www.jped.com.br

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Analysis

of

contextual

variables

in

the

evaluation

of

child

abuse

in

the

pediatric

emergency

setting

夽

Ana

Nunes

de

Almeida

a,

Vasco

Ramos

a,∗,

Helena

Nunes

de

Almeida

b,

Carlos

Gil

Escobar

b,

Catarina

Garcia

baUniversidadedeLisboa,InstitutodeCiênciasSociais,Lisboa,Portugal

bHospitalProfessorDoutorFernandodaFonseca,DepartamentodePediatria,UnidadedeUrgênciaeCuidadosIntensivos,

Amadora,Portugal

Received3June2016;accepted14September2016 Availableonline27April2017

KEYWORDS Physicalviolence; Sexualviolence; Children; Portugal; Hospitalurgency

Abstract

Objective: This article comprises a sample of abuse modalities observed in a pediatric emergencyroomofapublichospitalintheLisbonmetropolitanareaandamultifactorial char-acterizationofphysicalandsexualviolence.Theobjectivesare:(1)todiscusstheimportance ofsocialandfamilyvariablesintheconfigurationofbothtypesofviolence;(2)toshowhow physicalandsexualviolencehavesubtypesandinternaldiversity.

Methods: A statistical analysis was carried outin a database (1063 records of childabuse between2004and2013).Aformwasappliedtocaseswithsuspectedabuse,containingdataon thechild,family,abuseepisode,abuser,medicalhistory,andclinicalobservation.Afactorial analysisofmultiplecorrespondencewasperformedtoidentifypatternsofassociationbetween socialvariablesandphysicalandsexualviolence,aswellastheirinternaldiversity.

Results: Theprevalenceofabuseinthispediatricemergencyroomwas0.6%.Physicalviolence predominated(69.4%),followedbysexualviolence(39.3%).Exploratoryprofilesofthesetypes ofviolencewereconstructed.Regardingphysicalviolence,thegenderoftheabuserwasthe firstdifferentiatingdimension;thevictim’sgenderandagerangewerethesecondone.Inthe caseofsexualviolence,theageoftheabuserandco-residencewithhim/hercomprisedthe firstdimension;thevictim’sageandgendercomprisedtheseconddimension.

Conclusion: Patternsofassociationbetweenvictims,familycontexts,andabuserswere iden-tified.Itisnecessarytoalertcliniciansabouttheimportanceofsocialvariablesinthemultiple facetsofchildabuse.

©2017SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisanopen accessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/ 4.0/).

夽

Pleasecitethisarticleas:AlmeidaAN,RamosV,AlmeidaHN,EscobarCG,GarciaC.Analysisofcontextualvariablesintheevaluation ofchildabuseinthepediatricemergencysetting.JPediatr(RioJ).2017;93:374---81.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:vasco.ramos@ics.ul.pt(V.Ramos). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2016.09.005

PALAVRAS-CHAVE Violênciafísica; Violênciasexual; Crianc¸as; Portugal;

Urgênciahospitalar

Análisedasvariáveiscontextuaisnaavaliac¸ãodosmaus-tratosinfantisapartir

darealidadedeumaurgênciapediátrica

Resumo

Objetivo: Esteartigoapresentaumacasuísticademodalidadesdemaus-tratosnumaUrgência Pediátrica(UP)deumhospitalpúbliconaÁreaMetropolitanadeLisboaeumacaracterizac¸ão multifatorialdaviolênciafísicaeviolênciasexual.Osobjetivossão:1)discutiraimportância devariáveissociaisefamiliaresnaconfigurac¸ãodeambos;2)mostrarcomoviolênciafísicae violênciasexualapresentamsubtiposediversidadeinterna.

Métodos: Realizou-seumaanáliseestatísticadeumabasededados(1063registosde maus-tratosinfantis, entre2004-2013).Utilizou-seoformulárioaplicadoacasos comsuspeitade maus-tratos, comdadossobreacrianc¸a,família,episódiodemaus-tratos, agressor,história médicaeobservac¸ãoclínica.Foirealizadaumaanálisefatorialdecorrespondênciasmúltiplas paraidentificarpadrõesdeassociac¸ãoentrevariáveissociaiseviolência,físicaesexual,bem comosuadiversidadeinterna.

Resultados: Aprevalênciademaus-tratosnestaUPfoide0,6%.Predominamaviolênciafísica (69,4%)eaviolênciasexual(39,3%).Perfisexploratóriosdestestiposforamconstruídos.Quanto à violênciafísica,osexo do agressorestruturaaprimeira dimensãodiferenciadora; sexoe grupoetáriodavítimaestruturamasegunda.Nocasodaviolênciasexual,aidadedoagressor ecoresidênciacomeleestruturamaprimeiradimensão;idadeesexodasvítimasorganizama segundadimensão.

Conclusão: Identificaram-sepadrõesdeassociac¸ãoentrevítimas,contextosfamiliarese agres-sores.Énecessário alertarosclínicos paraaimportânciadasvariáveissociais nasmúltiplas facesqueosmaus-tratosassumem.

©2017SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigo OpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4. 0/).

Introduction

In its several forms, child abuse remains a characteristic thataffectscontemporarychildhoodonaworldwidescale. Itoccursinavarietyofcontexts,particularlythosewhere thechildshouldbesaferandmoreprotected(family,home, school,institutionswherecare isprovided).1Itis amajor

causeofchildhoodmorbidity andmortality,andits

conse-quencesforthedevelopmentandwell-beingofchildrenare

devastating.1,2

It is estimated that 4---16% of children in high-income

countriesarephysicallyabusedandoneintensuffers

psy-chological violence or neglect.3 According to the World

HealthOrganization(WHO),18millionchildreninEuropeare

victimsofsexualviolence,44million,ofphysicalviolence,

and55million,ofpsychologicalviolence;approximately850

childrendieeachyearasaresultofthesetypesofabuse.4

Theactualityandseverityofthisproblempersists,3despite

child protection policies developed internationally since

the 1970s.5 In a scenario of greater social intolerance to

such situations,6 the contribution of researchersand

pro-fessionals is crucial so that decision-makers can promote

adjustedpublicpolicies(forinformationregistration,

train-ingoftechnicians,prevention,intervention,andfollow-up

inthefield).

In the last decade, Portugal has implemented specific

policiesonchildsafety,allowingthecountrytomake

signif-icantprogressinthisarea.However,reliablenationaldata

arenotyetavailabletoallowafullandaccurateassessment

ofthesituation.

Aimingtoovercomethelackofstudiesinthearea,this

article presents a seriesof maltreatment modalities in a

pediatricemergencyroom(PER)unitofapublichospitalin

Lisbonandamultifactorialcharacterizationofthetwomost

frequenttypes,physicalviolence,andsexualviolence.The

objectivesare(1)todiscusstheimportanceof familyand

socialvariables(e.g.,gender ofvictimsandabusers,type

ofrelationship,time)intheconfigurationofbothtypesof

abuse;(2) toshowhowphysical andsexualviolence have

subtypesandinternaldiversity.

Definitions

Inline withthe ConventionontheRightsof theChild,an individualyoungerthan18yearsisconsidereda‘‘child’’.In 1999,theWHOdefinedchildabuseasallformsofphysical oremotional abuse,sexualviolence, neglect,or commer-cialexploitationthatresultsinactualorpotentialharmto thechild’shealth,survival,development,ordignityinthe contextofarelationshipofresponsibility,trust,orpower.6It

considersasphysicalviolenceanactionbyanycaregiverthat

causesactualorpotentialphysicalharmtothechild.Sexual

violenceisanactinwhichthecaregiverusesthechildfor

hisorhersexualgratification. Emotionalviolenceincludes

the failure by the caregiver to provide a child-friendly

environment(e.g.,restrictingmovement,threatening,

ridi-culing, intimidating, discriminating, rejecting, and other

non-physicalformsofhostiletreatment),7whichadversely

impactsthechild’sdevelopmentandemotionalhealth.

intimidationand continuousabuseofachild overanother

whohasnochancetodefendhimorherself.8,9

Neglectorabandonmentisdefinedasthecaregiver’s

fail-uretoensurethechild’sdevelopmentinareasconsideredto

bevital,suchashealth,education,emotionaldevelopment,

nutrition,shelter,andsafety.8

Methods

Participants

Thisstudyincludedrecordsof1063childrenoveraten-year period(from2004 toOctober 2010, aged 0---16 yearsand fromthelastdateuptoage18),identifiedasallegedvictims ofsomeformofchildabuse(bythepatienthimorherself, his/hercaregiver,ortheattendingphysician),whocameto, orwerereferencedtothePERunitofthehospital.

Tools

Asdatacollectioninstrument,aspecificformwasusedfor caseswithsuspectedabuse,filledoutbythemedicalteam during the emergency episode. This is a semi-structured questionnairethat contains dataon thechild and his/her family,theabuseepisode,theabuser,medicalhistoryand clinicalobservation,andthesubsequentrecommendations forthesituation.Thecollectiondependedontheinterview andobservationperformedbytheattendingclinicianinthe PERunitand,thus,thereissomeheterogeneityinthe com-pletionofthesocialfields.

Procedures

The variables ofthe collectiontool, ona paperform(up to 2011) and computer file (from 2011 onwards), were retrospectivelyinserted intoa computerizeddatabase for posterior analysis by the multidisciplinary team (Hospi-tal Support Center for at-Risk Child and Youth). Data includedthevictim’scharacteristics(gender,age,household composition,personalhistoryofchronicdiseases,domestic violenceintheusualdomicile),theabuser’scharacteristics (genderand age,relationship withthe victim),and abuse (dateofoccurrence,typeofabuse),aswell asthe subse-quentlyimplementedmeasures.

Statistical

analysis

Firstly,thestudysamplewasbrieflydescribed.Exploratory models were then constructed, containing the two most frequent types of abuse in the sample: physical violence (64.2%)andsexualviolence(39.3%).Themodelsarebased onthemultiplecorrespondencefactorialanalysis,usingthe optimal scaling method.10,11 This technique aims to

ana-lyze associationsbetween variables in a multidimensional

space, summarizing informationabout a large number of

category variables, facilitating the understanding of how

they organize themselves into specific patterns. For the

numerical variables with normal distribution, the means

andthestandarddeviationswerecalculated.Forthe

varia-bles without normal distribution, the median, minimum

andmaximumvalueswerecalculated.Thechi-squaredtest

wasusedforthecomparativeanalysesincategorical

varia-bles. This technique does not replace any predictive or

riskmodel.StatisticalanalyseswereperformedusingSPSS

Statistics®(IBMSPSSStatisticsforWindows,Version24.0.NY,

USA).

Ethicalconsiderations

Thedatacollectionduringtheclinicalprocessisperformed bytheclinicianafterverbalconsentprovidedbythechild’s oradolescent’scaregiverinthePERunit,accordingtothe law.Theproceduresforcollecting,processing,and analyz-ingdatawereapprovedbytheHospitalEthicsCommitteeof thePERunit.

Results

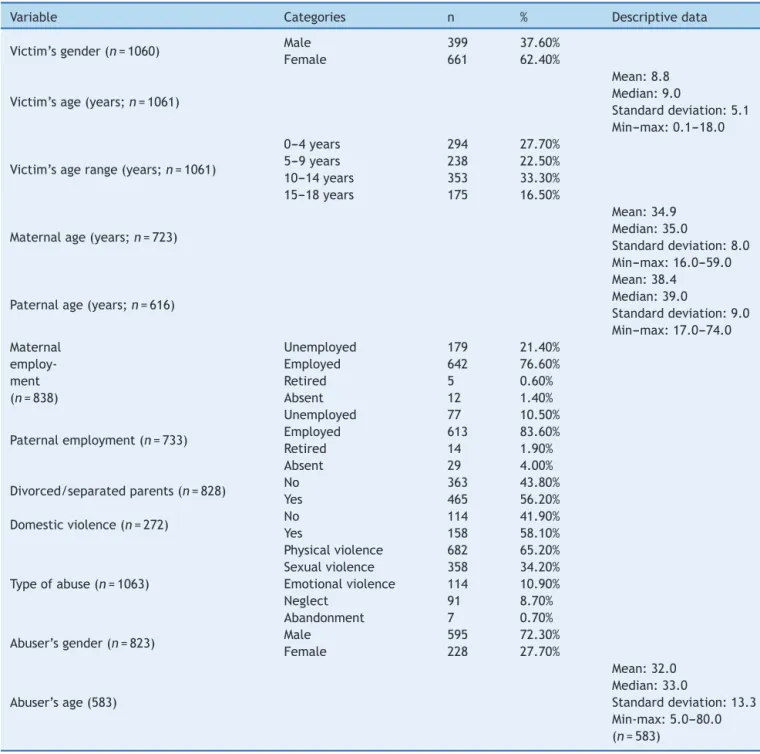

Duringthestudyperiod,1063casesofabusewererecorded, corresponding to 0.6% of occurrences in this PE. Most of thevictimswerefemale(62.4%)andthemeanagewas8.8 years(SD±5.1).Overall,mostepisodesoccurredinchildren aged10---14years(32.7%).Femalevictimstendedtobeolder (mean=9.4,SD±5.0).Mostofthemalevictimswereaged 0---4yearsold(32.5%).Regardingthevictims’parents,the meanageofthemotherswas35years(SD±8),whereasthe meanage ofthefatherswas38years(SD±9).Mostwere employed(83.6%offathersand76.6%ofmothers)andmore thanhalf(56.2%)weredivorcedorseparated.In158cases, therewasa reportof domestic violence in thehousehold wherethechildusuallylived.

Physicalviolence wasthe most common typeof abuse (69.4%),followedbysexual(39.3%)andemotionalviolence (22.2%). In 8.7% of the cases,the assessed children were victims of neglect and in 0.7% of cases, they had been abandoned.Mostoftheabusersaremales(72.3%),witha meanageof 32years(SD±13.3).Withslightvariationsin theirrelativeweight,thisisthepatterntypicallyseenina PERunit,12,13differentfromwhatisfound,forinstance,at

theChildandYouthProtectionCommissions(Comissõesde

Protec¸ãodeCrianc¸aseJovens [CPCJ]),whereneglectand

emotionalviolencearethemostfrequentlyrecordedtypes

(Table1).14

Timeintroducesothercharacterizationpatterns.Despite

theannualvariations(thelongitudinalanalysisdidnot

con-sider theyear2004, sincetheformwasnotin useonthe

beginningofthatyear),therewasanincreasingtrendinthe

numberofcasesdetected.Buttheannualevolutionpertype

ofabuseisdifferentiated.Thenumberofcasesofsexual

vio-lencehasremainedstable,withpeaksin2007and2012.As

forthecasesofemotionalviolence,theyhaveincreasedin

recentyears(Fig.1).

The analysis of the monthly distribution of reported

episodes of violence indicates a cumulative mean of 83

occurrences. The monthly variation, which refersto

sea-sonalrhythmsofsociallife,issignificant:thereweremore

casesinthespringandsummermonths(March,May,June,

July, September, and October) and fewer cases in late

autumn and winter (November, December, and January).

Physical violence was the most common type of abuse

Table1 Samplecharacteristics.

Variable Categories n % Descriptivedata

Victim’sgender(n=1060) Male 399 37.60%

Female 661 62.40%

Victim’sage(years;n=1061)

Mean:8.8 Median:9.0

Standarddeviation:5.1 Min---max:0.1---18.0

Victim’sagerange(years;n=1061)

0---4years 294 27.70%

5---9years 238 22.50%

10---14years 353 33.30%

15---18years 175 16.50%

Maternalage(years;n=723)

Mean:34.9 Median:35.0

Standarddeviation:8.0 Min---max:16.0---59.0

Paternalage(years;n=616)

Mean:38.4 Median:39.0

Standarddeviation:9.0 Min---max:17.0---74.0 Maternal

employ-ment (n=838)

Unemployed 179 21.40%

Employed 642 76.60%

Retired 5 0.60%

Absent 12 1.40%

Paternalemployment(n=733)

Unemployed 77 10.50%

Employed 613 83.60%

Retired 14 1.90%

Absent 29 4.00%

Divorced/separatedparents(n=828) No 363 43.80%

Yes 465 56.20%

Domesticviolence(n=272) No 114 41.90%

Yes 158 58.10%

Typeofabuse(n=1063)

Physicalviolence 682 65.20%

Sexualviolence 358 34.20%

Emotionalviolence 114 10.90%

Neglect 91 8.70%

Abandonment 7 0.70%

Abuser’sgender(n=823) Male 595 72.30%

Female 228 27.70%

Abuser’sage(583)

Mean:32.0 Median:33.0

Standarddeviation:13.3 Min-max:5.0---80.0 (n=583)

Source:Emergencysignformfortheabusedchild(2004---2013).

inDecember(monthsthatcoincidewithschoolholidaysand children staying at home).Emotional violence cases were morecommoninthelasttwomonthsoftheyear(November andDecember).

Exploratory

profiles

of

physical

violence

and

sexual

violence

Exploratoryprofilesoftheassociationbetweensocial varia-blesandthemostcommontypesofabuseweredelineated usingtheFAMC.TheresultsareshowninFigs.2and3.

Varia-blesassociatedwiththevictimandwiththeabuser(gender

andagegroup)andfamilycontext(divorced/separated

par-ents)wereincluded.

Asforphysicalviolence,theabuser’sgenderconstitutes

thefirstdimension,whilethevictim’sgenderandagegroup

constitutesthesecond one (Fig. 2).The abuser’s ageis a

factorthatmediatesthesetwoelements.

Afirstprofileofphysicalviolencewasidentified,inwhich

victimsandabusersareadolescents(lowerright-hand

cor-ner),insituationsofpeerviolence(i.e.,bullying)occurring

bothinsideandoutside theschoolsettings.Asecond

pro-file(lowerleft-handcorner)correspondstomaleabusers,

tendingtobeolder,whoattackvictims,especiallyfemales,

96 95 89 128 132 115 111 107 128

1 1 0 2 1 0 0 2 0

30 24 34 44 45 36 31 55 45

12 10 10 9 11 11 5 6 11

15

4 6 8 2 6

24 15 29 58 70 61 86 85 76 75 61 79 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140

2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

Total Neglect Abandonment Emotional violence Sexual violence Physical violence 66 77 109 80 113 102 99 86 96 91 63 61

0 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 1

16 27 29 22 43 33 38 43 31 32 26 9 2 8

11 8 11

5 8 4 10 6 5 8 11 10 7 9

13 6 15 5 16 9 47 53 80 56 77 70 61 48 61 55 41 30 0 20 40 60 80 100 120

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec

Total

Neglect

Abandonment Sexual abuse

Physical violence Emotional violence

Figure1 Annualandmonthlyevolution(totalandpertypeofcase).

Source:Emergencysignformfortheabusedchild(2004---2013).

together.Athirdprofile(upperleft-handcorner)highlights femaleabusers,separated,ordivorced,betweentheages of20and 39.Here,thevictimstend tobemaleandvery young(between5and9yearsofage)andlivinginpartial co-residencewiththeabuser.Thereisafourthprofile,less defined,intheupperright-handcorner,inwhichthevictims areverysmall,malechildren;informationabouttheabuser andthemaritalstatusoftheparentsisscarce.

Regardingsexual violence,the dataarestructured dif-ferently.The ageofthe abuserandco-residencewiththe aggressor constitute thefirst dimension.The victims’age andgender constitute the second one. The abuser’s gen-der and recent separation/divorce are the elements that connectthetwodimensions.

There is an association between male aggressor and femalevictims (bottomof the chart). In this profile, vio-lence occurs in situations where the victim comes from familiesin whichtheparents arenotseparated/divorced. Thesearemaleabuserswhoattackpre-adolescentor ado-lescentfemalevictims.Asecondprofile(upperpartofthe chart)associatesfemaleabusersbetweentheagesof30and 39withyoungervictims,whocomefromsettingsinwhich theparentshaveseparated.Thequalityofthedatapresents somebiashereduetothelackofinformationontheidentity andage oftheabuser,whichcompromisesthedescription oftheothertwoquadrants.Thissignsuggeststherelative

opacity thatsurroundssexualviolence situationsinvolving veryyoungchildren,inadditiontothefactthattheymaybe practicedbywomenorthroughtheirconnivance/protection oftheabuser/partner.

Discussion

Thepresentseries,obtainedfromthecontextofaPERunit doesnotdifferfromothersfoundintheliterature,namely Portuguesestudies.8,9Thedescriptivestatisticsshowedthat

thetypeofabusemostfrequentlyobservedinthePER

(phys-ical and sexual violence) are, therefore, forms of active

maltreatment, asopposed to neglect(typically identified

through social work services and technicians),1 and their

relativeweightfollowcommonpatterns.15

This sample showed signs of physical violence among

peers, especially among older children. If, in other

countries,bullyinghasacquiredsomestatisticalvisibility,as

wellasinpediatricnewspapers,5,16inPortugaltheapproach

ofthesubjectremainsincipient.Thisiscertainlyduetothe

disregard or lack of notificationof thesesituations in the

currentprotocolsofinformationcollection.

The gender of the child and of the abuser were

considered inthe analysis.Thegender variablehada

Category Point Graph

Co-residence Abuser’s age range Abuser’s age range Family events Abuser’s gender Victim’s gender

Dimension 2

2.0

1.5

1.0

0.5

0.0

–0.5

–1.0

–1.5

–2.0

–2 –1 0 1 2

Dimension 1

Partial co-residence

Abuser 20-29

Recent separation/divorce

Victim 0-4

Unknown

Victim 5-9

Male victim

Abuser’s age unknown

No data on parents

Abuser’s gender unknown

Victim 10-14

Victim 15-18 No recent separation/divorce

Abuser 40-49 Abuser 50+

Abuser <19 Female abuser

Male abuser

Total co-residence Female victim Abuser 30-39

Normalization variable

Figure2 Factorialanalysisofmultiplecorrespondence:physicalviolencea.

Category Point Chart

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

0.5

0.0

–0.5

–1.0

–1.5

–2.0

–2.5

–2.5 –2.0 –1.5 –1.0 –0.5 –0.0 –0.5 –1.0 –1.5 –2.0 –2.5

Dimension 2

Dimension 1

Co-residence Abuser’s age range Abuser’s age range Family events Abuser’s gender Victim’s gender

Unknown

Abuser’s gender unknown

Victim 0-4

Female abuser

Male victim

Partial co-residence

Abuser 30-39 Recent separation/divorce

Victim 5-9

Victim 15-18

Victim 10-14Abuser <19

Abuser 50+

Abuser 40-49

Total co-residence Abuser’s age unknown

Abuser 20-29 Male abuser Female victim No data on parents

No recent separation/divorce

literature,17 as follows: abusers are mostly males (72%),

with mainly female victims (62%); gender was important

in structuring the closeness or distance between

illustra-tivevariablesintheconstructionofbothtypesofviolence,

physicalorsexual.

Comparedtoothers,this studytested theintroduction

ofsocialvariablesthatareseldomusedintheanalysisand

characterizationofchildabuse.Time,ontheonehand,and

themaritalrelationshipbetweenthechild’sparents,onthe

otherhand,showedinnovativeresults.

The seasonal pattern of abuse has become apparent:

springandsummershowmaximumpeaks,whereaslatefall

andwintershowminimumvalues.The relativestabilityof

physical violence throughout the year contrasts with the

concentrationofsexualviolenceinthesummermonthsand

in December. Further researchwill allow a better

under-standingofthis variability;but therhythms of schoollife

(with children staying at homefor longerperiods of time

orexclusivelyunderthecustodyofthefamilyduringschool

vacation)maybepartoftheexplanation.

Conversely, the nature of the marital

relation-ship between the child’s parents (married parents vs.

divorced/separatedparents) wasan explanatory variable.

Itisaresultthatstandsoutfromthedominantapproachin

theliteratureonchildabuse,whichfavors---inthe

charac-terizationofthecouple’srelationship---thequestionofthe

presence of violence.18 Thus, the parents’ marital status

(whethertheyaretogetherorseparated),initself,playsa

roleintheconfigurationoftwosubtypesofsexualviolence:

between male abusers and pre-adolescent or adolescent

female victims and between female abusers and younger

children.Thefirstscenarioisassociatedwithparents who

livetogether;thesecond,withseparated/divorcedparents.

The data refersprimarily tosuspected cases of violence;

sometimes,at ayoungage,theyaredifficulttoproveand

dependonthe(biased?)reportoftheparentaccompanying

thechildtothePERunit,whomaybeinvolvedinasituation

oflitigiousseparation.

Thisarticlealsoattemptedtoapplyamultidimensional

methodology, not commonly employed in the literature,

whichallowedthe discoveryof other subtypesof physical

andsexualviolence.Genderplaysanimportantroleinthe

structuringoftheseprofiles:thegenderofthechildandof

theabuserinphysicalviolence,aswellasthechild’sgender

inthedifferentformsofsexualviolence.Itisalsoworth

not-ingtheexistence,incasesofsexualviolence,ofthewoman

asthe abuserofa youngerchild, whichis areality rarely

identifiedordiscussedinsimilarstudies,19buttowhichthe

interventionmustbeattentive.

Thelimitationsofthisstudyoriginate,toagreatextent,

fromthegapsinthefillingoutofdatabytheprofessionalsof

thePERunit,asituationenhancedbythecircumstancethat,

todate,protocolcompletionisnotmandatory.Thefactthat

itis filledoutduringthe busyhospitalworking hoursalso

contributestothelowerprecisionandattentiongiventothis

process.Thesefactorsexplainthelowerqualityorevenlack

ofdataonthechild’ssocialbackground,particularlyevident

inthe caseof parents ofsexual violencevictims (levelof

education,occupation,andemployment,amongothers).

ItisknownthatthesituationsreportedinaPERunitare

onlyafractionof casesofchild abuse,evenamongthose

where the child is taken to the hospital20; andthat such

abuse is often only detected after multiple visits.21 The

expansion and improvement of the questions usedin the

formanditsconversionintoamandatoryplatform,attached

tothehospitalfile,willcontributetoovercomethe

prob-lemsofdataincompletion,aswell astoincreasetherate

ofdetectionofsituationsofviolence,inthewakeof

docu-mentedgoodpractices.15,22

Betterawarenessoftheimportanceofsocialandfamily

variables,aswellasoftheschoolcontextonthemultiple

facetsofabuse,willinevitablybeusefultohealthcare

pro-fessionals,trainedmainlyfortheassessmentoforganicor

psychologicalriskfactors.Thisstudyintendstocontribute

inthissense.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgements

TheauthorswouldliketothanktheteamofthePediatrics DepartmentofHospitalFernandoFonseca,EPE,for provid-ingtheinformationandforthesupportprovidedduringthis study.They wouldalso liketothankDéboraTerra for the reviewofthemanuscriptinBrazilianPortuguese.

References

1.RadfordL,CorralS,BradleyC,FisherHL.Theprevalenceand impactofchildmaltreatmentandothertypesofvictimization intheUK:findingsfromapopulationsurveyofcaregivers, chil-dren and young people and young adults. ChildAbuse Negl. 2013;37:801---13.

2.UNICE.F.Hiddeninplainsight---astatisticalanalysisofviolence againstchildren.NewYork:UNICEF;2014.

3.GilbertR,WidomCS,BrowneK,FergussonD,WebbE,JansonS. Burdenandconsequencesofchildmaltreatmentinhigh-income countries.Lancet.2009;373:68---81.

4.WHO. European report on preventing child maltreatment. Copenhagen:WorldHealthOrganization;2013.

5.GilbertR,FlukeJ,O’DonnellM,Gonzalez-IzquierdoA,Brownell M,GulliverP,etal.Childmaltreatment:variationintrendsand policiesinsixdevelopedcountries.Lancet.2012;379:758---72. 6.WHO. Report ofthe consultationon childabuse prevention.

Geneva:WorldHealthOrganization;1999.

7.RunyonD,WattamC,IkedaR,HassanF,RamiroL.Childabuse and neglectbyparents and othercaregivers.Geneva: World HealthOrganization;2002.

8.FanteC.Fenômenodebullying:comopreveniraviolêncianas escolaseeducarparaapaz.Campinas:Verus;2005.

9.RodriguezNE.Bullying,guerranaescola.Lisboa:SinaisdeFogo; 2004.

10.GreenacreMJ.Correspondence analysisin practice. 2nd ed. BocaRaton:Chapmann&Hall/CRC;2007.

11.MeulmanJJ.Optimalscalingmethodsformultivariate categor-icaldataanalysis.Leiden,TheNetherlands:LeidenUniversity; 1998.

12.CruzME,Gonc¸alvesE,BarbosaMC,VianaV,IlharcoMJ,Sequeira F,etal.Crianc¸asmaltratadas:apontadoicebergue.Acta Pedi-atrPort.1997;28:35---9.

14.NascimentoJ,FerreiraI,ZilhãoC,PintoS,FerreiraC,CaldasL, etal.Oimpactodoriscosocialnuminternamentopediátrico. ActaPediatrPort.2013;44:15---9.

15.Louwers EC, Korfage IJ, Affourtit MJ, Scheewe DJ, van de MerweMH,Vooijs-MoulaertFA,etal.Detectionofchildabusein emergencydepartments:amulti-centrestudy.ArchDisChild. 2011;96:422---5.

16.deOliveiraWA,SilvaMA,daSilvaJL,deMello FC,doPrado RR,Malta DC. Associationsbetween thepractice of bullying andindividual and contextual variablesfrom theaggressors’ perspective.JPediatr(RioJ).2016;92:32---9.

17.May-ChahalC.Genderand childmaltreatment:theevidence base.SocWorkSoc.2006;4:53---68.

18.Mills LG, Friend C, Conroy K, Fleck-Henderson A, Krug S, Magen RH, et al. Woman abuse and child protection: a

tumultuousmarriage(PartII)Childprotectionanddomestic vio-lence:training,practice,andpolicyissues.ChildYouthServRev. 2000;22:315---32.

19.BarthJ,BermetzL,HeimE,TrelleS,ToniaT.Thecurrent preva-lenceofchildsexualabuseworldwide:asystematicreviewand meta-analysis.IntJPublicHealth.2013;58:469---83.

20.Flaherty E, Sege R. Barriers to physician identification and reportingofchildabuse.PediatrAnn.2005;34:349---56. 21.RavichandiranN,SchuhS,BejukM,Al-HarthyN,ShouldiceM,

AuH,et al.Delayedidentificationofpediatricabuse-related fractures.Pediatrics.2010;125:60---6.