Universidade de Aveiro Departamento de Comunicação e Arte 2013

Pirjo Annikki

Haikola

Beyond the Artefact and Techno-centricity:

Towards Process-centric Understanding of

Architecture - Alternative Facilitation Strategies

and Proposals

Tese apresentada à Universidade de Aveiro para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Doutor em Design, realizada sob a orien-tação cientifica do Doutor João António de Almeida Mota, Professor Auxiliar do Departamento de Comunicação e Arte da Universidade de Aveiro.

This research is funded by the European Commission Framework 7 Marie Curie Programme, and in part by FEDER the Operational Competitiveness Programme — COMPETE — and by national funds, the Foundation for Science and Tech-nology — FCT — in the scope of project PEst-C/EAT/UI4057/2011 (FCOMP-Ol-0124-FEDER-D22700).

Doutor Mário Guerreiro da Silva Ferreira Professor Catedrático da Universidade de Aveiro

Doutor José Manuel Pinto Duarte

Professor Catedrático da Faculade de Arquitectura da Universidade Técnica de Lisboa

Doutor Heitor Manuel Pereira Pinto da Cunha e Alvelos Professor Auxiliar da Faculdade de Belas Artes da Universidade do Porto

DoutoraMaria Helena Ferreira Braga Barbosa

Professora Auxiliar da Universidade de Aveiro Doutor João António de Almeida Mota

Professor Auxiliar da Universidade de Aveiro (orientador)

o júri

I would first like to express my gratitude to my thesis supervisor, Professor João Mota for his warm encouragement, guidance and dedication. I would particularly like to thank Professor José Pinto Duarte, Professor Maria Beatriz de Sousa Santos, Professor Joaquim Madeira, Professor Jean-Bernard Martens, and Professor Ludger Hovestadt for their invaluable advice during my research.

I would also like to thank Professor Winy Maas, Ole Scheeren, and Professor Dietmar Eberle for their insights to architectural practice and all the architects and designers who contributed to this research through interviews.

In addition, I want to thank Ricardo Machado without whom the software prototype would not have been possible.

I also wish to acknowledge the European Commission Marie Curie Programme for a doctoral grant that supported my research.

Finally I wish to thank my parents, my brother, and Arno Verhoeven for their unconditional support.

architecture process, information management, communication, interaction techniques, user-centricity, information (aesthetic) visualization

The artefact and techno-centricity of the research into the architecture process needs to be counterbalanced by other approaches. An increasing amount of information is collected and used in the process, resulting in challenges re-lated to information and knowledge management, as this research evidences through interviews with practicing architects. However, emerging technologies are expected to resolve many of the traditional challenges, opening up new avenues for research. This research suggests that among them novel tech-niques addressing how architects interact with project information, especially that indirectly related to the artefacts, and tools which better address the social nature of work, notably communication between participants, become a higher priority.

In the fields associated with the Human Computer Interaction generic solutions still frequently prevail, whereas it appears that specific alternative approaches would be particularly in demand for the dynamic and context dependent design process. This research identifies an opportunity for a process-centric and integrative approach for architectural practice and proposes an information management and communication software applica-tion, developed for the needs discovered in close collaboration with architects. Departing from the architects’ challenges, an information management

software application, Mneme, was designed and developed until a working prototype. It proposes the use of visualizations as an interface to provide an overview of the process, facilitate project information retrieval and access, and visualize relationships between the pieces of information. Challenges with communication about visual content, such as images and 3D files, led to a development of a communication feature allowing discussions attached to any file format and searchable from a database.

Based on the architects testing the prototype and literature recognizing the subjective side of usability, this thesis argues that visualizations, even 3D visualizations, present potential as an interface for information management in the architecture process. The architects confirmed that Mneme allowed them to have a better project overview, to easier locate heterogeneous content, and provided context for the project information. Communication feature in Mneme was seen to offer a lot of potential in design projects where diverse file formats are typically used. Through empirical understanding of the challenges in the architecture process, and through testing the resulting software proposal, this thesis suggests promising directions for future research into the architecture and design process.

keywords

Processo em arquitetura, gestão da informação, comunicação, interação humano-computador, concepção centrada no utilizador, visualização (estética) da informação

palavras-chave

resumo A investigação sobre o processo projectual em arquitetura, na maior das vezes, centra-se no artefacto ou na tecnologia, motivo pelo qual precisa de ser contrabalançado por outras abordagens. Há um aumento substancial da infor-mação que é colectada e usada no processo projectual o que coloca desafios à gestão da informação e do conhecimento, como apresentado nesta investi-gação nos resultados das entrevistas efectuadas a uma seleção de arquitetos. Entretanto, as tecnologias emergentes são esperadas resolver muitos dos desafios tradicionais, abrindo novas áreas de investigação. Esta investigação sugere que entre essas novas técnicas, as que são dirigidas à forma como os arquitetos interagem com a informação no projeto, especialmente a que está indiretamente relacionada com os artefactos, assim como os instrumentos mais adequados para a natureza social do trabalho, nomeadamente a comuni-cação entre participantes, converteu-se numa grande prioridade.

Verificamos que nas áreas de conhecimento relacionadas com interação humano-computador prevalecem as soluções genéricas, embora sejam de-sejáveis soluções alternativas sensíveis ao contexto extremamente dinâmico em que se desenvolve o processo projectual. Esta investigação identifica uma oportunidade centrada no processo e na abordagem integradora da prática arquitectónica, e, propõe uma aplicação informática para a gestão da infor-mação e da comunicação, desenvolvida para as necessidades descobertas, fruto de uma colaboração próxima com uma seleção de arquitetos.

Partindo dos desafios colocados pelos arquitetos, desenvolveu-se um pro-tótipo de uma aplicação informática para a gestão da informação, Mneme. Este instrumento recorre ao uso de visualizações enquanto interface para dar uma visão global do processo projectual, facilita a busca e o acesso à infor-mação, assim como permite uma visualização das relações entre peças de informação. Os desafios com a comunicação de conteúdos visuais, como as imagens e os ficheiros 3D, guiaram o desenvolvimento de uma nova possibi-lidade na comunicação, a qual permite associar as comunicações e as dis-cussões anexas a qualquer ficheiro independentemente do seu formato, assim como, com a possibilidade de busca a partir de uma base de dados.

Fundamentada nos testes do protótipo com os arquitetos e nas publicações que reconhecem os aspectos subjetivos da usabilidade, esta tese discute e reivindica que as visualizações, mesmo as visualizações 3D, apresentam um potencial pouco explorado como um interface específico para a gestão da informação e da gestão do processo projectual em arquitetura. Arquitetos confirmaram que Mneme permitiu um visão global acrescida do processo projectual, permitiu localizar mais eficazmente conteúdo heterogéneo, assim como permitiu a visualização do contexto associado à informação. Os instru-mentos de comunicação de Mneme foram percepcionados como tendo um grande potencial nos projetos em design / arquitetura onde são tipicamente usados ficheiros tão diversos. Foi com recurso ao entendimento dos desafios do processo em arquitetura, assim como com os resultados dos testes com a aplicação informática proposta, que esta tese aponta para direções promis-soras para futura investigação sobre o processo projectual em arquitetura e

CONTENTS 11 LIST OF FIGURES 15 GLOSSARY 18 ACRONYMS 20 PART I 1 INTRODUCTION 23

2 RESEARCH QUESTIONS, OBJECTIVES, METHODOLOGY AND METHODS 27

2.1 Problem description and hypothesis 27

2.2 Research objectives 27

2.3 Methodology and methods of study 28

PART II

3 ARCHITECTURE PROCESS 39

3.1 Changing architecture process

Discussions with architects; understanding challenges and

discovering facilitation opportunities 39

3.1.1 Related (empirical) research into the architecture process 40

3.1.2 Process-centric practice 41

3.1.3 Dealing with complexity and dynamic context 42 3.1.4 Managing and communicating information and

knowledge 45

3.1.5 Transforming models of process 47

3.2 Conclusions of chapter 3 49

4 SYSTEMS FOR ARCHITECTURE (AND DESIGN) 51

4.1 Three paradigms by Mitchell 51

4.2 Hybrid design office – issues arising from mixing analogue and digital 51

4.3 Levels of user involvement 53

4.4 Discussion and criticism on the conventions of HCI 54

4.5 Design rationale 56

4.6 Integrated Design and Delivery Solutions and

Building Information Modeling 58

4.7 Communication and information and knowledge management 61

4.7.1 Communication tools 61

4.7.2 Communicating about visual content 62

4.7.3 Knowledge management in organizations 63 4.7.4 Information and knowledge management in the AEC industry 64 4.7.5 Discussion: Influence of semantic web technologies and

big data 65

4.8 Information visualization: Too much science too little design? 66

4.9 Conclusions of chapter 4 69

PART III

5 INTRODUCTION TO PART III 71

6 INTERVIEWS AND DESIGN 75

6.1 Problem framing and defining solution space 75 6.2 Developing and introducing the concept:

information management for architects 78

6.3 Developing visualization interface 81

6.3.1 Conceptual and architectural visual references 81 6.3.2 Creating the visualization, giving form for the

architecture process 84

6.4 Interviews: Demo video and paper prototype and

determining main needs 88

6.5 Creating the interactive prototype in collaboration with a programmer 90 6.5.1 Tension between the ‘ideal’ and the feasible 93 6.6 Description Mneme – information management and communication

application 93

6.7 Description Neem note – communication application 108 6.8 Testing the interactive prototype of Mneme and results 108

6.9 Conclusions of chapter 6 113

7 SYNTHESIS OF FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION OF THE PROTOTYPES 115

7.1 Analysis and discussion of interviews and testing Mneme 115 7.2 Implementation possibilities and challenges of Mneme 118 7.3 Implementation possibilities and challenges of Neem note

(and the communication feature in Mneme) 118

7.4 Conclusions of chapter 7 119

PART IV

8 CONCLUSIONS 121

8.1 Contributions of this thesis 121

8.2 Limitations of this study 121

8.3 Contributions and future development of Mneme 122 8.4 Contributions for alternative approaches in future research 123

ANNEX 1 Interview with Ole Scheeren 127

ANNEX 2 Interview with Dietmar Eberle 134

ANNEX 3 Interview with Winy Maas 140

ANNEX 4 Interview with Ludger Hovestadt 146

ANNEX 5 Short biographies, Ole Scheeren, Dietmard Eberle, Winy Maas 151

ANNEX 6 Excerpts from interviews with designers and architects 2010-2011 152

ANNEX 7 Excerpts from software prototype testing with project and

senior architects 2012 183

ANNEX 8 Provisional patent certificate 17 Jan 2012 200

ANNEX 9 Conversion to international patent certificate 18 Jan 2013 202

ANNEX 10 Summary of the invention 204

ANNEX 11 Patent Claims 206

ANNEX 12 Trademarke certificates: Mneme and Neem note 208

ANNEX 13 Funding and collaboration partners 212

BIBLIOGRAPHY 214

LIST OF FIGURES

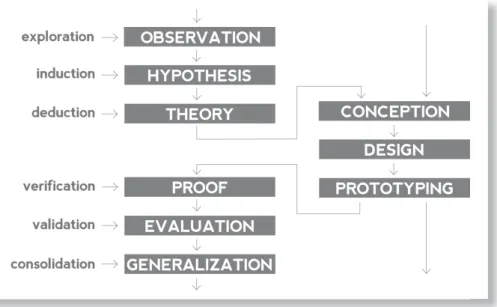

1. Major phases of design inclusive research. Derived from Horvath 2007, 6

by Haikola, Pirjo. 2010 31

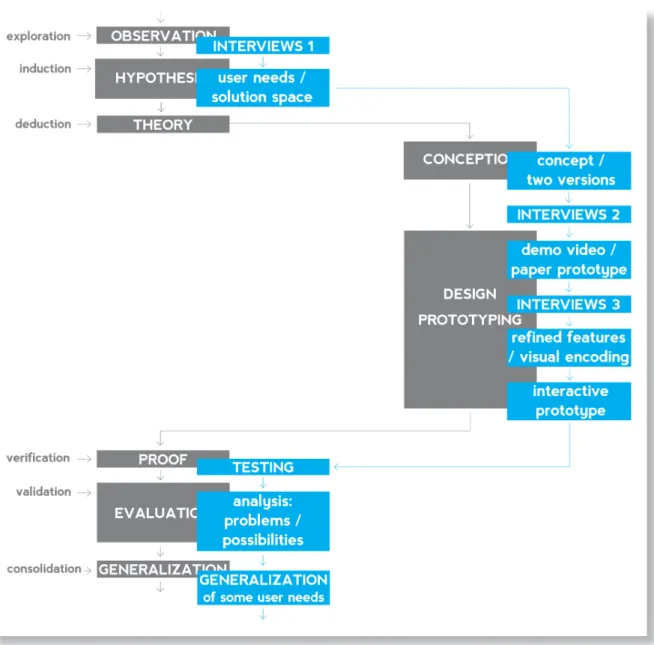

2. In grey major phases of design inclusive research. Derived from Horvath 2007, 6. In blue the interview sequence and software prototype development until user

testing by Haikola, Pirjo. 2010 36

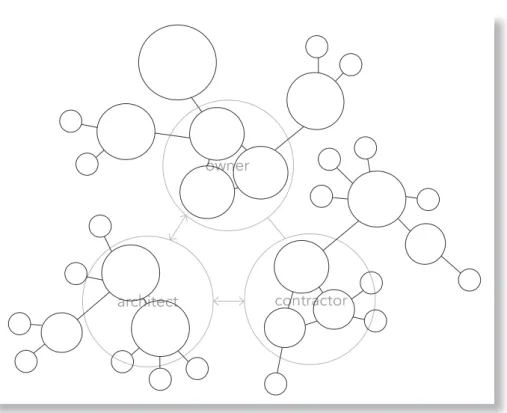

3. Illustration of the architecture process as a network, loosely derived from Tombesi 121,131 in Deamer and Bernstein 2010

by Haikola, Pirjo. 2011 48

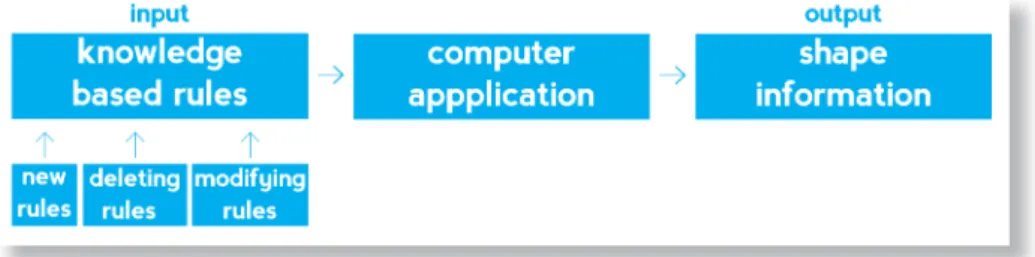

4. Mitchell’s first paradigm derived from Menges and Ahlquist 2010, 86-87

by Haikola, Pirjo. 2011 50

5. Interpretation of Mitchell’s second paradigm derived from Menges and Ahlquist

2010, 86-87 by Haikola, Pirjo. 2011 50

6. Screenshot from the WolframAlpha website Downloaded 13 July 2012

http://www.wolframalpha.com/ 53

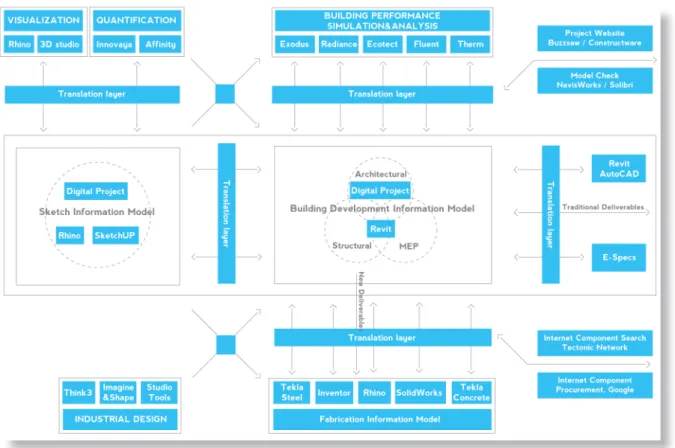

7. Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s software tools, derived from Bernstein 2010,195

by Haikola, Pirjo. 2012 60

8. “Typical digital software ecology based on a commerical tower project” derived

from Holzer 2011, 469 by Haikola, Pirjo. 2012 60

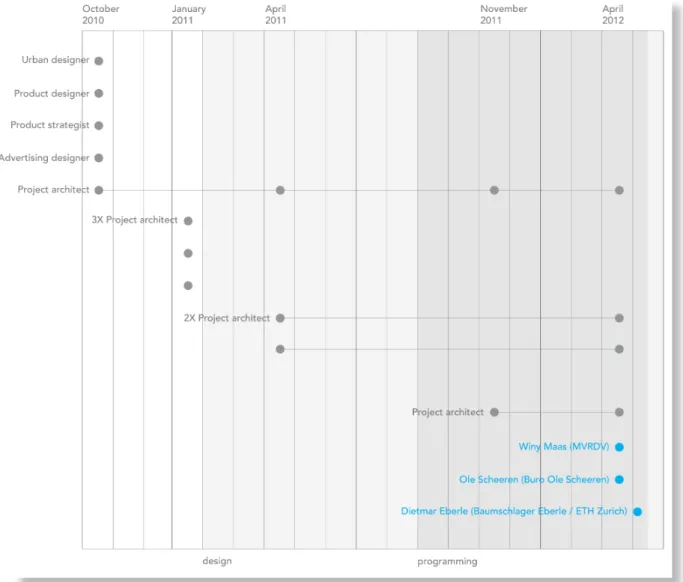

9. Interview process sequence, design and programming phases

by Haikola, Pirjo. 2012 72

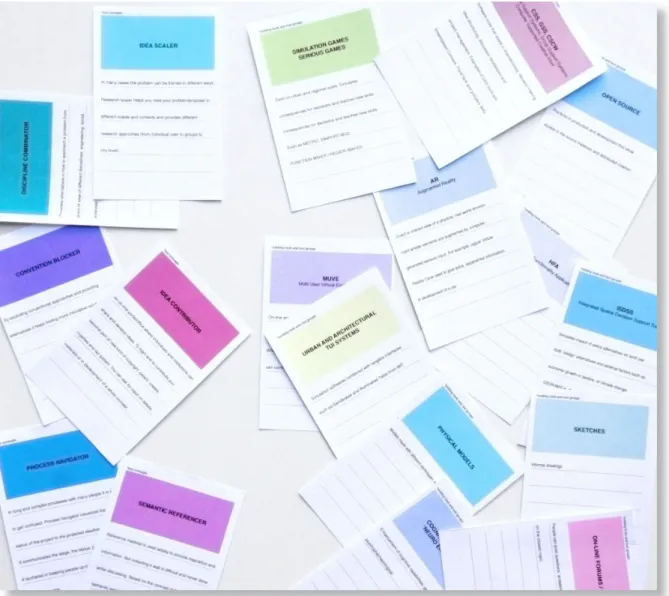

10. Cards used in the second interviews describing a variety of tool

groups Photograph by Haikola, Pirjo. 2012 77

11. The first two versions of the concept. Version two

by Haikola, Pirjo.2011 80

12. The first two versions of the concept. Version two

by Haikola, Pirjo.2011 80

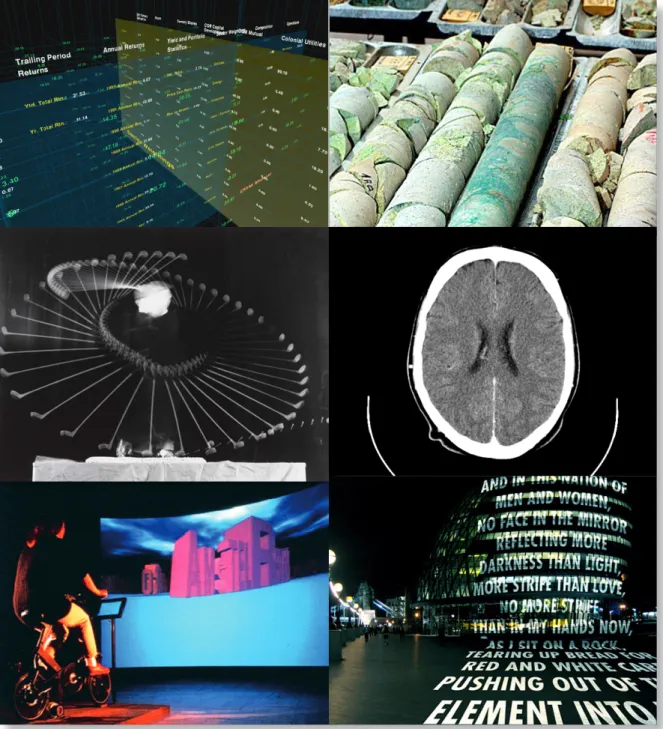

13. Visual references. From top left Cooper, Financial Viewpoints.

Inventing Interactive 2011. “Muriel Cooper: Information Landscapes” Downloaded 22 November.

http://www.inventinginteractive.com/2010/02/01/information-landscapes/ Drill core sample of Escondidos Chile

Construction Photography 2011. “Drill Core Sample Of Escondidas Exploration, Chile.” Downloaded 22 November.

http://www.constructionphotography.com/Details.aspx?ID=37787&TypeID=1 Computed tomography of human brain

Downloaded 23 November 2011

Wikipedia 2011. “Computed tomography of human brain”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Computed_tomography_of_brain_of_Mikael_H%C 3%A4ggstr%C3%B6m_%2814%29.png

Edgerton, Golf Swing

MIT Museum 2011. “Flashes of Inspiration: The Work of Harold Edgerton” Downloaded 22 November.

http://web.mit.edu/museum/exhibitions/edgerton.html Shaw, Legible City

CEEAC 2011. “Jeffrey Shaw” Downloaded 23 November. http://ceaac.org/en/artistes/jeffrey-shaw

Holzer, Protect Protect

Flying Dakini 2011. “Protect Protect Jenny Holzer. Downloaded 23 November. http://www.flyingdakini.com/2010/11/protect-protect-jenny-holzer.html 82

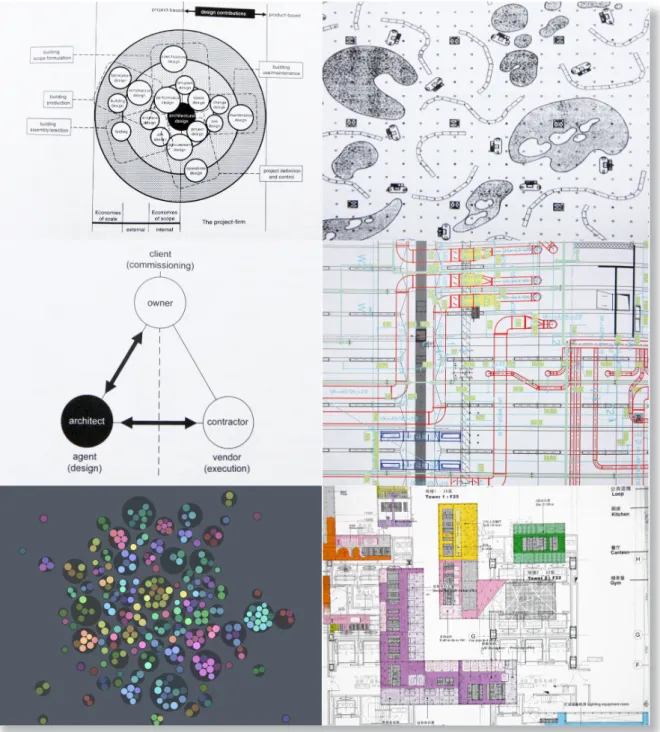

14. Visual references. Tombesi, The triangle of practice

Tombesi, Paolo. 2010. “On the Cultural Separation of Labour” in Building in the Fu-

ture: Recasting Labour in Architecture, edited by Deamer, P, Bernstein Phillip, G.

Non-stop City, Archizoom Associati 1970 in Hays, Michael. 2000. Architecture Theory Since 1968. Cambridge: MIT Press, 59

Tombesi, The industrial context of

a building project in Tombesi, Paolo. 2010. “On the Cultural Separation of Labour” in Building in the Future: Recasting Labour in Architecture, edited by Deamer, P,

Bernstein Phillip, G. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. 127 Detail of a drawing, sprinkles and ventilation

Kerez, Christian 2002-2008. in l’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui. 378: 177 Fizz, social group visualization, Bloom

+ Datavisialization.ch 2012. “Fizz, A Social Network Visualization” Downloaded 22 November.

http://datavisualization.ch/showcases/fizz-a-social-network-visualization/ CCTV floor plans OMA/AMO in Koolhaas, Rem, 2004. Content.

Koln: Taschen 496 83

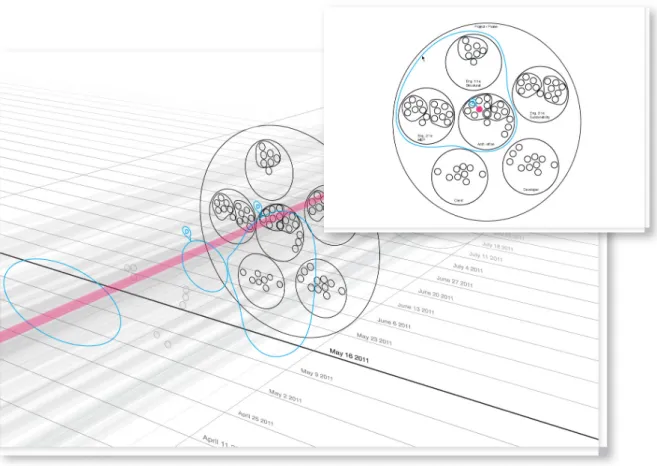

15. Timeline, weekly and daily views by Haikola, Pirjo. 2012 85

16. Timeline, blue selection plane by Haikola, Pirjo. 2012 85

18. Screenshot showing files and meetings by Haikola, Pirjo. 2012 87

19. Interviewed architect drawing suggestions on the transparent paper /

paper prototype Photograph by Verhoeven, Arno. 2011 88

20. Class diagram used to build the prototype by

Haikola, Pirjo., Machado Ricardo. 2011 92

21. Illustration of a generic default diagram, modifiable, while ideally retaining

compatibility by Haikola, Pirjo. 2011 92

22. Mneme software application registered trademark by Haikola, Pirjo. 2012 94

23. Screenshot showing the 3D interface by Haikola, Pirjo. 2012 98-99

24. Screenshot showing the list view by Haikola, Pirjo. 2012 100-101

25. Screenshot of the preview view by Haikola, Pirjo. 2012 102-103

26. Screenshot from Photoshop, showing the Mneme notes on top of an image.

by Haikola, Pirjo. 2012 104-105

27. Screenshot showing the preview option of seeing only the notes.

by Haikola, Pirjo. 2012 106-107

28. Neem note software application registered trademark

by Haikola, Pirjo. 2012 108

29. Answers for the quantitative questions in Likert scale

by Haikola, Pirjo. 2012 111

30. Direct quotes from the user testing

GLOSSARY

agent (digital/software) “[So]ftware that acts like an assistant to a user of an interactive interface rather than simply as a tool. [...] Agent software can learn from interaction with the user, and proactively anticipate the user’s needs” (MIT Media Lab. 2013).

artefact-centric In this research referring to research focusing on the designed artefact being worked on in the design

process, such as a building.

big data “In information technology, big data is a collection

of data sets so large and complex that it becomes

difficult to process using on-hand database man-

agement tools or traditional data processing ap- plications. The challenges include capture, curation,

storage,search, sharing, analysis, and visualization”

(Wikipedia 2013). “Data you leave behind as bread- crumbs as you move around” (Edge 2012).

client-server architecture “Architecture of a computer network in which many clients (remote processors) request and receive service from a centralized server (host computer). Client computers provide an interface to allow a computer user to request services of the server and to display the results the server returns. Servers wait for requests to arrive from clients and then respond

to them” (Encyclopedia Britannica 2013).

Building Information Modelling Intends software applications to construct a detailed digital model of a building allowing different parties and participants to work on the

same model (see page 58-61)

design inclusive research A methodology aiming to “provide a sound theo-

retical foundation and a robust methodological

approach for designerly inquiry to meet scientific

rigor.” [It] “opens up a possibility to blend system

atically two domains of learning: research and

design (Horvath 2007, 4-7).

Descriptive Coding “Descriptive Coding summarizes in a word or short phrase [...] the basic topic of a passage of qualita-

End-User Development An approach in computer science allowing the users to customize, or program software applica-

tions.

horizontality vs. verticality in software In this research verticality of software tools refers to their relatively closed and restricted nature, whereas a horizontal approach to software envi- sions better information exchange between them not only from the technical point of view but also from the users point of view. i.e. beyond interoper- ability.

information visualization “[Develop effective visual metaphors to mapping

abstract data” (Card er al. 1999, see page 60).

Information visualization is aqcquisition of insight

from an image (Spence 2010).

information aesthetic visualization “[I]nformation visualization techniques that com- bine information visualization techniques with crea-

tive design.” (Lau and van de Moere 2007, 1)

Integrative approach “...integrate useful knowledge from the arts and sciences alike[.] Designers, are exploring concrete interactions of knowledge that will combine theory with practice for new productive purposes[.]”

(Buchanan1992, 6)

In Vivo coding “[R]efers to a word or short phrase from the actual language found in the qualitative data

record.”(Saldaña 2009, 74)

Likert scale Unidimensional scaling method indicating respons- es along a range used in questionnaires and inter- views.

process-centric In this research refers to an approach looking at architecture or design process more holistically:

including communication, social aspects and

information indirectly related to the artefact in development.

semantic web “The Semantic Web is an extension of the existing

of expressing the relationships between web pages, to allow machines to understand the

meaning of hyperlinked information.” (Semantic

Web 2013)

synchronous vs. asynchronous Synchronous is happening at precisely the same time while asynchronous is the opposite of syn- chronous.

ACRONYMS

AEC Architecture Engineering and Construction

DR Design Rationale

EUD End-User Development

HCI Human Computer Interaction

BIM Building Information Modeling

IPD Integrated Project Delivery

PART I

1

INTRODUCTION

A personal and professional interest to study the design process together with findings already uncovered from the early interviews with designers and architects motivated this design inclusive research project (Horvath 2008). Further interviews with several practicing architects and literature made the specific focus increasingly clear. It became evident that research into the architecture process has been highly artefact and techno-centric with systems and tools focusing predominantly on issues such as building modelling, performance, simulation and analysis with particular interest, in recent years, on researching the challenges and opportunities of Building Information Modelling (Deamer and Bernstein 2010; Holzer 2011, 465; Rekola 2010, 265). However, as demonstrated by the interviews and evidenced through a review of the literature, other urgent challenges persist that demand attention. These include information and knowledge management, communication (Otter and Emmit 2008, 121) and human factors (Shen et. al. 2010, 30), which form the core focus of this thesis. These challenges could be approached through different means, for instance through team and project management in architecture (Sebastian 2005). However, a close look into the above-mentioned challenges pointed towards an insufficient support in digital systems and tools, an area providing interesting opportunities for research and design.

Architecture projects are increasingly designed and executed in a distributed collaborative environment, driven towards digitalization of the process and the documentation. However, despite this tendency, the interviewed architects complained about insufficient project records, lack of project overview, and cumbersome and inadequate communication systems. In their complaints the architects were referring to information both directly and indirectly related to the artefact. These notions informed the overall approach of this thesis to understand architecture and the systems and tools related to it more holistically. Thus, the approach in this thesis can be called process-centric with a more horizontal view on the systems and tools. It seems that emerging technologies, namely the semantic web technologies (Shen et al. 2010, 2,13), may help resolve many traditional challenges related to information and knowledge management such as searching and retrieving information from different media (Grudin 2006, 1-2). At the same time other challenges become a higher priority, such as investigating appropriate means and interfaces for specific users and user groups to access the increasing amount of project related information.

Furthermore, the research revealed a greater need for specificity of methods and solutions. This is evidenced through the practitioner interviews and through criticism towards certain still prevalent generic and inappropriate methods and techniques in Human Computer Interaction (HCI) and Information Visualization, which do not sufficiently acknowledge

the importance of prior knowledge, aesthetics and subjective experience among others (Barkhuus and Rode 2007; Chen 2005, 12-16; Hassenzahl 2004; Karapanos 2010). Thus, the methods and solutions in this research project were considered and developed from the perspective of the architects and aimed to take into account their specific needs and abilities. As a research means and designed outcome this thesis introduces an information and communication software application Mneme. The novel features include the 3D visualization interface and communication feature designed for discussing about mainly visual, heterogeneous content. Findings from the interviews and testing the software prototype demonstrate the relevance of the overall approach of this thesis and indicate promising directions for further research.

The focus in Part I of the thesis, is on describing the problematic, objectives, the methodology and methods of this study.

Part II opens the research with a chapter aiming to concisely describe the nature of the architecture process. The chapter suggests that a more empirical understanding of the process is needed and thus discusses the process mainly through interviews with renowned architects and with experienced practicing architects. Further understanding of the

architecture process is developed in the following chapter that discusses relevant aspects from different fields relating to systems and tools for architecture and design; including HCI, information visualization, architectural computing, and information and knowledge management. These two chapters are intended to formulate the basis and argumentation for the design inclusive part the thesis.

Part III describes the interview and design process in detail. From detailing the problem framing for the design proposal, to describing the chosen and developed interview methods and techniques, to design conception of the software application and the refinements of the proposal, towards the prototyping and collaborative efforts with a programmer. Part III arrives to the description, and the testing of the resulting interactive software prototype. The Part III ends with a synthesis of findings from the Part III and reflections on the implementation challenges and possibilities.

Part IV of the thesis presents the overall conclusions and contributions related of the thesis. It also discusses the contributions of the Mneme software proposal. The part IV further outlines both the limitations of the study, and discusses the suggested recommendations for future research into the architecture process, opening up alternative avenues for future research.

2

RESEARCH QUESTIONS, OBJECTIVES,

METHODOLOGY AND METHODS

2.1 Problem description and hypothesisIn this thesis the design process, more specifically the architectural design process, is the topic of research and design. The broader problematic revealed through practitioner interviews and literature is the prevailing artefact (the designed outcome)-, and techno-centricity of the research and development (Holzer 2011, 466; Rekola 2010, 265). This mainstream approach tends to overlook the overall view of the process, including social aspects, significant parts of relevant information, and concerns from the practitioners themselves (Deamer 2010, 19). This research suggests that what is called here the process-centric approach, combined with a user-process-centric and designerly integrative (Krippendorff 2004, Buchanan 1992, 6) approaches are useful to understand the problems from different levels (Conklin 2005, 4): from the level of the process and through the everyday challenges of the architects.

On a more detail level of the problematics, the artefact-, and techno-centricity has resulted in significant shortcomings in (software) tools for design. The tools are separated into tools dealing directly and indirectly with the artefacts. Due to this disconnection and overall verticality of the tools and systems, architects and designers appear to lack the overview and usable history of their projects, resulting in specific everyday challenges; the neglect of the content indirectly related to the artefacts and to the oversight of specific communication needs (of designers dealing with visual content and communication about heterogeneous content in distributed projects). Although many challenges traditionally pertinent to the tools may be resolved with certain emerging technologies, the urgent need to develop more appropriate systems and interfaces to deal with the increasing processual information remains.

Despite of the recent efforts and tendency towards networked and integrated practices, and tools that converge diverse content (Deamer, Bernstein 2010, Tombesi 2010, Krippendorff 2009, Aksamija and Iordanova 2011), the above-mentioned challenges still remain largely unrecognized and unresolved. Therefore, this research investigates and proposes domain specific content management and communication tools, and more appropriate interaction techniques, including the information (aesthetic) vsualization. This research recognizes the need to understand the practice from ‘within’, the need to collaborate closely with the end-users (in this case practicing architects), and to investigate appropriate levels and types of user involvement.

2.2 Research objectives

The objectives of this thesis are intimately related to “designerly integrative” (Buchanan 1992, 6) way of working and combining several fields of knowledge. The research in this

thesis is divided into two parts, which can be called the theoretical (Part II) and the practical (Part III). Consequently, there are also two areas of research objectives.

First, through the literature; exploratory interviews with senior and project architects; and interviews with principals of architecture offices, contribute to a better understanding of the contemporary architecture process and changes that are taking place. This improved understanding constructs and introduces a process-centric approach. The main interest here is to understand challenges that architects with different experience levels currently face in their daily work and the type of challenges that are emerging due to the changes taking place in the architectural practice. These challenges are mainly described with the following target in mind: to create strategies and proposals to facilitate these challenges. Utilizing the knowledge of the current and transforming architecture practice, one of the objectives is improved understanding of tools and systems for the design process: where are they useful and where do they fall short.

Second, based on Part II of the thesis, create facilitation strategies and proposals, leading to designs and prototypes. The aim is to create the designs in close consultation with architects to achieve appropriate domain specific proposals. The aim is to implement a proposal or proposals, which can be tested with the architects. The objective of the testing is to present some generalizable results that can inform further research and provide some insights into improving tools and systems for architectural practice. Although the goal of this research project is to achieve domain specific results, the assumption is that some of the results may also prove useful for other design and project-based practices.

The specific objectives of this research can be summarized as:

• To introduce the process-centric (versus the currently more common artefact-centric)

approach and how that can improve understanding of the practice and help create more appropriate facilitation strategies and proposals.

• By utilizing the ‘process centric’ and ‘integrative’ approaches, present facilitation

strategies and proposals for architecture practice.

• Through close consultation with practicing architects present domain specific findings and solutions to improve systems, tools, and interfaces (visualizations) of tools for architecture practice.

• Present a proposal(s) of a novel tool(s) that by integrating and learning from the

above mentioned notions is appropriate for the contemporary architecture practice by providing the needed overview and recognizes the need for more domain specific, dynamic and customizable (conversely to categorizing) tools.

2.3 Methodology and methods of study Methodology

There is a long ongoing discussion about what design research is and how it should be conducted. For the overall framework of methodology for this research I have used mainly three references (Eckert 2003; Horvath 2008; Horvath 2007). Horvath’s papers are a result of an extensive research into design methodologies and methods; both from design research

literature and promotion projects (117 of them), and therefore provide comprehensive references. Regarding the overall approach of this research, it is essential to mention that this is a design inclusive research thesis and the approach is therefore integrative, as explained by Buchanan.

“Designers, are exploring concrete interactions of knowledge that will combine

theory with practice for new productive purposes”

(Buchanan 1992,6). Meaning, several fields of knowledge may be required and each one is addressed only to the extent that is crucial for the objectives of the project.

Eckert describes a framework how research can be carried out in big teams, but she also addresses the possibilities and limitations of a doctoral student.

“Research in design, which should both advance knowledge and bring practical benefits to designers, is subject to tensions between conflicting needs and goals:

• between the need for valid, well-grounded research results, and the need for industry- supported research to have immediate practical applications;

• between the academic need to produce reportable results quickly from projects with limited resources, and the industrial need for powerful,

reliable, validated tools and techniques;

• between the need for large research groups to exploit their resources to make major advances, and the need to allow isolated researchers to make

effective contributions;

• between the need for students to achieve intellectual independence in their own research, and research leaders to achieve larger-scale, longer-term

results;

• between the need for students to develop skills in different aspects of applied research and their need to focus to achieve results in a reasonable

time. The crucial problem in applied design research is that achieving the usable results we aim for requires more effort than a single doctoral student can contribute or a single research grant will pay for.” (Eckert 2003, 3)

These conflicting needs and goals mean reconciling between what is desired and what is possible within a PhD project. In the above list, although comprehensive, Eckert misses one aspect that became evident in this research, the issue of time and relevance. This research deals with the digital artefacts and architectural computing and therefore relevance of, in particular the design part, is short as technology and consequently the practice change rapidly. I suggest an added point to the list: tension between the time the results of the study are relevant and the time needed to conduct thorough research and design. These tensions need to be considered also regarding the multi-disciplinary nature of design research - when deciding on the one hand what is necessary for the theoretical grounding of the research from different fields and on the other, how far the design part of the PhD project is taken. Eckert also describes an eight-part spiral of applied research: “Empirical

studies of design behavior; evaluation of empirical studies; development of theory and understanding it; evaluation of theory; development of tools and procedures; evaluation of tools; introduction of tools and procedures, dissemination; evaluation of dissemination.”

(Eckert 2003, 6) In her opinion a doctoral student can only adequately address two or three out the eight aspects. This research mainly focuses on three, the “empirical studies of

design behaviour”, “the development of tools and procedures” and “evaluation of tools”.

Where Eckert provides the framework for applied research and helps in understanding the possibilities and limitations, Horvath proposes and explains in detail an ontology of methodologies (in industrial design engineering): 1] research in design context, 2] design inclusive research and 3] practice-based design research (Horvath 2007,1).

Studies in the first methodology can be in short described as “mono-disciplinary, their

set-up corresponds to that of the ‘classical’ empirical approaches […] experimental inquiries are conducted purposefully to get insights, or to achieve enhancement in various contexts, such as human behaviours and reflections, artefact qualities, and interactions and impacts on natural/artificial surroundings.”

The objective of the second, design inclusive research “is to provide a

sound theoretical foundation and a robust methodological approach for

designerly inquiry to meet scientific rigor”. [It] supports analytic disciplinary

and constructive operative design research by the involvement of various

manifestations of design in research processes as research means, integrates

knowledge of multiple source domains, and lends itself to multi-disciplinary

insights, explanations and predictions, but can also generate knowledge, know

how, and tools for problem solving.” [And] opens up the prospect to blend

systematically two domains of learning: research and design.”

The third methodology, practice-based research positions the practitioner as an observer, or a researcher. There are several views on how practice-based research should be defined. Some define it as “research by design to describe a combination of research and design in

which an evolving artefact is employed as a research means in the process” (Horvath 2007,

4-8).

Research questions in this study originate from the practice of design and architecture; they are rather practical challenges designers and architects face in their work than

theoretical questions. These challenges also more urgently demand more investigation on proposals and possible solutions than theoretical contribution. Design inclusive research methodology seemed the most appropriate, as it enables more scientific rigor and

generalizability of solutions than practice-based research. The diagram by Horvath illustrates the main phases of design inclusive research (Fig. 1).

Methods of Study

The methods used in this study can be described as belonging within the broad framework of user-centred design. Since user-centred design includes a variety of methods and is rather general understanding that users are involved in some ways, the methods were informed more specifically by the field of Human Computer Interaction (HCI), Information Visualization and a selection of qualitative research methods. It is important to mention two main things that influenced the selection of methods. Firstly the methods needed to correspond with the goal of understanding the specific needs and opportunities in architecture. Thus, some interview methods and techniques were adapted or ‘enhanced’. Secondly the methods were chosen to be appropriate for developing a software application proposal with a visualization interface.

User involvement could be described as ‘light’. They were ‘consulted about their needs, observed and participated in usability testing’. More intensive user involvement could entail user participation throughout the process as partners in design (Abras et al. 2004), commonly referred to as participatory design. However, in designing digital systems,

the downfall of user-centred design and participatory design are that the users

are only involved during “design-time”. Accommodating their ”use-time” needs

requires more active role from the users, commonly referred to as End User

Development (EUD).

(Fischer and Giaccardi 2006, 432). Although the resulting prototype could not incorporate this approach, this thesis acknowledges that in real implementation due to the dynamic nature of architecture process, any tool or system should be appropriately customizable. The “creative design actions” phase of the design inclusive research methodology (Horvath 2008,18) includes two roles for a single researcher: designer and researcher. This is in

Figure 1. Major phases of design inclusive research. Derived from Horvath 2007, 6

line with the action research approach, which was chosen for the method of working and collaborating with the architects and designers. In this approach both the researcher and subjects are “deliberate and contributing actors” (Berg 1989, 96).

Regarding the software application proposal and in particular the visualization interface, the following categorization of Information Visualization methods by Plaisant informed the options and the overall scope of the interviews and testing the proposal with architects.

“1: Controlled experiments comparing design elements. The studies in this category might compare specific widgets.

2: Usability evaluation of a tool. Those studies might provide feedback on the

problems users encountered with a tool and show how designers went on to

refine the design.

3: Controlled experiments comparing two or more tools. This is a common type of study. […] Those studies usually try to compare a novel technique with the state of the art. 4: Case studies of tools in realistic settings. This is the least common type of studies, e.g. The advantage of case studies is that they report on users in their natural environment doing real tasks, demonstrating feasibility and in-context usefulness. The disadvantage is that they are time consuming to conduct, and results may not be replicable and generalizable.”(Plaisant 2004, 2)

The points 2, 3 and 4 were considered as consistent with the objectives of this research. However, points 3 and 4 were not feasible due to time constraints and due to the early development stage of the software prototype. Thus, the most appropriate methods for this project fall within ‘usability evaluation of a tool’ category. Examples of this type of method include Graham et al. (2000), Kennedy et al. (2000) and more generally by Shneiderman et al. (2005). Although the methods in this thesis are informed by HCI and Information Visualization literature (including Card and Mackinlay 1997; Spence 2001; Shneiderman 1996; Shneiderman 2003), this research also led to some criticism of the mainstream methods and how usability should be understood. This refinement of the methods is further elaborated in the section 4.4.

Who and how many to interview?

The decision on who and how many people should participate in the interviews and user testing was informed by several factors. For the ‘who’ the most important criteria were to select experienced architects with diverse background (countries where they were from and countries and offices they had worked at). As the problems expressed in the first interviews and based on my work experience were more related to and evident in bigger projects with large teams and several parties it was also important to select architects from bigger offices. Thus, an international group of architects with experience in several significant medium and large size offices (medium 20-49 employees, large 49-150 employees) were selected for the sample. The decision of ‘how many’ is a combination of literature recommendations and

constraints of the study. Graham et al. only used a few expert representatives, explaining this choice with mainly qualitative concerns of the study (Graham et al. 2000, 793). Overall the scope of their study has several similarities with this research. Shneiderman and Plaisant recommend identifying 3-5 diverse expert users (although in discussing ‘multi-dimensional

in-depth long-term case studies’ instead of earlier phase interviews and testing).

However, they note that increasing the sample size will improve the reliability, validity and generalizability of the results (Shneiderman and Plaisant 2006). Isenberg et al. acknowledge the compromises that have to be made between sample sizes and how much data can be processed when using qualitative research methods (Isenberg et al. 2008, 3). Due to the limited time and resources available we could not include a large sample, but rather opted to select the sample, as explained above, to be diverse and experienced considering the problems we wanted to address. Overall 14 designers and architects were interviewed. Of the 14, four architects participated more intensively in the development and testing of the software prototype. I suggest some of the problems and needs they expressed can be generalized owing to their knowledgeable, engaged and insightful participation.

How and what to measure from the interviews and testing?

How to conduct the interviews and user testing in software development includes a contentious choice: whether to measure effectiveness and efficiency (quantitative) or satisfaction (qualitative), or as discussed more in detail in the section 4.4 ‘pragmatic’ or ‘hedonic’ aspects (Hassenzahl 2004, 320). In software development and user testing it is common to measure task completion times, error rates and learning time among other quantifiable results. User satisfaction on the other hand is measured through overall preference and attitudes towards the software and interface (Karapanos 2010, 12-13). Considering the objectives of this research and the development level of the prototype, measuring effectiveness and efficiency, such as task completion times, is too detailed of an approach. Also as the section 4.4 discusses, perhaps measuring the “subjective side of

usability” should have a bigger emphasis than studies commonly acknowledge (Hassenzahl

2004, 321).

Thus, all of the interviews in this research were semi-structured allowing the interviewees to explain more freely how they felt about different issues and proposals and use their own terminology. The interviews attempted to understand both the functional aspects, and the appealingess of the proposal. The last user tests included also questions measured with a Likert scale, however the main emphasis was on the qualitative questions. Chapters 6 and 7 describe the interview and testing process and the analysis and findings in detail.

Coding and interpreting the interviews during the different phases of the software proposal development

The following section clarifies the coding and interpretation process of the interviews, how they were conducted and why certain interpretations and choices were made.

First questions before beginning the interview process were: who and how many people to interview, how many times and what to record and how to interpret? Many of these questions are already answered in the above sections through finding appropriate research

methods that helped in determining sample size and sequence of work in a context of developing a software prototype. What the methods do not address completely is what to record and how to interpret the findings. In that qualitative research methods were consulted and used to an extent that seemed appropriately rigorous. Regarding what to record, I agree with the postmodern perspective that all reports are necessarily incomplete and partial, thus one has to determine what can be considered “sufficient quality

data” (Saldaña 2009, 15) on project basis. In analysing the content, the approach was

interpretative (Berg 1989, 266) from a point of view and due to the objectives of a designer. For a researcher working in an unfamiliar discipline, understanding the subjects, their terminology and environment can be challenging. Owing to my background in design and work experience in architecture I believe having had an advantage to filter out what were the really important issues in the practice and position the comments in a broader context of the discipline.

The interviews

The first two sets of semi-structured interviews informed the problem framing and defining the solution space (see section 6.1). First set of interviews included designers from several disciplines and countries. They described their design process and challenges in the process. Most intriguing and urgent challenges seemed to be in architecture, the discipline in which I have also been involved in during the past years. Therefore, the second set of interviews focused on interviewing four architects from central and south of Europe with experience in medium and large-size offices. These second interviews were structured around tool groups and directions for new tool concepts. The tool groups and concepts were used to tease out more clearly the problems and needs in the practice and to define a possible solution space. These interviews were broader and the architects described a variety of problems. However, issues consistent with the gap in literature could be identified, which helped defining a solution space for the design proposal.

The problems and user needs were then translated into a design concept (see section 6.2). The process of translating the user needs into a concept is perhaps the most interpretative moment, where the design choices depend on the one hand on the interplay of the major codes (Saldaña 2009, 187) and on the other on the expertise, capabilities and objectives of the designer(s). I created two versions of the concept and discussed them with three architects. Two of the interviewed architects were the same as in the previous interviews and one was new to the project. The versions showed the main functions in a sequence of images, not yet interactively. Based on these interviews one version of the concept was selected for further development.

Within the overall concept the user needs needed to then be translated into functions of the software proposal. In order to create a testable prototype and get assistance and advise in refining software functionalities, a software programmer joined the project for seven months. Additionally two professors from computer science advised during the prototype development (see section 6.5). The design of the concept, prototype, visualizations, interface and main functionalities were my responsibilities as the principal researcher. At this stage we made improvements to the concept and in order to properly understand

and further validate the functions, I interviewed two of the architects again (see section 6.4). This time I used a combination of a video demo and a paper prototype, accompanied with transparent tracing paper. It seemed that most functions were present. However, additions and improvements were suggested. The coding approach loosely combined In Vivo and Descriptive Coding (Saldaña 2009, 70-74)

After the paper prototype we made further improvements and the programmer completed the implementation of the interactive prototype and I designed the visual encoding and interaction (see sections 6.3.1, 6.3.2). I tested the prototype with the four architects (see section 6.8). In the tests they first created a new project and used planning related features. After they used a simplified dummy project. In the dummy project the architects performed sets of tasks. After each set of tasks they were asked questions to rate the task (in five point Likert scale) and also elaborate freely on their experience. I also asked the architects to explain their impression and opinion on the visualization and elaborate on the appealingess of the prototype. A mixed approach of In Vivo and Descriptive Coding (Saldaña 2009, 70-74) was used to analyze the interviews.

The findings of the post-study are described in detail in the Chapters 7 and 8. They

“comprise verification, validation, and generalisation. The actions are orientated to: the verification of the hypotheses, the constructed theory and the outcome of the design processes, the internal validation of the research methods and the design methods, the external validation of the findings of the research, and the results of the artefact development, the consolidation of the results by matching them against the existing body of knowledge, and by generalising them towards other applications” (Horvath 2008, 18).

The above-mentioned actions for post-study in this research consisted of evaluating the interviews and user-testing methods and results, as well as findings regarding the design proposal. The design proposal was also evaluated reflecting its novelty and appropriateness to the architecture practice compared to existing systems and tools. Due to certain choices explained earlier in this section, such as to interview only experienced practicing architects, and limitation due to time and technology this thesis aims to present findings that can inform novel directions for further research. Figure 2 on the next page presents the process of this research project overlayed with the major phases of design inclusive research by Horvath.

Figure 2. In grey major phases of design inclusive research. Derived from Horvath 2007, 6. In blue the interview sequence and software prototype development until user testing.

PART II

3

ARCHITECTURE

PROCESS

3.1 Changing architecture process

Discussions with architects; understanding challenges and discovering facilitation opportunities

“It would be great if each of you would generate/be responsible for a

perma-nent record of the process so that not every presentation becomes a desperate

improvisation. “

[1]The different sections in this chapter intend to concisely sketch the nature of the architecture process and present the main argument of this research project through interviews with internationally renowned architects and through insights from exploratory interviews with practicing senior and project architects from acknowledged offices. Incorporating knowledge from different fields supports this empirical work and is further substantiated in the following chapters. Whereas other parts of this thesis focus on

explaining in greater detail certain fields of knowledge, or the interview and design process, this chapter takes a broader perspective and introduces the topics, issues and tendencies in the architecture process revealed during the research.

The architecture process can be in short described as a messy and terribly slow collaborative activity (Hawthorne 2010, 70), taking place in a rich context of interdependent factors. In order to understand the current architecture process and changes that are taking place, incorporating knowledge from different fields and interviewing architects with different levels of experience were crucial for this research. Through understanding the dynamic nature of context, increasing complexity and distributed creation and execution, this chapter arrives to a notion that architecture process needs to be understood as information produced and used within projects and that the current model of practice needs to be challenged and new facilitation strategies proposed. This research sees architecture from a process-centric view, conversely to the common artefact centric and techno-centric view: as information exchange in a network of parties – as a social and informational system.

[1] A note from Rem Koolhaas to all staff members. Shown at the OMA/Progress exhibition Barbican, London October 2011 - February 2012

The interviews

In part, this chapter is informed by exploratory interviews, embedded in this design inclusive research project. These interviews with practicing project and senior architects from central and south of Europe and China represent internationally acknowledged offices. The interviews were done in several semi-structured sessions during this research project. This chapter also references renowned architects, interviewed specifically for this thesis: Ole Scheeren (Annex 1 and 5), Winy Maas (Annex 3 and 5), and Dietmar Eberle (Annex 2 and 5). These architects were chosen to represent different approaches to architectural design; from an approach influenced by the contemporary dynamic Asian context, to the Dutch conceptual design, and to the pragmatic and methodological Swiss approach. The interviews were semi-structured, focusing on understanding the approach and methods of each architect and office and in particular challenges they face in bigger projects.

Interviews also aimed to uncover which tendencies are influencing architecture practice. All of the interviewed architects represent medium to large-size offices. Extra large offices (Kolleeny, Linn 1999) are not included in this research; thus, some concerns and findings discussed in this chapter may not apply in that category. Additional discussion with Ludger Hovestadt (Annex 4) enriches the view on the architecture process with his perspective on emerging technologies. This chapter of course has its limitations. As Cuff observes, there can be a difference between “what architects say and what they do” (1991, 7). Although having to do without an extensive immersion to several offices and architecture practice I believe that based on the interviews, literature and some inside knowledge about architecture practice this chapter is able to present interesting and useful findings.

3.1.1 Related (mainly empirical) research into the architecture process

There appears to be significantly more publications about the design process in general, than about the architecture process. The few research publications about the architecture process are likely to mention the rarity of the subject matter. I will not go into the known references about the design process in general here, but will outline some specific references related to the architecture process, and some that have directly influenced this research.

The most comprehensive account and analysis of the architecture practice may still be

Architecture: The Story of Practice by Cuff from 1991. It appears that Cuff’s background

both in social sciences and architecture allows her to capture many still essential elements of the architecture practice through in depth observation. She discusses many aspects of the practice: the roles of different level architects, architects’ relationship with clients, the education of architects, the design problems, and different participants to the architecture projects, among other subjects. Although not very recent, her book is certainly a useful reference for understanding the practice. However, she does not attempt to provide solutions or strategies to challenges, and naturally cannot provide insights into many of the contemporary challenges. A much more recent (2009) publication by Yaneva, Made

by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture: An Ethnography of Design, appears to share

some similarities with Cuff’s study. Unfortunately, it does not offer any more insights into the contemporary architecture process. Perhaps due to Yaneva’s background as an

ethnographer, certain aspects of the process at OMA fascinate her. She thus focuses on detailed accounts and stories of what is going on in the office, mainly related to the use of physical models. PhD study by Sebastian (2007) bears resemblance to this study in some aspects. He aims to describe the characteristics and difficulties in increasingly complex architectural projects through interviews and case studies, however, through management of projects. Sebastian also recognizes that focus of the other studies is in the artefacts and that the description of the process is generally limited. The case studies emphasize social complexity and this is reflected in his proposed concept, “managing-by-designing” which focuses on “participative role of design management through creative teamwork” (Sebastian 2007, 93). Although more general, discussing both design and architecture, Lawson’s frequently cited book What Designer Know (2004) has influenced this study. Lawson’s observation that

“design is after all a process of creating, manipulating and managing information”

(Lawson 2004, 81) is shared by this research. Also his recognition of design as a social process where all parties are an important source of knowledge requiring direct lines of communication is also an insight that the architects interviewed for this study confirmed. Along the same lines, Achten discussing similarities and differences between industrial design and architecture process outlines that team design has not been studied to great extent (Achten 2008, 15-27). However, he focuses on discussing a theoretical framework, and thus observations on case studies remain on a general level.

Although Cuff and Lawson in particular discuss many aspects of the architecture practice in detail, they focus on analysing separate aspects of the practice, whereas for this research the acknowledgement of the process as a flow of the information between the participants is fundamental. Many of the subjects discussed by Cuff and Lawson such as the drawings, conversations, and knowledge are here situated and discussed within the trajectory of the process and looked through opportunities to improve the process.

3.1.2 Process-centric practice

To emphasize the process can be a contentious stance, since architecture process is a term used both in a negative and positive sense. The negative views often emphasize the cumbersome activity, increasing bureaucracy, distribution of the process, diminishing influence of the architects and commercialism. These negative connotations and

contradictory attitudes towards process originate already from the first edition of the AIA Handbook of Architectural Practice in 1920 (Wickersham 2010, 25).

They continue to be expressed in Rem Koolhaas’ statement of one of the first large

modern buildings the Empire State Building, as a pure product of process and thus

having no content (Koolhaas 1978), like processed food devoid of flavour.

These notions continue to surface with even greater frequency. An example involves the Why Factory think tank questioning when different inputs shift from productive to obstructive and conclude that the city is “held hostage by the procedure” (Maas et. al. 2009). The positive views of the process emphasize the need for more professional, organized and systematic architecture (Wickersham 2010, 25) or discuss process as methods of working such as MVRDV’s complete surrender to it as a driving force of their conceptual experimental design (Annex 2). In this thesis the view is neither negative, nor positive; rather it recognizes that it is no longer useful to look at the architecture and design process as separate pieces of activities (such as drawing, brainstorming or discussing), or looking only at one aspect (such as creativity), or only through the common artefact- or techno-centric views. In fact the interviewed renown architects, as well as the project and senior architects, expressed challenges related to mainly the lack of overview, information and knowledge management and communication. This leads to a need to understand the process as the whole meandering trajectory from the beginning of the project towards and until the finished artefact and

beyond. The architecture process needs to be seen as information (directly and indirectly related to the artefact), its exchange and coordination between all parties. The process is

“synthesis of creation and execution” (Frampton 2010, 36).

The term practice is often interchangeably used to describe: firm practices; firm; customary activities the practitioner does; the discipline. In this research I refer to practice as customary activities a practitioner does during the architectural process, although these activities are always necessarily embedded within firm practices in the case of architecture. It is necessary to understand that there is no single architecture practice. The activities and procedures during the process change dramatically, according to Eberle, based mainly on the dimension of the project, which corresponds to the organizational capacity of the client. To illustrate his point, Eberle describes four categories of projects and states that in order to deal with the bigger scale of projects, the organization of architecture offices and firm practices needs to change from their currently common structure to meet the increasing demands of the projects and of the clients. However, he also warns that projects can be too big. As a result responsibility gets ‘atomized’ making the bureaucracy ‘tremendous’ and consequently the process ineffective.

Both Eberle and Scheeren emphasized the importance of understanding the social

context of a project. In Scheerens words one needs to understand “what a place, a

culture, the users, or the client can really become, or can do or cannot do”.

3.1.3 Dealing with complexity and dynamic contextWhen looking at something through the process-centric view, the terms systems and complexity are useful. How something is perceived as what Bertalanffy calls a “general

science of wholeness” (1969) requires determining its boundaries. Therefore, it must be

recognized that what is meant by the ‘whole’ is determined only by the breadth of vision (Alexander 1968). In the case of architecture and design this notion of the systems boundary can also be explained as the context. This boundary, or context, is increasingly understood