Revista

de

Administração

http://rausp.usp.br/ RevistadeAdministração51(2016)344–354

Environmental

management

The

influence

of

civic

mindedness,

trustworthiness,

usefulness,

and

ease

of

use

on

the

use

of

government

websites

Influência

da

inclina¸cão

cívica,

confiabilidade,

utilidade

e

facilidade

de

uso

sobre

o

uso

de

websites

governamentais

La

influencia

de

la

inclinación

cívica,

la

confiabilidad,

la

utilidad

y

la

facilidad

de

uso

en

el

uso

de

los

sitios

web

gubernamentales

Flávio

Perazzo

Barbosa

Mota

∗,

Carlo

Gabriel

Porto

Bellini,

Juliana

Morais

da

Silva

Souza,

Terezinha

de

Jesus

Nogueira

Oliveira

UniversidadeFederaldaParaíba,JoãoPessoa,PB,Brazil

Received12December2014;accepted27May2016

Abstract

Civicmindednessandtheperceptionsoftrustworthiness,usefulness,andeaseofuseseemtoexplainmuchoftheeffectiveuseofwebsites.This articlediscussestheextenttowhichsuchfactorsinfluencetheuseofgovernmentwebsitesbasedonastudywith210citizenswhoweredoingtheir biometricelectoralregistrationinJoãoPessoa–amajorcityinBrazil.Withthehelpofordinaryleastsquaresandquantileregressionmodels,we foundthatthereismixedinfluenceofthosefactorsontheuseofgovernmentwebsites.Onaverage,perceivedusefulnessandperceivedeaseofuse hadasignificantinfluence;butforlowlevelsofuse,onlyperceivedusefulnesshadaninfluence,whereasperceivedeaseofusehadaninfluencefor moderateandhighlevelsofuse.Intermsoftrustworthiness,onlythedimensionabouttrustingovernmenthadaninfluenceforalllevelsofuse.In termsofcivicmindedness,onlythedimensionaboutcivicengagementhadaninfluence,exceptformoderatelevelsofuse.Ourresultsreinforce thatthedevelopmentofgovernmentwebsitesshouldfocusonthecitizens’individualprofilesandlevelsofuse,thatis,focusshouldbedirected tothedemandside(users)besidesmerelyaddressingthelegalrequirementsandtheprovisionofservicesbythesupplier(government).

©2016DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP. PublishedbyElsevierEditoraLtda.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBYlicense(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Keywords: Electronicgovernment;Websiteuse;Civicmindedness;Trustworthiness;Perceivedusefulness;Perceivedeaseofuse

Resumo

Inclinac¸ãocívicaeaspercepc¸õesdeconfiabilidade,utilidadeefacilidadedeusoparecemexplicarousoefetivodesítiosweb.Esteartigodiscute ograuemque taisfatoresinfluenciamousodesítioswebgovernamentaisapartirdeumestudocom210cidadãosqueseencontravamem processoderegistroeleitoralbiométriconacidadedeJoãoPessoa,Brasil.Comapoiodométododosmínimosquadradosordinários(OLS)e modelosquantílicosderegressão,descobriu-sequeháinfluênciamistadaquelesfatoressobreousodesítioswebgovernamentais.Emmédia, utilidadepercebidaefacilidadedeusopercebidaapresentaraminfluênciasignificativa;contudo,emníveisbaixosdeuso,apenasutilidadepercebida apresentouinfluência,enquantofacilidadedeusopercebidaapresentouinfluênciaemníveismoderadosealtosdeuso.Emtermosdeconfiabilidade, apenassuadimensãodeconfianc¸anogovernoapresentouinfluênciaemtodososníveisdeuso.Emtermosdeinclinac¸ãocívica,apenassuadimensão

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:flaviopbm@gmail.com(F.P.B.Mota).

PeerReviewundertheresponsibilityofDepartamentodeAdministrac¸ão,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸ãoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeSão Paulo–FEA/USP.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rausp.2016.07.002

deengajamentocívicoapresentouinfluência,comexcec¸ãoemníveismoderadosdeuso.Osresultadosreforc¸amqueodesenvolvimentodesítios webgovernamentaisdevefocarnosperfisindividuaisenosníveisdeusodoscidadãos;ouseja,ofocodevesertambémdirecionadoaoladoda demanda(usuários),emvezdeapenasaosrequisitoslegaiseaofornecimentodeservic¸osporpartedoofertante(governo).

©2016DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP. PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCCBY(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Palavras-chave:Governoeletrônico;Usodesítiosweb;Inclinac¸ãocívica;Confiabilidade;Utilidadepercebida;Facilidadedeusopercebida

Resumen

Inclinacióncívicaylaspercepcionesdeconfiabilidad,utilidadyfacilidaddeusoparecenexplicargranpartedelusoefectivodelossitiosweb.En esteartículoseanalizaelgradoenqueestosfactoresinfluyenenelusodelossitioswebdelgobiernosobrelabasedeunestudiocon210ciudadanos queestabanhaciendosuregistroelectoralbiométricoenJoãoPessoa-unagrandeciudadenBrasil.Conlaayudademodelosderegresión(mínimos cuadradosordinariosyporcuantiles),seencontróqueexisteinfluenciamixtadeesosfactoresenelusodelossitioswebgubernamentales.En promedio,lautilidadpercibidaylafacilidaddeusopercibidatuvieronunainfluenciasignificativa;peroparalosbajosnivelesdeutilización, solamentelautilidadpercibidatuvounainfluencia,mientrasquelafacilidaddeusopercibidatuvounainfluenciaparanivelesmoderadosyaltosde uso.Entérminosdeconfiabilidad,sóloladimensióndelaconfianzaenelgobiernotuvounainfluenciaparatodoslosnivelesdeuso.Entérminosde civismo,sóloladimensiónsobreparticipacióncívicatuvounainfluencia,aexcepcióndenivelesmoderadosdeuso.Nuestrosresultadosrefuerzan queeldesarrollodesitioswebdelgobiernodebecentrarseenlosperfilesindividualesdelosciudadanosyenlosnivelesdeuso,esdecir,elfoco debeestardirigidohaciaelladodelademanda(usuarios),ademásdesimplementehacerfrentealosrequerimientoslegalesylaprestaciónde serviciosporelproveedor(gobierno).

©2016DepartamentodeAdministrac¸˜ao,FaculdadedeEconomia,Administrac¸˜aoeContabilidadedaUniversidadedeS˜aoPaulo–FEA/USP. PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Esteesunart´ıculoOpenAccessbajolalicenciaCCBY(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Palabrasclave: Gobiernoelectrónico;Usodesitiosweb;Inclinacióncívica;Confiabilidad;Utilidadpercibida;Facilidaddeusopercibida

Introduction

Electronic government(e-gov) hasbeen considered atool totransformtherelationshipbetweenpublicadministrationand society.Thisispartlyduetothepotential that Internet appli-cationshave, alongwiththetypically pooruseof technology thatpublicadministratorsdo(Streib&Navarro,2006).The per-spectivesthatarebasedonthesupplysideor therelationship betweengovernmentandsociety,andtherelativelackof stud-iesonthedemandsideor theinteractionbetweenthecitizens andtheirgovernmentsalsocontributetosuchareality(Damian &Merlo,2013;Rana, Dwivedi,&Williams,2013b;Reddick, 2005).Nevertheless, e-gov has the potential tospan all gov-ernmentfunctionsandactivitiesthatare shapedbytheuseof informationandcommunicationtechnologies(ICTs)(Brown, 2005),so thatareciprocalrelationshipbetweenthe ICTsand thesocial,politicalandorganizationalfactorsmayinfluencethe successofe-gov(Helbig,Gil-García,&Ferro,2009).

Accordingtoacitizen-centeredperspective,amyriadof fac-torsinfluencetheuseofe-govservicesandtools.Forinstance, technologyacceptancemodel’s(TAM)perceivedusefulnessand perceivedeaseofuseareparticularlyappropriateforthestudy ofcitizen-orientede-gov(Rana,Dwivedi,&Williams,2013a). Nevertheless,thoseconstructsshould notbe studiedin isola-tioninthedomainofinformationsystemsadoption(Benbasat &Barki, 2007;Lee, Kozar, &Larsen, 2003). In the particu-lardomainofe-gov,psychologicalandsocialfactorsshouldbe included(Carter,2008;Ranaetal.,2011,2013a,b),suchas trust-worthiness(Avgerou, Ganzaroli,Poulymenakou, &Reinhard, 2009;Bannister&Connolly,2011;Belanche,Casaló,&Flavián, 2012;Carter &Bélanger, 2005;Carter&Weerakkody,2008; Lim et al., 2011; Morgeson, Vanamburg, & Mithas, 2011;

Schaupp&Carter,2010;Smith,2011;Srivastava&Teo,2009; Weerakkodyetal., 2013;Welch,2004)andcivicmindedness (Dimitrova&Chen,2006;Farinaetal.,2013;Kang&Gearhart, 2010).Otherconstructsthatarepopularintechnologyadoption research,suchascomputerself-efficacy,socialinfluenceandthe mediatingfactorsarenotenoughtoexplaintheintentiontouse andtheeffectiveuseofe-gov(Carter,2008;Costa,deOliveira, Dandolini,deSouza,2014;Ranaetal.,2011,2013a,b),sothey arenotaddressedinthisarticle.

TheBrazilianliteraturehasstudiesaboutcitizensande-gov use(e.g.,Damian&Merlo,2013;DeAraujo,2013;DeAbreu &De Pinho,2014),butitseemsthat theyare limitedindata typeandscope.Forinstance,De AbreuandDePinho(2014) andDamian and Merlo(2013)use observation-based datato analyzegovernmentwebsitesintermsoftheavailableservices andtheparticipationofpeopleindigitaldemocracyprocesses, whereasDeAraujo(2013)makesuseofsecondarydata,thatis, adatasetthatisoutoftheresearcher’scontrol.

Ourarticleseekstoanswerthefollowingresearchquestion: Towhichdegreedocivicmindedness,trustworthiness, useful-ness,andeaseofuseinfluencetheuseofgovernmentwebsites? Towardthat,weselectedwebsitesthatarebothaninstrument for informationand services, but also for the collective par-ticipation ofcitizensandgovernmentalikeinpublic interests (Sandoval-Almazan&Gil-Garcia,2012). Thearticle is orga-nized as follows:first,we discuss thetheoretical background according toa demand viewof e-gov,andalso according to theperspectiveofanindividual’sdigitallimitations;second,we discusstheempiricalmethod,withaparticularemphasisonthe measuresandproceduresfordatacollectionandanalysis;third, wediscusstheresultsonthebasisofdescriptivemeasures,the psychometricconsistencyoftheconstructsofinterest,the ordi-naryleastsquares(OLS)andquantileregressionmodels,and thedifferencesthatwefoundbasedontheregressionmodels; andfourth,weconcludebyreflectingthatthedevelopmentof e-govtoolsshouldfocusonthecitizens’individualprofilesand levelsofuse,thusaddressingthedemandside(user)inaddition tothelegalrequirementsandthemereprovisionofservicesby thesupplier(government).

Theoreticalbackground

Studies on e-gov may be classified according to a sup-ply view – whose focus is on what is offered by the public administration – or a demand view – whose focus is on the interactionbetweenthecitizensandthe publicadministration (Reddick,2005).The digital divide debatehas much to con-tributetothedemandview,givenitsinterestontheuseranda multi-perspectiveapproach(Helbig,Gil-García,&Ferro,2009). Weherefollowthe perspectiveof digital limitations(Bellini, Giebelen,&Casali,2010;Bellini,IsoniFilho,Garcia,&Pereira, 2012)ordigitaleffectiveness(Bellini,IsoniFilho,DeMoura,& Pereira,2016)inordertoframetheuserofe-govtoolsaccording tohis/hercognitivecapabilitiesandlimitationsthataccountfor thedigitalskillsneededforhim/hertomakeeffectiveuseofthe ICTs.

Inordertoappraiseone’scognitivelimitationsinregardto e-gov,we adoptasetof proxymeasuresdescribed inthe lit-eratureaboutthe demandfore-gov,such aswhentechnology adoptionmodelsareappliedtomeasuringtheintentiontouseor theeffectiveuseofe-govbyindividuals(e.g.,Ranaetal.,2011, 2013a).Wealsoselectforthisstudyaspecificsetofconstructs thatseemtohaveaninfluenceovertheuseofe-govtools:civic mindedness,andtheperceptionsoftrustworthiness,usefulness, andeaseofuse.Theseconstructshavebeenusedtoexplaine-gov use(Carter,2008;Dimitrova&Chen,2006;Kang&Gearhart, 2010;Ranaetal.,2013a)andtheyaddresssomeaspectsrelated tothecognitivedigitallimitations.

Perceivedusefulnessandperceivedeaseofusearethewidely knownconstructsofTAM(Davis,1989).Besidesbeing popu-larininformationsystemsresearchingeneral,TAMhasbeen widely used in e-gov as well (Lee et al., 2003; Rana et al., 2013a).AlthoughTAMwasdevelopedtodescribecompulsory useofinformationsystems,itsusesinothercontextsarewidely reported(Leeetal.,2003).

Perceivedusefulness,orthedegreetowhichauserbelieves that usingagivensystemwouldimprovehis/herwork perfor-mance, is the most significant factor of technology adoption (Benbasat&Barki,2007).Researchontheintentiontouseor theeffectiveuseofe-govhaveconsistentlyfoundthisfactoras significanttoexplaintheadoptionof e-govtools(e.g.,Carter, 2008; Carter&Bélanger,2005; Carter&Weerakkody,2008; Dimitrova&Chen,2006;Hung,Chang,&Yu,2006;Ranaetal., 2013a).Ontheotherhand,perceivedeaseofuse,orthedegree towhichauserbelievesthatusingagivensystemwouldbefree of effort,isalsoreportedinsomestudiesasanimportant fac-torfore-govadoption(Carter&Bélanger,2005;Hungetal., 2006;Kolsaker&Lee-Kelley,2008).Infact,asystematic liter-aturereviewbyRanaetal.(2013b)aboutthemodelsdeployed incitizen-focusede-govresearchconfirmedtheperceptionsof usefulnessandeaseofuseasfactorsfortheadoptionofe-gov. Thisleadstoourfisttwohypohteses:

H1. Perceivedusefulnesshasapositiveinfluenceontheuseof governmentwebsites.

H2. Perceivedeaseofusehasapositiveinfluenceontheuse ofgovernmentwebsites.

Beliefsrelatedtotrustarekeyfortheenactmentof trustwor-thinessingovernmentwebsites(Belancheetal.,2012;Carter& Bélanger,2005;Carter&Weerakkody,2008;Schaupp&Carter, 2010;Srivastava&Teo,2009;Teo,Srivastava,&Jiang,2008; Weerakkodyetal.,2013).Trustworthinessisdefinedasa citi-zen’strustinhis/hergovernment’scompetencetomakeInternet services available (Carter & Bélanger, 2005; Lee & Turban, 2001; Limetal.,2011; Srivastava&Teo,2009;Weerakkody etal.,2013),thatis,itistrustintheservice’sagentandthe tech-nology(Carter&Bélanger,2005;Carter&Weerakkody,2008; Srivastava&Teo,2009).

Intermsoftrustingovernment,therelationshipbetweenthe governmentandthecitizensplaysaprominentroleinthe for-mation of trust in government’s websites (Teo et al., 2008). This means that the use of e-gov tools is dependent on the individuals’ perception that their government has the needed competencetodevelopandassurethesecurityofe-govsystems (Carter & Weerakkody,2008; Carter etal., 2011; Limet al., 2011;Srivastava&Teo,2009;Weerakkodyetal.,2013). Trans-parentandreliableelectronicinteractionswiththegovernment are likely toincrease trustand acceptanceof e-gov services; but frauds, corruption and unfulfilled promises are likely to decrease trustandincreaseresistancetowarde-gov(Carter& Weerakkody,2008;Limetal.,2011).

H3. Perceivedtrustworthinesshasapositiveinfluenceonthe useofgovernmentwebsites.

H3a. Trustinthegovernmenthasapositiveinfluenceonthe useofgovernmentwebsites.

H3b. TrustintheInternethasapositiveinfluenceontheuse ofgovernmentwebsites.

Civic mindedness broadly refers to adhering to the civic dutiesasawaytorealizesociallydesirablevalues(Kametal., 1999),anditalsoreferstotheindividualattitudetoward sacri-ficingtimeandeffortinordertoprovidepublicinterestservices (Hechter,Kim,&Baer,2005).Civicmindednessmayinclude thesupport todemocratic processes,a representative govern-ment,andthe existenceof andparticipationinelectoralpolls (Kametal.,1999);socialcontact,previousinterestin govern-ment,andthe useof mediafor thedebate of publicinterests (Dimitrova&Chen, 2006); andjudgingone’scharacter, par-ticipatingincommunityservices,as wellasanindividualand collectivesenseof obligationtowardthecommunity(Hechter etal.,2005;Kang&Gearhart,2010).Inourstudy,civic minded-nesshasthreedimensions:civicengagement,civicvalues,and democracyandcitizenship.

Through the use of websites, public administration may motivatecitizenstoamplifytheircommunityengagementand participation(Farinaetal.,2013).Whencitizensusethe elec-tronic means to interact with government, they mimic the communityroutines that takeplace inmoretraditional chan-nels(Dimitrova&Chen,2006).Forinstance,theuseofdirect democracyservicesandresourcesingovernmentwebsitessuch as policy meetings, online consultation, virtual meeting, dis-cussion forums, and voting relates to civic engagement and politicalbehaviorsuchasparticipatinginpoliticalcampaigns, publichearings,petitiondrives,andprotests(Kang&Gearhart, 2010);andtheactofvotingbytheeldestrelatestocivic mind-edness,since such an actionis assumed tobe relatedto the perceptionofcivicduty(Kametal.,1999).Also,individuals whohavehighercivicmindednessaremorelikelytousee-gov services (Dimitrova& Chen, 2006). Thisleads toour fourth hypohtesis:

H4. Civicmindednesshasapositiveinfluenceontheuseof governmentwebsites.

H4a. Civicengagementhasapositiveinfluenceontheuseof governmentwebsites.

H4b. Democracyandcitizenshiphaveapositiveinfluenceon theuseofgovernmentwebsites.

H4c. Civicvalueshaveapositiveinfluenceontheuseof gov-ernmentwebsites.

Method

Ourempiricalstudywasapsychometricsurveythatcollected answersfromrespondentsbymeansofan11-pointLikert-like agreement scale. The answers were submitted to regression analysis,whosedependentandindependentvariablesaregiven

inTable1:theuseofgovernmentwebsites(dependentvariable), perceivedusefulness,perceivedeaseofuse,trustworthiness,and civicmindedness(independentvariables).Usefulnessandease of use were measured with a single statement each, sinceit seems that both are unidimensional (Rossiter &Braithwaite, 2013). Trustworthinessand civicmindedness were measured withseveralstatements.Thedependentvariable(theuseof gov-ernmentwebsites)wasmeasuredasthearithmeticmeanofthree items.

Allitems inTable1wereadapted fromthe literature.The itemswerevalidatedintermsofmeaningandclarityintwo meet-ingsoftheauthors’researchteam,whichincludesresearchers fromthefields ofmanagement,productionengineering, com-puterscience, informationscience,andeducation. Expertsin politicalscienceandpublicadministrationalsocontributed.The instrumentwasprovidedinprinttotheresearchersatthe meet-ings,andtheyassessedeachitemaccordingtoafive-pointscale from“totallyinadequate”(“1”)to“totallyadequate”(“5”)and alsoaccordingtoafive-pointscalefrom“veryunclear”(“1”) to“veryclear”(“5”).Theitemswerethoroughlydiscussedin groupandadaptedtotheBrazilianrealityandtothetechnology ofourinterest–governmentwebsites.

Anothermethodologicalstepwastodesignthequestionnaire intermsofitsgenerallayoutandthesequenceofitems.Thiswas alsodoneinanothermeetingoftheresearchteam.Demographic variableswereadded(gender,income,age,andeducation)and apre-testwasscheduled. Thepre-testwasdonewith30 indi-vidualsinDecember2013andJanuary 2014,withdatabeing analyzedinanothermeetingoftheresearchteam.

Thevalidatedquestionnairewasappliedtothefieldinthecity ofJoãoPessoa,whichisthecapitalofParaíba,astatein North-easternBrazil.Thiscitywasselectedforseveralreasons:(1)itis thecitywheretheresearcherswork,sotheanalysisofdatawould beenhancedbytheresearchers’knowledgeabouttheregional idiosyncrasies;(2)JoãoPessoahadabout791,000inhabitantsat thetimeofthesurvey(IBGE,2015b),beingamongthelargest citiesandmetropolitanareasinNortheasternBrazil;(3)interms ofMunicipalHumanDevelopmentIndex(IDHM),whichtakes intoaccountlongevity(longandhealthylife),education(access toknowledge)andincome(standardofliving),JoãoPessoais classifiedashighhumandevelopment,rankedasthefourthin Northeastand320thamongthe 5565Brazilianmunicipalities (AtlasBrasil,2015;PNUD,2015).

Non-probability sampling was applied to collect the data directlyatselectbiometricelectoral registrationoffices inthe city.Thedecisionwasbasedonthelikelihoodthatthoseoffices wouldbeagatheringplaceforalldemographicstrataof elec-torsatthattime,sincebiometricregistrationwasinprocessfora limitedtimeanditwasmandatoryforallelectorsbetween18and 70yearsofage.1Datacollectionwascarriedoutbytwoofthe authorsduringoneweekof January2014indifferentperiods of thedayandindifferentlocationsofbiometricregistration. Theresearchersapproachedtheelectorsfacetofaceandasked themtoanswervoluntarilythequestionnaire,withnomediation

Table1

Dependentandindependentvariables.

Dependentvariables

Values:from“totallydisagree”(“0”)to“totallyagree”(“10”)

Typeofuse Items

Information (UINFO)

1.Ifrequentlyusegovernmentwebsitestoobtaininformation(e.g.,aboutpublicagencies,transportation,safety,leisure,polls, etc.).

Services (USERV)

1.Ifrequentlyusegovernmentwebsitesforservices(e.g.,paytaxesorfees,obtainorrenewlicenses,etc.).

Interaction (UINT)

1.Ifrequentlyusegovernmentwebsitestointeractwiththegovernment(e.g.,participateindiscussionsaboutpublicpolicies, voting,meetings,interactionwithgovernmentrepresentatives,etc.).

Generaluse (USO)

Arithmeticmeanofthethreeitemsabove.

Independentvariables

Values:from“totallydisagree”(“0”)to“totallyagree”(“10”)

Construct Items

Perceivedusefulness (PU)

1.Comparingtootherwebsites,governmentwebsitesareuseful.

Perceivedeaseofuse (PEOU)

1.Comparingtootherwebsites,governmentwebsitesareeasytouse.

TrustintheInternet (CINT)

1.TheInternetissecureenoughformetofeelcomfortabletouseitininteractionswiththegovernment. 2.IamsurethatthelegalandtechnologicalresourcesareenoughtoprotectmeagainstproblemsintheInternet. 3.Ingeneral,theInternetisasolidandsecureenvironmentformetotransactwiththegovernment.

Trustingovernment (CGOV)

1.IfeelthatIcantrustingovernmentwebsites.

2.Itrustingovernmentwebsitestomakesecureelectronictransactions. 3.Inmyopinion,governmentwebsitesarereliable.

4.Itrustingovernmentwebsitestokeepinmindmybestinterests. Civicmindedness

(IC)

1.Everycitizenshouldbeconcernedaboutthepublicinterests. 2.Everycitizenshouldcasthis/hervoteinallpolls.

3.Votingisvalid,becauseitisawaytoexpressopinionsaboutthepublicinterests. 4.Everybodyhasthesamerights,regardlessofthepoliticalbeliefs.

5.Everybodyshouldhavetherighttoexpressfreely,regardlessofopinions. 6.Votinginapoliticalrepresentativehelpstoimprovethecommunity. 7.Whenthecommunity’sinterestsarethreatened,everybodyneedstooppose.

8.Ireadnewspapersinordertolearnaboutthegovernmentorgetinformationaboutthepublicinterests.

9.IhavebeenalreadyintouchwitharepresentativefromthegovernmentinordertosolveanissueofthecommunitywhereI live.

10.IfeellikeamemberofthecommunitywhereIlive. 11.IproposeideastoimprovethecommunitywhereIlive. 12.ItakepartofactivitiestoimprovethecommunitywhereIlive.

13.IworkwithotherpeopleinordertoimprovethecommunitywhereIlive. 14.Ifeeltheneedtohelptoimprovemycommunity.

Source:AdaptedfromCarterandBélanger(2005),Davis(1989),DimitrovaandChen(2006),Haller,Li,andMossberger(2011),Hechteretal.(2005),Kametal. (1999),KangandGearhart(2010),RossiterandBraithwaite(2013).

ofpublicemployeesthatwereinchargeofthe biometric reg-istration,sothatnoexternalinfluenceoccurredinselectingthe respondents.

Thenon-probabilityaspectofourdatacollectionisjustified bytheintentiontoapproachpeoplewhovoluntarilyrushedtothe biometricregistrationoffices–whattheresearchersinterpreted as a higher regardto the votingprocess andthe correspond-ingly expected attitude toward citizenship. However, from a certainmomenton,the sample wasmostlyformed byyoung people (below24 yearsof age), so theresearchers started to lookforolderpeopletoparticipateinthesurvey.Lessliterate adultsconstitutedthebiggestchallengeindatacollection,since thequestionsdemandedsomelevelofabstractthinking,online experience,andanadequateunderstandingofwhatwasbeing asked.Atthispoint,weneedtoremarkthatBrazilsuffersfrom astonishinglyincreasingratesofilliteracy,andtheNortheastis thepoorestandlesseducatedregioninthecountry.

Results

Dataanalysisconsistedoffoursteps:preliminaryexploratory assessment, descriptivestatistics of the sample, psychometric consistencyassessmentofthescales,andmultivariatedata anal-ysis(estimationofOLSandquantileregressionmodels).Data analysis was supported byMS-Excel 2010, SPSS 18, andR 2.15.3.

Preliminaryexploratoryanalysis

Table2 Sample.

Variable Possibleanswers n %

Gender Male 92 43.8

Female 118 56.2

Age From16to24yearsofage 95 45.2

From25to34yearsofage 53 25.2

From35to44yearsofage 30 14.3

Morethan44yearsofage 32 15.2

Education Elementaryormiddleschool 31 14.8

Highschool 104 49.5

Universityorcollege 75 35.7

Incomea UptoR$700.00(aboutoneminimumwage) 38 18.1

FromR$700.01toR$1400.00(about1–2minimumwages) 58 27.6 FromR$1400.01toR$2100.00(about2–3minimumwages) 34 16.2 FromR$2100.01toR$3500.00(about3–5minimumwages) 30 14.3 FromR$3500.01toR$7000.00(about5–10minimumwages) 30 14.3

MorethanR$7000.00(about10minimumwages) 20 9.5

a ThereferencewastheminimumwageofR$724.00permonthasof2014.

Inthesecondexploratoryprocedure,weexcluded13cases withmissing values in variablesmeasured by a single item; forthecategorical variablesof gender,income,age,and edu-cation, we excluded nine caseswith missingvalues; and for constructswithmorethanonedimension,weexcludedsixcases withduplicateormissingvaluesintwo or moreitemsof the samedimension.Wealsoanalyzedmissingvaluesbyitemand bycase,takingintoaccountthereferenceof10%ormore(Hair, Black,Babin,Anderson,&Tatham,2005).Noadditionalcase was excludedfollowingthat reference. The finaldataset was composedof224cases,withtheremainingmissingvaluesbeing replacedbytheaverageofthecorrespondingitem(variable).

Thethirdexploratoryprocedurewastheanalysisofatypical casesrepresentedbythestatisticaloutliers.Westartedwiththe standardz-scoresforcivicmindedness,trustworthiness, useful-ness,easeofuse,andthedependentvariable.Giventhesample size,univariateoutlierswerethosewhoseabsolutevalueswere4 orgreater(Hairetal.,2005).Threecaseswereexcludedfornot meetingthatreference,thusreducingthesampleto221cases. Additionally,weanalyzedleverageandinfluentialpointsforthe OLSregressionmodel,whatresultedin11newexclusionsfor theirimpactonthemodelfit–andafinalsetof210cases.

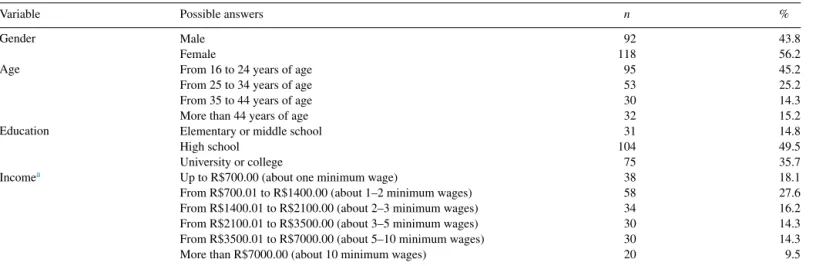

Sample

Our sample is mentioned in Table 2 according togender, age,education,andincome.Thereispredominanceoffemales (56.2%),peoplebetween16and24yearsofage(45.2%),high schoolastheeducationalbackground(49.5%),andincomeof uptotwominimumwages(27.6%).Datafromthenational cen-sus(IBGE,2015a)showthatwomenpredominatebothinBrazil (51%)andinthecityofJoãoPessoa(53.3%).Also,theage pyra-midisbecominglargerinthemiddlebothinBrazilandinJoão Pessoa(AtlasBrasil,2015;IBGE,2015a).Intermsof educa-tion,asof2010,49.91%ofthepopulationinJoãoPessoaover 25yearsofagehadahighschooldegree,with50.75%amongall Brazilians(AtlasBrasil,2015).Andintermsofincome,the aver-agedomesticmonthlyincomeinJoãoPessoawasR$3263.64as

of 2010(IBGE,2015b)or R$964.82percapita(AtlasBrasil, 2015), that is, almost two minimum wages at that time (the minimumwagewasR$510.00permonth).Althoughthe lead-ingnumbers ineachdemographicvariablearesimilarforour sample,theBrazilianpopulationandthepopulationofJoão Pes-soa,other numbers donot correspondperfectly. Anyway,we shouldrememberthatoursamplereferstovoters,nottothefull population.

Psychometricconsistencyofscales

Fortrustworthinessandcivicmindedness,theextracted vari-anceineachoftheirdimensionsshouldbeatleast50%,andthe scoresshouldbeatleast0.5duringexploratoryfactoranalysis. Asfortheinternalconsistencyestimateofreliability,Cronbach’s alphashouldbeatleast0.6.Bothreferencesweremet(Table3), so thatthe dimensionsarereliable tomeasurethe latent con-structs. The remaining constructs (perceived usefulness, and perceivedeaseofuse)areunivariate.

Descriptivemeasuresofconstructs

Forall constructs,the items were measuredfrom 0 to10. Table4givesthedescriptivemeasures,includingthedependent variable.

Table3

Trustworthinessandcivicmindedness.

Dimension Items(#) Extractedvariance(%) Minimumscore Alpha

TrustintheInternet 3 73.594 0.835 0.819

Trustingovernment 4 76.882 0.848 0.899

Civicengagement 5 69.462 0.755 0.889

Civicvalues 3 62.960 0.768 0.695

Democracyandcitizenship 3 66.705 0.782 0.743

Table4

Descriptivemeasures.

Dimensionorconstruct Mean Median Quartile Standarddeviation Skewness Kurtosis

1 3

Independentvariables

TrustintheInternet 3.78 3.67 2.00 5.33 2.16 0.343 −0.250

Trustingovernment 4.29 4.25 2.75 5.75 2.32 0.171 −0.557

Civicengagement 5.17 5.20 3.35 7.25 2.59 −0.211 −0.917

Civicvalues 8.98 9.50 8.33 10.0 1.35 −1.648 2.421

Democracyandcitizenship 7.08 7.67 5.67 9.00 2.51 −0.923 0.097

Perceivedusefulness 4.72 5.00 2.75 7.00 2.74 −0.065 −1.022

Perceivedeaseofuse 4.54 5.00 2.00 7.00 2.73 0.055 −1.018

Dependentvariable(useofgovernmentwebsites)

Aggregatemeasurea 3.84 3.67 2.00 5.67 2.25 0.387 −0.444

Information 5.14 5.00 3.00 8.00 2.80 −0.139 −0.955

Services 3.53 3.00 1.00 6.00 2.98 0.458 −0.974

Interaction 2.88 2.00 0.00 5.00 2.77 0.804 −0.292

aArithmeticmeanofthethreedimensions.

governmentmayreflectthefactthatBrazilianstrusttheprivate institutionsmorethanthepublicones(Almeida,2007).

Themeanandthemedianforcivicmindednesssuggestthat thisconstructreachedamoderatelevelforcivicengagement,a moderate-highlevelfordemocracyandcitizenship,andahigh levelforcivicvalues.Civicengagementhadthelowestvalues forthemeasuresofposition,maybeduetothelethargyofthe Braziliansociety(DePinho,2011).Themeasuresofdispersion suggestthat thereismoderateconvergence of the positionof respondentsaroundthemean.Andmeanandmedianvaluesfor civicvaluessuggestthatourrespondentsmayhavefocusedon whatismostlyexpectedfromthembysociety.

The mean andthe median for ease of use andfor useful-nesssuggestthattheseconstructsreachedamoderatelevel.The measuresofdispersionsuggestthat thereismoderate conver-gence of the position of respondents around the mean. This suggeststhat it isnecessarytoimprove the contents,the ser-vicesandthe interactivetoolsingovernmentwebsites.E-gov improvementsare infactneeded inmanyinstancesof public administrationforthesakeofbettercommunications, informa-tionavailability,transparency,democracy,andparticipation(De Pinho,2008).

Forthedependentvariable,thearithmeticmeanofthethree measuressuggeststhattheuseofgovernmentwebsitesreached alow-moderatelevel.Theuseofwebsitesforinformationhad the highest values for the measures of position, followed by services and interaction.The measures of dispersion suggest thatthereismoderateconvergenceofthepositionofrespondents aroundthemean.Forthedependent variable,theresultswere

similartotheBrazilianreality;infact,accordingtoCentrode EstudossobreasTecnologiasdaInformac¸ãoedaComunicac¸ão (CETIC.br, 2013),most e-govinBrazilreferstoinformation searchservices,suchasconsultingthesituationofindividuals, searchingfordirectionsonhowtoissuedocuments,searching for information onthe legislation of work, andsearching for publiceducation.Thisisfollowedbyservicessuchasincome declaration, tax andfee payments, and registeringfor public sectoremploymentopportunities.Finally,peopleusee-govto interactwithgovernmentingroupforums,chatrooms,andpolls. Thelowperceptionofe-govasanopportunitytointeractmay resultfromcertainaspectsoftheBraziliansociety,whichprefers moretraditionalparticipationchannels(CETIC.br,2013).

Regressionanalysis

Initially,weappliedOLSwithstepwise(backward)method. The dependent variablewas the arithmeticmean ofthe three measures(information,services,andinteraction)fortheuseof government websites. Table 5 shows the variablesthat were significant toexplain thedependent variable. The F-test sug-gests the model’s fit (p<0.001), explaining 38.27% of the total variance of the dependent variable (adjusted R2). Lil-liefors,Breusch–PaganandDurbin–Watsontestsappliedtothe residualssuggestthemodel’sfit intermsofnormality, homo-cedasticity,anderrorindependence,respectively.

Table5

OLSlinearregressionmodelfortheuseofgovernmentwebsites.

Independentvariable β Confidenceinterval (lower|upperbound)

t p-value

Intercept 0.3074 −0.3957|1.0106 0.8620 0.3896

Trustingovernment 0.2453 0.1267|0.3639 4.078 6.49e−05

Civicengagement 0.1602 0.0619|0.2584 3.215 0.00152

Perceivedeaseofuse 0.1754 0.0543|0.2965 2.856 0.00473

Perceivedusefulness 0.1830 0.0634|0.3025 3.017 0.00288

Regressiondiagnostic

F-test(4and205df) 33.4(p<0.001) Lillieforstestfornormality(p-value) 0.0449(0.3801)

R2 0.3945 Breusch–Pagan(7df)(p-value) 8.9741(0.2545)

AdjustedR2 0.3827 Durbin–Watson(p-value) 2.0743(0.606)

Table6

Quantileregressionmodelfortheuseofgovernmentwebsites.

Independentvariable Dependentvariable(quartiles)

0.25 0.50 0.75

β(p-value) β(p-value) β(p-value)

Intercept −1.2356(0.0602)a 0.4220(0.4580) 1.1210(0.0238)b

Trustingovernment 0.3183(0.0021)c 0.2492(0.0146)b 0.2363(0.0132)b

Civicengagement 0.2476(0.0038)c 0.0744(0.3718) 0.1519(0.0526)a

Perceivedeaseofuse 0.0736(0.4103) 0.2955(0.0089)c 0.3067(0.0124)b

Perceivedusefulness 0.1673(0.0613)a 0.1424(0.1657) 0.1684(0.1503)

PseudoR2 0.1777 0.2264 0.2841

a p<0.1 b p<0.05 c p<0.01

factors,higherlevelsofperceptionofusefulnessareassociated withhigherlevelsof useofgovernmentwebsites.Hypothesis H2aboutthepositiveinfluenceofperceivedeaseofuseonthe useofgovernmentwebsiteswasnotrejectedaswell(p<0.01); thatis,controllingforotherfactors,higherlevelsofperception ofeaseofuseareassociatedwithhigherlevelsofuseof govern-mentwebsites.HypothesesH3andH4werepartiallyrejected. Hypothesis H3a about the positive influence of trust in gov-ernmenton the useof government websites wasnot rejected (p<0.001);thatis,controllingforotherfactors,higherlevelsof perceptionoftrustingovernmentareassociatedwithhigher lev-elsofuseofgovernmentwebsites.AndHypothesisH4aabout thepositiveinfluenceofcivicengagementontheuseof govern-mentwebsiteswasnotrejected(p<0.01);thatis,controllingfor otherfactors,higherlevelsofcivicengagementareassociated withhigherlevelsofuseofgovernmentwebsites.

Inordertoassessthedegreetowhichtheindependent vari-ablesoftheOLSmodelinfluencethelevelsofuseofgovernment websites,wedevelopedaquantileregressionmodel(Table6). Ingeneral,quantileestimatorsaremoreefficientthanestimators fromthe OLS method(Buchinsky, 1998; Yu, Lu,&Stander, 2003).Themedian,forinstance,ismoremeaningfulthanthe meantoestimatethemiddlepointofapopulationinthepresence ofoutliers.Wedecidedtoassessthequartilesofthedependent variableasfollows:lowlevel of use(firstquartile), moderate

level of use (second quartile), and high level of use (third quartile).

AsforHypothesisH1,theresultssuggestthatperceived use-fulness hadasignificant andpositiveinfluence onthe useof governmentwebsitesonlyinthefirstquartile(lowlevelsofuse, p<0.1). Thisresultshould betaken withcare,giventhat the estimators(β)andthesignificancelevelsuggestthattheextent ofinfluenceofperceivedusefulnessontheuseofgovernment websiteswaslow.

AsforHypothesisH2,theresultssuggestthatperceivedease of usehad asignificant andpositive influenceon the use of governmentwebsitesinthemedian(secondquartile)andinthe third quartile(moderate and highlevels of use, p<0.01 and p<0.05).From the estimators (β),we mayconclude that the extentofinfluenceofperceivedeaseofusewasmarginallylarger inthethirdquartilethanthesecond.

AsforhypothesisH3a,theresultssuggestthattrustin gov-ernmenthadasignificantandpositiveinfluenceonthe useof governmentwebsitesinthethreelevels(p<0.01andp<0.05). From the estimators (β),we mayconclude that theextent of influenceoftrustingovernmentwaslargerinthefirstquartile thanintheothertwo.

Table7

Summaryoftests.

Hypothesis Hypothesistestingaccordingto modelingapproach

OLS Quantile

H1:Perceivedusefulness Notrejected Partiallyrejected H2:Perceivedeaseofuse Notrejected Partiallyrejected H3a:Trustingovernment Notrejected Notrejected H3b:TrustintheInternet Rejected –

H4a:Civicengagement Notrejected Partiallyrejected H4b:Democracyand

citizenship

Rejected –

H4c:Civicvalues Rejected –

p<0.01)andinthethirdquartile(highlevelsof use,p<0.1). Theinfluenceofcivicengagementwaslargerinthefirstquartile, buttheresultsforthethirdquartileshouldbetakenwithcare, giventhattheestimators(β)andthesignificancelevelsuggest that,inthatquartile,theextentofinfluenceofcivicengagement ontheuseofgovernmentwebsiteswaslow.

Table7showsthesummaryofthetestofhypotheses.

Discussion

Theperceptionsofusefulnessandeaseofusehadagenerally positiveinfluenceontheuseofgovernmentwebsites,whatisin linewithotherstudies(e.g.,Carter&Bélanger,2005;Dimitrova &Chen,2006;Weerakkodyetal.,2013).Perceivedusefulness wassignificantonlyduringthestageofadoption(firstquartile), thatis,whentheindividualhasafirstcontactwiththetechnology (Venkatesh et al., 2003),whereas perceived ease of use was significantatmoderateandhighlevelsofuse(themedian,and thethirdquartile),thatis,whentheindividualhasalreadyformed his/herviewaboutusefulness.

Theusefulnessofe-govservicesisassociatedwiththeir effi-ciencyandeffectiveness,inparticularforfightingcorruptionand makinggovernmentactions moretransparent (Avgerouetal., 2009).Governmentmustinvestintheperceptionofusefulness mainly amongpeople who do not use government websites, sinceitisduringtheadoptionstagethatthebenefitsof e-gov shouldbe promotedinordertomotivatepeopletoengage in e-gov(Shareefetal., 2011;Weerakkodyet al.,2013).Atthe sametime,governmentwebsitesshouldaddresseaseofuseby identifyingtherealneedsofthepeople.Itwouldnotbe effec-tivetoallowpeopletoaccessandpaybillsthroughawebsite (usefulness)iftheprocessisnotuserfriendly(easeofuse). Inter-facedesign,loganalysisofe-govservices,anddevelopinguser guidesareactionstowardthatend.

Trust in governmenthad a fully positive influenceon the useofgovernmentwebsites.Thepoliticalandsocial environ-mentshouldbeaddressedinordertounderstandtherelationship betweenpeopleande-gov,giventhatcognitionandemotionsare keyinthisregard(Avgerouetal.,2009),suchasinthecaseof developingtrustworthiness.In ourdataset,we foundlow val-uesforthedescriptivemeasuresinthetwodimensionsofthis construct.Sincetransparentandtrustfulelectronicinteractions

with thegovernment enhancethe trustandthe acceptanceof e-gov(Carter&Weerakkody,2008),wemayconcludethatthe oppositeisalsotrueandthatthepoliticalcontextinBrazildoes nothelpthecitizenstodevelopamorepositiverelationshipwith e-gov.

In Brazil, and particularlyin its Northeastern Region, the mainreasonsforpeoplenottoengageine-govarethe prefer-enceforpersonalcontactsandtheconcernsaboutdatasecurity (CETIC.br,2013).Improvingthetrustingovernmentwebsites is critical; otherwise, people will resort to more traditional means – like the telephone and personal visits to govern-ment offices – inorderto access the government(Srivastava & Teo,2009; Teo etal., 2008).Actions toward transforming e-gov into a more instinctive and desirable means for citi-zenstoexchangewithgovernmentclearlyincludehearingfrom people what they demand from e-gov and taking the corre-spondingactionsofinstitutionalcommitmentandeffectiveness (Srivastava&Teo,2009).Although specificinstancesof gov-ernment will not change on their own the broader political andsocialsetting,trustworthinessbythecitizenswill tendto improve.

Civic engagement had a positive influence on the use of governmentwebsitesduringtheinitialstagesofadoption(first quartile)andathighlevels of use(thirdquartile). Apossible explanationforthisisthat,atthelowlevelsofuse,peoplewho reportengagementincivicactivitiesaremorelikelytointeract withgovernmentbymultiplemeans(Dimitrova&Chen,2006), althoughtheyarestillnotengagedenough;andatthehigh lev-elsofuse,peoplearenaturallyengagedine-govaspartoftheir civicattitudes.

In summary, when developing government websites, one shouldconsiderthepresenceofinformation,servicesand inter-actionforthebenefitofcivicengagement;and,fortheparticular caseofBrazil,keepinmindthatthecontextisuniquein chal-lengesduetoitssocietybeinglethargic(DePinho,2011).The greatestinvestmentatthismomentshouldbetargetedat promot-ingusefulness,easeofuse,andtrustworthinessofgovernment websitesthroughthemobilizationofpeopleinlocalandvirtual forumsinsuchawaythatthecitizensassumetheirincumbency for theirowndevelopmentandthedevelopmentoftheir com-munities–andassuch,theyarelikelytodevelopperceptionsof howe-govmayhelptheminthisintentandpressgovernment todoitspart.

Conclusions

Our study emphasizesthe need of addressing the demand sideofe-gov.AlthoughmanypublicservicesinBrazilarebeing transferredtotheonlineplatforms,thusimposingthecitizensto makeuseofthemregardlessofpersonalpreferencesorabilities, otherservicesarestillofvoluntaryuse–andassuchtheywill beeffectiveonlyifthecitizensareabletorealizetheirbenefits andincorporatethemaspartofahealthypoliticallife.Among otherbenefits,e-govmayimprovetheefficiencyofthepublic sectorinmanywaysandultimatelyaddresspeople’sconcerns moreeffectively–andsavepublicmoney.Therefore,itisforthe bestinterestsofthecitizensthemselvestoleveragethebenefits thatmaystemfrome-govtoolsandpractices.

An important concern is to improve the citizens’ trust in the public agents. However, the current moment in Brazilis notfavorabletowardthatend.Besidesthelong-timeviewthat citizenshaveaboutpoliticiansandthegeneralpolitical environ-ment,currentlythecountryfacesanunprecedentedfightagainst corruptionpractices thatseemtobeendemictothe Brazilian publicandprivatesectors.Althoughthecountryisexpectedto improveitslegislationandpracticesduringandafterthis pro-cess,thecitizensareincreasinglyskepticaboutthepublicagents, whatinturnharmstheneededtrustingovernmentthatwould otherwiseleveragee-govvoluntaryuse.

Althoughwe tookactionstopreventbiasesindata collec-tion,somelimitationsofourstudystemfromoursample.We resortedtothe biometric electoral registrationoffices inJoão Pessoa,amajorcityinBrazil,inordertocollectourdatafrom thecitizenswhovoluntarilyheadedtothoseofficesinorderto updatetheirvotingprofilesforthenextvotingperiod.Wealso tookactionstoenableeveryonetoanswerourquestionsinthose places.Nevertheless,sincetherewasstillplentyoftimeatthat momentforallprospectivevoterstoupdatetheirvotingprofiles untilthestateddeadline,mostintervieweesmayberepresented bytwodominantstrata:thosewhohadvestedinterestsinthe upcomingvotingperiod,andthosewhohadahigherregardto broadercitizenship.Thisimpedesus toclaimthatoursample isfullyrepresentativeofthatcity.Extendingthefindingstothe generalBrazilianpopulationisalsonotpossible,mostlybecause theBrazilianregionsdifferinimportantaspects.

Another limitation concerns the use of self-reported psy-chometricmeasuresandtheinterviewees’interpretationofand interestsonwhatismeasured.Itseemsthatproblemsoccurred inthissenseparticularlywhenmeasuringsomeaspectsofcivic mindedness,giventhatagreatdealofanswersconvergedtoa singlepoint–theperceptionofwhatisexpectedfromcitizens, notwhattheymaybeactuallydoing.Also,theBrazilianpublic servicesarestillinlackofmoreonlinetoolsandpractices,sothe citizensmaynothavearealisticviewofwhatisreallypossible todo inordertoenhancetheirown politicalrolethrough the onlinemeans.Iftheneededimprovementsarenoteffected,the citizens’preferenceforpersonalcontactwiththepublicagents willcontinuetodominateandpostponetherealizationofe-gov benefits.

Conflictsofinterest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

Almeida,A.C.(2007).Acabe¸cadobrasileiro.RiodeJaneiro,Brazil:Record. Avgerou,C.,Ganzaroli,A.,Poulymenakou,A.,&Reinhard,N.(2009). Inter-pretingthetrustworthinessofgovernmentmediatedbyinformationand communicationtechnology:LessonsfromelectronicvotinginBrazil. Infor-mationTechnologyforDevelopment,15(2),133–148.

AtlasBrasil.(2015).AtlasdodesenvolvimentohumanonoBrasil..Retrieved fromhttp://www.atlasbrasil.org.br/2013/pt/

Bannister,F.,&Connolly,R.(2011).Trustandtransformationalgovernment: Aproposedframeworkforresearch.GovernmentInformationQuarterly, 28(2),137–147.

Belanche,D.,Casaló,L.V.,&Flavián,C.(2012).Integratingtrustandpersonal valuesintothetechnologyacceptancemodel:Thecaseofe-government ser-vicesadoption.CuadernosdeEconomíayDireccióndelaEmpresa,15(4), 192–204.

Bellini,C.G.P.,Giebelen,E.,&Casali,R.R.B.(2010).Limitac¸õesdigitais. Informa¸cão&Sociedade:Estudos,20(2),25–35.

Bellini,C.G.P.,IsoniFilho,M.M.,DeMoura,P.J.,Jr.,&Pereira,R.C.F. (2016).Self-efficacyandanxietyofdigitalnativesinfaceofcompulsory computer-mediatedtasks:Astudyaboutdigitalcapabilitiesandlimitations. ComputersinHumanBehavior,59(1),49–57.

Bellini,C.G.P.,IsoniFilho,M.M.,Garcia,D.A.,&Pereira,R.C.F.(2012). Limitac¸õesdigitais:Evidênciasteóricaspreliminares.Análise,23(1),58–70. Benbasat,I.,&Barki,H.(2007).Quovadis,TAM?JournaloftheAIS,8(4),

211–218.

Brown,D.(2005).Electronicgovernmentandpublicadministration. Interna-tionalReviewofAdministrativeSciences,71(2),241–254.

Buchinsky,M.(1998).Recentadvancesinquantileregressionmodels:A prac-ticalguidelineforempiricalresearch.TheJournalofHumanResources, 33(1),88–126.

Carter,L.(2008).E-governmentdiffusion:Acomparisonofadoptionconstructs. TransformingGovernment:People,Process&Policy,2(3),147–161. Carter,L.,etal.(2011).Theroleofsecurityandtrustintheadoptionofonlinetax

filing.TransformingGovernment:People,Process&Policy,5(4),303–318. Carter,L.,&Bélanger,F.(2005).Theutilizationofe-governmentservices: Cit-izentrust,innovationandacceptancefactors.InformationSystemsJournal, 15(1),5–25.

Carter,L.,&Weerakkody,V.(2008).E-governmentadoption:Acultural com-parison.InformationSystemsFrontiers,10(4),473–482.

CETIC.br.(2013).Pesquisasobreousodastecnologiasdainforma¸cãoe comu-nica¸cãonoBrasil2012:TICdomicílioseTICempresas.SãoPaulo,Brazil: ComitêGestordaInternetnoBrasil.

Costa,L.A.,deOliveira,P.C.,Dandolini,G.A.,&deSouza,J.A.(2014). Adoc¸ãodetecnologiasdeservic¸osdegovernoeletrônico:Análisedeestudos quantitativosnoâmbitointernacional.LiincemRevista,10(1),398–414. Damian,I.P.M.,&Merlo,E.M.(2013).Umaanálisedossitesdegovernos

eletrônicosnoBrasilsobaóticadosusuáriosdosservic¸osesuasatisfac¸ão. RevistadeAdministra¸cãoPública,47(4),877–900.

Davis,F.D.(1989).Perceivedusefulness,perceivedeaseofuse,anduser accep-tanceofinformationtechnology.MISQuarterly,13(3),319–340. DeAbreu,J.C.A.,&DePinho,J.A.G.(2014).Sentidosesignificadosda

participac¸ãodemocráticaatravésdaInternet:Umaanálisedaexperiênciado orc¸amentoparticipativodigital.RevistadeAdministra¸cãoPública,48(4), 821–846.

DeAraujo,M.H.(2013).Análisedefatoresqueinfluenciamousodeservi¸cosde governoeletrôniconoBrasil.Disserta¸cãodemestrado.SãoPaulo,Brazil: UniversidadedeSãoPaulo.

DePinho,J.A.G.(2008).Investigandoportaisdegovernoeletrônicodeestados noBrasil:Muitatecnologia,poucademocracia.RevistadeAdministra¸cão Pública,42(3),471–495.

DePinho,J.A.G.(2011).Sociedadedainformac¸ão,capitalismoesociedade civil:Reflexõessobrepolítica,Internetedemocracianarealidadebrasileira. RevistadeAdministra¸cãodeEmpresas,51(1),98–106.

Farina,C.R.,etal.(2013).Regulationroom:Gettingmore,bettercivic partic-ipationincomplexgovernmentpolicymaking.TransformingGovernment: People,Process&Policy,7(4),501–516.

Hair,J.F.,Black,W.C.,Babin,B.J.,Anderson,R.E.,&Tatham,R.L.(2005). Multivariatedata analysis(6th ed.).UpperSaddleRiver: Prentice-Hall International.

Haller,M.,Li,M.-H.,&Mossberger,K.(2011).Doese-governmentuse con-tribute to citizen engagementwith government and community? APSA 2011AnnualMeeting.Rochester,NY:SocialScienceResearchNetwork. Retrievedfromhttp://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1901903

Hechter,M.,Kim,H.,&Baer,J.(2005).Predictionversusexplanationinthe measurementofvalues.EuropeanSociologicalReview,21(2),91–108. Helbig,N.,Gil-García,J.R.,&Ferro,E.(2009).Understandingthecomplexity

ofelectronicgovernment:Implicationsfromthedigitaldivideliterature. GovernmentInformationQuarterly,26(1),89–97.

Hung,S.-Y.,Chang,C.-M.,&Yu,T.-J.(2006).Determinantsofuseracceptance ofthee-governmentservices:Thecaseofonlinetaxfilingandpayment system.GovernmentInformationQuarterly,23(1),97–122.

Kam,P.-K.,etal.(1999).Mobilizedorcivicmindedfactorsaffectingthepolitical participationofseniorcitizens.ResearchonAging,21(5),627–656. IBGE. (2015a). Censo demográfico 2010.. Retrieved from http://www.

censo2010.ibge.gov.br

IBGE. (2015b). Cidades@.. Retrieved from http://cidades.ibge.gov.br/ xtras/perfil.php?codmun=250750

Kang,S.,&Gearhart,S.(2010).E-governmentandcivicengagement:Howis citizens’useofcitywebsitesrelatedwithcivicinvolvementandpolitical behaviors?JournalofBroadcasting&ElectronicMedia,54(3),443–462. Kolsaker,A.,&Lee-Kelley,L.(2008).Citizens’attitudestowardse-government

ande-governance:AUKstudy.InternationalJournalofPublicSector Man-agement,21(7),723–738.

Lee,Y.,Kozar,K.A.,&Larsen,K.R.T.(2003).Thetechnologyacceptance model:Past,present,andfuture.CommunicationsoftheAIS,12(1),752–780. Lee,M.K.O.,& Turban,E.(2001).Atrust modelforconsumerInternet

shopping.InternationalJournalofElectronicCommerce,6(1),75–91. Lim,E.T.K.,etal.(2011).Advancingpublictrustrelationshipsinelectronic

government:TheSingaporee-filingjourney.InformationSystemsResearch, 23(4),1110–1130.

Morgeson,F.V.I.,Vanamburg,D.,&Mithas,S.(2011).Misplacedtrust? Explor-ingthestructureofthee-government-citizentrustrelationship.Journalof PublicAdministrationResearch&Theory,21(2),257–283.

PNUD–ProgramadasNac¸õesUnidasparaoDesenvolvimento.(2015). Rank-ingIDHMmunicípios2010..Retrievedfromhttp://www.pnud.org.br/atlas/ ranking/Ranking-IDHM-Municipios-2010.aspx

Rana,N.P., etal.(2011).Reflecting one-governmentresearch: Towarda taxonomyoftheoriesandtheoreticalconstructs.InternationalJournalof ElectronicGovernmentResearch,7(4),64–88.

Rana, N. P., Dwivedi, Y. K., & Williams, M. D. (2013a). Evaluating alternativetheoreticalmodelsforexaminingcitizencentricadoptionof e-government.TransformingGovernment:People,Process &Policy,7(1), 27–49.

Rana,N.P.,Dwivedi,Y.K.,&Williams,M.D.(2013b).Ameta-analysisof existingresearchoncitizenadoptionofe-government.InformationSystems Frontiers,17(3),547–563.

Reddick,C.G.(2005).Citizeninteractionwithe-government:Fromthestreets toservers?GovernmentInformationQuarterly,22(1),38–57.

Rossiter,J.R.,&Braithwaite,B.(2013).C-OAR-SE-basedsingle-itemmeasures forthetwo-stagetechnologyacceptance model.AustralasianMarketing Journal,21(1),30–35.

Sandoval-Almazan,R.,&Gil-Garcia,J.R.(2012).AregovernmentInternet portalsevolvingtowardsmoreinteraction,participation,andcollaboration? Revisitingtherhetoricofe-governmentamongmunicipalities.Government InformationQuarterly,29(1),S72–S81.

Schaupp, L. C., & Carter, L. (2010). Theimpact of trust, risk and opti-mism bias on e-file adoption. Information Systems Frontiers, 12(3), 299–309.

Shareef, M. A.,etal.(2011).E-government adoptionmodel(GAM): Dif-feringservicematuritylevels.GovernmentInformationQuarterly,28(1), 17–35.

Smith, M. L. (2011). Limitations to building institutional trustworthiness through e-government:Acomparativestudyoftwoe-servicesinChile. JournalofInformationTechnology,26(1),78–93.

Srivastava,S.,&Teo,T.(2009).Citizentrustdevelopmentfore-government adoptionandusage:InsightsfromyoungadultsinSingapore. Communica-tionsoftheAIS,25.

Streib,G.,&Navarro,I.(2006).Citizendemandforinteractivee-government: ThecaseofGeorgiaconsumerservices.TheAmericanReviewofPublic Administration,36(3),288–300.

Teo,T.S.H.,Srivastava,S.C.,&Jiang,L.(2008).Trustandelectronic gov-ernmentsuccess:Anempiricalstudy.JournalofManagementInformation Systems,25(3),99–132.

Venkatesh, V., et al. (2003). User acceptance of information technology: Towardaunifiedview.ManagementInformationSystemsQuarterly,27(3), 425–478.

Weerakkody,V.,etal.(2013).Examiningtheinfluenceofintermediariesin facil-itatinge-governmentadoption:Anempiricalinvestigation.International JournalofInformationManagement,33(5),716–725.

Welch,E.W.(2004).Linkingcitizensatisfactionwithe-governmentandtrust ingovernment.JournalofPublicAdministrationResearch&Theory,15(3), 371–391.