2019/2020

Maria Ribeiro Pereira

Anorexia nervosa as a genetically determined condition

Mestrado Integrado em Medicina

Área: Ciências médicas e da saúde – Medicina Clínica

Tipologia: Monografia

Trabalho efetuado sob a Orientação de:

Doutora Isabel Maria Boavista Vieira Marques Brandão

Trabalho organizado de acordo com as normas da revista:

International Journal of Clinical Neurosciences and Mental Health

Maria Ribeiro Pereira

Anorexia nervosa as a genetically determined condition

UC Dissertação/Projeto (6º Ano) - DECLARAÇÃO DE INTEGRIDADE

Eu, Maria Ribeiro Pereira, abaixo assinado, nº mecanográfico 201403828, estudante do 6º ano do Ciclo de Estudos Integrado em Medicina, na Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto, declaro ter atuado com absoluta integridade na elaboração deste projeto de opção.

Neste sentido, confirmo que NÃO incorri em plágio (ato pelo qual um indivíduo, mesmo por omissão, assume a autoria de um determinado trabalho intelectual, ou partes dele). Mais declaro que todas as frases que retirei de trabalhos anteriores pertencentes a outros autores, foram referenciadas, ou redigidas com novas palavras, tendo colocado, neste caso, a citação da fonte bibliográfica.

Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto, 12/04/2020

UC Dissertação/Projeto (6º Ano) – DECLARAÇÃO DE REPRODUÇÃO

NOME

Maria Ribeiro Pereira

NÚMERO DE ESTUDANTE E-MAIL

201403828 mariaribpereira@gmail.com

DESIGNAÇÃO DA ÁREA DO PROJECTO

Ciências médicas e da saúde – Medicina Clínica

TÍTULO DISSERTAÇÃO/MONOGRAFIA (riscar o que não interessa) Anorexia nervosa as a genetically determined condition

ORIENTADOR

Isabel Maria Boavista Vieira Marques Brandão

COORIENTADOR (se aplicável)

ASSINALE APENAS UMA DAS OPÇÕES:

É AUTORIZADA A REPRODUÇÃO INTEGRAL DESTE TRABALHO APENAS PARA EFEITOS DE INVESTIGAÇÃO, MEDIANTE DECLARAÇÃO ESCRITA DO INTERESSADO, QUE A TAL SE COMPROMETE.

É AUTORIZADA A REPRODUÇÃO PARCIAL DESTE TRABALHO (INDICAR, CASO TAL SEJA NECESSÁRIO, Nº MÁXIMO DE PÁGINAS, ILUSTRAÇÕES, GRÁFICOS, ETC.) APENAS PARA EFEITOS DE INVESTIGAÇÃO, MEDIANTE DECLARAÇÃO ESCRITA DO INTERESSADO, QUE A TAL SE COMPROMETE.

DE ACORDO COM A LEGISLAÇÃO EM VIGOR, (INDICAR, CASO TAL SEJA NECESSÁRIO, Nº MÁXIMO DE PÁGINAS, ILUSTRAÇÕES, GRÁFICOS, ETC.) NÃO É PERMITIDA A REPRODUÇÃO DE QUALQUER PARTE DESTE TRABALHO.

Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto, 12/04/2020

Anorexia nervosa as a genetically determined condition

1

2

Abstract

3

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a psychiatric condition classically associated with an

4

extremely low body weight, a constant desire to be thin, with restriction of food intake

5

and a distorted self-perceived body image. This condition is potentially fatal and there

6

is still a lack of effective treatment options. In order to overcome this problem, the

7

scientific community is being encouraged to try to move this field into personalized

8

medicine. This can be achieved by deeply understanding the genetic and metabolic

9

pathways that contribute to the etiology of this disorder. Since the last century, there

10

has been evidence from twin and family studies supporting the existence of a genetic

11

basis for AN. In the past few years, the genetic investigation has entered a very precise

12

level, revealing nine genome-wide significant loci as well as significant genetic

13

correlations between AN, metabolic traits and psychiatric phenotypes. In this review,

14

we will summarize the most important findings on this field.

15

16

Keywords: anorexia nervosa; eating disorders; genetics; heritability

Introduction

18

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

(DSM-19

5), anorexia nervosa (AN) is a complex, severe and potentially life-threatening

20

condition and it can be categorized into two distinct subtypes, the restricting subtype

21

and the binge-eating subtype. [1]

22

AN is far more common in young adult or adolescent females than males [1-3]

23

and the onset of the disease is frequently correlated with a stressful experience. [1]

24

There is often delusional thinking and no insight about the seriousness of the

25

malnourished status, which often leads to several physiological disturbances, including

26

amenorrhea. [1, 4] These patients additionally present with other psychiatric traits, such

27

as depressive, obsessive-compulsive, obstinate thinking, and overly inhibited emotional

28

expression. [1, 5]

29

AN is still a widely misunderstood disorder since there is a noticeable

30

heterogeneity regarding the treatment response, generating a global concern. [6]

31

Pharmacotherapy has a secondary role in the treatment of eating disorders and it

32

should not be considered as a unique intervention. [7] Mortality is higher in AN than in

33

any other psychiatric disorder and the outcome is still unacceptably poor. The majority

34

of patients develop a relapsing course of the disease and only 25-30% fully recover. [8]

35

Most psychiatric disorders are known for having a very complex etiology,

36

including genetic, environmental and social factors. AN is no exception to this and it is

37

a very particular disease with characteristics that cannot be generalized for other types

38

of eating disorders. [9, 10] It is known that there is an increased risk of AN among

first-39

degree relatives of individuals with the disorder. However, until recently, there was not

40

enough evidence to show a clear genetic background of AN. This review aims to

41

provide the readers with an overview of the most relevant historical genetic findings in

42

anorexia nervosa, the most effective methods of genetic analysis as well as the most

43

recent and important discoveries on this matter and its possible clinical pertinence.

44

Methods

46

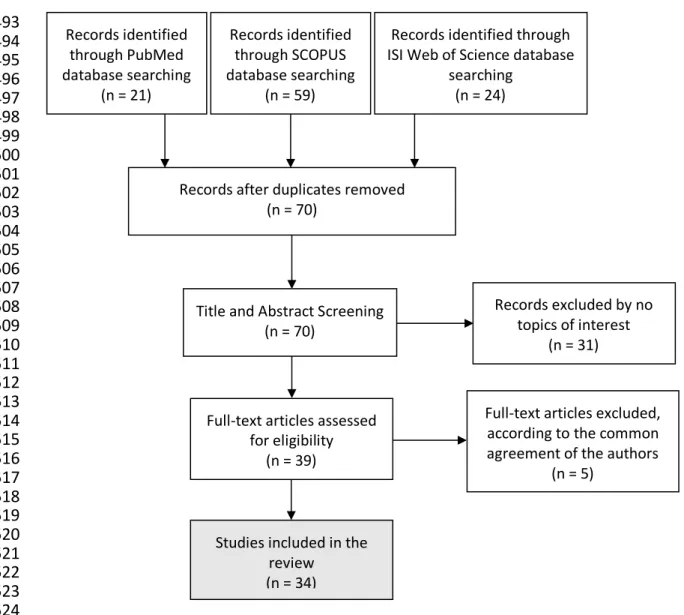

A literature search was made on PubMed using the query " "Anorexia

47

Nervosa/genetics"[Mesh] ", on SCOPUS using the query "KEY ( "Anorexia

48

Nervosa" AND "genetics" )" and on ISI Web of Science using the query

49

"TOPIC:(genetics) AND TOPIC: ("Anorexia Nervosa")". In this search, only articles

50

published during 2018 and 2019 were included. 21 results were found from the

51

PubMed data basis, 59 results from the SCOPUS data basis and 24 results from the

52

ISI Web of Science data basis, meaning a total of 104 results. Among these, 34

53

duplicates were found. After reading all the titles and abstracts from the 70 remaining

54

articles, 39 articles were considered to be the most relevant because of their

55

contribution to the subject. After full-text assessment for eligibility, 5 articles were

56

excluded by common agreement of the authors. A flow chart representing the methods

57

used is shown in figure 1.

58

59

Discussion

60

Historical background of Anorexia Nervosa

61

There is an intriguing general conception that AN is quite a recent social and

62

cultural phenomenon linked to the obsession with body image and the constant

63

promotion of slenderness amongst adolescent girls nowadays. [11] Nevertheless, this

64

condition is not believed to be that recent since, in 1983, Skrabanek summarized the

65

most important periods in the history of AN until then. [12]

66

AN is first described between the 5th and 13th centuries in theological literature

67

and it is interpreted as a "supernatural manifestation". Between the 16th and 18th

68

centuries, it was still associated with religion and beliefs, since medical descriptions

69

insisted on a phenomenon called "anorexia mirabilis" or "inedia prodigiosa", which

70

would be interpreted as an ability to perform self-discipline as a path to God. [12]

71

The first clinical report of AN as "a form of hypochondriacal delirium occurring

72

consecutive to dyspepsia and characterized by refusal of food" was only presented in

73

the 19th century by a French psychiatrist. [13]

74

Until the beginning of the 20th century, AN was believed to be a purely

75

psychiatric disorder and its potential biological and physiological mechanisms were not

76

being considered. The initial studies were mainly candidate gene analysis and provided

77

inconsistent and non-replicable results. [9]

78

In the 1960s, the advancement of genetic investigation mirrored the evolution of

79

technology. [14] Due to advances in human genetics investigations, metabolic and

80

neuroendocrine influences, as well as their genetic basis, are starting to be considered

81

as possible intermediaries of the abnormal reward pathway that appears to be seen in

82

AN patients, allowing a potential adjustment on the disorder’s etiology as we know it.

83

[11, 15]

84

Nowadays, due to the recent large scale successful studies we reviewed in this

85

paper, AN is considered a multifactorial psychiatric disorder which has several risk

86

factors, including genetic variations and its consequent metabolic impact, as well as

87

internal and external environmental factors.

88

89

Why do Genetic Research on Psychiatric disorders?

90

Some critics have reported that the findings on genetic variations of psychiatric

91

disorders are meaningless and will not have relevant implications on therapy. The

92

authors consider that there should not be put so much effort and resources into

93

something that constantly produces results with lack of clinical interest. [16]

94

However, medical research for eating disorders is still considered to be

95

underfunded when taking in consideration the advantages it brings to global disability

96

adjusted life-years. [17] There is a need to decipher the basic mechanisms underlying

97

these complex illnesses. [18] The main goal of genetic research on psychiatric

98

disorders is to provide clinically useful information in the future, to develop new

99

preventive strategies, to potentially guide new drugs development and to identify the

100

ones at risk of having a poor outcome, in order to provide personalized medical care.

101

[18]

102

103

Genetic Evidence on Anorexia Nervosa

104

Heritability is defined as the percentage of phenotypic variance due to

105

hereditary factors only. [18] Family and twins studies were among the first lines of

106

evidence confirming an increased genetic risk for AN, estimating heritability at

40%-107

60%. They still are the ones having the most replicable results among all genetic

108

studies on eating disorders. [19, 20] The consistency of this results has encouraged the

109

investment of the scientific community into studying the genetics of AN. [6]

110

Once we entered the era of the molecular genetics, a constant effort was made

111

to find significant results on this subject. However, the initial studies that were

112

developed did provide very disappointing results, examining only a few markers and

113

having very small samples. [9, 21, 22] The studies made on the epigenetics of eating

114

disorders were mostly investigating methylation patterns at candidate genes on very

115

small samples and also provided inconclusive results. [23]

116

Animal models have a big role on studying some metabolic pathways. However,

117

in AN they appear to be inadequate to replicate the human food intake and reward

118

process since it is not possible to reproduce the complex behavioral aspects and life

119

events that humans experience and have such a big role in the establishment of AN.

120

[24]

121

During the past decade, we have witnessed notable advances on the genetics

122

of psychiatric disorders and have been gifted with a virtual avalanche of data on the

123

human genome. It is now known that the genetic architecture of multiple psychiatric

124

disorders often overlaps. [14]

125

Evidence indicates that there may be an immense amount of genes contributing

126

to the increased risk, each one having a minor effect. [9, 19, 21, 25] This partly

127

explains the failure of the linkage and candidate gene studies, since the effects of each

128

genetic variant alone are probably too weak to be detected by those methods.

129

We now understand that it is essential to define the biology of the feeding

130

dysregulation process. [26] Multiple small studies focused on those pathways.

131

Serotonin is known for having a major role in appetite regulation. This led to the

132

development of studies testing if polymorphisms of the gene coding for the serotonin

133

receptors had any influence on the onset of AN. The 5-HT2A receptor coding gene had

134

some promising results linking its expression not only to AN, but also to

obsessive-135

compulsive disorder. [27, 28] Unfortunately, authors were unable to replicate those

136

results in posterior investigations. [27]

137

The dysregulation of the human neuronatin gene (NNAT) appears to have an

138

impact in multiple metabolic ways, including insulin secretion and energy homeostasis.

139

Lombardi et al. reported multiple variants of the NNAT to be associated with

140

susceptibility for eating disorders. However, this is a finding from a very small sample

141

study and it has not been replicated. [29]

142

There were also some authors trying to find a genetic correlation between the

143

brain volume and AN. Walton et al. reported weak evidence for an association between

144

common genetic variants linked to subcortical brain volumes and those variants linked

145

to AN. [30]

146

Even though we mainly look at gene alterations trying to find a cause for the

147

illness, it is also important to consider the possibility of the gene expression to be

148

altered due to the malnourished status that comes with AN. [31, 32] There is evidence

149

that an early onset of AN and a longer period with the disease can result in methylation

150

of gene pathways liked to anxiety, social awareness and even serotonin receptors. [33]

151

152

153

154

Novel methods to detect genetic correlation: Genome-wide Association Study and

155

Polygenic Risk Score

156

A brief explanation of how the genetic analysis is currently being made is

157

important to understand the latest results summarized in this review.

158

There are millions of common genetic variants identified in the human genome.

159

These variations are present in more than 1% of the population and the most common

160

are single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), where there is a single nucleotide

161

substitution at a specific location. [18]

162

We will now briefly define two major concepts in this field: Genome-wide

163

Association Study and Polygenic Risk Score.

164

A Genome-wide Association Study (GWAS) is an observational study that

165

typically focuses on trying to make an association between SNPs and a specific trait or

166

disease. GWAS is primarily focused on detecting common genetic variations, that

167

individually confer a very small risk but when added together may be responsible for a

168

considerable portion of the disease’s heritability. [9] A GWAS compares cases and

169

controls, similarly to the candidate-gene association studies. However, they do it using

170

a hypothesis-free approach and, therefore, not limiting the amount of information we

171

can obtain from a study. [21]

172

On the other side, a Polygenic Risk Score (PRS) is a statistical technique that

173

aggregates effects of variants across the genome to estimate heritability, to infer

174

genetic overlap between traits and to predict phenotypes based on a genetic profile.

175

[16] According to Bogdan R. et. al, the PRSs shouldn’t yet be interpreted as diagnostic

176

tools, but as simple predictors of risk. [16]

177

Since the GWAS are often used to calculate PRS, we can infer that as GWAS

178

sample sizes get larger and better described, PRSs are likely to become more precise

179

and, therefore, have a very important role in the future of personalized medicine.

180

181

182

AN samples and international cooperation

183

Since the genetic architecture of the psychiatric disorders appears to be so

184

complex, large samples of cases and controls were gathered in order to perform

185

validated analysis through GWAS. This was achieved due to the existence of two main

186

data basis, one developed by the Eating Disorders Working Group of the Psychiatric

187

Genomics Consortium (PGC-ED) and, more recently, the Anorexia Nervosa Genetics

188

Initiative (ANGI).

189

ANGI is an international collaboration that was developed because there was a

190

need for a bigger sample size than the one provided previously by the PGC-ED. ANGI

191

recruited over 13,000 individuals from the United States of America, Australia, New

192

Zealand, Sweden and Denmark, making it the largest sample of AN cases and controls

193

and the most rigorous genetic research on eating disorders ever made. [21, 34] The

194

recruitment was made via national registers, treatment centers and social media. Each

195

participant was submitted to a questionnaire and provided either peripheral blood or

196

saliva samples, which were then genotyped. ANGI has the goal to globally provide

197

validated and easy access information to encourage the development of more studies

198

on this subject. [34]

199

200

Genome-wide significant loci

201

GWAS has been used since 2005 and it brought a revolutionary vision on how

202

to study AN, since it apparently does not follow the principles of the Mendelian pattern

203

of inheritance. Since then, multiple GWASs about AN were developed. However, only

204

two of them provided genome-wide significant results. [21]

205

The first significant locus to be identified in AN via GWAS was reported by

206

Duncan et al. in 2017 in a study that included 3495 cases and 10982 controls. This is a

207

broad and multigenic locus, located on chromosome 12, in a region that had been

208

previously studied by its relation to autoimmune disorder and type 1 diabetes. This

209

study also reported significant positive and negative genetic correlations between AN

210

and other phenotypes, such as other psychiatric disorders and multiple metabolic traits,

211

summarized on table 2. [6, 35]

212

In 2019, even bigger advances on the knowledge of genetic architecture of the

213

AN were made. Watson et al. developed the biggest GWAS ever made on this subject,

214

combined both the PGC-ED and ANGI samples, making a total of 16 992 AN cases

215

and 55 525 controls, the largest sample ever studied. [36] This study provided robust

216

significant findings, having identified eight independent genome-wide significant loci,

217

listed on table 1, and multiple genetic correlations between anorexia nervosa and other

218

phenotypes, listed on table 2. [6, 36]

219

220

From GWAS to genetic correlations to multiple traits

221

The two studies mentioned above provided very comparable information about

222

the significant positive and negative genetic correlations to several traits, as we can

223

see on table 2.

224

The significant positive genetic correlation of AN with neuroticism and other

225

psychiatric traits and disorders is supported by epidemiological evidence of AN patients

226

often presenting other psychiatric traits. This correlation reinforces that there is a

227

shared genetic risk among several psychiatric disorders. [35, 36] Additionally, some of

228

this personality traits can be present before the onset of AN and, therefore, signal the

229

individuals who are at higher risk of developing it. [37]

230

Both studies reported a significant positive genetic correlation between AN and

231

education factors, such as the number of education years and the attendance to

232

college. With that in mind, we could look at this as an effect of a higher pressure for

233

academic success in highly educated families, resulting in increased anxiety levels that

234

could be associated to the onset of AN. However, these results are now revealing that

235

there is also a genetic influence for this linkage. [35, 36]

236

Regarding the metabolic phenotypes, we can group the findings into two distinct

237

groups. The “favorable” phenotypes, that include HDL cholesterol, have a significant

238

positive correlation to AN, as opposed to the “unfavorable” phenotypes, that include

239

insulin and glucose levels, and have a significant negative genetic correlation.

240

Finally, the anthropometric measures, such as extreme body mass index (BMI),

241

hip and waist circumference and body fat percentage, have a significant negative

242

genetic correlation to AN. This data could be the first step to a better understanding of

243

the shared biological mechanisms of extreme weight conditions. The same genetic

244

factors influencing normal BMI, body shape and composition variations can also be

245

responsible by the dysregulation of this measures in AN and obesity. [38, 39]

246

247

Does the in utero environment influence AN liability?

248

Placenta plays a central part when modeling the environment in which the fetus

249

is developing. Using an activity-based anorexia (ABA) rat model, Schroeder et al.

250

successfully demonstrated, for the first time, a possible mechanism of ABA in utero

251

programming. This mechanism could be explained by the alterations of placental gene

252

expression, such as placental miR-340 methylation, when submitted to stress. It is well

253

known that maternal stress during pregnancy can lead to a series of negative

254

consequences for the baby. Controversially, they reported that chronic exposure to

pre-255

natal stress can result in a resistance mechanism for the fetus, since the susceptibility

256

to AN seems to be downregulated by the placental miR-340 methylation. [40]

257

258

Sex differences – could genetics play a role?

259

It is well known that AN is around nine times more frequent in female than in

260

males [3] and, even though the environmental factors and the body image concerns

261

are more propitious for women to develop this kind of disorder, the biological cause for

262

such an evident difference is yet to be found. There are reports of subtle sex

263

differences on signs and symptoms presentation of eating disorders as well as

264

differences on their motivations for the weight loss. Even though some features are still

265

unclear, males appear to engage more on physical activity as a compensatory behavior

266

and they seem to be more focused on their muscle definition as opposed to the

267

females who mainly report the desire of thinness. [41]

268

Hubel et al. extended the research on the GWAS performed by Duncan et al.

269

and Watson et al. and tried to find a connection between the sex specific genomic

270

effects on body fat percentage (BF%) and AN. This investigation showed us that

271

female-specific genomic effects on BF% is significantly greater than the one observed

272

in males. This data suggests that there might be a specific group of genetic variations

273

that are differentially active in females and can contribute to the AN susceptibility. [35,

274

36, 42]

275

Since the onset of puberty apparently increases the genetic risk of developing

276

eating disorders, we understand that sex hormones can possibly have an important

277

role here. [41] This increase is more preeminent in females, and it is independent from

278

the environmental factors, raising the possible role of estrogen in activating or

279

modulating the genetic risk. [41, 43]

280

Neurotensin is a peptide discovered in the human brain over forty years ago

281

and it is known to be linked to the regulation of body temperature, locomotor activity,

282

metabolic rate and feeding rate. Schroeder et al., reported that females have four times

283

more neurotensin-expressing cells in certain parts of the brain comparing to males.

284

Estrogen modulates the expression of these cells, since the quantity of neurotensin

285

expressing cells vary according to estrogen levels during the menstrual cycle. This

286

means that the roles of those two systems can be intertwined, contributing to a bigger

287

liability for AN in females and supports the importance of future investigation on how

288

the estrogen level impacts the development of AN. [26]

289

There is also the possibility that some Y chromosome gene expressions could

290

have a protective effect against AN. [22] However, most of the genetic studies

291

performed did not have access to the information of the sex chromosomes, which

292

would be essential to include in future investigations. [42]

293

Evidence shows that it could be much easier to access the influence of genetics

294

in AN in a sample of male individuals. In this group, the environment appears to have a

295

smaller influence on AN development. Taking this into account, we can suppose that a

296

stronger genetic influence can be necessary for the onset of AN in males. [44]

297

However, due to the low prevalence of this condition in males and the small size

298

samples, it was not possible to perform a robust investigation until now. [45]

299

300

Future perspectives

301

Even though the future on this area seems very promising, in a short period of

302

time, it would only be reasonable to expect this data to help a better understanding of

303

familiar risk. [46] Imprecise interpretations and overly optimistic report could lead to

304

distortion of results and inappropriate investments. [18]

305

In the context of psychiatric disorders, where bad adherence to treatment due

306

to lack of insight is often a problem, it would probably be useful to provide the patient

307

and the people around them some explicit medical data, for example, the identification

308

of genetic variations known to be related to the condition.

309

It is probably too early to assume that these new discoveries would now be able

310

to guide us, for example, on how to choose the best medication for each patient. [46]

311

However, giving the reconceptualization of AN not only as a psychiatric disorder, but

312

also as a metabolic and immune related condition [35, 36], we can expect future

313

pharmacological agents to act primarily in these systems. [47]

314

In the future, genetic studies comparing the patients who experience relapse

315

after treatment to those who maintain the weight gained during treatment, could be an

316

important source of information and could lead us to an early identification of the most

317

treatment resistant cases by characterizing biomarkers of diagnosis and prognosis. [6,

318

48] Another important relation to be investigated in the future is the possible genetic

319

and metabolic shared risk factors between AN and suicidality in order to work towards

320

the prevention of this tragic outcome. [49]

321

322

Conclusion

323

Over the past decade, we started to comprehend that psychiatric disorders are

324

polygenic and may have the contribution of hundreds or thousands of genetic

325

variations, each having a small effect. [9, 19, 21, 25] We understand that the external

326

environment triggers cannot be ignored since this disorder has an extremely high social

327

burden, but we have no doubt that there is an interplay between genetics, the brain and

328

metabolism supporting the etiological mechanisms of AN.

329

It is challenging to extract information for our understanding on pathophysiology

330

from the results we have so far, but we know that this is a very promising area of

331

research. We need to have a deeply understanding of the different phenotypes existent

332

in this illness in order to be able to connect gene expression to behavior alterations in

333

the future. [14]

334

This is a disorder for which we still do not have very effective treatment options.

335

Therefore, an early identification of the patients suffering from AN could allow a more

336

successful medical intervention. Also, given the larger brain plasticity in younger

337

patients, an early treatment may be linked to minimize the neurocognitive damages

338

that can be provoked by AN. [50]

339

The genetic studies on AN have some important limitations that need to be

340

overcome. Although the sample size is now growing due to the international

341

collaborations mentioned above, the question of how big is big enough is still pertinent

342

to be discussed. [18] Furthermore, the investigations developed until now, include

343

mostly female populations of European ancestry and the male samples are still not

344

adequate to test male-specific genetic variations. The same problem exists for

345

individuals of other ancestral backgrounds. [6]

346

The most promising type of research studies seems to be the GWAS, since the

347

two analyzed in this review provided the strongest evidence ever found on the genetics

348

of AN. There are, until now, nine genome-wide significant loci identified in AN. [35, 36]

349

Taking this into account, the scientific community is now being encouraged to gather

350

even larger samples, to develop new GWASs to try to replicate previous results and

351

find new significant loci.

352

References

353

1.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental

354

disorders. 5th ed2013.

355

2.

Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG, Jr., Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of

356

eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry.

357

2007;61(3):348-58.

358

3.

Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Tozzi F, Furberg H, Lichtenstein P, Pedersen NL.

359

Prevalence, heritability, and prospective risk factors for anorexia nervosa. Arch Gen

360

Psychiatry. 2006;63(3):305-12.

361

4.

Behar R, Arancibia M, Gaete MI, Silva H, Meza-Concha N. The delusional

362

dimension of anorexia nervosa: Phenomenological, neurobiological and clinical

363

perspectives. Revista de Psiquiatria Clinica. 2018;45(1):15-21.

364

5.

Lee PH, Anttila V, Won H, Feng YCA, Rosenthal J, Zhu Z, et al. Genomic

365

Relationships, Novel Loci, and Pleiotropic Mechanisms across Eight Psychiatric

366

Disorders. Cell. 2019;179(7):1469-82.e11.

367

6.

Bulik CM, Flatt R, Abbaspour A, Carroll I. Reconceptualizing anorexia nervosa.

368

Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2019;73(9):518-25.

369

7.

Zipfel S, Schmidt U. Psychobiology of eating disorders – A gateway to precision

370

medicine. Current Neuropharmacology. 2018;16(8):1100-1.

371

8.

Bulik CM, Blake L, Austin J. Genetics of Eating Disorders What the Clinician

372

Needs to Know. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2019;42(1):59-+.

373

9.

Breithaupt L, Hübel C, Bulik CM. Updates on genome-wide association findings

374

in eating disorders and future application to precision medicine. Current

375

Neuropharmacology. 2018;16(8):1102-10.

376

10.

Dinkler L, Taylor MJ, Råstam M, Hadjikhani N, Bulik CM, Lichtenstein P, et al.

377

Association of etiological factors across the extreme end and continuous variation in

378

disordered eating in female Swedish twins. Psychological Medicine. 2019.

379

11.

Duriez P, Ramoz N, Gorwood P, Viltart O, Tolle V. A Metabolic Perspective on

380

Reward Abnormalities in Anorexia Nervosa. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism.

381

2019;30(12):915-28.

382

12.

Skrabanek P. Notes towards the history of anorexia nervosa. Janus.

1983;70(1-383

2):109-28.

384

13.

Marcé L-V. Note sur une forme de délire hypocondriaque consécutive aux

385

dyspepsies et caractérisée principalement par le refus d'aliment. Ann Med-Psychol.

386

1860;6:15-28.

387

14.

Sullivan PF, Geschwind DH. Defining the Genetic, Genomic, Cellular, and

388

Diagnostic Architectures of Psychiatric Disorders. Cell. 2019;177(1):162-83.

389

15.

Gorwood P, Blanchet-Collet C, Chartrel N, Duclos J, Dechelotte P, Hanachi M, et

390

al. New Insights in Anorexia Nervosa. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:256.

391

16.

Bogdan R, Baranger DAA, Agrawal A. Polygenic Risk Scores in Clinical

392

Psychology: Bridging Genomic Risk to Individual Differences. Annual Review of Clinical

393

Psychology: Annual Reviews Inc.; 2018. p. 119-57.

394

17.

Murray SB, Pila E, Griffiths S, Le Grange D. When illness severity and research

395

dollars do not align: are we overlooking eating disorders? World Psychiatry.

396

2017;16(3):321-.

397

18.

Hubel C, Leppa V, Breen G, Bulik CM. Rigor and reproducibility in genetic

398

research on eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2018;51(7):593-607.

399

19.

Bulik CM, Kleiman SC, Yilmaz Z. Genetic epidemiology of eating disorders. Curr

400

Opin Psychiatry. 2016;29(6):383-8.

401

20.

Yilmaz Z, Hardaway JA, Bulik CM. Genetics and Epigenetics of Eating Disorders.

402

Adv Genomics Genet. 2015;5:131-50.

403

21.

Himmerich H, Bentley J, Kan C, Treasure J. Genetic risk factors for eating

404

disorders: an update and insights into pathophysiology. Therapeutic Advances in

405

Psychopharmacology. 2019;9.

406

22.

Mayhew AJ, Pigeyre M, Couturier J, Meyre D. An Evolutionary Genetic

407

Perspective of Eating Disorders. Neuroendocrinology. 2018;106(3):292-306.

408

23.

Subramanian S, Braun PR, Han S, Potash JB. Investigation of differential HDAC4

409

methylation patterns in eating disorders. Psychiatr Genet. 2018;28(1):12-5.

410

24.

Maussion G, Demirova I, Gorwood P, Ramoz N. Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells;

411

New Tools for Investigating Molecular Mechanisms in Anorexia Nervosa. Frontiers in

412

Nutrition. 2019;6.

413

25.

Smoller JW, Andreassen OA, Edenberg HJ, Faraone SV, Glatt SJ, Kendler KS.

414

Psychiatric genetics and the structure of psychopathology. Molecular Psychiatry.

415

2019;24(3):409-20.

416

26.

Schroeder LE, Leinninger GM. Role of central neurotensin in regulating feeding:

417

Implications for the development and treatment of body weight disorders. Biochimica

418

et Biophysica Acta - Molecular Basis of Disease. 2018;1864(3):900-16.

419

27.

Gorwood P, Lanfumey L, Viltart O, Ramoz N. 5-HT2A receptors in eating

420

disorders. Receptors: Humana Press Inc.; 2018. p. 353-73.

421

28.

Plana MT, Torres T, Rodriguez N, Boloc D, Gasso P, Moreno E, et al. Genetic

422

variability in the serotoninergic system and age of onset in anorexia nervosa and

423

obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2019;271:554-8.

424

29.

Lombardi L, Blanchet C, Poirier K, Lebrun N, Ramoz N, Rose Moro M, et al.

425

Anorexia nervosa is associated with Neuronatin variants. Psychiatr Genet.

426

2019;29(4):103-10.

427

30.

Walton E, Hibar D, Yilmaz Z, Jahanshad N, Cheung J, Batury VL, et al. Exploration

428

of Shared Genetic Architecture Between Subcortical Brain Volumes and Anorexia

429

Nervosa. Mol Neurobiol. 2019;56(7):5146-56.

430

31.

Yan X, Zhao X, Li J, He L, Xu M. Effects of early-life malnutrition on

431

neurodevelopment and neuropsychiatric disorders and the potential mechanisms.

432

Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2018;83:64-75.

433

32.

Kesselmeier M, Putter C, Volckmar AL, Baurecht H, Grallert H, Illig T, et al.

High-434

throughput DNA methylation analysis in anorexia nervosa confirms TNXB

435

hypermethylation. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2018;19(3):187-99.

436

33.

Booij L, Casey KF, Antunes JM, Szyf M, Joober R, Israel M, et al. DNA

437

methylation in individuals with anorexia nervosa and in matched normal-eater

438

controls: A genome-wide study. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(7):874-82.

439

34.

Thornton LM, Munn-Chernoff MA, Baker JH, Jureus A, Parker R, Henders AK, et

440

al. The Anorexia Nervosa Genetics Initiative (ANGI): Overview and methods. Contemp

441

Clin Trials. 2018;74:61-9.

442

35.

Duncan L, Yilmaz Z, Gaspar H, Walters R, Goldstein J, Anttila V, et al. Significant

443

Locus and Metabolic Genetic Correlations Revealed in Genome-Wide Association Study

444

of Anorexia Nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(9):850-8.

445

36.

Watson HJ, Yilmaz Z, Thornton LM, Hubel C, Coleman JRI, Gaspar HA, et al.

446

Genome-wide association study identifies eight risk loci and implicates

metabo-447

psychiatric origins for anorexia nervosa. Nat Genet. 2019;51(8):1207-14.

448

37.

Kaye WH, Bulik CM, Thornton L, Barbarich N, Masters K. Comorbidity of anxiety

449

disorders with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2215-21.

450

38.

Hinney A, Kesselmeier M, Jall S, Volckmar AL, Focker M, Antel J, et al. Evidence

451

for three genetic loci involved in both anorexia nervosa risk and variation of body mass

452

index. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22(2):192-201.

453

39.

Bulik-Sullivan B, Finucane HK, Anttila V, Gusev A, Day FR, Loh PR, et al. An atlas

454

of genetic correlations across human diseases and traits. Nat Genet.

2015;47(11):1236-455

41.

456

40.

Schroeder M, Jakovcevski M, Polacheck T, Drori Y, Luoni A, Roh S, et al.

457

Placental miR-340 mediates vulnerability to activity based anorexia in mice. Nat

458

Commun. 2018;9(1):1596.

459

41.

Timko CA, DeFilipp L, Dakanalis A. Sex Differences in Adolescent Anorexia and

460

Bulimia Nervosa: Beyond the Signs and Symptoms. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(1):1.

461

42.

Hübel C, Gaspar HA, Coleman JRI, Finucane H, Purves KL, Hanscombe KB, et al.

462

Genomics of body fat percentage may contribute to sex bias in anorexia nervosa.

463

American Journal of Medical Genetics, Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics.

464

2019;180(6):428-38.

465

43.

Klump KL, Keel PK, Sisk C, Burt SA. Preliminary evidence that estradiol

466

moderates genetic influences on disordered eating attitudes and behaviors during

467

puberty. Psychol Med. 2010;40(10):1745-53.

468

44.

Lilenfeld LR, Kaye WH, Greeno CG, Merikangas KR, Plotnicov K, Pollice C, et al. A

469

controlled family study of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: psychiatric disorders

470

in first-degree relatives and effects of proband comorbidity. Arch Gen Psychiatry.

471

1998;55(7):603-10.

472

45.

Huckins LM, Hatzikotoulas K, Southam L, Thornton LM, Steinberg J,

Aguilera-473

McKay F, et al. Investigation of common, low-frequency and rare genome-wide

474

variation in anorexia nervosa. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23(5):1169-80.

475

46.

Curtis D, Adlington K, Bhui KS. Pursuing parity: Genetic tests for psychiatric

476

conditions in the UK National Health Service. British Journal of Psychiatry.

477

2019;214(5):248-50.

478

47.

Himmerich H, Treasure J. Psychopharmacological advances in eating disorders.

479

Expert Review of Clinical Pharmacology. 2018;11(1):95-108.

480

48.

Ramoz N, Gorwood P. Epigenetics, genetics and physiology in anorexia nervosa

481

and remission. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;29:S3-S.

482

49.

Smith AR, Ortiz SN, Forrest LN, Velkoff EA, Dodd DR. Which Comes First? An

483

Examination of Associations and Shared Risk Factors for Eating Disorders and

484

Suicidality. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2018;20(9).

485

50.

Brown M, Loeb KL, McGrath RE, Tiersky L, Zucker N, Carlin A. Executive

486

functioning and central coherence in anorexia nervosa: Pilot investigation of a

487

neurocognitive endophenotype. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2018;26(5):489-98.

488

51.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PG. Preferred Reporting Items

489

for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLOS Medicine.

490

2009;6(7):e1000097.

491

493

494

495

496

497

498

499

500

501

502

503

504

505

506

507

508

509

510

511

512

513

514

515

516

517

518

519

520

521

522

523

524

Figure 1. Graphical representation of this reviews’ methodological approach for

525

its bibliography selection (adapted from “The PRISMA Statement” [51])

526

Records identified through PubMed database searching

(n = 21)

Records after duplicates removed (n = 70)

Title and Abstract Screening (n = 70)

Records excluded by no topics of interest

(n = 31)

Studies included in the review (n = 34) Records identified through SCOPUS database searching (n = 59)

Records identified through ISI Web of Science database

searching (n = 24)

Full-text articles assessed for eligibility

(n = 39)

Full-text articles excluded, according to the common agreement of the authors

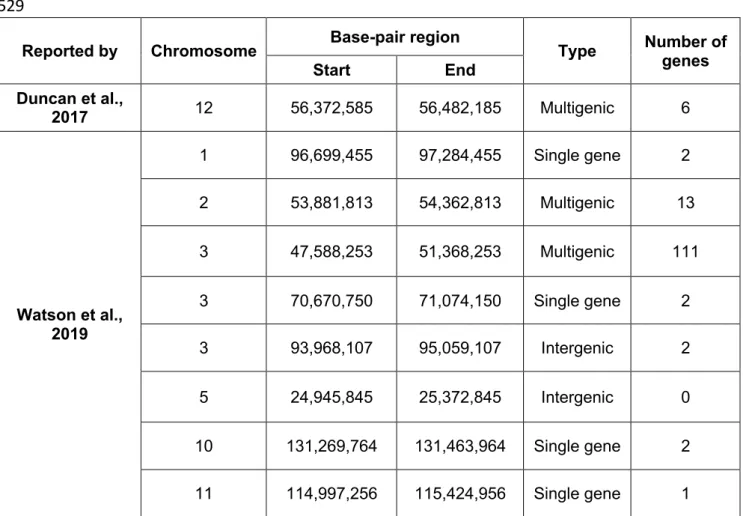

Table 1. List of all genome-wide significant loci identified in anorexia nervosa until now

527

and their main characteristics. [35, 36]

528

529

Reported by Chromosome Base-pair region Type Number of

genes Start End Duncan et al., 2017 12 56,372,585 56,482,185 Multigenic 6 Watson et al., 2019 1 96,699,455 97,284,455 Single gene 2 2 53,881,813 54,362,813 Multigenic 13 3 47,588,253 51,368,253 Multigenic 111 3 70,670,750 71,074,150 Single gene 2 3 93,968,107 95,059,107 Intergenic 2 5 24,945,845 25,372,845 Intergenic 0 10 131,269,764 131,463,964 Single gene 2 11 114,997,256 115,424,956 Single gene 1

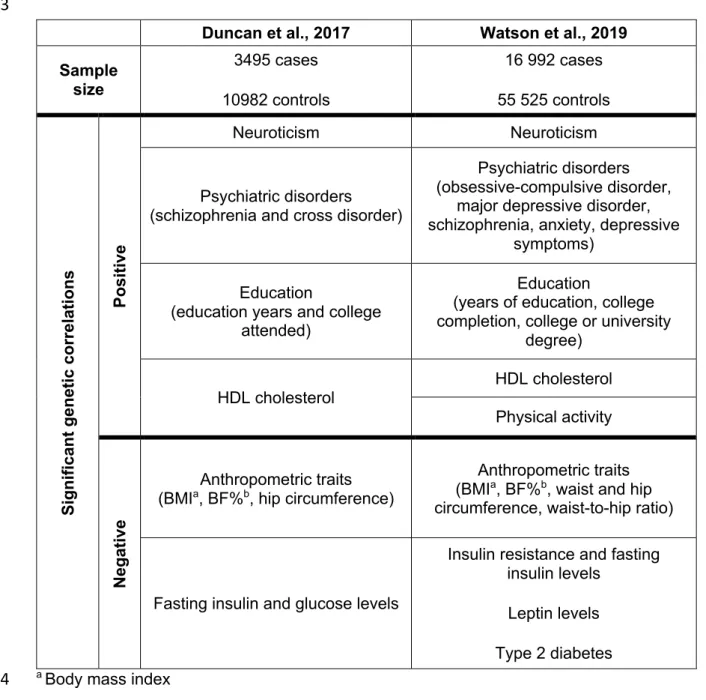

Table 2. Simplified list of significant positive and negative genetic correlations between

530

anorexia nervosa and other phenotypes reported by Duncan et al. and Watson et al..

531

[35, 36]

532

533

a Body mass index

534

b Body fat percentage

535

Duncan et al., 2017 Watson et al., 2019

Sample size 3495 cases 10982 controls 16 992 cases 55 525 controls Si gni fi ca nt ge ne ti c cor re la ti ons Pos it iv e Neuroticism Neuroticism Psychiatric disorders (schizophrenia and cross disorder)

Psychiatric disorders (obsessive-compulsive disorder,

major depressive disorder, schizophrenia, anxiety, depressive

symptoms)

Education (education years and college

attended)

Education (years of education, college

completion, college or university degree) HDL cholesterol HDL cholesterol Physical activity Ne ga ti ve Anthropometric traits (BMIa, BF%b, hip circumference)

Anthropometric traits (BMIa, BF%b, waist and hip

circumference, waist-to-hip ratio)

Fasting insulin and glucose levels

Insulin resistance and fasting insulin levels

Leptin levels Type 2 diabetes

Instructions for Authors 1 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AND

CLINICAL NEUROSCIENCES

MENTAL HEALTH

INSTRUCTIONS FOR AUTHORS

1. Aims and Scope

The International Journal of Clinical Neurosciences and Mental Health is an open-access peer-reviewed journal published by ARC Publishing.

Our goal is to provide high-quality publications in the areas of Psychiatry and Mental Health, Neurology, Neurosurgery and Medical Psychology. Expert leaders in these medical areas constitute the international editorial board.

The journal publishes original research articles, review articles, drug reviews, case reports, case snippets, viewpoints, letters to the editor, editorials and guest editorials.

The International Journal of Clinical Neurosciences and Mental Health follows the highest scientific standards, such as the CONSORT / STROBE guidelines and the Uniform Requirements for Manuscripts Submitted to Biomedical Journals (ICJME).

The journal offers:

• Trusted peer review process

• Fast submission-to-publication time

• Open-access publication without author fees • Multidisciplinary audience and global exposure

Contents

1. AIMS AND SCOPE 1

2. TYPES OF PAPERS 2

2.1. Original research 2

2.2. reviewsand drug reviews 2

2.3. case repOrtsand case snippets 2

2.4. viewpOints 3

2.5. letterstOthe editOr 3

2.6. editOrialsand guest editOrials 3

3. MANUSCRIPT SUBMISSION 3

3.1. cOver letter 3

3.2. Manuscript preparatiOn 3

3.3. suppOrting infOrMatiOn 6

3.4. subMissiOn checklist 6

4. OVERVIEW OF THE EDITORIAL PROCESS 6

Instructions for Authors 2 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AND

CLINICAL NEUROSCIENCES

MENTAL HEALTH

2. Types of papers

The International Journal of Clinical Neurosciences and Mental Health publishes scientific articles in the following categories:

• Original Research. • Reviews. • Drug Reviews. • Case Reports. • Case Snippets. • Viewpoints.

• Letters to the Editor.

• Editorials and Guest Editorials.

As an open-access, online-only publication, the International Journal of Clinical

Neurosciences and Mental Health does not enforce arbitrary word count or illustration limits. The journal a provides a recommendation on the length of manuscripts, but authors are welcome to submit manuscripts outside those recommendations if deemed appropriate.

2.1. Original Research

The International Journal of Clinical Neurosciences and Mental Health welcomes original clinical or translational research related with psychiatry, mental health, medical psychology, neurosurgery and neurology.

Reports of randomised clinical trials should follow the CONSORT Guidelines and reports of observational studies should follow with STROBE Guidelines.

Original Research articles are recommended to have up to 4000 words (excluding title page, abstract, acknowledgements, references and tables) and up to 8 illustrations (figures or tables). Submission of supplementary material is encouraged. This may include additional illustrations of study results (both figures and/or tables), video files presenting study results or procedures, study protocol, study database and statistical analysis plan.

2.2. Reviews and Drug Reviews

Review articles on current topics related to psychiatry, mental health, medical psychology, neurosurgery and neurology, as well as CNS-related drugs are welcome. Both invited and unsolicited submissions are accepted.

Review articles are recommended to have up to 5000 words (excluding title page, abstract, acknowledgements, references and tables.). Inclusion of newly designed figures and tables to summarise key points is encouraged. The used of previously published material is subject to the licence agreement of the original publisher, and should generally be avoided. If previously published materials are, nonetheless, included in the illustrations, the authors should procure appropriate authorisation for use from the original publisher prior to submission.

2.3. Case Reports and Case Snippets

Highly meaningful Case Reports are accepted, presenting major educational content or major clinical findings. Case Snippets should describe a diagnosis or therapeutic challenge.

Case Reports and Case Snippets are recommended to have 750–1000 words (excluding title page, abstract, acknowledgements, references and tables) and up to 2 figures or tables.

Instructions for Authors 3 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AND

CLINICAL NEUROSCIENCES

MENTAL HEALTH

2.4. ViewpointsViewpoints should provide an expert opinion on important topics for medical research or practice, with possibility for covering social and policy aspects. This section encourages dialogue and debate on relevant issues with expert views based on evidence.

Viewpoints are recommended to have 1500–3000 words (excluding title page, abstract,

acknowledgements, references and tables) and can include figures or tables, as deemed appropriate.

2.5. Letters to the Editor

Letters to the Editor should share views on published articles, any findings insufficient for a research article or present ideas on any subject within the scope of the journal.

Letters to the Editor are recommended to have up to 1500 words (excluding title page, abstract, acknowledgements, references and tables) and can include figures or tables, as deemed appropriate.

2.6. Editorials and Guest Editorials

Authors are invited by the Editor-in-Chief to comment on specific topics and express their opinions in the form of Editorials. Nonetheless, interested authors are encouraged to contact the Editor-in-Chief with proposals for writing Editorials.

3. Manuscript Submission

These instructions advise on how the manuscript should be prepared and submitted.

Manuscripts that do not comply with the guidelines will be returned to the authors before being considered for peer-review.

All manuscripts should be prepared in A4-size or US-letter size, in UK or US English throughout the manuscript, a mixture of UK and US English will not be accepted.

Manuscripts should be submitted in *.doc and *.pdf formats, in the appropriate section of the journal website: IJCNMH online submission.

3.1. Cover Letter

A cover letter should be submitted together with the manuscript, in *.doc or *.pdf format, addressed to the Editor-in-Chief, and signed by the author submitting the manuscript.

A template for the cover letter is available for download.

The cover letter should contain statements about originality of your publication, Ethics Committee approval and informed consent (if applicable), conflicts of interest and why in your opinion your manuscript should be published.

3.2. Manuscript Preparation

The manuscript must be divided in 2 files: the Title page (submitted in *.doc format and *.pdf formats) and the Manuscript body (submitted in *.doc and *.pdf formats).

Submitting these 2 files is essential to ensure double-blind peer-review. Failure to provide these 2 files will result in delay in the peer-review process, since the manuscript will be returned to the authors for adjustment.

Instructions for Authors 4 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AND

CLINICAL NEUROSCIENCES

MENTAL HEALTH

Title pageThis should be submitted as a separate file from your manuscript (to ensure anonymity in the peer review process) and should include:

• Article title.

• Authors’ names, titles (e.g. MD, PhD, MSc, etc.) and institutional affiliations.

• Corresponding author: name, mailing address, telephone and fax numbers, email address. • Keywords (maximum of 10), according to MeSH terms, whenever possible.

• A short title (running head) (up to 70 characters). • Abstract word count (up to 250 words).

• Disclosure of conflicts of interest. Any conflict of interests should be declared. If authors have no declaration it should be written: “The authors declare no conflict of interest”.

Manuscript body:

The Manuscript body must be anonymous, not containing the names or affiliations of the authors. It must be structured in the following order: title, abstract, body text,

acknowledgements, references, tables, and figures captions/legends. The manuscript body should contain the title and the abstract, since the title page is not sent to reviewers during peer-review.

• The text must be formatted as follow: • Arial fonts, size: 11 points.

• Double line spacing (see paragraph menu). • Aligned to the left (not justified).

Showing continuous line numbers on the left border of the page. For MS Word you can add line numbers by going to: Page Layout -> Line Numbers -> select “Continuous”; for OpenOffice: Tools -> Line Numbering -> tick “Show numbering”.

Title

A descriptive and scientifically accurate article title should be provided. Abstract (250 words maximum)

An abstract should be prepared for all types of manuscript, except Editorials.

Abstracts of Original Research articles should be structured as: background/objective, methods, results, and conclusions. If the publication is associated with a registered clinical trial, the trial registration number should be referred at the end of the abstract.

Case-reports should be structured as background/introduction, case report, discussion. Systematic review articles should have a structured abstract with generally the same headings as Original Research articles, whereas narrative review articles can have a structured or

unstructured abstract, as deemed appropriate by the authors.

Abstracts for Viewpoint articles and Letters to the Editor, can have a structured or unstructured abstracts, as deemed appropriate by the authors.

Body text

Original research articles

Original research articles should be structured as follows:

Introduction: Should present the background for the investigation and justify its relevancy. Claims should be supported by appropriate references. Introduction should end by stating the objectives of the study.

Methods: Should allow the reproduction of results and therefore must provide enough detail. Appropriate subheadings can be included, if needed.

Results: Should include detailed descriptions of generated data. This section can be separated into subsections with concise self-explanatory subheadings.

Instructions for Authors 5 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AND

CLINICAL NEUROSCIENCES

MENTAL HEALTH

the main findings, their clinical relevance, the strengths and limitations of the study, future perspectives with suggestion of experiments to be addressed in the future.

Review articles and Drug Reviews

These types of articles should be organised in sections and subsections, as deemed appropriate by the authors

Case Reports and Case Snippets

These types of articles should be organised in the general following sections: Introduction/ Background, Case Report, Discussion. Subsections should be used as deemed appropriate by the authors

Acknowledgements

This section should name everyone who has contributed to the work but does not qualify as an author. People mentioned in this section must be informed and only upon consent should their names be included along with their contributions. Financial support (with grant number, if applicable) should also be stated here.

References

References citation in the text should be numbered sequentially along the text, within square brackets. The use of a reference management tool (such as Endnote or Reference Manager) is recommended. References must be formatted in Vancouver style.

Only published or accepted for publication material can be referenced. Personal communications can be included in the text but not in the references list.

Tables

Tables should be smaller than a page, without picture elements or text boxes. Tables should have a concise but descriptive title and should be numbered in Arabic numerals. Table footnotes should explain any abbreviations or symbols that should be indicated by superscript lower-case letters on the body table.

Figures

Figures should have a concise but descriptive title and should be numbered in Arabic numerals. If the article is accepted for publication, the authors may be asked to submit higher resolution figures. Copyright pictures shall not be published unless the authors submit a written consent from the copyright holder to allow publishing.

Figures should be tested and printed on a personal printer prior to submission. The printed image, resized to the intended dimensions, is almost a replication of how the picture will look online. It shall be clearly perceived, non-pixelated nor grainy. Only flattened versions of layered images are allowed. Each figure can only have a 2-point white space border, thus cropping is strongly advised. For text within figures, Arial fonts between 8 to 11 points should be used and must be readable. When symbols are used, the font information should be embedded.

Photographs should be submitted as *.eps at high-resolution (300 dpi or more), *.tif or *.pdf. Graphics should be submitted in *.eps or *.pdf format, to allow proper reproduction. MS Office graphics are also acceptable, if submitted in their original, editable formats.

Lines, rules and strokes should be between 0.5-1.5 points for reproducibility purposes. Nomenclature

All units should be in International System (SI). Drugs should be designated by their International Non-Proprietary Name (INN).

Instructions for Authors 6 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AND

CLINICAL NEUROSCIENCES

MENTAL HEALTH

3.3. Supporting InformationCode of Experimental Practice and Ethics

The minimal ethics requirements are those recommended by the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). Authors should provide information regarding ethics on patient informed consent, data privacy as well as competing interests. If the authors have submitted a related manuscript elsewhere, they should disclose this information prior to submission.

3.4. Submission Checklist

Please ensure you have addressed the following issues prior submission: • Details for competing interests.

• Details for financial disclosure. • Details for authors contribution.

• Participants informed consent statement.

• Authorisation for use of figures included in the manuscript, not produced by the authors and subject to copyright.

• Authorship, affiliations and email addresses are correct. • Cover letter addressed to the Editor-in-Chief.

• Identification of potential reviewers and their email addresses (to be introduced at the online submission platform).

• Manuscript, figure and tables comply with the author guidelines, including the correct format, SI units and standard nomenclature.

• Separated files for Title page (*.doc+*.pdf) and Manuscript body (*.doc+*.pdf)—4 in total. • Manuscript body does not contain the names or affiliations of the authors, or other

direct-ly identifying information, and contain the title and the abstract.

If you have any questions, please contact the editorial office at ijcnmh@arc-publishing.org

4. Overview of the Editorial Process

The International Journal of Clinical Neurosciences and Mental Health aims to provide an efficient and constructive view of the manuscripts submitted to achieve a high quality level of publications. The editorial board is constituted by expert leaders in several areas of medicine particularly in Clinical Neuroscience and Mental Health.

Once submitted, the manuscript is assigned to an editor which evaluates and decides whether the manuscript is accepted for peer-review. At this initial phase, the editor evaluates if the manuscript fulfils the scope of the journal according to the content and minimum quality standards. For peer-review, one or two additional expert field editors will comment on the manuscript and decide on whether it is accepted for publishing with minor corrections or not accepted for publishing. The editor may ask authors to resubmit after revision (minor or major). Decision is based on technical and scientific merits of the work. Reviewers can be asked to be disclosed or stay anonymous. Authors can exclude specific editors or reviewers from the process, upon submission, a rational should be provided.

Upon evaluation, an email is sent to the corresponding author with the decision. If accepted, the manuscript enters the production process. It takes approximately 2-4 weeks for the

Instructions for Authors 7 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AND

CLINICAL NEUROSCIENCES

MENTAL HEALTH

4.1. Appeal ProcessThe editors will respond to appeals from authors which manuscripts were rejected. Their interests should be sent to the Editor.

Two directions can be followed:

• If the Editor does not accept the appeal, further right to appeal is denied.

• If the Editor accepts the appeal, a further review will be asked. After the new review, the editor can reject or accept the appeal. If rejected, nothing else can be done, if accepted the author is able to resubmit the manuscript.

The reasons for not accepting a manuscript for consideration can be: • The manuscript does not follow the scope of the journal.

• The manuscript has potential interest but there are methodological concerns after peer-re-view or editorial examination.