Abstract

The spirituality implications in health have been scientifically evaluated and documented in hundreds of ar-ticles. Diabetes is a disease that has increasing incidence. Our goal was to understand the implication of spirituality on diabetic patients, correlating it with their life quality. This research was developed at Diabetes Education Center in the Pouso Alegre, Minas Gerais. The sample consisted of 20 patients presenting Diabetes. A questionnaire consisting of three questions was applied, data were recorded and transcribed. In the uni-verse of 20 people interviewed, they consisted mostly of women, married, unemployed, and with incomplete primary education. The study demonstrated that, for the group included, the meaning of spirituality is related to religious aspects, as they showed attachment to them in order to be able to carry their lives with Diabetes and imporve, therefore, their quality of life.

Key words: Spirituality. Quality of life. Diabetes mellitus.

Resumo

Espiritualidade e qualidade de vida em pacientes com diabetes

As implicações da espiritualidade na saúde vêm sendo cientificamente avaliadas e documentadas em cente-nas de artigos. O diabetes é uma doença que vem apresentando incidência com proporções cada vez maiores. Nosso objetivo foi conhecer o significado de espiritualidade para pacientes diabéticos, correlacionando-o com sua qualidade de vida. Esta pesquisa desenvolveu-se no Centro de Educação em Diabetes da Prefeitura Municipal de Pouso Alegre (MG). A amostra foi constituída por 20 pacientes portadores de diabetes. O discur-so do sujeito coletivo constituiu o método escolhido para a construção dos significados. Foi aplicado um ques-tionário composto de três perguntas, gravadas e transcritas na íntegra. O perfil dos entrevistados, na maioria, era de mulheres, casadas, com ensino fundamental incompleto e desempregadas. O estudo demonstrou que para elas o significado de espiritualidade está ligado a aspectos religiosos, aos quais se apegam para conseguir conviver com o diabetes e melhorar, assim, sua qualidade de vida.

Palavras-chave: Espiritualidade. Qualidade de vida. Diabetes mellitus.

Resumen

Espiritualidad y calidad de vida en pacientes con diabetes

Las implicaciones de la espiritualidad en la salud han sido científicamente evaluadas y documentados en cientos de artículos. La Diabetes es una enfermedad que presenta incidencia con proporciones cada vez más grandes. Nuestro objetivo era comprender el significado de la espiritualidad para los pacientes diabéticos, en correlación con su calidad de vida. Esta investigación se desarrolló en el Centro de Educación sobre la Diabetes de la Alcaldía Municipal de Pouso Alegre, Minas Gerais. La muestra consistió en 20 pacientes con diabetes. El discurso del sujeto colectivo fue el método elegido para la construcción de los significados. Se aplicó cuestio-nario que constaba de tres preguntas, grabadas y transcritas integralmente. El perfil de los encuestados, en su mayoría eran mujeres, casadas, desempleadas y con estudios primarios incompletos. El estudio demostró que el significado de la espiritualidad para ellas está vinculado a aspectos religiosos, que se aferran a ser capaces de vivir con diabetes y así mejorar su calidad de vida.

Palabras-clave: Espiritualidad. Calidad de vida. Diabetes mellitus.

Aprovação CEP Fipa CAAE – 04187212.2.0000.5102

1. Graduanda millaluengo@gmail.com 2. Doutora drijar@hotmail.com – Universidade do Vale do Sapucaí (Univas), Pouso Alegre/MG, Brasil.

Resear

Bioethics is the bridge between science and the humanities, traditionally understood as an ap-plication of ethics that deals with the proper use of new technologies in the field of medical sciences and proper solution of moral dilemmas presented by it. Thus, the matters involving personal religious issues of patients need to be inserted in the understanding of clinical practice one, considering that the respect for the values that who cares is fundamental to the

ethical link between health professional and patient 2.

Although concept with various interpretations, spirituality can be understood as the belief that ac-cepts and tries to develop the spiritual part of

hu-mans as opposed to its material part 3 is a dynamic,

personal and experiential 4 process, which seeks to

confer meaning and significance to life, may coexist

or not the practice of a religious creed 5 religiosity,

however, is based on the acceptance of a particular set of values . Some authors suggest that religion is institutional, dogmatic and restrictive, while

spiritu-ality is personal, subjective and emphasizes life 5.

Despite the scientific controversy about the effects of spirituality on health is a reflection of Ro-berts: It should be clear that if these benefits come

from an intervention or God’s answer to the calls of prayer and spirituality, it will always be beyond what science can not prove or 6.

Quality of life (QOL) refers to the concept seen as subjective, because besides differ from individu-al to individuindividu-al is subject to change throughout life. Nahas shows that factors that determine the QOL of people are many and their combination results in a phenomena and situations that, abstractly, can be called quality of life network. Associated factors such as health, longevity, job satisfaction, salary, lei-sure, family relationships, mood, pleasure and even spirituality generally, are: In a broader sense quality

of life can be a measure of human dignity, because it involved service fundamental human needs 7.

From the point of view of health, Dreher8

sho-ws that QOL can be divided into six dimensions: physical, emotional, social, professional, intellectual

and spiritual. Minayo 9, in turn, meant that QoL is an

eminently human notion that maintains relationship with the satisfaction of the individual with his fami-ly, loving, social, environmental and existential life encompassing the skills, experiences and values of individuals and collectivities , at a particular time,

place and situation.

The morbidity associated with longstanding diabetes, both types results in certain complications such as microangiopathy, retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy. If no adequate metabolic control, long-term complications can occur, with consequen-ces such as amputation, blindness, retinopathy, ne-phropathy, among other consequences that would compromise the quality of life of these people. The-refore, the basis for these chronic long-term com-plications is the subject of much research. Diabetic suffering with the clinical manifestations of disease, such as polyuria, polydipsia, polyphagia, weight loss

and asthenia 10.

This chronic non-communicable disease re-quires adjustments to lifestyle and incorporating therapeutic practices involving changes in dietary patterns, glycemic control, physical activity, maintai-ning blood pressure and continuous monitoring by

a multidisciplinary team of 10 health Living with

Dia-betes mellitus (DM) implies adjust to the complex dynamics of family relationships, feelings, lifestyle and habit changes, fitness routines, implementation of care and glycemic control procedures, aiming to DM a healthy living and prevention acute and

chro-nic complications 11 the way people perceive their

condition influences the overall control of their state

of health and disease 12,13.

The development of QoL studies, the impor-tance and involvement of spiritual issues were present. Therefore, it is understood that the field of quality of life can come to become a mediator between the field of health and religious / spiritu-al issues, which may facilitate the development of health interventions that have the foundation in the

spiritual dimension 14 . Under this perspective, this

paper aims to know the meaning of spirituality for diabetic patients, and that spirituality can influence a better adherence to treatment, thus providing a better quality of life.

Methods

This study adopted a qualitative descriptive approach was developed in the Municipality of the city of Landing Alegre (MG) Center for Diabetes Education (Cemed) in the period from 2.1.2013 to

Resear

30.9.2013, having sampled 20 patients with diabe-tes. The criteria for participation in the study were being treated for at least one month older than 18 years at the date of completion of the questionnaires and confirmed diagnosis by analyzing the records.

Because it is qualitative study, in which the main objective is the comprehensive approach to the needs, motivations and behaviors of partici-pants, the sample size was defined conventionally, that is, without a necessary quantitative relationship between the percentage of patients chosen and the number of patients enrolled in the institution. Thus, sampling was intentional, seeking to list on the basis of the researcher’s knowledge about the population and its elements the widest diversity of respondents. To collect data on a semi-structured survey questionnaire consisting of three questions, recor-ded and transcribed was applied. The method cho-sen for the analysis of the material was the discour-se of the collective subject (DSC), badiscour-sed on the cons-truction of meanings, seeking to allow the approach to the phenomenon under study. For data analysis we used the DSC, written in the first person singular, composed of key expressions that have the same core ideas (IC) and anchor (AC).

The autonomy of the study participants was respected by the free decision to participate in the study after providing guidelines that supported his decision. Respected-whether cultural, social, moral and ethical values , habits and customs of the par-ticipants. Procedures to ensure the confidentiality, anonymity of information, privacy and protection of the image of the respondents were provided, by en-suring that the information obtained was not used to the detriment of any kind to the members of the study. The study followed the precepts established by Resolution 196/96 of the National Health Coun-cil, applies to the period in which the application of the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Vale do Sapucai.

Results and discussion

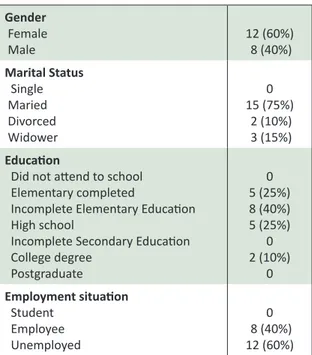

The results were presented in three parts. In the first, are evidenced the personal and social cha-racteristics of respondents (tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Personal and socioeconomic characteristics

of interviewees Gender Female Male 12 (60%) 8 (40%) Marital Status Single Maried Divorced Widower 0 15 (75%) 2 (10%) 3 (15%) Education

Did not attend to school Elementary completed

Incomplete Elementary Education High school

Incomplete Secondary Education College degree Postgraduate 0 5 (25%) 8 (40%) 5 (25%) 0 2 (10%) 0 Employment situation Student Employee Unemployed 0 8 (40%) 12 (60%)

Table 2 Standard deviations and avarage ages of

patients surveyed Standard deviation Average N Male 6,63325 64,00 08 Female 10,8519 62,18182 12 Total 8,777213 62,75 20

In the catchment area studied, the epidemio-logical profile of individuals with diabetes was char-acterized by a predominance of females (60%), for

the planet, according Miranzi 15, the female

popula-tion is larger than the male. This explains in part the higher proportion of women affected by and diag-nosed more often seek health services.

The subjects’ ages ranged between 42 and 79 years (with an average of around 64 years), relevant interval with previous studies, in which there are some studies showing that diabetes is more preva-lent in people over 35 years The 16 schooling, 40% had not completed primary education and 60% were unemployed. According to the Report of Pri-mary Care / 2001, adherence to treatment tends to be lower in individuals with low education and low

Resear

income, which increases the responsibility of family health teams in developing educational activities, with emphasis on disease control to promote health 16 of the total respondents, 75% were married. The World Health Organization (WHO) states that the marital status of individuals influences on family dynamics and self-care. For seniors, family composi-tion can be a decisive factor for the lack of stimulus

to self-care and institutionalization 17.

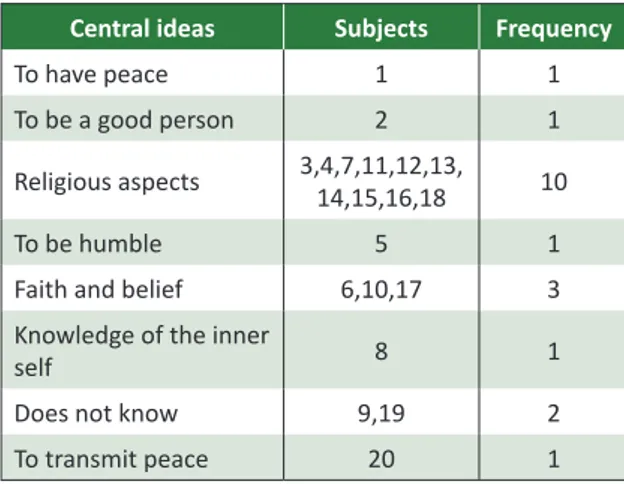

In the second part, the themes explored are shown - with their respective central ideas (Tables 1, 2 and 3) - and finally the last part shows the central ideas accompanied with their respective CSDs. The first question asked was: “What is the meaning of spirituality?”. The CSDs based on the central ideas presented in this question were:

• 1st central idea: have peace ̶ “Spirituality is for

people to have a peace and a quiet ...”;

• 2nd central idea: be a good person ̶ “Spirituality

is a good person, a humorous person ...”;

• 3rd central idea: religious aspects ̶ “Spirituality

for me is religion, a religious person. It is a spirit of kindness, patience (...) is the religious spirit, is the spirit of the people. Be a Christian, one who has God in his heart. I consider all religions, I respect, I try to learn from others ... “;

• 4th central idea: be humble ̶ “Are you having a

spirituality of forgiveness, to accept things. (...) It is humility, being humble ... “;

• 5th central idea: faith and belief ̶ “Overall I think

it’s what the person has belief, the way he act-ed. (...) Is the emotional part. It is something that one has to believe, have to have faith, no matter the religion “;

• 6th central idea: knowledge of the inner self ̶ “I

would say it is the knowledge of my inner self”;

• 7th central idea: do not know ̶ “Do not know”;

• 8th central idea: to transmit peace ̶ “The spirit

has to convey something of peace, (...) a joyful thing ...”.

Although, at first glance, the category “do not know” to denote the absence of a “central idea” in-stead shows the answers of respondents who said

they did not have a formed and / or does not know the meaning of spirituality opinion. Anyway, accord-ing to Table 1, most respondents said that spirituali-ty is linked to religious faith and belief aspects.

Table 1 Central ideas, subjects and frequencies of

theme 1

Central ideas Subjects Frequency

To have peace 1 1

To be a good person 2 1

Religious aspects 3,4,7,11,12,13, 14,15,16,18 10

To be humble 5 1

Faith and belief 6,10,17 3

Knowledge of the inner

self 8 1

Does not know 9,19 2

To transmit peace 20 1

In a study of long follow-up, 18 Strawbridge

evaluated during 28 years, 6928 patients between 16 and 94 years, finding that regular practitioners of religious activities had lower mortality rates. The-se findings were more robust in women; adjusted for history of chronic disease or health risk factors analysis no significant reduction of the impact. Du-ring follow-up, patients with frequent religious prtices stopped smoking, adopted regular physical ac-tivity, increased social support and improved their health.

Jaffe and colleagues 19 also evaluated patients

adherent to religious practices or dwelling areas considered affiliated with religious practices in Is-rael. 141,683 individuals aged 45-89 years were analyzed, living in 882 separate areas; 29,709 deaths were reported at a median follow up of 9.5 years. Just as in the previous example, men and women living in close proximity or affiliated with religious practice areas had lower mortality rates.

Second time, in the same interview, he was asked: “How spirituality gives meaning to your life?”. The central ideas of the key expressions of this question and the frequencies of responses are transcribed in Table 2.

Resear

Table 2. Central ideas, subjects and frequencies of

theme 2

Central ideas Subjects Frequency

Good feelings 1,2,3,5,7,11,13,20 8

Religious aspects 15,16,17,18,194,9,10,12,14, 10 Having a goal to

persuit 6,8 2

The analysis developed from the collective subject discourse based on the central ideas pre-sented in this question were:

First central idea: good feelings ̶ “My life now

it’s good, thank God. Is good because I have peace, quiet, do not have to be thinking is having problems ... joy, patience, fellowship with other people. When you are doing well in life, you’re well too. Helps a lot. For us avoid frustration comes and talks to someone from the church, right? It is very good “;

Second central idea: religious aspects ̶ “We

have to believe in something, have to have strength. It is the belief (...) that gives us strength to continue, right? For we live, we face certain diseases, to take us forward. Help on the day we have peace, hope, faith. I’m very devoted, I am Catholic, I am very devoted to God and Our Lady. I pray every day to protect myself, my children and my husband. The Holy Spirit that God has left here in this world to be our comfort-er (...) then he gives me encouragement in my life. Without religion, without God, we are nothing.”

Third central idea: have a goal ̶ “In everything

because then you have a goal then you think more in his fellow than yourself ... You have to have a goal, you know, something you can play for your life ac-cording to what you think “.

Computing the answers of Table 2 shows that 10 respondents using the central idea of religious aspects, saying that spirituality makes people be-lieve in something, to have faith, hope and peace; while eight said that spirituality transmit good feel-ings and two used the central idea of having a goal to follow. Some researchers found that religiosity tends to increase during negative life events,

in-cluding illness 20 This occurs because the connection

with religion can be a source of relief or discomfort,

depending on how the person she reports 21.

Moreira-Almeida and Koenig 22 found that the

majority of well-conducted studies argues that high-er levels of involvement with religion are positively associated with indicators of psychological well-be-ing (life satisfaction, happiness, positive affect, and higher morale) and with less depression, suicidal behavior and abuse of drugs and alcohol. General-ly, the positive impact of religious involvement on mental health is more exuberant among people un-der stressful life circumstances (the elun-derly, those with a disability and those with a disease).

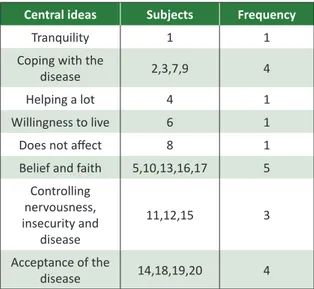

Finally, it was asked “How spirituality has

helped you cope with the diabetes?”. The central

ideas of the key expressions of this question, and the frequency responses are transcribed in Table 3.

Table 3. Central ideas, subjects and frequencies of

theme 3

Central ideas Subjects Frequency

Tranquility 1 1

Coping with the

disease 2,3,7,9 4

Helping a lot 4 1

Willingness to live 6 1

Does not affect 8 1

Belief and faith 5,10,13,16,17 5

Controlling nervousness, insecurity and disease 11,12,15 3 Acceptance of the disease 14,18,19,20 4

The CSDs based on the central ideas presented in this question were:

• 1st central idea: quiet ̶ “So we demand

increas-ingly have peace, peace, avoid nervous be-cause we have to hold the nervous, right? To be healthy “;

• 2nd central idea: coping with the disease ̶

“Spir-ituality helps address of course. I am very at-

Resear

tached to God (...) facing the death of my hus-band and that much of problem I have. Have to fight in order to win “;

• 3rd central idea: helped much ̶ “It has helped

a lot”;

• 4th central idea: the will to live ̶ “Diabetes needs

you have will to live, you’re engaging in always improving”;

• 5th central idea: no effect ̶ “Spirituality does not

affect me”;

• 6th central idea: belief and faith ̶ “It is my belief

in God, my faith that leads I can live with the disease. We have to really believe in God very much in hand and let Him deliver Him in hand. He knows. I pray too for Our Lady of Fatima that leaves my diabetes did not rise much and have a lot of faith, you know, that one day I will not have it anymore. I never lose my faith, because I did not have these things, I did not have dia-betes. Whenever I’m sometimes with some af-fliction I cling to the Divine Eternal Father, is to have faith because if we were aggressive, ner-vous, person did not face “;

• 7th central idea: controlling nervousness,

inse-curity and disease ̶ “I think it helps me behave,

do not get nervous, it helps me control right, does not leave much of trains. I am unsure on that part. Some people have so much faith that speaks, has it, has it. I confess that I am inse-cure. What is stress, depression? It is a distrust of the future, right? “;

• 8th central idea: acceptance of illness ̶ “It helps

because you spend trying to understand things from the religion you begin to understand things ... I thought I’m not the only one, I’m not the first. I think I have to have it there because if I get sad I almost get sick (...) not be stressed, not be unhappy. I have both a health problem and I’m doing well thanks to God. “

On that last question, the highest frequency of responses occurred within the central idea of having belief and faith (five responses). Following, we had four responses within the idea of spirituality helping to tackle the disease; four, using the central idea of spirituality helping to accept the disease; and three in the central idea to help control nervousness, inse-curity and disease.

es in the fight against the disease. Therefore, we feel that for them to reflect, pray or pray is a way to get closer to God and have the strength to withstand

the vicissitudes imposed by the disease 23.

Many patients consider important to the spir-itual dimension in the health-disease process and would appreciate support in this regard, when

nec-essary 24. It appears, also, that patients realize that

spirituality influences their health, this result evi-denced, for example, on research indicating the pos-itive influence of spirituality in lower prevalence of mental disorders, higher quality of life, longer

sur-vival and lower length of stay 2. In this sense, must

be considered the role of the health professional to facilitate this assistance, since it expresses, among others, the ethical principles of respect for

autono-my and beneficence 25.

Recognizing that many factors contribute to the construction of perception of quality of life in individuals, there is growing interest in the study of the phenomenon of religiosity as influential or not health and quality of life in people with both compo-nent states critical health as the general population

considered healthy 26.

Final considerations

The use of different aspects of spirituality and religiosity as support, therapy and determination of positive outcomes in many diseases has made symbolic challenge to medical science. When con-sidering the ethical and method limitations is de-monstrated how dificultoso is made to measure and quantify the impact of religious and spiritual expe-riences by traditional scientific methods.

The influences of spirituality have shown sig-nificant impact on physical health, defining itself as a potential factor preventing the development of disease in previously healthy population reduction and eventual death or impact of various diseases. The evidence has been directed more robust and consistent manner to prevent the scenario: inde-pendent studies, mostly of large numbers of volun-teers and representative of the population, indicate that the regular practice of religious activities has reduced the risk of death so significant.

The use of proper scientific method and

em-Resear

change the perception and behavior of society to-day compared the correlation between spirituality and health paradigm.

The aforementioned results, it is recommen-ded that the focus of spirituality in the care of peo-ple with diabetes should be strengthened, seeking the development of important aspects such as self- esteem, happiness, optimism, hope, faith, sa-tisfaction - and strengthening social and family rela-tionships to patient support.

Thus, it becomes important to approach he-alth professionals with the theme, given that lit-tle has focused on the issue of spirituality in care plans. Many professionals do not feel comfortable dealing with the subject, perhaps because

universi-ties do not prepare their students for this theme 27

This was observed in a recent survey in which more than 90% of teachers of a public medical school, study participants considered that Brazilian univer-sities did not provide enough for the student

infor-mation in this regard 28.

Therefore, knowing the quality of life of indi-viduals with diabetes means an odd moment of un-derstanding and again points to the importance of planning and implementing actions of governmental responsibility, with grounding in scientific informa-tion, to be developed through public policies that in-volve both improving the quality of life of individuals regarding valuation of workers in family health teams. It is believed that the discussion of the rela-tionship between faith, spirituality, illness, healing, health and ethics must advance as they pursue

scientific and biotechnological advances 29.

Discer-ning the best study designs and find the best evi-dence supporting the association between spiritua-lity and health is, well, new, intriguing and profound

paradigm for modern medicine 30.

It is considered, above all, to make the bridge between healthcare and spirituality to the doctor and other health professionals should use, whene-ver possible, sources of referrals from the patient in order to act ethically in favor of both of respect for autonomy as the beneficence of this.

Publication resulting from the project funded by a research grant program of the Foundation for Research Support of Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG), granted to Camila de Moura Leite Luengo.

References

1. Souza VCT. Bioética e espiritualidade na sociedade pós-moderna: desafios éticos para uma medicina mais humana. Rev Bioethikos 2010;4(1):86-91.

2. Lucchetti G, Granero AL, Bassi RM, Latorraca R, Nacif SAP. Espiritualidade na prática clínica: o que o clínico deve saber? Rev Soc Bras Clin Méd. 2010;8(2):154-8.

3. Dantas Filho VP, Sá FC. Ensino médico e espiritualidade. O Mundo da Saúde. 2007;31(2):273-80. 4. Muller PS, Plevak DJ, Rummans TA. Religious involvement, spirituality, and medicine: implications

for clinical practice. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(12):1.225-35.

5. Pais-Ribeiro JL, Pombeiro T. Relação entre espiritualidade, ânimo e qualidade de vida em pessoas idosas. Actas do 5o Congresso Nacional de Psicologia da Saúde. Lisboa: ISPA; 2004: 757-69.

6. Roberts L, Ahamed I, Hall S. Intercessory prayer for the alleviation off ill health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 200;(2):CD000368.

7. Nahas MV. Atividade física, saúde e qualidade de vida: conceitos e sugestões para um estilo de vida ativo. Londrina: Midiograf; 2001.

8. Dreher DZ, Godoy LP. A qualidade de vida e a prática de atividades físicas: estudo de caso analisando o perfil do frequentador de academias. [anais]. XXIII Encontro Nacional de Engenharia de Produção. Ouro Preto: Enegep; 2003.

9. Minayo MCS, Hartz ZMA Qualidade de vida e saúde: um debate necessário. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2000; 5(1):7-31.

10. Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes. Diretrizes da Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes. Rio de Janeiro: SBD; 2008.

11. Silva DGV, Souza SS, Francioni FF, Mattosinho MMS, Coelho MS, Sandoval RCB et al. Pessoas com Diabetes mellitus: suas escolhas de cuidados e tratamentos. Rev Bras Enferm. 2006;59(3):297-302.

12. Bianchini DCS, Dell’Aglio DD. Processos de resiliência no contexto de hospitalização: um estudo de

Resear

15. Miranzi SSC, Ferreira FS, Iwawamoto HH, Pereira GA, Miranzi MAS. Qualidade de vida de indivíduos com Diabetes mellitus e hipertensão acompanhados por uma equipe de saúde da família. Texto & Contexto Enferm. 2008;17(4):672-79.

16. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Informe da Atenção Básica. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2001. 17. Otero LM, Zanetti ML, Teixeira CRS. Características sociodemográficas e clínicas de portadores de

diabetes em um serviço de atenção básica à saúde. Rev Latino-Am Enferm. 2007;15(esp):768-73. 18. Strawbridge WJ, Cohen RD, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Frequent attendance at religious services and

mortality over 28 years. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(6):957-61.

19. Jaffe DH, Eisenbach Z, Neumark YD, Manor O. Does living in a religiously affiliated neighborhood lower mortality? Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15(10):804-10.

20. Guimarães HP, Avezum A. O impacto da espiritualidade na saúde física. Rev Psiquiatr Clin. 2007;34 (1 Suppl):88-94.

21. Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Clarifying the relationship between religiosity and psychiatric illness: the impact of covariates and the specificity of buffering effects. Twin Res. 1999;2(2):137-44.

22. Moreira-Almeida A, Koenig HG. Retaining the meaning of the words religiousness and spirituality: a commentary in the WHOQOL SRPB groups a “cross-cultural study of spiritually, religion, and personal beliefs as components of quality of life”. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(4):843-5.

23. Sales CA, Tironi NM, D’Artibale EF, Silva MAP, Violin MR, Castilho BC. O cuidar de uma criança com Diabetes mellitus tipo 1: concepções dos cuidadores informais. Rev Eletrônica Enferm. 2009;11(3):563-72.

24. Lucchetti G, Lucchetti AG, Badan-Neto AM, Peres MF, Moreira-Almeida A, Gomes C et al. Religiousness affects mental health, pain and quality of life in older people in an outpatient rehabilitation setting. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43(4):316-22.

25. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of biomedical ethics. 7th ed. New York: Oxford; 2013.

26. Calvetti PU, Muller MC, Nunes MLT. Qualidade de vida e bem-estar espiritual em pessoas vivendo com HIV/Aids. Psicol Estud. 2008;13(3):523-30.

27. Lucchetti G, Granero A. Integration of spirituality courses in Brazilian medical schools. Med Educ. 2010;44(5):527.

28. Mariotti LG, Lucchetti G, Dantas MF, Banin VB, Fumelli F, Padula NA. Spirituality and medicine: views and opinions of teachers in a Brazilian medical school. Med Teach. 2011;33(4):339-40. 29. Moreira-Almeida A, Pinsky I, Zelanski M, Laranjeira R. Envolvimento religioso e fatores

sociodemográficos: resultados de um levantamento nacional no Brasil. Rev Psiquiatr Clin. 2010;37(1):12-5.

30. Oliveira GR, Neto JF, Salvi MC, Camargo SM, Evangelista JL, Espinha DCM et al. Health, spirituality and ethics: patients’ perceptions and comprehensive care. Rev Soc Bras Clin Med. 2013;11(2):140-4.

Participation of authors

Camila de Moura Leite Luengo was responsible for the study planning, data collection, statistical analysis and final writting of the article. Adriana Rodrigues dos Anjos Mendonça, was responsible for the orientation and final correction.

Received: 29.3.2014 Revised: 13.5.2014 Approved : 4.7.2014