l

I-Jrban

challenges

in spuif

/ßrp'¡*

and

Portugal

T6s1

qEdited

by

Nuria

Benach and Andrés

Walliser

Êl

Routledqe

$\

raytorarran.iióroupFirst published 2014

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York,

Ny

10017Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa busíness @ 2014 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved' No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any lorm or by any

electronic, mechanical' or other

-.unr,

no* known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and reco-rding' or in any inlormation storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from thepublishers.

Trademark notice:Ptodtcf or corporate names may be trademarks

or registered tra<iemarks, and are used only for identification and explanãtion without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in publirction Data

A catalogue record lor this book is available lrom the British Library

ISBNI 3: 97 8-0-41 5-70s55-4 Typeset in Times New Roman by Taylor & Francis Books

Publisher's Note

The publisher accepts responsibility lor any inconsistencies that may have arisen during the conversion of this book from.iournal articles to book chapters, namely the possible

iti"rurl.r

ÁilÀr-ài

ter-inology.Disclaimer

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders ficr their permission to reprint

material ìn this book. The publishers wo-uld be grateful to

h.eali;T

any copyright rrot¿e. wrro is nãi tä..'u"Lno*ledged and willundertake to rectify any errors or omissions in luíure eáitions of this book.

Contents

Citation Information

1.

Introduction: Urban problems and

issuesin

contemporary

Spanish

and

Portuguese citiesNuria

Benqch andAndrés

Wctlliser2.

Subversionof

land-useplans and

thehousing bubble

in

Spain EugenioL.

Burriel

3.

The

processof

residential sprawl

in

Spain:

Is

it

really

a problem?Arlinda

Garcíq-Coll

4. Catalysing

governancein

aparadoxical

city:

the

Lisbon

StrategicCharter

and theuncertainties

of political

empowerment

in

the

Portuguesecapital

city

João

Seixas5. Area-based

initiatives and urban

dynamics.The

caseof

the Porto

city

centreJosé

A.

Rio Fernandes6.

The five

challengesof

urban rehabilitation. The Catalan

experienceOriol Nel'lo

7.

Urban

governance and regenerationpolicies

in historic aity

centres:Madrid

and

BarcelonaIsmael Blanco,

Jordi

Bonet andAndres

Wqlliser 8. EpilogueAndrés Walliser

andNuria

BenøchIndex

vll

6 24 38 59 82 100 118 120Citation

Information

The

chapters

in

this book

were

originally

published

in

Urban

Researchand

Practice,volume

4,

issue3 (November

2011).When

citing this

material,

please usethe original

page

numbering

for

eacharticle,

asfollows:

Chapter

1Introduction to

the special issue: urbanproblems

qnd

issuesin

contemporary

Spønishand Portuguese cities

Nuria

Benachand Andrés Walliser

Urban

Research andPractice, volume 4,

issue 3(November

2011)pp.227231

Chapter

2Subversion

o/

land-useplans

and the housing bubblein

SpainEugenio

L.

Burriel

(Jrban Reseørch and

PracÍice, volume 4,

issue 3(November

20ll)

pp.232-249

Chapter

3The process oJ'residential

sprawl

in

Spain:

Is

it

really

a problem?Arlinda

García-Coll

(Jrbøn Research and

Practice, volume 4,

issue 3(November

2011)pp.250

263 Chapter 4Catalysing

governancein

a

paradoxical

city:

the

Lisbon Strategic

Charter

and

theuncertainties of

political

empowermentin

the Portuguesecapital

city

João

SeixasUrban

Research andPractice, volume 4,

issue 3(November

20ll)

pp-264-284

Chapter

5Area-based

initiatives

and urbøn dynamics. The caseof

thePorto

city

centreJosé

A.

Rio

FernandesUrbøn Research and

Practice, volume 4,

issue 3(Novembet

20ll)

pp.285

307Chapter

6The

Jive

challengesof

urbanrehabílitation. The

Catalan experienceOriol Nel'lo

URBAN CHALLENGES IN SPAIN AND PORTUGAL

Lisbon

were an ongoing metropolitan sociospatial fragmentation (after three decadesof

demographic haemorrhaging unparalleled

in

European urbanhistory); the

slow paceof

urban regenerationofneighbourhoods,

with little

capacityto

attract bothpublic

andpri-vate investment; the need

to

reconfigure the arrayofpolicies

directedto

social inclusionand cohesion; the need to reframe

thinking

on the challenges posed to thecity

core basisof

urban competitiveness and employment; the wide array

of

environmental andsustainabil-ity

challenges; the need toput into

practice new typeofregulation,

fiscalpolicies,

urbaninstruments and administrative practices; and

the

needto

rethink

and restructure mostof

theinstitutional

and administrative structuresof

local

government. Irrespectiveof

thePortuguese capital

city

continuing to be undoubtedly the main national social, cultural andeconomic driver, notwithstanding the new urban-driven sociocultural paths clearly evident

in

dimensionslike

the housing market and international tourism, and despite severalinno-vative policies and attitudes undertaken by

public

entities and by private andcivic

actors,the

city

has experiencedin

the last decades majordifficulties

to face up growing pressingchallenges. The most recent economic crisis, keenly

felt

in

Portugal, revealed aboveall

acrisis deeply

felt in

the governmental andpolicy

orientations, thus producingin

Lisbon astronger recognition towards a shift on its urban

political

dimensions.Second" there was a parallel recognition that an important part of the

inability

to developnew

sociopolitical

and administrative responses was dueto

a conjunctionof

rigidity

anddisorientation

in

severalpolitical

andinstitutional local

and regional structures. Despitebeing the location

ofmajor

sociopolitical and cultural stakeholders, Lisbon paradoxicallyfaces the exhaustion

of

important partsof

its

classicalpolitical

administration landscapeand a recognized level

of publicly

driven ineffectiveness. For too long, many publicpoli-cies and attitudes continued to lack long-term rationality and merit, being mainly driven by

short-term

political

projects and corresponding closedpolicy

and bureaucratic communi-ties. As considered laterin

this text, this situation has been increasingly recognized-

anddebated

-

by a broadmajority

of the city's urban society and its main stakeholders.Third

by

a steady developmentof

a newcivic

consciousness and exigencyin

Lisbon society,paralleling the

changesin

civic

andpolitical

attitudesoccurring

in

most

con-temporary urban societies(Clark

andHoffman-Martinot

1998) and more specificallyby

what

has been developingin

the

Mediterranean urbanworld

reducing

the

traditionalnorth-south cultural

gapsofcivic

assertiveness and social capital(Leontidou

2010). As confirmed by researchers, and notwithstanding somç relevant elements such as theconsid-erable sociospatial fragmentation or the deterioration

oftraditional

associative institutionslike

corporate and labour unions,the

sociocultural capitalof

Lisbon

society-

analysedand understood through new forms and dynamics

of civic

awareness and involvement-

isrevealing an overall growing and acknowledged activity, namely when considering several

urban-driven topics (Cabral et

a|.2008,

Seixas 2008).It

was thuswith

a considerable doseof

social expectation that the newpolitical

teamsand programmes

resulting

from

the last municipal

elections addressedthis

demandingbackground.

Along

with

thepowerful new

leadership thenewly

electedmunicipal

teamincluded several new elements. These included some recognized non-party independents

and several new types of proposals already contained in the winning

political

programmenamely the commitment towards the reform of the

city

government and several newstrate-gic

instruments and processes (such as the revisionofthe

general urbanistic plan, a new housing strategy, a new culture strategy and a complete financial recovery plan). Followingfrom

thesepolitical

perspectives, a proposalfor

a strategic charterfor

thecity

was thenasked

for

and developed.Catalysing

governance

in

a

paradoxical

city:

the

Lisbon

Strategic

Charter

and the

uncertainties

of

political

empo\ryerment

in

the

Portuguese

capital

city

João Seixas

Institute ofSocial Sciences, University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal

This article describes and reflects upon the most recent sociopolitical strategic

pro-posals set to the political and governmental dimensions of the city of Lisbon. In this

framework, a specific process is detailed: directly requested by the president of the

Municipality, in 2009 an independent commissariat developed a proposal for a strategic

charter for the city. This proposal addresses a wide range ofareas, including the

polit-ical and institutional ones (through several governing principles with corresponding

rationales and proposed lines ofaction). A critical analysis (all but closed in the present

phase where the proposals are still under public discussion) is made ofthis specific

pro-cess and some of its correspondent contents. The analysis is supported by theoretical

reflections on urban politics, following the changes and the growing paradoxes

-

bothat the level of urban systems and in terms of the new governing dilemmas presently

emerging in the European cities. The text seeks in this sense to contribute to a better analytical clarity for urban politics and urban administration. As state-of-the-art for the

political developments in Lisbon, reflections are made upon the networks of

administra-tion, governance and sociocultural capital in the city. The final part ofthe article reflects

on the present stalemate in the charter process, thus dcriving some overall reffections

with reference to contemporary urban politics.

Introduction

At

the beginningof

2009,following

recentmunicipal

elections andin

parallel

to

somewide-ranging strategic initiatives, the president of the Lisbon

municipality

António Costa-a

political

leaderwith

considerable national relevancel-

asked for a group ofindependentexperts and urban thinkers

to

develop a proposalfor

a future strategic charterfor

the city.As stated at the time, the charter was to function as the base

for all

the different new localpolicies and strategic plans and instruments to be developed as

well

asfor

a new typeof

attitude towards the

city

and the citizens-

on this basisit

was expected that,in

the long term, there would be a considerableshift

in city

government,in

urbanpolicy

andin

therationales

of

local public administration.The

initiation

of

this

process emergedfrom

several backgrounds.First,

a

growing recognitionof

thenew type

of

challengesconfronting the city,

extendingthrough

sev-eral types of sectors and dimensions and demanding public and socio-economic responses

URBAN CHALLENGES IN SPAIN AND PORTUGAL

The

slowrepositioning of urban Europe

European cities have been (re)positioning themselves at a

historical

crossroads moment.The changes and restructurings occurring in their fluxes, densities and landscapes, as

well

as

in

their

cognitive

andcultural

dimensions, areproducing new

typesof

urbanpres-sures and challenges. These developments pose fundamental challenges to

their

classicalsociopolitical urban contexts andare marked by parallel confrontations and pressures

from

main references

-

from higher time-spaceflexibility

andmodularity

of the economic andsociocultural chains;

to

the crisisof

the welfare state thatis raising

new typesof

socialneeds and exigencies.

These disruptive

times, conjoining the

heritageof

what

François Aschercalled

theFordist-Keynesian-Corbuosian paradigm (1995)

with

the development of hyper-territoriesconfiguring

meta-relationshipsand

increasinglycomplex functionalities

of

urban life,

work,

mobility

and

consumption,are framing

new

types

of

fluxes and

externalities,severely challenging the present

political

urban governmental and institutional arrays.Slowly, long-established sociopolitical structures and stakeholdings seem to be

under-going

changeby

urban transformations. Todayit

is widely

recognizedby

most

of

thepolitical,

sociocultural and academic communities thatthis

historical transformativesce-nario demands a reinterpretation

ofsociopolitical

structures and attitudes on urban politics,city

administration, urban governance andlocal

actor's stakeholding (Bagnasco and LeGalés 2000, Jouve 2003).

Concomitantly,

a

varied

soft

of

multiple new

urban-driven strategies,policies

andgovernmental reconfigurations have been under development, some

with

promising

andother

with

already confirmed results. Some other trends, however, have raised growing doubts over democratic procedures and the cost-benefit effectivenessof public

delivery.Nonetheless, what seems certain is that a wide array of new types of urban projects, urban

policies and urban interpretations are developing

in

European societies.A

varietyofnew

urban and local

institutional

structures are being created; different processesof

adminis-trative

deconcentration andpolitical

decentralization, some against significant obstacles,are

slowly

developing;different

arraysof

principles

andtools

for

urban strategy, urbanplanning

and evencivic

participation

andcivic

rights,

arebeing

tested and developed;political

and instrumental improvementsin

social engagement andcivic

particìpation arebeing

raised; more detailed andinfluential forms

of civic

and academic questioningof

urban sociopolitical regimes are widening.

Notwithstanding all these innovative processes, the last two decades have also revealed

relevant uncertainties and blockages,

particularly

when considering the general configu-rationsof

theinstitutional

arrays deployedin

thecity.

Evenfor

someof

the seeminglymost necessary

political

developments-

like

the creation of metropolitanpolitical

author-ities corresponding to the need

for

stronger governance commitments at scales necessaryfor urban collective regulation and action; or the need for new public actions in the face

of

misuse

of

resources and democratic procedures-

many urban societies have experiencedthat the pace

of

developmentin their

'real

cities'

is not being

matchedby

correspond-ing

developmentsin their 'sociopolitical cities'.

On the one hand, we have witnessed thegradual evolution

ofpost-fordist

urban policies-

and more recently the reconfigurationof

neo-liberal policies themselves-

which tended toprioritize

neo-Schumpeterian perspec-tives and to promote the entrepreneurship and competitiveness enforcements (Jessop 1994,Harvey 2001, Brenner 2004).

But,

on the other hand, some severe criticisms havedevel-oped on how

it

has been through these logics that structural changes have occurredin

thepolitical

arenas and agendas, remodellingwhole

structuresof

urbanpolitics

and raisingIJRBAN CHALLENGES IN SPAIN AND PORTUGAL

important questions around the potential deployment of main urban values such as equity,

social justice, even democracy.

European cities

-

and moreparticularly

southern European cities-

with

their

stake-holding

structures and dynamics-

have been under most recent sociopolitical pressurefor

several reasons (Seixas and Albet 2010):

(l)

By

new forms ofdysphasia experiencedby

European urban citizens.This

occursin

the tensions created between the new urban opportunities and experiencespro-vided

by

different cultural

and economic paradigms andthe growing

pressuresencountered

in

primary

elements such as employment, housing rents and socialinclusion.

(2)

By

a continual weakness of local governments in developing more negotiation andinnovation capacities, coupled

with

chronic

issues regardingfiscal

and financial support.Notwithstanding the regional

andlocal

decentralization processesfol-lowed

in

several countries, which have brought about-

with

debatable success-

agreater focus on intermediate and

local territorial

scales, theselocal

weaknessesare

contributing

to

the

enlargementof

gapsin

overall

policy

delivery,political

competences and sociopolitical empowerment.

(3) The

considerable sociospatialfragmentation

of

several European metropoles, largely causedby

economic stakeholding structures andby

corresponding effectson

the

urbanproduction

models, seems paradoxicallyto be

fragmenting

tradi-tional

modesof

urban governance andfomenting the

lossof

historical

organicprocesses

of

local political

stakeholding.In

fact, crucial

uncertainties remainregarding

local

governance configurationsand

strategies-

namely

in

southernurban societies, where social capital has always been complex and fractal,

highly

personalized

or

evenpopulist, and weakly oriented

to

collective

strategies or democratic accountability.(a) By

the

influence

of

EU territorial policies

and directives.

Theseare

becom-ing

increasingly relevant,in

both financial, symbolic

andpolitical

terms. To

alarge extent due

to

European directives,for

the

first

time national

strategiesof

countries such as Greece and Portugal have recognized

cities as

a main

assetfor

the

development and sustainability, thusraising their

political

and symbolic importance.(5)

Finally

and as already expressedwith

referenceto

Lisbon's contemporary society,by

the fact that

European urban cultures are experiencing thematuring

of

newforms

of

cosmopolitanism. Thesehighly

visible

transformations rangefrom

themost differentiated lifestyles to the most varied urban social movements and forms

of civic

expressionrapidly

moving towardsmuch

more sophisticatedforms

andcontents.

A

civic

and cultural panoramaframing

a newpolitical

culturethat

will

have a profound and long-term influence on the governance and

political

spheresofEuropean cities.

These paradoxical European urban scenarios are not at

all

clear

they seem to havewithin

them a wide array ofpossible future directions. On the one hand, a series

ofdiverse

oppor-tunities

for political

development and socio-economicequity

are expanding;but

on theother, these most challenging impasses seem to correspond

with

whatHenri

Lefébvre wasreferring

to

more than 40 years ago as thelong

periodof

disorientationwith

the

(then)URBAN CHALLENGES IN SPAIN AND PORTTJGAI,

Applied

theories oncontemporary urban politics

Urban politics comprehends a vast space in which there coexist quite different dimensions

ranging

from

national strongholds to localpolitical

communities, tocivic

neighbourhood responsibility, from metropolitan strategic planning to human resource administration andto

real estate and swap finance. Here, amidst the evolutionof

the formsof

dialogue andconflict

andof collective

strategy development, the understandingof

tendencies whereasmore

or

less sharedor

divided

political

spaces arebuilt

betweendifferent

urban açtors(between governmental and institutional organs themselves but also between these and the

various actors of

civil

society), poses major challenges and raises important questions.These perspectives emphasize the importance of taking into account the logics of urban

social dynamics, perceptions and identities

in

the strategies and practicesof

themultiple

actors and communities

living within

eachcity's

spaces andflows (Guerra

2002).The

recognition

of

whatthe literature

refersto

associal

andcultural

capital, as systemso/

action in

a city, questions the perspectives that urban policies are bound notonly to

spe-cific

urban designed or planned configurationsbut

are as much a result andreflux

of

its sociocultural and economic structures, but also to thecivic

and daily energies that leveragequotidian urban

life.

Nonetheless, the

inclusion of

these perspectives oncity politics

should be supportedby

the existenceof

a correspondingrationality

in

governance planning and managementitself,

thusimplying

the existenceof

dialogue, compromise and strategybuilding

struc-tures across several scales: spaces, instruments and mechanisms, both formal and informal,

through which

conflict

and cooperation fluxes are processedwith

considerableproximity

and the formation

of

interdependencies and partnerships is materializedwith

considerabledoses

ofobjectivity.

Comparative analytical studies

on

trendsin

Europeancities

(based on performancestandard indicators),

carried out

overthe

lasttwo

decades2 and unsurprisingly reveal aconsiderable correlation between urban qualification and

political

innovation and inclusion.The cities

with

the best performances and standards of qualityof life

and wealth have alsobeen those that,

in

different scenarios and scales fostered good levelsofinnovation in

thepanorama of their urban policies and in their own

political-institutional

frameworks.Through

their

observations on the experiences and transformations occurringin

realEuropean city-system scenarios and their corresponding sociopolitical urban systems,

var-ious social scientists have

put forward

conceptual proposalsto

interpret emerging urbanpolitical

structures and dynamics. There remains an open-ended range of issues that require more thorough examination,including

the reinterpretationof

therole of

the Statein

thecity

(Brenner eta|.2003);

the deepeningofthe

scope and practicesofurban

governance(Bagnasco and Le Galés 2000); the evolution

of city

values and principles(Borja

2003);the consolidation and strengthening of strategic planning; a whole array of possibilities

in

institutional and administrative reforms; greater attention to qualitative dimensions such as

the

quality of life, public

spaces, landscape and urban rhythms; spaces and processesfor

deeper citizen participation and community involvement; new perspectives on areas such as

the communitarian and cognitive local economy, or reflexive and citizen-driven urbanism.

In this

article, wewill

follow

a specific conceptual proposalfor

interpretingcontem-porary

city

politics-

anintelligibility

proposal which establishes a conjugation between adesirably systemic conceptual exercise and its transformational capacrty for concrete

gov-ernability

and sociopolitical action.ln

a clear allusion to thecity

as aliving

being-

or theurban system as an ecosystem, we propose the development of a systemic structuring both

for

thecity

system and for the citypolitical

system-

based on the classical assumptionof

the

polis

being understood as anumbilical

connection between the urbs and the civitas.URBAN CHALLENGES IN SPAIN AND PORTUGAL

Extending

these conceptual premises,interpreting

the

city

as

a

collective

systemand

following

theoretical proposalsfrom

Ferrão(2003)

and Seixas (2008), a theoretical structureis

proposedwith

three elements representing the body, fluxes andsoul

of

thecity-system and

of

the sociopolitical city-system-

the latter, comprising thecity of

insti-tutions

and organizations (body), thecity

ofgovernance (fluxes) and thecity ofcollective

sociocultural capital (soul).

This

structurewill

be the conceptual basefor

both the urbansociopolitical diagnosis and the consequent

critical

analysisofthe

Lisbon Strategic Charterprocesses and its contents (Figure 1).

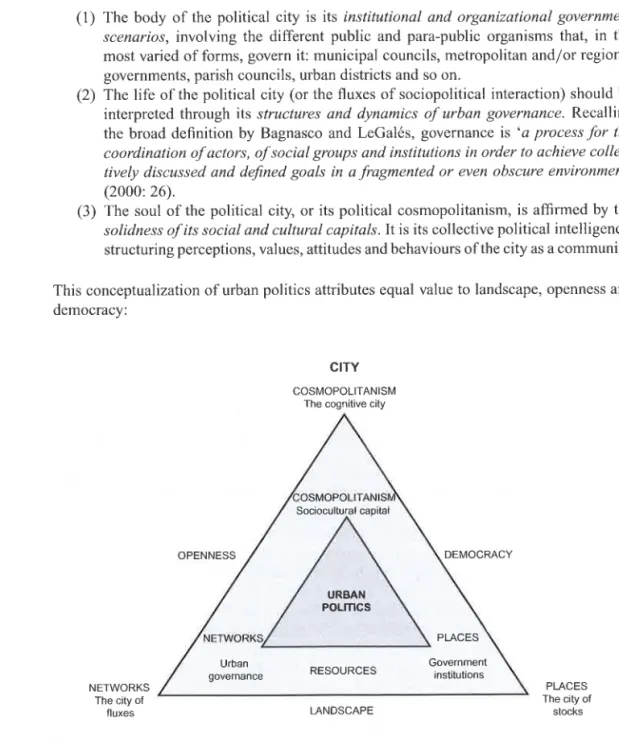

(1)

Thebody

of

thepolitical city is

its institutional

and organizational governmentscenarios,

involving the different public

and para-public organismsthat,

in

themost varied

of

forms, governit:

municipal councils,metropolitan

andlor regionalgovernments, parish councils, utban districts and so on.

(2)

Thelife

of

thepolitical city

(or the fluxesof

sociopolitical

interaction) should beinterpreted

through

its structures and dynømicsof

urban governance. Recalling the broaddefinition

by

Bagnasco and LeGalés, governanceis'a

processfor

thecoordination

ofactors, ofsocial

groups and institutions in order to achieve collec-tively discussed and defined goalsin

a fragmentedor

even obscure environment'(2000:26).

(3)

The soulof

thepolitical city, or its political

cosmopolitanism,is

affirmedby

thesolidness

of

its social and cultural capitals.It

is its collectivepolitical

intelligence,structuring perceptions, values, attitudes and behaviours of the city as a community. This conceptualizalion

ofurban politics

attributes equal value to landscape, openness and democracy:CITY

COSMOPOLITANISM The cognitive city

OPENNESS DEMOCRACY

NETWORKS The city of

fluxes LANDSCAPE

Figure

l.

The conceptual triangle for interpreting urban politics.Source: Ferrão (2003) and Seixas (2008).

PLACES The c¡ty of stocks URBAN POLmCS RESOURCES Sociocultural capital PLACES Urban governance Government ¡nstitutions

URBAN CHALLENGES IN SPAIN AND PORTUGAL

(1)

The Landscapeof

urbanpolitics

frames thecity of

institutionswith

thecity

of

governance. In this sense, a good

political

landscape requires adequate supportin

terms of resources and

political

instruments, directly or indirectly positionedwithin

the

city's

government dynamics.This

means that there should be core normative elements such as a charterof

principles

and more operational elements such asstrategic, urbanistic and dimensional plans, as

well

as appropriate levels of humanand financial resources.

(2)

Democracytnurbanpolitics

is constructed out of the cultural guidelines and socialprocesses

ofits

civic

and collective values consolidating theinstitutionalpanora-mas

of

urban government. Thepolitical

cosmopolitanismof

thecity

enables andsupports the development of governmental and democratic solutions.

(3)

Opennessin

urban

politics

requiresthe

interrelation

of

governance networkswith

the

city's

structuresof

social

andcultural

capital.A

political

framework, establishedby

the

presenceof

considerable amountsof

openness,proximity

and

connectivity

acrossits

networked spaces, facilitates the inclusionof

a wide rangeof

urban actors, thus fostering a deeper sense and exerciseof

citizenship, consolidating thepublic

space of citypolitics.

Lisbon :

sociopolitical state-of-the-art

Lisbon is

deeply structuredby its

geographywhich

includes a longhistory of

more than2500 years

ofurban

occupation and expansion, a geopolitical semi-peripheral positioning in relation to European history and itsdriving

forces, the large Tagus River Estuary, a vastregional

hinterland

and a city-regionof

around 3million

people and approximately 45o/oof

the Portuguese GDP.Only

around 500,000 inhabitants (i.e. less than20Yoof

the urbanregion) reside

in

its main municipal

core,reflecting

at leastfour

decadesof

continuousterritorial

diffusion

and a process that has passedfrom

suburbanizafionto

urbanization andnow to

trendsof

metropolitanization and hyper-regional socio-economic expansion.These trends include large-scale projects

like

the new airport, new logistic platforms andexpected urban developments

in

locations60

80km

awayfrom

the old historical origin.Like

several European urban regions,it

is

undergoing a rapid move towards an economybased

on

services,culture

andtourism.

Changes aretaking

place despitedifficulties in

the modernization and reconfiguration

of

crucialpolicy

and regulatory dimensions on thedifferent tiers

ofthe

State.A

situation understood by a rangeofdata

such as the fact that Portugal is the OECD countrywith

the second smallestpublic

investment capacity on thepart

ofboth

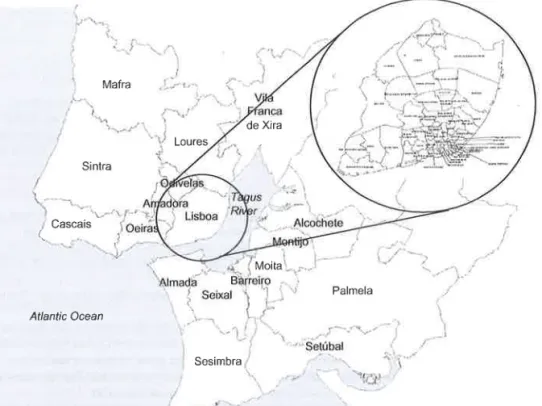

local and regional tiers ofgovernment (Figure 2).3In the institutional core of this urban meta-territory stands the

Municipality

of Lisbon.Representing the autarchic power

of

the capitalcity

of

Portugal,historically

closelymir-roring

the Portuguese (and European) periodsof

expansion and decadence,it

exists as arelevant

institution

since Roman times and has ahistory of

relativepolitical

importance.This considerable stakeholding has however been under pressure since absolutist times and most drastically

during

thedictatorial

regimeof

Salazarin

the twentieth century.a Only afterthe

1974revolution

and the establishmentof

the democraticThird

Republicdid

thelocal

administrationin

Portugal regainits

political

significance, although even todayit

lacks the

full

rangeof

competences typical of most European local and regional structures(Crespo and Cabral 2010).

As

a resultof its

longhistorical

development, Lisbon's sociopolitical and institutionalpanorama

is intrinsically

quite complex. The Lisbon autarchic government structures aremainly based on a large-scale

municipal institution, functionally

structured through someURBAN CHALLENGES IN SPAIN AND PORTUGAL

Mafra Loures Sintra

;)

i I ,:-:'l;. ì ! ,i Cascais(..

..._,-. ... Atlantic Ocean Mo¡ta Palmela Sesimbra '"'Setúbal i: i.. ,J . .1 l',.|Figure

2.

The metropolitan and municipal core territory of Lisbon-

Metropolitan municipalitiesand Lisbon Parish territories.

300 departments and divisions and employing approximately I 1,800 members

of

staff. Itspolitical-executive management

is

carried outby minority

or absolute majorities derivedfrom

atotal

of

l7

councillors. There also stands theLisbon Municipal

Assembly, whichhas general powers

of

legislation, oversight and supervision.Both

political

organshold

considerable

political

autonomy reflectedin

separate electoral ballots.At

more local levelsin

the Lisbonmunicipal

territory, there are 53 Parish Councils (eachwith

their respectiveassemblies and executives)

with

highly

unequalterritorial

distributions and socialstruc-tures. The reduced scope of parish council actions and the daily difficulties faced has gained

widespread recognition by Lisbon citizenship, turning this

political

and administrativebor-ough landscape into one of the main paradigmatic examples of the stalemate reached in the

governance

ofthe

city.Based on the systemic conceptual structure set out above, focusing on the three vertices

of the theoretical triangle

-

cosmopolitanism, places, and networks of urban politics-

and onmultiple

analyses carried out on thecity

and its society over the last decade(including

the debates on the Lisbon Strategic

Chartet'), wc

have developecl a sociopolitical criticalanalysis. Tables

1

3 provide a systematized sumrrrary of the main cc¡nclusions arising fromthese researches and its corresponding developments.6

Cosmopolitønìsm:

sociocultural

cøpitalìn

theLisbon

urbønpolitics

Despite an entrenched strength

within

its urban culture and identity, as well as in most of itsneighbourhood social structures, the sociocultural capital

ofLisbon's

urban society retainsURBAN CIJALLENGES IN SPAIN AND PORTUGAL

and urban benefits; knowledge deficiencies

on

urban andcity

problems,with

a

stateof

'relative ignorance' as to what is at stake

in

the contemporary city, therebypermitting

themaintenance

of

cultural

and administrative structureswith

little

capacityfor

developingtransversal and

multidisciplinary

approaches. There isstill

a consideiable absenceofopen

channels

of

governance,'public

spaces'for

dialogue and cooperation established beyondTable

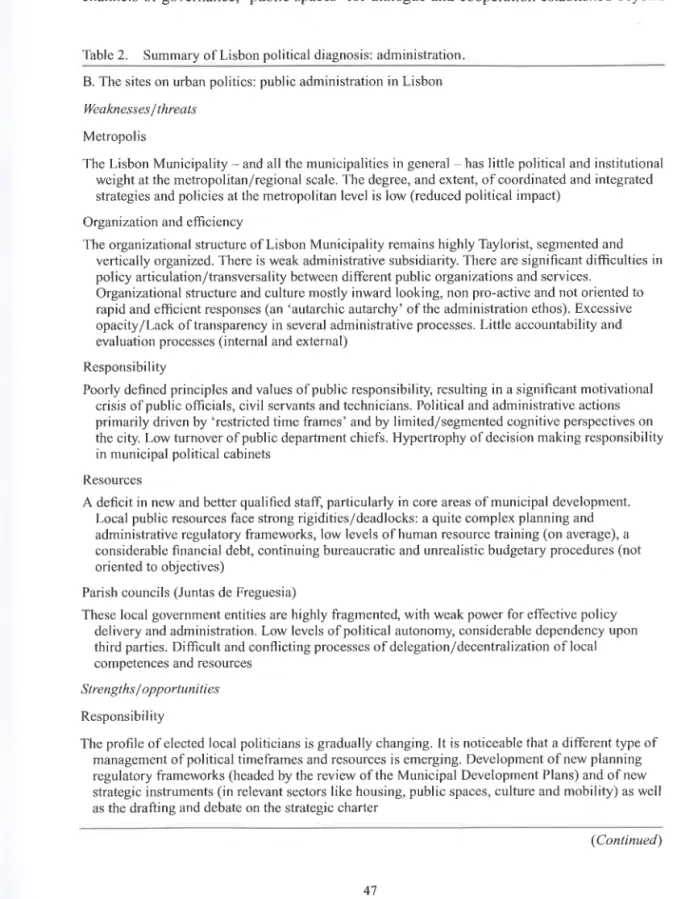

2.

Summary of Lisbon political diagnosis: administrationB. The sites on urban politics: public administration in Lisbon

Weaknesses f threats Metropolis

The Lisbon Municipality

-

and all the municipalities ingeneral

has little political and institutionalweight at the metropolitan/regional scale. The degree, and extent, of coordinated and integrated

strategies and policies at the metropolitan level is low (reduced political impact)

Organization and effi ciency

The organizational structure of Lisbon Municipality remains highly Taylorist, segmented and

vertically organized. There is weak administrative subsidiarity. There are significant difficulties in

policy articulation/transversality between different public organizations and services.

Organizational structure and culture mostly inward looking, non pro-active and not oriented to

rapid and efficient responses (an 'autarchic autarchy' of the administration ethos). Excessive

opacity /Lack of transparency in several administrative processes. Little accountability and

evaluation processes (internal and external)

Responsibility

Poorly defined principles and values ofpublic responsibility, resulting in a significant motivational

crisis of public officials, civil servants and technicians. Political and administrative actions

primarily driven by 'restricted time frames' and by limited/segmented cognitive perspectives on

the city. Low turnover ofpublic department chiefs. Hypertrophy ofdecision making responsibility

in municipal political cabinets

Resources

A deficit in new and better qualified staff, particularly in core areas of municipal development.

Local public resources face strong rigidities/deadlocks: a quite complex planning and

administrative regulatory frameworks, low levels of human resource training (on average), a

considerable financial debt, continuing bureaucratic and unrealistic budgetary procedures (not oriented to objectives)

Parish councils (Juntas de Freguesia)

These local government entities are highly fragmented, with weak power for effective policy

delivery and administration. Low levels ofpolitical autonomy, considerable dependency upon

third parties. Difficult and conflicting processes of delegation/decentralization of local

competences and resources

S trengt hs / oppo r tu nit i es Responsibility

The profile ofelected local politicians is gradually changing. It is noticeable that a different type

of

management of political timeframes and resources is emerging. Development of new planning

regulatory frameworks (headed by the review of the Municipal Development Plans) and of new

strategic instruments (in relevant sectors like housing, public spaces, culture and mobility) as well as the draÍïing and debate on the strategic charter

(Continued)

URBAN CHALLENGES IN SPAIN AND PORTUGAL

Table

1.

Summary of Lisbon political diagnosis: sociocultural capital.A. The cosmopolitanism on urban politics: sociocultural capital in Lisbon

Weaknesses f threats

Elites

Lisbon has no consistent urban-oriented political community. There is still an embarrassed

promotion of the city as a sociopolitical object. Decision making elites continue to display little

interest in the city's problematic and are much more orientated to the National and International arenas. The few locally driven elites are mainly connected to the municipal scales, not to the

entire city region

Strategy

The major challenges facing the city (culturally and politically speaking) still have not been clearly

discussed, placed and addressed. There is therefore an evident lack of strategy (namely a

collectively understood strategy)

Information and knowledge

There are few places and opportunities for developing an awareness ofthe realities and challenges

facing the city Citizenship

Most of the city population still reflects an important difference between passive and active

citizenship. Metropolitan housing and economic fragmentation over the last four decades has

resulted in the fragmentation of critical mass and many relational networks Strengths / opportunities

Citizenship and sociocultural capital

The cultural and symbolic capital of Lisbon retains deep strengths (especially in the dimensions

of

neighbourhood identity and ofoverall cultural and city identify). Currently new political attitudes

and civic engagement dynamics are developing, particularly among the youngest and educated

classes. Over the last 5 years there have been a considerable expansion ofopportunities for debate and discussion of urban related themes (conferences, seminars, media, Internet and blogs) Elites

There is under formation a young and cultured class that understands the city and its urban

Iivelihood as a key-dimension for development and sustainability

Strategy

Some recent strategic processes and instruments have been under construction, such as a new

urbanistic plan (PDM), new sectoral strategies and the Lisbon Strategic Charter initiative

Sources'. Seixas (2008); seminars ofl the Lisbon Strategic Charter, 2009; report 'Quality of Life and City

Government in Lisbon' (lSEc/lCS 2010).

a volatile consistency, especially when projecting community citizenship dynamics. Recent

research has shown how there are

still

important distances between passive citizenship andactive citizenship attitudes (Cabral et

a|.2008).

Our previous research (Seixas 2008)devel-oped along

six

different vectorsof

urban sociocultural capital valorization (see Figure 3)demonstrated structural limitations that still exist today. These include the limited traditions

of Portuguese society's

civic

involvement and participation, with public questions not beingeasìly understood as

a collective responsibility;

a perceptionof

a relative superpositionbetween public involvement and

civic

involvement; the magnitude of sociospatialURBAN CHALLENGES IN SPAIN AND PORTUGAL

Table

2.

(Continued) Or gantzati on and effi ciencYGood levels of pro-activity and efficiency in various municipal administrative entities

-

namelythose in close proximity with: strategic rationales, high autonomy and public visibility,

cooperation and networking active involvement, concrete local territories. Several administrative

areas are renowned for their quality, flexibility and innovation. Some renovation and haining

of

employees. A political process aiming at a global reform of the administrative and government structures ofthe city, with strong support from the municipality presidency, is underdevelopment. Proposals for new organizationprocedures based on the Lisbon Strategic Charter

Resources

Due to its size (almost 12,000 public employees), the municipal human resources must still be seen as a potential stronghold. There is some (albeit little) human resources renovation

Sources'. Seixas (2008); semìnars of the Lisbon Strategic Charter, 2009; report 'Quality of Life and City

Government in Lisbon' (ISEG/ICS 2010).

Table

3.

Summary of Lisbon political diagnosis: networking and participation.C. The governance on urban politics: networking and participation in Lisbon

Weaknesses f threals

Governance

Wide areas of the local administration apparatus operates within a closed circuit, standing apart

ÍÌom the city itself(an internal Zeitgelsl). In some areas, there has been steady progress towards

more cooperative and governance processes with socio-economic city actors. However most

of

these have only extended to a few processes with limited impact (and still lacking plurality).

A

notably lack of more permanent governance/diâlogue instruments and institutions. Considerable

power hypertrophy based on semi-closed political communities. Lisbon society retains a considerable mistrust towards the city's government and administration structures and officials

S trength s / opp or tuniti es Social capital

As confirmed by a range ofresearch, Lisbon society retains a relatively latent civic awareness and

capacity for responsiveness

-

compounded by considerable difficulties in social and politicalmobilization. A very significant and important symbolic and social capital on the scales of the

city's many neighbourhoods. Over the last 5 years there has been a considerable expansion

of

opportunities for debate and discussion ofurban related themes (conferences, seminars, media,

Internet and blogs)

Governance

Overall the local Parishes have very good relationships with the community

-

although theirshortage ofresources strongly curtails these potentialities. There have been some recent development ofparticipative processes, like the Participative Budget process (since 2008,

containing 7o/o of overall municipal investment), the Local Housing Strategy Programme and the

Strategies for City Culture. Proposals for new and wider governance instruments in the Lisbon

Strategic Charter

Sources'. Seixas (2008); seminars of the Lisbon Strategic Charteq 2009; report 'Quality of Life and City

Govemment in Lisbon' (ISEG/ICS 2010).

the usual debates held

during

election periods andpublic

consultation proceduresestab-lished

in

normativeplanning

frameworks. Research alsoconfirms the continuing

weaklevels of interest among Lisbon's urban elites in participative processes or even in concrete

professional and

political

involvement in urban govemment and urban governance systemsURBAN CHALLENGES IN SPAIN AND PORTUGAL

Figure

3.

Dimensions of valorization of the sociocultural capital in an urban society(Seixas 2008). This latter is an important factor that does not facilitate the development

in

Lisbon

urban societyof

'local

political

communities'

(Jouve and Lefévre 1999), beyondpolitical

communities linked to more specific and particular goals.However, notwithstanding

this

panorama

of

undeniable

fragilities,

our

previousresearch also identified interesting aspects in the development

ofa

wider 'urban socialcog-nition'

in

Lisbon-

and the developmentof

çorrespondingpolitical

andcivic

involvementattitudes

-

in

its neighbourhoods and communities, and expressed in NGO, academic andmedia attention. These included more debate, more

civic

intervention and social pressures(even beyond the common

NIMBY

type concerns), more scientific and general debates oncity-related subjects.

Moreove¡

the current rapid expansionofindividualized

expressionsofcitizenship

through the Internet, supposedly quite fractal and kaleidoscopic, iscontribut-ing to an increasing awareness, based on a relative consolidation of cultural çapital of urban

cosmopolitanism, increasingly

influential

within

the sociopolitical

structuresof

Lisbon.Nevertheless,

it

is

still

not atall

clear how these expressionswill

develop strongerstruc-tures of sociocultural çapital, as well as becoming materialized in any form of more modern

and democratic governance development.

Pløces: ìnstìtutìons ín the

Lßbon

urbønpolítìcs

Notwithstanding the vast number of

public

services providedby

thepublic

administrationto

meet thecity's

needs, ourcritical

analysisof

thelocal institutional

and governmentalfields also found important gaps

-

and structuraldifficulties

in

reducing them-

between the city'spolitical

places and the city-system's problematic and challenges.We need to refer to two important areas

of

shortcomings attwo

quite different scales.First, the recognition that the metropolitan scale has yet

to

create an empoweredpolitical

institution;

and second the inner local parish/neighbourhood government configuration istotally

inadequate and deprivedof

resources. Thesetwo

expressionsof

relevantpolitical

URBAN CHALLENGES IN SPAIN AND PORTIJGAI,

Therefore, as

noted

above,local

political

agendas areto a

significant

degree dom-inatedby

theselogics,

overshadowingmore

equitablepolitical

projectsand

local-type attentions and leadingthe

administrative frameworksto

clearly

prefer newpublic

man-agement attitudes

to

the detrimenfof

newpublic

administration

actions (Mozzicafreddoel

a|.2003),

perceptively more complex to develop and surely much more delicate tonego-tiate

in

the presentinstitutional,

partypolitical

and labour union contexts.With

referenceto

oneof

the main questions proposed by the French literaturein

these fields-

who gov-erns thecity

(Joana 2000)-

while we

donot

consider thatthe

urban regimeof

Lisbonhas evolved towards a clearly structured global competitive statist regime (as Brenner

con-ceptualized

for

several urban regimes in theUnited

States and Europein2004),

in the lastdecade the Lisbon sociopolitical system has been framed to a considerable degree by power

hypertrophy and sustained through semi-closed

political

communities.The

Lisbon Strategic

Charter

As

briefly

addressed in the introduction to this article,following

the most recent autarchicelection the presidency

of

the Lisbon municipality

asked a groupof

independent urbanthinkers to develop a proposal

for

a future strategic charter for the city. Theinitial

ideas by thelocal political

leadership were threefold. First,to

provide a frameworkfor

thedevel-opment

of

global strategies and objectives to be followed by the city's policies and public administration. Second,for

the charter to be developed through six different areas(or

sixquestions to be answered, as

it

was then proposed): human demography andvitality;

qual-ity

of life

andsocial inclusion;

energy,mobility

andsustainability;

economy, creativityand employment; culture, education and

identity;

and institutions, administration andgov-ernance.

Third for

the

charterto

cover aperiod dating

from

2010until

at

least 2024;this

datemarking the

50th anniversaryof

the Portuguese democraticrevolution,

therebyendowing the process and

its

correspondentmain

instrumentwith

considerablepolitical

symbolism. The independent group (constituted

by

academic experts) developed a work-ing programme that included severalpublic

debates and workshopsin

different areas andphases of the process, as

well

as instrumentslike

Internet e-hearings. The group deliveredits proposal (Commissariate of the Lisbon Strategic Charter 2009) in a formal presentation

to the

city

and themunicipality

on 3 July 2009. The proposalT is constituted by a generalintroductory text, then addressing the main problematic and correspondent principles and

lines of action proposed for the different six areas.

The

purposeof

this

article

is to

analysethe

state-oÊthe-artof

the overall

Lisbon-governing dimensions, through a dualcritical

reading, considering notonly

the diagnosespreviously

developedand

the

charter

proposalsin

the

governing and

administrationdimensions, but also the strategic charter process itself

-

and its present stalemate.The

following

provides a systematic discussionof

the main proposals includedin

thesixth dimension of the charter, focusing on the

city

institutional, administrative andgover-nance areas. The reason for

this

analytical choice is based on theconviction

supported byseveral years ofresearch both on general urban politics perspectives and developments and

on the specificities of the Lisbon sociopolitical

panorama

that the future developmentfor

this (and probably any other) strategic and changeable process

will

strongly depend on itscapacity to address and closely engage

with

the existing and future local sociopolitical andgovernance stakeholdings.

The

proposalsfor

the reform

of

Lisbon-governing

andsociopolitical

structures arebased

on

aglobal vision

thatrecalls 'the

threemodernities'

of

modernhistory

(Ascher1995), somewhat

paralleling

the specificevolution

of

the Portuguesepolitical

evolution,from

the republican

idealisms pursued sincethe

nineteenth century,to

the

democraticURBAN CHALLENGES IN SPAIN AND PORTUGAL

based on classical administrative divisions

but

alsoto

a closed-circuitstate

or, as wehave called

it,

a stateof

considerable zeitgeist-

that seems to be prevalentin

the culturalstructures and ethos

of

severalpublic

andpolitical

organizations.On

the one hand, thepower hypertrophy existing around executive

political

ofûces proved to be simultaneouslya

cause and consequenceof

the lack

of

proactiveness acrossmost local

administrativelevels.

On

the other hand,the

levelsof

administrative efficiency,delivery

andaccount-ability

reveal important weaknesses. Thus, entrenching a panoramaof high political

andadministrative

complexity

with

dispersed andpoorly

rationalized capacitiesfor

action-condensing a state

of

a-topia

in

thecity

administration,withdrawing motivational

cap-ital,

the

capacityto

conceive and discuss strategic objectives,a lack

of

focus on

longterm

and structural reforms, anddaily difficulties working \¡/ith

thecity

andits

citizens.However,

this

autarchic autarchy hasnot

prevented

it

has evenled to

-

the

develop-ment

of

highly liberal

and image-basedpolicies,

strongly basedon

financial,real

estateand

marketing fields. The result

has beena

move

towardsa

discretionary politically

supported urban regime broadly

similar

to the ones conceptualizedby critical

urbanpol-icy

researchers suçh as Jessop(2000,2002)

and Brenner(2004). Overall

this

situationhas,

to

a

large extent andfor too

long,

left

a relevantpart

of

the main

urbanpolitical

agendas

in

Lisbon

dependenton

determinate actors andto

specific partisan and privatestrategies.

We

have, however,also noticed

political

and administrative proactivity

in

severalareas

-

which has steadily evolved over the last few years. Vy'ith the existenceofa

wide andotherwise consolidated normative and

political

institutional structure of government, evenif

with

important gaps and situationsof

malfunctioning, thepolitical

panoramaof

Lisbon also revealed several areasof

administrative modernity,of

strategicthinking

anddemo-cratic improvement. There is evidence of some perspectives for change developing. To this

must be added other types ofpressures and incentives

deriving from

other origins-

fromthe exigencies

ofthe

city-system and urban society itself; but also from other levelsofgov-ernment

like

central government or the EuropeanUnion,

namely, through administrative decentalization enforcements, the empowerment of local autonomies and communities, or through new legal and fiscal frameworks(like

the new nationallaw for

local finance andlocal resources, or an empowered structure of National

city politics in

Portugal), all which imply the need for new demands, new attitudes and new positioning by urban governments.Networks: governance

in Lisbon

urbønpolílics

Previous research also

pointed

to

important

weaknessesin

the

governance dimension.Beyond institutional structures founded on the classical logics

ofpolitical

representation,Lisbon does not contain many governance processes

involving

open andplural

participa-tory processes. The organic links present in the dialogue and partnershipswithin

the urbanpanorama, although natural and obviously healthy

in any

city,

are, however, the almostabsolute

mirror

image of the organic links in the governance panorama not based on clearand recognizable forms of strategic planning,

of

rationahzed public action or of attitudesof

authentic public openness.

This

situation has createdhigh

levelsofuncertainty

andinsta-bility in

urban governance processes and shapes apanoÍama thatis

naturally dominatedby

the dynamics and strategiesof

the dominant stakeholderswho

focuson

urban com-petitiveness andsymbolic

urban cultures and images.In

fact, cultural

pressures and theexpenditure

of

energies by Lisbon's governing system actors-

including the citizenry-

in

their

attention to the most mediatic, symbolic and competitive urban projects were quiteURBAN CHALLENGES IN SPAIN AND PORTUGAL

Republic 1.0 The fulfilment of the republic

structuring networks and human rights in the city

The prov¡s¡on of bas¡c infra-structures ¡n the city

The prov¡sion of housing and basic habitat conditions Republic 2.0

The fulfilment of democracy

The provision of equipments and assistance public services

cohesion and development in the city

quality of life for all

New challengès/transversal needs: environment, age¡ng, soc¡al cohesion, social and functional diversity at different scales,

employment and economic devèlopment governmenvthe city of cities

lìepublic 3.0 The expansion of democracy

cosmopolitanism and proxim¡ty in the city Transparency and prox¡mity in city politics governance, participation and civic involvement The knowledge society and the cosmopolltanism of L¡sboa

effìciency and good use of public resources

Figure

4.

Global vision for the Lisbon political and administrative strategies. Source'. Report 'Quality of Life and City Government in Lisbon' (ISEG/ICS 2010).objectives followed since

the

1974 revolution, and thestill

quite explorative perspectivesfor democratic expansion in this new century (see Figure 4).

As expressed in the corresponding text

ofthe

charter proposal:The proposed change to the Lisbon governance paradigms

-

or

its political revitalization-

is based upon the most critical elementof

the social and politicalcity:

its citizenship.Strengthening citizenship is the best means of sustaining the entire upgrade of a city's

gov-ernance structures.

It

is by strengthening citizenship that community is best built. Lisbon,with its excellent potential to achieve this, needs to build community both at the city scale

(and even at its metropolitan area) as well as at each neighbourhood scale. Correspondingly,

the key concept for the reform of the governance systems

of

Lisbon is the perspectiveof

developing individual and collective citizenship dynamics, and its motto should be: 'Building

Communities

-

City Policies as a New Public Space'.For these

global

objectives, the chartertext

structures three base vectorsfor

reform

andinnovation (Figure 5):

(1)

First, a greaterproximity

betweenpolitics

and the citizen:the revitalization of Lisbon's democratic and governance systems involves the creation

of structures and processes that might enable a greater proximity between politics and

each citizen and a greater sense of sharing the collective destinies ofthe cify and of each

of its neighbourhoods. As the quotidian place for each citizen, as the favoured

space-time for daily experiences and labours, as the scale with the greatest synergy potential

(social, economic, cultural, creative and clearly also political), the city should become

the key facet

in

setting out new ways of building community and hence enabling thedevelopment of social networks, pacts and more collective principles and values. Many

cities are constructing this path, with diverse methodologies and processes already well

under appliance.8 In summary, the city should be the key element

in

deepeningciti-zenship within the scope

ofa

new political culture that has undergone development inconjunction with the emergence of the information and hypertext society into which we

are increasingly submerged.

T]RBAN CHALLENGES IN SPATN AND PORTUGAL

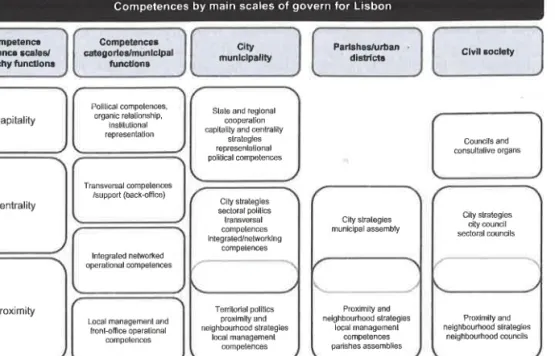

Competêncr elâ¡onca ¡talel rutarahy funciloß Capitality Compel€næ3 etêgorlos/munlcþal funcl¡ons Clty munlclpallty Fañsbes/urõrn distrlcts Clvn 6oclêty Politiæl @mpelenæs, organic relationship, ¡nslilut¡onal representation Trânsveßal @mpelences /support (back-office)

Local managemenl and fronl-offi æ operalional compelences C¡ty slrategies c¡ty @uncil sectorâl councils Prox¡nity ând ne¡ghbourhood sl¡ategies ne¡ghbourhood @uncils

Figure

5.

Structure ofcompetences by main scales ofLisbon politics.Source: Report 'Quality of Life and City Government in Lisbon' (ISEG/ICS 201 0).

(2)

Second a strengthening of administrativepublic

capacities:the political revitalization of Lisbon should equally extend to a clear strengthening

of

the city's public managerial and administrative capacities, given the new needs and

challenges facing urban settlements of the 21st century and the manifest crisis (both

in visionary and in operational terms) currently confronting the current administrative

structures. Similarly, there is the need to extend wide ranging and integrative

strate-gies and a better perception of the spaces and times truly essential to the development

and cohesion ofthe city, endowing responsibilities and resources to the most

appropri-ate scales and entities for public action. There must also be higher requirements able

to drive to greater efficiency and structured evaluation, motivating resources, clarifuing

competences and providing good information and knowledge to the most varied spaces

ofdebate and decision making.

(3) Third

aç7ear statement of the specificitiesof

Lisbonitself:

the

political

revitalizationof

Lisbon should furthermore incorporate the definitiveassumption

of

its

specific character within the metropolitan, national and planetarypanorama. Its dual status of geo-metropolitan centre of the leading national region and

as political capital of a European country with deep historical roots and heavily

influ-enced by political government, places the city in a uniqut: position. This specificity has

to be central in the deliberations of its strategic foundations as well as on its needed and demanded frameworks of competences and resources.

The

charter proposalfollows

with

the listing

of

sevenmajor

principlesþr

an

efficient,participative

and sustoinable system of governancefor

Lisbon.

Fourof

these principles are transversalin

nature, interconnectedwith the four major

systematized guidelines included in the charter's overall text: a strategy-oriented and cumulativeness ofurban public policiesþrinciple

1); the refocusingof

sociopolitical action towards new urban scales andCompetences by main scales of govern for Lisbon

Slate and regionâl @operâtion capilality and æntral¡ty

slrategies represenlational

politi€l competenæs

Councils and consultal¡ve organs

Centrality City strategies

sectorâl pol¡lics lransveßal compelences integrated/networking compelences Territorial politlcs proximlly and neighbourhood strâteg¡es loml manâgemenl competences Cìty strategies mun¡cipal assembly Proximity ând ne¡ghboúrhood stralegies local manâgement æmpelences pañshes assembl¡es Proximity lntegÞled operâtionâl networked æmpetenæs