I UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SÃO CARLOS

CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS BIOLÓGICAS E DA SAÚDE

PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ECOLOGIA E RECURSOS NATURAIS

Biodiversidade de Selenastraceae (Sphaeropleales, Chlorophyceae): características morfológicas e sequenciamento dos marcadores moleculares 18S rDNA, rbcL e ITS

como base taxonômica tradicional.

Thaís Garcia da Silva

Orientador: Prof. Dr. Armando Augusto Henriques Vieira

São Carlos – SP 2016

Ficha catalográfica elaborada pelo DePT da Biblioteca Comunitária UFSCar Processamento Técnico

com os dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a)

S586b

Silva, Thaís Garcia da

Biodiversidade de Selenastraceae (Sphaeropleales, Chlorophyceae): características morfológicas e sequenciamento dos marcadores moleculares 18S rDNA, rbcL e ITS como base taxonômica tradicional / Thaís Garcia da Silva. -- São Carlos : UFSCar, 2016. 148 p.

Tese (Doutorado) -- Universidade Federal de São Carlos, 2016.

IV “Longe se vai sonhando demais

Mas onde se chega assim? Vou descobrir o que me faz sentir Eu, caçador de mim.”

V Agradecimentos

Primeiramente, ao Dr. Armando Augusto Henriques Vieira por ter me aceitado como estagiária e aluna de doutorado. Agradeço imensamente por todo apoio e dedicação nesses 6

anos de trabalho no Laboratório de Ficologia, me mostrando novas possibilidades de aprendizado e estimulando o meu caminhar na pesquisa e conhecimento na ficologia. Sinto-me iSinto-mensaSinto-mente honrada por ter trilhado um caminho tão importante de minha vida sob sua

tutoria e me espelho no seu exemplo de verdadeiro amor e dedicação à profissão.

À minha co-orientadora Dra. Célia Leite Sant’Anna, Núcleo de pesquisa em Ficologia

do Instituto de Botânica, pelo grande estímulo que me deu para que eu prosseguisse na taxonomia e que não desanimasse em momentos decisivos desta jornada, dando valor ao que eu acreditava ser importante neste estudo.

À Dra. Christina Bock, Departamento de Biodiversidade da Universidade Duisburg-Essen, por ter me aceitado como sua aluna, pelo grande conhecimento sobre biologia

molecular que humildemente me transmitiu em minha estadia na Alemanha e por ter confiado que eu seria capaz de enfrentar esse desafio “selenastrágico”.

À Dra. Sabina Wodniok pelo auxilio nas análises de microscopia eletrônica.

Ao Dr. Jens Boenigk por ter permitido à Christina me receber como aluna no Departamento de Biodiversidade e pelo auxílio burocrático envolvido.

À CAPES pela concessão da bolsa de estudos nos 12 primeiros meses de doutorado. À Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, FAPESP, pelas concessões das bolsas de estudos no Brasil (Processo n° 2012/19520-1) e, no exterior por

meio do programa “Bolsa Estágio de Pesquisa no Exterior” (Processo n° 2013/17457-3).

À Universidade Federal de São Carlos, ao Instituto de Botânica de São Paulo e a

VI trabalho e ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia e Recursos Naturais, pela oportunidade de aprimoramento científico.

Ao Programa de Pós-graduação em Biodiversidade Vegetal e Meio Ambientedo Instituto de Botânica de São Paulo, pela oportunidade de aprimoramento científico por conta

das disciplinas cursadas.

Ao Luizinho pelo apoio durante as coletas do Projeto Biota e pelo exemplo profissional que nos dá.

Aos colegas e amigos do Laboratório de Ficologia pelos momentos compartilhados: Naiara Carolina, Cilene, Inessa, Fabrício, Luiz, Letícia, Alessandra, Helena, Guilherme,

Ingritt, Chico, Lucas, Érica, Moira (e, possivelmente, mais alguns que devo ter me esquecido...rsrsrs). Meu muito obrigada por tudo o que foi vivido.

À Inessa por clarear meus pensamentos e não me deixar ser tão tendenciosa na

taxonomia, no auxílio com a biologia molecular, na redação de artigos e crises existenciais no final deste processo.

À Zezé por ter me ensinado o básico da taxonomia para as análises das minhas amostras quali e quantitativas, ainda na minha iniciação científica. Por um acaso do destino você me sugeriu procurar o Armando para tentar uma pós e aqui cheguei.

Aos meus amigos muito queridos da UDE e que tornaram minha estadia muito agradável: Julia, Lars, Vesna, Yesim, Edward, Elif, Saskia, Philpp, Sabina, Nikoletta,

Fernando, Saeed, Farnoush, Sarah, Susy, Beate e Christina.

À Andrea pela companhia agradabilíssima em todas as vezes que fui ao Instituto de Botânica, pelas conversas, hospedagem, por me encorajar na pesquisa e na vida.

Agradeço especialmente ao Luiz pelo apoio cotidiano no laboratório, pelas conversas durante o trabalho e, principalmente, por ter dividido a “nossa” salinha de microscopia por

VII Aos funcionários do PPGERN: João, Roseli e, especialmente Beth (que eu encontrava com frequência ao retornar para casa) pela ajuda com a burocracia envolvida neste

doutorado.

Aos meus amigos por todos os momentos durante minha caminhada. Não citarei nomes porque fatalmente esquecer-me-ei de alguém.

Ao Neto, pelos importantes jogos de forca que praticávamos durante as aulas entediantes e por ter feito esses momentos mais leves.

À Priscilla por ter estado ao meu lado por algum tempo neste processo.

Muitos foram importantes pra que eu chegasse aqui mas, agradeço sobretudo à:

minha mãe, vó e irmã por estarem ao meu lado e me ensinarem coisas que nem consigo por no papel de tamanha grandeza.

À minha família toda por ter torcido por mim, pelo carinho e pelo porto seguro que só

uma família, mesmo que torta, pode propiciar.

Aos meus mestres da vida inteira, que de alguma forma me ajudaram a construir o

VIII Resumo

A filogenia da família Selenastraceae foi investigada por microscopia ótica, análises moleculares dos marcadores 18S rDNA, rbcL, ITS1-5,8S-ITS2 e ITS-2. Várias características morfológicas tradicionalmente utilizadas para identificação de gêneros e espécies foram investigadas. Todas as cepas de Selenastraceae estudadas têm pirenóides nus dentro do cloroplasto, exceto o gênero Chlorolobion, que apresentou pirenóide amilóide. As análises moleculares mostraram que nenhum critério morfológico isolado considerado até agora é significativo para a sistemática do Selenastraceae, mas o uso de um conjunto de características morfológicas pode ser adequado para identificar espécies dos gêneros Ankistrodesmus, Chlorolobion, Kirchneriella, Raphidocelis e Tetranephris. As análises

filogenéticas moleculares mostraram que os gêneros Monoraphidium, Kirchneriella e Selenastrum são polifiléticos e não distinguíveis como gêneros. O morfotipo de Selenastrum

IX Abstract

X Lista de siglas e abreviaturas

18S rDNA 18S DNA ribossômico (18S ribosomal RNA) 28S rDNA 28S DNA ribossômico (28S ribosomal RNA) 5.8S rDNA 5.8S DNA ribossômico (5.8S ribossonal RNA) BP Probabilidade Bayesiana (Bayesian probability) CB Christina Bock

CBC Mudança de bases compensatórias (Compensatory base changes) CCMA Coleção de culturas de Microalgas de Água

Comas Augusto Abilio Comas González

DNA Ácido desoxirribonucleico (desoxyribonucleic acid) gen. nov. Gênero novo

ITS Espaçador interno transcrito (Internal transcribed spacer)

ITS1 Espaçador interno transcrito situado entre os genes 18S rDNA and 5.8S rDNA ITS2 Espaçador interno transcrito localizado entre os genes 5.8S rDNA e 28S rDNA

nas algas

KF Alena Lukešová Culture Collection KR Lothar Krienitz

LM Microscopia ótica (Light microspy)

MCMC Monte Carlo via Cadeias de Markov (Markov Chain Monte Carlo) MFE Energia mínima livre (Minimum free energy)

ML Máxima verossimilhança (Maximum likelihood) MP Máxima parsimônia (Maximum parsimony) NCBI National Center for Biotechnology Information

XI NJ Agrupamento de vizinhos (Neighbor-joining)

PCR Reação em cadeia da polimerase (Polimerase Chain Reaction) PP Probabilidade posterior (posterior probability)

rbcL Subunidade grande da RUBISCO (RUBISCO large subunit) rRNA Ácido ribonucléico ribossômico (ribosomal rubonucleic acid) SAG Sammlung von Algenkulturen der Universität Göttingen

SEM Microscopia eletrônica de varredura (Scanning Electron microscopy) sp. nov. Espécie nova

SSU rRNA Subunidade menor do ribossomo (ribossome small subunit)

XII Lista de figuras

Figure 1.1-1.5. 1.1. Messastrum gracile. Original picture of strain CCMA-UFSCar 622 showing a frontal view of colony; 1.2. Selenastrum bibraianum. Original picture of strain CCMA-UFSCar 125 showing a frontal view of colony. 1.3-1.4. Curvastrum pantanale. (1.3) Original picture of strain CCMA-UFSCar 350, showing free cells and colony; (1.4) Original picture of strain CCMA-UFSCar 350, showing cells in autospore liberation. presenting a cell wall remnant (arrowhead) and protoplasm cleavage (star). 1.5. Ankistrodesmus arcuatus. Original picture of strain CCMA-UFSCar 24, showing free cells and colony. Note autospore formation (star) and mucilaginous lump (arrowhead). Scale bar 10 μm………..77

Figure 1.6: Maximum–likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree inferred from rbcL gene sequences of some members of Selenastraceae. Support values correspond to Bayesian PP (Posterior Probability), ML BP (Bootstrap), MP (Maximum Parsimony) BP, NJ (Neighbor-Joining) BP. Hyphens correspond to values <50% for BP and <0.95 for PP. Scale represents the expected number of substitutions per site. Strain numbers used as mentioned in Table 1………..78

Figure 1.7: Maximum–likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree inferred from 18S rDNA gene sequences of some members of Selenastraceae. Support values correspond to Bayesian PP (Posterior Probability), ML BP (Bootstrap), MP (Maximum Parsimony) BP, NJ (Neighbor-Joining)BP. Hyphens correspond to values <50% for BP and <0.95 for PP. Scale represents the expected number of substitutions per site. Strain numbers used as mentioned in Table

XIII Figure 1.8: Scanning electron micrographs of Curvastrum pantanale (CCMA-UFSCar 350) in culture. Scale bar, 10 µm. (a) typical colony formation, (b) young cells detaching from each other, (c) young cells, note the autospores position………..80

Figure 1.9: Transmission electron micrographs of Curvastrum pantanale (CCMA-UFSCar 350) in culture. Scale bar, 1 µm. Key to labeling: CW = cell wall, C = chloroplast, D = dictyosome, ER = endoplasmic reticulum, L = lipid drop, M = mitochondrion, N = nucleus, P = pyrenoid, PV = polyphosphate vacuole, S = starch grain. a) longitudinal section; cell presenting lipid drops, polyphosphate vacuoles (arrowhead), chloroplast penetrated with starch grains, and a central pyrenoid. b) detail of figure a, where an endoplasmic reticulum (arrowhead) can be observed. c) longitudinal section; cell presenting polyphosphate vacuoles on both cell apexes, mitochondria, chloroplast filled with starch grains and a central pyrenoid. d) cross section; chloroplast containing starch grains and a pyrenoid situated at the left, a central nucleus can be observed. e) longitudinal section; mature cell containing a central nucleus, mitochondrion and pyrenoid (upper part). All the cell content is surrounded by a cell

wall………81

XIV cell is a mature individual containing many starch grains on the chloroplast, some polyphosphate vacuoles (arrowhead), nucleus and big lipid drops. e) cross section; dense chloroplast with starch grains. Two big polyphosphate vacuoles (arrowhead) and a nucleus can be observed. All the cell content is surrounded by a cell wall………...82

Figuras suplementares

1.A) ITS-2 model for the type strain of Selenastrum bibraianum (CCMA-UFSCar 125). In black boxes are the different bases compared to strain Messastrum gracile (CCMA-UFSCar 622)……….………..83

1.B) ITS-2 model for the type strain of Selenastrum bibraianum (CCMA-UFSCar 125). In gray boxes are the different bases compared to strain Selenastrum bibraianum (CCMA-UFSCar 47) and black boxes compared to Selenastrum bibraianum (CB 2012/47).…….…..83

1.C) ITS-2 model for the type strain of Messastrum gracile (CCMA-UFSCar 622). In gray boxes are the different bases of M. gracile (CCMA-UFSCar 470) and black boxes M. gracile

(CCMA-UFSCar 5). ………...………..83

1.D) ITS-2 model for the type strain of Curvastrum pantanale (CCMA-UFSCar 350). In gray boxes are the different bases of C. pantanale (CCMA-UFSCar 608)………..84

XV nov. 2 sp 1. (CCMA-UFSCar 342); 5. Gen. nov. 2 sp 2. (KR 1979/222). Note the cell wall remnant (arrowhead). Scale bar 10 μm. ……….135

Fig. 2.6-2.8. Drawings of light microscopical characters. 6. Kirchneriella pseudoaperta (CCMA-UFSCar 346). 7. Kirchneriella obesa (CCMA-UFSCar 345). 8. Kirchneriella lunaris (CCMA-UFSCar 87). Scale bar 10 μm.……….136

Figure 2.9: Maximum–likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree inferred from ITS1-5.8S-ITS2 gene sequences of some members of Selenastraceae. Support values correspond to Bayesian PP (Posterior Probability), ML BP (Bootstrap), MP (Maximum Parsimony) BP, NJ (Neighbor-Joining)BP. Hyphens correspond to values <50% for BP and <0.95 for PP. Scale represents the expected number of substitutions per site. Strain numbers used as mentioned in Table 1.

……….…………137

Figure 2.10: Maximum–likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree inferred from 18S rDNA gene sequences of some members of Selenastraceae. Support values correspond to Bayesian PP (Posterior Probability), ML BP (Bootstrap), MP (Maximum Parsimony) BP, NJ (Neighbor-Joining) BP. Hyphens correspond to values <50% for BP and <0.95 for PP. Scale represents the expected number of substitutions per site. Strain numbers used as mentioned in Table

XVI Lista de tabelas

Table 1.1. List of studied strains with origin information and GenBank accession numbers for 18S rDNA and rbcL genes and ITS-2 secondary structure. Sequences in bold letter acquired from GenBank. CCMA - UFSCar, Coleção de culturas de Microalgas de Água Doce – Universidade Federal de São Carlos ; SAG, Sammlung von Algenkulturen der Universität Göttingen, Germany; UTEX, The Culture Collection of Algae at the University of Texas at Austin. For own isolates, the initials of the isolator were given: CB, Christina Bock; KR, Lothar Krienitz; Comas, Augusto Abilio Comas González. KF, Alena Lukešová. The strain AN7-8 belongs to Fawley et al, 2004. ………...64-69

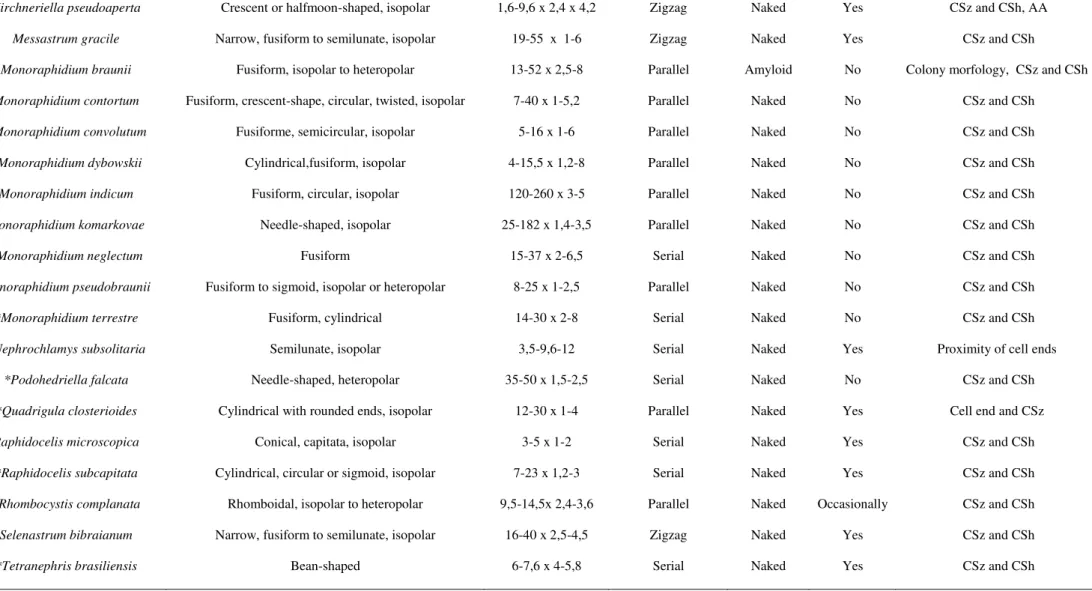

Table 1.2. Morphological characteristics of algal strains used in this study. For species marked with asterisk, see taxonomic references on Material and Methods. ND: Not described………..70-71

Table 1.S3. 18s rDNA, rbcL and ITS primers used for amplification and sequencing of

Selenastraceae………..72-73

XVII Comas, Augusto Abilio Comas González. Accession number indicated with x will be deposited prior to publication………..……123-128

Table 2.2. Morphological characteristics of Kirchneriella-like strains used in this study. Aa: autospore arrangement; P: pyrenoid; C: colony; M: mucilage……….………129

XVIII Apresentação da tese

A tese foi elaborada para conter os itens: (1) Introdução geral; (2) Hipóteses e Objetivos; (3) Capítulos (com resultados e discussão); (4) Discussão geral; e (5) Conclusões.

Cada capítulo será apresentado no formato de artigo científico: com resumo, introdução, material e métodos, resultados, discussão, referências bibliográficas e material suplementar. Este formato foi escolhido para facilitar a publicação dos resultados obtidos. A introdução geral está em português, bem como a discussão geral e a conclusão.

O primeiro capítulo encontra-se formatado para a publicação na revista Fottea, à qual foi submetido e aceito. Neste capítulo, apresentamos os resultados de uma análise filogenetica utilizando os marcadores rbcL e 18S rDNA.

No segundo capítulo da tese abordamos o complexo Kirchneriella-Raphidocelis-Pseudokirchneriella, os menores organismos de Selenastraceae, em um estudo filogenético

baseado em 18S rDNA e na analise multigene dos marcadores ITS1-5.8S-ITS2, formatado nos moldes da Journal of Phycology, possível periódico para submissão.

XIX Sumário

Introdução Geral ... 1

Sistemática de Chlorophyta ... 1

Taxonomia e filogenia de Selenastraceae (Blackman & Tansley) ... 4

Conceitos de espécie em algas verdes ... 8

Referências bibliográficas ... 10

Hipóteses ... 18

Objetivos ... 19

Capítulo 1: Selenastraceae (Sphaeropleales, Chlorophyceae): rbcL, 18S rDNA and ITS-2 secondary structure enlightens traditional taxonomy, with description of two new genera, Messastrum gen. nov. and Curvastrum gen. nov. ... 20

1.1. ABSTRACT ... 21

1.2. INTRODUCTION ... 22

1.3. MATERIAL AND METHODS ... 25

Algal cultures and microscopy. ... 25

DNA extraction, PCR and sequencing. ... 26

Phylogenetic analyses ... 28

ITS-2 secondary structure prediction. ... 29

1.4. RESULTS ... 29

Genera and species descriptions. ... 29

Microscopy ... 34

Phylogenetic analyses ... 38

XX Morphological criteria with high taxonomic value in traditional systematics of Selenastraceae

...41

Remarks on genera. ... 44

General view ... 47

1.6. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... 52

1.7. REFERENCES ... 52

Capítulo 2:Kirchneriella morphotype (Selenastraceae, Chlorophyceae) reveals four molecular lineages, including two new genera and five species1. ... 85

2.1. ABSTRACT ... 86

2.2. INTRODUCTION ... 87

2.3. MATERIAL AND METHODS ... 89

Algal cultures and microscopy ... 89

DNA extraction, PCR and sequencing ... 90

Phylogenetic analyses ... 91

2.4. RESULTS ... 92

Taxonomic proposals. ... 92

Morphological analysis ... 96

Phylogenetic analysis ... 98

2.5. DISCUSSION ... 101

Taxonomic and molecular studies on Kirchneriella morphotype ... 102

Remarks on genera ... 107

Selenastraceae: highlights on small-celled genera phylogeny ... 111

1 Introdução Geral

Sistemática de Chlorophyta

O termo Chlorophyta refere-se, tradicionalmente, ao grupo de algas verdes, que se caracteriza por cloroplastos com membrana dupla, amido como polissacarídeo de reserva, tilacóides empilhados e presença de clorofila a e b (Friedl 1997, Chapman et al. 1998). Contudo, alguns gêneros reconhecidamente pertencentes à Chlorophyta, perderam seus pigmentos em processos secundários (Pringsheim 1963). Uma enorme diversidade morfológica está inclusa em Chlorophyta, compreendendo desde organismos unicelulares cocóides ou flagelados, coloniais, filamentosas ramificadas ou não, membranosas e cenocíticas (van den Hoek et al 1988).

A divisão Chlorophyta abrange organismos viventes em ambientes de água doce ou marinha, sendo um dos principais produtores primários em ambientes aquáticos (Bock 2010). O hábito dessas algas pode ser epifítico, planctônico e algumas espécies vivem em comunidades edáficas.

2 delinearam classes, famílias, gêneros e espécies (Kornmann 1973, Ettl 1981, Komárek & Fott 1983, Mattox & Stewart, 1984).

O advento das análises moleculares aprofundou a visão do sistema natural de classificação de algas verdes (Melkonian & Surek 1995, Friedl 1997, Lewis & McCourt 2004), trazendo o consenso de que as algas verdes evoluiram em duas grandes linhagens, chamadas de Clado Charophyta e Clado Chlorophyceae sensu Lewis & McCourt (2004).

O Clado Charophyta (ou Streptophyta sensu Bremer 1985) compreende as plantas terrestres e um número de algas verdes, grupos como Mesostigmatophyceae, Chlorokybophyceae, Klebsormidiophyceae, Zygnemophyceae, Coleochaetophyceae e Charophyceae.

O Clado Chlorophyceae (ou Chlorophyta) compreende a maioria das algas que eram tradicionalmente referidas como algas verdes. Este clado contém os três grupos monofiléticos de algas verdes (Chlorophyceae, Trebouxiophyceae e Ulvophyceae) e o clado parafilético traz Prasinophyceae, que contém, ao menos, seis diferentes clados (Lewis & McCourt 2004) na parte basal de Chlorophyta (Fawley et al. 2000, Lewis & McCourt 2004, Marin et al. 2010).

A origem polifilética de várias famílias e gêneros definidos morfologicamente foi revelada ao combinar dados moleculares e morfológicos. Um estudo com o gene SSU rRNA mostrou que a morfologia “Chlorella-like” evoluiu independentemente

dentro de Chlorellaceae e Trebouxiophyceae (Huss et al. 1999). Chlorella vulgaris Beijerinck, representada pela autêntica cepa SAG 211-11b, estabeleceu uma linhagem dentro de Chlorellaceae (Trebouxiophyceae), ficando, por conseguinte, o nome genérico Chlorella Beijerinck válido apenas para os membros deste grupo (Huss et al. 1999,

3 algas “Chlorella-like” (Marinichlorella Aslam et al. 2007, Kalinella Neustupa et al.

2009) e espécies conhecidas (como Chlorella saccharophila, C. ellipsoidea) geraram novas combinações para gêneros diferentes (por exemplo, Chloroidium Nadson) (Aslam et al. 2007, Neustupa et al. 2009, Darienko et al. 2010).

Assim, admite-se que os caracteres morfológicos são particularmente sujeitos à convergência ou evolução paralela, podendo apresentar plasticidade fenotípica. Formas celulares simples podem subestimar a diversidade genética, como demonstrado no caso de Chlorella, onde o formato "bola verde" foi observado em várias linhagens filogenéticas independentes, correspondendo a gêneros e espécies diferentes, definidos por biologia molecular (Huss et al. 1999, Aslam et al. 2007, Neustupa et al. 2009).

Diferentes espécies do gênero Scenedesmus, quando submetidos a crescimento sob a influência do zooplâncton Daphnia, apresentaram um aumento significativo do tamanho da colônia (Trainor 1998). Ademais, indivíduos isolados de Scenedesmus podem exibir características morfológicas que abrangem grupos e conduzirem a sobrestimação da riqueza de espécies (Trainor 1998).

4 Taxonomia e filogenia de Selenastraceae (Blackman & Tansley)

A família Selenastraceae é composta de algas verdes cocóides, com células com aspecto fusiforme a cilíndrico, solitárias ou coloniais, cujo principal critério para sua definição é a típica citocinese para a liberação de autósporos. Entretanto, seus gêneros principais nem sempre foram classificados em Selenastraceae.

Blackman e Tansley estabeleceram em 1902 o conteúdo da família Selenastraceae, tendo esta sofrido alterações no decorrer do tempo. Por incluir os gêneros Selenastrum Reinsch e Scenedesmus Meyen, Scenedesmaceae Bohlin 1904 foi usada por algum tempo como sinônimo de Selenastraceae (Silva 1980). Todavia, West e Fritsch (1927) separaram claramente as duas famílias em Scenedesmaceae, sendo Scenedesmus o gênero-tipo, e Selenastraceae, com Selenastrum como gênero-tipo.

A partir do modo de reprodução, Brunnthaler (1915) citou os gêneros Ankistrodesmus Corda ex Korshikov e Selenastrum, com reprodução exclusiva por autosporia, quando dividiu a antiga ordem Protococcales em duas séries denominadas Autosporinae, com reprodução por autosporia, e Zoosporinae, com reprodução por zoósporos.

Korshikov (1953) estabeleceu a família Ankistrodesmaceae como sinônimo de Selenastraceae, incluindo nove gêneros, como Chlorolobion Korsikov, Ankistrodesmus, Nephroclamys (G.S.West) Korshikov e Kirchneriella Schmidle. Mais adiante, Bourrelly

(1972) inseriu os gêneros Ankistrodesmus, Monoraphidium Komárková-Legnerová, Podohedriella (Duringer) Hindák, Quadrigula Printz, Selenastrum, Chlorella, Raphidium Schroeder e Kirchneriella, na família Oocystaceae.

Posteriormente, os gêneros Ankistrodesmus, Monoraphidium, Podohedriella e Quadrigula e mais 12 gêneros foram colocados na família Chlorellaceae, sub-família

5 sistema de classificação de Brunnthaler (1915) (Comas, 1996, Hindák, 1984, 1988, 1990).

A divergência entre os autores no que diz respeito à classificação na antiga ordem Chloroccocales, da qual Selenastraceae fez parte, é responsável pelos vários sistemas de classificação propostos até hoje (Sant‟Anna 1984). Dependendo dos julgamentos dos autores, os gêneros são colocados no “complexo” de famílias

Selenastraceae/Chlorellaceae/Ankistrodesmaceae/Oocystaceae e, frequentemente, nem todas as obras específicas reconhecem todas as famílias deste “complexo”.

Na tentativa de estabelecer critérios morfológicos aplicáveis para Selenastraceae, Marvan et al. (1984) estudaram a morfologia de 18 gêneros, já classificados em Selenastraceae pelo menos alguma vez, por avaliações numéricas da morfologia e características ontogenéticas (formato celular ou das colônias, o arranjo dos autósporos dentro da célula mãe, a presença/ausência de mucilagem ou de incrustações na parede celular, e a presença, número e tipo de pirenóides) foram usados para a definição morfométrica e qualitativa dos gêneros. Como conclusão, os gêneros diferenciam-se uns dos outros por apenas um caráter acima citado, não apresentando definições precisas dentro do grupo.

6 morfologicamente semelhantes podem ser bem diferentes em termos moleculares e que cepas distintas morfologicamente podem ser muito semelhantes em termos do gene 18S rDNA. Ressalta-se que a maioria das espécies de Selenastraceae são descritas como cosmopolitas e nas mais diversas regiões climáticas: dos trópicos até próximo dos ciclos polares, o que significa que a prospecção em ambientes tropicais poderá originar resultados muito diferentes daqueles obtidos em regiões temperadas.

A ocorrência de diversidade críptica e classificações errôneas em nível de gênero, baseadas às vezes em apenas um caractere diacrítico de difícil definição em microscopia óptica, são recorrentes em Selenastraceae (Fawley et al. 2005). Isso ocorre

principalmente no “complexo” de famílias

Ankistrodesmaceae/Selenastraceae/Chlorellaceae/Oocystaceae, grupo reconhecido por ter taxonomia problemática, principalmente em espécies pertencentes aos gêneros Ankistrodesmus, Monoraphidium, Selenastrum e do complexo Kirchneriella-Pseudokirchneriella-Raphidocelis.

Com base na variabilidade encontrada na natureza, pode-se especular que devam existir centenas de taxons em Selenastraceae (Fawley et al. 2005), tendo em vista que trabalhos anteriores estudaram principalmente espécies isoladas de ambientes temperados do hemisfério norte. O conhecimento atual da diversidade específica e da ecologia de Selenastraceae é, ainda, muito pouco entendido mundialmente, embora esses organismos sejam considerados cosmopolitas e muito frequentes em amostras dos maios diversos corpos de água continentais (Krienitz et al. 2011).

7 que a maioria dos táxons podem pertencer a outros clados ou gêneros (Krienitz et al. 2011).

Chapman et al. (1998) dividiram a classe Chlorophyceae em dois clados: o primeiro inclui as ordens tradicionais (Chlorococcales, Volvocales e Chlorosarcinales) e o segundo clado inclui a ordem monofilética Sphaeropleales, o gênero Bracteacoccus e todas as clorofíceas que possuem autosporia. Uma associação próxima ocorre entre as clorofíceas autospóricas, Scenedesmus e Ankistrodesmus por exemplo, e zoospóricas, como Sphaeroplea Agardh e Neochloris Starr, com aparato flagelar diretamente oposto, pois há similaridade na estrutura celular e formas de crescimento cenobiais (Chapman et al.1998).

De acordo com Wolf et al. (2002) deve ser feita uma emenda para incluir diversas clorofíceas autospóricas que, presumivelmente, perderam a habilidade de reprodução por zoosporia e se encontram nas famílias Scenedesmaceae e Selenastraceae.

Estudos recentes (Krienitz et al. 2001, Fawley et al. 2005), realizados a partir da análise morfológica e filogenia por 18S rDNA, têm mostrado que algumas espécies dos gêneros Ankistrodesmus, Monoraphidium, Quadrigula, e Podohedriella estão bem definidos na família Selenastracae. Para Fawley et al. (2005), a utilização do 18S rDNA, por ser um gene muito conservado, provavelmente revelou apenas parte da diversidade real, o que sugere que o uso de marcadores moleculares que sofreram maior pressão evolutiva possam ser melhores marcadores filogenéticos. Entretanto, ambos os trabalhos acima citados não encontraram semelhanças quanto às espécies estudadas, o que mostra que a resolução para os gêneros e as espécies de Selenastraceae está ainda muito longe de ser alcançada.

8 variáveis do que o 18S rDNA e o aumento da riqueza de espécies estudada. Desta forma, a criação de uma base taxonômica robusta obtida com taxonomia tradicional, dados ecológicos, relações filogenéticas, dados quimiotaxonômicos e observações em cultivos seria um excelente ponto de partida.

Conceitos de espécie em algas verdes

O conceito biológico de espécie aceito amplamente pela comunidade científica é o proposto por Mayr (1948), onde a compatibilidade sexual é critério para a delimitação de espécie, não sendo aplicável a grupos que possuem reprodução assexuada ou cuja reprodução é desconhecida.

A abordagem filogenética com marcadores genéticos é aplicável nesses casos, desde que seja escolhida a região gênica e um marcador molecular apropriado (Bock 2010). Com base na filogenia, o uso de uma região conservada demais distinguirá menos espécies e caracteres morfológicos podem conflitar com a posição das espécies na árvore filogenética. Por outro lado, se uma região altamente variável é escolhida, a quantidade de espécies pode ser superestimada (Hoef-Emden 2007, Rindi et al. 2009).

O espaçador transcrito interno 2 (do inglês Internal Transcriber Spacer 2 - ITS2) faz parte do operon rRNA, localizado entre o 5.8S e 28S. As moléculas de rRNA funcionais são obtidas em todo um operon rRNA, que é transcrito como um único rRNA precursor, seguido de processos complexos de excisão de ambas as regiões ITS.

9 pareamento (por exemplo, G-C sofre mutações para A-U). A comparação de posições homólogas entre organismos diferentes, em busca de nucleotídeos não conservados, mas que sofreram co-evolução, pode ser revelada pela estabilidade e funcionalidade da estrutura secundária do RNA. A ocorrência de CBC em regiões conservadas do ITS2 coincide com a incompatibilidade sexual entre duas espécies (Coleman & Mai 1997, Mai & Coleman 1997, Coleman 2000, 2003, 2009, Amato et al. 2007). A presença de CBCs ou hemi-CBCs (apenas alterações unilaterais de bases) também é usada frequentemente para a delimitação de espécies em grupos cuja morfologia é de difícil resolução ou quando só se conhece a reprodução assexuada (Krienitz et al. 2004, Hoef-Emden, 2007).

Tem-se comprovado que o ITS2 é um marcador apropriado para o estudo filogenético de pequena escala entre espécies aparentadas, sendo comum o seu uso entre espécies dentro de um mesmo gênero (Coleman 2003, Coleman & Vacquier 2002, Coleman 2007, Young & Coleman, 2004, Schultz et al. 2005). As propriedades altamente divergentes e com rápida evolução legitimam o ITS2 para discriminar organismos estreitamente relacionados, que exibem sequências quase idênticas nos genes rRNA (Wolf et al. 2013).

A ordem Sphaeropleales apresenta hélices bem conservadas evolutivamente, preservando a estrutura do ITS2 e promovendo alusões para estudos taxonômicos mais amplos. Uma ramificação incomum da hélice 1 do ITS2 dentro dos gêneros Hydrodictyon (Hydrodyctiaceae), Desmodesmus e Scenedesmus (Scenedesmaceae) foi descrita por van Hannen et al. (2002), sendo estes gêneros intimamente relacionados com Selenastraceae.

10 rbcL (ribulose-1,5-bisfosfato, ou RuBisCO), cujos dados são desconhecidos para Selenastraceae e famílias relacionadas. Há décadas o gênero Ulva (Ulvophyceae, Ulvaceae) vem sendo amplamente estudado, utilizando também o rbcL para resolver problemas taxonômicos (Hayden & Waaland 2002, Hayden et al. 2003, Hayden & Waaland 2004, Loughnane et al. 2008). Estabelecido entre os grupos de plantas como DNA Barcode, o rbcL é considerado um marcador promissor (Hollingsworth et al. 2009) por causa de seu uso em estudos taxonômicos e filogenéticos em macroalgas verdes marinhas (Saunders & Kucera 2010). Inferência filogenética em algas verdes com base em rbcL está sendo amplamente utilizada principalmente por causa de suas variações e resolução em níveis mais baixos do que o 18S rDNA (Fucivoká et al. 2011).

Referências bibliográficas

Amato, A., W. H. Kooistra, J. H. L. Ghiron, D. G. Mann, T. Pröschold & M. Montresor, (2007). Reproductive isolation among sympatric cryptic species in marine diatoms. Protist 158(2):193-207.

Aslam, Z., W. Shin, M. K. Kim, W. T. Im & S. T. Lee, (2007). Marinichlorella kaistiae gen. et sp. nov.(Trebouxiophyceae, Chlorophyta) based on polyphasic taxonomy1. Journal of Phycology 43(3):576-584.

Blackman, F. & A. Tansley, (1902). A Revision of the Classification of the Green Algae (Continued) page 72). New Phytologist 1(4):89-96.

Blackman, F. F., (1900). The primitive algae and the flagellata. An account of modern work bearing on the evolution of the algae. Annals of Botany:647-688.

11 Bourrelly, P., (1972): Les Algues d'eau douce. Initiation à la Systématique: Tome I. Les

Algues vertes. Société Nouvelle des Éditions Boubée.

Brunnthaler, J., (1915). Protococcales in A. Pascher‟s die Susswasserflora Deutschlands, Osterrichs und der Schweiz, Hefts, Chlorophyceae 2. Vena. Chapman, R. L., M. A. Buchheim, C. F. Delwiche, T. Friedl, V. A. Huss, K. G. Karol,

L. A. Lewis, J. Manhart, R. M. McCourt & J. L. Olsen, (1998). Molecular systematics of the green algae Molecular systematics of plants II. Springer, 508-540.

Christensen, T. (1962). Algae. In: Bocher, T. W., Lange, W. & Sorensen, T. (Eds): Botanik, 2, Systematisk botanik. Munksgard, Copenhagen, Denmark, pp. 1-178.

Coleman, A. W., (2000). The significance of a coincidence between evolutionary landmarks found in mating affinity and a DNA sequence. Protist 151(1):1-9. Coleman, A. W., (2003). ITS2 is a double-edged tool for eukaryote evolutionary

comparisons. TRENDS in Genetics 19(7):370-375.

Coleman, A. W., (2007). Pan-eukaryote ITS2 homologies revealed by RNA secondary structure. Nucleic Acids Research 35(10):3322-3329.

Coleman, A. W., (2009). Is there a molecular key to the level of “biological species” in

eukaryotes? A DNA guide. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 50(1):197-203.

Coleman, A. W. & V. D. Vacquier, (2002). Exploring the phylogenetic utility of ITS sequences for animals: a test case for abalone (Haliotis). Journal of molecular evolution 54(2):246-257.

12 Darienko, T., L. Gustavs, O. Mudimu, C. R. Menendez, R. Schumann, U. Karsten, T. Friedl & T. Pröschold, (2010). Chloroidium, a common terrestrial coccoid green alga previously assigned to Chlorella (Trebouxiophyceae, Chlorophyta). European Journal of Phycology 45(1):79-95.

Ettl, H., (1981). Die neue Klasse Chlamydophyceae, eine natürliche Gruppe der Grünalgen (Chlorophyta)/The New Class Chlamydophyceae, a Natural Group of the Green Algae (Chlorophyta). Plant Systematics and Evolution:107-126. Ettl, H. & J. Komárek, (1982). Was versteht man unter dem Begriff coccale

Grünalgen?(Systematische Bemerkungen zu den Grünalgen II). Algological Studies/Archiv für Hydrobiologie, Supplement Volumes:345-374.

Fawley, M. W., M. L. Dean, S. K. Dimmer & K. P. Fawley, (2006). Evaluating the morphospecies concept in the Selenastraceae (Chlorophyceae, Chlorophyta) Journal of Phycology 42(1):142-154.

Fawley, M. W., Y. Yun & M. Qin, (2000). Phylogenetic analyses of 18S rDNA sequences reveal a new coccoid lineage of the Prasinophyceae (Chlorophyta). Journal of Phycology 36(2):387-393.

Friedl, T., (1997): The evolution of the green algae. Plant systems Evolution [Supplement] 11:87-101.

Fritsch, F., (1927). A treatise on the British freshwater algae in which are included all the pigmented protophyta hitherto found in Bri.

13 Hayden, H. S., J. Blomster, C. A. Maggs, P. C. Silva, M. J. Stanhope & J. R. Waaland, (2003). Linnaeus was right all along: Ulva and Enteromorpha are not distinct genera. European Journal of Phycology 38(3):277-294.

Hayden, H. S. & J. R. Waaland, (2004). A molecular systematic study of Ulva (Ulvaceae, Ulvales) from the northeast Pacific. Phycologia 43(4):364-382. Hindák, F. (ed) (1984). Studies on the chlorococcal algae (Chlorophyceae) III, Veda,

Bratislava.

Hindák, F. (ed) (1988). Studies on the chlorococcal algae (Chlorophyceae) IV., Veda, Bratislava.

Hindák, F. (ed) (1990). Studies on the chlorococcal algae (Chlorophyceae). V, Veda, Bratislava.

Hoef-Emden, K., (2007). Revision of the genus Cryptomonas (Cryptophyceae) II: incongruences between the classical morphospecies concept and molecular phylogeny in smaller pyrenoid-less cells. Phycologia 46(4):402-428.

14 Huss, V. A., C. Frank, E. C. Hartmann, M. Hirmer, A. Kloboucek, B. M. Seidel, P. Wenzeler & E. Kessler, (1999). Biochemical taxonomy and molecular phylogeny of the genus Chlorella sensu lato (Chlorophyta). Journal of Phycology 35(3):587-598.

Komárek, J. & B. Fott, (1983). Das Phytoplankton des Sübwassers. Systematik und Biologie. 7. Teil, 1. Hälfte. Chlorophyceae (Grünalgen) Ordnung: Chroococcales. E. Schweizerbart‟sche Verlagsbuchhandlung (Nägele u.

Obemiller), Stuttgart. 1043p.

Kornmann, P., (1973). Codiolophyceae, a new class of Chlorophyta. Helgoländer Wissenschaftliche Meeresuntersuchungen 25(1):1-13.

Korshikov, O., (1953). Viznachnik prisnovodnih vodorostey Ukrainskoy RSR. V Protococcineae Naukova dumka, Kiıv (in Ukrainian).

Krienitz, L., E. H. Hegewald, D. Hepperle, V. A. Huss, T. Rohr & M. Wolf, (2004). Phylogenetic relationship of Chlorella and Parachlorella gen. nov.(Chlorophyta, Trebouxiophyceae). Phycologia 43(5):529-542.

Krienitz, L., I. Ustinova, T. Friedl & V. A. Huss, (2001). Traditional generic concepts versus 18S rRNA gene phylogeny in the green algal family Selenastraceae (Chlorophyceae, Chlorophyta). Journal of Phycology 37(5):852-865.

Lewis, L. A. & R. M. McCourt, (2004). Green algae and the origin of land plants. American Journal of Botany 91(10):1535-1556.

15 Mai, J. C. & A. W. Coleman, (1997). The internal transcribed spacer 2 exhibits a common secondary structure in green algae and flowering plants. Journal of Molecular Evolution 44(3):258-271.

Marin, B. & M. Melkonian, (2010). Molecular phylogeny and classification of the Mamiellophyceae class. nov. (Chlorophyta) based on sequence comparisons of the nuclear-and plastid-encoded rRNA operons. Protist 161(2):304-336.

Marvan, P., J. Komárek & A. Comas, (1984). Weighting and scaling of features in numerical evaluation of coccal green algae (genera of the Selenastraceae). Algological Studies/Archiv für Hydrobiologie, Supplement Volumes:363-399. Mattox, K., (1984). Classification of the green algae: a concept based on comparative

cytology. Systematics of the green algae:29-72.

Mayr, E., (1947). The bearing of the new systematics on genetical problems; the nature of species. Advances in genetics 3(2):205-237.

Melkonian, M., (1989). Systematics and evolution of the algae Progress in botany. Springer, 214-245.

Neustupa, J., Y. Němcová, M. Eliáš & P. Škaloud, (2009). Kalinella bambusicola gen.

et sp. nov.(Trebouxiophyceae, Chlorophyta), a novel coccoid Chlorella‐like subaerial alga from Southeast Asia. Phycological Research 57(3):159-169. Pascher, A., (1918). Von einer allen Algenreihen gemeinsamen Entwicklungsregel. Pringsheim, E., (1963). Chlorophyllarme Algen I Chlamydomonas pallens nov. spec.

Archives of Microbiology 45(2):136-144.

16 Sant'Anna, C. L., (1984). Chlorococcales (Chlorophyceaea) do Estado de São Paulo,

Brasil. Bibliotheca Phycologica 67. J. Cramer, Berlin, 348.

Saunders, G. W. & H. Kucera, (2010). An evaluation of rbcL, tufA, UPA, LSU and ITS as DNA barcode markers for the marine green macroalgae. Cryptogamie Algologie 31(4):487-528.

Schultz, J., S. Maisel, D. Gerlach, T. Müller & M. Wolf, (2005). A common core of secondary structure of the internal transcribed spacer 2 (ITS2) throughout the Eukaryota. Rna 11(4):361-364.

Trainor, F., (1998). Biological aspects of Scenedesmus: phenotypic plasticity. Schweizerbart'sche Verlagsbuchhandlung, Stuttgart.

van den Hoek, C. & H. M. Jahns, (1978): Algen: Einführung in die Phykologie. Thieme. van den Hoek, C., W. Stam & J. Olsen, (1988). The emergence of a new chlorophytan system, and Dr. Kornmann's contribution thereto. Helgoländer Meeresuntersuchungen 42(3-4):339-383.

van den Hoek, C., D. Mann & H. M. Jahns, (1995): Algae: an introduction to phycology. Cambridge university press.

van Hannen, E., P. FinkGodhe & M. Lurling, (2002). A revised secondary structure model for the internal transcribed spacer 2 of the green algae Scenedesmus and Desmodesmus and its implication for the phylogeny of these algae. European

Journal of Phycology 37(2):203-208.

Wolf, M., M. Buchheim, E. Hegewald, L. Krienitz & D. Hepperle, (2002). Phylogenetic position of the Sphaeropleaceae (Chlorophyta). Plant Systematics and Evolution 230(3-4):161-171.

17 concept despite intragenomic variability in ITS2 sequences–a proof of concept. PloS one 8(6):e66726.

18

Hipóteses

A)O morfotipo Selenastrum tem origem polifilética.

As análises moleculares disponíveis na literatura sugerem a origem polifilética de alguns gêneros de Selenastraceae, como Selenastrum, gênero tipo da família, Ankistrodesmus, Monoraphidium e Kirchneriella.

B)Uma grande diversidade genética está escondida entre espécies morfológicas.

Espécies frequentes em corpos d‟água, como as pertencentes aos gêneros

Ankistrodesmus, Monoraphidium e Kirchneriella e Selenastrum, tem distribuição cosmopolita e ocupam diferentes habitats, segundo a literatura. Alguns autores acreditam que a diversidade genética de microalgas verdes é, por vezes, muito maior do que sua morfologia simples sugere. Estes complexos de espécies genéticas de diferentes gêneros, supostamente, teriam evoluído através de convergência morfológica e localizam-se em diferentes posições filogenéticas.

C)Os marcadores moleculares utilizados revelariam a diversidade genética de Selenastraceae.

19

Objetivos

Utilizando técnicas de taxonomia tradicional e biologia molecular para estudar a família Selenastraceae, pretendeu-se:

1) Identificar gêneros e espécies pertencentes à família Selenastraceae, grupo reconhecidamente problemático quanto à identificação, principalmente dos gêneros Ankistrodesmus, Monoraphidium, Selenastrum e do complexo Kirchneriella-Pseudokirchneriella-Kirchneria-Raphidocelis.

2) Avaliar os genes (18S rDNA, 5.8S e rbcL) e o espaçadores intergênicos (ITS1 e ITS2) como potenciais marcadores taxonômicos e moleculares para Selenastraceae, tentando elucidar a variação encontrada entre as espécies estudadas.

20 Capítulo 1:

21 1.1. ABSTRACT

The phylogeny of the family Selenastraceae was investigated by light microscopy, 18S rDNA, rbcL and ITS-2 analyses. Various morphological features traditionally used for species and genera identification were investigated. All selenastracean strains studied have naked pyrenoids within the chloroplast, except the genus Chlorolobion, which presented starch envelope. The molecular analyses showed that no morphological criterion considered so far is significant for the systematics of the Selenastraceae, but a set of features may be suitable to identify the genera Ankistrodesmus and Chlorolobion. Phylogenetic analyses showed the genera Monoraphidium, Kirchneriella and Selenastrum were not monophyletic and not distinguishable as separate genera, what led to the description of two new genera, Curvastrum gen. nov and Messastrum gen. nov.

22 1.2. INTRODUCTION

23 Since its description in 1903, the family Selenastraceae has passed by many taxonomic changes, being recognized as: Scenedesmaceae BOHLIN 1904, Selenastraceae WEST & FRITSCH 1927, Ankistrodesmacaeae KORSHIKOV 1953, Oocystaceae BOURRELLY 1972, Chlorellaceae – Ankistrodesmoidea KOMAREK & FOTT 1983. However, first studies in the SSU of the commonly observed genera in this family, e.g. Ankistrodesmus, Selenastrum, Monoraphidium, Quadrigula, Podohedriella and Kirchneriella, show that they form a monophyletic group within the Chlorophyceae

(FAWLEY et al. 2006; KRIENITZ et al. 2011; KRIENITZ et al. 2001), apart from other members of Scenedesmaceae (FAWLEY et al. 2006; KRIENITZ et al. 2001), Oocystaceae [which is now placed within the Class Trebouxiophyceae (FRIEDL 1995)] and Chlorellaceae (FRIEDL 1995; KRIENITZ et al. 2001). Since the onset of molecular phylogeny, several genera were excluded from the family due to their molecular traits, e.g., Closteriopsis was transferred to the Chlorellaceae and Hyloraphidium is in fact a fungus (LUO et al. 2010; USTINOVA et al. 2001).

Despite the monophyly of the family, the genera still need revision, since morphological features are usually not in accordance with molecular data (KRIENITZ et al. 2001; KRIENITZ et al. 2011). For example, defined genera cluster polyphyletic on different clades within the Selenastraceae, e.g. Selenastrum bibraianum (type species of Selenastrum), and Selenastrum gracile belong to different phylogenetic lineages based

on 18S rDNA phylogeny (FAWLEY et al. 2006; KRIENITZ et al. 2001) but no taxonomic changes were made in the genus, since the authors suggested further studies with the family to ensure these findings.

24 were focused on temperate northern hemisphere isolates, whereas the molecular diversity of tropical Selenastraceae remains unknown.

Phylogenetic inference in green algae is mainly based on 18S rDNA gene sequences (BOOTON et al. 1998; BUCHHEIM et al. 2001; FAWLEY et al. 2006; HEGEWALD & HANAGATA 2000; KRIENITZ et al. 2011; KRIENITZ et al. 2003; KRIENITZ et al. 2001; LEWIS 1997). Nevertheless, several studies have shown that the 18S rDNA is in some cases too conserved to distinguish between closely related genera and species (Luo et al. 2010). Different studies take a second marker into account as well, to gain a higher resolution (RINDI et al. 2011). The gene rbcL is being widely used mainly because of its higher variations and better resolution than the 18S rDNA at lower taxonomic levels

(FUČÍKOVÁ et al. 2011) and is also used as a DNA barcode in marine green macroalgae

(SAUNDERS & KUCERA). The ITS-2 has proven to be a suitable marker for small scale phylogenies and it is commonly applied among species within the same genus (BOCK et al. 2011b; COLEMAN 2003; COLEMAN 2007; COLEMAN & VACQUIER 2002; SCHULTZ et al. 2005; YOUNG & COLEMAN 2004) or for the resolution of closely related genera (LUO et al. 2010; LUO et al. 2011b). The highly divergent properties and the rapid evolution legitimate ITS-2 to discriminate closely related organisms, which exhibit nearly identical sequences in rRNA genes (WOLF et al. 2013).

25 1.3. MATERIAL AND METHODS

Algal cultures and microscopy.

Forty five Selenastraceae strains were investigated (Table 1). The algal cultures were obtained from Freshwater Microalgae Culture Collection from Universidade Federal de São Carlos (CCMA – UFSCar, WDCM 835) and from an author personal collection (CB strains). All the strains were grown in WC medium (GUILLARD & LORENZEN 1972) and maintained at of 23 ± 1 ºC, under photoperiod 12/12 hours light/dark, and luminous intensity of ~200 µmol/m2/s.

The whole life cycle of cultured strains were examined using an Axioplan 2 Imaging Zeiss or Nikon Eclipse E600 light microscope with differential interference contrast. Micrographs were taken using an AxioCam with software AxioVision 4.6 (Carl Zeiss Group, Oberkochen, Germany) and a Nikon digital camera DS-Fi1 with Nikon software NIS-Elements D (Nikon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The algal strains were identified according to the published keys (KORSHIKOV 1987; KOMÁREK & FOTT 1983; KOMÁRKOVÁ-LEGNEROVÁ 1969; COMAS 1996; HINDÁK 1977; HINDÁK 1980; HINDÁK 1984; HINDÁK 1988; HINDÁK 1990; SANT'ANNA 1984).

26 For SEM, a Critical Point Dryer (BAL-TEC 030, Germany) was used at 80-90 bars and 30-34 ºC .The samples were placed on a gold-palladium-coater (High Resolution Ion Beam Coater Model 681, Germany) and then 2 depositions of palladium were made (±1 kÅ). SEM images were taken with ESEM Quanta 400 FEG (FEI, The Netherlands).

TEM was performed according to KRIENITZ et al. (2011) with infiltration in epon. Thin sections were prepared on a Reichert UltraCut S (Reichert Inc., Depew, NY, USA), with no poststain and examined in a Hitachi S-4000 Scanning Electron Microscope (IMCES-Imaging Center Essen).

DNA extraction, PCR and sequencing.

For DNA extraction, the algae cultures were grown in the conditions described above for microscopy analyses. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 16.000 xg for 10 minutes and the pellet stored at -80°C until the next step. The cells were disrupted using glass beads (150-212 µm, Sigma-Aldrich), vortex briefly, and extracted using Invisorb® Spin Plant Mini (STRATEC Biomedical AG; Germany) or My-Budget DNA Mini Kit® (Bio-Budget Technologies GmbH; Krefeld; Germany).

27 unpublished), and Selenastraceae rbcL R 5‟ – RTTACCCCAWGGGTGHCCTA – 3‟). These proposed primers were used in association with the following published primers, rbcL1, rbcL1181, 1421 (NOZAKI et al. 1995), rbcL 320 (RINDI et al. 2008), rbcL RH1 (MANHART 1994), rbcL 1385 (MCCOURT et al. 2000), and rbcL ORB (PAZOUTOVA unpublished). For ITS-2 the primers used were 1420F (ROGERS et al. 2006), NS7m and LR1850 (AN et al. 1999) and ITS055R (MARIN et al. 1998). For more details about primers, see Table S3 (supplementary material). The PCR amplifications for rbcL gene were performed using the following reaction conditions: 95°C for 5 min followed by 25 cycles, each including 1 min at 95° C, 1 min at 52° C, and 2 min at 72° C with Taq DNA Polymerase QIAGEN® or DreamTaq DNA Polymerase Thermo Scientific®. 18S rDNA PCR amplifications were conducted according to KATANA et al. (2001) and KRIENITZ et al. (2011). ITS-2 PCR amplifications were performed according to BOCK et al. (2011). Each PCR product was electrophoresed in a 1% agarose gel, stained with ethidium bromide.

Purification of the PCR products was conducted using the polyethylene glycol protocol (PEG) according to ROSENTHAL et al. (1993). The PCR products were sequenced by Macrogen Inc. (ABI 3130-Genetic-Analyzer, Applied Biosystems GmbH, Darmstadt, Germany) with the same primers used for amplification. Part of the genomic DNA is stored at the Phycology Lab – UFSCar and Department of Biodiversity – University Duisburg-Essen.

28 accession numbers are reported in Table 1, including 29 reference sequences acquired from GenBank.

Phylogenetic analyses

29 (KRIENITZ et al. 2001) and Pediastrum (FUČÍKOVÁ et al. 2014) members were suitable as an outgroup for the phylogeny of Selenastraceae.

ITS-2 secondary structure prediction.

The ITS-2 model for Scenedesmus, proposed by van Hannen, (VAN HANNEN et al. 2002), was used as a template and adapted by hand. The secondary structure was obtained using the RNAfold Webserver (GRUBER et al. 2008) where the minimum free energy (MFE) of the secondary structure of single sequences and the equilibrium base-pairing probabilities were predicted. The RNA secondary structures were visualized with Pseudoviewer 3 (BYUN & HAN 2009).

1.4. RESULTS

Genera and species descriptions.

Messastrum gen. nov. T. S. GARCIA.

Green, planktonic microalgae. Narrow, fusiform to semilunate cells, ends gradually pointed, arcuate. Colonies with 2-4-8 or multi irregularly arranged cells, mostly with the convex side towards the center of the colony. One parietal chloroplast, containing a pyrenoid, no starch cover observed.

30 Genus differs from other genera in the Selenastraceae based on differences in 18S rDNA and rbcL gene sequences.

Typus generis: Messastrum gracile comb. nov.

Etymology: From the Latim mess (= mess) and astrum (= star).

Messastrum gracile comb. nov. (REINSCH) T. S., GARCIA.

Synonym: Ankistrodesmus gracilis (REINSCH) KORSHIKOV 1953, Selenastrum westii G.M.SMITH 1920, Dactylococcopsis pannonicus HORTOBÁGYI 1943.

Basyonym: Selenastrum gracile REINSCH 1866: 65, pl. IV: Fig. III.

Cells narrow, fusiform to semilunate, ends gradually pointed, arcuate. Planktonic, solitary or 2-4-8 or multi celled colonies with irregularly arranged cells, mostly with the convex sides towards the center of the colonies. Reproduction by autospore formation, where the sporangium gives rise to 2-4-8 young cells, with parallel or zigzag orientation. Pyrenoid without starch cover, observed just under TEM. One parietal chloroplast. Cell wall covered by a diffuse thin layer of mucilage on both colonies and free individuals. A diffuse thin layer of mucilage is often concentrated as a ring on the middle of the cells on both colonies and free individuals. Cells 19-55 x 1-6 µm, distance between the opposite cell ends 6-34 µm.

Holotype: Selenastrum gracile REINSCH 1866: 65, pl. IV: Fig. III.

Epitype (designated here): A formaldehyde fixed sample of strain CCMA-UFSCar 622 is deposited at the Botanical Institute at São Paulo, Brazil, under the designation SP 469319.

31 Etymology: The species epithet is based on a morphological feature, “thin, slender”,

kept on this nomenclatural change.

Notes: Epitype - isolated from a pond in Conchas, in the country side of the state of São Paulo, in August 2013. More strains were collected inside the state of São Paulo (CCMA-UFSCar 5 and CCMA-UFSCar 470 (For GPS see Table 1).

Curvastrum gen. nov. T. S., GARCIA.

Green, planktonic microalgae. Narrow, fusiform to semilunate cells, ends gradually pointed, arcuate. Colonies with 4 irregularly arranged cells. One parietal chloroplast, cointaining a pyrenoid without starch cover, observed just under TEM.

Asexual reproduction by autosporulation (four autospores per sporangium), sexual reproduction not known. Cells single or on 4-celled colony formation. Cells often single celled in culture. Cell wall covered by a difuse thin layer of mucilage on both colonies and free individuals. Genus morphologic similar to Messastrum, distinguishing for the numbers of cells on colony and 18S rDNA, ITS-2 rDNA and rbcL sequences

Typus generis: Curvastrum pantanale sp. nov.

Etymology: From the Latim curvus (= curved) and astrum , (= star).

Curvastrum pantanale sp. nov. T. S., GARCIA.

32 mucilage on both colonies and free individuals. Cells 8-21 x 1,9-3,5 µm, distance between the opposite cell ends: 4-14 µm.

Holotype: A formaldehydefixed sample of this strain is deposited at the Botanical Institute at São Paulo, Brazil, under the designation SP 469320.

Iconotype: our figure number 1.3-1.4.

Isotype: Material of the authentic strain CCMA-UFSCar 350, maintained at the Culture Collection of Freshwater Microalgae, Federal University of São Carlos, São Carlos, Brazil.

Type locality: Isolated from a water fountain used as a supply for animals on Pantanal (Table 1), a Brazilian wetland, in October 2011. GPS 19°17'59.0"S 55°47'45.0"W. Etymology: The species epithet was derived from the place of origin of the first isolate of this genus, “Pantanal”, which means “great Swamp”.

Notes: Also collected inside the state of São Paulo (CCMA-UFSCar 608).

Selenastrum bibraianum (REINSCH) KORSHIKOV 1953

Synonym: Ankistrodesmus bibraianus (REINSCH) KORSHIKOV 1953 Basyonym: Selenastrum bibraianum REINSCH 1866: 65, pl. IV: Fig. II.

33 Holotype: Selenastrum bibraianum REINSCH 1866: 65, pl. IV: Fig. II.

Epitype (designated here): A formaldehyde fixed sample of strain CCMA-UFSCar 47 is deposited at the Botanical Institute at São Paulo, Brazil, under the designation SP 469321.

Isotype: Material of the authentic strain CCMA-UFSCar 47 , maintained at the Culture Collection of Freshwater Microalgae, Federal University of São Carlos, São Carlos, Brazil.

Etymology: no reference.

Notes: Epitype - isolated from a reservoir in São Carlos (Represa do Monjolinho), in the country side of the state of São Paulo, in November 2008. More strains were collected inside the state of São Paulo (CCMA-UFSCar 125 and CCMA-UFSCar 630), two strains were isolated from Germany (CB 2009/39 and CB 2009/43) and one from Sweden (CB 2012/47) (Table 1).

Ankistrodesmus arcuatus KORSHIKOV 1953

Synonym: Monoraphidium arcuatum (KORSHIKOV) HINDÁK 1970: 24, Figs 19, 10, Ankistrodesmus pseudomirabilis KORSHIKOV 1953: 297, Fig. 258 a-f, Ankistrodesmus

sabrinensis BELCHER & SWALE 1962: 131, Fig. 1:H.

Basyonym: Ankistrodesmus arcuatus KORSHIKOV 1953: 296, Fig. 257a, b.

34 Dimensions: 26-60x0,8-4,4 µm, distance between the cell ends: 30 µm.

Holotype: Ankistrodesmus arcuatus KORSHIKOV 1953: 296, Fig. 257a, b.

Epitype (designated here): A formaldehyde fixed sample of strain CCMA-UFSCar 24 is deposited at the Botanical Institute at São Paulo, Brazil, under the designation SP 469322.

Isotype: Material of the authentic strain CCMA-UFSCar 24 (Fig. 1.5), maintained at the Culture Collection of Freshwater Microalgae, Federal University of São Carlos, São Carlos, Brazil.

Etymology: The species epithet is based on a morphological feature, “arched”, kept on

this nomenclatural change.

Note: According to the original diagnosis (KORSHIKOV 1953), the author adds a suggestion that the cells may belong to decomposed colonies of Messastrum gracile, differing only by the absence of mucus. Komárková-Legnerová (Komárková-Legnerová 1969) considered a possible colony formation and mucilage presence but did not make a nomenclatural recombination. Epitype: isolated from Broa Reservoir, Itirapina, in the country side of the state of São Paulo, in 1979 (Table 1).

Microscopy

This section is focused on morphological traits that conducted to species differentiation. Cells were examined for their cell shape and dimensions, autospore arrangement, pyrenoid presence or absence and colony formation, respecting the diacritical features of each species (for identification keys, see Material and methods). For a summary see Table 2.

Ankistrodesmus CORDA strains had fusiform and isopolar cells, with diameter of

35 in culture. Except for Ankistrodesmus sigmoides (RABENHORST) BRÜHL & BISWAS (CB 2009/9), which autospores were not observed, all the autospores were arranged in parallel. Mother cell wall remnants were cone-shaped. Ankistrodesmus spiralis (TURNER) LEMMERMANN (CB2012/29) had colonies with central twisted bundles, proper from this species. Mucilage was observed on the colonies but not on solitary cells.

Ankistrodesmus stipitatus (CHODAT) KOMÁRKOVÁ-LEGNEROVÁ (CCMA-UFSCar 277 and CCMA-(CCMA-UFSCar 278) were arranged with the cells frequently in parallel in free floating fascicular colonies. Some cells were attached to the walls of the glass tubes, producing basal mucilage on their ends. Autospores seemed to be attached to each other by the middle of the cell even before the mother cell rupture. Ankistrodesmus fusiformis CORDA (CB 2012/6CCMA-UFSCar 423, CCMA-UFSCar 611 and CCMA-UFSCar 593) presented cruciform or stellate colonies that were joined by a central mucilaginous area. Ankistrodesmus fasciculatus (LUNDBERG) KOMÁRKOVÁ-LEGNEROVÁ (CB 2012/3) presented 2-4 celled colonies connected to each other by their convex side, revealing a fasciculate shape, surrounded by a mucus layer. Ankistrodesmus sigmoides had sigmoid colony formation. Ankistrodesmus arcuatus

(KORSHIKOV) HINDÁK (CCMA-UFSCar 24) arcuated cells were arranged frequently in parallel in free floating fascicular colonies.

36 Raphidocelis microscopica (NYGAARD) MARVAN, KOMÁREK & COMAS (CB 2009/6, CB 2009/18 and CB 2012/39) formed colonies with mucilage and very small cells irregularly distributed on the colony.

All Kirchneriella SCHMIDLE species were similar in cell shape and in the colony morphology, varying on cell size and on the next exposed features. Kirchneriella pseudoaperta KOMÁREK (CCMA-UFSCar 346) presented visible pyrenoid under LM. Mucilage was exhibited when in colony, where mainly 4-celled colonies were observed. Some cells kept connected to each other before leaving the mother cell. Kirchneriella obesa (WEST) WEST & WEST (CCMA-UFSCar 345) presented mucilage when in colony

and solitary cells were bigger in size than the colony living ones. Kirchneriella aperta TEILING (CCMA-UFSCar 482) exhibited mucilage when in colony but not when in solitary cells. Kirchneriella lunaris (KIRCHNER) MÖBIUS (CCMA-UFSCar 443) had acute cell apex, with solitary cells bigger than the colonies one, always presenting pyrenoids. Kirchneriella contorta var. elegans (PLAYFAIR) KOMÁREK (CCMA-UFSCar 447) had circular, crescent-shaped to sigmoid cells with rounded cell apex. Kirchneriella irregularis (SMITH) KORSHIKOV (CCMA-UFSCar 348) cells were fusiform to strongly twisted, very small in size and without mucilage.

37 Monoraphidium indicum HINDÁK (CCMA-UFSCar 549) cells were c-shaped, with two autospores per sporangium and the mother cell wall was constantly found in culture.

Morphologically alike, genera Selenastrum (REINSCH) KORSHIKOV, Curvastrum T. S., GARCIA and Messastrum T. S., GARCIA have similar cell shape, 2-4-8 autospores per sporangium, mother cells ruptures in the meridian part with 4-8 autospores per sporangium. The three genera exhibited a great mucus layer both in colony and in solitary cells.

Selenastrum bibraianum (UFSCar 47, UFSCar 125, CCMA-UFSCar 630, CB 2009/39, CB 2009/41 and CB 2012/47) and Messastrum gracile (CCMA-UFSCar 5, CCMA-UFSCar 470, CCMA-UFSCar 622, CB 2009/3 and CB 2009/35) frequently showed big colonies with an arcuated chain of cells, regularly arranged in colony in the first and irregularly on the second species. Curvastrum pantanale T. S., GARCIA (CCMA-UFSCar 350 and CCMA-UFSCar 608) exhibited colonies with no more than 4 cells, irregularly arranged in colony (Fig.1.8a).

38 In our study, except for Chlorolobion braunii (Nägeli) Komárek, all Selenastracean taxa studied have naked pyrenoids (without starch envelopes), both observed by LM or TEM.

Phylogenetic analyses

Representatives of Selenastraceae are included in our rbcL (Fig. 1.6) and 18S rRNA gene sequence analyses (Fig. 1.7). Due to the low support of some internal branches in both phylogenies, the relationships among some lineages are not clearly resolved. However, some well-supported clades can be identified in both trees: (i) Selenastrum gracile, (ii) Selenastrum bibraianum, (iii) Raphidocelis, (iv) Curvastrum pantanale nov. gen. et. sp., (v) Kirchneriella, (vi) Chlorolobion (including Podohedriella falcata on the 18S rDNA tree), (vii) Ankistrodesmus, (viii) Monoraphidium. For Tetranephris, Quadrigula, Rhombocystis, Nephrochlamys, one clade for each genera on the 18S rDNA tree was obtained, with no rbcL sequences for them. The major clades resolved in our trees correspond well to the main genera traditionally included in Selenastraceae, that are, Ankistrodesmus and the distinguishable species of genus Selenastrum gracile and Selenastrum bibraianum (Reinsch) Korshikov. Due to the different number of strains inside 18S rDNA and rbcL trees, different results were obtained for some genera such as, Monoraphidium, Raphidocelis and Kirchneriella.

rbcL phylogenetic analyses (Fig.1.6) shows Selenastrum gracile (syn. Ankistrodesmus gracilis) strains are closely related to Ankistrodesmus (Ankistrodesmus clade). 18S rDNA phylogeny (Fig.1.7) reveals Ankistrodesmus distributed in two clades: Ankistrodesmus nannoselene Skuja (KF673373) (Kirchneriella I) and Ankistrodesmus fusiformis (type species, Ankistrodesmus I). Selenastrum gracile strains