Culture on the Rise: How and Why Cultural Membership

Promotes Democratic Politics

Filipe Carreira da Silva&Terry Nichols Clark& Susana Cabaço

# Springer Science+Business Media New York 2014

Abstract Selectively using Tocqueville, many social scientists suggest that civic participation increases democracy. We go beyond this neo-Tocquevillian model in three ways. First, to capture broader political and economic transformations, we consider different types of partic-ipation; results change if we analyze separate participation arenas. Some are declining, but a dramatic finding is the rise of arts and culture. Second, to assess impacts of participation, we study more dimensions of democratic politics, including distinct norms of citizenship and their associated political repertoires. Third, by analyzing global International Social Survey Programme and World Values Survey data, we identify dramatic subcultural differences: the Tocquevillian model is positive, negative, or zero in different subcultures and contexts that we explicate.

Keywords Political culture . Civic participation . Citizenship . Voluntary organizations

The world is changing, arguably more rapidly and profoundly in recent decades than since the Industrial Revolution. Manufacturing is in deep decline; the percent of manual laborers has fallen by over half in most industrial countries since the 1950s. This in turn has transformed the political party system, as unions decline and left parties seek new social bases. All sorts of new civic groups emerge with global NGOs, the Internet, blogs, and new media/engagement strategies. Yet most thinking and theorizing about society and politics lags. Most of our models of civic groups, participation, and democracy come from an industrial era where class politics and party conflict dominated analysis. And as we think more globally, and look at broader patterns to help reframe the North American/European experience, what is“established” grows less clear.

Approximately at the same time as the post-industrial political transformation in the West, the post-1989 transition to democracy in Eastern Europe led analysts to ask a question most ignored in the West—what are the conditions for democracy to flourish? To answer this, political scientists rediscovered Alexis de Tocqueville. Chief among them was Robert D. Putnam, who in Bowling Alone enshrined Tocqueville as“patron saint” of the social capital approach to emphasize the civic DOI 10.1007/s10767-013-9170-7

F. C. da Silva (*)

:

T. N. Clark:

S. Cabaço University of Lisbon, Lisbon, Portugal e-mail: fcs23@ics.ul.ptT. N. Clark

e-mail: tnclark@uchicago.edu S. Cabaço

virtues of participation in voluntary social organizations (Putnam1995). The influence of this Putnam-Tocqueville model has been substantial. “Trust” and “social capital” have become buzzwords of early twenty-first century political science. Social capital has been critiqued in many ways, but one main point here is that its use encouraged analysts to lump together all forms of organizational membership—unions, churches, and political parties. Thus, “participation” or “membership” in the exemplary research usually sums up activities of each of these sorts (Verba et al.1993; Zukin et al.2006).

Yet, if we break out participation into its components, we find dramatic differences from the “bowling alone” story. Voting and participation in general politics has declined in many countries since the 1980s, as has been widely reported. But barely noted is the rise of the arts and culture in these same years, even though some World Values Survey items suggest massive increases in arts and culture participation in various countries.1This is all the more surprising given its ubiquitous character. From mayors' agendas for urban renewal to the general population's practices, the arts have become a major area of political interest, economic investment, and self-realization in most developed countries. This global rise of arts and culture has been largely ignored until now for two main reasons. On one hand, most studies on the arts are case studies whose authors have not sought to explore the broader and the political implications of arts participation.2On the other hand, leading quantitative studies of arts and culture participation tend to focus on the traditional arts (live theater, symphony concerts, visiting museums) and omit such new activities as playing in a small band and many digital arts (graphic design, video, web and interactive design, animation). Still, there is by no means consensus here: rather many if not most writings on the arts suggest a decline rather than growth in recent decades. The main resolution of this conflict is to focus on what types of art and culture.

The more established“high” art like classical music concerts, opera, and museum attendance show stability or decline in many countries. This has led to a sense of crisis in many arts organizations, like the U.S. National Endowment for the Arts which commissioned multiple studies. Many showed the classic decline of the“benchmark” high arts, but Novak-Leonard and Brown (2011) showed high participation and growth in some nontraditional activities. And the French Ministry of Culture studies document this pattern with more detail, growth in media related film, music, and more, especially among young persons who create personal entertainment libraries. These have often been missed as they are not classic benchmark items, but many are captured in the World Values Survey item which permits the respondent to include all arts and culture items in which she participates.3We hope to nudge social scientists to catch up to these developments.

1

Data from World Values Survey of national samples of citizens in each country. Question: A066.“Please look carefully at the following of voluntary organizations and activities and say…which if any do you belong to? Education, Arts, Music or Cultural Activities.” In Canada, a study on citizens' preferences regarding federal spending points in the same direction, by finding that one of the few items that show significant change between 1994 and 2010 is support for “arts and culture,” which climbed from 15 to 30 %. Seehttp://www.queensu.ca/cora/_files/fc2010report.pdf 2

Most studies on the arts are case studies whose authors have not sought to explore the broader and the political implications of arts participation: see, e.g. Lloyd (2006). Since finding these results in the World Values Survey, we have looked for other studies that might have reported similar results and found them inconsistent. An exception is Stolle and Rochon (1998), even though it is limited to three case-studies.

3

The main source of the data used in our statistical analysis is the World Values Survey (1999–2004 wave). Since our main variable of interest—belong to education, arts, music, or cultural activities—is not included in the fifth wave of the WVS (2005–2007), we do not use data from that wave. A slightly different model was implemented on vote (on the social participation bloc, we only had information for religious and cultural groups): in this case, we used the International Social Survey Programme 2004 data. We also run the same model using as moderator variables: political cultures, i.e., new political culture, class/party politics, and clientelism and cultural traditions. We are using secondary data sources of already existent data. This implies that we are not only limited to a specific period of time, geographical scope, but we are also limited in terms of substantive information provided by each item surveyed.

This article discusses the political implications of what we call“the rise of culture.” The rise of arts and culture, far from being an anomaly, is part and parcel of a much broader and deeper set of changes in an emerging form of politics lived by many, especially younger persons. It is a strategic research site where our litmus test results flag much broader and deeper changes, if we look. Culture can be about politics as well as personal identity. It can be part of one's job, but is more likely part of consumption—in a world where political candidates in their campaigns and actions stress consumption issues increasingly. Arts and culture may have some direct economic implications, but is more generally about meaning and value. For some in a secular but idea and image-driven world, music and books and their related activities replace the church and god and the functions of religion in earlier eras. For young persons breaking with their families and religious and work backgrounds, a charismatic singer like Madonna or Bruce Springsteen is more than entertainment. A reading group discussing Nietzsche, Marx, or Baudrillard can transform its members' thinking. While sympathetic towards the hermeneutically inspired “cultural turn” in American sociology, we seek to complement it with cross-national survey-based data, as this is the only way to capture broad, global sociopolitical changes.

Analysts have sought to capture these profound sociopolitical changes with labels like post-industrial society, the knowledge economy, the third way, neo-liberalism, the creative class or economy, the consumer society, post-modernism, and more. What these have in common is stressing that the rules of many past models no long seem to work or demand qualification. How do any others specifically link to the growing salience of culture and the arts in the past few decades (see Fig.1), with structural socioeconomic changes in developed societies around the world? The answers are clearly diverse but we introduce just one effort to join these changes in systematic manner, based on our past work. Many others are possible, and we hope to encourage alternative interpretations that may extend our effort here.

Our past work documented elements of this structural socioeconomic change as the rise of the“new political culture” (henceforth NPC). This original blend of social liberalism and fiscal conservatism was first identified in the 1970s urban America. What drives the shift toward the NPC? Seven general elements have been suggested to help understand the emergence of the NPC: (1) the classic left–right dimension has been transformed; immigration, women, and many new issues no longer map onto one single dimension; (2) social and fiscal/economic issues are explicitly distinguished, work no longer drives all; (3) social and cultural issues like identity, gender, morality, and lifestyle have risen in salience relative to fiscal/economic issues; (4) market individualism and social individualism grow: people seek to mark themselves as distinct from their surroundings; (5) the post-war national welfare state loses ground to federalist and regionalist solutions; parties, unions, and established churches are often replaced by new, smaller organizations that may join into social movements; (6) instead of rich vs. poor, or capitalisms vs. socialism, there is a rise of issue politics—of the arts, the environment, or gender equality—which may spark active citizen participation on one such issue, but each issue may be unrelated to the others; and (7) these NPC views are more pervasive among younger, more educated and affluent individuals, and societies.

Citizens changed first in these respects, and leaders and analysts widely ignored these deep changes; many still do. But no longer do clientelism and class politics dominate politics as they did a few decades back. They are challenged by all manner of“reformers,” some of whom relate to this new political culture. Many local and national political leaders came to adopt a NPC agenda in Europe, Asia, and Latin America, like Bill Clinton or Tony Blair or Antanas Mockus. In the 1990s, with the acceleration of economic globalization and the digital revolution (encompassing technological innovations such as the Internet, mobile phones, and personal computers), the shift from production to consumption started to capture the attention of social scientists. Two research questions, in particular, have been pursued. First,

how and why is the growing prevalence of NPC associated with the replacement of class politics by issue politics? Second, how and why is the development of the NPC associated with the rise of consumption politics and the importance of amenities (for instance, in driving local development)? Behind these questions is the hypothesis that the rejection of hierarchy and welfare paternalism are in favor of horizontal, issue-politics increase as societies become more post-materialist, NPC.

The article is organized as follows. We start by describing the analytical model, where we explain the main assumptions and research hypotheses behind this study. This includes a justification of our conceptual choices (“Research Design and Data Collection”). Next, we

present our research design. Here, we discuss the main methodological issues we faced in conducting data analyses (“Findings”). We then present our findings (“Conclusion”).

Specifically, we discuss the impact of our seven “contextual variables” in the relationship between cultural membership and democratic politics: these include three political cultures (class politics, clientelism, the new political culture) and four cultural traditions (Eastern religions, Orthodox Christianism, Catholicism, and Protestantism). Finally, we conclude the article by pointing out some of the most important implications of the current rise of culture, both for the purposes of policy making and for the social scientific research of politics.

Analytical Model

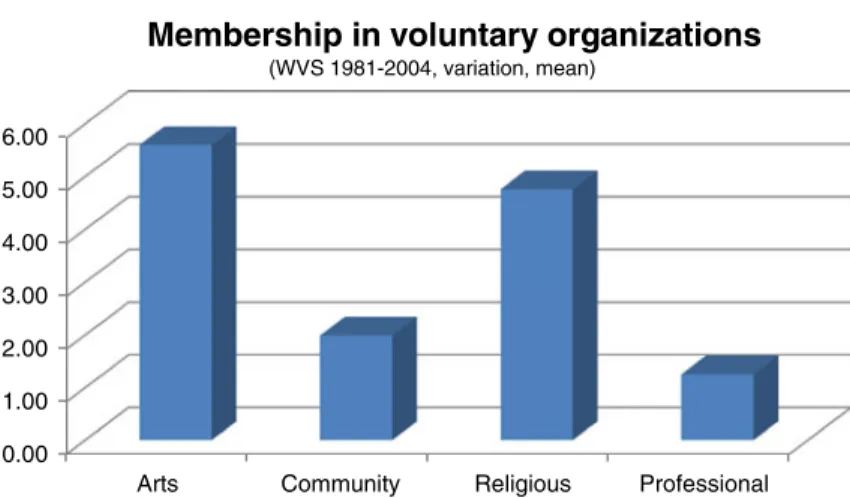

As noted above, the simpler patterns that have been widely used (like the decline in voting or bowling alone) do not hold consistently if we break out participation into separate issue areas, age groups, and countries. To make sense of these apparent disparities demands a subtler analytical model. If we look closely, we find that arts and culture are powerfully tied to other aspects of democratic life. But specifics vary by political cultures that follow disparate rules of the game. To clarify these patterns, we have extended past modeling about democratic politics to investigate impacts of culture, as follows. We include the core independent and dependent variables used by past analysts of citizen participation, but with two critical additions. First, we break out cultural participation from other content types of social participation—religious, community, and professional voluntary organizations—and compare its impacts to those of these other types. Second, we explore how these effects shift across political cultures. These two changes generate dramatic differences from most past work.

The central path we explore is how cultural participation, here defined as membership in organizations by type as surveyed in the World Values Surveys (more below), impacts democratic politics. In turn, our conception of democratic politics includes political practices (protest, vote), norms of citizenship (citizens' beliefs about what makes one a“good citizen”), and attitudes (social and political trust). We hypothesize that the impact of cultural membership on each of these components of democratic politics will not be homogeneous; rather, it will vary by context. We analyze the impact of cultural membership on democratic politics in several ways. First, we consider direct effects of the standard socioeconomic variables (sex, age, education, income, and left–right self-positioning). Second, we compare the impact of cultural membership with the impact of other types of voluntary organizations, religious, professional, and community. Next, we analyze how these patterns shift across contexts, political cultures, and traditions (shown at the bottom of Fig. 2 as interacting with the direct effects). These

illuminate how participating in a cultural organization shifts in meaning and impact on democratic politics when we move from one context to another. The main data is from successive cross-sectional national surveys of citizens (more below). As a result, while we sometime use causal language to simplify exposition, most relations are literally associations.

Dependent Variables

Let us begin by explaining our conception of democratic politics.4Much civil society research has developed under the influence of Putnam's well-known jeremiad: civic participation is said to be in decline since the 1960s, with serious implications for the health of democracy. We suggest that this decline covers only part of what has happened in the last half a century. Another part of the change is a structural differentiation of political participation patterns accompanying the generational shift, societal value change, and socioeconomic modernization in dozens of countries around the world since the 1960s. Political repertoires of younger cohorts are larger than those of their predecessors (e.g., Tilly2006, pp. 30–59). Our stress on

expanded democratic repertoires joins the structural differentiation to overcome a narrow and conservative understanding that informed part of the communitarian revival of Tocqueville in the 1990s. For example, even Welzel, Inglehart, and Deutsch's recent discussion of elite-challenging repertoires shows a bias towards protest activities. Strikes, which enjoy constitu-tional protection in virtually all consolidated democracies, are excluded from their model under the grounds of their alleged“violent” nature (Welzel et al.2005).

To make our conception of democratic politics more empirically realistic and theoretically sound, we consider three broad categories of democratic political participation. First, we include voting and political campaigning,5 the traditional mechanisms of political participation in representative democracies whose symbolic and non-instrumental functions have become recently re-appreciated. Second, we explore the work of Putnam, Kenneth Newton, Francis Fukuyama, and others in considering citizens' attitudes of trust in each other (social or interpersonal trust) and in the government and other institutions (political trust).6 Third, we analyze elite-challenging modes of political mobilization.7This last category includes noncon-ventional political actions such as participation in demonstrations, signing petitions, writing political commentary in blogs, or boycotting certain products for ethical reasons. Together with voting and trust, protest is one of the three dimensions of democratic politics our model seeks to explain. If we no longer consider the New England, town meeting model of civic participation as the sole yardstick of democratic politics, but we include all three types just listed, we find no general decline in political participation. While some forms of political action become less popular (e.g., voting in certain countries), others are growing, and still others have emerged in recent years (e.g., political blogs or online petitions) (Dalton 2007). Whereas we try to overcome the conservative bias of the Putnam-Tocqueville model by enlarging what counts as democratic participation to include protest activities along with trust and voting, we try to avoid its parochialism by enlarging the scope of norms of citizenship with which it operates.

Norms of citizenship encompass the values and representations individuals have of their relation with democratic authorities qua citizens. What are the civic virtues that one should exhibit to be considered an exemplary citizen? The existing literature, both in political theory

4

We thus restrict our analysis to democratic countries. Our list of 42 democratic countries is based on the Polity Score. Details of the indicators that constitute the index and the criteria for the classification of countries, according to the information, are available athttp://www.systemicpeace.org/polity/polity4.htm.

5

“Representative democracy” is an index composed of the following variables: “voted in last election” and “political action: attend political meetings or rally” (source: International Social Survey Programme 2004). 6

“Social trust” is an index composed by the variables: most people can be trusted; do you think people try to take advantage of you ((1)“can't be too careful,” (2) “most people can be trusted”). Trust in political institutions corresponds to the variable confidence in the government (1“none at all” to 4 “a great deal”) (source: World Values Survey 1999–2004; see, e.g., Rothstein and Stolle2008).

7

“Protest” is an index composed by the following variables: political action—sign petition; joining boycotts; attending lawful demonstrations; joining unofficial strikes; and occupying buildings and factories. They have three-point scale: 1,“would never do”; 2, “might do”; and 3, “have done” (source: World Values Survey 1999–2004).

and empirical political science, is often insensitive to the variety of normative understandings regarding citizenship. For example, neo-republicanism often suggests that there is one ideal set of civic virtues: in the civic republican tradition back to Cicero, Harrington, and Machiavelli, contemporary political theorists try to deduce the civic virtues that the citizens of contemporary nation-states should strive toward (e.g., Pettit 2000). In the empirical tradition, albeit less philosophically sophisticated than their fellow political theorists, political scientists are argu-ably more sensitive to the heterogeneous nature of the normative fabric of citizenship. Hence, empirically oriented political scientists such as Dalton (2007) and Denters et al. (2007) identify several different norms of citizenship in the USA and Europe. We adopt some of those norms here. Specifically, our model includes the“duty-based,”8“engagement,”9 and“solidarity”10 norms of citizenship. In addition, we use a second cleavage that has received some theoretical treatment in recent years (Habermas1994,2001). We refer to the distinction between identity politics and the rule of law, i.e., between“thick” and “thin” norms of citizenship (Lewin-Epstein and Levanon2005). Concomitantly, we distinguish between“identity-based” norms of citizen-ship and“legal-civic” ones.11By adding an ethnic vs. civic axis to our model, we wish to add an important corrective to analyses largely based on socioeconomic (civic) norms.

Contextual and Independent Variables

In what follows, we discuss the several contextual12and independent variables in our model of the impact of cultural membership in democratic politics, as well as the axioms behind each of them. The model's first axiom concerns socioeconomic development. Democratic politics is associated with higher levels of income and education and younger individuals.13To be able to 8

The“duty-based” norm is an index composed by the following WVS variables: give authorities information to help justice; future changes: greater respect for authority; national goals: maintaining order in nation; and also by ISSP 2004 variables: good citizen: always vote in elections, never try to evade taxes, always obey laws, and serve in the military.

9The“engagement” norm is an index composed by the following WVS variables: politics important in life; reasons to help: in the interest of society; discuss political matters with friends and also by ISSP 2004 variables: good citizen: keep watch in government; active in associations; understand other opinions; choose products with ethical concerns; and help less privileged in the country/in the world.

10The“solidarity” norm is an index composed by the following WVS variables: importance of eliminating big income inequalities; reasons for voluntary work: solidarity with poor and disadvantaged; and ISSP 2004 variables: rights in democracy: government respect minorities; access to adequate standard of living; and tolerance of disagreement.

11

In the case of the ethnic/civic norm axis (identity and civic norms), we only have information in the World Values Survey in one variable. In the absence of other options, we maintain it in our analysis in these circumstances. In the ISSP 2004, there was no information available on this normative dimension. The WVS variable is: how proud of nationality (civic norm: not very/not at all proud).

12

Both NPC and CP are statistical indexes composed by World Values Survey items (fourth wave, described below). The different political cultures are multidimensional phenomena so a single indicator cannot measure them adequately. The means of the NPC and CP indexes were calculated across all respondents. In the analysis, the filtering criterion was inclusion of the observations that scored above the average value. The results from the regression estimates were then compared to each dominant political culture. For clientelism, due to the lack of available survey data, the measure was the index provided by Worldwide Governance Indicators (in this case, all respondents received the corresponding national figure). We also analyze potential effects of cultural or civilizational traditions on political behavior and beliefs (a relation extensively studied by S. Eisenstadt). These traditions correspond to the historically dominant religious culture associated with each country (Protestantism, Catholicism, Orthodox Christianity, and Eastern religions). Each country in our sample was classified by its dominant cultural tradition and, in each regression analysis, the countries that did not belong to the tradition were filtered out.

13

In a recent article, Amy C. Alexander and Christian Welzel similarly point out that“empowering socioeco-nomic conditions” are conducive to make “people capable of practicing democracy”: see Alexander and Welzel (2011).

form an opinion and express it coherently, to show interest in affairs that transcend the immediate private sphere, and to make political claims in public are all instances of political conduct that presuppose an educated, motivated, and informed citizenry. The shift from class politics to the new political culture, or post-materialism in Ronald Inglehart's parlance (1977), was driven by the economic and social development of democratic countries in the second half of the twentieth century. As societies become more affluent and democratic regimes consolidate, materialist concerns with existential security are joined by other post-materialist ones such as quality of life, social tolerance, and self-expression. This new political culture provides a unique blend of social liberalism, tolerance, and anti-clientelism with fiscal conservatism. As a result, clientelism and hierarchical institutions are increasingly rejected: as the 2009 example of Japan's traditional political system breakdown illustrates, concerns with equality and transparency are gradually rising on political agendas around the world. Three of the model's contextual variables are thus political cultures associated with socioeconomic modernization processes: class politics (or materialism),14 clientelism,15 and the new political culture (or post-materialism).16

The central element of our second axiom, cultural traditions, helps us understand the shaping influence of broad, civilization value systems on political behavior and beliefs. In line with the “multiple modernities” paradigm developed by Eisenstadt (2008) and his associates, these cultural traditions can be traced back to the religious culture that historically has dominated each country we are studying. We use this as a measure of the multiple civilizational configurations that compose the world today (e.g., Norris and Inglehart2004). Our model includes four of these cultural–civilizational traditions, namely Protestantism, Catholicism, Orthodox Christianity, and Eastern religions.17The expectation is that the greater the influence of principles such as individual autonomy and personal expression in a certain cultural tradition, the more likely it is for it to be associated with norms of citizenship and types of political participation that emphasize critical engagement and creative self-realization. To be concrete, we expect, for instance, that cultural membership in Protestant countries to be more highly correlated with the engagement norm of citizenship and protest types of participation than in countries where the dominant cultural tradition is Catholicism, Orthodox Christianity, or a Eastern religion such as Buddhism or Confucianism.

Our third axiom refers to the political benefits of individual membership in voluntary associ-ations. We focus on this particular mode of civic involvement (and not, say, in active participation, volunteering, or donation of money) for theoretical and methodological reasons. There are several explanations for the positive impact of cultural membership on democratic politics. One is suggested by practice theory. In Distinction, Pierre Bourdieu notes the virtuous relationship between types of newspaper reading and political engagement, as Mike Savage et al. in Culture, Class, Distinction aptly recall (Savage et al.2009, pp. 95–96, 106). This was not, however,

Bourdieu's primary interest. Rather, Bourdieu's main goal is to articulate a theory of social stratification based on aesthetic taste:“art and cultural consumption are predisposed, consciously 14

Class/party politics is an index composed by the WVS variables: work orientations: compared with leisure; materialism orientations; and society aimed: extensive welfare vs. low taxes.

15Clientelism is measured by Worldwide Governance Indicators, which include control of corruption; rule of law; regulatory quality; government effectiveness; political stability and absence of violence; and voice and accountabil-ity. More information is available here: http://web.worldbank.org/WBSITE/EXTERNAL/WBI/ EXTWBIGOVANTCOR/0,,menuPK:1740542~pagePK:64168427~piPK:64168435~theSitePK:1740530,00.html. 16New political culture is an index composed by the WVS variables: being with people with different ideas; choose products with environmental concerns; and post-materialism four-item scale (maintain order; greater democracy; curb inflation; greater freedom of speech), in which items 1 and 3 express a materialist orientation, whereas 2 and 4 indicate post-materialist values.

17

In the case of cultural traditions (Protestant, Catholic, Orthodox Christianity, and Eastern religions), each respondent is linked to each one of these four types depending on the dominant cultural tradition in his/her country.

and deliberately or not, to fulfill a social function of legitimating social differences” (Bourdieu 1979, p. 7). Bourdieu's elite-mass model of cultural taste has not gone unchallenged, however.

First, as Laurent Fleury notes, by according to the experience of the working classes the kind of attention previously reserved to the culture of the highly literate and by taking an interest in design, advertizing, audiovisual products, the transmission and exploitation of knowledge, as well as recreational activities, leisure, and tourism,“cultural studies” played a part in promoting the ubiquity of the“cultural” (Passeron et al.2003; Fleury2013, p. 49).

Second, Bourdieu has been challenged by the work of Peterson and Simkus on“culture omnivores” (Peterson and Simkus1992), which showed that people of higher social status were not averse to participation in activities associated with popular culture. Indeed, high status people were adding practices and cultural forms to their cultural repertoire at an accelerating rate: they were omnivores because they were developing a taste for everything. Research on cultural omnivores focuses on the individuals and their practices, while our past work has focused instead on their political culture (NPC). Despite the different analytical focuses, we are both tapping into the same rising pattern: cultural omnivores, who tend to adopt a NPC,“tend to be more politically engaged” (Chan2013). Consistent with DiMaggio (1996), Chan uses the British Household Panel Survey to suggest that“omnivores are quite distinctive in their social and political attitudes. Compared with visual arts inactives, omnivores are more trusting and risk taking. They are also more supportive of the supranational European Union, and they tend to eschew subnational and ethnic identities, which suggests a more open and cosmopolitan outlook. Omnivores are more egalitarian in their gender role attitudes, and they are more liberal on homosexuality. Omnivores are greener regarding the environment and climate change which can be interpreted as them having more trust in scientific authority” (Chan 2013, p. 29). However, Chan, apart from the observation that it is related to social status (but not social class), provides no explanation for these political effects of being a cultural omnivore.

A different line of inquiry into the political effects of cultural consumption lies in the intersection between American pragmatism and Frankfurt school critical theory, namely Axel Honneth's attempt to reconnect Mead and Hegel in the form of a theory of recognition. François Matarasso, the author of the influential albeit methodologi-cally controversial 1997 Use or Ornament? The Social Impact of Participation in the Arts (1997), has recently suggested that Axel Honneth's theory of recognition provides an explanation for his findings (2010, p. 5).

To better appreciate the pragmatic origins of Honneth's proposal, consider Belfiore's and Bennett's The Social Impact of the Arts. An Intellectual History. From classic Greece and turn of the century American pragmatism, they review many theories that suggest the arts' positive impact in promoting “man's sense of well-being and his health, as well as his happiness” (Belfiore and Bennett2008, p. 102). They cite contemporary studies that show a link between cultural participation and longevity. While these studies have not established a causal relation between cultural participation and the beneficial physiological processes associated with longevity, they suggest nonetheless that if democracy is not merely a form of government, but a“way of life, social and individual” (Dewey [1937] 2008, LW11, p. 217), then it depends on the widespread participation of a community in a dialogue over its ends, the quality of which would depend upon the quality of that community's democratic culture. To improve democratic culture, the pragmatist would explore ways to improve public deliberation and civic participation, which would include education and the arts. In short, cultural participation promotes the sort of active, creative training by “spectators” which democracy needs to flourish if it is conceived of as a way of life.

A final possible explanation for the positive effects of cultural membership on democratic politics is that the political is itself aesthetic in nature. The idea that the political is aesthetic has

been explored by authors such as Hannah Arendt in Lectures on Kant's Political Philosophy (1982), where she describes the human condition of action as the “political” that is both existential and aesthetic, and Jacques Rancière in Disagreement (2004). By contrast, echoing Nietzsche, Max Weber suggests that aesthetics is close to eroticism and largely follows subjective, deep dynamics relatively distinct from the economy and politics.

Consider empirical studies on the relationship between cultural membership and political participation. Several authors suggest that the more intense forms of civic participation are more strongly correlated with political action (Rosenblum1998; Wilson2000). Our hypothesis here, following Tocqueville, is that social participation fosters political participation. However, pace Putnam but still following Tocqueville, we qualify this claim: we presuppose that not all types of voluntary organizations are equally beneficial to democratic life. Some, in fact, can be harmful (de Tocqueville 1945), while others might be irrelevant. The dynamic between different types of civic organizations is important to our purposes as we wish to find out the extent to which each of these types is correlated with the several dimensions of democratic life. Our model distinguishes four content types of voluntary organizations, namely religious, professional, communitarian, and cultural18(Fig.3). Each of these four types constitutes an independent variable in our block on“social participation” (see Fig.2above). Our aim

is to see whether membership in distinct types of voluntary associations is associated with different citizenship norms and stimulates different political practices. Inspired by a wealth of evidence suggesting that arts organizations are among the most potent“schools of democracy,” we want to test whether membership in cultural associations has a significant, distinct impact in democratic politics from membership in other types of voluntary associations.

Research Design and Data Collection

Our analysis aimed to produce a rigorous quantitative documentation of the context-mediated impact of cultural membership in democratic politics. To test our model, we have used data from leading international surveys: the World Values Survey (WVS, 1999–2004 waves) and the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP 2004). The sample of our study is composed of cross-sectional observations for 42 democratic countries during the period 1999–2004. We test our model with ordinary least squares (OLS) and hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) regressions. To capture intervening factors at the country level, we used the Gini index, education (gross enrollment ratio), and cultural trade as percentage of the GDP (see Fig.2).19

18

In the case of WVS, the variables accounting for“voluntary organizations membership” are as follows: belong to community, religious, arts, and professional voluntary organizations: 1“not mentioned,” 2 “belong”; mem-bership in religious and cultural voluntary organizations in the case of ISSP 2004. We compare cultural organizations with community, religious, and professional associations because these were the main types of social organizations chosen by Putnam to illustrate his claims in Bowling Alone (see Putnam 2000, pp. 48–92). 19To account for the hierarchical nature of our data, we employed multilevel regression analysis using, for the national level, United Nations Development Programme data for the Gini index, education gross enrollment ratio, cultural trade as percentage of the GDP (seehttp://unstats.un.org/unsd/default.htm), and WVS data (membership in voluntary organizations and socio-demographic variables as controls) for the individual level. The statistical tests applied to the model used WVS data (1999–2004 wave). A slightly different model was implemented on voting as ISSP only has information regarding religious and arts groups (not on community and professional voluntary associations). Except for this difference, the same model was applied to voting. As Fig.2indicates, we included socioeconomic variables as direct effects and as moderator variables (one at a time in seven separately estimated models), three political cultures (“new political culture,” class/party politics, clientelism) and four cultural traditions (Protestantism, Catholicism, Orthodox Christianity and Eastern religions).

Most arts participation studies are local case studies, small-N comparisons, or national level analysis20(usually conducted by national authorities, such as Ministries of Culture). In turn, civil society and participation research, as far as we know, has failed to systematically explore the impact of membership in cultural organizations in democratic politics. The present research, by contrast, uses cross-national survey data because this is the only way to reconnect these two lines of inquiry– membership in cultural voluntary organizations and democratic practices and values– on a global level.

The collection of valid comparative data faced several challenges. The first concerned the availability of data: despite the growth in survey data collection in “non-western” countries in recent years, there is significantly more data for “western” societies. To measure change in arts and culture, the number of countries was reduced to those in the 1999-2004 WVS waves (and the ISSP 2004 wave for voting).21Other challenges include the potential impact of time and the identification of trends in the data; the operationalization of“thick” concepts as political cultures (e.g., the new political culture) and cultural traditions (e.g., Protestantism); and the more general reciprocity22 and omitted-variable bias. In addition, there are diverse potential threats to the reliability of measurement (e.g., Jackman 2008). We also faced operationalization challenges of all secondary analyses: limitations in geographical scope, time period, and, more important-ly, the wording of each survey item. A case in point is one of our key variables: membership in cultural or artistic voluntary organizations. The only available item in the WVS is question A066, which reads “Please look carefully at the following of voluntary organizations and activities and say…which if any do you belong to? [the list included] Education, Arts, Music or Cultural Activities.” Aware of the potential mea-surement error due to the inclusion of educational organizations like PTAs in this item, we recomputed the results for parents and nonparents of school-age children. There were minimal differences.23

Findings

We test our model of the impact of cultural membership in democratic politics in two successive steps. First, we run multilevel regression analyses in order to estimate the impact of the individual and contextual levels in predicting participation, attitudes, and norms of citizenship in democratic countries around the world. The results corroborate

20One other concern relates to the fact that in each country, the levels of culture membership are a relatively small part of the national sample. Our solution was not to conduct single country analyses, but to group countries by cultural type, which raised the Ns.

21

This is a particularly sensitive issue as we focus on a broad population of cases - democratic countries - in diverse political and/or cultural contexts. See, e.g., King et al. (2004).

22

We are aware of the potential reciprocity bias that exists in the general model we are testing—our general model analyzes if social participation impacts democratic politics, but the inverted relation might also hold. We tested this possibility and, in fact, the levels of political participation, trust, and the adherence to norms of citizenship predict membership in voluntary organizations. The variation explained by these models—measured by the adjusted R2—is inferior to our model of interest.

23

In addition, in order to test for the possible contamination of the measurement of arts participation by educational organizations we have run OLS regressions using the Citizenship, Democracy and Involvement Survey and World Values Survey data. We compared the results of our predictors of interest - only for the US (the CID questionnaire was only applied in the US):‘member: cultural or hobby activities organization’ (CID, 2005) and‘belong to education, arts, music or cultural activities’ (WVS, 1999-2004). The findings show that the results for the model with the item without reference to education (CID) do not diverge significantly from derived from the WVS: both are positive and significant predicting, in the case, protest.

our expectations: for the general model, cultural membership is the best predictor of protest activities among voluntary organization membership, alongside the educational level attained (see Tables 1 and 3). This pattern holds for the political cultures and

cultural traditions analyzed, especially in the new political culture and Protestant contexts (Table 4). This is the first dramatic result that illustrates the core point of the paper: cultural membership has far more impact than past work has identified, and it is new and powerful.24 Any new variable that rivals education is major news for survey researchers generally.

The second dramatic finding from our empirical work is most simply illustrated in a set of nine small bar charts that contrast the impact of arts participation across contexts (Fig.4).25These contexts are political cultures and world areas (specifically the seven at the base of Fig.2, like class politics and clientelism). These show clearly that the impacts

of the arts vary substantially across our contexts, five of which are graphed in Fig. 4.

These are the core findings that we interpret in the rest of the paper, discussing how and why the impacts of cultural membership vary so powerfully across the different contexts. In what follows, we focus on each specific context successively, beginning with the three political cultures—class politics, clientelism, and the NPC—and moving on to the cultural traditions, from countries whose dominant religious traditions are one of the Eastern religions to countries with a predominant Orthodox Christian, Catholic, and Protestant orientation.

The Appendixshows details of the multilevel regression analysis, plotting standard-ized regression coefficients of arts participation, by context. We computed both OLS and multilevel estimates, which are generally similar. We often refer to the regressions of the impact of four types of social participation on each component of democratic politics (dependent variables), controlling the socioeconomic descriptors (Table4). Space limits prohibit presenting all 14 tables from the two types of estimates and seven contexts. The first two of the 14 full tables are presented; the others are available upon request. Methodologically, we stress the interaction effects shown in our basic path diagram (Fig.3), especially how and why results, especially concerning the arts, vary from one

context to another. We comment on the most salient and distinctive results, especially as they vary across contexts.

Three Types of Political Culture: Different Arts Impact

We begin with the analysis of how political cultures mediate the impact of cultural membership in democratic practices and values. As noted above, political cultures are not associated with a particular set of countries. Rather, they transverse countries, regions, and cities. Individuals may well adhere to a certain kind of political culture despite (or, sometimes, because) they happen to live in a setting where other values are dominant. For this reason, we measure political cultures with survey items posed to individual citizens.26The basic question (null

24

In Table4, a clear pattern emerges from the results: cultural membership is a significant predictor of political participation, attitudes, and norms of citizenship in most contexts analyzed. Note also the coefficients for arts participation predicting Protest in Table1(new political culture context) and Table2(class politics context). In Table3, we present the results for the representative democracy component. Cultural membership is the only indicator that shows significant regression coefficients throughout the contexts.

25We also implemented a test of between-subjects effects to see if each context had a different effect on each of our dependent variables. Result: they indicated a significant context effect (for example, impact of different political cultures on protest: F(2, 52,979)=31.86, p<0.001).

26

hypothesis) here is: to assess the political implications of my membership in a cultural organization, does it matter which sort of basic values regarding social and economic change I subscribe to? Our findings indicate impact (Fig. 4). In some political cultures, cultural

membership fosters certain democratic practices and civic norms, while promoting different ones in others.

Class Politics

Consider the class politics context. This context is ideal—typically characterized by hierar-chical institutions (the Church, political parties, and unions), materialist values (related to security and economic development), and a model of citizenship defined by the fulfill-ment of civic duties such as serving in the military and paying taxes and receiving class-party-driven state benefits. Our aim here is to discuss how and why belonging to a cultural organization influences political beliefs and conduct in this specific context. We build on recent work on class politics such as Evans (1999), Clark and Lipset (2001), and Achterberg (2006).

The most interesting finding here is that cultural membership increases voting turnout (Table3). This is the only context in which this happens. Why does arts participation in class

politics contexts lead one to vote, while it suppresses voting in other contexts? A political cultural explanation is that in class politics contexts, the“rules of the game” distinctly favor turnout more than in other contexts. The role of collective organizations in mobilizing turnout seems key: unions, stronger political parties, and civic groups closely tied to political parties. These are the classic organizations that mobilize voters in cities and countries with stronger class politics, like the Scandinavian countries and, in the past, most Southern European countries and Latin America (e.g., Verba, Nie, and Kim1978). These organizations remind their members that voting is important, discuss elections in meetings and newsletters, often monitor who has not voted on election day, then visit individuals to remind them to vote, and drive them personally to the polls. This highly labor-intensive campaign work is ideologically consistent with the collective ethos of labor/left party/collective church traditions. These have traditionally also been the largest and best staffed organizations involved in electoral politics. They are stronger on the left/popular side than among conservative parties in most class politics societies (Clark and Hoffman-Martinot1998). Here, more institutional forms of political participation, like voting and political campaigning, are conceived of as legitimate, effective means of exercising and claiming citizenship rights, no less than protest activities themselves, hence the positive associa-tion of cultural membership with both voting and protest in class politics contexts (Table 2).

If, in materialist class politics contexts, cultural membership seems to foster turnout, the same is not true of other aspects of democratic politics. One such dimension is trust, both in other persons and in the government: in both cases, the impact of arts participation is not significant. Similarly, class politics contexts seem to act as a sort of“buffer zone,” which limits the impact of cultural membership on the norms of citizenship: under class politics, this impact is weaker than in most other contexts. By contrast, the impact of more hierarchical civic organizations such as the Church is strong in this context: it is a significant predictor of both the duty-based and of the identity norms of citizenship, as well as of social and political trust. Cultural membership in class politics contexts, dominated by hierarchical institutions and materialist concerns, seems to have somewhat mixed political consequences—if it fosters voting (and, to a lesser extent, protest), its impact in other dimensions of democratic life is negligible compared to other predictors.

Clientelism

Empirically often overlapping class politics, clientelism is a second political culture whose mediating influence between arts participation and democracy we wish to test.27 Cultural membership here has markedly different political consequences than in NPC and class politics. Two results immediately distinguish clientelism. First, cultural membership is here associated with duty-based and identity models of citizenship. In the other cultural contexts, artistic voluntary participation tends to“prevent” one from equating citizenship with serving in the military or paying taxes, a duty-based understanding of the civic bond. However, in a clientelist political culture, this relation becomes positive—here if one is a member of, say, a book club, one is more likely to endorse duty-based norms of citizenship. Confirming the general legitimacy of duty in this political culture, the duty-based norm is affirmed by respondents higher in education, income, and membership in professional associations. In addition,thisistheonlycontextinwhichbelongingtoanartsassociationispositivelycorrelated withanidentitaryunderstandingofthepoliticalbond.28Thisflows,webelieve,fromthestrength of personalistic ties in a clientelist context, affirming its impact even as deeply as one's personal identity.Second,ifonebelongstoanartsorganizationinaclientelistcontext,itisnotmorebutless likelythatthecitizenwilltakepartinmanifestationsorotherprotestactivitiesandendorseanorm of citizenship associated with rights claiming (Table4).29

These two results combined are nothing short of remarkable. Attesting to the importance of context, these are clear examples of how the same social practice (belonging to a cultural organization) can entail profoundly different political implications. These findings powerfully reinforce our general point that the experience of belonging to a cultural organization acquires distinct political meanings in different contexts: of all political cultures discussed in this paper, clientelism is the only one in which the impact of cultural membership on protest activities, as well as on the engagement and the legal-civic norms of citizenship, is negative. This reverses in the next context.

New Political Culture

In a new political culture context, not only is the impact of cultural membership on protest activities positive, its impact is also the strongest among all political cultures (Table4).30Why? Recall that the NPC is an emerging political culture that combines socially liberal attitudes (say, a pro-choice position) with a fiscally conservative agenda. As such, the citizen-oriented individualism associated with post-materialism tends to reject the hierarchical and bureaucratic state apparatus. This egalitarian individualism seems to be a contributing factor for the predisposition of individuals engaged in cultural activities, more than in class politics or clientelist contexts, to engage in elite-challenging activities. In other words, if one is critical of big government and supports gay marriage, while being a member of a poetry reading club, 27Clientelism is a context constructed not from information obtained by means of cross-national surveys (which did not include“clientelist” items), as in the case of the other contexts, but from national information gathered by the World Bank.

28

Standardized regression coefficients (arts membership in clientelist context predicting solidarity norm of citizenship):β=0.098 (p<0.001).

29Standardized regression coefficients (arts membership in clientelist context predicting protest, engaged norm of citizenship):β=−0.029 (p<0.001), β=−0.037 (p<0.001).

30NPC contexts show significantly higher impacts of cultural membership than of the other types of apolitical associations on protest activities. This holds true for the three political cultures, NPC, class politics, and clientelist, where cultural membership is a better predictor of protest than any other type of organizational participation (religious, community, or professional).

this will probably translate into political terms as a predisposition to, say, sign petitions and to adopt a rights-claiming attitude. Interestingly, it will not foster as much trust in other persons as in the government. These findings not only corroborate past work suggesting that social and political trust are different attitudes explained by different variables (e.g., Coleman 1988; Newton2001), but also reflect the nature of this specific political culture, i.e., a combination of socially liberal attitudes with fiscal conservatism that is particularly salient in large, cosmo-politan urban settings (e.g., Boshcken2003).

Four Cultural Traditions/Civilizations

Our focus so far on political cultures could lead some to consider either that behind our model lies some sort of evolutionary framework, guiding the analyst from the class politics and clientelism of the past to the NPC of today's global cities and cosmopolitan democrats, or that we are solely concerned with the socioeconomic processes of societal change. Both inferences would be wrong. Although we do not deny the profound impact of socioeconomic change in individuals' attitudes and practices, we also attend to possible effects of“civilizations,” broad sociocultural religious patterns. In addition, we do not equate modernization with westerniza-tion, i.e., the gradual diffusion of western values and institutional solutions across the globe. Our understanding of modernization processes, on the contrary, is that of a plurality of appropriations and reinventions of the original, western European modern project. These responses to modernity can be seen as expressions of different civilizations. This is why, in addition to political cultures associated with socioeconomic change, our model includes cultural–civilizational traditions. Their religious–cultural cores are not reducible to socioeco-nomic concerns (Eisenstadt2008). Here, cultural traditions refer to the religious-based cultures that have been historically predominant in each country. As such, cultural traditions refer to specific groups of countries.31Our findings below thus concern the mediating role of some of major cultural traditions for the impact of arts membership on democratic politics (Fig.4and Table4).

Eastern Religions

A major cultural tradition is formed by eastern religions, which include, among others, Buddhism, Taoism, and Confucianism.32In the countries where these cultural traditions are predominant (South Korea, Japan), or at least occupy a prominent position (India), the central finding is the individualist and engaged political repercussions of cultural membership. Korean reading club members, for instance, are more likely to engage in protest activities and endorse a model of citizenship that emphasizes engagement. And the more educated they are, the more likely this is to occur.33Furthermore, cultural membership seems to be part of an expanded scope of individuality at the expense of solidarity. First, cultural membership

31

Using religion as a prime historical indicator of traditional basic values and culture is classic in social science, from Max Weber's works on sociology of religion (1958, 1964) to Talcott Parsons (1951), to Henri Mendras (1971), and even Daniel Bell (1973).

32Due to data availability, this last context is analyzed only for three countries (India, Japan, and South Korea). Future waves of the World Value Survey and similar cross-national surveys should try to enlarge the number of countries from this part of the world.

33

“More educated” refers here to the positive and statistically significant regression coefficient correspondent to the direct effect of the variable predicting the dependent variables (concerning the highest level of education attained by the respondent).

in this context decreases one's solidarity towards the worst-off. Second, and more important, of all cultural traditions, this is the only one in which to belong to a chorus society or a theater group is unrelated to increased trust in other individuals. In these countries, the sources of social trust are elsewhere, namely in a left-wing ideological stance, higher income, and being older.

Orthodox Countries

Moving now to majority Orthodox Christian countries, namely Bulgaria, Romania, Moldova, and the Ukraine, one cannot ignore the fact that all were under communist rule for much of the second half of the twentieth century. The most striking result concerning the political impact of cultural membership here is its passive outlook—something not be found in any other context. There is no correlation between, say, being a member of a chorus in Romania and endorsing a rights-claiming conception of citizenship rights. Similarly, cultural membership has the least impact on protest activities. Furthermore, signaling perhaps a divorce between arts participa-tion and instituparticipa-tional politics in this context, the only kind of trust promoted by this specific sort of social participation is social, not political trust (Table 4). The impact of religious membership, in turn, is almost residual in these Orthodox countries: there is only a weak negative correlation between this sort of social participation and the duty-based norm of citizenship, perhaps attesting to the more complex role of religion combined with the com-munist past.

Catholic Countries

Consider next the two cultural traditions historically most influential in western democ-racies—Roman Catholicism and Protestantism. In majority of Catholic countries, a cultural tradition that includes Southern European and Latin American countries,34the political impact of cultural membership assumes yet another configuration. The most salient finding is the anti-hierarchical and libertarian political meaning, absent in NPC or Protestant contexts. Two results illustrate. First, cultural membership is negatively correlated with voting (Table3).35This is noteworthy insofar as this is the only context in our study where this occurs: in all other contexts, cultural membership fosters voting and political campaign work. And only in NPC contexts is belonging to an arts association more strongly correlated with joining a demonstration or signing a petition than in Catholic countries (Table 4).36 Second, turning to political beliefs, cultural membership is negatively correlated with the duty-based norm of citizenship: if I belong to, say, a theater group in Spain, I will more likely reject equating citizenship with paying taxes and identify it instead with street demonstrations.37

These are among the most interesting and unexpected findings our model has pro-duced. We have already seen how contexts such as the NPC, class politics, or clientelism shape the political consequences of cultural membership. The significant differences

34

The complete list of major Catholic countries included in our analysis is Argentina, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, Croatia, Czech Republic, El Salvador, France, Hungary, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, and Uruguay.

35Standardized regression coefficients (cultural membership predicting voting):β=−0.028 (p<0.001). 36Standardized regression coefficients (cultural membership predicting protest):β=0.057 (p<0.001). 37

Standardized regression coefficients (cultural membership predicting duty and engaged norm):β=−0.047 (p<0.001) and 0.025 (p<0.001).

found among all these contexts share one thing—they are consistent with the cultural patterns38 prevalent in each context. But Catholicism seems to enhance a different contextual effect: the political impact of cultural membership is not consistent with the broad cultural traits of the Roman Catholic Church, but a reaction to them. Following this interpretation (not unique to us, except for the arts data), the anti-hierarchical and libertarian political consequences of cultural membership is an indication that members in cultural associations in countries like Spain, Portugal, or Poland find in these organi-zations an outlet providing a critical distance from the socially conservatives of the Catholic tradition.

Protestant Countries

Several Catholic effects reverse in majority Protestant countries.39Here, increased support for protest activities,40for engagement and legal-civic norms of citizenship, and for increased social and political trust,41 arts participation shows positive impacts—all in line with Protestantism's cultural legacy. That is, principles like individual autonomy and personal expression not only support norms of citizenship and types of political participation empha-sizing critical engagement and creative self-realization, but they give this cultural tradition a distinctive flair. It differs from NPC contexts, for example, in that individuals in Protestant countries joining cultural organizations are even less likely to associate citizenship with serving in the military or paying taxes. And it differs from class politics in that political impacts of cultural membership are substantially stronger. Imagine a literary club member in the Netherlands. Our findings suggest that he would be significantly inclined to conceive of citizenship as claiming rights. He would also strongly reject civic models associated with fulfilling duties or showing solidarity for the most vulnerable members of society.42But now consider that our imaginary Dutch bibliophile has a materialist, class politics orientation. In this case, as we saw above in considering the buffer zone effect of class politics, the political impact of his cultural membership would be much weaker. To sum up, belonging to a literary club or a choral society in a Protestant country makes one more prone to trust other fellow citizens and the government, to object to models of citizenship based either on the fulfillment of duties or in solidaristic values, while supporting protest activities and norms of citizenship based on a legal-civic, rights-claiming understanding of the good citizen.

This makes the Protestant cultural tradition different from all the others considered so far. In Catholic countries, cultural membership is associated with anti-hierarchical attitudes and prac-tices; in Orthodox countries, it promotes social trust; in Eastern religious countries, it has individualistic and engaged political implications; in NPC contexts, it is linked to protest activities and the engagement norm; in class politics contexts, to voting and political campaign; and in clientelist settings, to the duty-based and identity citizenship norms. One type of social partici-pation, seven cultural contexts and seven different political consequences, if put in a word, would

38“Cultural determinants” refer to structural features of each context, in the sense of Raymond Boudon's “operative” definition of structure (see Boudon1971).

39

The complete list of major Protestant countries in our analysis is Australia, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Iceland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, Great Britain, and the USA.

40Still, it has to be said that the sources of political trust are conservative and hierarchical, i.e., low income, right-wing self-positioning, and belonging to a religious organization most increase trust.

41Standardized regression coefficients (cultural membership predicting protest activities, social trust, and engagement norm of citizenship):β=0.029 (p<0.001), β=0.056 (p<0.001), and β=0.023 (p<0.001). 42

Standardized regression coefficients (cultural membership predicting duty and solidarity norms of citizenship): β=−0.057 (p<0.001), β=−0.056 (p<0.001).

be culture matters. Culture matters, first of all, because it is on the rise globally. Culture matters also because of all types of voluntary associations here considered, cultural membership has the most significant political impacts. And culture matters further in that these political impacts are is significantly mediated by different political cultures and cultural–civilizational traditions. These last two findings combined seem to vindicate our efforts at building a theoretical model of the political meaning of the rise of culture, i.e., how and why, in multiple contexts around the globe, is cultural membership associated with democratic values and practices.

Conclusion

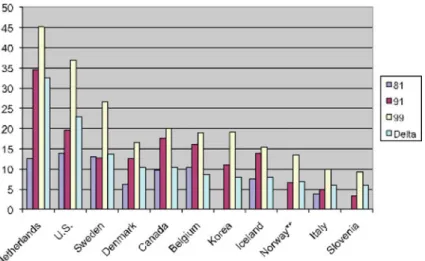

This paper documents the rise of culture and arts participation as a dramatic exception to the widely held view that we are increasingly bowling alone, i.e., that civic activity is declining. In the Netherlands, the USA, Canada, and Scandinavia, arts and culture participation has tripled or doubled from 1981 to 2004. Our finding derives from examining civic participation items for issue specificity, rather than implicitly assuming that issues are not distinct (the working rule of most participation research). We next explored interrelations between arts and culture participa-tion and several measures of democratic politics, finding that they vary considerably by context. This sharply contradicts and qualifies the generality of the Tocqueville/Putnam hypothesis. The core of the paper interprets differences by context. As far as we know, this is the first attempt to identify and discuss the political consequences of cultural membership on a global scale.

The implications for democratic politics of nonpolitical associational life are a classic theme in the social sciences. Using survey-based cross-national data, we analyzed specifically the impact of being a member of a cultural organization on various indicators of democratic politics—from practices like voting or protest, attitudes toward political institutions, to beliefs regarding citizenship. Our specific findings bolster the hypothesis that the recent rise of culture has important political consequences. These consequences, however, are neither limited to a certain component of democratic politics—say, the representative democracy component vs. elite-challenging activities—nor are they homogenous across contexts (transnational or country level). Our model has shown how the impact of cultural membership on the different compo-nents of democratic politics is profoundly shaped by the concrete cultural contexts in which individuals live. While in some it drives one away from traditional party politics, in others, it has the exact opposite effect, leading one to vote and participate in political campaigns.

Besides significant political implications, the rise of culture also has important policy implications. As local governments around the world have shown since the mid-1970s, policy innovation in the arts and culture is a powerful political instrument: from the strategic electoral use of humor and irony to ambitious municipal plans of urban renovation associated with cultural events or institutions, in such disparate locations as Bogota, Colombia, Naples, Italy, or Chicago, USA, there is overwhelming evidence of the rise of culture in local policy making.43 Bogotá, Naples, and Chicago are among the many sources of a new style of leadership and citizenship, new modes for engaging citizens that often conflict with the Tocqueville-Putnam tradition. Rather than focusing on the Kiwanis Club or the League of Women Voters, mayors in Naples, Chicago, and especially Bogotá have developed highly popular, symbolic leadership, joined in specific actions, as alternative modes of governance that work (instead of the classic civic group). These alternative modes of urban governance work in part since they are founded on a base of distrust, alienation, and cynicism that makes the Tocqueville model distinctly more

43

The importance of arts and culture in contemporary urban policy is discussed in the very recent work of Grodach and Silver (2012, p. 13).

difficult to construct. In the last few years, we have collaborated with several Latin Americans, Italians, and Spaniards to document and generalize the lessons from Bogota, Naples, and even Chicago in a manner that they might be applicable to situations such as the civic vacuum found in Mexico City as well as some LA (and Chicago) neighborhoods. From this perspective, UN-supported initiatives like the 2004“Agenda 21 for culture” are but a high-level, institutional response to the accumulated experience of dozens of local government initiatives around the world that had been using arts and culture to foster social, economic, and political development for decades.

Culture and arts participation should be taken seriously for all the above reasons. More people have life experiences shaped by it; as “schools of democracy,” to paraphrase Tocqueville, cultural organizations nurture a wider range of civic virtues than most other types of associations surveyed, at least the standard types in the World Values Surveys; and one can only begin to understand the political significance of the rise of culture if cultural diversity is adequately accounted for. There are then good reasons to place culture high on the research agenda of the social sciences.

Acknowledgments Thanks for advice and data analysis assistance to Rita Costa, Cátia Nunes and Jonah Kushner, and Scenes Project participants at the University of Chicago. Direct correspondence to Terry Clark, University of Chicago, 1126 E. 59th St. #322, Chicago, IL 60637, USA; Filipe Carreira da Silva, ICS-UL, Av. Aníbal de Bettencourt 9, 1600-189 Lisboa, Portugal.

Appendix

Fig. 1 Rising membership of cultural activity groups. Note: Percentage of individuals in each country sample who belong to education, arts, music or cultural activities organizations in each WVS wave and total variation (1981–1984; 1989–1993; 1994–1999)

Fig. 2 Path diagram of core model. Note: The paths show direct effects from the two boxes of variables on the left hand side. The bottom boxes with their paths leading to circled arrows indicate interaction or mediated effects, which shift the paths from the left hand side. How and why these mediated effects differ is the main focus of subsequent sections of the paper

0.00 1.00 2.00 3.00 4.00 5.00 6.00

Arts Community Religious Professional

Membership in voluntary organizations

(WVS 1981-2004, variation, mean)

Fig. 3 Membership in voluntary organizations, 1981–2004. Note: Comparison of levels of membership in voluntary organizations (question:“Please look carefully at the following list of voluntary organizations and activities and say… which if any do you belong to?”). WVS data (1981–1984 and 1999–2004 wave)

Table 1 Multilevel regression analysis: predictors of democratic politics (new political culture context) Participation Attitudes Norms of citizenship

Protest Trust: political institutions

Social trust

Engaged Duty Solidarity Civic

Level 1 Sex (female) −0.042*** 0.049 0.075* 0.014 0.012 −0.041 0 Age 0 −0.026 0.066* −0.016 −0.007 0.028 0.012* Educational level 0.125*** 0.001 0.040 −0.07 −0.003 0.070 0.007 Income 0.030*** −0.013 0.038 −0.09 −0.002 0.002 0.005 Community 0.009* −0.002 −0.010 −0.004 0.011* −0.004 −0.004* Religious −0.013* 0.007 −0.035 0.005 −0.003 −0.001 −0.003 Arts 0.048*** 0.046 0.012 0.006 −0.005 0 0.003 Professional 0.027*** 0.002 −0.009 0.003 0.007* −0.004 −0.005* Level 2 Gini index −0.08* 0.163 0.058 −0.005 −0.031 −0.091 0 Education (gross enrolment ratio) 0.15*** −0.127 −0.025 0.014 −0.016 0.049 −0.001 Cultural trade as % of GDP 0.02 0.033 0.034 −0.001 0.015 −0.014 −0.003 Intercept 1.324 0.623 0.836 1.998 2.576 2.421 1.583 (St. error) (0.141) (0.859) (0.117) (0.130) (0.527) (1.620) (0.219) Intra-class correlation 0.18 0.51 0.002 0.04 0.27 0.57 0.02 Variance component (level 1) 0.201 0.575 1.566 1.998 0.696 1.720 0.667

The values presented are standardized regression coefficients. Level 1 = individual citizen/respondents, data source: World Values Survey (1999–2004 wave); level 2 = aggregate (nation) level, data source: United Nations Development Programme and UNESCO. Software: HLM 6.02. N1 minimum=42,625 citizen respondents in 42 countries