"

Brief Historical Ecology of Northern Portuga l during

the Holocene

BRUNO PINTO'"

Departm ent of Sciences alld Environmental Ellgin eering New University of Lisbon

2829-516 Ca"arica. Pnrltlgal £-mail: Bpinto 74@glllllil.com

CARLOS AGUIAR

Superior Schoo/ of AgriculTUre . Dcparrmclll oj Biology 5301-855 Bragcmra, Porrllgal

MAR IA PARTIDA.RIO

Techllic(/I Superior II/ still/Ie

Av. Rovisco Pais. 1049-00 1 Lisbon. Ponllgal

*

Correspondi ng <luthorABSTRACT

T hi s study rev iews the main changes of th e vegetation and fauna in northern Po rtuga l d urin g the Holoce ne, Ll sing literatu re from pa laeoeco logy, archaeol-ogy , hi story, writings fmm trave lle rs and naturali sts, maps of ag ricu lture and

fo restry and CXpCl1 consultati on. The ecolog ica l hi story of thi s area shows a tre nd of forestry decli ne, with periods of recovery of the vegetati on related 10 the decrease of human pressure on natural resources. The deforestation bega n on

4

BR UNO PINTO, CA RLOS AGU IAR AND MARIA PARTIDARIO

INTROD UCTION

Med ite rra nean ecosyste ms have a long hi sto ry of both human and oalura l impacts wh ic h had profound consequences for contemporary biodive rsity.l The use of fire bx,hum ans, w hic h dates back to th e Middle Ple istoce ne, probably c han ged the natural fire reg imes and the vegetati on eve n before the Ho loce ne.2 Despite the diffi cu lty of disti ngu ishin g between natu ral and human·induced c hanges in th e de ve lopme nt of Mediterranean ecosystems , it is consensua l that human action inc reased drastically with the int rod uct io n of the agro-pasto ral way of life in the Neolithic.)

The classica l viewofthe role of human ac tion in the shap ingof Meditcrranean

landscapes is the so-ca lled ' Ruined Landscape ' or ' Lost Eden' theory, which

argues that humans were respon sible for the degradation and desertification of this reg ion :' More recently, this theory has bee n contested by Grove and Rack-ha m (200 I ), w ho sla ted tRack-hat landscape cRack-hanges were primarily a conseq uence of climatic c han ge. re info rced by human impac t. Other authors offe r an inter-mediate pos ition, arg uing, fo r example. then excess ive precipitation events are unlikely lO ca use significant soil eros io n witho ut prior direct o r indirect human impact on the vegetat io n.'

A lthough there is a general idea about the hi story of changes in the Med iter-ranean basin. we still lack detailed informatio n about the process of transform a-tion and th e implicaa-tions this can have in the future management of thi s region. Moreover, this information is ofte n scattered through differe nt sc ientific fields s uc h as palaeoeco logy, arc haeo logy, history a nd e thnography. We co nsider tha t the lon g and com plex hi story of interact io n bet ween Med iterranea n ecosystems and humans cou ld ben efit from the int eg ratio n of natural a nd soc ial sc iences, and that the combi nation of these differe nt sources of information can poten-tially provide more appropriate explanatio ns for the e nviron me ntal hi story of the region.(j

HISTOR ICAL ECO LOGY OF NO RTHERN PORTUGA L

.

..

~....

".

.

~"

....

...

-

,,-, ":, ?

... -'0 ~"O"IU

-'.

,

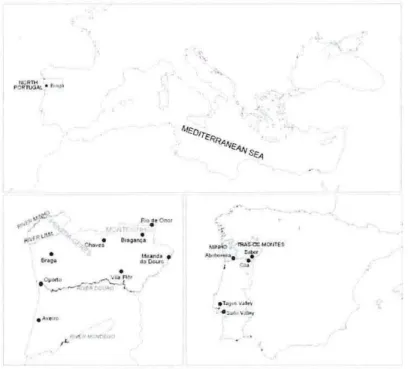

~-.-FIGUR E I . The Medite rranean Basin. Iberian Peninsula . and ce ntral and northe rn Portugal. showing the Joc'HioHs d isc li ssed. Pal ynologi ca l studies in : (a) van der Kn aap and van Lee uwen. 1995, \997; (b) Allen ct al.. 1996: (e) Rlli z-Zapata CI al.. \995; (d) Muiioz-Sabrina et al.. 2004; (e) Muiioz-Sobrino ct al.. 2005:

(0

Munoz.-Sabrina ct a1..1996:(g) Ramil -Rego et <11. ,1998 ; Marcus . 1992 .

l egend

-Oouro river

_ Forestry area

Agricultural area

rr.a

Shrublalld Areas Yli th 1'10 information6

BRUNO PINTO. CARLOS AGUIAR AND MARIA PART ID ARIO

METHODS

In this st udy. northern Portuga l was de fined as the region limited by the Douro Ri ve r in the so uth , the Spanish border in the north and ea st and the Atlantic Ocean to th e west, covering an area of approximately 18 ,000 kl11 ~ . The western half of northe rn Portugal is characterised by granite or sc hi st e ro sion platforms. with wide E- Wor ENE- WSW vall ey s ti ll ed w ith flu vial and colluvial deposits.' Steeper landfo rm s appear towards the east and c ulminate in the g ranites of the

Galaico~Porlllgllese Mountains (1545 m ma x. aiL).

Physiograph y exe rts a strong influence all macroclimate, vege tation and present land lI ses in northern Portugal. The balTicreffect of the Galako-Portuguese Mountain s causes a drop in precipitation fro m more than 3000 mm/year to le ss than 400 mm/year in a 100 km tran sect. Conse quently , alon g th ese mountains there is an unu sually sharp boundary between the Eurosiberian and the Mediter-ranean Phytogeographic Region s!! and be tween temperate and MediterMediter-ranean mac ro-bioc limate and ag ric ultural systems.

A te mpe rate macrobioclinmte dominates in the NW.'1 w ith a sub- medite r-ranean inOuence. revealed by a sig nifi cant s umme r drou g ht (> I month). The lowland tree layer is com posed of Quercus mbur and Quercus Silber and above 800-900111 altitude. natural fore sts are dominated by Quercus mimI' and Que/'-ClfS pyrellaica. The main actual land cover types are agriculture. plantations of PiJ/us pillaster and Ellcalyp1lls J;/Obll/IIS. lall shrublands of CylislIs slri(/{ /l s and Adenocarplls laill;.ii and mi xed low shrub lands of Ulex sp. and Erica sp.

In the mou llt a ins , chestnut o rc hards are fundamental to loca l economies. particularly in Mediterranean territories . In te mperate mountain s . semi-natura l pastures and low s hrubl ands are grazed by s mall reg ional calli e breeds. In the Mediterranean mountains and plateaus. heathlands are managed with tire to provide food fo r reg io nal breeds of sheep and goat. The Med iterranean vegeta-tion is composed of Qllercus pyrel/oica and, on Sleep sunny slopes, Quercus mllllldifolia.

Mediter-HISTORICAL ECOLOGY OF NORTHERN PORTUGAL

In relation to the population, northern Portugal follows the national trend , with a concentration in the coastal regions. Population density in the northeast is generally low (below 50 inhabitants per km ~) and is decreasing, and most of the working population is employed in agro-pastoral activities. In the northwest. the population density is higher and increasing, and most peopl e in the region are employed in industry and services.11

So//rees

(4

illformatio/lThis study reviews the main changes of the vegetation and fauna ill northern Portugal during the Holocene, using literature from palaeoecology, archaeol-ogy, history, writings from travellers and naturalists , maps of agriculture and forestry and expert consultation. The information used is described beJow in more detail. All the dates mentioned in the text were obtained from radiometric dating using 1.IC (radiocarbon ) without calibration or estimated dates, except in the case of the climatic data taken from Desprat et al. (2003) who used 1.IC

dating with calibration , which are referred to as 'ca l'.

The proxy evidence provided by charcoal dat.a collected in Portuguese ar-chaeological sites and NW Iberia palynological surveys are the main source s of information for northern Portugal 's palaeoenvironmental reconstitutions. Pollen record similarities in NW Iberia are higher inside the same actual biogeographical units .12 POl'eastern areas . the most reliable palaeopalynological information comes

from Secundcra Mountain in Spain .I~ However. these were used with caution for Mid and Late Holocene palaeoenvironmental reconstitutions . becau se northern Portugal's continental mountains have a plain morphology and arc much lower than Secundera Mountain. For these reasons, pollen data from Estrcla Mountains (central Portugal) was also used, especially for periods after the Neolithic (See Diagrams I and 2).1,\ Present-day vegetation ecology was also a fundamental component in the interpretation of pollen data. The uniformitarian assumptions it involves are more speculative when pollen data or charcoal deposits are scarce or absent, as is the case in the lowlands of northern Portugal.

Palaeoeco logical literature was also used to assess Holocene climate chang-es in the study area, through the information drawn from Allen et al. (1996).

Ramil-Rego et a!. (1996) and Dcsprat et al. (2003), in which pollen data was used to characterise the climatic changes. The results of these two studies are summarised in Table I.

8

BRUNO PINTO, CARLOS AGUIAR AND MARIA PARTlDARIO

groups. Other studies in archaeology detailing the excavations in a rock-shelter during the Neolithic orthe human occupation during the Roman times were also cOllsuited,l5 History books and papers were used to collect information related

to Portuguese forests such as demographic variations, and human activities such as agriculture, animal husbandry and hunting pressure.

Writings (~f[ravellers, natIlralists alld iIllllfers

Literary sources on northern Portugal which were considered in this review include writings from classical authors and books from the sixteenth to the early twentieth century.16 Some of these books were particularly useful, since they were written by naturalists whilst living in or travelling through the study area. In a few cases where books are written in an apologetic tone to please a patron, the information was discarded if there was no confirmation of its validity through other sources.17 From the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, there are

also several descriptions in the press of hunting trips to the mountain areas of this region, which were used as a source of information.

Historical and present-day sllldies ofagriclIlwre,foreslry,fallna and elhnography

Previous studies about the forest and agriculture in Portugal for specific periods such as between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and from the nineteenth century to the present were used in this review. Other studies about subjects such as ship construction during the Portuguese Expansion were also consulted. IH

In relation to cartographic information , the map from Higounet (J996) in Wil -liams (2000) of the major forest areas in Europe between the fifth and eleventh centuries and the Portuguese map of agriculture and forestry from 1910 were both used for a general assessment of the land uses of northern Portugal in these two different time periods. Previous studies of historical information on the fauna in Portugal, and present-day studies of vegetation, fauna and ethnology were u sed for the more recent past .I') Finally. ethnographical studies co nce rning

HISTORICAL ECOLOGY OF NORTHERN PORTUGAL

RESULTS

Transition/rom the Late Pleistocene to rhe Holocene

The last glacial maximum in the Iberian Peninsula is estimated to have occ urred betwcen20,000 and 18,000 yr BP (nineteenth and eighteenth millennium Be) . At the e nd of til is period, the higher mountains of northern Portugal were permanently,

or at least for most of the year, covered with ice . Perpetual snows persisted at

about 1100-1200 metres and extensive ice sheets acc umulated at lowe r altiwdes in more continental areas,2' The areas under greater maritime innuence were morc humid than continental ones and she ltered more tree communiti es.

C limatic conditions in no rthern Portugal began to improve at abo ut 16,000 yr I3P (fifteenth mille nnium Be ) and triggered a period of deglaciati o n with an approximate duration of 3000 years. Betwee n 13 ,000 and 11,000 yr BP (twelfth and e leventh millennium He), during the Late-glacial Interstadial , there was an accentuated increa se in temperature and precipital ion, which promoted an ex pan-sion of tree taxa and the dec line of steppic vcgc tation.21This trend occurred earlier

and was more prono unced in the more oceani c and humid western mountains and plains because the arboreal lowland vegetatio n was already sig nifh.:anl. Durin g this period, there was a short peak of ex pan sio n of Betllia sp .. before an expansion of Pinus sylvestris, which was followed by an increase of English oak (Quercus robur) . Between 11,000 and 10 ,000 yr BP (tenth millennium ee) (Younger Dryas), there wa s a contraction of the tree line and an increase of the re prese ntation of herbaceou s [md shrub spec ies in the mOlllltain s . with hi ghcr re prese ntation of other species in poll e n assemblages of continental te rritories (see Diag ram I). Prec ipitation decrease played a larger rolc in these vege tation changes than temperature . 23

As previously desc ribed , the physiognomy of northern Portugal is character-ised by deep valley s, whi ch apparently served as refuge areas for the vegetation during cold and dry period s. These areas were al so i rnportant for th e mamm al ian fauna, which probabl y moved along the vall eys, as we ll as mountain lOpS. Th e o ldest palaeolithic en grav in gs ill the valleys of Foz C6a (bonIer area be tween central and northeast Portu gal ) are estimated to be datel' 22 ,000- 20 ,000 yr I3P (twe nt y-first and twe ntie th millennium He), and represent wild goats (Capra sp. and I?//picapra mpiclIpra) . auroch s (Bos prilll igellills) and wild ho rse ( £ qlllls cabal/liS) . Recent findin gs of palaeolithic e ng rav ings along the Rive r Sabor (NW Portugal) represe nt aurochs and wild ho rses?! Th e presence of bo th Capra pyrellaica and C. ibex in Po rtugal is not certain, sin ce the bones of th ese spec ies are very difficult 10 di s tjll g ui s h. ~.'i

10

BRUNO PINTO. CARLOS AGU IAR AN I) MARIA PARTlDARIO

scraIa ).~(l However, it seems I ikc ly that a species of wild goat (Capro pyrenaica) continued to ex ist in the higher mOllntain s of northern PorlUgal throughout the Holocene. since it became extinct ill the Peneda-Gere s mountains in 1890.27 Other herbivore specie s such as wild equids (EqllilS cabal/lis antlfllesi and pos-s ibly EqllllS hydruntilllfS) and fallow deer (Dalila dama ) became extinct before the beginnin g of the Holocenc.2R During the late-glacial interstadial. the

com-position of hunted mammalian archaeofaUll<l became largely dominated by the rcd deer (Cerl'lfS elaplllls), but other species such as wild rabbit (Or.vclo!aglls

,=

r'

12~

,.5OC)'

HISTORICA L ECOLO GY OF NORTHERN PORT UGA L

cllniculus) , auroc hs , roe deer and wild boa r are also fo und in an.: haeo logicaJ s ites. It is interestin g to note that , in the Poz Coa Palaeo lithic e ngravings , red deer also became much more common during the EpipaJaeolithic.2<J

Polle n analys is ill NW Ibe ria does not al low for the di stinction bClwccnllatural

changes in the vegetatio n and human acti vities , which apparently indicate s thar the latter had a s mall influ ence on the vegetation. Ho wever, it is known that the new tool technologies and a more effi cient soc ial o rganisation of the Upper Pal aeolithic human population s enabled an incrc<J scd human influence upon their e nvironment. It is also un clear if hunting contributed to the decline alld/o r extin cti o n of mammal spec ies that preceded the Ho loce ne in north ern Portu ga l. Several authors suggest th at the ex tinc Lio n o f chamo is (Rupicapra rup icapra ) and the declin e of species s U(.: h as wild ho rse and aurochs were a conseque nce of the forest expansion befo re thc Ho locenc.3o On the other hand, it ha s also been suggested th at ex tin cti o ns durin g the Late Pl eistocene we re due to th e co mbi natio n of bo th anthropogenic impacts and climatic changes.:; '

Th e Early Holocel/ e

In the beg innin g o f the Ho loce ne, c1imale warming contributed to the repl ace-mcnt of steppe and shrub vegetation in lh e moun ta in s by forest. Pollen data usuall y show s an initial peak of Pill liS sp. and Belula sp,. foll o wed by a la st-ing expan sion of QlIercus s p . J ~ (sec Diagram 1). Th e defini ti ve do minan ce of forest was a rap id event du c to the plain morphology of the no rthern Port ugal hi ghlands. In the NE valleys , steppe s with d ispersed .Ilf1liperlls sp. anel/or PinIls sp. were replaced by QuerclIs rolulld~/ o lia and QI/ercus suber fores ts. Forced by compe tit ive exclu sion w ith Quercus sp .. Pill us syl v('slris was pushed to hig he r altitudes until it became ex tinc t in the Po rtug uese mountai ns. Althou gh climate warming is the most likely cau se for the dec line of thi s specie s. so il pedoge nes is , the shortening of the recurrcnce period through human-indu ced fire s and the stag nation o f the spread to o ther areas due to increased rainfall are also po ss ible ex pl anation s,JJ

12

BRUNO PINTO. CARLOS AGUIAR AND MARIA PARTIDARIO

The changes in the landscape and fauna in the transit ion to the Holocene probably have lead 10 c hanges in hunte r-gm herer stralcgies. ill which vegetation mnnagement assumed g reater impo rtallce:17 Vegeta tio n management cou ld he achieved using primitive tools and/or fire to create open areas wit h herbaceou s and shrub vegetation , which favoured the presence of steppe birds (e.g . red partridge) and large herbivores such as wild horses and aurochs, and improved the ability to observe w ild animals and so improve hun ti ng s ucce ss:' ~

Seve ra l sources of ev idence suggest that the Mediterral1c ~ U1 J 'I and Central European.Jo biotopes were co mposed of a mosaic of success io nal stages before human d isturbance became s ignifi cant. In a territory w ilh sub-M edi terranean or Mediterranean climate with a strong reli e f such as in northern Portugal , a com plex panoply of di sturbance types - fire , landslides, herbivory. tree di seases, tree decrepitude - converged and promot ed the development of heteroge neous vege tation mosa ics in eco logicall y ho mogeneous areas. These mosa ics certainl y va ri ed from almost co ntinuou s tine-grained fo res ts to heteroge neo Lis vegetation complexes , whe re c limax fore sts coex isted in a shiftin g mo sa ic w ith varioll s types o f herbaceous low shrub and la ll shru b co mmun it ies and secondary forests. Since there is ev idence o f s mall-scal e a nth ropogeni c defo restat io n in Estre la Mountains more than 8.500 years ago. human ac ti o ns also co ntri buted to this d iverse mosa ic or s uccess ional stages . ..! 1

From the Neolithic to the Bron:.e Age

Accord ing to the maritime pio neer colon isation model. the Neolithic in Portugal has its origin in the colon isation by small seafarin g g roups of agr icultural -ists comin g from the Mediterranea n regio n in the s ixth mill enniulll uc. ..!~ The in troduct ion of thi s agro-pastoral way of life co incides with the begin ning of the Climatic Oplimum. when the temperature and humidit y reac hcd a peak:l.\ The Neolithi c g ro ups probably expnndcd from the eoastnl areas o f sou thern Portugal and became rapidly estab li shed in the inte rior region s. thus com peting and overcomi ng the ex isti ng groups of hun te r-gathe rers. The lirst agro-pa sloral co mmu niti es prac ti sed a shiftin g ag ric ulture. In the Buraco da Pal .. l. a rock-sheller ill Mirandela (NE Portuga l) . ev idc ncc o r wheat , barle y and broad bea n we re recovered fro m the fi rst phase or human occ upatio n. Thi s occupatio n had a seaso nal character and was used for domest ic cons umpt ion _ ot:l-urri ng between the end of the sixth and beginnin g of the fifth millennia Be to the e nd or the fourth mill e nnium Be :I-1

HISTORICAL ECOLOGY OF NORTHERN PORTUGAL

several archaeological sites,JI, Moreov er. pa lynological slUd ies of mountain s in north west Iberia also show that sign ifi cant deforesta ti on started around the mid -fo urth mille nniulll Be. In thi s process, human -i nduced fire combined with

animal hu sbandry and, to a lesser extent. primitive tools were lI sed extensive ly.

as has been desc ribed in other Mediterranean rcgions:!1 Therefore, the mega J ilhic c ulture that built impressive sto ne structures throughout northern Portu ga l during the fourth millennium Be was also responsible for the beginning of large -sca le de fores tat ion in thi s area :l ~

In the third millenniulll He (i.e. beginning oflhe Bronze Age), pal yno logica l stu dies show an intensifi ca ti on of defores tati on in northern Portugal.-llJ In the

Estrela Mou ntains. large !ires with pos sibl e human ori g in are recorded aro und

4,300 yr or (third millennium liC) which devastated and c hanged the vegetation in this area. Thi s is followed by the first s ig n o f cereal s in the pollen an.: hi ves·'iI) (sec Diag ram 2).A bout 1000 yea rs hHer, the re was a new and more illlcn sc phase of deforestation in this area, w hich is synchronous with th e strong dec line of trees ill th e mountains of northwest Iberia . recorded be tween 3,500 and 3.000

yr I3P (second millennium H C ).~I In a sim ilar pattern, thi s was also accompanied by the prese nce of cereal s in the pal y nol og ica l records.

Accordin g to the secondary products re vo lution. the continllo ll scx pan sion 10

new agri c ultural areas is relnted to an increase in population a nd the beginning of the use of animal traction and the plough in agriculture .. ~1 A lthough the re is still no direct evidence of this technological change in northern Portugal. there are argulllents w hic h s upport thi s hypothesis. For exa mple. in the third millennium He, the above-mentioned rock-shelter of Burnco d a Pala began to be ll sed for large-sca le storage of cerea ls. w h ich points to an increase in agric ultural produc-tion and human populaproduc-tion. Moreover. there is also direct ev idence of animal hu sba ndry during thi s mill e nnium in a reasonable number of archaeologica l s itcs of no rthern Portugal. The th ird mill e nnium Be is al so c haracterised by the diversifi catio n o f econo m ic activities w hi ch ca n be a co nseque nce o f popula-t;on grow th . s ince artefact s s uc h as netll oom weights and arrowheads fo und in archaeologi ca l sites sugge sts fis hing/weav in g and huntin g in the region . ~~

The sett leme nts in mid-J11ountain areas of irregular terrain du rin g the transition rrom the third (0 the second millennium Be indicates a comp le mentary li se of the

mo untain a nd the va lley a reas.s.1

C limate wa rming Illay have promoted valley transhum31lce in these reg ions. This period of transition is also c haracterised by

seule-....

'

14

BRUNO PINTO. CARLOS AGU IAR

AN DMARIA PARTIDARIO

of eco log ical succe ssion and a stabilisation of the herbaceous vegeta tion.56 A

reccnt study showi ng the increase of biomass burning in Europe s ince the fifth mi llenniulll He corroborates the wide use of human- induced fires throughout th is reg io n during the Neo lith ic . .H The ag ric ul ture practised in these deforested

areas was cha racterised by short period s of cultivation and the use of fire and dome st ic animals to co ntrol vegetation success ion and so il fertili sat ion ,5H with prol o nged periods of abandonment. which e nabl ed a partial restoration of the fore s t o r (in E. Boserup 's terms) a lo ng fallow cycle . with no crop rotation nor use of o rgan ic fC l1i lise rs.

Charco da Candieira (Serra da Eslrela , 1400 m a.s.L)

~a n c1er Kn aao & van Leeuwen (1995) ~ uplar.: ! rrl*.l

;soo

= ,

"'"

'""j

'>"" I

5000 '1

'~ ' r

WOO

6!;OO 1

"""I

::1

"""

'''''

.

"""

' 0000 •

E

C

;\1

"1

B

HISTORlCAL ECOLOGY OF NORTHERN PORTUGAL

This incipient agriculture began in northern Portugal in the central plains of Tras-os-Montes, Minho and Douro (mostly above 700 metres a.s.I.). extending later to the valleys, where the forests were more resilient and had more bio-mass.-',} The spatial enlargement of these agricultural practices and the probable shortening of the rotation periods promoted significant changes in the landscape. Several authors argue that extensive open areas were normal features ill north-ern Portugal as early as the Bronze Age , at least on hill tops and plateaus, and existed side-by-side with wooded areas, which were mostly located in valleys.w The relative abundance of forests in the valleys of northeast Portugal as late as the 1920s seems to indicate that winter pastures were never a limiting factor for regional animal husbandry. These arguments are reinforced by the fact that written accounts by Roman authors when arriving in the Portuguese territory describe the landscape as deforested in mountain areas.(,1 On the other hand, prehistoric settlements in northern Portugal are more frequent at higher altitudes. which seems to reflect a more intense human occupation of the mountains.(,2 Nevertheless, there are temporary settlemeIHs in areas of low altitude at the end of the Bronze Age in the Minho region (NW Portugal), which were abandoned during the Iron Age, where intensive agriculture was practiscd.6~ _

In relation to the fauna. several archaeological sites in the eoa area (border of central and northern Portugal) from the Neolithic and Bronze Ages showed that , besides domestic animals such as {wines and caprines , there was also consump-tion of wild animals such as wild boar and red deer. (~ ! Aurochs became extinct in Portugal in the Neolithic and the wild horse in the Cha1colithic or Bronze Age. In the case of the domestic horse, some authors argue that it was introduced to Portugal between the Late Chalcolithic and the Bronze Age, whereas others suggest that humans domesticated wild horses in the Iberian Peninsula during this period.(,5 Deforestation probably also had a detrimental effect on species which are more dependent on forest-type habitats such as roe deer and brown bear (UrslIs w·ctos ) and may have benefited other species which prefer more open habitats.

16

BRUNO PINTO. CARLOS AGUIAR AND MARIA PARTIDARIO

Fr011llJze Iron Age 10 the Middle Ages

The proto-Hi story of northern Portuga l is c haracteri sed by success ive inva-s ion inva-s of Indo-European population inva-s which came to the re g io n inva-since the inva-second

millennium He. Although there is little information about th e influcIH.:C of these

people, it is known that so me of these immi g rations had a s ignifi cant impact

011 the vegetation of the region, such as the arrival of the Celts in the first half of the first mill enni um RC. (~ However, t:ol1 siclering that there was a co ld period between 975 a nd 250 ci.l l Be. the decline in the arboreal vegetation in north wes t Iberia during th is pe riod cannOI be attributed exclusively to c limati c cha nges or to the ac tivities of these Indo-European peo ple .('<)

At the end of the Bronze Age (i.c. tran s iti o n to the fi rst mille nnium BC) . there is a systematic abandon ment of open se ttl e ments in northern Portuga l and an exclusi vc use of fortified sett iemcnls.711 De sp ite their heterogene ity, It is thought

that most of the Iron Age people in thi s reg ion depended on cattle rai sing. which was complemented by itinerant or semi-permanent agriculture nnd hunting and gat hering. Co ns ide rin g that cattle rai s ing implies ex tensive g razing lands, thi s certainly cOl1lributed to an in crease in de forestation. The c lassica l author Strabo describes these people as savages li vi ng in lands of poor soil s. fc eding essen-tially on cattle meat and oak acorns. The numero us stone statu es of pig s and bulls in the northeast of Portugal datin g from the pre-Roman and beginning of the Roman peri od, which served as stone marks inlhe landscape, re inforces the importance of cattl e rai s in g and grazing land s in this area.7 1

The hig h numbe r o f fortified sc ttlements fo und in northeast Portuga l (more tha n 500) is ind icati \Ie of significam dcmographic prcssure o n natural resources during thi s period. S ince there was a judicious spatial di stribution of the ir set-tlcments, defensive struct urcs with fortifkation s and the descriptions of pillage acti vitics make it see m Ii kel y that there was inte nse competition ove r reso urccs.72

Demographic pre ss ure was increased by the lise of iron tool s and probably resulted in more efticicnl soil erosion and the destruction of fore sts, cspecia.Jly around sett lements. Th ere was also an intense exploitation of a wide ran ge of vegetation from Ihe Latc Bronze Age 10 the Ro man period. used as fu c \' build-ing material and food . Accordbuild-ing to desc ription s of several c lass ical authors. the mountain s of northern Portugal we re al ready deforested by the time of the Roman i IlV01sion.7J

The conques t of the Portuguese territory by the Roman s between the sec-ond and the first ce ntury BC brought drastic changes to agriculture. The Roman pax. integrati o n wirh a greater economic space . technical developments and demographi c growth we re factors whic h contributed to a ge neral inc rease in

HISTORICAL ECOLOGY OF NORTHERN PORTUGAL

are as. Othe r factors such as the introduction o f cultures like hard wheat and rye, the adopti o n o f the system of po!yculture. the use of agri cultural rotation s and orga nic fertili sers also had a major impact 011 land use. Co nsid erin g that the traditional di et of th e Romans consi sted of cereals, win e . oli ves and, to a lesser exte nt , dry legumes and meat. Roman dominati o n al so impli ed a change to a more ccreal -based diet. whi ch was maintained in th e Po rtu guese territory durin g sub sequent ce nturies ?~

A [thoug h til e irreg ula r terrain and ethnic di vers ity o f northe rn Portugal contrib-uted to a res istance to the beginning orlhe Roman dominati o n. their imp lantation during morc than five centuries had an impac t on the human popu lation in thi s reg ion . In re lat ion to the distr ibution of the popu lation. an archaeolog ical study in northeast Portuga l s ho wed that , from 246 prnto·hi storic settle ment s. o nl y 75

present ed signs of roma ni sation and 15 1 new settlements we re created dur in g the Ro man occ upmio n .7h The rea so ns for these c hanges are re lated to the fac t that Roman s e ncouraged or forced loca l peop le to descend from the fortified settl eme nt s in mo untain s and to create ne w villages in access ible areas s uch as plain s . whi ch had more socio -economi c oppurtuniti cs.77 In conclu s ion . Roman

do minati o n had a major impact on the fore sts of the Po rtug uese territo ry. Major deve lo pment s in ag ri culture promoted defores tati o n that was ext ended to the va ll ey s.7!! In thi s res pect . it is interesting to note that romuni sati o n and the fall of the Empire mat ch peaks of decline and expansi o n. res pec li ve ly. of arborea l vegetati o n in seve ral palynological studies in NW Iberia ?1

After the po litit:al in stability of the third and fo urth ce nturi es . the di sagg re-gati o n u rt he Ro man Empire in the Portu guese terri to ry in the beg innin g of tile fi fth ce ntury o pe ned the way for Germanic do min ati o n bctwet: n the fifrh and e ig hth ce nturi es. whi ch brou ght pillage and general instabili ty and mo tivated the reocc upat ion o f the mo untains and other less access ible places. These e ve nt s contri buted to the g radual deg radation of the adm ini strati ve o rga ni sation a nd ag rarian ex pio il:.lt io ll systems o f Roman ti mes. The abando nment of many rural areas d uring thi s pe riod res ulted in ad rastic red ucti o n in agric ultural production nncl nnimal hu s bandry. whic h is probabl y a lso re lated to the Dark Ages Cold Pe riod (450- 950 ca l AD) . Thi s re sulted in success ive fami nes and e pid emics . whi ch took a to ll o n the human populat io ns . Pal yno log ica l in for mati on from Estre hl Mo untain s (Ce ntral Portugal ) show s an ex pans io n of Hew/a alba. whi ch indi cates a recove ry o f the fore st in this area ~ 1I (sec Di agram 2) . During the short pe ri ods o r po liti cal stability. the economy of the region wa s probab ly based on animal hu sbandry. which wa s more important to the Germanic peop les than to Ro man s. nssoc int cd with a se mi -sedentary or shiftin g ag ric ulture.!! 1

se-18

BR UNO PINTO, CA RLO S AGUIAR

ANDMARIA PARTIDARIO

in vaded the area did no t have the condit ions to mu ilHa in the ir domination for long period s of li me . The genen]1 insecurity of the populations. especiall y at the beginning and end of thi s hi stor ica l period. promoted shi fting agricuh urc , animal hu sbandry and hunting and gathering. Th is probably res ulted in further fores t recovery, whic h is indicated by the maintenance of Benda alba in the palynological diagram of Estrela MOli llt ain sH2 (see Diag ram 2).

According to Higoune t ( J966) in William s (2000). th e main fo rest areas

ill the Portu guese territory betwee n the fifth and the e leventh centuri es were )oeared between the Tagus and Guadianf.l ri vers (south of Portu gal). whereas (he north o f th is reg io n had a smaller fo rest area. The ex planation for thi s may be th at there were was greater demographic pressure in northern Portugal before the Roman invas ion s. The definitive Christia n Reconquest of thi s region by the Asturian kin gdom in the eleventh century brought a relati ve po lit ica l stability to this area, and migration and reco lon isation , which res ult ed in pop ulation increase and the foundation of new sett lements .x., During the e leve nth century.

the pro mot ion of agric ulture whi ch is att es tcd by severa l docume nts resulted

in the decli ne of the forests. In the palynoiog iccli study o f Estre la Mountains (ce nt ral Portu gal). there is a gradu al decl ine of Quercus sp. a nd Benda alba in the Middle Ages . which is coincident with an increase in shrubland (Ericaceae sp.) and agricultural areas (Ce realia sp.) ~~ (see Diagram 2). Thi s information is coincident with the assu mption that th e growth of the agro-pa storal activities implied the deforestation of Portu ga l during the Middle Ages.

In

relation to the fauna between the Iro n Age and the Asturian invasio ns. an archaeologi ca l stud y about the Iron Age in the Aboborei ra Mountain s (NWPortugal) revea led the exi ste nce o f bones o f cervids and wi ld pig, whereas severa l hi storical pa inti ngs in th e northeast of P0I1ugai represe nt the hunting of red deer. lI~

HISTORI CAL ECOLOGY OF NORTHERN PORTUGAL

ex ampl e , seve ral villages of the Pcncda-Geres Mountain s (NW Portu gal ) had a n ob li gation to de li ver large amounts of acorns and chest nuts and to ra ise pigs to offerto the king. which indic ates that there were sti II s ignifi cant areas of oak and chestnut trees in these mountains :'! ~

Population growth and political stabilisation in northern Portu gal afte r the

C hri stian Reconques t. enhan ced by the Medi eva l Warm Period in the tw elfth and thirt eenth cent uri es. resulted in a drasti c increase in the rate of deforestation. Hi storical docume nts show frequent disputes ovcr agricultural lands, which contributed to the occupat ion of marginal areas and increased so il e rosion. Thi s hypothes is is rei nforced by the [act that there is a hi gh inc rease in sedi-ment release to the Po rtu guese coast in the twelfth ce ntury in the Aveiro reg ion (Ce ntral Portugal ). ~" One of the factors whi ch contributed to defores tation aro und citi es and villages is that wood continued to be widely used by the in creas ing popu lati o n as fuel, fe nili scr and in the con stru ction of houses and object s . In the twe lfth century, there are reco rds o f wood export ati o n from northern Portu gal to o ther European coull tries, whic h ceased in the thirteenth century. Mo reover, thi s period is c harac terised by the growth in ex te rnal maritime commerce and s hipbuildingalld the beg inning ofwood imports from S pain. France and Eng land to the OPOI"to and Gaia ports (NW Portugal) . Th e tran s ition frOI11 expoller to impo rter of wood is probab ly re lated to the prog ress ive scarcity o f th e forests in the reg ion. which is reinforced by the fact thal their cOllllllunity use s in ce th e tenth century was replaced in the thirtee nth century by divi sions o f forests be twee n ne ig hbours and restri ct ions o ver c utting trees. Neve rthe less. there were still ex te nsive forests in nort hern Po rtugal durin g thi s period. espec ia ll y in the mountain s and mo naste ry enclosu res o f the rcgio ll ."u

In re lat ion to hunting be tween the ele ven th and thirteenth centuri es . spec ies sLl ch as wi ld boar. wild rabb it. red deer. roc decr. b ro wn bear (U r slIs (lfetus) and wolf (Ca nis IlIpIIS ) arc co mmonly referred to in documents of th e th irtee nth ce ntury. Hunting was es pec ially frequ e nt in the mountain region s of northern Portu ga l. to sati sfy th e need s of th e loca l pop ul ati o ns but al so to fulfil th e ri gill s that were due to the k in g. Wild rabbit was an impo rtant species . becau se its fur sustained the nat io nal pe lt indu stry, and wasonco[ the mo st exported Po rtug uese produc ts. In the 'Law o f the Price-Fixe r ' o f 125 3 , the prices of severa l spec ies of wild animal s and bird s and seveml restri cri ons for the ir capture are referred to . wh ich suggests that th ey had s ignin c<lnt eco no mic importance.""

In;) process s imil ar to other European COUll tri es. population g rowth recorded

20

BRUNO P1NTO, CARLOS AGU1AR AND MARlA PARTIDAR10

of Black Plague. In the particular case of northern Portugal , in the inquiries of 1290 and 1321 the northeast is considered well populated , but has a reduced population in the census of 1422. This idea of population scarcity is reinforced by complaints by the delegates of the king in 1439 about the low population of Tras-os-Montes region (NE Portugal). requests for the installation of shelters for outlaws and the privilege of reduced taxesY-~

The general reduction in population led to the abandonment of agricultural fields during these two centuries and the decrease in forest clearances. Follow-ing a similar pattern to previous historical periods , the decrease in agriculture promoted once more an expansion in animal husbandry, which may have con-tributed to the increase of human -induced fires. Indeed, several authors suggest that these fires were very common in the fifteenth century , with the purpose of pasture renovation, coal production and even to capture wild rabbitsY"

The wood scarcity in the larger settlements in the Ilfteenth century is evidenced by the complaints of the constant cutting of trees in the monastic enclosures in the Oporto region and the implementation of laws to maintain the remain-ing forest and to promote regulation of the exploitation, such as forbiddremain-ing wood extraction, the prevention of human-induced Ilrcs, the creation of forest guards and the obligation to plant trees. During the mid-fifteenth century, the Portuguese Expansion continued to promote boat construction and thi s led to an increase in wood imports from other European countriesY5 In the second half of this century, there was a recovery in the population density and an inherent increase in agricultural production: therefore this period is characterised by a new episode of intense deforestation, with the purpose of expanding areas destined for agriculture. Thi s growth of agriculture also contributed to conflicts over space with animal husbandry, which tended to become once again more restricted over timeY/}

HI STORICA L ECOLOGY OF NORTHER N PORTUGAL

!oponymic studi es. T he s pec ies was limited to the centra l west and north west part of Portugal, and was already rare in the thirteenth century. Sin ce the last kno wn reference to thi s spec ies is in an offi c ial doc ument of 1446. it is lik ely th at it bec ame ex tinct in Portugal in the fiftee nth o r s ixtee nth ce nlUries.'m There are al so references to a small equid called 'zebra ' (probabl y Eql/flS hy drunfinIlS

Or EqlflfS helllimllfs) in the ' Law of the Price-Fi xe r ' , o fficial doc uments and toponymi c: of both Po rtu gal and Spain in the thirteenth and fo urtee llth ce nturies . whi ch may have beco me extinct in the Iberian Pe nin sula aro und the fifteenth and s ixtee nth ce nturies, but thi s scarce evidence is not eno ug h to co nfirm its fo rmer prese nce Y9

The brown bear (Ur sl/s arclOs ) is mentio ned in the ' Law of the Pri ce- Fi xer ' and other documeJ1ls o f the saine period. but it see ms like ly (hm it became ra re during the fourtee nth or fi ftee nth century. The red squirre l (Sdurfls vfligari.\·) also became rare and probabl y e xtinct during thi s pe ri od , due to ex tc ns ive de foresta-tion in the country. In the case of birds. the re are re ferences to the protec tio n of spec ies fo r huntin g and faiconry. IIKI

The decline of seve ral fauna species durin g th e fo urteenth ancl fift ee nth ce nturi es is probabl y related to the de fores tati on and huntin g press ure whi ch charac teri ses most of the end of the MiddleA ges in northern Po rtugal. However, it is too s impli sti c to attribute these events to human ac;ti viti es during these ce nturi es. In stead. it see ms more appropriate to COil sid er these c han ges in the fauna as a co nsequ ence o f a longer history of human interve nti o n. in which the fo urt eenth and Aft ee nth centuries are th e Hnal Chapters.

From the sixteen th to the lI illeteewh eel/wries

At the end o rthe fift ee nth ce ntury. there was a demog rnph ic expan s io n in northe rn Portugal , whi ch was (Q be maintained throu gho ulthe first ha lf of (h e s ixteenth

ce ntury. In the last third of the 15005. the Portuguese peopl e IVere af fecLed by several epi sodcs of fnmin e and e pide mi cs, probabl y re latecilO illlc r-annual cl i-mat ic in stab ility associ ated with th e Little Ice Age.1U1 The food cris is at the end o f the s ixteen th ce nt ury was so seve re in regions s uch as T nts-os- Mon tes (N W

Po rtu ga l) that th e kin g deci ded not to co ll ec t tax o n the large amounts o f ce real s imported fro m ab road . In fa ct. one of the main moti vat io ns for th e Portugu ese di scove ri es was to flnd colonies with good co nditi o ns fo r whea t culti vation. In thi s sce nari o of a country with a food shortage an d ove rseas ex pan s ion, the deve lupment o f cattle- raising competed with ag riculture . anu was not fa vo urable 10 fo rest c learance or to th e increase of ag ri cultural nrcas.lO!

22

BRUNO PINTO. CARLOS AGUIAR AND MARIA PARTlDARIO

some cases this led to the limitation of one activity for the benefit of others. For example , in order to maintain the plantation of vineyards which required wood stakes. the Town Hall of Viana do Castelo (NW Portugal) limited the naval and civil industries in certain periods of the second half of the sixteenth century. During the fifteenth and the sixteenth centuries, deforestation reduced the size of the forests that still existed. According to a description from the mid-sixteenth century by Joao de Barros. the scarcity of trees was morc acute in the northeast, whereas the northwest still had wooded areas. The explana-tion for this probably lies in soil and climate condiexplana-tions, at least in the valleys, which are more favourable to the development of trees, and to forest res ilience in the northwest. 103

Although shipbuilding continued to have some impact on the deforestation of northern Portugal, this probably decreased in comparison with other uses of wood. The scarcity of wood justified the implementation of the Law of Trees in

1562, which promoted the reforestation of uncultivated land or private proper-ties. In the interior regions,reforestation of uncultivated lands competed with the exploit<ltion of cattle, honey, shrubs and other products. Considering there were also inefficient enforcement mechanisms and I ittle direction for the reforestation process, this law encountered local resistance and one of the ways to address this problem was to increase wood imports from abroad.III

.1

Between the end of the sixteenth century and mid-seventeenth century. maize was introduced to Portugal as a new crop and became increasingly important to agriculture due to the fact that it took only a short time to mature , afforded greater production and could be grown in harmony with other crops and cattle-raising. Nevertheless. the transition to the seventeenth century is characterised by food scarcity and a consequent decrease in population. Several authors refer to the excessive area of uncultivated lanels as one of the reasons for the lack of cereals in the country. Ill'; In fact. Portugal docs not have good biophysical

conditions for cereal cultivation, which would become clear in the twentieth century with the 'Wheat campaign'.

23

HISTORICAL ECOLOGY OF NORTHERN PORTUGAL

The Ecc les ias tica l Inquiries of 1758 a lready describe the north of Po rtu ga l as

a 1110stl y deforested area. LU1

In the tran s ition from the e ighteenth to the ninetee nth century. there arc ;] Iso seve ral descriptions of Tnis-as-Montes as a deforested region that was espe-c ially dediespe-cated to agriespe-culture and husbandry of espe-cows and hor ses.lO ~ According 10 the first reliabl e and detailed descripti o n by the Prussian botani st Cou nt Hoffmannsegg. it is ev ident that thi s area was mostly deforested at the end of the 1700s, with occasional oak fores ts in sleeper and morc inaccessible areas . Forexalllple, thi s aUlhor wrote that <In the area surrounding V ila Flor r. o,] the usual landscape is reslimed. C uhi vated fi e ld s in a te rritory w ilh o ll ~ t trees and

rull or rock outcrops which are unpleasant to see'. In the case of the Minho.the botanist described it as an agricultural area with dense population. with so me pine and cork oaks in the coas tal areas and oak forests mostly located in low and mid -altitude mountain areas.lI

)'} Other docum ent s refer to the predo minance of

the ches tnut trees and oak s in the int erior of northern Portugal and plant ations of pine trces in the mo re coastal regions.1lO

In the beg innin g o f the nine teenth ce mury. French in vasio ns, c ivil wars and political convul s ion s had a negative effect o n population. agricu hure and animal hu sbandry, but the re st of this ce ntury is charac teri sed by deve lopment s brough t by the e nd of the Old Regime, moderni sation of the country through the agr icultural and indu strial revolutions, and popu lation growth . In J 834, the

enclosures were abolished and the fore st grounds s urrounding convent s and palaces become the o nl y areas of fore s t prot ecti on in the cOllntry. In the second ha lfofthe ninc teelllh ce nt ury. the agricultural area in northern Portuga l incrc:lscd s ig nifi cantl y. which implied a reductio n of unculti vated commo n land a nd the dec line of animal hu sbandry. Nevertheless, so me areas in northern Portuga l suc h as Tras-os-Montcs st ill had about half o f the ir area occupied by un cul-tivated common land in the late nineteenth ce ntury, where animal hu sbandry preva il ed.111 Several authors cont inued lO describe the general defores tation of

northern Portugal and point to refore station as the best solution to reduce the area o f unc ultivated com mon lands.1I2 In this respect. it is curio us to notice

that mos t of the wood used in the constructi o n of the Portuguese rail way was impo rted from abroad . with occasional exception s for wood ex tracted in the ce ntre and sou th of the co untry. llJ Growth of knowledge about forestry , the creation of the Fores try Services and affo restati o n, mainly with Pillus pil/Clsler, of Pe neda-Geres and Estre la mountain s marks the evo lution of the vegetation in northern Portuga l at the end of the nin eteen th ccntury.ll~

24

BRUNO PINTO, CARLOS AGUIAR AND MARIA PARTIDARIO

D. Joan V imposed the death penalty on individuals caught hunting in enclo-sures. The abolition of enclosures in 1834 implied the abolition of the fauna

protection in these areas.l l(,

The brown bear was already rare in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries and probably became extinct when the last individual was shot in the Peneda-Gcres Mountains in 1650. The wild goat (Capra vvrel1aica) also existed in northern Portugal until the end of the nineteenth century and probably became extinct with the capture of the last individual in the Peneda-Geres Mountains in 1890. Several descriptions of the fauna in the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries mention red deer. roe deer and wild boar as common species in this area. However, there was a decline of red deer and, to a lesser extent, of roe deer and wild boar since the end of the eighteenth century . 117 At the end of the

nineteenth century, the red deer was considered extinct in northern Portugal and roe deer only persisted in the Peneda-Geres Mountains. In the case of birds , a document of 1744 confirms the existence of capercaiII ie (TetraD urogallus) in the Peneda-Geres Mountains, which is supported by frequent references to this species in toponyms of this area. This species probably became extinct in the eighteenth or nineteenth century. IIH

From rhe rwemiefh century to 'he preselIl

Demography in northern Portugal during the twentieth century is characterised by an almost constant migration from rural areas to the major cities of the coastal areas, and abroad , motivated by the search for employment and better living conditions. The consequences of this migration were the abandonment of agriculture, which in some cases increased the conversion of agricultural land into forest.ll,) In the transition to the twentieth century, there was extensive

topographical work , motivated by the publication of the first national map of agriculture and forestry in 1910. According to this map , northern Portugal had a low percentage of native forest, which was mostly located in more inacces-sible areas such as steep hills along the waterways.120 This period of transition is also characterised by increasing afforestation, which was mainly directed to uncultivated common lands in the mountains.

2S

HISTORI CAL ECOLOGY OF NORTH ERN PORTUGA L

unculti vated land was also implemented fro m 1938 10 1995 and had its g reates t influence in the mountain s of nOl1hern Portugal.':!1

The change from an ag ric ultural and cattl e-nli sin g society to an urban soc iery implied a reduction of ag ri cultural worke rs and acti vities with co nsequences for th e vegetation. Fo r ex ample. there was an increase in fuel accumulati on in fores ted areas and. co nseque ntly , an increase in the number of fires. whi ch is still a seri o us concern today. Thi s abandonment is still o ne of the morc influenti al fa ctors regarding the vegetatio n in northern Portu gal , since the shrubl and il rea has increased sig nifi cantl y in the last decades. The re is al so a continu ous. but very slow, expansion of nati ve fore st. Howeve r, success ion is often bloc ked (at the human scale), whi ch mean s that the res ilience of the shrubland and human-induced fire kee p the se areas covered w ith pyrophit e shrubl ands ( i.e. shrub encroachme nt).

in relation to the fauna, the first half of the twenti eth century is characteri sed by a change offocus from spec ies which becam e )oc all yextinct orrare in northern Po rtugal , such as red dee r and roe deer, to more common species s uch as wi ld rabbit and red pal1ridge .122 Interest in these species \Vas probably mo ti vated by

the scarcity of large r herbi vores, but al so due to the ir probabl e increase re lated to the ' Wheat campaign' prev iou sly menti oned .

Th e creation of spec ifi c protection law s, Pro tected Areas and ag ri cultural abandonment contributed to halting the dec line of species suc h as the wolf. In the case of the wild rabbit , a keystone spec ies to thi s area , di seases such as myxo matosis and HVD , habit at destructi on and inte nse hunting press ure have cont ributed to its ge neral low de nsity in the north of Po rtugal. C ] However. the re

26

BRUNO PINTO. CARLOS AGUIAR AND MARIA PARTlDARIO

TABLE 1 (continues on facing page).

Chronology

Tran si tion to the Holocene

l'vlesolithic

Neolithic

Beginning of period

16.000 yr BP (ie. XV mil. Be)

10,000 yr BP (i.e. IX miL Be)

Late VllEarly V millennium ]J(

Human impact on natural resources

Hunting and gathering.

Hunting and gathering activities probably centred in coastal and fluvial areas . Small-scale human

deforestation s.

Beginn ing of agro-pastoral way of life .

Bron ze Age Early 1II millennium I3C Intensification of agriculture and animal husbandry.

Iron Age Early I millennium Be Invasions of Indo-E uropean people. with reduction of agriculture and increase of animal husbandry.

Roman period 11/1 century Be

German period Early V century ;\ll

Muslim period Early VIII century AD

Medieval period Early Xl century,\l)

Modern Period XVI century AD

COlltcmporary XX century A ll

Period

Roman invasion. with large-scale cxpnnsion 01 agr ic ulture and demographic increase.

German invasio n, with frequent episodes of pillage and wars; demographic decrease.

Muslim invasion, with reduced prese nce after mid VIll century; scarce populat io n.

Christian Reconquest, increased farming <llld demographic growth until XIII century. Successive fam ines and plagues since the m i d~XIV eenlllry alld demograph ic recovery after mid -XV ce ntury .

Cycles of demographic growth an d reduction; expansion of agriculture to marginal lands.

HISTORI CAL ECOLOGY OF NORTHERN PORTUGAL

TABLE I (continued from fac ing page) ..

Main vegetation changes

Expans ion of the forest (first.

Betllia sp .. followed by PillllS

~ p .• rc placed late r by Qllerc/f,," sp.) ,lIld decl ine o f ste ppe vege tatio n.

Gr:ldual do minatio n of Quercus

sp. forests . wi th decline o f Pi/m ,I' sp. to higher altitudes ; Mosak of dosed and open vegetation.

Forest decline due to

dcfon.:statiOIl for agro-paSIOrrt !

activit ies . which started around mid · IV mi llenni um Be .

Large-sca le forest decl ine in the II m il le nnium Be .

Forest decl ine, probably lIul.! to

both dimate change and actions

o f the Indo-European people,

Expansion of d efore station to

the valle ys . with clearance of fore st ;lIld swa mp a reas .

Forest rel·o very.

Conti nuatiun uf fure st reco very.

Forest decline and expansion of agricultu ral and uncultivate d areas.

Forest decl ine and maintenance

o f ng ricu ltur..Il and unculti vated 'ITeas.

Shru b encroachment, s low forest recovery and growth of industrial afforestation

Main fauna dUln~cs

Decline of alpine spe cies and colonisatio n of woodl<lnd-adapted spec ies

Decl ine of auroc hs and wild horse.

Aurochs becomes ex tinct

Wild horse heco mes c xtim:t; probable decline of fores t species.

Exti nction of beaver. red squirrel and pussibl y a small equid

Ex tinc tio n o f brown bear. c ape rc aiJlie . wild gnm and red d eer: decline of roc dee r a nd w ild boar.

Ex tinction of gre y partridge and decline o f wll{] rabbit: Re-establishment of wild gO;I1. re d squ irrel and red deer "nd recent

Main climate chunges

Climate warming

Cl imate wanning Ana thermic phase

( 10,000-7 500 yr HPJ

Temperature aod humidity rc achcd a peak. Climmic Optinm m (7500- 2,500 yr I3P)

Te mpera tu re and hu m idity reached a peak .

Cl imatic Optimum

(7.500- 2.500 y r BP)

First Co ld Period of the Subatlanti c

(975 to 250 c al. nc)

Roman War m Period (250 ca l AC to 450 cal AD )

Dark Ages C n ld Pe riod (450 to 950 ca l AO)

Dark Ages Cold Period (450 to 950 ca l An )

Medieva l Warm Pl.!riud (950 to 1400 cal An)

Lill ie Ice A ge

(1 400 to 1850 ca l. AD )

Lillie Icc A ge

(140 0 to IR5 0 ca l. AD )

R~e~nt warming

28

BRUNO PINTO, CARLOS AGUIAR AND MARIA PARTlDARIO

DISCUSSION

The ecological and historical information about the deforestation process from the Neolithic onwards supports the idea of a spatial differentiation in northern Portugal, beginning on the high plateaus of this region and extending later to the valley areas. This development of deforestation seems to be associated with changes of social systems (e.g. increase of sedcntarisation with the location of communities in areas of mid-mountain), greater integration of agro-pastoraI activities, development of tools and techniques which caused erosion of deeper soils, and possibly climatic change (higher climatic irregularity increases agri -cultural risks on the high plateaus and promotes agriculture in the valleys, where the temperature is more temperate).

These changes in the vegetation of northern Portugal during the Holocene follow the model suggested by Boserup (1965) of an increase (which can be intermittent) of the area and intensity of agro-pastoral use of the land over time due to population growth. Despite the limited information in this area, there is a general trend of forest decline after the Neolithic , which is interspersed with periods of recovery of the vegetation related to decrease of human pressure on natural resources. 125 For example, it is known that the political-administrative instability and the reduction of human population during the Germanic domina-tion of this area between the fifth and eighth centuries enabled forest recovery, which was probably extended to the period of conflict between Muslims and Christians.

HISTORI CAL ECOLOGY OF NORTHERN PORTUG AL

reinforces the direct effect that the climarc continued to ha ve on the vegelation until the present.

In terms of fauna , the natural herbi vores were probably reduced w ith the ex tinction of species such as wild horse , aurochs and European beaver. Consider-ing the long periods of decline of the forest s in the area. it seems lik ely that the changes brought by agro-pastoral societies re sulted in a reduction of woodland

species and an increase in species which prefer open habitats. In some cases , forest decline see ms to be the main ca use of species ex tincti ons, such as of

brown bear, red squirre l and capercaillie . In other cases, suc h as the extinctions ofwiJd goat , red deer and grey partridge , the main cause was probabl y excess ive hunting . The recent trcnd is for the recovery of the fauna, which seem to have bene fited from the creation of Protected Areas , specific protection laws and the expa nsion of species fro m northwestern Spain .

Based on these vegetation and fauna changes , it is possible to argue for a ' long-term ecologi cal trnn sformation ' of northern Portu gal during the Holocene.ln In the beginning of the Ho locene.c1 imate seems to have been the most imp0rlant tri gger of change in thi s area, but human impact probably became preponderant in the last 5000 yea rs. Neve l1heless, the climate co ntinued to have a signiticanl direct and indirect rol e in these changes, influencing factors sllch as the rhythm of forest growth and demography. According to seve ral authors , po sitive and negative feedback cyc les between human action s and natural systems kept the Mediterranean ecosystems resilient and may have. to some extent. replaced natura l di sturbance regimes such as fires, herbi vory, wind-throws and land-slides.12!< In this process, ecosys tems flipped into new alternati ve stable states, in order to incorporate the dec rease of natural di sturbance and the inc rease of hum an-i nduced di sturbam;e. However. the tran sit ion from mature oak fo rest to lheearly- to mid-s uccess ional vegetation whi ch is co mmon in pre se nt land scapes. and the extinction of fau na species, impli ed the loss of ecologi ca l functions which were not fully co mpe nsated by human -induced actions. m For examp le , th e European beave r is gene rall y con sid ered a keystone species. because the ir browsing and dammin g acti vities indu ce signi ficant alteration in th e structure and co mposit io n of the habitats where they li ve. DO Such modifi cati o ns were lost after the ext inction of this speci es in the fifteelllh ce ntury. and were no t replaced by the domesti c herbi vores present in the area.

30

BRU NO PINTO. CA RLO S AGU IAR AN D M ARIA PARTIDARIO

dome stic animal s is an effi cient form of controlling shru b e ncroac hment , thu s increasi ng the mosa ic of habitats wh ic h arc known to benefit biodiversity.

Thi s c haracteri stic of hi g h resi li e nce has a lso bee n recentl y attributed by Butzer (2005) to hum a n communities w hi c h have li ved in the Mediterranean regi o n for mi ll e nnia. I n the case of northe rn Portugal , ethnograp hic and histori-ca l informat io n concerning villages in the mountain ran ges also revea ls severa l tre nd s that ca n be interpreted as soc io-cco ll omi ca i adap tati o ns to limited natural reso urces. For example, the communitary organi smion whic h was prese nt in many vill ages inc reased the e ffi ciency of ac tiv ities suc h as catt le- raising and limited grazi ng a nd/or ag ri c ultural pressure 011 com lllunity la nd s. These

popula-tio ns al so promo ted b irth cOnlro l th rough the trad ipopula-tio ns o f marry ing o nl y one o f the s iblings ) late ma rriage , sex ua l a bstine nce a nd tradi ti o nal met hod s o f fe rtilit y <':0111ro l. For ex ample , in the vi ll age o f Rio de O no r (NE Portuga l), the

nllmber o f people was re lalively slable. al leas!. belween 1796 and 19 11 . Fo

l-low ing the ex te rna l inOue ncc of yo un g me n returnin g fro m World War One there was increas in g di srespect fo r these trad itio ns , whi c h led to nn inc rease in the number of peop le during the subsequent years and promoted soc ia-economic di sequilibrium. Other strategies to avoid overcxp loil<lti oll of natural resources in thi s region include the lise of alte rnati ve sources of in come and periods of mass ive e migration.I-,-'

In conclu sio n , the e nvironmental hi story of no rth ern Portu gal co nfirms a long-te rm impat: ( o f both natural and human -indu ced c ha nges that c haraclong-teri ses the Med it erranea n reg ion. in which anthropogeni t: influ e nce became the main factor in the last 5000 years. In the transformati o n of the ecosystems, they probabl y flipped throu gh alte rn ati ve stable states in order to incorporate an increase in human act io n and a dec rease in natura l d isturbance whi ch imp li ed a s igni fican t loss of ecolog ica l fun ction. Nevertheless , the high res ilience of ecosystems has e nabled th e ir sustainabililY over e ighl mill e nni a and has all owed a recove ry of the vegetat io n a nd fauna during recent decades.

NOTES

We arc grat eful to Dr. Simon Da vis and to Dr. rim van del' Knaap for the ir contribu-ti ons to this arcontribu-ticle. This study was fu nded by the POr\uguese Foundacontribu-ti on for Science and Tech nology.

HISTORICAL ECOLOGY OF NORTHERN PORTUGAL

7 Costa et aJ. 1998 .

~ Mesquita 2005.

9 Agroconsultores and COB A 199 1 . 10 Naveh and Leibennan 1990.

"INE 2005.

': Ramil -Rcgo et al. 1998.

1.1 Allen ct at. 1996.

14 van def Knaap and van Leeuwen 1995, 1997.

15S anc hes 1997: Lemos \993, 1997.

t ile .g . Link 1803.

17 e.g. Leao 1735.

I ~ e .g. Devy-Vareta 1985. 19R6: Radich and Alves 2000. I') e.g. Pinheiro 1987.

co e.g. Catty 1999: Cabral et al. 2005: Dias 1948 . 1953.

:1 Guerreiro [981 ; Ruddiman and Macintyre J 981.

:'2 Coudc-Gausscn 1981; Coude-Gaussen and Denefle 1980. ' .' Allen et al. 1996.

1·1 Munoz-Sabrino et 3 1. 2004: Ramil -Rego et al. 1996 a.b; Cardoso 2002. " Zilh50 1997.2003.

x) Cardoso 2002; Zilh50 2003.

~7 Mendes . 1968: Vasconcelos 1980.

2N An tunes 1993 : Araujo 2000; Burke et al. 2003 .

29 Baptista and Gomes 1995; Aura et al. 1998 .

.1 11 e.g. Aura et al. 1998.

3 1 Antunes 1993; Barnosky et al. 2004; Burney and Flannery 2005 .

.12 Munoz-Sobrino et al. 2004, 2005; Allen et al. 1996: Ramil-Rcgo et at. 1998; van der

Knaap and van Leeuwen 1995 ,1997: Mateus 1992 .

33 Honrado 2003 ; Figueiral 1995 ; Figue iral and Carca illct 2005 .

.

,.1 Zilhao 1993.2000; Aura et al. 1998 .

~~ Davis 2005.

3(' Zilhao 2000: Cardoso 2002.

J1 Munoz-Sobrino et at. 2005: Araujo 2000: Bicho 1994 .

. 1H Blanco el al. 1997; Munoz-Sobrino ct al. 2005: Brown 1997: Araujo 2000.

:; ~ Grove and Rackham 200 1.

~Il Vera 2000.

~J van der Knaap and van Leeuwcn 1995,1997 .

32

BRUNO PINTO, CARLOS AGU IAR AND MARI A PARTIDAR IO

Ji e.g . Grove a nd Rack ham 200 1.

-18 Jorge 1990 .

-\'} Mufioz-Sobrino el ill . 1996.

5tJ van del' Knaup and van Lee uwen 1995.

~ I Mufioz-Sobrino ct al. 2004 : All en c( al. 1996: Ramil-Rego et al. [998.

5~ Cardoso 2002 ; Diamond 1997: Sanches 1996.

5' Sanches 1997 : Figueira l and Sanches 200 3.

-'" Sa nc hes 1996: Jorge 1990 .

5~ Bettencourt 1995: Figuei ral and Sanc hes 2003: Di amond 1997.

~b Figueiral and Sanches 2003.

~7 Carcaillet et a!. 2002 .

. ~~ C ortazar 19XH .

~ 'J Jorge 1990.

fI) Figueiral and Sanche s 2003: Figueiral and Bellcncourt 2004: Jorge J 9R8.

M Laulensach 1988. 1989. f>~ Jo rge 1990.

(,J Ca rdoso 2002.

f>.I Monteiro- Rodrigues 2000. 2002: Valente 2004.

f>_~ Antunes 199 3: Cardoso 2002; Levi ne 1999.

(,/) Gordon et al. 2004: Pykala 2000.

h? Bengtsson ct aJ. 2000: Naveh and Carmel 2003 : Grove and R<lckhalll 20{)!: Perevo-lotsky and Sel ig man 1999.

(0/1 Fabiao 1992: Lautc nsac h 1988 .1989.

/oM Ruiz-Zapata cl a1. 1995.

70 Mart ins 1997: Le mos 1997.

7 ) Fabiao 1992: Cardoso 1994.1997: Lcmos 1997: Alvarcz-Sanchi s 2000. 71 Si lva and Gomes 1994; Lemos 1997: C:mloso 1994: Jorge 1990.

7.1 Marl ins 1997: Oubin;} 2003: Fi guc iral 1996: Lau\cllsac h 1989: Cardo so 1994. 1997: Guerra 1995: Figueiral 1996.

,., Mat1ins 1997: L"lI lc nsac h 198 8 . 1989 .

75 Fabiao 1992: A lardo 1987.

7" Fab iao 1992: AI" rciio 1987: Lemos 1993. 77 Alarcao 1987.

7)( Leguay 1993: Fabiiio 1992. Lautctl sa<.: h 1988 . 19X9 . 7') Ramil- Rego ct al. 1996 a .b .

~ u Mattoso 1992a: Filbii'io 2004 . Lau lc l1 sach 19S5. 1989: Lcguay 1993: Trindade 1981.