Trees,ForestsandPeople2(2020)100026

ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Trees,

Forests

and

People

journalhomepage:www.elsevier.com/locate/tfp

An

approach

to

assess

actors’

preferences

and

social

learning

to

enhance

participatory

forest

management

planning

Marlene

Marques

a ,∗,

Manuela

Oliveira

b,

José G.

Borges

aa Forest Research Center, School of Agriculture, University of Lisbon, Tapada da Ajuda, 1349-017 Lisboa, Portugal

b Department of Mathematics and Research Center in Mathematics and Applications, University of Évora, Colégio Luís António Verney, Rua Romão Ramalho 59, 7000-671 Évora, Portugal

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Keywords:Participatory approach Forest management models Ecosystem services Preferences ranking Opinion change Social learning

a b s t r a c t

Forestmanagementplanningisoftenchallengedbytheneedtoaddresscontrastingpreferencesfromseveral actors.Participatoryapproachesmayhelpintegrateactors’preferencesanddemandsandthusaddressthis chal-lenge.Workshopsthatencompassaparticipatoryapproachmayfurtherinfluenceactors’opinionsandknowledge throughsocialinteractionandfacilitatethedevelopmentofcollaborativelandscape-levelplanning.Nevertheless, thereislittleexperienceofformalassessmentofimpactsofworkshopswithparticipatoryapproaches.This re-searchaddressesthisgap.Theemphasisisonthedevelopmentofanapproach(a)toquantifyactors’preferences forforestmanagementmodels,post-firemanagementoptions,forestfunctions,andecosystemservices;(b)to assesstheimpactofparticipatorydiscussionsonactors’opinions;and(c)toevaluatetheeffectofsocial interac-tionontheactors’learningandknowledge.Themethodologyinvolvesaworkshopwithparticipatoryapproach, matchedpre-andpost-questionnaires,anon-parametrictest,theWilcoxonSigned-ranktestforpairedsamples, andaself-evaluationquestionnaire.

WereportresultsfromanapplicationtoajointforestmanagementareainValedoSousa,inNorth-Western Por-tugal.Findingssuggestthatworkshopandparticipatorydiscussionsdocontributetosocialknowledgeand learn-ingaboutforestmanagementmodels.Actorsdebatedalternativesthatcanaddresstheirfinancialandwildfire risk-resistanceconcerns.Also,duringtheparticipatorydiscussions,actorsexpressedtheirinterestin multifunc-tionalforestry.Thesefindingsalsosuggestanopportunitytoenhanceforestmanagementplanningbypromoting landscape-levelcollaborativeforestmanagementplansthatmaycontributetothediversificationofforest man-agementmodelsandtotheprovisionofawiderrangeofecosystemservices.However,moreresearchisneeded tostrengthenthepre-andpost-questionnaireapproach,givingmoretimetoactorstoreflectontheirpreferences, toimprovemethodsforquantifyingsociallearningandtodevelopactors’engagementstrategies.

1. Introduction

Forestmanagement entailsarangeof actorswithdifferent inter-ests,preferences,andopinions.Consequently,therearedistinctideas abouthowtheforestshouldbeplannedandmanaged(Cowling et al., 2014 ).Theparticipatoryinvolvementoftheseactorsatanearlystage ofplanningandinallitsstepsisbecomingincreasinglyimportantfor forestmanagement(Cowling et al., 2014 ; Martins and Borges, 2007 ; Reed, 2008 ).Participatoryprocessesprovideinformationthatcanhelp forest managers anddecision-makers understand actors’ preferences and expectations and thus develop tailored plans and policies, in-creasingtheirsocialacceptanceandsustainability(Balest et al., 2016 ; Carmona et al., 2013 ;Kangas et al., 2006 ;Sarva š ová et al., 2014 ). Sev-eralstudiesreport theimportance oftheassessment andintegration

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddresses:marlenegm@isa.ulisboa.pt(M.Marques),mmo@uevora.pt(M.Oliveira), joseborges@isa.ulisboa.pt(J.G.Borges).

ofactors’interestsandconcernsinforestmanagementprocesses(e.g., Borges et al., 2017 ;Bruña-García and Marey-Pérez, 2018 ;Maroto et al., 2013 ;Nordström et al., 2010 ).

Moreover, the literature reports the application of participatory techniques to assess actors’ preferences for forest management and ecosystem services. For example, Sarkissian et al. (2018) explored the stakeholders’ preferences toselect native tree species according toconservationpriority andecologicalsuitabilityforreforestation in Lebanon, while Focacci et al. (2017) evaluated stakeholders’ prefer-ences for firewood, timber, non-wood forest products, tourism and recreation, hydrogeological protection,landscape contemplation and nature,andairqualityconservation,inacasestudyinSouthernItaly. Rossi et al. (2011) evaluatedthepreferencesofforestlandownersfor selectedforestmanagementtreatmentpracticesofferedunderthe

pro-https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tfp.2020.100026

Received10June2020;Receivedinrevisedform9August2020;Accepted13August2020 Availableonline17August2020

M. Marques, M. Oliveira and J.G. Borges Trees, Forests and People 2 (2020) 100026

Table1

Levelsofactors’involvementinparticipatoryapproaches.

Level of involvement Description

Participatory techniques

(examples) Pros Cons

Information Information provided to actors aiming to assist them in understanding the problem, the alternatives, the opportunities and/ or solutions

• Newsletter and press releases • Reports • Presentations, public hearings • Internet webpage • Low cost

• Limited resources and logistics

• Fast to inform large audience • Lack of new information • Absence of actors’ interaction • Controlled disclosure of information

Consultation Two-way flow of information to gain feedback on analysis, alternatives and/ or decisions and respond feedback • Interviews • Questionnaires and surveys • Workshop • Cognitive map • Qualitative and/ or quantitative primary information collected in a short time • Easy to compare data

during the analysis

• Only ask for opinions and not involve actors in decision-making • Bias may appear in data if not effectively supported and conducted

Collaboration Joint activities with actors engaged in problem solving and the development of proposals • Workshop with participatory discussions • Focus group • Multicriteria analysis • Scenario analysis • Consensus conference • Interaction among actors • Depth discussions • Broader perspectives • Boost actors’ engagement • Increased consensus and understanding of other actors’ points of view

• Limited number of actors

• Actors time demand • Need an experienced

facilitator with expertise • It can be expensive • Lack of willing to talk

openly

Co-decision Collaboration where there is shared control of decision making

Empowerment Transfer of control of level of decision making

• Workshop • Focus group • Consensus conference

• Give actors the sense of ownership

• Actors not interested in implementing the decision

AdaptedfromBrescancinetal.(2018);Cowlingetal.(2014);Luyetetal.(2012)

gram “Southernpine beetlepreventioncost-share” to improvestand health in six statesof USA. Kant and Lee (2004) analyzed four for-eststakeholdergroupspreferencesfortenaggregatedforestvaluesin NorthwesternOntario,Canada.

Engagingactorswithdifferentpreferences,opinions,and expecta-tionsinparticipatoryapproachescanenrichforestmanagement plan-ning.Additionally,thiscollaborationimprovestherelationshipsamong actorsanddecision-makers,promotinginformeddecisions, understand-ing, trust, andsocial learning (Blackstock et al., 2007 ; Reed et al., 2010 ; Voinov and Bousquet, 2010 ). Furthermore, actors’ collabora-tionis differentaccordingtotheirlevel ofinvolvementin participa-toryapproaches.Itisacontinuumofactorinvolvement,frompassive disseminationofinformationtoactiveengagementandempowerment (Arnstein’s, 1969 ;Reed, 2008 )withprosandcons(Table 1 ). Accord-ingtotheliterature(Howard, 1980 ;Lafon et al., 2004 ),participatory approachesthatinvolveactiveparticipation(e.g.,workshops and fo-cusgroupswhereparticipantsexpressthemselvesandparticipatein dis-cussions)appeartoinfluenceactors’opinion,learningandknowledge morethanpassiveparticipationwithindirectinvolvement(e.g., read-ing,hearingalecture,attendingmeetingswithoutspeakingup).

Inthelistdifferentparticipatorytechniquesforactorinvolvement (Table 1 ),likequestionnairesandsurveys,cansupportforest manage-mentplanningbygatheringqualitativeand/orquantitativeinformation aboutactors’preferences. Thistechnique hasseveralinteresting fea-tures.Firstly,itisanaffordableandexpeditiousmethodofcollecting data;secondly,itallowsactorstoremainanonymous,maximizingtheir comfortandencouragingmoresincereresponses;thirdly,itisnottoo time-consuming;andfourthly,itsdataprocessingisfasterwhen com-paredwithinterviewsormulticriteriadecisionanalysis.Thus,asurvey questionnaireisaneasyapplicationtoolthatcanassistdecision-makers togetfastprimarydata.

Furthermore,thepre-andpost-surveytechniquecanhelpassessthe impactofparticipatoryapproachesonactors’opinionsandknowledge. This techniqueconsistsof twostages. Anidenticalsurveytool(e.g., questionnaire)isusedbefore(pre-survey)andafter(post-survey)a

par-ticipatory assessment(e.g.,meeting,workshop, fielddemonstration). Afterward,participants’answerstobothsurveysarestatistically com-paredtoquantifythedifferencesandcheckwhetheropinionchanges tookplace.AccordingtoSmith (1994) ,actors’opinionsandinterestsdo notchangerapidlyorunpredictably,andyettheymayindeedchange. Thus,timeis neededbetween thepre-andthepost-questionnaireso thatparticipantscanthinkandreflectabouttheinformationprovided. However,accordingtosomeapplicationsintheframeworkofnatural resourcesmanagement,theperiodtoreflectbeforepost-surveycanvary fromonedaytomorethanoneyear.

Forexample,Upton et al. (2019) appliedpre-andpost-surveysto confirmthesuccessfulimpactofathinningdemonstrationin impart-ing knowledgeto forestowners. Theyrespondedthe post-survey18 monthsafterthedemonstration.Lafon et al. (2004) appliedthis method-ology toevaluatetheinfluence ofactiveparticipation on stakehold-ers’knowledgeandopinionsregardingwildlifemanagement.Thetime interval between thepre- andthepost-questionnaire was aboutone year. Mayer et al. (2017) conducted three participatoryworkshops, over afour-monthperiod. Theauthorsappliedthepre-questionnaire onthefirstdayofthefirstworkshopandthepost-questionnairewas administeredatthelastworkshop(afterfourmonths).Likewise,they verifiedthattheparticipatoryworkshopsimpactedparticipants’ abil-ities on modelingandtheir beliefson utility andaccuracyof water resources systems models. During a five-dayworkshop, Fatori ć and Seekamp (2017) confirmedthatpolicypresentationsandvalue-based deliberationsaboutclimatechangeadaptationofculturalresourcesnot onlyinfluencedparticipants’opinionsandunderstandingbutalso en-hancedtheirsociallearning.Theauthorsappliedthepre-questionnaire priorthefirstworkshopsession(firstday)andthepost-questionnaire afterthelastworkshopsession(fifthday).Canfield et al. (2015) found thataone-daydeliberativeforum(orworkshop)wasusefulinshifting participants’perceptionsabouttheimportanceof climatechange but didnotsignificantlyinfluenceobjectiveknowledgeorenergypolicies tomitigateandadapttoclimatechange.Participantsansweredthe pre-questionnairewhentheyarrivedattheforumandcompletedthe

post-M. Marques, M. Oliveira and J.G. Borges Trees, Forests and People 2 (2020) 100026 questionnaireattheendoftheevent.Ashworth et al., 2013 ;Ooi and

Tan, 2015 andRobles-Morua et al., 2014 alsoreporttheuseofpre-and post-questionnairesinaone-dayworkshop.Basedonformercontacts andinteractionswiththeactors(Marques et al. 2020 )wedeemedthat aone-dayworkshopwouldbesuitableforthisresearch.

Nevertheless,toourknowledge,thepre-andpost-survey methodol-ogyhasnotyetbeenusedinaforestmanagementplanningframework toanalyzetheactors’preferencesaswellasopinionchangeandsocial learning.Thisresearchaimsataddressingthisgap.Itismotivatedby thefactthatthequantificationoftheactors’preferencescanprovidea firstoverviewoftheactors’perceptionsandopinionsrelatedtoforest managementandtheprovisionofecosystemservices.Moreover, assess-ingtheinfluenceof aparticipatoryapproachonactors’opinionsand sociallearningcanindicatewhetherin-depthdiscussionsorthe appli-cationoffurtherparticipatorytechniquesareneededtoaddress misun-derstandingsorthelackofinformationtosupportforestmanagement decisions.Furthermore,itcanbeanopportunityforforestmanagersand policymakerstoassesshowactorsperceivealternativestocurrentforest managementpractices.

Thisresearchencompassesthusthreeobjectives.Firstly,itaimsat collectingprimarydataabout(a)actorsforestmanagementplanning preferencesforforestmanagementmodels,post-firemanagement op-tions,forestfunctions,andecosystemservices,byaquantitativesurvey approach(individualquantitativeinformation);and(b)actorsopinions andpointsofviewbyparticipatorydiscussions(groupqualitative infor-mation).Secondly,itaimsatevaluatingtheimpactofthepresentations andparticipatorydiscussionsontheactors’forestmanagement prefer-encesandopinions.Thirdly,itaimsatassessingtheeffectofsocial inter-actionduringtheworkshopontheactors’learningandknowledge.The methodologytoaddresstheseobjectivesinvolvesaworkshopwith par-ticipatoryapproach,matchedpre-andpost-questionnairesanda non-parametrictest,theWilcoxonSigned-ranktestforpairedsamples,and aself-evaluationquestionnaire.

2. Materialandmethods

2.1. Casestudyarea

Weappliedourapproachtoajointforestmanagementarea(ZIF)in ValedoSousa,inNorth-WesternPortugal(Fig. 1 ).Itisaforested land-scapeextendingover14,840ha,whereeucalypt(Eucalyptusglobulus La-bill),andmaritimepine(PinuspinasterAiton),inbothpureandmixed stands,arethepredominantspecies.Theforestownershipismostly pri-vateandfragmentedintosmallforestholdings.Therearesome commu-nityareasmanagedbythelocalparishcouncils.TheZIFhas360forest ownersasmembers.WildfireshavebeenfrequentandsevereinValedo Sousa.Overtheperiodfrom2005to2017,theareaburnedextended uptoof14,798hainValedoSousa(ICNF, 2019 ).Theyearswiththe largestburntareawere:2005(5383ha,36.3%ofthetotalarea)and 2017(4006ha,27.0%ofthetotalarea).

ValedoSousaischaracterizedbymultipleactors’interestsandhigh relevanceofeconomicforestresources.Previousresearch(Borges et al., 2017 ;Juerges et al., 2017 ;Marques et al., 2020 )revealedactors’keen interestsinwoodprovisioning,particularlyeucalyptpulpwood,aswell asinwildfireriskreduction.Themultiplicityofdecision-makers,aswell asthemultitudeofecosystemservices,makeValedoSousaan interest-ingtestcaseforourapproach.

2.2. Researchdesign

Weimplementedpre-andpost-questionnaires,i.e.,weusedidentical questionnairesintwostepstoassessandanalyzetheactors’preferences andopinionchangesoverafull-dayworkshop.Theevaluationofthe presenceanddirectionofopinionchangeenablesustoanalyzeifand howinformationanddiscussionsduringtheworkshopcaninfluence

ac-tors’opinions(Fatori ć and Seekamp, 2017 ;Lafon et al., 2004 )aswell associalknowledgeandlearning(Reed et al., 2010 ).

2.2.1. Questionnairesstructure

Thequestionnairetoimplementthepre-andpost-surveywaswere designedbaseduponareviewofpreviousstudiesonthe characteriza-tionoftheforestmanagementcontextinValedoSousa(Borges et al., 2017 ;Juerges et al., 2017 ;Marques et al., 2020 ).Thepre-and post-questionnairesweredividedintothreethematicparts,andencompassed atotalofninequestions,foranestimated10-minutesresponse.Itaimed tocollectquantitativeinformationtargetingtheelicitationof prefer-ences.Itdidnotaskforajustificationofactor’spreferences(qualitative information).However,alllistsofPartsIIandIIIallowedactorstoadd otherunlistedfeatures.

PartIcollectedactors’personalinformation,suchasforestwork ex-perience.Wealsoaskedactorstoindicate,fromalist,thetypeofforest managementactortowhichtheybelonged.Next,PartIIfocusedon for-estmanagement.Itincludedquestionsaimingattheelicitationofactors’ preferences.Specifically,theywereasked(a)toranksix forest man-agementmodels(FMMs)accordingtotheirpreferences;(b)topropose aforestareadistributionofValedoSousabytheFMMs(percentage); (c)toranktenforestmanagementpost-fireoptionsaccordingtotheir preferences;and(d)toselecttwopreferredforestfunctionsfromalist ofseven.PartIIItargetedtheelicitationofpreferencesforecosystem services,rankingalistofeightbyorderofimportance.Intheranking questions,weaskedactorstorankinfrom“mostpreferred” to“least preferred”.

Inaddition,westructured aself-evaluationquestionnaireusinga 5-pointLikertscale(“veryweak” to“verystrong”)foranestimated 5-minutesresponse.Thisquestionnairedirectlyaskstheactorsa)to eval-uatethelevelofimportanceoftheirparticipationandotheractorsin thediscussionsduringtheworkshop;andb)toappraisewhether pre-sentationsanddiscussionsinfluencedtheiropinionandknowledge.

AllthequestionnaireswereimplementedinPortuguese.Toprevent questionnairebiasandmisinterpretation(Choi and Pak, 2005 ),we de-signedandstructuredallthequestionsusingsimplewording,e.g., avoid-ingambiguousandcomplexquestions,technical jargon,and uncom-monwords.Moreover,thequestionnaireswerepre-testedbythree re-searchers.

2.2.2. Actors

Tofacilitatethediscussionbytheactors,theworkshopwasnot an-nouncedtothepublicbutrestrictedtoinvitedactors.Furthermore,we builtfrompastresearch(Integral Future-Oriented Integrated Manage- ment of European Forest Landscapes, 2015 )aswellasmorerecent stud-ies(Juerges et al., 2017 ;Marques et al., 2020 )toidentifyandinvite46 actorsrepresentingdifferentinterestsinforestmanagement(Table 2 ).

Ofthe46invitedactors,atotalof33actorsattendedtheworkshop andcompleted thepre-questionnaire(71.7%). However,only 24 ac-torsoutofthese33completedthepost-questionnaire(Table 2 ).Nine of33actorswerenotavailabletoparticipateintheworkshopallday. Attheendoftheday,21actorsansweredtheself-evaluation question-naire.Theinvitedactorscomprisedabroadlyrepresentativesampleof interests(Rowe and Frewer, 2000 )forforestmanagementinValedo Sousa(Table 2 ).Thus,wecategorizedtheactorsintofourgroups accord-ingtotheirinterestsinforestmanagement(Juerges and Newig, 2015 ; Marques et al., 2020 ).

2.2.3. Workshop

Twomonthsbeforetheworkshopdate,wesentaninvitationemailto actors,explainingtheeventobjectivesandaskingto“savethedate”.One monthbeforetheworkshop,wecontactedactorsbyphone,reinforcing theinvitation,explainingtheagenda,andaskingforconfirmationof at-tendance.Thefinalagendawassentthreeweeksbeforetheworkshop.A weekbefore,wecalledagainactorswhohadnotconfirmedtheir partic-ipationyet.TheworkshopwasheldinNovember2017,anditextended

M. Marques, M. Oliveira and J.G. Borges Trees, Forests and People 2 (2020) 100026

Fig.1. LocationofValedoSousacasestudyarea.

Table2

Identificationoftheactorsinvitedtotheworkshopandwhoansweredthe ques-tionnaires,categorizedbyinterestgroup.

Interest group and type of actor

Invited to the workshop

Questionnaire

pre- post- evaluation

Civil society 7 6 4 3 Environmental NGO 4 3 1 2 Forest certification 3 3 3 1 Forest owners 17 12 6 6 Forest owners’ association 3 3 1 1 Forest owners (non-industrial) 11 7 5 5

Parish council with community areas 3 2 0 0 Market agents 16 10 10 8 Biomass industry 1 0 0 0 Forest investment fund 2 1 1 1 Forest services provider 2 1 1 1 Forest services provider and wood buyer 3 3 3 3 Wood industry 4 3 3 3 Wood industry association 4 2 2 0 Public administration 6 5 4 4 Forest authority 3 3 2 2 Municipality 3 2 2 2 Total 46 33 24 21

overonedayinthecityofPorto.Wechosethislocationbecauseitis closetoValedoSousa,about30min’drive,andiswheremostactors liveorwork.

Inordertofacilitatethediscussionbytheactorsduringthe work-shop,wesetupthetablestocreatealargeU-shapeallowingallactorsto beabletoseeatalltimes(a)eachother;(b)thespeakers(researchers); and(c)thediscussionfacilitators.Duringtheworkshop,weconducteda pre-andpost-questionnaire.Wedistributedthepre-questionnaireafter awelcomemessageandabriefintroductiontotheworkshopgoalsand agenda.Westressedthatquestionsfocusedonforestmanagementinthe ValedoSousacasestudyarea– thepre-questionnaireincludedamap ofitonitslastpage.

Aftertheactorscompletedthepre-questionnaire,twopresentations weremade.Thewayinformationispresentedcaninfluencedecisions andsocialknowledge.So,speakers(researchers)triedtousesimple dis-courseandpresentations.Thefirstpresentationfocusedonactor anal-ysisoftheforestmanagementcontextinValedoSousa(Juerges et al., 2017 ;Marques et al., 2020 ).Itincludedacharacterizationof(a)actors interestsforforestmanagementandecosystemservices;(b)influential actorsinforestmanagementdecisions;(c)mainconflicts ofinterests andproblems;(d)powerresourcestoinfluencetheforestactors’ deci-sions(Marques et al. 2020 ).Thesecondpresentationcharacterizedthe contributionofstand-levelFMMstotheprovisionofecosystemservices availableinValedoSousa.Forthatpurpose,itincluded(a)ashort de-scription– e.g.,regeneration,fueltreatmentandthinningoptions, rota-tionages– ofcurrentFMMs(mixedmaritimepineandeucalypt,mixed eucalyptandmaritimepine,purechestnutandpureeucalypt)andoftwo proposalsofalternativeFMMs(puremaritimepineandpure peduncu-lateoak);and(b)agraphicalcomparisonoftheprovisionofecosystem

M. Marques, M. Oliveira and J.G. Borges Trees, Forests and People 2 (2020) 100026 services(e.g.,biodiversity,carbonsequestration,culturalservices,resin,

waterquality,wildfiresresistance,wood)byeachFMM.

Then,twofacilitatorsencouragedaparticipativediscussionofthe informationprovided.Theparticipatorydiscussionsaimedtocollect ac-tors’opinionsandpointsofview,i.e.qualitativeinformation,thatcan complementandsupportthequantitativeinformationfromthepre-and post-questionnaires.Thefacilitatorshadpreviousmediationexperience inparticipatorydiscussions,andtheywereknowledgeableaboutVale doSousa forestmanagementissuesandactorsprofilesandinterests. Theytriedtoconductthediscussioninanindependent,impartial,and unbiasedway(Rowe and Frewer, 2000 ).Thefacilitatorsaskedactors tospeakopenlyandfreelyinorderto(a)identifydifferentperspectives onforestmanagementinthecasestudyarea;(b)checkpointsofview andopinionsontheFMMspresented;and(c)discusstheintegrationof moreFMMsthatcanmeetactors’expectationstoimproveforest man-agementplanning.Thefacilitatorsaimedasharedunderstandingofthe forestmanagementplanningoptionsandopinionsandnotnecessarilya consensus.

Theactorsansweredthepost-questionnaireafterlunchatthe begin-ningoftheafternoonsession.Attheendoftheday,weaskedactors torespondtotheself-evaluationquestionnairetargetingtheassessment oftheirparticipationaswellasofothers.Weassignedeachactoran alphanumericcodetolinktheactors’pre-andpost-questionnaire re-sponsesandsothatanswerswereanonymous.

2.3. Dataanalysis

Weconducted a statistical analysisusing the software IBMSPSS Statistics,version25(Armonk,NY:IBMCorp.),tounderstandand com-parepreferences andchoices.Weestimatedstatistics onlyforthe24 matchedpre-andpost-questionnaires.First,weuseddescriptive statis-ticstosummarizetheactors’characteristicsandprofiles.Next,we de-velopedastatisticalanalysisofthefrequenciestomultiple-choice ques-tions.

Then,weconsidered ranksasordinaldataandapplied statistical teststoidentifyshiftsinrankingsaswellastoexplorewhetherthe dif-ferencesobservedinthesamplewerestatisticallysignificant.Weuseda 5%valueasareferencevalueforhypothesistesting,meaningwe estab-lishedtheinferencewithanerrorprobabilityoflessthan5%.Since sam-plesizewascomparablylowandweworkedwithcategoricalfigures, andastheT-testisusedforlargersampleswithnormaldistribution,we resortedtothenon-parametricWilcoxontesttoassessdifferences be-tweentworepeatedmeasurements(pre-andpost-questionnaire).The WilcoxonSigned-ranktestforpairedsamplesstatesthehypotheses:

H0:Thedistributionofthevariablevaluesatbothtimes(pre-and post-questionnaire)isequal.

H1: The distribution of variablevalues atbothtimes (pre- and

post-questionnaire)isdifferent.

Whentheproofvalueishigherthan5%,thenullhypothesisisnot rejected,i.e.,therearenostatisticallysignificantdifferencesbetween thetwopairsofmeasures.Otherwise,whentheproofvalueislessthan 5%(𝛼 <0.05),thenullhypothesisisrejected,andthealternative hy-pothesisisaccepted;thatis,therearestatisticallysignificantdifferences betweentwopairsofmeasures.Werankedtheresultsaccordingtothe post-questionnaire.Inthecaseofatiebetweenthemeans,weusedthe standarddeviationtorankit(i.e.,themeanwithlowerstandard de-viationwasrankedhigher).Asthesamplesizebyinterestgroupwas verysmall(fourto10actorspergroup)weonlyappliedtheWilcoxon Signed-ranktesttothesetof24matchedpre-andpost-questionnaires. 3. Results

3.1. Actors’profile

About54.2%oftheactorshadprofessionalexperienceinforestry orhadheldforestproperties forover20years(Table 3 ).Only8.4%

of theactorshadlessthannineyearsof experience-theybelonged tothegroupofMarketagents.WoodindustryactorsfromtheMarket agents’group(20.8%oftotalactors)managedanarealargerthan100 ha.Nevertheless,mostforestownersmanageanarearangingfrom2to 50ha.

ThefragmentationanddispersionofforestblocksaretypicalinVale do Sousa.About 50%of forestownersmanagelessthanfiveblocks. Still,33.3%managebetween10and100blocks.InthecaseofMarket agents,30.0%managemorethan150blocks.Actorsmanagepure eu-calypt(26.7%)andmixedeucalyptandmaritimepine(10.2%)FMMs. Mostoftheactorswhomanageforestareasstatedtheywillingnessto converttheareaofmaritimepineandeucalyptusstandstootherspecies (e.g.,chestnut),incasethereisfinancialcompensation.

3.2. Forestmanagementmodels

In thepre-questionnaire (Table 4 ), on average,preferences were higherforPuremaritimepine(M=4.88,SD=1.57)andMixed euca-lyptandmaritimepine(M=4.79,SD=1.91).Thelowerpreferencewas forOtherforestmanagementmodel(M=2.17,SD=2.10),withactors identifyingasalternativemodels:“NativemixedforestsandRiparian galleries”,“Mixedbroadleavesstandswithcorkoakandbirch”,“Pure poplar”,“Mixedstandswithredoak”,“Broadleavesstands” and“Pure stonepine”,eachforoneactor.

Onaverage,inthepost-questionnaire(Table 4 ),theactorsmaintain theirpreferenceforPuremaritimepine(M=4.88,SD=1.62),followed byPureeucalypt(M=4.63,SD=2.30).Thelowerpreferenceremained forOtherforestmanagementmodel(M=2.79,SD=2.55).Fouractors listed“Corkoak(pureormixedwithotheroaks)”,whiletwoactors pro-posed“Mixedbroadleaves”,oneactorsuggested“Nativemixedforests andRipariangalleries”,andoneactorindicated“Purepoplar”.

Thep-valueislessthan5%forthedifferencesbetweenthepre-and post-questionnaireforOtherforestmanagementmodel(Table 4 ). There-fore, thenullhypothesisis rejectedandacceptedthealternative hy-pothesis. ThepreferenceforOtherforestmanagementmodelincreased significantlyfromthepre-tothepost-questionnaire,withstatistically significantdifferencesobserved(Z=-2.200,p=0.028).Whileinthe pre-questionnairesixFMMswereproposedbysixactors,inthe post-questionnaire theproposals weremoreconsensual, sincefourFMMs wereproposed byeightactors.Thecork oakFMMwas proposedby one actoronthepre-questionnairewhile itwasproposed byfourin thepost-questionnaire.However,thedirectionofactors’preferencesdid notchangesignificantlyinthecaseoftheremainingFMMs,sincethe

p-valueishigherthan5%forthedifferencesbetweenthepre-and post-questionnaire,indicatingstrongevidenceforthenullhypothesis.

Regarding the distribution of the area by FMM, in the post-questionnaire, actorsassociated ahigher percentagetoPureeucalypt

(M = 34.63%,SD =31.66%) andPure maritime pine(M = 15.46%, SD=15.68%)(Table 4 ).

For the Other forest management model, in the pre-questionnaire (M=4.96%,SD=12.26%),theactorssuggested“Nativemixedforests, andRipariangalleries”,“Purepoplar” and“Mixedbroadleavesstand”, each by one actor. While in the post-questionnaire (M = 13.92%, SD=19.47%),fouractorsproposed“Corkoak”,threeactorsspecified “Mixedbroadleaves”,oneactorstated“Nativemixedforestsand Ripar-iangalleries” andoneactorlisted“Purepoplar.

Frompre-topost-questionnaire,thepercentageofforestarea associ-atedwiththemodelsPureeucalypt(Z=-2.190,p=0.029)andOther for-estmanagementmodel(Z=-2.737,p=0.006)increasedsignificantly.By contrast,thepercentageofforestareadecreasedsignificantlyfrom pre-topost-questionnaireforthemodelsMixedeucalyptandmaritimepine

(Z=-2.045,p=0.041)andPurechestnutmodels(Z=-2.333,p=0.020). Actorsmaintaintheirpreferencesabouttheforestareaassociatedwith theremainingthreeFMMs,sinceitdidnot changesignificantly(p>

M. Marques, M. Oliveira and J.G. Borges Trees, Forests and People 2 (2020) 100026

Table3

Profileofrespondentactorsbyinterestgroup.

Characteristics All actors ( n = 24) Interest group Civil society ( n = 4) Forest owners ( n = 6) Market agents ( n = 10) Public administration ( n = 4) (% of n) Experience (years) < = 4 4.2 0.0 0.0 10.0 0.0 5 – 9 4.2 0.0 0.0 10.0 0.0 10 – 14 16.7 25.0 16.7 0.0 50.0 15 – 19 20.8 25.0 16.7 30.0 0.0 > = 20 54.2 50.0 66.7 50.0 50.0

Forestland managed (ha)

< 2 4.2 25.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 [2 - 5[ 8.3 0.0 16.7 0.0 25.0 [5 - 20[ 16.7 0.0 50.0 10.0 0.0 [20 - 50[ 8.3 0.0 16.7 10.0 0.0 [50 - 100[ 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 > = 100 20.8 0.0 0.0 50.0 0.0 Not applicable ∗ 41.7 75.0 16.7 ∗∗ 30.0 75.0 Number of blocks < 5 20.8 25.0 50.0 0.0 25.0 [5 - 10[ 4.2 0.0 0.0 10.0 0.0 [10 - 50[ 8.3 0.0 16.7 10.0 0.0 [50 - 100[ 12.5 0.0 16.7 20.0 0.0 [100 - 150[ 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 > = 150 12.5 0.0 0.0 30.0 0.0 Not applicable ∗ 41.7 75.0 16.7 30.0 75.0

Forest management model (% of the total area managed)

Pure maritime pine 6.3 0.0 3.3 13.0 0.0

Pure eucalypt 26.7 0.0 35.0 43.0 0.0

Pure chestnut 0.2 0.0 0.0 0.5 0.0

Pure oak stand 1.5 0.0 3.3 1.5 0.0

Mixed of maritime pine and eucalypt 3.1 3.8 2.5 4.5 0.0

Mixed of eucalyptand maritime pine 10.2 12.5 18.3 0.5 25.0

Other forest management model ∗∗∗ 7.0 8.8 20.8 0.9 0.0

Shrubs 3.4 5.0 0.0 6.1 0.0

Not applicable ∗ 41.7 75.0 16.7 30.0 75.0

∗Actorswhodonotmanageforestland ∗∗ForestOwners’Association

∗∗∗Strawberrytree,corkoak,planetrees,walnuttree,redoak,Douglasfir,andcedars.

Duringtheparticipatorydiscussions,oneactorfromthePublic Ad-ministrationgroupproposedcorkoakasanalternativeFMM.Several actorsexpressedtheiragreement,generatingaveryparticipative discus-sionabouttheadvantagesofthecorkoak,namely,toprovidearegular income,andasasolutionfordryareas.InPortugal,thecorkoakisused toproducecork.Although,someactorsmentionedthatitcouldalsobe implementedasacoppicesystemtoproducebiomass.Thisoptionwas alsodiscussedforthepedunculateoak,astherotationageisverylong. Actorsreferredthatitisverydifficulttoconvinceforestownersplant specieswithextendedrotations,sothecoppicesystemmaybeattractive asitcontributestoanticipateincome.

Throughoutthediscussion,therewasaconsensusamongtheactors thattheFMMswithextendedrotationswouldbehardtoimplementin ValedoSousaduetotheoccurrenceofwildfires(thefirerecurrence pe-riodisabouttenyears).Actorsagreedabouttheimportanceofriparian broadleavesasanalternativeFMMforthewaterlines.Actors empha-sizedthatariparianFMMcanpromotediscontinuityinthelandscape andmake itmore resistanttowildfiresand,atsametime,fosterthe biodiversityinecologicalcorridors.

Discussionshadastrongfocusoneconomicimportanceof FMMs andhowitsprofitabilityisparamounttoforestownersandmanagers (e.g.eucalyptandmaritimepineFMMs).Forestmanagersstressedthat modelsshouldbeadjustedforshortenrotationstoaddressthewildfire recurrenceperiod.ActorsfromtheMarketAgentsgroupmentioned fur-therthatthepineindustrypreferswoodaged30-35.Inaddition,some forestownersreportedahighmortalityofchestnutstandsinValedo Sousa.So,thisFMMdoesnotrankhighintheirpreferences.

3.3. Forestmanagementpost-fireoptions

Inthepre-andpost-questionnaire(Table 5 ),theactors’preferences forforestmanagementpost-fireoptionswerehigher,on average,for

Increasing thediversity of forestspecies(pre-questionnaire: M = 8.88, SD=2.59;post-questionnaire:M=9.00,SD=2.36)andWaitingfor natural regeneration (pre-questionnaire: M = 7.50, SD = 3.04; post-questionnaire:M=7.21,SD=3.08).

Inthepre-questionnaireforthequestionConvertingtheexisting for-estmanagementmodel(M=4.29,SD=3.81),actorssuggestedeleven conversionoptions.Twoactorsproposed“Plantingotherbroadleaves” whiletheoptions“Foreststandswithshrubmosaics(e.g.,strawberry tree)”,“FMMfor natureconservation”,“Modelingatlandscape scale with areas for production, conservation, and ecological corridors”, “Agroforestrymosaicswithmixedbroadleavesstands”,“Grazing,mixed profitableandmulti-purposeforeststands”,“Forestlandconsolidation (parceling)”,“Coercing landowners tojoin in reforestation”, “Model thatincludesprofessionalmanagement”,“Recreationalandcultural ser-vices” and“Coppicestands” wereproposedeachbyoneactor.Astothe questionOtherpost-fireoption(M=2.71,SD=3.17)actorsproposed sevenoptions:“(Re)establishingnativemixedforests”,“Restoringand plantingcorkoak”,“Poplarstandin riparianareas”,“Decreasing the areaofmonocultureforests”,“Followingtherequirementsoftheforest certificationprocess”,“Creatingroadanddivisionalnetwork appropri-atetothescaleandsizeoftheproperty” and“Otheruses(ex.: agricul-ture)” eachbyoneactor.

Thesamenumberofconversionoptionswereproposedinthe post-questionnaireforthequestionConvertingtheexistingforestmanagement

M. Marques, M. Oliveira and J.G. Borges Trees, Forests and People 2 (2020) 100026 Table4

Pre-andpost-questionnaireresultsanddifferencesofpreferencesforforestmanagementmodelsanditsareadistribution(n=24).Rankaccordingtothe post-questionnaire.

M. Marques, M. Oliveira and J.G. Borges Trees, Forests and People 2 (2020) 100026 Table5

M. Marques, M. Oliveira and J.G. Borges Trees, Forests and People 2 (2020) 100026 model (M= 5.08, SD = 3.97) namely:“Other broadleaves”, “Mixed

broadleaves”,“Cork oak”, “Nativemixed species (or in combination withinterestingexoticspecies)”,“Nativeandriparianforest”,“Mixed maritimepinetopuremaritime pine”,“Maritimepinerevolutionsof 25to30yearsoldatmost”,“Modelfornatureconservation”, “Prof-itableandsustainableforestspecies”,“Forestlandconsolidation (parcel-ing)”, “FMM that includes professionalmanagement”, each for one actors. However, for the question Other post-fire option (M = 1.58, SD=1.84),actorsproposedthreeoptions:“Pastures,agricultureand others”,“Poplarstandinriparianareas”,and“AnysustainableFMM”, eachbyoneactor.

ThepreferenceforOtherpost-fireoptiondecreasedsignificantlyfrom thepre-questionnairetothepost-questionnaire,withstatistically sig-nificantdifferencesobserved(Z=-2.032,p=0.042).However,there wasnosignificantlyshiftinthedirectionoftheactors’preferencesfor theremainingforestmanagementpost-fireoptions,frompre-to post-questionnaire(p>0.05).

AccordingtoactoranalysisoftheforestmanagementcontextinVale doSousa(Juerges et al., 2017 ;Marques et al., 2020 ),wildfireriskwas consideredastheproblemthatcaninfluencemostforestmanagement decisions.Duringtheparticipatorydiscussionsession,forestmanagers reinforcedtheimportanceofthisproblemintheirdecisions.Some for-estownershavereportedthatthissituationhasdiscouragedthemfrom investinginforestmanagement.Theyalsoarguedthat,duetothehigh recurrenceofwildfires,theirforestmanagementpost-fireoptionsare relatedtolow-costoptions(e.g.waitingfornaturalregeneration). How-ever,forestmanagerswereconsensualinthepreferenceforspecies di-versificationandforamultifunctionalforestthatmayallowthemto(a) reducewildfirerisk;and(b)promotediversifyofitsforestryrevenues.

3.4. Forestfunctionsandecosystemservices

ActorsselectedWoodproduction(M=91.67%,SD=28.23%)asthe mostimportantforestfunctioninthepre-questionnaire(Table 6 ), fol-lowedbyCulturalservicespromotion(29.17%,SD=46.43%).Regarding thequestionOtherforestfunction(M=8.33%,SD=28.23%)oneactor identified“Forestjobscreationandmaintenance”.

Inthepost-questionnaire(Table 6 ),Woodproduction(M=75.00%, SD=44.23%) rankedalsofirst, followedbyWaterqualityprotection

(M=33.33%,SD=48.15%).AstothequestionOtherforestfunction

(M=12.50%,SD=33.78%),theanswersincluded“Watercycle regula-tion” and“Fireprevention”,eachbyanactor.However,thepreference forthefunctionWoodproductiondecreasedsignificantlyfromthe pre-tothepost-questionnaire(Z=-2,000,p=0.046).Fortheremaining for-estfunctionstheobserveddifferenceswerenotstatisticallysignificant (p>0.05)sinceactors’preferencesdidnotshiftsignificantlyfrom pre-topost-questionnaire.

Onaverage,inthepre-questionnaire(Table 6 ),thepreferred ecosys-temserviceswasWood(M=5.63,SD=2.86),followedbyWater Qual-ity(M=5.33,SD=2.12).Themostpreferredecosystemserviceisthe sameinthepost-questionnaire(M=6.42,SD=2.47),while Biodiver-sity(M=5.38,SD=1.72)rankssecond.Evenso,theobserved differ-encesfrompre-topost-questionnairewerenotstatisticallysignificant (p>0.05)foralltheecosystemservices.Actorsdidnotsignificantly changethedirectionoftheiropinionandmaintainedtheirpreferences forecosystemservices.

ThegraphicalcomparisonofecosystemserviceindicatorsbyFMM raisedseveralquestionsaboutthepossibilityofecosystemservices,in additiontowood,beingprofitable.Someactorswereunawareofthis possibility(e.g.carbonmarket).Furthermore,actorsfromPublic Ad-ministrationandCivilSocietyinterestgroupsstressedtheimportance ofdiversifyingtheforestfunctionsandecosystemservicestocontribute forasustainableforestmanagement. However,theprovision of non-marketservicesinthecasestudyareadependonthepossibilityof at-tractingpaymentsforthem.

3.5. Evaluationofactors’participationintheworkshop

Ofthe21actorswhorespondedtothequestionnaire, 33.3%had neverbeeninvolvedinparticipatoryapproaches,while14.3%had al-readybeen involvedmorethantentimes,42.9%hadbeen involved in twotofiveparticipatoryapproaches,and9.5%onlyonce. All ac-torsconfirmedtheirwillingnesstoparticipateinfuture participatory approaches.

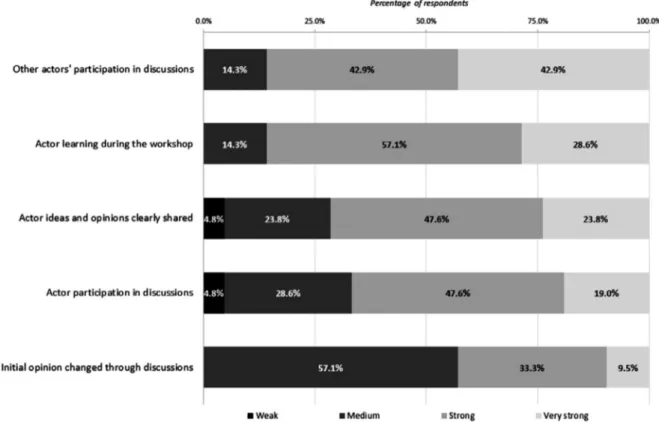

Theresults(Fig. 2 )highlightthatabout85.7%oftherespondents ratedOtheractors’participationindiscussionsasofstrongtoverystrong importance.Itrevealsthevalueofsocialinteractiontosharepointsof viewandopinions.Actorlearningduringtheworkshopwasalsohighly rated(85.8%strongtoverystrongimportance),indicatingthatthe in-formation availableandthediscussionscontributedtoactor’s under-standingandknowledge.

Regardingtheevaluationoftheirparticipation,around71.4%ofthe actorsindicatedthattheyhadbeenabletoclearlysharetheirideasand opinionsduringtheworkshop.Although,theratingoftheirParticipation indiscussionswassomewhatlower,about66.6%considereditstrongto verystrong.Lessthanhalfoftheactors(42.8%)indicatedstrongtovery strongimportancetochangesininitialopinionbecauseofthe discus-sion.Itmeansthattheremainingactorsconsideredthattheyslightly changedtheirinitialopinion(57.1%).Noactorratedanyoftheitems asofverylowimportance.Only4.8%ofactorsratedasoflow impor-tancesomequestions(ActorideasandopinionsclearlysharedandActor participationindiscussions).

Theworkshopdiscussionsandtheactors’commentsinthe evalu-ationquestionnairerevealedthatmostactorsconsideredthatthis ap-proachcontributedto(a)theirlearningfromtheinformationprovided; (b)theirdiscussionwithactorswhohaddifferentpreferencesinforest management,and(c)theirunderstandingofotheractors’opinionsand pointsofview.

4. Discussion

This approachwasnot intendedtomodelactors’opinions. More-over,wedidnotaimtoreachaconsensusonFMMs,forestmanagement post-fireoptions,forestfunctions,orecosystemservicestobe consid-eredinforestmanagementplanning.Theobjectivesweretoquantify actors’preferences,identifyalternativeFMMsandcapturethe multi-plicityofactors’pointsofview.ThefindingscansupportZIFmanagers betterorientforestmanagementplanning.Also,wesoughtto under-standiftheworkshopenvironmentleadsactorstochangetheiropinion andpromotessocialknowledgeandlearning.Themainadvantageof thisapproachistheeaseofapplicationanditstimeanddataprocessing costeffectiveness.

4.1. Actorspreferencesandopinionchange

Ingeneral,actors’preferencesandopinionsregardingcurrentforest managementdidnotchangesignificantlysincetheobserveddifferences arenotstatisticallysignificant(p>0.05).Also,theactors’evaluationof theirparticipationintheworkshopconfirmedthatmostofthemdidnot stronglychangetheiropinion.However,resultshighlightsomeopinion shiftsfrompre-topost-questionnairethatmaybeduetotheworkshop participatorydiscussionsandarenoteworthy.

Themainactors’preferencesforFMMswerefirstforPuremaritime pineandsecondforPureeucalypt.Inaddition,actorsassignedahigher percentageofareatothePureeucalyptmodel,whichincreased signifi-cantlyfrompre-topost-questionnaire,followedbyPuremaritimepine. These resultsconfirmandstrengthenthecurrent preferenceof forest managersforthesetwoFMMs.Besides,thesespeciesoccupy mostof theareainValedoSousa.Accordingtotheactorsopinionsduring work-shopdiscussions,thepreferencesforPureeucalyptandPuremaritimepine

M. Marques, M. Oliveira and J.G. Borges Trees, Forests and People 2 (2020) 100026 Table6

M. Marques, M. Oliveira and J.G. Borges Trees, Forests and People 2 (2020) 100026

Fig.2. Aggregateresults(n=21)ofactors’perceptionsabouttheirandothers’participationinworkshopdiscussions,measuredona5-pointLikert-scale(“veryweak” to“verystrong” importance).

(e.g.,eucalyptisharvestedevery10-12yearsandmaritimepineat 35-50years);(b)thewildfirerecurrenceperiod(abouttenyears);and(c) themarketdemand.ThroughoutdiscussionsactorsstressedthatFMMs withextendedrotationagesarenotattractivetoforestownersand man-agers.Further,actorsfromtheMarketAgentsgroupstatedthatmarket demandforpinewoodislessthan35years.Therefore,actorsrequired anadjustmentofthePuremaritimepineandPurepedunculateoakmodels toshortentherotationageandanticipaterevenues.

Duringthediscussions,someforestownersreportedahigh mortal-ityoftreesofPurechestnutmodel.Thissituationcanbecausedbyink disease(Phytophthoracinnamomic)orbychestnutcancer(Endothia par-asiticaAnd&And).Thissharingofinformationmayexplaintheactors’ opinionshiftontheareatobeallocatedtothismodel.Thepreferences forPurechestnutdecreasedsignificantlyfrompre-topost-questionnaire, changingfromthethirdpreferredFMMtotheleastpreferred.

Mostforestownersandmanagersdependontheforesteconomic returns,directlyorindirectly.Duringtheworkshopdiscussions,actors reinforcedthatoneofthemostimportantconcernsistheprofitability offorestryinvestment.Moreover,actorsrevealedtheimportancethey assigntothediversificationofincomesourcesandtotheevennessof revenueflows.Accordingtotheactors,inValedoSousa,theseeconomic criteriadependontheWoodproduction,classifiedasthemostimportant forestfunctionwhileWood isthepreferredecosystemservice.These findingsreinforcethepreferenceofactorsforWoodprovisioninginVale doSousa,asreportedbyBorges et al. (2017) ,Juerges et al. (2017) ,and Marques et al. (2020) .

Toachieveaprofitableandmultifunctionalforest,thatcanminimize thewildfireproblem,duringparticipatorydiscussions,actorsdebated theinclusionoftwoalternativesFMM:(a)corkoak(pureormixed); and(b)riparianbroadleaves.Discussionsaboutthesealternative mod-elsmayhave ledtotheactors’opinionshiftsincethepreferencefor

Otherforestmanagementmodelincreasedsignificantlyfromthepre-to thepost-questionnaire.Inthepre-questionnairethecorkoakFMMwas proposedbyasingleactorwhileinthepost-questionnaireitwas

pro-posedbyfouractors.Inaddition,forestmanagersemphasizedthat wild-firesmaydissuadethemfromchoosingspecieswithlongerrotationage. ActorsstressedthatthecorkoakFMMmaybeanadequatealternative torespondtoconcerns(namelywithincomeevenflowandwithlosses duetowildfires)thatinfluenceforestmanagementdecisionsinValedo Sousa.Besidesthecorkoakregularityofincome(everynineyears),the actorsalsohighlightedthecorkoak’sexcellentabilitytoregeneratein thepost-fireconditionsinValedoSousa.

Anothernotableopinionshift,frompre-topost-questionnaire,was asignificantdecrease inpreferencefortheforestfunctionWood pro-duction. This opinionchangemaybe relatedtotheinformationthat speakers(researchers)presentedabouttherangeofavailableecosystem servicesandforestfunctionsinValedoSousa.Thegraphical compari-sonoftheavailableecosystemservicesbyFMMbroughtanewvision andhelpedpromotediscussionsaboutthepossibilityofdiversifying for-estfunctionsandecosystemservicesasthismaycontributetodecrease lossesbywildfires.Also,someactorsstressedtheimportanceofdiversify theforestfunctionsforasustainableforestmanagement.

DespitethefactthatactorscontinuetoconsiderWoodproductionas themostimportantforestfunction,thedecreaseintheirpreference ev-idenceawillingnesstochangecurrentforestmanagementpractices.In fact,duringtheparticipatorydiscussions,actorsexpressedtheirinterest inamultifunctionalforestry.Itappearedthatactorsareavailableto con-sideralternativeFMMsandtodiversifytheforestfunctionsand ecosys-temservicesinforestmanagementplanning.Forestmanagersinterested inprofitableforestswerenotopposedtoalternativeFMMs(e.g.riparian broadleaves),forestfunctions(e.g.,waterqualityprotection),or ecosys-temservices(e.g.,biodiversity)sincetheycanreceivepaymentsforthat forestmanagementchange.

ThesefindingssuggestanopportunityforZIFmanagerstoenhance forestmanagementplanning,sincethere isanopennessoftheforest managersto acceptchangestothe current forestmanagement prac-tices.Thisrevealsthatifmoreinformationisprovidedaboutscenarios involvingchangingsocialdemand,marketfluctuationsandwildfires

re-M. Marques, M. Oliveira and J.G. Borges Trees, Forests and People 2 (2020) 100026 currence,actorsmayadjusttheirpreferencestobetteraddressthenew

challenges.

4.2. Actorsknowledgeandsociallearningduringtheworkshop

Anevaluationquestionnaireshouldcomplementthepre-and post-questionnaireapproachtoassess(a)thequalityofworkshopand par-ticipatoryapproachanddiscussions;(b)theinteractionbetweenactors; (c)actors self-learningandknowledge. Mostactors statedthat they viewedthemselvesashavinglearnedduringtheworkshop,increasing theirknowledgeinasocialcontext.Moreover,theactorsacknowledged thatwiththeparticipatorydiscussionstheybetterunderstandthepoints ofviewofotheractorsregardingforestmanagement.Also,they high-lightedtheincreasedknowledgeofopportunitiesandalternativesto di-versifyforestfunctions,ecosystemservicesandFMMs,thattheymay considerinforestmanagementplanning.

Thus,thereisevidencethatinourapproachtheparticipatory dis-cussions contributed to social learning, confirming the findings by Reed et al. (2010) andVoinov and Bousquet (2010) .Mostactorsdidplay anactiveroleduringtheworkshop;theydiscussedforestryissuesand learnedwithsocialinteraction.Furthermore,theworkshopalso demon-strateditsutilityinimprovingtherelationshipsbetweenactors.Some evidenceofthissociallearningwastheinteractionsaftertheworkshop, withquestionsandrequestsformoreinformationrelatedtothe work-shopdiscussions.Forexample,twoforestowners,oneactorfromwood industryassociationandanotherfromforestcertificationcontactedus toaskformoreinformationaboutthealternativeFMMsandthe assort-mentofecosystemservicesinValedoSousa.Anotherexamplewasthe contactbyanactorfromtheforestauthoritywithwhomwediscussed theimprovementofthecorkoakFMMproposedduringtheworkshop discussionsession.

Theresultsfromtheapplicationofpre-andpost-questionnaireto actors’preferences forforestmanagement, canbecomparedtoother similarstudiesinnaturalresourcesmanagement.Asdemonstratedby thisresearch,theparticipatoryapproachthatinvolvessocialinteraction betweenactorscan(a)impacttheirknowledgeandlearning(Fatori ć and Seekamp, 2017 ;Mayer et al., 2017 ;Upton et al., 2019 );and(b)in somesituations,cancontributetoactorsopinionchange(Canfield et al., 2015 ;Lafon et al., 2004 ).

4.3. Participatoryapproachlimitationsandfutureimprovements

Theapplicationofthisapproachprovidedvaluableinformationthat maybe usedbyfutureresearch.Weidentifiedfiveissuestoaddress. Firstly,thetimeavailablefortheactorstointeractwithresearchersand todiscussamongthemmightbeextendedtosupportfurthertheir reflec-tionsandthelearningprocess.Thiswouldbeinfluentialtoexamine fur-therwhetherinforestmanagementplanning,opinionschangequickly orif,asSmith (1994) pointsout,actors’opinionsandinterestsdonot changerapidlyorunpredictably.

Inthisframework,infutureresearch,wemightapplythesame ques-tionnaireinfoursteps,toquantifyandconfirmtheimpactofthe work-shopandparticipatorydiscussionsinalong-timeframe.Inthefirststep, wewouldsendthepre-questionnairebyemailormailtotheactorsone weekbeforetheworkshopsothattheycouldexamine itcomfortably withouttheworkshopsocialenvironmenttimeconstraint.Inthe sec-ondstep,actorswouldanswerthepre-questionnaire inthefirst ses-sionoftheworkshop.Inthethirdstep,actorswouldrespondthe post-questionnaireattheendoftheworkshop.Andinthefourthstep,we wouldsendthepost-questionnairebyemailormailtotheactorsone weekaftertheworkshop,sothattheyhavemoretimetoabsorb, re-flectandthinkaboutalltheinformationprovidedbythespeakers (re-searchers)andtheparticipatorydiscussions.Thus,wecan comparea pre-questionnaireandtwopost-questionnairesandassesstheeffectof participatorydiscussionsandsocialinteractioninactors’initial

opin-ion,accordingtothetimegivenforreflection(onthedayandoneweek later).

Thedrawbackofthisfourstepsapproachcanbealowresponserate asoutsidetheworkshopenvironmentsinceitmaybemoredifficultto ensureactors’commitmentandavailability.Inaddition,itmaybe chal-lengingtoensurethatasuitablenumberofthesameactorsanswerthe threequestionnairessothatwemaygetmatchedquestionnaires.In or-dertocircumventpotentialshortcomingsofthefourstepsapproach,the questionnairesshouldbesenttoawiderangeofstakeholders,ensuring diversityandrepresentabilityofinterestgroups.Inaddition,follow-up workwiththeactorswillbenecessaryinthefirstandfourthsteps. Re-searchersshouldcontactactors,byphoneorinperson,tomotivatethem toanswerthequestionnaires,emphasizingtheimportanceoftheir par-ticipationinthestudy.

Secondly,infutureresearchthestructureofthequestionnairesmight beadjustedtoexplorefurthertheactors’pointsofview.Although ac-tors couldaddotherunlisted features,they hadlittletimetojustify theirpreferencesandexplaintheirperceptions.Also,notallactorsfeel comfortabletofreelyexpresstheiropinionsinparticipatorydiscussions. Thus,infutureresearch,wemayaddafieldtoeachquestionforactors toexpressthemselvesanonymously,withoutrestrictionsthatthesocial environmentmayimposeonthem.

Thirdly,futureresearchshouldaddressfurthertheweak participa-tionofsomeactorsinthediscussionandtheneedtostrengthentheir involvement.Therefore,weshouldidentifythemostpassiveorshy ac-torsandenhancetheirparticipationsothattheycanpresentandshare theirideasandopinions.Fourthly,futureresearchshouldaddressthe factthatactorswiththesameinterestsorfromthesameentityor inter-estgroupmayspeaktoeachotherandagreeonsomeresponsestothe questionnaires.So,toguaranteeindividualandindependentresponses, actors’seatsaredistributedinadvance,ensuringthatactorssittingside bysidehavedifferentinterests.Moreover,beforestartingtofillupthe questionnaire,theresearchercanreinforcethattheanswersare individ-ual.

Fifthly,futureresearchshoulddevelopstrategiestoensuresufficient actorsforstatisticalanalysis,assuringtherepresentativenessof inter-ests.Weidentifiedandinvited46actorsrepresentingthediversityof interestsinforestmanagementinVale doSousa.Actorswere catego-rized intofourgroups,accordingtotheirinterests inforest manage-ment(Juerges and Newig, 2015 ; Marques et al., 2020 ):civilsociety, forestowners,marketagentsandpublicadministration.Knowingatthe outsetthatnotallactorswouldbeavailabletoparticipateinthe work-shop,weinvitedmoreactors(46actors)thanwethoughtitwouldbe interestingtohavepresent(30to35actors).Although13actorswere notavailabletoattend,thosewhoparticipatedintheworkshopwere representativeofthefourinterestgroupsfromValedoSousa.However, only24actorswereavailabletoattendthefulldayworkshop.So, fur-therresearchisneededtodevelopandexplorestrategiesforengaging moreactorsintheparticipatoryapproaches.Thiswillbeinfluentialto drawmoreinformationfromtheperspectiveofeachgroup.

5. Conclusions

Thisstudyprovidesinformationaboutactors’preferencesandpoints of viewtosupportlandscape-levelforestmanagementplanning.Itis thefirstevaluationofactors’preferencesforFMMs,forestfunctionsand ecosystemservicesforValedoSousa.Ourfindingsrevealtheimportance ofinvolvingactorstodiscussalternativestocurrentforestmanagement practices.

ValedoSousaforestmanagementplanningencompassedfourFMMs andthreespecies,eucalypt,maritimepineandchestnut.Inthe work-shop,researchersproposedtwoalternativeFMMs(Puremaritime pine

andPurepedunculateoak),thatwerewellacceptedbytheactors. How-ever,theyaskedforanadjustmenttotheseFMMstoshortentherotation ageandanticipaterevenues.Animportantoutcomefromthis participa-toryapproachwastheinclusionoftwonewalternativeFMMs-Cork

M. Marques, M. Oliveira and J.G. Borges Trees, Forests and People 2 (2020) 100026 oakandRiparianbroadleaves-inforestmanagementplanninginVale

doSousa.Duringparticipatorydiscussionsactorsconsideredthatthese twomodelsaresuitableforValedoSousaastheymeettheireconomic goals(incomeflow)andenvironmentalconcerns(biodiversityand wild-fireprotection).Duetodiscussions,actorschangedtheiropinionabout thesealternativeFMMs,andtheirpreferenceforthemincreased signifi-cantlyfrompre-topost-questionnaire.Withthisparticipatoryapproach, wewentfromfourtoeightFMMs,thuscontributingtodiversifythe for-estmanagementoptionsinValedoSousa.

Theintegrationofactors’preferencesandparticipatorydiscussions outcomesfromthisstudyinZIFforestmanagementplanningcan(a) fa-cilitateitssocialacceptanceandimplementation;(b)thedevelopment ofmoreconsensualforestmanagementplans;and(c)contributeto en-hanceactors’knowledgeandlearning.Theproposedapproachcanbe easilyappliedorreplicatedin otherZIF orforestmanagementareas. Thissystematiccollectionofinformation(quantitativefrom question-nairesandqualitativefromparticipatorydiscussions)maybeusefulto supportZIFmanagers,whendevelopingcollaborativeforest manage-mentplans,orpolicymakers,whendesigningeffectiveforestpolicy pro-gramsthatcanaddresstheactors’demandsandpreferences.Moreover, commentsbyactorsreportedintheself-evaluationquestionnaire con-firmedthattheyfoundtheworkshopandparticipatorydiscussions use-ful.Thisapproachenablesactorstoenhancetheirknowledgeaboutthe rangeofFMMs,forestfunctionsandecosystemservicesthatcan pro-moteamultifunctionalandsustainableforestry.

Thesurveyofactors’preferencesforforestmanagementusing pre-and-post-questionnairesisauseful,practical,low-cost,and straightfor-wardwayforevaluatingtheiropinionsandperceptions.However, fur-therresearchcanimprovethisapproachby(a)givingactorsmoretime toreflectintheirpreferencesandchoices(beforeandafterworkshop); (b)askingactorstojustifytheirpreferencesinquestionnairessowecan betterunderstandtheiropinionchange;(c)assessingthesociallearning usinganevaluationquestionnairewithmorequestionstoquantifyit; (d)extendingtheworkshoptoabroaderinterestgroups;and(e) devel-opingstrategiestoattractmoreactorsandmotivatethemtoparticipate intheworkshopthroughouttheday.

Thisresearchwasdevelopedintheframeworkofaparticipatory pro-cessthatis beingdevelopedwithactorswithinterestsin forest man-agementof Vale doSousa. Inthenext stageof the processwe will take advantage of theactor analysis research (Juerges et al., 2017 ; Marques et al., 2020 )andtheresultsfromthisworkshopwitha partici-patoryapproachtodevelopfurthertheassessmentofactors’preferences applyingotherparticipatorytechniquesintheframeworkofmultiple criteriadecisionanalysis.

DeclarationofCompetingInterest

Theauthorsdeclarethattheyhavenoknowncompetingfinancial interestsorpersonalrelationshipsthatcouldhaveappearedtoinfluence theworkreportedinthispaper.

Acknowledgments

ThisresearchhasreceivedfundingfromtheEuropean Union’s Hori- zon 2020 ResearchandInnovationProgrammeundergrantagreement No.676754 withthetitle‘Alternativemodelsforfutureforest manage-ment’(ALTERFOR),aswellasfromtheproject LISBOA-01-0145-FEDER-030391-PTDC/ASP-SIL/30391/2017withthetitle‘Forestecosystem managementdecision-makingmethods-anintegratedbio-economic ap-proachtosustainability’(BIOECOSYS).Theauthorswouldliketothank theFundaçãoparaaCiênciaeaTecnologia(Portugal)forfundingthe Ph.D.grantof MarleneMarques(PD/BD/128257/2016)andfor sup-porttheForestResearchCenterProjectUIDB/00239/2020.Wewarmly thankall theactorswhohaveparticipatedin theworkshopand an-sweredthequestionnaires.WewanttothankCarlosCaldasandSusete Marquesfortestingthequestionnaires.

Disclaimer

Responsibilityfor the informationandviews setout in this arti-cle/publicationliesentirelywiththeauthors.

References

Arnstein, A. , 1969. A ladder of citizenship participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 26, 216–233 . Ashworth, P., Einsiedel, E., Howell, R., Brunsting, S., Boughen, N., Boyd, A., Shackley, S.,

Van Bree, B., Jeanneret, T., Stenner, K., Medlock, J., Mabon, L., Ynke Feenstra, C.F.J., Hekkenberg, M., 2013. Public preferences to CCS: how does it change across coun- tries? Energy Procedia 37, 7410–7418. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2013.06.683 . Balest, J., Hrib, M., Dob š inská, Z., Paletto, A., 2016. Analysis of the effective stakeholders’

involvement in the development of National Forest Programmes in Europe. Int. For. Rev. 18, 13–28. doi: 10.1505/146554816818206122 .

Blackstock, K.L., Kelly, G.J., Horsey, B.L., 2007. Developing and applying a frame- work to evaluate participatory research for sustainability. Ecol. Econ. 60, 726–742. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.05.014 .

Borges, J.G., Marques, S., Garcia-Gonzalo, J., Rahman, A.U.U., Bushenkov, V., Sot- tomayor, M., Carvalho, P.O., Nordstrom, E.M., Nordström, E.-M., 2017. A multiple criteria approach for negotiating ecosystem services supply targets and forest owners’ programs. For. Sci. 63, 49–61. doi: 10.5849/FS-2016-035 .

Brescancin, F., Dob š inská, Z., De Meo, I., Š álka, J., Paletto, A., 2018. Analysis of stake- holders’ involvement in the implementation of the Natura 2000 network in Slovakia. For. Policy Econ. 89, 22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2017.03.013 .

Bruña-García, X., Marey-Pérez, M., 2018. Participative forest planning: How to obtain knowledge. For. Syst. 27, 1–11. doi: 10.5424/fs/2018271-11380 .

Canfield, C., Klima, K., Dawson, T., 2015. Using deliberative democracy to identify energy policy priorities in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 8, 184–189. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2015.05.008 .

Carmona, G., Varela-Ortega, C., Bromley, J., 2013. Participatory modelling to sup- port decision making in water management under uncertainty: two comparative case studies in the Guadiana river basin. Spain. J. Environ. Manag. 128, 400–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.05.019 .

Choi, B.C.K. , Pak, A.W.P. , 2005. A catalog of biases in questionnaires. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2, 1–13 .

Cowling, P., DeValue, K., Rosenbaum, K., 2014. Assessing Forest Governance. A Practical Guide to Data Collection, Analysis, and Use. PROFOR and FAO. Washington DC. Fatori ć, S., Seekamp, E., 2017. Evaluating a decision analytic approach to climate change

adaptation of cultural resources along the Atlantic Coast of the United States. Land Use Policy 68, 254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.07.052 .

Focacci, M., Ferretti, F., De Meo, I., Paletto, A., Costantini, G., 2017. Integrating stakehold- ers’ preferences in participatory forest planning: a pairwise comparison approach from Southern Italy. Int. For. Rev. 19, 413–422. doi: 10.1505/146554817822272349 . Howard, G.S. , 1980. Response-Shift Bias. A problem in evaluating interventions with

pre/post self-reports. Eval. Rev. 4, 93–106 .

ICNF 2019. Defesa da Floresta Contra Incêndios. Incêndios Rurais: mapas. Instituto da Conservação da Natureza e das Florestas. Retrieved from www2.icnf.pt/portal/florestas/dfci/inc/mapas (accessed September 17, 2019). Integral Future-Oriented Integrated Management of European Forest Land-

scapes, 2015. Reference to reports and research papers available in http://www.integral-project.eu/project-outcomes.html (html).

Juerges, N., Krott, M., Lundholm, A., Corrigan, E., Masiero, M., Pettenella, D., Makrick- ien ė, E., Mozgeris, G., Pivori ū nas, N., Lynikas, M., Brukas, V., Arts, B., Hoogstra-Klein, M., Laar, J. van, Borges, J.G., Marques, M., Carvalho, P.O., Canadas, M.J., Novais, A., Mendes, A., Sottomayor, M., Pinto, S., Brodrechtova, I., Smre ček, R., Bahýľ , J., Bo š ela, M., Sedmák, R., Tu ček, J., Lodin, I., Ba ş kent, E.Z., Karahalil, U., Karakoç, U., Sari, B., 2017. Internal Report on actors driving forest management in selected European countries. ALTERFOR project. Reference to reports and Research Papers available in https://alterfor-project.eu/

Juerges, N., Newig, J., 2015. How interest groups adapt to the changing forest governance landscape in the EU: a case study from Germany. For. Policy Econ. 50, 228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2014.07.015 .

Kangas, A., Laukkanen, S., Kangas, J., 2006. Social choice theory and its applica- tions in sustainable forest management-a review. For. Policy Econ. 9, 77–92. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2005.02.004 .

Kant, S., Lee, S., 2004. A social choice approach to sustainable forest management: an analysis of multiple forest values in Northwestern Ontario. For. Policy Econ. 6, 215– 227. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2004.03.005 .

Lafon, N.W. , Mcmullin, S.L. , Steffen, D.E. , Schulman, R.S. , 2004. Improving stakeholder knowledge and agency image through collaborative planning. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 32, 220–231 .

Luyet, V., Schlaepfer, R., Parlange, M.B., Buttler, A., 2012. A framework to implement Stakeholder participation in environmental projects. J. Environ. Manag. 111, 213– 219. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2012.06.026 .

Maroto, C., Segura, M., Ginestar, C., Uriol, J., Segura, B., 2013. Sustainable Forest Management in a Mediterranean region: social preferences. For. Syst. 22, 546–558. doi: 10.5424/fs/2013223-04135 .

Marques, M., Juerges, N., Borges, J.G., 2020. Appraisal framework for actor interest and power analysis in forest management - Insights from Northern Portugal. For. Policy Econ. 111, 14. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2019.102049 .

Martins, H., Borges, J.G., 2007. Addressing collaborative planning meth- ods and tools in forest management. For. Ecol. Manag. 248, 107–118. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2007.02.039 .

M. Marques, M. Oliveira and J.G. Borges Trees, Forests and People 2 (2020) 100026 Mayer, A., Vivoni, E.R., Kossak, D., Halvorsen, K.E., Morua, A.R., 2017. Participatory

modeling workshops in a water-stressed basin result in gains in modeling capacity but reveal disparity in water resources management priorities. Water Resour. Manag. 31, 4731–4744. doi: 10.1007/s11269-017-1775-6 .

Nordström, E.M., Eriksson, L.O., Öhman, K., 2010. Integrating multiple criteria decision analysis in participatory forest planning: experience from a case study in northern Sweden. For. Policy Econ. 12, 562–574. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2010.07.006 . Ooi, P.C., Tan, M.T.T., 2015. Effectiveness of workshop to improve engineering stu-

dents’ awareness on engineering ethics. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 174, 2343–2348. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.01.898 .

Reed, M.S., 2008. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: a literature review. Biol. Conserv. 141, 2417–2431. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2008.07.014 . Reed, M.S., Evely, A.C., Cundill, G., Fazey, I., Glass, J., Laing, A., Newig, J., Parrish, B.,

Prell, C., Raymond, C., Stringer, L.C., 2010. What is social learning? Ecol. Soc. 15, 10. doi: 10.5751/ES-03564-1504r01 .

Robles-Morua, A., Halvorsen, K.E., Mayer, A.S., Vivoni, E.R., 2014. Exploring the applica- tion of participatory modeling approaches in the Sonora River Basin, Mexico. Environ. Model. Softw. 52, 273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2013.10.006 .

Rossi, F.J., Carter, D.R., Alavalapati, J.R.R., Nowak, J.T., 2011. Assessing landowner preferences for forest management practices to prevent thesouthern pine beetle: an

attribute-based choice experiment approach. Forest Policy Econ. 13 (4), 234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2011.01.001 .

Rowe, G., Frewer, L.J., 2000. Public participation methods: a framework for evalua- tion. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 25, 3–29. doi: 10.1177/016224390002500101 , T4 - A Framework for Evaluation M4 - Citavi.

Sarkissian, A.J.A.J., Brook, R.M.R.M., Talhouk, S.N.S.N., Hockley, N., 2018. Using stake- holder preferences to select native tree species for reforestation in Lebanon. New For. 49, 637–647. doi: 10.1007/s11056-018-9648-2 .

Sarva š ová, Z., Dob š inská, Z., Š álka, J., 2014. Public participation in sustain- able forestry: The case of forest planning in Slovakia. IForest 7, 414–422. doi: 10.3832/ifor1174-007 .

Smith, T.W., 1994. Is there real opinion change? Int. J. Public Opin. Res. 6, 187–203. doi: 10.1093/ijpor/6.2.187 .

Upton, V., Ryan, M., Heanue, K., Dhubháin, Ní, 2019. The role of extension and forest characteristics in understanding the management decisions of new forest owners in Ireland. For. Policy Econ. 99, 77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2017.09.016 .

Voinov, A., Bousquet, F., 2010. Modelling with stakeholders. Environ. Model. Softw. 25, 1268–1281. doi: 10.1016/j.envsoft.2010.03.007 .