REVISTA

BRASILEIRA

DE

ANESTESIOLOGIA

OfficialPublicationoftheBrazilianSocietyofAnesthesiologywww.sba.com.br

MISCELLANEOUS

Do

the

severity

and

the

body

region

of

injury

correlate

with

long-term

outcome

in

the

severe

traumatic

patient?

Maylin

Koo

∗,

Israel

Otero,

Antoni

Sabaté,

Ruben

Martínez,

Augusto

Mauro,

Pilar

García,

Silvia

López

BellvitgeBiomedicalResearchInstitute,L’HospitaldeLlobregat,Spain

Received16August2012;accepted20March2013 Availableonline8October2013

KEYWORDS

Injuryseverityscore;

Abbreviatedinjury

score;

ShortForm-12;

HealthAssessment

Questionnaire; Outcome; Trauma

Abstract

Backgroundandobjectives: ToinvestigateiftheInjurySeverityScore(ISS)andtheAbbreviated InjuryScore(AIS)arecorrelatedwiththelong-termqualityoflifeinseveretraumapatients.

Methods:Patientsinjuredfrom2005to2007withanISS≥ 15weresurveyed16---24monthsafter injury.TheHealthAssessmentQuestionnaire(HAQ-DI)wasusedformeasuringthefunctional statusandtheShortForm-12(SF-12) wasusedfor measuringthehealth statusdividedinto itstwocomponents,thePCS(PhysicalComponentSummary)andtheMCS(MentalComponent Summary).TheresultsofthequestionnaireswerecomparedwiththeISSandAIScomponents. ResultsoftheSF-12werecomparedwiththevaluesexpectedfromthegeneralpopulation.

Results:Seventy-fourpatientsfilledthequestionnaires(responserate28%).Themeanscores were:PCS42.6± 13.3;MCS49.4± 1.4;HAQ-DI0.5± 0.7.Correlationwas observedwiththe HAQ-DIandthePCS(Spearman’sRho:−0.83;p<0.05)andnocorrelationbetweentheHAQ-DI andtheMCSneitherbetweentheMCSandPCS(Spearman’sRho=−0.21;and0.01respectively). Thecutaneous-externalandextremities-pelvicAISpunctuationwerecorrelatedwithThePCS (Spearman’sRho:−0.39and−0.34,p<0.05)andwiththeHAQ-DI(Spearman’sRho:0.31and 0.23;p<0.05).Thephysicalconditioncomparedwiththeregularpopulationwasworseexcept forthegroupsagedbetween65---74and55---64.

Conclusions:Patientswithextremitiesandpelvicfracturesaremorelikelytosufferlong-term disability.Theseverityoftheexternalinjuriesinfluencedthelong-termdisability.

©2013SociedadeBrasileiradeAnestesiologia.PublishedbyElsevier EditoraLtda.Allrights reserved.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:mkoo@bellvitgehospital.cat(M.Koo).

Introduction

In 1976 the American College of Surgeons Committee on

Trauma categorized hospitals in Trauma-Centers; in

con-sequence since then a decrease of mortality has been

recognized.1However,other questionsarousedsuchasthe

long-term quality of life and outcome improvement of

traumapatients.2

In1999aninternationalconsensusconferenceremarked

theheterogeneityoftheavailableinstrumentsforthe

mea-surementofthequalityoflife.3,4 Severaltools havebeen

used:theShortForm-36questionnaire(SF-36)andtheShort

Form-12questionnaire(SF-12),theGlasgowOutcomeScale,

theFunctionalIndependenceMeasure,theQualityof

Well-beingScale, theHannover Score for Polytrauma Outcome

andtheEuroQOL-5D.2,5---7Each oneof themhasits

advan-tages and limitations, but none of them measure all the

dimensions that involve health status in trauma patients.

Aquestionnaireshouldsatisfythefollowingrequirements:

understandable,briefnessonitsaccomplishmentand

anal-ysis, validation in different languages, being of public

domain,lowcostuseandvalidatedforautoadministration

via e-mailor regularmailandbypersonalor phone

inter-view.Inaddition,itshouldhaveaworldwidediffusiontobe

abletoestablish comparisonsbetweendifferentgroupsof

patients indifferent countries.Basedonthese

character-isticsthereare twoquestionnaireswhich have been used

frequently:theHealthAssessmentQuestionnaire-Disability

Index(HAQ-DI)andtheSF-12.

The HAQ-DI questionnaire was initially used for

assessing rheumatic diseases,8,9 and afterwards

subse-quently extended to any kind of condition.10 The HAQ-DI

canberealizedinlessthan5min;ithasbeentranslatedto

morethan60differentlanguagesandvalidatedforitsuse

bytelephone.TheSF-12questionnaireisalsovalidatedto

beadministeredbytelephoneanditneedsonly2mintobe

finished.Itwasinitiallydesignedtorepresentthesummary

componentsoftheSF-36witha90%ofprecision,which

com-pletelyovercame11andithasbeenusedintheevaluationof

patientswhosuffered multipletrauma, pelvictraumatism

orworkplaceinjuries.12---16

Recent guidelines have been published by the

Euro-pean Consumer Safety Association17 grading the disability

of trauma patients, in base on a systematic review and

expert’sopinion.Fourdifferentassessingpointshavebeen

described:theacutephasewithinthefirstmonth;the

reha-bilitationphase,till2months;theadaptationphase,atthe

fourthmonth,andtherecoveryphase,upto6months.

Thehealthandqualityoflifeafterdischargehavebeen

associated to age, sex, comorbidity, the severity of the

traumatism and thelength of stay at the hospital.6,7,18---20

The severity of the traumatism is stratified according to

the Injury Severity Score index (ISS) which correlates to

mortality.21TheISSisananatomicalscoringsystembasedon

theAbbreviatedInjuryScale(AIS)thatgraduatesthe

sever-ityofthe injuriesin differentanatomicalregions.22 When

theISSis greaterthan 15asevere traumapatientcan be

predicted.23

Theaimofourstudywastodetermineifthelong-term

healthstatusofseveretrauma,measuredbytheHAQ-DIand

theSF-12correlatewiththeextendedinjuriesmeasuredby

theISS.

Methods

AfterHospitalEthicsCommitteeapproval,adatabasewas

created. All trauma patients who were attended in our

traumacenterdue toablunt orpenetrating injurywithin

theyears2005---2007were included.Patientswhohadan

ISS≥15,withan age ≥18 yearsandwhowere discharged

from the hospital were followed up. The data collected

werethedemographiccharacteristicsofpatients,thetype

ofinjury,theISS,andtheAIS.

The HAQ-DI questions were grouped into 8 categories

(dressing,rising,eating,walking,hygiene, reach,gripand

usual activities), each category was scored from 0 to 3

(0:without anydifficulty;1: withsome difficulty;2: with

much difficulty; 3: unable to do); afterwards the

aver-age of the 8 categories wasmade to obtain the score of

thequestionnaire. In case of the patient needing help or

using special devices on any of the categories a

correc-tion factor was applied. At least 6 of the 8 categories

must be answered or the questionnaire cannot be

com-puted. Scores were classified as 0 meaning no disability,

0---1milddisability,1---2moderatedisabilityand2---3severe

disability.8,9

TheSF-12included8categories(physicalfunction,

phys-icalrole, emotional role, social function, mental health,

generalhealth,bodypainandvitality).Thenumericalscore

obtainedineachcategorywascalculatedbythesumofthe

items,andconvertedtoascalefrom0(worstscore)to100

(bestscore).11Theresultsweredividedintotwomain

com-ponents,thePhysicalComponentSummaryandtheMental

Component Summary both validated in the Americanand

theSpanishpopulation,obtainingsimilarsummary

compo-nentweightsforbothpopulations.24Therearetwowaysof

estimating the summary components: the standard which

referstodatafromUSA, andthe specific where thedata

usedreferstoeach countryin particular; we selectedde

standardformasitisrecommendedforinternational

publi-cations.Summarycomponentswerecreatedreflectingthe

standard deviation from the average with a value of 50.

It wasconsidered a normal health status ifthe values of

thesummarycomponentswerebetween40and60;limited

healthstatusifthevalueswerebelow40;andgoodhealth

statusifthevalueswereabove60.

The results obtained with the SF-12 were compared

withthose expected from the general population,

strati-fiedaccordingtoage.Thepoweroftheeffectsizeofeach

populationwascalculated.

Thequestionnaireswereperformed16---24months

post-injury,by trained personnel via telephone; ifthe patient

didnotanswerthephoneatthefirstcall,threeextracalls

weremadeinmorning,afternoonandeveningtimes.Losses

infollowupwereconsideredifitwasnotpossibletogetin

touchwiththepatientorthepatientdidnotwanttoanswer

thesurveys.

The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS

WIN15.0package.WeusedtheChi-squaretest(Yates

cor-rectionandFisherexact test) tocompare theproportions

ofrespondersandnon-responders. TheKruskal---Walliswas

used to compare the categorized scores of the different

questionnaires. The Spearman test was used to compare

therelationshipbetweenqualityoflifewiththeISSandthe

AIScomponents.The effectsizewasusedtocomparethe

scoresofthe responderswiththatof thereference

popu-lation.Dataareshownasmeanandstandard deviationor

medianandrangewhenindicated.Avalueofp≤0.05was

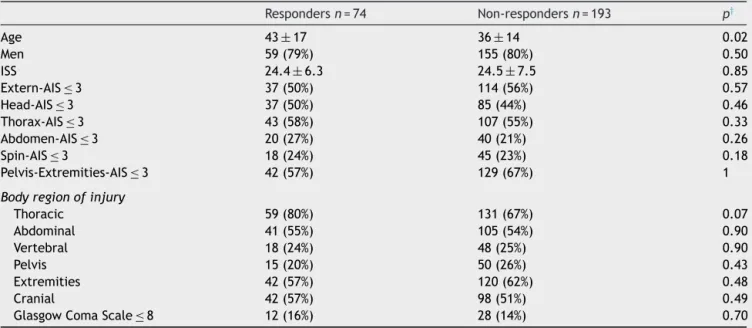

Table1 ComparisonofdemographiccharacteristicsandAISvaluesbetweenrespondersandnon-responderstothesurveys.

Respondersn=74 Non-respondersn=193 p†

Age 43±17 36±14 0.02

Men 59(79%) 155(80%) 0.50

ISS 24.4±6.3 24.5±7.5 0.85

Extern-AIS≤3 37(50%) 114(56%) 0.57

Head-AIS≤3 37(50%) 85(44%) 0.46

Thorax-AIS≤3 43(58%) 107(55%) 0.33

Abdomen-AIS≤3 20(27%) 40(21%) 0.26

Spin-AIS≤3 18(24%) 45(23%) 0.18

Pelvis-Extremities-AIS≤3 42(57%) 129(67%) 1

Bodyregionofinjury

Thoracic 59(80%) 131(67%) 0.07

Abdominal 41(55%) 105(54%) 0.90

Vertebral 18(24%) 48(25%) 0.90

Pelvis 15(20%) 50(26%) 0.43

Extremities 42(57%) 120(62%) 0.48

Cranial 42(57%) 98(51%) 0.49

GlasgowComaScale≤8 12(16%) 28(14%) 0.70

ISS,InjurySeverityScore;AIS,AbreviatedInjuryScale. † Statistic

2;dataexpressedasmean±standarddeviation,absolutevaluesand(percentage).

Results

A total of 267 patients with an ISS≥15 were discharged

from the hospital. In 160 cases there were no answers

becauseoferroneoustelephonenumberormorethanthree

callswithout response;24 patients refusedtoanswer the

questionnaires; in 5 cases there were an idiomatic

bar-rier; in 2 cases the patient had passed away and in 2

casesthemedicalconditionmadeimpossibleansweringthe

questionnaires.A total of 74 patients filledthe

question-naires.

Comparingthepatientswhoansweredthequestionnaires

withthosewhodidnot,thenon-responderpopulationwere

younger(36±14vs.43±17; p=0.02).Therewereno

dif-ferencesin thedemographicdata,theinjuredanatomical

regionsandintheAISregistered(Table1).

Themedianscoresandrangeswere46(11.8---60.9)forthe

PhysicalComponentSummary;51(12.9---74.2)fortheMental

ComponentSummary,and0.12(0---3)fortheHAQ-DI.

The ISS values were comparablefor thedifferent

cat-egories of the HAQ-DI and for the physical and mental

summarycomponentsoftheSF-12(Table2).

We obtained a negativecorrelation between the

HAQ-DI and the physical component of the SF-12 (Spearman’s

Rho=−0.83;p=0.000)andnocorrelationbetweenthe

HAQ-DI and the mental component of the SF-12 (Spearman’s

Rho=−0.21; p=0.07), neither between the mental and

physical componentsof the SF-12(Spearman’sRho=0.01;

p=0.9).

Analyzing the AIS components of the ISS (Table 3) we

found a significant negative-correlation between the PCS

andthe cutaneous-externalscore of theAIS andwiththe

extremities-pelvicscore.Likewise,wefoundpositive

signif-icantcorrelationofthesetwoscoreswiththeHAQ-DI;and

apositivecorrelationbetweenthePCSandthe

abdominal-pelviccontentsscoreoftheAIS.Therewasalsoacorrelation

betweentheAbdomenAISandthepelvicextremities

(Spear-man’sRho=−0.35;p=0.002).

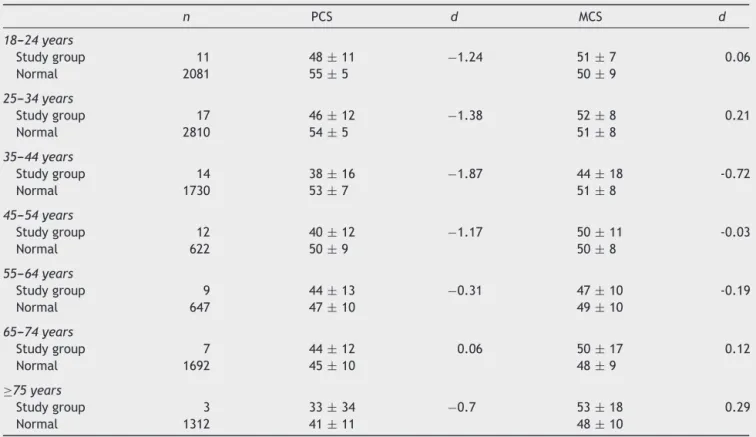

Whencomparingthephysicalandmentalhealthstatusof

ourtraumapatientswiththenormalvaluesofpopulation,

weobservedthatthephysicalconditionwasgloballyworse

inallageintervals,exceptinpatientsagedbetween55---64

and65---74,wheretheeffectsizewassmaller.Regardingto

thementalhealthstatus,thevaluesobtainedshowedamild

differenceintheintervalbetween35and44years,where

thementalhealthstatuswaslowerthanthenorm(Table4).

Table2 RelationbetweenlevelsoftheHealthAssessment Questionnaire,thePhysicalComponentSummaryofthe SF-12 andthe MentalComponentSummaryoftheSF-12with theISS(injuryseveritystore).

n ISS Pa HAQ-DI

Nodisability 36 26.5(16---45)

Milddisability 21 21(16---38) 0.22 Moderatedisability 12 23(17---34)

Severedisability 5 22(17---34)

PCS

GoodHealthStatus 3 16(16---26) 0.15 NormalHealthStatus 42 26(16---45)

LimitedHealthStatus 29 22(17---34)

MCS

GoodHealthStatus 12 21.5(17---29)

NormalHealthStatus 50 25(16---45) 0.68 LimitedHealthStatus 12 24(16---34)

HAQ-DI,HealthAssessmentQuestionnaire;PCS,Physical Compo-nentSummaryoftheSF-12;MCS,MentalComponentSummary oftheSF-12.

Dataexpressedasmedianandrange.

Table3 CorrelationbetweentheHealthAssessment Ques-tionnaire, the Physical Component Summary of the SF-12 andtheMentalComponentSummaryoftheSF-12withthe AbbreviatedInjuryScorecomponents.

PCSa MCSa HAQa

ISS 0.06 −0.09 −0.13

AIS-External −0.39* 0.01 0.31*

AIS-Head 0.09 −0.05 −0.05 AIS-Thorax 0.06 −0.12 −0.14 AIS-Abdomen 0.28* −0.54 −0.20

AIS-Spine −0.17 −0.05 0.12 AIS-Pelvis-Extr −0.34* 0.09 0.23*

PCS --- 0.01 −0.83*

MCS 0.01 --- −0.21

ISS,InjurySeverityScore;AIS-Pelvis-Ext,ExtremitiesandBony pelvis;AIS-Abdomen,Abdomenandpelviccontents;PCS, Physi-calComponentSummaryoftheSF-12;MCS,MentalComponent Summary ofthe SF-12; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Question-naire.

a RhoofSpearmanCorrelation. * p≤0.05.

Discussion

After the application of the HAQ-DIand the SF-12to our

patients, we obtained values in the lower health status

range,with worse valuesin the physical component than

in the mental component. We evaluated the health

sta-tus 16---24 months post-injury; therefore the low values

obtainedweremeasuredafteralong periodof

rehabilita-tion.Themeasureofthelong-termqualityoflifeintrauma

patients should be considered when a complete

rehabili-tationisachieved.According tosomeauthors17,25 after12

monthsfrominjury a highpercentage of patientsshowed

afull recovery of their lesions.However, it is considered

bettertoevaluatethehealth statusafter24monthsfrom

thetraumatism,inordertoassureastablesituationofthe

disabilities.2,19

We couldnotobserveany relation betweenthe health

status and the ISS values. The ISS is based on

anatomi-calinjuries;for thisreasonanassociation tohealthstatus

can be expected. Nevertheless, the results of our study

were in accordance with the results published by other

authors.12,13,18,26However,someassociationbetweentheISS

andthephysicalcomponentofthelong-termhealthstatus14

andwiththeglobalqualityoflifeevaluated2---7yearsafter

thetraumatism,7hasbeen observed,aswellasarelation

oftheISSwiththephysicalcomponentofthequalityoflife

measuredimmediatelyaftertheinjury.13 Theglobal

inter-pretationofoppositepapersisdifficultandresultsarenot

comparable because of the different questionnaires used

andthedifferenttimeofmeasurement.

Wefoundasignificantcorrelationbetweenthelong-term

qualityoflifemeasuredtwicethroughthePhysical

Compo-nentSummaryandtheHAQ-DIwiththecutaneous-external

component and the extremities-pelvic ring component of

theISS.Therewasnorelationofthesetwocomponentswith

Table4 EvaluationoftheeffectsizeofthestudygroupwiththenormalpopulationmeasuredbytheSF-12.

n PCS d MCS d

18---24years

Studygroup 11 48± 11 −1.24 51± 7 0.06

Normal 2081 55±5 50±9

25---34years

Studygroup 17 46± 12 −1.38 52± 8 0.21

Normal 2810 54±5 51±8

35---44years

Studygroup 14 38±16 −1.87 44±18 -0.72

Normal 1730 53± 7 51± 8

45---54years

Studygroup 12 40±12 −1.17 50±11 -0.03

Normal 622 50± 9 50± 8

55---64years

Studygroup 9 44± 13 −0.31 47± 10 -0.19

Normal 647 47±10 49±10

65---74years

Studygroup 7 44± 12 0.06 50± 17 0.12

Normal 1692 45±10 48±9

≥75years

Studygroup 3 33± 34 −0.7 53± 18 0.29

Normal 1312 41± 11 48± 10

PCS,PhysicalComponentSummaryoftheSF-12;MCS,MentalComponentSummaryoftheSF-12;d,effectsizeofCohen(d=0.20---0.3 smalleffect;d=0.50mediumeffect;d≥0.80largeeffect).

theMentalComponent Summary.The associationbetween

pelvicand extremitiesinjuries withthe long-term quality

of life has been described by other authors,12,18,27

never-theless,theassociationwiththecutaneousregionhasnot

been recognized.The correlation of thecutaneous scores

withthelong-term qualityoflife canbe interpretedasa

reflection of theseinjuries by themagnitude of the

frac-turesintheextremities.Similarly,wewereabletoassociate

theAIS punctuations of the abdomen component andthe

pelvicringinjurywhichindicatestheassociationofserious

pelvicfractures withthe presenceof traumatized vessels

andotherintra-abdominalinjuries.Wealsofounda

corre-lationbetweentheabdominalcomponentoftheISSandthe

PhysicalComponentSummary,butnotwiththeHAQ-DI.

The correlation between the HAQ-DI and the Physical

ComponentSummary oftheSF-12; reinforcesthephysical

disabilityinourpatients.TheMentalComponentSummary

valuesofthe SF-12werenotcorrelated withthe physical

disabilitymeasuredbytheHAQ-DI.Thereforeboth

question-nairesaremeasuringdifferentcomponentsofthedisability

andit reinforcesthe importance of usingcomplementary

questionnairesfor measuringthe health status.The

HAQ-DI includes evaluation of precise movements and motor

activities of the upper and lower extremities.8---10,28

Nev-ertheless one of the weak points of this questionnaire is

thatitdoesnotmeasurethedisabilityrelatedtopsychiatric

problems,affectationofsensoryorgans,andsatisfactionof

thepatientorsocialintegration.Thesedeficienciescanbe

complementedwiththeapplication oftheSF-12

question-nairetakinginconsiderationbothsummarycomponents,the

physicallycomponentandthemental.

When comparedthe healthcondition ofourpopulation

withthepopulationstandard norms,weobservedthatthe

PhysicalComponent Summary valueswerelower thanthe

norm,andthisdifferencewashigherinthepopulationunder

54yearswhopresentedaworsephysicalstatus.Polinderet

al.,19 verifiedthat patients,onageunder65,presenteda

worselong-term quality of lifethan the older group,and

thatit wasinfluenced by thepresence of other illnesses.

Livingston et al.5 found a weak correlation of the health

statuswithage,buttheyalsopointedthatthepopulation

above65yearsevaluatedtheirqualityoflifeasbetterand

thismightberelatedtoalessexpectationabouthealththan

theyoungerpopulation.

The low response rate is one of the limitations of our

study,beingthispercentagevariableaccordingtothe

liter-atureandrangingbetween21%and88%.19,29Thisvariability

dependsonthemethodology used,12,14 but normally

long-term outcome studies, like ours, have a low response

rate.Polinder etal.19 at 24monthsfollow-upregistereda

responserateof21%.Inourstudy,wefoundnodifferences

in the trauma characteristics of the respondersand

non-responders, expecting therefore similar outcome in both

populations.

Weconclude,thatdeterminingthelong-termqualityof

life might help to identify those patients in whom there

wouldbenecessarymoreeffortandemphasisinthe

reha-bilitationandadjustmentprocesses;andalsomayhelp to

detectpreventiveapproachesdirectedtodiminishthe

post-traumaticdisability. Inourpopulation,thosewhosuffered

extremitiesand pelvic fracturesare morelikely tosuffer

long-termdisabilityandtheseverityoftheexternalinjuries

are also predictive for long-term disability of traumatic

patients.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.MacKenzieEJ,Rivara FP,Jurkovich GJ,NathensAB, FreyKP, EglestonBL,SalkeverDS,ScharfsteinDO.Anationalevaluation oftheeffectoftrauma-centercareonmortality.NEnglJMed. 2006;354:366---78.

2.Stalp M, Koch C,Ruchholtz S, et al. Standardized outcome evaluationafterbluntmultipleinjuriesbyscoringsystems:a clinicalfollow-upinvestigation2yearsafterinjury.JTrauma. 2002;52:1160---8.

3.Neugebauera E, Lefering R, Bouillonb B, Bullingerc M, Wood-Dauphineed S. Quality of life after multiple trauma. Aim and Scope of the Conference Restor Neurol Neurosci. 2002;20:87---92.

4.NeugebaueraE,BouillonbB,BullingercM,Wood-DauphineedS. Qualityoflifeaftermultipletrauma----summaryand recommen-dationsoftheconsensusconference.RestorNeurolNeurosci. 2002;20:161---7.

5.LivingstonDH,TrippT,BiggsC,LaveryRF. Afateworsethan death?Long-termoutcomeoftraumapatientsadmittedtothe surgicalintensivecareunit.JTrauma.2009;67:341---9. 6.HolbrookTL,HoytDB,AndersonJP.Theimportanceofgender

on outcome after major trauma: functional and psycho-logic outcomes in women versus men. J Trauma. 2001;50: 270---3.

7.Ulvik A, Kvale R, Wentzel-Larsen T, Flaatten H. Quality of life2---7years aftermajortrauma.Acta AnaesthesiolScand. 2008;52:195---201.

8.BruceB,FriesJF.TheHealthAssessmentQuestionnaire(HAQ). ClinExpRheumatol.2005;23:S14---8.

9.Bruce B, Fries JF. The Stanford Health Assessment Ques-tionnaire:dimensionsand practicalapplications.HealthQual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:20, this article is available from: http://www.hqlo.com/content/1/1/20

10.GillenM, Jewell SA, Faucett JA, Yelin E. Functional limita-tionsandwell-beingininjuredmunicipalworkers:alongitudinal study.JOccupRehab.2004;14:89---105.

11.VilagutG,FerrerM,RajmilL,RebolloP,Permanyer-MiraldaG, QuintanaJM,SantedR,ValderasJM,RiberaA,Domingo-Salvany A,AlonsoJ.TheSpanishversionoftheShortForm36Health Survey:adecadeofexperienceand newdevelopments. Gac Sanit.2005;19:135---50.

12.KielyJM,BraselKJ,WeidnerKL,GuseCE,WeigeltJA. Predict-ingqualityoflifesixmonthsaftertraumaticinjury.JTrauma. 2006;61:791---8.

13.BraselKJ,Roon-CassiniT,Bradley.Injuryseverity andquality oflife: whose perspective is important?J Trauma.2010;68: 263---8.

14.Harris IA, Young JM, Rae H, Jalaludin B, Solomon MJ. Pre-dictors of general health after major trauma. J Trauma. 2008;64:969---74.

15.GillenM, Jewell SA, Faucett JA, Yelin E. Functional limita-tionsandwell-beingininjuredmunicipalworkers:alongitudinal study.JOccupRehabil.2004;14:89---105.

16.TottermanA, GlottT, SøbergHL,Madsen JE,Røise O.Pelvic traumawithdisplacedsacralfracturesfunctionaloutcomeat oneyear.Spine.2007;3:1437---43.

studies measuring injury-related disability. J Trauma. 2007;62:534---50.

18.HoltslagHR,PostMW,LindemanE,VanderWerkenC.Long-term functional health statusof severely injuredpatients. Injury. 2007;38:280---9.

19.PolinderP,VanBeeckF,Essink-Bot MK,ToetH, LoomanCW, Mulder S, Meerding WJ. Functional outcome at 2.5, 5, 9, and 24 months after injury in the Netherlands. J Trauma. 2007;62:133---41.

20.HolbrookTL,HoytDB, AndersonJP.The impactofmajor in-hospitalcomplicationsonfunctionaloutcomeandqualityoflife aftertrauma.JTrauma.2001;50:91---5.

21.GuzzoJL,BochicchioGV,NapolitanoLM,MaloneDL,MeyerW, ScaleaTM.Predictionofoutcomesintrauma:anatomicor phys-iologicparameters?JAmCollSurg.2005;201:891---7.

22.LinnSh. Theinjury severity score-importanceand uses.Ann Epidemiol.1995:440---6.

23.BoydCR, TolsonMA,CopesWS. Evaluatingtrauma care:the TRISSmethod. Traumascore andtheinjury severityscore.J Trauma.1987;27:370---8.

24.VilagutG,ValderasJM,FerreraM,GarinaO,López-GarcíaE, Alonso J. Interpretaciónde los cuestionarios de saludSF-36 y SF-12 en Espa˜na: componentes físico y mental. MedClin. 2008;130:726---35.

25.Currens B. Evaluation of disability and handicap following injury.Injury.2000;31:99---106.

26.Palma JA, Fedorka P, Simko LC. Quality of life experi-encedbyseverelyinjuredtraumasurvivors.AACNClinIssues. 2003;14:54---63.

27.Holbrook TL, Anderson JP, Sieber WJ, Browner D, Hoyt DB. Outcomeaftermajortrauma:dischargeand 6-month follow-up results from the Trauma Recovery Project. J Trauma. 1998;45:315---23.

28.WildnerM,SanghalO,ClarckDE,DöringA,ManstettenA. Inde-pendent livingafterfracturesin theelderly.OsteoporosInt. 2002;13:579---85.