Bull Pan Am Health Organ E(4), 1978.

AN APPROACH TO UTEJZING HEALTH AUXILIARIES

IN DIJXECT PATIENT CARE’

Paul A. Nut&g: Dean F. Tirador? and Audra M. Pambrun3

This article describes a methodology for defining the health auxiliary’s role, sfieczyic tasks, and relationshi@ to the rest of the health system. For several years this methodology has been tested in a pilot program by the United States Indian Health Service. Results to date indicate that this test program has produced significant beneficial results.

Introduction

It has been estimated that 80 per cent of the people in the developing world have extremely limited access to health services. ’ Many-or even most-of the underserved

groups reside in rural areas where they are faced with poverty, malnutrition, exposure to disease, and ignorance concerning the causes of illness and the availability of preventive measures. There is a growing consensus among government and interna- tional organizations that health care ap- proaches taken directly from patterns prevalent in industrial nations are inappro- priate to the needs and circumstances of these groups. The development of sophisti- cated health delivery systems staffed by highly qualified personnel has not signifi-

~11y improved health care for rural populations, and even in marginal urban populations the services provided have been episodic and mostly curative in nature. The cost of training, supporting, and maintain- ing a physician-combined with the diffi- culty of retaining him in an isolated area- makes this approach impractical for scatter- 8 ed rural communities.

IAlso appearing in Spanish in the Boletfn de la Oficina Sanitaria Panamericana, 1979.

ZAssociate Director, Office of Research and Develop- ment, Indian Health Service, United States Public Health Service, P.O. Box 11340, Tucson, Arizona 85734.

SHealth Applications Section, Office of Research and Development, Indian Health Service.

Among the various approaches that have been studied and used to extend primary health care services to rural areas, that of employing auxiliary health workers in a variety of roles has received strong empha- sis. The advantages, requirements, prob- lems, and constraints of this approach are summarized well in two recent WHO publications (I, 2).

Health auxiliaries have long contributed to health promotion activities. They also have a long history of helping to deliver medical services-principally as workers in hospitals or clinics under the direct and continual supervision of health profes- sionals who structure their activities and specify which tasks are to be performed for a given patient.

Auxiliary workers have also play& an important role in direct patient care activi- ties linked to mass campaigns such as those against yaws and malaria. While such workers may not be subject to constant on-the-spot supervision, the mass campaign structure within which they function is well-defined. The nature of the mass campaign usually dictates the required tasks, defines those tasks, and specifies their frequency. Special arrangements are made for supervision. If a need for referral is foreseen, potential referral facilities are usually alerted.

order, and frequency of the tasks to be performed for a given patient. In this role the auxiliary serves as the entry point into the health care system and directs certain individuals to and through other skill levels of the system according to their individual needs.

The Indian Health Service of the United States Public Health Service has primary responsibility for the health care of about 750,000 American Indians and Alaskan Natives, most of whom live in isolated rural communities. With a fixed budget, an obvious need to maximize the effectiveness of the health services provided, and a concurrent commitment to increase commu- nity involvement in managing and manning community health programs, the Indian Health Service has placed great emphasis on developing the roles of village health workers (3-6).

The Office of Research and Development of the Indian Health Service has actively sought to develop a methodology for effec- tively utilizing tribal health personnel in direct patient care. This has meant develop- ing potential roles through a process of “staging” target health problems, defining criteria for clinical problem-solving, and applying these criteria in the field. This paper describes the methodology involved and summarizes results drawn from approx- imately four years’ experience.

Health Problem Selection: Defining the Auxiliary’s Role

What health problems are selected and how the auxiliary is assigned to deal with them should depend on the health care system’s operational goals. If a major objective is to shift a portion of the existing workload from the professional to the auxiliary, problems causing frequent com- plaints or visits to health professionals should be selected. In our experience, eight

ly 50 per cent of the ambulatory care work- load generated by a community (7).

If a major objective is to promote conti- nuity in caring for chronic disease patients, then another set of health problems should be selected. Our experience indicates that a relatively large number of patients with chronic conditions are diagnosed, placed on therapeutic regimens, and then lost to follow-up for an indefinite period of time, resulting in very little benefit to those patients (8). Here a worthwhile health auxiliary role is to manage such patients for an indefinite period, referring each back to the professional when the prescribed therapeutic regimen is no longer adequate. If a major operational objective is mor- bidity prevention or early identification and intervention in the disease process, then selection of health problems should be based on the estimated incidence and prevalence of diseases in the community. Again, in our experience, some small number of health problems-on the order of eight to lo-will usually account for a significant share of community morbidity and mortality.

To define the health auxiliary’s role in dealing with the health problems selected, one must consider the clinical health care functions to be performed; to sim- plify matters, these functions can be classi- fied as prevention, screening, diagnostic evaluation, treatment planning, and on- going management. In addition, the auxil- iary’s role can be defined for each health problem in terms of available technology and the operational objectives, capabilities, and limitations of the total health care system.

Health Problem Staging

“Staging,” the process of definingdiscrete stages in the development of a health problem, serves several useful functions. For one thing, it supports program plan- ning by identifying points of potential pro-

284 PAHO BULLETIN l vol. XII, no. 4, 1978

Nutting et al. . METHODOLOGY FOR USING HEALTH AUXILIARIES 285

specific standards can be formulated for each step (including information gathering,

assessment, and treatment4 ) of the problem- solving process.

Staging also enhances program operation by providing a common procedure-one shared by all professional and nonprofes- sional health team members-for deter- mining the severity of a given health prob- lem. In this manner, staging enables the health auxiliary to gather the necessary in- formation, to determine the stage of severity of the problem, and to provide a response appropriate for that particular stage. De- pending on the stage involved and its pre- scribed standard of treatment, the auxilia- ry’s response may consist of a combination of direct treatment, referral to a health professional, and/or follow-up activities. Thus a health system comprised of person- nel whose skill levels differ and who work at different locations is able to maintain an appropriate and consistent response for each stage of problem severity.

Finally, problem staging provides an opportunity to evaluate program effective- ness by measuring patient movement from stage to stage. Such movement can be expressed in terms of the rate of transition from one stage to another.

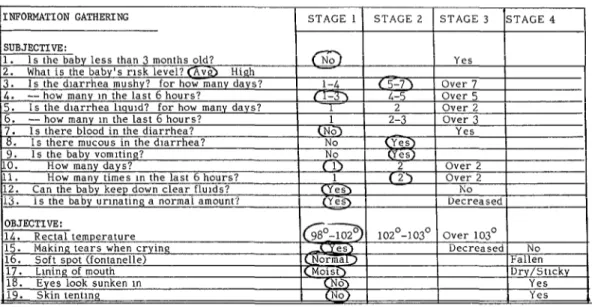

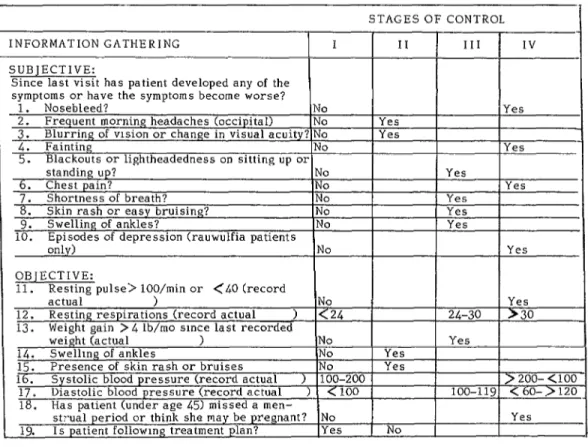

For any given health problem, the num- ber of stages listed and the information required to determine the particular stage involved should depend on the operational objectives sought. Figures 1 through 4 illustrate staging procedures designed to satisfy four different operational objectives.

In all instances, the stage of any given disease case is found after first gathering all necessary items of information and circling a response category for each item, as shown in Figure 1. The stage of the case is then considered to be the highest stage with a circled response.

4Treatment, as defined here, includes referral and follow-up.

The staging mechanism shown in Figure 1 is designed to support a strategy of early intervention in gastroenteritis cases among children under three years of age. In this case the staging process defines discrete stages of clinical severity but does not define the etiology of the illness (whether it is viral, bacterial, parasitic, etc.).

The staging mechanism shown in Figure 2 is one of a series of mechanisms designed to shift some of the work involved in caring for schoolchildren with minor acute prob- lems from a health professional to a school employee. In this case only two stages are defined: Stage I, the category for mild cases that could be managed with symptomatic treatment by school staff members; and Stage II, the category for cases with more severe symptoms, including cases where more severe illness should be suspected and should be referred to professional health personnel.

Figure 3 shows a staging mechanism designed to guide an auxiliary in providing ongoing management for chronic disease patients. In this case the diagnostic evalua- tion and treatment are performed by a health professional and the patient is referred to the health auxiliary for long term management. This process defines stages of control of the disease process and reflects the presence of drug side-effects and patient compliance with the therapeutic regimen: but again, it does not reflect etiology.

The staging mechanism shown in Figure 4 is designed to help a mental health aux- iliary prevent school dropout behavior in boarding school students. Here the staging process defines behavioral problems that are considered antecedents to dropping out of school. In a sense, the process defines levels of risk-how likely a student is to become a dropout-but does not specify any etiology or level of severity for the target health problem per se.

286 PAHO BULLETIN l vol. XII, no. 4. 1978

Figure 1. Staging mechanisms for gastmenteritis in children under 3 years of age.

I

IWORMATION GATHERING 1 STAGE 11 STAGE 2 1 STAGE 3 ISTAGE 4 SUBJECTIVE:1. 1s the baby less than 3 months old? What is the baby’s risk level? @,vb H

Is the diarrhea mushy? for how many d

I

13. Is the baby urinating a normal amount? ( (Ye3) ( Decreased 1I I I

Figure 2. Staging mechanism for a minor acute problem of school-age children (abdominal pain).

STAGE I STAGE II

SUBJECTIVE:

Nature of the pain Mild Moderate/Severe

: z

Vomiting more than once in 4 hrs? No Yes

W

F

Duration of pain Less than2 hrs 2 hrs or more 2 Having menstruation or expecting it soon? No/Yes -- 5

Having vaginal bleeding more than normal menstruation?

Ir’

z Less menstruation? 5 OBJECTIVE:

LL Z

H Temperature

No Yes

Less than 2 mos 2 mos or more

Less than 100’ 100’ or over

Nutting et al. l METHODOLOGY FOR USING HEALTH AUXILIARIES 287

i-

Figure 3. The staging mechanism for on-going management of a chronic disease (hypertension).

STAGESOFCONTROL

NFORMATION GATHERING 1 II III

‘UBJECTIVE:

;ince last visit has patient developed any of the

IV

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes 330

> 200- (100 < 60->120 . Yes

Figure 4. The staging mechanism applied to behavioral problems of the school-age child.

going home NO --- Yes ---

12. Vlslt to review board or juvenile city court No --- -- Yes

13. Threats or attempts of suicide No --- Yes ---

288 PAHO BULLETIN . vol. XII, no. 4, 1978

with the auxiliary’s increased experience and with changes in the health service delivery system.

Tasks and the Task Structure

Training a health auxiliary and placing him within a community does not, by itself, provide the basis for an integrated community health care system. Regardless of the auxiliary’s training and the various specific tasks he can perform, a significant number of patients will require further assessment or treatment beyond his capabil- ities. Another complication is that when a patient’s condition requires two or more tasks (often separated in time), the auxilia- ry must not only be able to select the appro- priate tasks, he must be able to perform them in the correct sequence and at the proper intervals. Therefore, it is necessary to define both task sequences and the func- tional relationships between the auxiliary and the next level of the health system. We have called this defined pattern of task sequences and relationships the task struc- ture.

The task structure should provide clear answers to at least six questions:

1) Who has primary responsibility for ger- forming the task? Within the scope of the

present discussion, this will always be the health auxiliary.

2) Who has secondary resfionsibility for $er- forming the task? This is the person who will

periodically monitor the auxiliary and to whom the auxiliary can turn if he has a question about task performance.

3) For what po#ulation should the task be performed? The target population and the characteristics of specific priority groups, if applicable, should be defined. For example, if the task is designed to screen for iron deficiency anemia, the target population might include all pregnant women, and a specific priority group might include those women who are gravida IVs or higher.

4) When and how often is the task to be performed? Specifically, the time to start a task, how often to perform it, and the time to terminate it should be defined. For example, a

DPT immunization series should begin at age two months, should continue with immuniza- tions every two months, and should end after three immunizations have been given.

5) What additional tasks should follow, on the basis of results obtained with the one per- formed? In order to promote health care conti- nuity it is critical to define what action or actions should be taken as a result of the outcome of each task. In the case of a screening task, for example, the task structure must specify the rescreening, treatment, or referral tasks that should follow a particular screening result.

6) How are the resuEts of the task to be Tefiorted? It is important to define the manner in which the auxiliary reports information derived from the task to other parts of the health care system. Such reporting may be accomplished by telling someone the result, by filling out a form, etc.

Besides spelling out the answers to these questions, the task structure may need to specify the equipment that may be required for certain tasks, where certain tasks should be performed, and the nature and frequency of certain patient education activities which may be an integral part of patient care. An example of a given task (assessment of the severity of gastroenteritis) and its associated task structure is shown in Figure 5.

In our experience, defining a task and its associated task structure is not easy. This is mainly because one is forced to deal with small details which could easily be over- looked. However, if each of the foregoing questions has not been addressed in the planning phase, and if the task structure has not been included in the auxiliary’s training curriculum, then it is difficult for the auxiliary to function effectively as an extension of the health care system. The job of defining the task structure therefore tends to create needed discipline within the planning process.

Nutting et al. l METHODOLOGY FOR USING HEALTH AUXILIARIES 289

Figure 5. Task structure for assessing the severity of gastroenteritis in children the age of 3 years.

TASK A: Assessment of Severity - Gastroenteritis PRIMARY RESPONSIBILITY: CHR

SECONDARY RESPONSIBILITY: CHR Supervisor TARGET POPULATION: Children, Age O-3 years

PRIORITY GROUP: Infants (Age O-l year) TIMING: Each time child with gastroenteritis is seen DOCUMENTATION: Record on Protocol

TASK SEQUENCE: If Stage I, do tasks B, C If Stage II, do tasks B, C,H If Stage III, do tasks D, E If Stage IV, do tasks D, F EQUIPMENT: Thermometer

Protocol

LOCATION: Patient’s home

ACTION STEPS:

1. Gather the following information: - Is the baby less than 3 months old? - Is the diarrhea -~ Mushy? Liquid? - Mushy diarrhea - for how many days?

- Mushy diarrhea - how many in the last 6 hrs.? - Liquid diarrhea - for how many days?

- Liquid diarrhea - how many in the last 6 hrs.? - Is there blood in the diarrhea?

- Is there mucous in the diarrhea? - Is the baby vomiting?

- For how many days?

- How many times in the last 6 hrs.? - Can the baby keep down clear fluids? - Is the baby urinating a normal amount? 2. Take rectal temperature

3. Check tearing of eyes, fontanelle, lining of the mouth 4. Check for tenting of the skin, and sunken appearance of eyes

5. Record items l-19 on protocol by circling the appropriate response categories

6. Determine the patient’s stage by noting the highest stage with eveb one circled response 7. Document staged assessment on recording protocol

290 PAHO BULLETIN l vol. XII, no. 4, 1978

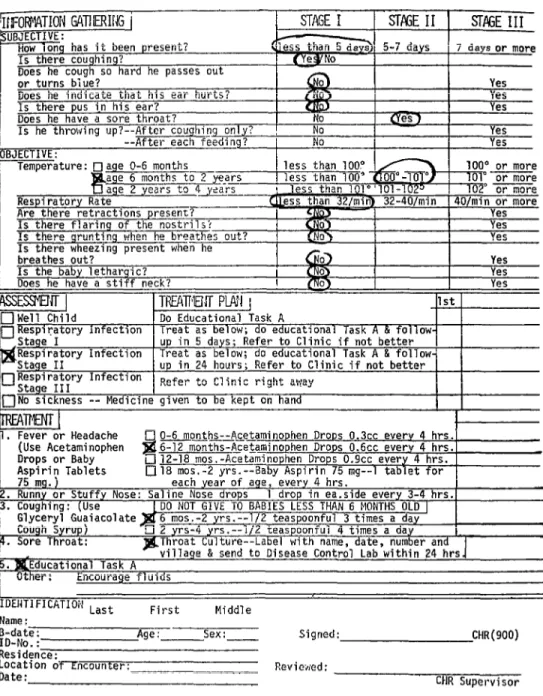

Protocols

The effectiveness of nonprofessional health workers has been enhanced by using protocols designed to guide their activities in accord with appropriate standards of care (9-13). Figure 6 shows a protocol for handling respiratory infections in children O-4 years of age. Employing the staging mechanism shown in Figure 1, the protocol guides the auxiliary through the assessment process by defining stages of clinical severity. For each stage of severity, the protocol specifies a plan of treatment and follow-up; and for those cases where medication is indicated, the appropriate age-specific dosages of medication are described.

This protocol enhances program opera- tion in several ways. It provides explicit instructions for the auxiliary by defining the necessary care as a sequence of tasks. It then guides the auxiliary through the problem-solving and treatment process, and in so doing formalizes functional linkages with the rest of the health care system. The protocol also reduces the documentation needed to show compliance with clinical care criteria to a series of circled items and checked boxes; it thus permits easy monitor- ing of health workers’ compliance with the desired standards of information-gathering,

assessment, and treatment. The documenta- tion of staged assessments and planned treat- ments also provides the basic information needed to evaluate the program’s impact. Finally, a copy of the protocol, which accompanies the patient if he is referred to the next level of the system, makes relevant information available to other members of the health team.

Monitoring Performance

Auxiliaries located in scattered rural communities are not readily accessible to

standard supervision, a fact which has often impeded their maximum utilization. Clearly supervision -plus provision of re- fresher training and continuing education as needed-is imperative in order to assure quality performance and to maintain a sense of job satisfaction. For this reason a supervisory mechanism is needed which makes the most of infrequent contact between the auxiliary and his supervisor, and that allows the auxiliary to judge his own performance and refer himself in for refresher training. Although there is no entirely suitable supervisory mechanism which meets both requirements, we have found that a significant amount of per- formance monitoring can occur without face-to-face contact. By having the auxilia- ry send a copy of the protocol to the supervisor, the latter can see at a glance whether all the required items of informa- tion were collected, the correct assessments made, and the treatment plan employed that corresponded to the assessed problem stage. The accuracy of the data collected and the adequacy of the educational tasks performed, of course, cannot be deter- mined from the protocol. These are judge- ments of personal performance that can only be made from frequent direct observa- tion.

Nutting et al. l METHODOLOGY FOR USING HEALTH AUXILIARIES 291

Figure 6. A protocol for management of respiratory infections in children under 4 years of age.*

, Is he throwing up?--After co tghi~g only? No - I Yes

--After each feeding? I No I Yes

or more or more or more / or more 7

I_..

Yes

1 Do Educational Task A

1st

Treat as below; do educational Task A & follow- p in 5 days- Refer to Clinic if not better Respiratory Infection yreat as beliw; do educational Task A & follow-

up in 24 hours; Refer to Clinic if not better Refer to Clinic right away

(Use Acetaminophen

Name:

kdaNF : - . Age: - Sex : - Signed: CHR(900)

Residence.

Location ;if-Eilcount.er: Reviewed:

Date: CHR Supervisor

292 PAHO BULLETIN l vol. XII, no. 4, 1978

Training and Continuing Education

The initial training provided for auxil- iaries in such a program should follow directly from the tasks and task structures that define the educational objectives sought. That is, the curriculum should be designed to make the auxiliaries competent in specific tasks and their application. For a given health problem, the training usual- ly takes two or three days. The problem is first introduced by discussing its pertinent features-such as epidemiology, pathophy- siology , and the objectives of treatment. Then the problem-solving process is intro- duced and is applied-by way of illustra- tion- to a nonhealth problem.

After that the individual tasks are introduced; and once competence in the individual tasks has been achieved, the task structure is’ introduced by way of the protocol. A great deal of time is then devoted to instruction in use of the proto- col -instruction including role-playing ses- sions that allow the auxiliary to go through the problem-solving process with a “mock” patient. Finally, the auxiliary works with a health professional in a clinical setting, applying the protocol to real patients and being “checked out” by the professional. During this latter phase it is extremely im- portant to reinforce the auxiliary’s strengths-as well as to correct his defi- ciencies.

As the training progresses, the auxiliary keeps the protocol and each of the tasks that he has learned in a notebook for future reference. These items thus become his “task inventory,” to which new tasks and protocols can be added in conformity with his progress and the health needs of his community .

Results to Date

The methodology described has been pilot-tested at selected Indian Health Serv- ice sites over the last four years and has led

to an improvement in both the process and the outcome of health care provided in the rural communities involved. The results of these pilot studies can be briefly summa- rized as follows:

In most cases the health auxiliaries using the methodology have been tribal health workers selected by their communities to receive a basic training program in general health concepts lasting about two weeks. In some instances school personnel have been provided with brief on-the-job training to enable them to use the methodology. Many of the workers using the protocols have had a high school education, but none has had a specific health sciences background.

The results obtained show that the health workers’ compliance with care standards has been consistently high (23, 14). In fact, community health representa- tives using a gastroenteritis protocol achieved a compliance level exceeding that of professionals*(13).

Furthermore, the effectiveness of the whole care system has been enhanced through a case-finding and early interven- tion effect that has resulted in patients with serious illness making contact with a health professional earlier in the course of that illness. Using protocols for respiratory infection, community health representa- tives were often able to detect and refer patients with pneumonia to a physician before the onset of respiratory distress. In a population served by these health workers, only 43 per cent of all pneumonia cases showed clinical respiratory distress when first presented to a physician, as compared to 95 per cent in a similar population with no health workers (13, 14).

Nutting et al. l METHODOLOGY FOR USING HEALTH AUXILIARIES 293

services became more accessible (14). Simi- larly, protocols for minor acute illness in school-age children enabled school health workers to achieve a 22 per cent reduction in visits to physicians (15). Furthermore, the health outcomes of cases managed by health workers were indistinguishable from those of cases treated by physicians.

The health workers were also found to have made a real impact on the health status of the populations served. Among other things, significant primary preven- tion of infant gastroenteritis was achieved, particularly when services were differen- tially allocated in favor of a high-risk group (Id). (Significant secondary preven- tion of infant gastroenteritis was also at- tained through provision of direct services and expedient referrals to health profes- sionals-13.)

A similarly positive result was achieved by school health workers using protocols designed to permit early detection of emotionally troubled children and inter- vention on their behalf (27).

Concluding Remarks

Implementation of this methodology can result in additional portals of entry into the health care system and appears to improve the accessibility of health care. Continuity of care is maintained-by ensuring that the system gives a consistent response governed by standards of problem- staging and clinical problem-solving that are mutually agreed upon by providers within the system. Most important, the health benefits gained by the individual patients served are improved.

It is also true, however, that adaptation of the methodology for use in a given location requires consideration of at least four factors.

The first of these is the matter of refer- ral. Regardless of how many tasks the auxiliaries can perform and the sophistica- tion of the protocols, there will be a signifi-

cant number of patients whose conditions require diagnostic skills or treatment skills beyond the auxiliaries’ capabilities. There- fore, a hierarchy of medical skills is needed within the system, together with access to such skills through referral. Clearly the methodology, by itself, does not solve problems imposed by poor communications networks or lack of referral facilities. However, since the protocols can be designed to indicate specifically how, when, and to whom referrals should be made, the methodology does permit the health care system to set precise limits for the auxiliary and to plan for referrals in accord with its own constraints.

The second factor to consider is that of supervision and monitoring. Pragmatical- ly, it is doubtful that most health care sys- tems will enjoy a completely satisfactory supervisory structure in the near future. However, the protocol approach does pro- vide a basis for objective and task-oriented supervision. This can be performed either concurrently, through observation of an auxiliary’s performance, or retrospectively, through a review of completed protocols. The actual monitoring of completed proto- cols for compliance with preset standards can be done by nonprofessionals, who can then provide tabulated results to a profes- sional responsible for interpretation of these results and necessary corrective ac- tion. The use of clerical personnel in checking and tabulating such results can save some professional supervisory time.

294 PAHO BULLETIN l vol. XII, no. 4, I978

communications and transport problems, shortages of supervisory personnel, specific locations of referral facilities, and distribu- tion of the more highly skilled personnel within the overall system. It is relatively easy to provide a health auxiliary with basic training and equipment and to place him in a rural community, but this does not mean he will function effectively as a member of a health care team. Where existing constraints are severe, the role played by defined care standards and task structures becomes critical.

Finally, it is necessary to consider cost. It appears that the methodology described can be implemented at reasonably low cost, at least when a cadre of auxiliary workers is

already in place. Major cost components include the time spent by professionals in planning the program and designing and testing protocols appropriate for program objectives, prevalent health problems, and anticipated auxiliary skill levels. The cost of brief on-site training for both auxiliaries and supervisors must also be included. Equipment costs will vary with the type of health problem, but will be relatively minor in most cases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors wish to express their appre- ciation to Ms. Lisa Preston for her invalua- ble assistance in preparing the manuscript.

SUMMARY There is growing interest in using health auxiliaries to provide primary care in develop- ing areas. This article presents a methodology designed to define the auxiliary’s role in this context, his specific tasks, and his place within the health system.

This methodology begins by selecting particu- lar health problems to be covered. Forms are then drafted which enable the auxiliary to clas- sify patients according to the severity or “stage” of the problem. On the basis of this classifica- tion clinical problem-solving standards are established for each problem stage, and specific tasks are assigned. In addition, a clinical protocol is developed which defines the “task

structure”-including the sequence in which tasks are to be performed and the relationship between the auxiliary’s tasks and those carried out elsewhere in the health system. Auxiliary training then focuses on these tasks and protocols. Provisions are also made for auxiliary supervision and program evaluation.

This methodology has been tested within the Indian Health Service (U.S. Public Health Service) for four years. Results to date indicate a high degree of compliance with care standards, success in shifting some of the workload from the physician to the auxiliary, and improvement in public access to primary care.

REFERENCES (I) Djukanovic, V., and E. Mach. Alternative

Apfiroaches to Meeting Basic Health Needs in DeveloPing Countries: A Joint UNICEF/WHO Study. World Health Organization, Geneva, 1975.

(2) Newell, K. (ed.), Health by the Peosle. World Health Organization, Geneva, 1975.

(3) Uhrich, R. B. Tribal community health representatives of the Indian Health Service, Public Health Re$ 84:965-970, 1969.

(4) Eneboe, P. The village medical aides: Alaska’s unsung, unlicensed and unprotected physicians. Alasha Med 124-127, 1971.

(5) Harrison, T. J. Training for village health aides in the Kotzebue area of Alaska. Public Health Rep 80:565-572, 1965.

(6) Shook, D. C. Alaska native community health aide training. Alaska Med 62-63, 1969.

Nutting et al. . METHODOLOGY FOR USING HEALTH AUXILIARIES 29.5 CL--

Report, No. 1-C.” Albuquerque, New Mexico, 1974.

(8) Shorr, G. I., and P. A. Nutting. A population-based assessment of the continuity of ambulatory care. Med Cure 15:455-464, 1977.

(9) Komaroff, A. C., W. L. Black, M. Flately, R. H. Knopp, B. Reitten, and H. Sherman. Protocols for physician assistants: Management of diabetes and hypertension. N Engl J Med 290:307-312, 1974.

(10) Sox, H. C., C. H. Sox, and R. K. Tomkins. The training of physicians’ assistants: The use of a clinical algorithm system for patient care, audit of performance and educa- tion. N Engl J Med 288~818, 1973.

(II) Hirschhorn, N., J. H. Lamstein, R. W. O’Connor, and A. Kestorton. Logical flow charts to train and guide health auxiliaries in the treatment of children’s diarrhea. Trol, Doct 6:33-36, 1976.

(12) Hirschhorn, N., J. H. Lamstein, R. W. O’Connor, and K. M. Denny. Logical flow diagrams in the training of health workers. Environ ChiEd Health 21:86-87, 1975.

(13) Nutting, P. A., G. I. Shorr, and L. E.

Berg. Process and outcome measures of tribal health workers in direct patient care, advanced med. systems: Issues and challenges. In: Flagle Co. (Ed.), Symposia Specialist, Miami, 1975.

(14) Nutting, P. A., S. Manuel, P. Lopez, and M. Pancho. Management of Respiratory Infections by Community Health Representa- tives. Office of Research and Development, Indian Health Service, U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Tucson, Arizona, 1976.

(15) Nutting, P. A., J. C. Reed, and G. I. Shorr. Nonhealth professionals and the school age child: Treatment of minor acute health problems. Am J Dis Child 129:816-819, 1975.

(26) Nutting, P. A., C. R. Strotz, G. I. Shorr, and L. E. Berg. Reduction in gastroenteritis morbidity in high-risk infants. Pediatrics 55: 354-358, 1975.

(17) Nutting, P. A., T. B. Price, and M. L. Baty. Non-health professionals and the school age child: Early intervention for behavioral problems. Office of Research and Development, Indian Health Service, Dept. of Health, Educa- tion and Welfare, Tucson, Arizona, 1978.

CORRIGENDUM

Bulletin of the Pan American Health Organization Vol. XII, No. 2, 1978