The Role of Conceptual Metaphor in Idioms and Mental Imagery in

Persian Speakers

Seyyed Ali Kazemi

1; Seyyed Mahdi Araghi

2; Masoumeh Bahramy

3 1 Ahar Branch, Islamic Azad University, IranKazemi.TEFL@yahoo.com

2 Department of English Language Teaching,

Payame Noor University, PO BOX 19395-3697, Tehran, IRAN

3 Ahar Branch, Islamic Azad University, Iran

Abstrak – The present study aimed to see whether the results gained by Gibbs and

O’Brian (1990) about the consistency of the idiom images can be generalized to other communities like the Persian community in their comprehension of idioms as well. It also tried to account for why many idioms have the figurative meaning they do and to explore whether people in different societies, cultures, and languages comprehend the idioms of their languages in the same way. The participants from different areas of Iran at the time of data collection were native speakers of Farsi from both sexes. The material used for data collection in this study consists of a questionnaire comprising 20 Persian idioms. Four idioms expressed figurative meanings about anger, four about taking risks, four about insanity, four about vanity, four about talkativeness. Then the participants were asked about Causation, Intentionality, Manner, Consequence, Negative Consequence, and Reversibility. Each participant’s description of their mental images was analyzed for its general characteristics and the different general characteristics for people’s mental images for each idiom were calculated across subjects. The results suggested that the conceptual metaphor underlies the comprehension of idioms and this is not limited to the speakers of English only, but can also be generalized to speakers of a different language like Farsi and also to the speakers of different dialects of Farsi, since the participants in this study were from different provinces of Iran.

Key Words – conceptual metaphor; mental imagery; cognitive linguistic view of

idioms

1

Introduction

language and, consequently, metaphor impose structure on thought. Metaphors organize thought and shape the way we perceive the world and reality.

According to Lakoff and Johnson, most of the metaphors in everyday language are conventional in nature, that is, they are stable expressions systematically used by people. For these researchers, conventional metaphors are created in a culture to define a particular reality. The influence of culture can also be seen in novel metaphors. To Lakoff and Johnson (1980: 142), the meaning of new metaphors will be determined in part by the culture and in part by the personal experience of the user. Metaphor appropriation is not a simple process of copying unaltered the metaphorical units of language and thought used by the social group. There is always an element of personal reconstruction in the internalization of culturally shared metaphors as individuals are affected by various personal experiences and by exposure to multiple social discourses. In our speech, we make use of expressions that are not necessarily interpreted on literal grounds: these are metaphors and idioms (Papagno & Vallar, 2000, p. 516).

For example the Persian expression تسا ی ی ع (literally, “Ali is a lion”) is a metaphor meaning that he is brave. Or ن ا ب نیتسآ (literally, “to fold up one‟s sleeves”) is an idiom that means “to embark on something.” There are several theories trying to explain the structures of metaphors and idioms and how they are comprehended.

1.1 Idioms

What is referred to in the literature as „idioms‟ makes up a large and heterogeneous class of (semi -)fixed multiword expressions (Grant and Bauer, 2004). Traditionally, one of the principal criteria for classifying an expression as idiomatic has been its non-compositional nature (e.g. Fernando and Flavell, 1981). The class of linguistic expressions that we call idioms is a mixed bag of metaphors (e.g. spill the beans), metonymies (e.g. throw up one’s hands), pairs of words (e.g. cats and dogs), idioms with it (e.g. live it up), similes (e.g. as easy as a pie), sayings (e.g. a bird in the hand is worth two in the bush), phrasal verbs (e.g. come up, as in “Christmas is coming up”), grammatical idioms (e.g. let alone), and others (Kövecses, 2002, p. 199). Kövecses (2002) talks of two major views to idioms: the “traditional view” and the “cognitive linguistic view of idioms” (p. 210).

According to the traditional view, idioms consist of two or more words the overall meaning of which is unpredictable from the meanings of the constituent words. A major assumption of the traditional view is that “idiomatic meaning is largely arbitrary” (Kövecses, 2002, p. 210) that is this arbitrariness refers to the link between an idiom and its figurative meaning. This theory also states that idioms once had metaphorical origins but have lost their metaphoricity over time to the extent that they turned into “dead” metaphors with their figurative meanings being directly stipulated in the mental lexicon (Aitchison, 1987, as cited in Gibbs & O‟Brian, 1990, p. 36). In this regard, Chomsky (1980) claims that idioms are thought to be non-compositional since the figurative meaning of these phrases are not functions of the meanings of their individual parts.

According to Kövecses (2002), when it is the case that an idiom is motivated by metaphor, the more general meaning of the idiom is based on the targetdomainthat is applicable to the idiom in question. The more precise aspects of an idiom‟s meaning are based on the conceptual mapping that is relevant to the idiom (p. 211).

Regarding the comprehension of idioms, two basic theoretical approaches have been taken: one view is expressed by the lexical representation hypothesis, which suggests that they are mentally represented and processed as lexical items, the idiomatic phrase being just a large word-like unit. An alternative interpretation is suggested by the configurational hypothesis which assumes that idiomatic expressions may be mentally represented and processed not as words, but rather as configurations of words whose meanings become activated whenever “sufficient input has rendered the configurations recognizable” (Papagno & Vallar, 2000, p. 516).

Psycholinguistic studies have investigated the metaphorical motivation for idiomatic meaning empirically. One way to discover the speakers‟ tacit knowledge of the metaphorical basis for idioms is through a detailed examination of speakers‟ mental images of idioms (Gibbs & O‟Brian, 1990). In order to provide evidence for the role of conceptual metaphor in the comprehension of idioms, Gibbs and O‟Brian (1990) gave their participants idioms (e.g. hit the ceiling) and non-idiomatic expressions (e.g. hit the wall) and wanted them to report the visual imagery that each phrase elicited. They contend that images for idioms were very similar to one another across participants while images for non-idiomatic phrases varied considerably. Gibbs and O‟Brian concluded that the consistency of the idiom images is due to the “constraining influence of conceptual metaphors” (p. 147) according to which the underlying nature of our thought process is metaphorical; this means that we use metaphor to make sense of our experience. Consequently when we come across a verbal metaphor the corresponding conceptual metaphor will be automatically activated (Carrol, 2008, p. 147).

The figurative meanings of idioms may very well be motivated by people‟s conceptual knowledge that has a metaphoric basis. Therefore, there should be significant differences in the processing of literal and idiomatic expressions, due to the metaphoric nature of idioms. Although, in many instances idioms are considered dead metaphors, people make sense of them because they “tacitly recognize the metaphorical mapping of information from two domains that gives rise to idioms in the first place” (Gibbs, 1994, as cited in Kövecses, 2002, p. 212).The present study aims to see whether the results gained by Gibbs and O‟Brian (1990) can be generalized to other communities like the Persian community in their comprehension of idioms as well. It is important to trace the ways in which figurative language is comprehended by Persian speakers since Farsi is one of the languages which make an extensive use of figurative language. So the researcher‟s hypothesis is that the figurative meanings of idioms are motivated and not entirely arbitrary. To arrive at some solid evidence, the researcher conducted the study as Gibbs and O‟Brian (1990) conducted theirs.

2

Methodology

2.1 Participants

2.2 Materials

The material used for data collection in this study consists of a questionnaire comprising 20 Persian idioms selected from Razmjoo (2003). Four idioms expressed figurative meanings about anger, four about taking risks, four about insanity, four about vanity, four about talkativeness. These five groups of idioms are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: List of stimulus material

Experiment 1 Experiment 3

Anger نتف وک ا

(to flare up) (to twist an ankle)پ ک وق نتف

ن آ وج ب نوخ

(to see red) (the boiling of water)آ ن آ وج ب ن تآ یو پسا لث

(to be like a cat on hot bricks)

نت ا گ تآ یو پسا (to smoke ….) ن ق ت

(to flare up/ to fly into a passion) (to explode crackers)ن ک ی ب ق ت Taking risks

نت ا گ یو پ

(tread on some body‟s toes) (to set foot on aنت ا گ پ یو پ step) ن تفا و گ خ ب

(not to let a sleeping dog lie) (to set foot on aنت ا گ پ یو پ step)

نت ا گ وبن نا وچ

(not to let a seeping dog lie (to dip a stick in water)نت ا گ آ وچ ن ک ی ب ی ب

(to wake a sleeping lion) (to play with a ball)ن ک ی ب پوت ب Insanity

ن ا جا ا نوخ ا ب

(the lights are on but nobody‟s home) (to lease a house)ن ا جا ا ن خ ن ی ب ا ل صتا یس

(to go insane)

یس ن ی ب (to cut a wire) ن وب تحا خ ا

(to be insane) ن وب تحا ک ا (to be at rest) نت ا تی ت خ

(to be a fruit cake) (to have Telit, which is bread and sauce, for lunch)نت ا تی ت ن یا ب Vanity

ن یبوک نو آ

Experiment 1 Experiment 3

ن ب ن ک ب ی

(to carry coal to Newcastle) (to take souvenir to Kerman)ن ب ن ک ب ت غوس ن ک پ فک ی و یب

(to build a castle in the air) (to tear clothes)ن ک پ س بل ن کفا ا و ت

(to build a castle in the air) (to drop ravels in water)ن کفا آ گ س Talkativeness

ن ب ا ی ک س

(to talk the hind leg off a donkey)

ن ب ا ا غ (to take the food) ا ی ک خ

ن ن ک ت

(to talk the hind leg off a donkey) (to blast a balloon)ن ن ک ت ا ک ک ب ن وخ ا ی ک س

(to pick someone‟s brain) (to eat food)ن وخ ا غ

ن وخ ا ی ک خ

(to pick someone‟s brain) (to eat fruit)ن وخ وی

The next step was asking the participants about the causes of actions in their mental images (Causation– “What caused the action to happen?”), the intentionality of the actions (Intentionality – “Was the action done intentionally?”), the manner in which the actions were performed (Manner– “How was the action performed?”), the consequences of the action (Consequence– “What happened as a result of the action?”), the consequences of not performing the action (Negative Consequence– “What would happen if the action didn‟t happen?”), and reversibility of the action (Reversibility – “Is it difficult to reverse the action?”). Each of these probe questions followed the specific mental image

that participants were to describe. For example, when participants reported that their image for

نتف وک ا was of a red faced person running out of an inferno, they would later be asked “Is it

difficult to get that person back into the inferno?” for the Reversibility question (Experiment1).

The next set of questions tested the alternative possibility to Experiment 1; that is, the regularity in people‟s conventional images for idioms is solely due to their figurative meaning. Therefore, the five figurative meanings of the five groups of idioms were presented to the participants, in the form of a questionnaire, to see whether there is a consistency in the visual images reported (Experiment2). This experiment was done by the control group only.

Another questionnaire comprising 20 idiomatic expressions was also presented. Each non-idiomatic expression corresponded to an idiom from the first questionnaire; that is, the verbs used in each idiom were used but in a literal sense. These expressions were also followed by a set of questions like the ones following the idiomatic expressions (Experiment3).

2.3 Procedure

“Dear friends,

Please fill in the questionnaires as follows: Define each idiom. Having defined what the idiom meant please describe the image that pops into your mind as you read it. Following this, answer each of the six questions. After responding to the final question for an idiom, go to the next idiom, please. Answer the questions in as detailed and accurate a manner as possible.

The other questionnaire is supposed to be filled in the same way.”

The 20 idioms were presented in a random order for each participant. The probe questions were asked in an invariant order – Causation, Intentionality, Manner, Consequence, Negative Consequence, and Reversibility. The non-idiomatic expressions were also presented in the same way. The experiment took about a week to complete.

3.

Results and discussion

The degree of similarity in participants‟ mental images for idioms with similar figurative meanings was of paramount importance to the researcher. The protocols for each participant were accordingly analyzed in the following manner. First, each participant‟s description of their mental images was analyzed for its general characteristics. For example, when a participant reported that his/ her image

for ن وخ ا ی ک س was of a person‟s head being eaten by a big mouth, this was scored as “some

force causes the destruction of an object”. Second, the different general characteristics for people‟s mental images for each idiom were calculated across subjects. The researcher then determined the most frequent characteristics across the four idioms within each group of phrases. This provided a general image schema for each of the five groups of idioms. The results of the non-idiomatic set of expressions were calculated as well.

On the other hand, the protocols for the control group were also analyzed in the same way. The results of this analysis also provided a general image schema for each definition of the five groups of idioms. A proportion of most frequent responses is given in Table 2.

Table 2: Percentages of most frequent response for idioms (Experiment 1)

Question Most frequent response Percentage

Anger

General Image: Some force causes a container to release pressure violently .68

Causation: Anger/ stress/ pressure .89

Intentionality: Action is not intentional .90

Manner: Action is oriented with force .90

Consequences: Anger/ pressure is released .88

Negative consequences: Build-up of pressure, explosion .91

Reversibility: The action is difficult to reverse .99

Taking risks

General Image: A scene where there is an intentional exposition to danger .78

Question Most frequent response Percentage

Manner: Action is done on purpose .71

Consequences: Loss of safety/ accidents .99

Negative consequences: Safety/ well-being .89

Reversibility: The action is not difficult to reverse .78

Insanity

General Image: A scene where there is loss of control .68

Causation: A stressful situation .59

Intentionality: Action is not intentional .90

Manner: Action is done at once .61

Consequences: Mental or physical stability is lost .82

Negative consequences: Stability is maintained .94

Reversibility: The action is difficult to reverse .89

Vanity

General Image: Something is done in vain .78

Causation: purposelessness/lack of knowledge .69

Intentionality: Action is not intentional .66

Manner: Action is performed redundantly .58

Consequences: No advantage will be achieved .89

Negative consequences: Energy is reserved/ achievement is made .90

Reversibility: The action is not difficult to reverse .89

Talkativeness

General Image: Some force causes the destruction of a container .69

Causation: A bad habit/ inconsideration .90

Intentionality: Action is almost intentional .88

Manner: Action is performed with force .78

Consequences: Headache/ physical and mental distress .91

Negative consequences: Peace and quiet .91

Reversibility: The action is not difficult to reverse .70

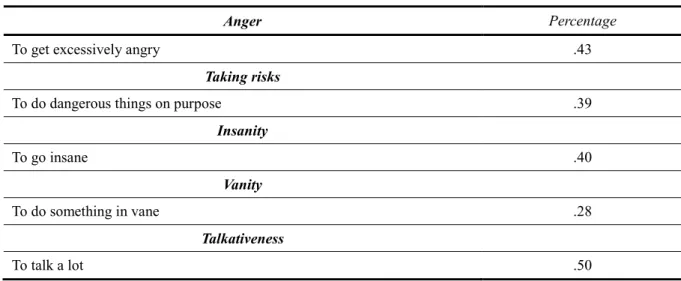

Table 3: Percentages of the most frequent responses for figurative meanings (Experiment 2)

Anger Percentage

To get excessively angry .43

Taking risks

To do dangerous things on purpose .39

Insanity

To go insane .40

Vanity

To do something in vane .28

Talkativeness

To talk a lot .50

The non-idiomatic expressions corresponding to each idiom in Experiment 1 were also presented to elicit an image for each. Due to the disparity of the images described, the researcher could not trace the most frequent responses. In fact the participants had no unanimity in Experiment3.

As has been demonstrated by the tables, there has been a significant similarity among the participants‟ mental images for idioms. Participants‟ general image schemas for idioms only reveal part of what they understood about their mental images. More specific information is seen in Participants‟ answers to the probe questions. The probe question data provided information about participants‟ knowledge of their mental images. This was what the researcher interested in the most since the high frequency of similar responses shows the effect of the conceptual metaphor in comprehending and visualizing idioms.

The claim made in this study is that the high degree of consistency in participants‟ imagery protocols and responses to the probe questions reflects the constraints that conceptual metaphors provide for our understanding of experiences such as getting angry. “The mapping of information from different source and target domains limits our conceptualization of anger and motivates why we have the idiomatic expressions we do to talk about anger” (Gibbs & O‟Brian, 1990, p. 47). This point will be elaborated in the following excerpts from the responses provided by some participants.

For Anger idioms, the conceptual metaphor “heat of a substance in a container” dominates participants‟ descriptions of their mental images for phrases such as:

ن تآ یو پسا لث /ن ق ت/ن آ وج ب نوخ/نتف وک ا

When anger builds beyond the point at which a person can control it, we imagine that the substance or heat escapes violently from the container holding it. In this case we refer to the “heat of a substance in a container" and the source domain and to “Anger” as the target domain (Gibbs & O‟Brian, 1990, p. 47). As a result, when participants imagined ن آ وج ب نوخ (literally: the boiling of blood), they reported that the person‟s face and eyes were red from the heat of anger.

person‟s head blowing up from internal pressure with steam coming out of the top of the head or the heels as the top violently blew off.

The mental images people formed for idioms within each group were structured by a very small set of conceptual metaphors where things in a target domain (i.e., anger, talkativeness, insanity, vanity, and taking risks) were mapped into a source domain (i.e., people‟s knowledge of containers, heat, and physical forces gravity). The participants in this study did not construct a wide range of mental images for idioms where, for instance, نت ا گ وبن نا وچ (literally: to put a stick in a beehive) could be attributed to numerous causes with all sorts of possible consequences. Instead, participants had remarkably consistent and specific images of the events described in different idioms with similar figurative meanings. Traditional theories of idiomaticity, as Gibbs and O‟Brian (1990, p. 48) claim, have no justification for the reason why such consistent knowledge about the mental images of idioms are reported. Theoretical accounts of idioms mostly assume that idioms are “dead” metaphors and the association between idioms and their respective figurative meanings must be established arbitrarily by speakers. But as the results of the experiments reported cast doubt on this traditional view of idioms. The consistency of people‟s mental images for idioms and the disparity of their mental images for the idioms figurative meanings and literal expressions suggest the active role of the conceptual metaphors in motivating the figurative meanings of idioms. People tacitly know that certain idioms have the meaning they do because of the continuing influence that conceptual metaphors have on their mental images for these expressions. And it is these conceptual metaphors that motivate the links between idioms and their non-literal meanings (Bibbs & O‟Brian, 1990, p. 49).

4

Conclusion

The aim of this research was to suggest an account for why many idioms have the figurative meaning they do and to explore whether people in different societies, cultures, and languages comprehend the idioms of their languages in the same way. Following Gibbs and O‟Brian (1990), the researcher explored Persian speakers‟ mental images for idioms to see if conventional images and metaphors provide a motivating link between an idiom and its figurative meaning. Moreover, Bahramy and Araghi (2013) stated that the importance of motivation as one of the main determining factors in success of a second/ foreign language learner. The results suggest that the conceptual metaphor underlies the comprehension of idioms and this is not limited to the speakers of English only, but can also be generalized to speakers of a different language like Farsi and also to the speakers of different dialects of Farsi, since the participants in this study were from different provinces of Iran.

References

Bahramy, M. & Araghi, M. (2013). The identification of demotives in EFL university students. International Journal of Basic and Applied Science, 1(4), April 2013, 840-845

Block, D. 1992: Metaphors we teach and live by. Prospect 7(3): 42–55.Cambridge: Cambridge Press, 135-48.

Cameron, L. and Low, G. 1999a: Metaphor. Language Teaching 32: 77-96. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carrol, D. W. (2008). Psychology of language. Australia: Thomson Wadsworth.

Chomsky, N. (1980). Rules and representations. New York: Columbia University Press.

Gibbs, W. R. & O‟Brian, J. E. (1990). Idioms and mental imagery: The metaphorical motivation for idiomatic meaning. Cognition, 36, 35-68.

Grant, L. and Bauer, L. 2004: Criteria for re-defining idioms: are we barking up the wrong tree? Applied Linguistics 25: 38-61.

Kövecses, Z. (2002). Metaphor: A practical introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lakoff, G. and Johnson, M. 1980: Metaphors we live by. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Oxford, R., Tomlinson, S., Barcelos, A., Harrington, C., Lavine, R.Z., Saleh, A. and Longhini, A.

1998: Clashing metaphors about classroom teachers: Toward a systematic typology for the language teaching field. System 26: 3-50.

Papagno, C. & Vallar, G. (2001). Understanding metaphors and idioms: A single-case neuropsychological study in a person with Down syndrome. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 7, 516-528.