339

A new species of

Rineloricaria

(Siluriformes: Loricariidae: Loricariinae)

from rio Daraá, rio Negro basin, Amazon, Brazil

Lúcia H. Rapp Py-Daniel

1and Ilana Fichberg

2Rineloricaria daraha, new species, is described from the rio Daraá, tributary of rio Negro, northwestern Amazonas State, Brazil. The new species is diagnosed by having seven branched pectoral-fin rays, finger-like papillae on the lower lip, a large multi-angular preanal plate, and at least four quadrangular plates of variable size surrounding the preanal plate. The new species is known only from rio Daraá and its waterfalls.

Rineloricaria daraha, espécie nova, é descrita do rio Daraá, um afluente do rio Negro, noroeste do Estado do Amazonas, Brasil. A nova espécie pode ser diagnosticada por apresentar sete raios ramificados na nadadeira peitoral, lábios inferiores com papilas digitiformes, uma grande placa pré-anal multi-angular e, pelo menos, quatro placas de diferentes tamanhos circundando a placa pré-anal. A nova espécie é conhecida apenas do rio Daraá e suas cachoeiras.

Key words: Armored catfish, Freshwater fish, Taxonomy, Neotropical fish.

1Programa de Coleções e Acervos Científicos, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisa da Amazônia (INPA), Av. André Araújo, 2936, Petrópolis,

69011-970 Manaus, AM, Brazil. rapp@inpa.gov.br

2 Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo (MZUSP), Av. Nazaré, 481, Ipiranga, 04263-000 São Paulo, SP, Brazil. ilanafic@ib.usp.br

Introduction

Rineloricaria Bleeker, 1862, is the most species-rich ge-nus of the Loricariinae with approximately 60 species (Rodriguez & Reis, 2008; Ghazzi, 2008), and widely distributed from Panama in Central America to northern Argentina, on both slopes of the Andes (Reis & Cardoso, 2001; Covain & Fisch-Muller, 2007). Rineloricaria has been diagnosed by a combination of characters, such as presence of a small post-orbital notch, surface of the inferior lip bearing short button-like papillae, each hemi-maxilla carrying up to 15 short mandibulary teeth, teeth strong and deeply forked, dark bands on the dorsal region of the body with the first one at the origin of dorsal fin, pectoral fin with one spine and six branched rays, a distinctly polygonal preanal plate usually surrounded by three to five other plates, and conspicuous sexual dimorphism in mature males, consisting of numerous developed odontodes along the sides of the head, on the pectoral-fin spine and predorsal area (Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1992: figs. 34-36). In males, the pectoral-fin spine is often thick, short, and curved when compared to females. Males of some species of Rineloricaria have well-developed odontodes all over the predorsal area.

The genus Hemiloricaria Bleeker, 1862 had been largely considered as a synonym of Rineloricaria until, Isbrücker

et al. (2001) resurrected the genus and created two others (Leliella and Fonchiiichthys) to accommodate some species previously included in Rineloricaria, based on differences on sexual dimorphism. Ferraris (2003) maintained Hemiloricaria as a synonym of Rineloricaria, but in 2007, he also resurrected the genus without comments, but did not consider Leliellaor Fonchiiichthys as valid. Covain & Fisch-Muller (2007) followed Ferraris (2003) and did not con-sider Hemiloricaria, Fonchiiichthys and Leliella as valid names.

Rodriguez & Reis (2008) partly accepted Isbrücker et al. (2001) phenetic proposition of spliting Rineloricaria and Hemiloricaria. Rodriguez & Reis, however, proposed that Hemiloricaria would comprise a wide distributed group of species (Amazon and non-Amazon species) whereas Rineloricaria would be restricted to species occurring in rio Paraná and its tributaries, and the coastal drainages from Uru-guay to northeastern Brazil.

Material and Methods

Measurements follow Boeseman (1976), Reis & Cardoso (2001) and Rodriguez & Miquelarena (2005). Straight-line dis-tances were measured with digital calipers. The term lateral abdominal plate follows Reis & Pereira (2000) terminology for what is sometimes called thoracic plates. Dorsal and pectoral spines refer to the first unbranched and thick ray of each fin. This term is preferred to “unbranched or simple ray” due to the presence of non-pungent spines on some loricariids that are homologous to the unbranched first dorsal and pectoral-fin ray in loricariines, and to avoid confusion with the unbranched last rays of all fins. Measurements in Table 1 are expressed as proportions of the Standard Length (SL), except for subunits of the head, which are expressed as proportions of Head Length (HL). Plate counts and nomenclature follow schemes of serial homology proposed by Schaefer (1997). Some paratypes were not measured due to reduced size or bad state of preservation.

SeveralRineloricaria species were not available for close examination and had, therefore, their morphological condi-tions determined from literature accounts. Institutional

ab-breviations are INPA (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazônia), MZUSP (Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo), NMW (Naturhistorisches Museum Wien), and MCZ (Museum of Comparative Zoology in Harvard).

Results

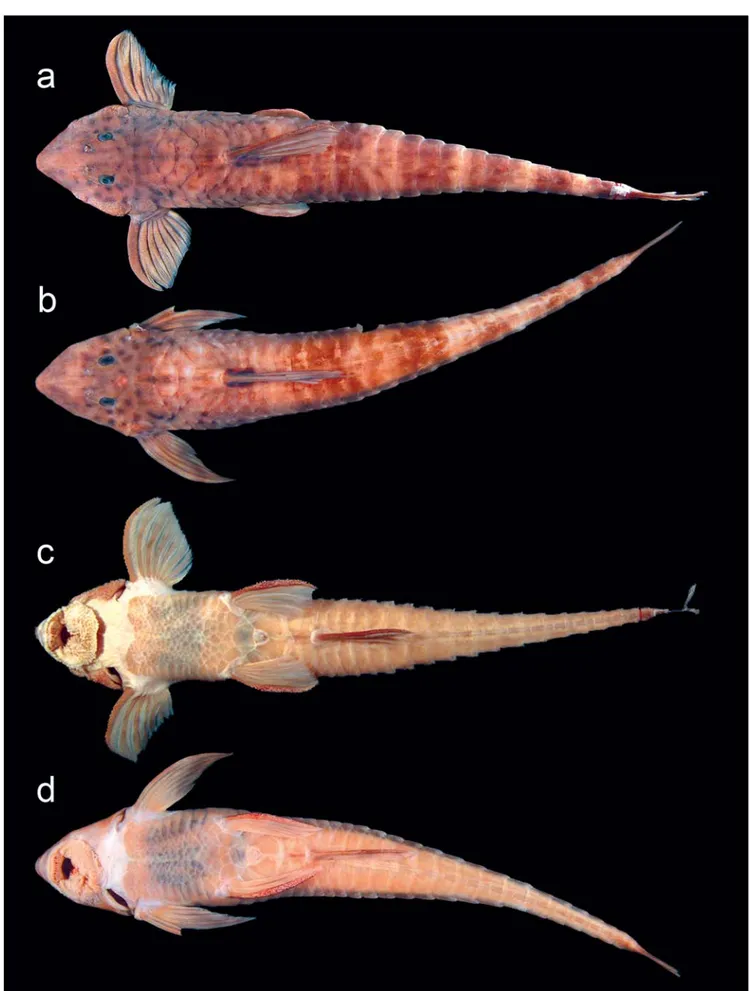

Rineloricaria daraha, new species Figs. 1-3

Holotype. INPA 28579, 200.9 mm SL (male), Brazil, Amazonas, rio Daraá, cachoeira do Aracu (00°25’00”S 064°46’59”W), 29 Nov 1991, R. Sotero & R. Ribeiro.

Paratypes. (20) Brazil, Amazonas, rio Daraá. INPA 6586, 4, 129.3-186.8 mm SL, same data as holotype. MZUSP 31396, 1 c&s, 127.5 mm SL, female, cachoeira do Aracu, 10 Feb 1980, M. Goulding. MZUSP 35094, 2, 40.7-46.6 mm SL, females, cachoeira do Aracu, 10 Nov 1980, M. Goulding. INPA 6587, 2, 57.7-65.9 mm SL, cachoeira do Pacu, 1 Dec 1991, L. Aquino. INPA 12045, 7, 63.0-117.4 mm SL, cachoeira do Pacu, 1 Dec 1991, L. Aquino. INPA 17939, 3, 41.3-74.5 mm SL, cachoeira do Aracu, 10 Nov 1980, M. Goulding, INPA 28780, 1, 75.0 mm SL, juvenile, rio Daraá, cachoeira do Panãpanã, 00°02’15.2”S 64°47’44”W, 4 Feb 2008, M. Rocha & V. Masson.

Diagnosis.Rineloricaria daraha is distinguished from all its congeners by having seven branched pectoral-fin rays (vs. six), long digitiform papillae on the ventral surface of the lower lip (vs. button-like papillae) and by the presence of a large and multi-angular preanal plate limited anteriorly by four or more variably sized plates much smaller than the preanal plate (vs. a quadrangular preanal plate surrounded by three to five polygonal plates slightly smaller than the preanal plate).

Description.Morphometric data in Table 1. Body elongated and depressed. Dorsal profile slightly convex from tip of snout to origin of dorsal fin. Body slender along its whole exten-sion, tapering softly towards base of caudal fin. Ventral pro-file straight from tip of snout to pelvic fin. Lateral propro-file from pelvic fin to caudal fin becomes more depressed towards cau-dal-fin base where body becomes more flattened. Greatest body depth at dorsal-fin base.

Head elongated and depressed. Snout long (53-59% of head length) and pointed with small naked area. Naked area not reaching most anterior pore of infraorbital sensory canal. Orbit small and round, with deep and short lanceolate postor-bital notch. Head variably keeled; when present, keel reduced to low ridge in front of eye.

Predorsal area not keeled, except by weak pair of carinae on last predorsal plate. Twenty seven lateral plates conspicu-ously carinated forming a keel. Two longitudinal and confluent keels meeting at 14th plate of median series. From this point

on, remaining thirteen carinated plates of both lateral series form single keel until base of caudal fin.

Mouth opening small and surrounded by short upper lip and well-developed lower lip. Margin of lip fringed with small filaments. Rictal region with well marked groove. Above groove, line of button-like papillae cover maxillary barbel. Papillae much longer at tip of maxillary barbel. Upper lip with few button-like papillae, lower lip surface covered (densely covered in some specimens) by long digitiform papillae, re-sembling short filaments. Digitiform papillae concentrated around mouth cavity. Small specimens (smaller than 50 mm SL) with round papillae on lip surface. Buccal papillae present behind dentaries; few buccal papillae on premaxillaries. Most of palate smooth, without papillae, except for straight line with three to five papillae, longitudinally oriented, situated at lateral tip of premaxillaries. Mandibular teeth short but ro-bust, deeply forked: seven to eight teeth on premaxillaries and five to seven on dentaries. Dentary teeth larger than those on premaxilla.

Dorsal fin I,7, anterior and long, running along 8 or 9 dor-sal plates; pectoral fin I,7 with spine almost straight on fe-males or non-reproductive fe-males, and thick and curved on mature or almost mature males. Pectoral fin reaching third plate of dorsal lateral series. Pelvic fin i,5 and anal fin i,5, well-developed. Pelvic fin reaching little beyond insertion of anal fin mostly in females; pelvic fin of males not reaching anal-fin insertion when adpressed. Pelvic unbranched ray thicker in mature males. Anal fin running along seven plates. Caudal fin

i,10,i, bilobed to slightly emarginated, with upper lobe little longer than lower lobe. Dorsalmost caudal-fin ray bearing long and thick filament.

Abdominal surface completely covered by unorganized small quadrangular plates in adults, except for naked gular area. Five or six large lateral abdominal plates. Strong gradi-ent of increasing plate size towards pelvic fin. Abdominal plates tightly packed and forming shield. Anterior borderline of this shield irregular, curved caudad in mid-line in some specimens. Preanal plate present, conspicuously larger than other plates and almost round in shape in some specimens. Preanal plate surrounded by at least four quadrangular plates of largely different sizes, with some much smaller than prea-nal plate itself. Abdomiprea-nal plating development following ontogenetic process with young specimens showing abdo-men largely naked, with few odontodes spread all over ab-dominal surface. Young adults (approximately 130 mm) with abdomen completely covered.

Color in alcohol. Light brown background densely covered with conspicuous black round spots on head; faded and ir-regularly shaped dark blotches on body. Most spots on head contain pores of cephalic sensory canal. Sphenotic and su-praoccipital bordered by soft black connective tissue in re-cently preserved specimens. Two conspicuous black spots just above naked area behind cleithrum, spots surrounding one or two exits of lateral sensory canal. Five wide dark trans-verse bands on body: first just behind dorsal-fin base, three bands along caudal peduncle and last one close to caudal-fin base. Bands faded in some specimens. Ventral surface uni-form. All fin rays irregularly stained of dark, forming large bands of just spots on fins. Interradial membranes hyaline. Dorsal, pectoral and caudal fins darkened at base.

Hol n range mean SD

Standard length (mm) 200.9 16 40.7-200.9

Percents of standard length

Head length 22.4 16 21.6-24.3 22.5 0.66

Predorsal length 33.6 16 31.1-34.4 33.4 0.93

Dorsal-spine length 16.7 16 15.5-20.0 18.5 1.53

Anal-spine length 13.2 16 12.6-18.8 16.4 1.69

Pectoral-spine length 12.8 16 12.8-19.1 17.5 1.83

Pelvic-spine length 12.2 16 12.2-17.4 15.6 1.26

Thoracic length 28.8 16 20.0-28.8 26.8 2.09

Abdominal length 13.9 16 11.6-14.5 13.0 0.71

Cleithral width 17.4 16 16.0-18.2 17.2 0.69

Body depth at dorsal-fin origin 9.7 16 8.6-11.1 9.5 0.74 Body width at anal-fin origin 12.7 16 8.2-13.2 11.1 1.44

Postanal length 62.2 16 53.4-63.7 58.3 3.42

Percents of head length

Head width 73.8 16 71.9-80.4 77.0 2.87

Snout length 59.0 16 53.3-59.9 57.4 1.74

Orbital diameter 13.7 16 13.7-17.5 15.9 1.29

Interorbital width 21.5 16 21.8-26.2 22.9 1.51

Head depth 38.0 16 33.7-90.6 59.8 24.7

Premaxillary ramus 7.3 16 6.1-11.2 9.1 1.69

Sex dimorphism. Mature males present the following fea-tures: large patch of thick enlarged odontodes on sides of the head; pectoral-fin spine thick and strongly curved; pectoral spine and rays heavily covered by enlarged series of odontodes; shorter snout and fins when compared to young

and females (Figs. 2 and 3). Dorsal, pectoral, pelvic and anal fins slightly longer on adult females than on mature males.

Distribution.The new species is only known from cataracts of the rio Daraá (cachoeira do Aracu, Pacu and Panãpanã), a

tributary to the rio Negro, in the state of Amazonas, north-western Brazil (Fig. 4).

Etymology. The specific epithet daraha (Daraá in Portuguese) refers to the type locality.

Discussion

Several species of Rineloricaria have been described from the Amazon basin. Most of these represent a taxonomic chal-lenge due to poor original descriptions and unavailable type material.Rineloricaria phoxocephala (Eigenmann & Eigen-mann, 1889), described from Coary, and R. castroi Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1984, are commonly found in big rivers and float-ing meadows (pers. obs. – LRP). Both species are slender and with few abdominal series of plates. Rineloricaria phoxocephala has a more acute, long snout and dark dots on cephalic and lateral line pores that resemble R. daraha. How-ever, the dots on R. phoxocephala are really reduced and less dense than in R. daraha. Besides, R. phoxocephala has well-organized abdominal plates, rather than the scattered small plates on R. daraha. Rineloricaria castroi has con-spicuous markings on the fins, with large alternating bands of dark and light brown (Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1984: fig. 1). Rineloricaria lanceolata (Günther, 1868) and R. heteroptera Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1976, are often seen in small

sandy-bottom streams (pers. obs. – LRP) and can be identified by color pattern. Rineloricaria lanceolata shows conspicuous coloration consisting of black bands covering dorsal, anal, pectoral and pelvic fins (Isbrücker, 1973: fig. 2). Rineloricaria heteropteraresemblesR. daraha on the shape of the head and presence of densely marked dark blotches along the head and body, even reaching the ventral region in some speci-mens (Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1976; figs. 1, 2). However, R. heteroptera has a longitudinal band along the second and third dorsal-fin rays and large quadrangular abdominal plates organized in series, whereas R. daraha does not have any longitudinal dark bands on fins and the abdomen is covered by very reduced plates without any organization. Rineloricaria beni (Pearson, 1924), R. hasemani Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1979, R. konopickyi (Steindachner, 1879), R. mellini (Schindler, 1959), R. microlepidota (Steindachner, 1907), R. morrowi Fowler, 1940, R. teffeana (Steindachner, 1879) and R. wolfei Fowler, 1940 were reported from the mainstem of the Amazon (Reis et al., 2003) and are very poorly represented or misidentified in fish collections. Rineloricaria eigenmanni (Pellegrin, 1908), R. fallax (Steindachner, 1915), R. formosa Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1979, R. platyura (Müller & Troschel, 1848) andR. stewarti (Eigenmann, 1909) have been reported from the periphery of the Amazon, mainly Guyana Shield and rio Negro basin and represent a group of slender species with three to five organized series of abdominal plates.

Rineloricaria formosa, R. fallax, and R. platyura have a color pattern that resembles R. morrowi and R. melini: the presence of a conspicuous dark round spot on the supraocciptal or predorsal area (Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1979: fig. 2, R. formosa). Rineloricaria fallax is easily distinguished from R. daraha by the presence of a large dark spot bordered by two well defined lanceolate dark lines on the predorsal plate (Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1979).

More than 30 species of Rineloricaria were recorded from the Paraná, Uruguay and coastal drainages of northeastern, southeastern and south Brazil. All of those species have the abdominal area completely or partly plated (Rodriguez & Reis, 2008; Ghazzi, 2008). When completely covered, the abdomi-nal plates are organized in series and the preaabdomi-nal plate is surrounded by three large quadrangular plates. Otherwise, the abdomen is almost completely naked, showing only large quadrangular plates between the pelvis and urogenital open-ing (preanal plate and border plates). Despite the diversity of plating exhibited by these sepcies, none has the pattern de-scribed for R. daraha.

Rineloricaria daraha also share some characters with other loricariine genera. R. daraha, for instance, is unique in showing digitiform papillae on the lower lip surface. The elon-gated papillae on the lower lip and the lack of organization of the abdominal plates in R. daraha resemble the conditions in species of Loricaria.Loricaria, however, differs from all Rineloricaria by the presence of few and hypertrophied mandibulary teeth (R. daraha 7-8 vs.Loricaria spp. 3-5), long filaments covering almost the whole surface of both lips (vs. digitiform papillae on the lower lip, more concentrated near the mouth in R. daraha) and lack of a preanal plate (vs. a conspicuous preanal plate in R. daraha). In addition, even young specimens of Loricaria show long filaments on the lips, whereas young specimens of R. dahara have button-like papillae.

Among the Loricariinae, only representatives of the ge-nusLamontichthys and R daraha have seven branched pec-toral-fin rays. All remaining Loricariinae have only six branched rays on the pectoral fin (Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1978). Although the number of pectoral-fin rays and the lip struc-ture found in the new species are unique within Rineloricaria, sexual dimorphic features of the mature males are similar to those found in several species of Rineloricaria (R. castroi, R. phoxocephala, R. heteroptera, and others), and unlike those found in species of Loricaria.

An interesting aspect of Rineloricaria daraha concerns its distribution. Specimens of the new species were first col-lected by M. Goulding in 1980, then in 1991 by L. Aquino, R. Sotero and R. P. Ribeiro, and again, in 2008, by M. Rocha and Vitor Masson, all from the same locality. Several researchers have been collecting around this region in the Amazon, but no other sample has ever been obtained, suggesting that this species might be restricted to the type locality, rio Daraá. Despite the existing records, it seems unlikely that R. daraha is confined only to rio Daraá and its waterfalls. Some

Rineloricaria species show a wide geographic area of occur-rence (e.g.: R. heteroptera, R. lanceolata, R. castroi, R. phoxocephala – pers. obs.) but we are not aware of any Amazonian species of Rineloricaria with such a restricted distribution. On the other hand, disjunct geographic range has been registered on some representatives of Rineloricaria from rio Paraná, Uruguay and southern Brazilian coastal drain-ages (Rodriguez & Reis, 2008; Ghazzi, 2008).

Material examined. Brazil: Rineloricaria castroi: MZUSP 15731, holotype, 165.4 mm SL, Pará, Trombetas Biological Station, rio Trombetas, 1º0’S 57º0’W; INPA 19997, 6, 98.8-122.0 mm SL, Amazonas, Solimões, Paraná do Pirapora, Brasil; INPA 22123, 1, 122.97 mm SL, Amazonas, Manaus, rio Solimões, ilha da Marchantaria. Rineloricaria fallax: NMW 44864, lectotype (Steindachner, 1915), designated by Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1979, igarapé do Carauná, near Boa Vista, rio Branco drainage, Roraima, Brasil; paralectotypes: NMW 45046, 1, rio Branco, near Boa Vista, NMW 44867, 2 (only one specimen listed as paralectotype by Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1979), rio Branco, Boa Vista; NMW 44868, 1, near Conceição, rio Branco, Boa Vista; NMW 46159, 2 (only one specimen listed as paralectotype by Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1979), Bem Querer, rio Branco. Rineloricaria formosa: MZUSP 38997, 5, paratypes, 55.0-58.8 mm SL, Amazonas, Igarapé tributary of rio Uaupes; MZUSP 38969, 2, paratypes, 71.3-81.4 mm SL, Amazonas, igarapé Acaraposo, tributary of rio Tiquié; MZUSP 92367, 3, 113.80-127.39 mm SL, Amazonas, rio Negro drainage, rio Tiquié, 00º10’S 069º07’W. Rineloricaria heteroptera: MZUSP 38954, 7, paratypes, 68.14-109.98 mm SL, rio Amazonas, Manaus, reserve Ducke, 03º08’S 60º02’W; MZUSP 88996, 24, 56.92-120.79 mm SL, Amazonas, Manaus, rio Preto da Eva, 2º40’49.2”S 59º42’47.6”W; INPA 25862, 2, 107.0-139.7 mm SL, Pará, Oriximiná, igarapé Periquito, below Saracá mine, lago Sapucuá.Rineloricaria lanceolata: MZUSP 89303, 29, 36.9-86.8 mm SL, Goiás, Nova Crixás, drenagem Araguaia, córrego Pitomba, 140o08’35”S 050º20’13”W; MZUSP 81379, 9, 33.3-79.8 mm SL, Amazonas, rio Negro drainage, rio Tiquié, igarapé Onça, 00o13’52”N 69o51’5”W; MZUSP 23445, 18, 42.4-76.6 mm SL, Amazonas, Fonte Boa, Igarapé Tomé, Ati-Paraná, NW of Fonte Boa; MZUSP 93305, 1, 43.0 mm SL, Amazonas, rio Negro drainage, igarapé Cunuri (ou Maracu), 00o13’00”N 069o36’00”W; MZUSP 24131, 56, 50.1-87.9 mm SL, Pará, Jatobal, rio Tocantins, 04o32’S 049o32’W;

Rineloricaria phoxocephala: MCZ 49057, 1, paratype, lago Coari, Amazonas; INPA 25864, 1, 119.9 mm SL, Amazonas, Anavilhanas, rio Negro; INPA 22074, 4, 91.6-105.1 mm SL, Amazonas, Manaus, Paraná do Pirapora, rio Solimões. Rineloricaria platyura: NMW 44869 (paralectotype of Loricariichthys fallax), 1, Maguary (?), near Pará. Loricaria cataphracta: INPA 8408, 2, 162.2-167.9 mm SL, Amazonas, Coari, rio Solimões, mouth of lago Coari; MZUSP 57941, 1, 104.55 mm SL, Pará, rio Tapajós, below lago Azul.

Loricaria sp.: MZUSP 81257, 1, 171.01 mm SL, Amazonas, drenagem do rio Negro, rio Tiquié, small beach in pond below cachoeira do Caruru , 00o16’29”N 69º54’54”W. Guyana:

Rineloricaria fallax: NMW 44866, 5 (only one specimen listed as paralectotype by Isbrücker & Nijssen, 1979), Rupununi River.

Acknowledgments

manu-script; Michael Goulding, Luis Aquino, Raimundo Sotero, Roberval P. Ribeiro, Marcelo Rocha and Vitor Masson for collecting the available specimens; Leandro M. Sousa and Eduardo Baena for the illustrations; Edinho, Jander and Jandir from the Secretaria de Meio Ambiente de Santa Isabel do Rio Negro (Amazonas, Brazil) for providing the logistics in the 2008 field trip. MZUSP and INPA for the loan of specimens. FAPESP grant no 04/01839-5 to IF and CNPq (Edital Universal

2004) grant for L.R.P. Field trip of M. R. and V. M. supported by institutional projects of Jansen Zuanon and Lucia Rapp Py-Daniel (INPA). Collecting license IBAMA no.11696-2.

Literature Cited

Armbruster, J. H. 2004. Phylogenetic relationships of the suckermouth armoured catfishes (Loricariidae) with emphasis on the Hypostominae and Ancistrinae. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 141: 1-80.

Bleeker, M. P. 1862. Atlas Ichthyologique des Indes orientales Néèrlandaises. Tome II. Siluroïdes, Chacoïdes et Heterobranchoïdes. Amsterdam: 112p.

Boeseman, M. 1968. The genus Hypostomus Lacépède, 1803, and its Surinam representatives (Siluriformes, Loricariidae). Zoologische Verhandelingen, 99: 1-89.

Boeseman, M. 1976. A short review of the Surinam Loricariinae; with additional information on Surinam Harttiinae, including the description of a new species (Loricariidae, Siluriformes). Zoologische Mededelingen, 50 (11): 153-177.

Covain, R. & S. Fisch-Muller. 2007. The genera of the Neotropical armored catfish subfamily Loricariinae (Siluriformes: Loricariidae): a practical key and synopsis. Zootaxa, 1462: 1-40.

Eigenmann, C. H. & R. S. Eigenmann. 1889. Preliminary notes on South American Nematognathi. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences (Ser. 2), 2: 28-56.

Ferraris, C. J. Jr. 2003. Subfamily Loricariinae (Armored catfishes). Pp. 330-350. In: R. E. Reis, S. O. Kullander & C. J. Ferraris Jr. (eds). Check list of the freshwater fishes of South and Central America. Porto Alegre, Edipucrs, 729p.

Ferraris, C. J. Jr. 2007. Checklist of catfishes, recent and fossil (Osteichthyes: Siluriformes), and catalogue of siluriform primary types. Zootaxa, 1418: 1-628.

Ghazzi, M. S. 2008. Nove espécies novas do gênero Rineloricaria

(Siluriformes, Loricariidae) do rio Uruguai, do sul do Brasil. Iheringia, Sér. Zool., 98(1): 100-122.

Isbrücker, I. J. H. 1973. Redescription and figures of the South American catfish Rineloricaria lanceolata (Günther, 1868) (Pisces, Siluriformes, Loricariidae). Beaufortia, 21(278): 75-89. Isbrücker, I. J. H. 1980. Classification and catalogue of the mailed Loricariidae (Pisces, Siluriformes). Verslagen en Technische Gegevens, 22: 1-181.

Isbrücker, I J. H. & H. Nijssen. 1976. Rineloricaria heteroptera, a new species of mailed catfish from rio Amazonas near Manaus, Brasil (Pisces, Siluriformes, Loricariidae). Zoologische Anzeiger, 196(1-2): 109-124.

Isbrücker, I. J. H. & H. Nijssen. 1978a. Two new species and a new genus of Neotropical mailes catfishes of the subfamily Loricariinae Swainson, 1838 (Pisces, Siluriformes, Loricariidae). Beaufortia, 27(339): 177-205.

Isbrücker, I. J. H. & H. Nijssen. 1978b. The Neotropical mailed catfishes of the genera Lamontichthys P. de Miranda Ribeiro, 1939 and Pterosturisoma n. gen., including the description of

Lamontichthys stibaros n. sp. from Ecuador (Pisces, Silurifor-mes, Loricariidae). Bijdragen tot de Dierkunde, 48(1): 57-80. Isbrücker, I. J. H. & H. Nijssen. 1979. Three new South American

mailed catfishes of the genera Rineloricaria and Loricariichthys

(Pisces, Siluriformes, Loricariidae). Bijdragen Tot de Dierkunde, 48(2): 191-211.

Isbrücker, I. J. H. & H. Nijssen. 1984. Rineloricaria castroi, a new species of mailed catfish from rio Trombetas, Brasil (Pisces, Siluriformes, Loricariidae). Beaufortia, 34(3): 93-99.

Isbrücker, I. J. H. & H. Nijssen. 1992. Sexualdimorphismus bei Harnischwelsen (Loricariidae). Datz, 1992: 19-32.

Isbrücker, I. J. H., I. Seidel, P. Michels, E. Schraml & A. Werner. 2001. Diagnose vierzehn neuer Gattungen der Familie Loricariidae Rafinesque, 1815 (Teleostei, Ostariophysi). Datz-Sonderheft, 2: 17-24.

Montoya-Burgos, J., S. Muller, C. Weber & J. Pawlowski. 1997. Phylogenetic relationships between Hypostominae and Ancistrinae (Siluroidei: Loricariidae): first results from mitochondrial 12S and 16S r RNA gene sequences. Revue Suisse de Zoologie, 104(1): 185-198.

Regan, C. T. 1904. Monograph of the family Loricariidae. Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, 17(3): 191-350.

Reis, R. E. & A. R. Cardoso. 2001. Two new species of Rineloricaria

from southern Santa Catarina and northeastern Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (Teleostei: Loricariidae). Ichthyological Exploration of Freshwaters, 12(4): 319-332.

Rodriguez, M. S. & A. M. Miquelarena. 2005. A new species of

Rineloricaria(Siluriformes: Loricariidae) from the Paraná and Uruguay River basins, Misiones, Argentina. Zootaxa, 945: 1-15.

Rodriguez, M. S. & R. E. Reis. 2008. Taxonomic review of

Rineloricaria (Loricariidae, Loricariinae) from the Laguna dos Patos drainage, Southern Brazil, with the descriptions of two new species and the recognition of two species groups. Copeia 2008(2): 333-349.

Schaefer, S. A. 1997. The neotropical cascudinhos: Systematics and biogeography of the Otocinclus catfishes (Siluriformes: Loricariidae). Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, 148: 1-120.