Rosileia Milagres

Fundação Dom Cabral (FDC) / Mestrado Profissional em Administração — Gestão Contemporânea das Organizações; Centro de Referência em Governança Social Integrada (CRGSI), Núcleo de Sustentabilidade; Especialização em Gestão Nova Lima — MG / Brazil

Otávio Rezende

Centro Universitário de Belo Horizonte UNIBH / Instituto de Ciências Sociais Belo Horizonte — MG / Brazil

Samuel Araujo Gomes da Silva

Fundação Dom Cabral (FDC) / Centro de Referência em Governança Social Integrada (CRGSI), do Núcleo de Sustentabilidade Nova Lima — MG / Brazil

his article ofers an empirical base regarding the elements that make up alliance capability. Speciically, it attempts to understand the activities of the alliance portfolio management and its relationship to the rest of the organization. To accomplish this, it relies on premises in the literature relative to dynamic capabilities, the knowledge-based view, the competence-based view and the theory of organizational learning. he research method was a case stu-dy, using semi-structured interviews, analysis of documents and participative observation. he results show the importance and the role of the area in charge of managing the alliance portfolio. It points out this area’s functions related to the structure of the organization, provides empirical evidence of those functions, and demonstrates how the management process efectively proceeds in its diferent stages.

Keywords: alliance capability; collaborative strategies; inter-organizational relationship.

Papel e posição do departamento de alianças: caso Embrapa

O presente artigo tem por objetivo apresentarbase empírica sobre os elementos que compõem a capacidade de aliança. Especiicamente, procura entender as atividades da área de gestão do portfólio de alianças e sua relação com as outras áreas da organização. Para tanto, apoia-se nos pressupostos da literatura de capacidades dinâmi-cas, visão baseada em conhecimento, visão baseada em competências e a teoria do aprendizado organizacional. O método utilizado foi o estudo de caso, operacionalizado por meio de entrevistas semiestruturadas, análise de documentos e observação participante. Os resultados destacam a importância e o papel da área responsável pela gestão do portfólio de aliança. Além disso, complementa suas funções com a estrutura organizacional; oferece evidência empírica dessas funções e demonstra como o processo de gestão é efetivamente realizado nas diferentes fases que o compõem.

Palavras-chave: capacidade de aliança; estratégias colaborativas; relacionamento interorganizacional.

Papel y posición del departamento de alianzas de Embrapa

Este artículo tiene como objetivo presentar una base empírica sobre los elementos que conforman la capacidad de alianzas. En concreto, trata de entender las actividades del área de gestión de la cartera de alianzas y su relación con el resto de la organización. A tales efectos, se cimienta en las hipótesis de la literatura de capacidades dinámicas, visión basada en el conocimiento, visión basada en las competencias y en la teoría del aprendizaje organizacional. El método utilizado fue el estudio de caso, llevado a la práctica mediante la realización de entrevistas semiestruc-turadas, el análisis de documentos y la observación participante. Los resultados resaltan la importancia y el papel del área a cargo de la gestión de la cartera de alianzas. Además, complementa sus funciones con la estructura de la organización; y proporciona evidencia empírica de las suyas funciones y demuestra cómo el proceso de gestión tiene lugar de manera efectiva en las diferentes fases que lo componen.

Palabras clave: capacidad de alianza; estrategias de colaboración; relaciones entre organizaciones.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/0034-7612160046

1. INTRODUCTION

Strategic alliances are voluntary arrangements made by players that possess complementary resources and that, consequently, depend on one another if they are to achieve common objectives. hey enable the sharing or exchange of resources which, in turn, make room for the joint development and delivery of products, services, and/or technologies (Gulati, 1999). hey provide access to new markets and resources (Dyer and Singh, 1998); enable risk sharing and reduction of costs (Kogut, 1988). hey are regarded as essential because it is no longer possible to innovate in isolation, and knowledge belonging to diferent organizations must be combined to this end (Ring, Doz and Olk, 2005).

Despite the fact that they ofer great advantages to partners, a signiicant number of alliances deliver disappointing results (Dyer, Kale and Singh, 2004; Kale, Dyer and Singh, 2002). Reasons include deiciencies in the learning process and knowledge management (Inkpen, 2008; Jiang and Li, 2009), lack of speciic management tools, problems related to governance, asymmetries between knowledge and objectives, as well as the lack of adequate information exchange (Moller and Rajala, 2007; Dyer, Kale and Singh, 2004).

Previously restricted to the corporate world, the alternative of collaboration has more recently — starting in the 1990s, approximately — reached government (Sørensen and Toring, 2007; Klijn, 2008; McGuire and Agranof, 2011; Denhardt and Denhardt, 2015), with society, public organizations, non-governmental organizations, private and state-owned companies, social movements, universities, research institutes and other institutions acting as partners (Sørensen and Toring, 2007; Provan and

Lemaire, 2012). his has increased the importance of the debate on the governance model of such ar-rangements (Goldsmith and Eggers, 2004; Klijn and Skelcher, 2007; Provan and Kenis, 2008; Sørensen

and Toring, 2009; Roth et al., 2012; Toring et al., 2012) and on its relationship to authority, power and hierarchy (Toring, 2005; Borzel and Panke, 2007; Cristofoli, Markovic and Maneguzzo, 2012; Raab, Mannak and Cambré, 2013). As in the business world, however, an overvaluing of its merits as well as a tendency to minimize its problems and limitations can be detected (Sørensen and Toring, 2009; Toring et al., 2012). According to McGuire and Agranof (2011), despite the increase in the number of studies that demonstrate the importance of collaboration, few discuss the diiculties of the associated managerial activities, including processes, obstacles to the achievement of the desired results and the relationship between bureaucracy and multi-organizational arrangements.

A comparison between the promised gains and the results efectively achieved, together with the increasing number of such alliances, has opened up some research possibilities. Among them there are those focused on examining the relationship between the creation of shared management models and the structuring of new strategic alliances (Poletto, Araújo and Mata, 2011). here are also those intended to understand how organizations involved in this type of arrangement manage their alliance portfolio, especially with regard to the creation and development of organizational capability, also called alliance capability, in the search for better results (Simonin, 1997; Heimeriks, Duysters and Vanhaverbeke, 2005; Sluyts et al., 2011; Gonçalves and Gonçalves, 2011; Kale and Singh, 2007; Duysters et al., 2012). his line of research, therefore, has tried to understand the capacity of organizations to manage their collaborative arrangements, from a joint perspective.

and internal mechanisms to integrate and absorb knowledge (Draulans, DeMan and Volberda, 2003; Sluyts, Martens and Mathyssens, 2008; Sluyts et al., 2011). Zollo, Reuer and Singh (2002) identiied a positive impact on alliance performance of repeating the same partners. Gulati (2007), Kale and Singh (2007), Heimeriks, Klijn and Reuer (2009) and Sluyts and partners (2011) draw attention to the need for developing this capability of managing alliances. Some studies present evidence that a successful alliance depends on its efectiveness, (Anand and Khanna, 2000; Ireland, Hitt and Vaidyanath, 2002; Kale and Singh, 2007; Heimeriks, Klijn and Reuer, 2009). Others present this capability as an inter-vening factor between experience and the result, highlighting the role of the area responsible for the management of the alliance portfolio (Kale and Singh, 2007; Sluyts et al., 2011).

For Heimeriks, Klijn, and Reuer (2009), alliance capability is composed of four elements: speciic functions, solutions based on tools, training and the contracting of external consultants.

his article focus on the understanding of this capability, that is, the ability of a company to cap-ture, share and disseminate knowledge of alliance management (Heimeriks and Duysters, 2007). he purpose is to ofer an empirical background regarding the alliance capability elements — instruments and routines, training and the contracting of external consultants. Speciically, it aims at contributing to a better understanding of the activities of the alliance portfolio management area. In other words, to a better understanding of its functions and how it relates to the other elements of the alliance ca-pability and to other areas of the organization, including alliance managers.

Considering there is an increasing tendency towards the adoption of collaborative strategies, as Chesbrough (2003), Ring, Doz and Olk (2005), Lee and partners (2010), Schilling (2015) and other authors suggest, it is essential to understand the twists and turns of their management. However, it is important to know how to capture, share and disseminate throughout the organization all existing knowledge from the diferent areas related to each alliance; how the area in charge of the alliance portfolio actually manages it, and what do the relationships of this area and the alliance managers mean to the organization. he importance of such knowledge lies in its potential to promote learning and improvement for the future.

To this end, this article is based on a case study. he choice is not only based on the wide experi-ence of the studied institution, but also on the need to understand the speciicities of the tools and the perception of managers. Moreover, because there are still some gaps in the literature that have to be explored, in spite of all the interest in the formation of alliance capability, the conceptual advances or the systematization of past experiences. Speciically, researchers of the theme feel the lack of empirical evidence, especially of a qualitative nature, which could enrich the study of aspects of this function (Sluyts et al., 2011), and which would help to elucidate the elements that make up alliance capability (Anand and Khanna, 2000, Rothaermel and Deeds, 2006, Sluyts et al., 2011), for example, the role of the area that takes care of the alliance portfolio; which would also help the managers involved with this management (Gonçalves and Gonçalves, 2011).

the alliance managers). In this particular scenario, the case advances one step in relation to existing literature in that it includes the role of defender of the policies and culture that favour collaborative strategies within the organization. In addition, it demonstrates the need for speciic training in the management of this type of arrangement, a factor ignored by the literature so far. With regard to managers, public or private, the case — in presenting practices adopted in the ield — contributes to the development and application of the elements that structure the alliance capability. It also presents evidence related to the relationship and the role deined for the manager responsible for managing the alliance portfolio.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

Alliance capabilities are deined as the ability of the company, intentionally developed, to capture, share and disseminate know-how and know-why concerning the management of alliances (Draulans, DeMan and Volberda, 2003). It is a capability, diicult to obtain and to copy, which afects the results of the alliance portfolio (Heimeriks and Duysters, 2007). For the authors (op. cit.), this capability is nourished by experience and is composed of mechanisms and routines. Capabilities, therefore, assume the combination and integration of resources guided by the learning and knowledge accumulated in the routines. hey are selected based on the experience and strategic choices of the organization, and are inluenced by the organizational context formed by mechanisms such as processes, functions, rules and hierarchical structures. he concept of alliance capability is widely accepted as a lever for company performance and for the results of the cooperative agreement (Dyer and Singh, 1998; Gemünden and Ritter, 1997; Lorenzoni and Lipparini, 1999).

Some authors, in studying alliance capabilities, concentrate on a discussion of the experience of organizations, regarding it as a key element in capability formation (Anand and Khanna, 2000; Powell, Koput and Smith-Doerr, 1996; Rothaermel and Deeds, 2006; Duysters et al., 2012). Nevertheless, there is evidence that collaborative experience does not suice to ensure better results in future agreements. It is claimed that stand-alone experience by itself does not contribute to achieving results. Experience needs to be processed, interpreted and systematized (Simonin, 1997). An arrangement between ex-perience and these mechanisms - which store the organization’s learning and consubstantiate it into tools to transfer such knowledge — is a cornerstone in forming alliance capability (Simonin, 1997; Heimeriks and Duysters, 2007; Heimeriks, Klijn and Reuer, 2009). Furthermore, Kale and Singh (2007) point out the importance of the learning process, which leads to the desired results of the alliance management function.

Sluyts and partners (2011), in turn, suggest that prior experience is positively related to the ex-istence of the alliance function. hey also highlight the mediating role of the alliance manager or of the department responsible for such management, which constructs and uses learning mechanisms. hat is, an infrastructure capable of reinforcing the codiication processes of alliance management is created through guidelines and manuals that will, in the future, be disseminated throughout the entire organization. In sum, the area is the locus where acquired knowledge is placed and it is the codiication process of this knowledge that impacts results.

and any overlapping in the established agreements as well as among these and the corporate strategy. Moreover, it would be responsible for promoting exchange of experiences among the managers of the diferent cooperative agreements the company is involved in, preparing such managers for their daily challenges in alliance management.

As previously mentioned, Sluyts and partners (2011) empirically conirmed, based on a survey involving 189 companies, that prior experience is positively and signiicantly related to the existence of the alliance function. Draulans, DeMan and Volberda (2003) on the other hand, suggested, based on their results, that experience in an isolated fashion, in other words, learning-by-doing is limited to approximately 6 alliances. With more than this number, it is necessary to create mechanisms of institutionalization and structuring of learning via experience. Sluyts, Martens and Matthyssens (2008), in their turn, investigated 25 European companies and found most of them had created spe-ciic positions to manage alliances. In addition to an alliance manager in the business units, sponsors (seniors in charge), internal consultants (technical support experts) and a relationship manager (to establish personal contact with the partner) were also found. Hofman (2005) found that companies that possessed formalized managerial instruments and processes for multi-alliances had alliance ca-pability and in general were more satisied with their performance in these arrangements. In addition, he found evidence that the creation of a professional alliance management system is economically feasible in the case of those companies that possess multiple alliances and where this strategy pos-sesses a high level of importance.

According to Heimeriks, Klijn, and Reuer (2009), other elements form alliance capability: tool-based solutions, which are instruments that accumulate knowledge and information on the diferent stages of an alliance lifecycle (Heimeriks, Klijn and Reuer, 2009). Procedures, such as decision-making processes, legal models, check-lists (Gulati, 1999), a database with speciic information on partners and alliance, contracts and governance structures used, statements and reports, established commu-nication processes, intranets, rescinding terms and negotiation processes, among others, make up this second category. Simonin (1997) claims that this accumulation of knowledge and consequent development of skills to select, for instance, partners and manage conlicts is conducive to better re-sults. Heimeriks, Klijn, and Reuer (2009) mention two other categories, namely, training and hiring external consultants. As to the former, they list company-developed training or external training, which bring speciic knowledge and allow knowledge exchange. Furthermore, room is made for persons in charge of cooperative agreements to develop and hone their own skills and competencies, attitudes and knowledge (Sluyts, Martens and Matthyssens, 2008). Sluyts and partners (2011) found no evidence of the efect of these mechanisms on the results of the alliance.

he analysis of the alliance function also demonstrates that its creation requires a large investment from the organization, which points to the importance of observing where it is in the organizational structure — whether it should be located at the corporate or competitive level. It was also observed that rigid codiication of the actions linked to alliance management, and making them a routine, can lead to an excessive emphasis on processes, reducing agility in decision-making (Kale, Dyer and Singh, 2002). hey can also lead to organizations engaging in strategic actions, directed towards collabora-tion to use and reine existing competences and knowledge, focused on the short term and on proit. his type of behaviour can be prejudicial for the irm by making it vulnerable to exogenous changes and, consequently, leading it to sufer from the long term obsolescence of resources (Kauppila, 2013).

here appears to be a consensus about the importance of alliance capabilities and their inluence on the partnerships’ results. Some authors stress the role of these capabilities as an intermediary element between experience and performance (Kale and Singh, 2007; Sluyts et al., 2011 Duysters et al., 2012), others defend the importance of instruments and routines (Gemunden and Ritter, 1997; Simonin, 1997; Gulati, 1999; Dyer and Singh, 1998; Lorenzoni and Lipparini, 1999; Draulans, De-Man and Volberda, 2003; Heimeriks, Duysters, 2007; Heimeriks, Klijn and Reuer, 2009; Sluyts et al., 2011), and there are others that point to the importance of an area or of a manager responsible for the coordination of the alliance portfolio (Draulans, DeMan and Volberda, 2003; Hofman, 2005; Kale and Singh, 2007; Sluyts, Martens, and Matthyssens, 2008; Heimeriks, Klijn and Reuer, 2009; Sluyts et al., 2011; Kauppila, 2013). Nevertheless, empirical evidence is needed, especially those regarding to a deeper analysis, in amplitude and intensity, or that grasps speciic aspects of the process and the tools linked to alliance capability (Sluyts et al., 2011). According to Gonçalves and Gonçalves (2011), such contribution is not restricted to the literature, but mainly to the implications on the work of private or public managers involved in the management of alliance portfolios. his paper has the purpose of supplying elements that contribute to illing this gap, in particular by ofering empirical evidence of the activities of this area.

3. METHOD

his study ofers an empirical background regarding the elements that structure the alliance capability — tools, routines, training and hiring of experts. In particular, it contributes to a better understanding of the activities of the area responsible for the management of the alliance portfolio. hat is, what is its role and how it is related to the other elements that structure the alliance capability and to the other areas of the organization to which it belongs, including alliance managers.

appro-priate. How does it relate to the alliance managers and to the organization as a whole? How does it relate to the other elements that structure the alliance capability? he empirical analysis is essential to understanding how these relationships are established and their limits and potentialities.

Understanding in detail how the elements that structure the alliance capability function, mainly in the area responsible for managing the portfolio of alliances, is extremely relevant for both private and public managers, by reason of their growing involvement with this type of arrangement. he de-tails of its daily operation may help them achieve better results when managing their own portfolios. In this particular sense, the case study method was chosen, due to its ability to an promote an intense examination — wide-ranging and deep — of a unit of study (Greenwood, 1973). Despite some questioning of the possibility of generalizing Case Study results and their limits regarding theory formation, it is accepted that starting with a particular set of results, they can ofer theoretical propositions to be applied to other contexts (Yin, 2005).

3.1 DATA COLLECTING

Data collection started in February 2009 and ended in December 2011. hree diferent data-gathering mechanisms were used: semi-structured interviews, document analysis, and participative observation in some workshops held by Embrapa (Empresa Brasileira de Pesquisa Agropecuária — the Brazilian Company for research into Agriculture and Cattle Raising), the studied organization, with the purpose of monitoring and evaluating projects undertaken in partnership. he identiication of the unit of analysis was based on information from document analysis and from a meeting held with Embrapa’s executive directors of Research and Development. he choice was based on the characteristics of these alliances, that is, the length and number of partners involved, as well as their complexity and links to themes representing strategic challenges, from Embrapa’s standpoint. As a result of this irst phase, it was decided to study the Macroprogram1, called here MP1 (Internal nomenclature to designate projects under the coordination of a manager and classiied according to their characteristics — such as complexity, form of inancing, goals etc.), as it encompasses the alliances of longer duration and that have the greater number of partners.

Next, three-hour interviews were held with the MP1 manager and diferent documents were collected. his material would help in correctly determining the limits of the unit of analysis. he in-terviews conducted and document analysis investigated MP1’s structure, its portfolio of alliances and the challenges involved, plus the interfaces between this alliance portfolio and other Embrapa areas.

his analysis led to a larger number of Embrapa personnel being interviewed: for example, the four major supporters of MP1 in conducting its tasks were identiied. A representative of each of these support areas was interviewed, producing, altogether, 03 hours and 16 minutes of recording.

his wide overview made it possible to advance the analysis in each of MP1’s networks. hus, seventeen MP1 alliances were analyzed, using two diferent instruments: individual interviews with each network leader (28 hours and 23 minutes of taping) and participation in a workshop.

Altogether, 25 interviews were conducted lasting 34 hours and 39 minutes. All interviews were based on semi-structured scripts previously developed, and were recorded and transcribed.

his/her presentation at the 2011 Workshop. his material included the description of: their objectives, goals, evolution, activities already done and yet to be conducted, work program, and schedule and management.

he third data collection instrument was Workshop Participation. Two researchers were invited to participate in the “V Workshop on the Monitoring and Evaluation of Projects in Network of the MP1”, a three-day workshop held annually which is structured from a script made available by Embrapa’s MP1 with ad hoc consultants invited to participate. Each alliance leader had 40 minutes to present his/her alliance and its evolution. Debate and Q&A followed each presentation, presenting issues such as: overall vision (action strategy, tools to integrate teams and activities, management model, funding and inancing); results (main goals and outputs — new knowledge, products, processes and services, percentages planned/actually done, ways to deliver results — publications and technology transfer); alliance constraints & limitations (chief problems or threats to technical execution and management, solutions found); perspectives for the alliance (possible unfolding, possible interactions with other projects in and out of Embrapa).

3.2 DATA ANALYSIS

he theoretical framework discusses the importance of experiences undergone by diferent players, the development of routines and other mechanisms, as well as the role of a speciic function to look ater the alliance portfolio, added to the training and contracting of third parties for the formation of alliance capabilities. From these categories, a ield of study is chosen. Joint investigation with MP1 sought to understand the organizational level, inasmuch as it provides a systemic vision of managing 17 alliances. Instruments used in such management were analysed. Interviews with alliance leaders sought to detail and evaluate the instruments used, as well as investigating inter-unit interactions, since these alliances involve both internal and external partners and a relationship with the MP1.

he interviews, document analysis, notes taken and observations made during the Workshop contributed to an understanding of the set of elements that structure the alliance capability.

Two independent researchers separately classiied the material and subsequently, a third research-er — based on meetings and discussions — did the inal analysis. he Atlas.ti sotware was used and the techniques applied were thematic content analysis (Krippendorf, 2004) and the comparative method (Strauss and Corbin, 1990).

4. CASE

is to institutionalize the mechanisms of approval, coordination and control of the alliance projects, resulting in the formation of alliances.

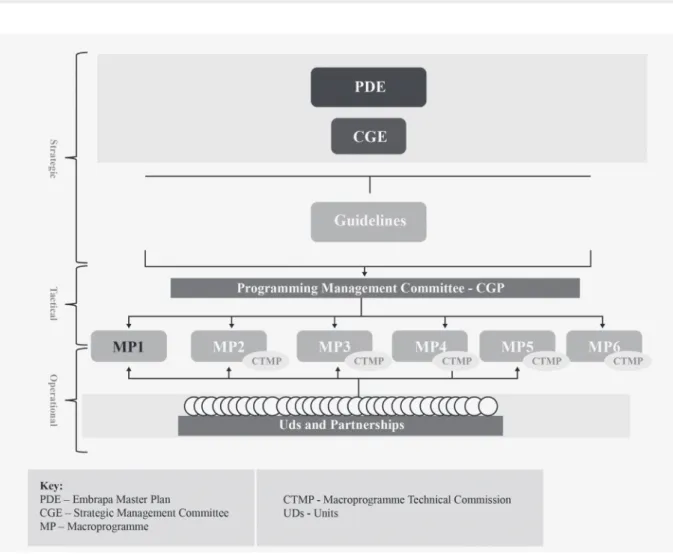

he implementation of this strategy is coordinated by a programming management committee consisting of a collegiate body responsible for the coordination and balancing of the project portfolios of the 6 macro programmes, possessing speciic characteristics as regards the institutional arrange-ments, the adherence of its members and the team format. his committee helps the organization in making its programs operational, keeping in view the attainment of its expected results. Each of the macro programmes has a manager responsible for standardizing the managerial instruments and developing new ones to meet his or her speciic needs. he positioning of these macro programmes in the Embrapa management system can be seen in igure 1.

FIGURE 1 EMBRAPA MANAGEMENT SYSTEM

Source: Embrapa (2011).

knowledge), strategic (critical for the development and competitiveness of Brazilian agribusiness), or can implement public policy and applied research. In July 2011, the MP1 portfolio had 17 networks.

According to igure 1, MP1 has one manager, who has the support of the Technical Commission formed by members indicated by the Executive Board of Embrapa, who may be from within or from outside the company. he function of this commission is to technically support the selection, moni-toring and delivery of the MP1projects. It is also the responsibility of MP1 to ensure that the alliances of its portfolio are aligned with the Embrapa guidelines.

4.1 THE MANAGEMENT OF THE EMBRAPA ALLIANCES PORTFOLIO

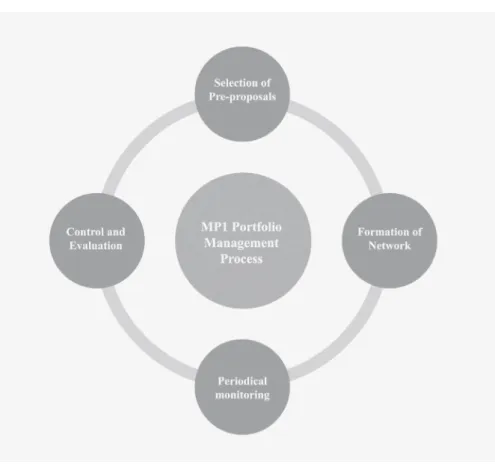

he Embrapa projects in alliance are generated from the Master Plan, which deines the institutional agenda in terms of development and proposes the strategic lines and objectives to be reached. As described in igure 2.

FIGURE 2 ELEMENTS OF THE MP1 RESEARCH NETWORKS PORTFOLIO MANAGEMENT PROCESS

Source: SEG Manual: characteristic and management of MP1 (elaborated by the authors).

that will be responsible, through its macro programme coordinating sectors and managers, for the formation, management and monitoring of the alliances.

he formation of the alliance assumes the need to integrate the researchers involved in the project and prospect for possible members. From the deinition of the participating team, the work of ad-justment of the pre-proposal starts, based on the recommendations of the technical commission and the agreements made with the members of the alliance. he team, the leaders, objectives, schedules and results are deined.

hroughout the formation of the alliance, much emphasis is placed on its management process, as it is understood that this is the biggest bottleneck. It is considered that if this process is not very well structured, the chances of the alliance failing to achieve the desired results are considerable.

In addition to the materials made available by the management system, other instruments such as reports, monitoring meetings, e-mails, lists of discussions and homepage are used in this phase. Although indications exist from MP 1 relative to the coordination of the alliance (its structure and instruments), there is great lexibility for adaptations, which are made in accordance with the per-ceptions of each of the leaders, their competence in terms of management, their involvement and the characteristics of the alliance itself. During the interviews, several initiatives in this sense were mentioned and the following are highlighted: those relative to work monitoring (development of new systems); to communication management (creation of new functions to facilitate communication); to knowledge management (creation of channels/transverse lows to promote interaction between the component projects); and to innovation management (creation of responsible party). Nevertheless, complaints were also made, speciically concerning the lack of support for the day-to-day manage-ment of the alliance. It was thought that the investmanage-ment of the institution in capacitating leaders was low, that the instruments could be improved and that there were insuicient personnel to efectively coordinate and execute the work.

here is no guideline on how to do this [the day to day management of the alliance]. So the success of each alliance depends on its own creativity. he size of the alliances, together with management problems, makes the task to be faced by the leaders very challenging.

Regarding the training of leaders, the course ofered by MP1 in the approval of the project was mentioned as being considered insuicient for the challenges that involve complex alliances such as those formed by MP1.

As to the monitoring, it is the responsibility of the MP1 manager to monitor execution of the projects to guarantee that they comply with the proposed scope and are guided by Embrapa strate-gies. For this, he enjoys the support of each of the leaders, who become responsible for conducting it, its coordination, the management of resources and compliance with the proposed targets. In ad-dition to the leaders, the MP1 manager can count on the ad hoc consultants, to monitor periodically the progress of the projects, to ensure strategic alignment, eicient management and make course corrections, if necessary. Some of the instruments foreseen for this monitoring by the management system are: 1) half-yearly progress reports; 2) In loco visits by the MP1 manager; and 3) Periodical evaluation conducted by means of monitoring workshops.

results. In addition to this workshop, there are 2 managerial reports that allow the work monitoring. Factors analyzed are: schedules, attainment of targets (% attained), number of meetings held, number of experiments set up, number of students supported by the project, among others. According to the MP1 manager, these mechanisms make it possible to monitor, evaluate, make course corrections to the projects, and in some cases have even made cancellation possible.

Evaluation of the alliances is also conducted by the Programming Management Committee (see igure 1), which consists of 19 people, being three of them Embrapa directors, and the managers of the Macro programmes.

4.2 THE MP1 ACCORDING TO THE INTERVIEWEES

he interviewees consider that the MP1 has the role of controlling, supporting, giving support to the formalization of the alliances and facilitating the management process.

It formalizes. It is that coordination that provides authenticity for the alliance. It [MP1] provides support in the following way: it holds one meeting per year, people go and, in 40 minutes, quickly presents the project. It is very quick, there is no time to show details. And based on that, they make an evaluation, but I think it is an evaluation more to see if it is working. And they indicate, through that presentation, the problems they have.

For some, the functions of the MP1 could be expanded. hey draw attention to the need to system-atize instruments for the management of alliances. hey attach special importance to communication, which is considered to be one of the key axes in alliances, and demonstrate concern with the need to maintain a systemic view of the project. To this end, the constant exchange of aligned information is fundamental, in addition to the need for formatting instruments that make this exchange possi-ble. he purpose is to have an evaluation system that contemplates goals, but also processes; that demonstrates and values the interaction and interdependence among the participants and, in this way, strengthens work in alliance.

[...] I think that we could have much more support, in terms of treating our diiculties like leaders. [...] we should have a little more autonomy, not be so tied to the company structure, because I cannot even report directly to the research and development depart-ment. I have to report to [my boss], who, very oten, doesn’t understand my project. I think that in addition to organizing the portfolio, it should be a question of supporting the directing of the projects. Perhaps identifying strangulation points. Not a control but a way of supporting the management itself.

he management of the alliance is still a question of luck, because it is not prepared for that. Our technical body does not have the capacity [for the management of alliances]. Our managers are researchers.

issues. Although the advantages of this system of evaluation and control have been stressed, some points of adjustment were also mentioned:

[...] we end up formatting the presentation for it to be well evaluated. So that it doesn’t always really relect our position. It makes it seem that everything is ine, but it is full of problems. Because if we show problems we go right down. So we end up even refusing the idea of the workshop. It is very easy for you to get good marks, as you just show the good things [...] there should be a closer monitoring of what has been done, not a report where I mark X, Y, A and that is it.

It was also mentioned in the interviews that the alliance evaluation system is confused with the unit evaluation system, which generates internal competition between the diferent Embrapa units. In addition, the standardization of the indicators for the evaluation of alliances was criticized, and as a consequence, the need was emphasized to open more space for customized reports, that would demonstrate the results achieved and their evolution with greater precision.

5. ANALYSIS OF THE CASE AND DISCUSSION

Starting from contributions from the technical literature, this case study produced empirical infor-mation that clariies the elements comprising alliance capability. In particular, it revealed relevant details of the functions assigned to the area that manages the portfolio. Speciically, the study was an attempt to understand the functions of this area, and how it is related to the other elements that make up alliance capability, and to the other areas of the organization, including managers of alliances. he objective of the study is very pertinent because of the increasing importance of alliances both in the private as in the public sectors.

In accordance with the literature, the analysis of alliance capability can be divided into two groups (Sluyts, Martens and Matthyssens, 2008). he irst focuses on the experience of the organizations in this type of arrangement as a key element in their formation (Powell, Koput and Smith-Doerr, 1996; Anand and Khanna, 2000). he second looks at the importance of investments in the devel-opment of instruments and speciic functions to deal with the alliance portfolio, as they believe that the experience needs to be treated, interpreted and systematized (Draulans, DeMan and Volberda, 2003; Sluyts, Martens and Mathyssens, 2008; Sluyts et al., 2011). he connection between experi-ence and these mechanisms — that store the organization’s learning and which are instruments in this knowledge transfer — are central to the formation of alliance capability (Simonin, 1997; Kale, Dyer and Singh, 2002; Zollo and Winter, 2002; Heimeriks and Duysters, 2007; Kale and Singh, 2007; Heimeriks, Klijn and Reuer, 2009; Sluyts et al., 2011). Particularly Sluyts and partners (2011), Heimeriks and Duysters (2007) and Heimeriks, Klijn and Reuer (2009), among others, highlight the importance of the area responsible for the management of the alliance portfolio for alliance capability as a whole.

are spread throughout the organization and practiced by all the alliances, constituting therefore or-ganizational routines — they are repetitive and collective. hey are perceived as important, as they contribute to the spread of a pattern accumulated by the organization throughout its experience in directing alliances. In this sense, they fulil their role in acting as a depository and transferor of knowledge. hey provide references for the leaders in the coordination of the alliances, diminish their uncertainty in relation to the pattern of behaviour to be adopted and, consequently, diminish conlicts within the domain of the alliance and between this and the organization. hey allow control in relation to the directing process and to the results to be achieved. he MP1, through its 17 alliance agreements, developed a series of them.

However, as discussed in the specialized literature, the experiences are context and age depen-dent (Simonin, 1997; Sampson, 2005). In this sense, when transferred, they may not it the speciic conditions, and thus not produce the expected results. In addition, as foreseen by Kale, Dyer and Singh (2002) and Kauppila (2013), there is a risk in the standardization of instruments, routines and processes that structure the alliance capability. his fact was cited in the Embrapa case when the stan-dardization of indicators was criticized and pointed as not adequate to the speciic conditions of each of the networks, therefore having modiications suggested or even the adoption of new instruments. he need to open more space for more customized reports was highlighted, thus showing the results achieved and their evolution with greater precision.

herefore, regarding the instruments, processes and routines developed, the case provides some hints regarding its own limits. hat is, they may exhibit particularities that restrict their transfer, con-irming the suggestion of Simonin (1997), Sampson (2005), Kale, Dyer and Singh (2002) and Kauppila (2013). In addition, it highlights the role of the area responsible for the joint management of alliances, that is, the role of acting as an agent of codiication of the developed processes and instruments. On the one hand, if this action opens up possibilities for the transfer of knowledge and experiences, promotes organizational learning and saves eforts with the creation of new procedures etc., on the other hand it stiles and reduces the possibilities of adjustments. Regarding its creation and develop-ment, the case points to the beneits of making more room for adjustments to the actual conditions of each speciic alliance. his implies greater participation of the speciic areas that are involved in the daily operation. Additionally, centring the mentioned codiication in the area responsible for the management of the portfolio may result in excessive emphasis on processes and bureaucratization, thus reducing the necessary agility and customization.

Moreover, the interviewees recognize that the structure adopted by the organization is lexible. Despite that, the adjustments efectively proposed were few. his may be justiied by the fact that many of the alliance leaders do not possess qualiications in management. hey are researchers, technicians who have assumed positions of management. his aspect is conirmed by the general demand for greater investment in training solutions. In this sense, this case study points to another situation, diferent from that presented by Sluyts and partners (2011) that does not embrace evidence regarding the efectiveness of training in the results of alliances. In accordance with the respondents in this case, training helps them to achieve better results.

periodical monitoring, control and evaluation. We emphasize that in the formation of the alliance it is considered that the MP1 will provide integration between the researchers involved — a positive point, as suggested by the interviewees. During the monitoring stage, the MP1 ofers management instruments and monitors the execution of the projects, through instruments such as reports, visits and periodical evaluations, among which the workshop should be especially mentioned. Finally, for control and evaluation, one bases oneself on the analysis of reports and on the evaluations made by forums in which participants from outside and inside Embrapa participate. As proposed by Sluyts and partners (2011), the MP1, based on Embrapa’s experience, codiies the process of alliance manage-ment by ofering diferent tools, guides, manuals etc. For the interviewees, the MP1 has the following functions: control, general support, support for the formalization of the alliances and the facilitating of the management process. Other possibilities were, however, mentioned, such as providing greater support for management, stressing closer monitoring of the daily management of the alliances and expanding the use of training solutions.

With reference to the relationship established between the alliance portfolio management area and the organization, the case presented suggested that the MP1 acted as an intermediary between the managers of alliances and Embrapa, discussing the interfaces between the management models adopted and proposing adjustments to the structure of the company. hese refer particularly to HR policy. According to evaluations, the system of performance and individual evaluation is not aligned to the control and evaluation system of the alliances. his lack of integration weakens the alliance and creates obstacles to achieving the established results. Furthermore, it limits the role of leadership, as the evaluation of the members of the alliances’ team cannot be used as an incentive mechanism. In this sense, this concern with the establishment of a culture and spirit of alliance in the organization should be stressed - mainly because it is a fundamental aspect for an organization that possesses as its key pillar the strategy of the formation of alliances. It should be noted that there is a lack of elements that provide evidence of the importance of the organization’s cooperation strategy and connecting it with the strategies of the diferent units.

hese results conirm those proposed by Sluyts and partners (2011) and Kale, Dyer and Singh (2002), both as regards the position of the area charged with coordinating the alliance portfolio and the support given by the organization’s top management. A very curious aspect, however, is that, de-spite the fact that the MP1 is located at the corporate level and has the function of aligning alliances and their objectives with the organization’s strategic interests, the respondents emphasized that the area needs to act as a mediator between the alliances and the top management. he MP1 should act as a defender of the policies and cultures that favour the collaborative strategy, acting with Embrapa in the review of organizational structures and mechanisms — such as a system of incentives and hierarchical structure — which apparently are not aligned with this culture.

6. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

his research contributes to the debate presenting empirical evidence of the process and the tools linked to alliance capability. In other words, in presenting the management system used by the MP1, it provides better and deeper understanding of the functions of the alliance portfolio management area, how it relates to the other elements that structure the alliance capability and with the other areas of the organization, including the managers of alliances. Speciically, the case study corrobo-rated the indings of the literature on the importance of experience, as well as on the establishment of instruments such as routines and other procedures that accumulate and transfer the knowledge acquired throughout the life of the organization’s alliances. It contributed to the endorsement of the roles of control, monitoring, support for the formation and facilitating of the management process. It further provided evidence of its role as a bridge between the corporate strategy and that of the alliances themselves. Empirical analysis also advanced in pointing to the need for including in the role of the manager the connection with the organizational structure and the internal promotion of the alliance culture, highlighting aspects such as the system of incentives and control, the hierarchical structure and leadership.

As a managerial contribution, the work highlights the importance and the role of the area respon-sible for the management of the alliance portfolio; it demonstrates what are the instruments used in making the alliance management operational, and points out the challenges linked to this function. hat is, the case works as a guide for managers involved in the direction of this activity.

For public managers, these contributions are especially relevant because, if it is true that the State tends to use alliances to deliver certain public services and goods, it is of fundamental impor-tance that the State understands the particularities of the management of a portfolio of alliances. It is, therefore, important that all knowledge accumulated and spread over diferent sections of the government be stored. To achieve this, the information and experiences gathered by the diferent government agencies involved with the alliances must be systematized and organized. Neverthe-less, it is important to attend to the fact that the dispersion of public organizations, with regard both to the geographical location of their activity, and to their areas or sectors, may expand the limits on the replication of routines and tools. In addition, these arrangements favour horizontal relationships, where hierarchy is replaced by the search for consensus and by shared leadership. However, the State is an institution whose power and status do not contribute to challenge hierarchy. Besides that, many governmental institutions are afected by strong bureaucratization and politics. he following question is, therefore, pertinent: how does one harmonize the expectations for more horizontal relationships with structures that exhibit such characteristics? he present study did not try to answer this question and, most probably, the question has not even been framed yet. Anyway, it is an important point to be kept in mind by public managers involved with alliances and an important area for new research.

the alliance capability, its speciicities, the perceptions of executives and their contributions to the limits and possibilities of improvement.

REFERENCES

ANAND, Bharat N.; KHANNA, Tarun. Do irms

learn to create value? he case of alliances. Strategic

Management Journal, v. 21, n. 3, p. 295-315, 2000.

BORZEL, Tanja A.; PANKE, Diana. Network gover-nance: efective or legitimate? In: SØRENSEN, Eva;

TORFING, Jacob. (Ed.). heories of democratic network

governance. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

CHESBROUGH, Henry W. he era of open

innova-tion. Sloan Management Review, v. 44, p. 5-41, 2003.

CRISTOFOLI, Daniela; MARKOVIC, Josip. How to make public networks really work: a qualitative

comparative analysis. Public Administration, v. 94,

n. 1, p. 89-110, 2016.

DENHARDT, Janet V.; DENHARDT, Robert B. he

new public service revisited. Public Administration

Review, v. 75, n. 5, p. 664-672, 2015.

DYER, Jefrey H.; KALE, Prashant; SINGH, Harbir.

When to ally and when to acquire. Harvard Business

Review, v. 82, n. 7/8, p. 109-115, 2004.

DYER, Jefrey H.; SINGH, Harbir. he relational view: cooperative strategy and sources of

interor-ganizational competitive advantage. Academy of

Management Review, v. 23, n. 4, p. 660-679, 1998.

DRAULANS, Johan; DeMAN, Ard-Pieter; VOL-BERDA, Henk W. Building alliance capability: management techniques for superior alliance

perfor-mance. Long Range Planning, n. 23, p. 151-166, 2003.

DUYSTERS, Geert et al. Do irms learn to manage alliance portfolio diversity? he diversity-perfor-mance relationship and the moderation efects of

experience and capabalility. European Management

Review, v. 9, p. 139-152, 2012.

EMBRAPA. Manual do Sistema Embrapa de Gestão:

fundamentos, estrutura e funcionamento do SEG. Brasília, DF: Embrapa, 2011.

GEMÜNDEN, Hans G.; RITTER, homas.

Mana-ging technological networks: the concept of network competence. In: GEMÜNDEN, Hans G.; RITTER,

homas; WALTER, Archin (Ed.). Relationships and

networks in international markets. Oxford: Perga-mon: Elsevier Science, 1997. p. 294-304.

GOLDSMITH, Stephen; EGGERS, Willian D.

Gover-ning by network. he new shape of the public sector. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2004.

GONÇALVES, Francisco R.; GONÇALVES, Vítor C. he role of the alliance management capability. he Service Industries Journal, v. 31, n. 12, p. 1961-1978, 2011.

GREENWOOD Ernest. Métodos principales de investigación social empírica. In: GREENWOOD,

Ernest. Metodología de la investigación social. Buenos

Aires: Paidós, 1973.

GULATI, Ranjay. Managing network resources:

alliances, ailiations, and other relational assets. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

GULATI, Ranjay. Network location and learning: the inluence of network resources and irm capabilities

on alliance formation. Strategic Management Journal,

v. 20, n. 5, p. 397-420, 1999.

HEIMERIKS, Koehn H.; DUYSTERS, Geert. Allian-ce capability as a mediator between experienAllian-ce and alliance performance: an empirical investigation into

the alliance capability development process. Journal

of Management Studies, v. 44, n. 1, p. 25-49, 2007.

HEIMERIKS, Koen H.; DUYSTERS, Geert;

VA-NHAVERBEKE, Wim. Developing alliance

capabi-lity: an empirical study. [SMG Working Paper No.

13/2005]. Copenhagen, DI: Copenhagen Business School, 2005.

HEIMERIKS, Koen; KLIJN, Elko; REUER, Jefrey

J. Building capabilities for alliance portfolio. Long

Range Planning, v. 42, n. 1, p. 96-114, 2009.

HOFFMANN, Werner. H. How to manage a

por-tfolio of alliances? Long Range Planning, v. 38, n. 2,

p. 121-143, 2005.

INKPEN, Andrew C. Knowledge transfer and in-ternational joint ventures: the case of Nummi and

General Motors. Strategic Management Journal, v.

29, p. 447-453, 2008.

IRELAND, R. Duane; HITT, Michael A.; VAIDYA-NATH, Deepa. Alliance management as a source of

competitive advantage. Journal of Management, v.

28, n. 3, p. 413-446, 2002.

JIANG, Xu; LI, Yuan. An empirical investigation of knowledge management and innovative

perfor-mance: the case of alliances. Research Policy, v. 38,

p. 358-368, 2009.

long-term alliances success: the role of the alliance

function. Strategic Management Journal, v. 23, n. 8,

p. 747-767, 2002.

KALE, Prashant; SINGH, Harbir. Building irm ca-pabilities through learning: the role of the alliance learning process in alliance capability and irm-level

alliance success. Strategic Management Journal, v. 28,

n. 10, p. 981-1000, 2007.

KAUPPILA, Olli P. Alliance management capability and irm performance: using rource-based theory

to look inside the process black box. Long Range

Planning, v. 48, n. 3, p. 1-17, 2013.

KLIJN, Erik H. Networks as perspective on policy and implementation. In: CROPPER, Steve et al. Handbook of interorganizational relations. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. p. 118-146.

KLIJN, Erik H.; SKELCHER, Chris. Democracy

and governance networks: compatible or not? Public

Administration, v. 85, n. 3, p. 587-608, 2007.

KOGUT, Bruce. Joint ventures: theoretical and

em-pirical perspectives. Strategic Management Journal,

New Jersey, v. 9, n. 4, p. 319-332, 1988.

KRIPPENDORFF, Klaus. Content analysis. An

intro-duction to its methodology. 2. ed. housand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2004.

LEE, Jeho et al. A hidden cost of strategic alliances

under Schumpeterian dynamics. Research Policy, v.

39, n. 2, p. 229-238, 2010.

LORENZONI, Gianni; LIPPARINI, Andrea. he le-veraging of interirm relationships as a distinctive

or-ganizational capability: a longitudinal study. Strategic

Management Journal, v. 20, n. 4, p. 317-338, 1999.

McGUIRE, Michael; AGRANOFF, Robert. The

limitations of public management networks. Public

Administration, v. 89, n. 2, p. 265-284, 2011.

MOLLER, Kristian; RAJALA, Arto. Rise of strategic

nets — new models of value creation. Industrial

Marketing Management, v. 36, n. 7, p. 895-908, 2007.

POLETTO, Carlos A.; ARAÚJO, Maria A. D. de; MATA, Wilson da. Gestão compartilhada de P&D: o

caso da Petrobras e a UFRN.Rev. Adm. Pública, Rio

de Janeiro, v. 45, n. 4, p. 1095-1117, jul./ago. 2011.

POWELL, Walter W.; KOPUT, Kenneth, W.; SMI-TH-DOERR, Laurel. Interorganizational

colla-boration and the locus of innovation: networks

of learning biotechnology. Administrative Science

Quarterly, v. 41, n. 1, p. 116-145, 1996.

PROVAN, Keith G.; KENIS, Patrick. Modes of ne-twork governance: structure, management, and

ef-fectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research

and heory, v. 18, n. 2, p. 229-252, 2008.

PROVAN, Keith G.; LEMAIRE, Robin H. Core con-cepts and key ideas for understanding public sector organizational networks: Using research to inform

scholarship and practice. Public Administration

Review, v. 72, n. 5, p. 638-648, 2012.

RAAB, Jorg; MANNAK, Remco S.; CAMBRÉ, Bart. Combining structure, governance, and context: a conigurational approach to network efectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and

he-ory, v. 25, n. 2, p. 479-511, 2013.

RING, Peter S.; DOZ, Yves L.; OLK, Paul M.

Mana-ging formation processes in R&D Consortia.

Califor-nia Management Review, v. 47, n. 4, p. 137-156, 2005.

ROTH, Ana L. et al. Diferenças e inter-relações dos conceitos de governança e gestão de redes horizon-tais de empresas: contribuições para o campo de

estudo. Revista de Administração —Rausp, v. 47, n.

1, p. 112-123, 2012.

ROTHAERMEL, Frank; DEEDS, David. Alliance type, alliance experience and alliance management

capability in high-technology ventures. Journal of

Business Venturing, v. 21, n. 4, p. 429-460, 2006.

SAMPSON, Rachelle C. Experience effects and

collaborative returns in R&D alliances. Strategic

Management Journal, v. 26, n. 11, p. 1009-1031, 2005.

SCHILLING, Melissa A. Technology shocks,

tech-nological collaboration, and innovation outcomes.

Organization Science, v. 26, n. 3, p. 668-686, 2015.

SIMONIN, Bernard. he importance of collaborative know-how: an empirical test of the learning

organi-zation. Academy of Management Journal, v. 40, n. 5,

p. 1150-1174, 1997.

Sep-tember). Available at: <www.impgroup.org/uploads/ papers/6786.pdf>. Acessed on: 18 Nov 2015.

SLUYTS, Kim et al. Building capabilities to manage

strategic alliances. Industrial Marketing

Manage-ment, v. 40, n. 6, p. 875-886, 2011.

SØRENSEN, Eva; TORFING, Jacob. Making gover-nance networks efective and democratic through

metagovernance. Public Administration, v. 87, n. 2,

p. 234-258, 2009.

SØRENSEN, Eva; TORFING, Jacob. heories of

de-mocratic network governance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

STRAUSS, Anselm; CORBIN, Juliet. Basic of

qua-litative research. Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newburry Park, Ca: Sage Publications, 1990.

TORFING, Jacob. Governance network theory:

towards a second generation. European Political

Science, v. 4, n. 3, p. 305-315, 2005.

TORFING, Jacob et al. Interactive governance:

ad-vancing the paradigm. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

ZOLLO, Maurizio; REUER, Jefrey; SINGH, Harbir. Interorganizational routines and performance in

strategic alliances. Organization Science, v. 13, n. 6,

p. 701-713, 2002.

ZOLLO, Maurizio; WINTER, Sidney G. Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities. Organization Science, v. 13, n. 3, p. 339-351, 2002.

YIN, Robert K. Estudo de caso: planejamento e

mé-todos. 3. ed. Porto Alegre: Bookman, 2005.

Rosileia Milagres

Professor and researcher at Fundação Dom Cabral, studying the ields of strategy, inter-organizational networks and collaborative governance. Professor Milagres holds a PhD in Economy from the Institute of Economy of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro; a Masters in Economy from the Federal University of Minas Gerais; and a Bachelor Degree in Economy from the Pontiical Catholic University of Minas Gerais. E-mail: rosileiam@ fdc.org.br.

Otávio Rezende

Professor and researcher at the University Center of Belo Horizonte (UNIBH), studying the ields of international business, business strategy and inter-organizational networks. Professor Rezende holds a PhD in Adminis-tration from the Federal University of Minas Gerais; a Masters in AdminisAdminis-tration from the Faculty of Human Sciences of Pedro Leopoldo (in the state of Minas Gerais); and a Bachelor Degree in Administration with focus on international trade from the Faculty of Management Sciences of UNA. E-mail: otrezende@gmail.com.

Samuel Araujo Gomes da Silva