Nova School of Business and Economics

Universidade Nova de Lisboa

Thesis submitted as part of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Management

The Role of Individual Ability and Structural Embeddedness on

Entrepreneurial Success

Bernardo M. Pimentel

A Thesis carried out under the supervision of Professor José Mata

February 4, 2015.

Table of Contents

I. Abstract ... 4

II. Introduction ... 5

III. Survey of the Literature ... 8

A. Entrepreneurial Ability ... 8

B. Structural Embeddedness... 20

IV. Hypotheses ... 26

A. Firm Performance ... 26

B. Continue, Transfer, or Close ... 32

C. Entrepreneurial Specialisation ... 37

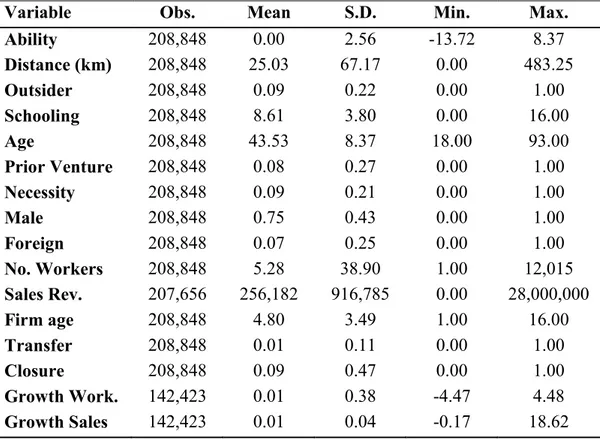

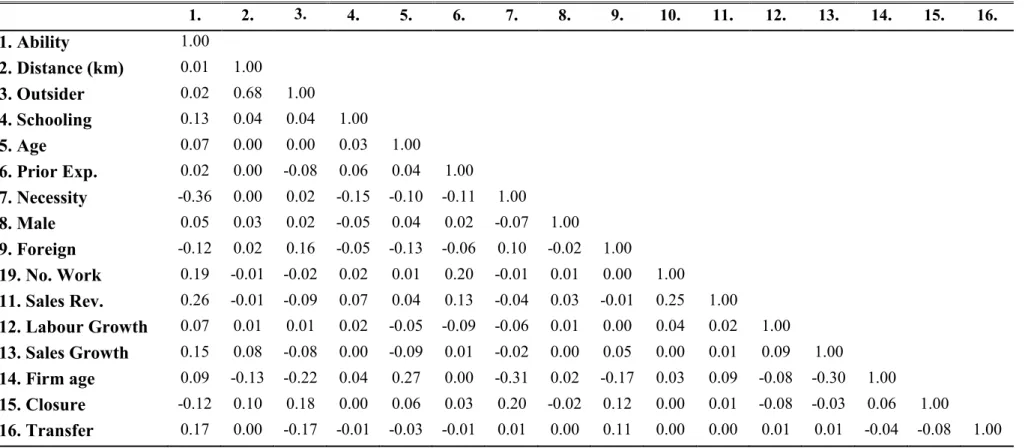

V. Data and Methods ... 40

A. Data ... 40

B. Methods ... 53

VI. Results ... 62

A. Prior Productivity as Worker ... 62

B. Performance of Entrepreneurial Ventures... 64

C. Decision to Continue, Transfer, or Close ... 72

D. Entrepreneurial Specialisation ... 76

VII. Conclusions ... 82

A. Discussion ... 82

B. Limitations and Paths for Future Research ... 84

C. Final Remarks ... 86

D. Acknowledgements ... 87

I. Abstract

In the present thesis I analyse the roles of individual ability and structural

em-beddedness on entrepreneurial success. The results retrieved from a matched

employer-employee longitudinal data set show prior worker productivities and

environmental embeddedness to have a persistent positive impact on the size

and growth rates of new firms. What is more, embeddedness facilitates the

im-pact of ability on start-up performance with outsiders of comparable abilities

starting smaller and slower growing firms. Those in higher ability categories

are more likely to transfer and also, albeit to a lesser extent, close their

ven-tures, an effect attributed to the higher opportunity costs associated with the

group. Firms managed by embedded agents enjoy longer longevities and have

better chances of finding a new owner after the departure of the previous one.

Finally, higher ability types show evidence of specialisation in serial

entrepre-neurship.

(Keywords: entrepreneurship; individual ability; structural embeddedness; division of

labour)

“For he is Odysseus, a man of great craft, son of Laertes born in rugged Ithaca, and

ex-cels in all manner of tactics and subtle mētis”

Homer, Book III of the Iliad

II. Introduction

Mētis is an Ancient Greek word that denotes a quality of skill or cunning. It was the

de-fining trait of Odysseus, a character introduced by Homer in the Iliad and the hero of the

later Odyssey. Odysseus is a man of cunning who will take all necessary measures to

guarantee the success of his endeavours. By deceiving the Trojan with the gift of a giant

wooden horse, Odysseus was able to sneak into the citadel and overcome a larger force

than his own. Odysseus used whatever scarce resources he had at his disposal to great

effect, often by spotting an opportunity where others saw but a deadlock. Whilst the

con-temporary reader may be estranged by such a take on heroism, the conception of mētis

was in fact deeply rooted in Classic Greek tradition. Alexander the Great, for example, is

credited with solving the Gordian knot riddle by simply cutting it with his sword. Greek

heroes were not necessarily the bravest or the wisest. What they achieved however, was

unique and that was what distinguished them from their peers.

The previous analogy offers a brief description of one of the traits most

common-ly associated with the figure of the entrepreneur. The notion that entrepreneurs play

unique role in an economy can be traced back to Cantillon (1755) and has over time

re-ceived attention from scholars in various fields. Whilst contributions inspired mainly by a

disequilibrium approach to entrepreneurship emphasised the importance of the ability to

discover and create business opportunities (Schumpeter, 1934; Schultz, 1975; Casson,

differences in ability affected occupational choices leading to entrepreneurship and the

resulting individual and firm outcomes (Lucas, 1978; Casson, 1982; Amit et al., 1995;

Hamilton, 2000)

1. Holmes and Schmitz (1990) showed that individuals with greater

lev-els of ability to identify opportunities had a comparative advantage in specialising in

seri-al entrepreneurship whilst Gimeno et seri-al. (1997) explained the subsistence of

underper-forming firms with the relatively lack of employment alternatives for their owners.

However, the effect of ability on firm outcomes can also be conditioned by the

ex-isting degree of embeddedness between the entrepreneur and the business environment.

Firm internationalisation literature has long identified a liability of foreignness effect

(Zaheer, 1995) that hampers the performance of otherwise competitive newcomers into a

market. More recent contributions (Johanson and Vahlne, 2009) have generalised this

finding to all outsiders to a given environment and Figueiredo et al. (2002) found a strong

preference for entrepreneurs to start a new firm in areas where they had previously

worked.

In this thesis I assess how ability and embeddedness affect the outcomes of new

ventures and of their founders. Using a longitudinal data set with detailed information of

both individual and firm characteristics, I explore how past productivities of individuals

as wage-earners impact upon entrepreneurial outcomes and decisions. The distances

be-tween geographic locations of the workplaces of those individuals before and after the

beginning of their first self-employment spell serve as a proxy for embeddedness and also

constitute a determinant of firm performance, longevity, and transfer.

Results confirm the presence of a lasting interconnection between past

productivi-ties and the performance of subsequently created firms, with ventures created by superior

1 Whilst acknowledging the literature based on the risk preferences of the entrepreneur developed from the early