AgeingResearchReviews35(2017)74–86

ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Ageing

Research

Reviews

j o ur na l h o me p a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / a r r

Pain

perception

in

Parkinson’s

disease:

A

systematic

review

and

meta-analysis

of

experimental

studies

Trevor

Thompson

a,∗,

Katy

Gallop

b,

Christoph

U.

Correll

c,d,

Andre

F.

Carvalho

e,

Nicola

Veronese

f,

Ellen

Wright

g,

Brendon

Stubbs

h,iaFacultyofEducationandHealth,UniversityofGreenwich,LondonSE92UG,UK bAcasterConsulting,LondonSE37HU,UK

cepartmentofPsychiatry,TheZuckerHillsideHospital,NorthwellHealth,GlenOaks,NY11004,USA

dDepartmentofPsychiatryandMolecularMedicine,HofstraNorthwellSchoolofMedicine,Hempstead,NY11549,USA

eDepartmentofClinicalMedicineandTranslationalPsychiatryResearchGroup,FacultyofMedicine,FederalUniversityofCeará,Fortaleza,CE,Brazil fInstituteforClinicalResearchandEducationinMedicine,I.R.E.M.,Padova,Italy

gDepartmentofPrimaryCareandPublicHealthSciences,King’sCollegeLondon,LondonSE13QD,UK hPhysiotherapyDepartment,SouthLondonandMaudsleyNHSFoundationTrust,LondonSE58AZ,UK iHealthServiceandPopulationResearchDepartment,King’sCollegeLondon,LondonSE58AF,UK

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received19December2016

Receivedinrevisedform25January2017 Accepted25January2017

Availableonline4February2017

Keywords:

Parkinson’sdisease Dopamine Pain Meta-analysis Systematicreview

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Whilehyperalgesia(increasedpainsensitivity)hasbeensuggestedtocontributetotheincreased

preva-lenceofclinicalpaininParkinson’sdisease(PD),experimentalresearchisequivocalandmechanisms

arepoorlyunderstood.Weconductedameta-analysisofstudiescomparingPDpatientstohealthy

con-trols(HCs)intheirresponsetoexperimentalpainstimuli.Articleswereacquiredthroughsystematic

searchesofmajordatabasesfrominceptionuntil10/2016.Twenty-sixstudiesmetinclusioncriteria,

comprising1292participants(PD=739,HCs=553).Randomeffectsmeta-analysisofstandardizedmean

differences(SMD)revealedlowerpainthreshold(indicatinghyperalgesia)inPDpatientsduring

unmedi-catedOFFstates(SMD=0.51)whichwasattenuatedduringdopamine-medicatedONstates(SMD=0.23),

butunaffectedbyage,PDdurationorPDseverity.Analysisof6studiesemployingsuprathreshold

stim-ulationparadigmsindicatedgreaterpaininPDpatients,justfailingtoreachsignificance(SMD=0.30,

p=0.06).Thesefindings(a)supporttheexistenceofhyperalgesiainPD,whichcouldcontributetothe

onset/intensityofclinicalpain,and(b)implicatedopaminedeficiencyasapotentialunderlying

mecha-nism,whichmaypresentopportunitiesforthedevelopmentofnovelanalgesicstrategies.

©2017ElsevierB.V.Allrightsreserved.

Contents

1. Introduction...75

2. Method...75

2.1. Eligibilitycriteria...76

2.2. Searchstrategy...76

2.3. Studyselection...76

2.4. Painoutcomevariables ... 76

2.5. Dataextraction...76

2.6. Studyvaliditycriteria...76

2.7. Statisticalanalysis...76

2.7.1. Effectsize...76

2.7.2. Meta-analysis...76

2.7.3. Meta-regressionanalyses...80

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:t.thompson@gre.ac.uk(T.Thompson).

T.Thompsonetal./AgeingResearchReviews35(2017)74–86 75

2.8. Publicationbias ... 80

3. Results ... 80

3.1. Studyselection...80

3.2. Participantcharacteristics ... 80

3.3. Studycharacteristics...80

3.4. Studyvaliditycriteria...81

3.5. Meta-analysisresults ... 81

3.5.1. Painthreshold...81

3.5.2. Suprathresholdpainresponse...83

3.5.3. Otheroutcomes:painratingsandsensorythreshold...83

3.6. Meta-regressionanalyses:painthreshold...83

3.6.1. PDseverity...83

3.6.2. Methodofassessment...83

3.6.3. Secondarymoderators...83

3.6.4. Studyvaliditycriteria...83

3.7. Repeated-measuresstudiescomparingONvs.OFFstates...83

4. Discussion...83

4.1. PainhypersensitivityinPDandclinicalimplications...84

4.2. Roleofdopamine...84

4.3. Partialpainthresholdnormalisation...84

4.4. Independenceofmotorimpairmentandpain...84

4.5. Limitations...85

4.6. Futureresearchdirections...85

4.7. Conclusions...85

Disclosures...85

Acknowledgements ... 85

AppendixA.Supplementarydata...85

References...85

1. Introduction

Chronic pain is a common non-motor symptom of Parkin-son’sdisease(PD).Arecentsystematicreviewindicatedamean painprevalenceof 68%inPDpatients(Broenetal.,2012), with anotherstudyfindingthatchronicpaincomplaints,especially mus-culoskeletalpain,weretwiceaslikelyand reportedastwiceas intensein PD patientscompared toage-matchedcontrols with other chronic disorders (Nègre-Pagès et al., 2008). Pain often appearsearlyinthedevelopmentofPDandmaybepresentyears beforeclinicaldiagnosis(Schragetal.,2015).Painhasbeenratedas themostburdensomenon-motorsymptom(ChaudhuriandOdin, 2010),andcontributestoPD-relateddisability,sleepdisturbance, and impairedquality oflife (Chaudhuriand Schapira, 2009;Fil etal.,2013;QuittenbaumandGrahn,2004).Non-motorsymptoms includingpainarealsoafrequentcauseofhospitalisationand insti-tutionalisationofPDpatientsandcanincreasehealthcarecostsby uptofourtimes(ChaudhuriandSchapira,2009).Nevertheless,pain isafrequentlyoverlookedsymptomofPD,oftenunreportedby patientsunawarethatpainfulsymptomsarelinkedtothedisease (Mitraetal.,2008),andconsequentlyunder-treated(Broenetal., 2012)whichcanincreasetheoverallburdenofPD.Thisisespecially unfortunategiventhatpainrepresentsanon-motorsymptomthat iseminentlytreatable(Chaudhurietal.,2010).

While pain in PD is often precipitated by muscular rigidity and/or postural abnormalities (Ford, 2010), neurodegenerative processes couldpotentially affect not only motor function, but alsoperipheral(Nolano etal., 2008)and brain(Filetal., 2013) pathwaysinvolvedinpainprocessing.Forexample,degradationof dopamine-producingcellsinthesubstantianigramayimpair nat-uralanalgesiabydisruptingthedopamine-mediateddescending pathwaysthatblocktransmissionofascendingnociceptivesignals fromthespinalcord(Filetal.,2013).Aroleofdopamineinpain isconsistentwithreducedpainsensitivityseeninschizophrenia (Stubbsetal.,2015),adisorderlinkedtodopaminedysregulation, andthepossiblepartialrestorationofnormalpainthresholdsinPD

duringfunctionalONstatesfollowingtreatmentwith dopaminer-gicagents(Curyetal.,2016).

IfpainprocessingisaffectedcentrallyinPD,ashypothesised, thiscouldresultinageneralisedhypersensitivitytonoxious sen-sations (Cury et al., 2016), which may influence the onset of and/orexacerbate painful symptomsin PD(Broenet al.,2012). Evidenceforthishypersensitivityis,however,inconsistent.While severalstudieshavefoundincreasedpainsensitivityinPDpatients comparedtohealthycontrols(HCs)inresponsetonoxious exper-imentalstimulation (Chen etal.,2015; Limet al.,2008; Mylius etal.,2009),othershavefailedtofindsuchaneffect(Granovsky etal.,2013;Massetanietal.,1989;Velaetal.,2007).This incon-sistencymaybeinfluencedbymethodologicaldifferencesacross studies,includingvariationinsamplesize,dopaminergicand anal-gesic medications, disease duration and symptom severity (Fil etal.,2013;Priebeetal.,2016).Nevertheless,toourknowledge, there hasbeennosystematic efforttosynthesizeavailable evi-dencefromexperimentalstudiesandtoexplorepotentialsources ofstudyheterogeneityusingmeta-analytictechniques.Examining theinfluenceofdopaminemedicationmaybeespeciallyrevealing, bothtoprovideevidenceforpossiblemechanismsofactionandfor informingpotentialanalgesictreatment.

Wethereforeconductedasystematicreviewandmeta-analysis ofstudiescomparingPDpatientsandHCsintheirresponseto nox-iousexperimentalstimulito:(1)examinewhetherPDpatientsand HCsdifferintheirresponsetoexperimentally-inducedpain;(2) quantifythemagnitudeofthisdifference;and(3)explore poten-tialmoderatorsofthisassociationincludingdopaminergicagents, diseaseduration,andsymptomseverity.

2. Method

76 T.Thompsonetal./AgeingResearchReviews35(2017)74–86

guidelines(Stroupetal.,2000)forobservationalstudies.Anapriori

establishedbutunpublishedprotocolwasfollowed.

2.1. Eligibilitycriteria

Thefollowinginclusioncriteriawereapplied:(1)useofagroup withprimary(idiopathic)Parkinson’sdisease(PD),basedon stan-dardizeddiagnosticcriteria(e.g.UKBrainBank);(2)inclusionof acomparativehealthycontrol(HC)groupwithoutPD;(3) appli-cationof anexperimentalpainstimulus;and (4)a quantitative assessmentofpain.Weexcludedstudiesusingparticipantswith secondaryParkinsonismonly(e.g.fromtoxinexposure)andthose publishedinlanguagesotherthanEnglish.

2.2. Searchstrategy

EMBASE,MEDLINEandPsycINFOdatabaseswereindependently searchedbytworeviewers(KG,TT)withthefinalsearchperformed on10th October 2016.The following search terms were used: (Parkinson’sdisease(MeSH)ORParkinson’s)AND(pain(MeSH)OR painORnociception)toidentifythelargestpossiblepoolof poten-tiallyeligiblestudies.Thesearchresultswereaposteriorirefined usinglimitsof‘humanstudies’and‘Englishlanguage’.Thissearch strategywasaugmentedthroughhandsearchingreferencelistsof includedarticlesandrelevantreviews.

2.3. Studyselection

After removal of duplicates, two reviewers (KG, TT) inde-pendently screened titles/abstracts for eligibility, and resolved disagreementsthroughconsensus.Thefull-textofpotentially eli-giblearticleswasthenindependentlyscrutinizedbytwoauthors (TT, BS).Followingconsensus,a full-list ofeligible articleswas defined.Whenastudyprovidedinsufficientdataforinclusion, cor-respondingauthorswerecontactedupto3timesoveran8-week periodtorequestadditionaldata.Of8authorgroupscontacted,6 (Aschermannetal.,2015;Granovskyetal.,2013;Haraetal.,2013; Nandhagopaletal.,2010;Nolanoetal.,2008;Takedaetal.,2013) provideddatasufficienttopermitstudyinclusion.

2.4. Painoutcomevariables

Thefollowingpainoutcomeswereused:(1)painthreshold(the pointatwhichpainisfirstreported),(2)paintolerance(thepoint atwhichpainisreportedasnolongertolerable),and(3)self-report ratingsofpainintensity/affect.Weusedthesemultipleoutcomes toassesswhetherdifferentaspectsofthepainexperiencewere selectivelyaffectedin PD.Thresholdinvolveslow-intensitypain andisinfluencedprimarilybysensoryprocesses(e.g.,localization andinitialdetection),whereastoleranceisasuprathreshold mea-suremorestronglyinfluencedbyaffectivemechanisms(Apkarian etal.,2005).Painratingscalesprovideaneasilyinterpretableindex ofsubjectivepainandtypicallyassesssensory(e.g.,intensity)or affective(e.g.,discomfort)dimensionsofpainonaVASornumerical ratingscale.

Sensorythreshold(thepointatwhichsensationisfirstreported) wasincludedasasecondarymeasuretoexaminewhetherPDwas alsoassociatedwithnon-painfulsensoryimpairment.Asweonly wishedtoexaminedirectmeasuresofpain,wedidnotexamine supplementaryphysiologicaldata.

2.5. Dataextraction

Extractionandcoding ofstudydatawereperformedby two authors(TT,KG),onastandardizedformadaptedfromourprevious

studies(Stubbsetal.,2015;Thompsonetal.,2016).The follow-ingdata wereextracted where available: (1)sociodemographic variables;(2)ForPDgroups:meandiseaseduration(years), symp-tom severityscore, functional state (ON/OFF), body side tested (least/mostaffected), diagnosticcriteria used, cognitive impair-ment,usualtreatment,%ofsamplewithPD-basedclinicalpain; (3)painoutcomesandpaininductionmethod.Meansand stan-dard deviationsfor each painoutcome wererecorded, andany otheravailableinformationthatallowedeffectsizecomputation (LipseyandWilson,2001).Toreducereportingbias,authorswere contactedforstatisticaldetailswhenfindingsweresimplyreported as‘non-significant’.

Anumberofdecisionsweremadewhencomputingeffectsizes from extracted data. First, a few studies (k=3) provided data frommultipleindependentparticipantsamples(Aschermannetal., 2015;Schestatskyetal.,2007;Velaetal.,2007),e.g.with/without dyskinesia,andweretreated asseparatestudiesin theanalysis (Borensteinetal.,2009).Second,foronestudythatusedawide rangeoftemperatures(Nandhagopaletal.,2010),onlythose elicit-ingaself-reportofpain(47.5◦Cand49.5◦C)wereincluded.Third,

forstudies(k=2)thatreportedtheuseofdifferentnoxious elec-tricalfrequencies(Aschermannetal.,2015;Chenetal.,2015),the lowestfrequencywasarbitrarilyselected,asthereappearstobe nopersuasiveevidenceforafrequencyeffect(Chenetal.,2015). Fourth,where studiesperformedrepeatedpainassessments on thesamesetofparticipants(e.g.acrossdifferentstimuli),multiple effectsizeswerecomputedforeachassessmentwithany depen-dencyacrosseffectsizesmodeledusingrobustvarianceestimation (RVE)(seeSection2.7.2).

2.6. Studyvaliditycriteria

Twoauthors(KG,TT)independentlyratedeachstudyonseveral dichotomousvaliditycriteria,withathirdauthor(BS)availablefor mediationintheeventofdisagreement.Weassessedcase/control comparability and participant selection with 5 items from the NewcastleOttawaScale(Wellsetal.,2008),andmethodological soundnesswith14itemsbasedonCochraneCollaboration prin-ciplesasreviewed byDeeks et al.(2003)(see Table1).Overall scoreswerenotcomputedduetoconcernsovertheir interpretabil-ity(Deeksetal.,2003),buttheimpactofpoorlyendorsedvalidity criteriawasexaminedinmoderatoranalysis.

2.7. Statisticalanalysis

2.7.1. Effectsize

Astandardizedmeandifference(SMD)forPDvs.controlgroups wascomputedforeachstudyusingHedges’gformula(Borenstein etal.,2009).Hedges’gisequivalenttoCohen’sd,butcorrectsfor biasinsmallsamples.Effectsizescanbeinterpretedas0.20,0.50 and0.80correspondingtosmall,mediumandlargeeffects respec-tively(Cohen,1988).

Effect size (ES) was coded so that positive values indicated higherpaininthePDcomparedtotheHCgroup.

2.7.2. Meta-analysis

T.

Thompson

et

al.

/

Ageing

Research

Reviews

35

(2017)

74–86

77

Table1

Summaryofincludedstudies.

Study N-PD Duration

years

UPDRS-III ON/OFFstate

duringpain testing

UsualMedication N-CON Modality TestingSite PainMeasure

Priebeetal.(2016) 23 8.1 18.4(OFF) OFF

ON

Mixed(L-DOPA=1;DA agonists=5; L-DOPA+DA agonists=17;MAO inhibitors=9;COMT inhibitors=2;NMDA blockers=5)

23 Heat

Electrical

Forearm Leg

Pain Threshold Pain Threshold (NFR) Pain Intensity EMG response

Myliusetal.(2016) 14 1.8 22.8(ON) OFF NSbutinc.L-DOPA 27 Heat

Electrical

Forearm Leg

Pain Threshold Pain Threshold (NFR)

Allenetal.(2016) 26 – 27.3b(ON) ON NS 11 Pressure(type

notstated)

UpperArmLeg PainThreshold

Aschermannetal. (2015)

6 6.20 11.2(ON) ON Mixed(levodopa,

dopamineagonists, MAOand COMT-inhibitors)

6 Heat Forearm PainThreshold(for

moderatepain) PainIntensity

Aschermannetal. (2015)

6 5.50 15.8(ON) ON Mixed(asabove) 6a Heat Forearm PainThreshold(for

moderatepain) PainIntensity Chenetal.(2015) 72 4.90 29.5(OFF)

23.1(ON)

OFF ON

L-DOPA 35 Electrical Hand Sensory

Threshold Pain Tolerance Grashornetal.(2015) 25 3.70 24.1(OFF)

20.7(ON)

OFF ON

Mixed(L-DOPA=4, L-DOPA+MAO inhibitors=2,L-DOPA+ DAagonists=1;DA agonists=7;DA agonists+MAO Inhibitors=9;MAO inhibitors=2)

30 Heat

Cold pressor

Forearm Leg

PainThreshold(for moderatepain) PainIntensity

Tanetal.(2015) 14 2.50 21.8(OFF) OFF None 17 Heat Forearm SensoryThreshold

PainThreshold Pain

Intensity

Takedaetal.(2014) 23 5.60 27.0(ON) ON Mixed(L-DOPA=4,

L-DOPA+DA agonists=11,MAO inhibitors=8)

12 Electrical Hand

Leg

78

T.

Thompson

et

al.

/

Ageing

Research

Reviews

35

(2017)

74–86

Table1(Continued)

Study N-PD Duration

years

UPDRS-III ON/OFFstate

duringpain testing

UsualMedication N-CON Modality TestingSite PainMeasure

Haraetal.(2013) 42 6.50 21.6(ON) ON Mixed(L-DOPA,DA

agonists,MAO inhibitors, catechol-Omethyl transferaseand amantadine)

17 Electrical Face PainThreshold

Granovskyetal.(2013) 23 6.30 23.6(ON) OFF ON

Mixed(L-DOPA=11, DAagonists=17,MAO inhibitors=19, Anticholinergics=8, Amantadine=14)

19 Heat

Pressure (vonFrey filaments)

Hand Forearm

Pain Threshold Pain Intensity

Velaetal.(2012) 18 11.60 34.5(OFF) 22.1(ON)

OFF ON

Mixed(L-DOPA,DA agonists)

18 Pressure

(algometer) Heat Cold

Neck Head Hand Leg

PainThreshold

CiampideAndrade etal.(2012)

25 15.10 42.7(OFF)

25.8(ON

-viaDBS)

OFF ON

L-DOPA 35 Heat

Cold Pressure (vonFrey filaments)

Hand Sensory

Threshold PainThreshold PainIntensity

Stamelouetal.(2012) 19 6.70 22.4(ON) OFF L-DOPA(nodetailson

othermedications)

17 Heat

Electrical

Forearm Leg

PainThreshold (NFR) PainThreshold

Myliusetal.(2011) 29 7.40 25.6(ON) OFF L-DOPA(nodetailson

othermedications)

27 Electrical

Heat

Forearm Leg

PainThreshold (NFR)

Maruoetal.(2011) 17 15.50 36.3(ON) ON L-DOPA,DAagonists

(nodetailsonother medications)

14 Cold

Heat

Hand Sensory

Threshold PainThreshold

Zambitoetal.(2011) 106 5.70 23.5(OFF) OFF Mixed(L-DOPA=38;

DAagonists=19; L-DOPA+DA agonists=49)

51 Electrical Hand

Foot

T.

Thompson

et

al.

/

Ageing

Research

Reviews

35

(2017)

74–86

79

Nandhagopaletal. (2010)

12 9.40 28.8(OFF)

15.0(ON)

OFF ON

Mixed(L-DOPA with/without other medica-tion=12)

13 Heat Forearm PainIntensity

Pain

Unpleasantness

Myliusetal.(2009) 15 11.00 28.3(OFF) OFF Mixed 18 Heat

Electrical

Forearm Leg

PainThreshold PainThreshold (NFR)

Nolanoetal.(2008) 18 7.60 26.6(ON) ON Mixed(L-DOPA

with/without other medica-tion=14, None=4)

54 Cold

Heat Pressure(nylon monofilament)

Hand Foot

SensoryThreshold PainThreshold

Limetal.(2008) 50 4.38 29.6(OFF) 21.3(ON)

OFF ON

L-DOPA(no detailsonother medications)

20 Coldpressor Hand PainThreshold

PainTolerance

Gerdelat-Masetal. (2007)

13 7.30 21.2(OFF)

10.8(ON)

OFF ON

Mixed(L-DOPA and/orDA agonists)

10 Electrical Leg PainThreshold

(NFR)

Schestatskyetal. (2007)

9 5.40 17.1(NS) OFF

ON

NSbutinc. L-DOPA

9 Heat

Laser

Hand SensoryThreshold

PainThreshold Schestatskyetal.

(2007)

9 6.00 19.1(NS) OFF

ON

NSbutinc. L-DOPA

9a Heat

Laser

Hand SensoryThreshold

PainThreshold

Velaetal.(2007) 25 11.38 24.6(ON) ON NS 25 Pressure

(algometer)

Hand PainThreshold

Velaetal.(2007) 25 4.72 19.9(ON) ON NS 25a Pressure

(algometer)

Hand PainThreshold

Brefel-Courbonetal. (2005)

9 9.60 25.0(OFF)

15.0(ON)

OFF ON

Mixed(L-DOPA and/orDA agonists)

9 Coldpressor Hand PainThreshold

Djaldettietal.(2004) 51 5.30 24.0(OFF) OFF Mixed(L-DOPA

and/orDA agonists)

28 Heat Hand PainThreshold

Massetanietal.(1989) 15 4.10 NA ON Mixed(L-DOPA

withor without peripheral decarboxylase inhibitor=10, drugfree=5)

8 Electrical Face SensoryThreshold

PainThreshold PainThreshold (blinkreflex)

TOTAL for26studies

739 M=7.10years ON:

M=22.2yrs OFF: M=27.0yrs

ON=19; OFF=18

L-DOPA with/without others=23 NotStated=2 None=1

553 Heat=16;

Electrical=1; Cold=7; Pressure=6; Laser=1

Hand=13; Forearm=10; Leg=10;Face=2; Foot=2; Neck/Head/Upper Arm=1

Pain Threshold=21; Sensory Threshold=9; Intensity=7; Suprathreshold (moderate pain/tolerance)=6; Unpleasantness=1

Key:NS=NotStated,NFR=NociceptiveFlexionReflex,DA=Dopamine,MAO=Monoamineoxidase,COMT=Catechol-O-methyltransferase,NMDA=N-methyl-d-aspartate. aSamecontrolgroupusedfor‘-a’and‘-b’studies.

80 T.Thompsonetal./AgeingResearchReviews35(2017)74–86

whichadjustsindividualESweightsbasedonthedegreeoftheir dependency.WeemployedarelativelynewversionofRVEfor cor-relatedeffectsizes,whichprovidesreliableestimatesevenwhen relativelylownumbersofstudiesareavailable.Simulationstudies havedemonstratedaccurateestimation,providedthattheadjusted RVEdegreesof freedom(df)>4(Tipton,2015),and this criterion isusedhere(dfislargerwhen studynumber ishighand when multipleeffectsizesfromastudyarerelativelyindependent).RVE estimatesdependencyfromthedataitself,andthereforeisa supe-riorapproachtoaveragingacrossconditions,whichresultsinboth informationlossandreliesonaknowledgeofthecorrelationsof outcomesacrossconditionswhicharerarelyreported(Fisherand Tipton,2014).

SeparateanalyseswereconductedforOFF/ONfunctionalstates, toexaminewhetherpainsensitivityisalteredbytreatment (typ-icallydopaminergicmedication).Forthespecificoutcomeofpain ratings,weonlyexaminedk=5outof7studieswhere stimula-tionintensitywasidenticalforboththePDandcontrolgroups(i.e., whereafixed-intensity/fixed-timeparadigmwasused),toavoid anyconfoundingofgroupdifferencesinpainratingswithgroup differencesinstimulationintensity.

2.7.3. Meta-regressionanalyses

Ifeffectsizesshowedmoderateorgreaterinconsistencyacross studiesasassessedbyHiggin’sI2(Higginsetal.,2003),with

val-uesof25%,50%and75%correspondingtolow,moderateandhigh inconsistency,meta-regressionwasconductedtoidentifypossible underlyingsourcesofvariation.

First, we examined symptom severity (as measured by the UPDRS-III),diseaseduration(years)and,for painthreshold,the assessmentmethod(limits vs.constant/adjustedstimuli)as pri-marymoderators,basedona rationaledefinedapriori.Greater symptomseverity and longer disease duration likely toreflect increasedneurodegenerationandthereforemaybeassociatedwith agreaterdegreeofabnormalpainperception.Inaddition,the meth-odsof limits (whereintensity increasesto a pre-defined limit) involvesareactiontimeartefact(e.g.frompressingabutton)which couldartificiallyinflatethresholdtimesand underestimatetrue levelsof pain selectively for PD patientsdue to motor impair-ment (Cury et al., 2016). Conversely, the methods of constant stimuli/adjustment(where constant temperaturesaregradually adjusted)(seeYarnitskyandPud,2004)containsnoreactiontime component.

Secondary moderators were study gender composition, age, stimulus modality, PD side subject to pain testing (least/most affected),anatomicsitesubjecttopaintesting,andsample per-centageexperiencingPD-basedpaincomplaints. Thesevariables wereexaminedtoprovidepreliminarydataonanypotential mod-eratinginfluence,asallhavebeensuggestedaspossibleinfluences (Filetal.,2013).Additionally,meaningful studyvalidity criteria wereassessedasmoderators,suchascaseandcontrolselection, criteria-basedPDdiagnosis,explicitmentioningofdisallowingpain medications.Finally,wheretheendorsementofimportant valid-itycriteriavariedacrossstudies,theinfluenceofthesecriteriaas potentialmoderatorsofeffectsizewasalsoassessed.

2.8. Publicationbias

Publicationbiaswasexaminedthroughvisualinspectionof fun-nelplotsof meanstudyESsagainststandard errors. Anyvisual asymmetryresultingfromtheabsenceofsmallsamplestudieswith smallESscansuggestpossiblepublicationbias.Asymmetrywas alsotestedstatisticallywithEgger’sbiastest(Eggeretal.,1997) withp<0.05indicatingasymmetry.Ifpresent,arevisedeffectsize assumingthepresenceofpublicationbiaswascomputedusingthe trimandfillmethod(DuvalandTweedie,2000).

Asthecitationreferstoapackage(robumeta)withina com-puterprogram(R):allanalyseswereperformedusingtherobumeta

package(FisherandTipton,2014)inR(RCoreTeam,2014).

3. Results

3.1. Studyselection

3047uniquehits wereidentifiedthroughdatabasesearches, with6additionalrecordsidentifiedthroughmanualsearchingof referencelists.Followingtheinitialscreeningofabstracts,47 arti-cleswereretainedforfulltextreviewofwhich21wereexcluded, resultinginatotalof26studiesretainedforanalysis(Fig.1).

3.2. Participantcharacteristics

The26retainedstudiesprovidedaggregateddataforN=1292 participants,consistingof739patientsand 553HCs. Themean study age (k=26 studies) was 63.8 years (SD=3.0, range of means=58.8–69.9years)fortheaggregatedPDsample,and62.4 years(SD=3.9,rangeofmeans=54.8–71.4years)fortheaggregated HCsample.ThePDsampleconsistedof35.7%femalesandtheHC sampleconsistedof42.7%offemales(k=26).

ForthePDsample,meandiseaseduration(k=25)was7.1years (SD=3.4, range of means=1.8–15.5). Symptom severity(k=25) wasmostcommonlymeasuredwiththeoriginalUPDRS-IIIMotor Examinationscale(FahnandElton,1987)andwasassessed dur-ingbothON(k=19;UPDRS-IIIM=21.8)andOFF(k=13;UPDRS-III

M=27.0) functional states. ON states were achievedwith anti-Parkinsonmedication(k=18)ordeepbrainstimulation(k=1).

A diagnosisofPD wasbased onUKBBC (k=18),ICD-10:G20 (k=1),GelbNINDSguidelines(k=1)orwassimplyreportedasa clinicaldiagnosisofPD(k=6).Medicationdata(k=24)includeda singlestudywhichusedamedication-naïvepatientsample(Tan et al., 2015), while 23 studies reported regular usage of anti-Parkinsonmedication(L-DOPAwith/withoutothermedication)by someor allenrolled patients(M=95%, study range=67–100%). Most studies (k=22) specified a minimum level of cognitive functioning for inclusion in the study, withscores ≥25 onthe

Mini-MentalStateExaminationbeingthemostextensivelyused inclusioncriterion(k=15).

Presenceorabsenceofaprimarychronicpainconditionwas reported by 13 studies. Of these, 12 reported noco-occurring chronicpainconditionsandasinglestudyreportedthat2patients mayhaveexhibitedchroniclowbackpain.Themeanstudy percent-ageofPDpatientsreportingsecondarypaincomplaintsattributable toPD(k=18)was48%.

3.3. Studycharacteristics

T.Thompsonetal./AgeingResearchReviews35(2017)74–86 81

Records idenfied through database searching

(n = 4212)

Screenin

g

Included

Eligibility

Idenficao

n Addional records idenfied

through other sources (n = 6)

Records aer duplicates removed (n = 3047)

Records screened (n = 3047)

Records excluded (n =3000)

Full-text arcles assessed for eligibility

(n = 47)

Full-text arcles excluded, with reasons (n = 21)

duplicated data (n=9) no healthy control group (n=4) no experimental pain smulus (n=3)

no response to data request (n=2) authors (conference papers) not

locatable (n=2) no direct pain assessment (n=1)

Studies included in qualitave synthesis

(n = 26)

Studies included in quantave synthesis

(meta-analysis) (n = 26)

Fig.1.PRISMAflowdiagram.

The majority of studies used pain threshold (k=21) as the methodofpainassessment(k=11methodoflimits,k=7methodof levels/adjustment,k=3notstated),withotheroutcomesincluding painintensityratings(k=7),paintolerance(k=3)andthreshold formoderatepain(k=3),withseveralindividualstudies employ-ingmultipleinductionandassessmentmethods.Ninestudiesalso assessedsensorythreshold.Aside fromonestudythatincluded onlydrug-naïvepatients(Tanetal.,2015),OFFstateswereachieved bythewithdrawalofdopaminergicmedication,withpaintesting usuallytakingplaceaftera≥12-hwashoutperiod.

Asummaryofthekeycharacteristicsofthe26individualstudies ispresentedinTable1.

3.4. Studyvaliditycriteria

Acceptable agreement across the two raters was found for mostitems(Kappa=0.77–1.00)exceptfor thosewithhighrates ofendorsement(minKappa=0.25).Highendorsementratescan resultinlowkappavaluesduetomarginalhomogeneity(Gwet, 2002)andthuspercentageagreementacrossraterswascomputed, withresultantpercentagesindicatinggoodagreement(>87%)for thoseitems.Completeconsensuswasreachedwheneverany dis-agreementoccurred(seeAppendixS1forallitemratings).

Ratings indicated methodological soundness (e.g., reporting offunctionalstateduringtesting,completedataprovided,clear descriptionofprocedures)forthemajorityofstudies(>85%formost criteria).Moststudiesexcludedpatientswithcomorbiddepression (77%)orsomatosensorydisorder(73%),with42%explicitly specify-ingthatuseofpainmedication(<24h)wasanexclusioncriterion. Lowendorsementof‘selectionofPDcases(23%)andcontrols(27%) validitycriterionreflectedlimiteddetailonrecruitmentmethods;

althoughstudiesdidgenerallystatethenameoftherecruiting hos-pitalandprovidegooddescriptionsofcharacteristicsofcontrols, usuallymatchingcasesandcontrolseitherexperimentallyorby statisticallycontrollingforage/gender(77%).

Somestatisticalinconsistencieswerenoted.Onestudy(Nolano etal.,2008)reportedimplausiblepainthresholds(9.1–12.4◦C)for

heatstimulation(valuesforotherstimuliwereplausible),anda furtherstudy(Schestatskyetal.,2007)reportedmeansandSDsfor painthresholdhighlyinconsistentwithreportedp-values(even whenSDsweretreatedasSEMs),andsothisspecificdatawere excluded.

3.5. Meta-analysisresults

3.5.1. Painthreshold

Painthresholddatawasexaminedfork=20studies compris-inga total sampleofN=926(n=577PD,n=473HCs),withPD patents assessed during both OFF (k=14; N=728) and/or ON (k=13;N=617)states.Sevenrepeated-measuresstudiesprovided painthresholddataforbothONandOFFstates.

Meta-analysis ofpain threshold,aggregating data fromboth ONandOFFstates,foundsignificantlyloweroverallpain thresh-old(i.e.,greaterpainsensitivity)inPDpatientscomparedtoHCs (SMD=0.37,CI95[0.16,0.57],p=0.001).Moderatetohigh

hetero-geneity(I2=63%)wasobservedandk=16of20studiesreported

lowerpainthresholdsinPD.

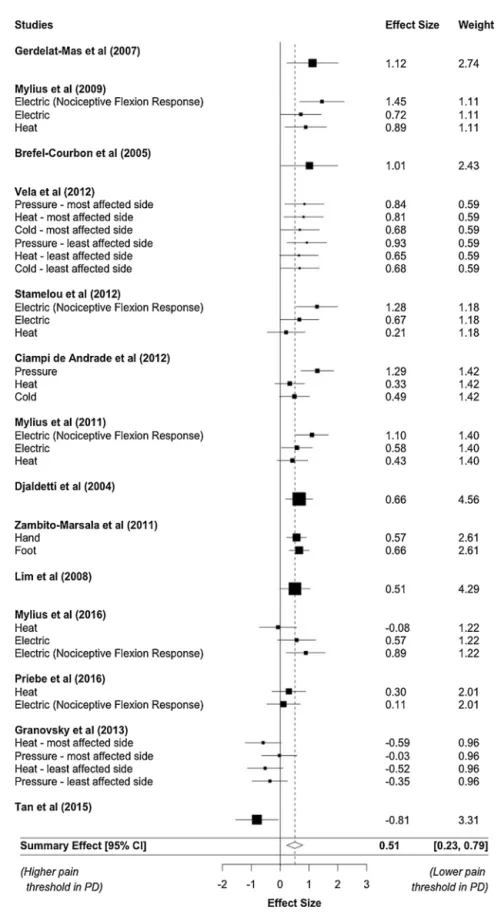

Whenseparatemeta-analyseswereperformedforONandOFF statedata,significantlylowerpainthresholdsinPDpatients com-pared toHCs werefound for the OFFstate (k=14;SMD=0.51, CI95[0.23,0.79],p=0.002),alongwithmoderate-high

82 T.Thompsonetal./AgeingResearchReviews35(2017)74–86

Fig.2.Forestplotofpainthreshold,withboxsizesproportionaltostudyweights(forstudieswithmultipleoutcomes,weightsaredividedevenlyacrossoutcomes).

wasalsofoundbutwithareducedeffectsize(k=13;SMD=0.23, CI95[0.02,0.45],p=0.04)andmoderateheterogeneity(I2=49%).A

forestplotofpainthresholddatafortheOFFstateisprovidedin

Fig.2.

T.Thompsonetal./AgeingResearchReviews35(2017)74–86 83

3.5.2. Suprathresholdpainresponse

Threestudiesreportedpaintolerancedata,and3other stud-ies reported ‘threshold to moderate pain’ (where participants weretold towithdraw fromnoxious stimulation when experi-encingmoderatepain).Bothmeasureswerecollapsedtoasingle suprathresholdpaincategorytomaximisepower(threestudiesis insufficientforRVE analysis).The 6combined studiesprovided aggregatedatafor442participants(n=288PDpatients,n=154 HCs).Painassessment occurredduring bothON (k=5)and OFF states(k=4),with3studiesprovidingdataforbothstates.

Meta-analysisofoverallsuprathresholddatafoundlower tol-erancetosuprathresholdpain(suggestinggreatersensitivity)in PDpatients,butthisjustfailedtoachievestatisticalsignificance (SMD=0.30,CI95[−0.01,0.61],p=0.06).Analysisofdifferent

func-tional states indicated lower tolerance to suprathreshold pain duringOFF(k=4;SMD=0.44,p=0.04)statesbut notduringON (k=5;SMD=0.15,p=0.28)states.ForanalysisofOFFstatedata, populationconfidenceintervals(andthusp-values)maybewider ornarrower(Tipton,2015)astheadjusteddf<4.Lowheterogeneity wasobservedinallinstances(I2=4–27%).

Afunnelplotofoverallsuprathresholddatasuggested asymme-tryduetothepresenceofasmallsamplestudywithalargenegative

effectsize.Someindicationofpossibleasymmetryemergedfrom Egger’stest,whichfailedtoachievesignificance(butisalsolikelyto beunderpoweredwithonly6studies),z=1.90,p=0.054,Arevised estimateusing trimandfillmethodssuggested aslightly larger effectsize(SMD=0.36,p=0.01)ifpublicationbiasisassumed.

3.5.3. Otheroutcomes:painratingsandsensorythreshold

TheadjusteddffromRVEmeta-analysisofpainratingsand sen-sorythresholdwere<4(reflectingbothlimitednumberofstudies usingtheseassessmentmethodsanddatadependency),which pre-cludedreliableestimationofESs(Tipton,2015)fortheseoutcomes.

3.6. Meta-regressionanalyses:painthreshold

Meta-regressionanalyseswereconductedtoidentify underly-ingsourcesofheterogeneityinESsacrosspainthresholdstudies (other pain outcomes were not examined due to limited data not meetingRVE requirements).Functional state (ON/OFF)was includedasanadditionalvariablein eachanalysistomaximise powerbyallowinguseofallpainthresholddata(i.e.fromboth ONandOFFstates),andgiventhatfunctionalstateduringtesting islikelytorepresentasubstantialsourceofvariationinESacross studiesthatshouldbecontrolledforasapossibleconfounder.In addition,includingfunctionalstateasamoderatorallowsthedirect assessmentofwhetherdifferencesacrossONvs.OFFstates identi-fiedinthemeta-analysis(Section3.5.1)weresignificant.

3.6.1. PDseverity

We examinedwhetherreduced pain threshold(greaterpain sensitivity)inPDwasexacerbatedinpatientswithmoreadvanced diseasestates,byincludingdiseasedurationandUPDRS-IIIscores as moderators in separate analyses. Results indicated that dif-ferences between PD and controls in pain threshold were not significantly influenced by disease duration (k=19; B=0.035,

p=0.24)orUPDRS-IIIsymptomseverity(k=19;B=0.006,p=0.71). Resultsalsoindicatedthat effectsizewassignificantlylarger (k=19;SMD=0.33,CI95[0.02,0.64],p=0.039)forOFF(B=0.58)

thanON(B=0.25)states.Thispatternofresultswasreproduced (k=19;SMD=0.33,CI95[0.02,0.66],p=0.041),whenanalysiswas

restrictedtoONstatesachievedthroughdopaminemedicationonly (i.e.thesingledeepbrainstimulationstudywasexcluded).

3.6.2. Methodofassessment

Enteringassessmentmethod(limitsvs.levels/adjustment)asa moderatorinmeta-regressionofpainthresholdrevealedthatthe differenceinpainthresholdbetweenPDpatientsandcontrolswas largerwhenthemethodoflevels/adjustmentwasused,although this failedto reach statistical significance (k=18; SMD=0.34,

p=0.061).

3.6.3. Secondarymoderators

Separatemeta-regressionanalyseswereconductedtoexplore othermoderatorsspecifiedinSection2.7.3.As15painthreshold studiesexplicitlystatedtheuseofestablisheddiagnosticcriteria and5studiesdidnotprovideinformation,wealsoexaminedthis variableasapotentialmoderator.Givenlimiteddataforcertain anatomiccategories,wecollapseddatatoformtwobroadanatomic categoriesofarm(forearm,upperarm,hand)andleg(leg,foot). Forthemultiplecategoricalvariableofstimulusmodality,a no-interceptmodelwasanalysedsothateachcoefficientrepresented theabsoluteESforeachstimulusmodality(ratherthanthe dif-ference inESbetweenthat modalityand anarbitraryreference modality).

No evidence was found for moderating effects of studies’ gender composition (k=20; p=0.38), mean study age (k=20;

p=0.62), affected vs. non-affected side tested (k=9; p=0.91), anatomic site tested (k=17;p=0.43)or diagnosticcriteria pro-vided(k=20;p=0.55).Forstimulusmodality(k=20),however,PD patientsdemonstratedlowerpainthresholdthanHCsinresponse to cold (SMD=0.62, p=0.011), electrical (SMD=0.53, p<0.001) and pressure (SMD=0.41, p=0.055) stimuli, but not heat stim-uli(SMD=−0.05,p=0.79).PD-relatedpaincouldnotbereliably

assessedasamoderator,astheadjusteddfwas<4(Tipton,2015).

3.6.4. Studyvaliditycriteria

Given low endorsement for validity criteria of selection of cases/controlsandreportingofpainmedicationuse(Section3.4), these variables were entered as moderators in separate meta-regression analyses of pain threshold. Neither case selection (p=0.79)orcontrolselection(p=0.68)significantlymoderatedthe ES.DifferencesinpainthresholdbetweenPDpatientsandcontrols wereamplifiedinstudiesexplicitlystatingthatparticipantswere notusingpainmedication,althoughthisdidnotachievestatistical significance(SMD=0.40,p=0.052).

3.7. Repeated-measuresstudiescomparingONvs.OFFstates

Aspreviousanalyses(Section3.6.1)revealedthatdifferences betweenPDsandcontrolswerereducedduringtheONstate,we conductedastricterevaluationbyrepeatingtheanalysisincluding onlythe7studiesthatdirectlycomparedONvs.OFFina repeated-measuresdesignstoensuresuperiorcontrolofconfounds.Results wereinlinewithpreviousfindings(Section3.6.1),withdifferences inpainthresholdbetweenPDpatientsandHCsattenuated dur-ingONstates(k=7;SMD=−0.25,CI95[−0.11,−0.38],p=0.004).

Removalof two studiesthat didnotrandomize/counterbalance ON/OFFstateorfailedtotestHCsatequivalentintervals,hadlittle impactonresults(k=5;SMD=−0.22,p=0.045).Only4studies

providedL-DOPAdosagesduringONstates,whichwasnot suffi-cienttomeetrequirementsforRVEmeta-regression.

4. Discussion

84 T.Thompsonetal./AgeingResearchReviews35(2017)74–86

severalkeyfindings:(1)OverallpainthresholdwaslowerinPD patients(indicatinggreaterpainsensitivity)comparedtoHCs;(2) SuprathresholdpainwaslowerinPDpatients,althoughthis nar-rowlyfailedtoreachsignificance;(3)Abnormalpainthresholds in peoplewith PD duringOFF states (SMD=0.51) were signifi-cantlydiminished,butnotcompletelynormalizedduringONstates (SMD=0.23) produced bydopaminergic medication; (4) Abnor-malpainthresholdswerenotsignificantlyinfluencedbysymptom severity,diseaseduration,sexorage;(5)Whilemost(16/20) indi-vidualstudiesindicatedlowerpainthresholdinPD,moderateto highvariationineffectsizessuggeststhatother,unidentified vari-ablescouldinfluenceabnormalpainresponsesinPD.

4.1. PainhypersensitivityinPDandclinicalimplications

Resultsfromourmeta-analysisprovideevidencethatpatients withPDdemonstrate greatersensitivity tonoxious stimulation comparedtoHCs,whichseemtobeindependentofageandsex,and whichoccurformosttypesofaversivestimuli.Althoughnooverall differenceswerefoundforheatstimulation,thepost-hocnature ofthisresultmeansanyconclusionsofmodality-specific nocicep-tiveprocessing abnormalities in PDshould bemade extremely cautiouslyandwouldrequireindependentreplication.

Takentogether,theseresultssuggestthattheincreased preva-lence and intensity of clinicalpain complaints in PD couldbe, atleastin part,influenced byabnormal nociceptiveprocessing. In particular, these results could explain the increased preva-lenceof non-musculoskeletalpain complaints(e.g., neuropathic pain),whichdonotobviouslydirectlyresultfrommotor dysfunc-tion.Althoughcaremustbetakenintranslatingeffectsizesfrom experimentally-inducedpaintoreal-lifepainexperiences,thefact thatanSMD=0.51(inmedication-freeOFFstates)canbe classi-fiedasamoderateeffect(Cohen,1988),providessomepreliminary indicationthattheimpactofPDonpaincomplaintsoutsideofthe laboratorymaynotbetrivial.

Thereisalsosometentativeevidencetosuggestthatthetrue extentofincreasedpainsensitivitycouldbeunderestimatedbythe moderateeffectsizeweobserved.Studiesthatexplicitlystatedthat participantswerenotreceivingpainmedication(withPDpatients generallybeingmorelikelytoregularlyusepainkillers)werelinked toalargereffectsize(anSMDincreaseby0.40).Inaddition, stud-iesemployingthemethodsoflevels/adjustment,whichhasbeen arguedtogiveamoreaccurateestimateof painthresholdthan themethodoflimitsduetoareducedreactiontimeartefact,also demonstratedalargereffectsize(anSMDincreaseby0.34).Itis importantthatthesefindingsaretreatedcautiously,asalthough suggestive,neithersubgroupanalysis reachedstatistical signifi-cance(p=0.052–0.061).

4.2. Roleofdopamine

ThepartialnormalisationoftheatypicalpainthresholdsinPD resultingfromdopaminergicmedicationappearstobea robust finding, which was observed when all studies were examined andwhenonlyrepeated-measuresstudies,whichprovidesuperior controlof potentialconfounds,wereincluded.Thispartial nor-malisationofpainthresholdhasanumbertheoreticalandclinical implicationswhichwarrantfurtherelaboration.

First, this finding offers indirect evidence for an underly-ing role of dopamine depletion in pain hypersensitivity in PD. Although identifying exact underlying mechanisms is difficult fromtheavailabledata,dopaminecouldelicitpain hypersensitiv-ityeitherindirectlythroughmodulatoryeffectsonaffectivepain processingand/or directlyby affecting neuronal activityat key pain-modulatingareas inthe brainsuchasthethalamus, basal ganglia,insula,anteriorcingulatecortexandperiaqueductalgrey

(Filetal.,2013;Jarchoetal.,2012).Reduceddopaminergic neu-rotransmissionmayimpairnaturalanalgesiathroughadecreased activationofdopamine-mediatedpaininhibitorypathways.These descendfromthesubstantianigratothesubstantiagelatinosain thespinalcordandinhibittransmissionofascendingnociceptive signals(Filetal.,2013).Thisdirectroleofdopamineisconsistent withPET studies in healthy participantsthat show an associa-tion between greater subjective pain and decreased dopamine activity(Curyetal.,2016),thediminishedpainresponseseenin schizophrenia(Stubbsetal.,2015)adisorderlinkedtoaberrant dopaminergicneurotransmission,andevidencefromanimal mod-elssuggestingaroleofdopamineinchronicregionalpainsyndrome (Wood,2008).ExperimentalresearchonpaininPDpatients assess-ingtheeffectofpro-dopaminergicandantidopaminergicstatesor medicationscouldhelpfurtherelucidatetheroleofdopaminein painperception.

Second,ifattenuationofpaincanbeachievedthrough dopamin-ergicmedication,thissuggeststhatthedevelopmentofclassesof novelcompoundsthatefficientlytargetdopaminepain-inhibitory pathwaysmayhavepotentialaseffectiveanalgesics.Such com-poundsmaybeeffectiveanalgesicsbothforPDandforotherpainful disorderslinkedtodisruptedendogenousdopamineactivitysuch as fibromyalgia, burning mouth syndrome and painful diabetic neuropathy(Jarchoetal.,2012;Wood,2008).Furthermore,ifthe suggestionthat the underuseof conventional painkillers in PD patientsisattributabletopoorefficacyinthisgroup(Perez-Lloret etal.,2012),suchmedicationscouldprovidepotentiallysuperior alternatives.Theutilityofsuchanalgesicscouldevenextendto conventional treatmentin healthyindividuals withpain. While theroleofopioidsandnon-dopaminergic (e.g.noradrenergicor serotoninergic)pathwaysiswellrecognised,thecurrentfindings furthersuggestameaningfulrolefordopamine-mediatedanalgesia andmayprovidetheimpetusforfurtherstudyinvolvingpreclinical modelsandneuroimagingtechniquesinhumans.

4.3. Partialpainthresholdnormalisation

The fact that dopamine medication diminished but did not appeartocompletelynormalisepainthreshold,suggeststhat addi-tionalmechanismsarelikelytocontributetopainhypersensitivity inPD.Althoughitisdifficulttoidentifysuchmechanismsfrom thecurrentavailabledata,thesecouldincludealossofepidermal nerve fibres(Nolano etal., 2008) ordeficiencies in other, non-dopaminergicpain pathways.Analternativeexplanationis that painhypersensitivityisentirelymediatedbydopaminedeficiency inPDbutthatstudymedicationdosageswereinsufficienttorestore dopamineneurotransmissiontonormalphysiologicallevels.Due toinsufficientavailabledata,wewerenotabletoassesswhether higherL-DOPAdosageswereassociatedwithgreaternormalisation ofpainthreshold.

4.4. Independenceofmotorimpairmentandpain

T.Thompsonetal./AgeingResearchReviews35(2017)74–86 85

4.5. Limitations

Whilstthesedataprovidenovelinsightsintoalteredpain per-ceptioninPD,somelimitationsshouldbenoted.Firstly,findings arebasedprimarilyonpainthresholdwhichwasthemost com-monlystudiedpainoutcome.Althoughanestablishedmeasureof painsensitivity,painthresholdrepresentspainatthelowerendof theintensitycontinuumandcannotbeautomaticallygeneralised tomoreintenselevelsofclinicalpain.Second,althoughadequate datawasavailableformeta-regression,genuinemoderatingeffects ofvariables(e.g.diseaseduration)thatwerenon-significant can-notbedismissed,andmaybedetectablewithmoreavailabledata; especiallyifthemagnitudeoftheseeffectsissmall.Third,although exclusion of PDpatientswithcognitiveimpairment in primary studies wasnecessary tomaximise adherence to experimental requirements, current findings should be necessarily restricted toPD patientswho have relativelypreserved overall cognition (Folsteinetal.,1975).

4.6. Futureresearchdirections

Despitetheselimitations,thecurrentfindingsprovidestrong supportthatindividualswithPDexhibitgreatersensitivityto nox-iousstimulithan HCs,basedonlaboratorystudiesthatprovide acontrolofpotentialconfoundersnoteasilyachievablein clini-calsettings.Futurestudiesareneededtohelpestablishwhether pain hypersensitivityin PDextends tosuprathreshold levelsof pain,andinsightsmayalsobegainedfromtheuseof ischemic anddermalcapsaicinexperimentalpainmodelsthatevoke sev-eralaspectsofchronicpainwhilstpreservingstrictexperimental control(Staahletal.,2009).Moreresearchinvolvingpreclinical modelsandneuroimagingtechniquesinhumanswouldalsohelpto elucidatepotentialmechanisticpathwaysunderlyingalteredpain perceptioninPD.

4.7. Conclusions

Totheauthors’knowledge, this istheonly published meta-analysisofstudiescomparingPDpatientswithhealthycontrolsin theirresponsetocontrolledexperimentalpainstimulation.Results indicatesignificantlylowerpainthresholdinPDpatients (indica-tiveofgreaterpain)intheOFFstatecomparedtocontrols.Thiswas partially(butnotcompletely)normalizedbydopaminergic medi-cation,suggestingthatdisruptionofdopaminepainpathwaysmay contributeto abnormalpain processing.These findings suggest thatPDmayconferahypersensitivitytonociceptiveinformation thatcouldbothexacerbatethemusculoskeletalpainresultingfrom motorrigidityandabnormalposturecontrol,andcontributetothe lesscommonbutneverthelesstroublingnon-musculoskeletalpain complaintsthatoccurinPD.

Disclosures

TT,KG,NV,EWandBShavenoconflictsofinterest.AFCis sup-portedbyaresearchfellowshipawardfromtheConselhoNacional deDesenvolvimentoCientíficoeTecnológico(CNPq;Brazil).CUC has been a consultant and/or advisor to or has received hon-oraria from: Alkermes, Allergan, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forum, GersonLehrman Group, IntraCellular Therapies, Janssen/J&J,LB Pharma, Lundbeck, Medavante, Medscape, Neurocrine, Otsuka, Pfizer,ProPhase,Sunovion,Supernus,Takeda,and Teva.He has providedexperttestimonyforBristol-MyersSquibb,Janssen,and Otsuka.HeservedonaDataSafetyMonitoringBoardforLundbeck andPfizer.HereceivedgrantsupportfromTakeda.

Acknowledgements

WeareespeciallygratefultoDrsGergelyOrsi,YelenaGranovsky, JonStoessl,MariaNolano,TomohikoNakamura,MasanakaTakeda, JanoschPriebefortheirrapidandexceptionallyhelpfulresponses torequestsforadditionalstudydata.Wearealsoextremelygrateful toProfessorJohnLeesandDrAlastairNoyceofUniversityCollege Londonfortheirinvaluableadviceandextremelyhelpful commen-taryonthemanuscript.

AppendixA. Supplementarydata

Supplementarydataassociatedwiththisarticlecanbefound,in theonlineversion,athttp://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2017.01.005.

References

Allen,N.E.,Moloney,N.,Hassett,L.M.,Canning,C.G.,Lewis,S.J.G.,Cruz-Mavignier, K.,Barry,B.K.,2016.Exerciseinducedanalgesiaispresentinpeoplewith Parkinson’sdisease.Mov.Disord.31.

Apkarian,A.V.,Bushnell,M.C.,Treede,R.D.,Zubieta,J.K.,2005.Humanbrain mechanismsofpainperceptionandregulationinhealthanddisease.Eur.J. Pain9,463–484.

Aschermann,Z.,Nagy,F.,Perlaki,G.,Janszky,J.,Schwarcz,A.,Kovacs,N.,Bogner,P., Komoly,S.,Orsi,G.,2015.Wind-up’inParkinson’sdisease:afunctional magneticresonanceimagingstudy.Eur.J.Pain19,1288–1297. Borenstein,M.,Hedges,L.,Higgins,J.,Rothstein,H.R.,2009.Introductionto

Meta-Analysis.Wiley,WestSussex.

Brefel-Courbon,C.,Payoux,P.,Thalamas,C.,Ory,F.,Quelven,I.,Chollet,F., Montastruc,J.L.,Rascol,O.,2005.Effectoflevodopaonpainthresholdin Parkinson’sdisease:aclinicalandpositronemissiontomographystudy.Mov. Disord.20,1557–1563.

Broen,M.P.,Braaksma,M.M.,Patijn,J.,Weber,W.E.,2012.Prevalenceofpainin Parkinson’sdisease:asystematicreviewusingthemodifiedQUADAStool. Mov.Disord.27,480–484.

Chaudhuri,K.R.,Odin,P.,2010.Thechallengeofnon-motorsymptomsin Parkinson’sdisease.Prog.BrainRes.184,325–341.

Chaudhuri,K.R.,Schapira,A.H.,2009.Non-motorsymptomsofParkinson’sdisease: dopaminergicpathophysiologyandtreatment.LancetNeurol.8,464–474. Chaudhuri,K.R.,Prieto-Jurcynska,C.,Naidu,Y.,Mitra,T.,Frades-Payo,B.,Tluk,S.,

Ruessmann,A.,Odin,P.,Macphee,G.,Stocchi,F.,Ondo,W.,Sethi,K.,Schapira, A.H.,MartinezCastrillo,J.C.,Martinez-Martin,P.,2010.Thenondeclarationof nonmotorsymptomsofParkinson’sdiseasetohealthcareprofessionals:an internationalstudyusingthenonmotorsymptomsquestionnaire.Mov.Disord. 25,704–709.

Chen,Y.,Mao,C.J.,Li,S.J.,Wang,F.,Chen,J.,Zhang,H.J.,Li,L.,Guo,S.S.,Yang,Y.P., Liu,C.F.,2015.Quantitativeandfiber-selectiveevaluationofpainandsensory dysfunctioninpatientswithParkinson’sdisease.ParkinsonismRelat.Disord. 21,361–365.

CiampideAndrade,D.,Lefaucheur,J.P.,Galhardoni,R.,Ferreira,K.S.,BrandãoPaiva, A.R.,Bor-Seng-Shu,E.,Alvarenga,L.,Myczkowski,M.L.,Marcolin,M.A.,de Siqueira,S.R.,Fonoff,E.,Barbosa,E.R.,Teixeira,M.J.,2012.Subthalamicdeep brainstimulationmodulatessmallfiber-dependentsensorythresholdsin Parkinson’sdisease.Pain153,1107–1113.

Cohen,J.,1988.StatisticalPowerAnalysisfortheBehavioralSciences.Lawrence EarlbaumAssociates,Hillsdale,NJ.

Cury,R.G.,Galhardoni,R.,Fonoff,E.T.,PerezLloret,S.,DosSantosGhilardi,M.G., Barbosa,E.R.,Teixeira,M.J.,CiampideAndrade,D.,2016.Sensory

abnormalitiesandpaininParkinsondiseaseanditsmodulationbytreatment ofmotorsymptoms.Eur.J.Pain20,151–165.

Deeks,J.J.,Dinnes,J.,D’Amico,R.,Sowden,A.J.,Sakarovitch,C.,Song,F.,Petticrew, M.,Altman,D.G.,International,S.T.C.G.,European,C.S.T.C.G.,2003.Evaluating non-randomisedinterventionstudies.HealthTechnol.Assess.7,iii–x,1. Djaldetti,R.,Shifrin,A.,Rogowski,Z.,Sprecher,E.,Melamed,E.,Yarnitsky,D.,2004.

QuantitativemeasurementofpainsensationinpatientswithParkinson disease.Neurology62,2171–2175.

Duval,S.,Tweedie,R.,2000.Trimandfill:asimplefunnel-plot-basedmethodof testingandadjustingforpublicationbiasinmeta-analysis.Biometrics56, 455–463.

Egger,M.,DaveySmith,G.,Schneider,M.,Minder,C.,1997.Biasinmeta-analysis detectedbyasimple,graphicaltest.BMJ315,629–634.

Fahn,S.,Elton,R.L.,1987.In:Fahn,S.,Marsden,C.D.,Calne,D.B.,Goldstein,M. (Eds.),RecentDevelopmentsinParkinson’sDiseaseII.MacMillanHealthCare Information,NewJersey,pp.153–163.

Fil,A.,Cano-de-la-Cuerda,R.,Mu ˜noz-Hellín,E.,Vela,L.,Ramiro-González,M., Fernández-de-Las-Pe ˜nas,C.,2013.PaininParkinsondisease:areviewofthe literature.ParkinsonismRelat.Disord.19,285–294,discussion285. Fisher,Z.,Tipton,E.,2014.Robumeta:Robustvariancemeta-regression.Rpackage

86 T.Thompsonetal./AgeingResearchReviews35(2017)74–86

Folstein,M.F.,Folstein,S.E.,McHugh,P.R.,1975.Mini-mentalstate:apractical methodforgradingthecognitivestateofpatientsfortheclinician.J.Psychiatr. Res.12,189–198.

Ford,B.,2010.Paininparkinson’sdisease.Mov.Disord.25(Suppl.1),S98–103. Gerdelat-Mas,A.,Simonetta-Moreau,M.,Thalamas,C.,Ory-Magne,F.,Slaoui,T.,

Rascol,O.,Brefel-Courbon,C.,2007.Levodoparaisesobjectivepainthreshold inParkinson’sdisease:aRIIIreflexstudy.J.Neurol.Neurosurg.Psychiatry78, 1140–1142.

Goetz,C.G.,Stebbins,G.T.,Tilley,B.C.,2012.CalibrationofunifiedParkinson’s diseaseratingscalescorestoMovementDisorderSociety-unifiedParkinson’s diseaseratingscalescores.Mov.Disord.27,1239–1242.

Granovsky,Y.,Schlesinger,I.,Fadel,S.,Erikh,I.,Sprecher,E.,Yarnitsky,D.,2013. AsymmetricpainprocessinginParkinson’sdisease.Eur.J.Neurol.20, 1375–1382.

Grashorn,W.,Schunke,O.,Buhmann,C.,Forkmann,K.,Diedrich,S.,Wesemann,K., Bingel,U.,2015.Influenceofdopaminergicmedicationonconditionedpain modulationinparkinson’sdiseasepatients.PLoSOne10,e0135287. Gwet,K.,2002.Inter-raterreliability:dependencyontraitprevalenceand

marginalhomogeneity.Stat.MethodsInter-RaterReliab.Assessment2,1–9. Hara,T.,Hirayama,M.,Mizutani,Y.,Hama,T.,Hori,N.,Nakamura,T.,Kato,S.,

Watanabe,H.,Sobue,G.,2013.ImpairedpainprocessinginParkinson’sdisease anditsrelativeassociationwiththesenseofsmell.ParkinsonismRelat.Disord. 19,43–46.

Hedges,L.V.,Tipton,E.,Johnson,M.C.,2010.Robustvarianceestimationin meta-regressionwithdependenteffectsizeestimates.Res.Synth.Methods1, 39–65.

Higgins,J.P.,Thompson,S.G.,Deeks,J.J.,Altman,D.G.,2003.Measuring inconsistencyinmeta-analyses.BMJ327,557–560.

Jarcho,J.M.,Mayer,E.A.,Jiang,Z.K.,Feier,N.A.,London,E.D.,2012.Pain,affective symptoms,andcognitivedeficitsinpatientswithcerebraldopamine dysfunction.Pain153,744–754.

Lim,S.-Y.,Farrell,M.J.,Gibson,S.J.,Helme,R.D.,Lang,A.E.,Evans,A.H.,2008.Do dyskinesiaandpainsharecommonpathophysiologicalmechanismsin Parkinson’sdisease.Mov.Disord.23,1689–1695.

Lipsey,M.,Wilson,D.,2001.PracticalMeta-Analysis.Sage,London.

Maruo,T.,Saitoh,Y.,Hosomi,K.,Kishima,H.,Shimokawa,T.,Hirata,M.,Goto,T., Morris,S.,Harada,Y.,Yanagisawa,T.,Aly,M.M.,Yoshimine,T.,2011.Deep brainstimulationofthesubthalamicnucleusimprovestemperaturesensation inpatientswithParkinson’sdisease.Pain152,860–865.

Massetani,R.,Lucchetti,R.,Vignocchi,G.,Siciliano,G.,Rossi,B.,1989.Pain thresholdandpolysynapticcomponentsoftheblinkreflexinParkinson’s disease.Funct.Neurol.4,199–202.

Mitra,T.,Naidu,Y.,Martinez-Martin,P.,2008.Thenondeclarationofnonmotor symptomsofParkinson’sdiseasetohealthcareprofessionals.Aninternational surveyusingtheNMSQuest.In:6thInternationalCongressonMental DysfunctionsandOtherNon-motorFeaturesinParkinson’sDiseaseand RelatedDisordersDresdenOctober,2008ParkRelatedDisorders,P0II:161. Moher,D.,Liberati,A.,Tetzlaff,J.,Altman,D.G.,PRISMA,G.,2009.Preferred

reportingitemsforsystematicreviewsandmeta-analyses:thePRISMA statement.BMJ339,b2535.

Mylius,V.,Engau,I.,Teepker,M.,Stiasny-Kolster,K.,Schepelmann,K.,Oertel,W.H., Lautenbacher,S.,Möller,J.C.,2009.Painsensitivityanddescendinginhibition ofpaininParkinson’sdisease.J.Neurol.Neurosurg.Psychiatry80,24–28. Mylius,V.,Brebbermann,J.,Dohmann,H.,Engau,I.,Oertel,W.H.,Möller,J.C.,2011.

PainsensitivityandclinicalprogressioninParkinson’sdisease.Mov.Disord. 26,2220–2225.

Mylius,V.,Pee,S.,Pape,H.,Teepker,M.,Stamelou,M.,Eggert,K.,Lefaucheur,J.P., Oertel,W.H.,Möller,J.C.,2016.Experimentalpainsensitivityinmultiple systematrophyandParkinson’sdiseaseatanearlystage.Eur.J.Pain20, 1223–1228.

Nègre-Pagès,L.,Regragui,W.,Bouhassira,D.,Grandjean,H.,Rascol,O.,DoPaMiP, S.G.,2008.ChronicpaininParkinson’sdisease:thecross-sectionalFrench DoPaMiPsurvey.Mov.Disord.23,1361–1369.

Nandhagopal,R.,Troiano,A.R.,Mak,E.,Schulzer,M.,Bushnell,M.C.,Stoessl,A.J., 2010.ResponsetoheatpainstimulationinidiopathicParkinson’sdisease.Pain Med.11,834–840.

Nolano,M.,Provitera,V.,Estraneo,A.,Selim,M.M.,Caporaso,G.,Stancanelli,A., Saltalamacchia,A.M.,Lanzillo,B.,Santoro,L.,2008.Sensorydeficitin Parkinson’sdisease:evidenceofacutaneousdenervation.Brain131, 1903–1911.

Perez-Lloret,S.,Rey,M.V.,Dellapina,E.,Pellaprat,J.,Brefel-Courbon,C.,Rascol,O., 2012.EmerginganalgesicdrugsforParkinson’sdisease.ExpertOpin.Emerg. Drugs17,157–171.

Priebe,J.A.,Kunz,M.,Morcinek,C.,Rieckmann,P.,Lautenbacher,S.,2016. ElectrophysiologicalassessmentofnociceptioninpatientswithParkinson’s disease:amulti-methodsapproach.J.Neurol.Sci.368,59–69.

Quittenbaum,B.H.,Grahn,B.,2004.QualityoflifeandpaininParkinson’sdisease: acontrolledcross-sectionalstudy.ParkinsonismRelat.Disord.10,129–136. RCoreTeam,2014.R:ALanguageandEnvironmentforStatisticalComputing.R

FoundationforStatisticalComputing,Vienna,Austria.

Schestatsky,P.,Kumru,H.,Valls-Sole,J.,Valldeoriola,F.,Marti,M.J.,Tolosa,E., Chaves,M.L.,2007.Neurophysiologicstudyofcentralpaininpatientswith Parkinsondisease.Neurology69,2162–2169.

Schrag,A.,Horsfall,L.,Walters,K.,Noyce,A.,Petersen,I.,2015.Prediagnostic presentationsofParkinson’sdiseaseinprimarycare:acase-controlstudy. LancetNeurol.14,57–64.

Staahl,C.,Olesen,A.E.,Andresen,T.,Arendt-Nielsen,L.,Drewes,A.M.,2009. Assessinganalgesicactionsofopioidsbyexperimentalpainmodelsinhealthy volunteers–anupdatedreview.Br.J.Clin.Pharmacol.68,149–168. Stamelou,M.,Dohmann,H.,Brebermann,J.,Boura,E.,Oertel,W.H.,Höglinger,G.,

Möller,J.C.,Mylius,V.,2012.Clinicalpainandexperimentalpainsensitivityin progressivesupranuclearpalsy.ParkinsonismRelat.Disord.18,606–608. Stroup,D.F.,Berlin,J.A.,Morton,S.C.,Olkin,I.,Williamson,G.D.,Rennie,D.,Moher,

D.,Becker,B.J.,Sipe,T.A.,Thacker,S.B.,2000.Meta-analysisofobservational studiesinepidemiology:aproposalforreporting.Meta-analysisOf

ObservationalStudiesinEpidemiology(MOOSE)group.JAMA283,2008–2012. Stubbs,B.,Thompson,T.,Acaster,S.,Vancampfort,D.,Gaughran,F.,Correll,C.U.,

2015.Decreasedpainsensitivityamongpeoplewithschizophrenia:a meta-analysisofexperimentalpaininductionstudies.Pain156,2121–2131. Takeda,M.,Okada,F.,Tachibana,H.,Kajiyama,K.,Yoshikawa,H.,2013.

NeurophysiologicstudyofpaininParkinson’sdisease:astudywith pain-relatedevokedpotentials.Mov.Disord.28,S79.

Takeda,M.,Tachibana,H.,Okada,F.,Kasama,S.,Yoshikawa,H.,2014.Painin patientswithparkinson’sdisease;apain-relatedevokedpotentialstudy. Neurosci.Biomed.Eng.2,36–40.

Tan,Y.,Tan,J.,Luo,C.,Cui,W.,He,H.,Bin,Y.,Deng,J.,Tan,R.,Tan,W.,Liu,T.,Zeng, N.,Xiao,R.,Yao,D.,Wang,X.,2015.Alteredbrainactivationinearlydrug-naive Parkinson’sdiseaseduringheatpainstimuli:anfMRIstudy.Parkinson’sDis. 2015,273019.

Thompson,T.,Correll,C.U.,Gallop,K.,Vancampfort,D.,Stubbs,B.,2016.Ispain perceptionalteredinpeoplewithdepression?Asystematicreviewand meta-analysisofexperimentalpainresearch.J.Pain17,1257–1272. Tipton,E.,2015.Smallsampleadjustmentsforrobustvarianceestimationwith

meta-regression.Psychol.Methods20,375–393.

Valkovic,P.,Minar,M.,Singliarova,H.,Harsany,J.,Hanakova,M.,Martinkova,J., Benetin,J.,2015.Paininparkinson’sdisease:across-sectionalstudyofits prevalence,types,andrelationshiptodepressionandqualityoflife.PLoSOne 10,e0136541.

Vela,L.,Lyons,K.E.,Singer,C.,Lieberman,A.N.,2007.Pain-pressurethresholdin patientswithParkinson’sdiseasewithandwithoutdyskinesia.Parkinsonism Relat.Disord.13,189–192.

Vela,L.,Cano-de-la-Cuerda,R.,Fil,A.,Mu ˜noz-Hellín,E.,Ortíz-Gutiérrez,R., Macías-Macías,Y.,Fernández-de-Las-Pe ˜nas,C.,2012.Thermalandmechanical painthresholdsinpatientswithfluctuatingParkinson’sdisease.Parkinsonism Relat.Disord.18,953–957.

Wells,G.A.,Shea,B.,O’Connell,D.,Peterson,J.,Welch,V.,Losos,M.,Tugwell,P., 2008.TheNewcastle-OttawaScale(NOS)forAssessingtheQualityof NonrandomisedStudiesinMeta-Analyses(Accessed8May2016).Availableat: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinicalepidemiology/oxford.asp.

Wood,P.B.,2008.Roleofcentraldopamineinpainandanalgesia.ExpertRev. Neurother.8,781–797.

Yarnitsky,D.,Pud,D.,2004.In:Binnie,C.D.,Cooper,R.,Mauguiere,F.,Osselton, J.W.,Prior,P.F.,Tedman,B.M.(Eds.),ClinicalNeurophysiology:EMG,Nerve ConductionandEvokedPotentials,vol.1.Elsevier,Amsterdam,p.305. Zambito,M.S.,Tinazzi,M.,Vitaliani,R.,Recchia,S.,Fabris,F.,Marchini,C.,Fiaschi,