www.journalpulmonology.org

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

COPD

and

Cardiovascular

Disease

S.

André

a,

B.

Conde

b,

E.

Fragoso

c,

J.P.

Boléo-Tomé

d,

V.

Areias

e,f,

J.

Cardoso

g,h,∗,

on

behalf

of

the

GI

DPOC-Grupo

de

Interesse

na

Doenc

¸a

Pulmonar

Obstrutiva

Crónica

aPulmonologyDepartment,HospitalEgasMoniz,CentroHospitalardeLisboaOcidental,EPE(CHLO),Lisbon,Portugal

bPulmonologyDepartment,CentroHospitalardeTrás-os-MonteseAltoDouro,VilaReal,Portugal

cPulmonologyDepartment,HospitaldeSantaMaria,CentroHospitalarLisboaNorte,EPE(CHLN),Lisbon,Portugal

dPulmonologyDepartment,HospitalProf.DoutorFernandoFonseca,EPE,Amadora,Portugal

ePulmonologyDepartment,HospitaldeFaro,CentroHospitalardoAlgarve,EPE,Faro,Portugal

fDepartmentofBiomedicalSciencesandMedicine,AlgarveUniversity,Portugal

gPulmonologyDepartment,HospitaldeSantaMarta,CentroHospitalardeLisboaCentral,EPE(CHLC),Lisbon,Portugal

hNovaMedicalSchool,NovaUniversity,Lisbon,Portugal

Received25August2018;accepted20September2018 Availableonline7December2018

KEYWORDS Chronicobstructive pulmonarydisease; Cardiovascular Disease; Comorbidity; DiagnosticTechniques andProcedures

Abstract COPDisoneofthemajorpublichealthproblemsinpeopleaged40yearsorabove.It iscurrentlythe4thleadingcauseofdeathintheworldandprojectedtobethe3rdleadingcause ofdeathby2020.COPDandcardiaccomorbiditiesarefrequentlyassociated.Theyshare com-monriskfactors,pathophysiologicalprocesses,signsandsymptoms,andactsynergisticallyas negativeprognosticfactors.Cardiacdiseaseincludesabroadspectrumofentitieswithdistinct pathophysiology,treatmentandprognosis.Fromanepidemiologicalpointofview,patientswith COPDareparticularlyvulnerabletocardiacdisease.Indeed,mortalityduetocardiacdiseasein patientswithmoderateCOPDishigherthanmortalityrelatedtorespiratoryfailure.Guidelines reinforcethatthecontrolofcomorbiditiesinCOPDhasaclearbenefitoverthepotentialrisk associatedwiththemajorityofthedrugsutilized.Ontheotherhand,thetruesurvivalbenefits ofaggressivetreatmentofcardiacdiseaseandCOPDinpatientswithbothconditionshavestill notbeenclarified.Giventheirrelevanceintermsofprevalenceandprognosis,wewillfocusin thispaperonthemanagementofCOPDpatientswithischemiccoronarydisease,heartfailure anddysrhythmia.

©2018SociedadePortuguesadePneumologia.PublishedbyElsevierEspa˜na,S.L.U.Thisisan openaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

∗Correspondingauthor.JoãoCardosoMD,PulmonologyDepartment,HospitaldeSantaMartaCentroHospitalardeLisboaCentral,EPE

(CHLC)1169-1024Lisbon,Portugal.Tel.:++351213594268;fax:++351213560368..

E-mailaddress:joaocardoso@meo.pt(J.Cardoso).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pulmoe.2018.09.006

2531-0437/©2018SociedadePortuguesadePneumologia.PublishedbyElsevierEspa˜na,S.L.U.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCC BY-NC-NDlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Chronic diseases represent the main cause of premature death in adults worldwide.1 Chronic respiratory diseases

in particular, suchasasthma and chronicobstructive pul-monarydisease(COPD),weredirectlyresponsibleforover 3 million deaths in 2002 and affect hundreds of millions more.1,2

COPDisoneofthemajorpublichealthproblemsinpeople aged40yearsormore.3,4Itiscurrentlythe4thleadingcause

ofdeathintheworldandprojectedtobethe3rdleading causeofdeathby2020.2 On theotherhand, accordingto

someauthors,it istheleadingcauseof chronicmorbidity andmortality,anditispredictedtobein7thplaceonthe listofworlddiseaseburdenin2030.1,2

COPD and cardiac comorbidities are frequently associ-ated. They share commonrisk factors, pathophysiological processes, clinical signs and symptoms, and act syn-ergistically as negative prognostic factors.5---7 Pulmonary

hypertension, right ventricular dysfunction, dysrhythmia andischemiccoronarydiseaseareknownconsequencesof COPDprogression.8Morerecently,ithasbeendemonstrated

that, in patients with COPD, left ventricular dysfunction hasanegativeimpactonexercisetolerance,being associ-atedwithanxietyanddepression,reducedcarbonmonoxide (CO) diffusion and higher prevalence of right ventricular dysfunction.9 Similarly, the physical activity impairment

imposedbyeachoftheabovementionedpathologies wors-enstheothersandlimitsqualityoflife.10

Patients with COPD areparticularly vulnerable to car-diacdisease,withahigherincidenceandprevalence (age andgender-adjusted)whencomparedwithpatientswithout COPD.Indeed,mortalityduetocardiacdiseaseinpatients withmoderateCOPDishigherthanmortalityattributedto causesrelatedwithrespiratoryfailure.7,11---15

Eveninthegeneralpopulation,immediatelyafteracute respiratoryinfections,ahigh-risktimeperiodfor cardiovas-cular eventshas beendescribed.16 The sameis true after

acuteexacerbations inCOPDpatients,17 anda higher

fre-quencyofCOPDexacerbationshasbeen associatedwitha higherincidenceofmyocardialinfarction.18Inaddition,

car-diacbiomarkerssuchasC-reactiveProtein(CRP),fibrinogen, Brain-type Natriuretic Peptide (BNP), N-terminal proBNP (NT-proBNP), troponin, and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor(VEGF)arehigherin patientswithCOPD exacerba-tionsandtheseareindependentriskfactorsformortality.19

COPDprevalenceinpatientswithheartfailure(HF)varies between11%and52%intheUSAandbetween9%and41%in Europe,5whiletheprevalenceofcardiacdiseaseinpatients

withCOPDvariesbetween14%and33%.9,20 The

vulnerabil-itytoandimpactofcardiacdiseaseinpatientswithCOPD isrecognizedandhasbeenimplicitin theguidelinessince 2013.21 However,neitherthemanagementof

cardiovascu-lar disease (CVD)nor assessment of cardiovascularrisk in patientswithCOPDhasbeenstudiedwell.22

The traditionally established and disseminated fearof beta2-agonist use in patients with cardiac disturbances and of beta-blocker (BB) use in patients with respiratory diseasesisoneofthereasonsunderlyingsuboptimal treat-ment of both conditions when they coexist, as opposed topatientswithisolatedCOPDor CVD.Currentguidelines

reinforcetheidea thatthecontrol ofcomorbidities hasa clear benefitover the potential risks associated withthe useofthesedrugsandthereisnoclearevidencesustaining thesefears.5---7,10,23 Forexample,Mesquita etalconducted

aresearchstudyinvolving COPDpatientswithandwithout impairedleftventricularejectionfraction(LVEF)andfound thatonlyhalfofthecohortwithimpaired LVEFwasunder targetedtherapyforheartfailure.9

Ontheotherhand,thetruesurvivalbenefitsofaggressive treatmentofcardiacdiseaseandCOPDinpatientswithboth conditionsarestillnotclarified.2 Cardiac diseaseincludes

abroadspectrumofentitieswithdistinctpathophysiology, treatmentandprognosis.Giventheirrelevanceintermsof prevalence and prognosis, we will focus in this paper on themanagementof COPDpatientswithischemic coronary disease,heartfailureanddysrhythmia.

Pathophysiology

of

COPD

and

Cardiovascular

disease

CardiovasculardiseaseandCOPD

COPDis a chronic pulmonary disease with an often indo-lentevolutionandsystemicrepercussions.2Itsmaincause

isconstantand prolongedexposure tocigarettesmoke or othernoxiousgasesandparticleswhichleadtoreducedair flowandpulmonaryhyperinflationduetovaryingdegreesof airwayobstructionandemphysema,aswellastosystemic inflammation,ultimately causing skeletal muscle dysfunc-tion,respiratory failure, and diminished peripheral blood flow.4,24---26

In patients with COPD and CVD, the interaction of pathophysiologicprocessesof therespiratory, cardiacand vascularsystemsiscomplexandmodulatedbytheactionof pharmacologicagentsusedinthetreatmentofboth condi-tions,someofwhichhavetrueantagonisticeffectsonthe autonomicnervoussystem.Thepotentialsideeffects associ-atedwiththeuseofthesedrugstotreatCOPDmaytranslate intoadverseeventsfromacardiovascularperspective(and vice-versa).7,27

The paradigm of the above is the use of BBs in the treatmentofcardiovasculardiseasesandbeta2-agonistsin thetreatmentofrespiratorydiseases.7,28---31Theapparently

opposed actions on sympathetic tone modulate cardio-vascular and respiratory response and will inadvertently haveimplicationsfor bothsystems,whichisnota contra-indicationfortheoptimizedtreatmentofbothpathologies, asdiscussedinthispaper.

COPDeffectsoncardiacfunction

Both diastolic and systolic dysfunction of the right and left ventricle seem to be frequent in COPD patients.8,32

Direct compromise of right ventricle (RV) is a conse-quenceofpulmonaryparenchymaldestructionandhypoxic vasoconstriction resulting in increased pulmonary vascu-larresistance.8,32 Rightventricledilationandhypertrophy,

asa consequence of raised pulmonary pressure,can lead toseptumdisplacement tothe leftventricle,

compromis-ingleftventricularfilling,stroke volume(SV) andcardiac output.33,34

Hypoxia leads to vasodilation in systemic arteries and vasoconstriction in the pulmonary vascular bed.35

How-ever,thepulmonaryhemodynamicresponsestohypoxiaare quitevariable.35Chronichypoxiaaffectsthepulmonary

vas-culature throughboth tonic vasoconstrictionand vascular remodellingwithmiointimalhyperplasiaof thepulmonary vascularbed.35

Thus,inthesettingofCVD,varyingdegreesofhypoxia, lung hyperinflation, secondary erythrocytosis, and loss of pulmonaryvascular surfaceareaallleadtotheinevitable association of CVD with varying degrees of pulmonary hypertension.35

Inaddition,theleftventriclemaybedirectly affected byairflowlimitation,butmuchlessisknownregardingthe interactionofsubclinicallungfunctionimpairmentwithleft ventricularfunction.35,36Also,theseunderlyingmechanisms

mayberesponsibleforleftventricularfailuresymptomsin COPDexacerbations.35,36

Repeatedandcyclicincreasesinventricularwalltension arethought tobe oneof the mechanisms responsible for sympathetic nervous system activation in these patients, perhapscontributingtotheirpropensity tosaltandwater retention, aswell asthe developmentof systemic hyper-tensionandleftventricularhypertrophy.35,36

Somestudieshave reportedthat amoderatelyreduced ForcedExpiratoryVolumein 1second (FEV1), an

indepen-dent risk factor for CVD, is associated with an increased incidenceofHFinolder37 andmiddle-agedindividuals.38,39

Impairedpulmonary functioninyoungadulthood precedes leftventriculardysfunctionlaterinlife,40andalinear

asso-ciationofdecreasingFEV1/ForcedVitalCapacity(FVC)ratio

andincreasingemphysema(hyperinflation)withleft ventric-ularend-diastolicvolume,SV andcardiacoutputhasbeen shown.41,42

Pulmonaryhypertension,elevatedrightventricularfilling pressureandraisedintrathoracicpressurearealso respon-sibleforthehigherincidenceofatrialarrhythmiasinCOPD patients, probably due to a dual effect of direct raised RV pressure and pro-inflammatory environment in COPD patients.35ThegreaterthedegreeofRVdysfunctionat

base-line,thegreaterthehemodynamicsignificanceofanyadded vascularload.35

ChronicinflammationinCOPD

Besides classical pathological models based on lung and systemic hemodynamics, there is a growing evidence on theroleoftheunderlyinglocalandsystemicinflammatory environment.Chronicinflammation in COPDinvolves both innate and adaptive immunityand is most pronounced in the bronchial walls.43 This inflammatory process in COPD

hasamarkedheterogeneity.Itresultsinbothemphysema, with parenchymal involvement, and chronic bronchitis, whichpredominantly affectsthe smallairways.43 Previous

studies have found persistent chronic inflammatory fea-tures in 16% of COPD patients and this was associated with a worse prognosis with a six-times higher mortality comparedtopatientswithapauci-inflammatory profile.44

Once established, inflammation in COPDis persistent and

progresses over time, despite elimination of smoking or other environmental factors.45 Although the factors that

drive inflammation in COPD have not been clearly estab-lished,autoimmunity,embeddedparticlesfromsmokingand chronicbacterialinfectionhaveallbeenproposedtoplaya role.46

Theinflammatoryprocessleadstoanincreaseinthe tis-suevolumeofthebronchialwall,characterizedby infiltra-tionofthewallbybothinnate(macrophages/neutrophils) andadaptive inflammatoryimmune cells (CD4,CD8 andB lymphocytes) withlymphoidfollicles formation. Indeed,a major factor associated with lung inflammation in COPD is autoimmunity. Lee et al showed that emphysemais an autoimmunediseasecharacterizedbythepresenceof anti-elastinantibodyandT-helpertype1(Th1)responses,which correlatewithemphysemaseverity.47,48

Severalstudieshave highlighted theimportanceof the lung microbiome in lung disease.49---51 The most common

bacteria isolated from the lungs of patients with COPD arenon-typeableHaemophilusinfluenzae(NTHi).NTHihas been shown to induce changes in COPD in an animal model52 and new strains are also associated with COPD

exacerbations.53Thisagenthasalsobeenshowntoactivate

lung T cells and cause the expression of reactive oxygen speciesandproteasesinpatientswithCOPD.54 Thevicious

cycleofinflammation-infectionincreasesexacerbations.As evidence is growing about these mechanisms,efforts are being made to identify and define clinical and analytical biomarkerswithprognosticvalue.

COPDandCVDbiomarkers

In a prospective cohort study from the Copenhagen City HeartStudy(2001-2003)andtheCopenhagenGeneral Pop-ulationStudy(2003-2008)population, theroleofelevated levels ofinflammatory biomarkers in individuals with sta-bleCOPDaspredictorsofexacerbationshasbeenstudied.55

The authors reportedthat concomitantelevated levels of C-reactive protein(CRP), fibrinogen, andleukocytes were associatedwithanincreasedriskoffrequentexacerbations inindividualswithstableCOPD.Comparedtopatientswith normal levels of these biomarkers,individuals withthree elevated inflammatory biomarkers had an approximately 4-times higher risk of having frequent exacerbations dur-ingthefirstyear offollow-up.Itis notclearwhetherthis mightreflectan underlyingbacterialcolonizationprocess, persistentlatentviralinfectionsintheairways orahighly inflammatoryenvironment.55

The pathophysiological mechanisms and interaction between COPD and cardiac disease are complex, involv-ingmultiplebiologicalandimmunemechanismsmodulating cardiac, respiratoryand systemiceffects.55 However,it is

notpossibletoexactlyascertaintheimpactofeachsingle mechanisminthewholeprocess.55

Fromaclinicalperspective,somebiomarkershavebeen tested:

C-reactiveProteinisapotentialbiomarkeroflowgrade systemic inflammation and atherosclerosis in COPD. The declineinFEV1/FVCandFEV1iscorrelatedwithanincreased

higherinpatientswithbothmoderatetosevereobstruction andhigherCRPlevels.56,57

Fibrinogen is an acute phaseprotein that is has been described as a marker of COPD activity. High levels of this marker are a predictor of severity and risk of COPD exacerbations.58,59

Brain-type Natriuretic Peptide (BNP) and N-terminal proBNP(NT-proBNP)areearlyandsensitivebiomarkersfor thediagnosis of HFassociatedwithdecreased left ventri-cleejectionfraction,leftventricularhypertrophy,increased leftventricle fillingpressure, acute myocardial infarction and ischemia.56,60,61 They arealsohigher in patients with

pulmonary disorders, right ventricular dysfunction, pul-monaryhypertensionandcorpulmonale.InCOPDpatients, the increase in BNPand NT-proBNPis proportionalto the severityof rightventricular dysfunction.56,60,61 BNPis also

highinpatientswithstableCOPDandnopulmonary hyper-tension.In additionthereis a strongcorrelation between BNP levels and leftventricular ejection fraction and sys-tolic pressure of the pulmonary artery.56,60,61 Finally, BNP

levelshavealsobeen associatedtomortalityriskin COPD patients.56,60,61

Troponinis elevatedin 18-27%ofpatients hospitalized duetoaCOPDexacerbationandisanindependentpredictor of mortalitybothduring theexacerbationandin thelong term.12,62---66

VEGF(VascularEndothelialGrowthFactor)is an impor-tant biomarker of prognosis in CVD. VEGF regulates angiogenesis,promotingthemigrationandproliferationof endothelialcells,increasingvascularpermeabilityand mod-ulatingthrombogenicity.PatientswithCOPDexacerbations havehigherlevelsofcirculatingVEGF.57

Surfactant protein D is synthesized and secreted by bronchialandalveolarepithelialcellsandcanbedetectedin humanplasma.Ithasamajorroleinimmuneand inflamma-toryregulationinthelungandisalsoexpressedincoronary arteries,havingananti-inflammatoryrole.57

COPD

and

Concomitant

CVD

assessment

methods

PatientswithCOPDandcardiovascular comorbidityshould have respiratory function, cardiac function, and systemic inflammatorystatusassessments.Theseassessmentsshould beconducted differently depending onwhethera patient hasstableCOPDoranacuteexacerbation.

A. ForpatientswithstableCOPD,aclinicalandfunctional assessmentshouldinclude:

• Complete clinical history and physical examination, including therecommended dyspneaandquality of life assessment questionnaires modified Medical Research Council(mMRC)andCOPDAssessmentTest(CAT). • Laboratory assessment including complete blood count,

arterialbloodgasanalysis,CRP,NT-proBNPand/orBNP. • Spirometry,staticlungvolumesandcarbonmonoxide

dif-fusioncapacity(DLCO). • ChestX-ray.

• 12-lead electrocardiogram and further assessment with anechocardiogram,ifneeded.

Symptoms Risk Factors Patient with

COPD

Lab: CRP, NT-proBNP, complete Blood count

Patient with CVD

ECG Echocardiogram

OPTIMIZED TREATMENT FOR CVD AND COPD SPIROMETRY (Post-BD) NORMAL CVD CONFIRMED COPD CONFIRMED’ NO COPD

Refer patient in case of diagnostic uncertainty

Patient evaluation by cardiologist

Patient evaluation by pulmonologist

Repeat anually and/or refer patient in case of diagnostic uncertainty

Figure 1 Proposed evaluation algorithm for CVD in stable

COPD.

Forpatientswithknownconcomitantcoronaryartery dis-ease or cardiac disease, a specific assessment should be done according tothe current guidelines, asproposed by theauthors--- Figure1.Asixminutewalkingtestand car-diopulmonaryexercisetestingarerecommendedifthereis nospecificcontra-indication.

B. Forpatientswithcardiacdiseaseandsigns/symptoms or risk factors for COPD, COPD should be actively investigated,so,in additiontotheclinical assessment specific for cardiac disease, spirometry, lung volumes andDLCOmeasurementsshouldalsobeperformed. Addi-tionalassessmentsshouldbecarriedoutaccordingtothe resultsobtainedfromtherespiratoryandcardiacspecific functionalassessments.

Forboth patients mentioned in A and Bsections, who frequently undergo thoracic CT scan, it is important to keepinmind thatpatients undergoingevaluationfor car-diacdisease,coronaryangio-CTmayshowradiologicsignsof COPD,andCOPDpatientsundergoingthoracicCTmayshow coronarycalcificationorcardiomegalysuggestingunderlying cardiacdisease.67

Due to the multifactorial, clinical interactions and a broadspectrumofsignsandsymptoms,therearenospecific guidelinesfor when and howto performthese functional cardio-respiratoryassessments.Therearebroadrulesthat shouldbetailored toeach individualpatientaccording to clinicalexpertise,andtheauthorsproposeaspecific assess-mentalgorithmforCVDinstableCOPDpatients---Figure1.

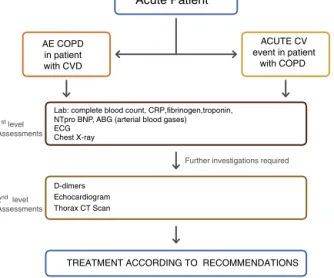

C. ForpatientswithCOPDexperiencinganacute exacer-bation:

• Completeclinicalhistoryandphysicalexamination. • Laboratory assessment includingcomplete blood count,

leukocytecount,platelets,CRP,arterialbloodgas analy-sis,fibrinogen,NT-proBNPorBNPandtroponinI. • ChestX-ray.

• 12-leadelectrocardiogram.

The purpose is to establish the main pathophysiologic mechanismsunderlying theacuteexacerbationwhenboth

Acute Patient

AE COPD in patient with CVD

Lab: complete blood count, CRP,fibrinogen,troponin, NTpro BNP, ABG (arterial blood gases) ECG Chest X-ray ACUTE CV event in patient with COPD 1st level Assessments D-dimers Echocardiogram Thorax CT Scan

2nd level

Assessments

Further investigations required

TREATMENT ACCORDING TO RECOMMENDATIONS

Figure2 Proposedevaluationalgorithmintheacutesetting.

pathologiesco-exist:decompensatedcardiacdisease,COPD exacerbation,underlyinginfectionor anotherconcomitant diagnosis. Therapeuticapproachshould bedriven accord-ing to the diagnosis associated with the acute clinical decompensation. The treatment of thesepatients can be quitechallenging, especiallyin theacutesetting. Indeed, although the reasonfor decompensation can be primarily cardiovascularorrespiratoryinnature,theauthorspropose thatbothconditionshave tobesimultaneouslyaddressed, because of the constant two-way interaction of dysfunc-tionalmechanisms---Figure2.

COPD

and

CVD

Pharmacological

Treatment

The presence of comorbidities should not modify COPD treatment and comorbidities should be treated per usual standardsregardlessofthepresenceofCOPD.2

CardiovasculardrugsinCOPDpatients

Campo et al conducted a review on the safety and effi-cacy of cardiovascular and respiratory drugs in COPD patientswithconcomitantCVD.Antiplateletagents, antico-agulants,angiotensinconvertingenzymeinhibitors(ACEi), angiotensinreceptorblockers(ARBs),andBBsarethemost commonlyprescribeddrugsinpatientswithCVD.68

Antiplateletagentsandanticoagulants

Itisreasonabletothinkthatitmightallbeusefulinpatients withbothCOPDandCVDsincethrombocytosisisassociated withincreasedmortalityinCOPD.COPDpatientssubmitted topercutaneouscoronaryinterventionshavehigherplatelet reactivity, and antiplatelet agents and anti-aggregation therapymayactasbeneficialinpulmonaryhypertensionand inCOPDpatientsatriskofatrialfibrillation.69---71

According tothe available evidence,antiplatelet ther-apyhasbeenassociatedwithareduced1-yearmortality(OR 0.63;95%CI0.47---0.85)inpatientswithhospitaladmission duetoacuteexacerbationofunderlyingCOPD.68 Similarly,

Ekstrom etal showed thatantiplatelet agents were asso-ciated with a significant reduction of mortality in COPD

patients(HR0.86;95%CI0.75---0.99).30However,thesedata

arebasedonpost-hocanalysisandnoRCTswereconducted specificallyonthisissue.

The benefit of anticoagulant drugs relies on the concomitant CVD independently of the COPD status.68,72

However, COPD seems to be a risk factor for bleeding complications,73,74namelyinpatientswithatrialfibrillation

onanticoagulanttherapy.75,76

ACEiandARBs

Smallclinicaltrialsandobservationalstudieshavesuggested an interactionbetween ACEi andFEV1 declinein smokers

whilst otherssuggest abenefitin pulmonary hypertension inpatients treatedwithARBs.68,77,78However,thereisnot

sufficientevidencetodefineaspecificindicationofACEior ARBsinCOPDpatientsotherthanfortheCVD.68,77,78

BBs

Amuchlargerbodyofevidenceandliteratureisavailable about indication and prescription of BBs. Bronchocon-striction from -blocker use is due to antagonism of pre-junctional and post-junctional -2 receptors, which uncoverscholinergictoneresultinginairwayconstriction.6

Given this rationale, -1 selective antagonists potentially exhibitasmalldegree ofdose-related-2receptor block-ade.Ameta-analysisincludingstudiesuntil2011concluded that BBs have a positive effect in COPD patients with ischemic heart disease, and cardio-selective BBs produce no change in FEV1 or respiratory symptoms, nor do they

affecttheFEV1treatmentresponsetolongacting-2

ago-nists(LABA),anditshowedapooledrelativeriskreduction inmortalityforCOPDpatientsreceivingBB(RR0.69,95%CI 0.62---0.78).68,79Apossibleexplanationforthispositive

inter-actionistheprotectoreffectofcardio-selectiveBBagainst the potential chronotropic, inotropic and pro-arrhythmic effectsofLABA.

Despitethe safety of BBsin COPD patients, the treat-ment with BBs or ACEi/ARB was found to be significantly lowerinCOPDpatientswithconcomitantHFthaninpatients withHFalone.28---30 The useof BBshasalsobeen reported

tobe41%to58%lowerthanACEi/ARBinpatients treated withICS/LABA/LAMAorSAMA/SABA.6,68Averyrecentreview

proposes that potential ways of dealing this dilemma of whether or not to use BBs in COPD patients include the developmentofhighly1-selective-blockersortheuseof non--blockingheartratereducingagents,suchas ivabra-dine, if these are proven to be beneficial in randomised controlledtrials.80

Theauthorsconclude that theabove mentioned drug classes forCOPDcanbesafelyusedifconcomitantCVD is anindication.

TheuseofcardioselectiveBBsinCOPDpatientsseems to be safe and may be suggested if indicated for the CVD per se. Cardio-selective BBs, if indicated, may be recommended to COPD patients, regardless of pulmonary comorbidity.6,31,68,81

RespiratorydrugsinCVDpatients

Anybronchodilatoris potentiallypro-arrhythmic.Although some studies report an incidence of tachydysrythmias in

LAMAtreatedCOPDpatients,68 theUPLIFT82 andTIOSPIR83

trials did not show an increased incidence of major car-diac events. The cardiovascular safety of LABA, LAMA, ICS/LABA,orLABA/LAMAtherapyiswellestablished.7,10,84---88

Specifically, a fixed once-daily combination of inda-caterol/glycopyrroniumhasshowncardiovascularsafetyin COPD patients, with or without comorbid CVD.23,85,89---91

Moreover, a very recent RCT has shown that dual bron-chodilation with indacaterol/glycopyrronium significantly improvedcardiac functioninpatientswithCOPDandlung hyperinflation.92

Regarding tachydysrythmias2 thereis noevidencethat

theCOPDtreatmentapproachshouldbechangedduetothe diagnosisofatrialfibrillationoranotherCVD.

Specificconsiderationsregardingshort-actingbeta agonists(SABAs)

Due totheir 2-adrenergic action, SABAs may precipitate atrial fibrillation and hamper the control of ventricular response,andhavethepotentialtoinducesinustachycardia atrestanddysrhytmiasinsusceptiblepatients.93However,

ifclinicallyindicated,theyshouldbeusedasrescue medi-cation.

SpecificconsiderationsregardingLABAs

AlthoughthecardiovascularsafetyofLABAsinCOPDpatients remainsacontroversialissue,arecentmeta-analysisof24 RCTsconcludedthatitissafetouseLABAsinCOPDpatients withCVcomorbidities.87

SpecificconsiderationsregardingLAMAs

LAMAsaresafewithinawiderangeofdosesandclinical con-texts.Someconcernshavebeenraisedregardingtiotropium administrationvia theRespimat® device, but theTIOSPIR

studyshowedittobeassafeastiotropiumadministredvia theHandihaler®.Glycopyrroniumalsohasafavorablesafety

profilewithnoincreaseinCVrisk.Thesafetyprofileisvery similaramongstthedifferentLAMAs.2,79,88,94,95

SpecificconsiderationsregardingICS

ICSarenotusedasmonotherapyinCOPDpatients.ICSsafety data areless robustthan safetydata on bronchodilators. There is nounequivocal evidence regarding safety of ICS usedascombinationtherapyonCOPDpatientswith comor-bidCVD.7,79,88

Specificconsiderationsregardingmethylxanthines

Methylxanthines have a narrow therapeutic window and their toxicity is well established and dose-dependent. WithregardtoCVD, theirpro-arrhythmiceffectshouldbe highlighted.Thereisalsoapotentialpharmacokinetic inter-action with warfarinand digoxin.2 Theophyllinehas been

suggested tohave an anti-inflammatoryeffectinpatients withCOPD.96

Inconclusion,ICS,LABAs,LAMAsandassociationscanbe consideredsafeinCOPDpatientswithconcomitantcardiac disease.

Prognostic

Implications

COPDpatientswithconcomitantCVDhaveaworseprognosis thansimplythesumoftheprognosisofeachdisease. How-ever,it isdifficult toestablish ahazardratioor riskratio foraspecificpatientorgroupofpatients,duetothe com-plexetiologicandpathophysiologicinteractionnetworkthat underlies both diseases.20,23 Much of the literature relies

onepidemiology data and management of cardiovascular comorbiditiesinCOPD.Muchlessisdescribedregardingthe prognosticimplicationsof differentcardiovascular comor-biditiesinCOPDpatientsandevenlessinsubgroupsofCOPD patients,bothaccordingtoGOLDstagesandage.

Summarizing the literature, the risk of CVD in COPD istwo tothree-fold greater thanthe risk associated with smoking.97 COPD is also independently associated with

meaningful cardiovascular events.98 FEV

1 is an

indepen-dent risk factor for cardiovascular disease regardless of age,gender,tobaccoaddiction,cholesterol,andeducation level/social class.98 Reduced pulmonary function in COPD

isassociatedwithincreasedincidenceofall-cause mortal-ity,cardiovascular-relatedmortality,myocardialinfarction andarrhythmias.99IntheTORCHtrial,cardiovasculardeaths

occurredin26%ofpatients,14andintheUPLIFTtrialin18.8%

ofpatients.100Bothtrialsincludedpatientswithmoderateto

severeCOPD.Cardiovasculardeathremainsthemost com-moncauseofmortalityinCOPDpatients.101

Conclusions

In conclusion, the identification and proper treatment of cardiac comorbidity is a very important measure in the management of COPD, as prognosis in COPD is greatly affectedbythepresenceofCVD.Duetopathophysiological andinflammatoryinteractionsbetweenCOPDand cardiovas-culardisease,thepresenceofcardiaccomorbiditiesshould beactivelyinvestigatedinallCOPDpatients,bothinstable conditionsandinthecontextofexacerbations.

Role

of

Funding

Source

Fundingfor this paperwasprovidedby NovartisPortugal. Fundingwasusedtoaccessallnecessaryscientific bibliog-raphyandcovermeetingexpenses.NovartisPortugalhadno roleinthecollection,analysisandinterpretationofdata,in thewriting ofthepaperandinthedecisiontosubmitthe paperforpublication.

Conflict

of

Interest

SA declares having received speaking fees from Novartis andparticipatingonscientificadvisoryboardssponsoredby Novartis. BCdeclares having received speaking fees from Novartisandparticipatingonscientificadvisoryboards spon-sored by Novartis. EF declares having received speaking fees from Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Menarini, AstraZeneca, Teva, Medinfar, Tecnifar and Mundipharma andparticipatingonscientificadvisoryboardssponsoredby BoehringerIngelheim.JPBTdeclareshavingreceived speak-ingfeesfromNovartis.VAdeclareshavingreceivedspeaking

feesfromNovartis, Medinfarand GSK.JC declareshaving given presentations at symposia and/or served on scien-tificadvisoryboardssponsoredbyAstraZeneca,Boehringer Ingelheim,GSK,MundipharmaandNovartis.

References

1.World Health Organization. Global surveillance, prevention andcontrolofCHRONICRESPIRATORYDISEASES.A comprehen-siveapproach.2007.

2.GlobalInitiativeforChronicObstructiveLungDisease.Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of ChronicObstructivePulmonaryDisease.In.2018.

3.Raherison C,Girodet PO.Epidemiology ofCOPD.EurRespir Rev.2009;18:213---21.

4.Atsou K, Chouaid C,Hejblum G. Variability of the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease key epidemiological data in Europe:systematicreview.BMCMed.2011;9:7.

5.BaumC,OjedaFM,WildPS,RzayevaN,ZellerT,SinningCR, etal.Subclinicalimpairmentoflungfunctionisrelatedtomild cardiacdysfunctionandmanifestheartfailureinthegeneral population.IntJCardiol.2016;218:298---304.

6.Lipworth B, Skinner D, Devereux G, Thomas V, Ling Zhi Jie J, Martin J, et al. Underuse of beta-blockers in heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart. 2016;102:1909---14.

7.VestboJ,AndersonJA,BrookRD,CalverleyPM,CelliBR,Crim C, et al. Fluticasonefuroate and vilanterol and survivalin chronicobstructivepulmonarydiseasewithheightened cardio-vascularrisk(SUMMIT):adouble-blindrandomisedcontrolled trial.Lancet.2016;387:1817---26.

8.FalkJA,KadievS,CrinerGJ,ScharfSM,MinaiOA,DiazP. Car-diacdiseaseinchronicobstructivepulmonarydisease.ProcAm ThoracSoc.2008;5:543---8.

9.MesquitaR,FranssenFM,Houben-WilkeS,Uszko-LencerNH, Vanfleteren LE, Goertz YM, et al. What is the impact of impaired left ventricular ejection fraction in COPD after adjustingforconfounders?IntJCardiol.2016;225:365---70. 10.Watz H, Mailander C, Baier M, Kirsten A. Effects of

inda-caterol/glycopyrronium(QVA149)onlunghyperinflationand physicalactivityinpatientswithmoderatetosevereCOPD: arandomised,placebo-controlled,crossoverstudy(TheMOVE Study).BMCPulmMed.2016;16:95.

11.FragosoE,AndreS,Boleo-TomeJP,AreiasV,MunhaJ,Cardoso J. Understanding COPD: A vision on phenotypes, comor-biditiesand treatmentapproach. RevPortPneumol (2006). 2016;22:101---11.

12.Anthonisen NR, Connett JE, Kiley JP, Altose MD, Bailey WC, Buist AS, et al. Effects of smoking intervention and theuse ofaninhaled anticholinergicbronchodilatoronthe rate of decline of FEV1. The Lung Health Study. Jama. 1994;272:1497---505.

13.Sin DD, AnthonisenNR, Soriano JB, AgustiAG.Mortality in COPD:Roleofcomorbidities.EurRespirJ.2006;28:1245---57. 14.McGarveyLP,JohnM,AndersonJA,ZvarichM,WiseRA.

Ascer-tainmentofcause-specificmortalityinCOPD:operationsofthe TORCHClinicalEndpointCommittee.Thorax.2007;62:411---5. 15.SidneyS,SorelM,QuesenberryCPJr,DeLuiseC,LanesS,Eisner MD. COPD and incident cardiovascular disease hospitaliza-tionsandmortality:KaiserPermanenteMedicalCareProgram. Chest.2005;128:2068---75.

16.Clayton TC, Thompson M, Meade TW. Recent respiratory infection and risk of cardiovascular disease: case-control study through a general practice database. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:96---103.

17.DonaldsonGC,HurstJR,SmithCJ,HubbardRB,WedzichaJA. Increasedrisk ofmyocardialinfarctionand stroke following exacerbationofCOPD.Chest.2010;137:1091---7.

18.McAllister DA, Maclay JD, Mills NL, Leitch A, Reid P, Car-ruthersR,etal.Diagnosisofmyocardialinfarctionfollowing hospitalisation for exacerbation of COPD. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:1097---103.

19.Chang CL, Robinson SC, Mills GD, Sullivan GD, Karalus NC, McLachlanJD,etal.Biochemicalmarkersofcardiac dysfunc-tionpredictmortalityinacuteexacerbationsofCOPD.Thorax. 2011;66:764---8.

20.MapelDW,DedrickD,DavisK.Trendsandcardiovascular co-morbiditiesofCOPDpatientsintheVeteransAdministration MedicalSystem,1991-1999.COPD.2005;2:35---41.

21.GlobalInitiativeforChronicObstructiveLungDisease.Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Updated 2013. In. 2013.

22.QuintJK,HerrettE,BhaskaranK, TimmisA,Hemingway H, Wedzicha JA, et al. Effect of beta blockers on mortality aftermyocardialinfarctioninadultswithCOPD:population basedcohortstudyofUKelectronichealthcarerecords.Bmj. 2013;347:f6650.

23.BatemanED, FergusonGT, BarnesN, Gallagher N,Green Y, HenleyM,etal.DualbronchodilationwithQVA149versus sin-gle bronchodilator therapy: the SHINE study. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:1484---94.

24.LaizoA.[Chronicobstructivepulmonarydisease-areview]. RevPortPneumol.2009;15:1157---66.

25.AntonioC,GoncalvesAP,TavaresA. [Pulmonaryobstructive chronic disease and physical exercise]. Rev Port Pneumol. 2010;16:649---58.

26.PereiraAM,Santa-ClaraH,PereiraE,SimoesS,RemediosI, Cardoso J, et al. Impact of combined exercise on chronic obstructivepulmonarypatients’stateofhealth.RevPort Pneu-mol.2010;16:737---57.

27.SalpeterSR,OrmistonTM,SalpeterEE.Cardiovasculareffects ofbeta-agonistsinpatientswithasthmaandCOPD:a meta-analysis.Chest.2004;125:2309---21.

28.Farland MZ, Peters CJ, Williams JD, Bielak KM, Heidel RE, RaySM.beta-Blocker useandincidence ofchronic obstruc-tive pulmonary disease exacerbations. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47:651---6.

29.EtminanM,JafariS,CarletonB,FitzGeraldJM.Beta-blocker use and COPD mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis.BMCPulmMed.2012;12:48.

30.EkstromMP,HermanssonAB,StromKE.Effectsof cardiovascu-lardrugsonmortalityinseverechronicobstructivepulmonary disease.AmJRespirCritCareMed.2013;187:715---20. 31.Mentz RJ, Wojdyla D, Fiuzat M, Chiswell K, Fonarow GC,

O’Connor CM.Associationof beta-blocker useand selectiv-itywithoutcomesinpatientswithheartfailureandchronic obstructivepulmonarydisease(fromOPTIMIZE-HF).AmJ Car-diol.2013;111:582---7.

32.StoneIS,BarnesNC,JamesWY,MidwinterD,BoubertakhR, Follows R, et al. Lung Deflation and Cardiovascular Struc-tureandFunctioninChronicObstructivePulmonaryDisease. ARandomized ControlledTrial. AmJRespirCrit CareMed. 2016;193:717---26.

33.MacNee W. Pathophysiology of cor pulmonale in chronic obstructivepulmonarydisease.PartOne.AmJRespirCritCare Med.1994;150:833---52.

34.Vonk-NoordegraafA.Theshrinkingheartinchronicobstructive pulmonarydisease.NEnglJMed.2010;362:267---8.

35.ForfiaPR,VaidyaA,WiegersSE.Pulmonaryheartdisease:The heart-lunginteractionanditsimpactonpatientphenotypes. PulmCirc.2013;3:5---19.

36.GolbinJM,SomersVK, CaplesSM.Obstructivesleepapnea, cardiovasculardisease,andpulmonaryhypertension.ProcAm ThoracSoc.2008;5:200---6.

37.EngstromG,MelanderO,HedbladB.Population-basedstudyof lungfunctionandincidenceofheartfailurehospitalisations. Thorax.2010;65:633---8.

38.GeorgiopoulouVV,KalogeropoulosAP,Psaty BM,RodondiN, BauerDC,ButlerAB,etal.Lungfunction andriskforheart failureamongolderadults:theHealthABCStudy.AmJMed. 2011;124:334---41.

39.AgarwalSK,Heiss G, BarrRG, Chang PP,Loehr LR, Chamb-lessLE,etal.Airflowobstruction,lungfunction,andriskof incidentheartfailure:theAtherosclerosisRiskinCommunities (ARIC)study.EurJHeartFail.2012;14:414---22.

40.CutticaMJ,ColangeloLA,ShahSJ,LimaJ,KishiS,Arynchyn A,etal.LossofLungHealthfromYoungAdulthoodand Car-diacPhenotypesin MiddleAge.Am JRespirCrit CareMed. 2015;192:76---85.

41.Barr RG, Bluemke DA, Ahmed FS, Carr JJ, Enright PL, Hoffman EA, et al. Percent emphysema, airflow obstruc-tion, and impaired left ventricular filling. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:217---27.

42.WatzH,WaschkiB,MeyerT,KretschmarG,KirstenA,Claussen M, et al. Decreasing cardiac chamber sizes and associated heart dysfunction in COPD: role of hyperinflation. Chest. 2010;138:32---8.

43.ChoudhuryG,MacNeeW.RoleofInflammationandOxidative StressinthePathologyofAgeinginCOPD:Potential Therapeu-ticInterventions.COPD.2017;14:122---35.

44.AgustiA, EdwardsLD, RennardSI, MacNeeW, Tal-Singer R, MillerBE,etal.Persistentsystemicinflammationisassociated withpoorclinicaloutcomesinCOPD:anovelphenotype.PLoS One.2012;7:e37483.

45.Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, Woods R, Elliott WM, Buzatu L, et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2645---53.

46.Cosio MG, Saetta M, Agusti A. Immunologic aspects of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2445---54.

47.LeeSH,GoswamiS,Grudo A, SongLZ,BandiV, Goodnight-WhiteS,etal.Antielastinautoimmunityintobacco smoking-inducedemphysema.NatMed.2007;13:567---9.

48.Agusti A, MacNee W, Donaldson K, Cosio M. Hypothe-sis: does COPD have an autoimmune component? Thorax. 2003;58:832---4.

49.HiltyM,BurkeC,PedroH,CardenasP,BushA,BossleyC,etal. Disorderedmicrobialcommunitiesinasthmaticairways.PLoS One.2010;5:e8578.

50.Erb-Downward JR, Thompson DL, Han MK, Freeman CM, McCloskeyL,SchmidtLA, etal. Analysisofthelung micro-biome in the ‘‘healthy’’ smoker and in COPD. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16384.

51.SzeMA,DimitriuPA,SuzukiM,McDonoughJE,CampbellJD, BrothersJF,etal.HostResponsetotheLungMicrobiomein ChronicObstructivePulmonaryDisease.AmJRespirCritCare Med.2015;192:438---45.

52.MoghaddamSJ,ClementCG,DelaGarzaMM,ZouX,Travis EL,YoungHW,etal. Haemophilusinfluenzaelysateinduces aspectsofthechronicobstructivepulmonarydisease pheno-type.AmJRespirCellMolBiol.2008;38:629---38.

53.AnthonisenNR.Bacteriaandexacerbationsofchronic obstruc-tivepulmonarydisease.NEnglJMed.2002;347:526---7. 54.KingPT,LimS,PickA,NguiJ,ProdanovicZ,DowneyW,etal.

Lung T-cell responses to nontypeable Haemophilus influen-zaeinpatientswithchronicobstructive pulmonarydisease. JAllergyClinImmunol.2013;131:1314---21,e14.

55.Thomsen M, Ingebrigtsen TS, Marott JL, Dahl M, Lange P, Vestbo J,etal.Inflammatory biomarkersandexacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Jama. 2013;309: 2353---61.

56.deMiguelDiezJ,ChancafeMorganJ,JimenezGarciaR.The associationbetweenCOPDandheartfailurerisk:areview.Int JChronObstructPulmonDis.2013;8:305---12.

57.GhoorahK,DeSoyzaA,KunadianV.Increasedcardiovascular riskinpatientswithchronicobstructivepulmonarydiseaseand thepotentialmechanismslinkingthetwoconditions:areview. CardiolRev.2013;21:196---202.

58.DuvoixA,DickensJ,HaqI,ManninoD,MillerB,Tal-SingerR, etal.Bloodfibrinogenasabiomarkerofchronicobstructive pulmonarydisease.Thorax.2013;68:670---6.

59.Mannino DM, Ford ES,Redd SC. Obstructive and restrictive lung disease and markers of inflammation: data from the ThirdNationalHealthandNutritionExamination.AmJMed. 2003;114:758---62.

60.KesslerR,PartridgeMR,MiravitllesM,CazzolaM,Vogelmeier C, Leynaud D, et al. Symptom variability in patients with severeCOPD:apan-Europeancross-sectionalstudy.EurRespir J.2011;37:264---72.

61.CazzolaM,RoglianiP,MateraMG.Cardiovascular diseasein patientswithCOPD.LancetRespirMed.2015;3:593---5. 62.Luis Puente-Maestu LAÁ-S, Javier de Miguel-Díez.

Beta-blockers in patients with chronic obstructive disease and coexistent cardiac illnesses. COPD Research and Practice. 2015:1.

63.BrekkePH,OmlandT,HolmedalSH,SmithP,SoysethV. Deter-minantsofcardiactroponinTelevationinCOPDexacerbation -across-sectionalstudy.BMCPulmMed.2009;9:35.

64.Brekke PH, Omland T, Holmedal SH, Smith P, Soyseth V. Troponin T elevationand long-termmortalityafter chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:563---70.

65.Baillard C,Boussarsar M,Fosse JP, Girou E,LeToumelin P, CraccoC,etal.CardiactroponinIinpatientswithsevere exac-erbationofchronicobstructivepulmonarydisease.Intensive CareMed.2003;29:584---9.

66.Brodde OE. Beta1- and beta2-adrenoceptor polymorphisms and cardiovascular diseases. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2008;22:107---25.

67.WashkoGR.TheroleandpotentialofimaginginCOPD.Med ClinNorthAm.2012;96:729---43.

68.CampoG,PavasiniR,BiscagliaS,ContoliM,CeconiC.Overview of the pharmacological challenges facing physicians in the managementofpatientswithconcomitantcardiovascular dis-easeandchronicobstructivepulmonarydisease.EurHeartJ CardiovascPharmacother.2015;1:205---11.

69.WangRT,LiJY,CaoZG,LiY.Meanplateletvolumeisdecreased duringanacuteexacerbationofchronicobstructivepulmonary disease.Respirology.2013;18:1244---8.

70.HarrisonMT,ShortP,WilliamsonPA,SinganayagamA,Chalmers JD,SchembriS.Thrombocytosisisassociatedwithincreased shortand longtermmortalityafterexacerbationofchronic obstructivepulmonarydisease:aroleforantiplatelettherapy? Thorax.2014;69:609---15.

71.Campo G, Pavasini R, Pollina A, Tebaldi M, Ferrari R. On-treatment platelet reactivity in patients with chronic obstructivepulmonarydiseaseundergoingpercutaneous coro-naryintervention.Thorax.2014;69:80---1.

72.HowardML,VincentAH.StatinEffectsonExacerbationRates, Mortality,andInflammatoryMarkersinPatientswithChronic ObstructivePulmonaryDisease:AReviewofProspective Stud-ies.Pharmacotherapy.2016;36:536---47.

73.LahousseL,VernooijMW,DarweeshSK,AkoudadS,LothDW, Joos GF, et al. Chronicobstructive pulmonary disease and

cerebralmicrobleeds.TheRotterdamStudy.AmJRespirCrit CareMed.2013;188:783---8.

74.HuangKW,LuoJC,LeuHB,LinHC,LeeFY,ChanWL,etal. Chronicobstructive pulmonarydisease: anindependentrisk factor for peptic ulcer bleeding: a nationwide population-basedstudy.AlimentPharmacolTher.2012;35:796---802. 75.Huang B, Yang Y, Zhu J, Liang Y, Zhang H, Tian L, et al.

Clinicalcharacteristicsandprognosticsignificanceofchronic obstructive pulmonary disease in patientswithatrial fibril-lation: results from a multicenteratrial fibrillation registry study.JAmMedDirAssoc.2014;15:576---81.

76.GoodmanSG,WojdylaDM,PicciniJP,WhiteHD,PaoliniJF, Nes-selCC,etal.Factorsassociatedwithmajorbleedingevents: insightsfromtheROCKETAFtrial(rivaroxabanonce-dailyoral direct factor Xainhibition compared withvitamin K antag-onism for prevention ofstroke and embolism trialinatrial fibrillation).JAmCollCardiol.2014;63:891---900.

77.BarnesPJ.Chronicobstructive pulmonarydisease. NEngl J Med.2000;343:269---80.

78.PetersenH,SoodA,MeekPM,ShenX,ChengY,BelinskySA, etal.Rapidlungfunctiondeclineinsmokersisariskfactor forCOPDandisattenuatedbyangiotensin-convertingenzyme inhibitoruse.Chest.2014;145:695---703.

79.Lopez-Campos JL, Marquez-Martin E, Casanova C. Beta-blockers and COPD: the show must go on. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:600---3.

80.Baker JG, Wilcox RG. beta-Blockers, heart disease and COPD: current controversies and uncertainties. Thorax. 2017;72:271---6.

81.LeeDS, MarkwardtS,McAvayGJ,GrossCP,GoeresLM,Han L, et al. Effect of beta-blockerson cardiac and pulmonary eventsanddeathinolderadultswithcardiovasculardisease andchronicobstructivepulmonarydisease.MedCare.2014;52 Suppl3:S45---51.

82.Celli B,Decramer M,KestenS, LiuD,Mehra S, TashkinDP. Mortalityinthe4-yeartrialoftiotropium(UPLIFT)inpatients withchronicobstructivepulmonarydisease.AmJRespirCrit CareMed.2009;180:948---55.

83.WiseRA,AnzuetoA,CottonD,DahlR,DevinsT,DisseB,etal. TiotropiumRespimatinhalerandtheriskofdeathinCOPD.N EnglJMed.2013;369:1491---501.

84.GershonA,CroxfordR,CalzavaraA,ToT,StanbrookMB,Upshur R, et al. Cardiovascular safetyofinhaled long-acting bron-chodilatorsinindividualswithchronicobstructivepulmonary disease.JAMAInternMed.2013;173:1175---85.

85.Ferreira AJ, ReisA, Marcal N, PintoP, BarbaraC.COPD:A stepwise or a hithardapproach? RevPortPneumol (2006). 2016;22:214---21.

86.Ferreira J, DrummondM, PiresN, ReisG, Alves C, Robalo-Cordeiro C. Optimal treatment sequence in COPD: Can a consensusbefound?RevPortPneumol(2006).2016;22:39---49. 87.XiaN,WangH,NieX.InhaledLong-Actingbeta2-AgonistsDo NotIncreaseFatalCardiovascularAdverseEventsinCOPD:A Meta-Analysis.PLoSOne.2015;10:e0137904.

88.Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, Ferguson GT, Jenk-ins C, Jones PW, et al. Cardiovascular events in patients with COPD: TORCH study results. Thorax. 2010;65: 719---25.

89.Rodrigo GJ, Plaza V. Efficacy and safety of a fixed-dose combination of indacaterol and Glycopyrronium for the treatment of COPD:a systematic review. Chest. 2014;146: 309---17.

90.Van de Maele B, Fabbri LM, Martin C, Horton R, Dolker M,OverendT. CardiovascularsafetyofQVA149, a combina-tion of Indacaterol and NVA237, in COPD patients. COPD. 2010;7:418---27.

91.Wedzicha JA, DahlR, Buhl R, Schubert-Tennigkeit A, Chen H, D’Andrea P, et al. Pooled safety analysis of the fixed-dosecombinationofindacaterolandglycopyrronium(QVA149), itsmonocomponents,andtiotropiumversusplaceboinCOPD patients.RespirMed.2014;108:1498---507.

92.HohlfeldJM,Vogel-ClaussenJ,BillerH,BerlinerD, Berschnei-der K, Tillmann HC, et al. Effect of lung deflation with indacaterol plus glycopyrronium on ventricular filling in patientswithhyperinflationandCOPD(CLAIM):adouble-blind, randomised,crossover,placebo-controlled,single-centretrial. LancetRespirMed.2018[Epubaheadofprint].

93.GlobalInitiativeforAsthma.GlobalStrategyforAsthma Mana-gementandPrevention(2017update).In.2017.

94.FerriC.Strategiesforreducingtheriskofcardiovascular dis-easeinpatientswithchronicobstructivepulmonarydisease. HighBloodPressCardiovascPrev.2015;22:103---11.

95.D’UrzoAD,KerwinEM,ChapmanKR,DecramerM,DiGiovanni R, D’Andrea P, et al. Safety of inhaled glycopyrronium in patientswithCOPD:acomprehensiveanalysisofclinical stud-iesandpost-marketingdata.IntJChronObstructPulmonDis. 2015;10:1599---612.

96.Barnes PJ. Theophylline. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2010;3:725---47.

97.CazzolaM,CalzettaL,BettoncelliG,CricelliC,RomeoF, Mat-era MG,et al.Cardiovascular diseaseinasthmaand COPD: apopulation-basedretrospectivecross-sectionalstudy.Respir Med.2012;106:249---56.

98.deBarroseSilvaPG,CaliffRM,SunJL,McMurrayJJ,Holman R,HaffnerS,etal.Chronicobstructivepulmonarydiseaseand cardiovascularrisk:insights fromtheNAVIGATORtrial.IntJ Cardiol.2014;176:1126---8.

99.Corlateanu A, Covantev S, Mathioudakis AG, Botnaru V, Siafakas N. Prevalence and burden of comorbidities in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Respir Investig. 2016;54:387---96.

100.McGarveyLP,MagderS,BurkhartD,KestenS,LiuD,ManuelRC, etal.Cause-specificmortalityadjudicationintheUPLIFT(R) COPD trial: findings and recommendations. Respir Med. 2012;106:515---21.

101.AgarwalS,RokadiaH,SennT,MenonV.Burdenof cardiovas-culardiseaseinchronicobstructivepulmonarydisease.AmJ PrevMed.2014;47:105---14.