ww w . r e u m a t o l o g i a . c o m . b r

REVISTA

BRASILEIRA

DE

REUMATOLOGIA

Original

article

Ozone

decreases

sperm

quality

in

systemic

lupus

erythematosus

patients

Juliana

Farhat

a,

Sylvia

Costa

Lima

Farhat

a,

Alfésio

Luís

Ferreira

Braga

a,b,

Marcello

Cocuzza

c,

Eduardo

Ferreira

Borba

d,

Eloisa

Bonfá

d,

Clovis

Artur

Silva

d,e,∗ aGroupofEnvironmentalEpidemiologyStudies,LaboratoryofExperimentalAirPollution,FacultyofMedicine,UniversidadedeSãoPaulo,SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

bGroupofEnvironmentalExposureandRiskAssessmentStudies,Post-GraduatePrograminPublicHealth,UniversidadeCatólicade

Santos,Santos,SP,Brazil

cDivisionofUrology,FacultyofMedicine,UniversidadedeSãoPaulo,SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil dDivisionofRheumatology,FacultyofMedicine,UniversidadedeSãoPaulo,SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

eUnitofPediatricRheumatology,InstitutodaCrianc¸a,FacultyofMedicine,UniversidadedeSãoPaulo,SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received3November2014

Accepted6July2015

Availableonline23November2015

Keywords:

Systemiclupuserythematosus

Airpollution

Spermquality

Fertility

Cyclophosphamide

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Objective:ToinvestigatethedeleteriouseffectsofairpollutantsexposureintheSaoPaulo

metropolitanregiononsemenqualityinsystemiclupuserythematosus(SLE).

Methods:Aseven-yearslongitudinalrepeated-measurespanelstudywasperformedatthe

LaboratoryofExperimentalAirPollutionandRheumatologyDivision.Twosemensamples

from28post-pubertalSLEpatientswereanalyzed.Dailyconcentrationsofairpollutants

exposure:PM10,SO2,NO2,ozone,CO,andmeteorologicalvariableswereevaluatedon90

daysbeforeeachsemencollectiondatesusinggeneralizedestimatingequationmodels.

Results:Intravenous cyclophosphamide (IVCYC) and ozone had an association with a

decreaseinspermqualityofSLEpatients.IVCYCwasassociatedwithdecreasesof64.3

millionofspermatozoa/mL(95%CI39.01–89.65;p=0.0001)and149.14millionof

spermato-zoa/ejaculate(95%CI81.93–216.38;p=0.017).Withregardtoozone,themostrelevantadverse

effectswereobservedfromlags80–88,whentheexposuretoaninterquartilerangeincrease

inozone9-daymovingaverageconcentrationledtodecreasesof22.9millionof

spermato-zoa/mL (95% CI 5.8–40.0; p=0.009) and 70.5 million of spermatozoa/ejaculate (95% CI

12.3–128.7;p=0.016).Furtheranalysisof17patientsthatneverusedIVCYCshowed

associa-tionbetweenexposuretoozone(80–88days)anddecreaseof30.0millionofspermatozoa/mL

(95%CI 7.0–53.0;p=0.011)and79.0 millionofspermatozoa/ejaculate (95% CI 2.1–155.9;

p=0.044).

Conclusion:Ozoneand IVCYChad a consistent adverse effecton semenqualityof SLE

patientsduringspermatogenesis.Minimizingexposuretoairpollutionshouldbetakeninto

account,especiallyforpatientswithchronicsystemicinflammatorydiseaseslivinginlarge

cities.

©2015ElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrightsreserved.

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:clovis.silva@hc.fm.usp.br(C.A.Silva).

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbre.2015.08.005

O

ozônio

diminui

a

qualidade

do

sêmen

em

pacientes

com

lúpus

eritematoso

sistêmico

Palavras-chave:

Lúpuseritematososistêmico

Poluic¸ãodoar

Qualidadedosêmen

Fertilidade Ciclofosfamida

r

e

s

u

m

o

Objetivo: Investigar os efeitosdeletérios da exposic¸ão aospoluentes do ar na Região

MetropolitanadeSãoPaulosobreaqualidadedosêmendepacientescomlúpuseritematoso

sistêmico(LES).

Métodos: Foifeitoumestudolongitudinaldepainelcommedidasrepetidasdeseteanosno

LaboratóriodePoluic¸ãoAtmosféricaExperimentaleReumatologia.Foramanalisadasduas

amostrasdesêmende28pacientescomLESpós-púberes.Foramavaliadasasconcentrac¸ões

diáriasdeexposic¸ãoaospoluentesdoarPM10,SO2,NO2,ozônioeCOevariáveis

meteo-rológicas90diasantesdecadadatadecoletadesêmencomousodométododeequac¸ões

deestimativasgeneralizadas.

Resultados: Aciclofosfamidaintravenosa(CICIV)eoozônioestiveramassociadosauma

diminuic¸ãonaqualidadedosêmendospacientescomLES.ACICIVesteveassociadaaum

decréscimode64,3milhõesdeespermatozoides/mL(IC95%39,01-89,65;p=0,0001)e149,14

milhõesdeespermatozoides/ejaculado(IC95%81,93-216,38;p=0,017).Emrelac¸ãoaoozônio,

osefeitosadversosmaisrelevantesforamobservadosentreoslags(intervalodetempo)80

e88,quandoaexposic¸ãoaumaconcentrac¸ãomédiadeozônioumintervalointerquartil

maioremnovediasmóveislevouaumdecréscimode22,9milhõesdeespermatozoides/mL

(IC95%5,8-40;p=0,009)e70,5milhõesdeespermatozoides/ejaculado(IC95%12,3-128,7;

p=0,016).Umaanálisemaisaprofundadados17pacientesquenuncausaramCICIVmostrou

associac¸ãoentreaexposic¸ãoaoozônio(80-88dias)eodecréscimode30milhõesde

esper-matozoides/mL(IC95%7-53;p=0,011)e79milhõesdeespermatozoides/ejaculado(IC95%

2,1-155,9;p=0,044).

Conclusão: OozônioeaCICIVtiveramumefeitoadversoconsistentesobreaqualidadedo

sêmendepacientescomLESduranteaespermatogênese.Deve-seconsideraraminimizac¸ão

daexposic¸ãoàpoluic¸ãodoar,especialmenteparapacientescomdoenc¸asinflamatórias

sistêmicascrônicasquevivemnasgrandescidades.

©2015ElsevierEditoraLtda.Todososdireitosreservados.

Introduction

Gonad function is severely affected in male SLE patients.

Recently,severespermabnormalitieswithtesticularatrophy,

high follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels and

testi-cular Sertoli cell dysfunction associated with intravenous

cyclophosphamide(IVCYC)treatmentwere reported byour

groupinsystemiclupuserythematosus(SLE).1–3

Exposuretoairpollutantshasalsobeencorrelated with

male reproductive outcomes, especially sperm quality,4–9

howeverthisenvironmentalfactorwasnotstudiedinmale

SLEpopulationwithgonadalfunctionassessment.

Infact,airpollutioniscomposedofaheterogeneous

mix-tureofgasesandparticlesthatincludeozone(O3),particulate

matter(PM10), nitrates (NO), sulfur dioxide (SO2), toxic

by-product oftobacco smoke and carbon monoxide (CO) and

may trigger systemic inflammation and autoimmunity in

SLE.10,11

Therefore, theobjective ofthis study wastoinvestigate

prospectivelythecorrelationofairpollutantsexposure

con-centrations and semen quality in Sao Paulo metropolitan

regioninSLEpatients.

Material

and

methods

Alongitudinalrepeated-measurespanelstudywasperformed

with35nonsmokerspost-pubertalmaleSLEpatientsregularly

followedatthePediatricRheumatologyUnitandtheLupus

Clinics ofthe Rheumatology Division. All patients fulfilled

the American CollegeofRheumatology classification

crite-riaforSLE.12 None ofthemhad cryptorchidism, hydrocele,

hypospadia,testicular infection (e.g.,mumps),orchitis,

tes-ticularvasculitis,testicularcancer,ureteralimpairmentand

previoushistoryofanyscrotaloringuinalsurgery(e.g.,

varic-ocelectomy,vasectomyandherniarepair).NineSLEpatients

wereexcludedsincetheydidnotresidewithinthe

metropoli-tanregionofthecityofSaoPaulo,presentedazoospermiaor

hadonlyonesampleofspermcollected.Therefore,from

Jan-uary2000toJanuary2006,26SLEpatientsresidentofSaoPaulo

metropolitanregionperformedaglobalreproductivehealth

evaluationincludingtwospermsamplesofeachpatientwith

amedianintervalof1month(range0.7–8months).

TheEthicsCommitteeofourUniversityHospitalapproved

this study and aninformed consentwas obtainedfrom all

Globalreproductivehealthevaluation

Demographicdataandlifestylehabits:Currentage,disease

duration,yearsofeducation,smokingandalcohol

consump-tionwererecorded.

Urological evaluationandtesticular doppler ultrasound:

A clinical examination of the genitalia included

evalua-tion of testicles, epididymis, vas deferens, scrotum and

penis was performed blinded to the semen analysis. The

patientswere examined inawarm room(temperature not

inferior to 22◦C), with and without Valsalva manoeuver

and in both the standing and supine positions to assess

clinical varicocele.13,14 Testicular volumes were measured

using the Prader orchidometer. Testicular ultrasound was

performed in all SLE patients by an expert sonographer

blindedtothesemenanalysistoassessradiographic

varic-ocele and testicular volumes. Thelargest measurement in

each dimension was recorded and used to calculate the

testicular volume according to the formula to an ellipsoid

(length×width×thickness×0.52).Thenormalmeanvaluein

malepost-pubertaladolescentsandadultsis15±8mL.15Low

testicularvolumewasdefinedifaSLEpatienthadareduced

testicularvolumebyPrader’sorchidometerand/orultrasound.

VaricocelewasdefinedifaSLEpatienthadpresented

clini-calorradiographicenlargementofthepampiniformvenous

plexusinthescrotum.13

Semen analysis and anti-sperm antibodies: Fifty-two

spermanalysiswereperformedbytwoexpertmedical

tech-nologistswhowereblindedtotheotherparameters.Sperm

volume,concentration,totalspermcount(totalspermatozoa

per ejaculate), progressivemotility were carried out based

onguidelinesoftheWorldHealthOrganization(WHO).16All

patientscollectedatleasttwosemensamples(median

inter-valof1month,range0.7–8months)after48–72hofsexual

abstinence.Thespermatozoawereanalyzedbymanualhand

countaswellasbyacomputer-assistedsemenanalysis

sys-temunder400×magnification,usinganHTM-2030.Eachslide

wasscannedtoestimatethenumberofspermatozoaperfield

equivalentto1mL,toobtainanapproximatesperm

concen-tration in millions of spermatozoa per mL of semen. The

motilityofeachspermatozoawasgraded‘a’(rapidprogressive

motility),‘b’(sloworsluggishprogressivemotility),‘c’

(non-progressivemotility)and‘d’(nomotility).17Thepresenceof

antispermantibodieswasdeterminedbydirectImmunobead

test using ImmunobeadR rabbit anti-human Ig (IgA, IgG,

and IgM) kits (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA, USA)in all

patients.

Hormonal status: Hormone determinations were

per-formed atstudy entry blinded to the other parameters of

gonadalfunction:FSH(normalvalue:1–10.5IU/L)andmorning

totaltestosterone(271–965ng/dL)weredetectedby

fluoroim-munoassayusingDELFIAtime-resolvedfluoroimmunoassay

kits(Wallac,Turku,Finland).Intra-andinter-assaycoefficients

of variation were limited to 3.5% and 2.1%, respectively.

Inhibin B levels [normal value: 74–470pg/mL (12–17 years

old)and 60–300pg/mL(18–50 yearsold)] weremeasured by

enzymatically amplified, two-site, two-step, sandwich-type

immunoassay(DiagnosticSystemsLaboratories,Inc.,Webster,

TX,USA).Intra-andinter-assaycoefficientsofvariationwere

limited to 3.5–5.6% and 6.2–7.6%, respectively. Gonadal

hormonal abnormality was considered if the testosterone

and/orinhibinBserumlevelswerereducedortheFSHserum

levelswereincreased.

Clinicalevaluationandtreatment

SLEdisease activity andcumulativedamageatthetimeof

study entry were measured in all patients, using the SLE

Disease Activity Index (SLEDAI)18 and the Systemic Lupus

InternationalCollaboratingClinics/ACR(SLICC/ACR)Damage

Index.19Dataconcerningthetherapyweredetermined.

Airqualityandmeteorologicaldata

Dailyrecordsofstudiedpollutants,includingO3(thehighest

hourlyaverage),SO2(24-haverage),NO2(thehighesthourly

average),PM10 (24-haverage)andCO(thehighest8-h

mov-ingaverage),wereobtainedfortheentirestudyperiodfrom

the Sao Paulo StateEnvironmental Agency (CETESB) by 13

automatic monitoringstation spread aroundthe city.PM10

concentration (betaradiation – FH62lNGraseby Andersen)

was measured in12 ofthese stations. The highest hourly

averageofO3(ultraviolet–ThermoE.I.I-Model49)and NO2

(chemiluminescence–ThermoE.I.I-Model42)wasmeasured

atfour stations.Thehighest8hmovingaveragewas

mea-suredatfivestationsforCO(non-dispersiveinfrared–Thermo

E.I.I-Model48)andat13stationsforSO2(pulse

fluorescence-ultraviolet – Thermo E.I.I-Model 43).20 All pollutants were

measured from 00:01 AM to 12:00 PM. The average of all

stations that measured each pollutant was adopted as an

exposurestatusthroughoutthecity,sinceairpollutantslevels

recordedineachstationwerehighlycorrelatedwiththe

oth-ers.Thedailyminimumtemperatureandmean relativeair

humiditywereobtainedfromtheInstituteofAstronomyand

GeophysicsattheUniversityofSãoPaulo.Pollutants’

concen-trationandmeteorologicalvariableswereevaluateddailyon

90daysbeforesemencollectiondates.

Statisticalanalysis

We usedthe generalized estimatingequation model (GEE),

consideringfixedeffectsforrepeatedmeasurementsto

esti-mate the association and effect of pollutants on sperm

concentration, sperm count and sperm progressive

motil-ity. S-Plus 2000 Professional Release 3 software (MathSoft

Inc.,Seattle, WA, USA)wasemployed,adjustingthe model

for the independent variables by way of an exchangeable

correlation asaworkingmatrix,whichassumes equal

cor-relation formeasurementsineach subject. Thedependent

variablesweredefinedbasedonthefifthpercentileofthe

ref-erencelimitsofWHOguidelines forsperm analysis:sperm

concentration (minimum value 15 million per mL), total

sperm count(minimumvalue39 millionperejaculate)and

spermprogressivemotility(sumofpercentageof“a”,“b”of

spermatozoamotility–minimumvalue32%).Theregressions

were adjustedforindependentvariables:current age,years

ofeducation,smoking,alcoholconsumption,timeofsexual

abstinence, reduced testicular volume, presence of

Table1–Demographicdata,diseaseactivity,hormoneevaluation,urologicalevaluation,spermanalysisandtreatmentof malesystemiclupuserythematosus(SLE)patients.

Characteristics Referencevalues Patientvalues WithoutIVCYCuse WithIVCYCuse p

(n=26) (n=17) (n=9)

Demographicdata

Ageatstudyentry,years 29.8(8.9) 29.5(2.1) 30.4(3.2) 0.8

AgeatSLEonset,years;mean(SD) 20.4(9.6) 20.3(10.4) 19.7(8.5) 0.8

Ageatspermarche,years;mean(SD) 12.9(1.0) 12.9(1.2) 12.78(0.6) 0.7

Diseaseduration,years;mean(SD) 9.3(6.5) 8.7(6.9) 10.6(5.8) 0.5

Educationallevel,years;mean(SD) 10.0(3.3) 10.1(2.9) 9.8(3.0) 0.8

Smoking,n(%) 4(15) 4(28.6) 0(0) 0.3

Alcoholconsumption,n(%) 8(31) 5(29.4) 3(33.3) 0.5

SLEDAIscores,n(%)

>4 5(19.2) 3(17.6) 2(22.2) 0.46

>8 3(11.5) 1(5.9) 2(22.2)

Hormoneevaluation

Folliclestimulatinghormone,IU/liter;mean(SD) 7.6(5.8) 6.3(5.9) 10.0(5.2) 0.16

Elevatedlevels;n(%) 7(26.7) 3(17.6) 4(44.4) 0.34

InhibinB,pg/mL;mean(SD) 125.5(78.0) 138.8(73.6)

3(17.6)

97.3(84.5) 0.22

Decreasedlevels;n(%) 7(26.7) 500.5(264.8)

2(11.8)

4(44.4) 0.34

Totaltestosterone,ng/dl;mean(SD) 526.3(243.3) 576.8(201.2) 0.5

Decreasedlevels;n(%) 2(7.7) 0(0) 0.5

Intravenouscyclophosphamide(IVCYC)use 0

Currentuse;n(%) 9(34.6)

Previoususe;n(%) 8.5(12.01)

Cumulativedose(g);(mean/SD) 9(34.6)

Numberofpulsetherapy;n(%) 1.69(1.47)

Durationoftreatment;(meanyears/SD)

Othersdrugsthatalterspermqualityn(%) 10(38.5) 5(29.4) 5(55.6) 0.2

Urologicalevaluationtesticular

Reducedvolume(clinicalandUS);n(%) 7(26.9) 5(29.4) 2(22.2) 0.4

Clinicalorradiographicvaricocele;n(%) 11(42.3) 7(41.2) 4(44.4) 1.0

Spermanalysis WHO2010

Sexualabstinence,days;(median/IQR) ≥2 3(2.5)

Spermvolume,mL;(mean/SD) ≥1.5 2.3(1.2) 2.1(0.9) 2.9(1.5) 0.1

SpermpH;(mean/SD) ≥7.2 7.6(0.3) 7.6(0.3) 7.6(0.3) 1.0

Spermconcentration,×106/mL;(mean/SD) >15 63.2(72.0) 86.3(77.8) 19.6(28.7) 0.02 Totalspermcount,×106perejaculate(mean/SD) >39 147.3(223.2) 209.9(302.4) 46.1(55.6) 0.1

Progressivemotility,%;(mean/SD) >32 53.0(23.0) 57.6(17.7) 47.0(26.4) 0.2

Antispermantibodies,%;(mean/SD) <20 29.0(14.4) 29.3(14.8) 28.8(14.7) 0.9

Resultsarepresentedinn(%),mean±standarddeviationormedian(interquartilerange).

antibodies,SLEdiseaseactivityandcumulativedamage, pred-nisone use, immunosuppressive use (IVCYC, azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil and methotrexate), use of others medicationsthatalterspermquality (angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, spironolactone, cimetidine, haloperidol, carbamazepineand thalidomide),and factors regarding air pollutants: temperature, relative humidity and daily con-centrationofthe pollutants. Thelag structurebetween air pollutantexposureandthedependentvariableswasassessed usinglagsof0–90daysandmovingaveragesof2,8,and 9 daysforpollutantsthatwasstatisticallysignificant on sin-gle models. For instance, a 2 day moving average is the mean of the pollutants levels in the concurrent and pre-vious day assigned for the concurrent day. Changes were analyzed,mainly,inrespecttospecificperiodsof spermato-zoa development,which correspondtoepididymalstorage,

development ofsperm motility and total duration of sper-matogenesis (0–9, 10–14 and 70–90 days before collection, respectively).21,22 Single-pollutantmodelswereusedforthe

analysis.However,ifmorethanonepollutanthada

signifi-canteffectontheoutcomethentwo-pollutantmodelswere

adopted.Pearsoncorrelationcoefficientswereestimatedfor

airpollutantvariables.Effectswerereportedasdecreasesin

theoutcomes[withtherespective95%confidenceinterval(CI)]

foraninterquartilerange(IQR)increaseineachpollutant.

Results

Demographicdata,diseaseactivity,hormoneevaluation,

uro-logicalevaluation,spermanalysisandtreatmentofmaleSLE

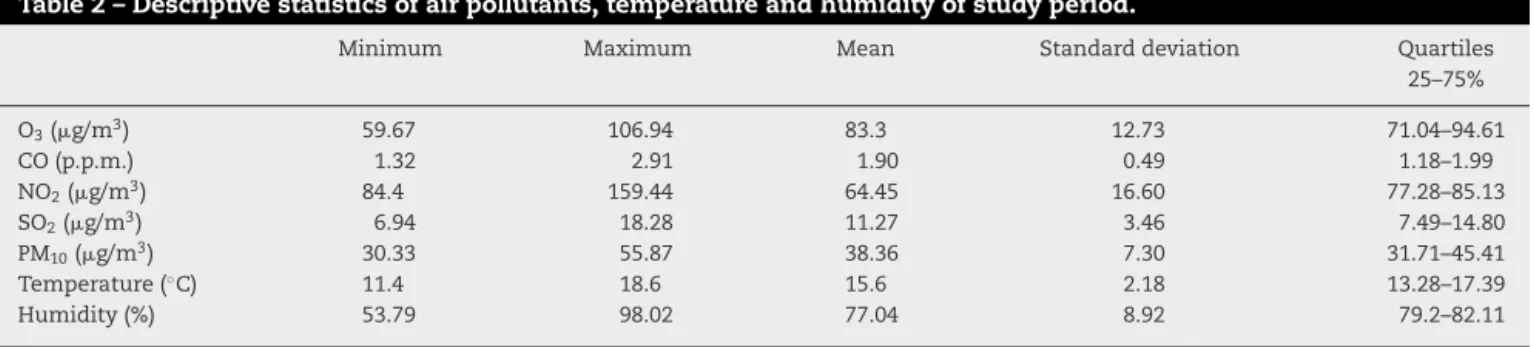

Table2–Descriptivestatisticsofairpollutants,temperatureandhumidityofstudyperiod.

Minimum Maximum Mean Standarddeviation Quartiles

25–75%

O3(g/m3) 59.67 106.94 83.3 12.73 71.04–94.61

CO(p.p.m.) 1.32 2.91 1.90 0.49 1.18–1.99

NO2(g/m3) 84.4 159.44 64.45 16.60 77.28–85.13

SO2(g/m3) 6.94 18.28 11.27 3.46 7.49–14.80

PM10(g/m3) 30.33 55.87 38.36 7.30 31.71–45.41

Temperature(◦C) 11.4 18.6 15.6 2.18 13.28–17.39

Humidity(%) 53.79 98.02 77.04 8.92 79.2–82.11

O3,ozone;CO,carbonmonoxide;NO2,nitrogendioxide;SO2,sulfurdioxide;PM10,particulatematter.

corticosteroids and chloroquine diphosphate treatment beforepuberty.Themeantimeintervalbetweenthelastdose ofIVCYCandspermcollectionwas5.4±3.7years.

SpermevaluationsofSLEpatientsshowedthatthemedian ofsexualabstinence,meansofspermvolume,pH,sperm con-centration,totalspermcountandspermprogressivemotility valueswereattheparametersregardedaspercentile5%by WHOguidelines(Table1).

Thehumidityandthetemperatureandtherangeof

vari-ation in pollutant concentrations and weather conditions

duringtheassessedperiodarepresentedinTable2.Noneof

thepollutantsurpassedtheBraziliannationalstandardsfor

airqualitylimitsinthestudiedperiod.

Primary airpollutants were highlycorrelated witheach

other,withPearson’scoefficientsvaryingfrom0.48(SO2and

NO2)to0.77(PM10andCO)p<0.001andp<0.001respectively.

Ozone’slowest Pearson’scoefficient wasobserved withCO

(0.28), and ozone’s highest coefficient was with NO2 (0.60)

p=0.04and p<0.001 respectively.SinceNO2measurements

wereperformedonadailybasis,onthosedayswithhighNO2

concentrations,therewasahighformationofthesecondary

pollutantasozone.

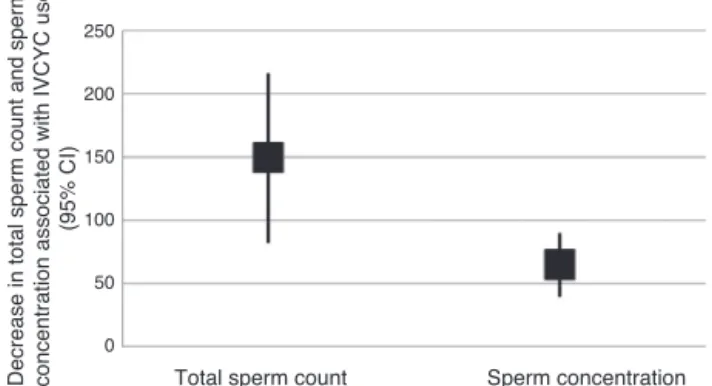

Intheregressionmodels,onlyIVCYCuseandozonehad

anassociationwithdecreaseinspermquality.

IVCYCusewasassociatedwithdecreasesinsperm

con-centration (64.3million/mL; 95% CI,39.01–89.65; p=0.0001),

total sperm count (149.14 million per ejaculate; 95%

CI, 81.93–216.38; p=0.017) and progressive sperm motility

(20.94%;95%CI,4.75–37.05;p=0.001)intheevaluatedperiods

(Table3).

Withregard toozone,anincrease ofinterquartile range

(IQR)of23.57g/m3inthispollutantaveragedoverthe0–90

dayperiodwasassociatedwithadecreaseof30.6millionof

spermatozoa/mL (95%CI, 2.0–59.3; p=0.040)in sperm.The

specific analysis of daily exposure to ozone revealed that

the critical periodwas 80–88days beforethe dateof

sam-plecollectionwithacumulativedecrease of22.9 millionof

spermatozoa/mL(95%CI,5.8–40.0;p=0.009)and70.5million

ofspermatozoa/ejaculate(95%CI,12.3–128.7;p=0.016)

asso-ciated withozone cumulativeeffectexposure toanIQRof

23.57g/m3(Fig.1).Noeffectswereobservedwiththeothers

pollutantsonspermconcentrationortotalcount.

Nopollutants’effectsonprogressivespermmotilitywere

observedinthetwoweeksafterexposure(periodofmotility

Table3–Decreaseintotalspermcountandspermconcentrationassociatedwithexposuretoozone80–90daysbefore thedateofspermsamplecollect.

Decrease(95%CIa)O

3(IQRb=23.57g/m3)

Totalspermcount(millionperejaculate) Spermconcentration(millionpermL)

Decrease (95%CI)a Decrease (95%CI)a

Lag80 21.3 (4.8;37.8)c 5.1 (0.2;10.0)e

Lag81 21 (7.8;34.1)d 2.8 (−1.4;7.1)

Lag82 3 (−18.7;24.8) 1.6 (−10.3;7.1)

Lag83 8.9 (−10.9;28.8) 2 (−4.0;7.9)

Lag84 5.2 (−30.2;19.8) 2.9 (−10.7;4.9)

Lag85 13.8 (−16.3;43.9) 3.4 (−6.7;13.6)

Lag86 26.8 (4.3;49.4)c 6.1 (−1.24;13.4)

Lag87 12.6 (−3.6;28.7) 4.1 (−0.8;9.0)

Lag88 9.9 (−7.72;27.5) 5.1 (0.2;9.9)

9daymovingaverage(80–88) 70.5 (12.3;128.7)c 22.9 (5.8;40.0)e

Lagn=ndaysafterexposure. a Confidenceinterval. b Interquartilerange. c p=0.01.

Total sperm count Sperm concentration

Decrease in total sperm count and sperm concentration associated with IVCYC use

(95% CI)

250

200

150

100

50

0

Fig.1–Effectsofintravenouscyclophosphamideonsemen quality.

development),but wefound anegativeeffectin weekssix

andsevenafterexposuretoozone(fromlag31tolag38).The

eight-daycumulativeeffectofexposuretoanIQRincreaseof

23.57g/m3inozonewasassociatedwith5.7%decrease(95%

CI,0.6–10.7;p=0.023)intheprogressivespermmotility.

Further analysis of 17 patients that never used IVCYC

showednine-daycumulativeeffect(80–88days)ofexposureto

anIQRincreaseinozonewasassociatedwithadecreaseof30.0

millionofspermatozoa/mL(95%CI,7.0–53.0;p=0.011),79.0

millionofspermatozoa/ejaculate(95%CI,2.1–155.9;p=0.044).

Theeight-daycumulativeeffect(31–38days)wasassociated

withadecreaseof6.6%(95%CI,2.9–10.3;p=0.001)inthe

pro-gressivespermmotility.

No statistically significant associations were found

betweenotherpollutants andother dependentvariables at

thespecificperiodsofspermatozoadevelopment.

Discussion

Toourknowledge,thiswasthefirststudytoidentifythelag

structureeffectsofexposuretotroposphericpollutiononthe

spermqualityinSLEpatients.TheozoneandIVCYChad

sig-nificantdeleteriouseffectonspermatogenesis.

Themainstrength ofthe presentstudy wasacomplete

assessment of gonadal parameters in post-pubertal lupus

patientsandanevaluationofairpollutantsinametropolitan

areaofalargecity.Inaddition,thestudydesignof

repeated-measures of sperm analysis had advantages to require a

smallernumberofindividualsthanacompletelyrandomized

studyanditprovidesmoresuitableconditionsofco-variables

thatmayinfluencethespermquality,withouttheneedofa

healthycontrolgroupevaluation.23Moreover,theanalysisofa

subgrouppatientnotexposedtoIVCYC,aknowngonadotoxic

treatment,allowedamoreaccuratedefinitionofozonesperm

harmful effect. The main limitations of the present study

werethesmallsamplesize,particularlyinthoseSLEpatients

thatwerepreviouslyexposedtocyclophosphamide,andthe

factthat fixedmonitoring stationsdid notfully reflectthe

individualvariationinexposuretopollutants.Inaddition,the

cityofSãoPaulohasapopulationof10,886,518peoplewith

morethan 6million vehicles. This automotive fleetis the

mainsourceofairpollutionanditisobservedthattheozone

concentration has progressively increased.20 Airpollutants

levels recorded in the stations in São Paulo were highly

correlatedwitheachotherandevenozonepresentedpositive

statistically significant correlations to primary pollutants

asobservedinthisstudy.Thelackofeffectofothers

pollu-tantsonspermqualitymayresultfromthehighcorrelation

amongairpollutantsobservedherein.Infact,eachanalyzed

pollutantcanbeconsideredagoodindependentmarkerfor

complexmixtureofairpollution.Inthisway,itispossibleto

assumethattheeffectsonthesemenqualitywereduetothe

actionofallcriteriaairpollutants.

Airpollutionconsistsofaheterogeneousmixtureofgases

and particles that includeO3. Oxidativestress and

inflam-mation induced bythis pollutantmay result inrespiratory

disorders,24–26 as well as contribute to a stateof systemic

inflammation27,28andautoimmunity.10

Additionally,ozonecaninducetesticularoxidativestress

and excessive generation of freeradicals thatcan provoke

damageon maturespermatozoa and germ cells apoptosis,

resultinginreducedspermconcentrationandmotility,29as

observedherein.Inthisregard,Sokoletal.8observedan

asso-ciation between spermquality and exposureto ozone and

Hansenetal.9reportedthesameassociationwithincreaseof

PM2.5.Airpollutionmayalsoinfluencemalefertility7–9dueto

endocrinedisruption,spermDNAdamageandtoxicity

medi-atedbythearylhydrocarbonreceptor.30,31

Interestingly,exposuretoairpollutantsmayaffectgerm

celldevelopmentincludingtheentireperiod(90days)or

spe-cificperiodsofspermdevelopmentbeforesamplecollection

(epididymal storageor developmentof sperm motility).4,8,9

Hammoudetal.4foundthatairpollutionleadtoadecreasedin

progressivemotilityaftermorethan4weeksoftheexposure.

Indeed,thespermmotilityisalateeventin

spermatogene-sisandduringepididymistransit,thespermatozoaundergo

changes in morphology, chemistry and motility. Ourstudy

suggestedthatexposuretopollutantcouldbedeleteriousfor

progressivemotility inSLEpatients, evenbeforethe sperm

reachtheepididymis(0–14daysbeforesemencollecting).

Moreover,weconfirmedandextendedthroughacomplex

statisticalmodelthatIVCYCwasanimportantcauseofinjury

tospermatogenesis1–3,13,14,32–37emphasizingtherelevanceof

cryopreservationofsemenforpost-pubertalmalesinorderto

guaranteethepossibilityofreproductionafterthis

immuno-suppressivetherapy.38,39

Inconclusion,ozoneandtheuseofIVCYChadaconsistent

adverseeffectonsemenqualityofSLEpatients.Wefurther

identifiedthatthisabnormalityisnotrestrictedtoearly

sper-matogenesis but alsooccurs in later stages. Consequently,

minimizing exposureto airpollution should be takeninto

account,especiallyforpatientsresidinginlargecities.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from Conselho

NacionaldeDesenvolvimentoCientíficoeTecnológico(CNPq

de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP

2004/07832-2toCAS,2005/56482-7toCASand 2008/58238-4

toCAS),FedericoFoundation(toCASandEB)andbyNúcleo

deApoioàPesquisa“SaúdedaCrianc¸aedoAdolescente”da

USP(NAP-CriAd)toCAS.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1. SoaresPM,BorbaEF,BonfaE,HallakJ,CorreaAL,SilvaCA. Gonadevaluationinmalesystemiclupuserythematosus. ArthritisRheum.2007;56:2352–61.

2. SuehiroRM,BorbaEF,BonfaE,OkayTS,CocuzzaM,Soares PM,etal.TesticularSertolicellfunctioninmalesystemic lupuserythematosus.Rheumatology.2008;47:1692–7. 3. VecchiAP,BorbaEF,BonfáE,CocuzzaM,PieriP,KimCA,etal.

Penileanthropometryinsystemiclupuserythematosus patients.Lupus.2011;20:512–8.

4. HammoudA,CarrellDT,GibsonM,SandersonM,Parker-Jones K,PetersonCM.Decreasedspermmotilityisassociatedwith airpollutioninSaltLakeCity.FertilSteril.2010;93:1875–9. 5. SelevanSG,BorkovecL,SlottVL,ZudováZ,RubesJ,Evenson

DP,etal.Semenqualityandreproductivehealthofyoung Czechmenexposedtoseasonalairpollution.EnvironHealth Perspect.2000;108:887–94.

6. GuvenA,KayikciA,CamK,ArbakP,BalbayO,CamM. Alterationsinsemenparametersoftollcollectorsworkingat motorways:doesdieselexposureinducedetrimentaleffects onsemen?Andrologia.2008;40:346–51.

7. RubesJ,SelevanSG,EvensonDP,ZudovaD,VozdovaM, ZudovaZ,etal.Episodicairpollutionisassociatedwith increasedDNAfragmentationinhumanspermwithoutother changesinsemenquality.HumReprod.2005;20:2776–83. 8. SokolRZ,KraftP,FowlerIM,MametR,KimE,BerhaneKT.

Exposuretoenvironmentalozonealterssemenquality. EnvironHealthPerspect.2006;114:360–5.

9. HansenC,LubenTJ,SacksJD,OlshanA,JeffayS,StraderL, etal.Theeffectofambientairpollutiononspermquality. EnvironHealthPerspect.2010;118:203–9.

10.FarhatSC,SilvaCA,OrioneMA,CamposLM,SallumAM, BragaAL.Airpollutioninautoimmunerheumaticdiseases:a review.AutoimmunRev.2011;11:14–21.

11.VidottoJP,PereiraLA,BragaAL,SilvaCA,SallumAM,Campos LM,etal.Atmosphericpollution:influenceonhospital admissionsinpaediatricrheumaticdiseases.Lupus. 2012;21:526–33.

12.HochbergMC.UpdatingtheAmericanCollegeof Rheumatologyrevisedcriteriafortheclassificationof systemiclupuserythematosus.ArthritisRheum. 1997;40:1725.

13.NukumizuLA,Gonc¸alvesSaadC,OstensenM,AlmeidaBP, CocuzzaM,Gonc¸alvesC,etal.Gonadalfunctioninmale patientswithankylosingspondylitis.ScandJRheumatol. 2012;41:476–81.

14.AlmeidaBP,SaadCG,SouzaFH,MoraesJC,NukumizuLA, VianaVS,etal.TesticularSertolicellfunctioninankylosing spondylitis.ClinRheumatol.2013;32:1075–9.

15.ColliAS,BerquioES,MarquesRM.Crescimentoe desenvolvimentopubertárioemcrianc¸aseadolescentes brasileiros.In:ColliAS,BerquioES,MarquesRM,editors. Volumetesticular.1sted.SãoPaulo:BrasileiradeCiências Ltda;1984.p.1–34.

16.CooperTG,NoonanE,vonEckardsteinS,AugerJ,BakerHW, BehreHM,etal.WorldHealthOrganizationreferencevalues forhumansemencharacteristics.HumReprodUpdate. 2010;16:231–45.

17.RowePJ,ComhaireFH,HargreaveTB,MahmoudAM.World HealthOrganization(WHO)forthestandardized

investigation,diagnosisandmanagementoftheinfertile men.Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress;2000. 18.BombardierC,GladmanD,UrowitzMB,KaronD,ChangCH.

TheCommitteeonPrognosisStudiesinSLE.Derivationofthe SLEDAI:adiseaseactivityindexforlupuspatients.Arthritis Rheum.1992;35:630–40.

19.GladmanD,GinzlerE,GoldsmithC,FortinP,LiangM,Urowitz M,etal.Thedevelopmentandinitialvalidationofthe systemiclupusinternationalcollaboratingclinics/American CollegeofRheumatologydamageindexforsystemiclupus erythematosus.ArthritisRheum.1996;39:363–9.

20.CETESB.Availableat:http://www.cetesb.sp.gov.br/Ar/

arautomatica.asp[accessed10.06.13].

21.JohnsonL,WelschTHJr,WilkerCE.Anatomyandphysiology ofthemalereproductivesystemandpotentialtargetsof toxicants.In:SipesIG,McQueenCA,GandolfiAJ,editors. Comprehensivetoxicology.NewYork:Pergamon;1997.p. 5–98.

22.RobaireB,HermoL.Efferentducts,epididymisandvas deferens.In:KnobilE,NiellJ,editors.Physiologyof reproduction.3rded.NewYork:RavenPress;1994.p. 999–1000.

23.AndreßHJ,GolschK,SchmidtAW.Appliedpaneldata analysisforeconomicandsocialsurveys.1sted.Berlin: Springer-Verlag;2013.

24.KosmiderB,LoaderJE,MurphyRC,MasonRJ.Apoptosis inducedbyozoneandoxysterolsinhumanalveolarepithelial cells.FreeRadicBiolMed.2010;48:1513–24.

25.FragaJ,BotelhoA,SáA,CostaM,QuaresmaM.Thelag structureandthegeneraleffectofozoneexposureon pediatricrespiratorymorbidity.IntJEnvironResPublic Health.2011;8:4013–24.

26.FarhatSC,AlmeidaMB,Silva-FilhoLV,FarhatJ,RodriguesJC, BragaAL.Ozoneisassociatedwithanincreasedriskof respiratoryexacerbationsincysticfibrosispatients.Chest. 2013;144:1186–92.

27.GryparisA,ForsbergB,KatsouyanniK,AnalitisA,TouloumiG, SchwartzJ,etal.Acuteeffectsofozoneonmortalityfromthe airpollutionandhealth:aEuropeanapproachproject.AmJ RespirCritCareMed.2004;15(170):1080–7.

28.WatkinsonWP,CampenMJ,NolanJP,CostaDL.

Cardiovascularandsystemicresponsestoinhaledpollutants inrodents:effectsofozoneandparticulatematter.Environ HealthPerspect.2001;109:539–46.

29.AgarwalA,SalehRA,BedaiwyMA.Roleofreactiveoxygen speciesinthepathophysiologyofhumanreproduction.Fertil Steril.2003;79:829–43.

30.KnucklesTL,DreherKL.Fineoilcombustionparticle bioavailableconstituentsinducemolecularprofilesof oxidativestress,alteredfunction,andcellularinjuryin cardiomyocytes.JToxicolEnvironHealth.2007;70:1824–37. 31.VerasMM,CaldiniEG,DolhnikoffM,SaldivaPH.Airpollution

andeffectsonreproductive-systemfunctionsgloballywith particularemphasisontheBrazilianpopulation.JToxicol EnvironHealthBCritRev.2010;13:1–15.

32.SilvaCA,HallakJ,PasqualottoFF,BarbaMF,SaitoMI,KissMH. Gonadalfunctioninmaleadolescentsandyoungmaleswith juvenileonsetsystemiclupuserythematosus.JRheumatol. 2002;29:2000–5.

33.MoraesAJ,PereiraRM,CocuzzaM,CasemiroR,SaitoO,Silva CA.Minorspermabnormalitiesinyoungmalepost-pubertal patientswithjuveniledermatomyositis.BrazJMedBiolRes. 2008;41:1142–7.

35.SilvaCA,CocuzzaM,BorbaEF,BonfáE.Cutting-edgeissuesin autoimmuneorchitis.ClinRevAllergyImmunol.

2012;42:256–63.

36.Rabelo-JúniorCN,FreiredeCarvalhoJ,LopesGallinaroA, BonfáE,CocuzzaM,SaitoO,etal.Primaryantiphospholipid syndrome:morphofunctionalpenileabnormalitieswith normalspermanalysis.Lupus.2012;21:

251–6.

37.Rabelo-JúniorCN,BonfáE,CarvalhoJF,BonfáE,CocuzzaM, SaitoO,etal.Penilealterationswithseveresperm

abnormalitiesinantiphospholipidsyndromeassociatedwith systemiclupuserythematosus.ClinRheumatol.

2013;32:109–13.

38.SilvaCA,BrunnerHI.Gonadalfunctioningandpreservation ofreproductivefitnesswithjuvenilesystemiclupus erythematosus.Lupus.2007;16:593–9.