93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 Literature

Sports participation and subjective well-being

Quality o li e and well-being have been analyzed through di erent points o view over time. During the last years, several studies have used the most diverse terms such as hap-piness and li e satis action when aiming to study the way people evaluate their own lives (Diener and Diener 1996). De initions o subjective well-being can be grouped into three domains (Diener 1984). During this study, the adopted de inition will be the one ormulated by social research, according to which subjective well-being depends on how and why individuals positively evaluate their lives, this is, individual’s li e satis action. his dimension has been attracting sociologists’ attention and stands out as the main indicator o well-being (Giacomoni 2004).

According to Diener et al. (1999, 277), subjective well-being is ‘a broad category o phe-nomena that includes people’s emotional responses, domain satis actions and global judg-ments o li e satis action’, which translates the individuals’ current assessment o their own happiness (Schwartz and Strack 1999).

It is worthy to mention three aspects o subjective well-being (Diener 1984): 1) well-being is subjective, depending on the individual’s perception and personal experience; 2) well-being implies not only the absence o negative actors, but also the presence o positive actors; 3) well-being must be seen as an overall measure rather than a measure o a single aspect o li e.

In what concerns the sports participation, the European Commission’s (2014) de inition o physical activity was adopted. here ore, physical activity was considered as any orm o physical activity that has been practiced in a sporting or related context, such as swimming, running outdoors, running at a gym or club, sports competitions etc.

An important share o the literature has ocussed on identi ying the sociodemographic and economic determinants o individuals’ subjective well-being (Dolan, Peasgood, and White 2008; Kahneman 1999; Scorsolini-Comin and Santos 2010) such as income, work situation, academic degree, gender and race.

However, in the sports ield, ew studies have attempted to examine whether physical and sporting activity impacts individuals’ overall well-being. Pawlowski, Downward, and Rasciute 2011) argue that practicing physical activity and sports is a personal and rational decision that maximizes an individual’s rational utility, and must there ore, be logically associated with increased subjective well-being. Results have shown convergence o positive and signi icate e ects o sports practice on subjective well-being: Becchetti, Pelloni, and Rossetti (2008) ound that sports participation in either type (i.e. collective and individual) increased subjective well-being; Lechner (2009) observed signi icant e ects o sports par-ticipation on men’s subjective well-being but not on women’s; Rasciute and Downward (2010) concluded that walking and recreational cycling had a p ositive e ect on individuals’ happiness; Downward and Rasciute (2011) veri ied di erent e ects on subjective well-being when sports practice involved a higher level o social interactions (team sports per ormed with partner) and higher monthly requency ; Moradi et al. (2014) highlighted that the requency and intensity o exercise exerted positive e ects on li e satis action; and Pawlowski, Downward, and R asciute (2011, 2014) observed that sports participation had a signi icant e ect on subjective well-being in all age groups, although its intensity varied throughout li etime. Q6 Q7 Q8 Q9 Q10

139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176 177 178 179 180 181 182 183 184

Surprisingly, weekly requency and duration have been neglected in previous studies (except Downward and Rasciute 2011; Moradi et al. 2014). However, these entail cost and e ort or individuals. hus, these elements might mediate the relationship between sports practice and subjective well-being.

From the discussion above, the ollowing is hypothesized:

H1: Sports participation, in terms o weekly requency and duration directly and posi-tively a ects subjective well-being.

Sports participation and the perceived value of elite sports

Attendance at sports events and sports participation makes citizens more aware and involved in sports. On the other hand, processing pieces o in ormation about sports leads to the development o an individual and subjective idea o what constitutes a country’s interna-tional sporting success.

Several methods might be used to measure international sporting success (Bernard and Busse 2004; Churilov and Flitman 2006). Each one o them entails limitations that are worth some attention. However, one o the most widespread ways to compare countries’ Olympic and sporting per ormance is through the Olympic Medals Index. Although the International Olympic Committee does not o icially recognize it as a hierarchic order, the importance o this index has signi icantly increased. It plays a major role in media and allows individuals to ormulate an opinion about the merit o sports policies and elite sports in their countries. Despite the mediatization o international sports results, Grix (2008, 408) argues that elite sports system has been ‘completely cut-o and separated rom everyday sport,’ which has led to a decreased acceptance o elite sports among ordinary citizens.

Having this in mind, do individuals with high levels o sports participation tend to attribute a higher value to their country’s elite sports? Or will these e ects be greater in sedentar y individuals or with a low level o sports participation?

he perceived value o elite sports recognizes individuals’ subjective views o what con-stitutes international sporting success, rather than previously determining its meaning. For instance, perceived value o elite sports was not particularly connected with a victory in any sporting event, but rather with an individual and global summary assessment about the value o the county’s elite sports in the international context.

According to previous discussion, it seems plausible that higher and more regular sports participation might lead to an increase on the perceived value o elite sports. hus, the

ollowing hypothesis is posited:

H2: Sports participation directly and positively a ects the perceived value o elite sports.

The perceived value of elite spor ts and subjective well-being

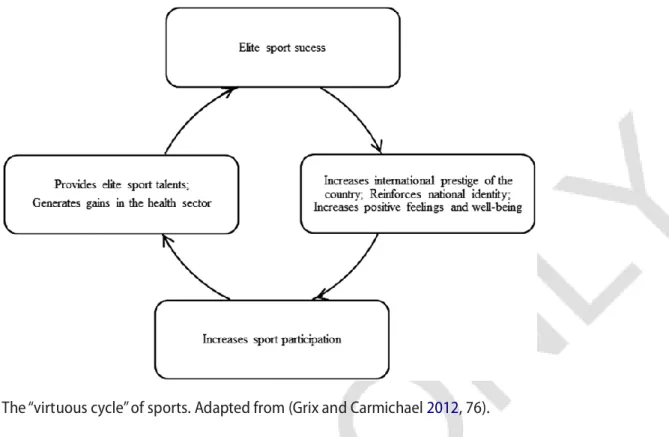

he investment philosophy o the so-called developed countries (UK, France, Australia) in elite sports is called ‘virtuous cycle’ (Grix and Carmichael 2012). According to this, elite sports’ success: 1) brings international prestige to the country ; 2) rein orces national identity ; 3) represents a actor o positive eelings and well-being; 4) promotes an increase in sports participation among the overall population, which ultimately; 5) leads to improvements in the health sector and provides a greater number o elite sports’ talents; consequently leading back to elite sports’ success, as shown in Figure 1.

185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208 209 210 211 212 213 214 215 216 217 218 219 220 221 222 223 224 225 226 227 228 229 230

In addition to the e ects on the sports system, the perceived success o athletes and teams in international competitions has been shown to impact eelings o national pride and international prestige (Allison and Monnington 2002). Likewise, it osters positive eelings among society members (Grix and Carmichael 2012).

Although this actor appears to be di icult to quanti y (DCMS/Strateg y Unit 2002), Downward and Rasciute (2010) argue that it seems to relate with interactions with riends about the event and with individual’s subjective well-being.

However, sporting success cannot be measured by the absolute number o medals a country won at the Olympics. For a country like Luxembourg with a population o 480,000 winning a single gold medal can be considered a success. For Germany with a population o 82 million it would represent a national sports’ crisis.

Few studies analyzed the e ect o sporting success on national pride and subjective well-being (Hallmann, Breuer, and Kühnreich 2013). Even so, results (e.g. Kavetsos and Szymanski 2010) showed that the success o national teams in the Olympics and in the major international ootball competitions (i.e. FIFA World Cup, UEFA European Championship) marginally a ected and only in the short-run, the reported happiness (sub-jective well-being).

Convergent with marginal e ects, Elling, Van Hilvoorde, and Van Den Dool (2014) ound that the perceived sporting success o Dutch athletes led to small short-term positive e ects on subjective well-being. However, Hallmann, Breuer, and Kühnreich (2013) veri ied that two-thirds o the Germans elt pride and happiness when their country’s athletes suc-ceeded in major competitions.

hese results do not provide clear evidence o the population’s positive eelings, as it is o ten claimed. Nevertheless, it has been highlighted that levels o national sporting per or-mance higher than expected tend to generate higher levels o subjective well-being, when compared with levels o per ormance aligned with the expected (Kavetsos and Szymanski 2010).

231 232 233 234 235 236 237 238 239 240 241 242 243 244 245 246 247 248 249 250 251 252 253 254 255 256 257 258 259 260 261 262 263 264 265 266 267 268 269 270 271 272 273 274 275 276

here ore, government interventions in the sports sector are substantial worldwide. In England, the goal o ‘sustainable improvement in success in international competition, par-ticularly in the sports which matter most to the public, primarily because o the “ eelgood

actor” associated with winning’ was suggested to the government (DCMS/Strategy Unit 2002). In Portugal, Major Planning Options or 2016–2019 re ers the goal o promoting sports as a orm o personal ul ilment, and highlights an objective ocussed on elite sports, aiming at supporting athletes and high-per ormance coaches, Olympic and Paralympic projects and high-per ormance sports participation (Lei no. 7-B/2016 2016, 1110).

Having as a background the discussion above, are the perceived results o elite sports actually having the desired e ects on citizens’ subjective well-being, as believed by many politicians? Is it plausible that the perceived value o elite sports could lead to an increase in individuals’ subjective well-being? he ollowing hypothesis is there ore put orward:

H3: Te perceived value o elite sports directly and positively a ects the subjective well-being.

Methods

Data rom 567 Portuguese (67% emale, 33% male) college students was collected. he survey was conducted in June 2016. Participants were recruited using a convenience sam-pling technique. Participants were sent an email containing a link to an online questionnaire.

he response rate was 17.7%. From the respondents, 511 were considered suitable, o which 67.4% were emale and 32.6% male. Marital status ranged rom single (85.1%), married (13.6%) and divorced or widow 1.3%. he mean age was 25.1 ± 9.74 years.

he questionnaire contained queries about the theoretical concepts underlying this study. Respondents were in ormed o anonymity and con identially be ore data collection.

Respondents were questioned about variables such as the perceived value o elite sports (Consejo Superior de Deportes 2011); physical activity (Downward and Rasciute 2011); and subjective well-being (Simões et al. 2003). hese were measured according to what was previously done in other studies. Sociodemographic details such as age, gender, marital status, residential region and enrolled academic institution were also asked. An over view o the variables is provided in able 1.

Data analysis

Structural Equation Modelling (Arbuckle 2007) was used or analyzing the plausibility o the theoretical and conceptual model. he usage o such technique requires the ul ilment o a set o assumptions, such as the sample size (n = 511), in order to ensure su icient vari-ability to estimate the model parameters.

o test the hypothetical associations between the present variables in the model, which identi ies the sources o possible unacceptable adjustment o the general model, the recom-mendations o two steps by Anderson and Gerbing (1988) were adopted. he irst step was to evaluate the quality o the measurement sub-models, o the constructs present in the global model. he second step was to evaluate the quality o the adjustment o the structural model. First, the overall assessment was carried out through the selected adjustment indexes. Second, the parameters leading to test the ormulated hypotheses were estimated.

277 278 279 280 281 282 283 284 285 286 287 288 289 290 291 292 293 294 295 296 297 298 299 300 301 302 303 304 305 306 307 308 309 310 311 312 313 314 315 316 317 318 319 320 321 322 Multi-group analysis

In order to test invariance between male and emale, a multi-group analysis was per ormed, ollowing recommendations o several authors (Byrne 2010; Cheung and Rensvold 2002), namely : 1) measurement model should represent a good it in each o the groups; 2)

con-igural, metric, scalar and residual should be examined. Invariance assumptions were ver-i ver-ied through the dver-i erences o CFI (ΔCFI ≤ 0.01) in line with Cheung and Rensvold (2002).

Results

Preliminary analysis

A preliminary data analysis demonstrated that non-respondents accounted or <0.1%, with-out showing any type o pattern. here ore, data were imputed using regression procedures o AMOS. Descriptive analysis revealed no violations o the univariate distribution since Skewness and Kurtosis were contained between –2, +2 and –7 + 7 (Byrne 2010). However, Mardia coe icient exceeded the expected value or multivariate normality (>5.0). hus, a

Q11 Q12

Table 1. Va abl d a d m asu m .

Va abl D s S al S u s p v d valu l s s (pV ) cu l , h a all s p ugu s h gh- m s s: (1 = ex m l bad, 2 = V , 3 = Bad, 4 = Fa , 5 = G d, 6 = V g d, 7 = ex m l g d); o d al c s j Su d D s (2011) A d l k g bak 10 a s ag , h a all s p ugu s s s m s: (1 = ex m l w s ha 10 a s ag ; 2 = Muh w s ; 3 = W s ; 4 = equal ; 5 = B s ; 6 = Muh b ; 7 = ex m l b ha 10 a s ag ) ph s al a v (pA) i las m h h w d d u x s d la d s ? (1 = n v ; 2 = h m s a m h; 3 = w m s a w k; 4 = h u m s a w k; 5 = v m m s a w k). M D w wa d a d ras u (2011) i g al, h w mu h m al d u usuall s d v g us h s al a v ? (1 = i v d v g us h s al a v s; 2 = 30 m u s l ss; 3 = 31–60 m u s; 4 = 61–90 m u s; 5 = 91–120 m u s; 6 = >120 m u s). M Subj v w ll-b g (SWB) Sa s a w h L S al : ov all, i am sa s d w h m l . (0 = n a all sa s d 10 = ex m l sa s d) o d al S mõ s al. (2003)

S x (1 = F mal ; 2 = Mal ) Dumm

Ag Ag a s M Ma ag S a us (1 = S gl ; 2 = Ma d; 3 = D v d; 4 = c s sual u ; 5 = W d w) r a g r s d al g (1 = n h, 2 = c , 3 = L sb a d tj Vall , 4 = Al j , 5 = Alga v , 6 = Az s, 7 = Mad a) r a g Aad m du a nam h a ad m s u r a g

323 324 325 326 327 328 329 330 331 332 333 334 335 336 337 338 339 340 341 342 343 344 345 346 347 348 349 350 351 352 353 354 355 356 357 358 359 360 361 362 363 364 365 366 367 368 Table 2. M a , SD, a d a l ad gs. c s u s ms M a SD Fa l ad gs PA 2.95 1.16 pA1 – H w d u x s la s ? ( las m h). 2.82 1.27 .62** pA2 – 1. H w d u x s la s ? ( las m h). 3.09 1.29 .62**

The perceived value of elite sports 4.99 .961 pV1 – cu l , h a al x , h s p ugu s h gh- m s s. 5.38 1.14 .60** pV2 – A d la v l 10 a s ag , h a al x , gl ball , h s p ugu s h gh m s s. 4.60 1.22 .55** Subjective well-being SWB1 – ov all, i am sa s d w h m l 8.15 1.90 .85** Q21

Bollen-Stine Bootstrap o 2000 samples was used or the subsequent analysis. he results o the measurement model are presented in able 2.

Results from SEM

It has been ound: 1) a positive and signi icant e ect between sports participation and subjective well-being (β = .25, IC90% = .121 –.371, p = .002); 2) a positive and signi icant e ect between the perceived value o sports and subjective well-being (β = .36, IC90% .239–.500, p = .001); and lastly, 3) a positive but not signi icant e ect between sports par-ticipation and perceived value o sports (β = .01, IC90% = –.169–.166, p= .962), as shown in the Figure 2. he model had acceptable it [χ

2

= 18.342, d = 6, B-S p = .005, LI = .944, CFI = .966, RMSEA = .064, 90% (IC .032–.098)].

Multi-groups analysis

Results showed that the model is invariant between gender. Concretely, the data it the measurement model in each group: male, vχ

2

= 9.839 (6), B-S p = .198, LI = .945, CFI = .967, SRMR = .047, RMSEA = .063 (CI = .000, .130)]; emale, [χ

2

= 8.507 (6), B-S p =.155, LI = .981, CFI = 989, SRMR = .028, RMSEA = .035 (CI = .000, .084)]. In addition, invari-ance was achieved since the chi-square test did not present di erences between the ree model (i.e. unconstrained model) and the other models: structural weights (χ

2

= 5.40; d = 8; p =.714), measurement residuals (χ

2

= 5.40; d =9; p =.798). Results show that struc-tural weights and model’s measurement errors are equivalent between gender (p > .05). Hence, it is reasonable to assume that any interpretation to be drawn rom the relations among the studied variables has the same hypothetical e ect between men and women, as observed in able 3.

Hypothesis test

Sports par ti cipation exerte d a positive an d signi icant e ect on subjective well- being (ß = .25, p < .005) , there ore con irmi ng H 1. Spor ts participation ha d a positive but Q13

Q14

369 370 371 372 373 374 375 376 377 378 379 380 381 382 383 384 385 386 387 388 389 390 391 392 393 394 395 396 397 398 399 400 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409 410 411 412 413 414

non-signi icant predictive action on the perceived value o elite sports (ß = .01, p < .962), hence not sustaining H2. he perceived value o elite sports exerted a positive and signi icant e ect on subjective well-being (ß = .36, p < .001), thus supporting H3, as shown in able 4.

Findings support 2 o the 3 ormulated hypothesis and present three main results: 1) Sports participation positively a ects the individual’s subjective well-being; 2) Perceived value o elite sports positively a ects the individual’s subjective well-being; 3) Sports par-ticipation does not signi icantly a ect the perceived value o elite sports.

Results and discussion

Sports participation and subjective well-being

One purpose o this study was to show the causal relations between sports participation and individuals’ subjective well-being. Promotion and widening o physical activity as an instrument or improving physical condition, li e quality and health o citizens has caught

Figure 2. S a da d z d a am s h s u u al m d l ( = 511). Table 3. G d ss- - d x s m asu m va a b w g d . M d ls χ² d Δχ² Δd p ci 18.358 12 – – – Mi 23.758 20 5.400 8 .714 Si 23.764 21 5.406 9 .798 ci: gu al va a ; Mi: m va a ; Si: S u u al

i va a . Table 4. S a da d z d f s h s u u al m d l subj v w ll-b g ( = 511). H H h s s/ a hwa c ma S a da d z d aj f (ß) H1: S a a → Subj v w ll-b g y s .25* H2: S a a → p v d valu l s s n .01 s H3: th v d valu l s s → Subj v w ll-b g y s .36** n : * p < .05; ** p < .001 ; s: s g a .

415 416 417 418 419 420 421 422 423 424 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432 433 434 435 436 437 438 439 440 441 442 443 444 445 446 447 448 449 450 451 452 453 454 455 456 457 458 459 460

the attention o several international organizations and national governments. Research has shown that certain variables o sports participation are important predictors o indi-viduals’ subjective well-being (Becchetti, Pelloni, and Rossetti 2008; Downward and Rasciute 2011; Lechner 2009; Moradi et al. 2014; Pawlowski, Downward, and Rasciute 2011; 2014; Rasciute and Downward 2010; Ruseski et al. 2014; Wiese, Kuykendall, and ay 2018).

he irst result to be highlighted is the positive and signi icant e ect o weekly requency and duration o practicing vigorous physical activity on individuals’ subjective well-being. his result clearly con irms what has been previously veri ied by Downward and Rasciute (2011) and Moradi et al. (2014), who claimed that physical activity’s requency and duration have a positive e ect on subjective well-being and li e satis action.

here ore, it was concluded that higher weekly requency and longer duration led to higher levels o individuals’ subjective eeling o well-being. hese results are in line with Pawlowski, Downward, and Rasciute (2011), who argue that physical activity practice is rational and there ore, per ormed in a positive and avourable way.

Sports participation and the perceived value of elite sports

he second objective o this study was to identi y the e ects o sports participation on the perceived value o elite sport. Governments’ investment philosophy o many socalled devel -oped countries in elite sport is labelled ‘virtuous cycle’, through which the success o the elite sports, among other bene its, brings international prestige to the countr y and contrib-utes to positive eelings and well-being (Grix and Carmichael 2012). On the other hand, Grix (2008) de ends that the elite sporting system was ‘completely cut-o and separated rom everyday sport’, which has led to a decline in public acceptance o governments’ high investments in elite sports.

Results seem to converge with this idea, having shown that sports participation did not signi icantly a ect the perceived value o elite sports. hat is, results do not con irm any position. It was not possible to veri y whether individuals who mani ested higher sports participation assigned a signi icantly higher value or, conversely, a lower value to their country’s elite sports.

It is concluded that sports participation does not impact the perceived value o elite sports. his may be due to two reasons: 1) the physical e ort and increased sports practice did not in luence the way people evaluate their countr y’s athlete’s achievements; and 2) the country’s sporting achievements may be so irrelevant that are not perceived as valuable.

The perceived value of elite spor ts and subjective well-being

It was intended to determine the extent to which the perceived value o elite sports in luences individual’s subjective well-being. Research has shown that athletes and sports teams’ inter-national success impacts eelings o inter-national pride and interinter-national prestige (Allison and Monnington 2002), ostering a positive sensation among the population (Grix and Carmichael 2012) and individuals’ subjective well-being (e.g., Downward and Rasciute 2010). Governments use this ‘ eelgood actor’ a ter sporting success as a way to justi y investments in elite sports (DCMS/Strategy Unit 2002).

Findings signi icantly con irmed the belie that the greater the perceived value o a country’s elite sports, the greater the individuals’ subjective well-being. Elling, Van Hilvoorde, and Van

461 462 463 464 465 466 467 468 469 470 471 472 473 474 475 476 477 478 479 480 481 482 483 484 485 486 487 488 489 490 491 492 493 494 495 496 497 498 499 500 501 502 503 504 505 506

Den Dool (2014) observed that the perceived sports success o Dutch athletes led to small positive e ects on subjective well-being in the short-term. In addition, Hallmann, Breuer, and Kühnreich (2013) pointed out that German nationals’ eelings o happiness were increased when German athletes were success ul in major international competitions. Our results are aligned with the ones o these studies, providing evidence that the perceived value o elite sports o ones’ country positively and signi icantly in luences individuals’ subjective well-being. However, other studies ound contrary results. Pawlowski, Downward, and Rasciute (2014) ound that the pride o international sporting success did not show direct results on increased subjective well-being. Kavetsos and Szymanski (2010) ound that sporting success positively in luenced national pride, but that national pride did not in luence the subjective perception o well-being.

Despite these opposed indings, our results seem to legitimize governments’ strong investment policies in elite sports, supported by the e ect o the so-called ‘virtuous cycle’ (Grix and Carmichael 2012). Besides stimulating sports participation, this ‘virtuous cycle’ positively impacts the perception o the countr y’s elite sports value, subsequently leading to the development o eelings o well-being.

Conclusion

his work contributed to an emerging body o literature, centred on the e ects o sports participation in the perceived value o elite sports and individual’s well-being. Results allow to draw three conclusions:

First, citizens’ sports participation, in terms o requency and volume, was shown to positively and directly a ect individual’s subjective well-being, according to participants’ sel -report o how satis ied they eel with their lives.

Second, this study provides evidence that the perceived value o elite sport is important in society. Results show that the perceived value o elite sport has a positive impact on individuals’ subjective well-being.

hird, no evidence was ound that higher levels o sports participation directly a ect the value attributed to one’s country elite sport.

Theoretical implications

Results introduce two particular theoretical implications that need to be highlighted. First, our study rein orces the idea that higher sports participation (i.e. weekly requency and training volume) acts on subjective well-being, strengthening the existing knowledge. Second, the theoretical linkage established between the perceived value o elite sports and subjective well-being will allow extending the research on international sports success, on the perceived value o elite sports and on the individuals’ subjective well-being.

Managerial implications

hese results entail two main outcomes or sports policymakers and or managers respon-sible or the development o physical activity and sports programmes.

First, these results support the growing amount o public policies that look or promoting sports practice generalization. Findings sustaining that sports participation increases sub-jective well-being provide support or many governments’ policies ocussed on augmenting

507 508 509 510 511 512 513 514 515 516 517 518 519 520 521 522 523 524 525 526 527 528 529 530 531 532 533 534 535 536 537 538 539 540 541 542 543 544 545 546 547 548 549 550 551 552

sports participation among the overall population. his suggests that public in ormation campaigns praising the various bene its o sports participation, including improved health, can be an e ective political tool to boost subjective well-being. A political decision that promotes a greater balance in the allocation o resources and shows an evident increase in unding or the objectives o a clear improvement o the sporting participation o the entire population. A unding that balances with the high amounts intended or the preparation o elite athletes. he ollowing principle holds: Few resources can bene it many people, while ew people bene it rom many resources. In order to increase individuals’ subjective well-being, governments should be encouraged to design sports participation public policies and programmes ocussed on two targets: 1) sedentar y population, in order or these to initiate sports practice and, there ore, improve levels o subjective well-being and; 2) low-in-tensity sports participants, ocussed on the increase o training requency and duration, which has been demonstrated to contribute to increase levels o subjective well-being.

On the other hand, results also hig hlight the need o rein orcing certain policies targeting elite sports. his issue is extremely important since results showed that the e ect o sports participation on subjective well-being was surprisingly lower than the perceived value o elite sports on subjective well-being. For instance, since the 2012 Olympics success, the UK has increased its unding or preparing the 2016 Olympics by 11%. In contrast, unding or recreational sports participation is under enormous pressure (Downward and Rasciute 2010).

All in all, this inding provides solid ground or governments and managers o sports programmes to adequately manage public resources, whether or elite sports or or recre-ational sports participation. In addition, inancing nrecre-ational sports teams and elite athletes can be considered as a political tool or raising individuals’ subjective well-being, which had already been stressed by Hallmann, Breuer, and Kühnreich (2013), who encouraged politicians to be aware that sporting success obtained in international competitions can bene it happiness o all segments o the population.

his relation is o particular interest or governors and policymakers, who are advised to consider the importance o the value o elite sports when making decisions and ormu-lating national strategies involving investment in elite sports. hus, governments are rec-ommended to work on the development o sport policies targeting elite sports, providing

unds to support national teams and elite athletes who show strong potential to achieve international sporting success. By doing so, the perceived value o elite sports will increase, because individuals tend to reach a higher level o subjective well-being. On the other hand, governments can act on the perception o sports value, developing consistent communica-tion campaigns that point out genuine sporting achievements, leading to an increase in subjective well-being. Policies aiming at supporting high-per ormance athletes and coaches and the increase in the inancial support or the Olympics and Paralympics in Portugal seem to ind rational ground in the act that the perceived value o elite sports develops

eelings o subjective well-being.

Limitations

As in any investigation, this study has a set o limitations. One limitation was that the model considered only individual determinants o subjective well-being and did not consider macro-level data. On the other hand, the size o the sample, the larger number o women and the average age o 25 might have in luenced the results. Neither age nor levels o

553 554 555 556 557 558 559 560 561 562 563 564 565 566 567 568 569 570 571 572 573 574 575 576 577 578 579 580 581 582 583 584 585 586 587 588 589 590 591 592 593 594 595 596 597 598

education o the sample were analyzed. However, studies show that socioeconomic actors may have had an e ect on the obtained results.

Future research

Additionally, it would be interesting to evaluate a more gender balanced sample and to extend the research to other representative age groups. Future research ocussed on the analyzed constructs should ail to consider the deeper study o the relation between sports participation and the perceived value o elite sports. It is suggested that this topic should be looked on more in detail, since marginal, but not signi icant, positive e ects were ound. Additionally, it would be interesting to evaluate a more gender equilibrated sample, to extend the research to other representative age groups and to control the e ects o the socio-economic actor o individuals. Future research in the ield o sporting success enhancement can still ocus on cross-countr y and socio-demographic segments compari-sons, since each sport national importance might di er among distinct countries (e.g.

ootball in Portugal and soccer in the USA). he way sports participation a ects subjective well-being is still uncertain in the literature and is an important area or uture research.

Finally, as argued by Pawlowski, Downward, and Rasciute (2011), policymakers have been recognizing the importance o subjective well-being as a target o public policies, since this enables them to direct these policies towards actors that e ectively increase citizens’ subjective well-being eelings.

Disclosure statement

No potential con ict o interest was rep orted by the authors.

ORCID

Pedro Sobreiro http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3971-3545

References

Allison, L., and . Monnington. 2002. “Sport, Prestige and International Relations.” Government and Opposition 37 (1): 106–134. doi:10.1111/1477-7053.00089

Anderson, J., and D. Gerbing. 1988. “Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended wo-Step Approach.” Psychological Bulletin 103 (3): 411–423. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

Arbuckle, J. 2007. Amos 16.0 User’s Guide. Chicago: SPSS. Accessed 26 February 2014. http:/www. amosdevelopment.com/download/Amos%2016.0%20User’s%20Guide.p d

Becchetti, L., A. Pelloni, and F. Rossetti. 2008. “Relational Goods, Sociability, and Happiness.” Kyklos 61 (3): 343–363. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6435.2008.00405.x

Bernard, A., and M. Busse. 2004. “Who Wins the Olympic Games: Economic Resources and Medal otals.” Te Review of Economics and Statistics 86 (1): 413–417. doi:10.1162/003465304774201824

Churilov, L., and A. Flitman. 2006. “ owards Fair Ranking o Olympics Achievements: Te Case o Sydney 2000.” Computers & Operations Research 33 (7): 2057–2082. doi:10.1016/j.cor.2004.09.027

Consejo Superior de Deportes. 2011. Encuesta sobre los hábitos deportivos en España 2010. Accessed 9 February 2017. http://www.csd.gob.es/csd/estaticos/dep-soc/encuesta-habitos-deportivos2010.pd

599 600 601 602 603 604 605 606 607 608 609 610 611 612 613 614 615 616 617 618 619 620 621 622 623 624 625 626 627 628 629 630 631 632 633 634 635 636 637 638 639 640 641 642 643 644

DCMS/Strategy Unit. 2002. Game Plan: A Strategy for Delivering Government’s Sport and Physical Activity Objectives. London: Cabinet O ce.

Direção Geral da Saúde. 2016. Estratégia Nacional Para a Promoção da Atividade Física, da Saúde e Do Bem-Estar. Lisboa: DGS.

Dolan, P., . Peasgood, and M. White. 2008. “Do we Really Know What Makes us Happy? A Review o the Economic Literature on the Factors Associated with Subjective Well-Being.” Journal of Economic Psychology 29 (1): 94–122. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2007.09.001

Downward, P., and S. Rasciute. 2010. “Te Relative Demands or Sports and Leisure in England.” European Sport Management Quarterly 10 (2): 189–214. doi:10.1080/16184740903552037

Downward, P., and S. Rasciute. 2011. “Does Sport Make You Happy? An Analysis o the Well‐Being Derived rom Sports Participation.” International Review of Applied Economics 25 (3): 331–348. doi:10.1080/02692171.2010.511168

Elling, A., I. Van Hilvoorde, and R. Van Den Dool. 2014. “Creating or Awakening National Pride through Sporting Success: A Longitudinal Study on Macro E ects in Te Netherlands.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 49 (2): 129–151. doi:10.1177/1012690212455961

Forrest, D., and S. Robert. 2003. “Sport and Gambling.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 19 (4): 598–611. doi:10.1093/oxrep/19.4.598

Grix, J. 2008. “Te Decline o Mass Sport Provision in the German Democratic Republic.” Te International Journal of the History of Sport 25 (4): 406–420. doi:10.1080/09523360701814755

Grix, J., and F. Carmichael. 2012. “Why Do Governments Invest in Elite Sport? A Polemic.” International Journal of Sport Policy and Politics 4 (1): 73–90. doi:10.1080/19406940.2011.627358

Hallmann, K., C. Breuer, and B. Kühnreich. 2013. “Happiness, Pride and Elite Sporting Success: What Population Segments Gain Most rom National Athletic Achievements?” Sport Management Review 16 (2): 226–235. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2012.07.001

Kahneman, D. 1999. “Objective happiness.” In Wellbeing: Foundations of Hedonic Psychology, edited by Kahneman, Daniel, Diener, Ed ward, and Schwarz, Norbert, 3–25. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Press.

Kavetsos, G., and S. Szymanski. 2010. “National Well-Being and International Sports Events.” Journal of Economic Psychology 31 (2): 158–171. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2009.11.005

Lechner, M. 2009. “Long-Run Labor Market and Health E ects o Individual Sp orts Activities.” Journal of Health Economics 28 (4): 839–854. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.05.003

Lei no 7-B/2016 de 31 de março da Assembleia da República. 2016. Diário da República: I série, No 63. Acedido a 24 Januar y 2010. Accessed 10 September 2017. www.dre.pt

Moradi, S., A., Nima, M. R. Ricciardi, . Archer, and D. Garcia. 2014. “Exercise, Character Strengths, Well-Being, and Learning Climate in the Prediction o Per ormance over a 6-Month Period at a Call Center.” Frontiers in Psychology 5: 1–11. doi:10.3389/ psyg.2014.00497

Onusic, L., and W. Mendes-da-Silva. 2015. “Orgulho de Ser Brasileiro Impacta o Nível de Felicidade?” Revista de Administração Contemporânea 19 (6): 712–731. doi:10.1590/1982-7849rac20151488

Pawlowski, ., P. Downward, and S. Rasciute. 2011. “Subjective Well-Being in European countries – On the Age-Specifc Impact o Physical Activity.” European Review of Aging and Physical Activity 8 (2): 93–102. doi:10.1007/s11556-011-0085-x

Pawlowski, ., P. Downward, and S. Rasciute. 2014. “Does National Pride rom International Sporting Success Contribute to Well-Being? An International Investigation.” Sport Management Review 17 (2): 121–132. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2013.06.007

Porsche, M., and W. Maennig. 2008. “Te Feel-Good E ect at Mega Sports Events. Recommendations or Public and Private Administration In ormed by the Experience o the FIFA World Cup 2006.” Economic Discussions 18: 1–27. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1541952

Rasciute, S., and P. Downward. 2010. “Health or Happiness? What Is the Impact o Physical Activity on the Individual?” Kyklos 63 (2): 256–270. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6435.2010.00472.x

Ruseski, J., B. Humphreys, K. Hallman, P. Wicker, and C. Breuer. 2014. “Sp ort Participation and Subjective Well-Being: instrumental Variable Results rom German Survey Data.” Journal of Physical Activity and Health 11 (2): 396–403. doi:10.1123/jpah.2012-0001

Scorsolini-Comin, F., and M. A. D. Santos. 2010. “O Estudo Científco da Felicidade e a Promoção da Saúde: revisão Integrativa da Literatura.” Revista Latino Americana de Enfermagem 18 (3): 472–479. doi:10.1590/S0104-11692010000300025

Q17

645 646 647 648 649 650 651 652 653 654 655 656 657 658 659 660 661 662 663 664 665 666 667 668 669 670 671 672 673 674 675 676 677 678 679 680 681 682 683 684 685 686 687 688 689 690

Simões, A., J. Ferreira, M. Lima, M. Pinheiro, C. Vieira, A. Matos, and A. Oliveira. 2003. “O Bem-Estar Subjectivo Dos Adultos: Um Estudo ransversal.” Revista Portuguesa de Pedagogia 37 (1): 5–30.

Van Hilvoorde, I., A. Elling, and R. Stokvis. 2010. “How to In uence National Pride? Te Olympic Medal Index as a Uni ying Narrative.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 45 (1): 87– 102. doi:10.1177/1012690209356989

Van Praag, B., and P. Frijters. 1999. “Te measurement o wel are and well-being: the Leyden ap-proach.” In Wellbeing: Foundations of Hedonic Psychology, Kahneman, Daniel, Diener, Ed, and Schwarz, Norbert, 413–432. New York: Russell Sage Foundation Press.

Wicker, P., J. Prinz, and . von Hanau. 2012. “Estimating the Value o National Sporting Success.” Sport Management Review 15 (2): 200–210. doi:10.1016/j.smr.2011.08.007

Wiese, C., L. Kuykendall, and L. ay. 2018. “Get Active? a Meta-Analysis o Leisure- ime Physical Activity and Subjective Well-Being.” Te Journal of Positive Psychology 13 (1): 57–66. doi:10.1080 /17439760.2017.1374436

World Health Organization. 2013. Te European Health Report 2012: Charting the Way to Well-Being. Copenhagen: WHO. Accessed 15 September 2017. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/ assets/pd _fle/0004/197113/EHR2012-Eng.pd

Q19