IT Governance in Public Administrations

Diogo Querido – 66973

diogoquerido@tecnico.ulisboa.pt

Advisor: Prof. Miguel Mira da Silva Co-Advisor: Prof. José Tribolet Departamento de Engenharia Informática

Instituto Superior Técnico

Abstract.

For the last few decades IT has spread and grown. IT is no longer a mi-nor factor but a must have in all companies to maintain competitiveness and enhance growth. The subject concerned with the alignment of IT with business to achieve maximum business value is called IT governance (ITG). The absence of transversal ITG is exactly one of the main problems of the Portuguese Public Administration (PPA). This absence leads to a constant increase in the IT expenses over the years. To mitigate this problem, the Portuguese government created a strategic plan (PGETIC). However, due to the lack of an implementation method (among other factors), the sav-ings are not meeting the predictions. Thence, our proposal is to apply a situational method to reduce ICT expenses in the PPA. This method contains a method base, which comprises the fragments that will compose the solution to a situation-specific problem. Our method base comprises the COBIT 5 processes. The situation we will analyze is the IT department of a ministry of the PPA. To evaluate our proposal we shall use interviews, the Moody and Shanks framework, and the Wand and Weber on-tological method.Keywords: IT governance, COBIT 5, Public administration, PGETIC, Situational Method, transversal governance, expenses reduction

1

Introduction

Half a century ago, computers and information technologies were introduced in the aca-demic environment and few people in the world could exploit them. However, that situa-tion radically changed. Nowadays, informasitua-tion technology (IT) is present in every mo-ment of our life and it’s vital in any major decision.

Beynon-Davies defined IT as “any technology used to support information gathering, processing, distribution and use. IT provides means of constructing aspects of infor-mation systems (IS), but is distinct from IS. Modern IT consists of hardware, software, data and communications technology.” [1]. Hence, one may say that IT is a key resource in nowadays information gathering tasks. He also states that “in the modern, complex organizational world, most of IS rely on hardware, software, data and communications technology to a greater or lesser degree because of the efficiency and effectiveness gains possible with the use of such technology.” [1]. Therefore, IT constitutes the base of IS, which is the base for Human Activity Systems.

through the automation of activities or processes [3]. IT can seriously improve “decision making, effectiveness, responsiveness and resource utilization” [3]. This occurs due to the expeditious access to information this technology allows.

As a result of these potential benefits, both private and public companies started us-ing IT to improve their governance and management processes. Consequently, it led to a widespread use of IT and new problems and new fields, such as IT governance, start ap-pearing.

Several attempts were made to define this subject, however each author has different opinions and that lead to different definitions [4, p. 4], [5], [6], [7, p. 8]. ISACA, through the IT Governance Institute, made an attempt, recurring to a brainstorm of definitions proposed by several knowledgeable people in the field, leaders, people in used to govern every day [8]. Notwithstanding they achieved a very complete view of the field, there were too many points of view to be possible to extract a concise and definitive defini-tion. A better job to achieve a definitive definition was made by P. Webb et al., defining IT governance as “the strategic alignment of IT with the business such that maximum business value is achieved through the development and maintenance of effective IT con-trol and accountability, performance management and risk management” [9]. While recognizing the broad reach of this subject they were able to obtain clear and synthetic definition, through the compilation of twelve other definitions. This will be the definition we will use to define the object of study.

Achieving maximum business value is something that any private company is inter-ested in. Therefore, it is in their own interest to have good IT governance. In order to reach this goal there is a set of standards and reference models, commonly classified as frameworks for IT governance (COBIT, ITIL, CMMI, ISO/IEC 27000 family etc.). Each one has its advantages, some complement each other, others overlap [10], so it raises the question: Which one to choose?

According to the literature review in Section 4.3 one could say that COBIT 4.1 was one of the best-suited ITG frameworks. However, ISACA knew COBIT was lacking ITG focus. Hence, they created the COBIT 5, which builds on the previous versions and adds a domain focused in governance processes, as well as ValIT, RiskIT, etc. [11]. Fur-ther studies corroborate our beliefs positioning COBIT 5 as one of the best frameworks for enterprise governance of IT [12].

On the other hand there are the several problems in IT management and governance in Portuguese Public Administration (PPA). According to Carracha “IT departments of small size do not have a structure capable of supporting the costs and resources re-quired to deliver quality services or even to scale to satisfy growing business needs” [13]. The Portuguese government shares his position, therefore they consider necessary to “study and implement a model that permits to manage IT in a holistic fashion, putting an end to the spraying of IT function and reinforcing its maturity...” [14].

Plans like PGETIC (Plano global estratégico de racionalização e redução de custos nas TIC) [15], or the UK Government ICT Strategy [16], try to solve some of this prob-lems, by improving ICT governance and management as well as cutting costs. However, both plans are having major difficulties to achieve these goals. As we show in our demonstration (Section 7.1), COBIT 5 can help these plans to achieve their goals, there-by enhancing the actual savings.

COBIT in the IT department of any PPA ministry. This method has the advantage of eas-ily incorporating future changes, both in the department and the framework used to se-lect the processes from.

To evaluate our proposal we will use scientific models to evaluate the correctness of our artifacts. Afterwards, we will interview the same people and present them with the processes we achieved. Then we will measure how these processes satisfy their needs and how much improvement from the base processes it represents. Finally we will sub-mit papers to scientific conferences with our findings. All these processes will provide feedback about our proposal, which will enable its improvement.

On the next section we will describe the research methodology used to conduct this research and also introduce the document’s structure.

2

Research Methodology

This research was performed using the Design Science Research Methodology (DSRM) [17]. DSRM is a system of principles, practices and procedures required to carry out a study. Seven guidelines are defined for understanding, executing, and evaluating the re-search [18]: Design as an Artifact; Problem Relevance; Design Evaluation; Research Contributions; Research Rigor; Design as a Search Process; and Communication of Re-search.

DSRM aims at surpassing research paradigms, such as the traditional descriptive re-search and interpretative rere-search [17]. To achieve this goal DSRM has its roots in engi-neering and seeks to create and evaluate “IT artifacts intended to solve identified or-ganizational problems” [17]. To overcome these organizational problems, DSRM pro-poses the creation and evaluation of artifacts that may include constructs (vocabulary and symbols), models (abstractions and representations), methods (algorithms and prac-tices) and instantiations (implemented and prototype systems). This thesis will mainly focus on models and methods. Models use constructs to represent real world situations, whereas methods provide guidance on how to solve problems.

The usage of DSRM implies the adherence to strict practices required in both the con-struction and evaluation of the designed artifacts. In Figure 1 we map the DSRM steps to our work.

Figure 1: The DSRM process (adapted from [17]).

support our proposal. Afterwards, ”Proposal” (Section 6) presents a proposal as an at-tempt to solve the previously described problem. Later, we present a ”Demonstration” (Section 7) with all the results from the execution of one step of the proposal. This is fol-lowed by ”Evaluation” (Section 8) where we analyze the material in “Demonstration” and make a scientific evaluation of the produced artifacts. Furthermore, we present how will we evaluate the remaining artifacts. Finally, “Communication” is where we present the research to relevant audiences, which will be accomplished by scientific publications and presentation of the thesis.

3

Research Problem

This section corresponds to the “Problem identification and motivation” step of DSRM, which defines the specific research problem and justifies the value of a solution.

3.1 References that support the problem

Nowadays, the low efficiency and effectiveness of ICT in the Portuguese Public Ad-ministration leads to several problems and consequently to unnecessary expenses. Ac-cording to Vasconcelos, one of the main causes is the absence of transversal ICT gov-ernance in PPA [19]. This leads to several problems [19]:

• Fragmented acquisition and management of the ICT infrastructure; • Redundant ICT solutions and systems;

• Fragmented ICT procurement;

• Redundant ICT departments with reduced dimension and quality;

• Stagnation of human IT resources in small IT departments with poorly defined processes.

Carracha also concludes in his thesis that “IT Departments of small size have major difficulties in reaching an economy of scale/knowledge” [13]. Therefore, “they do not justify their existence as autonomous entities“ [13]. These problems have obvious conse-quences, of which we highlight the followings [19]:

• The existence of 6000 datacenters with low energetic efficiency; • Only 15% of open source software;

• More than 1200 communications contracts;

The Portuguese government is aware of these facts [21]. Therefore, they decided to create a group to design and implement a global strategy of rationalization of ICT in PPA to improve its efficiency and to reduce expenses [21]. In [21] the government also states the need to create a global strategic plan of rationalization and expenses reduction in ICT on PPA. This plan was created on December 15, 2011, [15]. It was approved and made official by the government on February 7, 2012, [14]. However,the problem per-sists. Not because the plan is wrong, but because it is currently stagnated and it lacks a methodology to implement it.

Therefore, the problem we aim to solve is (further detailed in Figure 3):

• The absence of transversal ICTgovernance in the Public Administration of Portugal, focusing in the reduction of expenses.

Figure 3: Thesis problem.

Vasconcelos clarifies this absence of transversal ICT governance by stating that the different organisms in PPA have the liberty to, [20]:

• Autonomously acquire and manage their own ICT infrastructure; • Acquire their own information systems;

• Individually hire their communications services;

• Create any necessary departments for management and maintenance.

Obviously, these liberties are in the origin of the integration problems [20]. Since there is a need for integration of systems and data between the IS of the different public organisms, this fragmented governance represents a major problem. Moreover, this causes the loss of the scale effect in the acquisition, implementation and management [20]. Bigger departments with process well defined may suffer repercussions of poor process’ quality in smaller departments, due to the integration needs or reliance, thereby conditioning the growth and productivity of both.

3.2 Problem consequences and motivation

Without a solution that enables ICT to be governed and managed in a holistic manner, the PPA’s ICT problems will thus deepen and proliferate:

• The redundancy of ICT resources and systems will increase;

• The number of small and redundant ICT Departments will increase (Carracha demonstrated how harmful this could be in [13]);

• The fragmentation of the ICT infrastructure acquisition, implementation and management will increase.

Obviously, these problems lead to an increase in the ICT expenses. Nevertheless, the Portuguese government aimed to an annual 500 millions saving in ICT expenses with the PGETIC implementation [14]. If this saving is not achieved by cutting ICT expenses it will be achieved somewhere else. Usually, that means cutting wages, pensions or rais-ing taxes, none of which we like. Therefore, the existence of a solution that enables ICT to be governed and managed in a holistic manner is peremptory.

4

Related Work

In this section we present a literature review of the topics related to this thesis. We will start by explaining broader concepts, such as ITG. Then, we will present some compari-sons between ITG frameworks, culminating in the choice of one or more that suit our needs. Afterwards we will explain how will we use and benefit from the capabilities of the chosen frameworks. Moreover, we will present the strategic Plans for Public Admin-istration’s IT, making a brief introduction about them, their goals and characteristics. In addition, we will make a critical analysis of both of them. Finally, we will present a short comparison of the plans goals and structure.

4.1 IT Governance

Nowadays organizations are becoming more and more reliant on IT for success and they recognize IT as one of they main assets [23]. Therefore, the alignment between business and IT is crucial. IT governance appears as a suitable solution to this problem, as well as dealing with increasing IT changes and complexity.

As it was aforementioned, several attempts were made to define this subject [4, p. 4], [5], [6], [7, p. 8], [8]. All this literature reveals a clear lack of shared understanding of the term ITG. Thus, some authors started by comparing and compiling definitions to ex-tract a definition that would express the broad reach of this subject, comprising all its el-ements, and articulating all this in a clear and synthetic definition [9],[24]. The definition we considered more accurate, and we will use in our thesis, was made by P. Webb et al. [9]:

4.2 IT Governance vs. IT Management

A common mistake is to confuse ITG and IT management. Van Grembergen et al. make an explicit distinction between both [25] (Figure 4). “IT Management is focused on the internal effective supply of IT services and products and the management of present IT operations. IT Governance in turn is much broader, and concentrates on performing and transforming IT to meet present and future demands of the business (internal focus) and the business’ customers (external focus).” [26].

This does not undermine the importance and complexity of IT management. “…Whereas elements of IT Management and the supply of (commodity) IT services and products can be commissioned to an external provider, IT Governance is organization specific, and direction and control over IT can not be delegated to the market”.

Figure 4: IT Governance and IT Management (from [26, p. 44]).

Summarizing, ITG is much broader than IT management, but they are also comple-mentary. Hence, if a company wants to grow and succeed, it must not only manage its IT resources, but also use them throughout the company as part of the governance structure. This is the approach COBIT 5 follows and the one we will follow.

4.3 ITG Frameworks

According to [27] ITG can help in the IT related risks management, IT costs rationaliza-tion and improving management and control of IT activities. However, there are a set of standards and reference models, commonly classified as frameworks for ITG (COBIT, ITIL, CMMI, ISO/IEC 27000 family etc.). We intend to choose one to use in our pro-posal. For that purpose we performed the following literature review with comparisons of several ITG frameworks.

COBIT is presented as a framework mostly used by IT auditors but, due to the several improvements made, “the trend now is for its use in IT management and governance as a basis for process ownership, a reference model for good controls and as a way to in-tegrate other best practices under one “umbrella” aligned to business needs.”[27]

After all this analysis we concluded COBIT was very likely the framework that would best suit our needs. Nevertheless, all this studies were made with COBIT 4.1 and ISACA released recently COBIT 5. Therefore, we needed to evaluate this upgrade. There is not much analysis of COBIT 5 due its recent publication. According to ISACA, COBIT 5 builds on the previous versions and adds a domain focused in governance processes, as well as ValIT, RiskIT, etc. [11], Figure 5.

De Haes et al. positions COBIT 5 as a complete and overarching IT governance and management framework that benefits from many years of experience and alignment with other frameworks and standards [12]. He highlights several important developments from COBIT 4.1, such as, the introduction of a governance domain, thereby, enhancing the governance capabilities of this framework [12], Figure 17 – Appendix E.

Figure 5: Evolution of COBIT (adapted from [30]).

4.3.1 COBIT 5

COBIT 5 is a framework that “enables IT to be governed and managed in a holistic manner for the entire enterprise, taking in the full end-to-end business and IT functional areas of responsibility, considering the IT-related interests of internal and external stakeholders.”[31]

To achieve these goals COBIT 5 provides a comprehensive framework that assists en-terprises to reach their goals and deliver value through effective governance and man-agement of enterprise IT [31]. Thus, it helps enterprises to create optimal value from IT by maintaining a balance between realizing benefits and optimizing risk levels and re-source use.

Two key areas, comprising five domains, compose the framework provided, Figure 6. These five domains comprise thirty-seven processes, Figure 20 – Appendix E. Describ-ing COBIT 5 in one sentence: COBIT 5 brings togetherthe five principles (Figure 19)

Figure 6: COBIT 5 key areas (Governance and Management) and its domains (the three blocks in the Governance area constitute a single domain) (from [31]).

4.3.2 COBIT 5 critical analysis

As can be seen in Figure 20 – Appendix E COBIT 5 is a very comprehensive frame-work for IT management and governance. For each process it specifies goals, metrics, practices, roles, inputs and outputs of each practice and the activities comprised by each practice [32]. Considering all this is evident how complex and exhaustive this frame-work is.

Notwithstanding the importance of all processes, the money and time to implement all this is limited. If we consider the PPA, the objectives of PGETIC and the current eco-nomic situation of Portugal, it is safe to say that the budget for a PPA restructuring will be very limited. Therefore, it is not feasible to implement the full COBIT 5 framework. Our proposal emerges as a need of restriction to the current situation.

4.4 Strategic Plans for Public Administration’s IT

As aforestated, private companies are becoming aware of the importance of IT and ex-pressing more concerns in ITG and management. But this is not a unique trend of private companies. All around the world countries are creating strategic plans to improve their ITG and management [15][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40].

The above-referred plans are from different countries in different continents. They are created in different environments, proposing different solutions. However, the goals are quite similar, only differing in the priorities. All want to reduce expenses in ICT as well as developing it.

We will analyze two plans, PGETIC and the UK ICT Strategy - Strategic Implemen-tation Plan (UK ICT Plan). The first because it is from Portugal, our country, and was one attempt to find a solution to the ITC problems, which are the main focus of this the-sis. The second because the Portuguese plan was heavily based on it and it poses a dif-ferent reality for comparison.

4.4.1 UK government ICT Strategy - Strategic Implementation Plan

over the four years of its implementation [16]. To achieve the goal, the plan comprises four main areas [16]: Reducing waste and project failure, and stimulating economic growth; Creating a common ICT infrastructure; Using ICT to enable and deliver change; and Strengthening governance. Each area comprises several measures and for each measure defines high-level objectives and deliverables, metrics, milestones, ac-countability and three risks mitigation actions [16].

According to [41] the plan was set out to fulfill the following objectives:

• Make Government ICT more open to the people and organizations that use our services, and open to any provider – regardless of size;

• Reduce the size and complexity of projects, and better manage risks;

• Enable reuse of existing ICT systems and “off the shelf” components, ing duplication, over-capacity and saving money;

• Move towards a common infrastructure in Government, increasing efficiency and interoperability;

• Reduce procurement timescales and making it simpler for SMEs to compete for Government business;

• Improving the implementation of big ICT projects and programs.

4.4.2 UK ICT Plan critical analysis

This plan sets a good strategy for ICT improvement. It specifies accountability for the measures as well as metrics and milestones. However, after analyzing the Strategic Im-plementation Plan [16], we concluded that the measures are very broad, leaving a lot of room for discrepancies between implementations. The deliverables are also very broad; consequently it is hard to verify their completion.

The plan started two years ago and the last report made about its progress was one and a half years ago. The results presented in that plan are good. It shows a good com-pletion rate of milestones, as well as 159.6 million pounds saved during that period [41]. After this plan there is no official records about the progress, however, we were told that is passing really hard times due to a problem that every public administration has, elec-tions. Several elements established as the accountable for some measures changed. Once the plan clearly stated the name of the accountable, now there is no one accountable for the measures. If no one is responsible nothing will be done. Besides this problem, new people also bring new concerns and different perspectives.

4.4.3 PGETIC

This plan was created in 2011 with the main goal of delivering better public services at lower cost [15]. To achieve this goal the plan follows five lines of action: “Improving governance; Reduce costs; Using ICT to foster change and modernization; Implementa-tion of common soluImplementa-tions; Promote economic growth.” [15]. The plan was forecasted to save 500 millions euros over the five years of its implementation (2012-2016). Addition-ally, it will improve the ICT structure and its mechanisms, which will reflect in 137 mil-lion euros of annual savings (when compared to the 2011 year) [15].

4.4.4 PGETIC critical analysis

A strategic plan is not the same thing as an operational plan. According to Issa-Salwe et al. “The former should be visionary, conceptual and directional in contrast to an opera-tional plan which is likely to be shorter term, tactical, focused, implementable and meas-urable.” [42]. The government created PGETIC, a strategic plan, thereby not designed to be directly implementable; however there is no operational plan. When analyzing PGETIC, one of the things we first notice is how overlong and verbose it is. It has nearly 150 pages and the lack of clear and synthetic measures poses difficulties for anyone to analyze and implement it. Therefore a proper operational plan is peremptory [22].

The measures in PGETIC are too verbose and imprecise, thereby resembling to guide-lines, not implementable processes. Nevertheless, there are some elements that could be improved in PGETIC: one is the entity accountable for a measure – it is an organization, therefore, when some problem occurs it is very hard to have someone responsible for it; other is the lack of clear metrics to evaluate the measures and clear deliverables to en-sure the execution of meaen-sure.

4.4.5 UK ITC Plan and PGETIC comparison

Despite several similarities from PGETIC to UK ICT Plan they have a different focus and background. UK ICT Plan overall focus is on improving ICT, whereas PGETIC overall focus is on reducing costs. PGETIC aims for short-term savings with deductions in ICT investments of 3.800 millions euros between 2012 and 2016 [15]. UK ICT Plan focus on improving their ICT platforms, providing a better service through reorganiza-tion, and enhancement of the governance and management mechanisms, while reducing waste. PGETIC is more focused in cutting costs, favoring measures that result in direct savings and neglecting some that could be more beneficial for the ICT development in Portugal.

All these differences happen for several reasons. The starting point for implementa-tion of this plan is quite different. Also, Portugal is under several external pressures to reduce expenses right away. This leads to different priorities. Nevertheless, we think Portugal should learn with the UK ICT Plan. All the deductions already made in poten-tial investments are not only cutting expenses, but also cutting opportunities to invest and improve. The investments in development will lead to more sustainable savings as well as potentiating further improvements ICT and subsequent savings.

5

Theoretical Background

In this section we present the theoretical background of our proposal, the subjects that influenced and guided our proposal.

5.1 Situational Method Engineering

development method tuned to the situation of the project at hand [44]. The importance of situational methods was already recognized by Olle et al. [45].The discipline concerned with the construction of these situational methods is Situational Method Engineering.

A critical activity to the support of engineering situational methods is the provision of standardized method building blocks that are stored and retrievable from a so-called

method base [46]. Therefore, a configuration process should be set up to guide the as-sembly of these building blocks into a situational method, Figure 7.

Situational methods are made with standardized and proven building blocks, making use of a uniform terminology. This is how controlled flexibility is obtained [44]. One characteristic of controlled flexibility is harmonization. This is obtained by harmoniz-ing the buildharmoniz-ing blocks of methods, thus gettharmoniz-ing the best of both worlds: on the one hand the flexible ways to develop information systems; and on the other hand the rigid, stand-ard approaches [44]. Moreover, these methods contribute to the achievement of four im-portant qualities [44]:

• Flexibility – the method to be used in a certain project is situational, meaning that, is completely tuned to the project situation at hand, resulting in an ap-proach that is as flexible as possible;

• Experience accumulation – the full but controlled adaptability of the situa-tional method allows for the addition of project experience;

• Integration and communication – the distinction between method and sup-porting tools is not made, it is a necessary prerequisite that they should be inte-grated.

• Quality – by controlling the flexibility, it guarantees that the constructed situa-tional method meets the same quality requirements as standard methods do.

In change management as well as in method engineering, situational approaches have been proposed. In [47] Gericke and Winter propose a ‘situational change engi-neering’ framework for the healthcare sector. The first step of construction of this framework (classify change projects in the healthcare sector with regard to certain

formation attributes) is based in the work of Baumöl. In [48], she conducts an approach based on interviews with informants from different industries, case studies with hetero-geneous types of ETs (Enterprise Transformation) and the analysis of ET-related meth-ods. The approach aims at investigating which techniques were successfully applied in specific situations of ET in order to derive a (general) change project classification framework. In order to identify the specific situations, a list of influence factors was cre-ated [48].

Baumöl clusters the analyzed cases according to these influence factors into five clus-ters of ET situations. Once a situation is identified, the method provides guidance on how to deal with such an ET program [48]. In a concrete ET, the identification of the re-spective situation together with the choice of appropriate techniques constitutes a situa-tional ET support method. This situasitua-tional method is an instance of process in the Fig-ure 7.

In [49], Labusch and Winter applied the same approach used by Baumöl in [48], to the insurance sector. In that article they explored context, trigger, ET situation and core technique candidates for the insurance sector. Therefore, their work provides some im-portant information useful in the definition of situations for the application of situational methods.

Another example of situational method application can be found in [50]. Luinen-burg et al. present an approach for the development of situational web design methods by means of method association. They associate feature groups of a web application do-main with web modeling methods through an association table. Method association is a helpful technique in order to select and assembly method fragments that fit with domain situational factors.

A slightly different approach is applied by Van De Weerd et al. in [51]. Considering an evolutionary approach for the implementation of a process, instead a revolutionary, Van De Weerd et al. propose an incremental situational method [52]. According to this method, “each method increment is triggered by an increment driver that arises from a changed company situation“ [51]. By using method increments for process im-provement, companies can implement small, local changes in their processes. Thus, they are not forced to radical changes, thereby reducing risk in complex projects.

This method was already applied in a retrospective case study conducted at a large ERP vendor [51]. Besides the validation of the generic method increment types, they have found four increment drivers, which comprise all method increments occurred. Ac-cording to their experience, if these increments are properly embedded in the existing in-frastructure and communicated to the right knowledge workers, process improvements can be implemented evolutionary and successfully [51]. This is the method we will apply in our thesis.

6

Research Proposal

6.1 Solution objectives

After PGETIC’s analysis (Section 4.4 and 7.1) and after starting to understand the Por-tuguese Public Administration modus operandi, we learned several important lessons. Considering these lessons we highlight the following key points of our solution:

• Short Time frame: According to Slater in [53], long-term solutions will simply not work, especially in the public administration where everything can change every four years. Therefore, any solution must be implementable in 12-18 months [54].

• Easy Implementation: Concerning an easy implementation there are four characteristics we consider fundamental:

o Proper Scope: Both PGETIC and UK ICT Plan were too high level to be implemented. The presented measures were too vague; hence we can say they were not made to be implemented, they are guidelines. Therefore, when they tried to implement them, several obstacles were found, because it lacked a method of implementation. Consequently, notwithstanding the existence of a schedule, the great majority of measures were late.

o Clear Activities: A solution must clearly specify the required activities to fulfill the process goals. Moreover, they must have enough detail to be un-derstood both by the person responsible for them and the one that will im-plement them. Activities are simple actions. They all should start with a verb [55].

o Clear Deliverables: The activities should result at least in one deliverable [55]. Thus, is easy to verify if an activity was performed or not.

o Clear Roles: Another important remark was the lack of a specific ac-countable for the measures from PGETIC. An entity was specified, never-theless, unless someone specific is responsible for the execution of par-ticular activity, no one is. Therefore, each activity should have a specific responsible for its execution.

• Clear Communication: One big mistake is letting your solution become a “shelfware” solution [54]. It “needs to be a living thing” [54]. When a solution is long, complex and containing confusing jargon or unnecessary verbiage, such as PGETIC or UK ICT Plan, it is hard to understand them to implement some-thing concrete. Thence a possible solution should be shorter, less technical and in a format/language that anyone could easily understand (e.g. diagrams). • Adaptability: One distinctive characteristic of PPA is that after four years

6.2 Proposal overview

If we take a closer look to the problem we will see that, PGETIC did not work as ex-pected, because it was not enough. PGETIC lacks a method to implement it. Therefore, based on the problem we described and on the lack of suitable solutions, we propose to

• Reduce ICT expenses in the Public Administration in Portugal, through the application of a situational method (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Thesis method(adapted from [52]).

This situational method would have, in its method base, the COBIT 5 processes. Therefore, the final result would be based in the COBIT 5 processes. There is already a generic reference guide to implement COBIT 5 [56], however, this guide is not tailored to suite the PPA needs.

In the private companies an extraordinary investment can be made to perform the re-structuring of the company; the board will follow this process until it is finished; and the investors will support the costs of unpredicted needs until it is finished, because it is in the best interest of everyone.

Contrarily to this situation, in the PPA there is little money for any required invest-ment and few time to perform any project. Every four years everything can change, pro-jects in the meantime will be cancelled or indefinitely suspended. Therefore, a full re-structuring of the PPA is not possible. Due to that reason we propose an incremental

method of implementation.

After the investigation on already created frameworks for IT governance and man-agement (Section 4.3), we concluded that COBIT 5 was the one that best suited our in-terests. Then, after the mapping of some ICT strategic plans on public administration to COBIT 5 (Section 7.1), we concluded that it is possible to map these plans COBIT 5: COBIT 5 has a broader scope than both plans (Section 8.1.1). Moreover, COBIT 5 pro-vides a good implementation base for the measures in the plans by virtue of the exhaus-tive descriptions of each process

To achieve the goal of reduction of expenses, we propose the method presented in

change [52]. This is why we chose to apply it. One of its main strengths is its adaptabil-ity. If the situation totally changes is only required to perform a new analysis of need and extract new situational indicators. Then, the method will provide processes suited to the current needs. If some significant progress is made in the ICT governance and man-agement it is only required to include the new fragments in the method base or replace some. Then, we will have to redo the step selection of the fragments and generate new processes. This method can be divided in two parts extensively explained in the Subsec-tions6.3 and 6.4:

• The creation of a method base (right side of the grey box); • The creation of the resulting processes (left side of the grey box).

6.3 Creation of method base

This phase comprises three steps:

• First, we analyzed the existing frameworks and plans (Section 4).

• Second we selected the ones that could better solve our problem and created the Method Administration (Section 4).

• Third, we compared the selected frameworks/plans in order to understand where they overlap, where one performs better than the other and what one has that the others lack (Section 7.1). To achieve the method fragments that best suit our purposes we compare them in several ways. The mapping tables are in

Appendix C and Appendix D. The results extracted from these tables and the correspondent evaluation are in Section 7.1.

After all these steps we have a method base created, comprising: All the COBIT 5 processes, [56]; Information about the processes’ situational factors - the situational fac-tors are main problems/pain points mapped to the specific processes that can help to solve them, obtained from [31]; Information about the maturity capabilities of the frag-ments - obtained from [57]; Assembly rules - extracted from [32], by analyzing the in-puts and outin-puts of each fragment.

The method base contains standardized building blocks, easily retrievable, removed or replaced by new ones.

6.4 Creation of processes

In order to generate processes suited to a specific ministry we will need to execute three steps:

• First, we will perform an analysis of need and assess and analyze the current processes of the IT department of the ministry as well as its situational indica-tors. These situational indicators are [52]: Which process difficulties actually occur; What are the so-called causal factors of the difficulties; What are the ac-tual root causes per causal factor.

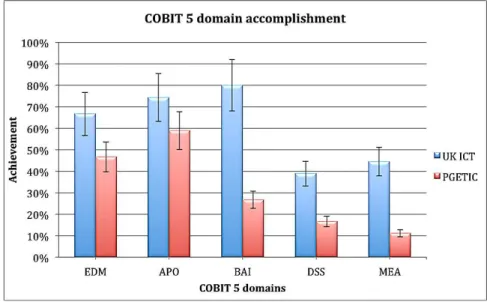

Figure 9. Moreover, in the interviews we will try to understand which are the measures from PGETIC considered more critical and imperative. Then we will use it as input to the PGETIC Goals Cascade, Figure 9.

• Second, we will select, the method fragments that will fulfill the needs of the department under study. These two cascades in Figure 9 will allow us to re-trieve the correct method fragments (COBIT 5 processes) and to derive other situational indicators. Since the method base comprises situational factors, some of the required fragments can be extracted from this mapping; others can be derived as improvements for directly correspondent processes. Then, consid-ering the assembly rules, we can elicit the fragments directly related to the al-ready selected fragments. These fragments provide key inputs, thereby required for the proper behavior of the previous ones.

• Third, we will combine the selected method fragments (the ones that can and should be combined) to deliver a set of modeled processes that can easily be implemented by the IT department. To accomplish the combination of the fragments from COBIT 5 we will guide through the COBIT 5 - Enabling Pro-cesses [32]. These proPro-cesses will be modeled using Process Deliverable Dia-grams [55]. This modeling language allows the creation of diaDia-grams comprising the activities and sub-activities of a process, the deliverables and relations of each activity.

7

Demonstration

This section describes the “Demonstration” step of DSRM. This section comprises two subsections:

• In the first one (Section 7.1), we present and analyze the work made to create the method base from the proposed method.

• In the second one (Section 7.2), we explain how will we demonstrate the results obtained from the method implementation.

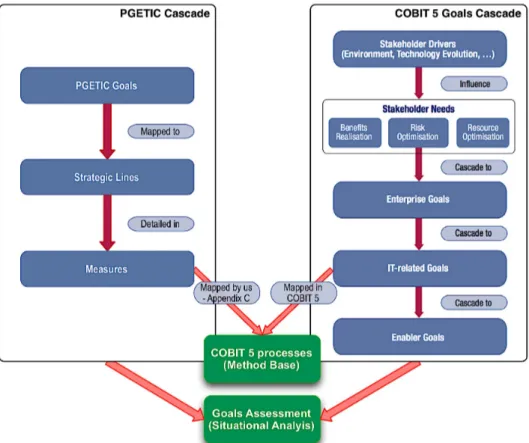

7.1 Mapping of PGETIC and UK ICT Plan to COBIT 5

This section comprises information from two mappings:

• One mapping PGETIC [15], to COBIT 5 [32] – Appendix C

• The other, mapping UK ICT Plan [16], to COBIT 5 [32] – Appendix D

These mappings encompass a mapping from all measures proposed by each one of the plans, to each process proposed by COBIT 5. In order to obtain the most accurate and impartial mapping possible, we tried to map the sub-activities, the goals of each measure to the sub-activities (in COBIT 5 they are called practices) and goals of each process. Then, to attribute a value to the process capability achieved by the implementation of this measure we used the COBIT 5 capability scale [57], Appendix B. Afterwards, we performed several analyses of the obtained data. These are described in the following subsections. The meaning of all acronyms used in the charts is explained in Appendix B, Appendix C and Appendix D.

7.1.1 Process accomplishment analysis (Figure 10 and Figure 11) In this first analysis we evaluated the processes according to four levels:

• Red – process not performed at all – 0-15% of implementation • Orange – process partially accomplished – 15-50% of implementation • Yellow – process largely accomplished – 50-85% of implementation • Green – process fully accomplished – 85-100% of implementation

Figure 10: PGETIC - level of process accomplishment.

These analyses are focused on the level of process accomplishment in case the whole plan is implemented. For a process to be fully implemented it must have all or nearly all its activities considered by the plan. The other levels are assigned considering the per-centage of activities contemplated in the plan.

Through Figures 10 and 11 we can realize that none of the plans comprise all or near-ly all COBIT 5 processes. The UK ICT Plan was the closest one, however, almost a third of COBIT 5 processes were below 50% of accomplishment. This situation is reversed in the PGETIC, with slightly more than a third of processes above 50% of accomplishment. These are clear indicators that the plans are lacking coverage. But, this is not necessarily bad. The questions are “Is this scope suiting the best interests of the ICT?” and “How much could ICT improve with solution with a broader scope?”. These questions are nearly impossible to answer or to provide a single answer. Therefore, our method aims at solving the problem from a different angle.

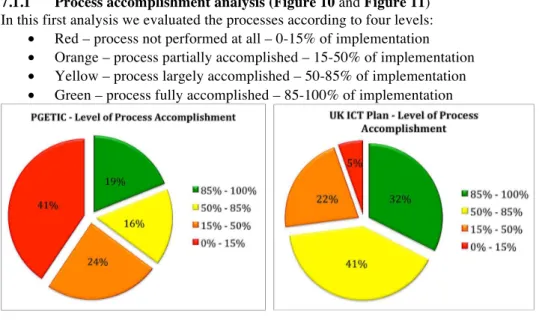

7.1.2 Domain accomplishment analysis (Figure 12)

In this analysis we made an average of the process level accomplishment by the domain where they are inserted. Because the process level accomplishment is an interval, the av-erage requires error bars. These error bars are 15% of the obtained value. This percent-age was extrapolated from the accomplishment intervals.

In Figure 12 we can clearly see what is the focus of the plans. The UK ICT Plan is more focused in the governance and in the strategic and tactical management domain. Similarly, the PGETIC is more focused in the governance and in the strategic manage-ment domain, notwithstanding the lower accomplishmanage-ment achieved in all the domains. This graph proves how these plans neglect both the operational and monitoring domain, and the tactical management in the PGETIC. Thus, these plans are definitely not directly implementable, leaving many questions to answer and problems to solve.

7.1.3 Investment/Benefit analysis (Figure 13 and Figure 14)

In this analysis we create a chart with the measures of each ICT plan. These charts are split in four quadrants according to the variables investment and return. The investment is the number of COBIT 5 processes required to fully implement one measure. The re-turn is the average COBIT 5 processes’ capability level achieved with a specific meas-ure. Then, we plotted each measure of the plan according to the number of COBIT 5 processes where, at least one practice was accomplished with this measure, and the aver-age capability level achieved by the involved processes.

Any measure with a return of two of higher is considered a big return due to the ca-pability levels explanation in Appendix B. Any measure with an investment greater or equal than five processes is considered big investment because of the number of practic-es each procpractic-ess has in average and the required inputs and outputs.

With Figures 13 and 14 we can perceive the cost/benefit of each measure of each plan. Regarding the UK ICT Plan, the majority of the measures are in the big invest-ment/big return quadrant. This was already expected because, despite the money saving policy, they are also concerned with the development of the ICT in the country. They be-lieve that one way of save money in the long term is by investing, by improving their processes and infrastructures. Contrarily, the PGETIC has the majority of the measures in the low investment/low return quadrant. Hence, it is the clear the policy followed to create this plan was focused in cutting expenses and saving money in the short term. Nevertheless, that may result in lower returns in the long term.

7.1.4 COBIT 5 processes’ capability level achieved analysis (Figure 15)

In this chart we plot all the COBIT 5 processes. Each process is plotted according to the capability level achieved by the full implementation of UK ICT Plan, against to the ca-pability level achieved by the full implementation of PGETIC.

Figure 15: COBIT 5 processes' capability level achieved analysis.

In Figure 15 the benefits of both plans are directly compared through the plotting of all COBIT 5 processes. In this chart it is clear the differences between the general COBIT 5 processes capability level allowed by the UK ICT Plan and by the PGETIC. UK ICT Plan allows the majority of processes to reach level 2 and some level 3. PGETIC only allows the majority of processes to reach level 1 and a few level 2. This demonstrates, first that our processes are in a lower level, thus our concerns are in a low-er level; second we are not as focused in achieving highlow-er levels as UK aspires.

7.2 Demonstration of the proposed method

needs. Otherwise, we would not have the proper input for our method, thereby leading to unpredictable output.

After choosing the ministry we will follow these steps: 1) Assess the business processes of the IT department; 2) Assess the as-is of the IT department;

3) Assess the specific needs to reduce expenses;

4) Define which are the measures from PGETIC the IT department is more con-cerned with in order to cut costs;

5) Select the appropriate method fragments from our method base, using the pre-vious information;

6) Select the method fragments required for the correct functioning of the previ-ously selected ones, based in the rules in the method base;

7) Generate a set of, already modeled, processes this ministry should implement.

After all these steps we will have a set of processes that will provide good practices to help the department in achieving the assessed needs. These processes are modeled in a universal language, diagrams. These diagrams follow a standard developed by Syed and Syed in [55]. Therefore, they can be validated according to the evaluation methods de-fined in the Section 8. To ease the understanding of these diagrams we will include a very brief description of the elements present in it.

8

Evaluation

This section is the ”Evaluation” step of the DSRM process, where we will evaluate our proposal. To evaluate our proposal we will have two main steps:

• An ex ante evaluation – “the artifact is evaluated on the basis of its design spec-ifications alone.” [58]. This evaluation is performed through the use of follow-ing methods (thoroughly explained in the followfollow-ing sub sections):

o Wand and Weber ontological analysis method [59] to evaluate the mappings from the ICT plans to COBIT 5, presented in Section 7.1. o Moody and Shanks Framework to evaluate the modeled processes

re-sulting from the proposed method [60].

o Submission of papers to international conferences and journals with our findings.

• An ex post evaluation – we will use as quality measure the opinions of human subjects under a real system setting [58]. This will be performed through the following method (thoroughly explained in the Section 8.3):

o Interviews with the same set of subjects previously interviewed to ob-tain the situational indicators and to perform the analysis of need. These steps have as goal:

1) Ensuring the scientific correctness of the proposal;

2) Assessing how much the proposal satisfies the solution’s objectives;

8.1 Wand and Weber Method

After analyzing the obtained results from the mappings we need to evaluate the mapping itself. Hence, to evaluate the mappings from PGETIC and UK ICT Plan measures to COBIT 5 processes we will perform an analysis based on the Wand and Weber ontologi-cal evaluation of grammars method. This method compares one set of measures with one of processes to identify four ontological deficiencies (consider two hypothetical sets, A and B, for explanatory purposes):

• Incompleteness: can every element from the first set be mapped onto an ele-ment from the second? Every eleele-ment from A has one correspondent in B; oth-erwise, there is incompleteness.

• Redundancy: is the first set elements mapped to more than a second set ele-ment? There is redundancy if one element from A has two or more correspond-ents in B. There is ambiguity.

• Excess: is every first set element mapped on a second set one? The mapping is excessive if there are elements in B without a correspondent in A.

• Overload: is every first set element mapped to exactly one second set element? The mapping is overloaded if any element from B has more than one corre-spondent in A.

8.1.1 Mappings evaluation

The mappings were made through the assignment of the ICT plans’ measures to COBIT 5. Each paragraph corresponds to the analysis of one deficiency.

When we analyze the completeness we conclude both mappings are complete. Every measure from the plans had, at least, one correspondent COBIT 5 process. This reveals that COBIT 5 includes everything both plans have.

As for redundancy, it was very frequent to find one measure that had several corre-spondent processes. To clarify this, while doing the mapping, we created a mapping to the COBIT 5 processes practices, Table 2 in Appendix C. Thus, we can identify the practices of each process considered by each measure. By doing so, we concluded the redundancies were not that frequent and, on the several cases where they happened, they are with generic processes with a broad scope. Despite several measures are partially redundant, that is not important to our mappings because each measure as several ob-jectives. Thence, is very likely it will cover practices of several processes. The case were redundancy did not existed were very rare and improbable.

We also found several cases of excess, especially in the PGETIC – COBIT 5 map-ping. Forty-one percent of the processes did not have any measure covering them. That represents an excess of almost half the COBIT 5 processes. The UK ICT Plan had a much lower rate, just five percent of excess. This allows us to conclude that PGETIC has a much narrower scope, but also that to all PGETIC measures COBIT 5 has correspond-ing processes.

Finally, we have overload, this is the deficit that really matters in our case. If we just look the mappings, Table 1 (Appendix C) and Table 3 (Appendix D) we would say there are numerous overloads, however, that is not entirely true. When we analyze the

seriousproblem. Several practices were covered by several measures. This represents a waste of resources and time

8.2 The Moody and Shanks Framework

Afterwards, we need to evaluate the generated processes by our method. According to the data model definition provided by Hoberman [61], we can consider our modeled pro-cesses as data models. Therefore, we will perform their evaluation using the Moody and Shanks Framework [39] for process quality management. This framework proposes the following quality factors:

• Completeness refers to whether the model contains all user requirements; • Integrity definition of business rules or constraints from the user requirements

to guarantee model integrity;

• Flexibility is defined as the ease with which the model can reflect changes in requirements without changing the model itself;

• Understandability the ease with which the concepts and structures in the model can be understood;

• Correctness is defined as whether the model is valid (i.e. conforms to the rules of the modeling technique). This includes diagramming conventions, naming rules, definition rules, and rules of composition and normalization;

• Simplicity means that the model contains the minimum possible constructs; • Integration is related to the consistency of the models within the rest of the

or-ganization;

• Implementability is defined as the ease with which the model can be imple-mented within the project time, budget and technology constraints.

8.3 Interviews methodology

In the interviews we will present the processes achieved through the proposed method. Then, to receive feedback we will follow three approaches [62]:

• First, we will execute a closed, fixed field response interview [62]. This way, questions and response categories are determined in advance. The respondent chooses from among a set of fixed responses.

The collected data is simple to analyze; responses can be directly compared and easily aggregated.

• Second, we will execute a standardized open-ended interview [62]. All inter-viewees are asked the same basic questions in the same order. Questions are worded in a completely open-ended format.

Respondents answer the same questions, thus increasing comparability of re-sponses; data are complete for each person on the topics addressed in the inter-view.

8.4 Submission of papers

An important way of evaluation is the submission of papers to international conferences and journals with our findings. This gives us the chance to receive valuable feedback from the scientific community. The appraisal of the scientific community constitutes one approach of certifying the scientific contribution of our thesis.

Moreover, the submission of papers is also one way to communicate our work, the fi-nal step of DSRM.

9

Conclusion

In this thesis we propose to apply a situational method to reduce ICT expenses in the Portuguese Public Administration. Up until now we first presented the comparison be-tween the diverse ITG frameworks and our reasons to choose COBIT 5. Furthermore, we mapped two different ICT strategic plans implemented in the Public Administration of different countries to COBIT 5 (Section 7.1). This mapping was made process-by-process, measure-by-measure, providing us enough material to create the method base of our proposal.

The method base comprises: • The full COBIT 5 processes;

• The situational factors of the method fragments; • The maturity capabilities of the fragments; • The assembly rules of the fragments.

This method base constitutes the source of knowledge of our method. Notwithstand-ing the use of known, exhaustive and recognized framework of good practices in IT gov-ernance and management, such as COBIT 5, we could still improve the method base. One option could be frameworks that are complementary to COBIT, such as frameworks in Enterprise Transformation (e.g. Business Transformation Management Methodology from Uhl and Gollenia); or frameworks with different scope (e.g. ITIL). Thus, we can add as many frameworks as we want in order to complement the method base.

One of the big advantages of this method is that these insertions can be performed without changes in the method itself, just in the constitution of one artifact. The only re-quired step is the execution of a framework comparison to ensure compliance between frameworks and the non-existence of overlaps. An example of such comparison is pre-sented by Weerd et al. in [63].

As future work we will apply the method in an IT department of some ministry of PPA. We will demonstrate and evaluate the results of that application. In Appendix A, we present a Gantt chart with these activities scheduled in time.

References

[1] P. Beynon-Davies, Information systems: an introduction to informatics in organisations. Ba-singstoke: Palgrave, 2002.

[2] B. Hochstrasser, Controlling IT investment: strategy and management, 1st ed. London ; New York: Chapman & Hall, 1991.

[3] L. Marsh and R. Flanagan, “Measuring the costs and benefits of information technology in construction,” Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag., vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 423–435, Dec. 2000.

[4] K. Brand and H. Boonen, IT Governance Based on CobiT® 4.1: A Management Guide. Van Haren Publishing, 2007.

[5] W. Grembergen, “Introduction to the Minitrack ‘IT Governance and Its Mechanisms,’” in 40th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hawaii, 2007, pp. 233– 233.

[6] IT Governance Institute, ISACA, “Board Briefing on IT Governance,” 2001. [Online]. Avail-able: http://www.itgi.org/.

[7] P. Weill, IT governance: how top performers manage IT decision rights for superior results. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2004.

[8] IT Governance Institute, ISACA, “IT Governance Roundtable: Defining IT Governance.” 2009.

[9] P. Webb, C. Pollard, and G. Ridley, “Attempting to Define IT Governance: Wisdom or Fol-ly?,” in HICSS ’06 Proceedings of the 39th Annual Hawaii International Conference on Sys-tem Sciences, DC, USA, 2006, vol. 08, p. 194a.

[10] S. Looso, M. Goeken, and W. Johannsen, “Comparison and Integration of IT Governance Frameworks to support IT Management,” Qual. Manag. IT Serv. Perspect. Bus. Process Per-form., vol. 90, Sep. 2010.

[11] ISACA, “Comparing COBIT 5 and 4.1,” isaca.org, May-2012. [Online]. Available: http://www.isaca.org/COBIT/Documents/Compare-with-4.1.pdf. [Accessed: 03-Dec-2012]. [12] S. De Haes, W. Van Grembergen, and R. S. Debreceny, “COBIT 5 and Enterprise

Govern-ance of Information Technology: Building Blocks and Research Opportunities,” J. Inf. Syst., vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 307–324, Jun. 2013.

[13] J. Carracha, “Maturidade da Gestão Informática na Administração Pública Portuguesa,” MSc thesis, Instituto Superior Técnico, 2010.

[14] Diário da República, “Resolução do Conselho de Ministros n.o12/2012,” Diário da República, 1.asérie - N.o 27, Fevereiro 2012.

[15] Grupo de Projecto para as Tecnologias de Informação e Comunicação. GPTIC, “Plano global

estratégico de racionalização e reduçao de custos nas TIC, na Admiñ istração Pública,”

portu-gal.gov.pt, 2011. [Online]. Available: http://www.portugal.gov.pt/media/420578/pgerrtic.pdf. [Accessed: 15-Aug-2013].

[16] Cabinet Office, “UK government ICT Strategy: Strategic Implementation Plan - Publications - GOV.UK,” Mar-2011. [Online]. Available:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-government-ict-strategy-resources. [Ac-cessed: 07-Aug-2013].

[17] K. Peffers, T. Tuunanen, M. A. Rothenberger, and S. Chatterjee, “A Design Science Re-search Methodology for Information Systems ReRe-search,” J. Manag. Inf. Syst., vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 45–77, Dec. 2007.

[18] A. R. Hevner, S. T. March, J. Park, and S. Ram, “Design science in information systems re-search,” MIS Q, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 75–105, Mar. 2004.

[19] A. Vasconcelos, “Normas Abertas, Software Aberto... e Administração Aberta,” joinup.ec.europa.eu, 2013. [Online]. Available:

[20] A. Vasconcelos, “Plano global estratégico de racionalização e redução de custos nas TIC, na Administração Pública,” Direção Geral de Arquivos, 08-May-2012. [Online]. Available: http://dgarq.gov.pt/files/2012/04/Apres_AVasconcelos_08-05-2012.pdf. [Accessed: 02-Dec-2013].

[21] Diário da República, “Resolução do Conselho de Ministros n.o46/2011,” Diário da República, 1.asé

rie - N.o

128, Nov. 2011.

[22] J. Dias Coelho, “Considerações sobre a oportunidade e impato do PGETIC na AP,” itsmf.pt, 2012. [Online]. Available:

http://www.itsmf.pt/LinkClick.aspx?link=Conferencias%2F2012%2FitSMF+PT_Considerac oes+sobre+a+oportunidade+e+impato+do+PGETIC+na+AP_Jose+Dias+Coelho.pdf&tabid= 177&mid=749&language=pt-PT. [Accessed: 01-Dec-2013].

[23] H. Park, S. Jung, Y. Lee, and K. Jang, “The Effect of Improving IT Standard in IT Govern-ance,” in Computational Intelligence for Modelling, Control and Automation, 2006 and ternational Conference on Intelligent Agents, Web Technologies and Internet Commerce, In-ternational Conference on, Sydney, NSW, 2006, p. 22.

[24] M. Simonsson and P. Johnson, “Defining IT governance - A consolidation of literature,” KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Trita-EE, ISSN 1653-5146, 2005.

[25] W. Van Grembergen, S. De Haes, and E. Guldentops, “Structures, processes and relational mechanisms for IT governance.,” Strateg. Inf. Technol. Gov., vol. 1, pp. 1–36, 2004. [26] R. R. Peterson, “Integration strategies and tactics for information technology governance.,”

Strateg. Inf. Technol. Gov., vol. 2, pp. 37–80, 2004.

[27] National Computing Centre Limited, IT governance: developing a successful governance strategy : a best practice guide for decision makers in IT. Manchester: National Computing Centre, 2005.

[28] R. Pereira and M. M. da Silva, “Towards an Integrated IT Governance and IT Management Framework,” in 2012 IEEE 16th International Enterprise Distributed Object Computing Conference, DC, USA, 2012, pp. 191–200.

[29] S. De Haes and W. Van Grembergen, “IT governance and its mechanisms,” Inf. Syst. Control J., vol. 1, pp. 27–33, 2004.

[30] ISACA, “A COBIT 5 Overview,” isaca.org, May-2012. [Online]. Available:

http://www.isaca.org/COBIT/Documents/A-COBIT-5-Overview.pdf. [Accessed: 03-Dec-2012].

[31] Information Systems Audit and Control Association. ISACA, COBIT 5: A business frame-work for the governance and management of enterprise IT. Rolling Meadows. IL: ISACA, 2012.

[32] Information Systems Audit and Control Association. ISACA, COBIT 5 enabling processes. Rolling Meadows, Ill.: ISACA, 2012.

[33] Cabinet Office, “UK government ICT Strategy - Publications - GOV.UK,” Mar-2011. [Online]. Available: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/uk-government-ict-strategy-resources. [Accessed: 07-Aug-2013].

[34] Department of Finance and Deregulation, “Australian Public Service Information and Com-munications Technology Strategy 2012 - 2015,” finance.gov.au, 2012. [Online]. Available: http://www.finance.gov.au/publications/ict_strategy_2012_2015/docs/APS_ICT_Strategy.pdf . [Accessed: 10-Nov-2013].

[35] NZ Government Information Office, “Government ICT Strategy and Action Plan to 2017,” http://ict.govt.nz/, 2013. [Online]. Available: http://ict.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Government-ICT-Strategy-and-Action-Plan-to-2017.pdf. [Accessed: 10-Nov-2013].

[36] Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology, “ICT Strategy of the German Federal Gov-ernment: Digital Germany 2015,” bmwi.de, 2010. [Online]. Available:

http://www.bmwi.de/English/Redaktion/Pdf/ict-strategy-digital-germany-2015,property=pdf,bereich=bmwi,sprache=en,rwb=true.pdf. [Accessed: 10-Nov-2013]. [37] Jordan IT Office, “Jordan National Information and Communications Technology Strategy

http://www.moict.gov.jo/Portals/0/PDF/NewFolder/ADS/Tender2/Final%20Draft%20Jordan %20NIS%20June%202013.pdf. [Accessed: 10-Nov-2013].

[38] MAMPU, “Malaysian Public Sector ICT Strategic Plan (2011-2015),” mampu.gov.my, 2011. [Online]. Available:

http://www.mampu.gov.my/documents/10228/11682/ISPplan2011.pdf/f746793c-b6f2-45a9-9f57-b841163fe6ed. [Accessed: 10-Nov-2013].

[39] NSW ICT Board, “NSW Government ICT Strategy,” http://finance.nsw.gov.au/, 2013. [Online]. Available:

http://finance.nsw.gov.au/ict/sites/default/files/ICT%20Strategy%20Implementation%20Upd ate%202013-14.pdf. [Accessed: 10-Nov-2013].

[40] Rwanda Development Board – ICT Department, “Rwanda ICT Strategic and Action Plan (NICI III – 2015),” rdb.rw, 2011. [Online]. Available:

http://www.rdb.rw/uploads/tx_sbdownloader/NICI_III.pdf. [Accessed: 10-Nov-2013]. [41] Cabinet Office, “One year on: implementing the government ICT strategy - Publications -

GOV.UK,” May-2012. [Online]. Available:

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/one-year-on-implementing-the-government-ict-strategy. [Accessed: 07-Aug-2013].

[42] A. Issa-Salwe, M. Ahmed, K. Aloufi, and M. Kabir, “Strategic Information Systems Align-ment: Alignment of IS/IT with Business Strategy,” J. Inf. Process. Syst., vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 121–128, Mar. 2010.

[43] S. Brinkkemper, M. Saeki, and F. Harmsen, “Meta-modelling based assembly techniques for situational method engineering,” Inf. Syst., vol. 24, no. 3, pp. 209–228, May 1999.

[44] F. Harmsen, S. Brinkkemper, and J. L. Han Oei, “Situational method engineering for infor-mational system project approaches,” in Proceedings of the IFIP WG8.1 Working Conference on Methods and Associated Tools for the Information Systems Life Cycle, New York, USA, 1994, pp. 169–194.

[45] T. W. Olle, J. Hagelstein, I. G. MacDonald, and C. Rolland, Information systems methodolo-gies: a framework for understanding, 2nd ed. Wokingham, England ; Reading, Mass: Addi-son-Wesley, 1991.

[46] S. Brinkkemper, “Method engineering: engineering of information systems development methods and tools,” Inf. Softw. Technol., vol. 38, no. 4, pp. 275–280, Jan. 1996.

[47] A. Gericke and R. Winter, “Situational Change Engineering in Healthcare,” in Proceedings of the European Conference on eHealth 2006, Bonn, Germany, 2006, pp. 227–238.

[48] U. Baumöl, “Strategic agility through situational method construction,” in Proceedings of the European Academy of Management Annual Conference 2005, München, 2005, pp. 1–34. [49] N. Labusch and R. Winter, “Method Support of Large-Scale Transformation in the Insurance

Sector: Exploring Foundations,” in Trends in Enterprise Architecture Research and Practice-Driven Research on Enterprise Transformation, vol. 131, S. Aier, M. Ekstedt, F. Matthes, E. Proper, and J. L. Sanz, Eds. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012, pp. 60–78. [50] L. Luinenburg, S. Jansen, J. Souer, I. Van De Weerd, and S. Brinkkemper, “Designing web

content management systems using the method association approach,” in Proceedings of the 4th International Workshop on Model-Driven Web Engineering (MDWE 2008), 2008, pp. 106–120.

[51] I. van de Weerd, S. Brinkkemper, and J. Versendaal, “Incremental method evolution in global software product management: A retrospective case study,” Inf. Softw. Technol., vol. 52, no. 7, pp. 720–732, Jul. 2010.

[52] I. Van De Weerd, S. Brinkkemper, and J. Versendaal, “Concepts for Incremental Method Evolution: Empirical Exploration and Validation in Requirements Management,” in Ad-vanced Information Systems Engineering. Proceedings of the 19th International Conference, CAiSE 2007, vol. 4495, J. Krogstie, A. Opdahl, and G. Sindre, Eds. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2007, pp. 469–484.

![Figure 1: The DSRM process (adapted from [17]).](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_br/16301446.717413/3.892.186.719.787.942/figure-dsrm-process-adapted.webp)

![Figure 4: IT Governance and IT Management (from [26, p. 44]).](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_br/16301446.717413/7.892.293.603.415.641/figure-governance-management-p.webp)

![Figure 5: Evolution of COBIT (adapted from [30]).](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_br/16301446.717413/8.892.282.615.463.680/figure-evolution-cobit-adapted.webp)

![Figure 6: COBIT 5 key areas (Governance and Management) and its domains (the three blocks in the Governance area constitute a single domain) (from [31])](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_br/16301446.717413/9.892.209.682.140.415/figure-cobit-governance-management-domains-blocks-governance-constitute.webp)

![Figure 7: Process of configuration of situational methods (adapted from [47]).](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_br/16301446.717413/12.892.296.620.334.618/figure-process-configuration-situational-methods-adapted.webp)

![Figure 8: Thesis method (adapted from [52]).](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_br/16301446.717413/15.892.215.685.301.624/figure-thesis-method-adapted-from.webp)