ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.630432

The Internationalization of Business Administration

Undergraduate Courses in Brazil

Gilberto Sarfati, Tales Andreassi, and Maria Tereza Leme Fleury

Fundac¸˜ao Get´ulio Vargas, Escola de Administrac¸˜ao de Empresas de S˜ao Paulo, S˜ao Paulo, Brazil

The authors discuss the level of internationalization of business administration undergraduate courses in Brazilian schools based on a survey of 39 institutions affiliated with the National Association of Graduation in Administration and in a second survey among 19 professors from different institutions and 45 students from 21 schools. It was concluded that the international-ization of courses analyzed in the survey is limited to the participation of students in foreign exchange programs. Students and faculty believe that it should be introduced more classes in the international business field as well as classes in English. The authors compare the national results with 3 similar surveys, 1 conducted in the United States and in Europe by the Academy of International Business, and two others conducted in Arab and Latin American countries.

Keywords: curriculum, education, internationalization

The internationalization of business schools is an important factor in the education of professionals who must be capable of dealing with the obstacles and opportunities created by the globalization of businesses.

This research focuses on the internationalization of the business administration undergraduate course curriculums in the top-tier Brazilian business schools by surveying course coordinators in these schools. The survey is based on similar research conducted by the Academy of International Busi-ness (AIB) in 1969. Its most recent edition, the sixth, was conducted in 2000 (Kwok & Arpan, 2002).

The main issues addressed in the survey are (a) What is the level of internationalization stated in the business schools’ objectives?; (b) How are the institutions incorporating inter-nationalization into their organizations?; (c) What is the level of internationalization of undergraduate Business Adminis-tration curricula?; and (d) What is the level of international-ization of faculty and alumni?

The observed results are compared to those of the AIB research (Kwok & Arpan, 2002) and, to a smaller degree, to similar research conducted in Arab countries (Ahmed, 2006) and in Latin America (Elahee & Norbis, 2008).

Correspondence should be addressed to Gilberto Sarfati, Fundac¸˜ao Get´ulio Vargas, Escola de Administrac¸˜ao de Empresas de S˜ao Paulo, De-partment of Management and HR, Rua Itapeva 474, 11th Floor, S˜ao Paulo 01332–000, Brazil. E-mail: gilberto.sarfati@fgv.br

We initially discusse internationalization in higher edu-cation. Next, we analyze the internationalization of Busi-ness Administration schools in particular. A discussion of the methodology of the survey conducted at 39 Brazilian Administration schools and in a second survey among 19 professors from different institutions and 45 students from 21 schools follows. Next, the results of the research are pre-sented and discussed. Finally, the conclusions and further considerations are presented.

THEORETICAL CONSTRUCT The Internationalization of Higher Education

The globalization process has been driving not only the inter-nationalization of companies, but also the internationaliza-tion of educainternationaliza-tion in instituinternationaliza-tions of higher learning. The inter-nationalization of education was defined by Knight (2003) as the process of integrating international, intercultural or global dimensions in the aims, functions, and offerings of institutes of higher education.

Knight (2003) acknowledged that the primary dimensions of internationalization are apparent in (a) the mobility of people (the movement of professors and students to countries abroad), (b) the mobility of programs (the existence of an educational program abroad), and (c) mobility of institutions or suppliers (the existence of or investment in an institution or supplier abroad).

It is worth mentioning that although technology democra-tizes access to information, the internationalization process is broadly inequitable because institutions from the Northern Hemisphere are still the primary educational and academic centers of the world (Altbach, 2004). Because of this inequity, each country has been developing internationalization in ed-ucation in a distinct way.

According to Maranh˜ao and Lima (2009), education in Latin America is not very internationalized because univer-sities in that region receive very few students from North America, Europe, or Asia. In addition, their educational sys-tems have little global visibility. For researchers, the inter-nationalization of their curriculum has reinforced the educa-tional model predicted by hegemonic countries, establishing their curriculums as a tool of the cultural industry instead of an example of diversity.

The Internationalization of the Business

Administration Curriculum in Different Countries Since 1969, the AIB has been promoting the investigation of curricular internationalization in business schools, with a special focus on the United States and European countries. The most recent edition of the survey was conducted in 2000 (Kwok & Arpan, 2002).

Of the 1,139 institutions surveyed, only 151 responded. Of the 151 institutions that responded, 102 were American institutions, 29 were European institutions, and 20 were in-stitutions from other regions. Although the authors noted an increased desire for internationalization as compared to the results of the 1992 survey, only a small number of surveyed schools mentioned being “very satisfied” with the degree of internationalization of their program. That is, business had globalized much more rapidly than business administration schools had adapted, even in the United States.

Ahmed (2006) conducted a similar survey of 110 busi-ness schools in Arab countries, obtaining responses from 39 institutions spread throughout Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt, countries in the Persian Gulf, Sudan, Syria, Algeria, Libya, Iraq, and Yemen. Twenty-two of the 39 institutions sur-veyed were in Lebanon, Jordan, and Egypt. This survey showed that the vast majority of surveyed institutions have specialized courses in international business, but the lack of courses in Arabic and of specialized staff are not men-tioned as the primary obstacles to internationalization in this region.

In a recent survey (Elahee & Norbis, 2008) about the internationalization of business schools in Latin America, questionnaires were sent to 69 schools associated with the Latin American Council of Business Schools (CLADEA). Twenty-one institutions responded to the survey (only one of them was from Brazil). This research reveals that the sur-veyed institutions exhibited a considerable level of interna-tionalization, with specific subjects in international business and specialized faculty and exchange programs for

profes-sors and students. The extremely positive results may have been influenced by the low number of responses, which may have only represented the top business schools in the region.

METHOD

This survey focuses only on undergraduate courses in busi-ness administration. In this sense, the survey was more re-stricted than the AIB surveys, which focus on master’s and doctoral programs. According to the National Institute of Studies and Educational Researches (INEP), there are 3,481 institutions with undergraduate programs in business admin-istration authorized by the Ministry of Education (MEC). However, the sample chosen was 65 schools with under-graduate programs affiliated with the National Association of Graduation in Administration (ANPAD).

The 65 schools affiliated with ANPAD were chosen be-cause they are considered to be top-tier schools, including faculties that are dedicated to research. As such, it is be-lieved that schools with internationalization initiatives will be highly concentrated in this group of schools. The choice to use these schools was necessary to ensure the relevance of the survey.

The questionnaires were sent to undergraduate business administration course coordinators via e-mail, with the op-tion to answer the quesop-tions in an attached Word file or through a link to the site (http://www.freeonlinesurveys. com). In Brazil, coordinators are the most appropriate per-son to provide institutional answers related to undergraduate courses because many institutions do not have business ad-ministration deans. In many cases coordinators submitted part of questions to other departments (e.g., university inter-national relations office) before provding us the answers.

The requests were sent for the first time in March 2009 and follow-up telephone calls were made afterward. This proce-dure was repeated eight times until July 2009. There were 39 total responses, which represents 60% of the sample. This response rate was significantly higher than the previous Latin American survey, which had a sample of 69 institutions and a response rate of 31% (Elahee & Norbis, 2008); the survey of Arab countries, which had 110 schools and a response rate of 35% (Ahmed, 2006); and the last AIB survey, which had 1,139 schools and a response rate of 13% (Kwok & Arpan, 2002).

To ensure the comparability of the results, the 27 ques-tions used in this survey were based on the last AIB question-naire (Kwok & Arpan, 2002). The survey was divided into six parts: internationalization of the school mission, organi-zational internationalization, internationalization of the cur-riculum, school departments, best internationalization prac-tices adopted by the school, and institutional information such as the size of the institution and the public or private character of the institution.

A second round of this survey was conducted between May and June 2011. At this time we asked other stakehold-ers, students, and professors about their opinion about the re-sults from the first round. About 19 professors from different institutions and 45 students from 21 schools have answered the questions.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION Internationalization of the Mission

The majority of schools (95%) have a mission statement; however, only 6 (16%) mentioned international business in their mission statements. This percentage is considerably lower than the 87.7% from the AIB survey (Kwok & Arpan, 2002) and the 68% from the surveyed Arab schools (Ahmed, 2006). Only 51.3% of the institutions had developed a strate-gic plan in the last five years to incorporate specific objectives connected to international business, as opposed to 76.8% in the AIB study (Kwok & Arpan, 2002).

The results show that Brazilian schools have not incorpo-rated international business as part of their primary objec-tives, at least not to the same standards of the institutions surveyed by AIB. However, there is progress in the form of infusion of international dimensions into institutions’ mis-sion statements. Many institutions’ long-term plans include the growth of an international network of partner schools with the goal of increasing faculty and alumni exchange pro-grams. Although this mention is not enough to reflect the effective inclusion of international business into the insti-tution’s mission statement, it at least indicates a desire for greater international exposure.

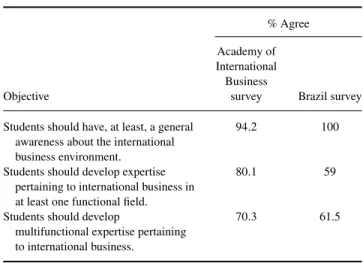

Table 1 reveals that all of the Brazilian coordinators con-sider it important to have a broad awareness of the inter-national business environment. However, as opposed to the AIB survey, only 59% of the Brazilian coordinators believe that it is necessary for students to develop an expertise in international business.

Such data reveal that the need for the globalization of students is somewhat disconnected from the development of specific knowledge about international business. This obser-vation is confirmed by the comparison to the results of the AIB survey, which indicate that 80.1% of the surveyed sub-jects consider the development of knowledge on international business to be a fundamental requirement.

Internationalization and Organizational Structure A total of 46.2% of the surveyed Brazilian schools and 58% of the institutions surveyed in the AIB study have a person or a group of people responsible for the internationalization of its curriculum. In addition, 82.1% of surveyed Brazilian schools and 69% of the schools surveyed in the AIB study have a person responsible for the administration of interna-tional activities, and 34.2% of the institutions surveyed in

TABLE 1

Objectives of Undergraduate International Business Administration Programs % Agree Objective Academy of International Business

survey Brazil survey Students should have, at least, a general

awareness about the international business environment.

94.2 100

Students should develop expertise pertaining to international business in at least one functional field.

80.1 59

Students should develop

multifunctional expertise pertaining to international business.

70.3 61.5

Note. Data are from Kwok and Arpan (2002) and survey data.

the Brazilian study and 36% of those surveyed in the AIB study said they had plans to develop departments related to international business (Kwok & Arpan, 2002).

These findings demonstrate that the most striking aspect of the internationalization of Brazilian schools has been the structuring of agreements with schools abroad, which seems to occur in a less focused manner than in North American schools. Some Brazilian schools have directed their efforts towards the internationalization of their curriculum, but to a lesser degree than foreign institutions. It is quite encour-aging that one third of the Brazilian schools surveyed are developing efforts to create study groups, departments and even master’s degree courses in international business. Internationalization of the Curriculum

It is not an easy task to compare the internationalization of the curriculum in various surveys, as some countries, such as Brazil and others in Latin America, treat international business in a broad manner, offering elective disciplines and specialization courses. In the United States, Europe, and Arab countries, it is more common to have a system that offers majors and minors.

Table 2 compares the results of surveys of international-ized curriculums from AIB surveys (Kwok & Arpan, 2002), a survey of Arab countries (Ahmed, 2006), surveys in Latin America countries (Elahee & Norbis, 2008), and the Brazil-ian survey.

In the Brazilian survey, 24 private institutions and 15 pub-lic institutions were surveyed. The range of international business course offerings is greater in public institutions than in private ones. However, offerings of specializations in international business among private institutions are more similar to international programs than those of public in-stitutions. Public institutions rely heavily on international

TABLE 2

Comparison of Internationalization of Curriculums in International Surveys

Kind of course offered AIB survey Arab Countries survey Latin America survey Brazilian survey Brazil public institutions Brazil private institutions Core functional courses infused with international

baccalaureate content

86% 95% — 61% 79% 54%

Specific international business courses 88% 79% 50% 31% 21% 38%

Specialization in international business 24%∗ 36% 43% 20% 7% 29%

International training/exchange 25% — — 41% 50% 29%

Note. Data are from Kwok and Arpan (2002), Ahmed (2006), Elahee and Norbis (2008), and survey data. aThe 2000 survey did not include this question. The data refer to the 1993 survey.

exchange programs for their international business course content.

Internationalization of the Brazilian curriculum is consid-erably lower than that observed in surveys in other coun-tries. Even when considering only broad thematic offerings in course curriculums, the degree of internationalization was relatively low.

The offering of specific international business courses (e.g., introduction to international business and international marketing) is only present in 31% of the Brazilian schools, as compared with 88% of the schools in the United States and Europe. It is equally inferior to the results observed in the Arab countries and in other Latin American countries.

To a certain extent, these data are paradoxical. On one hand, coordinators consider it important to be aware of the international business environment. On the other hand, these coordinators confirm that the curriculums of their courses only contain a few topics geared towards preparing students to understand the challenges of international business.

Of the eight Brazilian institutions that indicated that they offered a specialization (a group of courses in a single dis-cipline that normally grants a title on the undergraduate diploma) in international business, two did not have any pre-requisite requirements and five required a certification of proficiency in a foreign language (usually English). It can be concluded that only a few schools offer international busi-ness content in foreign languages, indicating a very small incidence of international experience including that shared with exchange students.

Some schools try to compensate for this drawback by of-fering alternatives for their students to receive this experience through training and exchange programs abroad. Therefore, it seems that the perception is that international knowledge should be obtained mainly in a foreign context. Although experience in schools abroad is an interesting aspect of the internationalization of business administration education, a majority of international institutions offer courses that pre-pare students for operating in the international economy from within their own country.

According to Table 3, less than one third of the Brazil-ian schools surveyed offer a course serving as an

introduc-tion to internaintroduc-tional business, followed by courses in in-ternational marketing and inin-ternational management. In the United States and Europe, most institutions offer courses concerning international business, specifically courses in in-ternational marketing and finance.

Most coordinators of business administration courses in the sample estimated that between 1% and 5% of their stu-dents take part in exchange programs abroad. Only three of the sampled schools indicated that more than 10% of their students take part in programs abroad. The data demonstrate that although the schools are making an effort to build in-ternational agreements, there are still very few students that are motivated or that can afford to spend even one semester abroad.

Concerning the level of satisfaction with the degree of internationalization of the curriculum, none of the coordina-tors in the Brazilian survey indicated that they were “very satisfied,” and only 8.5% answered “satisfied.” These num-bers should be compared to the 33% in the AIB survey who indicated that they were “very satisfied” and the 77% who indicated that they were “satisfied” (Kwok & Arpan, 2002).

On a Likert scale in which 1 indicates “not satisfied at all” and 5 indicates “very satisfied”, the average Brazilian answer was 2.31, compared to 3.21 in the AIB survey. The

TABLE 3

Comparison of the Offerings of International Business Courses in the Academy of International Business and

Brazilian Surveys Course Academy of International Business survey (%) Brazil survey (%) Introduction to International Business 62.8 31

International Marketing 82.6 28.2

International Finance 81 23.07

International Management 70.2 28.2

International Strategy 38 17.95

International Production 10.7 5.13

data indicates that Brazilian school coordinators acknowl-edge that the degree of internationalization of the curriculum is considerably below expectation.

Internationalization of School Departments

The coordinators were questioned about which activities they considered essential for the internationalization of the pro-fessors at their institution. Using a 5-point Likert-type scale with responses ranging from 1 (not very important) to 5 (very important), the average scores were higher than those obtained in the AIB survey. It is worth observing that the most importance was attributed to international surveys, fol-lowed by self-direction and trips abroad. In the AIB sur-vey, the most importance was attributed to trips abroad, at a level very close to the Brazilian result, followed by teach-ing and livteach-ing abroad and self-direction (Kwok & Arpan, 2002).

Curiously, in the Brazilian case, teaching or living abroad is above only consulting and other nonacademic activities. The Brazilian tradition of receiving and sending professors abroad influences this perception.

Importantly, the Brazilian survey indicates that the coor-dinators consider academic experience with specialization in business very important, especially when the experience is obtained abroad (i.e., there is a stronger acknowledgement of the value of obtaining academic knowledge abroad as op-posed to obtaining professional experience abroad). This is contrary to what was found in the AIB survey (Kwok & Arpan, 2002; see Table 4).

TABLE 4

Comparison of Means of Internationalization of Professors in the Academy of International Business

Survey and the Brazil Survey

Internationalization means for professors Academy of International Business survey Brazil survey Trips abroad 4.03 4.05 Teaching/living abroad 3.86 3.56 International survey 3.49 4.23 Academic education 3.69 3.95 Specialized international courses, specifically for doctorate degrees

2.93 3.79

Other training methods (e.g., seminars, conferences) 3.69 3.85 Consulting or other nonacademic activities 3.0 2.92

Personal initiative (e.g., reading, news)

3.75 4.10

Note. Data are from Kwok and Arpan (2002) and survey data.

About 77% of Brazilian coordinators indicated that there were not plans to develop international business research and teaching capacity. However, 79% of the Arab institutions (Ahmed, 2006) have plans to develop international business research and teaching programs. In the AIB survey (Kwok & Arpan, 2002), a third of the interviewees had plans to develop an international business area in their institutions.

The absence of plans to develop international business capacity is in contradiction with the importance given to the development of expertise in international business by the students who have been exposed to it.

About two-thirds of surveyed Brazilian institutions stated that they have exchange agreements with a number of insti-tutions abroad that enable their students to study abroad for a period of 1–2 school semesters. This is very significant, especially when compared with the AIB results, which indi-cate that 44% of North American institutions and 71.1% of the European institutions have this kind of agreement (Kwok & Arpan, 2002). The Latin American survey indicates that 86% of respondents have these types of exchange agreements (Elahee & Norbis, 2008).

However, only 23% of respondents indicated that their institution has faculty exchange agreements. This fraction is significantly lower than that of the AIB survey, which shows a very significant level of faculty exchange. Of the respon-dents, 58% stated that more than 25% of their professors have already taught abroad (Kwok & Arpan, 2002). In the Latin American survey, 76% of the respondents stated that they had exchange agreements for professors (Kwok & Arpan, 2002). In general, the schools indicate they are satisfied with their international partnerships. About 60% of the Brazilian respondents said they were satisfied compared with 62% from the AIB survey (Kwok & Arpan, 2002).

In a general evaluation of the internationalization progress in the last five years, 30% of Brazilian respondents said that they were satisfied compared with 77% of those surveyed in the AIB survey (Kwok & Arpan, 2002).

Stakeholders’ Perception About the Internationalization of Business Schools

Having the results from the first round we have asked student and professors opinions about the results from the first round. Table 5 shows students’ point of view.

Students’ answers reveal that they perceive the field of international business as very important for their education. Nevertheless, they attribute a higher importance to an in-ternational exchange experience in comparison to formal class knowledge in the field. Moreover, many students are satisfied exactly because their institutions offer exchange opportunities. Their perception is not a surprise because many universities in the last 15 years have engaged in an intensive effort to sign international exchange agreements. Institutions perceived these agreements as an important

TABLE 5

Students’ Opinions About the Internationalization of Business Administration Courses

Question Students’ answers

A Brazilian survey has shown that 31% of 39 schools affiliated with National Association of Graduation in Administration have specific courses in the field of international business (against 88% from U.S. and European institutions). Do you consider important to take courses in this field? Justify your answer.

100% answered yes. In direct or indirect way all said that it is important due to the impact of globalization. Nevertheless, many students recognized that their institution does not provide specific courses in the field.

In the schools surveyed, 66% of them have international agreements on exchange of students. Do you consider that the exchange experience is the most important activity that your institution can provide in terms of an internationalized education? Justify your answer.

90% answered yes and 10% no. Most students believe that having an international experience of living abroad and having contact with other cultures is the most important experience in terms of an internationalized education. Only 10% of them believe that courses in the field of international business are more relevant than an exchange experience.

Do you think it is important to take classes in English with exchange students from other countries and/or instructors from other countries? Justify your answer.

80% answered yes and 20% no. Those that answered yes believe that this is another opportunity to develop fluency in English and to learn from other cultures. Those that answered no understand that having a class in English may be an obstacle to learning process and there are other forms to lean about other cultures.

The survey revealed that 2.9% of institutions surveyed are dissatisfied with their level of internationalization, 11.8% somewhat satisfied, 35.3% are neutral, 44.1% are very satisfied, and 5.9% satisfied. How would you rate your satisfaction with the internationalization of your school? Explain.

56.8% answered dissatisfied, 31.8% satisfied, and 11.4% neutral. Those that were dissatisfied pointed out that their institution does not offer much in terms of internationalization or that international exchange opportunities are very limited. Those that were satisfied believe that their institution has a wide range of international partnerships and provide many opportunities to international contacts through classes and exchange program. Neutral answers reflect a perception of being a freshman and not knowing everything that its institution has to offer.

marketing tool. In the beginning this was a source of com-petitive advantage but today is perceived as something that any institution should have. Students that do not have many exchange opportunities tend to be more dissatisfied with the

level of internationalization of their institution in comparison to those from institutions that offer a wide range of exchange opportunities.

Although the first survey revealed that few institutions offer courses in English and with exchange students enrolled most of students perceive these classes as an important tool to internationalize their education. After the wave of exchange agreements probably the next wave will be to offer courses in English to improve the number of exchange students in Brazil. It is important to note that this step will face a language barrier both among professors and students.

Table 6 summarizes faculty perception about the level of internationalizations at their institutions.

Faculty answers provide important clues to understand why the field of international business is so underdeveloped in Brazilian business schools. Basically, Brazil is a late mover having few multinationals companies playing abroad.

Recently Fleury and Fleury (2011) pointed out that Brazil-ian economy was very close up to 1991 when newly em-powered government introduced major changes that exposed local companies to international competition. According to these authors, the internationalization of Brazilian enterprises from 1990s to the early 2000s concentrated on Mercosur (Mercado Comum del Sur, a regional trade agreement be-tween Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay), which ab-sorbed 36% of the country’s outward foreign direct invest-ment (OFDI) until 2002. Although Brazilian OFDI stock has rose from about US$ 41 billion in 1990 to 157.7 billion in 2009 it is far less than other developing countries such as China and Russia. Moreover, the Brazilian share in world trade is roughly about 1% and trade represents less than 20% of Brazilian gross domestic product (United Nations Confer-ence on Trade and Development, 2010).

Faculty tends to perceive that the business commu-nity is not demanding knowledge in international business. Therefore, there is low pressure for business schools to change their curriculum.

Brazil as a huge country with a very low exposition to international trade crafted a research tradition very much focused in local problems with low contact with international institutions. Therefore, for a long period foreign languages were not perceived as an asset. This is slowly changing while younger students and faculty improve their knowledge about other languages and cultures.

Contrary to students’ perceptions faculty do not tend to perceive exchange experience as the most important ex-perience for an internationalized education. Although it is an important experience few have the opportunity to go abroad. Moreover, they believe that formal knowledge in international business to all students it is important to in-ternationalize their education. This difference in perception was explained due to the market strategy of many insti-tutions that pictured exchange programs as a competitive advantage.

TABLE 6

Faculty Opinions About Internationalizations of Business Administration Courses

Questions Professors’ answers

A Brazilian survey has shown that 31% of 39 schools affiliated with National Association of Graduation in Administration have specific courses in the field of international business (against 88% from U.S. and European institutions). In your opinion why Brazilian business schools have a relatively low offering of courses in the international business field?

There are 4 main groups of answers in order of importance:

1. Late internationalization of Brazilian companies and still low level of internationalization of Brazilian economy resulted in low response from business schools.

2. Low level of relationship with business community and low demand from professionals with specific skills (in comparison to traditional areas such as marketing and finance).

3. Low level of connection with international research centers. 4. Low level of fluency on English by both students and professors. Do you consider important to your students to take classes in the field of

international business?

All professors consider important due to the globalization of economy. In the schools surveyed, 66% of them have international agreements on

exchange of students and 23% have international agreements on exchange of teachers. How do you explain the high mobility of students X the low mobility of faculty compared to international researches?

All professors revealed that institutional barriers hamper faculty mobility. Private and public institutions as well tend not to recognize the value of an international experience. By going abroad professors from private institutions perceive a threat to their jobs while from public institutions professors face institutional opposition with a very low perception of benefit to his or her career.

Do you consider that the international exchange of students enough to enable them to handle the international business environment?

100% of professors did not consider international exchange experience to be the most important activity to handle international business. All of them recognize as an important experience but they also consider important specific courses in the field of international business, to internationalize research and to improve relationship with the business community in order to have more students being interns abroad.

The survey revealed that 2.9% of institutions surveyed are dissatisfied with their level of internationalization, 11.8% somewhat satisfied, 35.3% are neutral, 44.1% are very satisfied, and 5.9% satisfied. How would you rate your satisfaction with the internationalization of your school? Explain.

Only 1 professor was totally dissatisfied because the school is not doing much in terms of internationalization. Professors recognized that their schools are making progress specially in terms of exchange agreements but the process is in the beginning and there is still much do be done in terms of faculty mobility and relationship with business community.

Despite the low level of internationalization of most Brazilian business schools most professors recognize that their institutions are taking the right steps but there is still much to be done specially in terms of faculty mobility and improving internationalization of research.

CONCLUSIONS AND FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

This survey of Brazilian business administration schools shows that the preferred method of internationalization has been restricted to student mobility, usually by creating part-nerships that will enable students to travel abroad. When evaluating international surveys, it is seems apparent that ex-change programs should be a two-way road and that Brazilian schools should increase their course availability, especially in English.

However, a course in the development of international business must naturally include commercial exchange with neighbors, so it would also make sense to forge partnership agreements with other countries in South America, imply-ing the development of course content in Spanish. Neverthe-less, institutions that have exchange agreements usually have partnerships with European schools and with North

Ameri-can ones, to a smaller degree. South AmeriAmeri-can schools are usually not mentioned as destinations for Brazilian students. This two-way road should also result in faculty mobility. There are very few Brazilian schools that receive foreign professors or encourage their professors to teach abroad. In fact, it seems that this kind of exchange program is not seen as very important to Brazilian coordinators, but they are extremely common among universities in the United States, Europe, and Asia.

It is also worth noting that there are only a few course offerings specific to international business in the undergrad-uate business administration curriculum. This is not for lack of student interest, but due to the lack of perceived value at the institutional level. It is clear that, to the schools, inter-nationalization means sending students abroad and not nec-essarily offering content in their home schools that would enable those students to deal with the dilemmas faced in the international business environment.

Students and professors as well believe that it is important to introduce classes in the international business fields. Nev-ertheless, most institutions have not yet caught up yet this trend. The late and relatively low level of internationaliza-tion of Brazilian economy explains why most top Brazilian business schools don’t have classes in the field and even less offer classes in English.

We conclude that the internationalization of undergradu-ate Brazilian business schools is limited to sending students abroad. This is a very basic kind of internationalization and is insufficient for students who will deal with Brazil’s increased presence in the international economy. The com-parative study reinforces the survey’s conclusions regarding the low degree of internationalization of undergraduate courses in business administration in Brazil. Stronger institutional commitments are necessary with regard to the investment of funds, the hiring of specialized staff, and the development of an internationalized curriculum and alumni exchange programs for Brazilian institutions to compete and develop the international capacities of future administration professionals.

Business administration schools that desire to increase their competitiveness and to ensure that their students are prepared to deal with current corporate challenges should first develop courses in specific areas of international business, such as marketing and international logistics.

The second step is to develop mobility programs for stu-dents and professors. As was observed previously, mobility is a two-way street in which Brazilian institutions offer courses in English and Spanish and try to attract exchange students not only from the United States and Europe but also and especially from neighboring countries such as Argentina, Uruguay, Colombia, Venezuela, and Chile.

The schools’ international relations departments should strengthen their relationships with foreign schools to en-courage the mobility of professors, in bringing foreign fac-ulty in to teach courses in Brazil and sending Brazilian faculty to other countries, especially other South Ameri-can countries. These concrete measures should contribute to

increased internationalization of Brazilian business schools to levels comparable to American and European business schools.

This research can be further improved with another sur-vey covering the opinion from the Brazilian business com-munity. At the same time it is important that Brazilian busi-ness schools foster internationalization among companies and improve their ties with young Brazilian multinational companies.

REFERENCES

Ahmed, A. A. (2006). The internationalization of the business administration curriculums in Arab Universities. Journal of Teaching in International Business, 18, 89–107.

Altbach, P. G. (2004). Globalization and the university: Myths and realities in an unequal world. Tertiary Education and Management, 10, 3–25. Elahee, M., & Norbis, M. (2008). Internationalizing business education:

Ev-idences from Latin America. New York, NY: Notheast Decision Sciences Institute.

Fleury, A., & Fleury, M. T. (2011). Brazilian multinationals: Competences for internationalization. London, England: Cambridge University Press. Knight, J. (2003). Updating the definition of internationalization.

Interna-tional Higher Education, 33, 2–3.

Kwok, C. C. Y., & Arpan, J. S. (2002). Internationalizing the business school: A global survey in 2000. Journal of International Business, 33, 571–581. Maranh˜ao, C. M. S. A., & Lima, M. C. (2009). Pol´ıticas curricu-lares da internationalizac¸˜ao do ensino superior: Multiculturalismo ou semiformac¸˜ao? [Curricula politics and internationalization of higher edu-cation: Multiculturalism or semiformation?] Presented at the 2009 Meet-ing of the National Association of Graduation in Administration, S˜ao Paulo, Brazil.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. (2010). World in-vestment report 2011. Geneva, Switzerland: Author.