Universidade Nova de Lisboa

International experiences to increase the use of skilled attendants in

contexts where traditional birth attendants are the primary provider

of childbirth care: a systematic review

Cláudia Susana de Lima Vieira

DISSERTAÇÃO PARA A OBTENÇÃO DO GRAU DE MESTRE EM SAÚDE E DESENVOLVIMENTO, ESPECIALIDADE EM SAÚDE E POBREZA

Universidade Nova de Lisboa

International experiences to increase the use of skilled attendants

in contexts where traditional birth attendants are the primary

provider of childbirth care: a systematic review

Doutora Cláudia Susana de Lima Vieira

Orientador: Professor Doutor Gilles Dussault

Dissertação apresentada para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Saúde e Desenvolvimento, especialidade em Saúde e Pobreza, realizada sob a orientação científica do Professor Doutor Gilles Dussault.

Apoio financeiro de London School of Economics and Political Science Enterprise and Department for International Development.

“If we knew what it was we were doing, it would not be called research, would it?”

A

CKNOWLEDGMENTSJ’aimerais remercier le Professeur Gilles Dussault pour avoir supervisé cette thèse, pour sa patience infinie et son constant soutien.

I would like to thank Annie Portela for the opportunity to develop this project, and Tina Miller for her collaboration.

I also want to thank all the people that in some way were involved in this systematic review, especially from the World Health Organization headquarters, regional and country offices and all who were contacted for references. Special thanks to Tomas Allen for all the help during the systematic search, to Blerta Maliqi, Jelka Zupan and Matthews Mathai for their support in the initial steps of this project, and to Karen Mulweye for her logistical support.

I also would like to thank the London School of Economics and Political Science Enterprise and the Department for International Development for funding.

Gostaria também de expressar os meus sinceros agradecimentos às Professoras Inês Fronteira e Isabel Craveiro pelos seus comentários ao protocolo deste projecto, o que por sua vez me permitiu melhorá-lo.

E porque quem tem amigos, tem tudo, não podia deixar de agradecer a algumas das pessoas mais importantes para mim, nestes anos de mestrado. Obrigada à Aldina e à Laura por toda a ajuda ao longo deste trabalho. Teresita, a ti agradeço teres estado sempre ao meu lado, nos bons momentos mas também nos maus, pelas longas conversas no skype, pelos e-mails gigantescos, enfim, por toda a tua ajuda e apoio!

À Carla quero agradecer a paciência infinita para estar comigo no skype a qualquer hora, para conversas técnicas (e muitos salvamentos do meu desespero total), e por todos os sorrisos nas não técnicas! Para além da ajuda informática nas últimas semanas desta tese. Não me teria sido possível levar este barco a porto seguro contra todas as marés informáticas, se não fosse por ti. E grazie mille a Alessandro (a.k.a. Italianini!) il tuo aiuto informatico è stato essenziale!

Pedro, e a ti como não, quero agradecer teres estado sempre presente para os meus desabafos compostos por alguns sorrisos e... algumas lágrimas! A tua infinita paciência comigo é simplesmente: priceless!

Carla Rodrigues, a ti agradeço a tua ajuda como amiga e socióloga. A tua paciência para as nossas longas horas de discussões científicas, mas não só!

Domingos a ti agradeço-te a amizade e equipamento informático!

Um grande agradecimento aos meus pais por toda a paciência e apoio incondicional.

Não queria terminar sem agradecer a todas as pessoas que passaram pela minha vida nestes últimos anos, e que de alguma forma contribuíram para a concretização deste projecto e para o meu crescimento pessoal. Este projecto só foi possível com a vossa ajuda e apoio!

T

ABLE OFC

ONTENTSResumo 1

Abstract 3

Introduction 5

1. Background 5

1.1 Ensuring women’s rights 7

1.2 Ensuring skilled care for women 9

2. Conceptual framework 14

3. Research questions 16

4. Objectives 17

Methods 19

1. Protocol 20

2. Search methods for identification of studies 21

2.1 Electronic databases 21

2.2 Other references sources 22

2.3 Search strategy 23

3. Criteria for inclusion of references in this review 24

3.1 Types of studies 25

3.2 Types of participants 25

3.3 Types of interventions 26

3.4 Types of outcomes measures 27

4. Data collection and analysis 28

4.1 References selection and eligibility 28

4.2 Quality appraisal and data extraction of the included references 28

4.3 Method of synthesis of findings 31

Results 35

1. Results of the search 35

2. Study characteristics 37

Discussion 89

Annex 1: United Nations MDGs Regions 93

Annex 2: List of electronic databases 97

Annex 3: Entry terms for different databases indexation 101 Annex 4: Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) assessment tool for

qualitative methods 103

Annex 5: McMaster University Occupational Therapy Evidence-Based Practice Research Group assessment tool for quantitative methods 107

Annex 6: Data extraction table 111

Annex 7: List of references 113

L

IST OF TABLESTable 1: Characteristics of the excluded references 38

Table 2: Characteristics of the references that reported on interventions for

human resources development and/or deployment 44

Table 3: Characteristics of the references that reported on interventions for improvement of access to services by removing geographical and/or financial

barriers 62

Table 4: Characteristics of the reference that reported on interventions for

cultural adaptation of institutional childbirths 83

Table 5: Characteristics of the references that reported on interventions for

L

IST OFF

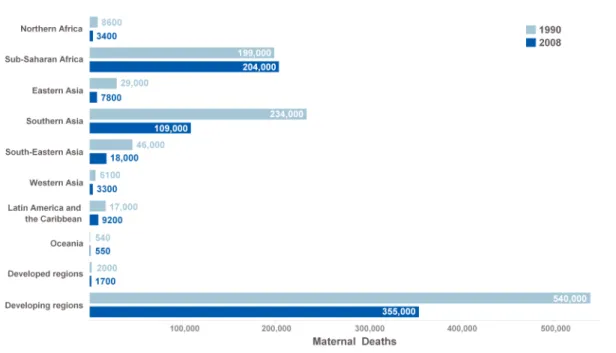

IGURESFigure 1: Comparison of maternal deaths in 1990 and 2008 for the United

Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) regions 6

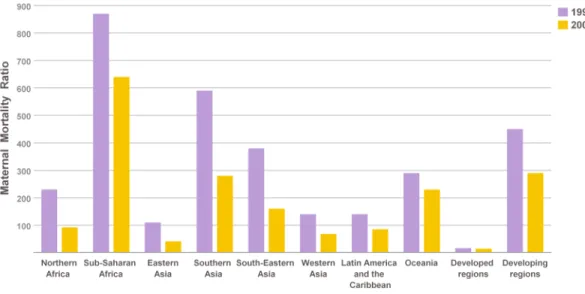

Figure 2: Comparison of MMR in 1990 and 2008 for the United Nations MDGs

regions 7

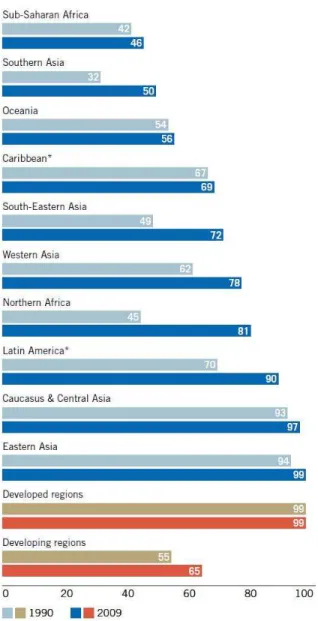

Figure 3: Proportion of deliveries attended by skilled health personnel in 1990

and 2009 (percentage) 13

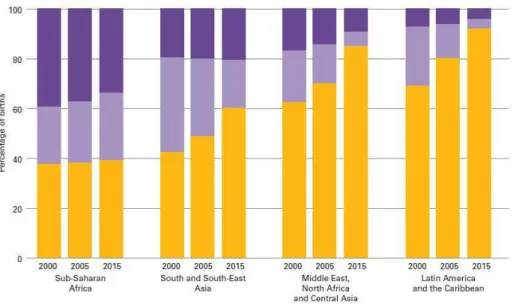

Figure 4: Percentage of births assisted by skilled attendants, TBAs and lay

person in 2000 and 2005 with projections to 2015 14

Figure 5: Conceptual framework for the systematic review 16 Figure 6: Flow chart of the methodological steps in a systematic review 20 Figure 7: Grading of the quality appraisal of the included references 30 Figure 8: Flow chart of the narrative synthesis process 32 Figure 9: Flow diagram of the systematic search process and inclusion of

references for the systematic review 36

Figure 10: Number of references per country 37

L

IST OFA

BBREVIATIONS ANDA

CRONYMSAIM: African Index Medicus AJO: African Journal Online ANC: Antenatal Care

ANM: Auxiliary Nurse Midwife

BEONC: Basic Emergency Obstetric and Neonatal Care BPL: Bellow the Poverty Line

CASP: Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

CB: mothers benefiting from the Chiranjeevi Scheme CEmOC: Comprehensive Emergency Obstetric Care CHWs: Community Health Workers

CI: Confidence Interval

CINAHL: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature CMS: Central Medical Stores

CR: Central Region CS: Centre de Santé

CSBAs: Community Skilled Birth Attendants c-section: caesarean sections

DHO: District Health Offices DHS: Demographic Health Survey DSF: Demand-Side Financing EAs: Enumeration Areas

EmOC: Emergency Obstetric Care

EMRO: Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office FDCP: Free Delivery and Caesarean Policy FGDs: Focus Group Discussions

FHW: Family Health Worker

FWVs: Family Welfare Visitors HAs: Female Health Assistants HEF: Health Equity Fund

Herdin: Health Research and Development Information Network

HIV/AIDS: Human Immunodeficiency Virus/ Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome ICM: International Confederation of Midwives

IFLS: Indonesian Family Life Survey ITM: Institute of Tropical Medicine KIT: Royal Tropical Institute

LILACS: Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences MCH: Maternal and Child Health

MCH-FP: Maternal and Child Health and Family Planning MDGs: Millennium Development Goals

MeSH: Medical Subject Headings MMR: Maternal Mortality Ratio

MoHFW: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare MOI: Major Obstetric Interventions

NCM: mothers not benefiting from the Chiranjeevi Scheme NGOs: Non-governmental Organizations

NTB: Nusa Tenggara Barat Province

OGSB: Obstetrical and Gynecological Society of Bangladesh OR: Odds Ratio

PBC: Performance Based Contracting PHO: Provincial Health Office

PNC: Postnatal Care

POPLINE: Population Information Online PS: Postes de Santé

PSU: Primary Sampling Unit RR: Relative Risk

SBA: Skilled Birth Attendant

STROBE: Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology TBAs: Traditional Birth Attendants

TOT: Training of Trainers

TREND: Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Non-randomized Designs UNFPA: United Nations Population Fund

UNICEF: United Nations Children's Fund VMA: Voucher Management Agencies VR: Volta Region

WHO: World Health Organization

R

ESUMOExperiências internacionais para aumentar o uso de provedores qualificados em contextos onde as parteiras tradicionais são os principais provedores de cuidado no parto: uma revisão sistemática da literatura.

Cláudia Susana de Lima Vieira

Objectivo: A presente revisão sistemática da literatura pretende identificar e compreender melhor, as intervenções implementadas em diversos países, e os respectivos resultados, para aumentar o uso de provedores qualificados, em contextos onde as parteiras tradicionais são os principais provedores de cuidado no parto.

Metodologia: Foram pesquisadas 87 bases de dados electrónicas para a obtenção de referências sobre parteiras tradicionais e obstetrícia. Foram também contactados peritos para a obtenção de mais referências neste tópico. Não foi feita qualquer distinção entre países de baixo, médio ou alto rendimento, ou ano ou estado da publicação. Foram utilizados métodos de revisão sistemática narrativa.

Resultados: A pesquisa electrónica resultou na obtenção de 16.814 referências em 26 das 87 bases de dados pesquisadas. Após a eliminação de duplicados e da aplicação dos critérios de elegibilidade a todas as referências, tanto as obtidas das bases de dados electrónicas, como as dos peritos, 19 referências foram incluídas para extracção sistemática de dados, e 91 foram inventariadas por tipo de intervenção em cada país. As referências obtidas reflectem as experiências de 38 países.

A maioria das intervenções descritas nas 19 referências às quais se fez extracção sistemática de dados foram: melhoria no acesso aos serviços através da eliminação de barreiras geográficas e/ou económicas (n= 10) e desenvolvimento e/ou implantação de recursos humanos (n= 6). Para além destas, 2 referências eram relativas a intervenções de sensibilização da comunidade, e 1 era sobre a adaptação cultural dos partos institucionais.

considerável na qualidade de informação proporcionada. Uma vez que a maioria dos estudos não usou no seu desenho uma distribuição aleatória, foi difícil atribuir com confiança resultados positivos a uma intervenção específica. Contudo, os estudos mostraram resultados positivos para o aumento do uso de atendimento/provedores qualificados e melhorias nos resultados de mortalidade materna, com uma concomitante redução no uso de parteiras tradicionais. No entanto, muitos estudos apontaram uma persistência de desigualdades, e mais atenção precisa de ser dada aos custos de transporte e preferências culturais.

As referências analisadas nesta revisão sistemática da literatura apresentam um segmento de tempo/intervenção e local, e seria útil elaborar uma análise aprofundada dos países, para detectar o impacto destas intervenções na redução de mortes maternas.

A

BSTRACTInternational experiences to increase the use of skilled attendants in contexts where traditional birth attendants are the primary provider of childbirth care: a systematic review.

Cláudia Susana de Lima Vieira

Objective: The current systematic review intends to identify and better understand the interventions implemented in different countries to increase the use of skilled attendants in contexts where traditional birth attendants are the primary provider of childbirth care, and to summarize the outcomes of the different interventions.

Methods: Eighty-seven electronic databases were searched for references on traditional birth attendants and midwifery. Experts in the field were also contacted to request documents related to the topic. No distinction was made between low, middle and high-income countries or publication year or status. Standard narrative systematic review methods were used.

Findings: The electronic searches yielded a total of 16,814 references from 26 of the 87 databases. After elimination of duplicates and the application of the eligibility criteria to all references - from the electronic searches and the experts in the field - 19 references were included for systematic data extraction and 91 references for inventory of the type of intervention and country. These references were from a total of 38 countries.

Of the 19 references from which data was systematically extracted, the majority of interventions described were: improvement of access to services by removing geographical and/or financial barriers (n= 10) and human resources development and/or deployment (n= 6). Following these, 2 references were about a community advocacy intervention and 1 reference was about cultural adaptation of institutional childbirths.

was difficult to confidently attribute positive outcomes to an individual intervention itself. Nonetheless, the studies reviewed showed positive results for increased use of skilled attendance/attendants and improved maternal mortality outcomes, with a concomitant reduction in the use of traditional birth attendants. However many studies noted that inequities persist and more attention needs to be given to transport costs and cultural preferences.

The references analysed in this systematic review present a snapshot of a time/intervention and place and it would be useful to produce in depth country profiles to see the impact of these interventions on maternal deaths reduction.

I

NTRODUCTIONPregnancy and childbirth costs the lives of numerous women every year. Most of these deaths are avoidable, but how best to avoid them is a subject of debate among public health professionals. The present study proposes to perform a systematic review of the available literature to summarize and to categorize the interventions implemented by countries in experiences to increase birth assisted by a skilled attendant, in contexts where traditional birth attendants (TBAs) are the main providers of childbirth care, and to summarize and categorize the outcomes of these interventions.

This work is organized in four main sections. The introduction that sets the state of knowledge on the research topic. The conceptual framework, research questions and objectives are also described in this section. Subsequently, the methods are described and the different criteria for the systematic review explained. The last two sections present the results and the discussion, and also present the limitations of this study and propose future research.

1. Background

Every day 1500 women die from pregnancy or childbirth related complications (1). In 2008, 358,000 maternal deaths worldwide were estimated to have occurred, most of them in low-income countries and preventable (2). These deaths still occur because women have no access to functioning health facilities or to skilled health personnel.

occur because of pre-existing or concurrent diseases, like malaria, anaemia, HIV/AIDS, that are not caused by pregnancy, but can complicate or aggravate it (3).

The most recent estimates from 2008 show that worldwide the number of maternal deaths has decreased from 546,000 in 1990 to 358,000, with the developing regions – mainly Sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia – accounting for most of these deaths (Figure 1) (2). With the exception of two regions – Sub-Saharan Africa and Oceania – all the remaining developing regions showed a decline in the number of maternal deaths (Figure 1) (2).

Figure 1: Comparison of maternal deaths in 1990 and 2008 for the United Nations Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) regions1 (Source: adapted from (2)) .

For the same time period, the maternal mortality ratio2 (MMR) worldwide fell from 400 to 260, with a decline in all regions (Figure 2) (2). The MMR percentage decline was of 34% for developed regions and of 13% for developing regions (2). Among the latter, Eastern Asia had the largest decline (63%), followed by Northern Africa (59%),

1

See Annex 1 for a description of the countries in each of the United Nations MDGs regions.

Eastern Asia (57%), Southern Asia (53%), Western Asia (52%), Latin America and the Caribbean (41%), Sub-Saharan Africa (26%), and Oceania (22%) (2).

Figure 2: Comparison of MMR in 1990 and 2008 for the United Nations MDGs regions (Source: adapted from (2)) .

Although such progress is noteworthy, much more is needed to achieve the target of reducing MMR by three quarters by 2015, as set by the United MDG 5 (4). A reduction in maternal mortality needs to encompass women’s rights and skilled care.

1.1 Ensuring women’s rights

Going back in time, history shows that gender equality was a big issue in the last century. The first time that an international legal document stated “equal rights of men and women” was in the United Nation Charter (5 p15).

The first world conference on the status of women was convened in Mexico City in 1975, with 133 Member States present. It launched a new era in global efforts to promote the advancement of women by opening a worldwide dialogue on gender equality. The Plan of Action set minimum targets to be met by 1980. Those focused on securing equal access for women to resources such as education, employment opportunities, political participation, health services, housing, nutrition and family planning (6).

In 1980, in Copenhagen, 145 Member States met for the second world conference on women. The conference set three priority areas that needed focused action if the goals of equality, development and peace identified by the Mexico City Conference were to be met. These were equal access to education, employment opportunities and adequate health care services (7).

In 1985 in Nairobi, during the third world conference on women, delegates were confronted with data that revealed improvements in the status of women only for a small minority. The Nairobi Forward-Looking Strategies to the Year 2000 declared all issues to be women’s issues (8). The measures recommended covered a wide range of subjects from employment, health, education and social services, to industry, science, communications and the environment that would have to be incorporated in all institutions of society (8).

The United Nations International Conference on Population and Development held in Cairo in 1994 was determinant in setting a clearer international framework for reproductive rights and health. The conference produced a 20-year Programme of Action that focused on universal access to reproductive health services, including family planning and sexual health; reducing infant, child, and maternal mortality; better education, especially for girls; equality between men and women; and sustainable development (9).

Declaration and Platform for Action, an agenda for women’s empowerment (10). Governments committed themselves to the inclusion of a gender dimension throughout all their institutions, policies, planning and decision-making.

1.2 Ensuring skilled care for women

In the 1970s, promoting training of TBAs in modern methods of delivery was introduced as a strategy to tackle maternal mortality that was re-enforced in the following years.

In February 1987, the global campaign to reduce maternal mortality was launched at the first Safe Motherhood conference sponsored by the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) and the World Bank in Nairobi, Kenya. This conference was the starting point of the Safe Motherhood Initiative. A goal was set to reduce maternal mortality by 50% by the year 2000 (11). Among the key strategies embraced for safer motherhood was improving the skills of TBAs and improving referral-level facilities for complications during childbirth and back-up to community-referral-level care.

The World Declaration on the Survival, Protection and Development of Children and its Plan of Action adopted a set of specific, time-bound goals to ensure the survival, protection and development of children in the 1990s, and to be met by the year 2000. Among the goals was also the reduction of maternal mortality rates by half of 1990 levels (12).

In 1992, WHO, UNFPA and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) issued a joint statement promoting the training of TBAs as a way of increasing access to childbirth care, in view of the deficit of professional midwives and institutional facilities (13). A TBA was defined as "a person who assists the mother during childbirth and initially acquired her skills by delivering babies herself or through apprenticeship to other traditional birth attendants." (13 p4).

the survival of babies. But it was only in 1997 at the Sri Lanka meeting that a consensus emerged that making motherhood safer would imply the need to guarantee that all women and newborns have a skilled attendant and skilled care3 during pregnancy, childbirth and the immediate postpartum/postnatal period, for the benefit of the mother and the baby (15). It was recognized that the continued investments in strategies based solely on training TBAs was diverting funds from the more important strategy of providing skilled care for every birth. Nonetheless TBAs continued to be viewed as an important and valued resource that could and should play an important role in supporting improvements to maternal and newborn health (16, 17). In contexts where access to services was limited, TBA training could still be considered to be an important strategy for the transition.

Several studies of the roles of TBAs for maternal survival could not demonstrate significant impact except in small-scale well-managed projects (18-24). In India, training TBAs in care and resuscitation was shown to improve neonatal outcomes (23, 24). A meta-analysis revealed an association between TBA training and small declines in peri-neonatal mortality and birth asphyxia mortality (21). The main findings of two other reviews suggested that training TBAs had small effects on TBA and maternal referral behaviour (18) and antenatal care (ANC) attendance rates (19), although the overall quality of the studies included in both reviews did not allow for a causal attribution to training. A study in Bangladesh found that postpartum infection was not prevented by training TBAs (25). And a study in Ghana revealed that TBA training resulted in harmful outcomes for pregnant women because of the extra confidence gained from training (26). Nonetheless there is no conclusive evidence that training TBAs as a single intervention can have an impact on maternal mortality (22).

In September 2000 the heads of State and Government endorsed the eight United Nations MDGs one of which was the reduction of maternal mortality by 75% between 1990 and 2015, with the proportion of births attended by skilled personnel as an indicator for this

goal, calling for an increase in the proportion of deliveries assisted by a skilled attendant to 90% by 2015 (4, 27).

In 2004 a joint statement was issued by WHO, the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM) and the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) defining the critical role of the skilled attendant. A skilled attendant was defined as “an accredited health professional – such as a midwife, doctor or nurse – who has been educated and trained to proficiency in the skills needed to manage normal (uncomplicated) pregnancies, childbirth and the immediate postnatal period, and in the identification, management and referral of complications in women and newborns.” (28 p1). The skills and abilities of the skilled attendant were identified in the statement and it was stated that TBAs and other health workers did not have the competencies or mandate for all the tasks the skilled attendant is required to perform. Although research had indicated that training of TBAs had not contributed to the reduction of maternal mortality, TBAs were recognized as an important element in a country's safe motherhood strategy and should be considered as key partners for increasing the number of births at which a skilled attendant is present (17). Thus country programmes were encouraged to work with TBAs to identify new roles for them, including collaboration with skilled attendants.

With only a decade left to achieve the MDGs, the WHO dedicated its World Health Report to the health of mothers and children (3).

More recently the United Nations Secretary General launched the Global Strategy for Women's and Children's Health that called for "stronger health systems, with sufficient skilled health workers at their core" (29 p3). This Strategy also reinforced that partners must ensure that women have access to skilled care during childbirth at appropriate facilities (29).

Most countries have embraced the strategies of skilled care and facility childbirth for maternal and perinatal survival. Country data measures showed a significant increase in the proportion of deliveries attended by skilled health personnel, with an increase from 55% in 1990 to 65% in 2009 in the developing regions (Figure 3). Even though much progress has been made, coverage remains low in Sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia. Moreover coverage in remote and marginalized areas is not changing as dramatically. Those women frequently still do not have other options than relying on themselves, or on a family member or a TBA.

Trends in assistance at childbirth show that in many parts of the world women are switching from the use of lay people and TBAs to skilled attendants (Figure 4). Despite these general trends, progress in professionalization of childbirth is held back by a marked stagnation in rural areas, mainly in Sub-Saharan Africa and South and Southeast Asia.

Figure 4: Percentage of births assisted by skilled attendants, TBAs and lay person in 2000 and 2005 with projections to 2015 (Source: (30 p14)).

As 2015 approaches and countries progress towards meeting MDG 5 and the MDG indicator 5.2 of the proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel, many questions arise as to what are the effective interventions.

The work proposed in this project consists on a systematic literature review that intends to identify and better understand the interventions implemented in different countries to increase the use of skilled attendants in contexts where TBAs are the main providers of care during childbirth, and to summarize the outcomes of the different interventions.

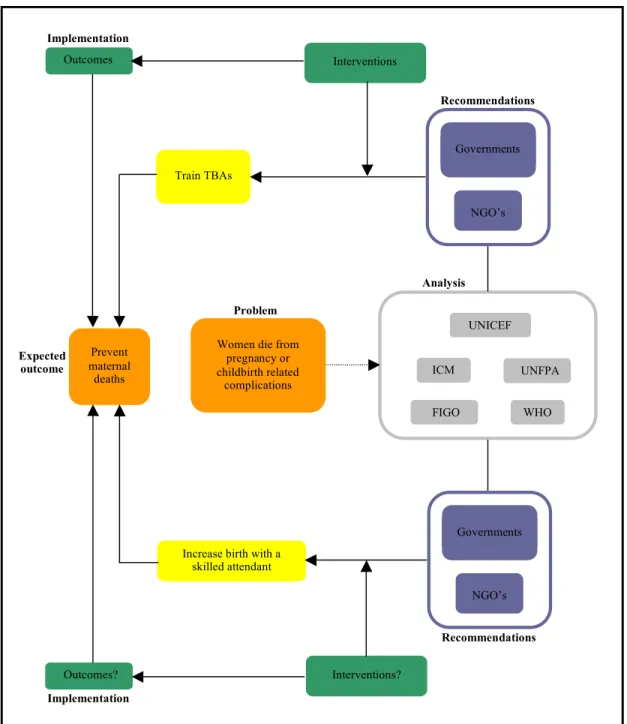

2. Conceptual framework

Interventions? Train TBAs

Outcomes?

Governments

NGO’s WHO FIGO

UNICEF

UNFPA ICM

Increase birth with a skilled attendant

Governments

NGO’s

Women die from pregnancy or childbirth related

complications Prevent

maternal deaths

Problem

Recommendations

Recommendations

Implementation Expected

outcome

Interventions Outcomes

Implementation

Analysis

Figure 5: Conceptual framework for the systematic review.

3. Research questions

adopting various strategies to this end. Arising from the conceptual framework, the systematic review explored two research questions:

a) What interventions have been undertaken by countries to increase the proportion of births assisted by a skilled attendant, in contexts where TBAs are the main providers of childbirth care?

b) What were the effects of these interventions?

4. Objectives

a) To summarize and categorize the interventions implemented by countries in experiences to increase birth assisted by a skilled attendant, in contexts where TBAs are the main providers of childbirth care.

M

ETHODSNowadays the volume of information available is unmanageable and yet health care providers, consumers, researchers and policy makers need to make decisions based on evidence. This is why systematic reviews need to be done to provide research-based evidence in a synthesized form and with appraised quality. To answer our research questions, we chose to conduct such a systematic review.

A definition used by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination states that a systematic review is “a review of the evidence on a clearly formulated question that uses systematic and explicit methods to identify, select and critically appraise relevant primary research, and to extract and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review” (32 p3). Another can be an “attempt to collate all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria in order to answer a specific research question. It uses explicit, systematic methods that are selected with a view to minimizing bias, thus providing more reliable findings from which conclusions can be drawn and decisions made.” (33 p6). Basically, a systematic review is a research with a very precise and rigorous methodology that can be replicated and provides reliable basis for decision making.

In this section we will describe the methodology that was used in this systematic review, taking into account that previously and based on the background information clear answerable research questions were defined.

Formulate review question

Develop review protocol

Initiate search strategy

Download citations to bibliographic software

Apply inclusion and exclusion criteria Eliminate duplicates

Obtain full reports and re-apply inclusion and

exclusion criteria

Data extraction Quality assessment

Data synthesis

Manuscript writing

Figure 6: Flow chart of the methodological steps in a systematic review (adapted from (32)).

1. Protocol

2. Search methods for identification of studies

2.1 Electronic databases

A list of 87 databases (Annex 2) was created to perform the systematic search for this review. This list included databases from two different sources:

a) a list of available health databases developed by the WHO headquarters librarian over the years of work on systematic searches for health systematic reviews;

b) hand-searches of published Cochrane systematic reviews of public health interventions.

Between February 18th and March 10th of 2010, these databases were searched with the following search terms:

- traditional birth attendants (for English indexed databases); - accoucheuses traditionnelles (for French indexed databases).

No specific strategy was developed in Spanish or Portuguese because the databases that retrieve references in these languages are indexed in English.

Taking three points into consideration (operating database; retrieving references for the searched terms used; and scope of the database) the search was restricted to the 26 databases that follow:

African Index Medicus (AIM) African Journal Online (AJO)

African Women's Bibliographic Database Bioline International

Cochrane Library

Conference papers index (CSA ILLUMINA)

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Dissertations and theses (ProQuest)

FRANCIS

Health Research and Development Information Network (Herdin) IndMED

Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM) in Antwerp Belgium La bibliothèque de Santé Tropicale

Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences (LILACS) l'Ecole nationale de la santé publique

Maternity and Infant Care (Ovid) PAIS International

Population Information Online (POPLINE) Pubmed

Royal Tropical Institute (KIT)

Sociofile database (CSA ILLUMINA)

Western Pacific Region Index Medicus (WPRIM) Women's resources international

World Health Organization library database (WHOLIS)

2.2 Other references sources

Contacts were made with relevant agencies and experts in the field to inform of the systematic review and to request pertinent documents or the names of suggested informants.

These contacts started with a request to the Family and Community Health cluster at WHO headquarters, regional and country offices. After their reply with suggestions of informants working in international or national agencies, governments or NGO's, the request was expanded to these, creating a snowball effect. We were able to obtain contacts in other international agencies like UNFPA and UNICEF, as well as in Public Health departments of different Schools and Universities, among others.

With this strategy we were able to obtain grey literature documents and peer-reviewed publications that complemented the database systematic search.

2.3 Search strategy

A search using the terms already described in section 2.1 was performed in the following databases, between February 18th and March 10th of 2010:

Bioline International

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Embase

Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM) in Antwerp Belgium l’Ecole nationale de la santé publique

Population Information Online (POPLINE) Pubmed

These databases were selected on the basis of allowing an analysis of the different entry terms for indexation and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) categories. An analysis of all results obtained (Annex 3) was conducted and a full search strategy was developed for Pubmed and Embase. As the other databases have simpler search engines, the already developed search strategies were further modified as necessary.

The following search strategies were pre-tested to see if some relevant studies identified on a preliminary search using the terms already described in section 2.1 could be obtained.

Search strategy for Pubmed:

"home deliveries"[All Fields] OR "Home Childbirth"[Mesh] OR "home childbirth*"[All Fields]

Search strategy for Embase:

"traditional birth attendant" OR "traditional birth attendants" OR "home delivery" OR "home deliveries"

Some of the selected databases needed to be searched in French and the following terms were settled for that:

- accoucheuses traditionnelles; - accoucheuse traditionnelle; - accouchement à domicile.

No extra terms in Spanish and Portuguese were needed because the selected databases that retrieve documents in these languages allow the search to be performed in English.

The retrieved references were in English, French, Spanish and Portuguese, because these are the languages known by this review authors. In the case of other languages, the title and abstract was analysed to determine if it should be included and a translation done.

All retrieved references were downloaded to Reference Manager 10 for Windows and when not possible, copied to a Word document. Duplicates were eliminated manually in both documents. In the case of a study published in different formats, for example, as an abstract and as a thesis, both references were kept. In the case of partial publications of the same study, all references were kept. In the case of various translations of the same study, only the English version was kept.

3. Criteria for inclusion of references in this review

3.1 Types of studies

Due to the great diversity in conditions and settings of public health interventions, some authors (34) consider that some review questions cannot specify the type of study design to be included. This is the case for this review, in which the type of study design was not a criterion for exclusion. It was anticipated that different types of study designs would be encountered in the search, and if they fulfilled the inclusion criteria set for this review, they would be included regardless their design and publication status.

This systematic review has two components according to the type of data of the references retrieved:

- references with primary or secondary data analysis were included for systematic data extraction;

- references related to the systematic review objectives and that fulfilled the inclusion criteria, but with no data or with data that covered several years with multiple interventions where it was not possible to assign the outcomes to a specific intervention, or deemed very low quality, were kept for inventory purposes, and classified according to country and intervention.

3.2 Types of participants

This review considers the following two WHO definitions for its participants:

- A TBA is "a person who assists the mother during childbirth and initially acquired her skills by delivering babies herself or through apprenticeship to other traditional birth attendants." (13 p4);

- A skilled attendant is “an accredited health professional – such as a midwife, doctor or nurse – who has been educated and trained to proficiency in the skills needed to manage normal (uncomplicated) pregnancies, childbirth and the immediate postnatal period, and in the identification, management and referral of complications in women and newborns.” (28 p1).

Other participants were the individuals, families and communities involved in each intervention.

3.3 Types of interventions

The pillar of the inclusion criteria for this review was that references were only included if they were done in contexts where TBAs were the main providers of care at birth, and any intervention or combination of interventions to increase birth with a skilled attendant was being implemented. Some examples of types of interventions are listed here, but others were included if planned or implemented by countries. The only purpose of this list is to drive the reader’s attention to the type of interventions that could be included, but it does not intend to be exhaustive.

- interventions to address financial barriers for women to use skilled attendants;

- interventions to improve access to services by removing geographical and/or financial barriers;

- interventions to regulate midwifery;

- interventions to mobilize the community in favour of delivering with a skilled attendant;

- interventions to provide skilled attendant at home or at a health facility; - interventions to provide incentives for institutional deliveries;

- interventions on human resources development and/or deployment;

- interventions to find new roles for the TBAs, including role as a companion at birth; advocacy; teaming approaches which partner a TBA with a midwife or with the health centre, etc;

- interventions to improve quality of the existing services;

- interventions on governance of the health sector (intersectoral support and legislation).

References that exclusively addressed the following topics were excluded: - places where TBAs were previously not attending births;

- places where TBAs are still attending births and no transition to skilled attendants is taking place;

- TBA training to upgrade skills for childbirth care;

- studies where TBAs are being supported in any way to continue to practice childbirth; - home-births not attended by TBAs;

- descriptions of women's preferences for care or factors that influence use of TBAs or skilled attendants services;

- HIV interventions or abortion interventions that do not describe TBA to skilled attendant transition;

- satisfaction studies of service utilization that do not describe the intervention for the transition.

3.4 Types of outcomes measures

As before, here are listed some examples of outcomes, but others related to these were included if reported in the included studies.

1) TBA activities:

- TBA advises to use health facilities for childbirth services; - TBA accompanies women to health centre;

- TBA as companion at birth; - % of births with TBAs.

2) Use of skilled attendant or health facility: - use of ANC;

- use of postpartum care; - use of postnatal care (PNC); - % of births in a health facility;

- maternal satisfaction with health facilities or skilled attendant for childbirth services.

3) Measure of maternal mortality: - maternal deaths;

- MMR.

4. Data collection and analysis

4.1 References selection and eligibility

The main review author4 performed the search between May 10th and June 17th 2010, and the following analysis of the titles and/or abstracts acquired from all the above cited sources were reviewed independently by two review authors that applied the eligibility criteria. The main review author reviewed all the retrieved references while one of the secondary authors, due to time constraints, reviewed 50% independently. When a reference was considered possibly relevant and the title and/or abstract were insufficient for a decision on inclusion/exclusion, the full text was retrieved and analysed. The main review author reviewed all the included or possibly relevant references that were then revised by one of the secondary authors, and any differences in opinion were resolved through consensus. References were classified as those to be considered inventory-only and those for the systematic data extraction. A second review was done of those references considered inventory-only and additional references were identified for data extraction.

4.2 Quality appraisal and data extraction of the included references

For the quality assessment of the included references, two different assessment tools were used: for qualitative methods, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) assessment tool (Annex 4, (36)) and for quantitative methods the McMaster University

High = quality of the research design and of the information reported in the publication corresponds to all the criteria outlined in the quality assessment tools and thus allows for confidence in the outcomes described.

Moderate = quality of the research design and of the information reported in the publication corresponds to some of the criteria outlined in the quality assessment tools and thus allows for some level of confidence in the outcomes described, but additional information on aspects of the research process would increase confidence.

Low = quality of the research design and of the information reported in the publication corresponds to few of the criteria outlined in the quality assessment tools and thus allows for less confidence in the outcomes described.

Inventory-only = those deemed very weak or with insufficient information to assess the quality.

Figure 7: Grading of the quality appraisal of the included references.

The two secondary authors were responsible for the first independently quality assessment process, which was then followed by several rounds of review and discussion by the three authors.

ANC, childbirth and PNC were extracted. Data extraction was performed by the main review author and in order to establish priorities and ensure consistency, there were several rounds of review and discussion between the three authors prior to proceeding.

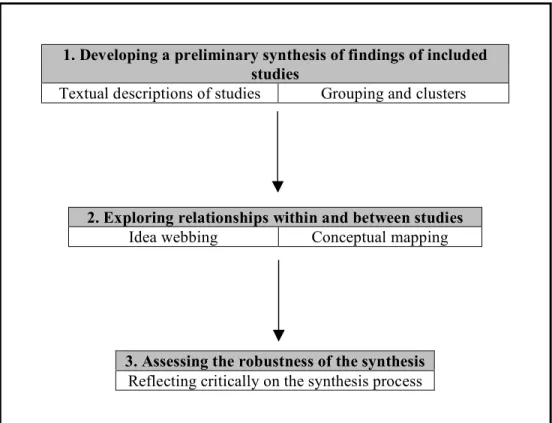

4.3 Method of synthesis of findings

In the present case of this review, a narrative synthesis approach was used to synthesize the findings.

1. Developing a preliminary synthesis of findings of included studies

Textual descriptions of studies Grouping and clusters

2. Exploring relationships within and between studies Idea webbing Conceptual mapping

3. Assessing the robustness of the synthesis Reflecting critically on the synthesis process

Figure 8:Flow chart of the narrative synthesis process.

Bringing more detail into the different steps of the process, the findings were organized and described after the relevant data from the included references was extracted, developing in this way a preliminary synthesis. For this two tools were used:

- textual descriptions of findings in the form of a paragraph describing the study in a systematic way and including the same type of information for all studies;

- groupings and clusters of the included studies into smaller groups;

As patterns across studies begin to emerge from the preliminary synthesis, the next step was to explore relationships within and between studies using the following tool:

- idea webbing and conceptual mapping to visually represent the relationships being explored.

references as well as to the credibility of the result of the synthesis process. In this step the tool used was:

- reflecting critically on the synthesis process addressing methodology and evidence used, assumptions made and discrepancies and uncertainties identified.

R

ESULTS1. Results of the search

Figure 9: Flow diagram of the systematic search process and inclusion of references for the systematic review.

*: One reference was simultaneously placed in the group for the inventory-only and for systematic data extraction because it was composed of multiple

independent studies Included for inventory

91*

Included for data extraction 19* Excluded 224 Word document 694 Eliminated duplicates 242

References for analysis 452

Reference Manager file 16,120

Eliminated duplicates 6309

References for analysis 9811 Total of references for analysis

10,263

Excluded based on title and/or abstract

9576

Full text retrieved 300 Full text to be retrieved

for further analysis 687

Included 76 Included references received

from contacted people 33 FRANCIS 62 IndMED 119 KIT 82 Bioline 159 EMRO 11 La bibliothèque de

Santé Tropicale 1 Herdin 6 AIM 114 AJO 76 WHOLIS 64 African Women's Bibliographic Database 62 CINAHL 2090 Cochrane 104 Conference papers index 40 Dissertations and theses 186 Embase 2517 l'Ecole nationale de

2. Study characteristics

The sample of references5 used in this systematic review - both inventory-only and for

data extraction - included 62% of published papers, 18% of reports, 5% of PhD theses,

5% of book chapters, 3% of personal communications, 2% of conference proceedings,

2% of project information, 1% of master theses, 1% of books, 1% of journal blogs and

1% of organizations web-pages news. These references were from a total of 38 countries

(Figure 10).

Figure 10: Number of references per country.

In this systematic review the included references were separated in two categories:

references for systematic data extraction and references for inventory-only. The idea

behind the inventory-only list is to inform readers that these references are related to the

objectives of this review but do not possess enough information and/or quality to be

5

India 6 USA 10

Canada 1

Mexico 5

Malaysia 4

Indonesia 18 Mozambique 1

Cambodia 4

Peru 4

New Zealand 1 China 4

Thailand 1 Belize 1

Belgium 1

Jamaica 2

Multi-country 9 Uganda 2

Palestine 1

Lao PDR 1 Guatemala 1

Bangladesh 12

Nigeria 4

Ecuador 1

Chile 1 Bolivia 2

Sri Lanka 1 Ghana 4

Kenya 1 England 1

Burkina Faso 2 Senegal 1

Afghanistan 1

Sudan 1

Southern Sudan 1

Myanmar 1 Eritrea 1

included as a standard reference for systematic data extraction. However we felt that

these references are pertinent in this field and if the reader wishes to deepen his or her

knowledge on a specific country or intervention this list will be useful. Annex 7 contains

the totality of references (inventory-only and for systematic data extraction) detailing the

type of intervention and type of study per country. The ones that went further for

systematic data extraction are marked accordingly.

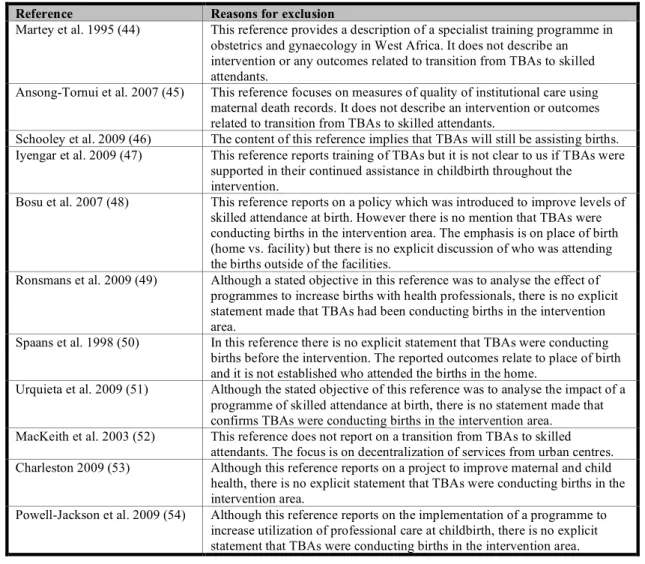

The majority of excluded references had no relation to the objectives of this review or

TBAs were still handling births, but a few almost made it in this review but were

excluded for some specific reason detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Characteristics of the excluded references.

Reference Reasons for exclusion

Martey et al. 1995 (44) This reference provides a description of a specialist training programme in obstetrics and gynaecology in West Africa. It does not describe an intervention or any outcomes related to transition from TBAs to skilled attendants.

Ansong-Tornui et al. 2007 (45) This reference focuses on measures of quality of institutional care using maternal death records. It does not describe an intervention or outcomes related to transition from TBAs to skilled attendants.

Schooley et al. 2009 (46) The content of this reference implies that TBAs will still be assisting births. Iyengar et al. 2009 (47) This reference reports training of TBAs but it is not clear to us if TBAs were

supported in their continued assistance in childbirth throughout the intervention.

Bosu et al. 2007 (48) This reference reports on a policy which was introduced to improve levels of skilled attendance at birth. However there is no mention that TBAs were conducting births in the intervention area. The emphasis is on place of birth (home vs. facility) but there is no explicit discussion of who was attending the births outside of the facilities.

Ronsmans et al. 2009 (49) Although a stated objective in this reference was to analyse the effect of programmes to increase births with health professionals, there is no explicit statement made that TBAs had been conducting births in the intervention area.

Spaans et al. 1998 (50) In this reference there is no explicit statement that TBAs were conducting births before the intervention. The reported outcomes relate to place of birth and it is not established who attended the births in the home.

Urquieta et al. 2009 (51) Although the stated objective of this reference was to analyse the impact of a programme of skilled attendance at birth, there is no statement made that confirms TBAs were conducting births in the intervention area. MacKeith et al. 2003 (52) This reference does not report on a transition from TBAs to skilled

attendants. The focus is on decentralization of services from urban centres. Charleston 2009 (53) Although this reference reports on a project to improve maternal and child

health, there is no explicit statement that TBAs were conducting births in the intervention area.

3. Analysis of references selected for systematic data extraction

The references included in this review for systematic data extraction were analysed using

a narrative synthesis approach, where the findings were organized and described after the

relevant data from the included references was extracted in the pre-designed data

recording table. References were grouped according to the type of intervention found in:

- Human resources development and/or deployment;

- Improvement of access to services by removing geographical and/or financial barriers;

- Cultural adaptation of institutional childbirths;

- Community advocacy.

Human resources development and/or deployment (Table 2)

In Indonesia, the impact of placing over 50,000 midwives in villages across the country

was studied through analysing retrospective pregnancy histories from three waves of the

longitudinal Indonesian Family Life Survey (1993, 1997, and 2000) (55). This village

midwife programme was initiated in 1989. The study documented place of birth and

attendant during childbirth in the full sample and in a sub sample of communities where

village midwives had been placed. Use of TBA at birth declined in both cases. In the full

sample 41.1% of births were attended by a TBA with a decrease over the years: from

51.5% (1988) to 27.8% (1999). In the communities with village midwives, 50.6% of

births were with a TBA with a decrease over the years: from 67.4% (1988) to 34.2%

(1999). Concurrently births with a midwife or a physician increased over the same time

period, which could reflect the effect of the programme. Home births also decreased

during this time period.

In another study (56) which assessed the effect of the village midwife programme using

the same three waves of the Indonesian Family Life Survey, the relationship between

increased access to midwifery services and changes in use of ANC and childbirth care

was examined. In this paper sequential pregnancies among women in “treated”

communities (those where a midwife was placed) were compared with changes for

women in “control” communities where a midwife was not placed. In both this, and the

communities that had less access to health services and where there was a higher reliance

on births with a TBA. In this study authors employed statistical models to take account of

the non random assignment of midwives and community settings; results for each method

varied slightly. The authors estimated logistic regression models for their analysis and

have shown that having a midwife available is positively and statistically significant

associated with receiving any ANC or ANC in the first trimester (0.22 with a standard

error of 0.11 and 0.47 with a standard error of 0.07, respectively) and with receiving iron

tablets during pregnancy (0.28 with a standard error of 0.09). On the other hand, having a

midwife available was negatively and statistically significant associated with having a

medically oriented delivery (-0.23 with a standard error of 0.07). This dual effect could

be due to a bias introduced by the unobserved individual or community characteristics

present in this model, like greater reliance on TBAs in the villages where the midwives

were placed. When these unobserved factors were eliminated from the model and an

individual and time specific fixed effect was included, where time-varying characteristics

of the mother were controlled (like monthly household expenditure per capita and

community resources and infrastructure), there was a stronger association – except for

receiving ANC in the first trimester – than in the logistic regressions. But in this case

even though the association was stronger, the coefficients were not as precisely estimated

and also because the standard errors were larger, having a midwife available was not

statistically significantly associated with receiving any ANC at all or during the first

trimester (0.49 with a standard error of 0.33 and 0.20 with a standard error of 0.20,

respectively). However, having a midwife available was positively and statistically

significant associated with receiving iron tablets during pregnancy (1.14 with a standard

error of 0.51). Unlike in the logistic regression where the coefficients for the village

midwife’s effect were negatively biased, with the mother-specific fixed effect, having a

midwife available was positively and marginally statistically significant associated with

receiving medically oriented delivery care (0.52 with a standard error of 0.29). And so,

the placement of village midwives in communities in Indonesia resulted in changes in

health care use during pregnancy and childbirth relative to the patterns observed for

Another study (57) in two districts in West Java, Indonesia assessed the relationship

between midwife density along with other characteristics of provision and uptake of

maternity care with the percentage of births attended by a health professional and birth

with a caesarean section, using several sources of quantitative data, mainly census and

surveys. This study was set within the context of the village midwife programme,

described above. The authors reported that between 1 April 2004 and 31 March 2006

there was an increase of births with a health professional with increasing midwife density

from 23.11% with no resident midwife density to 65.27% with a density of six or more

resident midwives per 10,000 inhabitants. Women were also more likely to have a birth

with a health professional when living in a village with a health centre or with an increase

in the number of ANC visits. On the other hand, the percentage of births with a health

professional declined with the number of TBAs in the village from 34.83% in villages

with none to three TBAs to 23.77% in villages with six or more TBAs. Between 1

November 2003 and 31 October 2004, there was an increase in the percentage of births

with a caesarean section with increasing midwife density from 0.44% with no resident

midwife density to 3.71% with a density of six or more resident midwives per 10,000

inhabitants. While for the same period there was a decline in births with a caesarean

section with the number of TBAs in the village from 1.25% with none to three TBAs to

0.98% with six or more TBAs. Distance to the nearest hospital was noted to be an

important correlate for birth with a health professional. The midwife's status and the

length of her work experience in a community together with women's education and

wealth were also important factors.

Maternal health policies in Bangladesh have also concentrated on facilitating access to

skilled care by placing professional birth attendants at the village level. In Matlab,

Bangladesh a historical cohort study conducted between 1987 and 2001 analysed births

recorded through a surveillance system and pregnancy monitoring records (58). In this

site, a home-based trained attendance strategy was initiated in 1987 and gradually

replaced by a facility-based approach in 1996. Both services were free of cost. The study

examined if the home-based approach was associated with a more equitable utilization

5% in 1987 to 20% in 1992 was reported. The proportion of births in a facility increased

from 0% in 1987 to 27% in 2001. However, the authors reported that there were

differences in the utilization patterns per wealth quintile, with higher levels of use of the

least poor compared to the most poor; these were similar for home and facility based

obstetric care.

Another study in Matlab, Bangladesh evaluated the efficacy of a maternity-care

programme in the reduction of maternal mortality in the context of a community-based

maternal and child health and family planning (MCH-FP) project (59). The maternity

care programme was implemented in only half of the MCH-FP project area, in order to

provide a control area. The authors did a comparison of direct obstetric maternal

mortality ratios between the programme and control areas employing death forms and

medical reports. Through the maternity care programme, trained midwives were posted in

villages to provide ANC and PNC, attend births in the home and refer complications to a

maternity clinic. They also linked to community health workers and TBAs. The study

found that the risk of obstetric death in the intervention area was significantly lower than

in the control area during the years after the beginning of the programme (1987 - 1989)

than during the preceding years (1984 - 1986) - obstetric mortality ratio declined from 3.9

to 3.8 in the control area and from 4.4 to 1.4 in the intervention area. This study reported

that 15% of all registered pregnant women had requested the programme midwives to

attend them during childbirth, but only in 9% was the birth attended by the midwife

herself while in 4% the midwife was present but allowed either a TBA or a female

paramedic to deliver the baby and in 1% the midwife was on her way. The authors

provided several possible explanations for this low coverage of midwives at home births

including distance, household factors and birthing women's preferences, etc.

In another study in Bangladesh (60), in a non-specified area, a programme was initiated

in 2003 by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare of Bangladesh that trained family

welfare assistants and female health assistants in perinatal care in the community. An

evaluation of the pilot project in six upazilas was conducted six months after the training.

and focus group discussions (FGDs). The study reported that in those areas served by

skilled birth attendants, 29% of births were attended by them; 47% by TBAs; and 24%

were attended by medically-qualified persons. In those areas not served by skilled birth

attendants, TBAs attended the majority of births (61%) and the remaining 39% were

attended by medically-qualified persons. Although the community recognized the

benefits and quality of the skilled birth attendants’ services, they explained that their

continued reliance on TBAs was because skilled birth attendants were unable to attend

Table 2: Characteristics of the references that reported on interventions for human resources development and/or deployment.

Reference Country Aims/objectives

of the study

Study description/ methodology

Context/Intervention description

Outcomes/results Quality

appraisal

Shrestha 2007 (55)

Indonesia Analyse the impact of the village midwife programme on infant mortality.

Retrospective pregnancy histories of ever-married women from three waves (1993, 1997 and 2000) of the longitudinal Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS) were used. In 1993 various members of 7224 different households were interviewed (22,000 individuals) and 94.4% were re-contacted in 1997 and 95.3% in 2000.

The village midwife programme (bidan di desa) initiated in 1989 has trained and placed over 50,000 midwives in villages across the country. The midwives were recruited after three years of nursing training and were given one more year of midwifery training to provide antenatal, intrapartum and postpartum care to village women. They also promoted community participation in health, worked with TBAs and referred complicated cases to health centers and hospitals.

They were paid by the government for three to six years and were then expected to start private practice.

Delivery place

In the full sample, the total number of live births was 7943: 309 (1988), 801 (1999).

- 57.5% of births were at the woman or a family member house with a decline over the years from 63.8% (1988) to 48.7% (1999). - 19.8% of births were at the midwife’ office with an increase over the years from 13.3% (1988) to 25.7% (1999).

- 14.2% of births were at hospitals with an increase over the years from 12.0% (1988) to 16.9% (1999).

- 3.7% of births were at the village delivery post (puskesmas) which were more or less maintained over the years from 3.2% (1988) to 4.1% (1999).

- 2.1% of births were at the physician’s office which were more or less maintained over the years from 2.9% (1988) to 3.4% (1999). - 1.6% of births were at the TBAs office which were more or less maintained over the years from 1.6% (1988) to 1.1% (1999).

In the communities with village midwives, the total number of live births was 5421: 190 (1988), 559 (1999).

- 68.2% of births were at the woman or a family member house with a decline over the years from 79.5% (1988) to 58.1% (1999). - 15.8% of births were at the midwife’s office with an increase over the years from 7.4% (1988) to 23.6% (1999).

- 9.5% of births were at the hospital with an increase over the years from 5.3% (1988) to 11.6% (1999).

- 2.7% of births were at the village delivery post (puskesmas) which were more or less maintained over the years from 2.1% (1988) to 3.2% (1999).

- 1.7% of births were at the TBAs office which were more or less maintained over the years from 1.6% (1988) to 1.4% (1999). - 1.1% of births were at the physician’s office which were more or less maintained over the years from 1.1% (1988) to 2.0% (1999).

Primary assistance during delivery

In the full sample, the total number of live births was 7939: 309 (1988), 800 (1999).

- 44.7% of births were with a midwife with an increase over the