Correspondence address: Andréia Martins de Souza Cardoso R. João de Oliveira Soares, 400, Jardim Camburi, Vitória (ES), Brasil, CEP: 29090–390.

E-mail: andreiasouz@yahoo.com.br

Received: 12/26/2011

Accepted: 1/29/2013

Study carried out at the Universidade Veiga de Almeida – UVA – Rio de Janeiro (RJ), Brasil.

(1) Professional Master’s Program in Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology, Universidade Veiga de Almeida – UVA – Rio de Janeiro (RJ), Brasil.

Conlict of interests: nothing to declare.

Artigo Original

Andreia Martins de Souza Cardoso1 Mônica Marins da Silva1 Mônica Medeiros de Britto Pereira1

Keywords

Child language Memory Short-term Health literacy Learning; Cognition

Descritores

Linguagem infantil Memória de curto prazo Alfabetização em saúde Aprendizagem; Cognição

children with and without literacy dificulties

A consciência fonológica e a memória de trabalho de

crianças com e sem diiculdades na alfabetização

ABSTRACT

Purpose:Toinvestigate phonological awareness and working memory skills as well as their inluence on the lit-eracy process in a group of intellectually normal children. Methods:Forty intellectually normal children (7.6–8.0 years) from the second and third grades of elementary school participated. Children were organized in two groups (20 children each): one with and another without literacy dificulties. These participants underwent RAVEN’s in-telligence quotient test, audiometric assessment, CONFIAS test of phonological awareness, written spelling task, and working memory test. Results:Children in the alphabetic phase presented a good development of phonologi-cal awareness, and 85% of them showed a high-performance working memory. Children in the syllabic-alphabet-ic phase had changes in phonologsyllabic-alphabet-ical awareness, and 91.6% of them showed an average working memory perfor-mance. The subjects at pre-syllabic and syllabic phases demonstrated more dificulties in phonological awareness than those at syllabic-alphabetic and had a poor working memory performance. Between-group differences were observed for CONFIAS and working memory tests (p<0.0001). There was also a signiicant correlation (r=0.78, p=0.01) between the skills of phonological awareness and working memory for the total sample of individuals.

Conclusions:Based on these results, it was found that as phonological awareness and working memory levels increased, the literacy phase also advanced, therefore showing that these are directly proportional measures.

RESUMO

Group 1 comprised 14 boys and six girls, whereas Group 2 comprised 14 girls and 6 boys without literacy dificulties. The average age and the minimum and maximum ages were similar for both groups.

It was estimated that the subjects presented the same socioeconomic level because they were attending a public school located in the same municipality. Children with altera-tions in the audiometric test and the intelligence quotient (IQ) test were excluded. Children who had grade delay, school fail-ure, language delay, and neurological and visual alterations, according to the information provided by the parents in the initial interview, were also excluded.

The following instruments were used: RAVEN IQ test-Colored Progressive Matrices(16), tonal audiometry, CONFIAS phonological awareness test considering tasks of syllabic and phonemic awareness(17), spelling written test by Capovilla and Capovilla(18), and working memory test by Curi(1).

Children were referred by teachers of municipal schools to IQ testing, which was administered by a psychologist of a City Health Unit. Next, the students underwent audiometric evalua-tion. All those who had alterations in these tests were excluded from the study and referred for medical and speech, language, and hearing follow-up. Thus, it was possible to select a sample of 40 cognitively normal children who had auditory thresholds within normal limits. Speech and language evaluations then were applied. The written spelling test was the irst to be per-formed in order to identify the literacy level. Thus, two groups emerged, one comprising 20 children with delay in the literacy process, i.e., in the pre-syllabic, syllabic, or syllabic-alphabetic phases (Group 1), and another comprising 20 children at the level of writing in alphabetic phase (Group 2). The CONFIAS test was then used to assess phonological awareness. The work-ing memory test was later performed by the psychologist. After the evaluations, the results were statistically analyzed using tests to estimate the correlation and differences between pho-nological awareness and working memory for each group (non-parametric Spearman correlation test, non(non-parametric paired t

test, Wilcoxon test, and Kruskal-Wallis test).

RESULTS

Table 2 displays the mean, standard deviation, and mini-mum and maximini-mum values of syllable, phoneme, and overall CONFIAS and working memory tests for Groups 1 and 2.

Table 3 shows the difference between the means and sig-niicance levels of the variables tested in groups with and without literacy dificulties.

Table 1. Distribution of participants according to age and gender Participants n Mean age

(years)

Minimum age (years)

Maximum age (years)

Group 1 (boys) 14 7.7 7.6 8.0

Group 1 (girls) 6 7.7 7.6 8.0

Group 2 (boys) 6 7.7 7.6 8.0

Group 2 (girls) 14 7.7 7.6 8.0

INTRODUCTION

The written code is a form of linguistic representation that implies the ability to comprehend ideas, store information, and transmit messages, enabling the individual to interact with the literate world in which he is inserted(1-3). During the learning process, many children develop literacy dificulties for different reasons. Memory is one of the most important aspects that enables learning. Memory deicits can cause dif-iculty in storing taught information, thus hindering the acqui-sition of reading and writing(4,5).

The process of learning to read and write requires effort and a stimulating environment(6,7). Being literate means acquiring the ability to encode oral in written language and decode writing into oral language. Reading and writing also refer to the apprehension and comprehension of meanings expressed in written language (reading) and their expression through the written language (writing)(6,8,9).

Visuospatial and phonological processes are important for the acquisition of written language. Visual and phonological information, once perceived, are stored in the working mem-ory and then transferred to long-term memmem-ory, enabling the learning of phoneme-grapheme association(1,10,11).

Through memory, one can perform storage and retrieval of linguistic information (oral or written). A dysfunction in these processes can affect the ability to read and write(12,13).

During the literacy process, phonological and visual infor-mation must be recorded in working memory and transferred to the long-term memory in order to bring about the learning of written language(14,15). Because of this importance of work-ing memory in alphabetical phonological awareness, workwork-ing memory assessments become indispensable for children who are learning how to read and write.

Thus, the aim of this study was to investigate the phono-logical awareness and working memory as well as their inlu-ence on literacy in a group of intellectually normal children with and without literacy dificulties.

The integrity of working memory, among other aspects, allows the process of comprehending reading and writing, enabling the formation of a functionally literate citizen, i.e, an individual who is able to make use of written language for his/ her individual needs(1, 2,4,10).

METHODS

This research was initiated after approval from the Ethics Committee of Universidade Veiga de Almeida, Rio de Janeiro, under resolution number 274/11. All parents or guardians involved in the research signed an informed consent.

labic-alphabetic phase, 91.6% exhibited a median performance of working memory and 8.3% exhibited a low performance.

Correlation between phonological awareness and working memory

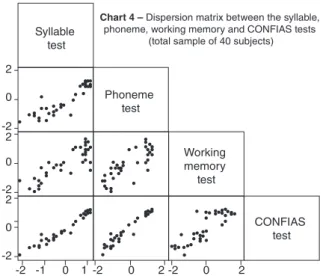

Tables 4 and 5 show the test results of Spearman correlations. Correlations between variables (syllables, phonemes, working memory, and CONFIAS) and their signiicance levels for each group are separately presented for each group (Table 4) and with the two groups combined (Table 5). Visual representations of such data can be found in Figures 1 (Group 1), 2 (Group 2), and 3 (Groups 1 and 2 combined). As can be noted in Table 4, there were positive correlations between the four variables (syllables, pho-nemes, working memory, and CONFIAS) in Group 1, whereas in Group 2, correlations were found between syllables, phonemes, and CONFIAS. Note that the variable CONFIAS is composed of the sum of the scores of the syllable and phoneme but not of the working memory. This result is justiied by the fact that most of the subjects in Group 2 exhibited a high performance in phono-logical awareness and working memory, which is expected for the children in Group 2. For both groups combined, there were posi-tive correlations between the four variables studied.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of Groups 1 and 2

Children with literacy delay Group 1 (20 children with literacy delay) Group 2 (20 children without literacy delay) Minimum Maximum Mean Standard deviation Minimum Maximum Mean Standard deviation

Syllable test 11 32 22.1 5.2 33 40 37.8 1.8

Phoneme test 5 20 10.7 3.9 18 29 26.3 2.9

CONFIAS test 16 44 32.8 7.8 51 69 64.1 4.4

WM test 16 27 22.3 3.6 24 36 31.3 3.2

Legends: WM = working memory; CONFIAS = sequential instrument of phonological awareness assessment

With respect to the phonological awareness test (CONFIAS), the average performance of Group 1 was lower than Group 2 (32.8 and 64.1, respectively). The standard deviation of Groups 1 and 2 was 7.8 and 4.4, respectively. These numbers reinforce that the groups were suficiently distinct regarding the variable of phonological skills. The group of 20 children in the alpha-betic phase scored above 46 on CONFIAS, which determines a good development of phonological awareness. The other 20 participants, in pre-syllabic, syllabic, and syllabic-alpha-betic phases, presented scores below 46 on CONFIAS exhibit-ing dificulties in phonological awareness skill.

In the working memory test, the average performance of Group 1 was 22.3, signiicantly lower than Group 2 (31.3). The standard deviation was 3.6 in Group 1 and 3.2 in Group 2. The results of the working memory test show a between-group difference (9 points, p<0.001). This indi-cates that the two groups were different in relation to work-ing memory performance. Most individuals in the alphabetic phase presented high working memory performance. Of the 20 alphabetic, 85% exhibited high working memory performance and 15% exhibited an average performance. The group of chil-dren with delayed literacy process had more heterogeneous results. Individuals at pre-syllabic and syllabic phases showed lower performance of working memory. Of those in the

syl-Table 3. Difference between means of groups with and without literacy dificulties

Test Absolute difference between means p-value Percentage difference between

means

Syllable test 15.7 <0.001 70.8

Phoneme test 15.7 <0.001 146.9

WM test 9.0 <0.001 40.4

Total CONFIAS 31.3 <0.001 95.6

t test (p<0.05)

Legends: WM = working memory; CONFIAS = sequential instrument of phonological awareness assessment

Table 4. Results of correlations between CONFIAS and working memory tests of Groups 1 and 2

Children with literacy delay

Group 1 (20 children with literacy delay) Group 2 (20 children without literacy delay)

Syllable Phoneme WM CONFIAS Syllable Phoneme WM CONFIAS

Syllable — 0,56* 0,77** 0,9** — 0,48* -0,09 (0,7) 0,8**

Phoneme — — 0,55* 0,82** — — -0,06 (0,8) 0,88**

WM — — — 0,68** — — — -0,15 (0,5)

* statistically signiicant correlation at 0.05 (two-tailed); ** statistically signiicant correlation at 0.01 (two-tailed)

Between-group difference test results

The Wilcoxon and Kruskal–Wallis tests were also performed to investigate possible differences between Groups 1 and 2. Their indings conirm the hypothesis that the groups with and without literacy delay are different in all varia-bles with a signiicance level of 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The present study showed that the majority of children in the alphabetic writing phase showed good development of phonological awareness, and most students who were not in this phase had dificulties in this task. These indings are in line with some studies on phonological awareness(6-8,17,19-22), conirming the existence of correlation between levels of pho-nological awareness and written language acquisition.

Several studies report different author opinions regarding the relationship between phonological awareness and work-ing memory. Some authors(1,3,13) argue that this relationship is positive, whereas others(4) argue that it is negative. However, most defend the idea that working memory and phonological awareness are a part of phonological processing. Therefore, there is a correlation between the two, indicating a dependent relationship between these two skills, as the nature of pro-cessed information is phonological. Memory operations rep-resented by encoding, storage, and retrieval of information are needed in order to perform phonological awareness tasks.

This correlation is evident in that most of the children who had dificulties in phonological awareness and memory tests also had scores that characterized low or median per-formance of working memory. Most participants with good development of phonological awareness exhibited a high working memory performance. Thus, as the phonological awareness increased, the level of working memory perfor-mance also increased.

From the hypothesis of correlation between phonologi-cal awareness and working memory, some authors sought to determine the inluence of both on the learning process of written language. These researchers state that working mem-ory maintains phonological and symbolic information of writ-ten language that are temporarily stored and active, allowing its transfer to long-term memory which, in turn, would result in learning(2,10,14).

Figure 1. Scatter matrix of syllable, phoneme, working memory, and CONFIAS tests (Group 1)

Figure 2. Scatter matrix of syllable, phoneme, working memory, and CONFIAS tests (Group 2)

Figure 3. Scatter matrix of syllable, phoneme, working memory, and CONFIAS tests (40 participants in total)

Correlation between the total sample tests

Total sample (40 children)

Syllable Phoneme WM CONFIAS

Syllable — 0,88* 0,8* 0,96*

Phoneme — — 0,78* 0,96*

WM — — — 0,78*

Table 5. Results of correlations between the tests CONFIAS and working memory of the total sample

* statistically signiicant correlation at 0.01 (two-tailed); descriptive statistics and Spearman correlation tests were calculated using SPSS 18.0

Legends: WM = working memory; CONFIAS = sequential instrument of phono-logical awareness assessment

0

0

0

0 0 0

-2

-2

-2

-2 -2 -2

-1

-1

-1 -1

Syllable test

Phoneme test

Working memory

test

CONFIAS test

Chart 1 – Dispersion matrix between the syllable, phoneme, working memory and CONFIAS tests

(group of students with literacy delay)

1,5

1,5 1

-1 1

1 0,5

0,5 0

0

0 2

0,5 1 1,5 00,5 1 1,5-1 0 1 2 Syllable

test

Phoneme test

Working memory

test

CONFIAS test

Chart 2 – Dispersion matrix between the syllable, phoneme, working memory and CONFIAS tests

(group of students without literacy delay)

2

2

2 0

0

0 -2

-2

-2

-2 -1 0 1 -2 0 2-2 0 2 Syllable

test

Phoneme test

Working memory

test

CONFIAS test

Chart 4 – Dispersion matrix between the syllable, phoneme, working memory and CONFIAS tests

* AMSC was responsible for implementing the project, preparation of the manuscript, collection and tabulation of data; MMBP was responsible for the overall direction, supervision of data collection and implementation steps; MMS collaborated orientation of the project and its stages and execution.

REFERENCES

1. Curi N. Atenção, memória e diiculdades de aprendizagem [tese]. Campinas: Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Faculdade de Educação; 2002. 2. Rodrigues C. Contribuições da memória de trabalho para o processamento

da linguagem. Evidências experimentais e clínicas [pós-doutorado]. Santa Catarina: Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Linguística, Letras e Artes; 2001.

3. Segers E, Verhoeven L. Long-term effects of computer training of phonological awareness in kindergarten. J Comput Assist Learn. 2005;21(1):17-27.

4. Gillam RB, Van Kleeck A. Phonological awareness training and short-term working memory: clinical implications. Topics Lang Disord. 1996;17(1):72-81.

5. Jeronymo RR, Galera A. A relação entre a memória fonológica e a habilidade lingüística de crianças de 4 a 9 anos. Pro Fono. 2000;12(12):55-60. 6. Maluf MR, Barrera SD. Consciência fonológica e linguagem escrita em

pré-escolares. Psicol Relex Crit. 1997;10(1):125-45.

7. Moraes J, Kolinsky R, Alégria J, ScliarCabral L. Alphabetic literacy and psychological structure. Letras de Hoje. 1998;33(4):61-79.

8. Capellini SA, Ciasca SM. Avaliação da consciência fonológica em crianças com distúrbio especíico de leitura e escrita e distúrbio de aprendizagem. T Desenv. 2000;8(48):17-23.

9. Marcuschi LA. Oralidade e letramento.In: Marcuschi LA. Dafala para a escrita:atividades de retextualização. São Paulo: Cortez; 2001. p. 15-43. 10. Gindri G, Kesk-Soares M, Mota HB. Memória de trabalho, consciência

fonológica e hipótese de escrita. Pro Fono. 2007;19(3):313-22.

11. Santos RM, Siqueira M. Consciência fonológica e memória. Fono Atual. 2002;5(20):48-53.

12. Gathercole S, Baddeley A. Working memory and language. Hove: Lawrence Eribaum; 1993.

13. Oakhill J, Kyler F. The relations between phonological: awareness and working memory. J Exp Child Psycol. 2000;75(2):152-64.

14. Linassi LZ, Keske-Soares M, Mota HB. Habilidades de memória de trabalho e o grau de severidade do desvio fonológico. Pro Fono. 2005;17(3):383-92. 15. Lobo FS, Acrani IO, Avila CR. Tipo de estímulo e memória de trabalho

fonológica. Rev Cefac. 2008;10(4):461-70.

16. Raven JC. Matrizes progressivas coloridas de raven. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo; 1987.

17. Moojen S, Lamprecht R, Santos RM, Freitas GM, Brodacz R, Siqueira M, et al. CONFIAS Consciência Fonológica: Instrumento de Avaliação Seqüencial. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo; 2003.

18. Pinheiro AMV. Leitura e Escrita: uma abordagem cognitiva. Campinas: Psy II; 1994.

19. Santamaria VL, Leitão PB, Assencio-Ferreira VJ. A consciência fonológica no processo de alfabetização. Rev Cefac. 2004;6(3):237-41.

20. Bride-Chang C, Ho C. Developmental issues in Chinese children character acquisition. J Educ Psychol. 2000;92(1):50-5.

21. Cárnio MS, Santos D. Evolução da consciência fonológica em alunos de ensino fundamental. Pro Fono. 2005;17(2):195-200.

22. Capovilla AGS, Capovilla FC. Efeitos do treino de consciência fonológica em crianças com baixo nível sócio-econômico. Psicol Relex Crit. 2000;13(1):7-24.

The results of the current study demonstrate that partici-pants at the alphabetic writing level showed good develop-ment of phonological awareness, and most of them exhibited a high memory performance. Children in the syllabic-alpha-betic phase had phonological awareness alterations, and most of them exhibited a median working memory perfor-mance. In contrast, most participants in the pre-syllabic and syllabic phases showed more dificulties in phonological awareness skills than those in the syllabic-alphabetic phase and exhibited a low memory performance. Thus, these results are consistent with the studies cited, once they show the inluence of phonological awareness and working mem-ory alterations in the literacy process of children. However, this study complements other studies by demonstrating that intellectually normal children may have changes in phono-logical awareness and working memory, causing a dificulty in the literacy process.

Previous studies have shown that phonological aware-ness and working memory are inter-related and associated with cognitive activities(10,11). The present study supports these indings, showing that these skills are concurrently developed and in this process, they have an inluence on the literacy process. As phonological awareness develops, the performance level of working memory also increases and vice versa. However, this does not mean that phonological awareness determines the development of working memory or vice versa. It is only possible to afirm that the higher the levels of phonological awareness and working memory, the better the literacy phase of a child will be. Thus, these are directly proportional measures. Further, one can say that the phonological awareness development occurs in conjunction with that of working memory, helping in determining the literacy phase of an individual.

CONCLUSION

The current study veriied the correlation between phonological awareness and working memory as well as that phonological awareness and working memory alterations may inluence the literacy process of intellectually normal children.