1

FUNDAÇÃO GETULIO VARGAS

ESCOLA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ECONOMIA - EPGE

CAIO CEZAR MONTEIRO RAMALHO

AN ESSAY ON PRIVATE EQUITY: THE HISTORY AND

FUNDAMENTALS OF FUNDRAISING IN BRAZIL

RIO DE JANEIRO

2

CAIO CEZAR MONTEIRO RAMALHO

AN ESSAY ON PRIVATE EQUITY: THE HISTORY AND

FUNDAMENTALS OF FUNDRAISING IN BRAZIL

Dissertação apresentada à Escola de Pós

Graduação em Economia da Fundação

Getulio Vargas, como requisito parcial

para a obtenção do título de Mestre em

Finanças e Economia Empresarial

Orientador:

Prof. Marco Bonomo (EPGE-FGV)

RIO DE JANEIRO

4

Dedicated to my father, Julio Ramalho,5

AGRADECIMENTOSOlhando para o início desta jornada em 2005, hoje eu vejo o quanto sou uma pessoa de sorte. Os

percalços e desvios dos últimos anos apenas me fizeram melhor compreender minha carreira, além

de consolidarem certas escolhas. Eu nunca teria mergulhado de cabeça na área acadêmica se não

fosse pela EPGE, Escola de Pós Graduação em Economia da Fundação Getulio Vargas, à qual

sempre serei grato pela experiência e pelo aprendizado.

Agradeço ao apoio do meu orientador, professor Marco Bonomo, na realização deste trabalho, bem

como por ter me recomendado ao GVcepe – Centro de Estudos de Private Equity e Venture Capital

da FGV-EAESP, onde me juntei como pesquisador em 2007 e tive a oportunidade de participar

diretamente dos principais projetos na área de Private Equity e Venture Capital no Brasil.

A meu amigo e mentor, professor Cláudio Vilar Furtado, pela oportunidade de pesquisa no GVcepe,

bem como por seus ensinamentos e conselhos acadêmicos, professionais e pessoais nos últimos

anos, além de sua confiança em minha coordenação do projeto do 2° Censo e Estudo de Impacto

Econômico da Indústria Brasileira de Private Equity e Venture Capital (2º Censo).

Ao amigo, professor Roger Leeds, brasileiro de coração, pela oportunidade de pesquisa e constante

apoio acadêmico. Ao amigo, professor Rodrigo Lara, que dividiu comigo a responsabilidade de

conduzir o projeto do 2º Censo, e à nossa dedicada equipe de assistentes de pesquisa do GVcepe,

por confiarem que os resultados seriam alcançados.

A todos os meus amigos nestes 36 anos, do colégio ao mestrado, e em todos os lugares onde

trabalhei. Dedico este trabalho, também, à minha família, por todo o incentivo e, principalmente,

apoio. Em especial ao meu irmão, para que este trabalho lhe sirva de inspiração para alcançar seus

objetivos.

6

“Only those who dare to fail greatly can ever achieve greatly”Robert F. Kennedy

7

RESUMOO impacto positivo dos investimentos de Private Equity e Venture Capital (PE/VC) na economia e no

mercado de capitais está amplamente documentado pela literatura acadêmica internacional. Nos

últimos 40 anos, diversos autores têm estudado a influência desta classe de ativos na criação, no

desenvolvimento e na transformação de milhares de empresas ao redor do mundo, especialmente

nos Estados Unidos. Entretanto, os estudos sobre os determinantes da captação de recursos de

PE/VC têm se desenvolvido apenas mais recentemente, e seus resultados estão longe de ser uma

unanimidade.

No Brasil, a pesquisa sobre a indústria de PE/VC ainda é escassa. Embora a indústria local venha

crescendo rapidamente desde 2006, tendo alcançado US$36,1 bilhões em capital comprometido em

2009, ainda não há estudos sobre as variáveis que influenciam na alocação de capital pelos

investidores nesta modalidade de investimento no Brazil. Entender esta dinâmica é importante para o

equilíbrio e a eficiência de mercado.

Baseado no trabalho de Gompers e Lerner (1998) sobre os determinantes da indústria de PE/VC nos

Estados Unidos, este trabalho contribui com a literatura de PE/VC ao: (i) revisitar o começo desta

indústria no Brasil; e (ii) identificar quais as variáveis influenciam no desenvolvimento da indústria de

PE/VC local.

Os resultados deste estudo contribuem para o desenvolvimento acadêmico da indústria de PE/VC no

Brasil. Além disso, as discussões aqui apresentadas poderão impactar outras áreas de estudo que

são permeadas pelo tema, tais como Gestão de Investimentos, Governança Corporativa,

Empreendedorismo e Estratégia. Profissionais de mercado também deverão se interessar no

trabalho. As discussões sobre a história e os fundamentos da indústria fornecem aos investidores,

empreendedores, gestores de investimentos e formuladores de políticas públicas, entre outros, um

melhor entendimento sobre como o ecossistema de PE/VC funciona no Brasil.

8

ABSTRACTThe positive impact of the Private Equity and Venture Capital (PE/VC) investments in the economy

and in the capital markets is widely documented in the international literature. In the past 40 years,

several authors have investigated the influence this asset class in the creation, development and

transformation of thousands of companies worldwide, especially in the United States. However,

literature on the determinants of PE/VC fundraising has developed only recently, and their results are

far from being unanimous.

In Brazil, research about the PE/VC industry is still scarce. Although the local industry has been

growing fast since 2006 to achieve US$36.1 billion of committed capital in 2009, there are no studies

about which variables drive investor’s capital allocation in this asset class in Brazil. Understand this

dynamics is important to the market equilibrium and efficiency.

Based on Gompers and Lerner (1998) work about the determinants of this industry in the United

States, the present study contributes to the PE/VC literature by: (i) revisiting industry’s beginning in

Brazil, and (ii) identifying the variables which are related to the development of the local industry.

The results of this work contribute to the PE/VC academic development in Brazil. Moreover, the

discussions presented herein may impact some related fields of study, such as Portfolio Management,

Corporate Governance, Entrepreneurship, and Strategy. Practitioners may also be interested in the

study. The discussion about industry’s history and fundamentals provide investors, entrepreneurs,

fund managers and policymakers, among others, a better understanding of how the PE/VC ecosystem

works in Brazil.

9

LIST OF TABLES

1. Regulation Impact on PE/VC Investments 17

2. VC firms operating in Brazil in 1981 22

3. Breakdown of the Committed Capital Change from 2008 to 2009 (In US$ Million) 40

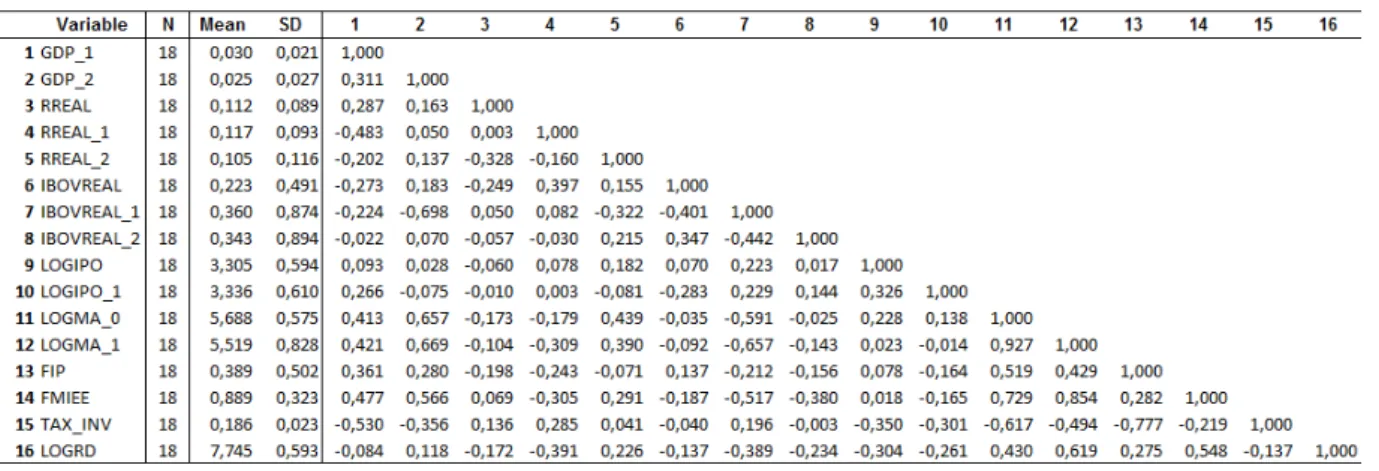

4. Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations – Industrywide 41

5. Regressions for Industrywide Fundraising 42

6. PE/VC Investment Vehicles used in the Individual Analysis 44

7. Means, Standard Deviations and Correlations – Individual Level 45

8. Regressions for Individual PE/VC Fundraising 46

LIST OF FIGURES

1. New Commitments to PE/VC in the U.S. from 1985 to 2012 18

2. PE/VC Fundraising in Europe: Sources of Capital (2012) 19

3. PE/VC Investment in Latin American Companies (1996-2000) – In US$ Billions 27

4. Evolution of Number of PE/VC Organizations Operating in Brazil 29

5. PE/VC Committed Capital to Brazil (In US$ Billion) 30

6. PE/VC Committed Capital to Brazil as Percentage of the GDP (In %) 30

7. Supply and Demand in PE/VC 31

8. Efficient Frontier 32

10

CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION 11

2. INDUSTRY OVERVIEW 12

2.1. What Is Private Equity? 12

2.2. What Do PE/VCs Do? 13

2.3. A Historical Background 15

3. THE EVOLUTION OF THE BRAZILIAN PE/VC INDUSTRY 20

3.1. 1960-1970: The Missing Link 20

3.2. 1970-1990 21

3.3. 1991-1994 24

3.4. 1995-1998 25

3.5. 1999-2000 27

3.6. 2001-2003 28

3.7. 2004 Onwards 29

4. THE FUNDAMENTALS OF PE/VC FUNDRAISING 30

5. MODEL 37

5.1. Industrywide Fundraising 40

5.2. Individual PE/VC Firms Fundraising 45

6. CONCLUSIONS 48

REFERENCES 50

11

1. INTRODUCTIONIt is well documented the support of Private Equity and Venture Capital (PE/VC) on the creation and

development of highly successful innovative businesses worldwide. PE/VC not only provides funding

to startups and SMEs (small and medium enterprises), but also brings a whole package of valuable

strategic resources that reduces companies’ mortality rates.

The fast growing importance of the Brazilian PE/VC industry urges a better understand of its evolution,

dynamics and key elements in order to support policy-making initiatives, investors decisions, and

entrepreneurial choices, among others. Notwithstanding its importance, Brazil still lacks on academic

research about it.

This work presents a historical review of the PE/VC evolution in Brazil, with new evidences regarding

its birthdate and timeline. The beginning of the Brazilian PE/VC industry is replaced in mid-1960s, not

in the 1970s or even in 1980s as widely acknowledged, showing that an important part of its history

has been long time forgotten. The U.S. industry, especially in its early days, is revisited as a valuable

tool to understand today’s Brazilian market structure and its economic determinants. I expect that an

organized review of the history (and the literature) will contribute to future studies about the PE/VC in

Brazil. Moreover, I believe that this dissertation can help practitioners and policy-makers to better

understand the beginning and development of the PE/VC industry in Brazil, in order to think about its

future.

As chapters two, three and four shad a light on those recurring variables present during the evolution

of PE/VC industry worldwide, they offer a background to chapter five. Based on Gompers and Lerner

(1998), an equilibrium model and the main variables that influence the PE/VC fundraising are

identified, tested and discussed for industry and individual levels in chapter five. The conclusion is

12

2. INDUSTRY OVERVIEW2.1. What Is Private Equity?

Private Equity (PE), in its strictest definition, refers to equity investments in non-listed companies,

regardless the legal structure is being used. Due to their illiquid nature, long investment period and

informational asymmetry characteristic, PE assets have different risks and returns compared to

traditional ones, and therefore constitute an alternative asset class1. Its high-risk high-reward

investment characteristic held back its broad adoption as a usual asset among institutional investors

until the 1970’s (Gill, 1981; Gompers, 1994; Gompers and Lerner, 2002; Anson, 2006; Metrick, 2007;

EVCA, 2007; Mathonet and Meyer, 2008).

PE investments have been usually divided between Venture Capital (VC) and Buyout, with the former

referring to minority equity stakes in companies in their initial stages of development, and the later

referring to control acquisition of companies at a more mature stage of development. However, it does

not mean that a controlling equity stake can’t be acquired from startups or a minority stake from a big

traditional company – it was just unusual during the early days of the PE/VC industry in the United

States (U.S). As consequence, the VC term established itself as a “brand” for investments in startups

and early stage businesses and PE for later stage ones, as they were two separate things (which they

are simply not). Although it is clear that VC is a PE type of investment, they began being used as two

separated things throughout the decades. It is difficult to precise when startup/early stage-oriented

private investments started to be called Venture Capital.

According to Harper (2010),

The term “venture” has its origin in mid-1400s, meaning “to risk the loss” (of something),

shortened form of aventure, itself a form of adventure, which meant “chance, fortune, luck” in the early 1200s. An original meaning of adventure was “to arrive”, in Latin, but it took a turn through “risk/danger” (a trial of one’s chances), and “perilous undertaking” (early 1300s)

and “a novel or exciting incident” (1560s). The word venture as a general sense of “to dare, to presume”, is recorded from 1550s, as a noun sense of “risky undertaking” it is first recorded in the 1560s and as a meaning of “enterprise of a business nature” is recorded

from 1580s.

1 Alternative assets include financial assets such as commodities, hedge funds and derivatives, in addition to

13

Ellis and Vertin (2001) attribute the term Venture Capital to Benno C. Schmidt in the 1960s, whileBolton and Thompson (2000) indicate Arthur Rock as the “creator” of the VC term in the same decade.

However, an earlier use of the term is noted by Reiner (1991) when Jean Witter, partner of Dean

Witter & Co, mentioned it during his speech on the Investment Bankers Association of America

convention in 1939. Alternatively, Avnimelech et al (2004) attribute the earliest use of the term to

Lammot du Pont, president of Du Pont, in 1938; although they also note that the use may already

have been circulating among Boston academic mainstream earlier. Indeed, the earliest notation of the

term found during the present work literature review appeared in 1925 on a subcommittee formed by

academics and other distinguished members of New England’s society, as mentioned by Ante (2008).

Hereon, I will use the term PE/VC when referring to the industry or to the asset class in general, VC to

startup/early stage investments, and PE to late stage/buyout investments, unless specifically noted

and/or explained in the text.

2.2. What Do PE/VCs Do?2

The PE/VC industry has supported the creation and development of many revolutionary enterprises in

the Human History, such as Digital Equipment Corporation, Fairchild Semiconductors, Genentech

Google, Microsoft, Netscape, Apple, eBay, Amazon, Sun Microsystems, Yahoo, Intel, among others.

Notwithstanding it is usually associated with leading edge technological projects, the PE/VC industry

has also backed a large number of innovative “traditional” service companies, such as Staples,

Starbucks, FedEx and Home Depot (Bygrave and Timmons, 1992; Gompers, 1994; Gompers and

Lerner, 2001b; Gompers and Lerner, 2002; Bottazzi and Da Rin, 2002; Metrick, 2007; Boyle and

Ross, 2009).

An important aspect of the PE/VC investment is that it can benefit startups and SMEs that normally

would have difficult to access traditional financing sources, especially in emerging markets, due to

their lack of tangible assets to use as collateral. (Premus 1985; Gompers, 1994; Gompers and Lerner

2001a; Gompers and Lerner 2001b; Hall 2002; Smith and Smith 2002; Leeds 2003; Ribeiro and Tironi,

2Subtitle inspired on the title of Michael Gorman’s andWilliam Sahlman’s influential paper “What Do Venture

14

2007). Different from bank loans and short term debts, PE/VC will share upside and downside riskswith the entrepreneur by taking an equity stake in the company and becoming a partner committed to

its strong and sustainable growth (Engel, 2002; Gompers, 1994).

Sorensen (2007) suggests that PE/VC invests primarily in entrepreneurial innovative companies and

that it has substantial impact on development of new technologies, and Premus (1985) demonstrates

that PE/VC and technological innovation growths are correlated. Kortum and Lerner (2000) show that

PE/VC-backed companies are involved in important innovations based on patent amount in the U.S.,

while Bowonder and Mani (2002) show the impact of PE/VC on financing innovation in India, and

Tykova (2000) demonstrates a positive relation between patents creation and PE/VC investments in

Germany.

According to Keuschnigg (2009), policy makers have been fostering favorable conditions through

PE/VC to creating businesses. Gompers (1994) remembers the importance of the changes in the

1979 Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) and the consequent increase of pension

funds’ commitments to PE/VC in the U.S. Another example comes from Hirukawa and Ueda (2008)

that highlight the Yozma program in Israel and the Small Business Investment Company (SBIC) in the

U.S.

SMEs accounts for over 95% of all private companies and are a major source of job creation,

innovation and economic growth in the U.S. (Bygrave and Timmons, 1992; Leeds, 2003). It

corresponds to over 50% of the U.S GDP and around 20% of the Brazilian GDP (Ramalho et al,

2011). Lerner (2002) agrees that government is highly interested on fostering innovation and support

the PE/VC activity is a natural way to accomplish that goal, and Gompers (1994) notes that promoting

an efficient PE/VC industry should be the goal of any Administration. On the other hand, Brander, Du

and Hellmann (2010) provide evidence that an extensive government support (or even a null support)

15

2.3. A Historical BackgroundQueen Isabella of Castile made a PE/VC investment on Christopher Columbus’ endeavor in 1485, one

year after King John II of Portugal refused to invest on it. Such as today’s PE/VC investments, Queen

Isabella not only provided the capital to the voyage but also management and recruitment assistance,

in addition to profit sharing (Pavani, 2003; Mathonet and Meyer, 2008). Although Anson (2006) also

recognizes Columbus endeavor contribution to the PE/VC history, he suggests that the structure and

bases for modern PE/VC investments started to be created in the 1800s in the United Kingdom (U.K)

due to the Industrial Revolution.

2.3.1. The United States of America (U.S.) and the Rise of the PE/VC Industry

The first seeds of the PE/VC industry as we know today were planted in the U.S. at the end of 1800s

and the beginning of the 1900s when the country started to develop as an integrated nation and

economy. The offices that managed wealthy families’ assets (supply of capital) were making direct

equity investments in new non-public traded companies (demand for capital) such as AT&T and

Xerox. Those wealthy families were the Rockefellers, Vanderbilts, Phippses, and Whitneys among

others (Bygrave and Timmons, 1992; Gompers and Lerner, 2001a).

After the 2nd World War, there was a clear equity gap in the market: emerging companies needed

capital to finance their projects but the supply of capital was not institutionalized yet. It was only a

matter of time for the economic forces available to start moving towards an equilibrium model. In June

6th of 1956 a group of businessmen, politicians and academics3 joined forces to create a new way to

finance new technology startups. They constituted the American Research and Development

Corporation (ARD) as a close-ended public traded fund, with Georges F. Doriot4 as its president. On

March 8th of 1961, ARD was the first VC firm admitted for trading on the New York Stock Exchange

(NYSE) and in 1966 ARD did the IPO of Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), which is considered the

first “home run” (i.e. a huge success) in the PE/VC history. ARD invested US$ 70,000 for 77% of

DEC’s common stocks in 1957 and by 1971 it was valued at US$ 355 million, contributing with half of

3 Karl Compton, president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Ralph Flanders, head of

Vermont’s Jones & Lamson Machine Company, Merrill Griswold, chairman of Securities and Exchange Commission, and Donald David (HBS dean), former members of New Products Committee.

4

16

the impressive 15.8% annual IRR of ARD over 25 years of operations. ARD was sold to Textron in1972 as way to deal with SEC regulation pressures as well several organizational problems (Bygrave

and Timmons, 1992; Fenn et al, 1998; Gompers and Lerner, 2001a; Metrick, 2007; Ante, 2008).

Ante (2008) notes that early in 1940s other VC firms were created by wealthy families: J.H Whitney &

Company and Rockefeller Brothers Company, although he also points ARD as the first VC firm to

raise money from nonfamily sources such as institutional investors. John Hay “Jock” Whitney was

investing his family money since 1930s and decided to form J.H. Whitney & Co. in 1946. Only in 1990

J.H. Whitney & Co. decided to raise money outside the Whitney family (i.e. from foundations,

universities, pension funds etc.); it is notably the oldest PE/VC firm still operating the market (Wilson,

1986; Ellis and Vertin, 2001; JHW, 2010).

In 1958 the U.S government released the Small Business Act which created the Small Business

Administration and established the Small Business Investment Companies (SBIC) program. The SBIC

program allowed leveraging four low-interest Government dollars for each dollar invested in small

businesses, which attracted a lot of new players to the VC industry. By 1962, an impressive amount of

585 SBICs were authorized to operate in the U.S industry. Although the SBIC was a pioneer program

which fostered the development of a pool of new professionals in the VC industry, there were many

problems such as underestimation of the hard work needed (e.g. company monitoring) and misleading

deal structuring (i.e. large amount of debt instead of equity). The 1974-1975 Oil Crisis was the coupe

of the grace for many SBIC-backed companies that couldn’t survive with their high leveraged capital

structure in the face of declining sales and negative cash flow environment (Bygrave and Timmons,

1992).

The 70’s was a very difficult time for the VC industry in the U.S., and by the early 1980s, the PE/VC

industry was basically a VC phenomenon. However, during the 80’s industry’s focus shifted radically

to mega deals, mainly leveraged buyouts (LBOs), such as RJR Nabisco which was acquired for

US$25 billion. It was probably during that time that PE started to be used as a synonym of Buyouts

due to the mergers and acquisitions (M&A) frenzy with the large LBOs deals. The market also started

17

investment strategy (i.e. mezzanine, LBOs, etc). In addition, the limited partnerships establishedthemselves as the mainstream legal structure in the U.S. market (Bygrave and Timmons, 1992).

A series of new regulations and clarifications of existent ones (see table 1) were responsible for a

major shift in the investment flow toward the PE/VC industry in the U.S (Bygrave and Timmons, 1992;

Gompers, 1994; Gompers and Lerner, 2001a; Lerner, 2002).

Table 1 - Regulation Impact on PE/VC Investments

Regulation Notes

Small Business Act (1958) Increased the availability of VC for small businesses. Employment Retirement Income

Security Act (ERISA) of 1974

Discouraged plan fiduciary incentives for high-risk investments. As consequence, pension funds avoided PE/VC investments.

Revenue Act (1978)

Reduced the prevailing capital gains tax rate from 49.5% to 28%, thereby creating the first major tax incentive for long-term equity investments since the 1960s.

ERISA’s “Prudent Man” Rule

clarification (1979)

The Rule governing investment guidelines for pension fund managers was revised and clarified. It ruled that taking into account portfolio diversification was prudent.

Small Business Investment Incentive Act (1980)

Redefined PE/VC organizations as business development companies, removing the need to register as investment advisers with the SEC.

ERISA’s “Safe Harbor” Regulation

(1980)

Stated clearly that PE/VC fund managers would not be considered fiduciaries of pension assets invested in the limited partnerships that they managed.

Economic Recovery Tax Act (1981) Lowered further the capital gain tax rate paid by individuals from 28% to 20%.

Tax Reform Act (1986) Reduced incentive for long-term capital gains. Source: Bygrave and Timmons (1992); Gompers and Lerner (2001a)

Once again, leveraged by the “hot” stock market, the PE/VC industry in the U.S reached its peak in

1987; there were more than 700 PE/VC organizations, and investments of US$ 3.9 billion made in

over 1,700 companies. Even the SBICs had recovered and reached 450 investment firms at that time.

After the stock market crash in October 1987, the U.S economy was facing a recession, and the oil

prices increase due to the Gulf War was not helping the scenario. By mid-1990s one-third of all SBICs

had gone into liquidation again (Bygrave and Timmons,1992). The early 1990s was a challenging

18

Figure 1. New Commitments to PE/VC in the U.S. from 1985 to 2012Source: NVCA (2013)

In the 90’s, the PE/VC activity started to recover fast due to the internet and technology businesses

exponential growth, and reached US$4.1 billion in 1994 and US$7.6 billion in 1995. The 1995 to 2000

is widely considered the boom period of the VC segment when the investments in the U.S reached

US$105.9 billion (Bygrave and Timmons, 1992; Metrick, 2007). With the internet bubble burst in 2000,

followed by the September 11th of 2001 terrorist attacks, the PE/VC activity slowed again. It would

recover again in the following years only to collapse again in 2008 due to with the financial markets

crisis. In 2012, venture capital under management in the U.S. reached US$199.2 billion while the total

dry powder of U.S. PE/VC organizations reached US$946 billion5 (NVCA, 2013; PEGCC, 2013).

2.3.2. Europe and Emerging Markets

By the late-1970s PE/VC was virtually non-existent in Europe, and in the late 1980s the United

Kingdom (U.K) was the only relevant market. Moreover, early initiatives were government driven such

as National Research and Development Corporation (NRDC) in the United Kingdom (U.K.) and

European Enterprise Development Company (EED) in France (IFC, 1981; Souza Neto and Stal, 1991;

Ante, 2008; 3i, 2010). In the 1980s, the rest of Europe lacked in an active, or even a minimum

structured, PE/VC industry. For example, although the first PE firms in German were formed in the

1960s as arms of commercial banks, PE was only a small industry in German until mid-1980s (Von

5 Includes venture capital, real estate, mezzanine, growth capital, distressed private equity and buyout. Dry

19

Drathen, 2007). In the early 1980s there was only two PE firms in Spain: the Sociedad Espanola deFinanciacion de la Innovacion (Sefinnova) formed in 1978 by Banco de Bilbao and other local

investors, and supported by IFC and the Spanish Government; and Fomento de Inversiones

Industriales, a PE arm of Banco Español de Credito, the largest Spanish bank at that time (IFC, 1981).

During the 1990s many U.S. PE/VC organizations started to expand their activities in Europe looking

for better returns and risk diversification (Lerner, 2001). It helped the European industry to expand

fast, although the market growth wasn’t homogenous across the continent (Bygrave and Timmons,

1992; Martin, Sunley and Turner, 2002). Even today U.S. investors play a key role in the European

PE/VC industry. In 2012, U.S. corresponded to almost 40% of the new commitments in the Region as

shown in graph 2. Private Equity and Venture Capital under management in Europe is estimated in

US$555 billion as of 2012 (EVCA, 2013).

Figure 2. PE/VC Fundraising in Europe: Sources of Capital (2012)

Source: EVCA (2013)

Bygrave and Timmons (1992) recognize the efforts of spread the PE activity over the Emerging

Markets during the 1980s, especially through the efforts of the World Bank and the International

Finance Corporation (IFC). The authors also note the difficult and challenges due to the lack of

20

in the expansion of the international PE/VC markets. Looking for better results in the 1990s, the U.S.PE/VC organizations also entered in the Emerging Markets, i.e. Latin America and Asia (Lerner,

2001). From 2010 to 2012 Emerging Markets PE/VC fundraising totalized over US$254 billion (Preqin,

2013), while in 1988 Emerging Markets total committed capital was only US$350 million (Bygrave and

Timmons, 1992).

3. THE EVOLUTION OF THE BRAZILIAN PE/VC INDUSTRY

We can trace back the origins of the Brazilian PE/VC industry to Pedro Alvares Cabral and Portugal’s

investment in its (ad)venture. Such as in the U.S, the concept of the modern PE/VC started to develop

during the early industrialization of the country during the 1920s, when wealthy families were making

private investments.

Between the 1950s and 1960s, Brazilian businessmen were investing in traditional industries such as

textiles, furniture, food and construction, while multinationals were entering the market to produce

consumer goods. Brazil was building a diversified economy which would be very important in the

following decades for the structuring and consolidation of its PE/VC industry. Due to the imports

substitution program implemented by the Government, the state-owned companies supported the

development of their products and services supply chain. As consequence, many SMEs flourished

offering a potential fertile ground for PE/VC investments (Souza Neto and Stal, 1991).

I found that the beginning of the modern Brazilian PE/VC industry can be traced back to the 1960’s,

although the literature used to point toward mid-1970s/1980s (Gorgulho, 1996; Romani, 1997;

Bezerra, 1999; Checa et al, 2001; Pavani, 2003; Freitas and Passoni, 2006; Sousa, 2008).

3.1. 1960 – 1970: The Missing Link

The Brazilian PE/VC industry began in September 24th of 1964 with the creation of the Adela

Investment Company S.A. (AIC), one year after the Atlantic Community Development Group for Latin

America (ADELA) was formed as a task force of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) led by

21

SMEs, sell its interest once those became well established, and reinvest the proceeds in other newventures. It would apply market principals and seek out profitable projects with a high impact on the

local economy, with no political or philanthropic orientation (U.N, 1965; Fox, 1996; Rivera, 2007; Boyle

and Ross, 2009).

AIC raised US$16 million from some 50 corporate shareholders in 12 countries, including U.S,

Canada, Western Europe and Japan. Each shareholder investment would range from US$100,000 to

US$500,000. Eventually, AIC attracted 240 corporate shareholders from 23 countries, including

Brazil6. It was created as a holding company with an authorized capital of US$100 million and a

30-year corporate life. (Boyle and Ross, 2009). It made its first investment in Brazil in 1965, and in 15

years it made a total of 22 PE/VC investments (US$ 23 million) in the country. After investing a total of

US$122 million in 141 deals throughout Latin America, AIC closed its operations in 1980 due to

financial liquidity problems.

Another early initiative in the country was led by the International Finance Corporation (IFC) which

was created by the World Bank in 1956 to support developing economies. In 1966-1967 the IFC

started to make direct equity (public and private) investments around Latin America, including Brazil,

in order to foster the region economies in addition to develop the local capital markets. (U.N, 1965).

3.2. 1970 – 1990

In 1974 the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES) created three subsidiaries to provide capital to

SMEs and to support the national industrial development policy: (i) Insumos Básicos S.A (Fibase), (ii)

Investimentos Brasileiros S.A (Ibrasa), and (iii) Mecânica Brasileira S.A (Embramec). In 1982, these

companies were merged into a new company called BNDESPar which would be important to the

Brazilian PE/VC industry in the following decades (Gorgulho, 1996; Pavani, 2003).

In 1976, the Brazilian Innovation Agency (FINEP) created a program called Apoio ao Desenvolvimento

Técnico da Empresa Nacional (ADTEN) in order to foster technological innovation on SMEs through

6

22

VC investments. However, ADTEN mostly used subsidized traditional debt, instead of equity, on itsnearly 60 (underperforming) investments. FINEP then decided to discontinue the program in 1991 and

only reinstate it after organize an efficient monitoring and controlling system (Souza Neto and Stal,

1991; Gorgulho, 1996).

Table 2. VC firms operating in Brazil in 1981

Begin Ownership Notes

ADELA – Empreendimentos e Consultoria 1967 Private

ADELA was looking for opportunities in Brazil since 1964, made its first investment in 1965, and established its local operations in 1967

COBESA – Cia. Brasileira de

Empreendimentos 1973 Private

IBRASA, FIBASE and EMBRAMEC 1974 State Reorganized under BNDE in 1981 Brasilpar – Comércio e Participações 1975 Private

Brazilinvest S.A. Investimentos,

Participações e Negócios 1976 Private

33.33% private Brazilian groups, 33.33% Brazilian Government and 33.33% international companies

Minas Gerais Participações (MGI) 1976 State Multipar – Empreendimentos e

Participações Ltda 1977 Private

Promoções e Participações da Bahia

(PROPAR) 1977 State It used preferred shares and made minority equity investments Brasilinterpart Intermediações e

Participações S.A 1979 Private Brazilian Government, Brazilinvest, ADELA and several local and foreign shareholders Source: IFC (1981)

Also in 1976, Brasilpar was formed due to a partnership between Unibanco and Paribas Bank to make

VC investments, in an initiative supported by Roberto Teixeira da Costa, the first president of the

Brazilian Securities Exchange Commission (CVM). It was structure was a holding company which

invested US$ 4 million until 1980, when it was restructured to admit new partners7. The capital then

was raised from US$ 4 million to US$ 10 million (Gorgulho, 1996).

In 1981, the first PE/VC international seminar was organized in Brazil. One of its outputs was a

regulation proposal aimed to foster and structure the local PE/VC industry. The proposal was sent to

the Congress but it did not receive any attention. According to IFC (1981), in 1981 there were 9 VC

firms operating in the Brazil of which 6 private owned and 3 state-owned. In addition, Montezano

(1983) notes Monteiro Aranha S.A. and PHIDIAS Administração e Participações S.A. operating in

7 Roberto Teixeira da Costa, IFC, Villares Group, Pão de Açúcar, Brasmotor, and João Fortes Engenharia

23

Brazil as of 1982, while Leonardos (1985) also notes the operations of Riopart and Property as of1983.

The 1980s and the early 1990s was marked by hyperinflation and economic recession that inhibited

any long term investment, especially private ones in startups and SMEs. It is almost impossible to

imagine that a PE/VC industry could flourish during such difficult times. Nevertheless, in 1981, Ary

Burger, former president of the Southern Region Development Bank (BRDE) and former director of

the Brazilian Central Bank (BACEN), created the Companhia Riograndense de Participações (CRP). It

raised money from local private investors, BRDE and Rio Grande do Sul Development Bank

(BADESUL)8 under a holding investment vehicle called PARGS. From 1981 to 1990, CRP invested

US$ 5.2 million (US$ 2.5 million from the shareholders and US$ 2.7 million from capital gains) in 40

deals (Gorgulho, 1996).

During the 1980s, Jorge Paulo Lemann, Carlos Alberto Sicupira and Marcel Hermann Telles, partners

of Banco Garantia, bought out Lojas Americanas (1982) and Cervejaria Brahma (1989) using their

own money. It was their first experience of what would become GP Investimentos in 1993 (Bezerra,

1999).

At that time, the Brazilian PE/VC industry lacked in adequate tax stimulus and regulatory framework.

Only in 1986 the PE/VC activity was benefited by the Decree-Law 2,287 which was regulated by the

Resolution 1,184 of 1986 and the Resolution 1,346 of 1987. The new regulation recognized as a VC

firm (called Sociedades de Capital de Risco) those investment companies focused exclusively on the

acquisition of minority stakes from SMEs. The VC firms would benefit from several tax exemptions and

incentives (Gorgulho, 1996; Pavani, 2003; Sousa, 2008). Although that regulation was initially a good

idea in the beginning it proved to be unsustainable since: a) it excluded medium to large sized

companies; b) it didn’t allow use debt instruments; c) the BACEN capital gain regulation was

incompatible with a VC firm; d) the 7,714 Act of 1988 cancelled the tax benefits. As consequence,

there were just a few VC initiatives under the Decree-Law 2,287 which were ultimately discontinued

(Costa and Lees, 1989; Gorgulho, 1996; Pavani, 2003). For example, ACEL Sociedade de Capital de

8

24

Risco, from Rio de Janeiro and focused on technological companies, and PAD Investimentos, fromSão Paulo and focused on companies with differentiated products and services, made less than 10

investments and ended their operations in the beginning of the 1990s (Gorgulho, 1996). According to

Costa and Lees (1989), as of July 1988 there were 15 VC firms operating in Brazil with a committed

capital of US$150 million9.

3.3. 1991 – 1994

In the beginning of the 1990s, the Brazilian Government began several structural reforms, such as

trade liberalization, industries deregulation and privatization that would pave the next decade for the

economic development in the country. Nevertheless, it was a problematic period due to high inflation

rates, unemployment, unsuccessful economic stabilization plans, corruption scandals and presidential

impeachment.

Notwithstanding the difficulties, the PE/VC continued to develop in the country. In 1990, CRP formed a

new holding company called CADERI to accommodate the International Investment Corporation (IIC),

a subsidiary of the Inter-American Development Bank (IBD) and 5 private corporations10. The holding

investment company had a 14-years term and a capital of US$ 6.5 million (Gorgulho, 1996).

In July 1991 BNDESPar created a special vehicle to support technological SMEs through minority VC

investments (including convertible debentures) called Condomínio de Capitalização de Empresas de

Base Tecnológica (CONTEC), which also incorporated 4 companies that were previously directed

invested by BNDESPar from 1988 to 1990. The CONTEC was later restructured and renamed under a

new brand (Programa de Capitalização de Empresas de Base Tecnológica). From 1991 to 1994,

BNDESPar, under the CONTEC program, analyzed 300 opportunities and invested in 24, including

two VC firms in 1993: CRP and Pernambuco Participações S.A. (Souza Neto and Stal, 1991;

Gorgulho, 1996).

9

Includes Acel Investimentos, Arbi Participações, Brasilpar, Brazilian Venture Capital (BVC), Citicorp Venture Capital (CVC), Companhia Riograndense de Partipações (CRP), Credibanco Participações and Partbank. Excludes BNDESPar (Costa and Lees, 1989).

10

25

CRP’s CADERI increased its capital to include BNDESPar (in 1993) and IFC (in 1995) as investors,and by the end of 1995 it had a total capital of US$ 10.5 million to make VC investments (Gorgulho,

1996). Pernambuco Participações S.A. was also structured as a holding company to make VC

investments in Pernambuco, Alagoas, Paraíba and Rio Grande do Norte. It raised US$ 8 million from

81 Northeast corporate investors and BNDESPar (Gorgulho, 1996; Pavani, 2003).

Before 1994, there wasn’t any PE/VC investment vehicle structured as a Limited Partnership (LP) and

managed by a Brazilian PE/VC firm. GP Investimentos was first local player to raise a LP vehicle,

called GP Capital Partners I (GPCP I), which was the largest Brazil-focused fund ever raised with

US$500 million of committed capital Its international investors included large U.S endowment funds

such as Yale University and Cornell University. In order to show full commitment to the project and

reduce investors’ risk aversion to the Brazilian history of economic problems GP Investmentos’

partners needed to commit 20% of the fund with their own money (Bezerra, 1999; Checa et al, 2001).

From 1991 to 1994, total PE/VC commitments to Brazil amounted US$1.1 billion, of which US$578

million only in 1994 (Checa et al, 2001; De Carvalho et al, 2006). In 1994, the Brazilian Government

finally succeeded on inflation control with the Real Plan. However, the interest rates continued at high

levels, which difficult the corporate credit and limited the sustainable growth of the economy. In 1994

the Brazilian Securities Exchange Commission (CVM) released the Rule 209. It has created a

regulation which allowed institutional investors to make PE/VC investments in SMEs. However, the

major interest from the investors at that time weren’t on SMEs, but on larger companies.

3.4. 1995 – 1998

During the period from 1995 to 1998, Brazil experienced the development of its PE/VC industry due to

the economic stability in addition to the new business opportunities that arose from the privatizations.

Brazil saw the fundraising of large PE investment vehicles dedicated to Latin America or Brazil by

international players for the first time such as Advent International, AIG Capital, Darby International

and West Sphere to name a few. During this period, the large international PE firms saw Latin

America as a call option: they could allocate a small percentage of their global PE funds which would

26

In the late 1990s international players were operating in Brazil through regional vehicles. With thisstrategy they could tiptoe in Brazil without invest in a local office (Bezerra,1999). Later on, some

players decided to commit themselves to the Brazilian market and started to strength their local

presence by hiring a local team. The first movers were the PE/VC arms of international investment

banks. As noted by Checa et al (2001), those players were more flexible them traditional PE/VC

organizations, especially since they were investing their own money. Examples were Bank Boston and

Chase Capital Partners, which became JP Morgan Capital Partners.

In 1994, Patrimônio, an M&A advisory group formed in 1988 in partnership with Salomon Brothers,

creates its PE arm. In 1997 it launches Patrimônio Brazil Private Equity Fund I, a US$235 million fund

in partnership with Bank Oppenheimer (later acquired by the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce).

In 1995 Brasilpar in partnership with WestSphere raised a PE/VC fund, and Banco Bozano,

Simonsen, in a partnership with Advent International raised the Bozano, Simonsen-Advent fund, the

first FMIEE created in Brazil. Brasilpar sold its PE/VC operations (BPE) in 1996 to the WestSphere

which raised US$ 220 million in the South America Private Equity Fund that year (Pavani, 2003).

In 1997 Brazil also saw the creation of its first billion dollar fund, the CVC/Opportunity, a partnership

between Citibank Venture Capital (CVC) and the Opportunity, a local asset management. The fund

aimed to invest in the privatizations. In that year, GP Investments has also fund-raised its second PE

fund, called GP Capital Partners II (GPCP II), which amounted US$ 800 million. In 1998, Hicks, Muse,

Tate & Furst raised a US$964 million fund (Romani, 1997; Checa et al, 2001)

From 1995 to 1998, large regional funds were raised to Latin America: Advent International, AIG

Capital Partners, Darby Overseas and WestSphere entered the market in 1995 and 1997. The 1996 to

1998 was characterized by PE buyouts on industries such as telecom, transportation, cable television,

and retail. The 1999 and 2000 the VC, especially focused in high-tech and internet companies, was

27

Figure 3. PE/VC Investment in Latin American Companies (1996-2000) – In US$ BillionsSource: Checa et al (2001)

In 1998, the BNDES created a program called Valor e Liquidez which aimed to improve the Corporate

Governance. This program would have an important influence not only in the stock market, but also in

the PE industry. They outsourced the management of some portfolio companies. In addition, the

investments were Private Investments in Public Equity (PIPE). The first was the Dynamo Puma in

1998.

According to Bezerra (1999), there were 55 PE/VC organizations investing in Brazil as of 1999. Only 4

of them with a committed capital around a US$1 billion figures: CVC/Opportunity, GP Investimentos,

Hicks, Muse, Tate & Furst (spread over Latin America) and Exxel Group (mostly Argentina). The rest

of the industry accounted for committed capital between US$100 million and US$ 400 million. Bezerra

(1999) estimates the Brazilian PE/VC industry around US$ 4 billion to US$ 6 billion as of 1999. At that

time, one third of the PE/VC organizations operated from abroad.

The wave of financial crisis in the end of 1997 and in 1998 around the globe brought turbulence to the

Brazilian financial markets and forced the country to change its cambial regime in the beginning of

1999. That volatility led to a significant decrease in new PE/VC commitments to the country during

1999, especially from the international players.

3.5. 1999 – 2000

During the late 1990s the investments in startups and SMEs were put aside in spite of the CVM Rule

28

characterized by the fast growth of the internet and electronic commerce. PE/VC allocation tohigh-tech companies was leveraged by the success of companies such as StarMedia, Terra Networks and

El Sitio (Checa et al, 2001).

During this period, investments jumped from US$ 200 million in 1997 to US$ 1.1 billion in 2000, and

78 of 118 deals in the 2000 were internet related (Stein et al, 2001). Checa et al (2001) attribute to the

privatizations in the 1990s the first interest from the Brazilian pension funds to invest in PE/VC. They

note that before 1997 the pension funds weren’t allowed to invest in PE/VC, and by definition on some

of the privatization underway. Hence, the regulation was changed. From 1997 to 1999 few major

pension funds11 committed US$445 million in four local PE/VC organizations: CVC/Opportunity Equity

Partners, CSFB-Garantia, Banco Patrimônio and Santander Investments (P&I, 1999). Facing the a

fast growing local PE/VC industry, the Brazilian Venture Capital and Private Equity Association

(ABVCAP) was created in 2000 under the name of Associação Brasileira de Capital de Risco (ABCR),

which was changed in 2005 to ABVCAP. However, the Brazilian PE/VC industry had a setback with

the internet bubble burst in the end of 2000.

3.6. 2001 – 2003

This period was once again a difficult time to the industry. Following the internet market crash in 2000,

the world faced the September 11 event in 2001. In addition, the Brazilian energy crisis in 2001 and

the presidential elections in 2002 brought back high volatility to the local financial markets with

exchange rate overshooting and increase in the interest rates.

The Brazilian PE/VC industry restructured itself as part of its natural evolution. With their portfolio

companies in distressed, several local and international PE/VC organizations closed their operations

or wrote-off part of their portfolios. According to Ribeiro (2005), there was a write-off of 35 investments

in addition to 10 companies that were sold back to the entrepreneurs.

11 Fundação dos Economiários Federais (FUNCEF), Fundação Sistel de Seguridade Social (SISTEL), Fundação

29

In 2003 the Brazilian Securities Exchange Commission (CVM) released Rule 391. It created a newregulation for PE/VC investments in Brazil, allowing institutional investors increase its allocation to

PE/VC. In 2003 the Private Equity and Venture Capital Research Center at FGV-EAESP (GVCEPE)

was founded, a pioneer initiative led by professor Claúdio V. Furtado with the seed money of five

PE/VC organizations12.

3.7. 2004 Onwards

In 2005, the Brazilian PE/VC industry was growing again. In that year, GVCEPE supported and

sponsored the first broad and complete survey about the Brazilian PE/VC industry ever made.

Leonardo L. Ribeiro, under the academic supervision of professor Antônio Gledson de Carvalho and

the support and coordination of professor Cláudio V. Furtado, published the 1st Census of the Brazilian

Private Equity and Venture Capital Industry (see De Carvalho et al, 2006). It was an important

breakthrough in the Brazilian PE/VC industry.

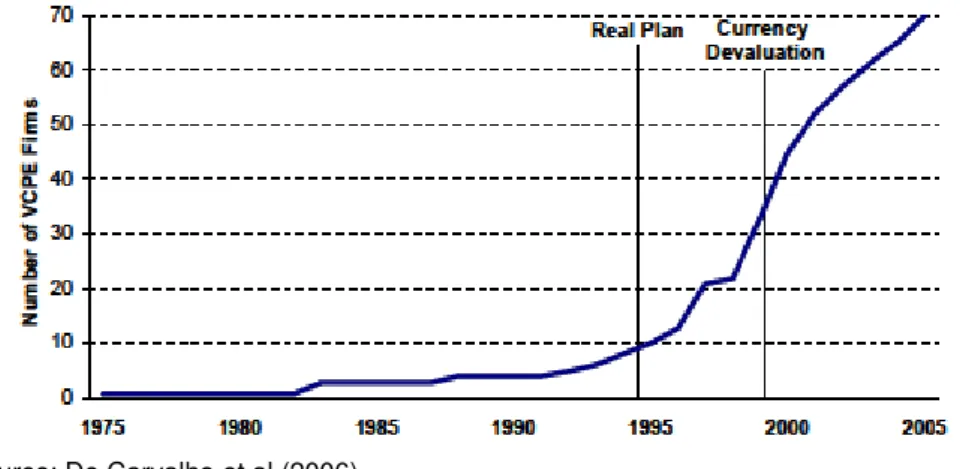

Figure 4. Evolution of Number of PE/VC Organizations Operating in Brazil

Source: De Carvalho et al (2006)

In 2009, GVCEPE conducted the 2nd Census and the Economic Impact Study of the Brazilian Private

Equity and Venture Capital Industry, headed by professor Cláudio V. Furtado and coordinated by

Rodrigo Lara and I. It updated and expanded all the information available regarding the Brazilian

PE/VC industry as of December 2009. All the statistics and other information were extensively

documented in a 412-pages book (see Ramalho et al, 2011 for more information).

30

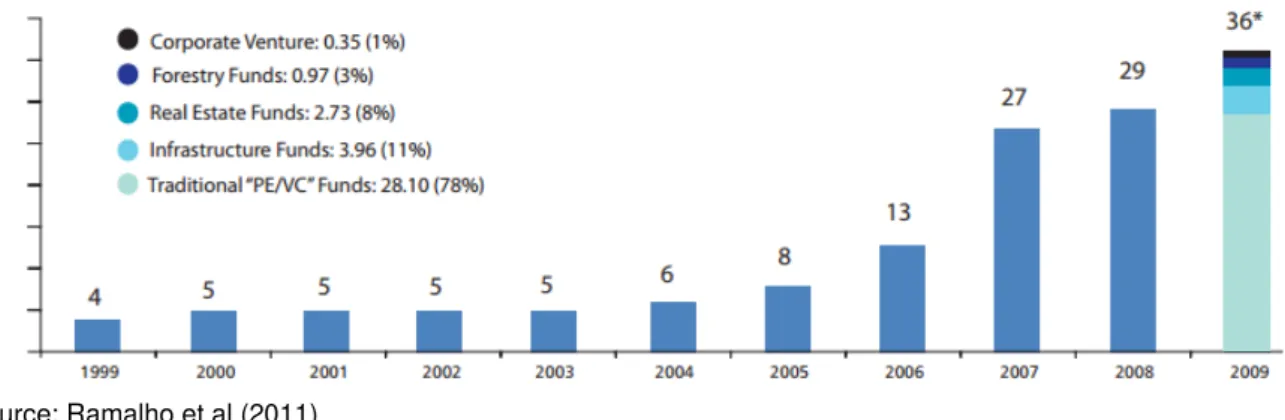

Figure 5. PE/VC Committed Capital to Brazil (In US$ Billion)Source: Ramalho et al (2011)

In December 2009 the local PE/VC industry reached US$36.1 billion of committed capital which

represented 2.3% of the Brazilian GDP (versus 1.0% in 2004). As of December 2009, the Brazilian

PE/VC industry had 180 PE/VC organizations of which 144 surveyed by GVCEPE, which included 258

investment vehicles, 1,593 professionals and 502 portfolio companies. From 2005 to 2009, 414 new

investments and 137 exits (37 IPOs) were made by the PE/VC organizations operating in Brazil.

Figure 6. PE/VC Committed Capital to Brazil as Percentage of the GDP (In %)

Source: Ramalho et al (2011)

4. THE FUNDAMENTALS OF PE/VC FUNDRAISING

The literature about PE/VC fundraising has been based on a supply-demand equilibrium model

imagined by Porteba (1989) and described by Gompers and Lerner (1998). Notwithstanding the clear

importance of the subject, only few works have examined the variables that drive PE/VC fundraising

31

Gompers and Lerner (1998) investigate the supply and demand forces that drive venture capitalfundraising in the U.S. They use macroeconomic variables from 1969 to 1994 to verify which variables

are related to investors’ new commitments in that country. Most of the literature that emerged from

Gompers and Lerner (1998) focus their attention on cross-country analysis and expand the variables

under investigation (Jeng and Wells, 2000; Balboa and Martí, 2003; Schertler, 2003; Mayer et al,

2004; Romain and Van Pottelsberghe, 2004; Félix et al., 2007; Bonini and Alkan, 2012).

Figure 7. Supply and Demand in PE/VC

This graph represents the supply and demand dynamics of PE/VC. Equilibrium before the clarification of ERISA is represented by Q1. After ERISA, the supply curve shifts from S1 down to S2 (A) and the new equilibrium quantity of PE/VC is Q2. Capital gains tax reduction move both demand to D2 (B) and supply to S3 (C) and the equilibrium quantity of PE/VC moves to Q3.

Source: Gompers and Lerner (1998)

The supply of PE/VC is characterized by the amount of capital committed by the investors to this

activity, while the demand corresponds to entrepreneurs’ capital needs to finance their companies

(Gompers and Lerner, 1998). Accordingly to Lopes and Furtado (2006), the PE/VC asset class leads

toward a more complete market since traditional assets (e.g. stock market) do not offer the same risk

and return characteristics of a PE/VC investment. In fact, the low correlation between PE/VC and

other assets allows diversified investors to optimize their portfolios (Chen et al., 2002; Lopes e

32

Figure 8. Efficient FrontierThis graph compares the efficient frontier with and without the introduction of the PE/VC asset in a diversified investment portfolio. (*) refers to Treasury Bonds’ returns (LTN, NTN-D, NBC-E, LTF, NTNC, NTN-B).

Source: Lopes and Furtado (2006)

A review of the existent literature is important to understand the PE/VC industry dynamics and to

identify which variables best fit in an equilibrium model for the Brazilian market.

A) Economic Activity

Gompers and Lerner (1998) hypothesize that GDP growth in real term positively affect the demand for

PE/VC. In an economic growth scenario, more entrepreneurial opportunities would be available and

more startups would be created thus increasing the financing needs. As noted by Jeng and Wells

(2000), a more favorable macroeconomic environment for investors should positively affect the supply

of PE/VC. Gompers and Lerner (1998) find significant statistical evidence that GDP growth in real term

is positively related to fundraising. Balboa and Martí (2003), as well as Romain and Van Pottelsberghe

(2004), also find that GDP growth has a significant impact on PE/VC fundraising. However, Jeng and

Wells (2000), Félix et al. (2007), and Bonini and Alkan (2009) do not find it to be statistically

significant.

A.1.) Entrepreneurial Level

Romain and Van Pottelsberghe (2004) introduce the analysis of the entrepreneurship level measured

by the Total Entrepreneurial Activity Index (TEA) from Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM). The

authors analyze several countries and find that entrepreneurship is positively related to new PE/VC

33

fundraising. Nonetheless, Félix et al. (2007) do not find the entrepreneurship activity to be statisticallysignificant.

B) Stock Market Development

Many authors describe the importance of an active stock market for thriving PE/VC industry. A vibrant

stock market offers exit through IPOs thus increasing the probability of higher returns (Barry et al.,

1990; Bygrave and Timmons, 1992; Lerner, 1994; Gompers and Lerner, 1998; Black and Gilson,

1998; Black and Gilson, 1999). Martin et al. (2002) argue that the superior development of the U.S.

PE/VC industry is consequence of a more active stock market. Fox (1996) notes that vigorous equities

markets have preceded the development of healthy PE/VC industries. According to Franzke (2003)

the expansion of Germany’s PE/VC industry in late 1990s was only possible due to the creation of

Neur Markt in 1997, which provided an exit alternative to the PE/VC investments.

Schertler (2003) uses market capitalization and number of listed companies as proxies for the liquidity

of stock market and finds that it has a positive impact on PE/VC activity. Félix et al. (2007) also find a

positive effect in their study, while Jeng and Wells (2000) and Balboa and Martí (2003) find no

statistically significant evidence that market capitalization growth has an impact on PE/VC fundraising.

C) Return on Investments

Lerner (1994) shows that PE/VC organizations obtain a significant part of their returns from their

invested companies that go public. Gompers and Lerner (1998) hypothesize that realized returns

should have a positive effect on the level of PE/VC fundraising. High profits from past investments are

expected to increase investors’ willingness to provide more capital to PE/VC organizations, thus

impacting the supply side. Moreover, successful exit cases should contribute to increase the number

of entrepreneurs looking for PE/VC investments as a financing alternative, hence increasing the

demand. Gompers and Lerner (1998) note that ideally we should have performance data for each

investment vehicle in order to analyze their returns. Nevertheless, public equities performance and

IPO information can be used as proxies for returns since the stock market is considered the main exit

strategy of PE/VC organizations.

34

Gompers and Lerner (1998) examine PE/VC-backed IPOs’ market value and stock market returns intheir work. The authors find no statistical evidence of an effect of these two variables for their

industrywide results. However, an investigation by individual PE/VC organizations suggests that

PE/VC-backed IPOs’ market value in the current year and in the previous year have a positive

relationship with fundraising. They also find evidence of a positive effect of stock market returns in the

individual level analysis.

Balboa and Martí (2003) use only IPOs but also trade sales as proxy for positive returns and write-offs

and buy-backs for poor performance. They find a positive and statistically significant coefficient for

IPOs and trade sales in previous year, but no effect from write-offs and buybacks. The authors also

test for stock market returns in the current year, though they do not identify any effect. Félix et al.

(2007) also use IPO, trade sale and write-off information to address the returns impact on PE/VC

activity. In line with Balboa and Martí (2003), IPO and trade sales are significant and positive related to

PE/VC fundraising. Jeng and Wells (2000) also find that high levels of IPOs in the current year and in

the previous year are positively related to new PE/VC commitments.

D) Interest Rate

Gompers and Lerner (1998) suggest that high interest rates would lead investors to put their money in

bonds rather than in PE/VC. The results by individual PE/VC organizations show that previous year

short term interest rate (1 year) is an important determinant of the amount of PE/VC raised.

Nevertheless, it does not impact industrywide fundraising.

Balboa and Martí (2003) argue that long term interest rates should be used since the average life of a

PE/VC vehicle is 10 years. Excluding U.K. they are able to find an expected negative coefficient

although not statistically significant. Romain and Van Pottelsberghe (2004) show that short and long

term interest rates have a positive impact on fundraising, although they report a negative effect from

interest rates spread (i.e. the difference between 1-year and 10-years interest rates). Félix et al.

(2007) use long term real interest rates in current year; however the results are not consistent through

35

E) TaxationIn his seminal work, Porteba (1989) hypothesizes that higher capital gains taxes affect demand and

supply of PE/VC. He suggests that lower capital gains taxation increases entrepreneurs’ willingness to

startup a company (or workers to become entrepreneurs), thus positively affects the demand for

capital. Moreover, he argues that lower taxes should increase investors’ returns and, consequently,

the supply of capital to the PE/VC activity. However, the author concludes that his argument regarding

the supply side is weak since the largest share of PE/VC commitments comes from non-taxable

investors (e.g. pension funds). Empirical works from Gompers and Lerner (1998) and Jeng and Wells

(2000) find no evidence of capital gains taxation impact on PE/VC fundraising.

F) Regulation

Some anecdotal evidence appears to supports the claim that ERISA regulation has played a decisive

role in the growth of the PE/VC industry in the U.S. After the Prudent Man rule clarification brought by

ERISA, pension funds’ commitments to PE/VC skyrocketed. Gompers and Lerner (1998) empirically

investigate whether ERISA has a positive effect on the supply of PE/VC to the market. The authors

find evidence that it is positively related to PE/VC fundraising in the U.S. Further, they suggest that the

probability of raising a PE/VC vehicle increased after ERISA.

G) Innovation

Gompers and Lerner (1998) show that fundraising is positively related with previous year’s academic

and industrial R&D expenditures per capita, with effect through the demand for capital. Kortum and

Lerner (2000) show that PE/VC-backed companies are involved in important innovations in the U.S.

economy. Romain and Van Pottelsberghe (2004) report the positive impact of R&D expenditures

growth rate, industry’s R&D capital stock and number of patents. Bonini and Alkan (2012) also find a

positive relationship between R&D on PE/VC fundraising. Nonetheless, Félix et al (2007) do not find

any evidence from R&D expenditures growth rate in the current year.

H) Reputation

In their analysis of the fundraising patterns by individual PE/VC organizations, Gompers and Lerner

36

amount of money it raised in the last ten years and number of years since raising last investmentvehicle. As expected, the authors find statistical evidence that older and larger PE/VC organizations

have a higher probability of fundraising.

I) Other Factors that Affect PE/VC Fundraising

The cross-country studies present additional variables that are investigated. Jeng and Wells (2000)

include accounting standards, corporate governance, labor market rigidity level, and legal origin as

independent variables in their models. Romain and Van Pottelsberghe (2004) also analyze labor

market rigidity, while Bonini and Alkan (2012) consider legal origin in addition to inflation rate and

political risk. Balboa and Martí (2003) include gross domestic savings in their analysis, and Félix et al.

(2007) consider price/book value and unemployment rates.

5. MODEL

The economic agents have their own expected rate of returns for the PE/VC utilized, which is

represented by the price in equations 1 and 2. Hence, the actual amount of PE/VC fundraised

represents the market equilibrium between the entrepreneurs’ demand (PD

PE/VC) and the investors’

supply (PSPE/VC) of capital as described by Gompers and Lerner (1998).

PDPE/VC = ω0 + ω1 PEVC + ω2 EA + ω3 ER + ω4 R + ω5 TAX + ω6 R&D (1)

PS

PE/VC = δ0 + δ1 PEVC + δ2 EA + δ3 ER + δ4 R + δ5 TAX + δ6 R&D + δ7 REG (2)

In the equilibrium, we have PD

PE/VC = PSPE/VC and, therefore, the level of PE/VC is given by:

(ω1 –δ1)PEVC = (δ0 –ω0) + (δ2 –ω2)EA + (δ3 –ω3)ER + (δ4 –ω4)R + (δ5 –ω5)TAX +

+ (δ6 –ω6)R&D + δ7 REG (3)

PEVC = ⌊

(δ – ω )(ω – δ )⌋ + ⌊

(δ – ω )(ω – δ )⌋ EA + ⌊

(δ – ω )(ω – δ )⌋ ER + ⌊

(δ – ω )(ω – δ )⌋ R + ⌊

(δ – ω )(ω – δ )⌋ TAX +

+ ⌊

(δ – ω )(ω – δ )⌋ R&D +

ω – δδREG

37

PEVCt = ɸ0 + ɸ1 EAt-1 + ɸ2 ERt-1 + ɸ3 Rt-1 + ɸ4 TAXt-1+ ɸ5 R&Dt-1+ ɸ6 REGt-1 (5)Where,

PEVC = Fundraising level

EA = Economic activity

ER = Expected returns

R = Interest rates

TAX = Taxation level

R&D = Innovation level

REG = Regulation

Equation 5 can be expanded into:

PEVCt= ɸ0 + (ɸ1.1 GDPt-1+ ɸ1.2 TEAt-1) + (ɸ2.1 IPOt-1+ ɸ2.2 MAt-1 + ɸ2.3 IBOVt-1) + ɸ3 Rt-1 +

+ ɸ4 TAXt-1+ ɸ5 R&Dt-1+ ɸ6 REGt-1 (6)

Where,

GDP = Gross Domestic Product

TEA = Entrepreneurial activity

IPO = Initial Public Offerings activity

MA = Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) activity

IBOV = Stock market returns

Dependent Variable:

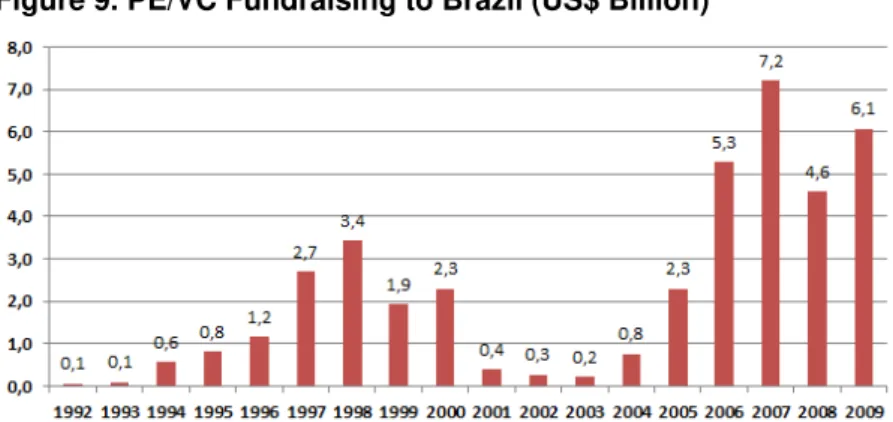

a) Industrywide - source: GVCEPE, Venture Equity Latin America and Asset Alternatives: new

PE/VC commitments (i.e. fundraising) to Brazil from 1992 to 2009, with the values are expressed

in US$ billions at level.

b) Individual Level - source: GVCEPE: investment vehicles sizes (i.e. new PE/VC commitments) as

38

Independent Variables – Economic Activity (EA):a) GDP – source: Brazilian Central Bank: annual real growth (in %) from 1991 to 2009. Both industry

and individual levels models consider GDPt and GDPt-1. Expected sign: positive.

b) TEA – source: Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Brazil: the Total Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA)

ratio (in %) is available to Brazil since 2001. The individual level models consider TEAt. Expected

sign: positive.

Independent Variables – Expected Returns (ER):

a) IPO – source: CVM: natural logarithm of the number of new public offerings (primary and

secondary) from 1991 to 2009. Industry and individual level models consider IPOt and IPOt-1.

Expected sign: positive.

b) M&A – source: KPMG: natural logarithm of the number of mergers & acquisitions (M&As) from

1991 to 2009 in Brazil. Industry and individual level models consider MAt and MAt-1. Expected

sign: positive.

c) Stock Market Returns – source: Economática: annual real returns of the Ibovespa (in %) from

1991 to 2009. Industry and individual level models consider IBOVt and IBOVt-1. Expected sign:

positive.

Independent Variables - Regulation:

c) FIP – source: CVM: dummy variable equal to 1 for FIP CVM regulation and 0 otherwise. CVM

rule 391 created the FIP (Fundo de Investimentos em Participações) in 2003 which formalized

the creation of an investment vehicle that allowed pension funds to invest in PE/VC in Brazil.

Considered in the industry and individual level models. Expected sign: positive.

d) FMIEE – source: CVM: dummy variable equal to 1 for FMIEE CVM regulation, and 0 otherwise.

CVM rule 209 created the FMIEE (Fundo Mutuo de Investimentos em Empresas Emergentes) in

1994 which formalized the creation of an investment vehicle that allowed seed and VC

investments in Brazil. Considered in the industry and individual level models. Expected sign:

positive.

Independent Variables – Others:

a) Interest Rate (R) – source: Brazilian Central Bank: annual real rate (in %) of the CDI from 1991 to