UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA

FACULDADE DE FARMÁCIA

Intensive monitoring in Portugal: a pharmacy-based

model to assess medicines in real-life conditions

The example of new glucose lowering drugs

Carla de Matos Torre

Orientadores:

Professora Doutora Ana Paula Martins

Professor Doutor Hubert G. M. Leufkens

Tese especialmente elaborada para obtenção do grau de Doutor em

Farmácia, especialidade de Farmacoepidemiologia

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA

FACULDADE DE FARMÁCIA

Intensive monitoring in Portugal: a pharmacy-based model to

assess medicines in real-life conditions

The example of new glucose lowering drugs

Carla de Matos Torre

Orientadores:

Professora Doutora Ana Paula Martins Professor Doutor Hubert G. M. Leufkens

Tese especialmente elaborada para obtenção do grau de Doutor em Farmácia, especialidade de Farmacoepidemiologia

Júri:

Presidente:

Doutora Maria Beatriz da Silva Lima, Professora Catedrática e membro do Conselho Científico da Faculdade de Farmácia da Universidade de Lisboa.

Vogais:

Doutor Hubert Geradus Maria Leufkens, Professor of Pharmaceutical Policy and Regulatory Science, Utrecht University, The Netherlands;

Doutora Joëlle Hoebert, Scientist and Project Leader, National Institute for Public Health and Environment, The Netherlands;

Doutor Francisco Batel Marques, Professor Associado da Faculdade de Farmácia da Universidade de Coimbra;

Doutor Nuno Miguel de Sousa Lunet, Professor Auxiliar da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto;

Doutor António Cândido Vaz Carneiro, Professor Catedrático da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Lisboa;

Doutor Rogério Paulo Pinto de Sá Gaspar, Professor Catedrático da Faculdade de Farmácia da Universidade de Lisboa.

D

ECLARATIONThe research presented in this thesis was conducted under the umbrella of the Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Lisbon and the Research Institute for Medicines and Pharmaceutical Sciences (iMed.UL), under the supervision of Professor Ana Paula Martins, Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Lisbon, Portugal, and principal investigator of the Research Institute for Medicines and Pharmaceutical Sciences (iMed.UL), and Professor Hubert G. M. Leufkens, Full Professor at the Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences, Utrecht University, the Netherlands.

The MOMI (Modelo Observacional de Monitorização Intensiva) field study was conducted at the Centre for Health, Evaluation & Research (CEFAR) of the National Association of Pharmacies (ANF) and was fully funded by ANF. ANF had no role in study protocol, data analysis or interpretation of the results retrieved from this research study. Carla Torre participated in the conception and implementation of all studies as well as in the analysis, interpretation of data, and preparation of all the manuscripts forming the present dissertation. Full acknowledgements have been made where the work of others has been cited or used.

To Ana Paula Martins

Hubert Leufkens João Silveira

One's life has value so long as one attributes value to the life of

others, by means of love, friendship, indignation and compassion.

Simone de Beauvoir9

A

GRADECIMENTOSAo olhar pelo retrovisor, escrevo as últimas palavras, que serão sempre parcas no expressar da minha gratidão a todos aqueles que fizeram parte desta viagem.

Em primeiro lugar, agradeço aos farmacêuticos e às farmácias comunitárias que acreditaram e participaram no projeto MOMI, num dos momentos mais difíceis que o nosso País vivenciou. O período em que fomos engolidos por um programa de assistência financeira e o trilho difícil para sairmos dele, com marcas duras e indeléveis que perduram até aos dias de hoje. Estarei sempre grata e reconheço que sem o seu contributo, a concretização deste roteiro não teria sido possível.

Agradeço à Professora Doutora Ana Paula Martins, o facto de ter acreditado em mim, por ter orientado este projecto e de ter feito este caminho comigo, em todas as dimensões. Na dimensão científica, pois a ideia deste projecto é sua. Na dimensão da amizade incondicional e afetos cúmplices, porque nunca me desamparou e esteve sempre comigo, mesmo nos momentos mais difíceis, desta e de outras viagens. Mas sobretudo, por me ter ensinado, no silêncio, mas pelo seu exemplo, de que a busca pela essência dos substantivos colectivos deve prevalecer sobre os substantivos comuns ou próprios. A Professora Ana Paula Martins é um ser humano extraordinário. Consigo, aprendemos a tornar-nos melhores pessoas. Muito lhe devo. A Professora Ana Paula é, e será sempre, a Mestre da minha vida.

Further, I would like to express my deep and sincere gratitude to Professor dr. Bert Leufkens, for your availability, motivation, patience and for being always present in my moments of lack of knowledge and skills. I will be always grateful for you always pushing me forward and making me open my horizons within this research project. I am sure that I would never have made it without you. I really admire you work and achievements in the scientific community. But most of all I admire you for your human values: ethics, rigor, honesty and altruism.

Ao Dr. João Silveira expresso a minha profunda gratidão. Agradeço o facto de ter confiado em mim, por ter guiado o meu percurso profissional, pelas palavras de amizade e motivação e por ter acreditado sempre neste projecto, desde o primeiro dia, sem quaisquer tipos de vacilações. Muito lhe devo e não esquecerei.

À Associação Nacional das Farmácias, na pessoa do seu presidente, Dr. Paulo Duarte, por ter financiado este projeto. A todas as direcções da ANF que, desde há mais de duas décadas, tiveram visão e gizaram a estratégia de colocar a rede das farmácias

10

na geração de evidência na avaliação dos medicamentos e outras tecnologias de saúde em contexto real.

Ao CEFAR (Centro de Estudos e Avaliação em Saúde), o centro onde este projecto nasceu e cresceu. Nunca estive sozinha e agradeço o apoio e a amizade de todos, na concretização deste sonho. Agradeço, de coração, a toda a equipa do CEFAR. Em primeiro lugar na pessoa de quem o dirigiu, Suzete Costa e a todos os colegas, Ana Paula David, Ana Rita Godinho, David Bairrada, Inês Teixeira, José Pedro Guerreiro, Patrícia Longo, Paulo Carvalhas, Maria Cary, Marta Gomes, Sónia Romano e Zilda Mendes. Uma palavra muito amiga e de profunda admiração à Dra. Ana Miranda, por todos os seus ensinamentos de epidemiologia e também ao Humberto Martins, enquanto director da área profissional da ANF, por ter permitido as condições para a realização deste projecto.

De forma particular, agradeço aos que estiveram mais envolvidos neste sonho. Em primeiro lugar, ao José Pedro Guerreiro, pelo seu apoio na componente estatística e sobretudo por ter sido um grande companheiro nesta jornada. Empenhou-se, desde o primeiro minuto, trabalhou noites a fio e de uma forma completamente altruísta, sem nunca ter qualquer pretensão de receber algo em troca. O significado de uma amizade e compaixão incondicionais. O Zé Pedro é um ser humano muito especial, sempre presente com a sua paciência infinita e as suas palavras amigas. Jamais esquecerei tudo o que fez por mim. Ao Paulo Carvalhas, por ter arquitectado toda a estrutura da base de dados do MOMI, bem como pelo envio dos MOMI Watch às farmácias participantes durante o projecto. Sem a sua elevada inteligência, rigor e persistência, nada disto teria sido possível. Agradeço os seus afectos, a sua ternura e as suas risadas quando eu chegava com as minhas ideias impossíveis, às quais, carinhosamente, dizia: “lá vêm mais loucuras da torrekas”.

À Maria Cary por me ter ajudado na revisão sistemática e por toda a sua amizade, carinho e pelo seu carácter íntegro e companheiro. Agradeço ainda à Marta Gomes pela ajuda na implementação do projecto no terreno e à Patrícia Longo, pelo seu empenho no acompanhamento e monitorização do MOMI, bem como pela sua colaboração na classificação, validação e análise dos dados.

À MOMI team dos jovens farmacêuticos entrevistadores: Alina Trindade, Ana Domingos, Ana Rita Martins, Carolina Caldeira, Cristiana Monteiro, Daniela Nunes, Fábio Borges, Maria Santos e Pedro Nunes, por todo o Vosso empenho e dedicação exímios neste estudo. Agradeço ainda à Ana Domingos pela sua enorme capacidade de trabalho, pelo apoio na classificação e validação de dados e por toda a sua amizade. Ao Fábio

11 Borges, por ter ainda participado noutra fase posterior deste trabalho, a revisão sistemática, com toda a sua dedicação aliada à doçura das suas palavras amigas.

Agradeço ao departamento de Sócio-Farmácia da Faculdade de Farmácia da Universidade de Lisboa, na pessoa do seu Presidente, Professor Doutor Rogério Gaspar, por me ter acolhido e, em especial, aos Professores Doutores Helder Mota Filipe e Sofia de Oliveira Martins, e à Dra. Paula Barão, pelos seus contributos científicos nalgumas partes deste trabalho. Agradeço ainda de forma especial à Paula Barão, pela sua amizade e ternura, bem como, pelos seus ensinamentos na área da farmacovigilância. Ao Professor Doutor João Filipe Raposo, por ter feito parte deste projecto, deste o primeiro momento. Por ter sempre a maior disponibilidade e vontade de partilhar comigo o seu extenso conhecimento científico e clínico na área da diabetes, bem como pelas suas palavras amigas e de motivação. Ficarei sempre grata por tudo o que fez por mim.

Aos Professores Doutores Francisco Batel Marques e Carlos Alves, pelo apoio na classificação dos eventos adversos reportados pelos participantes deste estudo. Agradeço ainda ao Professor Doutor Francisco Batel Marques os seus doutos conselhos no início da realização deste trabalho.

Às Unidades de Farmacovigilância do Centro, Norte e Sul (hoje Unidades de Farmacovigilância do Centro, Porto e Setúbal/Santarém) pela formação de farmacovigilância, realizada em 2016, às farmácias que participaram no estudo.

Ao Professor Doutor João Costa pelos seus ensinamentos e à Dra. Joana Alarcão, pelo apoio na realização da revisão sistemática.

À Direcção Nacional da Ordem dos Farmacêuticos, por ter permitido que terminasse esta dissertação e por todas as palavras encorajadoras de todos os membros da Direcção Nacional. Pela amizade que nos une, agradeço de forma especial à Dra. Helena Farinha por todo o seu companheirismo. A Helena é um poço de energia inesgotável, de integridade e fraternidade impolutas.

A todos os colegas da Ordem dos Farmacêuticos pela compreensão, nesta última fase de escrita. Estarei sempre grata, em particular, ao Ricardo Santos, por toda a amizade e companheirismo, e por me ter substituído nesta minha fase de ausência e menor disponibilidade.

Agradeço ao Adam Standring pela revisão linguística de boa parte desta dissertação e ao Fernando Brandão o seu apoio incansável na sua formatação. Ao Jorge Batista agradeço, profundamente, a sua arguta revisão e leitura atenta.

12

À minha coorte da FFUL, PhD together for success, “companheiros de luta e amigos”, Ana Araújo, Cristina Lopes, João Pedro Aguiar, Labib Almusawe, Marta Carvalho e Rui Marques, pelo espírito de ajuda e equipa. Agradeço ainda à Ana Margarida Adivinha pelas mensagens de apoio.

A todos os meus amigos, por todas as palavras de incentivo e pelo facto de estarem sempre presentes no meu trajecto. À minha família, em especial aos meus pais, agradeço os valores incutidos, os seus sacrifícios para darem uma educação digna aos seus filhos e por, ao seu jeito, me terem ensinado a ser uma mulher livre. Agradeço o seu apoio inequívoco e reconheço que para eles, a concordância com as minhas convicções, decisões e rascunhos de projectos de vida nunca foi uma condição para estarem ao meu lado.

15

C

ONTENTSPublications and Scientific Communications ...16

Resumo….………18

Abstract ………..22

List of Abbreviations ...23

CHAPTER 1.General Introduction ...27

CHAPTER 1.1.Addressing real-world: how to bridge the safety and efficacy-effectiveness gap? ...29

CHAPTER 1.2.Objectives and thesis outline ...53

CHAPTER 2. The place of intensive monitoring systems in the real-world evidence generation data ...59

CHAPTER 2.1.Intensive monitoring studies of newmedicines: a systematic review ...61

CHAPTER 3.The rationale behind choosing monitoring new glucose lowering drugs ...107

CHAPTER 3.1. Patterns of glucose lowering drugs utilization in Portugal and in the Netherlands. Trends over time ...109

CHAPTER 4. MOMI (Modelo Observacional de Monitorização Intensiva)...121

CHAPTER 4.1. MOMI methods and participants ...123

CHAPTER 4.2.MOMI results...139

CHAPTER 4.2.1.Usage and quality of life among type 2 diabetes patients initiating new glucose lowering drugs: a comparison across real-world treatment groups ...141

CHAPTER 4.2.2.Intensive safety monitoring of new glucose lowering drugs: results from an inception cohort study ...163

CHAPTER 4.2.3.Effect of different methods on estimating persistence and adherence to new glucose lowering drugs: results of an observational, inception cohort study in Portugal ...189

CHAPTER 4.2.4.Health-related quality of life in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus starting with new glucose lowering drugs: an inception cohort study ...215

CHAPTER 5. General Discussion ...237

APPENDICES ...263

APPENDIX 1. Instituto de Saúde Pública da Universidade do Porto (ISPUP) ethics committee approval (CE14021) ...265

APPENDIX 2. Comissão Nacional de Proteção de Dados (CNPD) approval (5339/2014) ...266

16

P

UBLICATIONS ANDS

CIENTIFICC

OMMUNICATIONSPublications

▪ Torre C, Cary M, Borges FC, Ferreira P, Alarcão J, Leufkens H, Costa J, Martins AP. Intensive monitoring studies of new medicines: a systematic review. (submitted)

▪ Torre C, Guerreiro J, de Oliveira Martins S, Raposo JF, Martins AP, Leufkens H. Patterns of glucose lowering drugs utilization in Portugal and in the Netherlands. Trends over time. Prim Care Diabetes. 2015; 9(6):482–489.

▪ Torre C, Guerreiro J, Longo P, Mota-Filipe H, Raposo JF, Leufkens H, Martins AP. Usage and quality of life among type 2 diabetes patients initiating new glucose lowering drugs: a comparison across real-world treatment groups. (submitted)

▪ Torre C, Guerreiro J, Longo P, Raposo JF, Leufkens H, Martins AP. Intensive safety monitoring of new glucose lowering drugs: results from an inception cohort study.

(submitted)

▪ Torre C, Guerreiro J, Longo P, Raposo JF, Leufkens H, Martins AP. Effect of different methods on estimating persistence and adherence to new glucose lowering drugs: results of an observational, inception cohort study in Portugal. (Patient Preference and Adherence. 2018, in press)

▪ Torre C, Guerreiro J, Longo P, Raposo JF, Leufkens H, Martins AP. Health-related quality of life in people with type 2 diabetes mellitus starting with new glucose lowering drugs: an inception cohort study. (submitted)

17 Scientific Communications

▪ Torre C, Guerreiro J, Longo P, Raposo JF, Leufkens H, Martins AP. Health-related quality of life in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients starting with new glucose lowering drugs: an inception cohort study in Portugal. (accepted to be presented in the 34th International

Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management. Prague, 22-26 August 2018)

▪ Torre C, Guerreiro J, Longo P, Raposo JF, Leufkens H, Martins AP. Intensive safety monitoring of new glucose lowering drugs: results from an inception cohort study in Portugal using patients as a source of information. (accepted to be presented in the 34th

International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic Risk Management. Prague, 22-26 August 2018)

▪ Torre C, Guerreiro J, Longo P, Mota-Filipe H, Raposo JF, Leufkens H, Martins AP. Real life drug usage of new glucose lowering drugs (GLD): Results of an intensive monitoring study in Portugal. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(Supplement S2):128. Presented in 33rd International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology and Therapeutic

Risk Management. Montreal, 26-30 August 2017.

▪ Torre C, Guerreiro J, Longo P, Mota-Filipe H, Raposo JF, Leufkens H, Martins AP. New glucose lowering drugs usage in Portugal: baseline results of an intensive monitoring study in real-life conditions. Presented in XLVII Reunião Anual da Sociedade Portuguesa de Farmacologia, XXXV Reunião de Farmacologia Clínica, XVI Reunião de Toxicologia. Coimbra, 2 February 2017.

▪ Torre C, Guerreiro J, Longo P, Raposo JF, Leufkens H, Martins AP. New Glucose Lowering Drugs Usage in Portugal: Results of an Intensive Monitoring Study in Real-Life Conditions. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25 (Supplement S3):193. Presented in 32nd

International Conference on Pharmacoepidemiology and Therapeutic Risk Management. Dublin, 25-28 August 2017.

▪ Torre C, Martins AP, Leufkens H. Modelo de Monitorização Intensiva. A avaliação de resultados da utilização de medicamentos na prática clínica em Portugal. Presented in II Reunião Científica Anual da Sociedade Portuguesa de Farmácia Clínica e Farmacoterapia. Porto, 12 October 2013.

18

R

ESUMOO conhecimento sobre os riscos e os benefícios dos medicamentos nas populações a que se destinam tem um papel essencial na proteção da saúde pública. Neste âmbito, uma avaliação epidemiológica dos riscos (reações adversas) e dos benefícios da utilização dos medicamentos em contexto real de utilização, estabelecida de forma proactiva e sistemática, antecipa-se como fundamental, em virtude dos indicadores de resultados de eficácia e de segurança obtidos nos ensaios clínicos não serem generalizáveis para a população geral. O objetivo principal desta tese, constituída por 5 capítulos, foi o de contribuir para a avaliação dos novos medicamentos utilizados para o tratamento da diabetes mellitus tipo 2 (DMT2) na rotina da prática clínica, através de um modelo de monitorização intensiva implementado na rede de farmácias comunitárias portuguesas.

A evolução do enquadramento regulamentar da avaliação dos medicamentos descrita no Capítulo 1 veio reforçar a importância da farmacoepidemiologia e da farmacovigilância para a caracterização do perfil de utilização, segurança e efetividade dos medicamentos após a sua entrada no mercado. Neste contexto, várias fontes de informação têm sido utilizadas, desde os sistemas de notificação espontânea, os registos, as bases de dados automatizadas, os modelos de monitorização intensiva, entre outros.

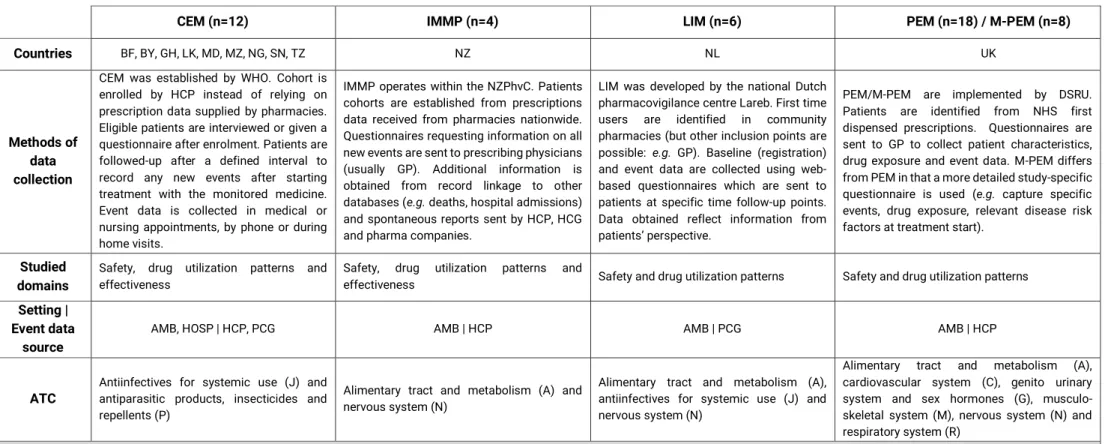

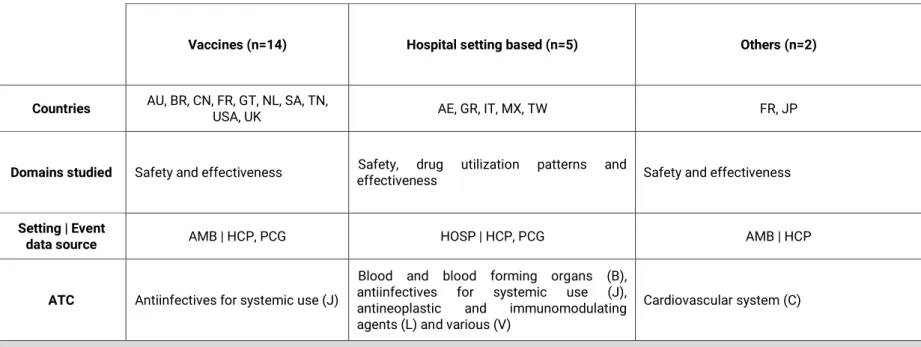

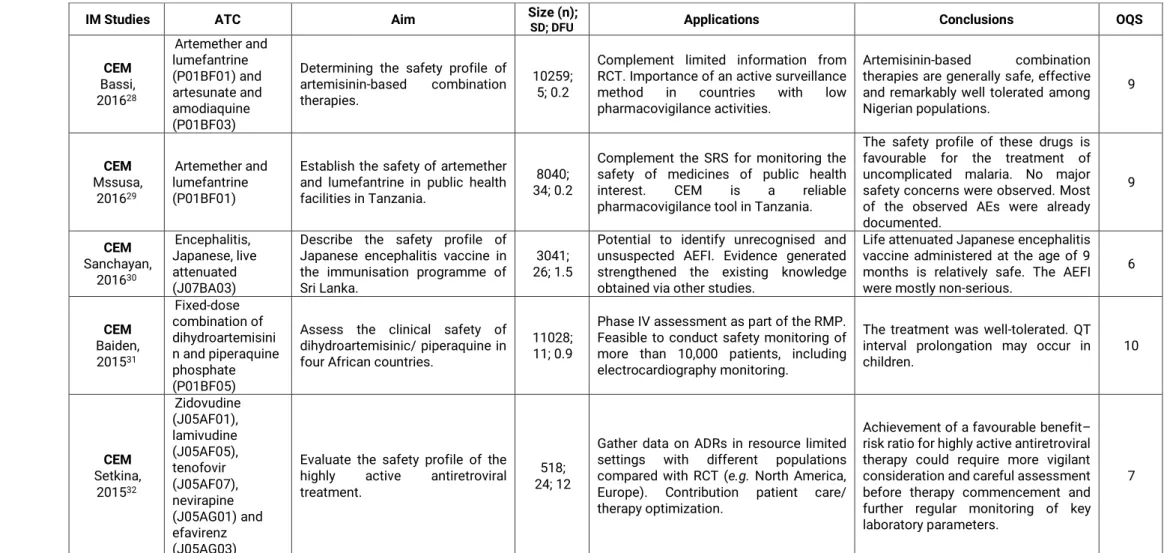

No Capítulo 2, são apresentados os resultados de uma revisão sistemática que descreveu os estudos realizados com recurso à metodologia de monitorização intensiva ao longo da última década. Foram identificados 69 estudos diferentes realizados em 26 países, sendo que 70% dos estudos realizados eram respeitantes a sistemas estabelecidos de monitorização intensiva, dos quais metade correspondiam ao

Prescription Event Monitoring (PEM) / Modified-PEM. Globalmente, os medicamentos

alvo dos sistemas de monitorização intensiva preenchem um dos seguintes requisitos: medicamentos inovadores, recentemente, introduzidos no mercado, visto que existe a necessidade de clarificar a relação benefício/risco, incerteza sobre a segurança (e.g. questões de segurança, previamente, identificadas nos planos de gestão de risco), suspeitas de utilização inapropriada, entre outros. Independentemente das diferenças encontradas respeitantes às metodologias utilizadas, os sistemas de monitorização intensiva, implementados na última década, tiveram como objetivo a recolha ativa e de forma sistemática de informação proveniente da utilização dos medicamentos em contexto real, preencher o gap existente entre os ensaios clínicos (caracterizados pela elevada validade interna e baixa validade externa), sistemas de notificação espontânea

19 (com limitações relativas à sub- e notificação seletiva de eventos adversos) e bases de dados automatizadas (caracterizadas por amostras populacionais representativas, com longos períodos de follow-up, mas frequentemente, com limitações relativas à recolha de co-variáveis/fatores de confundimento relevantes). As aplicações dos estudos de monitorização intensiva analisados versaram: o contributo para o aumento do conhecimento do perfil de segurança e geração de sinal, a identificação de uso off-label e conhecimento do padrão de utilização em contexto real, resposta a questões identificadas nos planos de gestão de risco, entre outros.

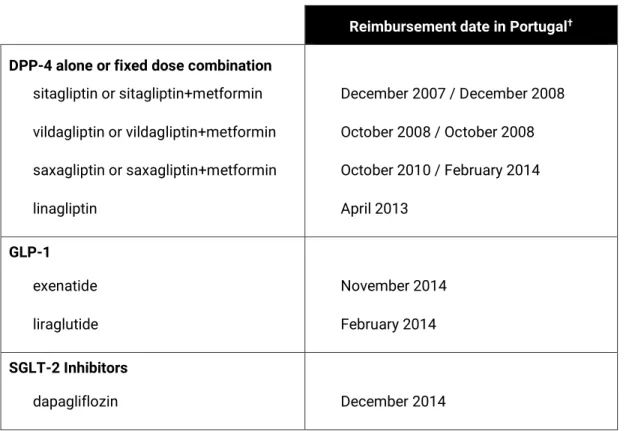

No Capítulo 3 foi apresentada a justificação para a escolha do grupo terapêutico selecionado, os novos medicamentos para o tratamento da DMT2. Os resultados da comparação do consumo de medicamentos para o controlo da diabetes, entre Portugal e a Holanda, no período compreendido entre 2004 e 2013, revelaram que para ambos os países, foi observado um aumento significativo da prevalência da utilização destes medicamentos. Contudo, em Portugal, ao contrário da Holanda, observou-se um elevado consumo dos novos medicamentos, especialmente dos inibidores da dipeptidilpeptidase-4 (DPP-4) isolados ou em associação de dose fixa com a metformina. Em Portugal, em 2013, o consumo de associações de dose fixa, concretamente dos DPP-4 com metformina, representou cerca de 1/4 do consumo total dos medicamentos para a diabetes (excluindo insulinas), sendo residual na Holanda. Por outro lado, a Holanda apresentou uma maior proporção do consumo de metformina, comparativamente, a Portugal.

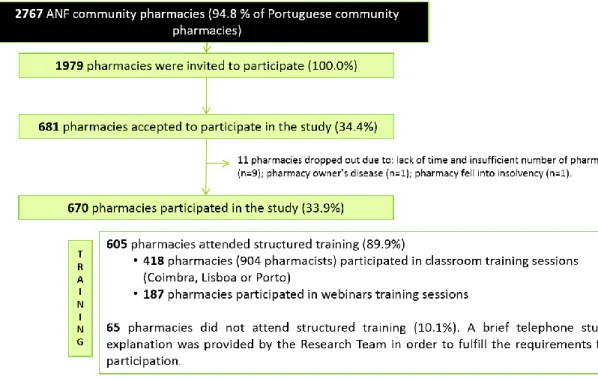

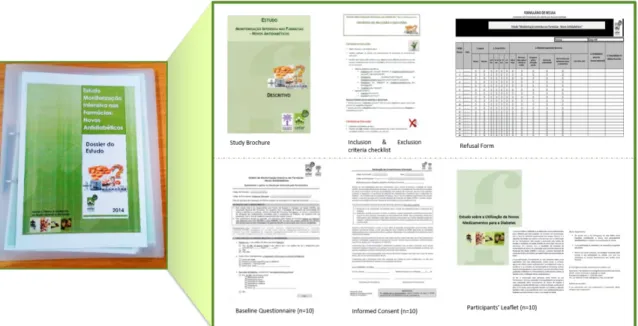

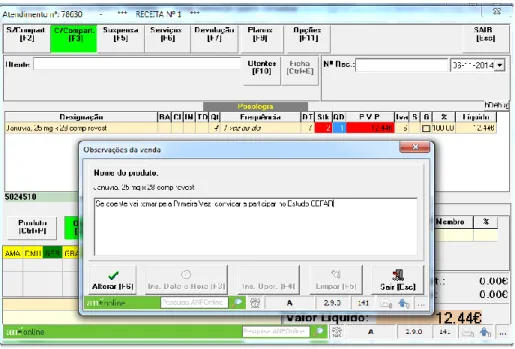

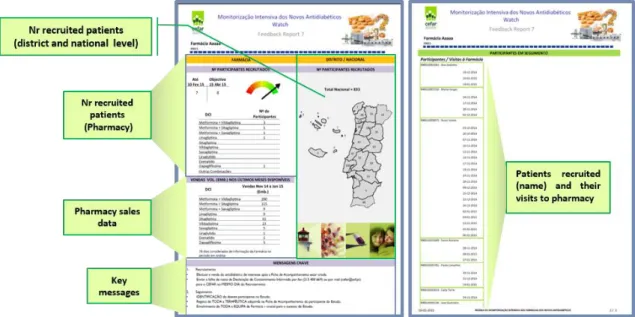

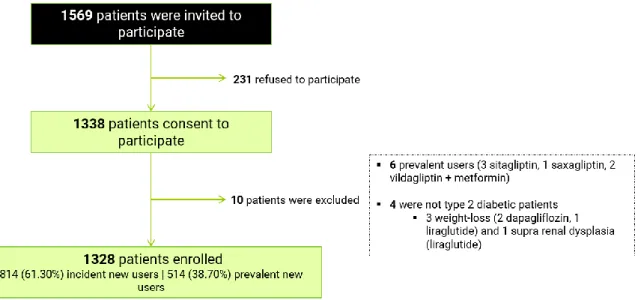

No Capítulo 4 são descritos os métodos e os resultados obtidos do estudo MOMI (Modelo Observacional de Monitorização Intensiva) conduzido entre 15 de novembro de 2014 e 15 de novembro de 2015, na rede de farmácias portuguesas. Os farmacêuticos das farmácias que aceitaram voluntariamente participar, convidaram os adultos com diabetes tipo 2 que adquiriram para uso próprio e pela primeira vez, um dos novos antidiabéticos comparticipados em Portugal, no momento do recrutamento: DPP-4 (isolados ou associação de dose fixa com metformina), agonista do recetor do peptídeo-1 similar ao glucagon (GLP-peptídeo-1) (exenatido ou liraglutido) ou inibidores do co-transportador de sódio e glucose 2 (SGLT-2) (dapaglifozina). Foram convidadas a participar 1979 farmácias, das quais 385 recrutaram pelo menos um doente. Neste estudo a informação foi recolhida através de 3 fontes distintas: 1) questionário baseline administrado por entrevista pelo farmacêutico (dados sócio-demográficos e clínicos auto-reportados); 2) questionários telefónicos: 2.1) questionários realizados às 2 semanas, aos 3 e 6 meses após o início da toma do medicamento (possíveis eventos

20

adversos relacionados com o medicamento de interesse, hipoglicémias, padrão real de utilização e em caso de descontinuação ou switch, identificação das razões) e 2.1) instrumento genérico (EQ-5D-3L) de medição da qualidade de vida relacionada com a saúde (QdVRS) administrado no momento baseline e após 6 meses a toma do medicamento e; 3) dados de consumo do antidiabético de interesse e de toda a co-medicação adquirida pelo participante na farmácia onde foi recrutado, durante o período de observação (6 meses ou até ao momento de descontinuação/switch do antidiabético de interesse, confirmado pelo participante).

No momento do recrutamento, foram encontradas diferenças entre os novos utilizadores incidentes (participantes que utilizaram um medicamento de interesse pela primeira vez e sem exposição prévia a DPP-4, GLP-1 ou SGLT-2) e novos utilizadores prevalentes (participantes que utilizaram um medicamento de interesse pela primeira vez, mas com experiência prévia a pelo menos um medicamento das classes DPP-4, GLP-1 ou SGLT-2). Os novos utilizadores prevalentes representaram 2/5 do total dos participantes e apresentaram uma maior duração da DMT2, prevalência de complicações relacionadas com a diabetes, número de substâncias para o tratamento da DMT2, utilização de insulina e recurso a consultas especializadas para o tratamento da DMT2, comparativamente aos novos utilizadores incidentes.

Cerca de 1/5 dos participantes reportou pelo menos um episódio de hipoglicémia ligeira a moderada, e cerca de 2/5 dos participantes reportaram, pelo menos, um evento adverso (EA), sendo que a maioria dos EA foram experienciados no início do tratamento. No total, foram reportados 1118 EA, dos quais 36.0% não se encontravam descritos no resumo das características do medicamento correspondente, sendo maior a proporção de EA não descritos observada nos utilizadores das DPP-4 isoladas.

Os níveis de adesão e persistência observados aos novos medicamentos para o tratamento da DMT2 foram baixos, tendo sido encontradas diferenças entre os dois métodos utilizados (dados de consumo provenientes da farmácia onde ocorreu o recrutamento (método 1) e a sua combinação com dados de auto-reporte (método 2)). Considerando o método 1, 38.7% (IC 95%: 36.0% - 41.5%) dos participantes foram classificados como persistentes, sendo esta estimativa superior utilizando o método 2 (65.6% (IC95%: 62.9% - 68.2%)). Nos primeiros 6 meses de tratamento, cerca de 1/4 (n=327) dos participantes abandonou o medicamento de interesse, sendo os EA cerca de metade dos motivos indicados para o switch ou descontinuação. Viver sozinho, residir numa região suburbana/urbana e utilizar medicamento de interesse cuja forma de administração é a via oral, foram variáveis associadas à não persistência. Os novos

21 utilizadores prevalentes foram significativamente mais aderentes (proporção de dias cobertos pela terapêutica ≥80%) do que os novos utilizadores incidentes, tendo sido encontrada uma maior proporção de fidelização à farmácia neste subgrupo de participantes.

No que respeita aos resultados baseline da QdVRS, verificou-se que os participantes do género feminino, mais idosos, com maior índice de massa corporal, maior número de doenças crónicas/co-medicação, com complicações relacionadas com a DMT2 e utilização de insulina apresentavam menores valores médios do índice e da escala visual analógica do EQ-5D. Contudo, não foram observadas diferenças entre os novos utilizadores incidentes e os novos utilizadores prevalentes, evidenciando a limitação do instrumento genérico utilizado. Os resultados médios de QdVRS após 6 meses de tratamento, mantiveram-se semelhantes aos resultados obtidos no de recrutamento. Contudo, os participantes que apresentaram piores resultados em baseline foram os que experienciaram um maior aumento da QdVRS.

Como discutido no Capítulo 5, a implementação deste modelo de monitorização intensiva demonstrou o seu contributo na rede de evidência de monitorização de medicamentos na prática clínica em Portugal, concretamente, nos domínios da segurança, padrão de utilização e QdVRS. Não obstante, para que este modelo se consubstancie numa ferramenta adicional estabelecida no contexto de avaliação de medicamentos na rotina da prática clínica, necessita de ser desenvolvido, concretamente no eixo da eficiência (e.g. minimização de recursos envolvidos, utilização de instrumentos digitais na fase seguimento), validado e fazer prova de conceito com outras tecnologias de saúde.

Palavras chave: Monitorização Intensiva, Diabetes tipo 2, Segurança, Padrão de Utilização de Medicamentos, Qualidade de Vida Relacionada com a Saúde.

22

A

BSTRACTChapter 1 introduces the drug life-cycle approach paradigm and emphasizes the need to get real-world data in order to meet this challenge. A systematic review to describe intensive monitoring (IM) systems’ scope in the real-world evidence generation data was presented in Chapter 2. Given that Portugal is one of the European countries with the highest uptake of the newly marketed glucose lowering drugs (GLD) (Chapter 3) monitoring drug usage and its outcomes seemed to be necessary in order to bridge knowledge at the moment of marketing approval to actual clinical practice. A pharmacy-based IM designed to track patients starting one of new GLD, was implemented and described in Chapter 4. A total of 385 pharmacies recruited an inception cohort of 1,328 subjects. At cohort entry, profile differences among incident and prevalent new users of new GLD were found. Prevalent new users, who represented almost 2/5 of study population, were more complex type 2 diabetes mellitus patients as compared with incident new users. More than two fifths reported at least one adverse drug event, most of which were experienced in the beginning of treatment. Low levels of persistence and adherence to newly GLD were observed. HRQoL results of patients starting with, or switching to new GLD, were not adversely affected; participants with worse health conditions at baseline were more likely to experience larger meaningful HRQoL improvements. In Chapter 5, the results were discussed. The implemented pharmacy-based IM model showed the importance of focused cohort studies in generating important real-life drug outcomes data in Portugal, where there is lack of use of data sources and infrastructures that permit to collect and analyse these data in a systematic manner. The method needs to be developed further but holds potential for becoming an additional tool in the Portuguese landscape of medicines’ assessment.

Key-words: Pharmacy-based Intensive Monitoring, Glucose Lowering Drugs, Safety, Usage Patterns, Health-related Quality of Life.

23

L

IST OFA

BBREVIATIONSADE – adverse drug event ADR – adverse drug reaction

AEFI – adverse event following immunization

AHRQ – Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality ANCOVA – analysis of covariance

ANF – Associação Nacional das Farmácias (National Association of Pharmacies) ATC – anatomical therapeutic chemical classification

BMI – body mass index

CEFAR – Centro de Estudos e Avaliação em Saúde (Centre for Health, Evaluation & Research)

CEM – Cohort Event Monitoring CI – confidence interval

CIOMS – Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences

CNPD – Comissão Nacional de Proteção de Dados (Portuguese Data Protection Authority)

CPRD – Clinical Practice Research Datalink DDD – defined daily dose

DFU – duration of follow-up

DHD – defined daily doses per 1000 inhabitants per day DPP-4 – dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors

EMA – European Medicines Agency

ENCePP – European Network of Centres for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance

EQ-5D – Euroqol 5-D-3L EU – European Union

EUnetHTA – European network for Health Technology Assessment FDA – Food and Drug Administration

GLD – glucose lowering drugs

GLP-1 – glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists GP – general practitioner

HbA1c – haemoglobin A1C HCP – healthcare professional HR – hazard ratio

HRQoL – health-related quality of life

ICD-10 – International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision

IM – intensive monitoring

IMMP – Intensive Medicines Monitoring Programme IMS – intensive monitoring system

INU – incident new user IQR – inter-quartile range IR – incidence rate

ISPUP – Instituto de Saúde Pública da Universidade do Porto (Institute of Public Health of the University of Porto)

J-PEM – Japan-Prescription Event Monitoring KM – Kaplan-Meier

LIM – Lareb Intensive Monitoring

MedDRA– Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities MID – minimally important difference

24

MoU – Memorandum of Understanding

M-PEM – Modified-Prescription Event Monitoring

NR – non-respondents NU – new user

OECD – Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development OQS – overall quality score

OR – odds ratio

PAES – post-authorization efficacy studies PASS – post-authorization safety studies PCG – patients/caregivers

PDC – proportion of days covered PDD – prescribed daily dose

PEM – Prescription Event Monitoring PNU – prevalent new user

PRAC – Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee

PRISMA-P – Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols

PT – preferred term

RCT – randomized clinical trials RMP – risk management plan RWE – real-world evidence

SADR – serious adverse drug reaction SCEM – Specialist Cohort Event Monitoring SD – standard deviation

SDM – signal detection methods

SGLT-2 – sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors SmPC – summary of product characteristics

SOC – system organ classification SPR – spontaneous reporting T2DM – type 2 diabetes mellitus VAS – visual analogue scale VIF – variation inflation factor WHO – World Health Organization

CHAPTER 1

General Introduction

CHAPTER 1.1

Addressing real-world: how to bridge the

safety and efficacy-effectiveness gap?

31

1.1.1 S

ETTING THE SCENE:

THE RATIONALE FOR POST-

AUTHORISATION STUDIESBradford-Hill said “all scientific work is incomplete – whether it be observational or

experimental. All scientific work is liable to be upset or modified by advancing knowledge. That does not confer upon us a freedom to ignore the knowledge we already have, or to postpone the action that it appears to demand at a given time” (1). This is especially true

in the context of the landscape of medicines’ assessment - a continuing tale of unfolding risks and benefits (2).

The raison d’être of post-authorization studies is to bridge the gap between the information generated by randomized clinical trials (RCT) and real-world drug usage, since drugs often do not perform as well, or as expected, in routine clinical practice as they do in RCT. Therefore, pre-marketing clinical trials may not provide an accurate picture of drug effects (3–6).

At the time of marketing authorization, we have evidence from RCT which demonstrate efficacy, but only for a specific indication and only for the population studied. At this stage, we have evidence of only the most common adverse drug reactions (ADR) (7). Quality, safety and efficacy are the three pillars of regulatory approval for new pharmaceutical products and they are authorized on the basis that a drug’s benefit is judged to outweigh its potential harm. However, the known limitations of RCT (e.g. selected study population, defined by strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, short duration of time, sample size, selected sites which are typically better equipped than routine care facilities, among others) led to the recognition of a number of well-described “unknowns” – primarily the full safety profile and the effectiveness of the medicine in actual clinical practice (3,8,9).

Eichler and colleagues argued that this gap is, in most cases, a problem of variability in drug response and described both biological and behavioural sources of variability in real-world drug usage. The first source of variability is related to genetic factors and other intrinsic (e.g. sex, age, body weight, co-morbidities or baseline disease severity) and extrinsic (e.g. environmental influences, such as pollution, co-medication or influences of food on pharmacokinetics) factors. The second one is linked to prescribing and drug handling (e.g. inappropriate or off-label prescribing, sometimes encouraged by marketing authorization holders and promotion efforts); and patient adherence and utilization (3).

32

It has been recognized, that the current regulatory process creates an evidence-free zone at the time of a new medicine’s launch and decisions are often taken under conditions of uncertainty. Furthermore, uncertainty about safety may be more prominent, as most studies for regulatory approval are powered on demonstrating efficacy rather than safety (10,11).

The threshold in determining an appropriate balance between benefit and risk with the limited data that is typically available before medicine approval leaves society acting as a double-edged sword concerning the scrutiny of decision-making process. That is to say, regulators are often exposed to challenges from different stakeholders who frequently have opposing views: the need to avoid unnecessary risks or possible less effective (or even ineffective) treatments versus the need to increase early access to medicines and improve the efficiency of drug development (10,12).

In the European Union (EU), during the first 15 years of this century, several medicines were suspended or withdrawn from the market because of safety concerns (13); it still happens today, but less frequently as in the past. However, against this scenario, regulatory agencies have been criticized for being excessively tolerant and accepting too much uncertainties when authorising medicines for the market. Nevertheless, the counter case can equally generate criticism, particularly when regulators are being overly risk-averse, for example, by requesting too much data before medicine approval which postpones marketing authorization decisions. This could be a matter of a great concern, when this delays or precludes patients from receiving potentially life-saving medicines (14). Ultimately, every decision provides an opportunity for error and unintended consequences: approval of unsafe or ineffective medicines (type I regulatory error: false positive decision) or denying a drug a license where it would have caused more good than harm (type II regulatory error: false negative decision) (14).

As most regulators do not have the specific disease experience and do not take the drugs they gave marketing authorization for, Eichler and colleagues argued that public health will be better served if patients’ views of acceptable risk levels for a given benefit are incorporated into benefit-risk assessments (15,16). For example, this was the case of patients’ demands to gain early access to antiretrovirals drugs (17) and, more recently, to have access to natalizumab as a treatment for multiple sclerosis (14). In the latter case, patients claimed that natalizumab’s risks were overemphasized, and insufficient attention was given to its potential benefits. Through a survey of patients with multiple sclerosis, it was found that a majority would “definitely” or “probably” use a treatment that was “significantly more effective than currently available drugs (reduces frequency of

33

relapse or progression in disability) even with a one in a thousand chance of a fatal side-effect” (18). In this circumstance patients’ voices were crucial to reverse the withdrawal

decision that had been taken.

To date, experience of bringing patients to the table has shown that they do not invariably push for early access at any cost, but rather have often expressed a balanced acceptance of levels of risks and uncertainty (19). To better understand the need to foster patients’ timely access to useful medicines (e.g. unmet medical needs), structured tools have been proposed and implemented by regulatory agencies, both by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), to address acknowledged benefit-risk uncertainties. These tools can be based on early, iterative and continuous dialogue (e.g. EMA: adaptive pathways and PRIME scheme; FDA: fast track) or on risk-based marketing authorization approaches (e.g. EMA: conditional approval; FDA: accelerated assessment) (20).

Gate keepers to treatment access include not only regulators and patients but also healthcare providers (HCP) and payers. Over the last decade, the role of payers has become more noticeable, and time-to-market no longer means time-to-authorization but time to reimbursement (21). Data on real-world effectiveness are required to inform clinical decisions and those of payers. Generally speaking, governments and payers are making health policy decisions, regarding access and reimbursement that should answer the three core questions of evidence-based technology evaluation, as defined by Archie Cochrane: “Can it work?”, “Will it work” and “Is it worth it?” (22).

In a health technology assessment framework, external validity should not be neglected, and real-world data is clearly a key issue in this context. It is essential that health technology assessments move from evaluating cost-efficacy in ideal populations with ideal interventions to evaluating cost-effectiveness in real-world populations with real interventions, since findings between these two worlds can clearly be different, as exemplified by van Staa and colleagues with the selective cox-2 inhibitors. This study found that the published cost-effectiveness analyses of coxibs lacked external validity and did not represent patients in clinical practice and therefore should not have been used to inform prescribing policies. The authors demonstrated that the cost effectiveness of coxibs was far worse when the analyses were based on data from clinical practice rather than RCT (23).

This example, which is one among many, clearly illustrates that the rigid model of confirmatory trials is not well suited to satisfy the information needs not only from the regulators but also from the payers (21). On-going dialogue between all stakeholders

34

should be of paramount concern in this aspect. In Europe, over recent years, joint actions between EMA and the European network for Health Technology Assessment (EUnetHTA) have evolved (e.g. early development and planning post-authorisation data collection) with the aim of bridging the gap between regulatory approval and access to market (24).

1.1.2 T

HE DRUG LIFECYCLE APPROACH PARADIGM“La règle me paraît simple : même métabolite, même toxicité…Mais qui pouvait faire le rapprochement ? Je comprends à cet instant que tout est possible, même trente ans après. (…)

Il me reste bien une question : « Combien de morts ? ». “

Irène Frachon (2010) – in “Mediator 150 mg. Combien de morts ?”

Public expectations have grown and delays in acting on drug safety issues are no longer accepted by society. The field of pharmacovigilance - defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as “the science and activities relating to the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse effects or any other possible drug-related problems” (25) – has made a remarkable journey from the time when it was first recognized in the early 60s after the thalidomide tragedy. Since then, methods and tools have been evolving, largely driven in response to the growing complexity of drug safety concerns (26).

Over the last two decades, a tale of drug withdrawals (27,28) has renewed interested in pharmacovigilance. The withdrawal of cerivastatin in 2001 following spontaneous reports of cases of serious and fatal rhabdomyolysis represented a regulatory milestone. Cerivastatin appeared to have a favourable benefit-risk balance at the time of authorization, but partly as a result of inappropriate prescribing (warnings on the label were ignored) had to be taken off the market (3).

This debate was later revigorated with the high profile withdrawal of rofecoxib in 2004 (2). The decision was made after the safety monitoring board of the APPROVe trial found an increased risk of cardiovascular events in patients treated with this drug. After rofecoxib withdrawal, an assessment of the pharmacovigilance system was performed: strengths and weaknesses were highlighted, recommendations were made, and regulatory actions were taken (29).

35 These cases highlighted the weaknesses of the European pharmacovigilance system, which relied mainly on spontaneous reporting (SPR) and in November 2005, new legislation came into force including a number of provisions aimed at strengthening pharmacovigilance. Regulators have shifted from a largely reactive response to drug safety issues to a more proactive approach (29). As a consequence, for example, a risk management plan (RMP), comprising detailed commitments to post-marketing pharmacovigilance, were introduced. Since 2012, RMP are required for all new active substances, for substances with significant changes to marketing authorizations (e.g. new indications) and when an unexpected hazard are identified (30–32). However, a recent review of 15 RMP concluded there is still much room for improvement, given several activities appeared to be inadequate for dealing with the potential risks, poor communication of potential risks to healthcare providers and patients and, a lack of transparency (e.g. available data regarding the most significant aspects of the RMP) (33).

More recently, the discussion about cardiovascular safety of rosiglitazone again focussed attention on the ability of pharmacovigilance systems to identify harm in a timely manner. Although controversial and contested, actions were taken approximately 10 years after the introduction of rosiglitazone. In 2010, EMA decided to suspend the marketing authorization of rosiglitazone while FDA decided to restrict its use (34,35) but required cardiovascular outcome studies for all new antidiabetic drugs (36). This case illustrates that two different regulatory agencies may reach contradictory conclusions despite analysing the same evidence (37). Other discrepancies between agencies are known, for example for cancer drugs (38). Regarding the latter, Tafuri and colleagues found that agencies manage cancer drugs’ uncertainty in different ways: unlike EMA, FDA had a prevailing attitude of accepting risks in order to guarantee quicker access to new treatments although, conversely, product withdrawals are also more easily achieved than EMA (39). The outcome of regulatory decisions about benefit-risk assessments, can ultimately be understood to depend on the level of uncertainty that regulators are willing to accept. The threshold of uncertainty will differ according to, among other factors, therapeutic indications, available treatment options and the judgment of the drug use context.

The ability of pharmacovigilance systems to react promptly in the defence of public health was highlighted once more in the wake of Mediator® scandal in France.

Benfluorex was licensed in 1976, as an add on for hyperlipidaemia and type 2 diabetes

36

cases of valvular disease following benfluorex use were spontaneously reported in 1999, but the drug was only withdrawn a decade later, after several cases had been reported and after results of epidemiological studies had been transmitted to the French regulatory agency (40), among which included, the well-known case-control study conducted by Irène Frachon (41). Although the figures have been disputed by the manufacturer (42), it is estimated that benfluorex was responsible for between 500 and 2000 deaths due to valvular insufficiency in France (40,43,44).

All these high-profile cases lead to an extensive debate and forced the pharmacovigilance community to critically evaluate the existing systems in place. Major changes to the pharmacovigilance legislation in the EU were made at the end of 2010: Regulation 1235/2010 amending Regulation 726/2004 (45) and Directive 2010/84/EU amending Directive 2001/83/EC (46). In brief, the new legislation, applicable in the EU since July 2012 (47):

▪ includes a strengthened legal basis for post-authorization regulation of medicines on the European market (e.g. creation of Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) and definition of clear tasks and responsibilities for all parties; collection of high-quality data relevant to the safety of medicines and patient safety; additional monitoring);

▪ aims to improve efficiency (e.g. Eudravigilance database) and;

▪ aims to increase transparency (e.g. disclosing through the PRAC’s web portal agenda/minutes, conclusions and recommendations of assessments; abstracts of post‐authorization studies; summaries of RMP, etc.).

It was acknowledged when considering how to maximize or indeed assess, the benefit-risk balance, risk must be understood in the context of benefit. The new legislation changed the prevailing paradigm from a risk centred approach to a benefit-risk assessment throughout the entire lifecycle of the medicine. Within the new legal framework, EMA and national regulatory authorities have now extended powers to demand post-authorisation studies, including post-authorization efficacy studies (PAES) in addition to post-authorization safety studies (PASS). PAES are usually required where concerns relating to some aspects of the efficacy of a drug are identified and can only be clarified after marketing authorization. PASS are aiming at identifying, characterizing or quantifying a safety hazard, confirming the safety profile of a medicine, or of measuring the effectiveness of risk management measures (48).

37 The recognition of patients as important players in pharmacovigilance was undeniably another key advance in the new European legislation (49). Patients are currently allowed to report adverse drug events directly to the competent authorities, however the concept of patient reporting schemes is far from new – having been around for more than 50 years (50). Studies demonstrate that patient reporting contributes to identifying new ADR as well as producing new information about known ADR (51–54). In the case of non-serious symptomatic ADR particularly, patient reports can be of great value, since these events are systematically downgraded by healthcare professionals despite affecting patients’ quality of life and adherence to treatment, and thereby the benefit-risk of the drug (55–57). Patient reported outcomes (PRO) have played a role not only in assessing risks but also on other drug related dimensions, such as quality of life and treatment satisfaction. They constitute information from patients about a health condition, its management, and impact on well-being (58–61).

To summarize, over the last few years a paradigm shift in the medicines assessment landscape can be observed. We have moved from a traditional regulatory model, characterized by a binary pre-marketing authorization decision to a life-cycle approach (10). A corollary of this evolving scenario is the need for effective alignment and communication among all the healthcare ecosystem’s stakeholders (62) and, the demand for regulatory pathways to proactively mirror real-world data for safety, effectiveness and patterns of drug utilization.

1.1.3

R

EAL-

WORLD DATA SOURCES OF INFORMATIONOne of the main issues in obtaining real-world knowledge for drug assessment is the data sources available for analysis. Studies may involve either data collected prospectively for the purpose of the particular study (de novo data collection), i.e. primary data, or data that were already collected for another purpose, i.e. secondary data (63). Over time a number of post-marketing data sources have developed including, spontaneous reporting, automated databases, registries and intensive monitoring (IM) programmes which have all contributed to a better understanding of real-world drug effects. No single method or data source is ideal, therefore integrating evidence from a range of sources, and understanding their strengths and limitations –, including features that might affect data quality and validity such as how the data were collected, enrolment and coverage factors–, offers the best way of meeting the challenges of post-marketing

38

environment. A brief description of these sources, with special emphasis on intensive monitoring methods, is given below.

Intensive Monitoring

In the past, pharmacovigilance has been primarily concerned with finding new ADR, but Waller and Evans argue that pharmacovigilance should be less focused on finding harm and more focused on extending knowledge of safety (64). Within this paradigm shift, and as previously described, regulatory agencies have been reforming their systems in order to keep pace with recent developments, specifically being more proactive with the aim of strengthening the evidence base in the post-authorization phase. After its development more than 30 years ago, IM methodology based on drug event monitoring (65) has received renewed interest (32,66).

In the late 1970s and early 1980s established IM systems were launched in New Zealand (Intensive Medicines Monitoring Programme) (67) and in the UK (Prescription Event Monitoring) (68). Since then, these systems and its background methodology have evolved and been implemented in several countries worldwide (32,69,70).

Compared to SPR, which passively monitors all drugs during their whole life cycle, IM combines the strengths of pharmacoepidemiological and clinical pharmacovigilance approaches and focuses on specific drugs. Decisions on which drugs go into IM programs (entry criteria) can be positively influenced by the following factors: innovative/recently launched drugs since there is a need to clarify the benefit-risk balance in daily practice, uncertainty about safety (e.g. specific safety issues previously identified in the RMP, drug with structural or pharmacological similarities to drugs associated with particular safety concerns) and when there is a suspicion of inappropriate drug use (26,67,71,72).

Through its non-interventional features, IM provides real world data (i.e. without the inclusion or exclusion criteria of RCT) (29) and for a specific period of time, it is actively focused on gathering longitudinal information, from the first day of drug use (inception cohort) which makes it possible to collect time related information about the course of the adverse drug events (73,74). Furthermore, because it has a cohort study design, it allows for the estimation of event incidence rates.

It is important to expand on the importance of the inception cohort technique in the context of medicines’ assessment. A new user design is an inception cohort if all persons in the study are first-time medication users. It begins by identifying all patients in a defined population (both in terms of people and time) who start a new medication

39 and implies that follow-up begins at precisely the same time as initiation of therapy (75,76). This approach takes into account of the event timing in relation to the start of drug exposure and reduces biases by excluding prevalent users from the study (77). This is of importance, because patients who stay on treatment for a longer time may be less susceptible to the event of interest and therefore the real risk associated with the drug could be distorted (depletion of susceptibles) (78,79). Although excluding prevalent users may reduce the sample size, Schneeweiss argued that “if researchers decide

against an incident user design, they may gain precision at the cost of validity” (80).

However, since treatment naïve patients represent only a small part of drug users in daily practice, characterization and assessment of drug effects should also encompass patients who, given the progressive nature of their condition and the lack of treatment response and/or tolerability issues switched from previous drugs or added the newer drug (for example from the same therapeutic class). New methodological approaches, specifically by means of prevalent new-user cohort design, which do not violate the inception cohort principle technique, have been proposed (81).

IM studies are not without their limitations. The proportion of adverse events that go unreported is unknown and frequently no information is provided about the patients/healthcare professionals who did not participate (non-response bias). This factor could result in an underestimation of the true incidence of adverse events and possibly distort information about the risk (32,73). The generated cohort may be biased by channelling (preferential prescribing to subgroups of patients defined by specific characteristics, such as having a condition that is refractory to a previous therapy) or switching (past experience with an alternative drug may modify the risk of adverse drug events) (79). Moreover, IM studies usually lack the presence of a concurrent control group, and therefore the true background incidence of events is not known. It may be not clear whether the observed frequency in the exposed group is higher than what would be experienced by a comparable group unexposed to the monitored drug (82).

Usually, IM studies are not large enough to detect very rare or even rare adverse events. However, some authors have argued that this method is not the most efficient way to detect new rare signals. For such, other methodological and design approaches should be considered. For example, SPR would probably be a more suitable method followed by a case control (or nested case-control) study to confirm the signal. Non-database prospective cohort studies are seen as inefficient in finding rare events because one needs to follow a very large cohort to identify the frequency of these types of events (32,74). In addition, the usual limited follow-up time does not allow for the

40

detection of long-term outcomes or events with long latency periods (e.g. cancer) (71,72).

IM is not restricted to the collection of adverse drug events. It can also be used to investigate other dimensions of drug use such as adherence to treatment, impact of drug adverse events on patients’ quality of life, ‘benefit’ data (e.g. health-related quality of life) and patterns of drug use, especially those that add to knowledge on the safety of the drug (e.g. medication errors, co-medication, treatment indication).

Spontaneous Reporting Systems

One of the main sources of post-marketing information on drug safety is SPR systems. Experiences have demonstrated that these schemes have triggered many regulatory actions (83,84) and are now well-established across developed and some developing countries (85). However, a large degree of variability (e.g. lack of standardization, terminology used) between systems has been reported (86).

The primary purpose of SPR schemes is the detection of new, rare and potentially serious harmful drug effects. Their ability to offer a fast and reasonably cost-efficient monitoring scheme across all drugs on the market throughout their entire lifecycle, covering the whole population, including special groups, is one of their major advantages (26). Additional studies (e.g. analytical studies: cohort, case-control, etc.) are, however, needed to confirm potential safety signals identified through SPR (29).

SPR cannot be used to calculate accurate ADR incidences, do not provide understanding of risk factors or elucidate patterns of use and the amount of clinical information available is often too limited to permit a thorough case evaluation (87,88). As the act of (voluntarily) suspect ADR reporting depends on human factors, this method is often compromised by selective, under or over reporting (86,87). In clinical practice, it was estimated that fewer than 5-10% of suspected ADR are reported (89).

Automated Databases

Large practice and record-linked databases have been a significant driver of pharmacoepidemiology research, since they often meet the need for a cost-efficient means of conducting post-authorization studies. Their size allows the study of uncommon diseases or rare events and their longer follow-up times and representativeness in terms of daily practice, make it possible to study real-world effectiveness, safety and utilization patterns (90).

41 The major weaknesses of automated databases are related to the quality of data inputted into them; data are recorded and gathered for administrative purposes and/or as part of clinical patient care; not for research purposes. Databases, particularly administrative/claims databases, lack information on several potential confounding variables, namely data on smoking, alcohol consumption, date of menopause/menarche and reproductive history in women, physical activity, occupation, among others. Information about diagnoses could also be less reliable (if diseases are primarily coded for billing) and disease severity is frequently lacking. All these potential missing variables can be of great importance to investigate specific drug effects’ research questions (91,92).

The last two decades have witnessed the development of key databases along with the associated knowledge and methodology that have allowed landmark studies to be conducted. Nonetheless, poor quality in conducting and reporting studies using databases was commonplace, even being published in the top medical journals. The existence of conflicting results between studies when using the same database was reported (93–95). Further, the presence of immortal time-bias and other time related bias, which tend to exaggerate the benefits of the studied drugs was also a reality (96). For example, this was the case of several observational studies conducted in the beginning of the century, which showed surprising results associated with the use of statins: fracture rate by 50% (97), rate of dementia by 71% (98), rate of depression by 60% and rate of suicidal behaviour by 50% (99). Even more recently, two studies reported a remarkable reduction in mortality (>50% lower rates of all-cause mortally) associated with the novel sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT-2) use for T2DM treatment, again due to time-related bias (100).

A number of theories were developed to explain the associations found, often leaving basic clinical pharmacology and pharmacoepidemiologic principles behind. Unquestionably, when conducting research studies using databases, we should bear in mind Brian Strom’s quote: “Databases should not distract us from sound methodological

and clinical thinking” (101).

Registries

Registries are an important and a commonly used tool for medicines post‐approval data collection (102). They can be thought of as programs that collect data from which studies may derived (103). Registries are classified according to how their populations are defined. A patient registry should be considered as a structure for the standardised

42

recording of data from routine clinical practice on individual patients identified by the diagnosis of a disease (disease registry: e.g. cancer and rare diseases), the occurrence of a condition (e.g. pregnancy), the prescription of a drug (exposure registry: e.g. monoclonal antibodies), a hospital encounter, or any combination of these (66).

The multipurpose nature of registries sometimes means that they are often organized for broader questions and may lack a focused hypothesis (104). Other limitations include selection bias, differential completeness of follow-up and data collection issues (e.g. quality of data, exhaustiveness) (66).

A glimpse at some data sources for non-randomized medicines assessment in everyday clinical practice has been described above. In an evolving world, however new sources of information are regularly emerging, such as social media platforms (e.g. Twitter, Tumblr and Facebook), which are being increasingly used to discuss and share health issues, posing new challenges to the scientific community. Currently, it is estimated that there are over 2.3 billion active social media users worldwide, growing by an estimated 1 million new users every day (105). There has been increased interest in how to use these data sources to provide patient-generated information relevant for medicines safety surveillance (66). However, more work remains to be done in order to determine and better understand how these data can be efficiently and properly leveraged and incorporated into an overall pharmacovigilance strategy in the real-world drug environment (106).

R

EFERENCES1. Bradford Hill A. President ’s Address The Environment and Disease: Association or Causation? Proc ofthe R Soc ofMedicine. 1965;295–300.

2. Avorn J. Two Centuries of Assessing Drug Risks. New Engl Med J. 2012;367 (3):193–7.

3. Eichler H, Abadie E, Breckenridge A, Flamion B, Gustafsson LL, Leufkens H, et al. Bridging the efficacy-effectiveness gap: a regulator’s perspective on addressing variability of drug response. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2011;10(July).

4. Silverman SL. From Randomized Controlled Trials to Observational Studies. AJM

[Internet]. 2009;122(2):114–20. Available from:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.030.

5. Ligthelm R, Borz V, Gumprecht J, Kawamori R, Wenying Y, Valensi P, et al. Importance of Observational Studies in Clinical Practice. Clin Ther. 2007;29:1284–

43 92.

6. Martin K, Bégaud B, Latry P, Miremont-salamé G, Fourrier A, Moore N. Differences between clinical trials and postmarketing use. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;57 (1):86–92.

7. Black N. Why we need observational studies to evaluate the effectiveness of health care. Bmj. 1996;312:1215–8.

8. Schneeweiss S, Avorn J. Postmarketing studies of drug safety - A European initiative could help bring more transparency and rigour to pharmacoepidemiology. Bmj. 2011;342(February).

9. Zimmerman M, Mattia JI, Ph D, Posternak MA. Are Subjects in Pharmacological Treatment Trials of Depression Representative of Patients in Routine Clinical Practice? Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:469–73.

10. Eichler HG, Pignatti F, Flamion B, Leufkens H, Breckenridge A. Balancing early market access to new drugs with the need for benefit/ risk data: A mounting dilemma. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7(10):818–26.

11. Staa TP Van, Smeeth L, Persson I, Parkinson J, Leufkens HGM. What is the harm – benefit ratio of Cox-2 inhibitors ? Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:405–13.

12. Pignatti F, Luria X, Abadie E, HG E. Regulators , payers , and prescribers : can we fill the gaps? Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(October):930–1.

13. Mendes D, Alves C, Batel Marques F. Testing the usefulness of the number needed to treat to be harmed (NNTH) in benefit-risk evaluations: case study with medicines withdrawn from the European market due to safety reasons. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2016;15(10):1301–12.

14. Eichler H, Bloechl-daum B, Brasseur D, Breckenridge A, Leufkens H, Raine J, et al. The risks of risk aversion in drug regulation. Nat Publ Gr [Internet]. 2013;12(December):907–16. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nrd4129. 15. Eichler H, E A, Raine J, T S. Safe Drugs and the Cost of Good Intentions. New Engl

Med J. 2009;360(14):1378–80.

16. Bernabe RDLC, Van Thiel GJMW, Van Delden J. Patient representatives’ contributions to the benefit’risk assessment tasks of the European Medicines Agency scientific committees. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(6):1248–56.

17. Eichler H, Abadie E, Baker M, Rasp G. Fifty years after thalidomide ; what role for drug regulators? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;74 (5):731–3.

18. Calfee JE. A Representative Survey of M . S . Patients on Attitudes toward the Benefits and Risks of Drug Therapy. 2006.