Neoproterozoic glacial dynamics revealed by provenance of diamictites of the

Bebedouro Formation, S˜ao Francisco Craton: Northeasthern, Brazil

Felipe Torres Figueiredo, 3 Renato Paes de Almeida, 1 Eric Tohver, 2 Marly Babinski, 3 Duniy Liu, 4 Christofer Mark Fanning, 5

1 Departamento de Geologia Sedimentar e Ambiental, Instituto de Geociˆencias, Universidade de S˜ao Paulo. Rua do Lago 562, Cidade Universit´aria, S˜ao Paulo, 05508-900-SP, Brazil.

2 School of Earth and Geographical Earth Sciences, University of Western Australia. 33rd Stirling Highway, Crawley, 6009 -WA, Australia.

3 Departamento de Mineralogia e Geotectˆonica, Instituto de Geociˆencias, Universidade de S˜ao Paulo. Rua do Lago 562, Cidade Universit´aria, S˜ao Paulo, 05508-900-SP, Brazil.

4 Beijing SHRIMP Laboratory, Beijing, China.

5 Research School of Earth Sciences, The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia

Abstract

Provenance analysis of diamictites is an important tool in the study of glacial dynamics which is still rarely applied to Neoproterozoic glacial successions. Our work presents new data on clast composition, point counting in thin section and SHRIMP dating of pebbles and detritic zircon from the Bebedouro Formation, which records a Neoproterozoic glaci-ation (probably the Sturtian event) in the northern S˜ao Francisco Craton, Northeastern Brazil. The Bebedouro Formation comprises glaciomarine deposits that are lateral

equiva-lents to the Jequita´ı Formation on the southern region of the craton and to the Maca´ubas

lithologies that crop out in the nearby basement strongly suggest east and southward sedi-ment transport, although the presence of far-traveled clasts, indicated by a monzogranite pebble of 2627.3±20 Ma, suggests that the original area of the basin extended at least 200 km to the East, where icebergs could raft clasts from the opposite basin margin. Major detrital zircon ages reveal provenance from the archean basement of the craton, as well as a minor population of paleoproterozoic age, probably reworked from the Espinha¸co Super-group quartzites. The occurrence of detrital zircons of Neoproterozoic age from outside the craton corroborates the hypothesis of ice-rafting through great distances and constrains the minimum age of these deposits to 850 Ma.

Keywords

Neoproterozoic, glacial deposits, provenance analysis, Brazil, Bebedouro Formation.

Introduction

Since the rebirth of the hypothesis of global-scale glaciation during the Neoproterozoic (Harland and Bidgood, 1959, Harland, 1964, Kirschvink, 1992; Hoffman et al., 1998), several models have been proposed for the development of Neoproterozoic glacial deposits and post-glacial carbonate successions that are found in all continents (e.g. Hyde et al., 2000, Hoffman and Schrag, 2002; Eyles and Januszczak, 2004). In the first decade of intense research, most of the field evidence to support the models came from the post-glacial carbonates, with vast documentation of anomalous sedimentary structures and isotopic signatures of the cap-carbonates of several successions worldwide (e.g. Kennedy, 1996; Hoffman et al.,1998; Allen and Hoffman, 2005; Corsetti and Grotzinger, 2005; Halverson et al., 2005; Kaufman et al., 2006; Azmy et al., 2006). More recently, some questions have been raised on whether all the Neoproterozoic diamictite-bearing successions are indeed the record of glaciation (e.g. Eyles and Januszczak, 2004). As a consequence, there is now a renewed effort to document the detailed sedimentology of those successions (e.g. Arnaud and Eyles, 2006; Shields et al., 2007; Williams et al., 2008; Corkoran, 2008) and to establish a geochronological basis for the correlation of glacial deposits of different regions (e.g. Fanning and Link, 2004; Hoffman et al., 2004 Condon et al., 2005; Babinski et al. 2007; Bowring et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2008).

2006; Frimmel et al., 2006; Corkoran, 2008). The hypothesis of global ice cover (e.g. Wil-liams et al., 1998, Sohl et al., 1999) and its derivations (Hyde et al., 2000; WilWil-liams et al., 1998, 2000), would imply in great ice sheets covering the continents and ice shelves over the contiguous oceans. These ice sheets would promote large-scale erosion and the transport of sediment over great distances, particularly in ice streams (e.g. Dredge, 2000). On the other hand, some models consider the influence of the topography of the shoulders of rift systems in the origin of the glaciers that fed the Neoproterozoic basins (e.g. Prave, 1999; Labotka et al., 2000; Eyles and Januszczak, 2004, 2007; Eyles et al., 2007). If that is the case, one could expect distinct bedrock lithologies in each of the several individual valley glaciers that fed the basin. Thus, the provenance of the glacial and glacially influenced sediments would indicate a strong variation of sources from area to area in the same basin. Therefore, the analysis of the clastic provenance of Neoproterozoic diamictites can be used to test the models on glacier type and areal extension.

This work presents the results of clastic provenance analysis of the Neoproterozoic diamictites of the Bebedouro Formation of Northeastern Brazil, based on the recognition of the areal variability of pebble and cobble lithotypes and point-counting in thin sections. Samples were collected on the same stratigraphic level over an area of more than 16,000

km2. The results are integrated with new U-Pb SHRIMP zircon age data for pebbles and

detritic zircon in order to interpret the proximity and variability of the sources of glacial sediment and to reconstruct the style of the related glaciers.

Geological Framework

The S˜ao Francisco Craton, in northeastern Brazil, is a stable region preserved from the Neoproterozoic Braziliano orogenic collage during the assemblage of the Gondwana Supercontinent, presenting a vast sedimentary cover of Neoproterozoic age with incipient metamorphism and very weak deformation (Almeida, 1967). These Neoproterozoic succes-sions compose the S˜ao Francisco Supergroup, which also includes some of the correlative successions that are deformed and metamorphosed in the fold-belts that border the cra-ton. The Supergroup includes deposits from the rift and thermal subsidence (both passive margins and contiguous intracratonic basins) phases of the S˜ao Francisco plate, prior to the Neoproterozoic orogenic collage (Martins-Neto et al., 2001).

and Hoppe, 1998) (Fig.1). On the Craton, the unit reaches a maximum thickness of 70 m, but is often less than 40 m thick. Despite this limited thickness, correlative successions with more than 100 m occur from the central to the northernmost regions of the craton, as well as in the Ara¸cua´ı foldbelt to the east. Isolated occurrences, preserved mainly in opened, kilometer-scale synclinal folds, are found over an area of more than 900 x 400 km, elongated in the north-south direction. Besides the clear lithologic similarities and the glacial influence, correlation is corroborated by the equivalence of the stratigraphic position of those successions, which are positioned above a major unconformity, usually over Mesoproterozoic successions of the Espinha¸co Supergroup, and bellow Neoproterozoic carbonates of the Bambu´ı Group and the equivalent Una Group (Misi and Veizer, 1998; Misi et al., 2007). Because of their great area of exposure, the glacially-influenced units have local lithostratigraphic designations. In the central region of the S˜ao Francisco Craton they are termed Jequita´ı Formation, while in the Ara¸cua´ı Fold Belt they are included

in the Maca´ubas Group (Uhlein et al., 1998, 1999, Martins-Neto, 1999; Cukrov et al.,

2005) and in the northern region of the Craton they are termed Bebedouro Formation (Oliveira and Leonardos, 1940; Inda and Barbosa, 1978; Guimar˜aes, 1996). Regarding their tectonic setting, these successions have been interpreted as the record of a rift phase at the base of the S˜ao Francisco Basin (Uhlein et al., 1998; Martins-Neto et al., 1999), as intracratonic deposits of unclear tectonic setting (Inda and Barbosa, 1978; Dominguez, 1993; Dominguez, 1996), or as the base of a foreland basin (Martins-Neto et al., 2001) of the continental collision recorded in the Bras´ılia Fold Belt to the west (which is although younger than the diamictite – carbonate succession).

In the studied region, in the northern S˜ao Francisco Craton, the S˜ao Francisco Super-group is represented by the Una Group, composed of a lower unit of diamictites, sandstones and mudstones with lonestones (Bebedouro Formation) and an upper carbonate unit (Sa-litre Formation, which is correlative to the Bambu´ı Group to the South). The Una Group crops out in three discontinuous areas (Inda and Barbosa, 1978; Guimar˜aes, 1996) rela-ted to the inner parts of large-scale synclinal folds with north-south orienrela-ted axis (Misi, 1979). These three areas are named Salitre (the northernmost one), Irecˆe (central) and Una-Utinga (southernmost) (Fig.1).

gneiss. migmatite, limestone, basic volcanics and various types of granite (Montes, 1977). Thin section descriptions revealed the same sources (Kegel, 1959, S¨ofner, 1973; Misi, 1975; Inda and Barbosa, 1978, Misi, 1979), interpreted as derived from the basement of the craton (Inda and Barbosa,1978). Previous radiometric age determinations (Macedo Bo-nhomme., 1981; 1984) place the sedimentation of the Bebedouro Formation between 900 and 700 Ma, thus correlating the unit to the Sturtian Glaciation (Buchwaldt et al., 1999).

Depositional Environments

It is beyond the scope of this work to give a detailed description of the sedimentary facies and depositional environments of the Bebedouro Formation, which is done elsewhere (Guimar˜aes, 1996). A brief summary of the interpreted depositional environments is given below.

Two facies associations compose the Bebedouro Formation: a rain-out dominated gla-ciomarine association and a platformal marine association.

The first facies association is composed mainly of massive and crudely stratified di-amictites with silt to silt-sand matrix, with rare massive and planar-stratified sandstone intercalations, as well as siltstones with lonestones. The diamictites are disposed in tabular layers, which are laterally continuous for hundred of meters, composing an homogeneous succession less than 15 m thick. These diamictites are interpreted as glaciomarine deposits formed below ice shelves, in areas far from the grounding line of the feeding glaciers where rain-out processes dominated, with occasional action of turbidite currents and influence of iceberg rafting. The second facies association is characterized by fine-grained deposits with sandstone intercalations. Siltstones are often laminated, associated to sand-mud rhythmi-tes and tabular to lenticular-shaped intercalations of fine sandstones up to few centimeters thick. The whole association is seldom thicker than 10 m, only locally reaching more than 50 m. This association is interpreted as the record of deep (below storm wave action) marine environments dominated by settling of fine particles.

Clast Provenance

of the provenance of each area. The lithotypes were classified in 17 categories, including quartzite, leucogranite, biotite granite, syenogranite, mylonitic granite, gneiss, migmatite, limestone, metabasics, muscovite schist and phyllite.

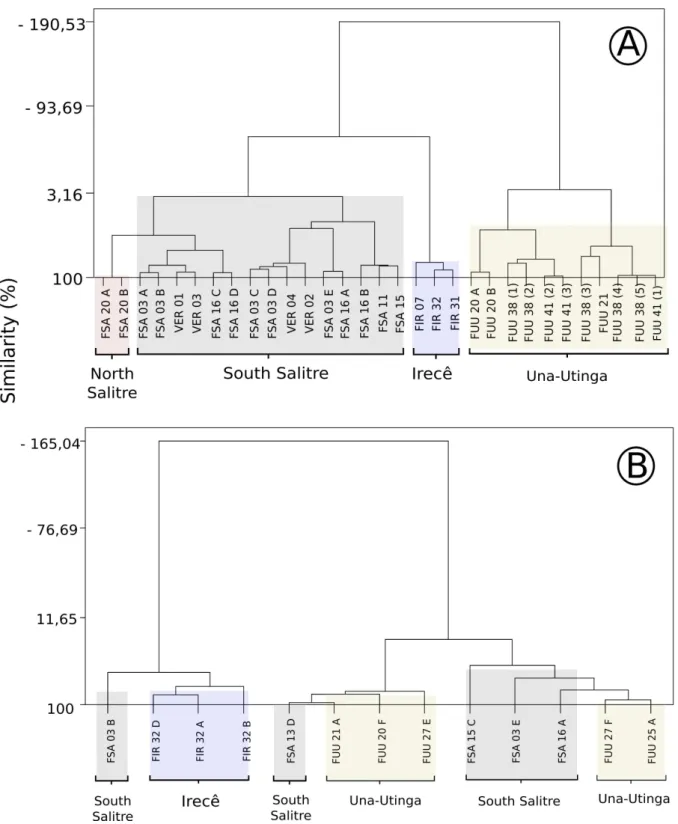

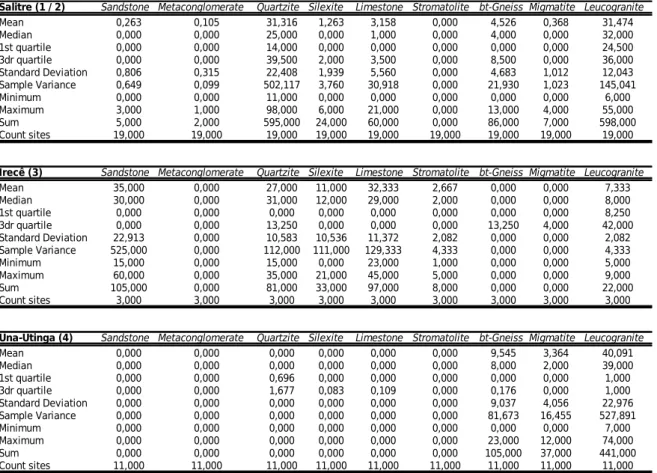

The relative variation in the frequency of quartzite, limestone, sandstone, schist and phyllite reveals that the clast composition of diamictites from the investigated areas is very inhomogeneous (Fig 2). Phyllites and schists are almost exclusive to the Salitre area, related to a local source: the Jacobina Metamorphic Complex to the east and the north (Fig 1), thus partially corroborating Inda and Barbosa (1978) previous propositions. In the Irecˆe area, the provenance revealed major contribution of oolitic carbonates and calcilutites, probably derived from local Meso-proterozoic Espinha¸co Supergroup, which is unconformably overlain by the Bebedouro Formation. At the southernmost area (Una-Utinga), the clast provenance points out mainly to granitoid sources (syeno to monzogranite and charno-enderbitic rocks), with rare anphibole-biotite schist clasts.

Cluster analysis of clast lithology data, performed after centered log-ratio transforma-tion to avoid closure effects (Aitchison, 1982), provided a clear picture of the correlatransforma-tion of the geographical distribution of samples and the diamictite provenance (Fig 3). The correlation among geographical areas and provenance clusters reveals that even areas se-parated by tens of kilometers had distinctive sources. Indeed, all samples of each of the four studied areas (Salitre North, Salitre South, Irecˆe and Una-Utinga) are grouped in separate clusters, and even a more refined separation of northern Salitre samples from the southern ones is clear.

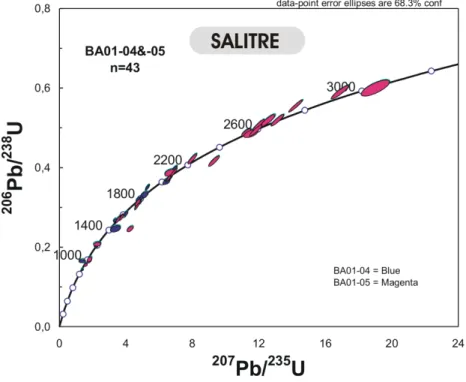

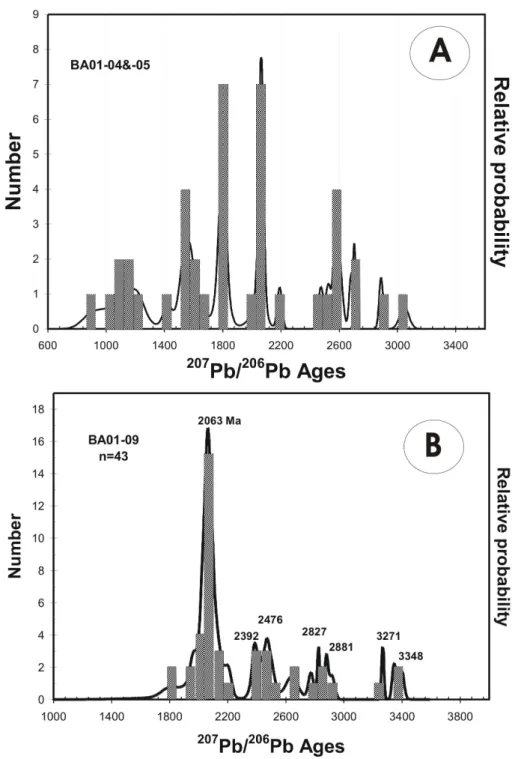

Radiometric dating of zircon crystals (SHRIMP U-Pb method, Compston et al., 1982) from five representative clasts from the Una-Utinga and Irecˆe areas reveals only Archean sources (Fig 4). The dating of two monzogranite and two granodiorite sampled from Una-Utinga and an enderbite clast from the Irecˆe area reveals sources with ages in the 3.3 to 3.5 Ga range (correlatable to the nearby basement of the craton, in the Gavi˜ao Block) and one sample of 2.6 +- 20 Ma, which can be attributed to the Jequi´e Block or to the Itabuna-Salvador-Cura¸c´a Belt (Fig 5), both at least 150 km to the East of the deposits.

Sandstone Provenance

distinctive variation from area to area, attributable to a variation of sources. The abun-dance of carbonate fragments in the samples from the Irecˆe area contrasts with the scarcity of such lithotype in the other areas. Unfortunately, the fragmentation effect masked the differences of samples with different proportions of various types of granites, migmatite and gneiss, making the samples from Una-Utinga and Salitre very similar (Fig 3).

The U-Pb SHRIMP analysis of detrital zircon of the matrix of diamictites from the Salitre area reveals a main source of 1900 to 2000 Ma (possibly reworked zircon crystals from the Espinha¸co Supergroup quartzites), several minor populations of zircon crystals dated from 3348 Ma to 2200 Ma and the occurrence of a Neoproterozoic population that constrains the maximum age of the deposit to 850 Ma. This younger population probably came from a source outside the Craton.

Discussion and Conclusions

Three areas of diamictites from the same stratigraphic level of the Neoproterozoic Be-bedouro Formation revealed clear differences of provenance, indicating nearby source areas. This areal variation of sources is observable in samples distributed in the N-S direction, suggesting a E-W direction of glacial transport in separate glaciers or one unique ice sheet forming distinct E-W clast trains or plumes. The correlation of clast lithologies with map-ped geological units of the S˜ao Francisco Craton suggests a main sediment transport from West to East, as quartzites and limestones are common rocks east of the occurrences, where the diamictites directly overly the metasedimentary Espinha¸co Supergroup, and are absent to the west, where the direct basement of the Bebedouro Formation is composed of granitoids, gneiss and migmatites.

of monozogranite and charnockite, correlative to sources at least 150 km to the East, suggests that the original area of the basin extended to the East, where icebergs could raft clasts from the opposite basin margin (current Jequi´e or Itabuna-Salvador-Curac´a Blocks) (Fig 5). The occurrence of detrital zircons of Neoproterozoic age from outside the craton corroborate the hypothesis of ice-rafting through great distances.

Our model of valley or outlet glaciers at the basin margin implies in the presence of a topographic high adjacent to the basin. Despite that, the great dimensions of the basin, the lateral continuity of sedimentary facies for hundreds of kilometers and the absence of clear tectonic controls on basin evolution do not support the model of rift-shoulder glaciers (e.g. Arnaud and Eyles, 2006; Eyles and Januszczak, 2007).

Acknowledgments

We thank FAPESP for research grant (06/61433-8), which fully supported this work. We thank Andr´e Oliveira Sawakuchi for the helpful suggestions.

References

Aitchison, J., 1982. The statistical analysis of compositional data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B (Statistical Methodology), 44 (2), 139-177. Apud Pawlowsky-Glahn, V. and Egozcue, J.J., 2006. Compositional data an their analysis: an introduction. Geological Society of London, Special Publications 264, 1-10

Allen, P., Leather, J., and Brasier, M.D., 2004. The Neoproterozoic Fiq glaciation and its aftermath, Huqf Supergroup of Oman. Basin Research 16, 507-534.

Allen, P.A. and Hoffman, P.F., 2005. Extreme winds and waves in the aftermath of a Neoproterozoic glaciation. Nature 433, 123-127.

Alkmin F.F., Neves B.B.B, Alves J.A.C. 1993. Arcabou¸co tectˆonico do Cr´aton do S˜ao Francisco. Uma Revis˜ao. In: J.M.L. Dominguez and A. Misi (eds.) O Cr´aton do S˜ao

Francisco, Salvador, SBG-N´ucleo Bahia/Sergipe, pp.: 45-62

Almeida, F.F.M., 1967. Origem e evolu¸c˜ao da plataforma brasileira. Boletim da divis˜ao de geologia e mineralogia, DNPM. v. 241, pp. 1-36.

Arnaud, E. and Eyles, C.H., 2006. Neoproterozoic environmental change recorded in the Port Askaig Formation, Scotland: climatic vs tectonic controls. Sedimentary Geology 183, 99-124.

of the Lapa Formation, S˜ao Francisco Basin, Brazil: Implications for late Neoproterozoic glacial events in South America. Precambrian Research 149, 231-248.

Babinski, M., Vieira, L.C. and Trindade, R.I.F., 2007. Direct dating of the Sete Lagoas cap carbonate (Bambu´ı Group, Brazil) and implications for the Neoproterozoic glacial events. Terra Nova 19, 401-406.

Barbosa, J.S.F., Sabat´e, P., 2004. Archean and Paleoproterozoic crust of the S˜ao Francisco Craton, Bahia, Brazil: geodynamic features. Precambrian Research 133, 1-27

Batumike, M. J., Kampunzu, A. B. and Cailteux, J. H. 2006 Petrology and geochemistry of the Neoproterozoic Nguba and Kundelungu Groups, Katangan Supergroup, southeast Congo: Implications for provenance, paleoweathering and geotectonic setting. Journal of African Earth Sciences, In Press, Available online 5 January 2006,

Brecke, D.M., and J.W. Goodge., 2007. Provenance of glacially transported material near Nimrod Glacier, East Antarctica: Evidence of the ice-covered East Antarctic shield, in Antarctica: A Keystone in a Changing World — Online Proceedings of the 10th ISAES X, edited by A.K. Cooper and C.R. Raymond et al., USGS Open-File Report 2007-1047, Extended Abstract 125, 4 p.

Bowring, S.A., Grotzinger, J.P., Condon, D.J., Ramezani, J. and Newall, M. 2007. Geochronologic constraints on the chronostratigraphic framework of the Neoproterozoic Huqf Supergroup, Sultanate of Oman. American Journal of Science, 307: 1097-1145.

Compston, W., Williams, I.S., and Clement., S.W., 1982. U-Pb ages within single zircons using a sensitive high mass-resolution ion microprobe: Abstracts, 30th American Society of Mass Spectrometry Conference, 593-5.

Condon, D., Zhu, M., Bowring, S.A., Wang, W., Yang, A., and Jin, Y., 2005. U-Pb ages from the Neoproterozoic Doushantuo Formation, China. Science 308, 95-98.

Corkoran, M., 2008. Deposition and palaeogeography of a glacigenic Neoproterozoic succession in the east Kimberley, Australia. Sedimentary Geology 204 (3-4), 61-82.

Corsetti, F.A. and Grotzinger, J.P., 2005. Origin and significance of tube structures in Neoproterozoic post-glacial cap carbonates: example from Noonday Dolomite, Death Valley, United States. Palaios 20, 348-363.

Cukrov, N., Alvarenga, C.J.S., and Uhlein, A., 2005. Litof´acies da glacia¸c˜ao neoprote-roz´oica nas por¸c˜oes sul do Cr´aton do S˜ao Francisco: exemplos de Jequita´ı (Mg) e Cristalina (GO). Revista Brasileira de Geociˆencias, 35(1):69–76.

Diekmann, B. and Kuhn, G., 1999. Provenance and dispersal of glacial–marine surface sediments in the Weddell Sea and adjoining areas, Antarctica: ice-rafting versus current

transport. Marine Geology 158: 209-231.

Dominguez, J., 1993. As coberturas do Cr´aton do S˜ao Francisco: uma abordagem do ponto de vista da an´alise de bacias. in: O Cr´aton do S˜ao Francisco,.137-159.

Dominguez, J. M. L., 1996. Geologia da Bahia: texto explicativo para o mapa geol´ogico ao milion´esimo/ Johildo Salom˜ao Figueiredo Barbosa; Jos´e Maria Landim Dominguez

-Salvador: Secretaria da Ind´ustria, Com´ercio e Minera¸c˜ao. As coberturas do Cr´aton do

S˜ao Francisco: uma abordagem do ponto de vista da an´alise de bacias, 109–112. Superin-tendˆencia de Geologia e Recursos Minerais.

Dredge, L., 2000. Carbonate dispersal trains, secondary till plumes, and ice streams in the west Foxe Sector, Laurentide Ice Sheet.. Boreas, 29:144–156.

Eyles, N. and Januszczak, N., 2004. ‘Zipper-rift’: a tectonic model for Neoproterozoic glaciations during the breakup of Rodinia after 750 Ma. Earth-Science Reviews 65, 1-73.

Eyles, C.H., Eyles, N., Grey, K., 2007. Palaeoclimate implications from deep drilling of Neoproterozoic strata in the Officer Basin and Adelaide Rift Complex of Australia: a marine record of wet-based glaciers. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 248, 291-312.

Eyles, N. and Januszczak, N. 2007. Syntectonic subaqueous mass flows of the Neopro-terozoic Otavi Group, Namibia: where is the evidence of global glaciation? Basin Research 19, 179-198.

Fanning, C.M. and Link, P.K., 2004. U-Pb SHRIMP ages of Neoproterozoic

(Sturtian) glaciogenic Pocatello Formation, southeastern Idaho. Geology 32, 881-884, doi:10.1130/G20609.1

Frimmel, H.E., Tack, L., Basei, M.S., Nutman, A.P., and Boven, A., 2006. Provenance and chemostratigraphy of the Neoproterozoic West Congolian Group in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Journal of African Earth Sciences 46, 221-239.

Gazzi, P., 1966. Le arenaire del ysch sopracretaceo dell apennino modenese; correlacione con il ysch di monghidoro. Mineralogica e Petrograca Acta, 12:69–97.

Halverson, G.P., Hoffman, P.F., Schrag, D.P., Maloof, A.C., and Rice, A.H.N., 2005. Toward a Neoproterozoic composite carbon-isotope record. Geological Society of America Bulletin 117, 1181-1207.

Bahia.

Harland, W.B. and Bidgood, D.E.T., 1959. Palaeomagnetism in some Norwegian spa-ragmites and the late pre-Cambrian ice age. Nature 184, 1860-1862.

Harland, W.B., 1964. Critical evidence for a great infra-Cambrian glaciation. Geolo-gische Rundschau 54, 45-61.

Hoffman, P.F., Kaufman, A.J., Halverson, G.P. and Schrag, D.P., 1998. A Neoprote-rozoic snowball Earth. Science 281, 1342-46.

Hoffman, P.F. and Schrag, D.P., 2002. The snowball Earth hypothesis: testing the limits of global change. Terra Nova 14, 129-155.

Hoffmann, K.-H., Condon, D.J., Bowring, S.A., and Crowley, J.L., 2004. U-Pb zir-con date from the Neoproterozoic Ghaub Formation, Namibia: zir-constraints on Marinoan glaciation. Geology 32, 817-820, doi:10.1130/G20519.l

Hyde, W.T., Crowley, T.J., Baum, S.K. and Peltier, W.R., 2000. Neoproterozoic ‘snow-ball Earth’ simulations with a coupled climate/ice-sheet model. Nature 405, 425-429.

Inda, H.A.V. and Barbosa, J.F., 1978. Texto explicativo para o mapa geol´ogico do estado da Bahia. Salvador, BA, Brasil. SME/COM, p.137.

Isotta, C.A.L., Rocha-Campos, A.C. and Yoshida, R., 1969. Striated Pavement of the Upper Pre-Cambrian Glaciation in Brazil. Nature 222, 466-468.

Kaufman, A.J., Jiang, G., Christie-Blick, N., Banerjee, D.M., and Rai, V., 2006. Stable isotope record of the terminal Neoproterozoic Krol platform in the Lesser Himalayas of northern India. Precambrian Research 147 (1-2): 156-185.

Karfunkel, J. and Hoppe, A., 1988. Late Proterozoic glaciation in central-eastern Brazil: synthesis and model. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 65, 1-21.

Kegel, W., 1959. Estudos geol´ogicos na zona central da Bahia. Div.Geol.Min.Bol, 198: 35.

Kennedy, M.J., 1996. Stratigraphy, sedimentology, and isotopic geochemistry of Aus-tralian Neoproterozoic postglacial cap dolostones: deglaciation, 13C excursions, and car-bonate precipitation. Journal of Sedimentary Research 66, 1050-1064.

Kirschvink, J.L., 1992. Late Proterozoic low-latitude glaciation: the snowball Earth. In The Proterozoic Biosphere, Schopf, J.W. and Klein, C., eds., pp. 51-52, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Martins-Neto, M.A., Gomes, N.S., Hercos, C.M., and Reis, L., 1999. F´acies

gl´acio-continentais (outwash plain) na megassequˆencia Maca´ubas, norte da serra da Agua fria

(MG). Revista Brasileira de Geociˆencias, 29(2): 281–292.

Martins-Neto, M. A., Pedrosa-Soares, A. C., and Lima, S. A. A., 2001. Tectono-sedimentary evolution of Tectono-sedimentary basins from late paleoproterozoic to late neoprote-rozoic in the S˜ao Francisco Craton and Aracuai fold belt, eastern Brazil. Sedimentary Geology, 141-142:343–370.

Montes, A.S.L., 1977. O contexto estratigr´afico e sediment´agico da Forma¸c˜ao Bebe-douro na Bahia. Disserta¸c˜ao de Mestrado. Universidade Federal de Bras´ılia, p. 100.

Misi, A., 1975. Controle estratigr´afico das mineraliza¸c˜oes de chumbo, zinco fl´uor e

b´ario no grupo Bambu´ı, parte leste da chapada de Irecˆe (Bahia). Revista Brasileira de Geociˆencias,5: 30–45.

Misi, A., 1979. O Grupo Bambu´ı no Estado da Bahia. In: Inda, H.A.V. Geologia e Recursos Minerais do Estado da Bahia; textos b´asicos. Salvador: SME.

Misi, A. and Veizer, J., 1998. Neoproterozoic carbonate sequences of the Una Group, Irecˆe Basin, Brazil: chemostratigiraphy, age and correlations. Precambrian Research 89, 87-100.

Misi, A., Kaufman, A.J., Veizer, J., Powis, K., Azmy, K., Boggiani, P.C., Gaucher, C., Teixeia, J.B.G., Sanches, A.L. and Iyer, S.S.S., 2007. Chemostratigraphy correlation of Neoproterozoic successions in South America. Chemical Geology 237, 143-167.

Oliveira, A. I. and Leonardos, O. H., 1940. Geologia do brasil. Com. Bras. Centen´arios. Portugal.

Williams, D.M., Kasting, J.F., and Frakes, L.A., 1998. Low-latitude glaciation and rapid changes in the Earth’s obliquity explained by obliquity oblateness feedback. Nature 396, 453-455.

Williams, G. and Schmidt, P., 2000. Proterozoic equatorial glaciation: Has ‘snowball Earth’ a snowball’s chance? The Australian Geologist 117, 21-25.

Williams, G.E., 2008. Proterozoic (pre-Ediacaran) glaciation and the high-obliquity, low-latitude ice, strong seasonality (HOLIST) hypothesis: principles and tests. Earth-Science Reviews 87, 61-93.

Williams, G.E., Gostin, V.A., McKirdy, D.M. and Preiss, W.V., 2008. The Elatina glaciation, late Cryogenian (Marinoan Epoch), South Australia: Sedimentary facies and palaeoenvironments. Precambrian Research 163(3-4):307-331.

of ice-rafted clasts in Arctic Ocean sediments: implications for the conguration of late

Quaternary oceanic and atmospheric circulation in the Arctic. Marine Geology, 172:

91-115.

Prave, A.R., 1999. Two diamictites, two cap carbonates, two ?13C excursions, two rifts: The Neoproterozoic Kingston Peak Formation, Death Valley, California. Geology 27 (4), 339-342

Rocha Campos, A.C. and Hasu´ı, Y., 1981. Tillites of the Maca´ubas Group (Proterozoic)

in central Minas Gerais and Southern Bahia, Brazil. in: Hambrey, M. J. and Harland, W. B (eds). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Earths Pre-Pleistocene Glacial Record, 924-927.

Sohl, L.E., Christie-Blick, N. and Kent, D.V., 1999. Paleomagnetic polarity reversals in Marinoan (ca 600 Ma) glacial deposits of Australia: implications for the duration of low-latitude glaciation in Neoproterozoic time. Geological Society of America Bulletin 111, 1120-1139.

Shields, G.A., Deynoux, M., Culver, S.J., Brasier, M.D., Affaton, P., and Vandamme, D., 2007. Neoproterozoic glaciomarine and dap dolostone facies of the southwestern Ta-oud´eni Basin (Walidiala Valley, Senegal/Guinea, NW Africa). Comptes Rendus Geoscien-ces 339 (3-4): 186-199.

S¨ofner, B., 1973. Observa¸c˜oes sobre a estratigrafia do pr´e-cambriano da chapada dia-mantina, sudeste e da cont´ıgua. Miss˜ao Geol´ogica Alem˜a/SUDENE, Divis˜ao de Hidroge-ologia, 23–32.

Talarico, F. and Sandroni, S. and the Andrill-Miss Science team., 2007. Clast prove-nance and variability in MIS (AND-1B) core and their implications for the paleoclimatic evolution recorded in the Windless Bight - southern McMurdo Sound area (Antarctica). U.S. Geological Survey and The National Academies; USGS, Extended Abstract 118, p. 1047.

Uhlein, A., Trompette, R. R., and Egydio-Silva, M., 1998. Proterozoic rifting and closure, SE border of the sao francisco craton, brazil. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 11(2):191–203.

Figura 1. The figure on the left shows a sketch of the S˜ao Francisco Craton, with the striated surface location of the Jequita´ı Formation that crops out at the city of Jequita´ı

(central region), and its equivalent units: Maca´ubas Group at Ara¸cua´ı fold belt on the

Figura 2. Variation of median, first and third quartiles, as well as outliers values for each discriminant lithology along the four areas (1- North Salitre, 2 - South Salitre, 3 - Irecˆe, 4 - Una-Utinga

Salitre (1 / 2) Sandstone Metaconglomerate Quartzite Silexite Limestone Stromatolite bt-Gneiss Migmatite Leucogranite

Mean 0,263 0,105 31,316 1,263 3,158 0,000 4,526 0,368 31,474

Median 0,000 0,000 25,000 0,000 1,000 0,000 4,000 0,000 32,000

1st quartile 0,000 0,000 14,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 24,500

3dr quartile 0,000 0,000 39,500 2,000 3,500 0,000 8,500 0,000 36,000

Standard Deviation 0,806 0,315 22,408 1,939 5,560 0,000 4,683 1,012 12,043

Sample Variance 0,649 0,099 502,117 3,760 30,918 0,000 21,930 1,023 145,041

Minimum 0,000 0,000 11,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 6,000

Maximum 3,000 1,000 98,000 6,000 21,000 0,000 13,000 4,000 55,000

Sum 5,000 2,000 595,000 24,000 60,000 0,000 86,000 7,000 598,000

Count sites 19,000 19,000 19,000 19,000 19,000 19,000 19,000 19,000 19,000

Irecê (3) Sandstone Metaconglomerate Quartzite Silexite Limestone Stromatolite bt-Gneiss Migmatite Leucogranite

Mean 35,000 0,000 27,000 11,000 32,333 2,667 0,000 0,000 7,333

Median 30,000 0,000 31,000 12,000 29,000 2,000 0,000 0,000 8,000

1st quartile 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 8,250

3dr quartile 0,000 0,000 13,250 0,000 0,000 0,000 13,250 4,000 42,000

Standard Deviation 22,913 0,000 10,583 10,536 11,372 2,082 0,000 0,000 2,082

Sample Variance 525,000 0,000 112,000 111,000 129,333 4,333 0,000 0,000 4,333

Minimum 15,000 0,000 15,000 0,000 23,000 1,000 0,000 0,000 5,000

Maximum 60,000 0,000 35,000 21,000 45,000 5,000 0,000 0,000 9,000

Sum 105,000 0,000 81,000 33,000 97,000 8,000 0,000 0,000 22,000

Count sites 3,000 3,000 3,000 3,000 3,000 3,000 3,000 3,000 3,000

Una-Utinga (4) Sandstone Metaconglomerate Quartzite Silexite Limestone Stromatolite bt-Gneiss Migmatite Leucogranite

Mean 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 9,545 3,364 40,091

Median 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 8,000 2,000 39,000

1st quartile 0,000 0,000 0,696 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 1,000

3dr quartile 0,000 0,000 1,677 0,083 0,109 0,000 0,176 0,000 1,000

Standard Deviation 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 9,037 4,056 22,976

Sample Variance 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 81,673 16,455 527,891

Minimum 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 7,000

Maximum 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 23,000 12,000 74,000

Sum 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 105,000 37,000 441,000

Count sites 11,000 11,000 11,000 11,000 11,000 11,000 11,000 11,000 11,000

Salitre (1 / 2) Milonitic bt-Granite Phaneritic bt-Granite Porfiritic bt-Granite Pegmatite Alcali-Granite Matabasics Schists Quartz vein

Mean 0,263 12,947 0,105 0,368 5,105 0,211 2,737 3,737

Median 0,000 10,000 0,000 0,000 3,000 0,000 1,000 1,000

1st quartile 0,000 2,000 0,000 0,000 0,500 0,000 0,000 0,000

3dr quartile 0,000 21,000 0,000 0,500 10,000 0,000 2,000 4,500

Standard Deviation 0,806 12,756 0,315 0,684 4,954 0,713 5,476 5,496

Sample Variance 0,649 162,719 0,099 0,468 24,544 0,509 29,982 30,205

Minimum 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000

Maximum 3,000 45,000 1,000 2,000 14,000 3,000 20,000 19,000

Sum 5,000 246,000 2,000 7,000 97,000 4,000 52,000 71,000

Count sites 19,000 19,000 19,000 19,000 19,000 19,000 19,000 19,000

Irecê (3) Milonitic bt-Granite Phaneritic bt-Granite Porfiritic bt-Granite Pegmatite Alcali-Granite Matabasics Schists Quartz vein

Mean 1,333 5,333 0,000 0,000 0,667 0,000 0,000 5,000

Median 2,000 5,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 5,000

1st quartile 0,000 5,500 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 1,000

3dr quartile 0,000 40,250 0,000 0,750 10,000 0,000 0,000 5,000

Standard Deviation 1,155 1,528 0,000 0,000 1,155 0,000 0,000 2,000

Sample Variance 1,333 2,333 0,000 0,000 1,333 0,000 0,000 4,000

Minimum 0,000 4,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 3,000

Maximum 2,000 7,000 0,000 0,000 2,000 0,000 0,000 7,000

Sum 4,000 16,000 0,000 0,000 2,000 0,000 0,000 15,000

Count sites 3,000 3,000 3,000 3,000 3,000 3,000 3,000 3,000

Una-Utinga (4) Milonitic bt-Granite Phaneritic bt-Granite Porfiritic bt-Granite Pegmatite Alcali-Granite Matabasics Schists Quartz vein

Mean 5,545 27,091 0,091 0,727 12,818 0,091 0,545 2,636

Median 0,000 37,000 0,000 0,000 8,000 0,000 0,000 2,000

1st quartile 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,022 0,000 0,000 0,000

3dr quartile 0,000 0,419 0,000 0,028 0,250 0,000 0,074 0,036

Standard Deviation 12,910 20,892 0,302 1,272 22,013 0,302 1,508 2,580

Sample Variance 166,673 436,491 0,091 1,618 484,564 0,091 2,273 6,655

Minimum 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000 0,000

Maximum 39,000 59,000 1,000 4,000 77,000 1,000 5,000 7,000

Sum 61,000 298,000 1,000 8,000 141,000 1,000 6,000 29,000

Count sites 11,000 11,000 11,000 11,000 11,000 11,000 11,000 11,000

o subme tido `a re v is ta T er ra No va

Spot U (ppm)

7 311 225 0,75 142 0,44 1.889 1.7 0.2929 0.4 2729 ±38 2396 ± 44 2738 ±42 3414.7 ± 7 2607 ±52 25

5 308 154 0,52 160 0,43 1.658 1.8 0.30214 0.32 3031 ±44 2739 ± 57 3058 ±46 3463.4 ± 5.7 2493 ±57 14

6 64 30 0,48 34 0,35 1.612 2 0.2796 0.65 3103 ±49 2928 ± 72 3115 ±52 3344 ±12 2857 ±94 8

4 170 154 0,94 102 0,08 1.435 1.8 0.2944 0.54 3407 ±48 3367 ±100 3419 ±52 3437.6 ± 8.6 3255 ±63 1

3 110 75 0,71 66 0,26 1.429 1.9 0.2955 0.5 3412 ±50 3382 ±110 3428 ±54 3434.9 ± 8.4 3162 ±73 1

1 99 47 0,49 60.2 0,13 1.417 1.9 0.2976 0.5 3439 ±51 3421 ±120 3445 ±53 3452.2 ± 8 3303 ±77 0

2 199 142 0,74 123 0,07 1.393 1.8 0.2994 0.36 3487 ±48 3526 ±140 3496 ±52 3463.7 ± 5.7 3336 ±66 -1

6 166 229 1,43 82.2 0,32 1.73 1.8 0.2684 0.42 2933 ±42 2731 ± 56 2929 ±50 3280.9 ± 7.4 2961 ± 64 12

1 198 140 0,73 101 0,45 1.677 1.8 0.26976 0.36 3004 ±42 2827 ± 58 3016 ±45 3282.4 ± 6.7 2829 ± 58 9

5 272 176 0,67 141 0,24 1.658 1.7 0.26095 0.35 3037 ±42 2904 ± 61 3045 ±45 3239.9 ± 6.1 2917 ± 57 7

2 160 105 0,68 84.6 0,36 1.623 1.8 0.2682 0.4 3086 ±44 2950 ± 65 3080 ±47 3277.6 ± 7.1 3163 ± 65 6

4 182 114 0,65 96.8 0,25 1.619 1.8 0.2666 0.39 3095 ±43 2967 ± 66 3102 ±46 3273.4 ± 6.6 2974 ± 59 6

7 56 29 0,53 32.6 0,47 1.474 2.1 0.2703 1.1 3326 ±55 3373 ±120 3340 ±58 3284 ±18 3017 ±110 -1

3 48 33 0,70 28.5 0,45 1.448 2.1 0.2661 0.68 3373 ±54 3526 ±160 3391 ±58 3259 ±13 3083 ± 91 -3

1 443 165 0,38 98.1 2,09 3.881 1.7 0.14797 0.44 1450 ±22 1385 ±23 1445 ±24 2109 ±24 1549 ±57 45

5 138 70 0,53 50.3 0,51 2.349 1.8 0.1763 0.6 2276 ±35 2203 ±41 2263 ±38 2576 ±14 2500 ±65 13

4 171 138 0,83 71.4 0,14 2.06 1.8 0.17293 0.52 2548 ±38 2540 ±49 2556 ±42 2574 ±10 2461 ±50 1

2 208 106 0,53 89.1 0,19 2.005 1.8 0.17821 0.43 2604 ±38 2598 ±50 2614 ±40 2620.3 ± 8.2 2432 ±50 1

6 81 47 0,59 35.2 0,26 1.978 2.9 0.1824 10 2632 ±63 2624 ±85 2638 ±67 2654 ±17 2535 ±94 1

3 100 78 0,81 43.5 0,32 1.974 1.9 0.181 0.64 2635 ±41 2635 ±55 2642 ±44 2636 ±14 2560 ±61 0

7 334 282 0,87 164 0,21 1.743 1.7 0.26033 0.29 2919 ±40 2739 ±54 2937 ±44 3237.8 ±5 2711 ±49 11

4 113 62 0,57 62.2 0,17 1.557 1.8 0.2644 0.48 3193 ±46 3134 ±80 3196 ±49 3264.6 ±7.9 3135 ±66 2

1 187 139 0,77 104 0,25 1.547 1.8 0.26893 0.36 3208 ±45 3141 ±77 3217 ±48 3287 ±6.2 3093 ±60 2

5 171 113 0,68 95 0,13 1.549 1.8 0.26155 0.38 3207 ±45 3171 ±80 3222 ±48 3249.5 ±6.4 2977 ±59 1

2 134 82 0,63 76.8 0,11 1.503 1.8 0.2701 0.41 3286 ±47 3270 ±92 3297 ±49 3301.1 ±6.6 3088 ±62 0

3 107 57 0,55 61.3 0,12 1.502 1.8 0.2692 0.45 3286 ±47 3277 ±94 3297 ±50 3295.3 ±7.2 3061 ±64 0

6 119 72 0,63 68.2 0,15 1.497 1.8 0.2715 0.43 3294 ±47 3281 ±94 3304 ±50 3307.2 ±7.2 3125 ±66 0

3 core 310 330 1,10 117 0,57 2.27 1.7 0.24985 0.32 2342 ±33 2086 ±36 2477 ±38 3155.1 ±6.4 1274 ±26 35

3 rim 189 135 0,74 98.7 0,12 1.648 1.7 0.26705 0.35 3054 ±42 2900 ±61 3085 ±45 3282.6 ±5.9 2630 ±50 7

4 163 221 1,40 87.4 0,15 1.607 1.8 0.2625 0.4 3115 ±44 3013 ±69 3304 ±51 3254.1 ±6.6 1728 ±36 4

5 158 122 0,80 86.3 0,08 1.575 1.8 0.2639 0.39 3167 ±45 3087 ±74 3169 ±48 3266.4 ±6.3 3138 ±62 3

6 93 91 1,01 51.5 0,13 1.556 1.9 0.2719 0.49 3196 ±47 3099 ±79 3323 ±51 3310.6 ±8.2 1819 ±41 4

2 116 76 0,68 65.5 0,43 1.525 1.8 0.2713 0.45 3239 ±46 3191 ±83 3244 ±49 3291.9 ±8.4 3164 ±71 2

1 142 76 0,56 80.7 0,13 1.514 1.8 0.2686 0.38 3265 ±45 3240 ±86 3271 ±48 3290.9 ±6.3 3148 ±64 1

Sample / Area

Th (ppm)

232 Th

/238 U 206Pb

(ppm)

Common

206Pb (%)

Total

238 U

/206 Pb

Error (± 1σ) %

Total

207Pb

/206Pb

Error (± 1σ) %

(1)

206Pb

/238U

Age

(2)

206Pb

/238U

Age

(3)

206Pb

/238U

Age

(1)

207Pb

/206Pb

Age

(1)

208Pb

/232Th

Age

Discordance (%)

FUU 20 E / Una-Utinga

FUU 20 B / Una-Utinga

FUU 20 A / Una-Utinga

FUU 21 F / Una-Utinga

FIR 32 F / Irecê

Samples Q F P O L M/C A Total

Salitre

FSA03B 260 216 160 56 7 30 7 0 30 25 1 3 1 86 21 0 65 0 130 117 7 500

FSA13D 188 165 87 78 5 18 0 0 57 32 13 12 36 36 0 0 0 59 214 5 500

FSA16A 333 265 64 201 2 50 16 0 74 39 18 13 4 55 55 0 0 0 123 35 3 500

FSA15C 169 157 85 72 0 12 0 0 45 17 20 5 3 29 29 0 0 0 41 255 2 500

FSA02B 284 256 156 100 6 17 5 0 38 16 13 7 2 7 7 0 0 0 35 163 8 500

FSA09C 337 294 168 126 8 27 8 0 112 18 70 20 4 28 24 0 3 1 71 19 4 500

FSA10A 191 178 107 71 1 9 3 0 29 6 13 4 6 19 15 0 4 0 32 258 3 500

FSA14B 203 193 114 79 4 1 5 0 44 15 14 11 4 21 17 0 4 0 31 230 2 500

FSA13B 218 210 155 55 3 3 2 0 36 11 11 9 5 28 24 0 4 0 36 213 5 500

FSA11B 296 280 165 115 2 10 4 0 97 34 40 14 9 41 12 0 28 1 57 64 2 500

FSA11D 296 283 124 159 1 7 5 0 66 19 27 12 8 12 10 0 0 2 25 120 6 500

FSA14C 256 234 107 127 1 5 16 0 56 25 18 6 7 16 14 0 0 2 38 168 4 500

FSA13C 330 301 109 192 18 6 5 0 85 33 27 11 14 32 29 0 2 1 61 51 2 500

FSA13A 453 406 68 338 1 38 8 0 26 9 6 8 3 2 0 0 2 0 49 19 0 500

FSA03E 401 373 231 142 2 15 11 0 22 8 5 7 2 14 10 0 0 4 42 62 1 500

FSA10C 351 339 90 249 0 6 6 0 117 21 56 25 15 1 0 0 1 0 13 24 7 500

FSA03D 460 452 134 318 0 7 1 0 35 14 13 7 1 0 0 0 0 0 8 2 3 500

FSA03C 362 354 65 289 0 1 7 0 35 15 10 9 1 18 0 0 18 0 26 83 2 500

Irecê

FIR32A 197 182 78 104 0 10 5 0 9 4 1 3 1 39 4 0 34 1 54 249 6 500

FIR07A 238 212 45 167 0 21 5 0 72 19 30 23 0 26 12 0 14 0 52 160 4 500

FIR32B 203 183 71 112 0 18 2 0 31 23 2 6 0 57 1 0 55 1 77 209 0 500

FIR32D 265 230 91 139 0 21 14 0 27 8 11 6 2 67 0 0 67 0 102 138 3 500

Una-Utinga

FUU30A 358 335 88 247 0 15 8 0 52 11 19 15 7 1 1 0 0 0 24 86 3 500

FUU19A 409 371 101 270 0 31 7 0 49 19 11 19 0 2 2 0 0 0 40 40 0 500

FUU25B 270 266 104 162 0 4 0 0 138 49 60 13 16 1 1 0 0 0 5 88 3 500

FUU27D 363 346 104 242 0 16 1 0 117 34 58 25 0 2 0 0 2 0 19 8 10 500

FUU30B 392 328 84 244 0 57 7 0 60 9 14 32 5 11 1 0 10 0 75 34 3 500

FUU25A 161 143 35 108 0 13 5 0 46 15 16 11 4 33 30 0 2 1 51 257 3 500

FUU30C 244 233 49 184 0 11 0 0 140 36 39 30 35 5 0 0 3 2 16 85 26 500

FUU24B 265 252 77 175 0 9 4 0 129 61 38 13 17 2 1 0 1 0 15 81 23 500

FUU21A 162 142 99 43 5 15 0 0 83 36 35 11 1 75 72 0 0 3 95 172 8 500

FUU27E 174 161 114 47 6 5 2 0 87 47 11 12 17 69 64 0 1 4 87 168 2 500

FUU27F 142 132 76 56 1 6 3 0 70 40 20 2 8 38 38 0 0 0 48 246 4 500

FUU21B 231 228 81 147 0 2 1 0 128 70 26 11 21 30 30 0 0 0 33 111 0 500

FUU27A 403 388 146 242 0 14 1 0 92 27 44 20 1 0 0 0 0 0 15 4 1 500

FUU27C 347 342 87 255 0 4 1 0 123 71 24 15 13 9 9 0 0 0 14 21 0 500

FUU19C 352 336 113 223 0 7 9 0 131 49 44 36 2 0 0 0 0 0 16 15 2 500

FUU20F 115 105 28 77 0 10 0 0 73 30 19 12 12 40 35 0 0 5 50 271 1 500

FUU24A 275 268 47 221 0 5 2 0 192 102 46 35 9 0 0 0 0 0 7 25 8 500

1

Q 3

L 4 2 M/C F 5 P A O Micropertite

Area Qm Qmh Qmu Qph Qpu Qpm Qmv Mc Mp Lp Lv Ls Lm Lt

Stable quartzose grains

Qm Monocrystalline quartz grains Unstable polycristalline lithic fragments

Qmh Monocrystalline quartz grains with homogeneous extinction Lp Plutonic lithic fragments

Qmu Monocrystalline quartz grains with undulatory extinction Lv Volcanic and metavolcanic lithic fragments

Qph Polycristalline lithic fragments with homogeneous extinction Ls Sedimentary lithic fragments

Qpu Polycristalline lithic fragments with undulatory extinction Lm Metamorphic lithic fragments

Qpm Micropolycristalline lithic fragments Lt Total lithic fragments=L+Lp+Lv+Ls+Lm

Qv Volcanic quartz

Matrix/Cement Monocrystalline feldspar grains

Plagioclase Acessories

Orthoclase

Mc Microcline

Mp

Tabela 4. The values corresponds to each identified component in a 500 counting points per thin section

Samples Total

Salitre

FSA13D 0 0 31 0 0 5 18 0 54 FSA13C 2 0 31 1 0 18 6 5 63 FSA13B 4 0 26 0 0 3 3 2 38 FSA13A 0 2 0 0 0 1 38 8 49 FSA09C 0 3 8 2 2 8 27 8 58 FSA10C 1 0 0 0 0 0 6 6 13 FSA10A 0 4 9 5 0 2 9 3 32 FSA11D 0 0 9 0 0 1 7 5 22 FSA11B 28 0 11 0 2 2 10 4 57 FSA14C 0 0 14 0 0 1 5 16 36 FSA14B 3 0 16 0 0 4 1 5 29 FSA15C 0 0 13 0 0 0 12 0 25 FSA02B 0 0 7 0 0 6 17 5 35 FSA16A 0 0 59 0 0 2 50 16 127

FSA03D 0 0 0 0 0 0 7 1 8

FSA03E 0 0 7 0 0 2 16 11 36 FSA03C 17 0 0 0 0 0 1 7 25 FSA03B 34 0 4 0 0 7 30 7 82

Irecê

FIR07A 14 5 11 0 0 0 21 5 56 FIR31D 22 0 0 0 0 0 21 14 57 FIR31C 1 0 3 0 0 0 27 5 36 FIR32B 49 5 2 0 0 0 18 2 76 FIR32A 34 0 3 0 0 0 10 5 52

Una-Utinga

FUU27F 0 0 17 2 0 1 6 3 29 FUU27E 1 0 32 0 0 6 5 2 46 FUU27C 0 0 6 0 0 0 4 1 11 FUU27D 0 3 0 0 0 0 16 1 20 FUU27A 0 2 0 0 0 0 14 1 17 FUU21B 0 0 22 0 0 2 2 1 27 FUU21A 0 0 24 0 0 5 15 0 44

FUU24A 0 0 0 0 0 0 5 2 7

FUU24B 1 12 0 0 0 0 9 4 26

FUU25B 0 0 0 0 0 0 4 0 4

FUU25A 0 5 17 0 0 0 13 5 40 FUU19C 0 0 0 0 0 0 7 9 16 FUU19A 0 0 2 0 0 0 31 7 40 FUU20F 0 0 34 2 0 0 10 0 46 FUU30A 0 0 1 0 0 0 15 8 24 FUU30B 0 7 0 0 0 0 57 7 71 FUU30C 3 0 0 0 0 0 11 0 14

Area Quartz / Carbonate Siltstone Granitoid Schists Metabasics Qph Qpu Qpm

Tabela 5. The components corresponds to the lithic fragments recognized in 40 thin sec-tions, divided by area. For cluster analysis the matrix as well as the acessory minerals values were not considered