r e v b r a s r e u m a t o l . 2016;56(5):384–390

ww w . r e u m a t o l o g i a . c o m . b r

REVISTA

BRASILEIRA

DE

REUMATOLOGIA

Original

article

A

prospective

study

predicting

the

outcome

of

chronic

low

back

pain

and

physical

therapy:

the

role

of

fear-avoidance

beliefs

and

extraspinal

pain

Aloma

S.A.

Feitosa,

Jaqueline

Barros

Lopes,

Eloisa

Bonfa,

Ari

S.R.

Halpern

∗Servic¸odeReumatologia,HospitaldasClínicas,UniversidadedeSãoPaulo(USP),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory: Received15May2015 Accepted11November2015 Availableonline22March2016

Keywords:

Fear-avoidancebeliefs Extraspinalpain Therapeuticresponse Chroniclowbackpain

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Objective:Toidentifytheprognosticfactorsforconventionalphysicaltherapyinpatients withchroniclowbackpain(CLBP).

Methods:Prospectiveobservationalstudy.

Participants:OnehundredthirteenpatientswithCLBPselectedattheSpinalDisease Outpa-tientClinic.

Mainoutcomemeasures:PainintensitywasscoredusingtheNumericRatingScale(NRS),and functionwasmeasuredusingtheRoland-MorrisDisabilityQuestionnaire(RMDQ). Results:TheFear-AvoidanceBeliefsQuestionnaireworksubscaleresults(FABQ-work;odds ratio[OR]=0.27, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.13–0.56, p<0.001) and extraspinal pain (OR=0.35, 95% CI 0.17–0.74, p=0.006)wereindependently associated witha decreased responsetoconventionalphysicaltherapyforCLBP.

Conclusion:WeidentifiedhighFABQ-workandextraspinalpainscoresaskeydeterminants ofaworseresponsetophysicaltherapyamongCLBPpatients,supportingtheneedfora specialrehabilitationprogramforthissubgroup.

©2016ElsevierEditoraLtda.ThisisanopenaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-ND license(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Estudo

prospectivo

de

fatores

prognósticos

em

lombalgia

crônica

tratados

com

fisioterapia:

papel

do

medo-evitac¸ão

e

dor

extraespinal

Palavras-chave:

Crenc¸asdeevitac¸ãoemedo Dorextraespinal

Respostaterapêutica Lombalgiacrônica

r

e

s

u

m

o

Objetivo:Identificarosfatoresprognósticosparaafisioterapiaconvencionalempacientes comlombalgiamecânicacomumcrônica(LMC).

Métodos:Estudoprospectivoobservacional.

Participantes:Foram selecionados pelo Ambulatório de Doenc¸as da Coluna Vertebral 113pacientescomlombalgiamecânicacomumcrônica.

Medidas de desfecho principais:A intensidade da dor foi pontuada utilizando a Escala NuméricadeDor(END)eafunc¸ãofoimedidausandooQuestionárioRoland-Morrisde Incapacidade(RMDQ).

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:ariradu@einstein.br(A.S.Halpern). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbre.2016.03.002

Resultados: OsresultadosdasubescalatrabalhodoFear-AvoidanceBeliefsQuestionnaire (FABQ-trabalho; odds ratio [OR]=0,27, intervalo de confianc¸a de 95%[IC 95%] 0,13–0,56, p<0,001)edador extraespinal(OR=0,35,IC0,17–0,74, p=0,006)estiveram independen-temente associados a uma diminuic¸ão na respostaà fisioterapia convencional paraa lombalgiacrônica.

Conclusão: ForamidentificadosescoreselevadosnaFABQ-trabalhoedorextraespinalcomo determinantes-chaveparaumapiorrespostaàfisioterapiaempacientescomLMCoque apoiaanecessidadedeumprogramadereabilitac¸ãoespecialparaestesubgrupo.

©2016ElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eumartigoOpenAccesssobumalicenc¸aCC BY-NC-ND(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Chronic lowback pain (CLBP)is oneof the mostcommon causesofmusculoskeletalsystem-relateddisability,anditis associatedwithhighlevelsofhealthcareresourceutilization.1 TheimpactofCLBPinBrazilisthoughttoparallelthe situ-ationintheNorthernhemisphere,althoughaccuratedataare lacking.ThenumberofBrazilianswhoaredisabledbyCLBPis veryhigh;reportsestimatethatapproximately10million peo-pleinBrazilareaffected.2CLBPrepresentsthemainreasonfor disabilitybenefitrequestsandisthethirdmostcommoncause ofdisability-relatedretirementinBrazil.3

Treatment for CLBP is usually conservative. Scientific evidence consistently favors pharmacological agents and rehabilitationastheprimarytreatmentoptions4,5;however, theresponsetophysicaltherapyisrathervariableand unpre-dictable.

Althoughstudieshaveindicatedthe efficacyof rehabili-tationcomparedwithnotreatment,fewhavedemonstrated the superiorityofany particularrehabilitationprogram for CLBP.6–9 Inaddition,relapse ratesafterinitialimprovement from rehabilitationare high,7 whereas the long-term cost-effectivenessofphysicalrehabilitationanditsactualimpact onrecoveryintermsofenablingpatientstoreturntotheir normalactivitiesremainsunknown.8

SincetheQuebecTaskForce’sreportin1987,many inter-nationalguidelineshavebeenpublished.10–14Althoughthese guidelines were produced in different countries, most of theissuesrelatedtotherapeuticinterventionweresimilar.13 Supervisedexercisewas generally recommended, although most guidelines did not propose a specific set of exer-cises.Physicaltherapistsuse abroadarray ofconservative, nonpharmacologic therapeuticinterventions, few ofwhich are consistently or widely recommended across various guidelinesdespitethestrongevidencefavoringtheuseof ther-apeuticexercisesforchroniclowbackpain.

In 2006, the European guidelines for the management ofchronic nonspecific low back pain were published. The goal of the COST B13 working group was toprovide a set ofrecommendationsthatcouldsupportexistingandfuture guidelines.14 Oneofthemajorstrengths ofthisguidelineis itsmultinationalandmultidisciplinarynature.Theauthors proposedthatchroniclowbackpainshouldnotbe consid-eredasingleclinicalentityandemphasizedtheneedtoassess prognosticfactorsbeforetreatment.

In 2007, the Multinational Musculoskeletal Inception CohortStudy(MMICS)publishedalistoffactorsthatitdeemed

necessarytoexamineinfuturestudiesofprognostic indica-torsforchronicityinpatientswithCLBP.9Theneedtoidentify suchfactorsisunderstandablebecausealthoughonly5%of CLBPpatientsdevelopdisabilities,75%ofallexpensesrelated to low back pain are devoted to that population.1 Conse-quently, most studies on identifying prognostic factors for chronicityanddisabilityhavefocusedonacutelowbackpain patients,andveryfewstudieshavefocusedonthe prognos-ticfactorsfortreatmentresponseinpatientswithestablished CLBP.

Thestudy hypothesisis thatsomebaseline characteris-tics may identify subgroup of CLBP patients with distinct response ratesto treatment. Therefore, weevaluated CLBP patients’ clinicalresponsestoaseriesofsessionsof super-visedphysicalactivityandassessedvariousfactorsincluded intheMMICSrecommendationstodeterminetheirabilityto identifytheprognosticfactorsfortreatmentresponseto con-ventionalphysicaltherapy.

Methods

Patients

Participantswererecruitedthroughadvertisementsdesigned byourpressoffice.Allpotentialparticipantswerescreenedby thesamerheumatologist(ASRH)betweenJanuaryandMarch 2009.ParticipantswhowerediagnosedwithnonspecificCLBP andmettheinclusionandexclusioncriteriawererecruited. Theinclusioncriteriawereagebetween18and80years,pain betweenthe last riband thegluteal foldthatpersistedfor morethanthreemonths,painthatwascontinuousorpresent mostofthetimeandwaspatient’smainpain-related com-plaint,andtheprovisionofinformedconsent.Theexclusion criteriawere adiagnosisofsystemicinflammatorydisease, the presenceofcharacteristicradicularpain, pain originat-ingintheperipheraljoints,osteoarticulardeformitiesinthe lower limbs,decompensated heartfailure, neoplasia inthe previousfiveyears,previouslumbarspinesurgery,systemic diseasethatmightinterferewiththeinterpretationofresults basedonmedicalopinion,aninabilitytounderstand ques-tionnairesandexplanationsortocomplywiththetreatment, physicaltherapyforLBPthatinvolvedphysicalexercisesinthe previousfiveyears,psychiatricdisorders,andfibromyalgiaor painnotlocatedinthelumbarspineasthemainpain-related complaint.

386

rev bras reumatol.2016;56(5):384–390referredtousfromotherdepartmentswithinthehospitaland fromanetworkofprimaryorsecondarycareunitslinkedto thehospital.

Alloftheparticipantssignedaninformedconsentform, andthestudywasapprovedbytheResearchEthics Commit-tee.

Thisstudycompliedwiththeethicalprinciplesofthe Dec-larationofHelsinki(2008)andtheapplicablelocallawsand regulations.Thisresearchwasapprovedbythe localethics andresearchcommittee(ResearchProtocol1110/07).

Physicaltherapyintervention

The treatment consisted of 10 individual sessions: two sessions per week for five weeks. Each session included core-strengtheningexercises(i.e.,exercisesthatinvolvedthe abdominal,pelvicfloor,gluteal,diaphragmaticandpelvic gir-dle muscles), stretching exercises and postural orientation exercises.Allassessmentsandphysicaltherapysessionswere performedbythesamephysicaltherapist.

Assessments

Thepatients’responsestophysicaltherapywereassessedin termsofchanges inpainintensity usingthe Numeric Rat-ing Scale (NRS), which has a range of 0–10, and in terms ofCLBP-relateddisabilityusingtheRoland-MorrisDisability Questionnaire(RMDQ),whichhasarangeof0–24.The partici-pantswereassesseduponinclusioninthestudy,immediately afterthetenphysicaltherapysessions(firstevaluation)and threemonthsafterthefirstevaluation(secondevaluation).

Fortheresponderanalysis,thepatientsweredividedinto responder and nonrespondergroupsaccording tothe indi-vidualchangesinthepainintensityanddisabilitymeasures ateachevaluation.Apatientwasconsideredaresponderif he/sheshowedadecreaseofatleasttwopointsintheNRS score15oratleastfourpointsintheRMDQscore.16Wealso expressedtheresultsasthepercentageofchangefromthe scoreobtainedatbaseline.

Socio-demographicdatawerecollected,acomplete phys-icalexaminationwas performed, and the duration ofpain was assessed at baseline. In addition, all of the partici-pants answered standardizedquestionnaires to assess the factors included inthe MMICS guidelines (smoking, physi-calactivity,occupationalfactors,depression,andcatastrophic thinking) and completed the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Ques-tionnaire (FABQ). The FABQ contains two subscales that were separatelyevaluated: fear-avoidancebeliefsrelated to work(FABQ-work)andphysicalactivity(FABQ-physical).Fear

Table1–Demographic,anthropometricandclinicaldata.

Variables All(n=113)

Age,years 53.0(12.2)a

Female,n(%) 81(71.7)

BMI,kg/m2 27.9(5.1)a

Smoking,n(%) 16(14.2)

Painbelowtheknee,n(%) 73(64.6)

Physicalactivity,n(%) 90(79.6)

Irritability,n(%) 13(11.5)

Depression,n(%) 83(73.5)

Catastrophicthinking,n(%) 35(31.0)

FABQ-physical,n(%) 13(11.5)

FABQ-work,n(%) 46(36.3)

Extraspinalpain,n(%) 35(31.0)

BMI,bodymassindex;FABQ-physical,fear-avoidancebeliefs sub-scaleforphysicalactivity≥15;FABQ-work,fear-avoidancebeliefs subscaleforwork≥34.

a Dataareexpressedasthemean(standarddeviation).

avoidancerelatedtophysicalactivitywasconsideredeither present (score ≥15) or absent (<15), while fear avoidance relatedtoworkwasconsideredpresentiftheFABQ-workscore was≥34.TheBrazilianversionsofallofthesequestionnaires werepreviouslyvalidated.17–20

Thepatientswereconsideredtohaveextraspinalpainif theyhadchronicpaincomplaintsinadditiontoLBPbutdid notfulfillthecriteriaforfibromyalgia.

Statisticalanalysis

The sample size followed the criteria for multiple logistic regressionanalysiswithatleast5–12patientsineachofthe 12explanatoryvariables.

Thenormalityofthedatadistributionwasanalyzedwith the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, and parametric tests were applied.Quantitativedatawereexpressedasthemean(SD), whereasqualitativedatawereexpressedinabsolutenumbers andrelativefrequency.

Thecombinedinfluenceofthevariablesandtimeof eval-uation on the patient response wasassessed witha fitted modelthatusedgeneralizedestimationequations(GEE)with anormalmarginaldistributionandanidentitylinkfunction, assumingsymmetricmatrixcomponentcorrelationsbetween timepoints.

Onlystatisticallysignificantvariableswereretainedinthe finalmodels.Thefitofeachmodelwasverifiedwithresidual analysesthatusedCook’sdistanceordevianceresiduals.The significancelevelwassetat5%.

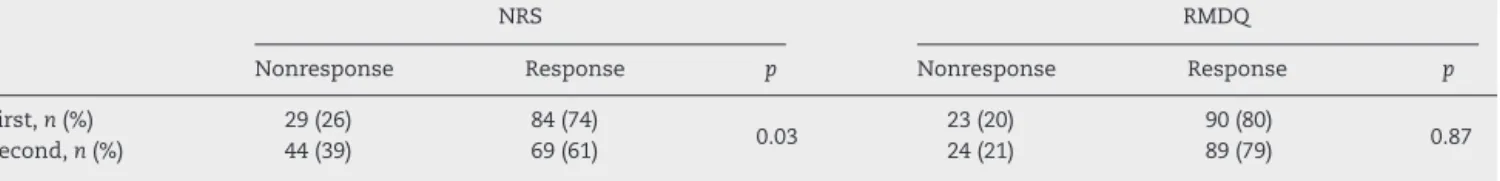

Table2–ResponsetophysicaltherapyforchroniclowbackpainmeasuredwiththeNumericRatingScale(NRS)andthe Roland-MorrisDisabilityQuestionnaire(RMDQ)ateachevaluationtime.

NRS RMDQ

Nonresponse Response p Nonresponse Response p

First,n(%) 29(26) 84(74)

0.03 23(20) 90(80) 0.87

r

e

v

b

r

a

s

r

e

u

m

a

t

o

l

.

2

0

1

6;

5

6(5)

:384–390

387

NRS RMDQ

First Second p First Second p

Non-responder Responder Non-responder Responder Non-responder Responder Non-responder Responder

n=29 n=84 n=44 n=69 n=23 n=90 n=24 n=89

Age,yearsa 53.9(13.9) 52.7(11.6) 53.3(12.3) 52.8(12.2) 0.71 53.5(11.6) 52.8(12.4) 54.1(10.0) 52.7(12.7) 0.65

Female 20(68.9) 61(72.6) 33(75) 48(69.5) 0.81 15(65.2) 66(66.7) 17(70.8) 64(71.9) 0.61

BMI,kg/m2a 27.0(5.0) 28.3(5.1) 28.0(5.5) 27.9(4.8) 0.62 26.9(5.3) 28.2(5.0) 28.1(5.9) 27.9(4.8) 0.60

Smoking 5(17.2) 11(13.1) 7(15.9) 9(13) 0.58 5(21.7) 11(12.2) 4(16.7) 12(13.5) 0.36

Painbelowtheknee 20(69.0) 53(63.1) 33(75.0) 40(58.0) 0.13 17(73.9) 56(62.2) 17(70.8) 56(62.9) 0.30

Physicalactivity 21(72.4) 69(82.1) 34(77.3) 56(81.2) 0.37 18(78.3) 72(80.0) 19(79.2) 71(79.8) 0.88

Irritability 6(20.6) 7(8.3) 7(15.9) 6(8.7) 0.09 3(13.0) 10(11.1) 4(16.7) 9(10.1) 0.50

Depression 22(75.9) 61(72.6) 34(77.3) 49(71.0) 0.51 19(82.6) 64(71.1) 19(79.2) 64(71.9) 0.29

Catastrophicthinking 10(34.5) 25(29.8) 17(38.6) 18(26.1) 0.25 11(47.8) 24(26.7) 9(37.5) 26(29.2) 0.12

FABQ-physical 3(10.3) 10(11.9) 7(15.9) 6(8.7) 0.52 3(13.0) 10(11.1) 4(16.7) 9(10.1) 0.47

FABQ-work 16(55.2) 25(29.8) 26(59.1) 15(21.7) <0.001 10(43.5) 31(34.4) 13(54.2) 28(31.5) 0.09

Extraspinalpain 14(48.3) 21(25.0) 21(47.7) 14(20.3) 0.002 12(52.2) 23(25.6) 9(37.5) 26(29.2) 0.06

BMI,bodymassindex;FABQ-physical,fear-avoidancebeliefsquestionnairesubscaleforphysicalactivity≥15;FABQ-work,fear-avoidancebeliefsquestionnairesubscaleforwork≥34. p<0.05inbold.

388

rev bras reumatol.2016;56(5):384–390Results

From217inquiries,130peoplewithCLBPwereselected. Sev-enteenpatients withdrewbefore the end ofthe scheduled consultationsandwereexcluded.Onehundredthirteen sub-jects completed the study. The main reason reported for withdrawal was difficulty commuting to the rehabilitation centerasoftenasrequired.

Thesampleconsistedof81womenand32menbetween 21 and 80 years old. The cohort consisted of 40% house-wives and pensioners, 16% cleaning personnel, 10% office employeesand31%otheroccupations.Only3%were unem-ployed.ThemeanBMIvaluewas27.9kg/m2,rangingfrom18 to47.ThedurationofCLBPrangedfromthreemonthsto40 years(±0.76years).Additionaldemographic,anthropometric andclinicalcharacteristicsofthesepatientsarepresentedin Table1.

TheresponsetophysicaltherapyasassessedwiththeNRS decreased from the first tothe second evaluation (74%vs. 61%,p=0.03).WhenassessedwiththeRMDQ,thefrequency ofresponsewas similarforboth evaluations(80%vs. 79%, p=0.87;Table2).

TheparticipantswithahighFABQ-workscorehadapoorer outcomeatbothevaluationsbasedontheNRSresults(55% nonrespondersvs. 30%responders and 59%nonresponders vs.22%responders,p<0.001).Thesameresultswereobserved forthepatientswithextraspinalpain(48%vs.25%and48%vs. 20%,p=0.002;Table3).ThehigherFABQ-workscoresandthe greaterfrequencyofextraspinalpainaccordingtotheRMDQ didnotreachstatisticalsignificance(Table3).

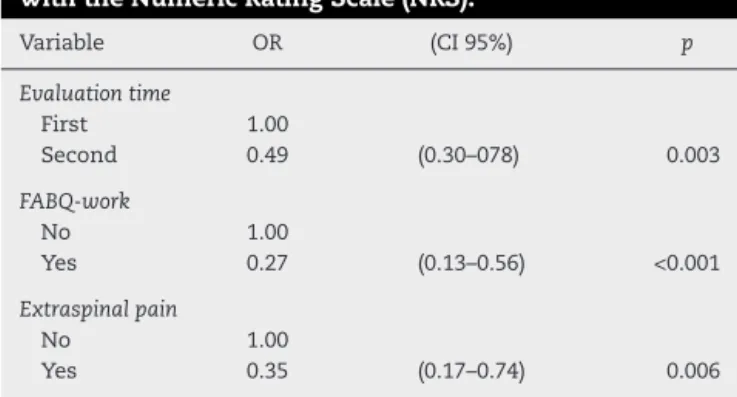

In the final model analysis, the presence of work-related fear avoidance and extraspinal pain remained as independentfactorsassociatedwithnonresponse(OR=0.27, 95% CI=0.13–0.56; p<0.001and OR=0.35, 95% CI 0.17–0.74; p=0.006,respectively;Table4).

Table4–Finalmodeloftheprognosticfactorsforthe responsetoconventionalphysicaltherapyassessed withtheNumericRatingScale(NRS).

Variable OR (CI95%) p

Evaluationtime

First 1.00

Second 0.49 (0.30–078) 0.003

FABQ-work

No 1.00

Yes 0.27 (0.13–0.56) <0.001

Extraspinalpain

No 1.00

Yes 0.35 (0.17–0.74) 0.006

OR,oddsratio;CI,confidenceinterval;FABQ-work,fear-avoidance beliefssubscaleforwork≥34.

Inaddition, weanalyzedthe resultasthe percentageof change intheresponsefrom baseline.BoththeRMDQ and NRSresponserateswerenegativelyinfluencedbyextraspinal painandfearavoidancerelatedtowork(Table5).

Discussion

This study is oneof the few prospectivestudies to assess theprognosticfactorsrelatedtophysicaltherapyforpatients with CLBP.Wefoundthat work-relatedfear avoidance and extraspinalpainnegativelyinfluencedtheoutcome.

Functional disability resulting from CLBP has increased despitenewinterventions.Comparisonsamongstudieshave been obstructed by the use of varied definitions and out-comemeasures.21Inthesamemanner,therearenogolden rulesthatpredicttheresponsetotreatmentforCLBP.22Inthis study,patientswereconsideredrespondersiftheyshoweda

Table5–Bivariateandmultivariateanalysisofthefactorsthatinfluencetheresponsetophysicaltherapy,assessedwith theNumericRatingScale(NRS)andtheRoland-MorrisDisabilityQuestionnaire(RMDQ)andmeasuredasthepercentage ofchangefromthebaseline.

NRS RMDQ

Bivariate Multivariate Bivariate Multivariate

Estimate(SE) p Estimate(SE) p Estimate(SE) p Estimate(SE) p

Age,years 0.19(0.27) 0.499 0.2(0.22) 0.365

Female −7.9(7.35) 0.282 −1.95(5.94) 0.743

BMI,kg/m2 0.03(0.66) 0.964 0.21(0.53) 0.700

Smoking 3.15(9.53) 0.741 −2.63(7.68) 0.732

Painbelowtheknee −10.44(6.89) 0.130 −8.33(5.55) 0.133

Physicalactivity 4.15(8.25) 0.615 7.18(6.62) 0.278

Irritability −11.54(10.37) 0.266 −12.68(8.31) 0.127

Depression −8.48(7.49) 0.257 −13.56(5.93) 0.022

Catastrophicthinking −6.04(7.17) 0.400 −7.84(5.75) 0.173

FABQ-physical 0.56(10.43) 0.958 −2.97(8.39) 0.723

FABQ-work −17.33(6.72) 0.010 −13.8(6.53) 0.035 −13.5(5.42) 0.013 −10.66(5.27) 0.043

Extraspinalpain −23.92(6.83) <0.001 −21.47(6.79) 0.002 −19.16(5.5) <0.001 −17.26(5.48) 0.002

BMI,bodymassindex;FABQ-physical,fear-avoidancebeliefsquestionnairesubscaleforphysicalactivity≥15;FABQ-work,fear-avoidancebeliefs questionnairesubscaleforwork≥34.

decreaseofatleasttwopointsintheNRSscoreorfourpoints intheRMDQscore.Alternatively,weevaluatedtheresponse asthe%ofchangefrombaselineandfoundsimilarresults. Nevertheless,wedidnotperformsensitivityanalyses.Future studiesshouldaddressthisissueinmoredetailtosupportour conclusions.

FABQ-work scores emerged as an important variable despitetheinclusionofalargeproportionofhousewivesinthe studypopulation.Ourfindingssupportthoseofotherstudies withthesuggestionthatindividualizedphysicaltherapy pro-gramsthatfocusondifferentoccupationalactivitiesshould betested.23,24

Inthelast decade,it hasbeenunclear whether psycho-logicalfactorsmeritedinterventionstoreducetheburdenof chronicbackpain.25Whenitwaspublishedin2007,theMMICS suggestedincludingfearavoidanceandother psychological factors(catastrophizinganddepression)inprospective inves-tigationsintothetransitionfromacutetochronicbackpain.9 Thefactorsthatwereincorporatedlargelyreflectedthe opin-ionofexpertsandthereforeweresomewhatsubjectivedespite representingaconsensus.Theimpactofthesecomponents onthetreatmentstrategyforchronicbackpain(andnotonly intheearlystages)islesswellestablished.Inourstudy,fear avoidance,butnototherpsychologicalfactors,influencedthe outcomes.

Extraspinal pain was another important factor that affectedthetreatmentresponse.PatientswithLBPasthemain complaintdidbetterwhentheyhadnoothersitesofpain. Ithasbeenalreadysuggestedthatindividualswithchronic painoftenpresentwithmorethanonepainfulcondition,26but theimportanceofthisobservationtotreatmentandprognosis remainsunclear.

Inourstudy,mostofthepatientsimprovedsignificantly with physical therapy. The protocol used consisted of a seriesofexercisesthatarecommonlyappliedandthathave a well-established level of efficacy in the literature.27 It is worth mentioning that the responserate, asmeasured by the NRS, decreasedafter threemonthsoftreatment; how-ever,thisphenomenonwasnotobservedfortheRMDQ,which suggests thatphysicaltherapy had morelastingeffectson functionthan onpainperception.Perhapsphysicaltherapy programsaffectpatients’abilitytocopewithpain.Thisissue shouldbeevaluatedinfuturestudieswithlongerfollow-up periods.

Unfortunately,thesampleusedinthis studyincluded a largeproportionofhousewives,whichpreventsthe extrapo-lationoftheseresultstootherpopulations.Althoughalarge numberofpatientswere assessed,CLBPisaverycommon condition;thus,evenlargerstudiesmustbeconductedin var-iousemploymentandbiopsychosocialcontexts.Itshouldbe mentionedthatthestudylasted onlythreemonths; conse-quently,itdidnotaddresstheneedforre-treatmentorthe long-termdurationoftheresponse, norwasit designedto addresstheimportantquestionofpatients’abilitytoreturn towork.

Epidemiologicalstudieshaveshownthatthespectrumof musculoskeletaldisordersindevelopingcountriesissimilar tothatobservedinindustrializedcountries,buttheburdenof diseasetendstobehigherbecauseofdelaysindiagnosisor alackofaccesstoadequatehealthcarefacilitiesforeffective

treatment.28InBrazil,mostpatientswithCLBPwillreceive aprescriptionforlimitedsessionsofphysicaltherapyinan almostuniversal manner;however, theresultsofourstudy suggest thatphysicaltherapy,suchasothertreatmentsfor CLBP,shouldbeindividualizedaccordingtospecificpatient characteristics.

Fear avoidance could be a barrier to recovery from chronicbackpainregardlessofthetreatmentmodality.We believe that fear avoidance should be routinely tested to help practitioners and researchers define better treatment strategies.

Inconclusion, weidentified fear-avoidancebeliefs about workandthepresenceofextraspinalpainascharacteristicsof subgroupsofpatientswhomayrequirecustomizedtreatment protocolsandspecialrehabilitationprogramsforCLBP.

Funding

Coordenac¸ãodeAperfeic¸oamentodePessoaldeNívelSuperior (CAPES)(ASAF).

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1.GoreM,SadoskyA,StaceyBR,TaiKS,LeslieD.Theburdenof chroniclowbackpain:clinicalcomorbidities,treatment patterns,andhealthcarecostsinusualcaresettings.Spine. 2012;37:E668–77.

2.SalvettiMdeG,PimentaCA,BragaPE,CorrêaCF.Disability relatedtochroniclowbackpain:prevalenceandassociated factors.RevEscEnfermUSP.2012;46:16–23.

3.MeziatFilhoN,SilvaGA.Disabilitypensionfrombackpain amongsocialsecuritybeneficiaries,Brazil.RevSaudePublica. 2011;45:494–502.

4.DuffyRL.Lowbackpain:anapproachtodiagnosisand management.PrimCare.2010;37:729–41.

5.ChouR.Pharmacologicalmanagementoflowbackpain. Drugs.2010;70:387–402.

6.VanMiddelkoopM,RubinsteinSM,KuijpersT,VerhagenAP, OsteloR,KoesBW,etal.Asystematicreviewonthe effectivenessofphysicalandrehabilitationinterventionsfor chronicnon-specificlowbackpain.EurSpineJ.2011;20:19–39. 7.WestromKK,MaiersMJ,EvansRL,BronfortG.Individualized

chiropracticandintegrativecareforlowbackpain:thedesign ofarandomizedclinicaltrialusingamixed-methods approach.Trials.2010;11:24.

8.SchaafsmaFG,WhelanK,vanderBeekAJ,vander

Es-LambeekLC,OjajärviA,VerbeekJH.Physicalconditioning aspartofareturntoworkstrategytoreducesicknessabsence forworkerswithbackpain.CDSRev.2013;8:CD001822. 9.PincusT,SantosR,BreenA,BurtonAK,UnderwoodM, MultinationalMusculoskeletalInceptionCohortStudy Collaboration.AreviewandproposalforaCoresetoffactors forprospectivecohortsinlowbackpain:aconsensus statement.ArthritisRheum.2008;59:14–24.

390

rev bras reumatol.2016;56(5):384–39011.DagenaisS,TriccoAC,HaldemanS.Synthesisof

recommendationsfortheassessmentandmanagementof lowbackpainfromrecentclinicalpracticeguidelines.SpineJ. 2010;10:514–29.

12.PillastriniP,GardenghiI,BonettiF,CapraF,GuccioneA, MugnaiR,etal.Anupdatedoverviewofclinicalguidelinesfor chroniclowbackpainmanagementinprimarycare.Joint BoneSpine.2012;79:176–85.

13.KoesBW,vanTulderM,LinCW,MacedoLG,McAuleyJ,Maher C.Anupdatedoverviewofclinicalguidelinesforthe managementofnon-specificlowbackpaininprimarycare. EurSpineJ.2010;19:2075–94.

14.AiraksinenO,BroxJI,CedraschiC,HildebrandtJ,

Klaber-MoffettJ,KovacsF,etal.Europeanguidelinesforthe managementofchronicnonspecificlowbackpain.EurSpine J.2006;15Suppl.2:S192–300[Chapter4].

15.FarrarJT,YoungJPJr,LaMoreauxL,WerthJL,PooleRM. Clinicalimportanceofchangesinchronicpainintensity measuredonan11-pointnumericalpainratingscale.Pain. 2001;94:149–58.

16.CecchiF,NegriniS,PasquiniG,PaperiniA,ContiAA,ChitiM, etal.Predictorsoffunctionaloutcomeinpatientswith chroniclowbackpainundergoingbackschool,individual physiotherapyorspinalmanipulation.EurJPhysRehabil Med.2012;48:371–8.

17.PardiniR,MatsudoS,AraújoT,MatsudoV,AndradeE, BraggionG,etal.Validationoftheinternationalphysical activity(IPAQ–version6):apilotstudyinyoungBrazilians. RevBrasCiencMovBrasilia.2001;9:45–51.

18.BatistoniSS,NeriAL,CupertinoAP.ValidityoftheCenterfor EpidemiologicalstudiesdepressionscaleamongBrazilian elderly.RevSaudePublica.2007;41:598–605.

19.SardaJJ,NicholasMK,PereiraIA,PimentaC,AsghariA,Cruz RM.Validationofthescaleofpaincatastrophizingthoughts. SãoPaulo:ActaFisiatra.2008;15:31–6.

20.AbreuA,FariaCD,CardosoSM,Teixeira-SalmelaLF.The Brazilianversionofthefearavoidancebeliefsquestionnaire. CadSaudePublica.2008;24:615–23.

21.DeyoRA,DworkinSF,AmtmannD,AnderssonG,Borenstein D,CarrageeE,etal.ReportoftheNIHTaskForceonResearch standardsforchroniclowbackpain.SpineJ.2014;14: 1375–91.

22.HenschkeN,vanEnstA,FroudR,OsteloRW.Responder analysesinrandomisedcontrolledtrialsforchroniclowback pain:anoverviewofcurrentlyusedmethods.EurSpineJ. 2014;23:772–8.

23.PatelS,NgunjiriA,SandhuH,GriffithsF,ThistlewaiteJ,Brown S,etal.Designanddevelopmentofadecisionsupport packageforlowbackpain.ArthritisCareRes.2014;66:925–33. 24.MainCJ,GeorgeSZ.Psychologicallyinformedpracticefor

managementoflowbackpain:futuredirectionsinpractice andresearch.PhysTher.2011;91:820–4.

25.PincusT,VlaeyenJW,KendallNA,VonKorffMR,Kalauokalani DA,ReisS.Cognitive-behavioraltherapyandpsychosocial factorsinlowbackpain:directionsforthefuture.Spine (Phila,PA1976).2002;27:E133–8.

26.DavisJA,RobinsonRL,LeTK,XieJ.Incidenceandimpactof painconditionsandcomorbidillnesses.JPainRes. 2011;4:331–45.

27.DelittoA,GeorgeSZ,VanDillenLR,WhitmanJM,SowaG, ShekelleP,etal.Lowbackpain.JOrthopSportsPhysTher. 2012;42:A1–57.