Revista

de

Administração

http://rausp.usp.br/ RevistadeAdministração51(2016)310–322

Marketing

The

commercial

cycle

from

the

viewpoint

of

operant

behavioral

economics:

effects

of

price

discounts

on

revenues

received

from

services

O

ciclo

comercial

visto

pela

economia

comportamental

operante:

Efeitos

dos

descontos

nos

pre¸cos

sobre

a

receita

recebida

de

servi¸cos

El

ciclo

comercial

desde

la

perspectiva

de

la

economía

conductual

operante:

efectos

de

los

descuentos

de

precio

en

los

ingresos

de

servicios

Rafael

Barreiros

Porto

∗UniversidadedeBrasília,Brasília,DF,Brazil

Received23January2014;accepted11February2016

Abstract

Therelationshipbetweensupplyanddemandgeneratescommercialcycles.Operantbehavioraleconomicsexplainthatthesecyclesareshaped bythree-termbilateralcontingencies–situationsthatcreatesupplyanddemandresponsesandwhich,inturn,generatereinforcingorpunitive consequencesthatcanmaintainormitigatethese.Researchshowshowthecommercialcycleofacompanyoccursandinvestigateshowprice discountsaffectbasicanddifferentiatedservicerevenuesaccordingtoseasonality.Basedonalongitudinaldesign,twotime-seriesanalyseswere performedusingtheARIMAmodel,whileanotherwascarriedoutusingaGeneralizedEstimatingEquationsdividedintoseasonalcombinations. Theresultsshow,amongotherthings,(1)thatacompanyhandlesmostofthemarketingcontextstrategiesandprogrammedconsequencesof servicesusedbyconsumers,creatinganewcommercialsituationforthecompany,(2)theeffectsofpricediscountsonsophisticatedserviceshave apositiveimpactandproducehigherrevenuesduringthelowseason,whilethoserelatedtobasicserviceshaveagreaterimpactandproduce greaterrevenueduringthehighseason;and(3)theseasonalityofthegreatestpurchasingintensityexertsamorepositiveinfluenceonrevenues thantheseasonalityofdemandcharacterizedbyheterogeneousreinforcements.Thesefindingsareusefulfortheadministrationofpricediscounts togeneratemaximumrevenueandmakeitpossibletohaveabetterunderstandingofthewaythecommercialcycleofacompanyfunctions. ©2016DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP. PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBYlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Keywords: Commercialcycle;Behavioraleconomics;Revenue;Pricediscount;Seasonality;Servicemarketing

Resumo

Asrelac¸õesentreofertaedemandageramcicloscomerciais.Aeconomiacomportamentaloperanteexplicitaqueelessãoformadosporcontingências bilateraisdetrês termos–contextoscriadores decondic¸õesàsrespostasdo ofertanteedemandanteque,porsua vez,geramconsequências reforc¸adorasoupunitivascapazesdemantê-lasouatenuá-las.Apesquisademonstracomoocorreociclocomercialdeumaempresa,averigua oefeitodosdescontosdeprec¸onareceitadeservic¸osbásicosediferenciados comdiferentessazonalidades.Comdelineamentolongitudinal, fizeram-seduasanálisesemsériestemporaiscommodeloARIMAeoutracomEquac¸õesdeEstimativasGeneralizadasdivididasemcombinac¸ões desazonalidades.Osresultadosdemonstram,dentreoutros,queaempresamanipulaboapartedoscontextosdemarketingedasconsequências programadasdeusodeservic¸opelosconsumidoresdaempresa,criaumnovocontextocomercialparaela;osefeitosdosdescontosemservic¸os sofisticadossãopositivamentemaioresnareceitadurante embaixatemporada,enquantodosservic¸osbásicossãopositivamentemaioresem

∗Correspondenceto:UniversidadedeBrasília,CampusUniversitárioDarcyRibeiro,70910-900Brasília,DF,Brazil.

E-mail:rafaelporto@unb.br

PeerReviewundertheresponsibilityofDepartamentodeAdministrac¸ão,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸ãoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeSãoPaulo –FEA/USP.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rausp.2016.06.005

altatemporada;easazonalidade demaior intensidadedecompra exercemaior influênciapositivasobreareceitado quea sazonalidadede heterogeneidadedereforc¸osdaquelesque compram.Osresultadosauxiliamagestãodedescontonagerac¸ãodamáxima receitaepermitem compreenderocomportamentodociclocomercialdeumaempresa.

©2016DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP. PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Palavras-chave:Ciclocomercial;Economiacomportamental;Receita;Descontoemprec¸o;Sazonalidade;Marketingdeservic¸o

Resumen

Lasrelacionesentreofertaydemandagenerancicloscomerciales.Laeconomíaconductualoperanteexplicaqueéstosseformanporcontingencias bilateralesdetrestérminos-contextosquecreancondicionesparalasrespuestasdeofertaydedemandaque,porsuparte,danorigenaconsecuencias querefuerzanopunen,yquesoncapacesdemantenerlasomitigarlas.Elestudiodemuestracómoseproduceelciclocomercialdeunaempresa yaveriguaelefectodelosdescuentosdepreciosenlosingresosdeserviciosbásicosydiferenciadosendistintasestacionalidades.Pormediode dise˜nolongitudinal,sellevaronacabodosanálisisenseriesdetiempoconmodeloARIMAyotroconecuacionesdeestimacióngeneralizadas divididosencombinacionesdeestacionalidad.Losresultadosmuestranqueelofertantemanejaloscontextosdemarketingylasconsecuencias programadasdelautilizacióndeserviciosporlosdemandantes,creandounnuevoentornocomercialparaél;losefectosdelosdescuentosen serviciossofisticadossonpositivamentemásaltosenlosingresosdurantelatemporadabaja,mientrasquedescuentosdeserviciosbásicossonmás altosypositivosentemporadaalta;ylaestacionalidaddemayorvolumendecomprasejerceunainfluenciamáspositivaenlosingresosquela estacionalidaddeheterogeneidadderefuerzosdelosquecompran.Losresultadoscontribuyenalagestióndedescuentosparagenerarmayores ingresosypermitencomprenderelcomportamientodelciclocomercialdeunaempresa.

©2016DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP. PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Esteesunart´ıculoOpenAccessbajolalicenciaCCBY(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Palabrasclave: Ciclocomercial;Economíaconductual;Ingresos;Descuentoenprecios;Estacionalidad;Marketingdeservicios

Introduction

Thedifferentiationsofservicesareatthecoreofanydebate about the exclusivity, luxury and sophistication that a com-panycanoffer consumers(Brun &Castelli, 2013; Veríssimo &Loureiro,2013).However,ingeneral,theseservicescharge higherpricessincetheyofferconsumersgreaterbenefits(Kohli & Suri, 2011). On the other hand, the supply of basic ser-vicesthatsucceedinattractingademandarelessexpensiveand makeitpossibletomatchsupplyinrelationtoothercompetitor servicesuppliers(Abrate,Fraquelli,&Viglia,2012).Between oneextremeandanother of acompany’sservice portfolio,if the price discounts are well applied (Yao, Mela, Chiang, & Chen,2012),thesecanincreasemorethanproportionallythe

numberofconsumersas comparedtothenon-implementation

of such actions. A company that offers a range of market

products(Elmaraghy&Elmaraghy,2014)thatinclude differen-tiatedandbasicservices,combinedwithanadequatediscount policy,canincrease their revenueand, inturn,their financial profits.

However,eachserviceprovidedbythesamecompanycan

involve different consumers. These may face restrictions as regardspayingthecontractpriceofferedanddependonaprice discounttobeabletomakepurchases(Kohli&Suri,2011).This, inturn,hasadifferentimpactaccordingtotheseason surround-ingthecompanyofferings.Thus,thedemandforaservicetends tooscillate(Hanssens,Parsons,&Schultz,2003),withlowand highmomentsandwithor withoutaheterogeneousstructure. Inordertomeetdemand,supplyisthereforecontrolledbythe availabilityofthenumberofservices,theirdifferentials,periods whentheseareofferedandpricesgiventothem.Thus,revenue

management (Talluri &Ryzin, 2005)ends upcontrolling the cashflowsfrom theservicesandthesecanappealtoalarger segmentofconsumers,therebyensuringprofits.

In the hospitality industry, managers of hotels, resorts, flatsandguesthouses experience thisroutineon adailybasis (Menezes & Silva, 2013). During the low season, reduced pricesareusuallyofferedtogeneratesufficientaccommodation occupancyratesandtherebyboostincome,thoughthisisnot necessarily thecaseforallhabitationunits,especiallyas het-erogeneityexistsbetweendifferentconsumers.Pricevariations attractacertaingroupofconsumersmorethananotherandthese mayormaynotbeeffectiveingeneratingthemaximumpossible revenue.

InadditiontoService-DominantLogic(SDL)inmarketing (Lusch&Vargo,2014),whereinteractionbetweentheconsumer andthecompanyisessentialinordertoattainbettercompany performances,theconsumersandthecompaniesco-createand

co-produce theservicesoffered.By meansof knowledgeand

ability,managercanoperationalizethesupplyofservices,inthe hopeofgeneratinggreaterrevenuesandprofitsforthecompany, whichtheywillonlydoifconsumerspayfortheirservices.This researchusesatheoreticalframeworkthatisbothcoherentand complementarytoSDL.Itiscoherentbecauseitmeetsallthe

basic SDL requirementsand it complementsSDL because it

addsbehavioralaspectstotheconsumer–companyrelationship, bringing together empirical findings on an individual analy-sis level with elements on an organizational and contextual level.

forenterprisesandhowlongtheseeffectswill last.Thisisat the heart of the working ability of a marketing professional (Theodosiou,Kehagias,&Katsikea,2012),whichmayormay not be efficient and effective (Keh, Chu,& Xu, 2006). This researchshowswhatcanbedoneinsuchasituation.The spe-cificobjectiveofthisresearchwastoevaluatetheeffectthatprice discountshaveonrevenuederivedfromdifferentiatedandbasic servicesduringdifferentseasons.In generalterms,theaimof thisstudywastoshowhowthecommercialcycleofacompany operatesfromanoperanteconomic-behavioralviewpoint,with theinvestigationofwhatmarketingprofessionalsactuallydoto stimulatesalesofservices.Thus,thisworkservesasanaidto servicemanagerswhoaimtoincreasetheirincomeandadjust theirpricestomeetthedemandforeachoneoftheirservices.

Operantbehavioraleconomics:explainingthe relationshipbetweenthesupplyanddemandof products/servicepricing

An area known as behavioral economics has researched

a wide variety of firm-related issues, both from a

cogni-tive(Angner&Loewenstein,2010)andanoperantviewpoint (Madden, 2000). Both adopt the premise of actors having boundedrationality(Simon,1972).However,thelatter concen-tratesmoreontherelationshipexperiencesbetweenthebehavior

and consequences to consumers, entrepreneur, investors and

managerswhentheyareindividualeconomicunits–whichcan includedaggregateddata(Pindyck&Rubinfeld,2009)–than ontheirthoughtprocesses,withgreateremphasisontheformer. Theoperantperspectivesupportstherelevanceofaneoclassical analysistounderstandeconomicbehavior,butnotinanacritical way.Onthecontrary,thisshowsthat,evenwithouttakinginto

accountrationalassumptions,themicro-economicphenomena

can be explained by means of the evolutionary relationships between behavior andits environment in asingle behavioral theoreticalframework(Foxall,2015).

In actualterms,the theories involvedinthisareaare con-cernedwithdescribingandexplaininghowenvironmentscreate thenecessaryconditionsfortheseeconomicunitbehavior

pat-terns to occur and the consequences of these relationships

(Franceschini & Ferreira, 2013). In addition, these investi-gateconsumerpatterns,expenses,savings,investments, brand choices,thecontextsthatcanaffectthese(e.g.pricediscounts, income)aswellastheconsequencesoftherelationshipsoftime andspacebetweenbehavioralpatternsandtheircontexts;which mayormaynotbemediatedbythesocialenvironment(Foxall, 2010;Foxall,Oliveira-Castro,James,&Schrezenmaier,2007; Franceschini&Ferreira,2013;Madden,2000).

In spite of the fact that this economic area has

mathe-matically and empirically shown the relationships that exist betweentheabove-mentionedconcepts(Pindyck&Rubinfeld, 2009),thereisnointegratedmodel thatcanexplainwhyand how these are related. On the otherhand, by using an oper-antapproach,combinedwithtraditionalDarwinianprinciples, abehavioralanalysisrepresentsasolidbasis(Oliveira-Castro& Foxall,2005).Itusesconceptsandfindingsproducedthrough experimentalresearch,usuallyconductedinlaboratories,testing

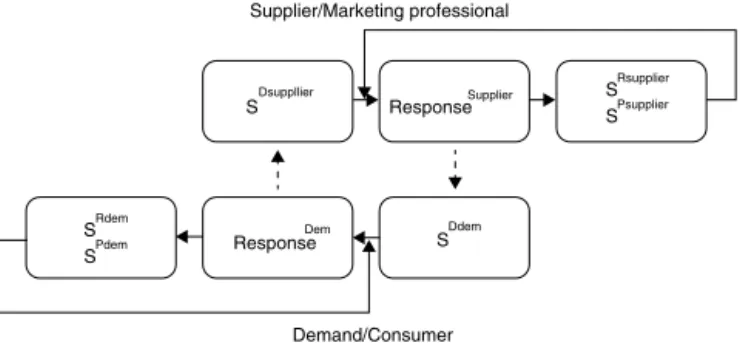

Supplier/Marketing professional

Demand/Consumer

SDsuppllier ResponseSupplier S Rsupplier

SPsupplier

SDdem ResponseDem

SRdem SPdem

Fig.1.Bilateralcontingencies(Foxall,1999),adaptedbytheauthor.

bothhumanaswellasinfrahumansubjects[e.g.:monkeys,rats (Baum, 2005)],that translate andspecify economic concepts intobehavioraloperations.Thishasmadeitpossibletoexplain andintegrateinnumerableeconomicphenomenainamore sub-stantialandparsimoniousmanner.

The conceptual model most often used is described by

Skinner (1974) as being a3-term contingency, that specifies theconditions(Term1)forwhicharesponse(Term2)produces oneorseveralconsequence(s)(Term3).Thismodelwasduly complementedandcontextualizedtoillustratetherelationship betweenindividualeconomicunits(e.g.consumer,family, com-pany)byFoxall(1999)–ascanbeseeninFig.1.Thisinvolves a3-termbilateralrelationship,inthatthetopcontingencyrefers tothesupplier(sup)ormarketingprofessionalandthelowerone referstothedemand(dem)orconsumer.

Foxall(1999)statesthatrelationshipsofeconomicexchange are necessaryandsufficientinthemselvestoensurethat mar-keting activities exist within a company. Thus, in the lower sectionofFig.1,consumerbehavior(e.g.purchaseresponse)is precededbyacontextformedbydiscriminantstimuli–SDdem (e.g.availabilityofproductorserviceforaprice)andincludes consequences(e.g.utilityoftheproductorserviceacquired – utilitarian), whichcanbe reinforcers (SRdem)or punishments (SPdem).Theformerincreasesthepossibilityofthesame con-sumerpurchaseresponseonfutureoccasionswhenforexample the product ends or the services terminate, while the latter reducesthesechances.VellaandFoxall(2011)alsosuggestthat theconsumerreinforcerscanbeutilitarianandinformational,in thattheformerismediatedbytheuseoftheproductorservice itself,suchascomfortandconvenience(Foxall,2010)whilethe latterconsistsofsocialreinforcers,suchasluxury(Yeoman& Mcmahon-Beattie,2006),sophistication(Liu,2010), exclusiv-ity(Brun&Castelli,2013),amongothers.

productsorservices,etc.).Whentheofferordothis,reinforcers –SRof(profit)orpunishment–SPof(forexample,financialloss) consequencesaregeneratedforhim.

Theconsumer’spayment response, inthe aggregate, func-tions as a discriminant stimulus for the offeror, generating revenue for the company (SDof). This discriminant stimulus servesas thesituation for thesupplier’s subsequentbehavior, enablinghimtoberemuneratedand/orextract profitfromhis business.The situation or contexthasmultipledimensions, a temporaldimension being oneof these. Thereare periods of theyearwhenagreaternumberofconsumersbuyproductsand

periodswhenfewerconsumersbuy them.If higherpayments

aremadeduringeachcycle,thecompanywouldgrowin

com-mercialterms,andmonetaryexchangewouldthereforebethe sourceofacompany’sfinancialgrowth.

Inturn,therearealsoperiodswhenacompanywillattract consumerswhoseekdifferentreinforcers(e.g.exclusivity), cre-atingasituationwheretheofferorworkstoprovideconsumers withnewanddistinctoffers(Evans,2003;Smith,1956).If prop-erlydone,thiswillproduceincomeandapositivereinforcerin theformofprofits(orpunishmentasloss)forthesupplieratthe endofhisbehavioralchain.Thisprofit(orloss)canfeedback intothesystem.

Thesupplierresponsecangenerateprofitsfortheofferorand cancreateasituation for futureconsumer purchases depend-ingonhowwellhecarriesouthismarketingactivities.Thatis tosay,thisdependsonhowsuccessfullyheoffershisproducts orservices,whichcangeneratereinforcesthatareincreasingly

adapted to suit each demand, as well as pricing each

prod-uctandmakingitpossibletoincreasesales.VellaandFoxall (2013)characterizetheseasreinforcementandpunishment con-trol(SRdemandSPdem,respectively)andconsumersituation(or scenario)control(SDdem).Thus,theeffectivenessofamarketing professional’sperformance,orthatofasupplierasawhole,can bemeasuredbythewayhegeneratesreinforcersandreduces

companypunishmentsand, atthe sametime, generates more

attractivesituations,allocatesreinforcersandreducesthe pun-ishmentprocessfortheconsumer.

Thismakes the workof the offeror (commercial

adminis-tratorormarketingprofessional)extremelytechnical,withthe capabilityofbeingeffectiveorotherwise.Eachtaskperformed (operantsupplierresponses)withtheseaimshasfunctional fea-tures(Catania, 1973), butwhichvary as regardstopography: frequencyof emission(how oftenisthe samefunctionaltask undertaken),forceormagnitude(degreeofeffort,orhowmuch techniqueortechnologyisneededtoperformafunctionaltask), duration(thetimeittakestoperformanoperationaltask)and periodof latency(thetimeittakestoissuethefirstfunctional response).Dependingon howeffectivelythesecharacteristics areemployed,theresultoftheworkservesasasourceforthe demandcontext(SDdem)and,ifthisleadstoanincreaseinthe numberofconsumersandtheirshoppingrates(demandresponse frequencyormagnitude),revenueswillincrease(SDof).

The variety of products/services that a company offers is directlyassociatedwiththeirconsumeracceptance(Elmaraghy &Elmaraghy,2014).Thisacceptanceisreflectedinshopping rates. Companies offering the greatest variety of products/

servicesmeetthedemandforawidevarietyoffeaturesatthe sametimeandtherebytendtoincreasetheirrevenue(SDof).This occursbecauseoftheavailability(Responseof)ofdifferentiated sophisticated products/servicesofferedby abusiness (magni-tudeofaresponsethatgeneratesahighlevelofreinforcement

tomeetdemand) aimedatcreatingtemporary monopoliesby

providingcustomerswithexclusiveorsingularproducts(atype of SRdem) (Brun & Castelli, 2013). Thiscan avoid the need to reduce prices (responseof), and, in turn, a fall in revenue

(reductionofSDof)ifthesamenumberofclientsismaintained

(aggregatedresponseDem),whenlocalcompetitorsreducetheir

prices(Responseof alternative)(Becerra,Santaló,&Silva,2013). Inturn,byofferingbasicservices(Responseof),offering

min-imum quality (magnitude of response that generates low or

averagereinforcementfordemand),ensuresaconstantdemand ifpricedatalowervalue(loworaverageSPdem).

Inthisway,boththedifferentiatedservicesofferedandthe basic services offeredare market strategies that can increase

revenues, by means of monetary exchanges withconsumers,

thoughtheseattractdifferentaspectsasregardsthisincreasein revenue.Thefirstchargesamuchhigherprice(ordoesnotmake asignificantpricereductionwhentherearecompetitors),while

the second aims tobecome more competitive in attracting a

higherdemandforalowerprice.Byusingbothtacticstogether, a companywill manage toincrease the intensity and variety of demand. These strategies can produce different effects on revenueand,sometimes,onecanrepresentabetteroptionthan theothersoastoincreaseit.Thesearethefocuspointsofthis researchstudy.

Inaddition,thesamecompanywithitsportfolioofservice can offermorethan onetypeof differential, while maintain-ing one basic service. This means that the typeof influence acompany makesis far from clear. Thus,thisresearch aims toexamineabasicnon-differentiatedservice(lowreinforcers for demand)andtwo typesof service differentials(consumer servicesthat offerhighdifferentialandconcurrentreinforcers forthedemand).Thiscancharacterizediscriminativestimulus (Catania, 1998)forconsumers: whenpresent,thisindicatesa reinforcerthatisdifferentfromwhenanotherstimulusispresent (whichindicatesanotherreinforcer).

Foreach daythat aproduct or service is offered,there is

anassociated programmedpunishmentfortheconsumer(e.g.

topaythe price).The marketing professionalcanincreaseor reducethisandhistaskiseffectiveifhispricingmakesit pos-sible to increase subsequent revenue. Traditionally, the price discounts(Yaoetal.,2012)makeitpossibletoreducethe con-sequencesofademandpunishment(SPdem),makingapurchase behaviormorelikelytooccur.Thus,theexactlevelofdiscount thatmakesitpossibletoincreasemorethanproportionallythe demandwithoutreducingrevenue,isessentialsothata commer-cialcyclecanoccur.Thislevelofdiscountcanbedesignedto haveanimmediateresponseoradelayedresponse(Hanssens& Dekimpe,2012).Thepresentresearchexaminedthe effective-nessanddurationofthesediscountsondifferenttypesofmarket offers,withtheaimofgeneratingmoreincome.

However,thepaymentsmadetoacompanybyawide

periods.Thisischaracterizedastemporalcommercialcontexts thatconsumersgenerateinbenefitofthesupplier(intensityof responsedemofaggregatedpurchasesovertimeandtheperiod ofgreatestnumberofvariedreinforcers(SRdemvaried)associated withresponsesdem).

Depending on these contexts, conditions are created that makeiteithereasierormoredifficulttoobtainanincreasein rev-enue(SDof).Thesearedimensionsofthemarketsegmentations – heterogeneity andconsumerintensity (Evans, 2003;Smith, 1956).Thus,characteristicsofseasonality,lowandhighseason (Nadal,Font,&Rosselló,2004)andcommercialworkingdays andweekends(Jeffrey&Barden,2000)aretemporalsituations thatcaninterfereintheeffectthatdiscounts(punishment reduc-tion)haveoneach service(Hanssens etal.,2003).Thisisan issuecoveredandisalsopresentinthisresearchstudy.

Inthelanguageofoperantbehavioraleconomics,thepurpose of thisresearchis totestthe effectofthe supplier’sresponse ingeneratingfuturecommercialcontextsover time,inaway thatisfavorabletotheofferor(greater revenue),reducingthe financialpunishmentassociatedwiththedegreeofreinforcers programmedbythesupplierforconsumers(basicand differen-tialservicediscounts)withindistincttemporaldemandcontexts. Thatistosay,thisresearchaimstotestthecommercialcycleof theModelshowninFig.1duringperiodswhenthereisa varia-tionintheintensityofdemandresponsesandtheheterogeneity ofreinforcesallocatedtotheseresponses.

ThisproposaloffersacomplementtotheServiceDominant Logic (Lusch & Vargo, 2014), by providing a general con-textualizationformatterspreviouslydescribed,andtheuseof behavioraltermstoexplainthisphenomena.Theareaof mar-ketingisoftencriticizedfornotusingtheoreticalargumentsto explainits phenomenon(Hunt,2010),eventhoughthere isa

gooddealofempirical evidencetoshowhow marketing

phe-nomenoncanbeusefultoorganizationsandconsumersalike. Keyevidence,includingtheeffectthatsalesdiscountshave onsalesandservicedemands,hasbeenwelldocumented(Line & Runyan, 2012; Yoo, Lee, & Bai, 2011). It is known that companiesthat describethemselves as service leaders imple-ment more pricing strategies and that these produce greater customerperceptionasregardsrevenue,profitandbrand aware-ness(Indounas,2015).Inaddition,thehigherthelevelofprice discounts,thegreaterperceptionacustomerhasasregards sav-ings,purchaseintentionandquality(Hu,Parsa,&Khan,2006, chap.2).

However,thesestudiesoffernoexplanationastowhythese occurand,inparticular,theireffectivenessingeneratingrevenue foracompanyasaresultoftheinteractionbetweenservicesand pricing.Enz,Canina,andLomanno(2009)areamongtheonly researcherswhotestedtheeffectsthatpricinghasontherevenue ofahospitalityservicecompany,usingactualdata,overaperiod oftime.Theyfoundthatthereisprice-revenueinelasticityinthis typeofserviceandthatthebeststrategytoincreaserevenueis tomaintainhighprices,eventhoughthesedonotleadtoahigh demand (highoccupancyrate). Theseauthorsalsofoundthat pricediscountsencourageincreasedoccupancyrates,butdonot increaserevenueandmacro-economicdatahavelittleeffecton revenue.

Inspiteofthisstudy,variousaspectsrelatedtoservice pri-cing remain open, including issuesrelated tothe moderating effects of the price-revenue relationship, longitudinal studies withactualpricesonadailybasis,theallocationofdifferential pricestrategiessothatthesamecompanycanofferconsumers different benefits, control the role that seasonality playsover shorterperiodsoftime(monthlyanddaily)andemploy objec-tivemetrictoevaluateperformance,whicharerarelyusedinthis area,etc.Byshowinghowthecommercialcycleoccursusing anoperantapproach,marketingcapabilities,whichoriginatein thetechnicalabilitiesoftheprofessionalsinvolvedinthis activ-ity,canbeexplainedandtheselimitationsovercome.Marketing professionalsdonotcarryouttheirworkinavacuumor with-outapurposeinobservance.However,thereisstillvery little theoretical knowledge available toexplainthe nature of their objectives.Thepresentstudythereforeaimstoremedythislack ofinformation.

Method

Thisexpostfactoresearchstudywasconducted1usinga lon-gitudinaldesign.Everyday,theresearcherregistereddatafrom amedium-sizecompanybelongingtothehotelsectorlocated intheCentralWestregionofBrazil.Thisfirmrepresentsover 150 collaborators,including the generalmanager anda man-agerforeachoneofitsdepartments.Secondarycompanydata wasobtainedbymeansofaregionaloperationaland commer-cial systemof sales information, prices, and accommodation

occupancy rates, among others. Once the general

manage-menthadgiventheirauthorization,thedatawasorganizedand arranged so that adailytemporal seriesof analysescould be conducted.

With regardstothe townresearched,business tourismand events occur with greater frequency than leisure activities (Lemes,2009).Thehotelchosenforthepurposeofthisresearch reflectedthistypeofdemandcharacteristicduringcommercial workingdaysforthisconsumersegment.However,inaddition tothese,therewasalsoleisuretourismattheweekends.

Datausedincludedinformationaboutthehotelsinceits inau-gurationinthattown,aswellasasamplingofthehotelservices during120 consecutivecalendardays.Thepowerof the mul-tipleregressionsamplingtest(averageeffectf2=0.15)with3 predictors(pricediscountfactors)cametoaround95.2%.That istosay,evenwithareducedsamplesize,thiswasenoughto dismisstheincidenceofaTypeIIErrorinthisresearchstudy.

The discountswerecalculatedinpercentagesbasedonthe price paidfor eachroomdivided by thepricesshownon the listofdailyrates.Thiswassubtractedbyoneandmultipliedby onehundred.Sincethe priceofthe roomsvaried,aPrincipal ComponentsAnalysiswasconductedsoastoshowthefactors involved,ascanbeseeninTable1.Thisshowsthatthedifferent discounts implemented bythe hotel chainare based onthree factors.

1This research study has received financial support from the Brazilian

Table1

Factorloadingsforpricediscountfactors.

Discountonnon-differentiated services(standardizedinrelation tootherhotels)

Discountonsophisticated differentiatedservices (presidentialsuites)

Discountondifferentiated servicesthatare environmentallyfriendly

Crombach’salpha 0.76 0.63 0.84

Discountonasuperiorsuite 0.91 Discountonastandarddoubleroom 0.90 Discountonadeluxeroom 0.80 Discountonastandardsingleroom 0.57

Discountonapresidentialsuite-cer 0.78 Discountonapresidentialsuite-pan 0.68 Discountonapresidentialsuite-mat 0.66 Discountonapresidentialsuite-exe 0.55 Discountonapresidentialsuite-ama 0.36

Discountonadoublegreensuite 0.88

Discountonadeluxegreensuite 0.82

Discountonadeluxegreensuite 0.72

Discountonananti-allergicgreensuite 0.71

Discountonasinglegreensuite 0.68

KMO=0.73

Totalvarianceexplained=58%

Source:Preparedbytheauthorofthisarticle.

These discounts take into account the levels of

accom-modation differentials. The “Discount on non-differentiated services”,withα=0.76,average=22.6%andstandard

devia-tion=8.2%,consistsofroomsthataresimilartothoseofother hotels of the same level (standardsingle and double rooms, deluxeandmastersuites)withstandardservicesandreception. The factor “Discount on sophisticated differential services”, withα=0.63,average=19.5%andstandarddeviation=22.7%,

consistsofcustomizedpresidentialaccommodationwith

recep-tion and exclusive happy hour services available, as well

as tea-service, bath robes and slippers, and may include

aJacuzzi.

The third and final factor “Discounts for differentiated

services that are environmentally friendly, with α=0.84,

average=8.8%andstandarddeviation=10.5%,consistsof dis-countsfor hotelrooms thatvalue well-beingandharmonyas partoftheaccommodationtheyoffertheirguests,with100%of theirfloorsestablishedasno-smokingareas,withfragrant atmo-spheresandincluding special amenities,such as anti-allergic roomsandtheuseofecologicalmaterials.

Thus,thesethreefactorsconstitutethediscountfactors

cov-ered by this study, each one measured on the basis of an

averagepercentage.Theaveragepriceoftheservice ratesfor non-differentialroomswasequivalenttoUS$207.75(standard deviation=US$62.65).Therateforaroomwithsophisticated differentialfeatureswas equivalenttoUS$1450.00(standard deviation=US$497.05), andinthe caseof aroom with dif-ferentiatedandenvironmentallyfriendlyservices,thepricewas equivalenttoUS$186.50(standarddeviation=US$53.26).

Thetotaldailyincome(revenue)wascalculatedonthebasis ofthesumtotalofthenumberoftimeseachserviceoritemwas soldmultipliedbythepricepaidbyeachoneperday.Thiswas subdivided in partial daily revenue, namely: revenue derived from non-differentiated services, revenue from sophisticated

differentiated services and revenue from differentiated envi-ronmentallyfriendlyservicesusingthesameformulausedfor thetotalrevenue,thoughrestrictedtotheseservicesalone.The hotelchain’srevenueaveragedUS$25,616.90perday,witha standarddeviationequaltoUS$16,373.40.

In this researchstudy, the sum totalof dailyrevenue was averagedoutbytheaveragemonthlyrevenue.Inthisway, val-uesequaltooneareincludedintheaveragemonthlyrevenue, above(below)onearehigher(lower)thanthemonthlyaverage monthly.Therelativedailyrevenue,adependentvariableinthis study, showed anaverage equaltoone andastandard devia-tionequalto9.6.Theoveralloccupancyratewasmeasuredby thenumberof roomsoccupieddividedbythetotalnumberof rooms availableonadailybasis,whichwasalso sub-divided intodifferenttypesofaccommodation.

AdescriptivedataanalysisisshowninTable2.Ascanbe seen,thisshowsthattherewasareasonableoveralloccupancy rate. In addition,the rooms withthe highestoccupancy rates were those without differential features, in spite of the high standarddeviations.Thegreatervariancerevenueswerethose offeringsophisticateddifferentiatedservices,whilethose offer-ingsmallerdiscountswerethosethatprovideddifferentiatedand environmentallyfriendlyservices.

Inall,thisarticlepresentsthreestatisticalanalyses.Thefirst

aims toshow theeffectof eachdiscounts onaccommodation

service provided (reducing monetary punishmentsassociated

with different degrees and types of reinforcers that the sup-plierprogramsfortheconsumer)inthecompositionofrevenues (compositionofSDof).

The second aimstoshow the effectsthat typesof season-ality(intensityof responsesdemforaggregated purchasesover timeandtheperiodofthegreatestnumberofvariedreinforcers (SRdemvaried)associated withresponsesdem)have onthe total

Table2

Descriptivedataanalysis.

Descriptivedata Average Standarddeviation Minimum Maximum

Generaloccupancyrate(%) 51.7 29.0 8.1 99.6

Occupancyrateofnon-differentialrooms(%) 50.9 28.3 0.8 100 Occupancyrateforroomswithsophisticateddifferential(%) 35.2 0.3 0.0 100 Occupancyrateofenvironmentallyfriendlyaccommodation(%) 34.9 0.3 0.0 100

Totalrevenue(relative) 1.0 0.6 0.1 2.6

Revenuefordifferentialservices(relative) 1.0 0.6 0.1 2.4 Revenueforsophisticateddifferentialservices(relative) 1.0 1.9 0.0 11.4 Revenueforenvironmentallyfriendlydiff.services(relative) 1.0 1.0 0.0 3.2

Discountsfornon-differentialservices(%) 22.5 8 0 43

Discountsforsophisticaldiff.services(%) 19.5 22.7 0 95 Discountsforenvironmentallyfriendlydiff.services(%) 8.8 10.5 0 70 Source:Preparedbytheauthorofthisarticle.

The third analysis, derived from the two previous analy-ses, was to establish the everyday effects that discounts of eachservice (reducingmonetarypunishmentsassociatedwith different levels and types of reinforcers programmed by the supplierfortheconsumer)hadontotalrevenue(SDof),in accor-dancewithseasonaldemanddimensions(intensityofpurchase responsesdemaggregatedovertimeandtheperiodofthe great-estnumberofvariedreinforcers(SRdem varied)associatedwith

responsesdem).Theanalyticalunitofeachanalysisisbasedon

dailyrevenue.

In the first analysis, an autoregressive integrated moving

average – ARIMA model was used for each composition of

revenue. Thiswas necessary as the revenue data(partial and total)were showntobe auto-correlated (Durbin–Watson var-ied between 0.8 and 1.3, the reference value being=2) and non-stationarity(theAugmentedDickey–Fullertestswere non-significantforp>0.05fortwopartialrevenues).However,itwas necessarytointegratetheARIMAmodelbythefirstdifference. The normality assumptions of the independent variables(the

Kolmogorov–Smirnov testswere non-significant for p>0.05)

andhomoscedasticityweremet (WhiteLM Testwereall

sig-nificantforp≤0.05).Themodelsthatbetteradaptedtothedata aredescribedinTable3ofthesefindings.Forrevenuederived from non-differential services (Sof from the low magnitude

responseof),thebestmodelwastheonewith=1;difference=0

numberofauto-regressiveterms.

For revenue earned from non-differentiated services (Sof derivedfromlowmagnituderesponsesof),thebestmodelwasthe onewithautoregressivetermof=1;difference=0;andamoving averagetermnumberof=0.Inthecaseofrevenuederivedfrom differentialsophisticatedservices(Sofderivedfromahigh mag-nituderesponseof),thebestmodelwastheonewithanumberof autoregressivetermof=1;difference=1;andamovingaverage term of=0. For revenuederived fromdifferentiated environ-mentallyfriendlyservices(Sofderivedfromanalternativehigh magnituderesponseof),thebestmodelwastheonewitha num-berofautoregressivetermsof=0;difference=1;andamoving averagetermof=0.

In the second analysis (Table 4), in order to demonstrate theaggregatedeffectofconsumerpurchaseresponsesinterms

of revenue, the ARIMA Model was also used (number of

autoregressiveterms=2;difference=0;amovingaverageterm of=7), the explicative variables being the seasonal dimen-sions(highseasonversuslowseasonandcommercialworking

days versusweekenddays) weredichotomizedandtreatedas

eventvariables.Anaverageofthetotalrelativizedrevenuewas

used as a dependent variable. It was seen that the monthly

seasonality (Nadaletal.,2004)measurestheperiodofhigher intensity of purchase responsedem andthe weekly seasonality

measuresthe period of thegreatest numberof varieties/types ofreinforcersavailabletoconsumers,sinceduringcommercial workingdayshotelguestsgenerallyconsistofbusinessorevent tourists and, duringweekends,of guests whohadconsidered the previous two options, as well as leisuretourists (Lemes, 2009).

In the third analysis (Fig. 3), in order to demonstrate the overall effects of the commercial cycle on revenue, the

variable seasons were used as environmental variables that

interact with discount strategies. For this, a sample

sep-aration for each season dimension combination was used

and the effects of the three service discount factors were

tested for the total revenue, by means of a Generalized

Estimating Equation. Thus, in each seasonality combination,

there is an equation with independent discount variables

[Ytssea=logB(Disc1tssea)+logB(Disc2tsea)+logB(Disc3tsea)].

A log-linear model was used, with a matrix work structure

AR(1),consideredtobethebestforthesedata(lowerQIC). Thefourcombinationsofthetwodimensionsofseasonality involvedinthisthirdanalysiswereasfollows:(1) lowseason

demandduringweekends(LSWE),whenthereisalownumber

of consumerswith highheterogeneity of reinforces available

to meet demand; (2) low seasonduring commercialworking

days (LSWD), which presents a low number of consumers

withlowheterogeneityofreinforcersavailabletomeetdemand;

(3) highseasonduringweekends(HSWE) thatpresentahigh

numbers of consumers with low heterogeneity of reinforcers

availabletomeetdemand;and(4)highseasonandcommercial

working days (HSWD) that present a high number of

Results

Theeffectofdiscountsforeachserviceonthecomposition ofrevenue

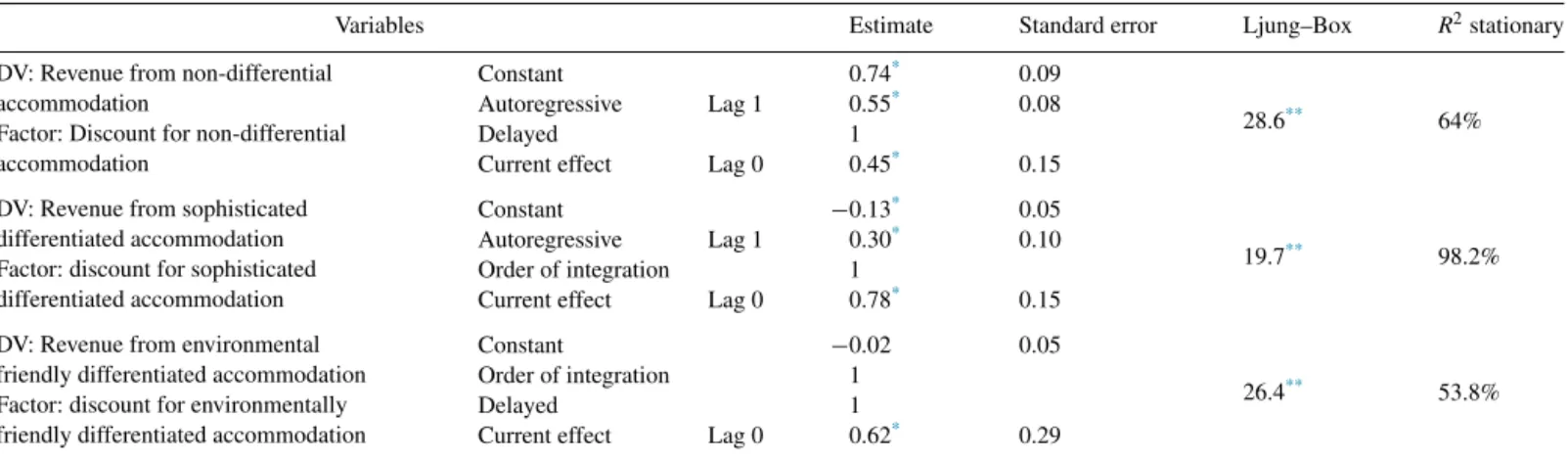

Table3showsfindingsrelatedtotheimpactcausedby reduc-ingmonetarypunishmentsassociatedwithdifferentlevelsand typeofreinforcers,whichareprogrammedbytheofferorto con-sumers,inrelationtothecompositionofthecommercialcontext (revenues)receivedbytheofferor.

Thepartialrevenuesearnedlaggedinoneday,from differ-entiatedservicesandfromsophisticateddifferentiatedservices, hada positiveeffect onthe current revenue, whichindicates an upwardtrend in their predicted value.Thus, the previous SDof increase (previous commercialcontext) tendsto gener-ateanincreaseinthesubsequentSDof(subsequentcommercial context).However,thepartial revenuesderivedfrom environ-mentallyfriendlyservicesdonotpresentthesameeffect.That istosay,thepreviouscontextinthiscasedidnotgeneratethe subsequentcontext.

All the explanatory variables (discounts for each service, whichare also known as offeror’s responses) had a positive influenceontheirrespectiverevenues,withgreater impactfor services that offered advanced differentials, environmentally

friendlydifferentialsandthosewithoutdifferentialsinrelation tootherhotels,respectively.Thatistosay,discountsonservices offering advanced differentials had afar greater impact than thosegivenforotherservices.Theeffectsofthesediscountswere temporary–lastingonlyonthedaytheywereimplemented(very short-termtemporaldiscriminationof).Thesedidnot,therefore presentlongtermeffects.

However,inthecaseofnon-differentialservicesand environ-mentallyfriendlydifferentialservices,theeffectsofadiscount occuronedaylater(shortlatencypurchaseresponsedemto

gener-atesubsequentSDof).Thisisduetothefactthatclientsonlysettle

theiraccountswhentheycheckoutofthehotel.Suchdelaysare notobservedinthecaseof differentialsophisticatedservices, sincepaymentsaremadebeforetheclientoccupiestheroom.

Duetothenon-stationarynatureofthedataforARIMA mod-elsfor differentialservices,anintegrationorderequivalentto onewasallocatedtothis.Asaresult,thenon-stationaryeffects

were corrected. The adjusted residuals of the (Ljung–Box)

models werehigher thanp>0.05,whichshowstherewas no significantautocorrelation betweenthem.The datawasbetter adjusted for services with sophisticated differentials (R2 sta-tionary=98.2%)andthe datafortheotherrelationships were reasonablywell-adjusted.Thesecanbemoreeasilyvisualized inFig.2,representedbyGraphicsA,BandC.

Table3

Effectsofeachdiscountonthe(partial)revenue.

Variables Estimate Standarderror Ljung–Box R2stationary DV:Revenuefromnon-differential

accommodation

Constant 0.74* 0.09

28.6** 64%

Autoregressive Lag1 0.55* 0.08

Factor:Discountfornon-differential accommodation

Delayed 1

Currenteffect Lag0 0.45* 0.15

DV:Revenuefromsophisticated differentiatedaccommodation

Constant −0.13* 0.05

19.7** 98.2% Autoregressive Lag1 0.30* 0.10

Factor:discountforsophisticated differentiatedaccommodation

Orderofintegration 1

Currenteffect Lag0 0.78* 0.15

DV:Revenuefromenvironmental friendlydifferentiatedaccommodation

Constant −0.02 0.05

26.4** 53.8%

Orderofintegration 1 Factor:discountforenvironmentally

friendlydifferentiatedaccommodation

Delayed 1

Currenteffect Lag0 0.62* 0.29

Source:Preparedbytheauthorofthisarticle.

* p≤0.01. ** p>0.05.

Table4

Effectsthattypesofseasonalityhaveonrevenue(total).

Variables Delay Estimate Errorstandard Ljung–Box R2stationary

DV:Total RevenueRelative

Autoregressive Lag1 1.24

* 0.03

8.00** 78.7%

Lag2 −0.99* 0.03 Movingaverage

Lag2 −0.26* 0.10 Lag3 −0.47* 0.10 Lag4 −0.70* 0.09 Lag7 −0.32* 0.10

Season Lowseason=0;Highseason=1 Lag0 1.02* 0.12

Daysoftheweek Weekends=0;Commercialworkingdays=1 Lag0 0.21* 0.08

Source:Preparedbytheauthorofthisarticle.

13

Relativ

e re

ven

ue (basic ser

vice)

Observed Prediction adjusted

Graph A

Date

Date

Date Graph B

Graph C Observed

Prediction adjusted

Observed Adjusted prediction

Relativ

e re

ven

ue (ser

vice with sophisticated

diff

erential)

Relativ

e re

ven

ue (ser

vice with

en

viron

u

mentally fr

iendly diff

erential)

12 11 10 9 8 7

5 4 3 2 1 0

1 6 11 16 21 26 31 36 41 46 51 56 61 66 71 76 81 86 91 96101106111116

1 6 11 16 21 26 31 36 41 46 51 56 61 66 71 76 81 86 91 96101106111116

1 6 11 16 21 26 31 36 41 46 51 56 61 66 71 76 81 86 91 96101106111116 6

13 12 11 10 9 8 7

5 4 3 2 1 0 6

13 12 11 10 9 8 7

5 4 3 2 1 0 6

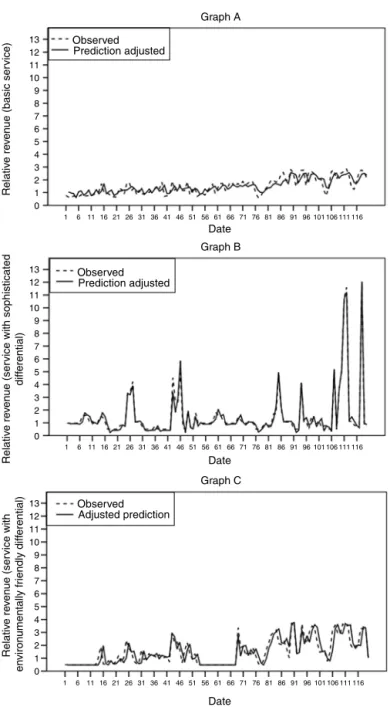

Fig.2.Adjustmentforthediscountpredictionforeachservicesthatmakeup thesalesrevenue.

Source:Preparedbytheauthorofthisarticle.

GraphAshowstheadjustmentsmadeforpartialrevenuesfor non-differential servicesover time(duringconsecutivedays), basedonthepredicteddiscounts.GraphBshowstheadjustments madeforpartialrevenuesforsophisticateddifferentialservices,

while Graph Cshows theadjustments made for revenuesfor

environmentallyfriendlydifferentialservices.

Theeffectsthattypesofseasonalityexertonrevenue

Thenon-stationaritycorrectedintheARIMAmodelforthe effectsthatdiscountshaveoneachtypeofservices,showthat theseareduetotheseasonalityintherevenuedata.Thus,allthe partialrevenuedatawasaggregatedintototalrevenueand exist-ingseasonalitiestested.Table4showstheeffectsoftheintensity

of purchase responsedemover timeonrevenue(SDof)andthe effectscreatedbythegreatestnumberofvariedreinforcers avail-abletoconsumers(SRdemvaried)overtimeonrevenue(SDof).

With regards tothe hotelresearched, the lowseason (LS) occursinthemonthofJanuaryandthehighseason(HS)during therestoftheyear.Therewerehigherpeaksinroomoccupancy duringcommercialworkingdays(WD)ratherthanatweekends (WE).Thus,boththeseasonalitydimensionshadacurrenteffect (latency responsedem aggregatedtogeneratesubsequent SDof)

on revenue and, together with the lagged revenue, showed a

78.7%stationaryexplanatoryvariance.Inaddition,theseasonal effect(intensityofpurchaseresponsedemaggregatedovertime) is much stronger on revenue, almost five times greater,than duringweekdays(periodofgreaternumberofvariedreinforcers (SRdemvaried)associatedwithpurchaseresponsesdem).

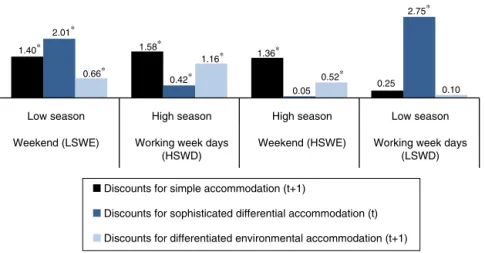

Theeffectofdiscountsofeachserviceonrevenuein differentseasonaldemands

Fig.3showstheeffectsofreducingmonetarypunishments associated withdifferentdegrees andtypesofreinforcersthat the offeror programsfor the consumer, inasubsequent com-mercial context by the offeror (revenue)in temporal context

combinations of demand. Every reduction made of the

pun-ishments programmed by the offeror for each service has a

positive impact on revenue, bearing in mind the delay of

oneday fornon-differential services andfor environmentally friendly services, as found in the first analysis. Combining

both seasonal demands, we find the dimensions of service

demand responses (average occupancy rate LSWE=20.3%,

LSWD=38.8%,HSWE=41.1%andHSWD=72.3%).

Implementingapricediscountstrategyfor non-differential servicesissimilarduringalltheseasonalperiods,beinggreater inperiodsofhighseasonandduringcommercialworkingdays (HSWD).Thus,adiscountof10%inthecostoftheseservices generatesatotalincomeofaround2.8timestheaveragerevenue ofacompany.Whilethesameproportionalincreaseindiscounts generates2.61timestheaveragerevenueobtainedatweekends duringthehighseason(HSWE).Thisstrategydoesnot signifi-cantlyaffectrevenueinthelowseasonandduringcommercial

workingdays(LSWD).

Aprice discountstrategy forsophisticated differential

ser-vices is implemented more often in the low season during

commercialworkingdays (LSWD)and,thereafter,duringthe

lowseasonattheweekends(LSWE).Thus,adiscountof10%

inthepriceoftheseservicesgeneratesatotalincomeofaround 3.31timestheaveragerevenueofacompany.Meanwhile,the sameproportionalincreaseindiscountsgenerates1.44timesthe

average revenueduringcommercialworkingdaysinthehigh

season(HSWD).Thisstrategyproducesnosignificantimpact

duringthehighseasonandatweekends(HSWE).

The implementationof aprice discount strategy for envi-ronmentallyfriendlydifferentialsisgreaterduringcommercial

working days inthe highseason (HSWD) than at any other

1.40∗ 1.58∗ 1.36∗

0.25 2.01∗

0.42∗

0.05

2.75∗

0.66∗

1.16∗

0.52∗

0.10

Low season High season

High season Low season

Working week days (HSWD)

Weekend (LSWE) Working week days (LSWD) Weekend (HSWE)

Discounts for simple accommodation (t+1)

Discounts for sophisticated differential accommodation (t)

Discounts for differentiated environmental accommodation (t+1)

Fig.3.Effectofdiscountsforeachservice(Estimates)onrevenue(total)forseasonaldemand.*p≤0.01.

Source:Preparedbytheauthorofthisarticle.

generates1.64times acompany’saveragerevenueduringthe highseasonatweekends(HSWE).Thisstrategyshowsno sig-nificanteffectsinthe lowseasonduringcommercialworking

days(LSWD).

Discussion

Thesefindingsshowthattheeffectsthatdiscountshaveon revenuedependontheservicedifferentialsinvolved,thepolicy acompanyusestochargeitscustomersandtheseasonalityof demand.Theoperanteconomic-behavioraltheoryexplainsthese findings.

Howthecommercialcycleisexplainedbythethree-term

bilateralcontingency

Onthewhole,thesefindingsshowhowacommercialcycle occursfromanoperantbehavioraleconomyviewpoint(Foxall, 1999;Vella&Foxall,2013).Thisresearchshowshowservice differentials (the offeror’s response when programming dif-ferent levels of reinforcers to consumers) generate different

impactsinthe subsequent revenueof acompany(subsequent

commercial context for an offeror derived from aggregated

purchaseresponses fromconsumers), dependingon theprice

discountsallocatedtothesepurchases(offerorsresponsewhen

programmingreducedmonetarypunishmentstoconsumers).In

generalterms,thiscreatesacommercialcycle.Thus,theeffort involvedinofferingconsumersdifferentdiscriminativestimuli thatreleasedifferentlevelsofreinforcementsandreduce mon-etary punishments, generates avariety of customer purchase chargesthat,ifaggregated,generatenewcommercial discrim-inativestimulifor theofferor. This, inturn,creates favorable situationsforthegrowthofthecompanyitselfandenablesthe offerortoprovidenewcustomerresponses.

Thus,thebehavioroftheofferorcontrolsagooddealofthe behavioralcontextsofthecompany’scustomersandtheofferor iseffectivewhenestablishingmonetarypunishmentassociated withthemagnitudeofthereinforcersreleasedthroughservices, which, in turn,return to create newcommercial contextson

thepartoftheofferor.However,theconsumersdonotdirectly controlthereleaseoftheofferor’sreinforcers(profit)or punish-ments(losses).Thisrelease dependsonthelowfinancial cost oftheofferor’sownresponsewithexistingresourcestoperform his role as the personwhocontrols andregulatesdemand. If theofferorsthemselvesareeffective,theycanappropriatethe reinforcers–profits(Vella&Foxall,2011).

ThissupportstheassumptionscontainedintheService Dom-inantLogic(Lusch&Vargo,2014).Theusebyservicemanagers ofspecializedabilitiesandknowledgeformsthebasisofa

fun-damentalunit ofexchange,whichprovidesconsumerswitha

contextandprojectsreinforcers.Theconsumersreciprocateby

payingmoremoney. So,thisinteraction betweenaconsumer

andthecompanyisexplainedthroughafunctionalrelationship ofdependencebetweenoneandtheother,sothatbothparties

can obtain mutualbenefits. The managers implementpricing

strategies andofferservicesinanattempttoencourage these mutualbenefits.

Theeffectsobtainedbyreleasingreinforcers(services)and

reducingpunishments(discounts)fortheconsumer

Consumers did not generalize the offeror’s discriminative stimuli(Catania,1998).Thatistosay,acompany’sserviceshad differentpurchasingrates(inthiscase,occupancyrates).Each reinforcer(typesofservice)programmedbytheofferor gener-atesdistinctresponsestodemand.However,theeffectsobtained byreducingmonetarypunishments(discounts)andthetimeit takestogeneratenewcommercialcontextsfortheofferor,are muchthesame(greatergeneralization).

Thisresearchshowsthatofferingclientsdiscountsonthese servicesisthebestwaytocreateahighimpactonrevenue. Dis-countsthatreducethesizeofthepunishmentconsumershave topay(Oliveira-Castro,2003;Porto&Silva,2013;Rossiter& Foxall,2008),makeiteasiertoobtainreinforcersthatare util-itarianandsociallymediatedbyotherconsumers.Atthesame time,thesecreateadiscriminativestimulus(revenue)thatrelease reinforcers – profit (Talluri & Ryzin, 2005; Vella & Foxall, 2011).

Asimilarexplanationcanbegivenfor theotherdiscounts givenonotherservices.Thisiscorroboratedbythesame posi-tiveeffectobtainedthroughdiscountsgivenonenvironmentally friendly differentialandbasicservices, whichcanbe

charac-terized as a form of consumption that promotes a sense of

well-being (Lima &Partidário, 2002),or hedonic inthe first caseandmaintenanceinthe secondcase(Foxall,2010). Ser-vices that have sustainable features identify a company that adoptsenvironmentalmanagement(Felix&Santos,2013)and whichpromotespositivefeelings.Discountsmakechoiceseasier forconsumerswhoseekreinforcersrelatedtotheirwell-being, inparticularattractingthosewhocouldstayinnon-differential hotelrooms,duetothesimilarityinprices.

Non-differentialservices,ontheotherhand,representbasic conditionsofhospitality(João,Merlo,&Morgado,2010).Inthis researchstudy,thesearepricedlowerinrelationtosophisticated services,thus,discountsrelatedtotheseserviceshave propor-tionallylessimpactonrevenue. However,discounts givenon thistypeofaccommodationcancreategreatercompetitiveness inrelationtootherhotelsofthesamesize(Abrateetal.,2012) andthereforefunctiontoattractmoreconsumerswhoseekbasic hotelservices.

Policiesinvolvedinhowclientsarerequestedtosettletheir accounts relatestoresponselatency(Catania, 1973)fromthe offerorhimself,soastocreatenewcommercialcontextsforthe company(Vella&Foxall,2011),indicatinggreatergeneralized reinforcers(Kanfer,1960)– profit.Thisresearchstudy shows thatthiseffectisdelayedbyonedayforservicesthatinvolvea lowermagnitudeofrevenuetotheofferorandhasanimmediate effectinthecaseofthoseoflargermagnitude.

In addition, the duration of the effectof adiscount – the timeittakesforanoperantresponse(Catania,1973)–on rev-enueisshort(lastingonlyonthedayofthediscount).Revenue returns tosimilarlevelswhen the pricegoes backtonormal, whichisqualifiedasabusinessasusualstrategy(Hanssens& Dekimpe,2012).Thisisbecauseatemporarydiscountstrategy createsincrementalandtemporaryrevenue.Thenon-stationarity foundinnon-differentialservices,whichwouldmeanthat rev-enuedidnotreturntothesamelevel,isduetoseasonality,which iscorrectedintheARIMAmodelbythemethodofdifference (integrationinthetimeseries).

Howseasonalityaffectsrevenue

Theseasonalityfoundisduetothedemandforhotel accom-modationservices.Studiesabouttheeffectsofseasonalityhave nothadmuchofatheoreticalbasis(Koenig-Lewis&Bischoff, 2005), but the findings of this study can help explain how

discounts for each service (differential or otherwise) have a majorandpositiveimpactonrevenuedependingonthe seasona-lityofdemand.Itwasshownthatcreatingrevenueforacompany

by means of a commercial cycle depends on an adjustment

beingmadetoaggregatedconsumerpurchaseresponses,bethis either toattract different segments (consumer heterogeneity),

or to attract more consumers from the same segment

(num-ber/consumerintensity)(Evans,2003;Smith,1956).

These combinations of seasonal demands derive from the

periodicityofaggregatedpurchases.Thesecreatecontextsthat eitherincreaseordecreasetheeffectivenessoftheresponsesto theprogrammedreinforcersandpunishmentsthattheofferors makeavailabletoconsumers.Thus,duringperiodswhenthere isalowlevelofconsumerpurchases,discountsonsophisticated differentialservices havemorepowertogenerategreater rev-enuethanduringperiodsofhighintensityofpurchasesandalso representstheonlydiscountstrategythathasasignificanteffect

ontheLSWD.

Fromaconsumer’spointofview,sincethistypeofservice involvesgreaterpunishments(higherprices)andhighutilitarian andsocialreinforcers(Foxall,2010),apricediscountgenerates an increaseinrevenueduetoan increaseinhoteloccupancy rates.Thisiswhatoccurs,especiallyduringperiodswhenthere isalowvolumeofconsumers(lowseason),aperiodthatismore beneficialtodemandthantosupply(Parker,2013).

Inthecaseofdiscountsfornon-differentialservices,theseare generatedastheresultofgreaterincomebeingobtainedwhen there is a highintensity of consumers, butwith slightly less impactthanthediscountcapacityforsophisticateddifferentials duetothefact thatthereareasmallernumberofconsumers. ThesealsohaveareasonableimpactontheLSWE.Again,from aconsumer’spointofview(Foxall,2010),sincetheseservices offerbasichospitalityreinforcersandareofferedatlowprices (lowlevelofpunishment),reducingtheseincreasesthe aggre-gatedconsumerpurchaseresponse,butnotasmuchinrelation toservicesthatoffergreaterreinforcers.Analogicallyspeaking, butfromtheviewoftheofferor(Vella&Foxall,2013),these services are designed togenerategreater revenuessince they attractahigherintensityofconsumerpurchaseswhileinvolving lesspunishmentsfortheconsumer.Reducingpriceswouldnot havesuchaneffectinincreasingrevenue,becausethesealready representlowlevelsofpunishment. However,duringthehigh season,thesewouldattractproportionallyagreaternumberof consumers,whichwouldmakethisworthwhiletotheofferor.

Andfinally,discountsforenvironmentallyfriendlyservices create lessimpactthanthe two servicesdescribed above,but createamuchgreaterpositiveimpactasregardsHSWD.These differentialsinservicesattractpeoplewhoseekhedonistic rein-forcers(Foxall,2010)orthosethatpromoteasenseofwell-being (Lima&Partidário,2002).Reducingtheirpricesdoesnotmake as muchdifference as other services,probably because there wasstillnotagreatdemandfortheseatthetimeandplacethis researchwasconducted,forconsumerswhoareawareofthese reinforcers(Peattie,2010),leadingtolowroomoccupancyrates, eventhoughthesecostless.

strongmacro-economicfactorsinthehospitalityservice com-panyrevenues.Itispossiblethatthiswasbecausetheydidnot investigateshorterseasonalperiodsortheinteractionthatexists betweenseasonalityandpricingstrategiesforeachservice,for whichthepresentstudyhasobtainedresults.

Conclusion

Thisresearchshowsthat(1)acommercialcycleforservices canbeexplainedby behavioraleconomics,inparticularby a three-termbilateralcontingency;(2)pricediscountshavea pos-itiveanddistinct impactwithregardstothecompositionof a company’srevenue;(3)theeffectsthatdiscountshaveon rev-enuearevery short-term– onlylastingas longasthe dayon whichtheyare implemented; (4) thereis adelay of one day beforeitispossibletoestablishwhateffectsdiscountshavehad ondailyrevenuefromsomeoftheservices,duetocheck-out pro-cedures(paymentsarereceivedonlyaftertheserviceshavebeen used);(5)theeffectsthatdiscounthaveonrevenuearegreater for services that are more differential thanfor those that are lessdifferential;(6)revenuedatashowsnon-stationaryeffects, whichrequirestheireliminationfromtheARIMAforecast;(7) non-stationarityisduetoseasonality,andthishastwo

dimen-sionsrelatedtodemand–thenumberof purchasesmade and

theheterogeneityofthereinforcersofthebuyers;(8) seasona-litythat representstheperiodofpurchasingintensity,exertsa muchmorepositiveeffectonrevenuethantheseason,which representstheperiodwiththegreatestorlesserheterogeneityof reinforcersofthosewhobuytheseservices;(9)theeffectsthat discountshaveonrevenuefornon-differentialservicesare simi-larduringworkingdaysatthehighseasonandduringweekends atthe lowseason;(10)theeffects ofdiscountsondifferential andsophisticated services are greater during the lowseason; and(11)the effects of discounts onenvironmentally friendly anddifferentialservicesaregreaterduringthehighseasonand

oncommercialworkingdays.

Servicemanagers,especiallythoseinvolvedintourism,can evaluateandadjusttheirpricediscountpoliciesbyestablishing ifthereisaparticulartrendintheircompany’srevenueovertime and,ifso,tocontrolthesetoascertaintherealeffectsofthese discounts.Thesearepricestrategiesthatattractdemandinthe short-termandthatneedtobeusedcontinuallyinorderto gener-ateongoingeffectsonrevenue.However,thesehaveadifferent effectonacompany’srevenuedependingontheservice differ-entialsandthe seasonalperiods of demand.Discounts create agreater impactonsophisticateddifferentialservices thanon thosewithfewdifferentials,sothatagoodstrategywouldbeto generatethemostrevenueinperiodswhendemandislow.Inthe absenceofdifferentials(basicservices),thesediscountshave lit-tleimpact,butevensoarestillpositiveandsimilartoalmostall otherperiodsoftheyear,exceptforcommercialworkingdays duringthelowseason.

Theeffectiveness of discounts canbe ascertained inorder toestablishbetter pricingstrategies andtoenhance thevalue of the companyby commercializing its products or services.

This research study can therefore help business, marketing

and/orcontrollermanagerstobetterevaluatetherightperiodsto

implementpricediscountpolicies.Usingonlythedatarelatedto aservice(hospitality)andonlyasmallamountofdatacollected during the low season represent a limitation in the case of thisresearch.However,thisstudyusedup-to-dateinformation providedbythecompanyanalyzed.Inaddition,thefindingsare generalizedforsituationswhenclientspayonthesamedayor immediatelyafterusingtheservices.In thisway,the findings couldbesimilartootherresearcheswithinthesecontexts.

Conflictsofinterest

Theauthordeclaresnoconflictsofinterest.

References

Abrate,G.,Fraquelli,G.,&Viglia, G.(2012).Dynamicpricingstrategies: EvidencefromEuropeanhotels.InternationalJournalofHospitality Man-agement,31(1),160–168.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.06.003

Angner,E.,&Loewenstein,G.(2010).Behavioraleconomics.InU.Mäki(Ed.), Handbookofthephilosophyofscience:Philosophyofeconomic(Vol.13) (pp.67–101).Amsterdam,TheNetherlands:Elsevier.

Baum,W.M.(2005).Understandingbehaviorism:Behavior,culture,and evo-lution.Oxford:BlackwellPublishing.

Becerra, M.,Santaló,J.,& Silva,R.(2013).Beingbettervs.being differ-ent: Differentiation, competition, and pricing strategies in the Spanish hotelindustry.TourismManagement,34,71–79.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.tourman.2012.03.014

Brun,A.,&Castelli,C.(2013).Thenatureofluxury:Aconsumer perspec-tive.InternationalJournalofRetail&DistributionManagement,41(11/12), 823–847.http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJRDM-01-2013-0006

Catania,A.C.(1973).Theconceptoftheoperantintheanalysisofbehavior. Behaviorism,1(2),103–116.

Catania,A.C.(1998).Learning(4thed.).EnglewoodsCliffs,NJ:PrenticeHall.

Elmaraghy,H.A.,&Elmaraghy,W.H.(2014).Variety,complexityandvalue creation.InM.F.Zaeh(Ed.),Enablingmanufacturingcompetitivenessand economicsustainability(pp.1–7).Munich,German:SpringerInternational Publishing.

Enz,C.A.,Canina,L.,&Lomanno,M.(2009).Competitivepricing deci-sionsinuncertain times.CornellHospitalityQuarterly,50(3),325–341.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1938965509338550

Evans,M.(2003).Marketsegmentation.InM.J.Baker(Ed.),Themarketing book(5thed.,Vol.13,pp.246–284).Oxford:Butterworth-Heinemann.

Felix,V.,&Santos,J.(2013).Propostadeumametodologiadeavaliac¸ãode desempenhoambientalparaosetorhoteleiro.RevistaAcadêmica Obser-vatóriodeInova¸cãodoTurismo,7(4),33–53.http://dx.doi.org/10.12660/ oit.v7n4.11411

Foxall,G.R.(1999).Themarketingfirm.JournalofEconomicPsychology,

20(2),207–234.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-4870(99)00005-7

Foxall,G.R.(2010).Invitationtoconsumerbehavioranalysis.Journalof Orga-nizationalBehaviorManagement,30(2),92–109.http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/ 01608061003756307

Foxall, G. R. (2015). Operant behavioral economics. Managerial and DecisionEconomics,http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/mde.2712.Retrievedfrom.

http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mde.2712/full

Foxall,G.R.,Oliveira-Castro,J.M.,James,V.K.,&Schrezenmaier,T.C. (2007).Thebehavioraleconomicsofbrandchoice.Basingstoke:Palgrave Macmillan.

Franceschini,A.C.T.,&Ferreira,D.C.S.(2013).Economiacomportamental: Umaintroduc¸ãoparaanalistasdocomportamento.InteramericanJournal ofPsychology,46(2),317–325.

Hanssens,D.M.,Parsons,L.J.,&Schultz,R.L.(2003).Marketresponse mod-els:Econometricandtimeseriesanalysis.Norwell,MA:KluwerAcademic Publishers.

Hu,H.,Parsa,H.G.,&Khan,M.(2006).Effectivenessofpricediscount lev-elsandformatsinserviceindustries.InV.Jauhari(Ed.),Globalcaseson hospitalityindustry(pp.17–36).NewYork:TheHaworthPress.

Hunt, S. D. (2010).Marketing theory: Foundations, controversy, strategy, resource-advantagetheory.NewYork:MESharpe.

Indounas,K.(2015).Theadoptionofstrategicpricingbyindustrialservice firms. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 30(5), 521–535.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-02-2013-0028

Jeffrey, D.,& Barden,R. (2000). Ananalysisof daily occupancy perfor-mance:Abasis foreffective hotelmarketing?International Journalof ContemporaryHospitalityManagement,12(3),179–189.http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1108/09596110010320715

João,I.S.,Morgado,R.R.,&Merlo,E.M.(2010).Análisedosatributos val-orizadospeloconsumidordehotelariadosegmentoeconômico:Umestudo exploratório.Turismo:VisãoeA¸cão,12(1),04–22.

Kanfer,F.H.(1960).Incentivevalueofgeneralizedreinforcers.Psychological Reports,7(3),531–538.

Keh,H.T.,Chu,S.,&Xu,J.(2006).Efficiency,effectivenessandproductivityof marketinginservices.EuropeanJournalofOperationalResearch,170(1), 265–276.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2004.04.050

Koenig-Lewis,N.,&Bischoff,E.E.(2005).Seasonalityresearch:Thestate oftheart.InternationalJournalofTourismResearch,7(4/5), 201–219.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jtr.531

Kohli, C., & Suri, R. (2011). The price is right? Guidelines for pri-cing to enhance profitability. Business Horizons, 54(6), 563–573.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2011.08.001

Lemes,W.D.(2009).MercadoturísticodeBrasíliaesuaprincipalvoca¸cão turística.2009.Brasília,DF,Brasil:MonografiadeEspecializac¸ão, Univer-sidadedeBrasília,CentrodeExcelênciaemTurismo.

Lima,S.,&Partidário,M.doR.(2002).Novosturistaseaprocurada sus-tentabilidade:UmnovosegmentodeMercado.Lisboa,Portugal:Gabinete deEstudoseProspectivaEconómicadoMinistériodaEconomia.

Line,N.D.,&Runyan,R.C.(2012).Hospitalitymarketingresearch:Recent trendsandfuturedirections.InternationalJournalofHospitality Manage-ment,31(2),477–488.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2011.07.006

Liu,J.Y.(2010).Aconceptualmodelofconsumersophistication.Innovative Marketing,6(3),72–77.

Lusch,R.F.,&Vargo,S.L.(2014).Theservice-dominantlogicofmarketing: Dialog,debate,anddirections.NewYork:Routledge.

Madden,G.J.(2000).Abehavioral-economicsprimer.InW.K.Bickel,&R. E.Vuchinich(Eds.),Reframinghealthbehaviorchange withbehavioral economics(pp.3–26).Mahwah,NJ:LawrenceErlbaumAssociates,Inc.

Menezes,P.D.L.de,&Silva,J.C.da.(2013).Análisedosistemaoficialde classificac¸ãodosmeiosdehospedagemdoBrasil.RevistaIberoamericana deTurismo,3(1),57–70.

Nadal,J.R.,Font,A.R.,&Rosselló,A.S.(2004).Theeconomic determi-nantsofseasonalpatterns.AnnalsofTourismResearch,31(3),697–711.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.02.001

Oliveira-Castro,J.M.(2003).Effectsofbasepriceuponsearchbehaviorof con-sumersinasupermarket:Anoperantanalysis.JournalofEconomic Psychol-ogy,24(5),637–652.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0167-4870(03)00006-0

Oliveira-Castro,J.M.,&Foxall,G.R.(2005).Análisedocomportamentodo consumidor.InJ.Abreu-Rodrigues,&M.Rodrigues-Ribeiro(Eds.),Análise docomportamento:pesquisa,teoriaeaplica¸cão(pp.283–353).Porto Ale-gre:Artmed.

Parker,G.L.(2013).Managingvariabledemandfortravel.InG.L.Parker(Ed.), Practicalrevenuemanagementinpassengertransportation(Module2)(pp. 27–46).Montreal,Canada:CanadaIncorporated.

Peattie,K.(2010).Greenconsumption:Behaviorandnorms.AnnualReview of Environment andResources, 35, 195–228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1146/ annurev-environ-032609-094328

Pindyck,R.S.,&Rubinfeld,D.L.(2009).Microeconomics(7aed.).NewYork:

PearsonPrenticeHall.

Porto,R.B.,&Silva,J.B.da.(2013).Behavioralchainingthatencourages timecontractwithcustomersfitnesscenter.BrazilianJournalofMarketing,

12(4),64–84.http://dx.doi.org/10.5585/remark.v12i4.2554

Rossiter, J. R., & Foxall, G. R. (2008). Hull–Spence behavior theory as a paradigm for consumer behavior. Marketing Theory, 8(2), 123–141.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1470593108089201

Simon,H.A.(1972).Theoriesofboundedrationality.InC.B.Mcguire,&R. Radner(Eds.),Decisionandorganization(Vol.1)(pp.161–176). Amster-dam:NorthHollandPublishingCompany.

Skinner,B.F.(1974).Aboutbehaviorism.NewYork:VintageBooks.

Smith,W.R.(1956).Productdifferentiationandmarketsegmentationas alter-nativemarketingstrategies.JournalofMarketing,21(1),3–8.

Talluri,K.T.,&Ryzin,G.J.van.(2005).Thetheoryandpracticeofrevenue management.NewYork:Springer.

Theodosiou, M.,Kehagias,J.,&Katsikea,E.(2012).Strategicorientations, marketing capabilitiesandfirmperformance:Anempiricalinvestigation in the context of frontline managers in service organizations. Indus-trialMarketingManagement,41(7),1058–1070.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/ j.ejor.2004.04.050

Vella,K.J.,&Foxall,G.R.(2011).Themarketingfirm:Economicpsychology ofcorporatebehaviour.Northampton,MA:EdwardElgarPublishing.

Vella, K. J.,& Foxall, G. R. (2013). Themarketing firm: Operant inter-pretationof corporate behavior.Psychological Record, 63(2),375–402.

http://dx.doi.org/10.11133/j.tpr.2013.63.2.011

Veríssimo,M.,&Loureiro,S.M.C.(2013).Experiencemarketingandtheluxury travelindustry.Tourism&ManagementStudies,1(Specialissue),296–302.

Yao,S.,Mela,C.F.,Chiang,J.,&Chen,Y.(2012).Determiningconsumers’ discountrateswithfieldstudies.Journalof MarketingResearch,49(6), 822–841.http://dx.doi.org/10.1509/jmr.11.0009

Yeoman, I.,&Mcmahon-Beattie, U.(2006).Luxury marketsandpremium pricing. Journal of Revenue and Pricing Management, 4(4), 319–328.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.rpm.5170155