UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO CEARÁ CAMPUS DE SOBRAL

SHIRLEY MOREIRA ALVES

LECTINA DE ABELMOSCHUSESCULENTUS REDUZ HIPERNOCICEPÇÃO

INFLAMATÓRIA NA ARTICULAÇÃO TEMPOROMANDIBULAR DE RATOS DEPENDENTE DE RECEPTORES OPIOIDES CENTRAIS

SHIRLEY MOREIRA ALVES

LECTINA DE ABELMOSCHUSESCULENTUS REDUZ HIPERNOCICEPÇÃO

INFLAMATÓRIA NA ARTICULAÇÃO TEMPOROMANDIBULAR DE RATOS DEPENDENTE DE RECEPTORES OPIOIDES CENTRAIS

Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação – Curso Ciências da Saúde, da Universidade Federal do Ceará – Campus Sobral, como requisito parcial para obtenção do Título de Mestre em Ciências da Saúde. Área de concentração: Farmacologia.

Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Hellíada Vasconcelos Chaves

Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação Universidade Federal do Ceará

Biblioteca Universitária

Gerada automaticamente pelo módulo Catalog, mediante os dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a)

M839l Moreira Alves, Shirley.

LECTINA DE ABELMOSCHUS ESCULENTUS REDUZ HIPERNOCICEPÇÃO

INFLAMATÓRIA NA ARTICULAÇÃO TEMPOROMANDIBULAR DE RATOS DEPENDENTE DE RECEPTORES OPIOIDES CENTRAIS / Shirley Moreira Alves. – 2017.

65 f. : il. color.

Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Federal do Ceará, Campus de Sobral, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde, Sobral, 2017.

Orientação: Profa. Dra. Hellíada Vasconcelos Chaves.

1. Abelmoschus esculentus. 2. Articulação temporomandibular. 3. TNF-alfa. 4. Hipernocicepção. 5. Lectina. I. Título.

SHIRLEY MOREIRA ALVES

LECTINA DE ABELMOSCHUSESCULENTUS REDUZ HIPERNOCICEPÇÃO

INFLAMATÓRIA NA ARTICULAÇÃO TEMPOROMANDIBULAR DE RATOS DEPENDENTE DE RECEPTORES OPIOIDES CENTRAIS

Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação – Curso Ciências da Saúde, da Universidade Federal do Ceará – Campus Sobral, como requisito parcial para obtenção do Título de Mestre em Ciências da Saúde. Área de concentração: Farmacologia.

Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Hellíada Vasconcelos Chaves

Aprovado em:13/12/2016.

BANCA EXAMINADORA

__________________________________________________ Profª. Drª. Hellíada Vasconcelos Chaves (Orientadora) Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC) –Campus Sobral

_____________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Vicente de Paulo Teixeira Pinto

Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC) –Campus Sobral

____________________________________________ Profª. Drª. Theodora Thaís Arruda Cavalcante

AGRADECIMENTOS

Ao Senhor Jesus, que é bom em todo o tempo. Tem coração manso e nos reserva sempre o melhor. Obrigada Senhor!!!

À minha mãe, Ana Lúcia Moreira, por ter escolhido a família muitas vezes em detrimento de si própria. Mãe, sem você jamais seria quem sou hoje. Obrigada por você existir, te amo!

Ao meu pai José Alves da Costa, por ter me dado vida e discernimento.

À minha “contraparte clara”: minha irmã Sheila Moreira Alves que nas mais diversas situações sempre esteve ao meu lado. Essa vitória também é sua.

Ao meu cunhado-irmão Ernando Rodrigues Batista, por se fazer porto seguro sempre que necessário. Você é presente do Senhor.

Ao meu esposo Antônio Dias Lima Filho, pela paciência e serenidade nos momentos mais turbulentos. Obrigada pelo apoio e carinho.

A todos os meus professores, desde os primeiros anos de ensino aos dias de hoje. Sem eles essa conquista não seria possível.

Ao Prof. Dr. Paulo Roberto Santos, pela extrema humildade e sabedoria. Exemplo a ser seguido.

A Todos que compõem o Laboratório de Farmacologia da UFC – Campus Sobral na pessoa da Profª Ms. Danielle Rocha do Val. Agradeço cada dia de dedicação, envolvimento e conhecimento empenhados. Aprendi muito com vocês.

À Profª. Drª. Mirna Marques Bezerra, por deixar transparecer amor em seu trabalho. Deus é seu escudo e nos presenteia com sua presença.

À Universidade Federal do Ceará (UFC); ao Laboratório de Farmacologia de Sobral (LAFS – UFC); ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Bioquímica; à Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES); ao Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq); à Fundação Cearense de Amparo à Pesquisa (FUNCAP), e ao Instituto de Biomedicina do Semi-Árido Brasileiro (INCT-IBISAB), pelo apoio e custeio do presente projeto.

RESUMO

e δ.Palavras-chave: Abelmoschus esculentus, articulação temporomandibular, TNF-alfa, hipernocicepção, lectina

Abstract:

Ethnopharmacological relevance: Abelmoschus esculentus is largely cultivated

in Northeastern Brazil for medicinal purposes, like in cases of pneumonia, bronchitis, pulmonary tuberculosis and inflammation. Aim of the study: To

evaluate the Abelmoschus esculentus (AEL) in reducing formalin-induced temporomandibular joint inflammatory hypernociception in rats. Materials and Methods: The behavioral experiments (CEUA nº 02\15) were performed on male

Wistar rats (180–240 g). Rats were pre-treated (i.v.) with AEL (0.001, 0.01 or 0.1 mg/kg) thirty minutes before 1.5% formalin injection in the TMJ. Further, to analyze the possible effect of opioid pathways on AEL efficacy, animals were pre-treated via intrathecal injection of naloxone or CTOP (the antagonist of Mu (µ) opioid receptor), naltrindole (antagonist of Delta (δ) opioid receptor) or Nor-Binaltorphimine (antagonist of Kappa () opioid receptor) 15 minutes before AEL followed by intra-TMJ injection of 1.5% formalin. Behavioral analysis were perfomed, animals were monitored for a 45 min observation period to quantify the nociceptive response. TMJ tissue, trigeminal ganglion and caudal subnucleus collection was performed for TNF-α dosage (ELISA). In addition, vascular permeability was evaluated by Evans Blue extravasation. Results: AEL

significantly reduced formalin-induced TMJ inflammatory hypernociception and decreased Evans blue extravasation. It also decreased TNF-α levels in TMJ tissue, trigeminal ganglion and caudal subnucleus. AEL antinociceptive effects, however, were not observed in the presence of naltrindole or Nor-Binaltorphimine.

Conclusions: These findings suggest that AEL efficacy depends on TNF-α

inhibition and the activation of δ and opioid receptors.

LISTA DE ILUSTRAÇÕES

Quadro 1 - Classificação das Disfunções Temporomandibulares……….. 19 Figura 1A - Anatomia do Complexo Trigeminal do Tronco Encefálico………… 17 Figura 1 - Eficácia da AEL na hipernocicepção inflamatória induzida por

formalina na ATM de ratos……… 37 Figura 2 - Efeito de AEL sobre a permeabilidade vascular na

hipernocicepção inflamatória induzida por formalina na ATM de ratos………... 37 Figura 3 - Efeito de AEL sobre os níveis de TNF-α na hipernocicepção

inflamatória induzida por formalina na ATM de

ratos…………..……… 38

Figura 4 - Efeito do antagonista não seletivo (naloxona) e seletivos (µ, eδ) na atividade antinociceptiva de AEL na hipernocicepção inflamatória induzida por formalina na ATM de

LISTA DE SIGLAS E ABREVIATURAS

AEL: Lectina de Abelmoschus esculentus ANOVA: Análise de Variância

ATM: Articulação Temporomandibular ATP: Adenosina Trifosfato

BioGeR: Laboratório de Genética Bioquímica e Radiobiologia b2-AR: Adrenoreceptor β2

CAPES: Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior CEUA: Comissão de Ética no Uso de Animais

COMT: catecol-O-metiltransferase CNPq: Conselho Nacional de Pesquisa CTOP: antagonista do receptor opióide µ

DAINES: Drogas anti-inflamatórias não-esteroidas DEAE – Sephacel: permutador iônico

DTM: Disfunção temporomandibular

DBCA: Diretriz Brasileira para o Cuidado e a Utilização de Animais Para Fins Científicos E Didáticos

δ: Receptor opioide delta

ELISA: Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay FITC: fluorescein isothiocyanate

FUNCAP: Fundação Cearense de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico

g: Grama

GRK: Cinase do receptor acoplado à Proteína-G H2SO4: Solução de ácido sulfúrico

HO-1: Hemeoxigenase-1 i.art.: Intra articular IL-1β: Interleucina-1beta

INCT- IBSAB: Instituto de Biomedicina do Semi -Árido Brasileiro i.t.: Intra tecal

i.v.: Intra venoso

LAFS: Laboratório de Farmacologia de Sobral mg: Miligrama

mg/kg: Miligrama por quilo µ: Receptor opioide mu µg: Micrograma

µl: Microlitro

n: Número de animais NaCl: Cloreto de Sódio nm: Namômetro

TNF-α: Fator de necrose tumoral alfa NT: Neuralgia do trigêmio

PGE2: Prostaglandina E2 pg/ml: picograma por mililitro

PZM21: Agonista seletivo do receptor opioide µ p<0,05: Probabilidade de erro estatístico 5% s: Segundos

SBCAL: Sociedade Brasileira de Ciência em Animais de Laboratório s.c: Subcutânea

TJM: Temporomandibular Joint º C: Grau Celsius

± EPM: Mais ou menos o erro padrão da média 5HTT: Recepor serotoninérgico

SUMÁRIO

1 INTRODUÇÃO……….………...……….……. 15

1.1 Dor Orofacial...……….………….……… 15

1.2 Processo inflamatório na região da articulação temporomandibular... 17

1.3 Disfunção temporomandibular……….………….……...…………. 18

1.4 Lectinas ……….………….………... 21

1.5 Propriedades biológicas de lectinas ………....………..….………..…. 23

2 JUSTIFICATIVA……….………….………...………….. 25

3 OBJETIVOS……….………….….………... 26

3.1 Objetivo Geral……….………….….………...… 26

3.2 Objetivos Específicos……….………...……… 26

4 CAPÍTULO 1: LECTIN FROM ABELMOSCHUS ESCULENTUS REDUCES RAT TEMPOROMANDIBULAR JOINT INFLAMMATORY HYPERNOCICEPTION DEPENDENT FROM CENTRAL OPIOID RECEPTORS…... 27

REFERÊNCIAS……….………….….………..… 51

APÊNDICE: Graphical Abstract Exigido pelo Periódico Journal of Ethnopharmacology………..…. 58

ANEXO A: Declaração de Aceite do Comitê de Ética……….... 59

1 INTRODUÇÃO 1.1 Dor orofacial

A dor exerce papel fisiológico importante nos organimos no sentido de alertar os sistemas biológicos para possíveis danos, o que torna a capacidade de sentir dor um importante mecanismo de sobrevivência (SBED, 2010), e de acorodo com a Associação Internacional para o Estudo da Dor (IASP, 2008) é compreendida como uma experiência sensorial e emocional desagradável, associada a um dano tecidual real ou potencial, ou ainda descrita nesses termos.

Os componentes da dor diferem da nocicepção, uma vez que a percepção da dor envolve diversos fatores como estímulo dos nociceptores primários, percepção emocional e cognitiva (componente subjetivo da dor) (Julius; Basbaum, 2001). Em contrapartida, a nocicepção (do latim nocere: nocivo; cap̂re: captar, receber) pode ser definida como a captação do nocivo, envolvendo apenas os mecanismos de transmissão desse estímulo ao sistema nervoso central (SNC) (Oliveira, 2001). Dessa forma, o termo dor deve ser aplicado aos estudos envolvendo humanos, por possuírem a capacidade de identificar seu caráter subjetivo, e nocicepção quando as pesquisas utilizarem animais, por estes serem desprovidos da capacidade de captar o estímulo emocional da dor.

A dor orofacial tem se revelado como um grande problema de saúde pública nas últimas décadas, comprometendo a funcionalidade articular e a qualidade de vida dos indivíduos atingidos (Okeson, 1998; Hargreaves, 2011; Monteiro et al., 2011). Adicionalmente, estudos tem demonstrado que os processos dolorosos representam um custo financeiro elevado por conta do grande número de horas disperdissadas durante o processo produtivo (Macfarlane, 2002). Ademais, apesar de acometer indivíduos jovens, pesquisas têm revelado que a dor orofacial possui alto grau de prevalência na população mundial como um todo (Hargreaves, 2011). Obermann (2010) afirma que pelo menos 10% da população adulta é acometida por dor orofacial, e que esse índice aumenta em idosos em mais de 50%, com tendência de as mulheres serem mais propensas às formas crônicas de dor orofacial, incluindo neuralgia do trigêmio e as disfunções temporomandibulares (DTM).

temporomandibulares (ATM) reconhecidas como articulações especializadas que realizam diversos tipos de movimentos a fim de cumprir suas funções fisiológicas. Além disso, fazem parte do sistema estomatognático a ATM, os músculos faciais, dentes, língua, glândulas, nervos, dentre outras estruturas (Okeson, 2008; Barretto et al., 2013) que juntas permitem o desempenho harmônico de funções

como a respiração, mastigação, deglutição e fala. Estas estruturas estão sujeitas a variações de pH (potencial de hidrogênio), temperatura, concentrações moleculares e estímulos mecânicos que podem levar a lesões e inflamação, provocando dor (Kitsoulis et al., 2011; Rando; Waldron, 2012; SBED, 2013).

Nesse contexto, a dor orofacial pode ser compreendida como qualquer dor associada aos tecidos não mineralizados/moles (pele, vasos sangúneos, gl̂ndulas ou ḿsculos) e mineralizados (ossos e dentes) da cavidade oral e face, estando normalmente relacionada aos eventos dolorosos que atingem a cabeça e/ou região do pescoço, ou ainda à cervicalgia, odinofagia, cefaleias primárias e doenças reumáticas tais como fibromialgia e artrite reumat́ide (Leeuw, 2010).

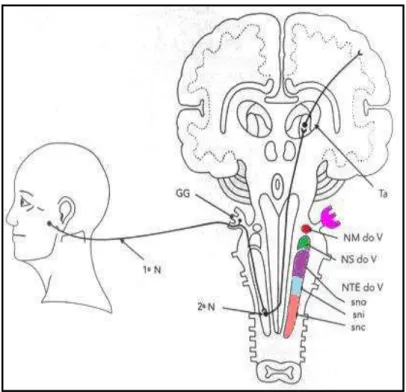

Porreca et al. (2002) e Verri-Junior et al. (2006) relatam em seus estudos que a dor, comum em diversas desordens clínicas, incluindo as que acometem a região orofacial, se apresenta como um dos sinais clássicos da inflamação, sendo iniciada pela sensibilização dos nociceptores aferentes primários. Assim, a capacidade de reconhecer os possíveis agentes lesivos habilita a liberação de mediadores da resposta inflamatória através do sistema imune (Robbins; Cotran, 2005). A percepção dolorosa da região orofacial está diretamente ligada ao estímulo polongado de nociceptores periféricos (Reyes; Uyanik, 2014) que, por sua vez, transmitem a informação nociva ao sistema nervoso central (SNC) e aos centros superiores do tronco encefálico, comunicando-se com o complexo trigeminal do tronco encefálico (tálamo e córtex somatosensorial) (Sessle, 2000). Este possui, em sua maioria, os corpos celulares dos neurônios sensoriais localizados no gânglio trigeminal, que mante´m de forma geral relação estreita com o sistema límbico, responsável pelo processamento subjetivo da dor (Matthews; Sessle, 2002).

do trato espinal do trigêmio, dividido em três subnúcleos: oral, interpolar e caudal. Sendo este ponto do tronco cerebral, também denominado como dorsal medular por possuir semelhanças com o corno dorsal espinhal, reconhecido como o principal sítio para a informação nociceptiva (Okeson, 2003; Takemura, 2006; Ren, Dubner, 2011).

Figura 1A- Anatomia do Complexo Trigeminal no Tronco Encefálico. Gânglio de Gasser (gânglio trigeminal) (GG); núcleo motor do complexo trigeminal (NM do V); núcleo sensitivo principal do complexo trigeminal (NS do V); núcleo do trato espinhal do complexo trigeminal (NTE do V), subdividido em: subnúcleo oral (sno), subnúcleo interpolar (sni), e subnúcleo caudal (snc). Ta: tálamo.

Fonte: Adaptado de OKESON, 2003.

1.2 Processo inflamatório na região da articulação temporomandibular

Durante a resposta inflamatória mediadores lipídicos (prostaglandinas), protéicos (citocinas), histamina, óxido nítrico, bradicinina e neuropeptídios são responsáveis pela manutenção e amplificação do processo inflamatório. Delineamentos de pesquisa envolvendo animais para a investigação do processo inflamatório articular apontam os neutrófilos como sendo os primeiros a migrarem para a artiulação afetada, além disso, a inflamação estimula a liberação de mediadores pró-inflamatórios denominados citocinas, como as interleucinas IL-1β,

IL-6 e IL-8 e o fator de necrose tumoral alfa (TNF-α) (Venkatesha et al., 2011), promovendo, dessa forma, a degradação da ATM (cartilagem articular, membrana sinovial e parte óssea). Tais superfícies danificadas podem acarretar em dor, inflamação e limitação da mobilidade local (Kostrzewa-Janicka et al., 2012).

Além disso, o TNF-α, produzido principalmente por macŕfagos, é apontado

em diversos estudos como uma importante citocina mediadora do processo inflamatório crônico e agudo observado durante o desenvolvimento de doenças articulares degenerativas (Kostrzewa-Janicka et al., 2012). Outro mediador inflamatório identificado em níveis elevados na sinóvia da ATM de pessoas que apresentam dor inflamatória é a serotonina (5-HTT), encontrada no SNC e em todos os tecidos periféricos (Oliveira-Fusaro et al., 2012). Contudo, mediadores químicos que compõem a inflamação podem ser estimulados por células gliais satélite que permeiam corpos neuronais, funcionando como um efetores da resposta inflamatória, o que evidencia que a inflamação não é somente resultado de mecanismos periféricos, mas também centrais (Ellis; Bennett, 2013).

1.3 Disfunção temporomandibular

2014). As DTM são classificadas em seis grandes grupos, e estes se ramificam em outras disfunções, que podem ser observadas no Quadro 1.

Quadro 1: Classificação das Dinfunções Temporomandibulares

Disfunções Temporomandibulares * Disfunções Articulares

* Dor articular - Artralgia - Artrite

* Disfunçoes articulares - do complexo côndilo-disco - de hipomo-bilidade e hipermobilidade

* Doenças articulares

- Condilose - Osteocondrose dissecante - Osteonecrose

- Condromatose sinovial - Articulares

degenerativas - Osteoartrite - Osteoartrose * Disfunções congênitas ou

de desenvolvimento - artrite sistêmica - neoplasia * Fraturas

Fonte: Adaptado de Leeuw; Klasser (2013).

Em um estudo realizado com 578 adolescentes chineses, a fim de investigar a prevalência de sintomas de DTM e sua relação com a qualidade do sono e distúrbios psíquicos, indicou que 61,4% da população estudada apresentou pelo menos um sintoma de DTM, e que 1/3 dos indivíduos experimentaram alteração do sono (não-reparador), depressão e estresse, e ainda que 65,2% sofriam de ansiedade, dando robustez aos estudos que afirmam a íntima relação entre distúrbios do sono e sofrimento de ordem psíquica com as DTM (Lei et al., 2016). Sabe-se que condições dolorosas relacionadas à região orofacial (principalmente a dor crônica) refletem negativamente na qualidade de vida dos indivíduos afetados, gerando consequências graves como incapacidade funcional e para o trabalho, prejuízos de ordem social, econômica e afetiva (SBED, 2012; Greene, 2010).

persistiram em 61% dos brancos contra 35% dos afro-americanos. Essas variações podem estar relacionadas ao viés de incidência-prevalência, viés de seleção que pode ocorrer em desenhos de pesquisas transversais (Slade et al., 2016). Apesar das divergências encontradas na literatura acerca da prevalência de DTM, com variações que giram em torno de 5-6% a 12% (De Rossi et al., 2014), a dor associada à DTM foi relatada em 9-13% da população em geral (com relação homem:mulher de 2:1), entretanto apenas 4-7% buscam tratamento (4 vezes mais mulheres). Já investigações realizadas por Steven; Kraus (2014) com um grupo de 511 pessoas (8 hispânicos, 63 afro-americanos, 401 brancos e 39 de outras etnias) que apresentavam quadro de DTM, com média de idade de 43,9 anos (44,9 entre as mulheres e 43,7 entre os homens), a proporção homem:mulher foi de 5:1. Ademais, os sinais e sintomas atingem seu pico entre 20-40 anos de idade (Manfredini et al., 2011).

A DTM, portanto, é uma doença complexa que resulta da interação de causas de domínios genéticos e ambientais (estresse, má qualidade no sono, tabagismo, hábitos parafuncionais, doenças sistêmicas e etc.) (Slade et al., 2016). No âmbito genético, pesquisas clínicas realizadas com genes da COMT (catecol-O-metiltransferase), b2-AR (adrenoreceptor β2) e 5HTT (receptor serotoninérgico) indicam que polimorfismos são relacionados com o processamento da dor e risco de desenvolvimento de DTM (Maixner et al., 2011). Adicionalmente, estudos realizados por Slade et al., 2015 e Slade et. al., 2016 demonstraram que a COMT,

participante da regulação do catabolismo de neurotransmissores de catecol, possui papel importante na modificação da resposta ao estresse psicológico sobre a dor, sendo aumentado em pessoas com DTM.

envolvidas na patogenia aguda e crônica de dor orofacial (Chiang et al., 2011; Chiang et al., 2012).

O caráter multifatorial da DTM dificulta não só o diagnóstico como também o seu tratamento. Neste sentido, intervenções terapêuticas farmacológicas, com drogas anti-inflamatórias não-esteroidas (DAINES) tem sido a abordagem, muitas vezes, de primeira escolha, para o alívio das dores e demais sintomas associados. Contudo, o tratamento deve priorizar intervenções conservadoras diante de quadros não-cirúrgicos e que não apresentem degeneração das partes moles e nem óssea da ATM (Cairns, 2010). Outras modalidades terapêuticas incluem placas oclusais, fisioterapia, exercícios madibulares, acupuntura, laserterapia, toxina botulínica, dentre outros (Okeson, 2008; Fernandes et al., 2009).

Nesse contexto, tem-se revelado promissora a pesquisa com recursos naturais (como lectinas e polissacarídeos) na descoberta de ferramentas farmacológicas que possam ser utilizadas para testes de novas substâncias a fim de reduzir os efeitos pró-inflamatórios das DTM (do Val et al., 2014; Rivanor et al.,

2014; Rodrigues et al., 2014; Freitas et al., 2016).

1.4 Lectinas

A capacidade de se combinar específica e reversivelmente com várias substâncias é uma característica da maioria das proteínas. Enzimas que se ligam a seus substratos e inibidores ou anticorpos que se ligam ao antígeno, são exemplos bem conhecidos (Sharon; Lis, 1989). Lectinas, entretanto, são proteínas definidas inicialmente como moléculas que se ligam reversivelmente a carboidratos, aglutinam células e/ou precipitam polissacarídeos e glicoproteínas. A primeira definição de lectinas foi proposta por Boyd; Shapleigh (1954) que

utilizaram o termo “lectina”, oriundo da palavra latina legere, que significa

Goldstein et al. (1980) propuseram uma nova definição de lectinas, na qual

estas eram descritas como “proténas de origem não imune, que se ligam a

carboidratos ou glicoproteínas, aglutinam células e/ou precipitam

glicoconjugados” definição modificada posteriormente por Kocourek; Horejsi

(1981), que sugeriram que lectinas “são proténas ou glicoproténas de natureza

não imune que se ligam a carboidratos, sem apresentar atividade enzimática frente a esses açúcares e não requerem grupos hidroxilas livres para sua

ligação”.

Atualmente, a definição mais aceita para lectinas é a proposta por Peumans; Van Damme (1995), que definem lectinas como proteínas de origem não imune contendo pelo menos um domínio não-catalítico capaz de ligar-se reversivelmente a mono ou oligossacarídeos específicos. Fundamentados no conhecimento da estrutura das lectinas, Peumans; Van Damme (1995) classificaram as lectinas em três grupos: merolectinas, hololectinas e quimerolectinas. As merolectinas possuem um único sítio de ligação a carboidratos sendo desprovidas de atividade hemaglutinante. As hololectinas são semelhantes as merolectinas, entretanto, possuem dois ou mais sítios de ligação a carboidratos podendo, desta forma aglutinar células ou precipitar glicoconjugados. As quimerolectinas se diferenciam das duas outras classes por possuírem além do sítio de ligação a carboidratos, um outro domínio não relacionado que apresenta atividade biológica distinta e independente, podendo ou não apresentar atividade hemaglutinante, dependendo do número de sítios de ligação a açúcares.

As sequências de aminoácidos de uma grande quantidade de lectinas já foram estabelecidas, e em geral as estruturas terciárias e quaternárias encontradas são extremamente variáveis (Sharon; Lis, 2007), e podem ser inativadas ou desnaturadas por processos como aumento de temperatura, pH alterado (em relação ao seu pH ótimo) e tratamento com enzimas proteolíticas tais como papaína ou tripsina (Gorakshakar; Ghosh, 2016).

ron, diferenciação celular (Pneumans; Van Damme, 1995; Beuth et al., 1995; Sharon; Lis, 2004).

As Lectinas são empregadas em estudos diversos, sobretudo nos em que há a necessidade de detectar, identificar e avaliar a funcionalidade de carboidratos. Além disso, as lectinas podem ser utilizadas como ferramentas para detecção antigenos nas células com base na sua estrutura superficial, e suas interações com células e substâncias solúveis podem ser revertidas por açúcares simples, sendo essa interação comumente utilizada como indicativo da existência de hidratos de carbono (Sharon; Lis, 2007; Gorakshakar; Ghosh, 2016).

1.5 Propriedades biológicas de lectinas

Nas últimas décadas, pesquisadores têm voltado sua atenção à utilização de moléculas de origem vegetal - proteínas e metabólitos secundários - na perspectiva de avaliar a eficácia e segurança como agentes farmacológicos (Cairns, 2010). A utilização de lectinas e polissacarídeos isolados de algas marinhas no tratamento das condições inflamatórias das DTM já foi demonstrada em estudos pré-clínicos (do Val et al.,Rivanor et al., 2014; Rodrigues et. al., 2014). Ademais, atividade inflamatória, anti-inflamatória, anti-hipernociceptiva (Alencar et al., 2007; Assreuy et al., 2009; Rangel et al., 2011; Figueiredo et al., 2009), e ausência de citoxicidade aguda e crônica na utilização de lectinas (Sabitha et al., 2011; Kumar et al., 2009) foram constatadas.

carragenina, também foi observada atividade anti-inflamatória de lectinas (Soares et al., 2012).

2 JUSTIFICATIVA

É inegável que inúmeras conquistas ocorreram no âmbito da saúde bucal, porém um número muito grande de pessoas sofrem com dor orofacial, e as DTM estão entre as condições de maior queixa clínica (SBED, 2012). Uma abordagem terapêutica eficaz pode fazer diferença no tratamento de sintomas como dor crônica e incapacitante, contudo, o caráter multifatorial que envolve as DTM dificulta essa escolha.

Portanto, esse cenário de alta prevalência, incidência e dificuldades na identificação e tratamento que envolvem as DTM têm encorajado a comunidade científica para o estudo de novas alternativas terapêuticas para o alívio de tais condições através da utilização de recursos naturais como a AEL, dentre outras (do Val et al., 2014; Rivanor et al., 2014; Rodrigues et al., 2014; Freitas et al.,

3 OBJETIVOS

3.1 Objetivo Geral

Avaliar o uso da AEL como alternativa terapêutica para DTM verificando sua ação antinociceptiva, anti-inflamatória e sobre receptores opioides em modelo animal.

3.2 Objetivos Específicos

- Investigar o efeito antinociceptivo e anti-inflamatório promovido pela lectina de Abelmoschus esculentus no modelo de hipernocicepção induzida por formalina na ATM de ratos;

- Estudar o papel dos receptores opioides em seu mecanismos de ação no modelo hipernocicepção inflamatória induzida pela formalina na ATM de ratos;

4 CAPÍTULO 1: LECTIN FROM ABELMOSCHUS ESCULENTUS REDUCES RAT TEMPOROMANDIBULAR JOINT INFLAMMATORY HYPERNOCICEPTION DEPENDENT FROM CENTRAL OPIOID RECEPTORS

Shirley Moreira Alves1, Raul Sousa Freitas2, Danielle Rocha do Val3, Lorena

Vasconcelos Vieira4, Ellen Lima de Assis4, Carlos Alberto de Almeida Gadelha5,

Tatiane Santi Gadelha5, José Thalles Jocelino Gomes de Lacerda5, Juliana

Trindade Clemente-Napimoga6, Vicente de Paulo Teixeira Pinto7, Mirna Marques

Bezerra1,7 and Hellíada Vasconcelos Chaves1,7.

1Master of Healthy Sciences Degree Program, Federal University of Ceará,

Avenida Comandante Maurocélio Rocha Pontes, 100 Derby - CEP: 62.042-280 Sobral, Ceará, Brazil. shirley_sma31@yahoo.com.br

2Department of Morphology Federal University of Ceará - UFC, Rua Delmiro de

Farias, s/n - Rodolfo Teófilo, CEP: 60.430-170, Fortaleza, Ceará, Brazil. raul.sf2@gmail.com

3Northeast Biotechnology Network (Renorbio), Federal University of Pernambuco -

UFPE, Avenida Prof. Moraes Rego, 1235 Cidade Universitária CEP: 50670-901, Recife, Pernambuco, Brazil. danielleval@hotmail.com

4Faculty of Dentistry, Federal University of Ceará - UFC, Avenida Comandante

Maurocélio Rocha Pontes, 100 Derby - CEP: 62.042-280 Sobral, Ceará, Brazil. lohrenavieira@hotmail.com; ellenjbe@hotmail.com

5Department of Molecular Biology, Federal University of Paraíba - UFPB, Cidade

Universitária, CEP: 58059-900 João Pessoa, Paraíba, Brazil. calbgadelha@gmail.com; santi.tatiane@gmail.com; thalles_lacerda2@hotmail.com

6Faculty of Dentistry, University of Campinas - UNICAMP, Avenida Limeira, 901,

Vila Rezende,CEP 13414-903, Piracicaba, São Paulo, Brazil. juliana.napimoga@slmandic.edu.br

7Faculty of Medicine, Federal University of Ceará - UFC, Avenida Comandante

Maurocélio Rocha Pontes, 100 -Derby - CEP: 62.042-280 Sobral, Ceará, Brazil. pintovicente@gmail.com; mirnabrayner@gmail.com;

*Corresponding author: Profa. Dra. Hellíada V. Chaves

Faculty of Dentistry of Sobral - Federal University of Ceará Avenida Comandante Maurocélio Rocha Pontes, 100 Derby - CEP: 62.042-280

Phone: 55 88-3611-2202 - Fax: 55 88-3611- 8000 Sobral - Ceará - Brazil

E-mail: helliadachaves@yahoo.com.br

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Abstract:

Ethnopharmacological relevance: Abelmoschus esculentus is largely cultivated

in Northeastern Brazil for medicinal purposes, like in cases of pneumonia, bronchitis, pulmonary tuberculosis and inflammation. Aim of the study: To

evaluate the Abelmoschus esculentus (AEL) in reducing formalin-induced temporomandibular joint inflammatory hypernociception in rats. Materials and

Methods: The behavioral experiments (CEUA nº 02\15) were performed on male

Wistar rats (180–240 g). Rats were pre-treated (i.v.) with AEL (0.001, 0.01 or 0.1 mg/kg) thirty minutes before 1.5% formalin injection in the TMJ. Further, to analyze the possible effect of opioid pathways on AEL efficacy, animals were pre-treated via intrathecal injection of naloxone or CTOP (the antagonist of Mu (µ) opioid receptor), naltrindole (antagonist of Delta (δ) opioid receptor) or Nor-Binaltorphimine (antagonist of Kappa () opioid receptor) 15 minutes before AEL followed by intra-TMJ injection of 1.5% formalin. Behavioral analysis were perfomed, animals were monitored for a 45 min observation period to quantify the nociceptive response. TMJ tissue, trigeminal ganglion and caudal subnucleus collection was performed for TNF-α dosage (ELISA). In addition, vascular permeability was evaluated by Evans Blue extravasation. Results: AEL

however, were not observed in the presence of naltrindole or Nor-Binaltorphimine.

Conclusions: These findings suggest that AEL efficacy depends on TNF-α

inhibition and the activation of δ and opioid receptors.

Keywords: Abelmoschus esculentus; temporomandibular joint, TNFα, hypernociception, lectin

1. Introduction

Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) arthritis presents as one of the differential diagnoses in temporomandibular disorders (TMD), which, in turn, encompasses a group of musculoskeletal and neuromuscular conditions involving the TMJ, masticatory muscles and all associated tissues. TMDs are often associated to acute or persistent pain, and the patients may suffer from other painful disorders. Chronic forms of TMD may lead to withdrawal or disability at work or to social activities, resulting to a impairment in the quality of life (Greene, 2010).

A study evaluating the prevalence of TMD symptoms and its relation to sleep quality and psychic disorders, has shown that 61.4% of the studied population showed less than one TMD symptom, and that 1/3 of the subjects experienced altered sleep, depression and stress, and 65.2% had anxiety (Lei et al., 2016). Socio-demographic predictors indicate a 3.9% incidence of TMD per year with moderate or disabling pain (Slade et al., 2013). Despite the divergences found in the literature about the prevalence of TMD (variations between 5%-6% and 12%) (De Rossi et al., 2014), the pain related to TMD was reported in 9-13% of the general population on proportion man: woman of 2:1). In addition, signs and symptoms peaked around 20-40 years old (Manfredini et al., 2011).

In the recent decades, researchers have been growing interest in alternative therapies and use of natural products to assessing their efficiency and safety (Cairns, 2010; Rivanor et al., 2014; Freitas et al., 2016) in order to develop potential tools for new therapies to ameliorate inflammatory pain, which have encouraged scientific studies to search for new substances with therapeutic action and to confirm the efficacy of medicines derived from plants.

Due to the high prevalence, incidence and difficulties in identifying and treating the inflammatory conditions related to TMD, our group has demonstrated, through preclinical studies, the use of natural products in the treatment of inflammatory conditions of TMDs, especially those derived from plants such as

Abelmoschus esculentus lectin (AEL) (Freitas et al., 2016) and Tephrosia toxicaria

(Do Val et al., 2014), as well as lectins and polysaccharides derivated from marine algae (Rivanor et al., 2014; Rodrigues et al., 2014) Abelmoschus esculentus

(Malvaceae) (popularly called okra) is originated from Africa and has spread across a number of tropic countries, including northeastern Brazil. This species is considered of high nutritional value (rich source of calcium and vitamins A, C and B1), easy cultivation (tropical regions, temperatures between 18 and 35 °C), and its commercialization has been used for medicinal purposes (treatment of pneumonia, bronchitis, pulmonary tuberculosis, still acting as a laxative, and inflammation) (Castro et al., 2008; Panero et al., 2009).

investigated the role of opiod receptors and the putative involviment of TNF-α in AEL efficacy.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS 2.1. Animals

Male Wistar rats (160–220 g) (n=6) were housed in standard plastic cages with food and water available ad libitum. They were maintained in a temperature controlled room (23 ± 2 °C) with a 12/12- hour light-dark cycle. All experiments were designed to minimise animal suffering and to use the minimum number of animals required to achieve a valid statistical evaluation. The animal supplier for this study was the Central Animal House of the Federal University of Ceará and the experimental protocol was conducted in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Ceará, Fortaleza, Brazil (CEUA nº 02\15).

2.2. Source Material

A. esculentus seeds were collected in the municipality of Conde, Paraíba,

Brazil (geographical coordinates: S-7°17'629 "W-34°48'085") for botanical identification. Professor Rita Balthazar de Lima (Department of Botany, Federal University of Paraiba - UFPB, Brazil) identified species of the Malvaceae family to which A. esculentus species belong. The specimen was deposited in the UFPB

herbarium under the identification number of 41,386. Lectin purification was performed in BioGeR (Laboratory of Biochemical Genetics and Radiobiology).

2.3. Extraction of Lectin

Seeds were grounded to powder and its lipids removed with n-hexane. To obtain the protein extract, the powder was placed in added in Tris-HCl buffer pH 7.4 with 0.1 M NaCl 0.15 M for 3 h and then centrifuged at 5.000 rpm at 4 °C for 20 min. The resulting precipitate was discarded, and the supernatant was subjected to ammonium sulfate precipitation, obtaining a lectin fractionwithin the range of 30–60% saturation. The lectin fraction was dialyzed exhaustively against water, lyophilized, and then isolated by ion exchange chromatography on DEAE –

7.4. Lectin elution was prepared using the gradient of bibasic sodium phosphate 0.025 M and NaCl pH 7.4 1 M. Elution wasmonitored by spectrophotometer at a wave length of 280 nm, being it dialyzed against water, frozen and lyophilized. Furthermore, this lectin under study is endotoxin free which ultimately mean it does not exert toxic effects on animals under investigation.

2.4. Efficacy of lectin from Abelmoschus esculentus on formalin-induced temporomandibular joint inflammatory hypernociception in rats

2.4.1.TMJ injection

The animals were briefly anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane and the posteroinferior border of the zygomatic arch was palpated. Rats received an intra-articular injection of 1.5% formalin (Roveroni et al., 2001). The needle was inserted immediately inferior to this point and was advanced in an anterior direction until reaching the posterolateral aspect of the condyle. TMJ injections were performed via a 30-gauge needle introduced to the left TMJ at the moment of the injection. A cannula consisting of a polyethylene tube was connected to the needle and also to a 50 μL syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV). Volume per injection was 50 μL. Each animal regained consciousness approximately 30s after discontinuing the anesthetic and was returned to the test chamber.

2.4.2. Experimental design

Thirty minutes before formalin injection rats were pre-treated (0.1 mL/100g body weight) with AEL 0.001, 0.01 or 0.1 mg/kg) by intravenous (i.v.) injection or 0.9% sterile (sham group) fallowed by intra-TMJ injection of 1.5% formalin in a final volume of 50 µl as above described. Immediately after the behavioral analyzes, the animals were anesthetized and euthanized by decapitation, and the periarticular tissues, trigeminal ganglion and caudal subnucleus were removed and processed for biochemical analysis.

2.4.3. Behavioral tests for evaluation of nociceptive responses

was sacrificed at the end of the experiment. Testing sessions took place during the light phase (between 9:00 AM and 5:00 PM) in a quiet room maintained at 25 °C and all animals were manipulated for 7 days before the experiment to be habituated to the experimental manipulation. (Tjolsein, 1992). Each animal immediately recovered from anesthesia after TMJ injection and was returned to the test chamber for counting nociceptive responses during the following 45 min observation period. The nociceptive response score was defined as the cumulative total number of seconds that the animal spent rubbing the orofacial region asymmetrically with the ipsilateral fore or hind paw plus the number of head flinches counted during the observation period as described previously (Roveroni et al., 2001). Results are expressed as the duration time of nociceptive behavior. Rats did not have access to food or water during the test.

2.4.4. Collection of biological materials 2.4.4.1. TMJ tissue

The superficial tissues were dissected until reaching the left TMJ then the TMJ soft tissues were collected. The samples were stored in a freezer -80º C.

2.4.4.2. Trigeminal ganglion

In order to access to the trigeminal ganglion, which is lodged at the base of the skull in the trigeminal cavus region in the temporal bone, the skullcap and the brain were removed, and the trigeminal ganglion was carefully identified and collected. The samples were stored in a freezer -80 ºC.

2.4.4.3. Caudal subnucleus of the spinal tract of the trigeminal nerve

In order to have access to the caudal subnucleus, which is located in the brainstem, the brain was removed, which was positioned in a specific matrix for the neural structures of rats. The removal of the caudal subnucleus was performed by cutting with a scalpel blade positioned 2 mm in the caudal direction to obex.

In another sequence of experiments, AEL (0.01 mg/kg) was administered to rats 30 min prior to formalin. Immediately after formalin injection (1.5% i.art) Evans Blue dye 1% (5mg/kg, i.v.) was administered administered systemically to assess plasma extravasation (Torres-Chavéz et al., 2012). After 45 minutes, the animals were euthanized and the ATMs removed for analysis. Immediately after the extraction, the periarticular tissue was weighed and placed in 1mL of formamide overnight at 60 ºC (Fiorentino et al., 1999). The supernatant (100 μL) was extracted, and the absorbance at 620 nm was determined in spectrophotometer. The concentration was determined by comparison to a standard curve of known amounts of Evans blue dye in the extraction solution, which was assessed within the same assay. The amount of Evans blue dye (μg) was then calculated per mg of exudates.

2.5.2. TMJ periarticular tissue, trigeminal ganglion and caudal subnucleus TNF-α assay

TNF-α concentrations were determined in the TMJ periarticular tissue, trigeminal ganglion and caudal subnucleus 45 min after formalin injection in rats that received 0.01mg/kg AEL or vehicle (0.9% sterile saline). TMJ periarticular tissue, trigeminal ganglion and caudal subnucleus were removed and stored at

−80 °C. The material was homogenized in a solution of RIPA Lysis Buffer System

later and the plate was incubated in the dark at room temperature for 15–20 min. The enzyme reaction was stopped with H2SO4 and absorbance was measured at 450 nm. TNF-α concentrations were expressed as pg/ml.

2.6. Evaluation of the involvement of the opioid pathway in the antinociceptive AEL effect on formalin-induced temporomandibular joint inflammatory hypernociception

2.6.1. Intrathecal drug administration

Rats were briefly anesthetized by the inhalation of isoflurane, and a small area of the skin that covers a cervical region was trichotomized with an electric appliance. The animals were positioned in the ventral decubitus position, in order to the suboccipital space was easily found. A 30 gauge needle, connected to a 50

μL Hamilton syringe, by a polyethylene cannula, was used for the injection. First the needle was inserted just below the occipital bone penetrating the skin over the suboccipital space up to 4 mm deep and then to slightly inclined towards the cranial. The needle was advanced plus 2 mm to puncture the atlanto-occipital membrane and reach the bulbar subarachidoid space. This technique allows direct administration of the drug in the cerebrospinal fluid in the proximity to the trigeminal caudal subnucleus. The total volume of intrathecal injections was 10 μL and administered in a rate of 1 μL/s, as previously standardized (Fischer et al., 2009). Immediately after behavioral analysis, the animals were anesthetized and euthanized by decapitation. The administered drugs were diluted in sterile saline solution (0.9%).

2.6.2. Effect of the nonselective opioid receptor antagonist naloxone on AEL-induced antinociception

2.6.3. Effect of µ, δ and -opioid receptors on AEL-induced antinociception Rats were divided in groups of five animals, and each group was pretreated (15 min) with an intrathecal injection of a specific inhibitor of µ-opioid receptor CTOP (10 µg/10 µl /intrathecal) the inhibitor of δ -opioid receptor Naltrindole (10 or 30 µg/10 µl/intrathecal) or the selective -opioid receptor antagonist Nor-BNI (15 or 45 µg/10 µl/intrathecal); followed by AEL (0.01 mg/kg /i.v.) 30 min prior 1.5% formalin intra-TMJ injection (50 µl /TMJ). Behavioral nociception response was evaluated for 45 min period observation. All animals received a final volume of 50 µl of solutions into TMJ (Picolo; Cury, 2004; Clemente et al., 2004).

2.7. Statistical analysis

The data are presented in figures and text as the means±SEM. The number (n) of animals per experimental group was at least 5. Differences between means were compared using a one-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni test. A probability level of less than 0.05 (P<0.05) was considered to indicate statistical

significance.

3. Results

3.1. AEL reduces formalin-induced temporomandibular joint inflammatory hypernociception in rats

Saline _ Mor 0.001 0.01 0.1 0 100 200 300

*

# # #Formalin 1.5% (50L/art.) AEL (mg/kg) #

*

*

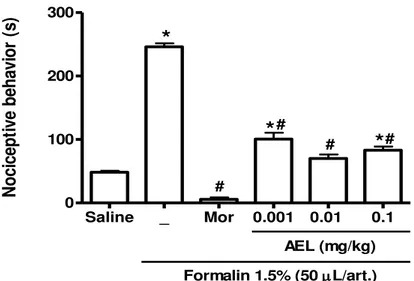

N oc ic ep tiv e be ha vi or (s )Fig.1 Effects of AEL on formalin-induced temporomandibular joint inflammatory hypernociception in rats Pretreatment with AEL (0.001, 0.01 and 0.1 mg/kg; i.v.) and morphine (5 mg/kg; s.c.) reduced the the behavioral nociceptive response induced by the injection of formalin 1.5% (i.art.; 50μl). Saline (48.40 ± 2.24), formalin (246.0 ± 5.73), morphine (5.6 ± 3.09), AEL 0.001 mg/kg (100.5 ± 10.22), AEL 0.01 mg/Kg (70.13 ± 6.18) and AEL 0.1 mg/kg (83 ± 5.95). *p <0.05 compared to saline group; #p <0.05 compared to the formalin 1.5% group (ANOVA, Bonferroni).

3.2. AEL reduces Evans blue extravasation measurement on formalin-induced TMJ inflammatory hypernociception in rats

The formalin 1.5% injection (i.art.) resulted in a significant increase in Evans blue dye extravasation measurement in comparison with the saline group. Pretreatment with AEL (0.01 mg/kg, i.v.) decreased (p<0.05) Evans Blue dye extravasation compared with the formalin group (Fig. 2).

Saline _ AEL (0.01 mg/kg)

0 10 20 30 40 50

Formalin 1.5% (50L/art.)

* # E va n s b lu e (µ g /m g )

group. Saline (18.88 ± 4, 29), formalin (42.33 ± 5.13) and AEL 0.01 mg/kg (12.01 ± 1.14). *p <0.05 compared to saline group; #p <0.05 compared to the formalin group 1.5% (ANOVA, Bonferroni).

3.3. AEL decreases TNF-α levels in TMJ tissue, trigeminal ganglion and caudal subnucleus on formalin-induced TMJ inflammatory hypernociception in rats

The formalin 1.5% injection (i.art.) resulted in a significant increase in TNF-α levels in TMJ tissue, trigeminal ganglion and caudal subnucleus compared with saline group. AEL 0.01 mg/kg (i.v.) also reduced TNF-α in TMJ tissue, trigeminal ganglion and caudal subnucleus in comparison with formalin group.

Fig. 3 Effects of AEL on TNF-α levels in the TMJ periarticular tissue (A), trigeminal ganglion (B) and caudal subnucleus (C) on formalin-induced TMJ inflammatory hypernociception Pretreatment with AEL (0.01 mg/kg, i.v.)

Saline _ AEL 0.01 mg/kg

0 50 100 150 200 250 300

Formalin 1.5% (50L/art.) * # A T N F - ( p g /m L T M J ti ss u e)

Saline _ AEL 0.01 mg/kg

0 50 100 150 * # B

Formalin 1.5% (50L/art.)

T N F - ( p g /m L t ri g em in al g an g li o n )

Saline _ AEL 0.01 mg/kg

0 50 100 150 200 250 * # C

Formalin 1.5% (50L/art.)

reduced levels of TNF-α in the TMJ tissue (Figure A), saline (61.29 ± 7.19), formalin (227.5 ± 15.5), and AEL 0.01 mg/Kg (131.8 ± 7.70); In the trigeminal ganglion (Figure B), saline (81 ± 4,16), formalin (113.8 ± 2.62), and AEL 0.01 mg/kg (84. 67 ± 0.88), and in the caudal subnucleus (Figure C), saline (97 ± 21.01), formalin (188.5 ± 27.18) and AEL 0.01 mg/kg (109.4 ± 10.51). * P <0.05 compared to saline group; #p <0.05 compared to the formalin group 1.5% (ANOVA, Bonferroni).

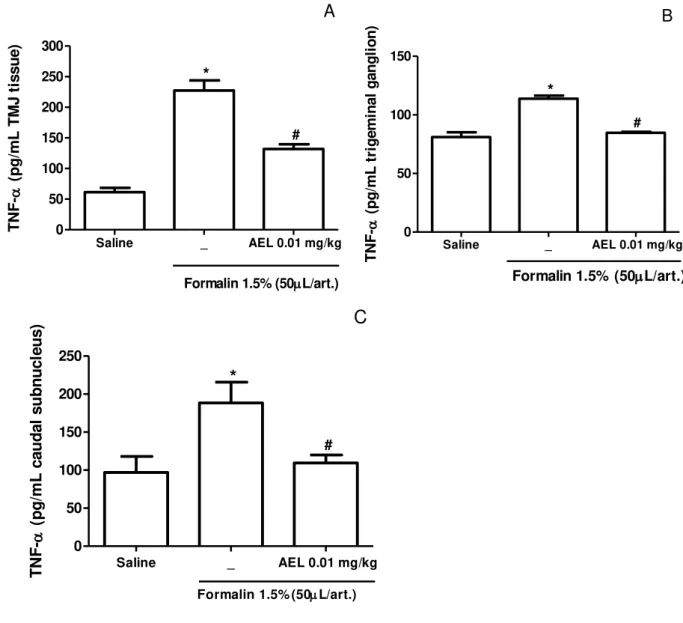

3.4 AEL inhibits formalin-induced temporomandibular joint inflammatory hypernociception through central opioids receptor activation

In order to investigate whether the antinociceptive effect of AEL depends on the central opioid activation, was tested the effect of the pretreatment with naloxone, a non selective opioid receptor antagonist or the selective µ-opioid receptor CTOP, δ-opioid receptor Naltrindole or the selective -opioid receptor antagonist Nor-BNI 15 min before AEL treatment. The intrathecal administration of naloxone (15 μl/10μl) significantly reversed (p <0.05) the antinociceptive effect of AEL (0.01 mg/kg). This result suggests that the antinociceptive effect of AEL depends on the central opioid receptors activation (Fig. 4A).

The Intrathecal administration of naltridole, a selective opioid receptor antagonist delta (δ) (10 or 30 ug/10 uL), significantly reversed (p<0.05) the antinociceptive effect of AEL (0.01 mg/kg). This result suggests that the antinociceptive effect of AEL depends on the activation of the δ opioid receptor (Figure 4B). The intrathecal administration of nor-binaltorfimine, a selective opioid

receptor antagonist kappa (ĸ) (15 or 45ug/10uL) 15 minutes prior AEL treatment

significantly abolishes (p<0.05) the antinociceptive effect of AEL 0.01 mg/Kg. This fiding may suggests that the antinociceptive effect of AEL also depends on the activation of the opioid receptor ĸ (Figure 4C). The intrathecal administration of

Fig.4 Effect of the non selective (naloxone) and selective (μ, ĸ and δ) opioid receptor antagonists on the AEL antinociceptive efficacy on formalin-induced TMJ inflammatory hypernociception Naloxone (15ug/10uL/intrathecal) reversed the antinociceptive effect of AEL (0.01 mg/kg) (Figure A); Saline (48.4 ± 2.24), formalin (211.7 ± 7.82), morphine + naloxone (147.2 ± 4.60), AEL (0.01 mg/kg) (92.8 ± 15.66) and AEL (0.01 mg/kg) + naloxone (160 ± 8.51). Naltrindole (10 or 30ug/10uL) the delta (δ) opioid receptor antagonist reversed the antinociceptive effect of AEL (0.01 mg/kg) (Figure B); Saline (48.4 ± 2.24), formalin (211.7 ± 7.82), AEL (0.01 mg/kg) (82 ± 14.63), naltrindole 10 ug/10 uL + AEL (0.01 mg/Kg) (109.2 ± 5.59), naltrindole 30 ug/10 uL + AEL (0.01 mg/kg) (139.8 ± 7.34) and naltrindole 30 μg/10μl (203.8 ± 5,92). Nor-binaltorfimine (15 or 45μg/10μl) the opioid receptor antagonist kappa (ĸ) reversed the antinociceptive effect of AEL (0.01 mg/kg) (Figure C); Saline (47.57 ± 1.73), formalin (211.2 ± 8.36), AEL (0.01 mg/kg) (88.4 ± 8.88), nor-binaltorfimine 15μg/10μl + 1 mg/kg) (159.9 ± 12.34), nor-binaltorfimine 45μg/10μl + AEL (0.01 mg/kg) (174.5 ± 7.98) and nor-binaltorfimine (45μg/10μl) (235.2 ± 21.31). CTOP 10 (μg/10μl) the Opioid receptor antagonist mu (μ) did not reverse the antinociceptive effect of AEL (0.01 mg/kg) (Figure D); Saline (48.40 ± 2.24), formalin (165 ± 25.09), AEL (0.01 mg/kg) (71.4 ± 9.75), CTOP 10 μg/10μl + AEL (0.01 mg/Kg) (51.5 ± 14.82), CTOP 10μg/10μl (203.8 ± 5.92). * P <0.05 compared to saline group; #P <0.05 compared

Salina Nal Nal

0 100 200 300

Formalin 1.5% (50L/art.)

* # + AEL (0,01mg/kg) Morphine # & A N oc ic ep tiv e be ha vi or ( s)

Saline 10 30 30

0 100 200 300

AEL (0,01 mg/kg)

Naltrindole (µg/10 µL)

Formalin 1.5% (50L/art.)

* # + B + N o ci ce p ti ve b eh av io r (s )

Salina 15 45 45

0 100 200 300

AEL (0,01 mg/kg)

Binaltorphirmine (µg/10 µL)

Formalin 1.5% (50L/art.) * # + + C N o c ic e p ti v e b e h a v io r (s )

Saline 10 10

0 100 200 300

AEL (0,01 mg/kg) CTOP (µg/10 µL)

to the formalin group 1.5%; P<0.05 compared to the morphine group and +P<0.05

compared to the AEL 0.01 mg/kg group (ANOVA, Bonferroni).

4. Discussion

We demonstrated the antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effect of lectin

of Abelmoschus esculentus on formalin-induced temporomandibular joint

inflammatory hypernociception in rats and that its effects are mediated via central, through opioid receptors activation. AEL effects depended in part on reduction of inflammatory parameters, such as TNF-α levels, as there was a reduction of these cytokines concentration in the TMJ tissue, trigeminal ganglion and caudal subnucleus. Regarding inflammatory parameters, AEL administration also decreased plasma extravasation in synovial exudates compared with formalin group, being this parameter determined by Evans blue dye extravasation.

Alencar et al. (2007) demonstrated the effect of Vatairea macrocarpa lectin

on macrocytic activation and chemotaxis of inflammatory mediators. Assreuy et al. (2009) demonstrated the relevance of vasodilation caused by diocletian lectin (Canavalia genus) in the inflammatory process. The antinociceptive effect of

dioclenáceas lectins in the contortion model caused by acetic acid, in turn, was demonstrated by Rangel et al. (2011). The Bolivian Canavalia lectin and its

antinociceptive effect, besides its toxicity, were studied by Figueiredo et al. (2009). Additionally, our group demonstrated the anti-inflammatory and anti-nociceptive effect of Caulerpa cupressóides lectin (CcL) on zymosam-induced TMJ arthritis in

rats (Rivanor et al., 2014). However, not only anti-inflammatory effects, are demonstrated in plant lectins. Bauhinia bauhinioides and Dioclea wilsonii lectins

present proinflammatory effects by activation of proteolytic enzymes and induction of neutrophil migration, respectively (Silva et al., 2011; Rangel et al., 2011).

The study of the properties of the lectin of Abelmoschus esculentus has

anti-inflammatory effect of AEL occurs only in edema involving cell infiltrate, since edema caused by carrageenin is due to intense neutrophil infiltration and it is associated with the release of inflammatory mediators whereas dextran-induced edema involves histamine, Serotonin and bradykinin (Masnikosa et al., 2008). Similar results were found in other leguminous lectins (Assreuy et al., 2007). Soares et al. 2012, in turn, demonstrated the anti-nociceptive effect of AEL, in the same three doses tested in this work, on the model of the contortions induced by acetic acid.

Recently, our group demonstrated the antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effect of AEL on zymosan-induced TMJ hypernociception in rats, we found evidences that, at least in part, the antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of the AEL depend on the integrity of the HO-1 pathway, corroborating with other works that show that the inhibition of the HO-1 pathway is associated with the worsening of the inflammatory response (Freitas et al., 2016; Vicente et al., 2003).

The experimental use of formalin as a pro-inflammatory agent in rats, a model used in this study, is considered quite representative of the pain clinically observed in humans, and the similarity between clinical and experimental results suggests that the formalin test in rat TMJ is an effective model for assessing the mechanisms involved in TMD dysfunctions (Tjolsein et al., 1992; Roveroni et al., 2001; Clemente et al., 2004). In addition to the nociceptive effects caused by formalin, this substance also causes a local edema and plasma extravasation induced directly and indirectly. Formalin promotes vascular effects by different mechanisms that in common cause the stimulation of non-neuronal and neuronal cells. In response to stimulation, both cells release inflammatory substances causing intense edema and local plasma extravasation (Torres-Chávez et al., 2012).

anti-inflammatory effect of AEL was also observed by decreasing the plasma extravasation and reducing of TNF-α levels in periarticular tissue, trigeminal ganglion and caudal subnucleus.

We also demonstrated that the central antinociceptive response mediated by AEL in the TMJ hypernociception results from the activation of the δ and receptors, but not of μ opioid receptor. In addition, its anti-inflammatory effects

may also be related to opioid receptors. Nũnéz et al. (2007) provided the genetic,

proteomic and behavioral evidence for the involvement of peripheral opioid receptors in relieving inflammatory pain from craniofacial muscle tissues and suggested that all three subtypes of opioid receptors are involved in inflammatory responses. Napimoga et al. (2007) demonstrated that the antinociceptive effects in peripheral hypernociception of 15d-PGJ2, peroxisome proliferator-activated endogenous protein (PPAR-ᵧ), recognized as a potent anti-inflammatory mediator, promotes peripheral analgesia by endogenous opioid stimulation, suggesting that this protein Can directly activate opioid receptors present in primary sensory neurons. In addition, PPAR-ᵧ may stimulate the release of opioids that act to control inflammatory pain by resident macrophages, supporting the understanding that opioid receptors may be involved in the inflammatory response of orofacial pain.

The activation of μ receptor is related to the increasement of GRK expression, a kinase coupled to a G-protein receptor, and the activation of beta-arrestin, the protein responsible for the desensitization of receptors coupled to a G-protein (Zang et al., 1998; Raehal et al., 2005). In other words, it is required a higher phosphorylation GRK-mediated to activate the μ receptor than what is required for δ and receptors, which suggests that the expression of this protein in different cells and tissues may lead to distinct antinociceptive responses. In addition, the action of morphine on the μ receptor, the opioid agent used in this study, differs from other opioid agonists such as etorphine. It is noteworthy that both morphine and etorphine effectively activate the μ receptor, but morphine is not able to stimulate μ receptor phosphorylation by GRK in certain cell types, indicating substantial differences in the agonist sites binding of this receptor (Zang et al., 1998). Several studies have been carried out in order to elucidate the molecular bases of the μ opioid receptor and to discover new ligands with chemotypes for coupling of this receptor, such as the compound PZM21, a selective and potent agonist of μ, However, it promotes analgesia only to the affective component of the pain, what means it is more specific for reflexive spinal responses (Manglik et al., 2016).

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, we demosntrated the antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activity of AEL in a model of formalin-induced TMJ inflammatory hypernociception in rats. Additionally, our results strongly suggest that AEL efficacy involves TNF-α

inhibition and the activation of the δ and , but not of μ opioid receptor. Given the well-demonstrated anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory efficacy of AEL, the design of novel compounds is highly encouraged with the hope of defining new pharmacological targets for the treatment of inflammatory TMJ pain.

6. Acknowledgments

Nível Superior (CAPES) and Instituto de Biomedicina do Semi-Árido Brasileiro (INCT-IBSAB).

7. References

Abbott, F. V., Franklin, K. B., Connell, B., 1986. The stress of a novel environment reduces formalin pain: possible role of serotonin. European journal of pharmacology, 126(1), 141-144.

Alencar, N. M., Assreuy, A. M., Havt, A., Benevides, R. G., de Moura, T. R., de Sousa, R. B., Cavada, B. S., 2007. Vatairea macrocarpa (Leguminosae) lectin activates cultured macrophages to release chemotactic mediators. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's archives of pharmacology, 374(4), 275-282.

Assreuy, A. M. S., Fontenele, S. R., de Freitas Pires, A., Fernandes, D. C., Rodrigues, N. V. F. C., Bezerra, E. H. S., Cavada, B. S., 2009. Vasodilator effects of Diocleinae lectins from the Canavalia genus. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's archives of pharmacology, 380(6), 509-521.

Cairns, B. E., 2010. Pathophysiology of TMD pain–basic mechanisms and their implications for pharmacotherapy. Journal of oral rehabilitation, 37(6), 391-410.

Castro, M. M., Godoy, A. R., Cardoso, A. I. I., 2008. Qualidade de sementes de quiabeiro em função da idade e do repouso pós-colheita dos frutos. Ciênc. agrotec., 32(5), 1491-1495.

Chicre-Alcântara, T. C., Torres-Chávez, K. E., Fischer, L., Clemente-Napimoga, J. T., Melo, V., Parada, C. A., Tambeli, C. H., 2012. Local kappa opioid receptor activation decreases temporomandibular joint inflammation. Inflammation, 35(1), 371-376.

Clemente, J.T., Parada, C.A., Veiga, M.C.A., Gear, R.W., Tambeli, C.H., 2004. Sexual dimorphism in the antinociception mediated by kappa opioid. Neuroscience Letters, 372: 250–255.

De Rossi, S.S., Greenberg, M.S., Lui, F., Steinkeler, A., 2014. Temporomandibular Disorders: Evaluation and Management. The Medical Clinics of North America, 98 (6): 1353-1384.

Do Val, D.R., Bezerra, M.M., Silva, A.A.R., Pereira, K.M.A., Rios, L.C., Lemos, J.C., Arriaga, N.C., Vasconcelos, J.N., Benevides, N.M.B., Pinto, V.T.P., Cristino-Filho, G., Brito, G.A.C., Silva, F.R.L., Santiago, G.M.P., Arriaga, A.M.C., Chaves, H.V., 2014. Tephrosia toxicaria Pers. Reduces temporomandibular joint inflammatory hypernociception: the involvement of the HO-1 pathway. Eur. J. Pain, 18: 1280–1289.

Emshoff, R., Puffer, P., Rudisch, A., & Gaßner, R., 2000. Temporomandibular joint pain: Relationship to internal derangement type, osteoarthrosis, and synovial fluid mediator level of tumor necrosis factor-α.Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology, 90(4): 442-449.

Figueiredo, J. G., da Silveira Bitencourt, F., Beserra, I. G., Teixeira, C. S., Luz, P. B., Bezerra, E. H. S., de Alencar, N. M. N., 2009. Antinociceptive activity and toxicology of the lectin from Canavalia boliviana seeds in mice. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's archives of pharmacology, 380(5): 407-414.

Fiorentino, P. M., Cairns, B. E., Hu, J. W., 1999. Development of inflammation after application of mustard oil or glutamate to the rat temporomandibular joint. Archives of oral biology, 44(1): 27-32.

Fischer, L., Arthuri, M.T., Torres-Chavez, K. E., Tambeli, C.H., 2009. Contribution of endogenous opioids to gonadal hormones-induced temporomandibular joint antinociception. Behavioral neuroscience (5): 1129.

Gunson, M.J., Arnett, G.W., Milam, S.B., 2012. Pathophysiology and pharmacologic control of osseous mandibular condylar resorption. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 70(8): 1918-1934.

Gürbüz, I., Üstün, O., Yeşilada, E., Sezik, E., Akyürek, N., 2002. In vivo gastroprotective effects of five Turkish folk remedies against ethanol-induced lesions. Journal of ethnopharmacology, 83(3): 241-244.

Hamada, Y., Kondoh, T., Holmlund, A. B., Sakota, K., Nomura, Y., Seto, K., 2008. Cytokine and clinical predictors for treatment outcome of visually guided temporomandibular joint irrigation in patients with chronic closed lock. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 66(1): 29-34.

Kumar, R., Patil, M. B., Patil, S. R., & Paschapur, M. S., 2009. Evaluation of Abelmoschus esculentus mucilage as suspending agent in paracetamol suspension. Int J. Pharm.Tech. Res.,1(3): 658-665.

Lei, J., Fu, J., Yap, A.U., Fu, K.Y., 2016. Temporomandibular disorders symptoms in Asian adolescents and their association with sleep quality and psychological distress. Cranio: the journal of craniomandibular practice, 34(4), 242-9.

Manfredini, D., Guarda-Nardini, L., Winocur, E., Piccotti, F., Ahlberg, J., Lobbezoo, F., 2011. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review of axis I epidemiologic findings. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology, 112(4): 453-462.

Manglik, A., Lin, H., Aryal, D.K., McCorvy, J.D., Dengler, D., Corder, G., Levit, A., Kling, R.C., Bernat, V., Hübner, H., Huang, X-P., Sassano, M.F., Giguère, P.M., Löber, S., Duan, D., Scherrer, G., Kobilka, B.K., Gmeiner, P., Roth, B.L., Shoichet, B.K., 2016. Structure-based discovery of opioid analgesics with reduced side effects. Nature, 537: 185-190.

Masnikosa, R., Nikolić, A. J., & Nedić, O., 2008. Lectin-induced alterations of the interaction of insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 receptors with their ligands. Journal of the Serbian Chemical Society, 73(8-9): 793-804.