Department of Social and Organizational Psychology

Corporate Social Responsibility: from the company to the

individual.

A study on ethics inside Portuguese companies

Cláudia Granada Almeida

Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Master in Social and Organizational Psychology

Advisor:

Eduardo Simões, PhD., Assistant Professor,

ISCTE-IUL

ii

Acknowledgements

“The fireworks begin today. Each diploma is a lighted match. Each one of you is a fuse.” (Koch, 1983, oral communication)

The quote above, from New York Mayor Edward Koch on a commencement speech in 1983, represents how I feel today, at the end of a journey of which this document is the written and permanent proof. From the development of the initial idea and problem I wanted to tackle, through the research phase reading and visiting companies until the analysis and compilation of results and conclusions, this thesis project has been full of discoveries, reflections about the work and about myself and more certainties about my professional future. One first aspect that I should highlight is that this has become a journey of persistance and passion through the world of Business Ethics and Corporate Social Responsibility, with the permanent focus on their possible impact in society and more specifically within organizations.

I would like to thank firstly a few people that at times pushed me and at others supported me at all the right moments. To my mother, for always giving me a different angle to look at things and ponder, besides the continuing care and reassuring patience; to my grandparents, my father and Isabel who kept asking for regular updates and reminding me of the bigger picture, pushing me forward at every step of the way. To professor Eduardo, for all the recommendations and promptness in our constant communication, for giving me perspective and not letting me do less than I could. Thank you also for instilling in me more rigor and formality. To professor Helena for answering the doubts of this student and giving me the background to test and play more with statistics, to Sandra, my colleague and friend at all the defining moments, for listening, recommending and being a great example, to Mike, because even at the distance and out of context you made this thesis better and contributed to the soundtrack of its progress.

Throughout the development of this research, I worked in different organizations, within different teams, which contributed directly and indirectly to increase my sense of purpose, hosting discussions and debating the role of ethics in the workplace. Thanks, Ana, Zé, Gonçalo, my teams in AIESEC ISCTE and my colleagues in Jordan for adding up to my research an intuitive and first-hand experience. You also made me manage better my priorities and enjoy the different work rhythms and tasks. Finally, thank you to my closest friends, who lightened up my mood, checked up on me and filled all the other moments with fun and good memories, giving me energy and sense of accomplishment until now, especially to Helena, Sofia, Inês, Rita, Raquel, Pedro, António, Tareq, Huda, Suzanne, and many others that have made me such a persistent and inspired person.

Finally, this work has also brought more meaning to my professional future as a HR employee or consultant and a guarantee that I’ll use my knowledge to improve the workplaces I will be part of.

iii

Table of Contents

Index of Figures and Tables……….………..……4

Abstract………..6

Resumo……….7

1.Introduction………8

1.1.Corporate Social Responsibility.………10

1.2.Business Ethics……….…13

2.Objectives and Hypotheses……….….…16

3.Method……….17

3.1.Procedure……….….17

3.2.Variables and Measures……….….…17

3.3.Sample………...21

4.Results……….21

4.1.Preliminary Analyses to the Main Variables……….………21

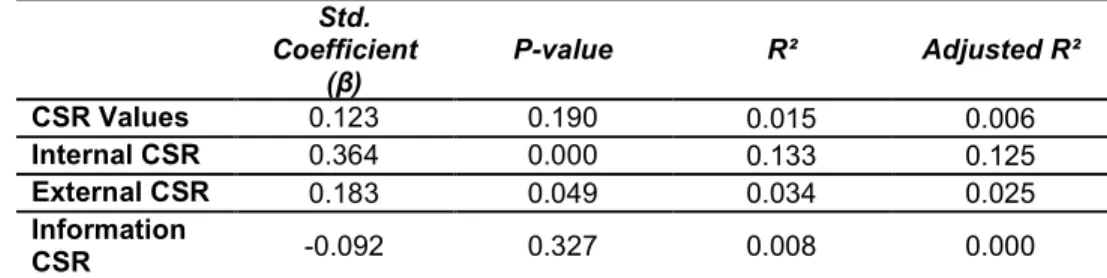

4.2.Hypothesis 1: Perceived CSR and Ethical Acceptability of Organizational Conduct...28

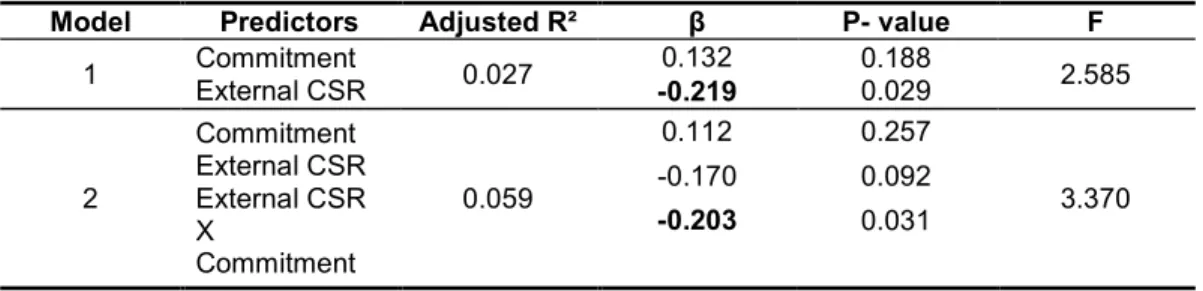

4.3.Hypothesis 2: Organizational Commitment, Perceived CSR and Ethical Acceptability…...….30

4.4.Hypothesis 3: Demographic Variables……….……….34

5.Discussion………...37

5.1.Multidimensionality of the main constructs...37

5.2.Hypothesis 1: CSR and Individual Ethics…….……….…………...38

5.3.Hypothesis 2: Organizational Commitment as a Moderator…….……….39

5.4.Hypothesis 3: Effects of Demographic Variables………....40

5.5.Theoretical Implications………...41

5.6.Practical Implications………42

5.7.Limitations and Recommendations………43

6.Conclusions……….44

References………..46

iv

Index of Figures and Tables

Figure 3.1 – Synthesis of the variables studied and their predicted relations (hypotheses) with each

other……….20

Figure 4.2 – Representation of hypothesis one………...………28 Figure 4.3 – Representation of hypothesis two………31 Figure 4.4 – Representation of the moderation effect of commitment on the relationship between

perceived CSR values and ethical judgment on Relations with the Exterior………32

Figure 4.5 - Representation of the moderation effect of commitment on the relationship between

perceived External CSR practices and ethical judgment on Relations with the Exterior (left) and Employees’ Rights (right)…..………..……….34

Figure 4.6 - Representation of hypothesis three………..34 Figure 4.7 - Differences in gender on the ethical acceptability of the Relations with the Exterior ….…….36 Figure 4.8 - Differences in religious groups on the ethical acceptability of the Relations with the

Exterior………37

Figure 5.9 – Representation of the results confirming our main hypothesis (all correlations with p<0.05,

except for the ones marked with an *, in those cases results are marginally significant)……….…….38

Figure 5.10 – Representation of the significant moderation effects of Organizational Commitment (data

refers to the interaction variable IV and MV, p<0.05)………..40

Figure 5.11 – Main effects of the demographics on the Ethical Acceptability of dubious corporate conduct

(all correlations made available are p<0.01)……….…40

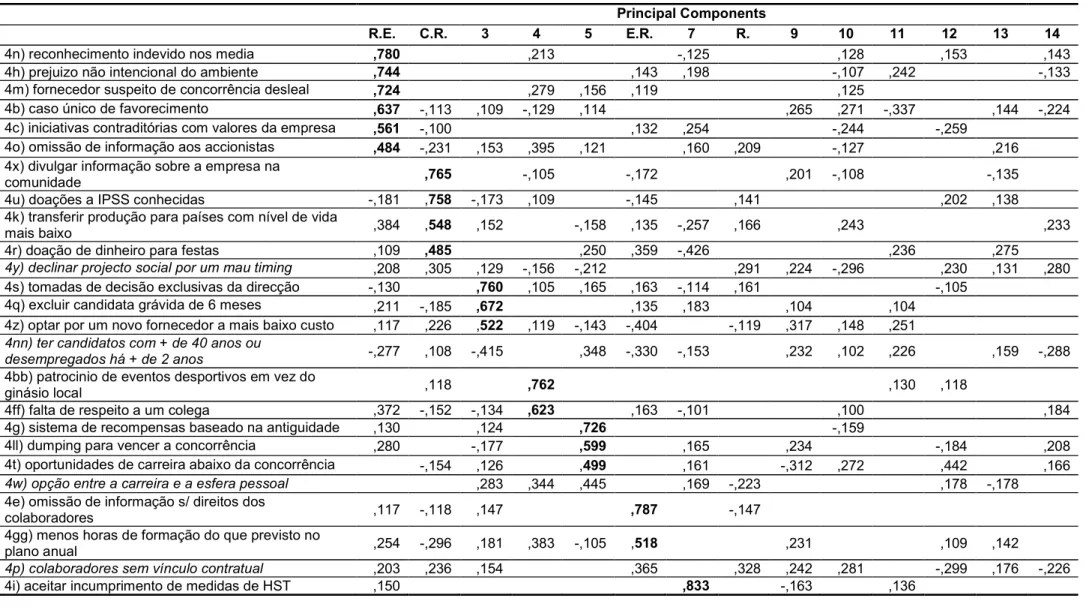

Table 4.1 - Factor structure, after orthogonal rotation, of the fifteen items of question n° 1 (CSR

values)……….22

Table 4.2 - Factor structure, after orthogonal rotation, of the twenty-six items of question n° 2 (CSR

practices)……….23

Table 4.3 – Final items included in each of the perceived CSR practices……….………..24 Table 4.4 - Factor structure, after orthogonal rotation, of the forty original items of question n° 4

(ethically-dubious corporate conduct)………..25

Table 4.5 – Final fourteen items included in each of the indicators of ethically-dubious organizational

conduct………27

Table 4.6 - Descriptive statistics of the main variables……….………..27 Table 4.7 – Effects of perceived CSR indicators (as IV) on the Relations with the Exterior (as DV)…..…29 Table 4.8 - Effects of perceived CSR indicators (IV) on the Community Repercussions (as DV)………...29 Table 4.9 - Effects of perceived CSR indicators on Employees’ Rights (DV)……….……30 Table 4.10 - Effects of perceived CSR indicators on Recycling (DV)……….…..30

v

Table 4.11 - Effects of perceived CSR indicators and Company Seniority on Organizational Commitment

(DV)………..30

Table 4.12 - Effects of Organizational Commitment on the four indicators of Ethical Acceptability of organizational conduct (DV)……….31

Table 4.13 – Moderation hypothesis of organizational commitment on the relation between perceived CSR values and ethical acceptability of Relations with the Exterior …………..………..32

Table 4.14 – Moderation hypothesis of organizational commitment on the relation between perceived External CSR practices and ethical acceptability of Relations with the Exterior………..……….…..33

Table 4.15 – Moderation hypothesis of organizational commitment on the relation between perceived External CSR practices and ethical acceptability of Employees’ Rights .………..………..33

Table 4.16 - Effects of Company Seniority on the Ethical Acceptability indicators (DV)...………34

Table 4.17 - Effects of Age on the Ethical Acceptability indicators (VD)………..………35

Table 4.18 – Specific effects of gender on ethical acceptability indicators (VD)………..………..35

Table 4.19 – Effects of religious orientation on ethical acceptability indicators (VD)……….………36

Table 4.20 – Differences among the three groups of religious orientation on the acceptability of the Relations with the Exterior (p<0.05)………37

vi

Abstract

The present research attempts to explore the multi-dimensional nature of corporate social responsibility (CSR), further understand how a perceived CSR context is associated with the individual ethical judgement of organizational members and, lastly, validate the effect of some other variables on individual ethics.

A newly-created questionnaire was filled by employees from several Portuguese companies (N=116), who had to assess their organizations’ CSR values and practices and rate a list of ethically-dubious corporate conduct examples. We assessed on the complexity of the constructs of CSR and ethically-dubious corporate conduct and we were able to better comprehend the association of the main variables with each other and some participant attributes, such as their organizational commitment and socio-demographical variables.

The results of this exploratory study give some support the main hypothesis that the higher the perceived social responsibility, the less prone employees are to accept ethically-reprehensible practices and that this evidence is especially strong among the most committed workers. The influence of the other variables studied (e.g., gender, age, company seniority and religious orientation) also converge with the existing but sparse literature on the subject. These results suggest that the way in which organizational values and practices revolving around CSR are perceived may be considered a contextual determinant of the ethics of the employees, having a positive impact at the individual level of the organization.

Keywords: Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), individual ethics, stakeholders, ethical acceptability.

3400 Professional Psychological & Health Personnel Issues 3450 Professional Ethics & Standards & Liability

3600 Industrial & Organizational Psychology 3650 Personnel Attitudes & Job Satisfaction

vii

Resumo

O presente estudo pretende analisar a natureza multidimensional da responsabilidade social das organizações (RSO), melhor compreender de que forma um contexto de RSO percebida está associado ao julgamento ético individual de membros de organizações e, por fim, validar o efeito de outras variáveis na ética individual.

Um novo questionário foi passado e preenchido por colaboradores de várias empresas portuguesas (N=116), que tinham de avaliar os seus valores e práticas de RSO e classificar uma lista de exemplos de conduta organizacional eticamente duvidosa. Verificámos a complexidade dos constructos de RSO e conduta organizacional eticamente dúbia e analisámos melhor a associação entre as principais variáveis entre si e com alguns atributos dos participantes, tal como a sua implicação organizacional e variáveis socio-demográficas.

Os resultados deste estudo exploratório suportam parcialmente a hipótese principal de que quanto mais elevada é a responsabilidade social percebida, menor a probabilidade dos colaboradores aceitarem práticas eticamente reprováveis, sendo esta ocorrência mais forte entre os colaboradores com maior implicação organizacional. A influência das outras variáveis estudadas (e.g., género, idade, antiguidade na empresa e orientação religiosa) também confirma o demonstrado pela esparsa literatura sobre o tema. Estes resultados apontam para o facto de que o modo como os valores e as práticas organizacionais que envolvem a responsabilidade social são percebidos pode ser considerado como uma determinante contextual da ética dos colaboradores, tendo um impacto positivo ao nível individual de uma organização.

Palavras-Chave: Responsabilidade Social das Organizações (RSO), ética individual, stakeholders,

aceitabilidade ética.

3400 Professional Psychological & Health Personnel Issues 3450 Professional Ethics & Standards & Liability

3600 Industrial & Organizational Psychology 3650 Personnel Attitudes & Job Satisfaction

8

1.Introduction

Recent corporate scandals and further evidence of dubious conduct of top leaders in business worldwide are nowadays broadcasted on the news with an alarming frequency. Increasingly we hear about cases where business leaders or their companies have been associated with amoral or even immoral practices. In fact, especially since the 1950’s, the gap between society’s expectations of ethical business behavior and the actual ethical conduct of business organizations has widened (Odom and Green, 2003).

If, on one hand, our society has become more demanding towards their constituents and there is more peer pressure for the observation of human rights and environmental awareness, on the other, the business market is also increasingly more competitive and disposable, fostering the adoption of some extreme and questionable measures more often than ever before. Recently several organizations and leaders within those organizations have faced civil and criminal charges as a result of conduct that was unethical and often illegal. Enron, WorldCom, Société Générale and Gap, to name a few, were in the headlines for all the wrong reasons, ranging from financial fraud to human rights’ violations. These scandals generally have several undesirable consequences not only on the image and performance of a given organization, such as damage to the reputation of their products and brands and effective financial loss, but it also touches the balance of their internal environment affecting the workers themselves. Some data compiled by Odom and colleagues (2003) states that in 1997 the Ethics Officer Association found that 48 percent of managers and executives reported having been involved in an illegal or unethical issue in the past year and 57 percent reported that they found the pressure to be unethical greater than it was five years ago. Criminal and unethical workplace behavior causes losses for the North American industry of approximately $400 billion per year (Wah, 1999), additionally it is in the origin of expensive lawsuits and employees’ wrongdoing accounts for almost 30 percent of the bankruptcies in the USA (Pawloski & Hollwitz, 2000). In conclusion, unethical behavior is expensive for organizations, detrimental to their long-term survival and the general economy – and yet it still takes place. Looking at the contradictory ethical manifestations in the business world, Collins (1994) has claimed that organizational ethics is a contradiction of terms and others have argued that concepts like Corporate Social Responsibility are too loose to the point of being meaningless (Ludesher & Mahsud, 2010), but discounting some theoretical controversies, it is undeniable that ethics is now part of the business world. Indeed, the current research takes a different approach, using existing studies for guidance and examining the associations of CSR with important outcomes at both the organizational and individual levels.

The events above-mentioned and many more have had one positive outcome if none other: they have forced society to raise awareness of a company’s, for the best as for the worst, being that it is today one of our most prominent institutions and we all, in one way or another, benefit or are affected by many of them in our daily lives. Beyond their bottom line or allied to it, some companies started assuming an extended role and additional responsibilities towards their organizational members and towards their

9

external environment, both in the physical and social spheres. For instance, we hear more and more organizations expressing intentions of taking a more proactive role in their social and environmental surroundings in press-releases, events and other media channels.

Due to legal impositions and/or the influence of their external environment, whichever may be the most pressing motivations behind it, the fact is that many organizations have started to develop and implement programs and measures specifically aiming at fostering ethical behavior among their organizational actors (Weaver, Treviño & Cochran, 1999). These “ethical infrastructures” (Tenbrunsel, 2003) will then act as regulators of employees’ ethical conduct, and through these ideally three functions are made possible: 1) to communicate organizational values, principles and norms, 2) to monitor internal practices and 3) to punish behaviors accordingly.

One example of these ethical infrastructures is the code of ethics, which can be defined as an organized list of explicit recommendations on the type of ethical conduct that is desired and expected from the individual workers, a professional group or sector of a given organization (Crane & Matten, 2007). Yet, even if the codes of ethics are supposed to target effects at the individual level, the literature about their proven influence in the attitudes and behaviors of the workers is sparse and controversial (Cassell, Johnson & Smith, 1997).

In a study that represents an interesting exception, Somers (2001) analyzes the association between the codes of organizational ethics and the individual ethics of their respective employees, comparing the frequency of non-ethical behaviors (more precisely, wrongdoing) in organizations with and without a code of ethics. The results show that the workers in organizations with formal codes of ethics, comparatively to the ones working for organizations without such formalized or explicit codes, reported less internal practices of dubious ethical nature.

If this seems to evidence a moderate effect of the influence of ethical norms on individual behavior, then it leads us into questioning the potential effect that the perceptions of organizational practices held by their members can have when they are confronted with ethical choices. In fact, where ethics is concerned actions speak louder than words (Treviño & Brown, 2004). It is therefore very likely that the choices and decisions made by organizational actors are, to a certain degree, influenced by the way they cognitively make sense out of the organizational standards in matters related to the ethical nature of their practices, especially when these are linked together within a shared working context.

Aligned with the growingly-accepted perspective that businesses are expected to guide their conduct by socially-relevant values, another type of ethical infrastructure arose, one which attempts to connect the individual ethics with institutional standards in and outside the company: Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is now entering the organizational lexicon in this field and inspiring a more scientific and measurable approach to it.

Thus, our current study chose as the main problem to explore the link between what we have known as CSR and individual ethics in the context of the Portuguese corporate sector. In the next sections of the Introduction, we give you an account of the state of theoretical and empirical research on CSR,

10

organizational and individual ethics, highlighting breakthroughs made by some authors and gaps in a field that is being discovered almost in parallel by the corporate sector and academia. Afterwards we state our three objectives of the study, which include 1) a better understanding of the constructs we are studying, namely in the complexity of their sub-dimensions, through the creation and application of an integrated measurement tool, 2) the empirical study of the relation between CSR and individual ethics in Portuguese companies and finally 3) relate the main variables to other socio-demographical variables known for having an effect on individual ethics. Furthermore, we present as our main hypothesis that the more respondents perceive CSR features in their company the less they will tend to accept ethically dubious corporate conduct and test as well a moderation effect of organizational commitment on this relationship. In the next section, Method, we present the sample, the experiment procedure and each of the variables at study, we then present the Results, starting by the preliminary factor analyses of the main variables, their relations and the effects of the additional variables. In the Discussion, we review the results in light of our initial hypotheses and the literature supporting it, including the theoretical and practical implications of our findings and limitations and future recommendations. Finally, we conclude with an overview of the initial problem, the main findings brought by this study and future direction.

1.1. Corporate Social Responsibility

On a wide range of issues corporations are encouraged to behave in a socially responsible fashion, it’s well established by now, but the dilemma is that in both the corporate and the academic world there is still some uncertainty as to how CSR should be defined, not for lack of definitions but rather due to the diversity of the existing ones. The definitions of CSR more commonly found show that there is nothing new at a conceptual level; indeed the business world has always had social, environmental and economic impacts, been concerned with stakeholders and dealt with regulations (Dahlsrud, 2008). However, due to the globalization, the context in which business operates keeps on changing: new stakeholders and different national and international legislation set new expectations and change how the social, environmental and economic repercussions should be optimally balanced in decision making processes, and with this the understanding of CSR keeps evolving.

Starting with the awareness that large organizations are vital centers of power and decision and that their actions strongly affect the lives of their employees, Bowen (1953) was the first to invoke CSR, referring to the responsibilities which businessmen should assume outside the economic sphere (i.e., beyond profit). Ideally, this responsibility would be proportional to the dimension of the social power of an organization (Davis, 1960).

This argument was not so easily accepted at first, especially by Milton Friedman (1970), strong supporter of the free economics principles, which argue that an organization’s sole responsibility lies in continually increasing its profit within the legal limits of its conduct. But soon others realized that it would be possible to be socially responsible while at the same time maximizing profit (Drucker, 1984).

11

According to a group of recognized European researchers in the field, one of the most consensual and comprehensive definitions of CSR portrays it as: “the extent to which and the way in which an organization consciously assumes responsibility for – and justifies – its actions and non actions and assesses the impact of those actions on its legitimate constituencies” (Habisch & Jonker, 2005, p. 7). This definition highlights the fact that CSR means in other words an organization’s commitment towards its different stakeholders (Harrison & Freeman, 1999).

Trying to capture it from different perspectives, among the multiple CSR definitions, some refer to its various dimensions and one of the most common approaches makes the distinction between internal and external CSR policies. Internal policies refer to the way a corporation conducts the day-to-day operations of its core business functions, while the external ones account for its engagement outside of its direct business interest(s). Internally, organizations focus on education, remuneration and benefits or medical assistance and they run Human Resources (HR) or extended insurance projects; and externally, they invest in social and ecological projects through donations, volunteer work and partnerships with social institutions and related organizations (Silva, 2005). On a study by Bird, Hall, Momentè and Reggiani (2007), the market values the most when companies satisfy minimum requirements in the areas of diversity and environmental protection and when they are proactive in the area of employee-relations. By coupling internal and external CSR, we not only get a better grasp of the different kinds of activities under the umbrella of CSR, we also see that corporations have not only financial commitments to their shareholders, employees and consumers, but also social and environmental commitments to them, as well as to the communities affected by their activities (Jones, 2010).

To acquaint the reader with the Portuguese reality, the President of RSE Portugal (a CSR association to support the Portuguese organizations) mentions that internally the organizations’ focus has been mostly on security and health measures and on professional skills building among current employees, whereas externally the most visible advances have been in the area of volunteer work and sponsorships to social causes and NGOs as well as applying for national and international networks in the field (Mendes, 2005). This dichotomy also accounts for the multiple stakeholders’ focus, may they be suppliers and media on the external side or employees and their families on the inside.

Some authors have also started to link the construct to other more or less overlapping, such as stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984), which enlarges the scope of organizational impact beyond the shareholder circle, organizational citizenship (Matten, Crane & Chapple, 2003), elaborating on the legal role a corporation plays in society, or corporate social performance (Swanson, 1995), which nowadays translates into social reports, accreditation seals (e.g., SA8000) and the presence in the stock exchange - Dow Jones Sustainability Index (for a review, see Fisher, 2004). These have enables businesses to measure their advances in the arena of CSR and serve simultaneously as communication tools to their stakeholders and to society in general. Moreover, in our opinion, they give evidence to the possibility of CSR being a multi-dimensional construct, and justify the reason why it is still so difficult to condense, distinguish and unify all the network of concepts it is associated to (Carroll, 1999). This has given us the

12

motivation to study more deeply what CSR represents and looks like in a sample of Portuguese companies, which will be the first objective of our study.

When you are updated with the news on the television or in some magazine of the specialty, you have probably noticed that there is an increased hype around CSR in the business world and this may very well be due to the managers’ awareness that this new trendy construct can also bring value to the organizations. In a time of value crisis and generalized mistrust in corporations, CSR seems to be a good strategy to keep or improve a corporation’s reputation and public image, since these two aspects are strongly associated with the external evaluation of CSR levels (Waddock & Graves, 1997). This happens because, given a choice, most people prefer to work for and do business with companies that are honest, fair, reliable and considerate (Cacioppe, Forster & Fox, 2008).

Moreover, due to CSR’s multi-disciplinary roots, correlational studies have flourished in the field of management and marketing (e.g., Crouch, 2006), in order to identify the potential benefits of a CSR strategy. Most of the researchers have focused on the association between CSR and the financial performance of organizations (Garriga & Melé, 2004) and recently studies already started focusing on the impact of CSR on different organizational stakeholders such as consumers (Brown & Dacin, 1997; Maignan, 2001), stockholders (Orlitzky, Schmidt & Rynes, 2003) and job applicants (Backhaus, Stone & Heiner, 2002; Montgomery & Ramus, 2007), but in most cases a causal link is still to be determined. However easily predicted the relation between ethics and CSR still lacks scientific development as very few studies assume an intra-organizational outlook. Attempting to clarify this relation, Fisher (2004) sums up the four viewpoints discussed in the literature. The first one states that CSR refers to a set of assumptions on equivalent grounds with individual ethics, except that they are valid in the organizational context, since companies do not have ethics, they have instead social responsibility (Schermerhorn, 2002). CSR would thus be an organizational attribute and ethics an individual one.

A second approach, outlined by Boatright (2000), establishes a similar parallel between the two terms, but on the level of their impact. According to this author, ethics would take charge of the individual’s conduct within the organizations, whereas CSR would care for the interaction between the organizational activity and society in general.

These two views represent the classic approaches on CSR. They incorporate the third approach, the reductionist vision of the economic responsibility of organizations (Friedman, 1970), which claims ethics and CSR aren’t associated to each other, because the sole responsibility of an organization is to maximize its profit and only individuals can take on responsibilities of a moral and ethical kind.

They also relate to the socio-economic and last approach of CSR (Carroll, 1991), translated into the theoretical model of the Pyramid of Social Responsibility. According to this model, the company progressively takes in charge responsibilities of economic, legal, ethical and philanthropic/discretionary domains. The two first kinds of responsibilities are required by society since, even if a company is perceived as a basic economic institution driven by profit, it must still abide by the laws that regulate its conduct while fulfilling its mission. As to its ethical responsibilities, society hopes that the company follows

13

a set of socially established norms, without them being mentioned in the law. Beyond these, the company can also take additional voluntary (philanthropic) responsibilities, which do not come from society’s expectations but are socially desirable, and thus depend solely on the manager or CEO’s judgment and will.

Despite the divergent views presented above, one can easily conclude that, contrary to what Friedman (1970) stated, the relation between CSR and ethics cannot be ignored and CSR cannot only bring benefits to society in general, it can also generate an impact within the organization that establishes it, namely in their employees. Conversely, Rupp and colleagues (Rupp, Ganapathi, Aguilera & Williams, 2006) consider that the workers, being a functional part of the organization, also contribute to the CSR environment of their workplace.

In summary, the debate concerning the definition of CSR is still ongoing while the research around it shows several shortcomings, especially in what refers to its effects internally and externally an organization and how it interacts with ethics.

1.2. Business Ethics

One of the central concepts in organizational ethics, linking the individual to his/her working context, is the value, which is both studied and interpreted by philosophers and psychologists. The importance of individual values draws from the fact that they are lasting beliefs which lead to the personal preference for a determined mode of conduct or end instead of another (Rokeach, 1973), so with an ultimate impact in the behavior a person adopts. Among the values an individual acts by on a daily basis are the moral values.

There are two different perspectives on the origin and formation of our moral values: the internal and external one (Straughan, 1983). Based on the internal perspective, values would derive from the individual’s rational thinking, being mostly determined by each one’s unique personality. One example of this perspective would be Kohlberg’s (1981) theory of moral cognitive development. For other authors sharing the same perspective, this type of values derives from our motivations and personal needs, in the search of psychological satisfaction (Rokeach, 1973). In both cases, the individuals internally determine their own values.

According to the external perspective, the individuals would assimilate values from their social context through a process Bandura (1977) called social learning. This process considers that our learning experience derives from a combination of environmental (social) and psychological factors characterized by the retention, motivation and reproduction of a determined observed behavior. Another explanation rooting from this external approach lends from Darwin’s theory of evolution because it states that the moral values are attributes of the most apt humans which were naturally selected amongst our ancestors, as a result of biological and environmental influences (Hastings, Utendale & Sullivan, 2007).

14

These two perspectives on moral values summarize the dualism of the psychological and situational influences on ethical judgment and behavior. On one side, we have individual determinants to ethics, such as the gender (Beu, Buckley & Harvey, 2003), on the other, there is a significant influence of the situational variables, as the classical experiments of conformity (Asch, 1956) or obedience to authority have show before (Milgram,1963), where peer pressure and leadership can lead to unethical behavior. One common external justification in the business world is the bottom-line-mentality. This line of thinking supports financial success as the only value to be considered, promoting short-term solutions that are financially sound on the new, even if they may cause problems to others within the organization or to the organization as a whole. This often leads employees to act unethically and subsequently rationalize their behavior for the greater and ultimate goal of the company (Odom et al., 2003).

The classic belief is that ethics is something personal and thus cannot be legislated or managed, an approach rooted in the internal perspective. But if the context can influence negatively the ethical behavior of the individuals in a company, then it is fair to assume that it can also have a beneficial effect on the employees’ ethics, and some studies have already shown that this can happen through management practices and leadership influence (Carroll, 1978). If larger firms, more resources, dynamic environments and certain industries are the paramount conditions for the upsurge of illegal behavior, it is also possible that certain other company conditions may, on the other hand, foster more ethical patterns of reasoning and behavior (Odom et al., 2003). And as we go from the organizational level to the individual one, the easier it becomes to pinpoint the actions that can affect ethical decision-making and behaviors as well as suggest those that can improve them.

A study by Somers (2001) is a landmark piece of research in this domain for bringing together CSR and individual ethics in an organizational context. Here Somers analyzed whether the presence or absence of corporate codes of ethics would influence the rates of self-reported wrongdoing. Besides confirming the influence on the reported wrongdoing cases, the findings support a double association of the presence of codes of ethics with 1) a higher organizational commitment and 2) three of Carroll’s (1991) dimensions of social responsibility: economic, ethical and philanthropic.

The association between codes of ethics and social responsibility suggests that this latter can act as an organizational incentive or facilitator bearing consequences at the level of the individuals’ ethics. In other words, the perception that an organization guides its activities by a socially responsible conduct and abides by the norms of ethical conduct may reinforce the employees’ commitment towards their organization and, eventually, drive them into more ethical individual reasoning and acting. Similarly, in this study our second aim is to understand if a CSR context can be associated with a more demanding ethical reasoning, when it comes to evaluating organizational conduct that is neither illegal nor commendable.

Rupp et al. (2006) put forward the proposition that as a firm shows increasing or decreasing concern for its broader social impact, and given that these concerns are salient to employees, systematic changes might occur in employees’ job attitudes and commitment to the organization. However, this hypothesis

15

was not empirically tested. One type of organizational commitment seems to be more relevant in the employee-organization relation: affective commitment (Allen & Meyer, 1990), referring to the identification of the employee with the image of the organization, the internalization of its values and objectives and the desire to remain there.

Treviño, Butterfield and McCabe (1998) empirically verified this association and augmented it with suggestions of ways by which managers can improve the commitment of employees through the organization’s ethical context. They can focus on developing a culture that supports ethical conduct and discourages unethical conduct through leadership, rewards systems, codes and norms as well as fostering the goodwill of employees, customers, and the public rather than self-interest.

In this study we were also interested in studying the extent to which employees’ organizational commitment could have a direct influence on the assessment of ethically-dubious conduct and an indirect one on the relation between CSR perceptions and this ethical assessment. There has been some literature evidencing the link between organizational commitment and organizational ethics, namely through the person-organization fit literature (Valentine, Godkin & Lucero, 2002), but not much relating it to the study of CSR, which we were interested to evidence here. For example, if an employee is not so committed to his or her company maybe the fact that he perceives its CSR attributes doesn’t mean that he will assess more negatively specific dubious corporate conduct.

Considering the internal perspective, some attributes of the employees of a more intrinsic nature can also influence their ethical reasoning and make certain individuals more prone than others to be ethical. Past research has shown that certain socio-demographic variables are correlated with ethical judgment and/or behavior. The most cited in the literature are gender and religious beliefs and practices. In regards to gender, after the analysis of seven studies on organizational ethics, Ford and Richardson (1994) have concluded that women are more likely to act in an ethical way than men. Similarly, the evidence from an investigation carried out among undergraduate students (Ameen, Guffey & McMillan, 1996) shows that the female participants were less tolerant than were males concerning dishonest actions within the university context.

Despite the fact that this data is confirmed by most studies, there is a lack of ecological validity in this research applied to the organizational context. In fact, since the samples are mostly composed of students, these gender differences may not reflect reality in the business world (Deshpande, 1997). As for religious beliefs and practices, there is sparse and old data (Tsalikis & Fritzsche, 1989) on American citizens, indicating that the people who attend religious events or express religious beliefs are slightly more ethical than those who do not. In order to collect more conclusive data, it is also necessary to take into account the effect of these, among other, variables within the organizational context. The third and last objective of this study was thus to explore some internal factors that may foster more or less ethical reasoning in the respondents.

16

2.Objectives and Hypotheses

One of the goals of this research is to explore the internal perspective of CSR, which has been somewhat neglected over the external one, more in touch with stakeholders such as consumers, public opinion or job applicants. If CSR is strongly associated with organizational management and marketing, individual ethics within the organization has been traditionally studied either in the domain of philosophy or the one of applied psychology, which thus highlights the need for converging research that may encompass both constructs.

The first objective of this study is then to create a tool which enables us to tackle the multi-dimensionality of CSR as a representation of the various stakeholders of an organization, integrating as well a measure of individual ethics. Secondly and more importantly, we aim to better understand the relation between perceived CSR and individual ethics. Finally, we will also further explore the association between ethics and the above mentioned socio-demographics (i.e., gender and religious orientation), among others. This way we will be analyzing in the same study some of the external and internal factors that may correlate to individual ethics in the organizational context.

Framed by the exploratory character of this research, we propose the main hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. Perceived CSR will be inversely associated to the acceptability of ethically dubious organizational practices. In other words, the more the organization is perceived as socially responsible, the less their employees will accept poor ethical corporate behavior.

Since there was already previous evidence of the overall benefits of organizational commitment and its relationship to ethics (Somers, 2001), we were interested in studying how it correlates with organizational ethics, not only directly, but also as a moderator of the main relationship of the study (i.e., first hypothesis). We predict that high commitment might reinforce the inverse relationship between higher CSR perceptions and lower acceptance of dubious organizational conduct in this way: among very committed employees, this negative association could be stronger, whereas low committed employees might not relate high CSR perceptions to lower levels of ethical acceptance and so this negative relation would be weaker or even inexistent. So we test the possibility of a moderation effect:

Hypothesis 2. Our primary association (between CSR and individual ethics) will be moderated by the employees’ commitment to their organization. Among highly committed employees, the negative relationship CSR-ethics will be stronger and among low committed ones, this would be weaker or even statistically non-significant.

And finally, this study also attempts to confirm evidence from previous experiments on the effect of certain demographics on individual ethics, but does it within an organizational setting: the role of gender and religious beliefs and habits have previously been studied among undergraduate or graduate students

17

and now will be assessed on a sample of Portuguese professionals. Besides those, we have also taken into account three other variables.

Hypothesis 3. The ethical acceptability of dubious conduct will vary depending on certain socio-demographic variables of the respondents (i.e., their religious orientation, gender, age, company seniority and role).

3.Method

3.1. Procedure

The pre-test, which involved about ten persons from various age and academic backgrounds, aimed to measure the face validity of the questionnaire, asking participants to fill it out and submit their remarks concerning the sentence structure and the interpretation and clarity of the questions, as well as any additional suggestions.

From this feedback, we reformulated the final instrument, in terms of language and item selection. The final instrument originally applied (in Portuguese) can be seen in the Annex (Figure 1). It is composed of 4 parts, each pertaining to one or a group of variables at study: 1) perceived CSR (including CSR values and CSR practices), 2) organizational commitment, 3) ethically-dubious corporate conduct and 4) sample demographics.

3.2. Variables and Measures

3.2.1. Perceived CSR.

Although there is a tool based on Carroll’s CSR pyramid model (1991), which was developed by Aupperle, Hatfield and Carroll in 1983 and previously used in organizational context by Pinkston and Carroll (1996), there are several reasons why we opted to build a new and more adequate instrument for the purposes of our research.

Firstly, Carroll’s pyramid is based exclusively on the North American business context and recently it has been claimed that the European reality presents specificities in this domain that do not allow for this generalization (Matten & Moon, 2008). Secondly, this model supports an evaluative approach to CSR, defining the progressive stages or degrees of social contribution manifested by companies, neglecting nonetheless to list concretely the different forms CSR takes and all the areas and stakeholders involved in it. In fact, after reviewing the sparse literature in this field, we concluded that there are very few descriptive CSR studies enabling to uncover its full multidimensionality.

Therefore, to measure the perceived CSR construct we created two scales. One of them identifies the normative bases of an organization through their values (on a scale of 15 items) and the other maps their

18

organizational practices (26-item scale). We will thus represent the sampled companies CSR on two complementary perspectives: the values’ and the stakeholders’ (see below for the detailed description of each). By doing so, we gain a better understanding of CSR perceptions both in their espoused form (what companies formally declare themselves to be) and the in-use form (what they actually do in this area), bearing in mind there is often an expected discrepancy between what we say and what we do (Argyris & Schön, 1974).

3.2.2. Organizational values.

The list of the values to include and its definitions were initially composed from the value statements on the websites of some companies associated to CSR or clearly referencing it there. We also researched among other more or less extensive CSR tools, namely the Indicadores de Responsabilidade Social Empresarial do Instituto Ethos (Custódio & Moya, 2008), the self-diagnosis survey by Inspecção-Geral do Trabalho (IGT, 2008), which focuses exclusively on the internal dimension of CSR, the Barómetro de Responsabilidade Social e Qualidade developed by CICE (ESCE-IPS, 2008) and the study undertaken by Moura and colleagues (Moura et al., 2004). In the Annex, you can review the structure and content included in each of these tools (Tables 2 to 4). None of the tools reviewed focused specifically on values, although most were indirectly cited in the items.

Respondents were asked to evaluate the importance of each of the fifteen values in his/her company on a Likert scale of seven points, where 1 corresponds to Value of Low Importance (“Valor Pouco Importante”) and 7 to Value of High Importance (“Valor Muito Importante”). In front of each value in the list, there was a small definition in order to guarantee a common understanding of its meaning by researchers and respondents. One example of the values presented is quality, which is described as aiming to guarantee the best service/product to the [company’s] clients (1.7. “Qualidade: A minha empresa procura garantir o melhor serviço/produto aos seus clientes.”).

3.2.3. Organizational practices.

In order to identify CSR-related organizational practices, we started by making a list of the main stakeholders of a Portuguese organization: the shareholders, the clients/consumers, the suppliers and other commercial partners, the surrounding community, the environment, the competition, the Government and, finally, the employees. From this point on, we reviewed several CSR tools, among which the Ethos indicators (Custódio & Moya, 2008) and the internal CSR self-diagnosis survey (IGT, 2008). Our biggest concern was to include the largest number of CSR-related practices possible, more than to reutilize previously used items, since none of the tools available seemed to be comprehensive or exact enough to suit our research objectives.

19

The respondents had to rate the 26 practices listed on a Likert scale in terms of the degree to which they matched their company’s reality, from 1 being very different (“Muito diferente”) to 7 being very similar (“Muito semelhante”). One example of an item reflecting a CSR practice is the impact of this company’s activity on the environment is limited, in terms of pollution, recycling, etc (2.2. “O impacto da actividade desta empresa no ambiente é reduzido (na poluição, reciclagem, etc)”); an example of an item which does not reflect a CSR practice (i.e., reversed) is this company hides its failures from the public opinion (2.10. “Esta empresa esconde da opinião pública os seus insucessos”). The reversed items were included to avoid leniency effects of rating all sentences on the same points of the scale, either on the lowest or the highest.

3.2.4. Ethical acceptability of organizational conduct.

We listed forty sentences addressing ethically ambiguous organizational practices as a way to measure the degree of ethical acceptability of each one if they were to happen in the respondents’ organizations. We reviewed again all the CSR and organizational tools available, but this time our aim was somehow to reverse or distort the good case practices identified on those studies and surveys. We have also taken into account some lists of dubious conduct, such as lies and deception, breaches of promise, passive corruption, unfair competition, personal advantage, manipulation of communication, intellectual property, insider trading and confidentiality of information (Fassin, 2005; Finegan, 1994; Forsyth, 1980).

The replies were marked again on a scale of seven points, from 1 being totally unacceptable (“Totalmente Inaceitável”) to 7 being totally acceptable (“Totalmente Aceitável”). The sentences were intended to be dubious and some even justifiable under certain conditions in order to make the respondents find their own ethical barometer instead of adopting socially acceptable or common sense positions. Two examples of those are: 1) To omit relevant information to the shareholders of the company, e.g., the result of an unfavorable audit report to the company (4.15. “Omitir informação relevante aos accionistas da empresa (por ex. resultado desfavorável de uma auditoria à empresa”); 2) To dismiss some employees in order to avoid the bankruptcy of the company (4.10. “Demitir alguns colaboradores para evitar a falência da empresa”).

3.2.5. Organizational commitment.

In order to check if there were moderators influencing the association between perceived CSR and ethical judgment, we also included a measure of organizational commitment. The scale we used in this questionnaire is composed of the four items of Allen and Meyer’s affective commitment subscale (1990), previously translated to Portuguese and validated by Tavares (2001b). Since the affective commitment is already strongly linked to other organizational commitment and identification measures (Tavares, 2001a), we did not need to include the full scale.

20

The respondents were asked to rate their agreement with the four sentences now on a Likert scale of five points, where 1 corresponds to totally disagree (“Discordo Totalmente”) and 5 to totally agree (“Concordo Totalmente”). The sentences reflect the affectionate link that the employee establishes with his/her organization, one example of them being: I am proud of working in my company (3.1. “Tenho orgulho em trabalhar na minha empresa”). After verifying that the internal consistency of the four items was good (α= 0.68), we calculated a global indicator of the organizational commitment of the respondents.

3.2.6. Demographic Variables.

Besides the main measures, we included questions which enabled us to better characterize the sample of respondents and, some of which previous research had identified as relevant for the study of individual ethics. These variables are: company seniority (in years and months), role within the company (from CEO to administrative), age, gender, and religious beliefs and practices (active or inactive).

Company seniority still had not been associated to ethics in the literature but from the social learning approach we may infer that the longer the employee is in an organization, the more he/she internalizes and identifies with its values, so it would be interesting to verify this. Similarly, the employees’ age and functional role have so far been somewhat ignored by organizational ethics, due to the usual preference of researchers to inquire managers and other top-level members in the organization. Since this study has chosen to take another perspective and focus on the professionals that constitute the basis of the organization and that are more indirectly influenced by a company’s institutional strategies, these were important variables to keep in the analysis. Concerning the last two demographic variables, we already reported some findings that show that generally women and active religious believers might demonstrate more ethical standards than their counterparts, but the previous studies accused certain methodological flaws, which makes this research an opportunity to revalidate their evidence. Figure 3.1 summarizes the types of variables and the relations among them (hypotheses) expected in this research.

Figure 3.1 – Synthesis of the variables studied and their predicted relations (hypotheses) with each other.

H2

1. Values 2. Practices Internal External Information-managementH3

H1

Dubious conduct on:

1. Relations with the Exterior 2. Community Repercussions 3. Employees’ Rights 4. Recycling 1. Gender 2. Company Seniority 3. Functional Role 4. Religious Orientation 5. Age

Socio-Demographics

CSR

Ethical

Acceptability

Organizational

Commitment

21

3.3. Sample

The research in this domain tends so far to adopt either the perspective of the managerial body (Maignan & Ferrell, 2000), surveying only the CEOs or top managers, or that of job applicants, sourcing undergraduate and MBA students in universities (Berens, Riel & Rekom, 2007). In fact, most studies we’ve encountered either had one respondent per company (the CEO or equivalent) or based their research outside of the company sector, most often at universities or on the public opinion (e.g., a sample of consumers).

Given that one of the objectives of this study is to deepen our knowledge of CSR representations built by the stakeholders who contribute the least to the company’s decisions in regards to CSR orientation, we have chosen to target the common employee in our research.

The sample of our study is composed of 116 employees (56.5% men) of fifteen companies in the Greater Lisbon area, contacted over one month. The mean age of the respondents is 34 years old (SD= 8.9), occupying technical (84.6%) or managerial (15.4%) roles in the same company for about 8 years on average (SD= 9.4).

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Analyses to the Main Variables

Since three of the scales in the questionnaire were being used for the first time and the construct of CSR is, as we have seen, multidimensional, we conducted a principal components analysis with rotation for each measure of perceived CSR (values and practices) and the one on ethical acceptability, in order to better understand its internal structure.

As Social Responsibility (Responsabilidade Social) itself was included as one of the fifteen listed values and it was the most saturated item in one of the components, one of the indicators created was named “CSR values” (α= 0.92), including three other values: Social Development (Desenvolvimento Social), Solidarity (Solidariedade) and Sustainability (Sustentabilidade). This and the other component, designated General Values, can be viewed in Table 4.1 below.

22

Table 4.1 - Factor structure, after orthogonal rotation, of the fifteen items of question n° 1 (CSR values). Principal Components

General Values CSR Values

1o) Desenvolvimento Profissional/ Professional Development ,788 ,128 1g) Qualidade/ Quality ,782 ,307 1l) Participação/ Participation ,774 ,145 1d) Colaboração/ Collaboration ,716 ,265 1k) Inovação/ Innovation ,696 ,332 1b) Eficiência/ Efficiency ,693 ,316 1j) Coerência/ Coherence ,689 ,377 1f) Segurança/ Safety ,686 ,404 1a) Transparência/ Transparency ,643 ,527 1n) Respeito/ Respect ,600 ,468 1i) Credibilidade/ Credibility ,579 ,514 1h) Responsabilidade Social/ Social Responsibility ,293 ,869

1e) Desenvolvimento Social/ Social Development ,275 ,852 1m) Solidariedade/ Solidarity ,230 ,839 1c) Sustentabilidade/ Sustainability ,324 ,823

Explained Variance (Cumulative) 57.13% 66.81%

Internal Consistency

(Cronbach’s α) 0.94 0.92

KMO 0.94

This result alone was surprising because it reveals that the value of CSR is closely associated by the respondents to the surrounding community and the environment, and not so strongly to other areas, and thus seems to be set apart from the core business of organizations and from the other values present, such as quality and professional development.

As for the organizational practices, the factor analysis extracted seven principal components (see Table 4.2 below).

23

Table 4.2 - Factor structure, after orthogonal rotation, of the twenty-six items of question n° 2 (CSR practices).

Principal Components Internal CRS External CSR Info. CSR 4 5 6 7

2w) diálogo com todos os stakeholders ,781 ,166 -,231 ,206

2t) participação nas decisões organizacionais ,747 -,215 ,186

2f) oportunidades iguais de emprego ,701 ,115

2x) recolha de sugestões e opiniões dos colaboradores ,678 ,210 ,156 ,164

2g) liberdade de associação e negociação colectiva ,660 ,247 ,160 ,157 -,221 -,234

2v) fomento da cidadania ,633 ,452 -,233 ,128 ,206

2k) coerência entre princípios institucionais e dos colaboradores ,574 ,465 ,117 -,123 -,118 ,137

2n) aperfeiçoamento continuo dos produtos/serviços ,483 ,409 -,288 ,155

2u) consulta a consumidores/clientes s/ novos produtos/serviços ,480 ,150 ,128 ,204 -,379 ,410

2o) parcerias com os mesmos valores e princípios ,229 ,747 -,253 -,148 ,186

2l) redução do consumo de água e energia ,171 ,739 -,128 -,201 ,213 -,115

2m) origem dos produtos dos fornecedores -,029 ,727 -,139 -,347 ,208

2z) práticas ou tecnologias ambientalmente sustentáveis ,172 ,710 -,138 ,244 ,260 ,133

2c) missão de melhorar a comunidade geral ,341 ,618 -,163 ,121 ,243 -,125

2a) retorno adequado dos capitais investidos ,277 ,579 ,118 ,416 -,218 -,140

2h) insucessos na opinião pública -,108 -,164 ,669 ,145 ,173 ,107

2d) conduta dos fornecedoresa -,139 ,625

2i) confidencialidade da informação s/ colaboradores ,540 -,243 -,203 -,287 -,437

2y) conflitos de interesses de colaboradores -,136 ,525 -,294 ,229

2r) informação disponibilizada aos clientes -,129 -,267 ,516 -,138 ,472 ,230

2b) impacto no ambiente ,272 ,247 ,122 ,712

2j) fugas de informação ,513 -,642 ,215 -,197 ,134

2e) casos de espionagem empresarial ,422 -,623 ,108 ,171

2q) campanhas de publicidade estereotipadas ,112 ,139 -,106 ,656 -,162

2p) investimento em capitais de risco ,287 ,141 ,211 ,740 -,139

2s) formação profissional exclusivamente técnica ,137 -,137 ,893

Explained Variance (Cumulative) 28.8% 39.38% 48.48% - - - -

Internal Consistency (Cronbach’s α) 0.87 0.83 0.67 - - - -

KMO 0.84

Note: The item d) was not included in the third indicator for matters of interpretation and for presenting the lowest communality among all twenty-six items (0,418).

24

From these, we selected three indicators of CSR-related practices with considerable internal consistency: Internal CSR, composed of nine items (α= 0.87; e.g. “equal job opportunities”); External CSR, with six items (α= 0.83; e.g. “knowing the origin of the suppliers’ products”) and Information CSR, also with six items (α= 0.67; e.g. “hiding failures from the public opinion” – reversed item). The two first indicators refer to internal and external practices of an organization, while the last one assembles the practices connected to internal information management, so referring to internal content sometimes exposed to the outside, and mainly consists of reversed-scored items. The final item composition is patent in Table 4.3.

Table 4.3 – Final items included in the indicator of perceived CSR practices.

Factor 1- Internal CSR

2w) diálogo com todos os stakeholders 2t) participação nas decisões organizacionais 2f) oportunidades iguais de emprego

2x) recolha de sugestões e opiniões dos colaboradores 2g) liberdade de associação e negociação colectiva 2v) fomento da cidadania

2k) coerência entre princípios institucionais e dos colaboradores 2n) aperfeiçoamento continuo dos produtos/serviços

2u) consulta a consumidores/clientes s/ novos produtos/serviços

Factor 2 – External CSR

2o) parcerias com os mesmos valores e princípios 2l) redução do consumo de água e energia 2m) origem dos produtos dos fornecedores

2z) práticas ou tecnologias ambientalmente sustentáveis 2c) missão de melhorar a comunidade geral

2a) retorno adequado dos capitais investidos

Factor 3 – Information CSR

2h) insucessos na opinião pública

2i) confidencialidade da informação s/ colaboradores 2y) conflitos de interesses de colaboradores

2r) informação disponibilizada aos clientes 2j) fugas de informação

2e) casos de espionagem empresarial

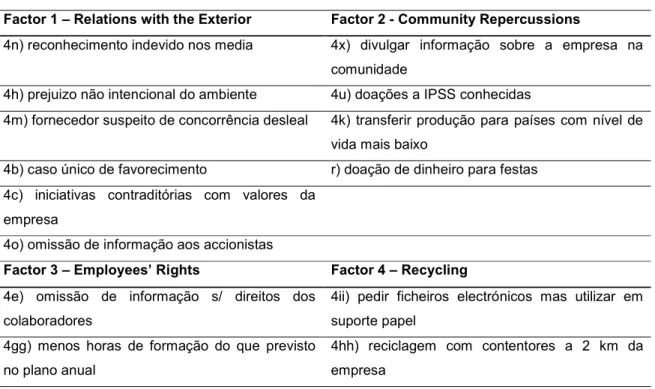

Regarding the ethical acceptability of organizational conduct scale, the four indicators identified were: 1) Relations with the Exterior, composed of six items (α= 0.8; e.g. “undue recognition in the media”); 2) Community Repercussions, with four items (α= 0.64; e.g. “money donations to parties”); 3) Employees’ Rights, with two items (α= 0.6; e.g. “less training hours than in the year plan”) and 4) Recycling, with two items (α= 0.56; e.g.: “utilize paper when electronic files are available”). For a full list of the items integrated in each indicator, see Table 4.4, and for the final item composition refer to Table 4.5.

25

Table 4.4 - Factor structure, after orthogonal rotation, of the forty original items of question n° 4 (ethically-dubious corporate conduct).

Principal Components

R.E. C.R. 3 4 5 E.R. 7 R. 9 10 11 12 13 14

4n) reconhecimento indevido nos media ,780 ,213 -,125 ,128 ,153 ,143 4h) prejuizo não intencional do ambiente ,744 ,143 ,198 -,107 ,242 -,133 4m) fornecedor suspeito de concorrência desleal ,724 ,279 ,156 ,119 ,125 4b) caso único de favorecimento ,637 -,113 ,109 -,129 ,114 ,265 ,271 -,337 ,144 -,224 4c) iniciativas contraditórias com valores da empresa ,561 -,100 ,132 ,254 -,244 -,259 4o) omissão de informação aos accionistas ,484 -,231 ,153 ,395 ,121 ,160 ,209 -,127 ,216 4x) divulgar informação sobre a empresa na

comunidade ,765 -,105 -,172 ,201 -,108 -,135

4u) doações a IPSS conhecidas -,181 ,758 -,173 ,109 -,145 ,141 ,202 ,138 4k) transferir produção para países com nível de vida

mais baixo ,384 ,548 ,152 -,158 ,135 -,257 ,166 ,243 ,233

4r) doação de dinheiro para festas ,109 ,485 ,250 ,359 -,426 ,236 ,275 4y) declinar projecto social por um mau timing ,208 ,305 ,129 -,156 -,212 ,291 ,224 -,296 ,230 ,131 ,280 4s) tomadas de decisão exclusivas da direcção -,130 ,760 ,105 ,165 ,163 -,114 ,161 -,105 4q) excluir candidata grávida de 6 meses ,211 -,185 ,672 ,135 ,183 ,104 ,104 4z) optar por um novo fornecedor a mais baixo custo ,117 ,226 ,522 ,119 -,143 -,404 -,119 ,317 ,148 ,251 4nn) ter candidatos com + de 40 anos ou

desempregados há + de 2 anos -,277 ,108 -,415 ,348 -,330 -,153 ,232 ,102 ,226 ,159 -,288

4bb) patrocinio de eventos desportivos em vez do

ginásio local ,118 ,762 ,130 ,118

4ff) falta de respeito a um colega ,372 -,152 -,134 ,623 ,163 -,101 ,100 ,184 4g) sistema de recompensas baseado na antiguidade ,130 ,124 ,726 -,159 4ll) dumping para vencer a concorrência ,280 -,177 ,599 ,165 ,234 -,184 ,208 4t) oportunidades de carreira abaixo da concorrência -,154 ,126 ,499 ,161 -,312 ,272 ,442 ,166

4w) opção entre a carreira e a esfera pessoal ,283 ,344 ,445 ,169 -,223 ,178 -,178

4e) omissão de informação s/ direitos dos

colaboradores ,117 -,118 ,147 ,787 -,147

4gg) menos horas de formação do que previsto no

plano anual ,254 -,296 ,181 ,383 -,105 ,518 ,231 ,109 ,142

4p) colaboradores sem vínculo contratual ,203 ,236 ,154 ,365 ,328 ,242 ,281 -,299 ,176 -,226

26

4d) selecção da candidatura de um amigo ou

conhecido ,215 ,204 ,278 ,483 ,111 ,224 ,375 -,185 ,121

4ii) pedir ficheiros electrónicos mas utilizar em suporte

papel -,168 ,185 ,816 ,125

4hh) reciclagem com contentores a 2 km da empresa ,230 ,207 -,255 ,714 -,188

4mm) contratar gestor da concorrência ,115 ,114 ,803 ,142 ,213

4a) oposição ao sindicato/comissão de trabalhadores -,116 ,815 ,116 4aa) doação de computadores e material de escritório

em mau estado ,162 ,851 ,116

4dd) receber apoios de organismos governamentais ,152 ,164 ,163 ,167 ,397 ,531 -,260 -,232 4v) voluntariado sem condições materiais e/ou

financeiras ,183 ,205 ,793 ,117 -,170

4ee) postos de trabalho exclusivos para candidatos do

centro emprego ,125 ,862

4cc) reduzir custos com inovação ,196 ,413 -,144 -,150 ,130 -,392 -,104 -,262 ,469 4jj) aparelhos de alto consumo energético com boa

relação qualidade-preço ,107 ,201 ,124 ,114 -,134 ,113 ,813

Explained Variance (Cumulative and in %) 13.43 21.62 27.73 33.37 38.53 43.11 47.49 51.55 - - - -

Internal Consistency

(Cronbach’s α) 0.80 0.64 0.5 0.35 0.45 0.6 - 0.56 - - 0.44 - 0.34 -

KMO 0.58

Note. The items 4y, 4nn, 4w, 4p and 4d (in Italic) scored loadings below 0.5 in every component and thus have been excluded from analysis because they weren’t considered representative enough to be part of any component. From the components extracted, four were the most meaningful and they were designated as follows (highlighted with a bold Cronbach’s alpha): Relations with the Exterior (component 1); Community Repercussions (2); Employees’ Rights (6); Recycling (8).