FUNDAÇÃO GETULIO VARGAS

ESCOLA BRASILEIRA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO PÚBLICA E DE EMPRESAS DISSERTAÇÃO EM ADMINISTRAÇÃO

THE PROSOCIAL CLASS: HOW SOCIAL

CLASS INFLUENCES PROSOCIAL BEHAVIOR

YAN BERNARDES VIEITES

Rio de Janeiro - 2017DISSERTAÇÃO

APRESENTADA ÀE

SCOLAB

RASILEIRA DEA

DMINISTRAÇÃOFicha catalográfica elaborada pela Biblioteca Mario Henrique Simonsen/FGV

Vieites, Yan Bernardes

The prosocial class : how social class influences prosocial behavior / Yan Bernardes Vieites. – 2017.

6 f.

Dissertação (mestrado) - Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas, Centro de Formação Acadêmica e Pesquisa.

Orientador: Rafael Guilherme Burstein Goldszmidt. Inclui bibliografia.

1. Classes sociais. 2. Status social. 3. Conduta. 4. Socialização. I. Goldszmidt, Rafael Guilherme Burstein. II. Escola Brasileira de Administração Pública e de Empresas. Centro de Formação Acadêmica e Pesquisa. III. Título.

The Prosocial Class:

How Social Class Influences Prosocial Behavior

Yan Vieites

August 10, 2017

Abstract

The concept of noblesse oblige establishes that the differential in privileges between the rich and the poor should be balanced by a differential in duties towards those in need. However, the empirical findings regarding which are the most prosocial groups have been as controversial as this assertive. Whereas research in the so-called psycholog-ical framework has advocated a negative relationship between social class and prosocial behavior, the economic approach has claimed the opposite (i.e., positive) direction to be true. This article sought to disentangle conflicting findings from these strands of research across two different studies. In the first study, we conducted a series of focus groups in both wealthy and impoverished areas. Results suggested that research in the domain of social class has been circumscribed to an almost conventionalized few proso-cial behaviors that are not representative neither of wealthy nor of poor individuals. In the second study, we conducted surveys in the same areas. Results revealed that, despite having less resources and opportunities to help others, lower social class individ-uals are more prosocial than their upper-class counterparts. Furthermore, prosociality differences cannot be explained by a different pattern of targets of help across the social spectrum. Implications for practice and research on prosociality are also discussed.

Keywords: Social Class, Socioeconomic Status, Prosocial Behavior, Generosity

Introduction

Source of contention among philosophers, economists, and sociologists, the normative interpretation of the adequate allocation of resources and opportunities has oftentimes per-meated the concept of social class (e.g., Durkheim, 2014; Hayek, 2012; Marx et al., 1959; Rawls, 2009; Sandel, 2010; Weber, 2009). However controversial, not seldom people resort

to the idea of noblesse oblige to justify the reasons why the differential in privileges between the rich and the poor should be balanced by a differential in duties towards those in need.

Despite such rooted belief, recent research has suggested an ambiguous relationship be-tween social class and prosocial behavior – a voluntary action intended to benefit another (Eisenberg et al., 2006). Studies in psychology tend to advocate a negative relationship be-tween social class and prosociality (Piff et al., 2010), claiming that the less affluent are more compassionate (Stellar et al., 2012), altruistic (Chen et al., 2013), empathically accurate in judging others’ emotions (Kraus et al., 2010a), less narcissistic (Piff, 2014), and less uneth-ical (Piff et al., 2012a; Wang and Murnighan, 2014) when compared to their upper-class counterparts. Research out of the realm of psychology, in contrast, converges to the oppo-site (i.e., positive) relationship, suggesting that those with more resources donate (Gittell and Tebaldi, 2006; James and Sharpe, 2007), help (Korndörfer et al., 2015), and volunteer (Wilson and Musick, 1998) more and are more trusting as well as trustworthy in economic games (Benenson et al., 2007).

Regardless of the theoretical underpinnings, however, studies linking social class and prosociality have restricted their focus to the scrutiny of a conventionalized few behaviors, such as monetary donations and measures of trust and generosity in experiments (see Ko-rndörfer et al., 2015 for an exception). By doing so, scholarly research has largely neglected the fact that individuals from distinct social classes may foster distinct other-regarding be-haviors (e.g., Lee and Chang, 2007). This is possible because either different types of proso-cial behaviors require different personal characteristics such as interpersonal proximity and compassion, or because peculiarities pertaining to each class (e.g., tax incentives and access to social institutions) facilitate or hinder certain types of prosocial behavior.

It goes without saying that people from contrasting social classes lead different lives. Research has shown that class differences may modulate individuals’ endorsement of egali-tarian (vs. meritocratic) social values (Kraus et al., 2012) and how they experience financial insecurity (Wiepking and Breeze, 2012), which in turn influence other-regarding behaviors. More recently, Côté et al. (2015) suggested that inequality perceptions moderate this rela-tionship, such that in economically unequal regions the difference in prosociality between the rich and the poor exacerbates. This finding sheds light on the importance of income concentration to the study of prosocial behavior and embodies Piff et al.’s (2010) appeal for further examination on how prosociality manifests itself in relatively extreme economic contexts. Nevertheless, the dearth of studies on the topic testifies to the lack of regard to the particularities of altruism on the opposite poles of the material basis, i.e., wealth and poverty.

on the antagonistic ends of the social class continuum. This dissertation offers four central contributions to theory and research on social class and prosocial behavior. First, we scruti-nize the hitherto open debate about whether and how social class influences one’s prosocial behaviors. Second, we broaden the understanding of prosociality in such debate by exam-ining a greater range of prosocial incidents. Third, contrary to most studies, that analyze prosociality among wealthy and educated populations from developed countries, we focus on the extremes of the socioeconomic distribution in a developing country. Lastly, we address some often neglected endogeneity issues by controlling for individuals’ resources and oppor-tunities to act prosocially. If people’s social relations are largely sorted on the basis of their social standing, then opportunities to perform determined prosocial behaviors should also vary as a function of their social class. Put differently, members of different social groups potentially perform different prosocial behaviors due to varying levels of exposition to social needs. Furthermore, if different social classes dispose different amounts of resources such as money or time, and prosociality is resource-contingent, then a spurious association between social class and prosocial behavior would be likely to emerge.

The Psychological Framework: Prosociality is Higher Among

the Poor

Social class embodies both an objective measure of one’s material resources (e.g., ed-ucational attainment, income, and occupational prestige) and the subjective perception of socioeconomic status rank vis-à-vis others in society (Piff et al., 2010). Similar to ethnicity and gender, social class is a source of social identity that ultimately influences one’s social-ization as well as patterns of construal. In fact, people use social class to categorize one another during social interactions (Blascovich et al., 2001) and spend a majority of their daily lives in environments sorted on the basis of social hierarchies (Kraus et al., 2012).

Differences across the social class spectrum are not circumscribed to the material basis, nevertheless. Occupying a higher or lower social stratum influences one’s cognition, social-ization, and emotional experience in ways that may eventually resonate in the prosocial preferences and behaviors. Abundant material and social resources buffer people against economic hardships, enable individuals to pursue their own goals independently of others, and ultimately increase one’s sense of control over life outcomes (Kraus et al., 2009; Lea and Webley, 2006; Stephens et al., 2007). According to Kluegel and Smith (1986), whereas lower social class individuals justify inequality in the United States on the basis of contextual factors such as life opportunities and the economic system holistically, those at the top of the

hierarchy resort largely to meritocratic explanations. Living in more unequal areas further increases rejection of meritocracy among low-income residents and bolsters adherence among their high-income counterparts (Newman et al., 2015). In addition, attributing success to internal causes in tandem with self-interested motives lead high social status individuals to hold heightened narcissistic tendencies (Piff, 2014) and to support economic inequality more frequently (Kraus and Callaghan, 2014). Concatenating these cognitive consequences into other-regarding outcomes, Vohs et al. (2006) suggested that money makes people feel self-sufficient and behave accordingly. In fact, throughout several experiments, mere reminders of money led individuals to prefer performing a myriad of activities alone and reduced their requests for help as well as helpfulness toward others.

Experiencing a self-sufficient orientation is also manifest in individuals’ patterns of so-cialization. The higher one climbs the social ladder, the more emphasis will be given to independence and personal control as opposed to interdependence and social adjustment (Na and Chan, 2016). According to Völker et al. (2007), the interdependence inherent to contexts of scarce resources highly predicts the emergence of cohesive communities. Indeed, when coping with perceptions of chaos – stemming from economic uncertainty, political in-stability, or family crisis –, lower-class individuals tend to give more priority to community relative to upper-class individuals, who instead tend to prioritize their material wealth (Piff et al., 2012b). Consistent with these findings, those with less resources rely more often on others to achieve their aspirations (Centers, 1949) and engage more deeply in social inter-actions (Kraus and Keltner, 2009; Scherer, 1974). This discrepancy in social engagement resonates in prosocial differences in two distinct ways. First, social proximity may enable one to be aware of others’ needs and get active solicitations to help, which are fundamental antecedents of prosociality (Bekkers and Wiepking, 2011). Second, feeling more closely con-nected to others is one natural consequence of social engagement and has been successively associated with other-regarding behaviors (Apicella et al., 2012; Branas-Garza et al., 2010; Nolin, 2010; Small and Simonsohn, 2008).

Finally, individuals from lower social echelons face harsher environments than their upper-class counterparts (Adler et al., 1994; Lareau, 2011) and these environments forge emotional experiences (Kraus et al., 2010a; Stellar et al., 2012). The circumstances under which lower-class individuals raise are marked by fewer educational opportunities (Snibbe and Markus, 2005), greater social threats such as stigmatization and ostracism (Williams, 2007), and heightened exposure to violence and health vulnerabilities that ultimately jeop-ardize mental stability as well as life expectancy (Gallo and Matthews, 2003; Sampson et al., 1997). With a myriad of threats to the self and a limited ability to use their scarce resources to buffer against these hurdles (Gallo et al., 2005), lower social class individuals become more

attuned to their social context and attentive to the needs of their peers (Kraus et al., 2011; Piff et al., 2010). This heightened motivation to understand others’ thoughts and feelings has been shown to increase neural activity in the brain regions associated with the mentalizing network and emotional salience (Muscatell et al., 2012).

The emotional aspect is dual in that lower class individuals both perceive and feel emo-tional stimuli to a greater extent than their higher-class counterparts. Tapping into the perceptual domain, Kraus et al. (2010b) experimentally manipulated individuals to feel ei-ther low status or high status; those in a lower position were more accurate at reading the emotions of others. Likewise, in the aftermath of an experimental assignment, participants in the low-status condition self-reported and presented physiological symptoms of heightened compassion for others (Stellar et al., 2012). Importantly, while the perception of holding less power endows people with a greater capacity for perspective taking and reciprocal emotional responses to another person’s suffering, magnified power perceptions serve as an impediment to experiencing empathy (Galinsky et al., 2006; Van Kleef et al., 2008). Connecting feelings and deeds, both the accurate perception of others’ emotional distress and the ability to take others’ perspective have been successively shown to influence prosocial behaviors in human as well as non-human samples (Bartal et al., 2011; Cigala et al., 2015; Marsh and Ambady, 2007; Marsh et al., 2007).

Overall, scholarly research has suggested that those with less resources hold more con-textual perspectives about the reasons for success, engage more deeply in social interactions with their peers, and experience emotions to a greater extent due to their heightened atten-tion to others’ suffering in specific and to environmental threats in general. These findings are synthesized in three patterns of interrelated differences across social classes: cognition, socialization, and emotion. These three strands of the literature compose the so-called psy-chological framework and give credence to the proposition that lower social class individuals act more prosocially than their higher social class counterparts.

The Economic Framework: Prosociality is Higher Among

the Rich

Towards an alternative to the psychological framework, an increasing body of research has advocated a positive relationship between social class and prosociality (e.g., Bekkers, 2003, 2006; Bekkers and Wiepking, 2006; Havens et al., 2006; Houston, 2006; Korndörfer et al., 2015; Rooney et al., 2005; Van Slyke and Brooks, 2005; Yen, 2002). The theoretical underpinnings of this "economic framework" revolve around one main concept: the marginal

utility derived from prosociality. Studies in neuroscience have demonstrated that performing prosocial behaviors such as reciprocal altruism and monetary donations activates reward-linked cerebral areas (Declerck et al., 2013; Fehr and Camerer, 2007; Moll et al., 2006; Rilling et al., 2002). Furthermore, prosocial spending (i.e., using one’s material resources to benefit others) is positively associated with a heightened level of happiness both for the benefactor and the target of the help (Aknin et al., 2013, 2012; Anik et al., 2009; Dunn et al., 2008, 2014; Martela and Ryan, 2015; Weinstein and Ryan, 2010). This mounting evidence reconciles the apparent paradox between prosociality and the economic canonical representation of individuals as self-interested agents who act rationally and seek to maximize their utility (e.g., Varian and Repcheck, 2010).

Within this self-interested rationale, individuals engage in cost-benefit mental accounts prior to performing any prosocial behavior. Since affluent individuals often dispose more resources than the required for a minimum standard of living, it is reasonable to believe that the higher one climbs the social ladder the lower will be the marginal utility of money. Thus, even when assuming that the benefits of donating are similar across social classes, affluent people would incur lower donation costs and, therefore, would achieve higher net utility results from prosociality. Consistent with this proposition, Andreoni et al. (2017) showed that when financial pressures loom larger, the rich behave more prosocially than the poor and this discrepancy is particularly due to the net utility derived from prosociality across the social spectrum.

Although the financial pressures one undergoes are important in explaining other-regarding behaviors, they capture only part of the costs associated with acting prosocially. Just as social class is experienced in objective as well as subjective terms, the costs of prosociality pertain to both the factual and the perceptual domains. According to Wiepking and Breeze (2012), regardless of the actual financial resources held by donors, the magnitude of their respective donations are influenced by their subjective approach to money. More precisely, when people are fearful of lacking money in the future or constantly worry about their finan-cial situation, they donate lower amounts to charity. Conversely, those who perceive their financial situation as more positive are also more generous donors, more likely to donate, and more likely to attend to charitable events (Bennett and Kottasz, 2000; Havens et al., 2006; Schlegelmilch et al., 1997).

In addition to the reduced costs associated with prosociality, those at the higher eche-lons also enjoy increased benefits from acting prosocially. Formal models and experimental economic studies indicate that opportunities for reputation formation generally play an im-portant role in promoting cooperation and prosocial behavior (Ernest-Jones et al., 2011; Haley and Fessler, 2005; Leimar and Hammerstein, 2001; Nettle et al., 2013; Oda et al.,

2011; Panchanathan and Boyd, 2004; Rigdon et al., 2009). According to Bekkers (2010), contributions to the collective good are rewarded with approval while refusing to contribute damages one’s reputation as a citizen. In fact, Bird and Power (2015) have shown that signalling prosocial intentions magnify one’s centrality in a given network. Thus, social classes should differ in prosociality when, ceteris paribus, (i ) one’s financial circumstances permit more substantial donations, and (ii ) one’s social standing engenders distinct pref-erences over reputation. While almost by definition higher class individuals dispose more resources to donate, Ostrower (1997) suggested that the wealthier also adapted philanthropy to a way of life that bolsters the cultural and social experiences of their class. Consistent with this rationale, prosocial spending stemming from the higher echelons is often personally publicized and extensively covered by the media (Weissmann, 2015). Furthermore, affluent individuals prefer to donate less frequently and "save up" for more impactful donations to charity (Schervish and Havens, 2003). Finally, people from higher social classes are more sensitive to reputation formation cues when compared their lower-class counterparts (Kraus and Callaghan, 2016), meaning that they potentially derive more utility from prosociality in public contexts.

The wealthy also enjoy greater benefits from taxes when compared to those with less resources (Bullock, 1996; Hay and Muller, 2014). This occurs for two main reasons. First, only a small portion of the total monetary donations are destined to those in need; instead this amount goes mainly to institutions important for the social and cultural life of the most affluent (Roberts, 1984; Surrey, 1970). Second, among those who opt for an itemized deduction for expenditures, each additional dollar donated to charity diminishes income tax liability by one times the marginal tax rate. Therefore, in countries where the income tax follows a progressive rate, those at the bottom of the social hierarchy would be penalized when compared to their higher-income counterparts. The impact of these tax-induced donation incentives are often measured by the elasticity of contributions as a function of the so-called ‘price’ of giving; i.e., the net cost to the taxpayer per dollar of giving (e.g., Clotfelter, 1980; Feldstein and Clotfelter, 1976; Feldstein and Taylor, 1976). Research has successively shown that price effects often increase with income (Auten et al., 1992; Duquette, 1999; O’Neil et al., 1996), and that tax regimes are important predictors of large-scale individual philanthropy, but not small-scale donations (Newland et al., 2010).

In sum, the economic framework represents the oppositional dichotomy of the psycho-logical approach. Within this rationale, higher social class individuals incur less costs and enjoy more benefits from prosociality. Altogether, a greater net utility, be it due to a pure or benefits-driven altruism, would lead higher social class individuals to act more prosocially than their lower-class counterparts. Across eight studies, Korndörfer et al. (2015) analyzed

several nation-wide surveys involving different types of prosocial behaviors to demonstrate such relationship. Accounting for the moderating effect of country, the authors showed that although some behaviors present nonsignificant differences with respect to social class, under no condition the purported negative effect between social standing and prosociality emerged. In sharp contrast with this economic proposition, Piff et al. (2010) conducted four studies using mostly university students to test whether lower social class individuals were more generous, charitable, trusting, and helpful than their upper-class counterparts. In addition to surveys, authors also conducted experimental studies to manipulate individuals’ subjec-tive perception of social class. Piff et al. (2010) not only confirmed their hypothesis that the poor are more prosocial than the rich, but also showed that the poor acted more prossocially due to their heightened commitment to egalitarian values and feelings of compassion.

Notwithstanding this clear-cut difference in findings – which per se reveals the need for further investigation –, the two traditions of research also bear some divergences in their empirical identification strategy. Research in psychology makes use of experiments, which on the one hand assure causality, but on the other hand lack external validity due to the exacerbated use of university samples. Research in the economic side, in turn, uses nation-wide representative samples but lacks internal validity due to its observational and generally cross-sectional analyses. Furthermore, economic studies often employ self-reported ques-tionnaires instead of measuring people’s actual behaviors. This is an important drawback because prosociality is a highly socially desirable activity and, therefore, a potential source of bias if not controlled for. Among the commonalities of these conflicting strands of research, we have the fact that (i ) both analyze an almost conventionalized few prosocial behaviors such as monetary donations and interpersonal trust; (ii ) do not take into account the poten-tial endogeneity stemming from the different levels of opportunities and resources available for prosociality across the social spectrum; and (iii ) are mostly conducted in developed countries, where poverty is not expressively pressing.

In the present dissertation, we address these issues in three different ways. First, we adopt both an inductive approach to assess representative prosocial behaviors to both social classes and a deductive approach to empirically test them. Second, we conduct surveys with a relatively large, non-university sample in a developing country to assure external validity. Third, we account for potentially biasing effects of social desirability, individual resources available for prosociality, and opportunities to help others. All in all, our empirical analysis capitalizes on the positive aspects of each strand of research while trying to avoid the common pitfalls both of them incur.

Overview of the Present Research

This dissertation examines the conflicting strands of research linking social class and prosocial behavior. In the first study, we conducted a series of focus groups in both wealthy and impoverished areas to understand how prosociality is operationalized in both contexts. This inductive approach allowed the emergence of different patterns of other-regarding be-haviors, subsequently used in the following studies. In the second study, we administered surveys in flow points of the same regions. This survey aimed to assess whether proso-cial behaviors differed across the soproso-cial spectrum in terms of nature and magnitude while controlling for the resources and opportunities available to both groups.

Study 1

Although the formal definition of prosocial behavior as being a voluntary act intended to benefit another (Eisenberg, 2006) encompasses a myriad of socially significant attitudes, research in the domain of social class has been circumscribed to an almost conventionalized few (e.g., monetary donations and measures of trust and generosity in experimental games; Piff et al., 2010). This practice largely ignores the fact that besides varying by level, prosocial behaviors might also vary by significance across the social spectrum. Put differently, indi-viduals from different social classes may be equally prosocial, but operationalize prosociality through distinct behaviors. By not taking this potential differences into account, scholarly research may unintentionally bias study results towards one group or the other. We con-ducted a series of focus groups to overcome these limitations and generate a vast array of significant prosocial behaviors to be used in subsequent studies.

Method

Focus groups represent one type of qualitative research that capitalizes on interpersonal communication to generate data concerning individual knowledge and experience (Kitzinger, 1995). As such, focus groups produce unique narratives that enable the researcher to identify and scrutinize shared knowledge within each group in a way that is both inductive and naturalistic (Bowling, 2014; Hughes and DuMont, 2002; Krueger, 2014). Thus, this method is particularly useful to identify how prosocial behaviors are operationalized across the different social echelons.

Participants. Fifty six individuals (27 men and 29 women) from both impoverished and wealthy areas of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, took part in six different focus groups. Higher

social class participants were undergraduate or MBA students from a private Brazilian uni-versity, segregated on the basis of gender. Lower social class participants, in contrast, were drawn from adjacent slums located in the same neighborhood and divided according to two criteria: gender and economic vulnerability level. Focus groups comprised a minimum of eight and a maximum of ten participants who ranged in age from 17 to 53 years old (M= 32). Participants from impoverished areas presented a median monthly household income of R$881-R$1,500, whereas in wealthy areas the same measure fell within the R$15,001-R$20,000 interval.

Procedure. Higher social class participants (n= 20) were recruited by university pro-fessors and discussions occurred in the university. Participants from lower social classes (n= 36), in contrast, were recruited by both local inhabitants and a non-governmental organi-zation (NGO) and discussions took place in the headquarters of such NGO. Upon arrival, participants individually filled a demographic questionnaire and were offered a snack to get acquainted with others. This was followed by the focus group discussion. To ensure that all discussions were conducted in a similar fashion, the moderator used a standard list of points that were to be addressed during the sessions. Individuals were probed with questions about the meaning of prosociality and how it was operationalized by them in particular as well as by their respective communities in general. Verbal protocols were tape recorded and infor-mants were repeatedly encouraged to externalize their personal and communal experiences. Upon completion of the discussion, individuals were thanked, paid, and debriefed.

Focus groups took from about 1:30 hour to 2 hours and all of the audio tapes were tran-scribed verbatim. Following Bergin et al. (2003), units of analysis within transcripts consisted of complete descriptions of prosocial behaviors. Therefore, we did not use elaborations on previously mentioned incidents.

Results and Discussion

Participants elaborated on fifty different types of prosocial behaviors and mentioned a total of 158 prosocial incidents (Table 1). Although monetary donations are the focus of studies on prosociality, they are not even among the ten most cited prosocial incidents. When we split the analysis by groups (i.e., men versus women and high versus low social class), monetary donations’ rank once again fell short from its representation in scholarly research. Interestingly, people not seldom buy products to help the seller and lend money and credit cards to others. This sheds light on the fact that in addition to neglecting the most significant prosocial behaviors, studies in prosociality also fail to include the majority of operationalizations regarding prosocial spending.

Social Class Similarities. Out of the 50 prosocial behaviors mentioned, 12 overlapped across social classes. This means that there is room for significant comparisons between social groups without biasing towards any of them. Two of these behaviors represented collective actions, which are quite contextual and were not used in our further analyses. Furthermore, lending money was incorporated to the donation concept and reprimanding negative attitudes or characteristics were dropped due to its rather abstract nature and difficulty to be considered a prosocial behavior. To the eight remaining behaviors (donating food, clothing, blood, money, medicines, taking care of someone’s children, helping someone carry the bags, and helping someone pack and move), we added five additional others that were mentioned at least by one of the groups but that are likely to be representative of both: donating books and toys, taking care of sick or injured people, giving up the place in the public transportation, helping someone get off the bus, and helping someone find a job. Thus, our object of analysis in the subsequent studies is composed of these 13 prosocial behaviors.

Social Class Differences. Since poor communities counted with a greater number of focus groups, comparisons between impoverished and wealthy groups should be interpreted cautiously. That being said, participants in the less affluent communities mentioned more types and more incidents of prosocial behaviors when compared to their affluent counterparts. Importantly, whereas only 9 out of the 50 mentioned behaviors were unique to the wealthy area, 29 were so to the impoverished region. This means that, apart from potential differences in the levels of prosociality, major differences in the manifestations of prosocial behaviors emerged. We test both types of differences in the next studies.

Study 2

In study 2, we capitalize on the wide range of significant prosocial behaviors collected in the first study to analyze the relationship between social class and prosocial behavior. To do so, we conducted surveys using thirteen out of the fifty items elaborated in the focus group discussions.1 Because the environments of rich and poor differ in a myriad of ways, we also measured and controlled for people’s resources and opportunities to behave prosocially.

1Donating food, donating clothing, donating blood, donating money, donating medicines, donating books and toys, taking care of others’ children, taking care of sick or injured people, carrying someone’s bags, helping someone pack and move, giving up the place in public transportation, helping someone to get off the bus, and helping someone to find a job.

Table 1: Number of Mentions per Prosocial Behavior

Method

Participants. We conducted 446 surveys in flow points of impoverished and wealthy areas of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (223 in each region). The South zone of Rio de Janeiro, and particularly the neighborhood of Leblon, which represents the majority of the sample, has the most expensive square footage in the country with household heads earning a monthly average income of R$11,632.50. Conversely, the neighborhood of Maré presents one of the worst Human Development Indexes (HDI) of the municipality and an average income of R$1,290.70 (i.e., roughly 10 % of the income of Leblon).2 Table 2 presents the descriptive

statistics of participants by region. As expected, there was a significant discrepancy in income and education. No significant differences between regions emerged in terms of gender and age, but wealthier areas counted a greater percentage of white people. As important, both groups differed on the measure of religiosity and social desirability, which suggests the need to control for these variables as they are also associated with prosociality.

2Land price information were collected from the Foundation Economic Research Institute (Fipe). HDI and income information were collected from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE).

Procedure. Participants were approached by research assistants and asked whether they would like to take part in an academic survey about interpersonal relationships. Those who agreed to participate were asked how frequently they performed each of the thirteen selected prosocial behaviors in the previous 12 months on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (not even once) to 5 (once a week). In case participants performed one specific type of prosocial behavior at least once in the previous year, they were asked in an open-question who was the target of the helping act.

To mitigate potential endogeneity problems associated with differing opportunities and resources available to each group, we collected information about these two aspects. Partic-ipants were asked how frequently they had the opportunity to perform each of the selected prosocial behaviors in the same five-point scale. In addition, respondents indicated the amount of resources available they had to perform the same prosocial behaviors. More specif-ically, they indicated whether they had the emotional, financial or time-related resources to help others using a four-point scale anchored by 1 (I would not have resources) and 4 (I would easily have resources). We randomized the order in which frequency, opportunities, and resources were presented to avoid fatigue or other order-related effects.

Since prosocial behavior information are self-reported and prosociality represents a highly desirable behavior, we also assess participants’ social desirability. Respondents filled a five-item social desirability scale adapted from Crowne and Marlowe (1960). In this scale, re-spondents were asked to indicate whether statements such as "I am always courteous, even to people who are disagreeable" were true or false. Results were summed to generate the social desirability measure. Finally, participants filled a demographic questionnaire, were thanked, and debriefed.

Measures of social class. We computed three different measures of social class in the present study. The first one inferred social class from the region in which the survey was conducted. We created a dummy coded one for impoverished areas and zero for wealthy areas. The second measure is a composite objective measure of social class composed of monthly household income per capita before taxes and years of formal education. More precisely, we standardized education and income separately and then averaged both measures across each respondent. The third, measure relates to the subjective aspect of social class. We asked participants to indicate the social standing of the family in which they grew on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (well below average) to 5 (well above average).

Table 2: Observable Characteristics of Wealthy and Impoverished Areas

Results and Discussion

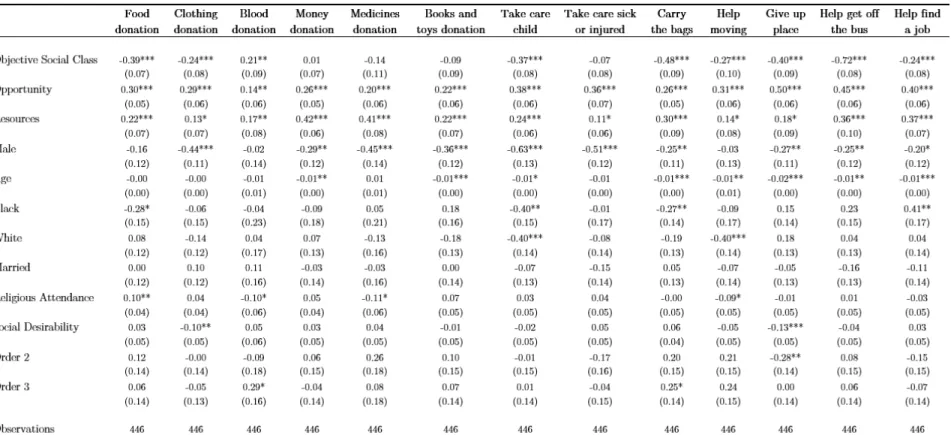

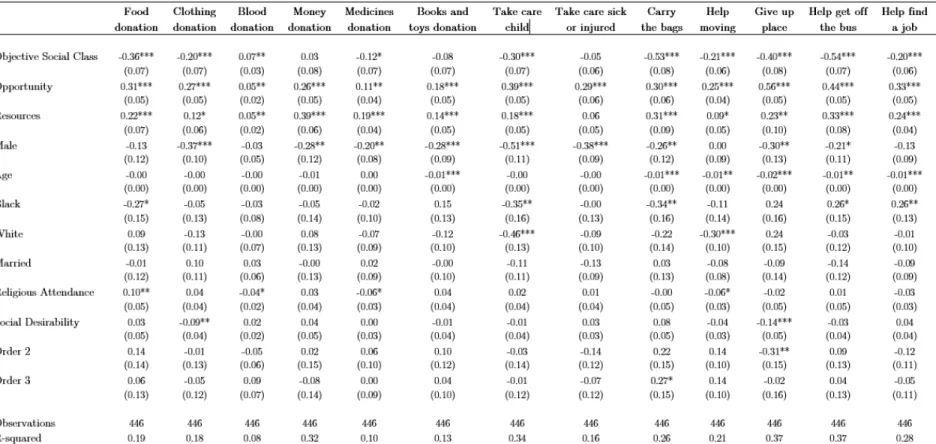

We performed a series of ordered probit regressions to assess the relationship between social class and prosocial behavior. As shown in table 3, the composite objective measure of social class is generally negatively associated with prosociality. Those with more resources donated less food, less clothing, and helped others less often in taking care of someone’s children, carrying someone’s bag, helping someone pack and move, giving up the place in public transportation, and helping someone to get off the bus. In contrast, the more affluent and educated donated more blood and money than their lower social class counterparts. No significant differences emerged for the following behaviors: taking care of sick or injured people, helping someone find a job, and donating books and toys, medicines, and money.

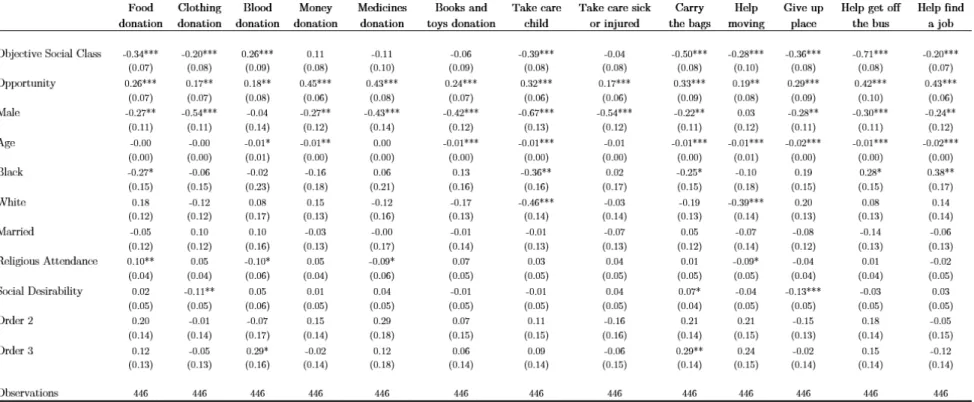

To mitigate potential endogeneity concerns, we controlled for opportunities and resources available for prosociality. Previous results showed that the poor give up their place in the public transportation and help others get off the bus more frequently than their higher class counterparts. Although this discrepancy could be attributed to differences in prosociality, we should also be able to rule out the alternative hypothesis that the poor simply do so because they use public transportation more often – and therefore have more opportunities to help – than upper-class individuals (Blumenberg and Pierce, 2012; Glaeser et al., 2008). Likewise, Andreoni et al. (2017) proposed that upper-class individuals would act more proso-cially than their lower-income counterparts, but this effect would vanish after controlling for the marginal utility of money. Although not necessarily true, high-income individuals are

more likely to have monetary resources available for prosociality. Furthermore, because phi-lanthropy is resource-contingent, a spurious relationship between social class and monetary donations may arise.

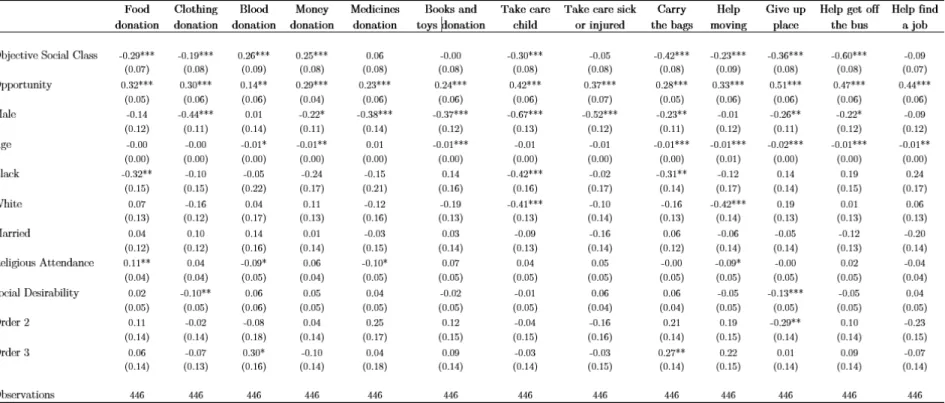

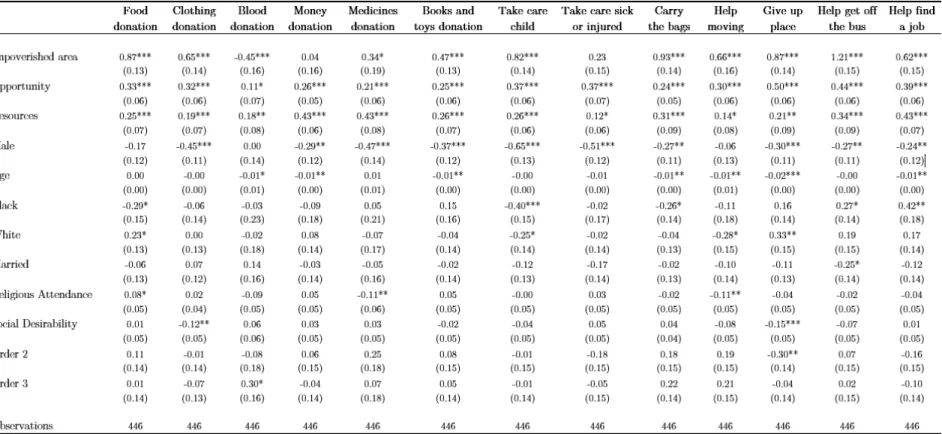

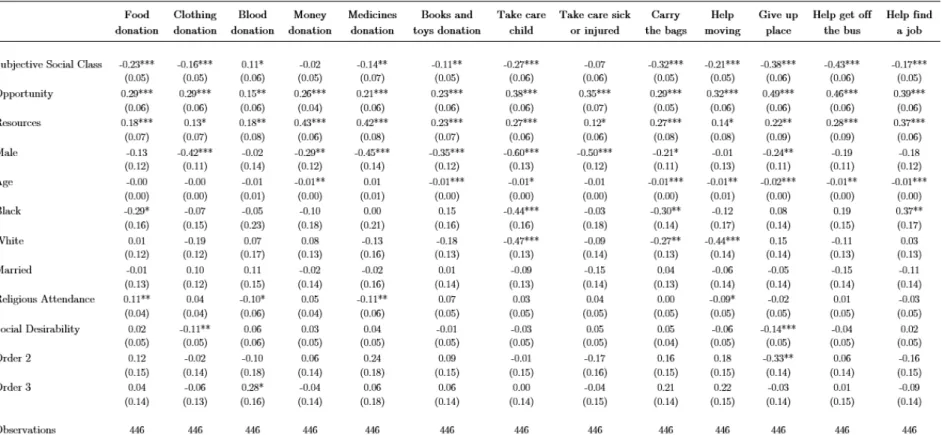

Controlling for resources, all behaviors except for donating money and helping someone find a job remained unaltered (see table 1A in the appendix). While donating money failed to reach significance (b = .11, p>.10), the poor helped others to find a job significantly more often than their upper-class counterparts (b = -.20, p<.01). As a next step, we controlled for opportunities to act prosocially. Results remained largely unaltered when compared to the first, "no control" analysis (table 2A). Finally, we performed a regression using both resources and opportunities as covariates (table 3). Again, donating money became nonsignificant (b = .01, p>.10) and helping someone find a job reached statistical significance (b = -.24, p<.01). Altogether, accounting for individuals’ resources and opportunities do not modify much the relationship between social class and prosociality.3 Nevertheless, our results were consistent

with Andreoni et al.’s (2017) hypothesis that differences in philanthropy across the social spectrum are due to differences in the marginal utility of money.

Results have, heretofore, corroborated the propositions of the psychological framework. Nevertheless, there are still some important alternative explanations to be ruled out. One of them refers to the fact that the poor are the main target of many prosocial behaviors (e.g., money and clothing donation). Furthermore, those who face poverty are more likely to hold a close relationship with others who go through the same situation. Thus, it could be the case that social class is not driving results, but rather the fact that the poor act on behalf of their in-group to a greater extent than the rich when it comes to prosocial behavior. To rule out this hypothesis, we analyzed the patters of help across all prosocial behaviors. We created five different categories of targets ((1) strangers, (2) acquaintances, neighbors, and friends, (3) relatives, (4) institutions, (5) others), coded the self-reported targets of past prosociality of each behavior by respondent, and computed how much each target represented as a percentage of all targets per region (see table 7A). A chi-square test revealed nonsignificant differences in the patterns of prosociality across the social spectrum (χ2 (4, N= 2654) = 7.15, p>.10).

3Results remain robust when we perform ordinary least squares regressions (refer to table 3A). Further-more, we have also ran these analyses using (i ) a dummy variable denoting each region and (ii ) a subjective measure of social class. In both cases, results remained largely unaltered (see tables 4A and 5A, respectively). Finally, the main analysis replaced age typos and the missing data from household income by the average values of the region under scrutiny. To rule out the hypothesis that these variables are driving the results, we reran this analysis by dropping these problematic observations. As shown in table 6A, results remained mostly unaltered.

Table 3: Effects of Objective Social Class on Prosocial Behavior (Ordered Probit Results)

Table 4: Effects of Objective Social Class on Prosocial Behavior Controlling for Resources and Opportunities (Ordered Probit Results)

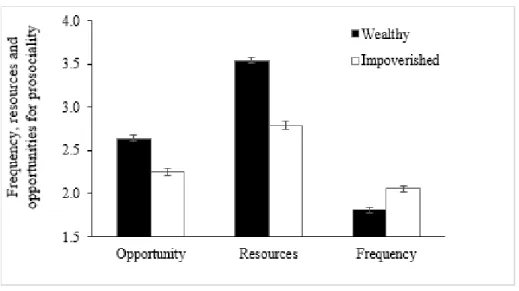

Finally, we capitalized on our rich database to assess the general patterns of prosociality among rich and poor taking into account their surrounding environments. More precisely, we averaged all the 13 behaviors with respect to the self-reported frequency, opportunity, and resources available for prosociality. All the three measures presented high reliability (αfrequency = .78, αopportunity= .80, αresources = .89) and were then used as dependent variables

in ordinary least squares regressions. For this analysis, we inferred social class by the region in which research was conducted: we used a dummy variable that takes on value 1 to denote an impoverished region and 0 otherwise. Results indicate that although the poor have less resources (b = -.78, p<.01) and less opportunities (b = -.35, p<.01) to help others, they do so significantly more frequently (b = .28, p<.01) than their wealthier counterparts (refer to table 8A for results). Put differently, although prosociality largely depends on resources and opportunities and both are smaller among the poor, when faced with the opportunity to help others, low-income individuals employ their already limited resources more frequently than the rich. Figure 1 pictorially shows such results.

Figure 1: Frequency, resources and opportunities for prosociality

Taken together, the results of Study 2 clearly reveal that lower social class individuals are more prosocial than their higher social class counterparts. Furthermore, the rich only donate more money than the poor when factors related to the net utility of money are not controlled for, which could be one important explanation for the conflicting findings in philanthropy across studies. The most notable exception to the psychological framework is blood donation, which is consistently higher among the rich. Finally, prosociality differences cannot be explained by a different pattern of targets of help, available opportunities to help, or even the resources one disposes to perform prosocial behaviors.

General Discussion

The concept of noblesse oblige establishes that the differential in privileges between the rich and the poor should be balanced by a differential in duties towards those in need. The empirical findings regarding which are the most prosocial groups have been as controversial as this assertive. Whereas research in the so-called psychological framework has advocated a negative relationship between social class and prosocial behavior (e.g., Kraus et al., 2012; Piff et al., 2010), literature in the economic framework has advocated the opposite (i.e., positive) direction to be true (e.g., Bekkers, 2010; Bekkers and Wiepking, 2006). In the present study we scrutinized these conflicting findings in two studies.

In the first study, we conducted a series of focus groups in both wealthy and impoverished areas. Results revealed that research in the domain of social class has been circumscribed to an almost conventionalized few prosocial behaviors (e.g., monetary donations and measures of trust and generosity in experimental games) that are not representative of neither wealthy nor poor individuals. In the second study, we conducted surveys in the same areas and results revealed that lower social class individuals are more prosocial than those at the top of the social hierarchy. One major exception to the psychological framework, however, is blood donation: lower income and less educated individuals donated less blood than their wealthier counterparts.

The economic framework has largely focused on prosociality as philanthropy. Andreoni et al. (2017) proposed that those with more resources would act more prosocially than their lower-income counterparts in general, but this effect would vanish after controlling for the net utility derived from prosociality. Consistent with these results, social class only influenced prosociality when the available resources one had were not taken into account. Put differently, discrepancies in prosociality only emerge when one does not control for the factors that determine the marginal utility of money. These results are particularly important for understanding the conflicting findings in the literature. More precisely, most of the studies in the economic framework use observational data, which hardly contains information or allows experimental manipulations of the marginal utility of money. Thus, some of the results in the area could be partially attributed to the fact that people derive different utilities from prosociality and this utility is not taken into account by observational studies.

Overall, findings shed light on the important fact that although the poor are the most needing of others help and have fewer resources to help others, they are the ones who help the most. In fact, results have shown that even though the rich have more resources available to help and more opportunities to do so in their daily lives, they perform prosocial behaviors less frequently than their less affluent counterparts. Furthermore, the poor and the rich hold

similar patterns of prosociality; i.e., there is no systematic differences between the targets of their helping behaviors. This rules out the potential explanation that is not social class that is driving results, but rather the fact that the poor act on behalf of their in-group to a greater extent than the rich when it comes to prosocial behavior. Altogether, results show that the poor are not necessarily more in-group oriented, have less resources and opportunities to help, but still help more often than their wealthier counterparts.

Implications and Limitations

This research bears important methodological and theoretical implications. Our results suggest that social desirability as well as resources and opportunities available to help others differ across social classes and also predict prosocial behavior. Not taking these differences into account would, therefore, likely bias research results. Indeed, even in experimental stud-ies, where the environment is considerably controlled, one would be able to solve inequalities in terms of opportunities and resources to help others, but not necessarily social desirabil-ity. Although behavioral measures of prosociality and distributive preferences mitigate these potential biasing effects, research is largely grounded on self-reported measures and attitude scales (e.g., Korndörfer et al., 2015). Thus, when using consequential dependent variables is not feasible, future research should at least account for these biasing, group-related charac-teristics.

From an organizational perspective, we embody Côté’s (2011) plea for further investiga-tion on how social class is manifest within the organizainvestiga-tional context. Precisely, future work on the relationship between social class and organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) is warranted to assess whether the patterns found in society at large are, in fact, the same as in the organizations. In case results are replicated, then those who should act as role models in terms of positive deviant behaviors are the ones who would be actually falling the most to do so. This is important because OCBs were shown to positively influence performance (Nielsen et al., 2009; Podsakoff et al., 1997) and, therefore, failing to behave accordingly would signal a potential path for improvement among the top management.

Three are the main limitations of this research. First, we used self-reported prosociality measures instead of actual behavior, and they do not necessarily coincide. This is particularly problematic in contexts where the dependent variable is highly socially desirable, which is the case of prosocial behavior. Nevertheless, we made some efforts to attenuate this problem by controlling for social desirability in our analyses. Furthermore, our results show that, despite the pitfalls of self-reported questionnaires, our studies captured individuals’ actual behaviors. As aforementioned, higher income and more educated individuals donated more blood than

heir lower social class counterparts, which is consistent with previous medical literature (e.g., Boulware et al., 2002; Gillespie and Hillyer, 2002; Shaz et al., 2008). Furthermore, male individuals were generally less prosocial than female individuals, which is also corroborated by the literature on gender and prosociality (e.g., Mesch et al., 2011; Piper and Schnepf, 2008).

Second, sample is non-probabilistic, which potentially generates selection biases. This is because those reachable in flow points may be different from the population at large. Furthermore, those who refused to participate once approached may be less prosocial than the ones who actually responded to the survey, which would cause an upward bias in our estimates. Although cognizant of these limitations, the potential biases arising from non-probabilistic sampling are likely to occur in similar ways for rich and poor individuals and, therefore, would not generate alternative explanations for our results.

Finally, because social class is related to a myriad of other social factors, causality is far from granted in the present research. Further investigation on the issue manipulating participants’ subjective perception of social class should clearly be undertaken so as to assure that social class is, in fact, the driving force of the observed discrepancies in prosociality.

Conclusion

Social class is not circumscribed to the material basis one holds; it represents a major social context in which individuals navigate in enduring and pervasive ways over their life course (Kraus et al., 2012). This article sought to disentangle conflicting findings from two different strands of the literature on social class and prosocial behavior: the psychological framework and the economic framework. We have shown that the less affluent, despite having less resources and opportunities to help others, act more prosocially than their upper-class counterparts. Furthermore, although prosociality is a concept that encompasses a wide vari-ety of actions, research has used a conventionalized few behaviors that are not representative neither of the rich nor of the poor. Future research should build on these findings to further understand how disparities in social class modulate individuals’ prosociality and to devise new ways of increasing other-regarding behaviors among the rich.

References

Adler, N. E., Boyce, T., Chesney, M. A., Cohen, S., Folkman, S., Kahn, R. L., and Syme, S. L. (1994). Socioeconomic status and health: the challenge of the gradient. American psychologist, 49(1):15.

Aknin, L. B., Barrington-Leigh, C. P., Dunn, E. W., Helliwell, J. F., Burns, J., Biswas-Diener, R., Kemeza, I., Nyende, P., Ashton-James, C. E., and Norton, M. I. (2013). Prosocial spending and well-being: Cross-cultural evidence for a psychological universal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4):635.

Aknin, L. B., Dunn, E. W., and Norton, M. I. (2012). Happiness runs in a circular motion: Evidence for a positive feedback loop between prosocial spending and happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(2):347–355.

Andreoni, J., Nikiforakis, N., and Stoop, J. (2017). Are the rich more selfish than the poor, or do they just have more money? a natural field experiment. NBER Working Papers 23229, National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Anik, L., Aknin, L. B., Norton, M. I., and Dunn, E. W. (2009). Feeling good about giving: The benefits (and costs) of self-interested charitable behavior.

Apicella, C. L., Marlowe, F. W., Fowler, J. H., and Christakis, N. A. (2012). Social networks and cooperation in hunter-gatherers. Nature, 481(7382):497–501.

Auten, G. E., Cilke, J. M., and Randolph, W. C. (1992). The effects of tax reform on charitable contributions. National Tax Journal, 45(3):267–290.

Bartal, I. B.-A., Decety, J., and Mason, P. (2011). Empathy and pro-social behavior in rats. Science, 334(6061):1427–1430.

Bekkers, R. (2003). Trust, accreditation, and philanthropy in the netherlands. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 32(4):596–615.

Bekkers, R. (2006). Traditional and health-related philanthropy: The role of resources and personality. Social psychology quarterly, 69(4):349–366.

Bekkers, R. (2010). Who gives what and when? a scenario study of intentions to give time and money. Social Science Research, 39(3):369–381.

Bekkers, R. and Wiepking, P. (2006). To give or not to give, that is the question: How methodology is destiny in dutch giving data. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 35(3):533–540.

Bekkers, R. and Wiepking, P. (2011). A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: Eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40(5):924–973.

Benenson, J. F., Pascoe, J., and Radmore, N. (2007). Children’s altruistic behavior in the dictator game. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28(3):168–175.

Bennett, R. and Kottasz, R. (2000). Emergency fund-raising for disaster relief. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, 9(5):352–360.

Bergin, C., Talley, S., and Hamer, L. (2003). Prosocial behaviours of young adolescents: a focus group study. Journal of adolescence, 26(1):13–32.

Bird, R. B. and Power, E. A. (2015). Prosocial signaling and cooperation among martu hunters. Evolution and Human Behavior, 36(5):389–397.

Blascovich, J., Mendes, W. B., Hunter, S. B., Lickel, B., and Kowai-Bell, N. (2001). Perceiver threat in social interactions with stigmatized others. Journal of personality and social psychology, 80(2):253.

Blumenberg, E. and Pierce, G. (2012). Automobile ownership and travel by the poor: Ev-idence from the 2009 national household travel survey. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, (2320):28–36.

Boulware, L., Ratner, L., Ness, P., Cooper, L., Campbell-Lee, S., LaVeist, T., and Powe, N. (2002). The contribution of sociodemographic, medical, and attitudinal factors to blood donation among the general public. Transfusion, 42(6):669–678.

Bowling, A. (2014). Research methods in health: investigating health and health services. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

Branas-Garza, P., Cobo-Reyes, R., Espinosa, M. P., Jiménez, N., Kovářík, J., and Ponti, G. (2010). Altruism and social integration. Games and Economic Behavior, 69(2):249–257. Bullock, A. G. (1996). Taxes, social policy and philanthropy: The untapped potential of

middle-and low-income generosity. Cornell JL & Pub. Pol’y, 6:325. Centers, R. (1949). The psychology of social classes.

Chen, Y., Zhu, L., and Chen, Z. (2013). Family income affects children’s altruistic behavior in the dictator game. PloS one, 8(11):e80419.

Cigala, A., Mori, A., and Fangareggi, F. (2015). Learning others’ point of view: perspec-tive taking and prosocial behaviour in preschoolers. Early Child Development and Care, 185(8):1199–1215.

Clotfelter, C. T. (1980). Tax incentives and charitable giving: Evidence from a panel of taxpayers. Journal of Public Economics, 13(3):319–340.

Côté, S. (2011). How social class shapes thoughts and actions in organizations. Research in organizational behavior, 31:43–71.

Côté, S., House, J., and Willer, R. (2015). High economic inequality leads higher-income individuals to be less generous. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(52):15838–15843.

Crowne, D. P. and Marlowe, D. (1960). A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of consulting psychology, 24(4):349.

Declerck, C. H., Boone, C., and Emonds, G. (2013). When do people cooperate? the neuroeconomics of prosocial decision making. Brain and cognition, 81(1):95–117.

Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., and Norton, M. I. (2008). Spending money on others promotes happiness. Science, 319(5870):1687–1688.

Dunn, E. W., Aknin, L. B., and Norton, M. I. (2014). Prosocial spending and happiness using money to benefit others pays off. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(1):41–47. Duquette, C. M. (1999). Is charitable giving by nonitemizers responsive to tax incentives?

new evidence. National Tax Journal, pages 195–206.

Durkheim, E. (2014). The division of labor in society. Simon and Schuster.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., and Spinrad, T. (2006). Handbook of child psychology, volume 3. John Wiley & Sons Hoboken, NJ.

Ernest-Jones, M., Nettle, D., and Bateson, M. (2011). Effects of eye images on everyday cooperative behavior: a field experiment. Evolution and Human Behavior, 32(3):172–178. Fehr, E. and Camerer, C. F. (2007). Social neuroeconomics: the neural circuitry of social

preferences. Trends in cognitive sciences, 11(10):419–427.

Feldstein, M. and Clotfelter, C. (1976). Tax incentives and charitable contributions in the united states: A microeconometric analysis. Journal of Public Economics, 5(1-2):1–26. Feldstein, M. and Taylor, A. (1976). The income tax and charitable contributions.

Econo-metrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, pages 1201–1222.

Galinsky, A. D., Magee, J. C., Inesi, M. E., and Gruenfeld, D. H. (2006). Power and perspectives not taken. Psychological science, 17(12):1068–1074.

Gallo, L. C., Bogart, L. M., Vranceanu, A.-M., and Matthews, K. A. (2005). Socioeconomic status, resources, psychological experiences, and emotional responses: a test of the reserve capacity model. Journal of personality and social psychology, 88(2):386.

Gallo, L. C. and Matthews, K. A. (2003). Understanding the association between socioeco-nomic status and physical health: do negative emotions play a role? Psychological bulletin, 129(1):10.

Gillespie, T. W. and Hillyer, C. D. (2002). Blood donors and factors impacting the blood donation decision. Transfusion Medicine Reviews, 16(2):115–130.

Gittell, R. and Tebaldi, E. (2006). Charitable giving: Factors influencing giving in us states. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 35(4):721–736.

Glaeser, E. L., Kahn, M. E., and Rappaport, J. (2008). Why do the poor live in cities? the role of public transportation. Journal of urban Economics, 63(1):1–24.

Haley, K. J. and Fessler, D. M. (2005). Nobody’s watching?: Subtle cues affect generosity in an anonymous economic game. Evolution and Human behavior, 26(3):245–256.

Havens, J. J., O’Herlihy, M. A., and Schervish, P. G. (2006). Charitable giving: How much, by whom, to what, and how. The nonprofit sector: A research handbook, 2:542–567. Hay, I. and Muller, S. (2014). Questioning generosity in the golden age of philanthropy:

Towards critical geographies of super-philanthropy. Progress in Human Geography, 38(5):635–653.

Hayek, F. A. (2012). Law, legislation and liberty: a new statement of the liberal principles of justice and political economy. Routledge.

Houston, D. J. (2006). “walking the walk” of public service motivation: Public employees and charitable gifts of time, blood, and money. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 16(1):67–86.

Hughes, D. L. and DuMont, K. (2002). Using focus groups to facilitate culturally anchored research. In Ecological research to promote social change, pages 257–289. Springer. James, R. N. and Sharpe, D. L. (2007). The nature and causes of the u-shaped charitable

giving profile. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 36(2):218–238.

Kitzinger, J. (1995). Qualitative research. introducing focus groups. BMJ: British medical journal, 311(7000):299.

Kluegel, J. R. and Smith, E. R. (1986). Beliefs about inequality: Americans’ views of what is and what ought to be. Transaction Publishers.

Korndörfer, M., Egloff, B., and Schmukle, S. C. (2015). A large scale test of the effect of social class on prosocial behavior. PloS one, 10(7):e0133193.

Kraus, M. W. and Callaghan, B. (2014). Noblesse oblige? social status and economic inequality maintenance among politicians. PloS one, 9(1):e85293.

Kraus, M. W. and Callaghan, B. (2016). Social class and prosocial behavior: The moder-ating role of public versus private contexts. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 7(8):769–777.

Kraus, M. W., Côté, S., and Keltner, D. (2010a). Social class, contextualism, and empathic accuracy. Psychological Science.

Kraus, M. W., Côté, S., and Keltner, D. (2010b). Social class, contextualism, and empathic accuracy. Psychological Science.

Kraus, M. W., Horberg, E., Goetz, J. L., and Keltner, D. (2011). Social class rank, threat vigilance, and hostile reactivity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(10):1376– 1388.

Kraus, M. W. and Keltner, D. (2009). Signs of socioeconomic status a thin-slicing approach. Psychological Science, 20(1):99–106.

Kraus, M. W., Piff, P. K., and Keltner, D. (2009). Social class, sense of control, and social explanation. Journal of personality and social psychology, 97(6):992.

Kraus, M. W., Piff, P. K., Mendoza-Denton, R., Rheinschmidt, M. L., and Keltner, D. (2012). Social class, solipsism, and contextualism: how the rich are different from the poor. Psychological review, 119(3):546.

Krueger, R. A. (2014). Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. Sage publica-tions.

Lareau, A. (2011). Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. Univ of California Press. Lea, S. E. and Webley, P. (2006). Money as tool, money as drug: The biological psychology

of a strong incentive. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 29(02):161–209.

Lee, Y.-K. and Chang, C.-T. (2007). Who gives what to charity? characteristics affecting donation behavior. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 35(9):1173– 1180.

Leimar, O. and Hammerstein, P. (2001). Evolution of cooperation through indirect reci-procity. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 268(1468):745– 753.

Marsh, A. A. and Ambady, N. (2007). The influence of the fear facial expression on prosocial responding. Cognition and Emotion, 21(2):225–247.

Marsh, A. A., Kozak, M. N., and Ambady, N. (2007). Accurate identification of fear facial expressions predicts prosocial behavior. Emotion, 7(2):239.

Martela, F. and Ryan, R. M. (2015). The benefits of benevolence: Basic psychological needs, beneficence, and the enhancement of well-being. Journal of personality.

Marx, K., Engels, F., and Moore, S. (1959). The communist manifesto, volume 6008. New York Labor News Company.

Mesch, D. J., Brown, M. S., Moore, Z. I., and Hayat, A. D. (2011). Gender differences in charitable giving. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 16(4):342–355.

Moll, J., Krueger, F., Zahn, R., Pardini, M., de Oliveira-Souza, R., and Grafman, J. (2006). Human fronto–mesolimbic networks guide decisions about charitable donation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 103(42):15623–15628.

Muscatell, K. A., Morelli, S. A., Falk, E. B., Way, B. M., Pfeifer, J. H., Galinsky, A. D., Lieberman, M. D., Dapretto, M., and Eisenberger, N. I. (2012). Social status modulates neural activity in the mentalizing network. Neuroimage, 60(3):1771–1777.

Na, J. and Chan, M. Y. (2016). Subjective perception of lower social-class enhances response inhibition. Personality and Individual Differences, 90:242–246.

Nettle, D., Harper, Z., Kidson, A., Stone, R., Penton-Voak, I. S., and Bateson, M. (2013). The watching eyes effect in the dictator game: it’s not how much you give, it’s being seen to give something. Evolution and Human Behavior, 34(1):35–40.

Newland, K., Terrazas, A., and Munster, R. (2010). Diaspora philanthropy: Private giving and public policy. Migration Policy Institute Washington, DC.

Newman, B. J., Johnston, C. D., and Lown, P. L. (2015). False consciousness or class awareness? local income inequality, personal economic position, and belief in american meritocracy. American Journal of Political Science, 59(2):326–340.

Nielsen, T. M., Hrivnak, G. A., and Shaw, M. (2009). Organizational citizenship behavior and performance: A meta-analysis of group-level research. Small Group Research, 40(5):555– 577.

Nolin, D. A. (2010). Food-sharing networks in lamalera, indonesia. Human Nature, 21(3):243–268.

Oda, R., Niwa, Y., Honma, A., and Hiraishi, K. (2011). An eye-like painting enhances the expectation of a good reputation. Evolution and Human Behavior, 32(3):166–171.

O’Neil, C. J., Steinberg, R. S., and Thompson, G. R. (1996). Reassessing the tax-favored status of the charitable deduction for gifts of appreciated assets. National Tax Journal, pages 215–233.

Ostrower, F. (1997). Why the wealthy give: The culture of elite philanthropy. Princeton University Press.

Panchanathan, K. and Boyd, R. (2004). Indirect reciprocity can stabilize cooperation without the second-order free rider problem. Nature, 432(7016):499–502.

Piff, P. K. (2014). Wealth and the inflated self class, entitlement, and narcissism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(1):34–43.

Piff, P. K., Kraus, M. W., Côté, S., Cheng, B. H., and Keltner, D. (2010). Having less, giving more: the influence of social class on prosocial behavior. Journal of personality and social psychology, 99(5):771.

Piff, P. K., Stancato, D. M., Côté, S., Mendoza-Denton, R., and Keltner, D. (2012a). Higher social class predicts increased unethical behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(11):4086–4091.

Piff, P. K., Stancato, D. M., Martinez, A. G., Kraus, M. W., and Keltner, D. (2012b). Class, chaos, and the construction of community. Journal of personality and social psychology, 103(6):949.

Piper, G. and Schnepf, S. V. (2008). Gender differences in charitable giving in great britain. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 19(2):103–124. Podsakoff, P. M., Ahearne, M., and MacKenzie, S. B. (1997). Organizational citizenship behavior and the quantity and quality of work group performance. Journal of applied psychology, 82(2):262–269.

Rawls, J. (2009). A theory of justice. Harvard university press.

Rigdon, M., Ishii, K., Watabe, M., and Kitayama, S. (2009). Minimal social cues in the dictator game. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(3):358–367.

Rilling, J. K., Gutman, D. A., Zeh, T. R., Pagnoni, G., Berns, G. S., and Kilts, C. D. (2002). A neural basis for social cooperation. Neuron, 35(2):395–405.

Roberts, R. D. (1984). A positive model of private charity and public transfers. Journal of Political Economy, 92(1):136–148.

Rooney, P. M., Mesch, D. J., Chin, W., and Steinberg, K. S. (2005). The effects of race, gender, and survey methodologies on giving in the us. Economics Letters, 86(2):173–180. Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S. W., and Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime:

A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277(5328):918–924. Sandel, M. J. (2010). Justice: What’s the right thing to do? Macmillan.

Scherer, S. E. (1974). Proxemic behavior of primary school children as a function of their so-cioeconomic class and subculture. Journal of personality and social psychology, 29(6):800. Schervish, P. G. and Havens, J. J. (2003). New findings on the patterns of wealth and

philanthropy. Social Welfare Research Institute, Chestnut Hill.

Schlegelmilch, B. B., Love, A., and Diamantopoulos, A. (1997). Responses to different charity appeals: the impact of donor characteristics on the amount of donations. European Journal of Marketing, 31(8):548–560.

Shaz, B. H., Zimring, J. C., Demmons, D. G., and Hillyer, C. D. (2008). Blood donation and blood transfusion: special considerations for african americans. Transfusion medicine reviews, 22(3):202–214.

Small, D. A. and Simonsohn, U. (2008). Friends of victims: Personal experience and prosocial behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 35(3):532–542.

Snibbe, A. C. and Markus, H. R. (2005). You can’t always get what you want: educational attainment, agency, and choice. Journal of personality and social psychology, 88(4):703.

Stellar, J. E., Manzo, V. M., Kraus, M. W., and Keltner, D. (2012). Class and compassion: socioeconomic factors predict responses to suffering. Emotion, 12(3):449.

Stephens, N. M., Markus, H. R., and Townsend, S. S. (2007). Choice as an act of meaning: the case of social class. Journal of personality and social psychology, 93(5):814.

Surrey, S. S. (1970). Tax incentives as a device for implementing government policy: a comparison with direct government expenditures. Harvard Law Review, pages 705–738. Van Kleef, G. A., Oveis, C., Van Der Löwe, I., LuoKogan, A., Goetz, J., and Keltner, D.

(2008). Power, distress, and compassion: Turning a blind eye to the suffering of others. Psychological science, 19(12):1315–1322.

Van Slyke, D. M. and Brooks, A. C. (2005). Why do people give? new evidence and strategies for nonprofit managers. The american review of public administration, 35(3):199–222. Varian, H. R. and Repcheck, J. (2010). Intermediate microeconomics: a modern approach,

volume 6. WW Norton & Company New York.

Vohs, K. D., Mead, N. L., and Goode, M. R. (2006). The psychological consequences of money. science, 314(5802):1154–1156.

Völker, B., Flap, H., and Lindenberg, S. (2007). When are neighbourhoods communities? community in dutch neighbourhoods. European Sociological Review, 23(1):99–114.

Wang, L. and Murnighan, J. K. (2014). Money, emotions, and ethics across individuals and countries. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(1):163–176.

Weber, M. (2009). The theory of social and economic organization. Simon and Schuster. Weinstein, N. and Ryan, R. M. (2010). When helping helps: autonomous motivation for

prosocial behavior and its influence on well-being for the helper and recipient. Journal of personality and social psychology, 98(2):222.

Weissmann, J. (2015). Billionaire’s ego donates $400 million to harvard.

Wiepking, P. and Breeze, B. (2012). Feeling poor, acting stingy: The effect of money perceptions on charitable giving. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 17(1):13–24.

Williams, K. D. (2007). Ostracism. Annu. Rev. Psychol., 58:425–452.

Wilson, J. and Musick, M. (1998). The contribution of social resources to volunteering. Social Science Quarterly, pages 799–814.

Yen, S. T. (2002). An econometric analysis of household donations in the usa. Applied Economics Letters, 9(13):837–841.

Appendix

Table 1A: Effects of Objective Social Class on Prosocial Behavior Controlling for Resources (Ordered Probit Results)

Table 2A: Effects of Objective Social Class on Prosocial Behavior Controlling for Opportunities (Ordered Probit Results)

Table 3A: Effects of Objective Social Class on Prosocial Behavior Controlling for Resources and Opportunities (Ordinary Least Squares Results)

Table 4A: Effects of Region Dummy on Prosocial Behavior Controlling for Resources and Opportunities (Ordered Probit Results)

Table 5A: Effects of Subjective Social Class on Prosocial Behavior Controlling for Resources and Opportunities (Ordered Probit Results)

Table 6A: Effects of Objective Social Class on Prosocial Behavior Excluding Typos and Missing Values (Ordered Probit Results)

Table 7A: Distribution of Targets of Prosociality per Region (%)

Table 8A: Effects of Region Dummy on Frequency, Opportunity, and Resources Available for Prosociality (Ordinary Least Squares Results)