www.jped.com.br

REVIEW

ARTICLE

Insomnia

in

childhood

and

adolescence:

clinical

aspects,

diagnosis,

and

therapeutic

approach

夽

Magda

Lahorgue

Nunes

a,∗,

Oliviero

Bruni

baFaculdadedeMedicina,PontifíciaUniversidadeCatólicadoRioGrandedoSul(PUCRS),PortoAlegre,RS,Brazil bDepartmentofSocialDevelopmentandPsychology,UniversidadeLaSapienza,Rome,Italy

Received7May2015;accepted9June2015 Availableonline21September2015

KEYWORDS Insomnia; Sleepdisorders; Childhood; Adolescence

Abstract

Objectives: Toreviewtheclinicalcharacteristics,comorbidities,andmanagementofinsomnia inchildhoodandadolescence.

Sources: Thiswasanon-systematicliteraturereviewcarriedoutinthePubMeddatabase,from wherearticlespublishedinthelastfiveyearswereselected,usingthekeyword‘‘insomnia’’ andthe pediatric agegroup filter.Additionally, the study also includedarticles andclassic textbooksoftheliteratureonthesubject.

Datasynthesis: Duringchildhood,thereisapredominanceofbehavioralinsomniaasaformof sleep-onsetassociationdisorder(SOAD)and/orlimit-settingsleepdisorder.Adolescentinsomnia ismoreassociated withsleephygieneproblems anddelayedsleepphase. Psychiatric (anxi-ety,depression)orneurodevelopmentaldisorders(attentiondeficitdisorder,autism,epilepsy) frequentlyoccurinassociationwithorasacomorbidityofinsomnia.

Conclusions: Insomnia complaintsinchildren andadolescentsshouldbe takeninto account andappropriatelyinvestigatedby thepediatrician, consideringtheassociationwithseveral comorbidities,whichmustalsobediagnosed.Themaincausesofinsomniaandtriggeringfactors varyaccordingtoageanddevelopmentlevel. Thetherapeuticapproach mustincludesleep hygieneandbehavioraltechniquesand,inindividualcases,pharmacologicaltreatment. ©2015SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrightsreserved.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE Insônia;

Distúrbiosdosono; Infância;

Adolescência

Insônianainfânciaeadolescência:aspectosclínicos,diagnósticoeabordagem

terapêutica

Resumo

Objetivos: Revisarascaracterísticasclinicas,ascomorbidadeseomanejodainsônianainfância eadolescência.

夽

Pleasecitethisarticleas:NunesML,BruniO. Insomniainchildhood andadolescence: clinicalaspects, diagnosis,andtherapeutic approach.JPediatr(RioJ).2015;91:S26---35.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:nunes@pucrs.br(M.L.Nunes). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jped.2015.08.006

Fontedosdados: RevisãonãosistemáticadaliteraturarealizadanabasedadosPubMed,onde foramselecionadosartigospublicadosnosúltimos5anos,selecionadoscomousodapalavra chaveinsôniaeofiltrofaixaetáriapediátrica.Adicionalmenteforamtambémincluídosartigos elivrostextoclássicosdaliteraturasobreotema.

Síntesedosdados: Na infância existe predomínio da insônia comportamental na forma de distúrbio deinício dosonoporassociac¸ões inadequadase/ou distúrbio pelafaltade estab-elecimentodelimites.Naadolescênciaainsôniaestámaisassociadaaproblemasdehigiene dosonoeatrasodefase.Transtornospsiquiátricos(ansiedade,depressão)oudo neurodesen-volvimento(Transtornododéficitdeatenc¸ão,autismo,epilepsias)ocorremcomfrequênciaem associac¸ãooucomocomorbidadedoquadrodeinsônia.

Conclusões: A queixa de insônia nas crianc¸as e adolescentes deve ser valorizada e ade-quadamente investigadapeloPediatra, levandoem considerac¸ãoaassociac¸ão comdiversas comorbidades,quetambémdevemserdiagnosticas.Ascausasprincipaisdeinsôniaefatores desencadeantesvariamdeacordocomaidadeeníveldedesenvolvimento.Aabordagem ter-apêutica deve incluirmedidas dehigiene do sonoetécnicas comportamentais,eem casos individualizadostratamentofarmacológico.

©2015SociedadeBrasileiradePediatria.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Todososdireitos reservados.

Introduction

Sleep disorders (SD) are a frequent complaint in routine medical appointments and increasingly, the pediatrician must be able to adequately establish their diagnosis and management, thus avoiding referral to specialist consultations,aswellasunnecessaryandexcessive exami-nations/interventions.

SD mostly present as theprimary entity, but may also beassociatedwithseveralorganicdiseases(e.g.,asthma, obesity, neuromuscular diseases, gastroesophageal reflux disease,epilepsy,attentiondisorder, autismspectrum dis-order) or psychiatric comorbidities (anxiety, depression, bullying).

Clinical presentation is variable and multiple. During the first years of life, the most frequent complaints are difficultyfallingasleepand/orfrequentnocturnal awaken-ings, followed by parasomnias (confusional arousals) and sleep-disordered breathing (obstructive apnea-hypopnea syndrome).Frompreschoolageonwards,disordersrelated to inadequate sleep hygiene occur and, in adolescence, thedisordersarerelatedtocircadianissues(delayedsleep phase)orexcessivemovementduringsleep(restlessleg syn-drome[RLS]).

This review will assess a frequent SD, i.e., insom-nia, which may present in different clinical forms during childhood,withvariedmanagement.Theclinicalfeatures, diagnosis,comorbidities, andtreatmentswillbeassessed, aimingtogivethepediatriciananoverviewoftheproblem andtoprovidetoolsforitsdiagnosisandmanagement.

Sleep

characteristics

and

classification

of

SD

Recommendationsaboutsleepdurationinchildrenand ado-lescents varyaccording tothe source used. Recently, the NationalSleepFoundationpublishedaconsensusbasedon anexpertpanel,statingtheidealnumberofsleepinghours foreveryagegroupandavariabilityrangethatcontainsthe acceptablenumberofsleepinghours(Table1).1

Nocturnalawakeningsoccurfrequentlyinchildhoodand itsdistributionvarieswithage.Inthefirstsixmonthsoflife, theyareconcentratedinonetotwoeveningpeaks;afterthe sixthmonth,theyfollowadistributionthataccompaniesthe sleepcycle(whichlasts 90---120min)andoccurmore com-monlyintheREMstage.Inthesecases,itiscommonthat thechildgoesbacktosleepspontaneously.2

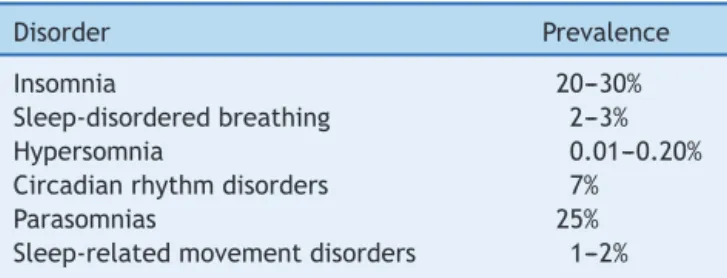

The classification of SD is proposed by the Ameri-canAcademy of SleepMedicine andthe ChronicInsomnia Definition-ICSD-3,which isthe updatedversion of ICSD-2, waspublishedin2005.Thisclassificationreviewmaintained thebasicprinciplesofthe previousone,identifyingseven majorSDcategories:insomnia,sleep-disorderedbreathing, centralhypersomnia,circadianrhythmdisorders,movement disordersduringsleep,parasomnias,andothers.2Therewas

astandardizationofdiagnosticcriteriaforadultsand chil-dren,maintainingtherecognitionofspecificage-dependent situations. Table 2 shows the prevalence of different SD inchildhood,accordingtotheAmericanAcademyofSleep Medicine.3

Insomnia

definition

Insomniacanbedefinedasdifficultyinitiatingsleep (con-sideredin children asthedifficulty tofall asleepwithout a caregiver’s intervention); maintaining sleep (frequent awakenings during the night and difficulty returning to sleepwithoutacaregiver’sintervention);orwakingup ear-lier than the usual schedule with inability to return to sleep.Insomniacancausedistressandsocial,professional, educational-academic,orbehavioralimpairment.2

Insomnia

prevalence

Table1 Sleepduration.a

Agerange Idealhoursofsleep Acceptablehoursofsleep

(maximumandminimum)

Newborns(0---3months) 14---17 18---19and11---13

Infants(4---12months) 12---15 16---18and10---11

Toddlers(1---2years) 11---14 15---16and9---10

Preschoolers(3---5years) 10---13 14and8---9

School-agedchildren(6---13years) 9---11 12and7---8

Adolescents(14---17years) 8---10 11and7

Youngadults(18---25years) 7---9 10---11and6

Adults(26---64years) 7---9 10and6

Elderly(>65years) 7---8 9and5---6

aRecommendationsoftheNationalSleepFoundationin2015,basedonanexpertpanel.

Table2 Prevalenceofsleepdisordersinchildhood accord-ingtoICSD-3.

Disorder Prevalence

Insomnia 20---30%

Sleep-disorderedbreathing 2---3%

Hypersomnia 0.01---0.20%

Circadianrhythmdisorders 7%

Parasomnias 25%

Sleep-relatedmovementdisorders 1---2%

approximately30%ofchildren.Theincreaseinprevalence, whichhasbeenobservedinrecentyears,iscloselyrelated to social habits in the family, as there is often a differ-encebetweenthechild’snaturalsleep-alertnessrhythmand socialrequirements.Thisdisorder,whenchronic,canresult indeleteriouseffectsoncognitivedevelopment,mood reg-ulation,attention,behaviorandqualityoflife,notonlyof thechildbut theentirefamily,resultinginparents’ sleep deprivation,withconsequencesfortheirworkactivities.4,5

Dataontheprevalenceofinsomniavarywithage.Inthe firsttwoyears,theratesarehigh,around30%,andafterthe thirdyearof lifetheprevalence remainsstableat around 15%.Itisworthmentioningthat,asinsomniadefinitionand diagnosisvarywidelyamongtheavailablestudies,thisfact directlyinfluencesthedataonprevalence.4,5

In a population-based study conducted in Pennsylva-nia, it was demonstrated that one out of five children or pre-adolescents have insomnia symptoms; the highest prevalence (approximately 30%) is observed in girls aged 11---12years,whichappearstobemorerelatedtohormonal changesthantoanxiety/depression.6

Anotherlargepopulation-basedstudywascarriedoutin China, using two data collection stages, with a five-year intervalbetweenthem.Anincreaseininsomniaprevalence from4.2% to6.6% and incidence from6.2% to 14.9% was demonstrated.Theinitialcaseswereassociatedwithhealth issues (laryngopharyngitis) and lifestyle (caffeine intake, smoking),whereasthenewcaseswereassociatedwith par-ents’ low educational level, alcohol intake, and mental illness.7

A population-based study conducted in Norway with adolescentsshowedthat,onweekdays,the average num-ber of sleep hours was 6h 25m, leading to a deficit of

approximately2h;mostsubjects(65%)showedlonglatency tosleeponset(>30min).Theprevalenceofinsomniainthis populationwas23.8%accordingtotheDSM-IVcriteria,18.5% usingtheDSM-V,and13.6%whenquantitativecriteriawere used.8

Types

of

insomnia

according

to

age

range

Inchildren,insomniahasclearlydefinedbehavioral charac-teristicsandcanbedefinedastwomaintypes,sleep-onset associationdisorder(SOAD)andlimit-settingSD.9

1) SOAD

In this condition, the infant learns to sleepunder a specificcondition(object,circumstance),whichusually requiresintervention/presenceofparents.Aftera noc-turnalphysiologicalawakening, he/sheneedsthesame intervention toresume sleeping. Although the number ofawakenings isnormalfor theirage group,the prob-lemoccursduetotheinabilitytoreturntosleepalone, whichprolongsthealertnessperiod.Diagnosisisbasedon thehistoryoflonglatencytosleeponset,requiring spe-cificandpre-determinedconditions,aswellastheneed for caregiver intervention during the nocturnal awak-enings. By definition, two or three awakenings/night, lastingbetween5and10minorlonger,occurfivetimes aweek.

This typeof insomniatendstodisappear at approxi-mately 3---4yearsofage. Polysomnographyis normalif the associations are present tofacilitate sleep onset. Thedifferentialdiagnosiswithothertypesofinsomniais madethroughtherapidsleeponsetinthepresenceofthe initial conditions.The therapeuticapproachis through thegradualextinctionoftheassociationstimulus.2,5

2) Limit-settingSD

Polysomnography is normal, as once the child sleeps, sleeparchitectureisadequate.Forthedifferential diag-nosis,itisimportanttoanalyzetheparents’relationship andattitudewiththechild.

Managementessentiallyinvolvesparents,whoshould establishthelimits/rulesandmaintainthemfirmly,and utilize behavioral techniques. It is acceptable to use sleep-inducingantihistamines or benzodiazepines for a limitedperiodoftime,whilebehavioraltechniquesare consolidated.2,5

Some children mayexperiencea combination of the twotypesofbehavioralinsomnia.5

Studieshaveshownthatsleepplaysacrucialroleinthe healthydevelopmentofadolescents.However,changes insleeppatternsareverycommoninadolescence,due tobiologicalandenvironmentalfactorssuchaslate bed-time, inadequate sleep hygiene, and sleep restriction andfragmentation. Insomnia inthis age group is asso-ciatedwithapoorprognosisintermsofmentalhealth, schoolperformance,andriskbehavior.2

Inadolescence,insomniamayberelatedtoinadequate sleep hygieneand delayed sleep phase, or it can have a psychophysiologicalorigin.

1) Insomniaduetoinadequatesleephygiene:

During adolescence, insomnia has characteristics relatedto changes in social habits (tendency to sleep later)andsleephygieneproblems.Thefollowinghabits areconsidered tobe inadequatesleephygiene: sleep-ingafter11pmandwakingupafter8am;irregularsleep schedule between weekdays and the weekend; use of stimulatingsubstancesordrugs(licitandillicit);excess caffeinein the late afternoon or at night;and/or use ofelectronicdevicesinthebedroombeforegoingtobed (TV,computer,mobile).Socialandfamilypressures, hor-monalchanges,andthe need for belongingtoa group alsoinfluencesleepquality.10

Insomniaduetopoorsleephygieneleadstoanincrease insleeplatencyandreductionintotalsleeptime.As a consequence,itresultsinexcessivedaytimesleepiness and/or hyperactivity, academic and relationship prob-lems,andsleep-wakecycleinversion.11,12Itisimportant

tomakethe differentialdiagnosiswithpsychiatric dis-orderssuchasdepressionandschizophrenia,notingthat insomniamaybetheinitialsymptomof these morbidi-ties.Therapeutic managementconsistsin following an adequatesleephygieneroutine,behavioraltherapyand, inselectedcases,theuseofmelatonin.5

2) Delayedsleepphaseinsomnia:

It is definedasthe delay in the sleepschedule that leads to a late awakening. This is a circadian rhythm disorder that occurs in adolescents due to hormonal changes,with a shiftin the nocturnal sleep timeas a functionoftheendogenouspacemaker.Itis acommon causeofinsomniaandcanoccuratotherages,inaddition toadolescence.

Conflictsoccur becausethebedtimedoes notmatch thesleepschedule;theadolescentrefusestogotosleep andhastroublewakingupin thefollowingmorning. It results in symptoms of sleep deprivation, hyperactiv-ity, aggression, and even learning disabilities, due to

excessivedaytimesleepiness.Aftertheymanagetofall sleep, sleep is tranquil, with adequate structure and duration(iftheydonothavetobeawakenedinthe morn-ing).Theattempttocompensateforsleepinesswithnaps duringthedayorunlimitedsleeptimeonweekendsleads tomorenocturnaldelayedsleepphase.

Optimal management consists in readjusting sleep onset time. The use of low-dose melatonin (1mg) in the late afternoon was shown to be effective in cor-recting delayed sleepphase in a double-blinded study conductedwithanadolescentpopulation.13The

associa-tionbetweendelayedsleepphaseasacauseofinsomnia inadolescentshasbeenextensivelyassessedinthe liter-ature.Inpopulation-basedstudy,carriedoutinNorway, including10,220adolescentsaged16---18years,delayed sleepphasewasobservedin3.3%ofthepopulation;over half of theseadolescents(54%girls and57%boys)also metthecriteriaforinsomnia.Additionally,thedelayed sleepphasediagnosisresultedinathree-foldincreased risk for school absenteeism in males and 1.8-fold in females.14

3) Psychophysiologicalinsomnia:

Characterized by a combination of previously expe-riencedassociationsandhypervigilance. Thecomplaint consists of an exaggerated preoccupation with sleep, gettingtosleep,andtheadverseeffectsof‘‘not sleep-ing’’onthefollowingday.Thistypeofsituationoccurs throughacombinationofriskfactors(genetic vulnerabil-ity,psychiatriccomorbidities),triggeringfactors(stress), andother factors(poorsleephygiene, caffeineintake, etc.).5

Clinical

characteristics

Among the factors that predispose toinsomnia are: birth order(moreprevalentin thefirst-bornand/oronlychild), genetic factors (positive family history); temperament (moodvariability);presenceofmaternalpsychopathologyor depression;caregivers’behaviorduringthenocturnal awak-enings (the tendency to make the child fall asleep while holdinghim/heronone’slaporpickuptheinfantinone’s armsimmediatelyafter thenocturnal awakeningtends to make insomnia a chronic condition); night feeding (noc-turnal awakenings are more common in infants who are breastfedbetween 6and 12 monthsand persistlonger in childrenwhocontinuetobebreastfedafter12months);and co-sleeping(frequentlyassociatedwithinsomnia).2

Table 3 Causes and/or triggering factors of insomnia accordingtotheagegroup.

Agerange Causes

Infants Sleep-onsetassociationdisorder (SOAD)

Foodallergies

Gastroesophagealreflux Colicininfants

Excessivenighttimefluidintake Acuteotitismediaorother infectiousdiseases Chronicdiseases

2---3years SOAD

Fear

Parentalseparationanxiety Prolongednapsoratinappropriate times

Acuteinfectiousdiseases Chronicdiseases

Preschoolersand school-aged children

Limit-settingsleepdisorder Fear

Nightmares

Acuteinfectiousdiseases Chronicdiseases

Adolescents Sleephygieneproblems Delayedsleepphase

Psychiatriccomorbidities(anxiety, depression,attentiondeficit hyperactivitydisorder) Family,schoolpressure Sleep-disorderedbreathing Movementdisorders Acuteinfectiousdiseases Chronicdiseases

Clinical

investigation

Clinicalhistoryisextremelyimportantforthediagnosisof insomnia,inwhichthefallingasleeproutine,aswellassleep andwakecharacteristicsshouldbeinvestigated.Theimpact ofsleepdisturbanceonthechild’slifeandfamilystructure shouldbeevaluated.Thephysicalexaminationalsohelpsto excludepossiblecausesofsecondaryinsomnia.2,5,16

EarlydetectionofSDisessentialfortheproper manage-menttobeestablishedandfor prognosistobefavorable. Duringthe routinepediatric consultation, a toolthat can assistin the screening is the Bedtime routines, Excessive daytimesleepiness,Awakeningsduringnight,Regularityand durationofsleep,Sleep-disorderedbreathing;(BEARS) algo-rithm,consistingoffiveeasy-to-applyquestionsthathave goodpowertodetectsleepalterations.17Table4showsthe

triggerquestionsforadequatesleepassessment.

Another option that can help assess the dimension of insomniais theuse ofsleepjournals. These allowfor the assessment of the circadian rhythm and time (amount of sleep). Some questions may be directed to assess sleep habitsandroutine.Thejournalshouldcoverthe24-hperiod,

and containinformation relatedtoa mean periodof two weeks.

Additionally, validatedquestionnaires thatassess sleep qualityarealsoquiteusefulandshouldbeusedin associa-tionwithinterviewsandthesleepjournal.

Forchildrenagedbetween0and3years,theBriefInfant SleepQuestionnaire,createdbySadehetal.andvalidated in Brazilian Portuguese should be used.18,19 For children

older than 3 years, the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Chil-dren,proposedbyBrunietal.andalsovalidatedinBrazilian Portuguese, should be used.20,21 The Brazilian Portuguese

versionofthisscaleisavailableinthedigitalversionofthis article(Appendix1).

Actigraphy is alsoa simple wayto evaluate the sleep-wake rhythm.Thisdevice is shapedlikeawristwatch and monitors body movements. The obtained signals can be analyzed throughsoftwareandcorrelatedwiththechild’s condition,andcanbeusedatanyage.22

Polysomnography (PSG) is the gold standard exam for sleep evaluation. It consists in recording the electroen-cephalogram (EEG)withother physiologicalvariables (eye movements,submentalelectromyogram,respiratory chan-nels, ECG, oxygen saturation, leg movements, position sensor, snore sensor). It allows for a complete analysis of sleeparchitecture,respiratory events,andbody move-ments. It assists in the assessment of sleeporganization, timeasleep,sleeplatency,andinthedifferentialdiagnosis betweenepilepticandnon-epilepticmotorevents.23

Comorbidities

1) Depression

Psychiatricdisordersareusuallyassociatedwithsleep problemssuchashypersomnia,fatigue,irregular sleep-wakepattern,and nightmares,amongothers.Children withmajordepressionhaveahighprevalenceof insom-nia (around 75%), and 30% have severe insomnia. The use of psychotropic medications can also negatively affectsleep.Conversely,thereisnewevidence suggest-ingthatchildhoodinsomniaitselfisariskfactorforthe developmentofpsychiatricdisordersinadolescenceand adulthood.5

A population-based study conductedwithNorwegian adolescentsshowedthatdepressionleadstosignificant sleeptimereduction,aswellaslongerlatencytosleep onsetandmoreepisodesofnocturnalawakeningsinboth genders. Adolescents with insomnia had a four tofive timeshigherriskofdepressionthanthosewhosleepwell. Sleepdeprivation(sleepingfewerthan6h/night)results inaneight-foldhigherriskofdepression.24

2) Attention-deficitdisorder/hyperactivitydisorder(ADHD) It is estimated that around 25---50% of children with ADHDhavesleepdisorders.Mianoetal.suggestdifferent patterns, including hyperarousal, latency delay, asso-ciation withrespiratory disorders,RLS, and epilepsy.25

Table4 BEARSalgorithm.a

BEARS 2---5years 6---12years 13---18years

Bedtime/sleep problems

Doesyourchildhaveany problemsgoingtobed? Fallingasleep?

Doesyourchildhaveany problemsatbedtime?Doyou haveanyproblemsgoingto bed?

Doyouhaveanyproblems fallingasleepatbedtime?

Excessivedaytime sleepiness

Doesyourchildseemoverly tiredorsleepyalotduring theday?

Doeshe/shestilltakenaps?

Doesyourchildhavedifficulty wakinginthemorning,seem sleepyduringtheday,ortake naps?Doyoufeeltiredalot?

Doyoufeelsleepyalot duringtheday?Atschool? Whiledriving?

Awakeningsduring thenight

Doesyourchildwakeupa lotatnight?

Doesyourchildseemtowake upalotatnight?Any

sleepwalkingornightmares?Do youwakeupalotatnight?Do youhavetroublegettingback tosleep?

Doyouwakeupalotat night?Havetroublegetting backtosleep?

Regularityand durationof sleep

Doesyourchildhavea regularbedtimeandwake uptime?Whatarethey?

Whattimedoesyourchildgoto bedandgetuponschooldays? Onweekends?Doyouthink he/sheisgettingenoughsleep?

Whattimedoyouusuallygo tobedonschoolnights? Weekends?Howmuchsleep doyouusuallyget? Sleep-disordered

breathing

Doesyourchildsnorealot orhavebreathing difficultiesatnight?

Doesyourchildsnorealotor haveanybreathingdifficulties atnight?

Doesyourchildsnore?

Source:ModifiedfromMindell&Owens.17

BEARS,Bedtimeroutines,Excessivedaytimesleepiness,Awakeningsduringnight,Regularityanddurationofsleep,Sleep-disordered breathing.

a Questionsintheagegroup2---5yearsareaddressedtoparents/caregivers;between 6and12years,theyareaddressedto

par-ents/caregiversandtothechildhim/herself;between13and18years,theyareaddressedtotheadolescents,whilethelast(snoring) isalsoansweredbythepartner.

agonists(clonidine),non-benzodiazepinesleep-inducers (zolpidem),ormelatonin.26

3) Autismspectrumdisorder(ASD)

ASDconsistsofneurodevelopmentaldisturbances (per-vasivediseases,Asperger’s)characterizedbysignificant socialinteractionandcommunication(language) impair-ment. SDs are common in this population and have severeeffectsontheaffectedchild’sandfamily’s qual-ity of life. Sleep restriction has been associated with increased frequency of stereotypies and worse sever-ityscores.The complaintofinsomniacharacterizedby longlatencytosleeponset,resistancetosleep,reduced sleepefficiency,andnocturnal awakeningsareofgreat concern toparents. In younger children, thereis also increasedprevalenceofbehavioralinsomnia(SOADand limit-settingSD).27

4) Epilepsy

Patientswithepilepsyhaveseveralchangesinmacro andmicrosleeparchitecture,suchasincreasedlatency tosleep onset,reduced sleepefficiency, reduced REM sleep, and sleep fragmentation (especially those who have nocturnal seizures or refractory epilepsy). Com-plaints of excessivedaytimesleepiness andpoor sleep qualityarealsofrequent.28---30

5) Tourettesyndrome

PatientswithTourettesyndromefrequentlyhavesleep andattentiondisorders.InsomniaisthemostfrequentSD andisusuallyassociatedwithbehavioraldisorderduring sleep.31

Therapeutic

approach

Thetreatmentofinsomniastartswithadetailedassessment ofitscausesandtriggers.Parentsshouldbeeducatedabout sleephygieneandadequatesleeproutinesbythe pediatri-cianduringroutinevisits.Someoftheserecommendations arelistedinTable5.

Strategiesforthetreatmentofprimaryinsomniainvolve sleephygieneroutines,behavioraltechniques,and/or phar-macologicaltreatment.

1) Sleephygieneroutines

Table5 Sleeproutinerecommendations.

Overallrecommendations

Placethebaby/childinthecrib/bedstillawake Encouragethepracticeofsleepingalonewithout

interventionfromparents/caregivers

Avoidmakingthechildsleepwhilebeingheld,inthe stroller,orotherplaceratherthanhis/herroom/bed Useatransitionalobjecttohelpbaby/childfallasleep Avoidbottle-feedingthebaby/childtosleep

Haveregularhoursfordaytimeandnighttimeactivities Establishconsistentsleeppreparationroutinesthatexclude

activitieswiththepotentialtoexcitethechild Differentiatedaytimefromnighttimeactivities

Establishbedtimeandwakeuptimesthatareappropriate totheagerangeandpersonalcharacteristicsofthechild andhis/herdaytimeactivities,aswellasthenighttime routineofthefamily

Teachrelaxationtechniquesthatthechildcanfollowon his/herown

Offerpositivereinforcementwithawardswhenthechild reachesgoalsofnotwakingupatnight

Donotencourageinappropriatebehaviorsorthebargaining ofbedtimehours

Avoidfoods/drinkswithcaffeineatnight

appliedduringthedaytopreventnegativeassociations withtheplaceofsleep.26

Positiveroutinescanalsohelpthechildlearn appro-priate sleep behaviors and reduce stress. In addition todefiningbedtime,consistentroutines(activitiesthat help prepare for sleep) should be established and repeatedeverynight.Asanexample,letthechildknow thatisalmosttimetogotobed,brushtheteeth,perform otherhygieneroutines,putonpajamas,readastoryor spendsometimewiththeparents,turnoffthelights.Itis importanttomakesurethatthetimesetforthese rout-inesissufficient,sothattheycanbeconductedcalmly, withoutharming(reducing)totalsleeptime.26

In brief,adequate sleep hygieneconsistsof (1) reg-ular/consistentbedtimethatisappropriatefortheage group;(2)avoidinghighcaffeineconsumption;(3) wel-comingnocturnalatmosphere;(4)bedtimeroutines;and 5) consistent and regular wake-up time, regardless of what occurred during the night (to maintain internal clocksynchronization).17

2) Behavioraltherapy

The main objectiveof thebehavioral approachis to eliminate thenegativeassociationsthatleadto insom-nia. Itispossibletostartthistypeoftherapyaftersix months of life.Several studies have demonstratedthe effectivenessofthisapproachinmostcases,withclear benefitstothechild’sdaytimeroutine,aswellastothat ofthefamily.32,33

There are several behavioral techniques that have beendevelopedoradaptedforthemanagementof chil-dren withbehavioral insomnia. These techniques have proven efficacy and safetyand arewidely used, espe-ciallyinAnglo-Saxoncountries.Thetechniqueshouldbe decidedbythepediatriciantogetherwiththeparents,so

thattheycandefine themostappropriateone accord-ing to the child’s age and the parents’ circumstances regardingtreatmentadherence.34

The following briefly describes the most often used techniques.2,16,17,34

Extinction:consistsinputtingthechildtosleepsafely andignoring the nocturnal behavior (crying, tantrums, calling the parents) until the following morning. This procedure canalso beperformed witha parentin the bedroom,whowillnotinteractuntilthepredetermined time.

Gradual extinction: consists in putting the child to sleepsafelyandignorethenocturnal behavior(crying, tantrums, callingtheparents) for periodsof timethat increaseduringthenight(startingwith5minand grad-ually increasingthe waiting timeby 5min each time). Thepurposeofthistechniqueistoencouragethechild tolearntoself-comfortandreturntosleepalone.

Positive routines: consists of developing a series of activities/calmroutinesthatthechildenjoystoprepare forbedtime,tryingtodisconnecttheactofgoingtobed fromastressfulroutine.Itis alsopossible toestablish rewardstobegivenonthenextdayforthosewho man-agetostayinbeduntilthenextmorningwithoutgoing totheparents’roomorcallingthem.

Planned bedtime: consists of removing the child from bed if he/she cannot fall asleep within the pre-established time interval (15---30min) and letting him/her perform some calming activity toget sleepy; theparentsshoulddelaybedtime,sothatthechildgoes tobed whenfeelingsleepy.Afterestablishingthetime whenthechildgoestosleepspontaneously,putthechild tobed15---30minearliereveryday,untiltheappropriate timeisachieved.

Programmed awakening: consists of waking up the childatnight,between15and30minbeforetheusual timeofspontaneousawakening,andafterthat, increas-ingtheintervalbetweenepisodes.

Cognitive restructuring: consists of using cognitive-behavioraltechniques,inwhichthepatientistaughtto controlhis/hernegativethoughtsabout sleepand bed-time.For instance, instead of thinking‘‘I won’tsleep tonight’’,thechildshouldthink‘‘tonightIwillrelaxand restinmybed.’’

Relaxation techniques: consists of meditation, mus-clerelaxation,takingdeepbreaths,visualizingpositive images.

Sleep restriction: consists of restricting the time in bed,sothatthechildwillonlylieinbedwhenhe/sheis almostasleep;ithelpstodisconnecttheideaofstaying in bedwithout feeling sleepyand helpstoconsolidate theconnectionbetweenbedandsleep.

Stimulus control: consists of avoiding perform-ing activities that are not sleep-inducing when the child/adolescentisalreadyinbed(TV,socialmedia, wor-ries,etc.).

Table6 Pharmacotherapyofinsomniaaccordingtothetypeofnocturnalsymptoms.

Symptom Medications

Difficultyininitiatingsleepwithoutnocturnal awakenings

Melatonin,antihistaminic

Difficultyininitiatingsleepwithmultiplenocturnal awakenings

Antihistaminic,melatonin

Multiplenocturnalawakeningsbutnodifficultyin initiatingsleep

5-Hydroxytryptophan,antihistaminic

Awakensinthemiddleofthenightwithdifficulty returningtosleep

5-Hydroxytryptophanantihistaminicinthemiddle ofthenight

Partialawakeningwithcontinuouscrying 5-Hydroxytryptophan

Awakeningwithintensemotoractivity(restlessleg syndrome)

Iron,gabapentin

Delayedsleepphaseandinsomniainadolescents Melatonin,zolpidem

Source:ModifiedfromBruni&Angriman.2

dailyfunctions(senseofwell-beingandlesscrying),but alsothemood,sleep,andparentalmaritalsatisfaction.34

Morerecentstudiessupportandconfirmthesefindings, demonstratingthat,atschoolage,childrenwith insom-nia who received behavioral intervention had better performanceatsocialskillswhencomparedtochildren whodidnotreceiveit.35Additionally,anotherstudyalso

reportedimprovementsinmaternalsleepandmood.36

Duringtheliteraturereviewforthepreparationofthis article,theauthorsdidnotretrieveanystudiesthat asso-ciated the use of behavioral interventions in children withinsomnia to deleterious effects onmental health or on the emotional connection with parents. On the contrary,severalstudiesthatconsistentlydemonstrated thebenefitsofthisinterventionwereretrieved.37,38Itis

alsoimportanttomentiontwostudiesinwhichchildren whoreceivedearlybehavioralinterventionsforinsomnia werereassessedatthefollow-upandtheauthorsdidnot detectanychangesinemotionalfunctionorinternalizing andexternalizingbehaviors.37,39

3) Pharmacologicaltherapy

Pharmacological therapy indication in childhood insomniashouldoccurwhentheparentscannotadaptto behavioraltherapiesduetoobjectivedifficultiesorwhen thetherapydoesnotshowadequateresults.The indica-tionmustbemadebeforetheproblembecomeschronic, and must be conducted in association withbehavioral therapyandforalimitedperiodoftime.Itisimportantto emphasizethattherearenodrugsforinsomniaapproved foruseinchildrenwithsuchanindication,whichalready limitsthisstrategy.2,17 Indicationsareempirical,based

moreonclinical experiencethanonevidence.Inmost children, sleep problems can be solved using a sleep hygieneapproachandbehavioral techniques; however, ifthereisdrugindication,itisrecommendedtofollow theseguidelineswhenchoosingit:

a) The medication should act on the target symptom (pain,anxiety);

b) Primary SDs (e.g., apnea, RLS) should be treated beforeinsomniamedicationisindicated;

c) Thechoiceofmedicationmustbeappropriateforthe ageandneurodevelopmentallevel,alwaysweighing thebenefitsagainstthesideeffects.

3.1)Antihistaminicagents:

Theyarethemostfrequentlyprescribeddrugsfor insom-niatherapyatthelevelofprimarycare(e.g.,hydroxyzine, diphenhydramine,promethazine).Theyassistintheacute phase,leadingtoadecreaseinlatencyandawakenings,and must be used in combination witha behavioral interven-tionprogram. Daytimesedation,dizziness, or paradoxical hyperactivitycanoccurassideeffects.40

3.2)Alpha-agonists(clonidine)

They are used for the treatment of insomnia in chil-drenduetotheirsedativeeffect.Theirdurationofaction is3---handthehalf-life is12---6h.Theyshouldbe adminis-teredatbedtime,orally.Hypotensionandweightlosshave beendescribedassideeffects.Rapidwithdrawalcanlead tounwantedsymptoms, suchasshortness of breath,high bloodpressure,andtachycardia.26

3.3)Melatonin

Itisahormone(N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) synthe-sizedbythepinealgland,whosesecretioniscontrolledby the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus, witha peakbetween2and4am.Itreduceslatencytosleeponset andnumberofawakenings,aswellasimprovingmoodand daytime behavior. Its efficacy in children with ADHD and ASDhasbeenreportedinseveralstudies.Therecommended doseis0.5---3mginchildrenand3---5mginadolescents.At theusualdoses,thesideeffects areirrelevant. The med-ication does not interfere with antiepileptic drug action, endogenous melatonin production, or pubertal develop-ment,anddoesnotcauseaddiction.41

3.4)L5-hydroxytryptophan

Itisaserotonin precursor.Ithasshowntobeeffective in episodesof certain types of parasomnia, suchas night terrors,atadoseof1---2mg/kg/dayatbedtime.Itappears tohaveasleepstabilizingfunction,beingeffectiveinsome patients.Itcanbeusedasan alternativetreatment,asit haspracticallynosideeffects.40

3.5)Iron

increaseinthenumberofawakenings.Asthishyperactivity canbeaprecursorofRLS,oralironreplacementisindicated whenferritinlevelsarelow.42

3.6)Benzodiazepines

Thesearethemostoftenprescribedpsychotropicdrugs forchildrenwithneurologicaland/orpsychiatricproblems. Theyreducethelatencytosleeponsetandimprovesleep efficiency.Side effects may occur and varyfromdaytime sedation, changes in behavior, paradoxical hyperactivity, andmemorydeficits.Theyarecontraindicatedinsuspected sleep-disorderedbreathing.41

3.7)Tricyclicantidepressants

Imipramine at a dose of 0.5mg/kg/day at bedtime appearstohave some efficacy in insomnia; however,it is notwidelyusedduetotheriskofseveresideeffects.41

3.8) Non-benzodiazepine sleep inducers (imidazopyri-dine)

Theiruseinchildrenyoungerthan12yearsis contraindi-cated.Zolpidemandzaleplonarethemostoftenused;as they have few side effects, they can be administered in children aged 12 years and older at a dose of 5---0mg at bedtime.41

Table6summarizesdrugindicationsforinsomnia accord-ingtothenocturnalcomplaint.

In conclusion, insomnia complaints in children and adolescentsshouldbetakenintoaccountandproperly inves-tigatedbythepediatrician,consideringitsassociationwith severalcomorbidities, whichmust alsobediagnosed. The maincausesof insomniaanditstriggersvaryaccording to theageandlevelofdevelopment.Thetherapeuticapproach should include sleep hygiene measures, behavioral tech-niques,and,inindividualcases,pharmacologicaltreatment.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Appendix

A.

Supplementary

data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/ j.jped.2015.08.006.

References

1.HirschkowitzM,WhitonK,AlbertSA, AlessiC,BruniO, Don-Carlos L, et al. The National SleepFoundation’s sleep time durationrecommendations:methodologyandresultssummary. SleepHealth.2015;1:40---3.

2.BruniO,AngrimanM.L’insonniainetaevolutiva.Medico Bam-bino.2015;34:224---33.

3.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classifi-cation of sleep disorders(ICSD). 3rded;2014. Available in: http://www.aasmnet.org/library/default.aspx?id=9

4.Mindell JA, Owens JA. A clinical guide to pediatric sleep-diagnosis and management of sleep problems. 2nd ed. Philadelphia:LippincottWilliams&Wilkins;2010.

5.OwensJA,MindellJA.Pediatricinsomnia.Pediatr ClinNorth Am.2011;58:555---69.

6.CalhounSL,Fernandez-MendozaJ,VgontzasAN,LiaoD,Bixler EO.Prevalenceofinsomniasymptomsinageneralpopulation

sampleofyoungchildrenandpreadolescents:gendereffects. SleepMed.2014;15:91---5.

7.ZhangJ,LamSP, LiSX,Li AM,LaiKY, WingYK.Longitudinal courseandoutcomeofchronicinsomniainHongKongChinese children:a5-yearfollow-upstudyofacommunity-basedcohort. Sleep.2011;34:1395---402.

8.HysingM,PallesenS,StormarkKM,LundervoldAJ,SivertsenB. Sleeppatternsandinsomniaamongadolescents:a population-basedstudy.JSleepRes.2013;22:549---56.

9.AmericanPsychiatricAssociation.Manualdiagnósticoe estatís-tico de transtornos mentais (DSM-5). Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2014.

10.FossumIN,NordnesLT,StoremarkSS,BjorvatnB,PallesenS.The associationbetweenuseofelectronicmediainbedbeforegoing tosleepandinsomniasymptoms,daytimesleepiness, morning-ness,andchronotype.BehavSleepMed.2014;12:343---57. 11.Merikanto I, Lahti T, Puusniekka R, Partonen T. Late

bed-timesweakenschoolperformanceandpredisposeadolescents tohealthhazards.SleepMed.2013;14:1105---11.

12.Shochat T, Cohen-Zion M, Tzischinsky O. Functional conse-quences of inadequate sleep in adolescents: a systematic review.SleepMedRev.2014;18:75---87.

13.Eckerberg B, Lowden A, Nagai R, Akerstedt T. Melatonin treatmenteffects on adolescent students’ sleep timing and sleepinessinaplacebo-controlledcrossoverstudy.Chronobiol Int.2012;29:1239---48.

14.SivertsenB, PallesenS, StormarkKM, BøeT, Lundervold AJ, HysingM.Delayedsleepphasesyndromeinadolescents: preva-lenceand correlates ina largepopulation basedstudy.BMC PublicHealth.2013;13:1163.

15.Sheldon SH, Spire JP, Levy HB. Pediatric sleep medicine. Philadelphia:WBSauders;1992.

16.NunesML,CavalcanteV.Avaliac¸ãoclínicaemanejodainsônia empacientespediátricos.JPediatr(RioJ).2005;81:277---86. 17.MindellJA,OwensJA.Aclinicalguidetopediatricsleep:

diagno-sisandmanagementofsleepproblems.Philadelphia:Lippincott Williams&Wilkins;2003.

18.SadehA.Abriefscreeningquestionnaireforinfantsleep prob-lems:validationandfindingsforaninternetsample.Pediatrics. 2004;113:e570---7.

19.NunesML,KampffJP,SadehA.Briefquestionnaireforinfant sleepassessment:translationintoBrazilianPortuguese.Sleep Sci.2012;5:89---91.

20.Bruni O, Ottaviano S, Guidetti V, Romoli M, Innocenzi M, Cortesi F, et al. The Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC)constructionandvalidationofaninstrumentto evalu-atesleepdisturbancesinchildhoodand adolescence.JSleep Res.1996;5:251---61.

21.Ferreira VR, Carvalho LB, Ruotolo F, de Morais JF, Prado LB, Prado GF. Sleep disturbance scale for children: trans-lation, cultural adaptation, and validation. Sleep Med. 2009;10:457---63.

22.SungM,AdamsonTM,HorneRS.Validation ofactigraphyfor determiningsleepandwakeinpreterminfants.ActaPaediatr. 2009;98:52---7.

23.NunesML.Sleepandepilepsyinchildren:clinicalaspectsand polysomnography.EpilepsyRes.2010;89:121---5.

24.SivertsenB,HarveyAG,LundervoldAJ,HysingM.Sleep prob-lems and depression in adolescence: results from a large population-basedstudyofNorwegianadolescentsaged 16---18 years.EurChildAdolescPsychiatry.2014;23:681---9.

25.MianoS,ParisiP,VillaMP.Thesleepphenotypesofattention deficitdisorder,theroleofarousalduringsleepandimplications fortreatment.MedHypotheses.2012;79:147---53.

attention-deficit/hyperactivitydisorder.PediatrClinNorthAm. 2011;58:667---83.

27.ReynoldsAM,MalowBA.Sleepandautismspectrumdisorders. PediatrClinNorthAm.2011;58:685---98.

28.Nunes ML, Ferri R, Arzimanoglou A, Curzi L, Appel CC, da CostaJC.Sleeporganizationinchildrenwithpartialrefractory epilepsy.JChildNeurol.2003;18:761---4.

29.PereiraAM,BruniO,FerriR,PalminiA,NunesML.Theimpact ofepilepsyonsleeparchitectureduringchildhood. Epilepsia. 2012;53:1519---25.

30.Pereira AM, Bruni O, Ferri R, Nunes ML. Sleep instability and cognitivestatus indrug-resistant epilepsies. Sleep Med. 2012;13:536---41.

31.GhoshD,RajanPV,DasD,DattaP,RothnerAD,ErenbergG.Sleep disordersinchildrenwithTourettesyndrome.PediatrNeurol. 2014;51:31---5.

32.HalalCS,NunesML.Educationinchildren’ssleephygiene:which approachesareeffective?Asystematicreview.JPediatr(RioJ). 2014;90:449---56.

33.MindellJA,MeltzerL,CarskadonMA,ChervinRD. Developmen-talaspectsofsleephygiene:findingsfromthe2004National SleepFoundationpoll.SleepMed.2009;10:771---9.

34.MindellJA,KuhnB,LewinDS,MeltzerLJ,SadehA.Behavioral treatmentofbedtimeproblemsandnightwakeningsininfants andyoungchildren.Sleep.2006;29:1263---76.

35.Quach J,Hiscock H, Ukoumunne OC,Wake M.A brief sleep interventionimproves outcomes in the schoolentry year:a randomizedcontrolledtrial.Pediatrics.2011;128:692---701.

36.HonakerSM,MeltzerLJ.Bedtimeproblemsandnightwakings inyoungchildren:anupdateoftheevidence.PaediatrRespir Rev.2014;15:333---9.

37.Price AM, Wake M, Ukoumunne OC, Hiscock H. Outcomes at six years of age for children with infant sleep prob-lems:longitudinalcommunity-basedstudy.SleepMed.2012;13: 991---8.

38.Matthey S, Crncec R. Comparison of two strategies to improve infant sleep problems, and associated impacts on maternal experience, mood and infant emotional health: a singlecasereplicationdesignstudy.EarlyHumDev. 2012;88: 437---42.

39.HiscockH,BayerJK,HamptonA,UkoumunneOC,WakeM. Long-termmotherandchildmentalhealtheffectsofa population-basedinfantsleepintervention:cluster-randomized,controlled trial.Pediatrics.2008;122:e621---7.

40.PelayoR,YuenK.Pediatricsleeppharmacology.ChildAdolesc PsychiatrClinNAm.2012;21:861---83.

41.BruniO,Alonso-AlconadaD,BesagF,BiranV,BraamW,Cortese S, et al. Current role of melatonin in pediatric neurology: clinical recommendations. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2015;19: 122---33.