ContentslistsavailableatSciVerseScienceDirect

Comptes

Rendus

Palevol

www . sc i e n c e d i r e c t . c o m

Human

palaeontology

and

prehistory

Insights

into

the

earliest

agriculture

of

Central

Portugal:

Sickle

implements

from

the

Early

Neolithic

site

of

Cortic¸

óis

(Santarém)

Regards

sur

les

débuts

de

l’agriculture

dans

le

Centre

du

Portugal

:

des

éléments

de

faucille

du

site

Néolithique

ancien

de

Cortic¸

óis

(Santarém)

António

Faustino

Carvalho

a,∗,

Juan

F.

Gibaja

b,

João

Luís

Cardoso

caUniversidadedoAlgarve,FCHS,CampusdeGambelas,8000-117Faro,Portugal bConsejoSuperiordeInvestigacionesCientíficas(CSIC-IMF),08001Barcelona,Spain

cUniversidadeAbertaandCentrodeEstudosArqueológicosdoConcelhodeOeiras,2784-501Oeiras,Portugal

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:Received6August2012

Acceptedafterrevision28September2012 Availableonline8January2013

PresentedbyYvesCoppens Keywords: Sickletypologies Use-wear Agriculture EarlyNeolithic Portugal

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

DirectevidenceofagricultureinEarlyNeolithicPortugalisalmostnon-existent,sothereare verydisparateestimatesoftheroleplayedbyagricultureduringtheperiod.Recent exca-vationsatCortic¸óis,anewlydiscoveredEarlyNeolithicsiteincentralPortugal,revealed thefirstrecognizablesickleimplementsandthereforerelevantartefactualevidenceof agriculturalpractices.ThesearetypologicallysimilartoAndalusianandValencian sick-les,reflectingacommontechnologicaltraditioninsouthernIberiaduringtheperiod(c. 5600–4000calBC).Basedonthisfact,wesummarizeallavailableevidenceforearly agri-cultureincentralPortugalandcompareitwiththeAndalusianandValencianrecordsin ordertotentativelypresentamodeltobetestedlocallyinfutureresearch.

©2012Académiedessciences.PublishedbyElsevierMassonSAS.Allrightsreserved.

Motsclés: Typologiesdefaucilles Tracéologie Agriculture Néolithiqueancien Portugal

r

é

s

u

m

é

Lestémoinsdel’agriculturedurantleNéolithiqueancienauPortugalsontpresque inex-istants,cequientraînedesestimationstrèsdisparatessurlerôlejouéparl’agricultureau coursdecettepériode.DesfouillesrécentessurlesitedeCortic¸óis,unsiteduNéolithique ancien,récemmentdécouvertdanslecentreduPortugal,ontpermislamiseaujourdes pre-miersélémentsdefaucillesetdoncd’unepreuveartefactuellepertinentesurlespratiques agricoles.Ellessonttypologiquementsimilairesauxfaucillesandalousesetvalenciennes, cequireflèteunetraditiontechnologiquecommunedansleSuddelapéninsuleIbérique aucoursduNéolithiqueancien(c.5600–4000calBC).Partantdecefait,nousrésumons touteslesdonnéesdisponiblesconcernantledébutdel’agricultureaucentreduPortugal etnouslescomparonsaveclesregistresandalousetvalencien,l’objectifétantdeprésenter unmodèleprovisoire,àtesterlocalementdansdefuturesrecherches.

©2012Académiedessciences.PubliéparElsevierMassonSAS.Tousdroitsréservés.

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:afcarva@ualg.pt(A.F.Carvalho).

1631-0683/$–seefrontmatter©2012Académiedessciences.PublishedbyElsevierMassonSAS.Allrightsreserved. doi:10.1016/j.crpv.2012.09.004

32 A.F.Carvalhoetal./C.R.Palevol12(2013)31–43 1. Introduction

Despite earlier attempts, a definition of the Early Neolithic of Portugal was clearly established only in 1970 by Guilaine and Ferreira, who defined it accord-ing to a two-stage development–Cardial and “l’horizon desgrottesàpoteriesinciséesetimprimées”–paralleledto thetypological-culturalframeworkavailableatthetime forNeolithiccavesequencesfromthewestern Mediter-ranean.ThePortuguesesiteswouldbethewesternmost manifestationsofthe“Cardialculture”,aswellasitslater, Epicardialderivative.Althoughstillacceptedtodayinits generalstructure,thismodelwasbasedsolelyon typolog-icalcomparisonsofpotteryassemblagesrecoveredfrom sites–mostlycavesexcavatedinthe19thandearly20th centuries–withnorecordedstratigraphiccontexts.

Since the 1980’s, the number of sites with detailed stratigraphyandcontextualrecordshasincreased dramati-cally,namelyintheEstremaduraregionofcentralPortugal, the westernmost tip of the Neolithic expansion across the Mediterranean. These sites provided the first solid piecesofevidenceconcerningmaterialcultures,settlement systems,funerarypractices,absolutechronologies–which currentlyestablishesthe5400–4000calBCtimeinterval for the Early Neolithic–and subsistence strategies. Evi-dencerelatedtothelatterisscarce,however,andinmost casesindirect.Althoughthepresenceofdomestic mam-malshasbeendocumentedsincethe1990s,directevidence ofagricultureisstillcompletelylacking.Sedimentsarenot usuallysubjectedtoflotationandsomeofthesitesmay havebeenspecialized forotheractivitieswhere agricul-tureisnotexpectedtooccur(e.g.,huntingcamps,shepherd shelters,necropolises).AgriculturalpracticesintheEarly NeolithicofcentralPortugalarethereforeonlytentatively characterized.

Theoverall food-production economy has thus been subjectedto disparateinterpretations, and a priori the-oretical assumptions clearly dominate over empirically supportedarguments. Portuguesearchaeologiststendto followoneoftwomainperspectivesonthe characteriza-tionofagriculturalpractices:

• somedefendthethesisthatiftheNeolithicwayoflife emergedafterapioneercolonizationprocessoriginated inthewesternMediterranean basin (aswould bethe caseincentralPortugal),itmusthaveimpliedthe intro-ductionofafullrangeofdomesticspecies,bothanimals andplants,aspartofthe“Neolithicpackage”.Therefore, agriculturemusthavebeensimilarinthecropsand prac-ticesalreadydocumentedinthoseregions(forarecent overviewseeZapata et al., 2004;Zeder,2008); or,as Zilhão(1997)putsit,“absenceofevidence” cannotbe considered“evidenceofabsence”;

• however, most archaeologists stress the current lack of field evidence and consider agriculture to be of negligible importance or “limited” to a horticultural epiphenomenonduringtheEarlyNeolithic.Theprocess musthavebeenbasedonapiecemealadoptionof domes-ticplantsandanimalsbylocalMesolithiccommunities. Accordingtothispointofview,onlyinlaterperiods,with thearrivalofthe“secondaryproductsrevolution”(which

isstillthoughttooccuronlyatthebeginningofthe3rd millenniumBC),didagriculturalpracticesbecomefully establishedandconstitutedarelevantsubsistence strat-egy(e.g.Jorge,2000).

InthecontextofaresearchprojectontheIronAgeon theTagusleftbanks,fieldsurveyingledtothediscovery in2010ofanEarlyNeolithicsitenearthemoderntown of Almeirim–Cortic¸óis (Fig.1), which wassubsequently excavated(Cardosoetal.,2012).Amongotherartefacts,it revealedanassemblageofflintimplementswhich,after theiruse-wearanalysis,weredeterminedtobetoolsused intheharvestingofcereals.ThisparticularfindatCortic¸óis impliesobviousrelevantrepercussionsonthedebateabout theearliestagricultureintheregion.Thus,themainsubject ofthispaperistwofold:

• to present the use-wear analysis carried out on the Cortic¸óis flint tools that allowed their classification as sickle implements(analytical procedures, obtained resultsandinterpretation),comparingthemtotheEarly NeolithicsickletypologiesoftheIberianPeninsula; • todiscussthisfindinthecontextofavailableevidence

for agriculture in southern Iberia (crops, their evolu-tion throughtime and regional variations), buildinga model for the presumed agricultural practices in the EarlyNeolithicofcentralPortugaltobetestedinfuture research.

2. Materialandmethods 2.1. ThesiteofCortic¸óis

Cortic¸óisislocatedonavastsandyfluvialterracegently inclinedtowardstheTagusRiver,only2kmeastfromits modernleftbank(Fig.1).Lithicandceramicartefacts typo-logicallydatabletotheEarlyNeolithicwerescatteredall overthearea,butsomedenserconcentrations–probably theremnants of differentepisodesof occupation– were alsovisible.Thelargestofthesewasfoundonaplatform overlookingthesurroundinglowersectionsoftheterrace andwasthereforeselectedforexcavation,whichtookplace inSeptember2010.

Thesiteiscurrentlydividedintoparcelsforthe build-ingofresidences,alimitingfactorthatcircumscribedthe excavationtoanunoccupiedparcelintheplatform. Test-ingofotherparcelstoevaluatepossiblespatialvariations withinthesitewasnotpossible.A64m2areawas

exca-vated,correspondingtoan8×8msquarewhichreached anaveragedepthof0.90m.Assuspectedduringthe sur-face survey, thedeposit was disturbedto a depthof c. 0.80mbelowthemodernsurfaceby deeptrenching for vineyardplantation,butpotteryrefittingexercisesallowed themeasurementofthedistance.Asillustratedbyvessels 5(composedbytwopotsherds) and6(threepotsherds) fromFig.2,fragmentswerescatteredthroughcontiguous units butreaching0.30–0.45mdepth. Thesame istrue forthefourpolishedstonetoolswhichwereallfoundin squareA2.Thesefactstestifythepredominanceof verti-cal,ratherthanhorizontal,displacements.Thisobservation reducesthepossibilityofmixingofcontiguousoccupations and pointsto a chronologically homogeneous Neolithic

Fig.1.Left:locationoftheregionunderstudy(rectangle)andtheNeolithicsiteofCortic¸óis(star);right:sitelocationandneighbouringarea;bottom:a viewofthesandyterracesandvineyardsimmediatelyaheadoftheCortic¸óisplatformwheretheexcavationtookplace.

Fig.1. Gauche:localisationdelarégionétudiée(rectangle)etdugisementnéolithiquedeCortic¸óis(étoile);droite:localisationdugisementetdelazone environnante;enbas:vuesurlesterrassesetlesvignoblesimmédiatementenamontdelaplate-formeoùonteulieulesfouillesdeCortic¸óis.

occupationinthissectoroftheCortic¸óissite,asalso tes-tifiedbyitsmaterialculture.

Giventhesedimentacidity,Neolithicorganicmaterial wasnotpreserved;thusradiocarbondeterminationscould notbeusedforachronologicalattributionoftheNeolithic

occupationofthesite.Chronologicandculturalattributions couldonlybeobtainedbycomparisonsofmaterialculture items.

Potterywasthekeydatingmaterial.Refittingallowed thereconstructionof179vessels,11(6%)ofwhichwere

34 A.F.Carvalhoetal./C.R.Palevol12(2013)31–43

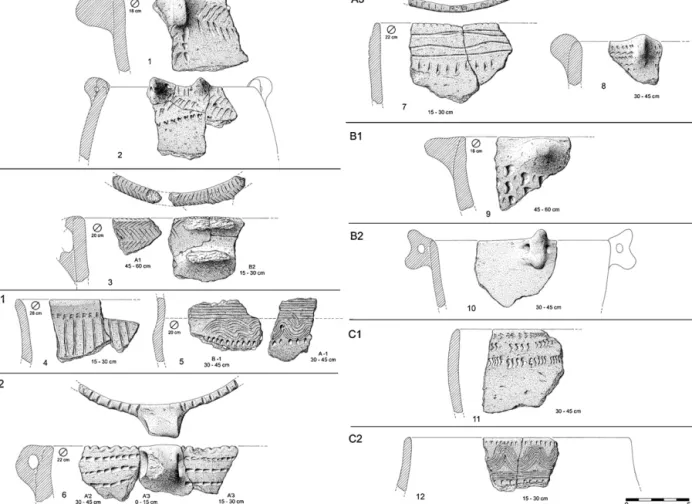

Fig.2.DecoratedpotteryfromCortic¸óis(drawingsF.Martins).

Fig.2. PoteriedécoréedeCortic¸óis(dessinsF.Martins).

decoratedwith spinemotifsobtainedby sharp incision (Fig.2: 3),wavyorstraightincised linesproduced bya comb(Fig.2:5,12),resultinginsomecasesinbaroquely decoratedpots,andpunctures,atechniquethatcombines incisionandimpression.Thisis presentunder theform ofboquique(Fig.2:6)–uninterruptedpuncturesforming irregularchannels–andthemotifknownas“falseacacia leaf”(Fig.2:1,2,8).Amongtheimpressedpotsherds,there issomecardial,asillustratedinFig.2:11.These decora-tions,aswellasthethickperforatedhandlesresembling pig’sheadspresentinsomepots(Fig.2:10),aretypicalof theevolvedEarlyNeolithicintheregion.Wavylinesmay specificallycharacterizetheendoftheperiod,probablythe lastquarterofthe5thmillenniumBC.Thepresenceof car-dialpotsherdsisnotsurprisingintheselater,epicardial contexts.

Polished stone tools are represented by four adzes, mainly made with locally available raw materials. The chipped stone inventory totals 1707 artefacts obtained from the knapping of flint–which amounts to 96% (n=1630) of the total lithic artefacts, quartzite, quartz and rock crystal. Unlike thepolished tools–, flintmust havebeencollectedinthelimestonemassifsoftheTagus rightbanks.Coretypologyisdominatedbybipolar(direct

percussionwithhammerandanvilstones)andprismatic methods (18and9 pieces,respectively).Side-retouched flakes(n=32),bladelets(n=21)andnotchedflakes(n=11) arethemostcommontooltype(30%,20%and10%, respec-tively).Ofinterestisthepercentageof truncatedblades or bladelets (n=5;7%), someof which are oblique and with“cerealgloss”in theunretouched edgenexttothe truncation.Truncatedbladesandbladeletsareinfactvery scarcelyrepresentedintheevolvedEarlyNeolithic assem-blages of central Portugal, ranging from 3.5% to 7% of thetotalformaltoolswheneverpresent(Carvalho,2008). Armatures,composedmainlyofsegments,makeup10% (n=11)of thetotal retouchedtools, whichis in perfect accordancewiththeirnormal8–12%variation.

2.2. Use-wearanalysisofsickleimplements

Use-wear analysisoflithic artefacts wasinitiated by theRussianresearcherS.A.Semenovinthe1930s, even-tuallyspreadingandconsolidatingasanautonomousline of research in the USA and Europe in the last quarter of the 20th century. Experimental frames of reference, ethnographic analogues and archaeological data, along-sidetherecentadvancesinmicroscopy(high resolution

microscopesandSEM)anddigitalphotography(high reso-lutionphotosandspecificsoftware,suchasHeliconfocus), allowustoapproachtheworkedmaterialandthe kinemat-icsinvolvedinitstransformationorprocessing.

During the 1980s, a broad debate took place on NearEasternearlyagricultureconcerningthedistinction betweenmarksonsickleimplementsresultingfromthe harvestingofwildversusdomesticcereals.Explicitly,the debate’sobjectivewastodetermine,throughuse-wearof lithictools,whendomesticcerealswerefirstcultivated:if duringthetransitionfromtheNatufiantothePre-Pottery Neolithic or if solely during the latter period. The out-comeofthisdebatewasthat,accordingtoUnger-Hamilton (1983, 1985,1988),domestic cerealswould causemore striationsonlithicimplementsduetoprevioussoil plough-ing,a conclusionnotfullyacceptedby Anderson(1983, 1988,1992)andAndersonetal.(1991).

Independently of theconclusionsreached, theabove exampleshowsthatsickleimplementsareinany circum-stancecrucialpiecesofevidenceinthestudyoffarming communitiessincetheycanbedirectlyconnectedtothe harvestingof cereals and thereforeprovide evidence of agriculturaltechniquesandpractices.Thisisparticularly important in archaeological sites with no carpological preservation,suchasthecaseofCortic¸óis,wherea sam-pleofnineflinttoolsrevealedthefirstwell-documented NeolithicsicklesinwesternIberia.

Themethodologyemployedintheiranalysishasbeen widely described before (Gassin, 1996; González and Ibá ˜nez,1994;Jensen,1994;Keeley,1980;Vaughan,1985; etc.)andhasrecentlyundergonefurtherrecent develop-ments(Gibaja,2008;Ibá ˜nezetal.,2008).Abinocularlens NikonSMZ-10A(allowing10×to90×magnifications)and metallographiclensOlympusBH2(50×to400× magni-fications)wereusedin conjunctionduringtheanalyses. Giventheabsenceofconcretions,thelithictoolswereonly washedwithcleanwaterandsoap,makingtheuseofacid solutionsunnecessary.

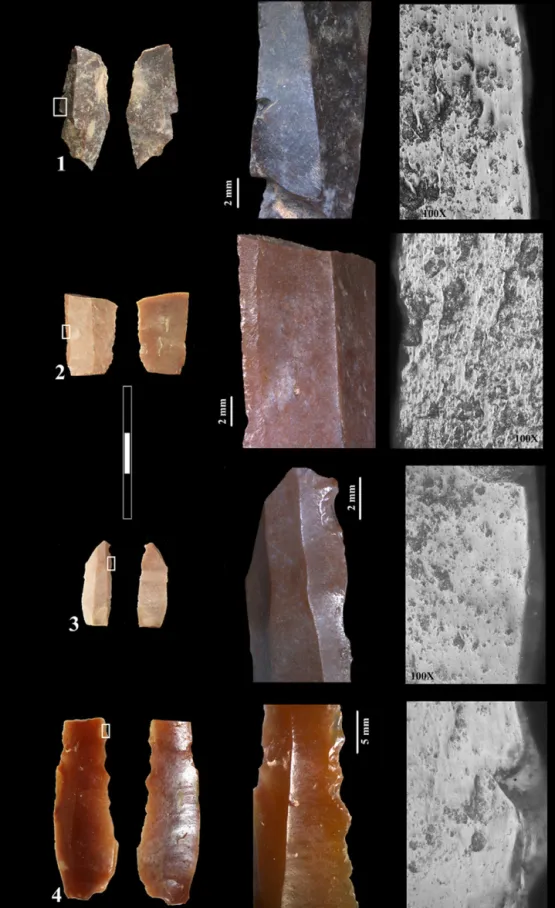

Ourexperimentsontheharvestingofdifferentplants (see referencesabove), both wild(reed,fern, cane) and domestic(wheat,barley),showthatundifferentiated use-wearisformediflithicimplementsaresubmittedtoashort periodofuse(usually30–60min,dependingonvariables suchasplanthumidity,amountofplantsilica,typeofflint, etc.).Atthisstage,micro-polishisnotwelldevelopedand thedistinctionbetweencerealsandwildplantsisrather difficult.However,whenahigherdegreeofwearisreached aftermoreintensiveuseoftheimplement,theharvesting ofcerealscreatesacompletelyoriginalseriesofuse-wear, clearlydistinguishablefromtheharvestingofother non-ligneous plants (see alsoYamada, 2000).In this case,a very extensive,bulkyand homogeneousmicro-polish is obtained,sometimesreachingthelongitudinalnervuresof theflintblade.Thismicro-polishisnotverylustrous,but presentsa verydensetexturethatextends totheinner partsoftheimplement’stopography;withinthis micro-polishnumerousmicro-cavitiesandstriations(mainlyif theharvestingtakes placeatthestalk’slower sections) of different shapesand sizes are evident,and so-called “comet-like”striationsalsobecomeverycommon.The for-mationanddevelopmentofuse-wearinlithicartefactsare

alsodependentonthespecificcharacteristicsoftheraw materialanditsresiliencetohumanandnaturalfactors. Thus,decipheringthesuccessiveimpactsonlithicsurfaces andwearmarkswillpermitamorecomprehensive anal-ysis.vanGijn(1989:40)synthesisesthis approachwith thefollowingwords:“Itissuggested,however,thatitis possible,atleastexperimentally,todifferentiatebetween polishesfromcuttingreedsandthosefromreaping domes-ticatedcereals,inthesensethattheformerhavea‘wet’, fluid-likeappearance(eveninthecaseofawell-developed polish),whilethelatterhaveasomewhatrougherand flat-terpolish”.

IntheCortic¸óiscase,thesampledtoolsdisplaystrong polishing,probablyresulting fromthepost-depositional abrasive effect of the sandy sediments. This fact pre-ventedaneasyrecognitionofmicro-polishgeneratedby theprocessingofsoftermaterialssuchasmeat,fishorfresh skin.However,theobserved micro-polishis well devel-opedandextendsalongmostofthetools’edges,permitting itsdiagnosisasmarksproducedduringtheharvestingof cerealsorothernon-ligneousplants.In spiteofthefact thathaftingmayleaveminorandisolatedmarksonflint implements(Roots,2003),theCortic¸óissickleflintsclearly show,notonlycerealmicro-polishdistributedalongthe tool’sedges,but alsosomeblank modificationallowing therecognitionofthewaytheywerehafted.Thehafting modeisrecognizablethroughthemicro-polish distribu-tionalongtheedgeoftheimplement.Whencerealpolish iswelldeveloped,suchasinthecaseofCortic¸óis,thelimit ofthehaftisevenrecognizabletothenakedeye.

Insum,comparingthementioneduse-wear characteris-ticsoftheCortic¸óisflintimplementswithourexperiments wecansecurelyconcludethesewerehaftedinsicklesused, at least, for cereal harvesting (Fig.3).By “at least” we meanwecannotconfirmthepossibilityof thesesickles beingusedsolelyincerealharvesting.Accordingtomodern analogues,farmersoccasionallyusetheirmetalsicklesin othertasks,suchastheremovalofweedsfromcultivated plots;theproblemisthedetectionofsuchactivities.Inthe Cortic¸óiscase,cerealharvestingactivitiesweredetected butthoselesssystematicactivities,althoughprobable,did notleavenoticeableuse-wearonthelithicimplements.

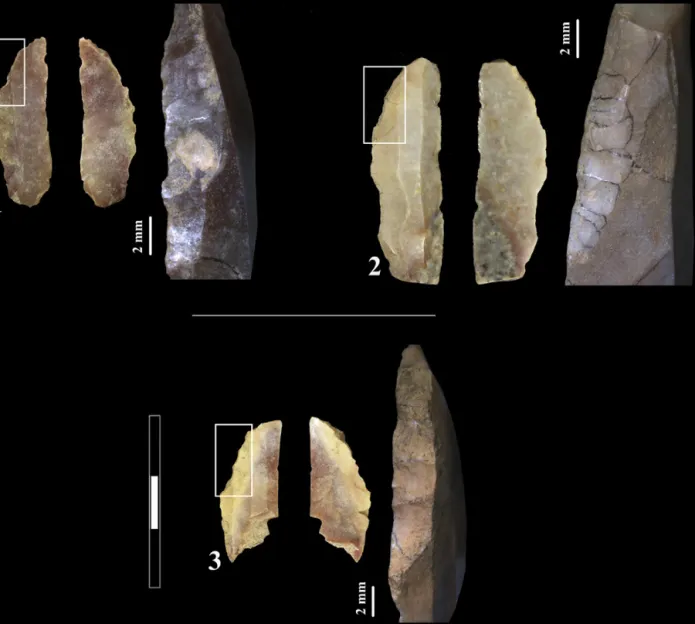

ThenineflinttoolsfromCortic¸óisrecognizedassickle implements also share a few common morphological attributes:theyrangeinsize from3.0–4.0cm inlength, 1.0–1.3cminwidthand0.2–0.3cminthicknessandwere allmadeonbladeorbladeletblankssegmentedbyabrupt retouchatoneorbothendsinordertofacilitateits paral-lelinsertioninthehaft,originatingformaltoolsclassified asstraightorobliquetruncations.Thisprocedurepermits theeasyreplacementofanyimplementlostorbroken dur-ingtheharvest,oronewhichhaslostitseffectiveness.On theotherhand,theserelativelystandardizedsizes (spe-ciallywidths)and retouchoptionsareclearlyrelated to theimplement’shaftingmode.Averagewidthsalso indi-catetheseblankswereobtainedfromprismaticratherthan frombipolarcores.

Accordingtoexperiments(e.g.Anderson,1992;Gibaja, 2003;Unger-Hamilton,1991),thenumberofstriationsis directlyrelated tothedistancefromthesoilwhere the cerealstalkiscut:ifthecutisclosertothesoilthenumber

36 A.F.Carvalhoetal./C.R.Palevol12(2013)31–43

Fig.3.Evidenceofcerealpolishonblades.

ofstriationsisconsiderablehigherduetotheearth par-ticlesadheringtothelowerpartofstalks.Otherauthors haveshownthatthenumberofstriationsismorea fac-torofthedegreeofdevelopmentofpolishratherthanthe heightofcut(Ibá ˜nezetal.,2009).AtCortic¸óis,thenumber ofstriationswithinthepolishisverylow;thismeansthat theharvestingtookplaceinthemiddleoruppersections ofcereal stalks.Asa consequence,partofthestalkwas leftinthefield–probablytobeusedasfertilizeror fod-der–whiletherestwastakentothecampsitetobeused asconstructionmaterial,clothing,fodder,etc.

3. Discussion

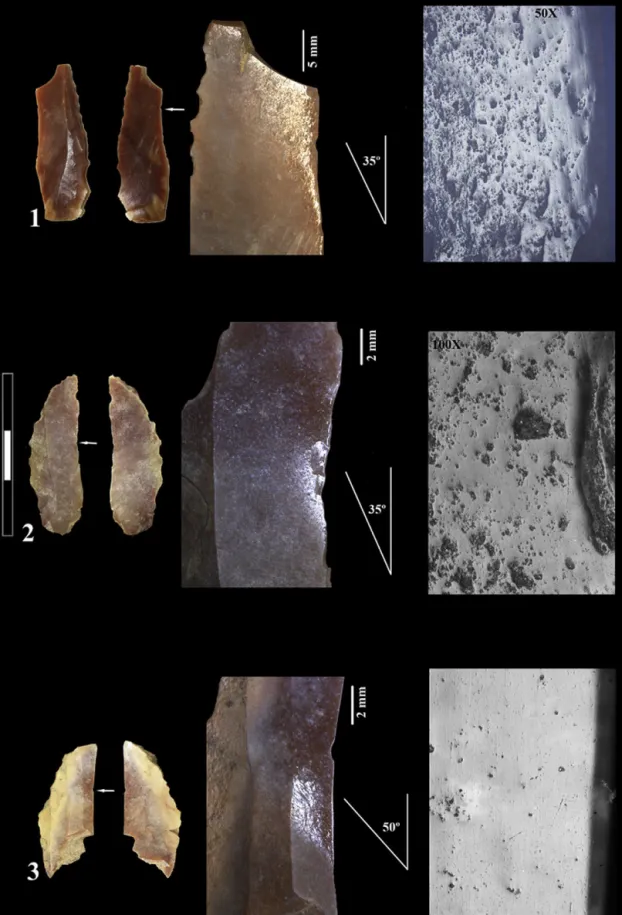

3.1. TheCortic¸óissicklesintheirIberiancontext

ThreesmallflakesandbrokenbladeletsfromtheEarly NeolithicsiteofValadadoMato(datedtoc.4900calBC), intheAlentejoregionofSouthPortugal,werethefirstflint toolstobetentativelyclassifiedassickleimplementsin thecountryaftertheiruse-wearanalysis.However,these artefacts were poorly preservedand their hafting tech-niquecouldnotbeclearly recognized(seeGibaja etal., 2002:220–221,foradetaileddescription).Asmentioned intheprevioussection,thedistributionofpolishonthe flintimplementsallowedustoinferthehaftingtechnique inthecaseofCortic¸óis.Herethepolishisslightly diago-naltothetool’sedge(35◦–50◦)andtheoppositeedgewas insertedinthegrooveofthehaftwithmastic.Thisexplains theabsenceofpolish(asillustratedinFig.4)andthe pres-enceofabruptretouch. Retouchwasmeanttofacilitate hafting,topreventdamagingtheinnerpartofthegroove withsharpedges,andtoadapttheblade’smorphologyto thelinearaxisalongwhichallthesickleimplementswere inserted(Fig.5).Intheseretouchedareas,thereis occasion-allysomelightpolishwithstriationsparallelorobliqueto thebackededge.Thesemayhavebeengenerated when insertingtheflintinthegrooveand/orasaresultofthe sickle’suseinharvesting(Fig.6).

These types of implements and their hafting tech-niques–thus, the sickle typology–are similar to those documentedatotherEarlyNeolithicsitesintheValencia andAndalusiaregions,respectivelydatedfromthe mid-dleand last quarterofthe 6thmillennium BConwards (Gibajaetal.,2010).However,differenttypesofsicklesare recordedinthenorthernregionsofIberiaandSoutheast France.Elongatedflakesorlargeblades(3–8cm length), withcerealpolishparalleltotheedge,wereinsertedalong thehaftofsicklesabundantlydocumentedinseveral Cat-aloniansitesdatedtothepassagefromthe6thtothe5th millenniumBC(Gibaja,2003).Thissametypeofsickleis alsoknownatEarlyNeolithicsiteslocatedintheFrench regionsofLanguedocandProvence(Gassin,1996).Some isolatedsitesfromnorthernIberia,datedtotheendofthe 6thmillennium,yieldedsicklescomposedofasingle,large blade inserted diagonally (60◦–75◦)to thehaft (Gibaja, 2008;Terradasetal.,2010).Ofthesesites,themost spec-tacularfindcamefromthesubmergedlacustrinedwelling atLaDraga,whereawoodensicklewasfoundwithablade fragmentstillinsertedinthegroove(Palomoetal.,2011).

In sum, to date, three different types of sickles are knowntohavebeeninuseduringtheEarlyNeolithicin theIberianPeninsulaandtheGulfofLeon.Asevidencedin Fig.7,Cortic¸óisclearlyintegratescentralPortugalinthe Valencian/Andalusiantypo-technicaltradition, a conclu-sionthatraisestheimportantquestionofwhetherthese sickletypesarecorrelatetoaspecificsetofcultivatedcereal species.Ifso,itmaybeindicativeofEarlyNeolithiccrops andagriculturalpracticesinPortugal.

3.2. MightcropsandagriculturalpracticesintheEarly NeolithicofcentralPortugalbesimilartothesouthern Iberianpattern?

TheevidencepresentlyusedtoinferEarlyNeolithic sub-sistencestrategiesincentralPortugalcanbesummarized asfollows:

• faunalassemblages.ThenumberofEarlyNeolithicsites withfaunalremainsisscarce,asisalsothecorresponding numberofidentifiablespecimens.Theavailable zooar-chaeological evidence (Carvalho, 2008) points to two mainconclusions:

1domesticspecies–sheepand/orgoat(Ovisaries/Capra hircus)andcattle(Bostaurus)–arepresentatthe Earli-estNeolithicsites,attributedtothe5400–5200calBC timeperiod(Cardial)andthroughoutthe5th millen-niumBC,

2theseoccuralongsidewildspecies,mainlywildboar (Susscrofa) andred deer(Cervuselaphus), testifying mixedstrategiesofanimal exploitation.Therelative proportions between domestic and wild specimens clearly needlarger faunalassemblagesto providea strongerstatisticalanalysis;

• stableisotopesfromhumanbones.Lubelletal.(1994) producedapioneerstudyinPortugalinthemid-1990s basedonstableisotopeanalysisofhumanbonecollagen. Accordingtotheseauthors,therewasamajor subsis-tenceshiftattheonsetoftheNeolithic:Mesolithicgroups basedtheirdietonmarineandterrestrialfoods,whilethe Neolithicsubsistencewasmoredependentonterrestrial foodsources(herbivoremeatandplantfoods), presum-ablyreflectingtheintroductionofafarmingeconomic system.Morerecentlyobtainedstableisotopicanalyses, althoughlesssystematic,seemtocorroboratethese con-clusions(Carvalho,2008,2010);

• microfaunafromEarlyNeolithicdeposits.Accordingto theavailablepalaeontologicalrecord,twoMuridspecies areunknownduringthePleistocene(Póvoas,1991)but maketheirappearanceduringtheNeolithic:theAlgerian mouse(Musspretus)andthehousemouse(Mus muscu-lus).Thesespeciesareusuallyassociatedwiththespread and developmentof theNeolithic in Europe,the first inhabitingdeforestedareas,thelatterlivinginsedentary humansettlements.Bothspeciesarepresentfromthe evolvedEarlyNeolithic(5thmillenniumBC)onwardsat thePenad’ÁguaRock-shelter(Póvoas,1998),indirectly demonstratingtheexistenceofagriculturalplotsinthe immediatevicinitiesofthesite.Thisandotherfindsfrom laterNeolithicandChalcolithiccontextsofcentraland southernPortugalclearlycontradictthethesisofCucchi

38 A.F.Carvalhoetal./C.R.Palevol12(2013)31–43

Fig.4. Flintbladeusedincerealharvesting.Macroscopicphotosshowdiagonaldistributionsofpolishingonthebladesurface.

Fig.5. Sideretouchofsomesickleimplementsmadetoadaptandfacilitatetheirinsertioninthehandle.

Fig.5. Retouchelatéraledequelquesélémentsdefaucillepouradapteretfaciliterleurinsertiondansunmanche.

et al.(2005),accordingtowhich theserodentswould nothavecolonizedthewesternMediterraneanbeforethe IronAge.

Untilnowtheearliestrecordofcarpologicalevidence documentingagricultureincentralPortugalisdatedtothe Chalcolithic(c.3000BC)atthefamousfortifiedsiteofVila NovadeSãoPedro,whereburntremainsofwheat,barley, broadbeanandflaxwereexhumedduringthe1930–1950 excavations(Pac¸o,1954).Palynologicaldata,ontheother hand,isrestrictedintheregiontocoresmadeat differ-entlocationsintheTagusValley(VanLeeuwaardenand Janssen,1985;Visetal.,2008),whichprovidesinsightsonly intermsoflocalspecieschange,nothumanimpact.

Recently, Pérez et al. (2011)publishedan important synthesis of the Early Neolithic palaeobotanic evidence fromseveralsiteslocatedincentralAndalusia.According

totheseauthors,agricultureisdocumentedintheregion from 5300cal BC and is represented by a diversified assemblage of crops consisting of cereals, mainly free-threshing wheats–Triticum aestivum/durum–and naked barley–Hordeumvulgarevar.nudum–andpulses–broad bean (Vicia faba), pea (Pisum sativum) and lentil (Lens culinaris),alongwithflax(Linumusitatissimum)andpoppy (Papaversomniferum),whichhadbeencultivatedatleast sincetheendofthefollowingmillennium.When interpret-ingtheAndalusianpatternatbroaderscales,theauthors note the higher frequency of hulled wheats–einkorn (Triticum monococcum) and emmer (Triticum dicoc-cum)–intheneighbouringValenciaregion(Pérez,2005), which strongly contrasts with the Andalusian pattern despitetheircommonsickletypes.Thiscontrastgivesrise to theinterpretation that “the observable panorama in these earlymoments of agrariandevelopment is really

40 A.F.Carvalhoetal./C.R.Palevol12(2013)31–43

Fig.6. ObservedmodificationsontheinsertedsidesoftwooftheCortic¸óissickleimplements,wherelightpolishingnexttostriationsisvisible.

Fig.6. ModificationsobservéessurlescôtésinsérésdedeuxdesélémentsdefaucilledeCortic¸óis,oùunlégerpoliaccompagnantdesstriesestvisible.

Fig.7.SickletypesfromEarlyNeolithicIberia.1:sickleswithobliqueimplements;2:sickleswithlargebladeinserteddiagonally;3:sickleswithlarge bladesparalleltothehaft;4:sicklesoftypes2and3.

Fig.7. TypesdefaucillesduNéolithiqueanciendelapéninsuleIbérique.1:faucillesavecdesélémentsobliques,2:faucillesavecunegrandelameinsérée endiagonale,3:faucillesavecdegrandeslamesparallèlesàlapoignée,4:faucillesdetypes2et3.

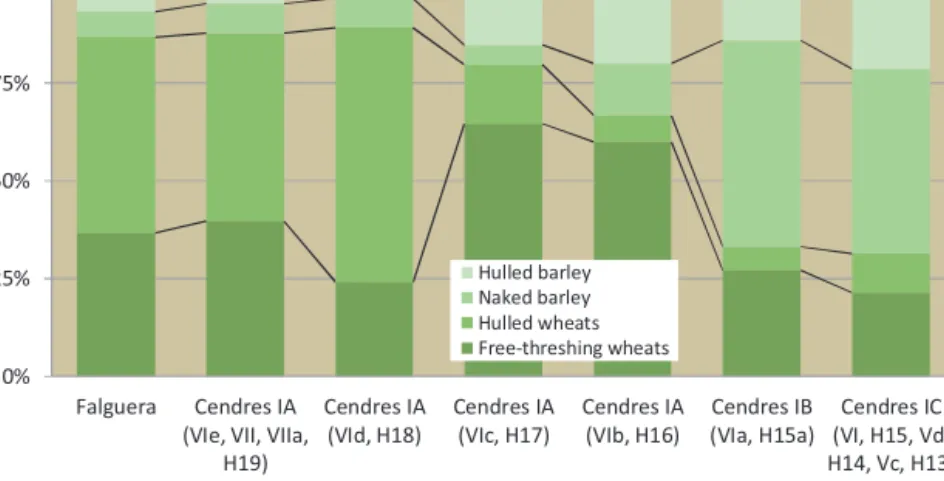

0% 25% 50% 75% 100% Falguera Cendres IA

(VIe, VII, VIIa,

H19) Cendres IA (VId, H18) Cendres IA (VIc, H17) Cendres IA (VIb, H16) Cendres IB (VIa, H15a) Cendres IC (VI, H15, Vd, H14, Vc, H13) Hulled barley Naked barley Hulled wheats Free-threshing wheats

Fig.8. EvolutionofcerealassemblagesintheNeolithicofValencia:Falguera(Pérez,2005:table1)andCendres(Badal,2009:table8.1).Approximate radiocarbonchronologies(calBC):Falguera:c.5500;CendresIA:5500–5200;CendresIB:c.5150;CendresIC:c.4800.

Fig.8. ÉvolutiondesassemblagesdecéréalesdansleNéolithiquedeValencia:Falguera(Pérez,2005:tableau1)etCendres(Badal,2009:tableau8.1). Chronologiesapproximativesauradiocarbone(calBC):Falguera:c.5500;CendresIA:5500–5200;CendresIB:c.5150;CendresIC:c.4800.

complex,withdifferentsituationswhichsurelyreflectthe presenceofdiversetraditions”inAndalusiaandthe Valen-cianregion,respectively (Pérezet al.,2011:68;Spanish original).

However, an alternative interpretation is likely. The regionaldifferencesincropsmaybebiasedbya coarse-grained picture of thechronostratigraphic sequences in Valencia. In effect, if hulled and free-threshing wheat remainsfromtheFalgueraRock-shelterandCendresCave are put into a detailed sequence, a trend of increasing percentagesofthelatterbecomesevidentthroughoutthe 5600–4000calBCtimespan(Fig.8),asBuxó(1997)stated. The inversion of therelation betweenboth types takes place in the middle of “Neolithic IA” (Cardial), around 5300cal BC, at thesame time as two other factors co-occur:1)thestartofincreasingpercentagesofbarley;and 2)thediffusionof agriculturein theAndalusianregion. Andalusiancrops,asdescribedbyPérezetal.(2011),are thereforecomparablewiththepatternemergingin Valen-cianlaterCardialsites,whilesickletypologiesremainthe samethroughouttheperiodinbothregions(seeprevious section).

According to several authors (e.g. Carvalho, 2010; Manenetal.,2007),arecompositionoftheEarlyNeolithic technological systems may have occurred in Andalucia andcentral/southernPortugal,formingaculturalentityof itsown withintheCardial tradition(asa resultoflocal Mesolithicand/orAfricaninfluences?).Althoughthereis notnecessarilyadirectrelationshipbetweensickle typolo-gies and crop assemblages (as the Valencian sequence clearlyshows),theCortic¸óisevidencereinforcesthe plausi-bilityoftheaboveview.Takenaswhole,thisviewallowsus tohypothesisethatcropassemblagesmayhavealsobeen thesame in centraland southern Portugaland Andalu-sia.Moreover,thediscoveryofbroadbean,free-threshing wheats andnakedbarley(4%, 35%,and 61%of remains, respectively),datedto4800–4600calBC,attheBuracoda PalaRock-shelter,inNorthPortugal(Sanches,1997),also seemstopointinthesamedirection.

Ifsuchahypothesisisconfirmedbyfutureresearch,it mayalsoallowthetranspositiontocentralandsouthern PortugaloftheconsiderationspresentedbyBuxó(1997: 171–172; Spanish original) concerning the correspond-ingNeolithicagriculturalregimes:“Thepresenceofpulses alongsidecerealsinthepeninsularNeolithicallowsusto supposetheexistenceofsomesortofcultivationsystem. Ifinatilledplotbroadbeans,lentils,peas,andgrasspeas aresownatthesametimeascereals,itisperfectly plau-siblethatthelatterproductsdonothavethesamestatus ascerealsand thattheircultivationismoresimilartoa formof horticulture.Ifin anotherplot pulsesare culti-vatedalternatingwithcereals,thesamecharacteristicsof theprevioussystemoccur[inthepalaeobotanicrecord]. We thus admit both systems have theirown logic and dynamics,butarenotmutuallyexclusive,andcould there-forecoexistuntilastabilizationofcultivatedareastakes place”.Thelattersystem,implyingcereal-pulserotation (rather than cereal-fallow rotation)and consequentlya permanent rather thanshifting agriculture,is now cur-rentlyacceptedbysomeauthorsasthemostlikelyinthe EuropeanNeolithic(Bogaard,2005;Isaakidou,2011).

However,theaboveconclusionisnotin goodaccord with the settlement pattern apparently emerging from fieldsurveysandexcavationsincentralPortugalwhere, withvery few possibleexceptions,the vast majorityof thesites weretemporary.Indeed, largeand permanent settlementslikethoseknowninotherIberianregionsare stilltobefound,althoughthepossibilityexiststhatthese sitesmaybeburiedinalluvialdepositsalongthebanksof theTagustributaries,requiringspecificsurveyandtesting strategiesandtechniquesinordertoidentifyandrecord them(Carvalho,2008).

4. Conclusions

Inthispaperwedescribesickleimplementsrecovered attheEarlyNeolithicsiteofCortic¸óis,whichwereanalysed throughuse-wear and integrated intheIberian context

42 A.F.Carvalhoetal./C.R.Palevol12(2013)31–43

(Fig.7).Asaresult,parallelswereestablishedwithEarly NeolithicAndalusianandValenciansites.Thisallowedus tologicallyintegratethePortugueseterritory–in partic-ular,centralPortugal–inthebroadercontextofNeolithic farminginsouthernIberia,notonlyintermsofsickletypes, but alsotentatively in terms of associated crop assem-blagesand agriculturalpractices and regimes.However, domesticplantsarenotyetdocumentedinthe archaeo-logicalandpalaeobotanicrecordsoftheEarlyNeolithicand wethereforeshouldertheburdenofgeneratingempirical expectationstobetestedbyfutureresearch.

Itisouropinionthatfurtherresearchisneededmainly in three domains. First, the geoarchaeological study of selectedrivervalleysinordertoevaluatesettlement mod-elsandtorecoverplantremainsfrompermanentsites,if existent.Second,use-wearanalysisofflinttoolstotestthe resultsoftheCortic¸óis analysis.Thirdand most impor-tantly,thesystematicflotationofsediments–whichisfar frombeingacommonprocedureinEarlyNeolithicresearch inPortugal–torecoverbothdirectandindirect(suchas microfauna)evidenceofagriculture.

Acknowledgments

Archaeologicalexcavations atCortic¸óis tookplace in the framework of the research on “The last hunter-gatherers and the first farming communities in the South of the Iberian Peninsula and North of Morocco”, a project directed by A.F.C. and J.F.G., funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology in 2008–2010 (PTDC/HAH/64548/2006). Use-wear analysis of sickle implements wascarried out in the context of the project “Origins and spread of agriculture in the South-WesternMediterraneanregion”directedbyLeonor Pe ˜na-Chocarroin2008–2013(ERC-2008-AdG/230561).

Theauthorswishtothanktwoanonymousreviewers fortheirusefulcommentsandsuggestionsthathelpedto improvethisarticle.

References

Anderson,P.C.,1983.Aconsiderationoftheusesofcertainbackedand “lustred”stonetoolsfromLateMesolithicandNatufianlevelsofAbu HureyraandMureybet(Syria).TravauxdelaMaisondel’Orient5, 77–106.

Anderson,P.C., 1988. Usingprehistoric stonetools to harvest culti-vatedwildcereals:Preliminaryobservationsoftracesandimpact. In:Beyries,B.(Ed.),Industrieslithiques.Tracéologieettechnologie. Archaeopress,Oxford(BARInternationalSeries,411),pp.175–195. Anderson, P.C., 1992. Experimental cultivation, harvest and

thresh-ing ofwild cereals andtheir relevance forinterpreting the use ofEpipaleolithicand Neolithicartefacts.In:Anderson,P.C. (Ed.), Préhistoiredel’Agriculture:nouvellesapprochesexpérimentaleset ethnographiques.CNRS,Paris,pp.179–210.

Anderson, P.C.,Deraprahamian,G., Willcox,G.,1991. Lespremières culturesdecéréalessauvagesetdomestiquesprimitivesau Proche-Orient néolithique: résultats préliminaires d’expériences à Jalès (Ardèche).Cahiersdel’Euphrates56,191–232.

Badal,E.,2009. ¿Cambiosambientalesy/oimpactoagrícola?In:Bernabeu, J.,Molina,L.(Eds.),LaCovadelescendres(Moraira-Teulada,Alicante). MARQ,Alicante,pp.135–140.

Bogaard,A.,2005.“Gardenagriculture”andthenatureofearlyfarmingin EuropeandtheNearEast.WorldArchaeol.37,177–196.

Buxó,R.,1997.Arqueologíadelasplantas.Crítica,Barcelona.

Cardoso,J.L.,Pimenta,J.;Mendes,H.,2012.Primeiranotíciasobreaestac¸ão doNeolítico antigode Cortic¸óis(Benfica doRibatejo,Almeirim).

Al-Madan17,177–180 [availableathttp://www.almadan.publ.pt/ AdendaElectronica.htm].

Carvalho,A.F.,2008.Aneolitizac¸ãodoPortugalmeridional.Osexemplos do Macic¸oCalcário Estremenho e doAlgarve ocidental. Univer-sidade do Algarve, Faro [available at http://ualg.academia.edu/ AntonioFaustinoCarvalho].

Carvalho,A.F.,2010.Lepassageversl’Atlantique.Leprocessusde néolithi-sationenAlgarve(SudduPortugal).Anthropologie114,141–178. Cucchi,T.,Vigne,J.D.,Auffray,J.C.,2005.Firstoccurrenceofthehouse

mouse(MusmusculusdomesticusSchwarz&Schwarz,1943)inthe western Mediterranean:azooarchaeological revisionofsubfossil occurrences.Biol.J.LinneanSoc.84,429–445.

Gassin,B.,1996.ÉvolutionsocioéconomiquedansleChasséendelagrotte del’Églisesupérieure(Var):apportdel’analysefonctionnelledes industrieslithiques.CNRS,Paris.

Gibaja,J.F.,2003.ComunidadesNeolíticasdelNorestedelaPenínsula Ibérica.Unaaproximaciónsocio-económicaapartirdelestudiodela funcióndelosútileslíticos.Oxford(BARInternationalSeries,1140). Gibaja, J.F.,2008. La funcióndel utillaje lítico documentado en los

yacimientosneolíticosdeRevilladelCampoyLaLámpara(Ambrona, Soria).In:Rojo,M.,Kunst,M.,Garrido,R.,García,Í.,Morán,G.(Eds.), Paisajedelamemoria:asentamientosdelNeolíticoantiguoenelValle deAmbrona(Soria,Espa ˜na).UniversidaddeValladolid,Valladolid,pp. 451–493.

Gibaja,J.F.,Carvalho,A.F.,Diniz,M.,2002.Traceologiadepec¸aslíticas doNeolíticoantigodoCentroeSuldePortugal:primeiroensaio. In:Clemente,I.,Risch,R.,Gibaja,J.F.(Eds.),Análisisfuncional.Su aplicaciónalestudiodelassociedadesprehistóricas.Oxford(BAR InternationalSeries,1073),pp.215–226.

Gibaja,J.F.,Ibá ˜nez,J.J.,Rodríguez,A.,González,J.E.,Clemente,I.,García,V., Perales,U.,2010.Estadodelacuestiónsobrelosestudiostraceológicos realizadosencontextosmesolíticosyneolíticosdelsurpeninsulary noroestedeÁfrica.In:Gibaja,J.F.,Carvalho,A.F.(Eds.),Thelast hunter-gatherersandthefirstfarmingcommunitiesintheSouthoftheIberian peninsulaandNorthofMorocco.UniversidadedoAlgarve,Faro,pp. 181–189.

González,J.E.,Ibá ˜nez,J.J.,1994. Metodologíadeanálisisfuncionalde instrumentostalladosensílex.UniversidaddeDeusto,Bilbao. Guilaine,J.,Ferreira,O.V.,1970.LeNéolithiqueancienauPortugal.Bull.

Soc.PrehistoriqueFr.67,304–322.

Ibá ˜nez,J.J.,Clemente,I.,Gassin,B.,Gibaja,J.F.,González,J.E.,Márquez, B., Philibert,S., Rodríguez,A., 2008. Harvestingtechnology dur-ing theNeolithicinSouth-West Europe.In:Long,L.,Skakun,N. (Eds.),“Prehistorictechnology”,40yearslater:functionalstudiesand theRussianlegacy.Archaeopress,Oxford(BARInternationalSeries), pp.183–196.

Ibá ˜nez,J.J.,González,J.E.,Rodríguez,A.,2009.Analysefonctionnellede l’outillagelithiquedeMureybet.In:Ibá ˜nez,J.J.(Ed.),Lesitenéolithique deTellMureybet.HommageàJacquesCauvin.Oxford(BAR Interna-tionalSeries,1843),pp.363–405.

Isaakidou,V.,2011.FarmingregimesinNeolithicEurope:gardeningwith cowsandothermodels.In:Hadjikoumis,A.,Robinson,E.,Viner,S. (Eds.),DynamicsofneolithisationinEurope.Studiesinhonourof AndrewSherratt.Oxbow,Oxford,pp.90–112.

Jensen,H.J.,1994.Flinttoolsandplantworking.Hiddentracesofstone agetechnology.AarhusUniversityPress,Aarhus.

Jorge,S.O.,2000.Domesticatingtheland:thefirstagricultural communi-tiesinPortugal.J.IberianArchaeol.2,43–98.

Keeley,L.H., 1980.Experimentaldeterminationofstonetooluses:a microwearanalysis.UniversityofChicagoPress,Chicago.

Lubell,D.,Jackes,M.,Schwarcz,H.,Knyf,M.,Meiklejohn,C.,1994.The Mesolithic-NeolithictransitioninPortugal:isotopicanddental evi-denceofdiet.J.Archaeol.Sci.21,201–216.

Manen,C.,Marchand,G.,Carvalho,A.F.,2007.LeNéolithiqueancienen PéninsuleIbérique:versunenouvelleévaluationdumirageafricain? In:Evin,J.(Ed.),XXVIeCongrèsPréhistoriquedeFrance.Congrèsdu

Centenaire:unsiècledeconstructiondudiscoursscientifiqueen Préhistoire,3.SPF,Paris,pp.133–151.

Pac¸o,A.,1954.Sementespré-históricasdocastrodeVilaNovadeS.Pedro. AcademiaPortuguesadeHistória,Lisbon.

Palomo,A.,Gibaja,J.F.,Piqué,R.,Bosch,A.,Chinchilla,J.,Tarrús,J.,2011. HarvestingcerealsandotherplantsinNeolithicIberia:theassemblage fromthelakesettlementatLaDraga.Antiquity85,759–771. Pérez,G.,2005.Nuevosdatospaleocarpológicosennivelesneolíticosdel

PaísValenciano.3rdCongresodelNeolíticoenlaPenínsulaIbérica. UniversidaddeCantábria,Santander,pp.73–82.

Pérez, G., Pe ˜na-Chocarro, L., Morales, J., 2011. Agricultura neolítica enAndalucía:semillasyfrutos.Menga. RevistadePrehistoriade Andalucía2,59–71.

Póvoas,L.,1991.FaunesderongeursactuellesetduPléistocènesupérieur auPortugal;lesévidencesdessitesdeAvecastaetCaldeirão.Memórias eNotíciasdoMLMGUC112,275–283.

Póvoas,L.,1998.FaunasdemicromamíferosdoAbrigodaPenad’Água (TorresNovas)eseusignificadopaleoecológico:considerac¸ões pre-liminares.RevistaPortuguesadeArqueologia1,81–84.

Roots,V.,2003.Towardsanunderstandingofhafting:themacro-and microscopicevidence.Antiquity77,805–815.

Sanches,M.J.,1997.OAbrigodoBuracodaPala(Mirandela)nocontexto daPré-HistóriarecentedeTrás-os-MonteseAltoDouro.SPAE,Porto. Terradas,X.,Clemente,I.,Gibaja,J.F.,2010.Miningtoolsandlithic produc-tioninaminingproductioncontextorhowcantheexpectedbecome unexpected.In:Capote,M.,Consuegra,S.,Díaz-del-Río,P.,Terradas,X. (Eds.),Proceedingsofthe2ndinternationalconferenceoftheUISPP. Oxford(BARInternationalSeries),pp.243–252.

Unger-Hamilton,R.,1983.Aninvestigationintothevariablesaffecting thedevelopmentandtheappearanceofplantpolishonflintblades. TravauxdelaMaisondel’Orient5,243–250.

Unger-Hamilton,R.,1985.Microscopicstriationsonflintsickle-bladesas anindicationofplantcultivation:preliminaryresults.WorldArchaeol. 17,121–126.

Unger-Hamilton, R.,1988. Methodinmicrowearanalysis.Prehistoric sicklesandotherstonetoolsfromArjoune,Syria.Oxford(BAR Inter-nationalSeries).

Unger-Hamilton, R.,1991.Natufianplanthusbandryinthesouthern LevantandcomparisonwiththatoftheNeolithicperiods:thelithic

perspective.In:Bar-Yosef,O.,Valla,F.R.(Eds.),TheNatufianculturein theLevant.Michigan,pp.483–520.

VanGijn,A.,1989.Thewearandtearofflint.Principlesoffunctional anal-ysisappliedtoDutchNeolithicassemblages.AnalectaPraehistorica Leidensia,Leiden.

VanLeeuwaarden,W.,Janssen,C.R.,1985.Apreliminarypalynological studyofpeatdeposits nearan oppiduminthelowerTagus val-ley,Portugal.IReuniãodoQuaternárioIbérico.GTPEQ/AEEC,Lisbon, pp.225–236.

Vaughan,P.,1985.Use-wearanalysisofflakedstonetools.Tucson. Vis,G.J.,Kasse,C.,Vandenberghe,J.,2008.LatePleistoceneandHolocene

palaeogeographyofthelowerTagusValley(Portugal):effectsof rel-ativesealevel,valleymorphologyandsedimentsupply.Quaternary Sci.Rev.27,1682–1709.

Yamada,S.,2000.DevelopmentoftheNeolithic:Lithicuse-wear analy-sisofmajortooltypesinthesouthernLevant.HarvardUniversity, Harvard.

Zapata,L.,Pe ˜na-Chocarro,L.,Pérez,G.,Stika,H.P.,2004.EarlyNeolithic agriculture in the Iberian Peninsula. J. World Prehistory 18, 283–325.

Zeder,M.A.,2008.Domesticationandearlyagricultureinthe Mediter-raneanbasin:origins,diffusion,andimpact.Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.105, 11597–11604.

Zilhão,J.,1997.MaritimepioneercolonisationintheEarlyNeolithicofthe WestMediterranean.Testingthemodelagainsttheevidence. Docu-mentaPraehistorica24,1942.