INSTITUTO de CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS

Narratives and counter-narratives on “marriage of convenience”.

Conjugality and (il)legality in Portuguese migration policies and in couples’ experiences.

Marianna Bacci Tamburlini

Orientadora: Prof. Doutora Marzia Grassi

Tese especialmente elaborada para obtenção do grau de Doutor em Sociologia, na especialidade de Sociologia da Família, Juventude e das Relações de Género

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA INSTITUTO de CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS

Narratives and counter-narratives on “marriage of convenience”.

Conjugality and (il)legality in Portuguese migration policies and in couples’ experiences.

Marianna Bacci Tamburlini

Orientadora: Prof. Doutora Marzia Grassi

Tese especialmente elaborada para obtenção do grau de Doutor em Sociologia, na especialidade de Sociologia da Família, Juventude e das Relações de Género

Júri das Provas de Doutoramento, 30 Março 2016

Presidente: Doutora Ana Margarida Seabra Nunes de Almeida Vogais: Doutor Miguel de Matos Castanheira do Vale de Almeida

Doutor Pierre Henri Guibentif Doutor João Alfredo dos Reis Peixoto Doutora Marzia Grassi Bonacchi

Tese elaborada com o apoio da Bolsa de Doutoramento da Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia SFRH/BD/72765/2010

Solo tus etiquetas me dividen

This thesis explores the interaction between the mobility and conjugal trajectories of

married couples involving migrants in an undocumented position and the state regulation of residency rights in Portugal. In a context in which securitarian approaches prevail in European Union migration policies, family reunification is increasingly controlled and framed as a potentially fraudulent channel to evade migration restrictions and obtain residency documents. Namely, residency and nationality applications based on conjugal motives are the object of growing institutionalized suspicion. In 2007, the Portuguese government introduced a specific crime denominated as “marriage of convenience”, defined as a marital act that is contracted for the “exclusive purpose” of gaining residency rights (Law 23/2007). The implementation of this legislation by state authorities is based on the assumption that conjugal motivations may be investigated on the basis of institutional criteria capable of differentiating “genuine” marriages from “fraudulent” relationships.The research focuses on the underpinnings and repercussions of restrictive regulations, weighing institutional paradigms and practices against couples’ experiences. A qualitative case study was developed on the basis of interviews with both state representatives and married couples involving subjects in an undocumented or precarious residency situation. The thesis argues that the current mobility and intimacy control policies, notwithstanding the resistance enacted by some couples, impact in a discriminatory way on the opportunities and constraints faced by specific social categories. The empirical data indicates that restrictive migration policies (re)produce the stratification of subjects along gender, socioeconomic and national origin lines by regulating residency opportunities. The fundamental categories of illegality, marriage and migrant imposed through “marriage of convenience” policies reveal narrow and normative definitions, and thus consolidate a particular way of life and social profile as a condition for full citizenship recognition. This selection process fails to recognize the inherent complexity of transnational lives and relationships, and reinforces underlying unequal power relations by criminalizing marginalized social profiles.

No contexto das políticas migratórias de carácter securitário desenvolvidas nas últimas

duas décadas no seio da União Europeia, os canais de entrada e permanência nos estados membros foram sendo progressivamente limitados e regulados. A reunificação familiar tornou-se um dos canais mais utilizados no âmbito dos pedidos de autorizações de residência (Eurostat 2014) e contemporaneamente alvo de vigilância institucional. As relações familiares dos sujeitos que cruzam as fronteiras da UE são questionadas pelas autoridades alegando que os/as migrantes com um estatuto legal irregular ou precarizado poderiam falsificá-las para obterem um título de residência e direitos de livre circulação na União Europeia. Neste âmbito, aprovaram-se legislações que assentam numa visão criminalizadora e preveem requisitos específicos para os casais nos quais pelo menos um dos parceiros tem uma situação de residência “irregular”. No Estado português produziu-se uma tipificação de crime específica punível com penas de prisão de 1 a 5 anos (Lei 23/2007), que define o “casamento de conveniência” como um ato que tem por “único objetivo” adquirir direitos de residência. Com base na referida legislação, os casais que pretendem ter os seus direitos de residência reconhecidos através do seu vínculo conjugal são submetidos a um escrutínio institucional cujo propósito é averiguar se a sua intenção é a de contornar as leis migratórias.O enfoque da tese é o de captar a interação entre a regulação dos direitos de residência por parte das instituições estatais e as trajetórias migratórias e conjugais dos/das sujeitos/as em mobilidade. O objetivo é interrogar as normas que se alicerçam nos discursos, políticas e práticas institucionais relativas ao “casamento de conveniência” com base nas experiências e perspetivas dos casais submetidos à vigilância das suas práticas e percursos de vida. A análise desta articulação visa estudar as repercussões sociais desta interação em termos de desigualdade social, explorando como a regulação pública da conjugalidade e da mobilidade interagem com as hierarquias pré- existentes.

Com base em teorias críticas sobre as migrações indocumentadas (De Genova 2002), o direito à mobilidade é abordado como um processo institucionalmente regulado como um privilégio social, a partir da delimitação estatal de fronteiras materiais e/ou simbólicas. Num

teoricamente como um processo transnacional. Observa-se que a dinâmica conjugal atravessa, e é atravessada, por estas fronteiras contemporâneas, permitindo examinar as relações de poder contidas nestas articulações. A partir de uma releitura crítica dos conceitos- chave ilegal, casamento e migrante que se articulam na abordagem institucional baseada na noção de “casamento de conveniência”, questionam-se os mecanismos de inclusão e exclusão social inerentes na regulação contemporânea das fronteiras.

O trabalho desenvolvido, com o apoio de uma literatura multidisciplinar concentrada na relação entre as políticas públicas e os processos que alimentam as desigualdades sociais, contribui para um espaço de debate que se articula entre a sociologia da família e das migrações. Nomeadamente, o fenómeno dos controlos institucionais é investigado como um processo de reprodução da ordem social através da classificação e regulação dos laços familiares em âmbito migratório (Wray 2006, De Hart 2006, Grassi 2006, Kraler et al. 2011). Com o intuito de captar a influência dos múltiplos fatores de estratificação social que emergem na regulação estatal das migrações e nas práticas conjugais, a análise assenta, como suporte analítico, em uma perspetiva de género e interseccional (Hondagneu-Sotelo 2011, Kofman 2002, Gregorio Gil 2009, Yuval Davis 2011). A vigilância das relações conjugais é ainda interpretada como um processo incorporado no que se constituiu como uma batalha estatal contra a “ilegalidade” (De Genova 2002, Grassi e Giuffré 2013) e em dinâmicas mais vastas de exclusão social dos/das migrantes (Kofman and Sales 2001). Com base numa perspetiva de equidade social, a análise apresentada questiona as políticas públicas que tendem a selecionar os/as migrantes segundo a sua “desejabilidade” e conformidade a modelos prescritivos de “integração” assentes nos interesses de estado (Sayad 1999, Mezzadra 2012, Palidda 2010) e em modelos normativos de família (Kofman and Kraler 2006).

As reflexões reunidas nesta tese fundamentam-se em uma recolha de dados qualitativos, que permite captar a interação entre as práticas dos casais e a regulação institucional através de uma investigação empírica. Após uma análise documental no âmbito legislativo, no período de 2011 a 2014, foi desenvolvido na zona de Lisboa um estudo de caso focado na interação entre os casais e o Serviço de Estrangeiros e Fronteiras. O estudo inclui uma observação direta e entrevistas em profundidade focadas nas experiências e perspetivas de sujeitos/as

participantes. Por um lado, foram contactados/as representantes de entidades estatais e não estatais que tinham uma atividade profissional ligada às migrações em Portugal, incluindo principalmente funcionários do Serviço de Estrangeiros e Fronteiras e de Organizações Não Governamentais. Por outro lado, o destaque principal foi dedicado às entrevistas com casais heterossexuais nos quais um dos membros esteve numa situação de residência irregular ou precária anteriormente ao casamento ou união de facto, definidos como inter-status couples (Block 2009).

A seleção dos/as entrevistados/as foi determinada pelo estatuto legal assimétrico ao interior do casal, procurando diversificar as nacionalidades de origem. Esta escolha procura refletir uma perspetiva sobre a mobilidade que vai além da delimitação do estado-nação como categoria predominante na delimitação da investigação (Wimmer e Glick Schiller 2002). A análise pode de tal forma revelar lógicas e repercussões da classificação dos direitos de residência por parte do estado que são transversais à nacionalidade de origem dos protagonistas, como a classe social ou o género. Contemporaneamente, incluir indivíduos/as de várias origens geográficas permite captar eventuais discrepâncias no tratamento administrativo dos vários grupos segundo a sua área de origem. Com base nos dados empíricos pode-se depreender que a implementação das políticas de controlo da mobilidade e conjugalidade intervêm de forma discriminatória nas oportunidades e constrangimentos dos sujeitos entrevistados/as, segundo os perfis que lhes são atribuídos institucionalmente.

No âmbito dos serviços que regulam os pedidos de residência, os casais são objeto de práticas administrativas e investigativas que pretendem distinguir os casamentos “genuínos” daqueles classificados como “fraudulentos”. Nomeadamente, a observação, tanto do discurso como da implementação dos mecanismos de fiscalização, revelam os indicadores de “autenticidade” que fundamentam a seleção dos casais. Os critérios para obter a regularização dos documentos baseiam-se em definições normativas dos perfis sociais e formas de relacionamento legitimadas pelo estado, ligadas a noções estandardizadas da família nuclear ocidental e imaginários ligados ao amor romântico e “não instrumental” (Esteban 2011). Ao longo da investigação este binarismo de paradigmas e categorias institucionais é examinado frente à diversidade de práticas e percursos dos casais envolvidos nos controlos, expondo as

prescritivas de conjugalidade como pré-requisito para obterem uma validação institucional. O discurso institucional que justifica os controlos do “casamento de conveniência” baseia-se principalmente num alegado objetivo de combater a “ilegalidade” associada às práticas migratórias, e de proteger elementos da população considerados vulneráveis. Em primeiro lugar, a pertinência das atuais políticas como combate à “ilegalidade” é questionada argumentando que a inconsistência e formulação restritiva das próprias práticas estatais parecem constituir a base primária da precariedade legal dos e das migrantes. A conformação socioeconómica que assenta na exploração do trabalho precário, especialmente das pessoas que se encontram numa situação indocumentada, também contribui para estas formas de exclusão.

Em segundo lugar, o estudo revela que as políticas públicas reforçam imagens essencialistas com conotações de género muito marcadas, que provocam uma estigmatização de alguns grupos sociais. Exemplarmente, o discurso público referente aos casamentos inter-status, tende a reduzir a representação das mulheres envolvidas a potenciais vítimas ou criminais. Especialmente quando associadas a grupos socialmente marginalizados, as mulheres tendem a ser descritas pelas instituições como ingénuas, indefesas e/ou facilmente aliciadas por grupos criminais organizados que as exploram, representando as políticas restritivas como formas de “proteção”. Porém, o atual quadro legislativo promove ativamente a dependência legal entre os esposos e parece reforçar as relações de poder ao interior dos casais, especialmente quando são as mulheres a estarem numa situação de residência precária. As limitações derivadas da criminalização do casamento de conveniência associam-se às desigualdades e violência de género pré-existentes e podem aumentar a exposição das mulheres migrantes indocumentadas a abusos.

Em conclusão, os dados recolhidos demonstram que as políticas restritivas (re)produzem uma estratificação social baseada nos rótulos de género, classe e nacionalidade que são atribuídos por parte das instituições. As políticas atuais criminalizam os grupos marginalizados e agravam as condições de precariedade ligadas ao estatuto indocumentado, e não parecem responder às necessidades das pessoas envolvidas em situações abusivas e submetidas a dinâmicas de exploração socioeconómica. Contudo, as histórias recolhidas

muitas ocasiões são capazes de mobilizar recursos para as superar e subverter. Dando conta da complexidade de motivações, práticas e percursos, a tese sugere uma leitura das suas escolhas conjugais e de mobilidade que desconstrói a visão dicotómica e policial que compreende as classificações institucionais, além dos rótulos de “legal” ou “ilegal”, ou “amor” versus “conveniência”.

Palavras-chave: Migrações indocumentadas, Ilegalidade, Conjugalidade, Género,

INTRODUCTION 5

Research questions 9

Position in relation to previous research 10

Scope, objectives, and method 16

Contents 18

CHAPTER I 25

METHODOLOGY

SECTION 1-‐ EPISTEMOLOGICAL APPROACH 28 The evolution of the object of study 29

Reflexivity and situated knowledge 31

Research processes and “truth” 35

Challenging the research categories 39

Balancing structure and agency 41

SECTION 2-‐ METHODS 44

Qualitative approach 45

Data collection practices: oscillating between the empirical and the theoretical 46 Limitations and ethical issues linked to intimacy and “illegality” 50 The interviews: themes and participants 53

CONCLUDING REFLECTIONS ON METHODOLOGY 67

CHAPTER II 71

EXPLORING THE CHANGING NOTIONS OF MARRIAGE, MIGRATION AND ILLEGALITY A stance for a transnational approach 76 Mobility and bordering as alternative frameworks 78 Intersectionality as a tool to explore complex social hierarchies 82 SECTION 1-‐ CONJUGALITY IN DEBATE 85 Family and conjugality: changing conformations in “western” societies 88 Conjugal family and “romantic love” mentality as gendered social regulation mechanisms 93 Family models and migration regulations 97

SECTION 2-‐ “MIGRANT”: AN OTHERING CATEGORY OR A USEFUL ANALYTICAL TOOL? 102 The “migrant” category as a mirror of selective citizenship models 107 Studying migration discourse and policy: control and selection 111 Some implications of the global labour market in mobility processes 115 SECTION 3-‐ INSTITUTIONAL FRAMINGS OF UNAUTHORIZED MIGRATION: SECURITY AND EMERGENCY 118 The construction of “illegality” in the context of migration regimes 120 (Il)legality and the transnational division of labour 122

Naming and framing (il)legality 124

CONCLUDING REFLECTIONS ON THE THEORETICAL APPROACH 129

CHAPTER III 133

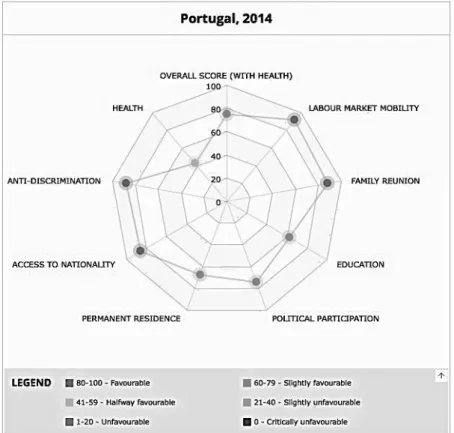

PORTUGUESE MIGRATION POLICIES AND LEGISLATION IN THE EUROPEAN CONTEXT SECTION 1-‐ MOBILITY IN PORTUGAL: A BRIEF FRAMEWORK 135 Colonialism, global inequalities, and contemporary mobilities 136 Portuguese migration policies: between “humanist” and punitive approaches 142 “Integration” policies: critical perspectives on international rankings 145 SECTION 2-‐ PORTUGUESE APPROACHES TO UNAUTHORIZED MIGRATION IN THE EU CONTEXT: CONSTRUCTIONS

OF “ILLEGALITY” AND SURVEILLANCE 149

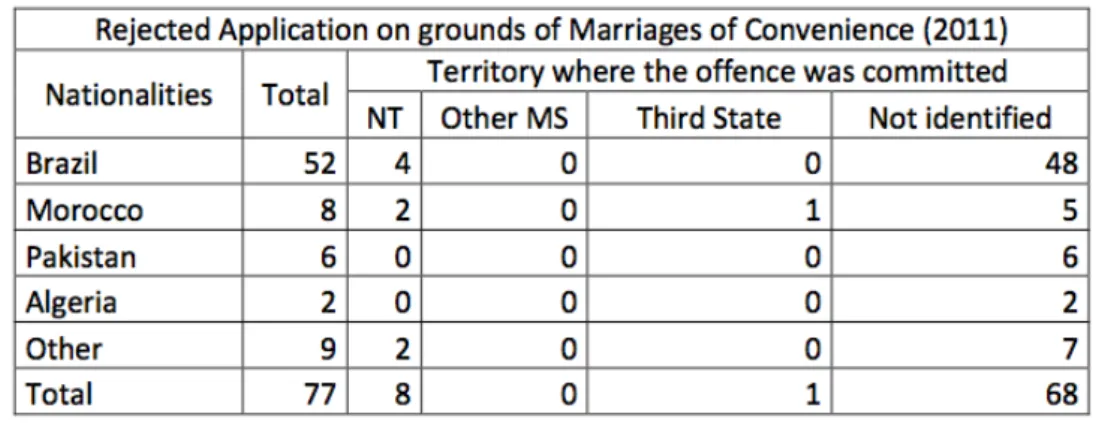

Framing and measuring “illegality”: state perspectives in Portugal 154 Institutional practices and (il)legalization processes 158 Economic management of migration policies: labour market and (il)legalization processes162 SECTION 3-‐ PORTUGUESE POLICIES ON CONJUGALITY AND MOBILITY IN THE EUROPEAN UNION CONTEXT 165 “Marriage of convenience” discourses: social order, security, and criminalization 167 “Marriage of convenience” statistics as ambivalent tools 169 Gendered connotations of migration controls: the “protection” discourse 171 Conjugality and mobility legislation: institutional procedures and “authenticity” scales 174 The functionaries’ perspectives: “problematic” social groups, class and nationality 179 Selection processes: “genuine” couples and social models 182

CONCLUDING REFLECTIONS: (IL)LEGALITY AND “MARRIAGE OF CONVENIENCE” REGULATIONS 185

CHAPTER IV 191

EXPERIENCING CONJUGAL TRAJECTORIES IN THE CONTEXT OF PORTUGUESE REGULATIONS

SECTION 1-‐ MARRIAGE “AUTHENTICITY” AND FAMILY NORMS 203

Institutionalized suspicion 204

“Plausible couples”: prescriptive conjugal models and transnational marriage 209 Institutional profiling and social stratification 211 (Self-‐) representations of conjugality: “love” and “convenience” 216 Fluid attitudes and motivations regarding marriage 220 Transnational marriage as an expression of agency 227 Questioning love, convenience, and authenticity claims 228 SECTION 2-‐ TRANSNATIONAL LIVES AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF (IL)LEGALITY 230

Administrative classifications 236

Bureaucratic (dis)services 240

“Illegality” as a label: repercussions and (self-‐)perceptions in everyday lives 245 The multiple impacts of migratory status on transnational conjugalities 247

Legal status and self-‐perceptions 249

(Il)legalization and social stratification 255 SECTION 3-‐ THE GENDERED IMPACTS OF “MARRIAGE OF CONVENIENCE” RESTRICTIONS 257 The tutelary attitude of the state: gendered constructions of vulnerability 258 Power, dependency and (il)legality in the context of marital breakdown 263

Gendered risk profiles 266

Intersectional power relations and social stratification 273 Nationality, gendered stereotypes and moral norms 277 Gender-‐based violence and the role of institutions 279 Can “marriage of convenience” control “protect” women? 281

CONCLUDING REFLECTIONS: NEGOTIATING CONJUGALITY AND RESIDENCY RIGHTS 284

CONCLUSIONS 291

Migration policies and discourse: demarcating and crystallizing difference 295 Reflecting on the case study: charades of authenticity, illegality and protection 298 Structural factors, state interventions and couples’ agency 302 Limitations and future research avenues 306

INTRODUCTION

…desbordando las categorías claras y distintas, las promesas de pureza y separación; proponiendo nuevas geometrías posibles para considerar relaciones atravesadas y constituidas por diferentes diferencias.

In a context of ever-stricter regulation of human movement across the external borders

of the European Union, individuals’ access to stable residency rights is determined according to a division between “legal” and “illegal” mobility flows. Amongst subjects labelled as migrants, such regulations tend to create a pool of individuals with an undocumented1 status, whose ability to secure residency or citizenship rights is considerably restricted. In such political context, migration related to family reunification -institutionally framed as a potentially abusive channel to circumvent restrictions - has been the object of increasing institutional anxieties and regulations. Specific legislative tools have been progressively introduced by member states to regulate family-related residency rights as part of a “battle against illegal migration” (Wray 2006, De Hart 2006, Kraler et al. 2011).Against this backdrop, the Portuguese government introduced the specific crime of “marriage of convenience”, defined as a marital act that is contracted for the exclusive purpose of gaining residency rights (Art. nº 186, Law 23/2007). The consequent regulatory framework enables the state to place couples in which one of the partners is in an undocumented or precarious residency situation under specific institutional surveillance. Although according to family reunification legislation these marriages imply the right to apply for residency authorization or nationality, these applications may be obstructed on the basis of migration authorities’ suspicions. State authorities aiming to verify whether the couples are attempting to circumvent national immigration laws scrutinize their life trajectories, motivations to marry, and conjugal practices.

The institutional procedures aimed at the surveillance of conjugalities inevitably lead to discrimination in terms of the citizenship opportunities of inter-status couples, in which the two members have different legal status (Block 2012). The specificity of these couples is that by marrying, the partner with a precarious residency gains the right to apply for stable residency rights on the basis of family reunification with the other spouse, who has Portuguese nationality or permanent residency. Through a set of mechanisms of surveillance, state institutions in charge of implementing “marriage of convenience” controls impose normative notions of marriage, creating specific formulas of inclusion and exclusion according to pre-defined conjugal models. The securitarian paradigm within which such

policies seem to be operating constitutes a basis for the criminalization and reduced access to residency rights of certain social categories. These institutional categorizations are based on individuals’ level of adherence to the model established by authorities regarding the practices of a “genuine” marriage or a “desirable” migrant (Mezzadra 2012, Palidda 2010).

Due to the deep implications of these administrative processes in terms of social exclusion and interference in significant life choices, we may affirm that the most fundamental parameters and values upon which democratic values rest are being challenged in the debate on migration (Dal Lago and Orton 2009). There is therefore a need for analysis of the exclusionary formulas through which migration is regulated by states, and of these policies’ underpinnings and repercussions in terms of equality. Unauthorized migrants are living and widely participating in all European Union countries, where their contribution and participation is crucial for the perpetuation of current economic and social structures. Yet in all member states, policies are put in place to deny or filter migrants’ access to full citizenship rights, often justified through the institutional association of “illegality”, “criminality” and “risk” with mobility processes.

The articulation of conjugality and unauthorized migration constitutes a particularly salient analytical focus to explore within broader contemporary citizenship and bordering processes, especially with regard to the reproduction of inequalities. Unpacking the regulations affecting transnational couples enables us to expose how public policies regulating matters that are generally regarded as private and intimate potentially imply double standards. While individuals in the dominant groups in society gain increasing autonomy in deciding how to organize and live their conjugal lives, subjects who do not fit into the normative profiles or migration priorities of the state are objects of scrutiny and selection. Emblematically, the guidelines of the Portuguese immigration police mention “marriage with pre-nuptial agreements, such as separation of marital property” and “marriages with indigents, prostitutes or persons with mental disabilities” as examples of “marriage of convenience” suspicion indicators (EMN 2012:11-12). Migration regulations appear to be embedded in broader processes of social discrimination, in which factors such as class and gender become crucial. Additionally, policing approaches inevitably introduce a double standard regarding the opportunities for self-determination of subjects, on the mere basis of the nationality and migration status they have been ascribed. Borrowing a medical metaphor, it is therefore

important not only to retrace how “marriage of convenience” has been constructed as a social pathology, but also to examine the processes through which it is “diagnosed” and “cured”. Focusing on the articulation between marriage and migration is considered to be a way of shifting away from the prevailing public discourse justifying the proliferation of spectacular enforcements, detention centres and walls. These most visible and concrete enactments of “Fortress Europe”, invariably frame migration as an “emergency” and as an external process taking place at its frontiers. I deem important to think beyond this paradigm of exceptionality, and consider how the effects of mobility and its control are permeating our whole society, and the way it is institutionally ordered. This somehow reversed perspective fosters a deeper reflection on how exclusionary dynamics operate in conditions of “normality”, through routine administrative practices, by building more subtle -but similarly discriminating- social borders. For instance, migration law functions primarily through bureaucracy, which filters the access to rights in indirect, long-term and partly invisible ways, as hinted at in Henk Van Houtum’s article “Kafka at the border” (Van Houtum 2010). The more or less cumbersome bureaucratic path that applicants are obliged to follow to gain residency authorizations is acting as a mechanism of exclusion concealed by an apparent neutrality, and acts on subjects who are for the most part already living in the country, rather than attempting to enter it. Focusing on the particular configurations of conjugality, and the processes linked to everyday practice and relationships, may relativize the mediatized images of “emergency”, and thus contribute to a debate which potentially encompasses the roots of routine exclusion, beyond and within the constructed borders of the state.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The growing institutionalized interference in marriage and migration prompts a number of questions regarding the assumptions and implications of institutional bordering efforts. Namely, what are the repercussions in terms of social stratification processes of the recent criminalization of “marriage of convenience” in Portugal? What are the institutional understandings of “migrant”, “illegal” and “marriage”, on which such criminalization is based? By what criteria and procedures is the law applied, and are some social groups subject to more surveillance than others? What are the effects of the current institutional procedures in terms of opportunities for regularization and conjugal trajectories of the partners involved,

and to what extent their practices may challenge the current migration regime and conjugal norms?

This set of empirical research questions will be applied to studying the functioning and implications of “marriage of convenience” control, both at the institutional level and from the point of view of couples subject to control procedures. I will investigate which factors mediate the repercussions of an apparently neutral regulatory framework, to ascertain whether it is applied with differentiated procedures according to the social profile of couples. An overarching interrogation will examine the role of the state in shaping and constraining conjugal and mobility trajectories, based on the filtering of citizenship statuses. In this sense, my research constitutes an exploration of the effects of marriage and migration control as a process of social exclusion, intended as a set of dynamic, multidimensional processes “which prevent individuals and groups from participating in the rights that the members of a social and political community would normally expect to enjoy” (Kofman and Sales 2001:98).

POSITION IN RELATION TO PREVIOUS RESEARCH

An overarching theme of the dissertation lies in untangling how state institutions classify and interfere with mobility and conjugality, and exploring the effects on, and reactions of, the human beings involved in this process. Analysing the institutionalized demarcation of difference through migration regulations, may be seen as a step towards understanding the hierarchies embedded in wider contemporary social relations. I consider it useful to treat migration and illegality categories as specific ramifications of more complex power dynamics, intersecting with the effects of categories such as gender, nationality, and socioeconomic class. I work with the hypothesis that, rather than being inevitable, the naturalization of social hierarchies through the establishment of residency rights may be seen to attest to the persistence of power relations based on “otherness”.

To approach these conceptual challenges, my research builds on a vast range of scholarly literature areas, which influenced my thinking about mobility and the construction of borders, including both their administrative and social connotations. Thanks to the freedom involved in the PhD as an individual and relatively long-term research project, I had the opportunity to benefit from a variety of disciplinary contributions to serve my research objectives. During

my research I interweaved these inputs in order to question not only a contemporary social phenomenon, but also to reflect on the way in which it is approached at the academic level, and through which classifications it is studied. Although establishing a privileged dialogue with the literature pertaining to migration and family, the analysis exposed in this study might not fit neatly within strictly demarcated disciplinary fields.

It is worth acknowledging that in order to serve the context-specific interrogations sparked by my fieldwork, I stretched, mixed or adapted some of the most commonly-used research scopes and methods. Firstly, rather than looking at migration as a phenomenon in itself -and considering migrants as an object of study- I invert the perspective. In particular, I use the observation of couple’s practices to analyse migration control as a mechanism revealing the nature of institutions’ relations with a specific society. The way in which I conceptualize the case study is in this sense indebted to the reflections of the sociologist Abdelmalek Sayad. I consider particularly stimulating this author’s acknowledgment of the “secret virtue” of migration: for Sayad, this virtue lies on its capacity to mirror the limits of the state’s intrinsic essence, which is to discriminate between “nationals” and “others”. As the author himself suggests, to think about immigration is to think about the state, and the state “thinks itself” by thinking immigration (Sayad 1999a:6, my translation). Building on this line of thought, we may consider migration in general as a perturbing presence, challenging the state’s mythical homogeneity in the political, social and economic senses, as well as exposing the porosity of its margins.

In line with some ealier contributions in Portuguese literature (Grassi 2006), the scope of my reflection moved beyond the narrowest delimitations of “migration studies”, as it emerges in the academic context in which I am situated (cf. Machado and Azevedo 2009). In particular, it attempts to go beyond the study of social relations as if they were naturally embedded and contained within nation states (Smith and Guarnizo 1998, Portes et al. 1999, Levitt and Glick Schiller 2004). To this end, I found useful the literature on transnational families (Bryceson and Vuorela 2002, Yeoh 2015), which constitutes an emerging research area in Portuguese academia (Grassi 2006 and 2012, Grassi and Vivet 2015, Raposo and Togni 2009). I set to interrogate this body of work from a methodological perspective that seeks to overcome the predominant focus on nationally- or ethnically-delimited “target groups”. Without belittling the advantages of producing studies with a detailed knowledge of the participants’ backgrounds and origins, I would argue that nationality is often used by default as a founding category for migration studies. Specifically, it is a naturalized -but potentially essentialist-

procedure in migration studies, to choose categories which are seen to represent a specific national or ethnic “community”, as if they could be considered by default as a homogeneous group, or as a self-delimiting object of study. Formal nationality may correspond only partially to belonging and individual ties to a place, such as may be the case of children born in Portugal who are attributed the parents’ nationalities even though they may never have travelled to other countries. The present research is therefore not limited to migrants from one country or ethnic background: such option is considered a step towards building categories based on individual trajectorias and life experiences, rather than on the basis of birth or residency documents emitted by nation states. Moreover, by choosing the theme of conjugality I extend the logic of this choice further, expanding the fieldwork beyond the group of individuals framed as migrants to include individuals holding Portuguese or European nationality.

The research was designed with the conscious intention to avoid treating migrants as a separate section of society, but rather as social actors with practices - in this case, conjugal practices - which are interwoven with the actions and choices of formally recognized Portuguese citizens. This choice is based on the acknowledgement that social life takes place “across borders” (Levitt and Jaworsky 2007:129, emphasis added), but also that borders, material or symbolic, migratory or social, may have effects within national territories as well. In my approach, migrants and non-migrants are thus seen as differentiated by legal status, but possibly bearing similar processes of social stratification, based on transversal markers of difference such as gender and class.

I start from the appreciation that conjugal relationships between inter-status couples may be better investigated from a transnational perspective, since the couples are subject to legal regimes that go beyond the country in which they reside. In my usage, transnational defines a social space crossing nation states, and comprising of relations that go beyond their borders. The term may consequently be used to define a type of conjugality that is inevitably marked, to some degree, by simultaneous effects of laws of different states, or supra-national entities such as the European Union.2 For instance, some of my research participants have two nationalities, one of a European country and one of a non-European country, making their perception through a single national and legal dimension unviable, as they are affected by

2 As will be thoroughly explained in the theoretical discussion, in this sense my usage stretches a more common

definition of transnational social relations as requiring “regular and sustained social contacts over time and across national borders” (Portes et al. 1999:219).

overlapping sets of laws. In this sense, the complex legal trajectories of the couples that I involved in the research, highlight the paradoxes of state interventions that compress them within clear-cut and nationally-framed labels.

Consequently, as will be discussed in more detail in the methodological chapter, I looked for an approach that would serve my desire to look at social stratification processes beyond national categories. As a result, I chose to use as a delimitation of inter-status couples only their asymmetrical legal status, meaning the only characteristic that all couples shared was that their conjugal relation implied one spouse’s potential transition from one legal status to another in the context of current Portuguese regulations. I saw the option of choosing interlocutors through this minimal common denominator as a way to emphasize the complex and multi-layered issues involved in the construction of illegality, rather than focusing on alleged cultural factors or ideas of “mixedness”.

In order to grasp how mobility trajectories and opportunities could intersect or be compared to other systems of subordination, I used elements deriving from traditions of thought including feminist and postcolonial/decolonial studies (Segato 2012, Grosfoguel 2012). These critical inputs produced destabilizing but enriching effects on the research approaches I adopted, by exposing the limitations of simplistic and apparently “neutral” approaches to scientific methods and categories. As a result, I made an effort to produce a research grounded in the idea of a participatory approach to the construction of knowledge, that would be “available” to the subjects involved in first person in the social mechanism under observation (Segato 2012). During the research process I also complexified my gender perspective, moving beyond the depoliticized observation of differences between men and women’s mobility trajectories, to which the scope of migration-related studies is sometimes limited. This shift led me to unpack the gendered power relations involved in public policies, and how these are inserted in broader, intersectional asymmetries (Hondagneu-Sotelo 2011, Kofman 2002, Gregorio Gil 2009).

The delimitation of the interviewees is a response to braid issues of mobility, residency rights and transnationalism which are often only partially acknowledged in many studies pertaining to the sociology of the family. Often “migrant families” or “mixed families” are relegated to separate studies, as if their social practices were a priori distinct. I noted how transnational couples are erased from major studies in this area, unless specifically dealt with in sections dedicated to migration (Varro 2000). I wished to study the effects of the migration regime, but

to avoid basing my inquiry on the notions of “mixed” or “bi-national couples”, as I felt that these would make the articulations between class, nationality and gender less visible in my research context. To enter into dialogue with the specific subject of marriage in contexts of mobility, I attempted to provide a nuanced vision of conjugality involving partners with different legal statuses, while at the same time problematizing standard institutional definitions of marriage. Throughout my study, I referred to marriage based on its legally-sanctioned definition in Portugal, in order to describe the formal implications in terms of bureaucratic mechanisms. Yet, I challenge this legally clear-cut notion by questioning its naturalized association with normative notions of “love”, “family” and “authentic motivations”. As will be discussed, I did so by confronting the legal definition with a much broader signification emerging from the empirical data. I thus investigated the potential of grounding the study in an open-ended conception of conjugality (Luibheid 2015), in order to grasp the couples’ own representations of their relationship (e.g. tracing if, and to what extent, they considered it “conjugal”), rather than trying to categorize it through pre-packed definitions.

During the initial phase of my study, I identified the guidelines of state approaches to the theme of family reunification, and their underlying assumptions, in order to experiment with alternative perspectives. This review suggested how my open-ended approach could enter into a constructive dialogue with studies focussed on the discriminatory effects of “marriage of convenience” controls (Wray 2006, Charsley 2012, Muller Myrdahl 2010, Friedman 2010, D’Aoust 2013, Block 2009). These academic contributions tend to emphasise how laws can keep couples apart, and call for a recognition of equal rights to family and marriage. While recognizing and embracing the operative importance of such family-rights perspectives as advocacy tools for migrants’ rights, I believe the theoretical discussion may go further than “right to marriage” demands. I propose to stretch the discussion to a more radical questioning of the legitimacy of state interferences in family life through migration law, including a challenge to the state-imposed normativity in terms of authorized conjugal forms. This research frame might play a role in untangling crystallized equations based on state mentality, such as those linking rights of residency to specific (and increasingly limited) types of family relationships. Deconstructing state assumptions may open space for debates exploring the possibilities of autonomous recognition of residency rights for individuals, on a universal basis, or based on social participation or “stakeholder” parameters (Bauböck 2008).

As I will discuss along the next chapters, I also move away from treating marriages involving subjects classified as “non-European” as an “integration” issue (Fonseca 2005). The analysis of state policies allows us to observe how often this type of concern is selectively directed, particularly towards subjects who are ascribed by default a “different” culture (e.g. often non-“Western”), reflecting othering and ethnicized assumptions regarding their “integrability”. My case study attempts to overcome what I regard as utilitarian portrayals of family reunification as either a “barrier” or “facilitator” for social inclusion (Strik et al. 2013). Additionally, although I found the literature on the legal aspects of “marriage of convenience” regulations extremely useful (Demleitner 2004, De Hart 2006), and built on it extensively in the analysis, I consider this research perspective would benefit from a closer dialogue with studies looking at the messier sphere of law implementation at the micro level (Friedman 2010). In particular, collecting primary data allows us to perceive the gaps between formal policies and implementation, as well as the complexities and nuances visible only through empirical research. My study thus moves towards integrating in the picture empirical material on couples’ everyday experiences and direct interactions with the bureaucratic system. As a growing body of research attests (Charsley 2005, Riaño 2011, Roca Girona et al. 2012, Fernandez and Gudrun-Jensen 2013), this approach potentially sheds light on some relatively blind spots in this specific area of research, where most of the literature focuses on official policies and on administrative management, rather than on couples’ lived experiences.

A significant proportion of the studies on “marriages of convenience” regulations that I have quoted are concentrated in the northern European countries where, according to my interpretation, migration discourse has specific thematic connotations (Eggebø 2012, Muller Myrdahl 2010, Wray 2006). Notwithstanding the profound similarities with the Portuguese case in terms of increasingly punitive trends, anxieties around migration in countries such as Denmark, the United Kingdom, Netherlands or Sweden appear to have slightly different configurations. From what emerged in my literature review, islamophobic concerns, and the fears that migrants might import patriarchal or “backward” customs, appear to shape public policies in these countries to a larger extent than in Portugal (cf. Van Walsum 2011, Schmidt 2011). Building on previous studies, which cleared the way for the elaboration of my object of study (Grassi 2006, Raposo and Togni 2009), this thesis therefore sheds light on the particular articulations occurring in the contemporary Portuguese context, with an exploratory intention. Setting my study in the context of Portuguese legislation called for a particularly nuanced analysis, to make sense of apparent contradictions in the country’s migration policies.

Creating a particularly stark contrast with its punitive legislation on “marriage of convenience”, Portuguese governments’ discourse on migration is otherwise mostly moderate and “humanist”, and presents a “benevolent” façade concerning migrants’ right to family. Understanding this local specificity requires a closer look at the gaps between the official narrative of state discourse and practice. Choosing to tackle Portuguese policies through a qualitative appraisal of couples’ counter-narratives, enables me to inquire the less visible barriers and the more subtle mechanisms of social hierarchization.

SCOPE, OBJECTIVES, AND METHOD

Inter-status couples have been chosen as protagonists of the case study because they may be seen to embody many of the contradictions and mechanisms of contemporary bordering, and provide particularly vivid examples of the prescriptive function of legislation and its categories. These relationships - and the way they are classified and recognized - constitute a space of interaction where power dynamics articulating through state, gender, and class are particularly visible. The processes involved in the control of the couples’ conjugal trajectories underline the need for reconsidering the impacts of state rhetoric and regulations on the lives of individuals who cross borders or, as we may rather argue, whose lives are crossed by borders. At the same time, rather than seeing these subjects as passive recipients of policies, the case study reveals the extent to which the couples’ practices are capable of subverting and producing infinite nuances in the imposed categories. The research participants’ representations and practices are discussed as active interventions shaping the outcomes of the contemporary regulatory complex. Their marriages may indeed be seen as a crossroads, contributing to challenge both the border and the neat administrative categories used to perpetuate the current social order.

The exploratory fieldwork, in dialogue with the above-mentioned literature on “marriage of convenience”, systematically revealed the tension between the monolithic institutional imaginary regarding illegality, and the mosaic of everyday practices of individuals engaging in mobility. The observation of this gap between categories and observed practices suggested a series of concrete research objectives. The aim of this study is to explore the limitations of state authorities’ binary portrayals of inter-status marriages as either cynical vehicles for immigration benefits, or as “genuine” relationships based on idealized romantic love notions

and normative family expectations. A related goal is to contribute to a nuanced understanding of inter-status conjugalities, challenging the prevailing “marriage of convenience” narratives and control practices in the specific Portuguese context. In particular, I wish to emphasize why and how conjugal practices of subjects pertaining to specific social profiles are being constructed as problematic in the contemporary Portuguese administration context.

Alongside the more “empirical” objectives presented above, I consider important to situate my research within my broader interests. My academic and work trajectory has been driven by a desire of critically engaging, albeit from an inevitably privileged social position, with the power asymmetries on which social inequalities are constructed. I consider this a means to reflect on my own position in society and to enable transformative reactions, even if at an extremely small scale. This action-oriented spirit needs to be acknowledged, since it has greatly influenced my approach to the PhD research. By interrogating the social mechanisms in which the couples are embedded, my research also responds to a wish of contributing to on-going conversations about citizenship, social stratification and the meaning of borders.

Understanding the premises through which human mobility has been converted into a social and political problem, and the ways in which migration control has been conceived and approached, is part of my theoretical effort. In this sense, my work is inspired by previous academic efforts to uncover the empirically and theoretically unsound aspects of current systems of migration surveillance (De Genova 2002, Sciortino 2004, Mezzadra 2012). Although grounded in a limited research scope tied to my case study, I wish to provide theoretical arguments for an admittedly policy-oriented demystification of the issue of “illegality” associated to migration. The overarching purpose of my academic engagement is to uncover the historically and institutionally situated production of “illegality”, and to

unsettle normative discourses regarding human mobility and its categorization. This interrogation, rather than aiming at definitive answers, will hopefully lead to a broadening of the scope of the initial research questions. In particular, I believe that this perspective can offer insights into what the policies and practices observed in “marriage of convenience” control can tell us about how social relations are re(produced) in the wider political context, and identify possible spaces of resistance or negotiation.

To serve the above objectives, I needed to untangle the layered and dynamic social relations beyond the formally defined laws and norms, and chose to ground my theoretical reflections in a qualitative analysis. The case study has been developed to gain more focused insights into

how the construction of illegality intersects with small-scale socioeconomic stratification dynamics, in the Lisbon urban area. As a result, while in some facets of the reflection I will take into account the possible interactions of the migration regime with the global effects of neoliberal economic frameworks, the empirical material was collected in a restricted setting, and its interpretation may not be automatically generalized. The arguments that will be presented here are framed in the specific context of Portuguese legislation, economy and history, and deeply tied to the characteristics of the research participants.

Due to the complexities of the theme, and logistical and ethical constraints such as the need to maintain standards of anonymity, the group of interviewees has a relatively limited scope in numerical terms. Between 2012 and 2014 I developed various sets of interviews with 26 individuals engaged in heterosexual marriages or civil partnerships in the city of Lisbon, and followed their process of regularization and conjugal trajectory. In some cases I met these participants several times in order to update the data and consult them regarding its analysis, during the fieldwork period. My research is thus mainly based on interviews focused on the micro-level interactions of couples with the state administration, as well as observational and documental data collected in Portugal. This fieldwork has enabled me to capture the inconsistencies between the discourse and practice of the regulatory system, by inserting in the picture the discontinuities, ruptures, and shifts emerging from the counter-narratives of individuals who are dealing with its tangible implications. This approach is seen as a way to produce richer investigations on the underpinnings and repercussions of polarized institutional formulas, taking into consideration the perceptions, representations and reactions of the actors involved.The qualitative study enabled a deeper insight into the specificities of each couple’s trajectory, reflecting the diversity and nuances of their experiences rather than producing generalized typologies.

CONTENTS

My argument will unfold in four chapters and a concluding section. Although they are all conducing to a set of central arguments, I opted to provide contextual information on the broader research in all of the chapters, so as to make each one of them legible as a stand-alone section. Each will have some concluding reflections that briefly summarize its contents, in order to allow the conclusive chapter to be more synthetic.

Chapter One will outline the methodological structure of the thesis, tracing the ways in which I defined the epistemological framework and methods for the research. This section will be an opportunity to expose my reflexive trajectory, acknowledging my position as a researcher, and the limitations and opportunities derived from my angle of observation. I will also delineate how I responded to the challenges deriving from interview contents that touched on the intimate sphere and could potentially leave interviewees at risk of legal prosecution. With the aim of reducing ethical hazards and enabling an engaged interaction with research participants, I involved my interlocutors in several informed choices regarding the disclosure of their stories, so as to avoid contributing to possible legal sanctions and stigmatization. These epistemological and ethical underpinnings have been crucial in defining the methods for the case study, which were designed as flexible tools, adaptable to the specificities of a field involving constant transformation. The chapter will argue for the appropriateness of producing a qualitative study, based on interviews with transnational couples and state representatives, to better fit my research objectives, while also providing a reasoned account of the specific procedures adopted in the fieldwork.

Chapter Two sets out the analytical background, acknowledging the main theoretical contributions which structure the dissertation. I will describe the particular ways in which I combined an overarching gender approach with a transnational and intersecting approach, focusing on bordering mechanisms. The bordering approach is used to reflect the resources and agency of the subjects involved, while at the same time taking into account the intersectional factors involved in the regulation of mobility and intimacy. I will make the case for looking at transnational conjugality with a bordering lens, to avoid reinforcing the “othering” mechanisms potentially implicit in adhering to categories based on state priorities. Subsequently, the discussion will focus on the binary perspectives based on dyads such as citizen-migrant, legal-illegal, and authentic-fraudulent marriage, exploring the margins of these concepts and their usage in both the academic and administrative spheres. The case will be made that using a dichotomist dimension to frame social experiences theoretically and burocratically, leads to an impoverished understanding of the inherently multi-dimensional factors at play in lived realities.

Through a systematization of what I consider the most salient contributions from different disciplines, I will frame the core concepts of migrant, conjugality and illegality in time, space and social context, proceeding to elucidate the specific usages that I deem appropriate to

approach my object of study. I will situate my work in a research current attempting to reject the criminalizing association inherent in the expression “illegal migrant”, a concept which, like nationality, has been often treated as a self-evident category both in state discourse and in academia (Sciortino 2004, De Genova 2002). At the same time, I will maintain a watchful attitude towards the automatic adoption of alternative labels such as “undocumented migrants” as if they were universally applicable and self-explanatory. Although I use this expression when necessary for my argument, I acknowledge that this and other classifications may comprise highly diverse legal situations and life trajectories. I will argue that such categories do not represent self-evident and universally recognized social groups, but instead conceptually reflect power relations and social stratification, based for instance on colonial relationships and its legacies, such as the global distribution of labour and resources.

Chapter Three will trace the conceptual and legislative underpinnings of conjugality and migration control from the point of view of institutional discourse and policy, with a specific focus on legislative processes at the national level. After outlining the specificity of mobility processes in Portugal, this part of the thesis sheds light on the proliferation of family-related migration restrictions in the context of migration policies in the European Union. The reasons and justifications adduced by state authorities to interfere in conjugal processes will be discussed as a background. I will then critically analyse the premises and implications of such policies, namely the association of the idea of “illegality” with migration phenomena in the specific context of national legislative processes in Portugal. The chapter will then proceed to observe how laws and regulations are put into practice, in particular how state representatives in administrative procedures apply normative notions of marriage “authenticity”. The current legislation is built on the assumption that narrow institutional concepts of what constitutes an “authentic” conjugal relationship may be considered a universal standard against which all marriages can be measured. This section of the analysis untangles how the bordering paradigms which led to specific regulations on “marriage of convenience” are based on securitarian logics and dichotomist categorizations, and how these regulations may be seen as additional ramifications of migration control and selection.

Chapter Four will set out the findings resulting from the fieldwork with inter-status couples, with the objective of weighing the declared objectives of institutional “marriage of convenience” control against its actual outcomes. The result will be an exploratory immersion into the conflictive and irreducible diversities of lived experiences, upon which policies tend

to impose clear-cut divisions, with an emphasis on how the experiences collected in the fieldwork potentially destabilize the categories on which state regulations are built.The group of interviewees included, for instance, couples that had already separated but had decided to maintain the formal bond of marriage to avoid the loss of residency rights for one of the partners. Other couples, notwithstanding a longstanding commitment, reportedly would not have married otherwise, but felt pressured to do so because of restrictive migration regulations which they felt as impediments to their commitments or their life projects. This diversity exposes the paradox of regulations that are based upon homogenizing categories, as well as the ways in which such laws have significant repercussions on couples’ options.

On the basis of the research participants’ perceptions and opinions collected in the interviews, I will set out to interrogate the administrative paradigms, clustering the discussion of the empirical data in three thematic sections. The first section will retrace how normative family models are imposed, through institutional “authenticity” measures that prescribe the “legitimate” family modes, eligible to gain residency authorizations. In this frame, only couples who fit into externally defined forms of relationship - including cohabitation, timing of commitments, mobility patterns, reproductive aspects and financial arrangements - are accepted as “genuine”. Conversely, I will emphasize how the complex and overlapping motivations involved in transnational conjugal relations potentially subvert these categorizations. Marriages may for instance be considered as political acts, romantic rites, economic opportunities, and/or mobility enablers, sometimes simultaneously, and in some cases may constitute “acts of resilience in the face of global inequalities” (Luibheid 2015). It will be argued that most practices observed may be seen as coherent plans to pursue specific life projects - with varying and overlapping motivations.

The second section of the chapter will measure the declared objective of curbing illegality against the actual obstacles to regularization of residency, highlighting the extent to which the production of illegality is produced by bureaucratic malfunctioning, inconsistent information and systematic discrimination. The couples’ narratives will be used to inquire into the gaps between an apparently neutral legislation, and its discriminatory application. Additionally, the interviews suggest to reflect on how subjects’ labelling as “irregular” migrants, and the exclusionary effects, are highly dependent on their previous social status and on the state’s arbitrary classifications.

The final section of Chapter Four will analyse the state authorities’ claims of “protection” towards vulnerable individuals, dissecting the functioning of related policies through a gender perspective. In particular, it will trace how women institutionally framed as poor, uneducated, and marginal are inserted in risk profiles both as potential violators of migration laws, and as probable “victims” of “marriage of convenience” abusers. The stories shared by women with first-hand experience of transnational marriages will be used to inquire as to whether these claims may provide a smokescreen for restrictive migration policies. I will then move on to discuss the outcomes of the current migration regime in terms of dependency, gendered violence and missed opportunities among the involved couples. In this sense, the research results will exemplify, on the basis of interviewees’ accounts, how policies are not living up to their alleged objectives, but rather are reproducing social inequalities. The discussion will thus be rooted in the acknowledgement of how intersectional factors (Crenshaw 1989, Hooks 2015 [1981], Yuval Davis 2011, Stolke 2003) influence the selection of applicants and determine residency outcomes, often regardless of the couples’ motivations and trajectories. I will suggest that the scope of the final reflections may be extended towards the society in which these specific bordering dynamics are embedded, reinforcing its gendered, class-based, material and symbolic power relations, concealed behind paternalistic formulas.

CHAPTER I

METHODOLOGY

Foreigness does not start at the water’s edge, but at the skin’s Clifford Geertz, 1996

The research process has been an occasion to face a series of methodological

constraints, provoking a deep reflection on the epistemological stances involved in social research. One of the pillars of the analysis presented in this dissertation is a perspective considering borders not only as material and territorial signs of delimitation, but also as imaginary lines shaping social relations at various levels simultaneously (cf. Van Houtum et al. 2002). My starting point is the idea that academic production also plays a role in bordering, since it inevitably involves both classification efforts and their problematization, contributing to particular configurations of social order. The border, in all its connotations, is thus considered a fertile analytical space to inquire into social relations, while also exposing contradictions and gaps in our forms of knowledge production. As Henk Van Houtum comments in his reflections on bordering, “it is precisely in the unfamiliarity of this in-between and beyond-space that we are challenged to unbound our thinking and practices” (Van Houtum 2005:3).This chapter will be an opportunity to explore the underpinnings of the various methodological tools I have employed. The structure of the text reflects the constant search for equilibrium between on one hand the methods considered most effective, feasible, or commonly used in the given academic context, and on the other hand epistemological issues and ethical concerns that can arise from the use of these methods. After a short introduction tracing the genesis of the research and its scope, the chapter will be divided into two sections, in which I will describe the project’s development.

The first section will debate the epistemological premises and research devices chosen to investigate the theme of conjugality and human mobility, discussing the main issues encountered in the course of the study. Firstly, I will approach the theme of reflexivity and situated gaze, based on the acknowledgment of my social position as a researcher. Secondly, I will describe how I dealt with the challenge of producing validated scientific knowledge, while at the same time renouncing pretensions of “truth” and universality with regard to concepts, categories, and the interpretation of data. Thirdly, the evolving definition of the object of study will be presented as a consequence of the epistemological positioning. Lastly, I will share some reflections on the balancing of structure and agency that I have attempted to maintain in my analysis of social relations.