www.revportcardiol.org

Revista

Portuguesa

de

Cardiologia

Portuguese

Journal

of

Cardiology

CASE

REPORT

HIV

and

coronary

disease

---

When

secondary

prevention

is

insufficient

夽

Ana

Sofia

Carvalho

a,∗,1,

Rui

Osório

Valente

b,1,

Luís

Almeida

Morais

c,

Pedro

Modas

Daniel

c,

Ramiro

Sá

Carvalho

c,

Lurdes

Ferreira

c,

Rui

Cruz

Ferreira

caServic¸odeMedicinaInterna,HospitalEgasMonizCentroHospitalardeLisboaOcidental,Lisboa,Portugal bServic¸odeMedicinaInterna,HospitalBeatrizÂngelo,Loures,Portugal

cServic¸odeCardiologia,HospitaldeSantaMarta,CentroHospitalarLisboaCentral,Lisboa,Portugal

Received6April2016;accepted3October2016 Availableonline5July2017

KEYWORDS Human immunodeficiency virus; Stentthrombosis; Coronarydisease

Abstract Highlyactiveantiretroviraltherapy(HAART)hascreatedanewparadigmforhuman immunodeficiencyvirus(HIV)-infectedpatients,buttheirincreasedriskforcoronarydiseaseis welldocumented.

Wepresentthecaseofa57-year-oldman,co-infectedwithHIV-2andhepatitisBvirus, ade-quatelycontrolledandwithinsulin-treatedtype2diabetesanddyslipidemia,whowasadmitted withnon-STelevationacutemyocardialinfarction.Coronaryangiographyperformedondayfour ofhospitalstaydocumentedtwo-vesseldisease(midsegmentoftherightcoronaryartery[RCA, 90%stenosis]andthefirstmarginal).Twodrug-elutingstentsweresuccessfullyimplanted.The patientwasdischargedunderdualantiplatelettherapy(aspirin100mg/dayandclopidogrel75 mg/day)andstandardcoronaryarterydiseasemedication.Hewasadmittedtotheemergency roomfourhoursafterdischargewithchestpainradiatingtotheleftarmandinferiorST-segment elevationmyocardialinfarctionwasdiagnosed.Coronaryangiographywasperformedwithinone houranddocumentedthrombosisofbothstents.Opticalcoherencetomographyrevealedgood appositionofthestentintheRCA,withintrastentthrombus.Angioplastywasperformed,with agoodoutcome.

TheacutestentthrombosismightbeexplainedbythethromboticpotentialofHIVinfection anddiabetes.TherearenospecificguidelinesregardingHAARTinsecondarypreventionofacute coronarysyndromes.Amultidisciplinaryapproachisessentialforoptimalmanagementofthese patients.

© 2017SociedadePortuguesade Cardiologia.Publishedby ElsevierEspa˜na,S.L.U.Allrights reserved.

夽 Pleasecitethisarticleas:CarvalhoAS,OsórioValenteR,AlmeidaMoraisL,ModasDanielP,SáCarvalhoR,FerreiraL,etal.VIHedoenc¸a

coronária---quandoaprevenc¸ãosecundáriaéinsuficiente.RevPortCardiol.2017;36:569.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:asofia.dc@gmail.com(A.S.Carvalho).

1 Theseauthorscontributedequallytothiswork.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE Vírusda

imunodeficiência humana;

Trombosedestent; Doenc¸acoronária

VIHedoenc¸acoronária---quandoaprevenc¸ãosecundáriaéinsuficiente

Resumo A terapêutica antiretroviral (TARV)alterou o paradigmada infec¸ãopelo vírusda imunodeficiênciahumana(VIH),conhecendo-seoriscoaumentadodedoenc¸acoronárianestes doentes.

Apresenta-seocasodeumhomemde57anos,melanodérmico,comcoinfecc¸ãoVIH-2/vírus hepatiteB,comcontroloadequado;diabetesmellitustipo2,insulino-tratadoedislipidemia. Internado por enfarte agudo do miocárdio, semsupradesnivelamento ST. Realizou cateter-ismo ao 4.◦ dia deinternamento,documentando-se doenc¸a dedois vasos(segmento médio dacoronáriadireita[CD][90%estenose]e1.a

obtusamarginal[OM1]comestenosede95%). Colocaram-sedoisstentsrevestidos,semintercorrências.Tevealtasobduplaantiagregac¸ão (ácido acetilsalicílico 100 mg/dia e clopidogrel 75 mg/dia) e restante terapêutica dirigida à doenc¸a coronária. Recorreu ao servic¸o de urgência quatro horas após a alta por pré-cordialgiacomirradiac¸ãoaomembrosuperioresquerdo,tendo-sediagnosticadoenfarteagudo domiocárdio com supradesnivelamentodo segmentoST nasderivac¸ões inferiores.Realizou coronariografiaumahoraapósoiníciodador,querevelouoclusãodeambososstents.A tomo-grafiadecoerênciaótica (OCT)revelouboaaposic¸ãodostentnaCD,trombos intra-stente dissecc¸ãocominícionamargemdistaldostent.Realizou-seangioplastiadeambasasartérias, comsucesso.

Atromboseagudadosstentspodeserexplicadapeloaumentodopotencialtrombótico con-feridopeloVIHepeladiabetes.Nãoexistemrecomendac¸õesespecíficasrelativasàTARVna prevenc¸ãosecundáriaapósSCA.Aabordagemmultidisciplinardestesdoenteséessencialpara asuaorientac¸ãoadequada.

©2017SociedadePortuguesadeCardiologia.PublicadoporElsevierEspa˜na,S.L.U.Todosos direitosreservados.

Introduction

Theadventofhighlyactiveantiretroviraltherapy (HAART) has led to a marked decrease in morbidity and mortal-ity among patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection,1---4 and a consequent increase in their

life expectancy and in the prevalence of chronic dis-eases not previously associated with HIV. These include cardiovascular and liver disease and cancer,5---7 the

treat-mentofwhichisbecomingincreasinglyimportantinthese patients.

Thereisinfactawell-documentedhigherriskofcoronary arterydisease(CAD)inHIVpatientscomparedtothegeneral population.3,8,9 In a study carried out by the

Antiretrovi-ral Therapy Cohort Collaboration,6 which included 39272

patients from 13 cohorts of patients receiving HAART between 1996 and 2006 in Europe and the USA, mortal-ity attributed to cardiovascular disease in HIV patients was 7.9% (40% of which was due to CAD or myocardial infarction[MI]and18%tostroke).TheD:A:Dstudy,7which

wascompletedlaterandincluded49731patientsfollowed between1999 and 2011 inclinics in Europe,the USAand Australia,reportedmortalityof11%due tocardiovascular disease.

Therearefewdataontherisk ofadverse cardiovascu-lareventsinHIV-infectedpatientsundergoingpercutaneous coronaryintervention(PCI) withdrug-elutingstentsinthe contextofacutecoronarysyndrome(ACS).Somestudies10---12

have reportedsimilarrates for infected andnon-infected patients.

WereportthecaseofanHIVpatientwithdiabeteswho presentedacutethrombosisofdrug-elutingstentsintwo dif-ferentcoronaryarteriesfourhoursafterhospitaldischarge, whichmanifestedasST-elevationMI.

An unusual case of acute stent thrombosis in an HIV patientispresented,togetherwithaliteraturereviewand discussionofpossibleexplanationsforthisatypical presen-tation.

Case

report

A 57-year-oldman, black,born in Guinea and resident in Portugal since1982, an astrologer, hada personal history ofco-infectionwithHIV-2andhepatitisBvirus(HBV).HIV-2 wasdiagnosedin1997(19yearsbeforethishospitalization), when HAART wasbegun. The patient’s CD4+ T cell count beforetherapyisunknown.Hewasregularlymonitoredand complied withtherapy, which included the antiretrovirals lamivudine,stavudine,indinavirandabacavir.

Thepatient’sviralloadandCD4+Tcellcountwere gen-erallyundercontrolfromthetimeofdiagnosis,exceptfor a periodof oneyear approximatelytwoyears beforethis admission,whenhepresentedanincreasedviralload (max-imum4500copies/ml,although hisCD4+Tcellcountwas controlledthroughoutthisperiod).

At admission,the patient wasunder combinedHAART, namely tenofovir and emtricitabine 300 mg/200 mg once daily;darunavir incombination withritonavir600 mg/100 mg twice daily and raltegravir 400 mg twice daily. He

presented adequate CD4+ T cell counts and negative viral load. HBV infection was diagnosed in 2010 (six years beforethis hospitalization),and regular monitoring continued to show negative viral load under tenofovir therapy.

He had a history of insulin-treated type 2 diabetes, diagnosed 17 years prior to this admission, with no knownmicrovascularcomplications,andmixeddyslipidemia (predominantly hypertriglyceridemia),diagnosed 10 years previously.Laboratorytestsatthetimeofdiagnosisshowed totalcholesterol205mg/dl,highdensitylipoprotein(HDL) cholesterol21mg/dl,lowdensitylipoprotein(LDL) choles-terol90mg/dl,andtriglycerides265mg/dl.Therapywith fenofibrate145mg/dailywasbegun,whichthepatienthad continuedeversince.PersistentlyhightotalandLDL choles-terollevelsduringfollow-upledtoatorvastatin20mgbeing addedaroundfouryearspreviously.

The patienthad noother risk factors, including smok-ing,cocaineuse,hypertension,obesityorfamilyhistoryof suddendeath.

Besides HAART, he was thus being medicated as an outpatient with atorvastatin 20 mg, fenofibrate 145 mg, pantoprazole 20 mg, linagliptin 5 mg and insulin (Insulatard®).

Thepatientwenttotheemergencydepartment(ED)due torightchestpainradiatingtotheneckthathadbegunthat morningassoonashearose,notassociatedwitheffortand withnoaggravatingoralleviating factors.Hereportedno respiratoryorgastrointestinalproblems,feverorhistoryof trauma.

Physical examination on admission to the ED revealed no significant alterations. Diagnostic exams included an ECG, which showedsinus rhythmand right bundlebranch block(RBBB),butnoST-segmentchanges.Laboratorytests revealedhemoglobin11.5g/dl,sodium134mmol/l, potas-sium 4.6 mmol/l, chloride 100 mmol/l, urea 56 mg/dl, creatinine1.46mg/dl(estimatedglomerularfiltrationrate 61 ml/min/1.73 m2 according to the Chronic Kidney

Dis-ease EpidemiologyCollaboration equation),and increased myocardial necrosis markers (high-sensitivity troponin I 348.5 g/l at first assessment and 392.2 g/l at second assessment,ariseof13%).

Adiagnosisof non-STelevationMIwasmade,aloading dose of dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopido-grel) wasadministeredand thepatient wasadmitted.He presented no further episodes of chest pain, myocardial necrosismarkers fellfrom409.9 g/l(peak)to78.2 g/l andtherewerenonewECGalterations.

Coronaryangiographyonthefourthdayofhospitalstay showedtwo-vesseldisease(90%stenosisofthemidsegment oftheright coronaryartery[RCA],and95%stenosisofthe firstmarginal), and twodrug-elutingstents were success-fullyimplanted.

The patient remained hemodynamically stable under dualantiplatelettherapy(aspirin100mg/dailyand clopido-grel75mg/daily)andhigh-dosestatintherapy(atorvastatin 40 mg). Bisoprolol and lisinopril were also started dur-ing hospital stay. The patient also received the same antiretroviral therapy he had been receiving as an outpatient.

Laboratory tests during hospitalization showed poor metaboliccontrol,withglycosylatedhemoglobin9.2%(7.0%

threemonths previously) and undetectable HBV and HIV-2 viralloads. The patient’s lipidprofile at admission was total cholesterol 142 mg/dl, HDL cholesterol 18 mg/dl, LDL cholesterol 52 mg/dl (by direct measurement), and triglycerides326mg/dl.Testingforthrombophiliaincluded measurementof protein S, protein C, homocysteine, fac-torV Leiden, antithrombinand von Willebrand factor, all of which were within the reference range; screening for anti-nuclear antibodies and lupus anticoagulant was also negative.

The patient was discharged on the 11th day of hos-pitalization, under the medication described above and maintainingtheantiretroviraltherapyhewasreceivingat admission.Therewerenofurthercomplications.

HereturnedtotheEDfourhoursafterdischarge,dueto chestpainradiatingtohisleftarm.

The ECG showed sinus rhythm, RBBB and ST elevation inleadsDII,DIII,andaVFandSTdepressioninleadsV1-V3 (Figure1).

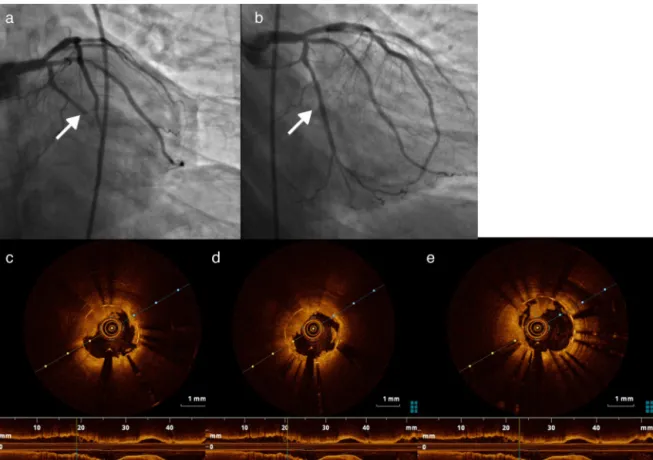

Coronaryangiographywasperformedwithinan hourof painonset,andrevealedocclusionofbothstents(Figure2a and b). Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the two arteries was performed to clarify the situation. OCT of the RCAshowed good stent apposition, intrastent throm-bus and dissection beginning at the distal margin of the stent(Figure3a-c),whileOCTofthefirstmarginalshowed good apposition and intrastent thrombi but no dissec-tion (Figure 4a, c-e). Angioplasty of the mid segment of theRCA was then performed, and a stent wasimplanted afterthrombusaspiration(Figure3d-f),aswellasballoon angioplastyofthefirstmarginal afterthrombusaspiration (Figure 4b). There was a good final result, TIMI 3 flow beingre-establishedinbotharteries.AglycoproteinIIb/IIIa inhibitor(abciximab)wasadministered,duetothepatient’s highthromboticburden.

Aftertheprocedureitwasdecidedtoreplaceclopidogrel byticagrelor.Thepatientexperiencednorecurrenceofpain ornewECGalterationsduringtherestofhospitalstay.He wasdischargedmedicatedwithaspirin 100mgoncedaily, ticagrelor90mgtwicedaily,bisoprolol5mgoncedailyand lisinopril20mgoncedaily.

Atthe timethiscase reportwasprepared,thepatient hadundergone cardiologicalassessmentafterfourmonths offollow-up, and nofurtherischemic complications were recorded.

Discussion

TheincreasedlifeexpectancyofHIV-infectedpatients fol-lowingtheintroductionofHAARThasbeenaccompaniedby anincreasedprevalenceofmetabolicdisorders,whichraises newproblemsfortheirmanagement.

HIVandthepathophysiologyofcardiovascular disease

Variousfactorsareknowntoincreasetheriskof cardiovascu-lardiseaseinHIVpatients.Ononehand,thispopulationhas ahighprevalenceofconventionalriskfactors,13particularly

smoking,13,14lowHDLcholesterol,hypertriglyceridemiaand

I aVR V1 V4

aVL V2 V5

II

aVF V3 V6

III

Figure1 Admissionelectrocardiogramonsecondhospitalization,showingsinusrhythm,rightbundlebranchblock,STelevation inleadsDII,DIIIandaVF,andSTdepressioninleadsV1-V3.

diabetes in HIV patients exposed to HAART is four times higher that in seronegative patients. On the other hand, complexpathophysiologicalmechanismsrelatedtothevirus itselfalso play a part, resulting frompersistent immuno-deficiency, immune dysregulation, immune activation and inflammation,16eveninpatientsunderHAART.

Endothelialdysfunction,akeyelementofatherogenesis, istheendresultofvariousprocessesthatcoexistinthe pres-enceofHIV,includingdirectandindirectendothelialinjury (viaimmunereactionsordrugs),destructionofCD4+Tcells (accompanied by an increase in shedmembrane particles thatinduceendothelialdysfunction)andenhanced expres-sionofadhesionmolecules(viaincreasedcytokineactivity orasadirecteffectofthevirus).17,18

There is thus a persistent inflammatory state in these patients that results in vascular damage and premature atherosclerosis.19 Some studies have shown a significant

increaseinnon-calcifiedplaquesinHIVpatientstreatedwith HAART, which mayalso be associated withcardiovascular events.20

AnincreasedriskofCADhasalsobeendemonstratedin HIVpatientscomparedtothegeneralpopulation,occurring atanearlierage3andwithmoreaggressivecharacteristics

(greater prevalence of ST-elevation MI and multivessel involvement).2

In addition, HAART also causes metabolic changes that further increase risk in these patients, includ-ing metabolic syndrome, characterized by dyslipidemia

Figure2 (a)Stentthrombosisintherightcoronaryartery(RCA)(arrow);(b)intraluminalsubtractionimagesuggestiveofRCA dissection(arrow);(c)RCAafterthrombusaspiration.

Figure3 (a)Rightcoronaryartery(RCA)dissectionvisiblebyopticalcoherencetomography(OCT);(b)and(c)intrastent throm-bosisinRCAvisiblebyOCT;(d-f)intrastentviewoftheRCAbyOCTafterthrombusaspiration.

Figure4 (a)Stentthrombosisinthefirstmarginal;(b)firstmarginalafterthrombusaspirationandstentplacement;(c-e)thrombus inthefirstmarginaldocumentedbyopticalcoherencetomography.

(predominantly hypertriglyceridemia) and insulin resis-tance,frequentlyassociatedwithabnormalfatdistribution and lipodystrophy.21,22 This, while HAART helpsto reduce

endothelial injury by controlling HIV infection, it also activates the endothelium by interfering in glucose and lipidmetabolism.23

AssessingtherelationshipbetweenHAARTand cardiovas-cularriskiscomplicated,sincethecurrentlyrecommended combinedtherapyregimesincludedrugsofvariousclasses, making it difficult to draw reliable conclusions. In addition, many patients are medicated with different regimes over time, due to therapeutic failure or adverse effects.

DatafromtheD:A:Dstudy,24whichanalyzedthe

associ-ationbetween HAARTand risk of MI, showed that of the protease inhibitors, only indinavir and lopinavir-ritonavir were associated with a significantly increased risk of MI.

Inthesamecohort,ofnucleosidereversetranscriptase inhibitors,onlyabacavir anddidanosine weresignificantly associated with risk of MI. There have been many stud-ieson abacavir in particular, but withconflicting results. Some report an association between current or recent exposuretoabacavirandincreasedriskofMI,25 while

oth-ers found no evidence of such an association.26,27 There

is in fact no known biological mechanism to explain the association,althoughexperimentalstudies havesuggested various potential explanations, including endothelial dys-functionandtheabilityofabacavirtoinduceinflammation of the vascular wall by enhancing leukocyte attachment to endothelial cells, and possibly to increase platelet activation.28

Incidenceofacute-phasereinfarctionorrestenosis inHIVpatients

TheprognosisofHIVpatientsintheacutephaseofACShas beenanalyzed inonly asmallnumberofworks.A nation-widestudy in the USA between 1997 and 200629 found a

higherrateofin-hospitalmortalityinHIVpatientsadmitted withACS(withorwithoutSTelevation),althoughtherewere differencesinthetreatmentofferedintheseropositiveand seronegativegroups.

Some authors argue that HIV patients undergoing PCI present higher incidences of reinfarction, restenosis and stent thrombosis as a result of their prothrombotic state,2,30,31 although fewother studieshavedemonstrated

such an association. Hsue et al.32 reported a higher

restenosis rate after PCI in HIV-infected patients than in controls (52% vs. 14%, p=0.006), but other studies10,11

have reported similar rates of cardiovascular adverse events in patients with and without HIV infection under-going PCI with drug-eluting stents in the context of ACS.

Giventhehigherprothromboticriskofthesepatients,33,34

itisimportanttoinvestigatewhetherthereisinfacta rela-tionshipbetweenHIVinfectionandriskofstentthrombosis. Inaddition,therehavebeennostudiesassessingtheimpact of a more aggressive approach to treating conventional

risk factors in HIV patients witha viewto reducing their cardiovascularrisk.Furtherstudiesareneededtoincrease ourknowledgeinareassuchasreducingimmuneactivation, chronicinflammationandresidualviremia,andthepossible relationship between antiretroviral therapy and stent thrombosis.

Particularaspectsofthecasereported

In thecase presented,eventhough thepatienthadother cardiovascularriskfactors,HIVinfectionappearstobethe mainfactorinvolvedinstentthrombosissosoonafter hos-pital discharge in an individual withoptimized secondary preventiontherapy.

OnepossibleexplanationforstentthrombosisintheRCA wouldbedissectionofthearterythathadnotbeen visual-izedoninitialcoronaryangiographyandthatcontributedto thethromboticevent,sinceOCTrevealedgoodapposition, intrastentthrombusanddissectionbeginning atthe distal margin of the stent. Nevertheless, this is highly unlikely, sinceitdoesnotexplainthrombosisoftwostentsindifferent arteries.

Thefactor thatcouldexplainacutethrombosisofboth stents istherefore increasedthromboticrisk conferredby HIVinfectionandbydiabetes.

There are no specific guidelines with regard to antiplatelettherapy inHIV-infectedpatientsandthe deci-sion to replace clopidogrel by ticagrelorin this case was basednotonevidencebutonthefailureofprevious ther-apy.ItwouldbeinterestingtoknowwhetherthenewP2Y12 inhibitorsaremoreeffectiveatsecondarypreventionof car-diovasculareventsinHIVpatients,andshouldthereforebe usedasfirst-linetherapy.

Conclusions

The transformation of HIV infection from a disease with high short-termmortality to a chronic disease has raised new and pressing research questions regarding the car-diovascular risk ofthis population, giventheir known risk profile.

Thecurrentapproachtoreducingcardiovascularrisk con-sistsof early initiationof HAART andadequate control of conventionalriskfactors.

However,thecasepresentedhighlightsthefactthat ade-quatecontrolofHIVinfectionandconventionalriskfactors maybeinsufficient,andraisesvariousquestionsthatrequire thoroughinvestigation.

Finally,amultidisciplinary approachwillhelp in choos-ing the most appropriate care for these patients, with emphasisontheroleofthecardiologist, infectologistand internist.

Ethical

disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects.The authors declarethatnoexperimentswereperformedonhumansor animalsforthisstudy.

Confidentialityofdata.Theauthorsdeclarethatnopatient dataappearinthisarticle.

Right to privacy and informed consent.The authors declarethatnopatientdataappearinthisarticle.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorshavenoconflictsofinteresttodeclare.

References

1.Neto MG, Zwirtes R, Brites C. A literature review on car-diovascular risk in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients:implicationsforclinicalmanagement.BrazJInfect Dis.2013;17:691---700.Availableat:http://linkinghub.elsevier. com/retrieve/pii/S1413867013001542

2.Cerrato E, Calcagno A, D’Ascenzo F, et al. Cardiovascular diseaseinHIVpatients:frombenchtobedsideandbackwards. Open Heart. 2015;2:e000174. Available at: http://www. pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=4368980 &tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=Abstract

3.EscárcegaRO,FrancoJJ,ManiBC, etal. Cardiovascular dis-easein patientswithchronic humanimmunodeficiencyvirus infection.IntJ Cardiol. 2014;175:1---7,http://dx.doi.org/10. 1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.155.

4.DataCollection OnAdverseEventsOf Anti-HIVdrugs(D:A:D) Study Group, Smith C, Sabin C, Lundgren J, et al. Fac-tors associated with specific causes of death amongst HIV-positive individuals in the D:A:D Study. AIDS. 2010;24: 1537---48.

5.PalellaFJJr,BakerRK,MoormanAC,etal.Mortalityinthehighly activeantiretroviraltherapyera:changingcausesofdeathand disease in the HIV outpatientstudy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr.2006;43:27---34.

6.AntiretroviralTherapy CohortCollaboration.Causes ofdeath inHIV-1-infectedpatientstreatedwithantiretroviraltherapy, 1996-2006:collaborativeanalysisof13HIVcohortstudies.Clin InfectDis.2010;50:1387---96.

7.Smith CJ, Ryom L, Weber R, et al. Trends in underly-ing causes of death in people with HIV from 1999 to 2011(D:A:D):amulticohortcollaboration.Lancet. 2014;384: 241---8.

8.TrianVA,LeeH,HadiganC,etal.Increasedacutemyocardial infarctionratesandcardiovascularriskfactorsamongpatients withhumanimmunodeficiencyvirusdisease.JClinEndocrinol Metab.2007;92:2506---12.

9.FreibergMS,Chang CCH,KullerLH, et al.HIV infectionand the risk of acute myocardial infarction. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:614---22.

10.BoccaraF,TeigerE,CohenA,etal.Percutaneouscoronary inter-ventioninHIVinfectedpatients:immediate resultsand long termprognosis.Heart.2006;92:543---4.

11.Lorgis L, Cottenet J, Molins G, et al. Outcomesafter acute myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients: analysis of datafrom a Frenchnationwide hospital medical information database.Circulation.2013;127:1767---74.

12.BadrS,MinhaS,KitabataH,etal.Safetyandlong-term out-comes after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with human immunodeficiency virus. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv.2015;85:192---8.

13.GlassTR, Ungsedhapand C, Wolbers M,et al. Prevalence of riskfactorsforcardiovasculardiseaseinHIV-infectedpatients

over time: the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. HIV Med. 2006;7: 404---10.

14.Friis-MøllerN,WeberR,ReissP,etal.Cardiovasculardisease risk factors in HIV patients --- association with antiretro-viral therapy. Results from the DAD study. AIDS. 2003;17: 1179---93.

15.Brown TT, Cole SR, Li X, et al. Antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence and incidence of diabetes mellitus in the multicenter AIDS cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165: 1179---84.

16.KullerLH,TracyR,BellosoW,etal.Inflammatoryand coagu-lationbiomarkersandmortalityinpatientswithHIVinfection. PLoSMed.2008;5:e203.

17.HsuePY,WatersDD.Whatacardiologistneedstoknowabout patientswithhumanimmunodeficiencyvirusinfection. Circula-tion.2005;112:3947---57.

18.Oh J, Hegele RA. HIV-associated dyslipidaemia: patho-genesis and treatment. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7: 787---96.

19.Tedgui A, Mallat Z. Cytokines in atherosclerosis: pathogenic and regulatory pathways. Physiol Rev. 2006;86: 515---81.

20.D’Ascenzo F,Cerrato E, Calcagno A, et al. High prevalence at computed coronary tomography of non-calcified plaques in asymptomatic HIV patients treated with HAART: a meta-analysis.Atherosclerosis.2015;240:197---204.

21.Carr A, Samaras K, Thorisdottir A, et al. Diagnosis, predic-tion,andnaturalcourseofHIV-1protease-inhibitor-associated lipodystrophy,hyperlipidaemia,anddiabetesmellitus:acohort study.Lancet.1999;353:2093---9.

22.CarrA.HIVlipodystrophy:riskfactors,pathogenesis,diagnosis andmanagement.AIDS.2003;17:S141---8.

23.Calza L, Manfredi R, PocaterraD, et al. Risk of premature atherosclerosis and ischemic heart disease associated with HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy. J Infect. 2008;57: 16---32.

24.WormSW,SabinC,WeberR,etal.Riskofmyocardial infarc-tioninpatientswithHIVinfectionexposedtospecificindividual antiretroviraldrugsfrom the3 majordrugclasses: thedata collectiononadverseeventsofanti-HIVdrugs(D:A:D)study.J InfectDis.2010;201:318---30.

25.Choi AI,Vittinghoff E,Deeks SG, et al. Cardiovascular risks associatedwithabacavirandtenofovirexposureinHIV-infected persons.AIDS.2011;25:1289.

26.Ribaudo JH, Constance AB, Zheng Y, et al. No risk of myocardial infarction associated with initial antiretrovi-ral treatment containing abacavir: short and long-term results from ACTG A5001/ALLRT. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52: 929---40.

27.BrothersC,HernandezJ,CutrellA,etal.Riskofmyocardial infarction and abacavir therapy: noincreased risk across 52 GlaxoSmithKline-sponsored clinicaltrials in adultsubjects.J AcquirImmuneDeficSyndr.2009;51:20---8.

28.SabinCA,ReissP,RyomL,etal.Istherecontinuedevidencefor anassociationbetweenabacavirusageandmyocardial infarc-tionriskinindividualswithHIV?Acohortcollaboration.BMC Med.2016;14:1.

29.Pearce D, Ani C, Espinosa-Silva Y, et al. Comparison of in-hospital mortality from acute myocardial infarction in HIV sero-positive versus sero-negative individuals. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110:1078---84.

30.SegevA,CantorWJ,StraussBH.Outcomeofpercutaneous coro-naryinterventioninHIV-infectedpatients.CatheterCardiovasc Interv.2006;68:879---81.

31.SudanoI,SpiekerLE,NollG,etal.CardiovasculardiseaseinHIV infection.AmHeartJ.2006;151:1147---55.

32.HsuePY, GiriK,Erickson S, etal. Clinicalfeatures ofacute coronarysyndromesinpatientswithhumanimmunodeficiency virusinfection.Circulation.2004;109:316---9.

33.JongE,MeijersJC,VanGorpEC,etal.Markersofinflammation andcoagulationindicateaprothromboticstateinHIV-infected

patientswithlong-termuseofantiretroviraltherapywithor withoutabacavir.AIDSResTher.2010;7:1.

34.Shen YMP, Frenkel EP. Thrombosis and a hypercoagulable state in HIV-infected patients. Clin Appl Thromb. 2004;10: 277---80.