Flávio Machado Mandlate

maio de 2014

Stress and frequency of relapses among

patients admitted in a short term detoxification

unit - comparative study between alcohol and

other drugs use

Stresse e a frequência de recaídas em

pacientes admitidos para desintoxicação aguda

- um estudo comparativo entre o uso de álcool

e consumidores de outras drogas

UMinho|20 14 Flá vio Mac hado Mandlat e

Stress and frequency of relapses among patients admitted in a shor

t term de

to

xification unit - comparative s

tudy be

tw

een alcohol and o

ther drugs use

Universidade do Minho

Escola de Ciências da Saúde

Trabalho efetuado sob a orientação do

Professor Doutor Nuno Jorge Carvalho Sousa

e co-orientação do

Professor Doutor Pedro Ricardo Luís Morgado

e do

Professor Doutor António Pacheco Palha

Flávio Machado Mandlate

maio de 2014

Dissertação de Mestrado

Mestrado em Ciências da Saúde

Stress and frequency of relapses among

patients admitted in a short term detoxification

unit - comparative study between alcohol and

other drugs use

Stresse e a frequência de recaídas em

pacientes admitidos para desintoxicação aguda

- um estudo comparativo entre o uso de álcool

e consumidores de outras drogas

Universidade do Minho

Escola de Ciências da Saúde

iii

"The greatest weapon against stress is our ability to choose one thought over another

.

" William James (1842 - 1910)v AGRADECIMENTOS

Em primeiro lugar agradecer ao Ministério de Saúde de Moçambique por ter disponibilizado bolsa de estudos e me ter dispensado durante estes dois anos para minha formação numa escola tão prestigiada como é a Escola de Ciências de Saúde - Instituto de Investigação em Ciências da Vida e Saúde (ECS/ICVS) da Universidade do Minho. Ao ICVS desde a sua direção, os técnicos e toda a equipa de brilhantes professores, investigadores que sempre estiveram disponíveis para transmitir conhecimentos valiosos e de alta utilidade para o futuro da minha carreira e quiçá para o futuro da humanidade.

À Professora Joana Almeida Palha por ter criado todas as condições "protocolares" para que fosse possível a formação do primeiro grupo de investigação em neurociências moçambicano.

À Professora Margarida Correia-Neves pelo acolhimento desde o primeiro dia da nossa chegada a Braga, pelo estímulo e pela ajuda para focalizar o objetivo na formação.

À Dra Lídia Gouveia por ter apostado e torcido por mim e ter criado todas as condições

básicas para a minha formação e pela incansável luta para criar uma equipa forte de investigação em Saúde Mental.

Ao Professor Doutor António Pacheco Palha o mestre dos mestres, pelo seu fervoroso ativismo pela formação mais qualificada e de qualidade para os médicos moçambicanos no geral e Psiquiatras em particular. Extensivo á Casa de Saúde do Bom Jesus onde é diretor clínico, pela hospitalidade à nossa formação académica e clínica.

Ao Dr António Sulemane pela continua motivação e preparação psicológica sobre a vida e o quotidiano de estudante em Portugal.

Ao Professor Doutor Pedro Morgado pela forma pedagógica e objetiva como me acompanhou e preparou na crítica e analise dos artigos e a comunicar com rigor cientifico.

Ao Professor Doutor Nuno Sousa por me ter ensinado com concisão o funcionamento do cérebro.

vi

À Doutora Nadine dos Santos pela disponibilidade e valiosa acessoria técnica que me concedeu durante a realização do estudo.

Ao José Carlos Nunes Portugal, meu peer reviewer por me ter ajudado a perceber o complexo mundo de investigação desde os mais pequenos detalhes.

Ao Rui Sanches e à Sofia Neves pelo apoio técnico e competente para realização de todos procedimentos laboratoriais sem os quais este estudo não faria sentido.

Ao Dr Torres Freixo o meu agradecimento muito especial pela amizade sincera e por ter conseguido abrir canais para continuar com o estudo fora de Braga, sem o qual não teria um terço da minha amostra.

Ao Dr. Santos Silva e à Dra Margarida Pinho da Unidade de Desabituação do Norte,

Matosinhos, por terem aberto as portas e pela rápida resposta e disponibilidade institucional para recolha de dados.

Aos meus colegas Dirceu, Wilza e Sâmia por termos formado uma verdadeira família e criado um espírito de interajuda em todos momentos difíceis a que juntos passamos.

Aos meus pais por me terem ensinado a ter um espírito de luta e me apoiarem incondicionalmente nas minhas decisões e escolhas.

Aos meus filhos Aline, Patrícia e Haniel minha fonte de inspiração, pelo carinho e amor profundo que me transmitem mesmo com a distancia que nos separa.

À minha esposa Carminda Piedade pela paciência, carinho e apoio incondicional nos momentos mais difíceis, meu porto seguro.

Aos meus irmãos que sempre acreditaram em mim sempre torceram por mim.

Aos pacientes participantes do estudo pelo seu sempre humilde e sincero "...se for para ajudar, aceito....", pois, sem eles o estudo não teria se concretizado.

Aos enfermeiros da Unidade São Luís da Casa de Saúde do Bom Jesus e da Unidade de Desabituação do Norte em Matosinhos pela cooperação e facilidade de acesso aos pacientes e a informações adicionais.

vii

Stress and frequency of relapses among patients admitted for in a short term detoxification unit - comparative study between alcohol and other drugs use

ABSTRACT

Drug addiction is defined as a disorder characterized by chronic relapsing demand and compulsive drug use. The role of stress in addiction and vulnerability to relapse has been a focus of research during the last decades. However, further comprehensive studies are needed to understand the mechanism by which stress increases relapse. Psychosocial factors and their relationship with the mechanisms of stress during the initiation, maintenance and relapse to drug use are important issues to be addressed. This study aims to evaluate the perceived stress levels as a predictor, or alternatively as a consequence, of unsuccessful treatment and information on issues related to relapse. In this observational cross-sectional study, we assessed the levels of stress (perceived stress and salivary cortisol levels), anxiety and depression scores and their relation with the frequency of relapse comparing patients admitted to a detoxification unit with addiction to alcohol versus other drugs. Data shows that 61,5% of the sample were males and 38.5% females, with mean age of 41,2 years, 44,6% with alcohol dependence and 55,4% abusers of other drugs. The average rate of relapses was 4,51 times, with significant difference found between subjects addicted to alcohol versus other drugs. Significant correlations were found between frequency of relapses and perceived stress, anxiety and depressions scores. We found as predictive variables for stress the anxiety and socioeconomic scores. These results contribute for a better understanding of the mechanisms involved in relapses and pave the way for novel approaches for prevention and treatment of drug addiction particularly by reducing relapse rates.

ix

Stresse e a frequência de recaídas em pacientes admitidos para desintoxicação aguda – um estudo comparativo de pacientes alcoólicos e consumidores de outras drogas

RESUMO

A toxicodependência é definida como uma doença crônica caracterizada pela procura e o uso compulsivo de drogas. O papel do estresse na dependência e vulnerabilidade à recaída têm sido estudado ao longo das últimas décadas. No entanto, estudos mais abrangentes são necessários para compreender o mecanismo pelo qual o estresse aumenta as recaídas. Os fatores psicossociais e a sua relação com os mecanismos de estresse durante a iniciação, manutenção e recaída ao uso de drogas são também questões relevantes a serem abordadas. O presente estudo tem como objetivo avaliar o impacto dos níveis de estresse percebido como um preditor de recaídas ou, alternativamente, como uma consequência do insucesso no tratamento. Neste estudo observacional transversal, foram avaliados os níveis de estresse (stresse percebido e os níveis de cortisol salivar, ansiedade e depressão) e a sua relação com a frequência de recaída comparando pacientes alcoólicos e usuários de outras drogas consecutivamente internados na unidade de desintoxicação aguda. Os resultados mostram que 61,5% da amostra era masculina e 38.5% feminino, com uma média de idade de 41,2 anos. 44.6% tinham dependencia de álcool e 55.4 % de outras drogas. Foram encontradas correlações significativas entre a freqüência de recaídas e as pontuações do estresse percebido, ansiedade e depressão. Foram ainda identificadas como variáveis preditivas para o stresse a ansiedade, o cortisol e o status socioeconômico.

A partir dos resultados deste estudo, esperamos contribuir para uma maior e melhor abordagem para a prevenção e tratamento da toxicodependência, permitindo assim reduzir as taxas de recaída.

xi INDEX DECLARAÇÃO... ii AGRADECIMENTOS ... v ABSTRACT ... vii RESUMO ... ix

INDEX OF TABLE ... xiii

ABBREVIATIONS LIST ... xvii

1. INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1. NEUROBIOLOGY OF ADDICTION ... 3

1.2. STRESS AND RELAPSES ... 3

2. RESEARCH OBJECTIVES ... 7

2.1. Major goal of the Thesis... 9

2.2. Specifics ... 9

3. MATERIAL AND METHODS ... 11

3.1. STUDY DESIGN AND SAMPLING ... 13

3.2. PARTICIPANTS ... 13

3.2.1. Inclusion criteria ... 13

3.2.2. Exclusion criteria ... 13

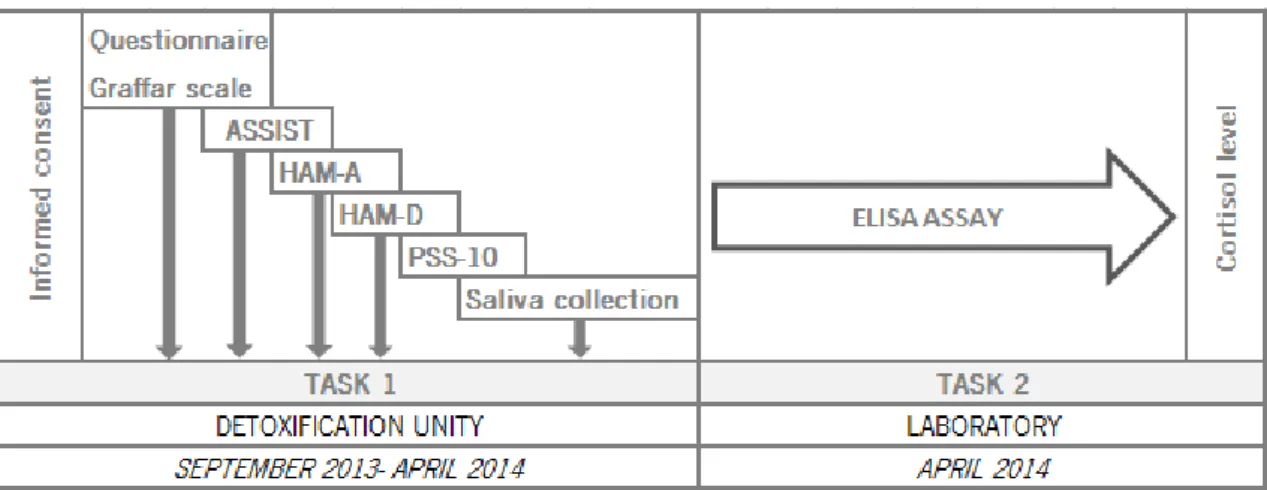

3.3. EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN ... 14

3.3.1. TASK 1: DATA ASSESSMENT ... 15

3.3.1.1. Sociodemographic data assessment ... 15

3.3.1.2. Clinical information ... 15

3.3.1.3. Assessment of substance use ... 15

3.3.1.4. Assessment of Perceived stress ... 16

3.3.1.5. Assessment of stress related comorbilities (e.g. anxiety and depression) .... 16

3.3.2. TASK 2: MATERIAL AND PROCEDURES FOR SALIVARY CORTISOL MEASUREMENT 16 3.3.2.1. Salivary Cortisol levels ... 16

xii

3.3.2.3. Procedure ... 17

3.3.2.4. Analysis ... 17

3.4. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS ... 18

4. RESULTS ... 19

4.1. SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC AND CLINICAL CHARACTERISTS ... 21

4.1.1. Descriptive statistics of socio-demographic and clinical variables ... 21

4.1.2. Relationship between Graffar socioeconomic and assist score with anxiety, depression, perceived stress scale, cortisol and frequency of relapses ... 22

4.1.3. Assessment of addiction related variables ... 23

4.1.4. Assessment of cortisol and psychometric measurement data ... 24

4.2. RELATIONSHIP OF PERCEIVED STRESS, ANXIETY, DEPRESSION, CORTISOL AND RELAPSES ... 27

4.3. PREDICTIVE VARIABLES OF STRESS AND RELAPSES ... 28

5. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS ... 31

5.1. DISCUSSION ... 33

5.2. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY ... 35

5.3. CONCLUSIONS ... 35

6. REFERENCES ... 37

7. ATTACHMENTS ... 43

7.1. TABLES OF STATISTICAL ANALYSIS OF PSYCHOMETRIC MEASUREMENTS AND CORTISOL ... 45

7.2. QUESTIONNAIRE ... 49

7.3. GRAFFAR SCALE ... 53

7.4. HAMILTON DEPRESSION RATING SCALE ... 57

7.5. HAMILTON ANXIETY RATING SCALE ... 63

7.6. PERCEIVED STRESS SCALE - 10 ... 67

7.7. INFORMED CONSENT ... 71

7.8. ALCOHOL, SMOKING AND SUBSTANCE INVOLVEMENT SCREENING TEST (ASSIST) 77 7.9. IBL CORTISOL ELISA KIT ... 79

xiii

INDEX OF TABLE

Table 1: Participants characterization ... 21

Table 2: Clinical characterization of participants ... 22

Table 3: Relationship of socioeconomic score and the ASSIST score with anxiety, depression and perceived stress score using Pearson correlation test. ... 22

Table 4: Assessment of lifetime addictive behavior, relapses, treatment history and relationship with relapses rates. ... 23

Table 5: ASSIST score, quantity and route of consumption. ... 24

Table 6: Correlation between frequency of relapses and HAM-D, HAM-A, PSS-10, Cortisol levels in alcoholic and other drugs users. ... 27

Table 7: Comparison of Pearson correlation between frequency of relapses and PSS-10, Cortisol, HAM-A, HAM-D and relapses by gender. ... 27

Table 8: Comparison of Pearson correlation between time(days) of abstinence and PSS-10, A, HAM-D, Relapses and Cortisol in total sample, alcoholic and other drugs group... 28

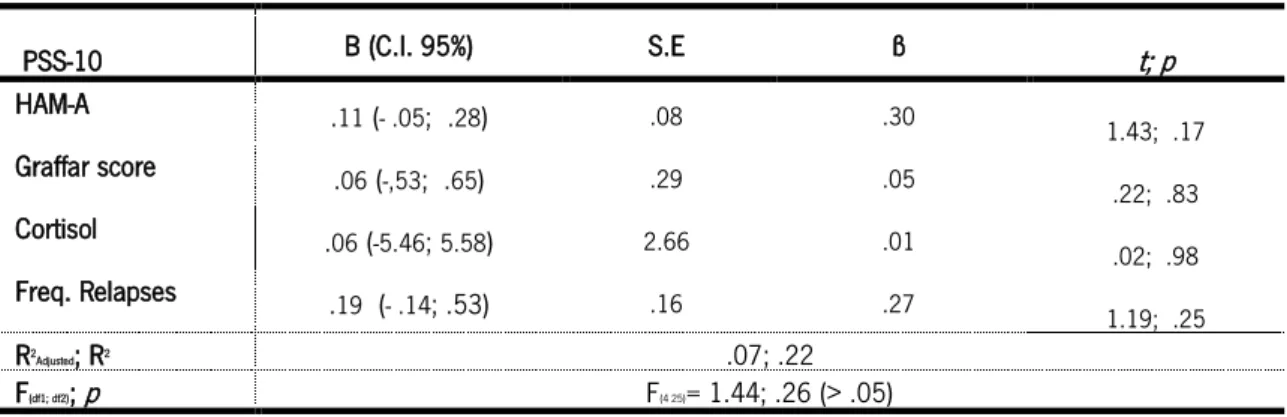

Table 9: Predictive model of stress and relapses in total sample (n=48) ... 28

Table 10: Predictive model of stress and relapses in alcoholic group (n=22) ... 29

Table 11: Predictive model of stress and relapses in other drugs group (n=26) ... 29

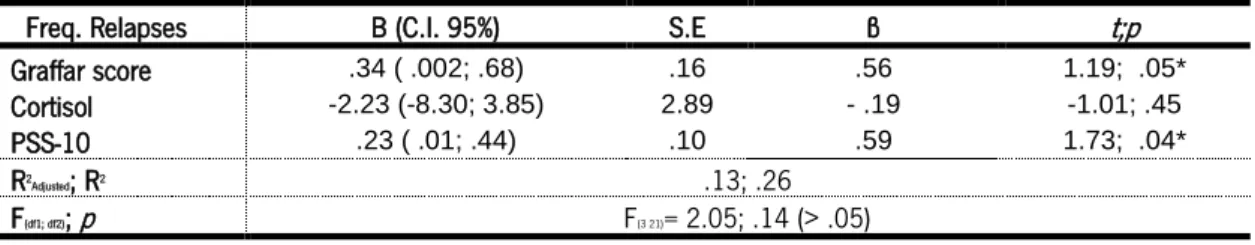

Table 12: Predictive model of relapses in total sample (n=48) ... 30

Table 13: Predictive model of relapses in alcoholic group (n=22) ... 30

Table 14: Predictive model of relapses in other drugs users (n=26) ... 30

Table 15: Comparison of psychometric measurements and cortisol between alcoholic and other drugs group. ... 47

Table 16: Comparison of frequency of relapses, perceived stress, cortisol levels, anxiety and depression scores between males and females. ... 47

xv

INDEX OF FIGURES

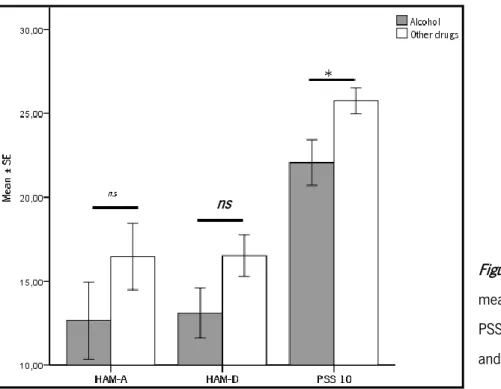

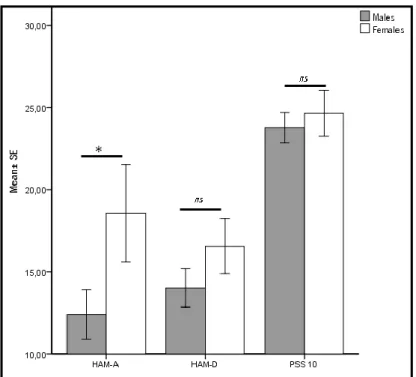

Figure 1: Stress, anxiety and depression increases individual vulnerability to drug use, addiction and relapse ... 4 Figure 2: Experimental design and timeline ... 14 Figure 3: Sample distribution according to main substance of abuse. ... 14 Figure 4: Comparison of mean of HAM-A, HAM-D and PSS-10 between alcoholic and other drug users group. ... 25 Figure 5: Comparison of mean morning and afternoon cortisol level between alcoholic and other drugs group ... 25 Figure 6: Comparison of HAM-A, HAM-D and PSS-10 between males and females. ... 26 Figure 7: Comparison of morning and afternoon cortisol between males and female ... 26

xvii ABBREVIATIONS LIST

ANOVA Analysis of variance

ASSIST Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test

CRF Corticotropin Release Factor

d Cohen´s d effect size

ELISA Enzyme-linked Immunoassay

HPA Hypothalamus Pituitary Adrenal

HAM-A Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale HAM-D Hamilton Depresssion Rating Scale ICD-10 International Classification of Disease

NAC Nucleus accumbens

PSS-10 Perceived Stress Scale

SPSS Statistical Package for Social Sciences

VTA Ventral tegmental area

1

3 1.1. NEUROBIOLOGY OF ADDICTION

Drug addiction is defined as a brain chronic relapsing disorder characterized by compulsive seeking and uncontrollable use of substance of abuse of substance [1, 2]; furthermore when there is limited access of drug these individuals develop negative affect (e.g. anxiety, dysphoria) [3]. The definition criteria of addiction, distinguish three pattern of consumption; use, abuse and dependence. In each stage, there are neuroadaptative changes (epi)genetic, celullar and molecularly mediated, that could overlap to the next stage [3]. Both genetic and environmental factors contribute to the establishment of addictive disorders [4, 5] and several studies have demonstrated the key role of stress [6] and individual factors [7] on addictive behavior and vulnerability to relapse[8] . It has also been demonstrated the role of dopaminergic system which involves projections from ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and dorsal striatum, regions known as the main areas of reward and reinforcement pathways [5, 9, 10]. Prefrontal cortex has also been associated with acute and chronic drug use [7]. Specific cerebral pathways involved in addiction are dependent on the type of drug consumed, but, interestingly, craving and relapse are distinct phenomena that seem to be mediated by the same pathways, through the same brain areas and using the same neurotransmitter systems.

Although there are treatments for additive disorders [11], most subjects addicted alcohol [11, 12] and cocaine [13], display high rates of relapses. Relapse is the most challenging problem during treatment of substance abuse [14, 15] disorders. Most relapses occur during early abstinence period, which compromise [16] treatment even after detoxification [7] process and frustrates the expectations of stakeholders.

1.2. STRESS AND RELAPSES

Stress is considered an important factor in the process of addiction but also as a trigger for relapse [17]. Long-term drug consumption, withdrawal and abstinence [18] may result in dysregulation of hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and in the reward system which play an important role in addiction relapse [19]. As it influences motivation and mediates anxiety and stress responses during withdrawal period [9, 20], abnormal HPA axis response is associated with high vulnerability to substance addiction and relapse [13]. In fact, exposure to drug, stress and environmental stimuli, which includes elicited negative emotions, [4] were identified as

4

strong relapse triggers (fig 2). Environmental stimuli [2] may stimulate the HPA-axis during acute abstinence period resulting in lower awakening cortisol response which lead to high levels of stress during the rest of the day, impaired self control to drug use, with an associate increased risk for relapse [5, 18]. Cumulative stressful events in early life such as fetal exposure to glucocorticoids [21], or early childhood trauma (maltreatment, maternal separation) may influence the brain development and the stress response [22] in later life [23], and has also been shown to modulate some of the steps of the addictive process, namely drug-seeking behavior [21]. Stress-related relapse susceptibility in addictive disorders and other psychiatric conditions also influences coping ability and impulse control [19] and increase vulnerability to addiction. Additionally, compulsive actions are usually perceived as stressful [24] and anxiety relievers [15].

Figure 1: Stress, anxiety and depression increases individual vulnerability to drug use, addiction and relapse

.

Despite the growing body of evidence accumulated in recent years on this topic, there are still gaps to be tackled: firstly most studies were performed in laboratory setting [13], and there is the need for more experimental studies in clinical setting; secondly, although with important explanatory mechanisms for addictive behavior using animal models [1] translational studies in human still lack; third, on clinical studies were assessed only biological [17] or psychosocial factors [16]; fourth, were focusing on one type substance of abuse; fifth, studies were either performed only in outpatient setting or in long-term inpatient contexts; finally, only vulnerability (risk) to relapse were predicted [25] but not retrospectively assessed.

5

Understanding psychosocial and stress mechanisms and its relationship with initiation, maintenance and relapse [26] susceptibility is important for development of prevention and therapeutic approach strategies for addiction [11, 18, 27].

Herein, we were interested in further explore the association between stress and risk of relapse. The final product of HPA axis is the release of cortisol which is involved in functioning to maintain homeostasis of several body systems mainly in central nervous system where, direct or indirectly, regulates areas responsible for cognition and behavior through receptors scattered around the brain [28].

Individuals under stress have deficient strategies in decision-making [29], and such degradation can help to understand the stress related disorders and addictive behavior [30]. Besides the release of corticosteroids, the stress response involves the release of corticotrophin release factor (CRF) and norepinephrine, both of which are also involved in stress-induced relapse in an animal model [13]. Future therapeutic approach acting on this system might reduce drug seeking and relapse [17]. Moreover, the identification of specific biomarkers for stress related-relapse [11], could bring better outcomes in the treatment of addictive disorders[31]. As described among several biomarkers tested to predict relapses, cortisol appeared as one of the most reliable measure[31].

In this Thesis, we aim to assess the actual level of perceived stress as a predictor of unsuccessful treatment and obtain information about relapses both in psychosocial and biological aspects. Although it is described brain and neuronal pathways involved in cortisol regulation, it is still lacking information from clinical studies.

7

9 2.1. MAJOR GOAL OF THE THESIS

Determine the relationship between stress (perceived stress and salivary cortisol levels) and frequency of relapses comparing alcoholic patients group and a group of drugs users. 2.2. SPECIFICS

Identify psychosocial determinants for stress and relapses; (b) Identify comorbilities (e.g: anxiety and depression); (c) Compare the frequency of relapses between alcoholic and other drug users patients; (d) Correlate stress score and frequency of relapses; (e) Correlate salivary cortisol levels and frequency of relapses; (f) Correlate the ASSIST score with the frequency of relapses; (g) Correlate ASSIST score, anxiety, depression, perceived stress score, cortisol levels and frequency of relapses; and (f) determine the predictive variables of stress and relapses rates.

11

13 3.1. STUDY DESIGN AND SAMPLING

Observational Cross-sectional study; the sample were selected by convenience non-probabilistic sampling method.

3.2. PARTICIPANTS

A total of 65 patients were enrolled in the study. All individuals with substance use disorders (SUD) consecutively admitted to short-term detoxification unit at Casa de Saúde Bom Jesus, Psychiatry Department at Braga Hospital and Detoxifocation Unit at Matosinhos during period between September 2013 and April 2014. Patients were referred to the detoxification unities from outpatient follow-up services, emergency services, specialized addiction centers or as recommended by the therapist.

The project was submitted to the Local Commitee on Bioethics at Braga Hospital, Casa de Saúde do Bom Jesus and Detoxification Unit at Matosinhos for approval before the study initiation. The enrolled participants were explained about the objectives of the study according to Declaration of Helsinki for human biomedical research. No invasive method was performed; the saliva samples were collected with no harm or damage to the patient. Each participant was asked to sign a declaration of informed consent.

3.2.1. INCLUSION CRITERIA

Patients were included if the following criteria were satisfied: (a) age between 18 to 65 years, (b) ability to self-respond to PSS-10, (c) criteria for substance use disorders (SUD) according to ICD 10, (d) ASSIST score were higher than 5 points for drug users and more than 10 for alcohol users and (e) at least 3 or more days of abstinence.

3.2.2. EXCLUSION CRITERIA

All participants with (a) known endocrinology disorder (e.g.: Addison or Cushing disease), (b) pregnant women or taking oral oestrogen, (c) presence of oral lesions, (d) severe cognitive impairment and (e) under corticosteroids therapy were excluded for the present study.

14

For our study purpose, “Relapse” was considered when the patient re-initiates consumption after more than 4 weeks period without alcohol or drug use after or not inpatient detoxification [32-34].

3.3. EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

To accomplish the objectives of the study, two tasks where developed in both acute detoxification unities and in laboratory setting during planned period (Fig.3).

Figure 2: Experimental design and timeline

The total sample (N=65) was split into two groups according to primary substance of abuse:

Group 1: alcohol dependent patients (n=29) according to ICD-10 criteria.

Group 2: consumers of “other drugs” (opiates, cocaine, cannabis, amphetamines and benzodiazepines) (n=36), of which 23 had multiple substance abuse (Fig. 4).

Figure 3: Sample distribution according to main substance of abuse.

15

Tobacco was excluded as substance of abuse, considering that the patients are legally allowed to smoke during inpatient.

3.3.1. TASK 1: DATA ASSESSMENT

3.3.1.1. Sociodemographic data assessment

To obtain sociodemographic data, we administered a structured questionnaire interview. This questionnaire included data on gender, marital status, age and Graffar scale (1956) for socioeconomic data. This scale is subdivided in 5 categories with 5 degrees each namely (1) residential area; (2) comfort of accommodation; (3) profession; (4) sources of household income; (5) level of education. The total sum of the points obtained on the classification of five criteria gives us a final score that corresponds to Social status, as the following classification: Class I: Families whose sum of points from 5 to 9; Class II: Families whose sum of points from 10 to 13; Class III: Families whose sum of points from 14 to 17; Class IV: Families whose sum of points from 18 to 21 and Class V: Families whose sum of points from 22 to 25.

3.3.1.2. Clinical information

For clinical information we assessed the motive of admission, the number of previous admissions in detoxification unity, frequency of relapses, the presence of psychiatric comorbilities and current medical treatment for addiction or other psychiatric condition.

For confirmation or to get additional information, the medical files were consulted. 3.3.1.3. Assessment of substance use

Substance use was assessed with the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) an instrument with 8 brief questions developed for the World Health Organization (WHO) by an international group of substance abuse researchers; it is used to detect substance dependence and associated problems during the last 3 months. It is suitable for problems in primary and general medical care settings to provide interventions targeted to all substances. It covers 10 substances of abuse: alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines, inhalants, sedatives, hallucinants, opioids and other drugs. The first question screens lifetime use of substance of abuse; the following question assesses frequency of drug use during the last three months. The possible answers are rated in 5-points Likert scale: 0 – No or Never; 2- One or twice; 3 – Monthly; 4 - Weekly; 6 – Almost every day. The question 3 assesses the compulsive

16

behavior for substance use; question 4 about health, social, financial and legal problems. Question 5 asks about the failure to fulfill their duty. Question 6 and 7 assesses the friends and family concern and attempts to reduce or control the use. Question 8 asks about lifetime injecting use of drug. The score is the total sum of each item substance score: cut-off score for alcohol 0-10: low risk; 11-26: moderate risk (abuse) and 27+: high risk (dependence). For all other drugs, the cut-off score is: 0-3: non-problematic use (low risk); 4-26: abuse (moderate risk) and 27+: dependence (high risk) [35].

Additionally, we assessed the route of administration of the substance of abuse, the quantity of alcohol in grams using specific formula [36], duration of drug use and the frequency of relapses. To obtain the time duration of abstinence in days we calculated by difference between the interview date with last date consumptions; and duration of relapse in weeks by difference of the last date of relapse and last consumption date.

3.3.1.4. Assessment of Perceived stress

Perceived Stress Scale 10 (PSS-10) is a 10-items self-report tool used to assess the degree of appraised situation [37], specific events or experiences in life during the previous month. Each item has 5-point scale ranging from (0) – never; (1) – almost never; (2) – sometimes; (3) – fairly often to (4) – very often. The scores are obtained reversing the four positive stated items - 4, 5, 7 and 8: 0 equal to 4; 1 =3; 2=2; 3=1 and 4=0 and finally summing all 10 items.

3.3.1.5. Assessment of stress related comorbilities (e.g. anxiety and depression)

Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM-A) is a 14 items questionnaire scale used to evaluate the results of treatment of anxiety [38]. The interview was conducted by the researcher.

Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D) is a scale containing questions that allows to evaluate mood; it is commonly used to monitor the clinical progression and effectiveness of antidepressant treatment [39].

3.3.2. TASK 2: MATERIAL AND PROCEDURES FOR SALIVARY CORTISOL MEASUREMENT 3.3.2.1. Salivary Cortisol levels

Salivary cortisol levels are a reliable measure of hypothalamus—pituitary—adrenal axis (HPA) response to stress; it is used as a biomarker of psychological stress and related mental or physical disorders [40], as well as a diagnostic tool [41].

17

Saliva samples for cortisol analysis were collected from each patient into Salivette (containing neutral cotton swab) between 8-9 am under fasting condition and at 12-13 pm. After collection, saliva samples were centrifuged (2 min. at 2000g rotation), aliquoted and stored at -80 °C. Salivary cortisol levels (μg/l) were assayed using ELISA (Enzyme-linked Immuno Assay) from IBL, Ref: RE52611. The test is based on the competition principle between an unknown amount of antigen (cortisol) present in the samples and a fixed known amount of enzyme labeled antigen for the binding sites of a specific antibody coated onto each well.

3.3.2.2. Material

(1) 50, 200 and 1000 µl micropipettes (2) standards (3) controls (4) orbital shaker (400-600 rpm); (5) 8-channel micropipettor; (6) 96-well microtiter plates coated with specific antibody; (7) microtiter plate reader; (8) deionised water; (9) paper towels. All procedures were taken as recommended by the protocol and according to Good Laboratory Practices in order to maintain quality control and consistency.

3.3.2.3. Procedure

(1) 50 µl of each standard, control and sample are pipetted into its respective well in a microtiter coated plate (96 wells); (2) 100 µl of Enzyme Conjugate is pipetted into each well; the plate covered with adhesive foil for 2 hours incubation at room temperature (18 to 25ºC) on an orbital shaker (400-600rpm); (3) The adhesive foil is removed and the solution discarded; then each well is washed 4 times with 250 µl diluted washing buffer, removing the excess by tapping the inverted plate on paper towel; (4) 100 µl of TMB substrate solution is pipetted into each well, followed by 30 min incubation at room temperature on orbital shaker; (5) 100 µl of TMB stop solution is added into each well to stop substrate reaction and converting color from blue to yellow; (6) Optical density is then measured (within 15 min) in a microplate photoreader at 450 nm wavelength (with 650 nm as reference).

3.3.2.4. Analysis

To obtain the regression model that correlates the OD outputs with cortisol concentration (µg/l), we plotted (in Graphpad Prism5) each standard OD output (Y-axis, linear) with its correspondent cortisol concentration (X-axis, logarithmic). A nonlinear regression analysis was performed, obtaining the best fit curve with the model type: log (agonist) vs. response - variable slope model, which is mathematically described by the equation [Y = Bottom + (Top-Bottom) / (1 +10 ^ ((LogEC50-X) x hillslope))]. This mathematical model (equation) was fitted individually to

18

each plate, and used to extrapolate and calculate samples cortisol concentration using its correspondent OD output (Y variable) and solving the equation in order to X variable (concentration µg/l).

3.4. STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

To compare the mean scores between group of the alcoholics and other drugs users group or different variables were performed t-test for independent samples and one-way ANOVA to compare stress related parameter among three independent groups of drug and relapses if normally distributed. To determine the relationship between the score of perceived stress, cortisol levels, anxiety and depression scores, ASSIST score and frequency of relapse were carried out simple and multiple linear regressions. The level of significance was set to p< .05. Effect size was also determined.

19

21

4.1. SOCIO-DEMOGRAPHIC AND CLINICAL CHARACTERISTS

4.1.1. Descriptive statistics of socio-demographic and clinical variables

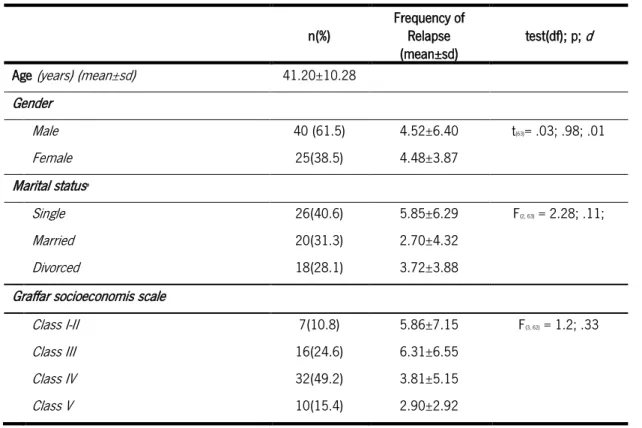

The participants in our sample present the following distribution: 61.5% males and 38.5 % females, with mean age of 41.20±10.28 years. Excluding one participant, according to marital status 40.6% were single, 32.3% married and 28.81% divorced. For socioeconomic (Graffar scale) status most participants belongs to class IV and class III with 49.2% and 24.6% respectively. Table 1: Participants characterization

n(%) Frequency of Relapse

(mean±sd) test(df); p; d Age (years) (mean±sd) 41.20±10.28

Gender Male 40 (61.5) 4.52±6.40 t(63)= .03; .98; .01 Female 25(38.5) 4.48±3.87 Marital statusa Single 26(40.6) 5.85±6.29 F(2, 63) = 2.28; .11; Married 20(31.3) 2.70±4.32 Divorced 18(28.1) 3.72±3.88

Graffar socioeconomis scale

Class I-II 7(10.8) 5.86±7.15 F(3, 62) = 1.2; .33

Class III 16(24.6) 6.31±6.55

Class IV 32(49.2) 3.81±5.15

Class V 10(15.4) 2.90±2.92

a n=64, outlier were removed

*p < .05

When compared with married and divorced patients, single individuals no differences were reported on number of previous relapses (F(3;59) = 2.28; p = .11), the same were found

among socioeconomic classes (F(3, 62) = 1.17; p= .33) and gender (t(63) = .032; p= .98; Cohen´s d=

.01) (Table 1).

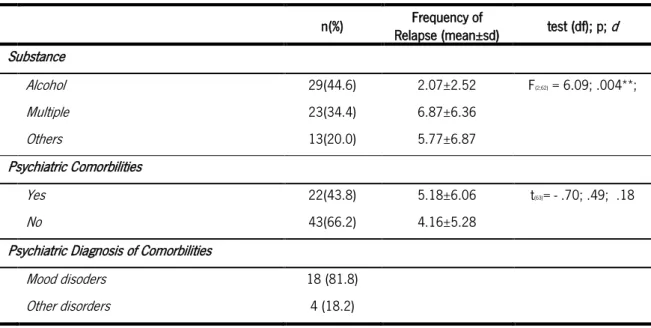

43,8% of patients reported comorbilities, mostly mood disorders (81.8%). Regarding different substances of abuse, multiple drug users had significantly higher rates of relapse when compared with alcoholic patients (F(2; 62)= 6.09; p = .004; Partial eta square = .16; Observed power = .872).

22 Table 2: Clinical characterization of participants

n(%) Frequency of

Relapse (mean±sd) test (df); p; d

Substance Alcohol 29(44.6) 2.07±2.52 F(2;62) = 6.09; .004**; Multiple 23(34.4) 6.87±6.36 Others 13(20.0) 5.77±6.87 Psychiatric Comorbilities Yes 22(43.8) 5.18±6.06 t(63)= - .70; .49; .18 No 43(66.2) 4.16±5.28

Psychiatric Diagnosis of Comorbilities

Mood disoders 18 (81.8)

Other disorders 4 (18.2)

*p < .05

From this data we found that the type of substances abuse has 16.4% of influence on frequency of relapses.(Table 2)

4.1.2.

Relationship between Graffar socioeconomic and assist score with anxiety, depression, perceived stress scale, cortisol and frequency of relapses

Using Pearson correlation test to determine the relationship between two variables; we found significant negative poor correlation between Graffar score with HAM anxiety scale score (r=- .27; p= .03) and Perceived stress score (r=- .32; p= .01). No statistical significant correlations were found with HAM-depression score, cortisol levels, total ASSIST score and frequency of relapses with Graffar scale (Table 3).

Table 3: Relationship of socioeconomic score and the ASSIST score with anxiety, depression and perceived stress score using Pearson correlation test.

Variable Graffar scale score Total ASSIST score

n r p n r p HAM-A 65 - .27 .03* 64 - .19 .13 HAM-D 65 - .22 .08 64 - .15 .24 PSS-10 65 - .32 .01* 64 - .11 .38 Cortisol 6 48 .15 .30 47 .08 .62 Frequency of Relapses 65 - .19 .13 64 .06 .65

ASSIST score total c 64 - .08 .53

b n=48; 17 missing cortisol measurement

c n=64; one excluded

23

For ASSIST score, no statistical significant correlations were met with all variables analyzed (Table 3).

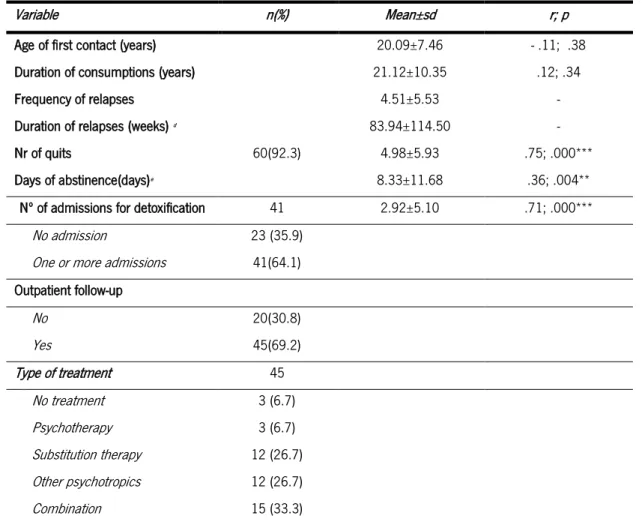

4.1.3. Assessment of addiction related variables

Assessing the history of drug use, we found that the average age of first contact with drugs was 20.09 ± 7.46 years with a history of 21.12±10.35 years of drug consumption. On average, the rate of relapses was 4.5 ±5.53 relapses. Sixty patients (92.3%) voluntarily attempted to quit the drug; the number of attempts was on average 4.98±5.93. Forty-one patients, corresponding to 64.1%, were admitted on average 2.92±5.10 times for acute detoxification, while the remaining 35.9% were admitted only once. We found a positive significant strong correlation between number of attempts to quit drug-abuse and number of admission for detoxification (Table 4).

Table 4: Assessment of lifetime addictive behavior, relapses, treatment history and relationship with relapses rates.

Variable n(%) Mean±sd r; p

Age of first contact (years) 20.09±7.46 - .11; .38

Duration of consumptions (years) 21.12±10.35 .12; .34

Frequency of relapses 4.51±5.53 -

Duration of relapses (weeks) d 83.94±114.50 -

Nr of quits 60(92.3) 4.98±5.93 .75; .000***

Days of abstinence(days)e 8.33±11.68 .36; .004**

Nº of admissions for detoxification 41 2.92±5.10 .71; .000***

No admission 23 (35.9)

One or more admissions 41(64.1) Outpatient follow-up No 20(30.8) Yes 45(69.2) Type of treatment 45 No treatment 3 (6.7) Psychotherapy 3 (6.7) Substitution therapy 12 (26.7) Other psychotropics 12 (26.7) Combination 15 (33.3)

dDuration of relapses (weeks) = (last date of drug use) - (date of last relapse) e Days of abstinence (days) = (interview date) - (last date of drug use)

24

After discharge from previous detoxification, 69.2% of the patients continued their follow-up in treatment centers. 33.3% were taking combination therapy (psychotropics, psychotherapy and or other treatments) while 26.7% were using substitution therapy with Methadone and/or Naltrexone and the same number of patients were taking other psychotropics (benzodiazepines, antipsychotics and antidepressants) (Table 4)

Table 5: ASSIST score, quantity and route of consumption.

Substance of abuse (n) ASSIST Score Quantity (g/day) Route of consumption (%)

Tobacco (53) 20.90±4.20 25.18±17.80f Smoke (100.0) Alcohol (38) 35.89±4.26 211.47±128.40g Drink (100.0) Cannabis (7) 35.57±4.50 3.43±3.04 Smoke (100.0) Cocaine (20) 33.6±6.04 1.22±1.04 Smoke (80.0) Opiate (25) 35.8±5,06 1.23±1.39 Smoke (60.7)

fNumber of pack-years = (packs smoked per day) × (years as a smoker) ggrams of alcohol= [(Volume of alcohol(ml)x degree of alcohol(%))x 0,8]/100[36]

In our cohort, alcohol was the main substance of abuse, either alone or in association with other drugs, followed by opiate and cocaine. In all cases, the participants had criteria for drug dependence according to the ASSIST score; these scores were 35.8±5.06 for opiate users; 33.6±6.04 for cocaine users, 35.57±4.50 for cannabis users and 35.89±4.26 for alcohol abusers. The main route of consumption was smoking for cannabis (100.0%) cocaine (80.0%), and opiate (60.7%). The following most used route was injection with 14.3% for opiate and 20.0% for cocaine users (Table 5).

4.1.4. ASSESSMENT OF CORTISOL AND PSYCHOMETRIC MEASUREMENT DATA

Figure 5, show independent sample t-test for comparison of means between alcohol and other drugs group; we found statistical significant difference on PSS 10 mean in alcoholic group (22.07±7.31) and other drug users group (25.75±4.67), (t (63) = 2.46; p= .02; d = .60) and morning cortisol (Fig.5) (see also Table 15 on attachments).

25

Figure 4: Comparison of mean of HAM-A, HAM-D and PSS-10 between alcoholic and other drug users group.

Comparing levels of morning cortisol between alcoholics (.52± .24) and other drugs group (.78± .37), significant differences were observed [t (46) = 2.83; p= .007; d= .83]. On contrary, no significant differences were found for afternoon cortisol levels between alcoholics (.54 ± .30) and other drug users (.70± .35) (Fig. 6).

Figure 5: Comparison of mean morning and afternoon cortisol level between alcoholic and other drugs group

Interestingly, data shows that abusers of alcohol presented lower scores in HAM-D, PSS-10 and lower levels of morning cortisol when compared to users of other substance of abuse (Fig 5 and 6) (see also Table 7 on attachments).

.

26

Comparing the influence of gender on average/mean of HAM-D, HAM-A, PSS-10 scores, we only found significant differences (t(63) = 2.03; p= .05; Cohen´s d = .49) on HAM-A scores, with females presenting higher mean (18.56±14.90) than males (12.40±9.59) (Fig.7) ,

Figure 6: Comparison of HAM-A, HAM-D and PSS-10 between males and females.

Men presented higher levels of cortisol than women in the morning and in the afternoon assessments [t(46)= 2.04; p = .05; Cohen´s d = .58 and t(52)= 2.01; p= .05;Cohen´s d= .59 respectively] (see also Table 16 on attachments)(Fig.8) .

Figure 7: Comparison of morning and afternoon cortisol between males and female

27

4.2. Relationship of perceived stress, anxiety, depression, cortisol and relapses

Table 8 shows the relationship between frequency of relapses and score of A, HAM-D score, PSS-10 score and cortisol. We found significant positive correlations on HAM-A, HAM-HAM-D and PSS 10. in the total sample. When the groups were divided by substance of abuse, we found only positive correlations for the “other drugs” group in HAM-A and HAM-D. In alcohol group we did not find any significant correlation (Table 8).

Table 6: Correlation between frequency of relapses and HAM-D, HAM-A, PSS-10, Cortisol levels in alcoholic and other drugs users.

Variable

Frequency of Relapses

Total Alcohol Other drugs

n r p n r p n r p HAM-A 65 .34 .01** 29 .02 .91 36 .44 .01** HAM-D 65 .32 .01** 29 .12 .52 36 .34 .04* Cortisol 48 - .05 .72 22 .13 0.58 26 - .37 .07 PSS-10 65 .30 .015* 29 .26 .17 36 .25 .14 *p< .05 and **p< .01

In what regards gender, we found significant statistical positive correlation between frequency of relapse with perceived stress, anxiety and depression scale on males. In contrast, females did not show any significant correlation in the parameters analyzed (Table 9). In males, higher frequency of relapses is related with higher levels of depression, anxiety and perceived stress. No correlations were observed with cortisol levels (Table 9).

Table 7: Comparison of Pearson correlation between frequency of relapses and PSS-10, Cortisol, HAM-A,

HAM-D and relapses by gender.

Frequency of Relapses

Variables Males Female

n r p n r p PSS-10 40 .39 .01** 25 .17 .42 Cortisol 34 .08 .65 20 - .05 .84 HAM-D 40 .45 .004** 25 .08 .84 HAM-A 40 .54 .000*** 25 .14 .51 *p < .05; **p< .01; ***p < .001

Table 10 shows the comparison of Pearson correlation between days of abstinence and PSS-10, cortisol, HAM-D, HAM-A, ASSIST score and number of relapses. The number of relapses

28

correlates with total days of abstinence. This correlation was not observed when alcoholics were analyzed alone. No other significant correlations were found. (Table 10).

Table 8: Comparison of Pearson correlation between time(days) of abstinence and PSS-10, A, HAM-D, Relapses and Cortisol in total sample, alcoholic and other drugs group.

Time (days) of abstinence

Variables Total Alcoholic group Other drugs

n r p n r p n r p PSS-10 61 - .11 .41 28 - .26 .19 33 - .14 .43 Cortisol 50 - .10 .49 23 .13 .55 27 - .19 .34 HAM-D 61 .12 .37 28 - .12 .56 33 .18 .32 HAM-A 61 .12 .38 28 .30 .13 33 .21 .24 Relapses 61 .36 .004** 28 - .09 .65 33 .41 .02* *p< .05 and **p< .01

4.3. PREDICTIVE VARIABLES OF STRESS AND RELAPSES

Table 11 shows the predictive model of dependent variable (PSS-10) for the total sample, where 42.9% of factors related to perceived stress are explained by the model (R= .655; R2 = .429); importantly, this model can be considered reliable (ANOVA: F(3,47)= 8.08; p <.000)). In the total sample, controlling other variables, increases in one point of anxiety score translate in an increase of .22(C.I.95%[.09; .35]) in perceived stress scale; while in the same conditions for cortisol was increase 4.33 (C.I.95% [.004; 8.66]) and decrease a significant decrease in perceived stress in .39 (C.I.95% [- .77;- .01] ) for Graffar scale. The relapse rate was not a good predictor variable for stress.

Table 9: Predictive model of stress and relapses in total sample (n=48)

*p < .05; **p < .01

In the alcoholic group, all variables in the model are good predictor of perceived stress; importantly, 74.0% of the dependent variable (PSS-10) can be explained by anxiety, Graffar score, cortisol and the relapse rates (Table 12).

PSS-10 B (C.I. 95%) S.E ß t; p HAM-A .22 ( .09; .35) .06 .43 3.42; .001** Graffar score - .39 (- .77;- .01) .19 - .25 -2.06; .05* Cortisol 4.33 ( .004; 8.66) 2.15 .24 2.02; .05* Freq. Relapses .19 (- .08; .46) .13 .18 1.42; .16 R2Adjusted; R2 .38; .43 F(df1; df2); p F(4, 47)= 8.08; < .001

29

Table 10: Predictive model of stress and relapses in alcoholic group (n=22)

*p < .05; **p < .01

For this group, comparing to the total sample, the frequency of relapse was a significant predictor, showing that any increase in this variable we can observe almost one point increase in perceived stress According with our data in alcoholic group, controlling other variables, increases in one time of the frequency of relapse, the perceived stress scale increases almost one point [.82 (C.I. 95% [- .11; 1.53])] ; for each ug/l of salivary cortisol level was expected an increase in 11,8 points of perceived stress score. the same trend was observed for Graffar scale and anxiety score. Socioeconomic status (as measured by Graffar score) and levels of anxiety (as assessed by HAM-A) [.30 ( C.I. 95%: .12; .35)] [- .76 (C.I. 95%: -1.24;- .29)] were the main predictors of perceived stress presenting a strongly statistical significant p-value (p< .01(p= . 003)) (Table 12). Table 11: Predictive model of stress and relapses in other drugs group (n=26)

In “other drugs” group, the used model did not identify any significant predictor of perceived stress [R2 = .22; ANOVA (F(4; 25)= 1.44; p= .26)] (Table 13).

For relapses rates as dependent variable, the model was not reliable and the variables Graffar score, cortisol, HAM-A were not good predictors (R2 = .14; R²adjusted = .08; ANOVA F(3;47) =

2.43; p= .08) for the total sample. Only the perceived stress was significant predictor (Table 14).

PSS-10 B (C.I. 95%) S.E ß t; p HAM-A .30 ( .12; .35) .09 .47 3.49, .003** Graffar score - .76 (-1.24;- .29) .23 - .48 -3.39, .003** Cortisol 11.79 (3.27; 20.31) 4.04 .38 2.92; .01** Freq. Relapses .82 (- .11; 1.53) .34 .32 2.42; .03* R2Adjusted; R2 .67; .74 F(df1; df2); p F(4 21)= 11.88; <.001 PSS-10 B (C.I. 95%) S.E ß t; p HAM-A .11 (- .05; .28) .08 .30 1.43; .17 Graffar score .06 (-,53; .65) .29 .05 .22; .83 Cortisol .06 (-5.46; 5.58) 2.66 .01 .02; .98 Freq. Relapses .19 (- .14; .53) .16 .27 1.19; .25 R2Adjusted; R2 .07; .22 F(df1; df2); p F(4 25)= 1.44; .26 (> .05)

30 Table 12: Predictive model of relapses in total sample (n=48)

*p< .05

The results were similar when alcoholics and other drug users were analyzed separately. [Alcoholics: R2 = .26 ANOVA F(3;, 21) = 2.05 p=.14; Other drug users: R² = .31; ANOVA F(3;

22)= 3.24; p= .04] (Tables 15 and 16).

Table 13: Predictive model of relapses in alcoholic group (n=22)

p < .05

Table 14: Predictive model of relapses in other drugs users (n=26)

Freq. Relapses B (C.I. 95%) S.E ß t; p

Graffar score .10 (- .59; .34) .22 - .07 - .67; .66

Cortisol -1.56 (-6.48; 3.35) 2.44 - .09 .29; .53

PSS-10 .31 ( .03; .60) .14 .34 2.17; .03*

R2Adjusted; R2 .08; .14

F(df1; df2); p F(3 47)= 2.43; .08 (> .05)

Freq. Relapses B (C.I. 95%) S.E ß t;p

Graffar score .34 ( .002; .68) .16 .56 1.19; .05*

Cortisol -2.23 (-8.30; 3.85) 2.89 - .19 -1.01; .45

PSS-10 .23 ( .01; .44) .10 .59 1.73; .04*

R2Adjusted; R2 .13; .26

F(df1; df2); p F(3 21)= 2.05; .14 (> .05)

Freq. Relapses B (C.I. 95%) S.E ß t; p

Graffar score - .54(-1.27; .19) .35 -.28 -1.52; .14

Cortisol -4.21 (-11.03; 2.61) 3.29 -.24 .23; .21

PSS-10 .42 (- .11; .95) .26 .30 1.95; .12

R2Adjusted; R2 .21; .31

31

33 5.1. DISCUSSION

The main goal of our study was to determine the relationship of stress and stress-related factors on the frequency of relapses in order to search the predictive variables of such association. To the best of our knowledge, the neuropsychological instruments herein used are not commonly used in addiction setting. Although there have been several attempts to design a relapse model, both in animal and human laboratory experiments, this has never been successfully done [42, 43].

By exploring socio-demographic factors on frequency of relapse, we found no differences on gender, marital status and socioeconomic class; these results are in accordance with other studies addressing such variables [44-46]. Other factors, such as educational level, employment and general satisfaction, appeared to increase the likelihood for a better outcome and decreased relapse, as previously suggested [47]; in fact, our finding show that high socioeconomic status is inversely related with stress and anxiety, which are drivers for relapse, seem to point in that direction. In the same vein, previous studies had identified sociodemographic variables such as age, gender, marital status socioecoenomic level, religious practice and social functioning as predictors of the outcome in addictive disorders[46, 48].

Regarding drug abuse history, we found that the type and number of substances of abuse has effect on the rate of relapses. This agreed with findings showing that subjects with more than one substance of abuse are more vulnerable to relapse[48]. The number of admissions was strongly related with the frequency of relapses as well as the number of attempts to quit the drug. In fact, a previous study showed that fewer number of treatments was a better outcome predictor, mainly in alcoholic patients [49].

According to other studies, the most prevalent comorbidity among users of alcohol and other drugs were emotional disorders (depression and anxiety). Considering these as precipitating factors of addictive behaviors, it seems logical that they may influence treatment outcomes [44, 49, 50] as measured by frequency of relapses. It has been also proven that addicts are more likely to have depressive and anxiety symptoms, mainly during withdrawal and abstinence period. During inpatient abstinence period, a craving assessment instrument could predict relapse outcome after discharge [50]; hence the appropriate interventions for such factors are of relevance in the clinical context. The present data suggests that the existence of

34

complex interplays between these emotional factors and frequency of relapses, on which perceived stress may constitute an important mediator. Moreover, the stressful lifetime events may be an etiological factor for psychopathological comorbilities such as depression and anxiety disorders; these events, are likely to be triggers for initiation and maintenance of addictive behaviors[51, 52], which is determinant for individual self-efficacy and coping after discharge[53].

Evidence in literature shows that the frequency of relapse is high both for alcoholic, cocaine and heroin addicts [54, 55]. Interestingly, the present results seem to contradict this fact; indeed, we found a significant difference in the risk for relapse between abusers of alcohol and user of others drugs, with higher rates observed on multiple and other type of drugs and lesser in alcoholics groups. Of notice, as a partial explanation for this discrepancy, is the observation that while the frequency of relapses in alcoholics is not correlated with scores of anxiety, depression and perceived stress, whereas in the users of other drugs there was a positive correlatation. Interestingly, a previous study of Kreek and colleagues found that levels of anxiety and depression were indicative of withdrawal symptoms[56].

When we correlated the frequency of relapses with anxiety, depression scores and time/duration of abstinence we found that they are positively related but this relationship differs between alcoholic and other drug users, which is in concordance with several studies in literature[51, 52, 57-60]. We also assessed the HPA axis regulation, by measurement of awakening and afternoon salivary cortisol levels [55, 61]; in our sample, we found the morning cortisol measurement was significantly higher in “other drugs” users group than in alcoholic group. Different classes of drugs activate the reward, craving and relapse neurocircuitry in different manner, so the impact on HPA axis may also differ [4, 56, 62]. This differential HPA axis response may also contribute to the observed differences in relapse rates between alcoholic and other drug users. More studies are needed to investigate the underlying mechanisms that could explain these differences in the HPA axis response and whether this is a useful biomarker in the clinical setting.

35 5.2. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The study design - cross-sectional study - is limited to one time observation, failing to capture other related factors during abstinence period. Absence of the control group composed by long course abstinent patient would be of relevance to compare stress outcomes. It would also be relevant to assess cortisol levels in the first 48 hours of admissions and last day of discharge to better understand the pattern of HPA axis dysregulation in substance abuse patients, as indicators to better design post-discharge treatment. To overcome these limitations, we propose future prospective longitudinal study at least one year follow-up, with the inclusion of the control group randomly selected sample. It would be also valuable to use other psychometric measurement to assess, e.g. craving intensity, compulsivity; impulsivity, withdrawal symptoms, coping strategies and cross them with biological and imaging findings in order to understand changes in the brain and their impact on addiction and relapse.

The fact that the study was largely based on self-reported answers/questionnaire is also a limitation. Finally, it is important to note that the saliva collection was performed in inpatient context and under psychopharmacotherapy; these obviously are factors that may have influenced the results.

5.3. CONCLUSIONS

From the above findings we can conclude that: i) the sociodemographic variables such as gender, marital status and socioeconomic status did not affected the frequency of relapse; ii) the type of drug has influence on relapse frequency. The abuse of multiple substances and all other drugs has an impact on relapses rates, with less relapses for alcohol abusers; iii) the number of attempts to quit drugs, days of abstinence and number of admission for detoxification were strongly related with the frequency of relapses; iv) perceived stress was significantly higher in users of other drugs than alcoholics; v) the morning cortisol levels was significantly higher in other drugs users than alcoholics while on afternoon measurements the values did not differ between groups; vi) females presented higher anxiety scores than males, but lower cortisol levels; vii) there were significant relationship between anxiety, depression and perceived stress with relapse rates in users of distinct drugs of abuse, but not in alcoholics; viii) comparing the relapses rate with cortisol and anxiety, depression and perceived stress, only in males were found

36

significant correlations; ix) although the frequency of relapses, Graffar, anxiety and depression scores are good predictors of perceived stress, they are not good predictors of relapses rates.

37

39

1. Piazza, P.V. and M.L. Le Moal, Pathophysiological basis of vulnerability to drug abuse: role of an interaction between stress, glucocorticoids, and dopaminergic neurons. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology, 1996. 36(1): p. 359–78.

2. Weiss, F., et al., Compulsive drug-seeking behavior and relapse. Neuroadaptation, stress, and conditioning factors. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2001. 937: p. 1-26.

3. Koob, G.F. and N.D. Volkow, Neurocircuitry of Addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology Reviews, 2010. 35: p. 217-238.

4. Gardner, E.L., Addiction and Brain Reward and Antireward Pathways. Adv Psychosom Med, 2011. 30: p. 22–60.

5. Volkow, N.D., G.-J. Wang, and J.S. Fowler, Addiction Circuitry in the Human Brain. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxico, 2012. 52: p. 321-336.

6. Goeders, N.E., The impact of stress on addiction. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 2003. 13: p. 435-441.

7. Feil, J., et al., Addiction, compulsive drug seeking, and the role of frontostriatal mechanisms in regulating inhibitory control. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2010. 35(2): p. 248-75.

8. Sinha, R., Modeling stress and drug craving in the laboratory: implications for addiction treatment development. Addiction biology, 2009. 14(1): p. 84-98.

9. George, O., M. Le Moal, and G.F. Koob, Allostasis and addiction: role of the dopamine and corticotropin-releasing factor systems. Physiol Behav, 2012. 106(1): p. 58-64. 10. Hyman, S.E. and R.C. Malenka, Addiction and the brain: The neurobiology of compulsion

and its persistence. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2001. 2: p. 695-701.

11. Breese, G.R., R. Sinha, and M. Heilig, Chronic alcohol neuroadaptation and stress contribute to susceptibility for alcohol craving and relapse. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2011. 129(2): p. 149-171.

12. Monras, M., et al., Assessing coping strategies in alcoholics: Comparison while

controlling for Personality disorders, Cognitive impairment and Benzodiazepine misuse. Adicciones 2010. 22(33): p. 191-198.

13. Back, S.E., et al., Reactivity to laboratory stress provocation predicts relapse to cocaine. Drug Alcohol Depend, 2010. 106(1): p. 21-27.

14. Jane, S., Pathways to repalse: the neurobiology and stress-induced relapse to drug-taking. J Psychiatry Neurosci, , 2000. 25(2): p. 125-136.

15. Diclemente, C.C.H., M. A. Rounsaville, D., Relapse Prevention and Recycling in Addiction. Addiction Medicine, 2011. 1: p. 7765-79.

16. Mattoo, S.K., S. Chakrabarti, and M. Anjaiah, Psychosocial factors associated with relapse in men with alcohol or opioid dependence The Indian journal of medical research, 2009. 130(6): p. 720-8.

17. Haass-Koffler, C.L. and S.E. Bartlett, Stress and addiction: contribution of the corticotropin releasing factor (CRF) system in neuroplasticity. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience, 2012. 5(91).

18. Junghanns, K., et al., Cortisol awakening response in abstinent alcohol-dependent patients as a marker of HPA-axis dysfunction. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2007. 32(8-10): p. 1133-7.

19. Sinha, R., The role of stress in addiction relapse. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 2007. 9(5): p. 388-95.

20. Becker, H.C., Alcohol Dependence, Withdrawal, and Relapse. Alcohol Research & Health, 2008. 31(4).

40

21. Rodrigues, J., et al., Mechanisms of initiation and reversal of drug-seeking behavior induced by prenatal exposure to glucocorticoids. Molecular psychiatry, 2012. 17(12): p. 1295-1305.

22. Thadani, P.V., The intersection of stress, drug abuse and development. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2002. 27(1-2): p. 221-30.

23. Sinha, R. and G. Wand, Stress and the HPA Axis: Role of Glucocorticoids in Alcohol Dependence. Current Reviews, 2012: p. 468-483.

24. Morgado, P., et al., Perceived Stress in Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder is Related with Obsessive but Not Compulsive Symptoms. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 2013. 4: p. 1-6. 25. Fox, H.C., et al., Frequency of recent cocaine and alcohol use affects drug craving and

associated responses to stress and drug-related cues. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2005. 30: p. 880-891.

26. Richards, J., et al., Biological Mechanisms Underlyng the Relationship between Stress and Smoking: State of the Science and Directions for Future Work. Biol Pschol., 2012. 88(1): p. 1-12.

27. Goeders, N.E., Stress and Drug Craving. . Elsevier, 2010: p. 310-315.

28. Dedovic, K., et al., The brain and the stress axis: the neural correlates of cortisol regulation in response to stress. Neuroimage, 2009. 47(3): p. 864-71.

29. Murphy, A., et al., The detrimental effects of emotional process dysregulation on decision-making in substance dependence. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience, 2012. 6(101): p. 1-24.

30. Dias-Ferreira, E., et al., Chronic stress causes frontostriatal reorganization and affects decision-making. Science, 2009. 325(5940): p. 621-5.

31. Sinha, R., New findings on biological factors predicting addiction relapse vulnerability. Curr Psychiatry Rep, 2011. 13(5): p. 398-405.

32. Shalev, U., J.W. Grimm, and Y. Shaham, Neurobiology of Relapse to Heroin and Cocaine Seeking: A Review. Pharmacol Rev, 2002. 54(1): p. 1–42.

33. Adinoff, B., et al., Time to Relapse Questionnaire (TRQ): A Measure of Sudden Relapse in Substance Dependence. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse, 2010. 36(3): p. 140–149.

34. Chung, T. and S.A. Maisto, Relapse to alcohol and other drug use in treated adolescents: review and reconsideration of relapse as a change point in clinical course. Clin Psychol Rev, 2006. 26(2): p. 149-61.

35. Humeniuk, R., et al., Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking And Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Addiction, 2008. 103(6): p. 1039-47.

36. Porto, A. and L. Oliveira, Tabela da Composição de alimentos. 2007: p. 112-114. 37. Cohen, S., T. Kamarck, and R. Mermelstein, A Global Measure of Perceived Stress.

Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 1983. 24(4): p. 385-396.

38. Bruss, G.S., et al., Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale Interview guide: joint interview and test-retest methods for interrater reliability Psychiatry research, 1994. 53(2): p. 191-202. 39. Zimmerman, M., I. Chelminski, and M. Posternak, A review of studies of the Hamilton

depression rating scale in healthy controls: implications for the definition of remission in treatment studies of depression The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 2004. 192(9): p. 595-601.

40. Hellhammer, D.H., S. Wüst, and B.M. Kudielka, Salivary cortisol as a biomarker in stress research. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 2009. 34(2): p. 163-171.

41. Gozansky, W.S., et al., Salivary cortisol determined by enzyme immunoassay is preferable to serum total cortisol for assessment of dynamic hypothalamic--pituitary--adrenal axis activity. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf), 2005. 63(3): p. 336-41.

42. Bossert, J.M., et al., Neurobiology of relapse to heroin and cocaine seeking: an update and clinical implications. Eur J Pharmacol, 2005. 526(1-3): p. 36-50.