integrity, social concerns, and

effective government systems and the goal of this being sustainable development.

On the other hand, Sustainable development has not been a term that has acquired a

consensus note on what the definition should be. However, the most widely acceptable

definition is the one used in 1987 by the World Commission on Environment and

Development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability

of future generations to meet their own needs4

This definition has acquired broader support because of its ability to integrate multiple

layers of meaning and some profound implications while at the same time allowing

flexibility within defined boundaries and its possibility to be applied to the development of

many activities and sectors (MMSD, 2002 p.21).

Other definitions include the one in the ICUN joint publication with UNEP and WWF on

their report ‘Caring for our earth’ that looks at sustainable development as ‘ Development

that provides real improvements in the quality of human life and at the same time conserves the vitality and diversity of the Earth’. It could be said that this second definition is more explicit and brings out key terms that have not been referred to in the early Brundtland

Commission. However both definitions are technically broad and many elements are

undefined. It is for sure impossible to practically define every single key term in a definition

statement.

One wonders how we can be able to guarantee that the needs of tomorrow will be met

when the needs of the present cannot or are not yet able to be sufficed? And what would

those needs of the future be as we live in an everyday ever changing world that is

sometimes not feasible to predict the needs of the current generation in precise terms? For

example rise in migration and immigration, armed conflicts, terrorism, refugees’ influxes,

population explosion and forth. It is important to recall that sustainable development is

threatened by climate change, land cover change (more and more land mass desertification

taking place) and overexploitation of natural resources (Valli Moosa,

2007).

Hence it is surely a non-ending debate but one thing is for a fact; CSR programs contribute

to development in this context community development but the hanging issue is: could it

be classified as sustainable development? How do we measure the sustainability factor of

those developments taking into consideration that it is still a challenge to determine with

4 Breaking New Ground: The report of Mining, Minerals and Sustainable Development Project,

precision our needs of today and at the same time predict the needs of the future generation?

Humbly, this would make a good case for further study.

2.4 Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

2.4.1 Corporate Social Responsibility in the mining industry

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is playing an increasingly significant role in

companies’ narratives and practices particularly in the mining industry. The world’s

mining industry is flourishing due to Africa’s abundant mineral resources reserves. The

international prominence of CSR in mining can be traced to mining’s significant negative

social and environmental impacts, and the related criticism levied at companies involved

in the business of mining from governments, non government organizations (NGOs), and

local community based organizations (e.g. Banerjee, 2001; Third World Network Africa,

2001; MMSD - Mining, Minerals, and Sustainable Development), 2002.

Companies today are motivated towards business case for CSR by focusing company

efforts at responding to stakeholders, minimizing negative impacts, and maximizing

positive impacts and are said to have a positive effect on profits, at least in the medium- to

long-term (World Business Council for Sustainable Development, 2000; Holliday et al.,

2002).

2.5 Contextualising Sustainable Development

2.5.1 Sustainable Development, CSR and Theoretical Perspectives

One of the greatest challenges facing the business world today is integrating economic

activity with environmental integrity, social concerns, and effective governance systems.

In the context of the minerals sector, the goal should be to maximize the contribution to

the well being of the current generation in a way that ensures an equitable distribution of

its costs and benefits, without reducing the potential for future generations to meet their

own needs. Minerals development can also bring benefits at the local level, however, recent

adversely. The social upheaval and inequitable distribution of benefits and costs within

communities can also create social tension. (UNDP HDI report 2014)

The minerals industry cannot contribute to sustainable development if companies cannot

survive and succeed in their operations. And even so not all investment in development

programs will result into sustainable development. There is a thin line that separates the

two as sustainability looks at long-term benefits beyond today’s production and benefits.

The Corporate Social Responsibility theoretical view adopted for this research is that

introduced by Caroll (1979) that argued that the idea about CSR is based on four levels;

namely economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic responsibilities. There are a number of

empirical studies that suggest that culture may play a role in a way priorities in CSR are

defined by Caroll in (1991) that a Company needs to adhere to. More of CSR and the

theoretical approach were earlier discussed in 2.2

Chapter Three

3. Research Methodology

3.1 Introduction

In this chapter the qualitative research methodology used for this study is explained, and

the principal method of research used; the case study approach is elaborated. This includes

inter alia a discussion of the concepts, strategies, and the approaches used from data

There are two distinctive research methods used by different disciplines in conducting

research in social sciences; the qualitative and quantitative research methods. The mixed

method approach (the use of both qualitative and quantitative) is also constantly used now.

Qualitative research has become a mainstream form of research as many different scholars,

different academic and professional bodies put it to use. For the purpose of this research,

the qualitative approach was preferred as it enables a researcher to conduct in-depth

studies.

3.2 Research Methodology and Design

Research method has been referred to as a technique for data collection (Mouton, 2000) in

(Letsoalo et al, 2013), and hence involves the systematic mode, procedures or tools used

for collection and data analysis. Methodology on the other side used to refer to the overall

approach to research linked to a theoretical framework in the process of a study. Ary (2003)

and Somekh & Lewin (2005) support this view when they contend that methodology refers

to the collection of rules, principles and theories that underpin an approach under which a

research study is conducted.

Methodology therefore is important as a procedure (Mouton, 2000) and as an overall

approach to the research process from its theoretical underpinnings (Collis & Hussey,

2003) that a researcher uses to collect, condense, organize and analyze data in the process

of conducting research in the social science.

3.2.1 Methodology

Qualitative research methods are a diverse set encompassing different approaches (Elliot

& Timulak, 2005) such as empirical phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography,

protocol analysis and discourse analysis. This list in not exhaustive as Yin (2016) in his

book Qualitative Research: From Start to Finish, clearly points out with supporting

examples that the method has a more broader area of inquiry with an array of specialized

types or different variants and that there is no formal typology or inventory of such variants

that has been conducted so far. There are however 12 commonly recognized variants in use

to come up with a definition and how to distinguish it from other types of research. He

forewarns that due to it relevance to different academic disciplines and professions, it has

proven arduous to arrive to a concise agreed upon definition.

However, (Polkinghorse, 1983) in Timulak & Elliot suggest that there is a commonality of

some features in that all these qualitative methods rely on linguistic rather than numerical

data, and employ meaning-based rather than statistical forms of data analysis, thus giving

it a common definition of a sort. However, Timulak & Elliot (2003) recall us to attention

by suggesting that using distinguishing features such as the unit of measurement in words

or numerical appear not to be a credible way of characterizing different research

approaches. There are some distinctive features (Elliott, 1999) suggests, that are of far

more importance in coming up with at least a descriptive definition of the approach. Such

features (Timulak & Elliott, 2003: 147) as:

Emphasis in understanding phenomena in their own right (rather than from

some outside emphasis);

Open, exploratory research questions (versus closed-ended hypotheses);

Unlimited, emergent description options (versus, predetermined choices or

rating scales);

Use of a special strategies for enhancing the credibility of a design and analyses

(see Elliot, Fischer and Rennie, 1999); and

Definitions of success condition in terms of discovering something new (vs.

confirming what was hypothesized).

This use of features approach in an effort to distinguish qualitative research including its

specialized types, from other forms of social sciences is acknowledged by Yin (2016).

Therefore no single use of one data collection method would have made justice to this

study. The context and essence of the topic under study would have not been fulfilled from

one source of evidence. A multiple approach was necessary as different stakeholders are

involved and in order to assess the impact of the CSR programs under question as the

involved players play different roles from the programs’ inception to the implementation