e-ISSN 1807-0191, p. 316-333 OPINIÃO PÚBLICA, Campinas, vol. 23, nº 2, maio-agosto, 2017 Mario Fuks

Gabriel Avila Casalecchi

Mateus Morais Araújo

Introduction

Since the publication of Critical citizens (1999), the term “critical citizen” has achieved prestige in debates about political legitimacy. The book was a response to the apparent contradiction posed within consolidated democracies by the coexistence of growing dissatisfaction and distrust regarding political institutions and the continuation of strong support for the democratic system. In a period of distrust and dissatisfaction with its institutions, how has democracy spread around the world?

Differently from those who advocated a crisis of democracy (Crozier, Huntington, and Watanuki, 1975), Norris (1999) argued that modernization, particularly rising levels of education, favors the emergence of a more demanding and radically democratic citizen critical of the current democratic regimes. The critical citizen is dissatisfied with the performance of the political system and distrusts traditional representative institutions. Nevertheless, he or she is committed to the principles of democracy and engaged with politics. Far from bringing instability to democracies, the emergence of critical citizens contributes to achieving democratic improvements.

MARIO FUKS; GABRIEL AVILA CASALECCHI; MATEUS MORAIS ARAÚJO

Throughout Critical citizens, the term is treated as synonymous with the concept of the “dissatisfied democrat”. However, there is little empirical evidence for this relationship at the level of individual data. It is unknown whether citizens who adhere to democracy and are simultaneously dissatisfied with it are the same as those who display critical attitudes and behaviors by demanding more of the political regime and its institutions.The danger of this association lies in assuming that dissatisfied democrats are necessarily good for democracy, especially in the context of new democracies. We may suppose, especially in unstable political and economic contexts, that dissatisfied democrats are, in fact, politically apathetic citizens or even predisposed to agree to authoritarian measures (Doorenspleet, 2012).

This article seeks to contribute to the clarification of these issues. The first step in this direction is the development of a definition of “critical”. We understand the critical individual to be one who is informed and uses this information to assess political reality. Based on this analytical distinction, the relationship between criticism and dissatisfaction is no longer a mere theoretical assumption, but a hypothesis that should be tested. The first question to consider in this regard is the following: are critical citizens indeed the same as dissatisfied democrats? That is, are individuals who are more critical also less satisfied with the democracies in which they live?

To answer this question, we propose a clear distinction between these two types of citizens: the “dissatisfied democrat” and the “critical democrat”. The former refers to citizens who support democracy but are, at the same time, dissatisfied with their respective regime. The latter combines support for democracy and cognitive mobilization (Dalton, 2013), an indicator based on education level and political interest that expresses the necessary resources for a critical stance.

The second question to be answered is which of these two types of citizens displays behaviors and attitudes that are more consistent with the citizen profile originally characterized by Norris as “critical”. To move forward on this issue, the present article examines the effects of each type of citizen, and the interaction of both, on both political participation and democratic attitudes.

To test our argument, we compare data from the Americas Barometer1 about two different countries: Brazil (a new democracy) and the United States (an old democracy)2. As said before, for Norris, the emergence of the critical citizen is a phenomenon typical of old democracies. This means that more studies will be needed to see if it also applies to younger democracies. Since the United States is one of the oldest democracies in the world, and Brazil, on the other hand, is among the newest democracies, the comparison between

1 We thank the Latin American Public Opinion Project (Lapop) and its major supporters (the United States

Agency for International Development, the Inter-American Development Bank, and Vanderbilt University) for making the data available.

2 1,500 people were interviewed in the United States and 2,482 in Brazil, all selected from a probabilistic

these countries should be enough not only to test if critical citizens’ behavior is the same in old and new democracies, but also, to test at the same time our main claim, that critical citizens are not necessarily dissatisfied democrats. We believe this will illuminate some key problems new democracies face.

This article is developed in four sections. In the first section, we present the debate over the critical citizen. The second section discusses the definition of the concepts used and the way they will be empirically operationalized. In the last two sections, we present our research results: the third section evaluates whether the profiles of dissatisfied democrats and critical citizens correspond to the same individuals, and the fourth section analyzes the propensity of each type of citizen to participate in protests and adopt attitudes in defense of democracy in Brazil and the United States.

The concept of the “critical citizen”

In recent years, several studies on political culture have called attention to an allegedly paradoxical situation: although citizens are increasingly dissatisfied with the performance of democratic regimes and distrustful of their institutions, the stability of most democracies worldwide has not been shaken (Klingemann and Fuchs, 1995; Klingemann, 1999; Dalton, 1999, 2004; Inglehart, 1999; Inglehart and Welzel, 2005; Norris, 2011). This paradox has been noticed not only in old democracies, but also in new ones, including those in Latin America (Booth and Seligson, 2009; Salinas and Booth, 2011; Carlin, Singer and Zechmeister, 2016), Africa (Bratton and Mattes, 2001; Doorenspleet, 2012) and Asia (Dalton and Shin, 2006).

Research in the 1970s observed a decline in citizen satisfaction and confidence in government and representative institutions (Miller, 1974). This fall was considered by scholars to be symptomatic of an imminent crisis of democratic regimes. According to Crozier, Huntington and Watanuki (1975), the expansion of democracies would have paradoxically caused a problem in the ability of regimes to meet the demands of various groups involved in decision-making and political participation processes. Democracies were suffering from a “crisis of governability” and were subject to instability because they were unable to meet citizens’ demands.

It did not take long for this prognosis to be contested (Klingemann and Fuchs, 1995). Surveys conducted throughout the 1980s relativized the existence of a single, inflexible pattern of decline in satisfaction and trust worldwide, suggesting that significant fluctuations occur at different times and in different regions. As stated by Klingemann and Fuchs (1995), democracies are more malleable than previously thought, adapting to new demands so that, despite dissatisfaction and distrust, most citizens continue to support democratic principles.

MARIO FUKS; GABRIEL AVILA CASALECCHI; MATEUS MORAIS ARAÚJO

Norris (1999). The main argument of the book is that growing dissatisfaction and distrust were associated with the emergence of the “critical citizen”.

Based upon a multidimensional model of political legitimacy, she argued that “citizens seem to distinguish between different levels of the system” (p. 9). Given these multiple dimensions, what seems to be a paradox could be explained by the emergence of a citizen who was more critical and more dissatisfied with government and institutions but who, at the same time, considered democracy to be the best form of government. Far from putting the system at risk, this “critical citizen” or “dissatisfied democrat” could even contribute to its improvement.

Despite its theoretical elegance, the concept of the “critical citizen” was not fully clarified. Applying the concept of critical citizen in the African context, Doorenspleet (2012) makes an important observation:

On the basis of previous studies, critical citizens can be defined as dissatisfied

democrats. Problematic, however, is that the language of the definition implies an important hidden assumption: it is simply assumed that dissatisfied democrats are ‘critical’ (...) In other words, critical citizens are not only critical, dissatisfied democrats, but also well-informed, interested, and involved people who want to improve the functioning of their political system.

This idea that criticism is an indicator of a healthy stable democracy has now

become widely accepted. As a consequence, scholars have emphasized the possible positive impact of dissatisfied democrats for the strengthening of

democracy around the world. However, we do not know whether dissatisfied

democrats are critical or not, and it is not wise to make this assumption beforehand. We need to disentangle these concepts, and define them

separately (Doorenspleet, 2012, p. 282).

In fact, Norris (1999) links the emergence of the critical citizen to the context of modernization and increase of educational levels. In this sense, this concept can be broken down into three fundamental elements: (1) commitment to democracy; (2) dissatisfaction with the performance of the regime; and (3) cognitive skills. Therefore, Norris assumes that the critical citizen—at once committed to democracy as a form of government, and dissatisfied with the performance of political institutions—is a cognitively mobilized citizen. However, we strongly agree with Doorenspleet’s claim that these elements should be tested separately. In other words, from an empirical and analytical point of view, it is very important to distinguish dissatisfaction from cognitive skills.

information and the propensity to vote. The results were that satisfied democrats were more likely to take an interest in politics and to vote in the next election than were dissatisfied democrats (Doorenspleet, 2012, p. 289).

Doorenspleet’s (2012) study shows the need for further research on the topic, especially in new democracies marked by economic instability and recent experiences with an authoritarian regime (Moisés, 1995, 2008; Diamond, 1994; Mishler and Rose, 1999, 2001; Torcal and Monteiro, 2006; Bratton and Mattes, 2001). The author emphasized the coexistence, in some African countries, of high percentages of dissatisfied democrats and political instability. Senegal, for instance, changed from a “free country” to a “partly free country”, as specified by the Freedom House index.

There are, however, some important limitations to Doorenspleet’s work. Despite her concern with the concept of “critical”, Doorenspleet (2012) does not develop an empirical model for this type of citizen. Thus, the author shows that dissatisfied democrats are not always critical, but she does not explain which of these conditions—dissatisfaction or criticism—really matters for the formation of democratic attitudes and behavior. This article proposes a key step in that direction through the construction of a typology that combines support for democracy with a critical stance and that can be compared with the profile of the dissatisfied democrat derived from Norris’s (1999) theory.

The fundamental question that we raise here is what makes a citizen a “critical citizen” and how can we identify this quality empirically. Norris (1999) is unclear in this regard. Our claim is that separate analyses of the two profiles (unsatisfied and critical) will make it clear not only that they are not the same, but also that critical citizens are always positive for democracy and that dissatisfaction can be both positive or negative, depending on whether or not it is related to a critical stance.

To do so, we show that the quality that distinguishes the critical citizen is not dissatisfaction, but “cognitive mobilization”, which does not necessarily bring about dissatisfaction. We operationalize this concept in the same way that Dalton (2013) does in his research about partisanship in the United States. The author classifies voters according to their party identification and their degree of cognitive mobilization, the latter being composed of the individuals’ education level and political interest. In this model, Dalton establishes the difference between voters who have the cognitive tools needed to pursue a critical attitude and those without such tools. This important breakthrough has not yet been applied to the study of the critical citizen.

MARIO FUKS; GABRIEL AVILA CASALECCHI; MATEUS MORAIS ARAÚJO

The typology of citizens

Investigating the nature of the critical citizen is not an easy task. It requires taking several decisions. For our purposes, three categories were particularly important: support for democracy, satisfaction with the regime, and critical stance. Regarding the first two categories, which give rise to the dissatisfied democrat, we adopted procedures similar to those used by Doorenspleet (2012).

Although there is much debate about the ideal measure of support for democracy, most studies take as a reference point a question comparing the democratic regime to other forms of government. In the Americas Barometer, this question is formulated as follows:

With which of the following statements do you agree most: for people like me, it doesn’t matter whether we have a democratic or non-democratic regime; democracy is preferable to any other form of government; or, under some circumstances an authoritarian government may be preferable to a

democratic one?

Only those who chose the second option, that is, the preference for democracy over any other form of government, were considered democrats.

Satisfaction with the regime is also controversial, especially when related to the critical citizen. Although Norris (1999) classified satisfaction with democracy and trust in institutions as different dimensions of political legitimacy, she used both terms to indicate the dissatisfaction of citizens with the performance of the political regime. In this case, when addressing the issue of the critical citizen, some authors have emphasized distrust in institutions, whereas others have emphasized dissatisfaction with regime performance. Nonetheless, it is important to consider that satisfaction with the system is more abstract than distrust in institutions, and therefore less subject to short-term changes (Norris, 1999). Therefore, as in Doorenspleet’s work (2012), we chose to use a measure of dissatisfaction with the regime instead of distrust in institutions. The question used was the following: “In general, are you very satisfied, satisfied, dissatisfied, or very dissatisfied with the way democracy works?” We considered dissatisfied citizens those who stated they were dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with democracy.

After choosing the variables to measure support for democracy and satisfaction with the democratic regime, it is necessary to define “critical”. By conflating the critical citizen to the dissatisfied, Norris (1999) causes a lot of confusion, as this leads to the assumption that critical citizens will always have negative attitudes. We reject this association and also claim that the dissatisfaction may have different consequences in different countries depending on whether or not it comes from a critical stance.

an informed view of political reality. More specifically, we propose that an informed view of political reality depends on cognitive mobilization. As stated by Dalton (2013):

Cognitive mobilization means that more people now possess the political

resources and skills that better prepare them to deal with the complexities of

politics and reach their own political decisions with less reliance on affective, habitual party loyalties or other external cues (Dalton, 2013, p. 822).

Dalton measures cognitive mobilization combining two variables: political interest and education level. These variables are chosen to ensure that cognitive skills, fostered through education, are combined with attention to politics. Thus, both components of cognitive mobilization are essential and complementary.

We follow Dalton’s (2013) steps for constructing a variable of cognitive mobilization. Education level was divided into four categories for Brazil and the United States: illiterate or complete elementary education; incomplete or complete high school; some college education; and college degree or higher. Interest in politics was also constructed with four categories that were obtained from the following question: “How much are you interested in politics: very, somewhat, little, or not at all?” To obtain the final variable of cognitive mobilization, the education level and political interest variables were summed to obtain a scale ranging from 2 to 8. Adopting Dalton’s (2013) cut-off criterion, individuals with 2 to 5 points were considered to have low cognitive mobilization, and those with 6 to 8 points were considered to have high cognitive mobilization.

Table 1 shows the distribution of the variables. The percentage of democrats was greater than that of non-democrats, and the percentage of those who were satisfied was greater than the percentage of those who were dissatisfied in both countries. It is worth noting that the United States had higher percentages of democrats and dissatisfied individuals than Brazil. Additionally, the percentage of respondents in the United States who were interested in politics and have higher education levels greatly exceeds the corresponding percentage in Brazil.

MARIO FUKS; GABRIEL AVILA CASALECCHI; MATEUS MORAIS ARAÚJO

Table 1

Percentage distribution of support for democracy, satisfaction with democracy, political interest, education level and cognitive mobilization3

Brazil United States

Non-democrats 23.9 16.7

Democrat 65.9 82.7

No response 10.2 0.5

Total (n) 100 (2,482) 100 (1,500)

Satisfied 61.4 53.3

Dissatisfied 33.6 43.5

No response 5.0 0.1

Total (n) 100 (2,482) 100 (1,500)

Not interested 35.8 4.5

Little interested 40.6 14.8

Somewhat interested 13.5 35.3

Very interested 8.8 45.4

No response 1.2 0.0

Total (n) 100 (2,482) 100 (1,500)

Elementary school 47.3 5.5

High school 41.1 36.9

Some college 7.9 48.1

College degree 1.9 9.5

No response 1.9 0.0

Total (n) 100 (2,482) 100 (1,500)

Low cognitive mobilization 88.5 36.6

High cognitive mobilization 8.3 63.4

No response 3.1 0.0

Total (n) 100 (2,482) 100 (1,500)

Source: Americas Barometer, 2010.

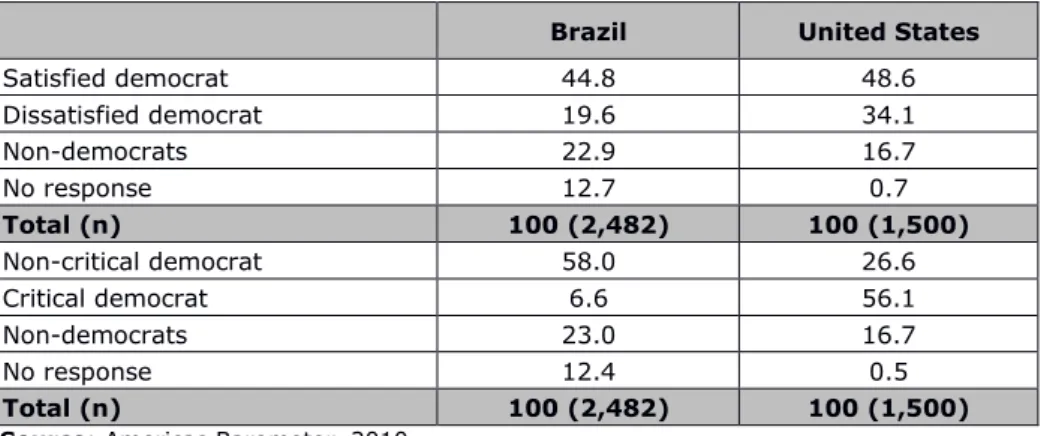

Having defined the variables support for democracy, satisfaction, and cognitive mobilization, we can now construct the types of citizens. Following Doorenspleet’s (2012) suggestion, the “dissatisfied democrat” model is derived from a combination of the variables of support for democracy and satisfaction with the democratic regime (Table 2). The alternative model is the “critical democrat”, which reflects a combination of support for democracy and cognitive mobilization (Table 2).

Table 2

Typology of dissatisfied democrats and critical democrats

Satisfied with democracy Cognitive mobilization

Yes No Yes No

Support for democracy

Yes Satisfied democrat

Dissatisfied democrat

Critical democrat

Non-critical democrat

No Authoritarian Authoritarian

Source: Based on Doorenspleet (2012) and Dalton (2013).

Table 3 shows the percentage of each type of citizen, per country. Consistent with the percentages found previously, the percentage of dissatisfied democrats is higher in the United States than in Brazil, and the same applies to the percentage of critical democrats. The large differences between countries are worth noting, especially with regard to critical democrats. Although this percentage did not exceed 7% in Brazil, it reached more than 56% in the United States.

Table 3

Percentage distribution of satisfied democrats, dissatisfied democrats, non-critical democrats, critical democrats and non-democrats

Brazil United States

Satisfied democrat 44.8 48.6

Dissatisfied democrat 19.6 34.1

Non-democrats 22.9 16.7

No response 12.7 0.7

Total (n) 100 (2,482) 100 (1,500)

Non-critical democrat 58.0 26.6

Critical democrat 6.6 56.1

Non-democrats 23.0 16.7

No response 12.4 0.5

Total (n) 100 (2,482) 100 (1,500)

Source: Americas Barometer, 2010.

Are dissatisfied democrats critical?

MARIO FUKS; GABRIEL AVILA CASALECCHI; MATEUS MORAIS ARAÚJO

Table 4 shows the percentage of dissatisfied democrats among critical democrats in Brazil and the United States as well as the Chi-square test for the association between these two variables in each country.

Table 4

Percentage distribution of critical democrats among satisfied and dissatisfied democrats and chi-squared

Brazil

Satisfied democrat Dissatisfied democrat

Non-critical democrat 89.3 90.2

Critical democrat 10.7 9.9

Total (n) 100 (1,523)

Chi-squared 0,0001

United States

Satisfied democrat Dissatisfied democrat

Non-critical democrat 34.8 28.2

Critical democrat 65.2 71.8

Total (n) 100 (1,240)

Chi-squared 6,1180*

Source: Americas Barometer, 2010.

*p < .01.

The data show that the percentage of critical democrats in the United States exceeded that of the non-critical democrats among both the dissatisfied and satisfied democrats. In Brazil, however, non-critical democrats outnumbered critical democrats among both the dissatisfied and satisfied democrats. Only in the United States was there a statistically significant positive association. However, this association does not indicate that the “dissatisfied democrat” and the “critical democrat” are synonymous because approximately 28% of the dissatisfied democrats in the United States were not critical. Moreover, there is little difference between satisfied and dissatisfied democrats regarding being critical. Whereas 71% of the dissatisfied democrats were critical, 65% of the satisfied democrats were also critical. This result shows that dissatisfaction with democracy is independent of critical competence.

Dissatisfaction or criticism: what matters?

regime faces economic, social, or political crises (Booth and Seligson, 2009; Inglehart, 2003).

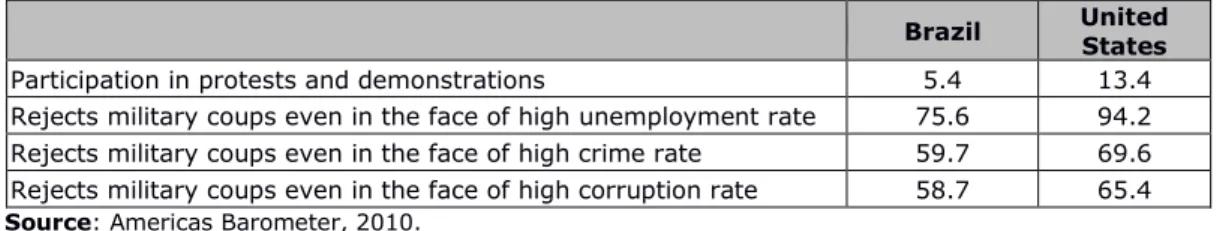

If the more engaged citizens are not equally committed with democracy, their behavior might undermine the foundations of democracy. But if the protesters are committed to democracy, their participation should help improve democracy. To conduct these tests, we use the following question on participation in demonstrations and protests: “In the last twelve months, have you participated in any demonstration or public protest?” Regarding the commitment to democracy, we selected three variables using the following questions: “Facing very high unemployment rates, is it justifiable for the military to take power by means of a coup, or is it not justifiable for the military to take power by a coup?”; “when there is a high crime rate, is it justifiable for the military to take power by a coup, or is it not justifiable for the military to take power by a coup?”; in the face of high levels of corruption, is it justifiable for the military to take power by a coup, or is it not justifiable for the military to take power by a coup?”. Our hypothesis is that critical ability (measured by cognitive mobilization), rather than dissatisfaction, explains participation and commitment to democracy.

Table 5 shows that participation in protests and demonstrations and the rejection of military coups in the cases of high unemployment, crime, and corruption rates are higher in the United States than in Brazil.

Table 5

Percentage distribution of political participation and rejection of military coups in the face of high rates of unemployment, crime and corruption

Brazil United

States

Participation in protests and demonstrations 5.4 13.4

Rejects military coups even in the face of high unemployment rate 75.6 94.2

Rejects military coups even in the face of high crime rate 59.7 69.6

Rejects military coups even in the face of high corruption rate 58.7 65.4

Source: Americas Barometer, 2010.

The focus of our analysis, however, is the effect of each type of citizen on the participation and rejection of military coups, even when controlled by other variables and, more importantly, when one is controlled by the other. We also want to know whether dissatisfied critical democrats are more participative in and committed to democracy than satisfied critical democrats. We will test that through the interaction of the critical democrats and dissatisfied democrats.

MARIO FUKS; GABRIEL AVILA CASALECCHI; MATEUS MORAIS ARAÚJO

critical democrat and another without the interaction. Adjusted in this way, it is possible to interpret the effect of each type of citizen separately, as well as their interaction.

Table 6

Effects on participation and rejection of coups in the face of unemployment, crime and corruption – Brazil

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4

Participation in protests and demonstrations

Rejects military coups even in the face of high

unemployment

Rejects military coups even in the face of high

crime

Rejects military coups even in the face of

corruption Without Interaction With Interaction Without Interaction With Interaction Without Interaction With Interaction Without Interaction With Interaction Dissatisfied democrat 1,82** (0,458) 1,50 (0,442) 0,57*** (0,107) 0,62** (0,122) 0,71** (0,102) 0,71** (0,106) 0,62*** (0,087) 0,61*** (0,090) Critical democrat 4,12** (1,162) 3,07*** (1,083) 1,29 (0,405) 1,87 (0,824) 1,95** (0,489) 1,98** (0,601) 1,63** (0,392) 1,54 (0,451) Dissatisfied*

critical -

2,10

(1,194) -

0,42

(0,263) -

0,96

(0,503) -

1,17 (0,582)

Man 1,24

(0,299) 1,24 (0,301) 0,65** (0,122) 0,65** (0,122) 0,69** (0,093) 0,69** (0,093) 0,74** (0,100) 0,75** (0,100)

Age in years 0,98** (0,008) 0,98** (0,008) 1,00 (0,006) 1,00 (0,006) 1,00 (0,005) 1,00 (0,005) 1,00 (0,005) 1,00 (0,005)

Black 0,68 (0,169) 0,68 (0,169) 0,82 (0,148) 0,82 (0,149) 1,26* (0,168) 1,26* (0,168) 0,97 (0,129) 0,97 (0,129)

Catholic 1,13 (0,288) 1,11 (0,285) 0,65** (0,127) 0,66** (0,128) 0,92 (0,128) 0,92 (0,128) 1,01 (0,138) 1,01 (0,138)

Urban 1,53 (0,663) 1,58 (0,682) 0,83 (0,230) 0,83 (0,227) 0,71* (0,148) 0,71* (0,147) 0,70* (0,143) 0,70* (0,143)

Constant 0,05*** (0,028) 0,05*** (0,030) 19,11*** (8,757) 18,61*** (8,524) 3,66*** (1,145) 3,65*** (1,147) 4,25*** (1,331) 4,26*** (1,340)

Observations 1449 1449 1373 1373 1380 1380 1374 1374

Source: Americas Barometer, 2010.

Table 7

Effects on participation and rejection of coups in the face of unemployment, crime and corruption – U.S.

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4

Participation in protests and demonstrations

Rejects military coups even in the face of high

unemployment

Rejects military coups even in the face of high

crime

Rejects military coups even in the face of

corruption Without Interaction With Interaction Without Interaction With Interaction Without Interaction With Interaction Without Interaction With Interaction Dissatisfied democrat 1,19 (0,192) 0,64 (0,282) 0,57 (0,196) 0,53 (0,236) 0,85 (0,156) 0,73 (0,200) 0,62** (0,106) 0,53** (0,143) Critical democrat 4,03*** (0,909) 3,00*** (0,846) 2,83*** (0,998) 2,56* (1,286) 3,27*** (0,588) 2,92*** (0,681) 2,12*** (0,365) 1,89** (0,425) Dissatisfied*

Critical -

2,07

(0,978) -

1,21

(0,837) -

1,31

(0,479) -

1,32 (0,455)

Man 1,79***

(0,297) 1,78*** (0,296) 1,36 (0,493) 1,36 (0,492) 1,79*** (0,326) 1,78*** (0,326) 1,31 (0,225) 1,31 (0,224)

Age in years 0,99** (0,005) 0,99** (0,005) 1,01 (0,011) 1,01 (0,011) 1,01** (0,006) 1,01** (0,006) 1,01** (0,005) 1,01** (0,006)

Black 0,42** (0,146) 0,42** (0,145) 1,05 (0,557) 1,05 (0,557) 0,49** (0,132) 0,49** (0,132) 0,65* (0,170) 0,65* (0,170)

Protestant 1,13 (0,188) 1,12 (0,187) 0,60 (0,216) 0,60 (0,215) 1,02 (0,192) 1,01 (0,191) 0,87 (0,153) 0,86 (0,152)

Constant 0,07*** (0,022) 0,09*** (0,029) 10,32*** (5,779) 10,75*** (6,247) 0,57* (0,172) 0,61 (0,189) 0,74 (0,210) 0,79 (0,235)

Observations 1181 1181 564 564 566 566 568 568

Source: Americas Barometer, 2010.

Logistic Regression. Odds Ratio. Standard errors in parentheses *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

In Brazil, as shown in Table 6, critical democrats have a greater chance of participating than their uncritical peers. The chances of rejection of military coups are also higher among critical democrats, except in the case of high unemployment. For the US (Table 7), the results reveal the same pattern, but even more robust: critical democrats have greater chances of participating and rejecting military coups in any scenario (crime, corruption, and unemployment) than their uncritical peers.

The attitudes and behaviors of dissatisfied democrats go in opposite directions, showing some ambivalence, especially in Brazil. Dissatisfied democrats in Brazil have greater chances of participating than their satisfied peers but are more likely to support military coups. In the United States, we find that there are virtually no differences between dissatisfied and satisfied democrats. The only exception is a scenario in which there is a lot of corruption; dissatisfied democrats have greater chances of supporting military coups than satisfied democrats in such a context.

MARIO FUKS; GABRIEL AVILA CASALECCHI; MATEUS MORAIS ARAÚJO

That may be just a coincidence, but it suggests that further studies with other databases or other countries have the potential to shed more light on the difference between old and new democracies.

The results of the logistic regression showed that critical democrats’ behaviors and attitudes differ from those of their non-critical peers. Dissatisfied democrats, usually, do not differ from satisfied ones; when they do, however, they are even less democratic than satisfied democrats. In any case, our analysis did not prove the hypothesis that the interaction between dissatisfaction and high cognitive mobilization would be the best case for democracy.

In short, our findings show that critical democrats normally differ from uncritical ones in their behavior and democratic commitment, while dissatisfied democrats, usually, do not differ from satisfied democrats and, when they do, are even less democratic.

The lack of significance in the interactions shows that the effect of cognitive skills over democratic attitudes and behavior does not depend on dissatisfaction. That is, dissatisfaction with the way democracy works does not make knowledgeable citizens more committed to democracy and more engaged in politics. Our study, therefore, does not support the argument that the ideal democratic citizen would be, necessarily, a dissatisfied one with cognitive skills.

In Norris’s model the democratic citizen has the cognitive skills to assess the political world and aspires more to democracy than he/she gets. According to Norris, this dissatisfaction with the way democratic institutions work is not a danger to democracy because it comes together with support for the regime. Our study shows that, at least in Brazil, being dissatisfied with democracy increases the likelihood of political participation, but decreases the commitment to democracy. This is a potentially dangerous combination, because participation without democratic commitment can result in anti-democratic behavior.

Conclusion

Since the publication of Critical citizens, the term “critical citizen” has gained popularity in studies on political culture. However, despite the recurrent use of the term, few studies have conducted in-depth analyses of this phenomenon. By reevaluating the concept of the critical citizen and testing it empirically, our study advances research in that direction. It should be emphasized that this advance was based on analysis at the individual data level. Many of the inferences regarding the emergence of critical citizens were made from aggregate data, with countries as the unit of analysis. Our approach began with the attributes of individuals and used those attributes to determine whether and to what extent dissatisfied democrats are critical.

indistinguishable from satisfied democrats. In fact, in some cases, the pattern is the opposite of what is expected based on theory.

It is clear from the results that the critical democrat and the dissatisfied democrat should not be confused or treated interchangeably. A dissatisfied democrat is not necessarily critical and is therefore not always aware of and informed about politics. Our study also shows that the critical democrat, not the dissatisfied democrat, possesses the attributes of Norris’s critical citizen. That is, the “critical democrat” engages in unconventional forms of political participation and unequivocally expresses a commitment to democracy.

These results raise important questions concerning the legitimacy and quality of democracy, especially in Brazil. As the data show, the number of critical democrats in Brazil is much lower than that in the United States, primarily because Brazilians have lower education levels and political interest than United States citizens. This point is particularly important because the democratic commitment of non-critical democrats, who make up the majority of the population, is inconsistent.

Mario Fuks– Associate Professor, Departament of Political Science, College of Philosophy and

Human Sciences (Fafich), Federal University of Minas Gerais. E-mail: <mariofuks@gmail.com>.

Gabriel Avila Casalecchi –Doctor and post-doctoral fellow at Capes, Department of Sociology

and Political Science, Center of Philosophy and Human Sciences, Federal University of Santa Catarina. E-mail: <gacasalecchi@gmail.com>.

Mateus Morais Araújo – Researcher at the Observatory of Justice in Brazil and Latin

America, Federal University of Minas Gerais. Doctorate in Political Science, Department of Political Science, College of Philosophy and Human Sciences (Fafich), Federal University of Minas Gerais. E-mail: <mateus.m.araujo@gmail.com>.

Bibliographic references

BOOTH, J.; SELIGSON, M. The legitimacy puzzle: democracy and political support in eight Latin American nations. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

BRATTON, M.; MATTES, R. “Support for democracy in Africa: intrinsic or instrumental?”. British Journal of Political Science, 31(3), p. 447-474, 2001.

CARLIN, R. E.; SINGER, M.; ZECHMEISTER, E. (eds.). The Latin American voter: pursuing representation and accountability in challenging contexts. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2016.

CROZIER, M.; HUNTINGTON, S.; WATANUKI, J. The crisis of democracy: report on the governability of democracies to the trilateral commission. New York, NY: New York University Press, 1975.

MARIO FUKS; GABRIEL AVILA CASALECCHI; MATEUS MORAIS ARAÚJO

DALTON, R. J. Democratic challenges, democratic choices: the erosion of political support in advanced industrial democracies. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press, 2004.

________. The apartisan American: dealignment and changing electoral politics. [Kindle edition]. Thousand Oaks, California/London/Nova Delhi: CQ/Sage, 2013.

DALTON, R.; SHIN, D. C. Citizens, democracy, and markets around the Pacific rim: congruence theory and political culture. London: Oxford University Press, 2006.

DIAMOND, L. Political culture and democracy in developing countries. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1994.

________. “Thinking about hybrid regimes”. Journal of Democracy, 13(2), p. 21-35, 2002.

DOORENSPLEET, R. “Critical citizens, democratic support and satisfaction in African democracies”.

International Political Science Review, 33(3), p. 279-300, 2012.

FOA, S.; MOUNK, Y. “The democratic disconnect”. Journal of democracy, 27(3), p. 5-17, 2016.

INGLEHART, R. The silent revolution: changing values and political styles among Western publics. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1977.

________. Postmodernization erodes respect for authority, but increases support for democracy. In: NORRIS, P. (ed.). Critical citizens: global support for democratic governance. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press, p. 236-257, 1999.

________. “How solid is mass support for democracy and how can we measure it?”. Political Science and Politics, 36(1), p. 51-57, 2003.

INGLEHART, R.; WELZEL, C. Modernization, cultural change and democracy: the human development sequence. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

KLINGEMANN, H.-D. Mapping political support in the 1990s: a global analysis. In: NORRIS, P. (ed.).

Critical citizens: global support for democratic governance. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press, p. 31-56, 1999.

KLINGEMANN, H.-D.; FUCHS, D. Citizens and the State. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1995.

MILLER, A. “Political issues and trust in government: 1964-1970”. TheAmerican Political Science Review, 68(3), p. 951-972, 1974.

MISHLER, W.; ROSE, R. Five years after the fall: trajectories of support for democracy in post-communist Europe. In: NORRIS, P. (ed.). Critical citizens: global support for democratic governance. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press, p. 78-103, 1999.

________. “Political support for incomplete democracies: realist vs. idealist theories and measures”. International Political Science Review, 22(4), p. 303-320, 2001.

MOISÉS, J. A. Os brasileiros e a democracia: bases sociopolíticas da legitimidade democrática. São Paulo: Ática, 1995.

________. “Cultura política, instituições e democracia: lições da experiência brasileira”. Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais, 23(66), p. 11-43, 2008.

NORRIS, P. Critical citizens: global support for democratic government. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1999.

PUDDINGTON, A. “The freedom house survey for 2012: breakthroughs in the balance”. Journal of

Democracy, 24(2), p. 46-61, 2013.

SALINAS, E.; BOOTH, J. “Micro-social and contextual sources of democratic attitudes in Latin America”.

Journal of Politics in Latin America, 3(1), p. 29-64, 2011.

TORCAL, M.; MONTEIRO, J. R. Political disaffection in contemporary democracies: social capital, institutions, and politics. London: Routledge, 2006.

Abstract

Are dissatisfied democrats critical? Reevaluating the concept of the critical citizen

Several studies have used the terms “critical citizen”and “dissatisfied democrat”interchangeably, assuming that both address the same citizen profile. However, recent studies conducted in new democracies have questioned this assumption, arguing that those who are dissatisfied are not always critical. This article investigates this question based on a comparison of the United States and Brazil. Beginning with the classification of two types of citizens, “dissatisfied democrats” and “critical

democrats”, we appraise whether dissatisfied democrats are critical. Then, we test which of these two types of citizens is more engaged and has attitudes that are more democratic. The results show that dissatisfied democrats are not necessarily critical and that critical democrats are more engaged in politics and more committed to democracy than non-critical democrats.

Keywords: critical citizen; dissatisfied democrat; democratic commitment; cognitive mobilization

Resumo

Os democratas insatisfeitos são críticos? Reavaliando o conceito de cidadão crítico

Vários estudos utilizam os termos “cidadão crítico” e “democrata insatisfeito” de forma intercambiável, assumindo que ambos abordam o mesmo perfil de cidadão. No entanto, estudos recentes conduzidos em novas democracias questionaram essa suposição, argumentando que aqueles que estão insatisfeitos nem sempre são críticos. Este artigo investiga essa questão com base numa comparação entre os Estados Unidos e o Brasil. A partir da criação de dois tipos de cidadãos, o democrata insatisfeito e o democrata crítico, nós avaliamos se os democratas insatisfeitos são também críticos. Em seguida, testamos qual dos dois tipos de cidadão é mais engajado e tem atitudes mais democráticas. Os resultados mostram que os democratas insatisfeitos não são necessariamente críticos e que os democratas críticos estão mais engajados na política e mais comprometidos com a democracia do que os democratas não críticos.

Palavras-chave: cidadão crítico; democrata insatisfeito; compromisso democrático; mobilização cognitiva

Resumen

¿Son críticos los demócratas insatisfechos? Reevaluar el concepto del ciudadano crítico

MARIO FUKS; GABRIEL AVILA CASALECCHI; MATEUS MORAIS ARAÚJO

necesariamente críticos y que los demócratas críticos están más comprometidos con la política y con la democracia que los demócratas no críticos.

Palabras clave: ciudadano crítico; demócrata insatisfecho; compromiso democrático; movilización cognitiva

Résumé

Les démocrates insatisfaits sont-ils critiques? Réévaluer le concept de citoyen critique

Plusieurs études ont utilisé les termes «citoyen critique» et «démocrate insatisfait» de façon interchangeable, en supposant que les deux termes traitent le même profil de citoyen. Cependant, des études récentes menées dans de nouvelles démocraties ont mis en doute cette hypothèse en arguant que ceux qui ne sont pas satisfaits ne sont pas toujours critiques. Cet article étudie cette question en fonction d'une comparaison entre les États-Unis et le Brésil. À partir de la création de deux types de citoyens, «démocrates insatisfaits» et «démocrates critiques», nous évaluons si les démocrates insatisfaits sont critiques. Ensuite, nous testons les deux types de citoyens pour savoir lequel est le plus engagé et a des attitudes les plus démocratiques. Les résultats montrent que les démocrates insatisfaits ne sont pas nécessairement critiques et que le démocrate critique est plus engagé dans la politique et est plus engagé envers la démocratie que les démocrates non critiques.

Mots-clés: citoyen critique; démocrate insatisfait; engagement démocratique; mobilisation cognitive