Social Cryptocurrencies: social finance

organizations at the new era of digital

community currencies

EGOS 2018 - Sub-theme 12: Surprising Organizations, Unexpected

Outcomes: The Influence of Alternative Organizational Forms on

Social Inclusion

Eduardo H. Diniz* (eduardo.diniz@fgv.br); Adrian K. Cernev* (adrian.cernev@fgv.br);

Fabio Daneluzzi* (fdaneluzzi@gmail.com); Denis Rodrigues* (denrogp@gmail.com).

*Fundação Getulio Vargas, Brazil

Abstract

We proposed an investigation on the emergent phenomenon of cryptocurrencies by studying those with explicit social or environmental goals, that we called social cryptocurrencies. To perform this study, we adopt a socialmaterial approach based on a combination of two elements identified with the social and the material aspects of a digital platform, respectively, governance and architecture. From the combination of these elements, we define a set of categories used to classify a selected sample of 18 social cryptocurrencies. Within each category, we then discussed topics that we considered critical for the management of social cryptocurrencies – scale, scope, stability and interoperability – since they seemed to be taken differently in each of the distinct universes that originated the concept of social cryptocurrencies: the community currencies and the cryptocurrencies. We found that the sociomaterial approach provides good foundations for explaining the characteristics of social cryptocurrencies and the entanglement between governance and architecture is clearly noticeable by the analysis of the studied cases. It seems to be natural that, for social cryptocurrencies, the more open the governance structure, the more probable to adopt a more open platform architecture. We also used the categories to explain the great deal of uniformity among the investigated currency projects, concerning the critical issues taken from the literature.

Introduction

A phenomenon known for decades and observed in different countries, community currencies are generally regarded as private and mostly non-regulated tools for fighting social exclusion and encouraging local development (Blanc, 2011). The same way as other payment systems, community currencies are also adopting digital payment platforms to save costs for launching and maintaining a currency, achieving economies of scale and better managing the circulation of money within the community (Diniz et al. 2016; Cassoni & Ramada, 2013; Schroeder, 2013).

The emergency of the cryptocurrencies, an innovation that combines distributed payment systems with new forms of currency, has become a particularly important case in the field of digital payments in general, and it is also becoming a relevant subject for the study of community currencies (Alcantara & Dick, 2017). If community currencies grow their market relevance while increasingly being subsumed into a digital format (Gartner, 2013), it is expected that blockchain technologies will impact these local payment systems even more (Gartner, 2017).

Cryptocurrencies share with community currencies a neglected attention from regulators and the more traditional financial market. Not controlled by central banks and not requiring commercial banks as intermediaries (Ali, Barrdear, Clews, & Southgate, 2014), cryptocurrencies as well as community currencies, have a conflicting history with monetary authorities, that either ignored them as irrelevant or threat them with regulatory or punitive actions (Seyfang & Longhurst, 2016).

As communities around cryptocurrencies have expanded, the security standards used in this global currency have steadily increased, attracting millions of users from all parts (Scott, 2016). The blockchain mechanism is mostly responsible for the cryptocurrencies dissemination. Blockchain is also raising new issues for the concept of community currencies itself. First, it made possible to create a

payment community including people from the whole planet, such is the case of Bitcoin, challenging the much more limited and geographically constricted concept of community considered in the community currencies field. Second, it makes accessible at reasonable cost a secure, open and distributed mechanism to develop payment systems, a long time expected solution for most problems found while implementing community currencies systems that were limited to the usual cost and security trade-off.

With the emergence of the cryptocurrencies phenomenon in line with the concept of blockchain as an alternative to established technologies for solving social problems (Schweizer et al. 2017), we highlight a particular group of community currencies that we will be named in this paper as "social cryptocurrencies". Diniz, Siqueira & van Heck (2016) have highlighted some of the characteristics of social cryptocurrencies, pointing their dynamic technological architecture, the type of transactions they provide and some aspects of the governance behind their operations, but did not explore the potential relations between the technical characteristics of currencies’ platforms and the social governance characteristics of organizations that maintain them.

We adopt sociomateriality as our theoretical and conceptual base to analyze the constitutive entanglement between technology and organizational structure (Leonardi, 2015). As pointed by Burrell (2016), technology constitutes the material artifact that shapes the social structure behind ICTD (Information Technology for Development) projects. This sociomaterial approach has been adopted in previous studies to analyze characteristics of blockchain infrastructure (Jabbar & Bjørn, 2017) and cooperative work in digital organizations (Lund & Venäläinen, 2016), but to the best of our knowledge, no other study has tried to interpret the emergence of social cryptocurrencies using the theoretical lenses of the sociomateriality.

To articulate the material characteristics of the social cryptocurrencies platforms with the social aspects of the organization behind them, we analyze the technical elements related to the blockchain architecture with the social governance adopted by each of them. In this sense, we considered architecture and governance as the critical elements of a platform ecosystem (Tiwana, 2014) to interpret how the material aspects of the community currency technological design is related to its governance social structure. From this analysis we propose sociomaterial categories for social cryptocurrencies drawn from three blockchain architecture related dimensions – public, private and permissioned – and two governance related dimensions – central and shared.

Following the sociomaterial approach, we also discuss the implications of a particular technology adoption, the blockchain platform, to the goals of a social finance organization. We make this discussion bases on four main issues – scale, scope, stability and interoperability – faced by community currencies when adopting blockchain platforms, since these issues can pose challenges for social cryptocurrencies to achieve their social goals.

In order to achieve the objectives of this research, we collected and analysed secondary data, including documents and websites, from 18 selected social cryptocurrencies to identify the main characteristics of the adopted blockchain architecture and also to understand the social governance characteristics of them. We discuss the scale, scope, stability and interoperability of each analysed category of social cryptocurrency to evaluate the challenges they face to achieve their original social purpose.

Social Cryptocurrencies

Our goal is to examine how organizations adopting social cryptocurrencies contribute or fail to contribute with the improvement of their social mission – i.e. create conditions to improve the sense of belonging to a community and acquire real capabilities to live with dignity and exercise their rights. Although community currencies have a long history of studies proving their ability to promote social inclusion, their biggest limitation have been the low capacity do scale this inclusion power to larger groups of people (Seyfang & Longhurst, 2013). Cryptocurrencies, on the other hand, are meant to reach higher scale, but have no proven ability to improve social inclusion (Scott, 2016). What would happen then, when social finance organizations embrace cryptocurrencies technology? Will they finally improve their scalability or will risk their social mission?

As we investigate organizations responsible for creating and managing social cryptocurrencies, we need to understand how their variation in scale, scope and geographic boundaries can affect their social goals. Next we explain these elements.

The same way Microfinance Institutions (MFI) have a dual goal, social and financial (Marconatto et al., 2016), community currencies have also an intrinsic financial goal most times associated to some concept of “social goal”. Place & Bindewald (2013) made an effort to classify community currencies goals in three dimensions – economic, social and environmental – however these classifications can be confusing.

According to a guideline for designing, developing and delivering community currencies (CCIA, 2015), while the commercial benefits of connecting underused assets with unmet needs is a primary goal of such currencies, at the same time a crucial element of the early stage of planning a community currency is setting its goal, to guarantee that they can bring significant benefits to their users. This means that together with the primary economic (financial or commercial) goal, community currencies can be designed to achieve other categories of goals (social, environmental, etc.).

If the economic goal is always clear and there is some vagueness in the social goal definition for community currencies, it is easier to identify the ones that have no interest in promoting social causes. Bitcoin, for example, is a cryptocurrency with no statement supporting a clear social goal (Nakamoto, 2008) and thus could not be classified as a social cryptocurrency. On the other hand, the D-CENT Project– Decentralised Citizens ENgagement Technologies – has developed a Social Digital Currency Pilot “to link best practices from the Complementary Currency domain (…) and, as appropriate, further empower citizens with new technological breakthroughs in the world of digital payment systems such as crypto-currencies” (Lucarelli et al., 2014:44). In this project, a toolkit to build “blockchains for the social good” resulted in a number of pilot cryptocurrencies that clearly states their social and environmental goals, such are the cases of projects developed in Iceland (Betri Reykjavik), Finland (Helsinki Time-bank) and Spain (Eurocat). Other projects outside of Europe have also combined cryptocurrencies technology with social goals, such is the case of Cadastral, from Ghana (Bates, 2016). For the purpose of this paper, we will consider social cryptocurrency only the ones which go beyond the primary economic goals and have clear social or environmental statement as a goal for the currency project.

Scope

It is not without a reason that one of the synonyms for community currency is “local currency”. Local, in this sense, is associated with the traditional limited regional scope for most community currencies. And, of course, this limitation in scope is tightly associated with a limitation in scale, considering the only users for the currency within a certain restricted community.

This limitation is scope and scale that characterizes community currencies can be also associated with the niche-building processes of setting up networks, managing expectations and creating local significance provided by the grassroots organizations that usually promote them (Seyfang & Longhurst, 2013).

On the other hand, cryptocurrencies are meant to be global. In an investigation on digital community currencies, Diniz et al. (2016b) have explored a category of social currencies characterized by greater territorial coverage. One of the considered cases, Auroracoin, a social cryptocurrency from Iceland, was designed to be used all over the country. Even if we are talking about a small country (Iceland has around 330,000 inhabitants), this first country-based cryptocurrency launched in 2014 counts with at least 33,000 users1, which is 10% of the country’s population, a number many times bigger than most

traditional community currencies.

Studying a Brazilian community currency implementation within the scope of a whole city, Nascimento (2015) observes the risk of weakening social bonds as the scope goes beyond the limits of a group sharing the same community sense, a problem that could compromise the success of social goal of a community currency. For the author, that project presented some flaws in the traditional community feelings and shared understanding about concepts such as “local belonging” and “solidarity” in other community currency implementations. So, while the cryptocurrency format can expand the scope and scale of a community currency, it might compromise the expected community feelings and thus risking the social goals.

Adoption and scale

1 Auroracoin Rich List with at least 1 USD value in the wallet at

Although it is possible to claim that community currencies are steadily growing in importance in the last 30 years, having reached a number of thousands of projects in the last few years (Gartner, 2017), they are also well known by their counter cyclical characteristics, meaning that they tend to be adopted when economic crisis arises and unemployment and lack of access to the mainstream financial systems close the doors to the more vulnerable part of the population. This counter cyclical behavior can be observed in two very clear ways.

First, investigating the Swiss Wirtschaftsring (“Economic Circle”) credit network, or simply WIR, founded in 1934 – the most ancient community currency still in operation – Stodder (2009) found out that, unlike the ordinary money, WIR money is negatively correlated with GDP in the short run. The author confirms the counter cyclical by explaining that individuals are cash-short in a recession, and economize by greater use of WIR-credits.

Second, it is possible to measure the expansion of community currency projects during periods of crisis. The most remarkable case is the Argentina crisis from 2001 (Gómez & Dini, 2016), when the country had five different Presidents in only two weeks. At that time, there was an explosion of the barter schemes in the country and, from a single first 23 member “barter club” in 1995, a “6-7 million group of people recognized themselves as current or potential users of the system in 2001” (Primavera, 2004). Although a better understand of the Argentinian phenomenon is still needed, the number of barter users decayed along time, while the economy had some level of recovering, reinforcing the idea of the counter cyclical adoption of an alternative financial system when the mainstream system (mostly regular banks) does not provide enough for all the people who needed financial services.

The first cryptocurrency was created in the turmoil of the biggest world financial crisis ever. However, the great movement that have emerged in more than 1,000 different cryptocurrencies since then, although still at its infancy, seems to be different from the counter cyclical movement of the more traditional community currencies. One sign of this difference is the recent incorporation of Bitcoin into the mainstream future market in the Chicago Board Options Exchange. Although this is still a not very clear scenario for an ongoing process, it is completely different from whatever had happened to any other community currency in their more than 80 years of history. Thus, the question to be made is, considering the expansion of cryptocurrencies, and among them, the ones labeled as “social”, will them be trade as future options? If they go towards this direction, it is possible to think about social cryptocurrencies being more stable along time than their similar, but countercyclical, community currencies.

Price stability

Many community currencies back their price with a fiat currency in order to guarantee some level of stability and offering to users a clear way to value them. Backing is a design feature of a currency which guarantees its long term purchasing power. This means that the issuer of a currency guarantees the exchange of a currency for either another currency or a commodity (CCIA, 2015). The backing principle can be used to limit the issuance of a currency as well as to infuse trust in project that usually does not have government endorsement. Backing can be official currency, material (gold, silver or collateral), or immaterial (government bond or backed by the community). Time (Molnar, 2011) and energy (Joachain & Klopfert, 2012) are also physical units possible to be used for backing community currencies.

Different from most community currencies, cryptocurrencies were created to be used without backing correspondence to any fiat currency. The academic discussion about the price stability of cryptocurrencies is usually split into two opposing groups (Josavac, 2017). Critics find that the decentralized feature of virtual currencies is a significant disadvantage of the technology because it seriously reduces the flexibility to respond to economic shocks. In contrast, supporters argue that centralized operations by monetary authorities are actually inducting financial instability.

Price stability could be achieved by dynamically rebasing the outstanding amount of money: the number of cryptocurrency units in every digital wallet is adjusted instead of each single unit changing its value. The monetary base adjustment can have neutral impact on the overall wallet wealth, as it does not introduce any arbitrary distortion into the intrinsic value dynamics of the wallet. The adjustment is based on a commodity price index determined with a resilient consensus process that does not rely on central third party authorities (Ametrano, 2016).

Interoperability

Created to serve a unique group of users inside one particular territory, community currencies have been since long dreamed, and never effectively implemented, about promoting exchanges between

communities alike, however geographically apart. On the other hand, there is some expectation that connecting different projects in different locations could empower them. This is particularly important when considering the small scale of most community currencies and consequent weakness to maintain the currency operation. In this sense, if they could include some level of interoperability, they potentially would strength their power in front of the regulatory authorities, their level of acceptance and their price stability.

Two recent experiences are worth mentioning, although none of them have enough time to be fully analysed. The first one is the E-Dinheiro case in Brazil, led by Banco Palmas, where one single mobile money platform is being shared and adopted by dozens of different local community currencies spread out over the country, providing full interoperability among them (Siqueira et al., 2017). The second is the Bancor Protocol that promises to integrate globally “up to millions” of different community cryptocurrencies under one single protocol, aiming to give them price stability and exchange power (Hertzog et al., 2017).

Thus, we propose a deeper discussion about the social cryptocurrencies seeking to understand how the features of these currencies can affect the characteristics of organizations behind them. We hypothesize that cryptocurrencies have some intrinsic characteristics that can influence the objectives and scope of their maintainers. Some of these characteristics are:

cryptocurrencies allow to articulate communities more dispersed geographically, thus expanding community boundaries beyond the traditional geographic limits that characterizes most community currencies (Schroeder, Miyazaki & Fare, 2011);

cryptocurrencies allow to expand the scale of operation of traditional community currencies in terms of the number of users and transactions, expanding their scalability to levels not usually found in the universe of community currencies (Seyfang, 2001);

cryptocurrencies allow to articulate different communities with different currencies that can be mutually backed, thus expanding inter community bonds through the exchange of their particular currencies (Hertzog, Benartzi &, Benartzi 2017);

cryptocurrencies can be more stable over time (Josavac, 2017), and may leave the countercyclical characteristic of traditional community currencies, increasing currency stability along time.

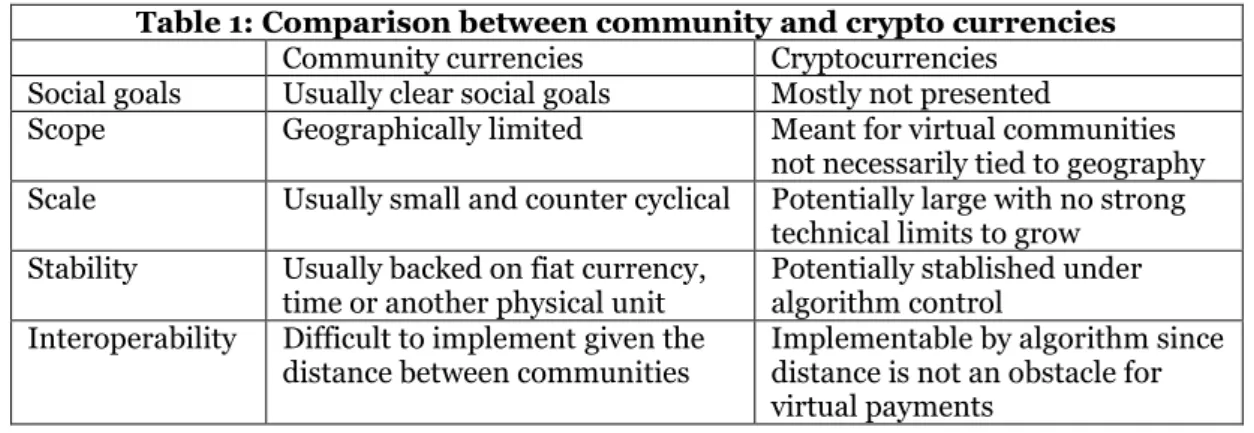

Table 1: Comparison between community and crypto currencies

Community currencies Cryptocurrencies Social goals Usually clear social goals Mostly not presented

Scope Geographically limited Meant for virtual communities not necessarily tied to geography Scale Usually small and counter cyclical Potentially large with no strong

technical limits to grow Stability Usually backed on fiat currency,

time or another physical unit Potentially stablished under algorithm control Interoperability Difficult to implement given the

distance between communities Implementable by algorithm since distance is not an obstacle for virtual payments

As it summarized in table 1, traditional community currencies and cryptocurrencies are usually very different in their basic premises, then it is a matter of investigate the true nature of the social cryptocurrencies as hybrid projects originated from two very different approaches for developing a currency.

Sociomateriality and social cryptocurrencies

Sociomateriality promises to better capture the richness and emergent organizing process where the social and the material cannot be separated. Emerging from a so-called materiality turn in the nineties, sociomateriality grew in importance for researchers questioning digitalization of societies and organizations, disembodiment of agency and the increasing collective activities supported by mobile technologies (Pozzebon et al., 2017). In management and organization studies, ‘sociomaterial’ scholars have attempted to overcome the dichotomy between social and material worlds by concentrating on the practices within organizations, practices that are constituted by, but also produce, material and social dynamics.

According to Orlikowski (2007, p. 1435), we have ‘overlooked the ways in which organizing is bound up with the material forms and spaces through which humans act and interact’. Seminal influences might be found among writings of Dale (2005), Latour (2007), Leonardi (2013) and Barad (2013), whose contributions have provided some of the keywords found in the sociomaterial vocabulary: material, materiality, devices, apparatus, intra-action, affordance, entanglement, performativity.

While previous research on sociomateriality focus on analyzing the relationship between human and technology (Cecez-Kecmanovic, et al, 2014; Orlikowski and Scott, 2014; Leonardi, 2013), in our research we consider the relations between the technology and the organization, since we want to investigate the relations between the cryptocurrency’s architecture and governance. Despite different from each other, the two types of interactions – human-technology and organization-technology - can be considered coherent with the theoretical perspectives that supports sociomateriality since analysis occurs where individual behavior determines and is determined by a social context. Payments only occur if payers and recipients adopt the payment system and payment system is only adopted if the necessary level of trust is provided to payers and recipients. As posed by Rice & Leonardi (2014), the materiality of a technology provides capabilities to do some things while makes others difficult, this way shaping people’s decision to adopt and use it, or not.

In the particular case of payment systems, one important element to trigger adoption by users is the reputation of the currency issuer. While technology is responsible for making the payment infrastructure cheap, easy to use and reliable, all important vectors for adoption, reputation of issuer is part of a social construction that is also reflected in the payment adoption. On the other way around, a very trustful payment infrastructure can reinforce the issuer reputation, attracting more adoption to the platform.

In this analysis, it is understood that the technology design incorporates features of organizational structures, such as: hierarchical structure, organizational knowledge and operational procedures in technology (DeSanctis and Poole, 1994). Thus, new technologies can allow significant changes in organizations, this creates a reciprocal adaptive relationship and can generate expected (e.g., more safety) and not expected (ex: interchange of cryptocurrencies) outcomes. In this case, technology- enables change in organization structure and "institutions imposes restrictions by defining legal, moral and cultural boundaries, distinguishing between acceptable and unacceptable behavior" (Scott, 2013, p. 58). That forces institutional mechanisms operate at several levels (Scott, 2013, 56), creating interdependence, and mimetic forces (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983) to operate in the organizational field, which reinforces the need to consider analysis at the organizational level.

Payment systems are essentially sociomaterial. Reflecting on the plastic credit card, Visa’s founder Dee Hock notes that the fact “it took the form of a piece of plastic was nothing but an accident of time and circumstance” (Deville, 2013:87), meaning that the social (and economical) relations around payment transactions are more critical than the material instrument that make it possible. Credit cards as well as bill notes or even bitcoins are only considered as payment instruments because they are supported by a complex network of agents that authorize and validate each transaction done with any of them. These agents take form of a combination of technological infrastructure and rules created to establish a trustful environment for payers and recipients to engage in a payment transaction. While technology and rules might be considered as material elements of the payment ecosystem, they only make sense when provide the necessary conditions for influencing the real decision makers (payer and recipient) towards adoption.

Conceptual framework

The theoretical challenge of this study is to provide a robust conceptual framework that connects the main challenges posed by the new cryptocurrencies (scale, scope, stability and interoperability) to the new governance models that can emerge in the realm of social cryptocurrencies.

Thus, knowing the architecture of cryptocurrencies and the governance structure for community currencies we have a more detailed understanding of social cryptocurrency platforms, making room for deeper analysis of such particular payment projects. Next, we first present aspects of the community currencies governance, and then describe elements from blockchain architecture considered in our conceptual framework, both essential to build the social cryptocurrency concept.

Community Currencies Governance

Governance broadly refers to who decides what in any platform’s ecosystem (Tiwana, 2014). Since there are always a number of different stakeholders involved in a currency project, a governance structure

characterizes what is their participation in the decision-making process (CCIA, 2015). Although there are other levels of decision (e.g., strategic, operational, etc.), one way to understand the governance of a community currency is to evaluate how centralized or shared is the decision making process about rules for issuance in a particular project, given that this is central to the process of manage a currency. The community currency governance may be considered as “shared” if decisions about issuance rules are taken from a bottom-up process inside a grassroots or cooperative organization. On the other hand, this governance may be considered as “central” if issuance decisions are top down and taken by some sort of local authority (Diniz et al, 2016b).

Governance refers to the power of decision on what a platform effectively does, and who will approve its future directions. The degree of openness in a platform is one of the keys issues about governance (Staykova & Damsgaard, 2015; Ondrus et al, 2015). If the governance over a platform is shared among multiple owners or it is based on open standards, it represents a shared rather than proprietary platform (Tiwana, 2014).

A currency organizational structure should reflect values that the currency represents, what requires a governance structure that brings stakeholders together to participate of the decision-making process, the implementation of solutions to common problems and goals (CCIA, 2015). Among the most common decisions related to the community currency that are influenced by the governance structure are objectives, issuance, backing, technological architecture, etc.

In previous studies, some analysed social cryptocurrencies work in a centralized model of governance and others implement a shared model. Cadastral, from Ghana, uses blockchain to guarantee transparency for the parts involved, and is a case of centralized model managed and full controlled by a company which decides about its implementation, distribution and rules of participation. In contrast, the Spanish Ecosol organizes people and merchants through cooperatives that take the decisions about the currency (Diniz et al., 2016b).

Governance will have particular interest in this paper’s analysis. If it is clear that adopting a distributed ledger not necessarily leads to a cooperative governance, with a centralized payment architecture (everything we knew before blockchain) it is very difficult to establish a decentralized governance. However, if it is perfectly possible to stablish centralized governance of a distributed currency, we want to know the limits of doing some sort of decentralized governance without a decentralized infrastructure. In other words, we want to understand how the distributed structure of a blockchain platform relates with a decentralized governance structure of the institutions controlling the platform, and vice versa.

When talking about community currencies, solidarity economy principles are very important to be considered. However, there is in the literature a certain difficulty in conceptualizing the solidarity economy; some authors combine their concept with that of self-management, cooperativism, informal economy or popular economy, which are possible ways of organizing the solidarity economy (Caminha & Figueiredo, 2011).

On the other hand, other studies on the social currencies have shown that when they move to a higher scale, there is more risk of centralization in the governance process, limiting the possibilities of keeping the more open, democratic and shared model of governance that characterizes most traditional community currencies (Siqueira et al., 2017; Diniz et al. 2014).

To summarize, we can find many different models of governance for social cryptocurrencies but they can be considered in two different categories: centralized and shared. While the centralized ones tend to be powered by governments and for-profit organizations, the shared ones tend to be controlled by NGOs and cooperative organizations (Diniz et al., 2016b).

Cryptocurrencies architecture

Blockchain is, in fact, a protocol related to several different types of DLT - Distributed Ledger Technologies (Narayanan et al. 2016). A full discussion of the blockchain protocol and the many aspects of any DLT is out of the range of this paper. Nevertheless, for the purpose of the study about social cryptocurrencies, we focus on one critical aspect of any technological blockchain implementation: the definition of "how distributed" is the network that uses the protocol. Current blockchain systems can be roughly categorized into three types, depending on the definition on how distributed the implementation is: public blockchain, private blockchain and permissioned blockchain (Peters & Panayi, 2016; Walport, 2016).

At one extreme, there is the case of a fully distributed architecture network, open to any participant. In this case, all nodes can read blockchain data, submit transactions and validate transactions within the network. An example is Bitcoin Green, a public blockchain in which anyone can enter the network and validate the transactions that take place between its agents.

At the other extreme, even a distributed network can be designed based in a very centralized control, managed by "coordinators". In this case, only predefined nodes can read blockchain data, submit transactions and validate transactions. Liverpool Local Pound is a social cryptocurrency that adopt this architecture, also known as private blockchain.

Between these two extremes, there are other categories with different levels of decentralization. In that cases, only predefined nodes can validate transactions but all nodes may read blockchain data and submit transactions. Cadastrals is a social cryptocurrency based on this permissioned type of blockchain.

Considering the three dimensions of the architecture – public, private and permissioned – and the two general forms the governance – centralized and shared – we define the conceptual framework used in this paper. Once we have classified currencies using these dimensions, it is possible to analyze the categories of social cryptocurrencies in face the issues proposed on Table 1: their social goals, scope, scale, stability and interoperability.

Research approach

To develop the empirical part of this study, we first selected a group of currency projects that fit in the definition of social cryptocurrencies and then analysed them following the proposed conceptual approach. Next we discuss in detail the process of cases selection and the analytical method used to understand the currency projects.

Selection of Cases

A challenging step in this research was the selection of cases that would be correctly considered as a social cryptocurrency. This required, initially, the adoption of a selection criteria. The first part of the selection criterion refers to the term "cryptocurrency". For this, were considered as cryptocurrency the currencies that have distributed systems of records of transaction in blocks (blockchain) as its platform. It is important to note that there are digital tokens that are issued in blockchain but do not are considered currency, such as Ethereum, which is presented as a platform. Such tokens will not be considered in the survey.

The second part of the selection criterion concerns the term "social". As exposed earlier in this paper, we will consider social cryptocurrency only the ones which go beyond the primary economic goals and have clear social or environmental statement as a goal of the currency project.

With those criteria defined, we start the process of identifying potential use-cases to include in our sample for analysis. We did that in three steps. The first step was to go through the list of cryptocurrencies available on the coinmarketcap.com website and, secondarily, articles available on the coindesk.com site. This allowed us to start with a list of more than 1,000 different currencies.

Within this vast group, we access their website projects and looked for indications of matching with the social cryptocurrency criteria. In a second step, we reduced the universe of analysis to 39 cryptocurrencies with a clear social or environmental declared goal.

Finally, in the third step, we filter those cases trough a deeper analysis of each of those projects, scouring their websites and also their announcements, whitepapers and published news. That allowed a deeper understanding of each project, ensuring a better accuracy in the selection of cases adhering to the selection criterion. For 21 social cryptocurrencies we did not found information on either the architecture, governance, social goals, scope, scale, stability or interoperability of such projects. Then those were also excluded from this study because we could not say much about them in terms of the dimensions we are interested in investigate.

As a result, we obtained a list of 18 social cryptocurrencies that we could access all the required information to be used in this study. Due to the fast emergence of new crypto-coins, it was necessary to establish a cut-off date in which, as from that date, new currencies arising in coinmarketcap listings were no longer included in the study. Therefore, as of 03/25/2018, the inclusion of new currencies in

the survey was interrupted and, from that date on, only information about the currencies already selected was further collected.

Analysis of selected social currencies

In order to achieve the objectives of this research, secondary data was collected and analysed, including documents and websites analysis from organizations and their digital social currencies, in a similar way that was done in other research projects (Eschenfelder et al., 1997; Karkin and Janssen, 2014; Matheus et al., 2016; Diniz, Siqueira and Heck, 2016b).

To reduce risks of using not reliable and even inconsistent secondary data, one of the strategies adopted was to limit significantly the accepted sources of data. Basically, only the following online sources were considered:

Official sites of the social cryptocurrencies projects studied

Information available on coinmarketcap.com - an important source for obtaining a first list of crypto-coins and for obtaining some quantitative data

Announcement items published in the forum bitcointalk.org - the main community used for announcements of projects and discussions on crypto tokens

Coindesk.com site articles, one of the leading aggregators of news and analysis of the crypto market

Due to the great heterogeneity of available data and due to the constant new findings through this research, the collection, analysis and interpretation process was naturally nonlinear, often requiring new cycles of data collection for the same group of social cryptocurrencies.

In addition, after completing the selection of cases to be contemplated in the study, a new round of data collection was performed through questionnaires sent directly to the organizations responsible for each project. This additional data collection allowed us to refine and validate our understanding of the social cryptocurrencies presented in this study.

We first look for information about the governance and architecture of all the selected social currencies and then tried to establish comparative labels for the i) level of adoption (scale); ii) intended territory for operation (scope); iii) existence of any type of parity or backing systems for the currencies (stability); and lastly iv) declared ability of interoperability of the currency with others from the same kind. In adoption, we segregated currencies that are already being used and accepted by online and physical merchants (high adoption), currencies that are used only in very specific online websites (medium adoption) and currencies that even though are operational and transacted between users, does not are clearly being accept as a payment method yet (low adoption). In scope, we classified currencies not only as local (as it is used to be on traditional social currencies), but almost half of them as global. The price stability was segregated between currencies that are stable trough a backing mechanism of their maintainers and currencies that are traded at market prices.

As we could not find any currency that is interoperable with others, we discharged this element of analysis. We searched to potential interoperable currencies in the Bancor Network website (www.bancor.network) because the Bancor Protocol declared intention is to promote interoperability among social currencies (Hertzog et al., 2017). However, all the currency projects listed in this network were either too recent (just a couple of months old) or of little significance (just dozens of users). Despite the impossibility of using the interoperability in this study, we firmly believe that this issue will become more important in the near future for understanding social cryptocurrencies.

Findings and Discussion

Firstly, we organize social cryptocurrencies according to their identified blockchain architecture and institutional governance, as it was established earlier in the literature review. We segregated the social cryptocurrencies in three different kinds of blockchain implementation: public blockchain, when the transaction validation nodes can be set by anyone; permissioned blockchain, when only a small number of registered nodes can be set to validate transactions; and private blockchain, when only the currency maintainer validates transactions.

Architecture

Governance Public Permissioned Private

Shared Artbyte; Auroracoin; BitcoinGreen; Carboncoin; Dinastycoin; Musicoin; PinkCoin; Polis

Faircoin; Solarcoin; Moeda; Monedapar

Central Cadastrals East London Pound;

Haifa Shekel; Liverpool Pound; Plastic Bank; Tel-Aviv Shekel

Then we classified currencies according to the governance dimension. We segregated the cryptocurrencies governance by analysing the maintainers of each project. The projects whose maintainers where mostly volunteers and/or non-profit organizations was classified as having a shared governance, while projects created by governments or for-profit organizations was classified as having a central governance. Once we had all the social cryptocurrencies classified in terms of their architecture and governance, we group them in five categories: Shared/Public; Shared/Permissioned; Central/Permissioned; and Central/Private. No currency was found in the Central/Public ou Shared/Private classification. The resulting combined classification of governance and architecture is presented in Table 2.

Looking at the resulting categories, it is noticeable the concentration of currencies in only two groups: Shared/Public and Central/Private. This is very expected since those are the projects that keep better alignment of governance and architecture. This means that the sociomaterial explanation did make sense for social cryptocurrencies. The more open governance style of some currencies led them to choose the more open architecture while the ones with more closed governance adopted the more closed architecture. The same way, the void at the Central/Public and at the Shared/Private categories can be understood as the most improbable combinations of governance and architecture.

Secondly, we analysed the five categories found by combining governance and architecture with the other four characteristics we define as important to evaluate a social community currency: goal, scope, scale and stability. As we mention earlier, the interoperability was not considered for this analysis since no currency have presented any intention to interoperate with others. Table 3 presents the classification from the data gathering and analysis of the 18 selected social cryptocurrencies grouped in the identified categories and classified in the four studied dimensions.

Table 3. Categories of Social Cryptocurrencies

Cryptocurrency Governance/Architecture Goal Scope Scale Stability

East London Pound central/private Social Local High Backed Haifa Shekel central/private Social Local High Backed Liverpool Pound central/private Social Local High Backed Tel-Aviv Shekel central/private Social Local High Backed Plastic Bank central/private Hybrid Local High Backed Artbyte shared/public Social Global Medium Market Polis shared/public Social Global Low Market Bitcoin Green shared/public Environmental Global Low Market Carboncoin shared/public Environmental Global Low Market Musicoin shared/public Social Global Medium Market PinkCoin shared/public Social Global Medium Market Auroracoin shared/public Social Local High Market Dinastycoin shared/public Social Local Medium Market Faircoin shared/permissioned Social Global Medium Backed

Moeda shared/permissioned Social Local Low Backed Monedapar shared/permissioned Social Local Medium Backed Solarcoin shared/permissioned Environmental Global Low Backed Cadastral central/permissioned Social Local Low Market

Central/Private currencies is the most uniform category since they have very similar characteristics with respect to all analysed aspects. The only exception in this category is Plastic Bank classified as having “hybrid” goal, since its maintainers describe the project as having both objectives: social and environmental. All of them are focused on a local defined territory and backed what make them more stable. It is probably the combination of those characteristics (scope and stability) that make them all with high levels of adoption and let us to foresee that those type of social cryptocurrencies have higher probability to keep themselves operating for longer in a market where many projects suffer from being ephemeral.

The category with the larger number of currencies is the Shared/Public, another finding that could be expected. Since many community currencies have some type of shared governance, this might be an influential element when choosing the architecture mode. On the other hand, all of them have price regulated by the market, what means they have no parity system associated, in contradiction with most traditional community currency cases. It is a matter of further investigation to understand if those currencies were originally created in blockchain or are a migration from other types of platforms, since they keep some traditional characteristics from the old community currencies but also incorporate typical elements of the cryptocurrencies environment. Although most of them intend to be global (Auroracoin was considered local but it covers the whole small territory of Iceland) their level of adoption tend to be low to medium. The lack of focus on a territory (again Auroracoin in Iceland is the exception) might harm the future perspective for those social cryptocurrencies, especially when confronted with competition with other currencies also acting globally.

The Shared/Permissioned category is characterized by projects that users need to enroll and be approved before they can take part of it. The Argentinean MonedaPar, for example, is a marketplace managed by an NGO where merchants and prosumers (mix of producers and consumers) exchange goods and services in a sort of barter system. The Spanish FairCoin and the Brazilian Moeda are cooperative type of organizations that users must associate to make transactions with other partner associates. All these three projects are backed by fiat money in their regions as a way to guarantee price stability. While MonedaPar and Moeda are very focused on solving social problems in their respective countries, FairCoin is maintained by FairCoop, an open cooperative system organized world-wide through the Internet, although originated in Spain. To keep in line with the international spirit of its mother institution, FairCoin was conceived to be used globally.

SolarCoin differs from the other three in this category. Maintained by an NGO, it was created to connect individuals living in homes with solar panels on their roof or commercial solar electricity producers. SolarCoin is backed on energy (MegaWatthour) and every affiliate receives solarcoins proportional to their solar energy production capacity, allegedly for their contribution to environment. The receivers can make exchange with others in the SolarCoin network or spend them globally in the cryptocurrency market, in exchange with Bitcoins, for example. The medium to low level of adoption of the social cryptocurrencies in this category might be related to the association demands of the organizations controlling them.

Cadastral, from Ghana, is the only currency of the studied sample classified in the Central/Permissioned category. This currency is controlled by BitLand, a technology organization that provides the whole infrastructure for digital landing registry. Cadastral is the social cryptocurrency issued and sold to individuals that will be able to use them to invest in the local economy. As the only case in this category, not much can be told about the category itself that is not different of the single case on it.

The classification in the categories drawn from the sociomaterial combination of governance and architecture proved to be useful for a more abstract understanding of the emergent phenomenon of social cryptocurrencies. By analyzing the categories, we could understand how currencies on each of them are facing the challenges of adopting a blockchain platform technology.

The main conclusions from this analysis are, first, the fact that there is a clear alignment between currencies type of governance and architecture platform. This is a sign that the most shared is the governance, the bigger the probability of adopting an open blockchain architecture, and vice versa. Second, currencies within one single category share ways to establish price stability, with the more closed choosing a more stable environment while the more open trusting more in the market to establish their prices. Third, social currencies focused on local issues tend to have a higher level of adoption. This is probably related to the fact that local competition between currencies is low or nonexistent, at the same time that access to potential users in the network is easier. However, when the currency intends to be global, competition within is greater, and reaching the potential stakeholders is more difficult.

Final Comments

We proposed an investigation on the emergent phenomenon of cryptocurrencies by studying those with explicit social or environmental goals, that we called social cryptocurrencies. To perform this study, we adopt a socialmaterial approach based on a combination of two elements identified with the social and the material aspects of a digital platform, respectively, governance and architecture. From the combination of these elements, we define a set of categories used to classify a selected sample of 18 social cryptocurrencies. Within each category, we then discussed topics that we considered critical for the management of social cryptocurrencies – scale, scope, stability and interoperability – since they seemed to be taken differently in each of the distinct universes that originated the concept of social cryptocurrencies: the community currencies and the cryptocurrencies.

From the analysis with the proposed framework, we found that the sociomaterial approach provides good foundations for explaining the characteristics of social cryptocurrencies. The entanglement between governance and architecture is clearly noticeable by the analysis of the studied cases. It seems to be natural that, for social cryptocurrencies, the more open the governance structure, the more probable to adopt a more open platform architecture. We also used the categories to explain the great deal of uniformity among the investigated currency projects, concerning the critical issues taken from the literature. This suggest that the conceptual approach is a good starting point for analysis of this kind, although it still has to be proved with a larger sample of social community currencies, what surely is going to be made in future studies.

Thus, the first contribution of this paper is to present the relevance of the sociomateriality to understand the universe of social community currencies. This is a theoretical contribution to the IS field, as well as to the studies of community currencies, since we are navigating in a multidisciplinary subject by nature. Another contribution is the understanding of the main issues of blockchain technologies to social organizations, what is also useful for the practitioners in the field of community currencies management that are still considering the adoption of this technology model to improve their social goals and governance structure.

As limitations for this study, the first one is the small number of cryptocurrencies that could be accessed to be part of the sample. This is a point that could stimulate researchers in the near future to revisit this study, since the number of new social currencies is continuously growing. A second obvious limitation is the study based on secondary data, and in particular considering that the demanded data which is not always easy to find. Although it has a role for such an exploratory investigation, further investigation approaching the managers or even the users of the currencies is mandatory. As we are talking about currencies spread out all over the world, this is not an easy task. We sent short questionnaires to all currencies of our sample but the answer was very limited, although it helped of clarifying the details about some of them.

Social finance organizations embracing cryptocurrencies technology is a new phenomenon that is in its first infancy, despite it is expected to grow significantly in the coming years. As this type of organization is seeking to improve their scalability without risking their social mission, the adoption of decentralized technology platforms is still a field for further investigation. Talking more specifically the organizations that launch and support social cryptocurrencies, they tend to be different from the organizations that sustain the traditional social currencies, narrowly geographically limited, counter cyclical and without exchange with other community currencies. Thus, they have to pay attention on the specific characteristics of this new technological environment and its potential impacts for their main social goals. Governance and architecture relations in such organizations are a matter of continuous investigation, considering that blockchain-based decentralised applications may have the potential to transform models of governance (Reijers & Coeckelbergh, 2016).

References

Alcantara, C., & Dick, C. 2017. Decolonization in a Digital Age: Cryptocurrencies and Indigenous Self-Determination in Canada. Canadian Journal of Law & Society/La Revue Canadienne Droit et Société, 32(1), 19-35.

Ali, R., Barrdear, J., Clews, R., and Southgate, J. 2014. “Innovations in payment technologies and the emergence of digital currencies”, Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin 2014 Q3.

Ametrano, F. M. 2016. “Hayek Money: The Cryptocurrency Price Stability Solution (Aug 13)”, available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2425270

Barad, K. 2013. “Ma(r)king time: Material entanglements and re-memberings: Cutting together-apart”. In Carlile, P. R., Nicolini, D., Langley, A., & Tsoukas, H. (Eds.), How Matter Matters: Objects, Artifacts, and Materiality in Organization Studies, Oxford University Press, pp. 16-31.

Bates, L. C. 2016. “Bitland White Paper”. At: www.academia.edu/23706604/Bitland_White_Paper Blanc, J. 2011. “Classifying "CCs": Community, complementary and local currencies' types and

generations”, International Journal of Community Currency Research p.4-10.

Burrell, J. (2016). Material ecosystems: Theorizing (digital) technologies in socioeconomic development. Information Technologies & International Development, 12(1), pp-1.

Cassoni, A., and Ramada, C. (2013). Digital money and its impact on local economic variables: The case of Uruguay. Document of Investigation, (92).

CCIA. 2015. “People Powered Money – Designing, developing and delivering community currencies. Community Currencies in Action”, New Economics Foundation, London.

Cecez-Kecmanovic, D., Galliers, R. D., Henfridsson, O., Newell, S. 2014. “The sociomateriality of information systems: current status, future directions”. MIS Quarterly Vol. 38 No. 3, pp. 809-830. Dale, K. 2005. “Building a social materiality: Spatial and embodied politics in organizational control”,

Organization, 12(5), 649-678.

DeSanctis, G., & Poole, M. S. 1994. “Capturing the complexity in advanced technology use: Adaptive structuration theory”. Organization Science, 5(2), 121–147.

Deville, J. (2013). Paying with plastic. Accumulation: The Material Politics of Plastic. London: Routledge. In Hawkins, G., Gabrys, J. and Michael, M., Accumulation: The Material Politics of Plastic, London: Routledge. 87-103.

DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. W. 1983. “The iron cage revisited: Collective rationality and institutional isomorphism in organizational fields”. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147-160.

Diniz, E. H., Alves, M. A., Cernev, A. K., and Nascimento, E. 2014. “Digital social money implementation by grassroots organizations: combining bottom-up and top-down strategies for social innovations”, available at SSRN: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2924690.

Diniz, E. H., Cernev, A. K., and Nascimento, E. 2016a. “Mobile social money: an exploratory study of the views of managers of community banks”. Revista de Administração (51 - 3), pp. 299-309. Diniz, E. H., Siqueira, E. S., & van Heck, E. 2016b. “Taxonomy for Understanding Digital Community

Currencies: Digital Payment Platforms and Virtual Community Feelings”. GlobDev 2016. Paper 10. Eschenfelder, K., J. Baechboard, C. Mcclure and S. Wyman. 1997. Assessing U.S. federal government

websites. Government Information Quarterly, v. 14, n.2.

Gartner. 2013. “Hype Cycle for the Future of Money”, ID: G00252277. Published in 19 July 2013 Gartner. 2017. “Hype Cycle for Blockchain Business.”, ID: G00332628, published in 10 August 2017. Gómez, G. M., and Dini, P. 2016. “Making sense of a crank case: monetary diversity in Argentina (1999–

2003)”, Cambridge Journal of Economics (40) pp. 1421–143.

Hertzog, E & Benartzi, G & Benartzi, G 2017. “Bancor protocol: continuous liquidity for cryptographic tokens through their smart contracts”. White Paper. At: https://bravenewcoin.com/assets/ Whitepapers/Bancor-Protocol-Whitepaper-en.pdf

Jabbar, K., and Bjørn, P. 2017, May. “Growing the Blockchain Information Infrastructure”, In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 6487-6498, ACM.

Joachain, H. and Klopfert, F. 2012. “Emerging trend of complementary currencies systems as policy instruments for environmental purposes: changes ahead?”, International Journal of Community Currency Research (16) pp. 156-168

Josavac, M. 2017. “The Bright and the Dark Side of Virtual Currencies”, Recent Development in Regulatory Framework. International Journal of Community Currency Research, Vol 21 (Summer) pp. 1-18

Karkin, N., Janssen, M. 2014. “Evaluating websites from a public value perspective: A review of Turkish local government websites”, International Journal of Information Management (v.34, n.5, June). Latour, B. 2007. “Can we get our materialism back, please?”, Isis, 98(1), 138-142

Leonardi, P. M. 2013. “Theoretical foundations for the study of sociomateriality”, Information and Organization (23:2), pp. 59-76.

Lucarelli, S., Sachy, M., Brekke, K. J., Bria, F., Giuliani, A., Gentilucci, E., and Idir, G. 2014. “D3. 4 Field Research and User Requirements Digital social currency pilots”, at: https://dcentproject.eu/wp- content/uploads/2014/06/D3.4-Field-Research-and-User-Requirements-Digital-social-currency-pilots_new.pdf.

Lund, A., and Venäläinen, J. 2016. Monetary materialities of peer-produced knowledge: the case of Wikipedia and its tensions with paid labour. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique. Open Access Journal for a Global Sustainable Information Society (14:1), pp. 78-98.

Marconatto, D., Cruz, L. B., and Pedrozo, E. A. (2016). “Going beyond microfinance fuzziness”, Journal of Cleaner Production (115), pp. 5-22.

Matheus, R., Rodrigues, D. A., Vaz, J. C., and Jayo, M. 2016. “Analysis of the openness level of governmental data about the brazilian motor vehicle traffic”. Revista Eletrônica de Sistemas de Informação (15:2), pp. 1-19.

Molnar, S. 2011. “Time is of the Essence: The Challenges and Achievements of a Swedish Time Banking Initiative”, International Journal of Community Currency Research (15), pp. 13-22.

Nakamoto, S. 2008. “Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system”. Available at: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf.

Narayanan, A.; Bonneau, J.; Felten, E.; Miller, A. & Goldfeder, S. 2016. Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency Technologies: a comprehensive introduction. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016 .336 p. Nascimento, E. P. C. C. D. 2015. “Moedas sociais digitais: estudo de caso de duas experiências em bancos

comunitários”. Master's Dissertation. Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo. FGV. 129 p.

Orlikowski, W. J. 2007. “Sociomaterial practices: Exploring technology at work”. Organization Studies, 28(9), 1435-1448.

Peters, G. W., and Panayi, E. 2016. "Understanding Modern Banking Ledgers through Blockchain Technologies: Future of Transaction Processing and Smart Contracts on the Internet of Money," in Banking Beyond Banks and Money, P. Tasca, T. Aste, L. Pelizzon, and N. Perony (eds.), Heidelberg et al.: Springer International Publishing, pp. 239–278.

Place, C., and Bindewald, L. 2013. “Validating and Improving the Impact of Complementary Currency Systems: impact assessment frameworks for sustainable development”, 2nd International Conference on Complementary and Community Currencies Systems, The Hague. June.

Pozzebon, M., Diniz, E. H., Mitev, N., Vaujany, F. X. D., CUNHA, M. P. E., & Leca, B. (2017). Joining the sociomaterial debate. Revista de Administração de Empresas, 57(6), 536-541.

Primavera, H. 2004. “The power of facts: Lessons from complementary currencies in Argentina”, European Conference on Community Currencies Bad Honnef, July 18-22nd.

Reijers, W., and Coeckelbergh, M. 2016. “The Blockchain as a Narrative Technology: Investigating the Social Ontology and Normative Configurations of Cryptocurrencies”, Philosophy & Technology, pp. 1-28.

Rice, R. E., & Leonardi, P. M. 2014. “Information and communication technologies in organizations.” The SAGE handbook of organizational communication: Advances in theory, research, and methods, 425-448.

Schroeder, R. F. H. 2013. “The Financing of Complementary Currencies: Risks and Chances on the Path toward Sustainable Regional Economies”, The “2” International Conference on Complementary Currency Systems (CCS) 19-23 June.

Schweizer, A., Schlatt, V., Urbach, N., & Fridgen, G. (2017). Unchaining Social Businesses–Blockchain as the Basic Technology of a Crowdlending Platform.

Scott, B. 2016. “How can cryptocurrency and blockchain technology play a role in building social and solidarity finance?” (No. 2016-1). UNRISD Working Paper.

Scott, S. V., & Orlikowski, W. 2014. “Entanglements in Practice: Performing Anonymity Through Social Media”. Management Information Systems Quarterly, 38(3), 873-893.

Scott, W. R. 2013. “Institutions and Organizations: Ideas, Interests, and Identities”. SAGE Publications. Ed.4, 360p.

Seyfang, G. 2001. “Community currencies: small change for a green economy”. Environment and planning A (33:6), pp. 975-996.

Seyfang, G., & Longhurst, N. 2016. What influences the diffusion of grassroots innovations for sustainability? Investigating community currency niches. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 28(1), 1-23.

Seyfang, G., and Longhurst, N. 2013. “Desperately seeking niches: Grassroots innovations and niche development in the community currency field”. Global Environmental Change, (23:5), pp. 881-891.

Siqueira, É. S., Diniz, E. H., Pozzebon, M. and Gomes, E. 2017. “A digital community bank mapping negotiation mechanisms in its consolidation as an alternative to commercial banks”. IV International Conference on Social and Complementary Currencies: Money, Consciousness and Values for Social Change. Barcelona.

Stodder, J. 2009. “Complementary credit networks and macroeconomic stability: Switzerland's Wirtschaftsring”. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, (72:1), pp. 79-95.

Tiwana, A. 2014. “Platform ecosystems: aligning architecture, governance, and strategy”. Elsevier. 305p.

Walport, M. 2016. “Distributed ledger technology: Beyond blockchain”. UK Government Office for Science.