UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO CEARÁ

FACULDADE DE ECONOMIA, ADMINISTRAÇÃO, ATUÁRIA, CONTABILIDADE E SECRETARIADO EXECUTIVO

PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ADMINISTRAÇÃO E CONTROLADORIA

MESTRADO ACADÊMICO EM ADMINISTRAÇÃO E CONTROLADORIA

FRANCISCO SAVIO MAURICIO ARAUJO

STRATEGIC RESPONSES TO GLOBAL CLIMATE CHANGE: EVIDENCE FROM CANADIAN OIL COMPANIES

STRATEGIC RESPONSES TO GLOBAL CLIMATE CHANGE: EVIDENCE FROM CANADIAN OIL COMPANIES

Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Administração e Controladoria da Faculdade de Economia, Administração, Atuária e Contabilidade da Universidade Federal do Ceará, como requisito parcial para obtenção do Título de Mestre em Administração e Controladoria. Área de concentração: Gestão Organizacional.

Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Mônica Cavalcanti Sá de Abreu.

Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação Universidade Federal do Ceará

Biblioteca Universitária

Gerada automaticamente pelo módulo Catalog, mediante os dados fornecidos pelo(a) autor(a)

A1s ARAUJO, FRANCISCO SAVIO MAURICIO ARAUJO.

STRATEGIC RESPONSES TO GLOBAL CLIMATE CHANGE: EVIDENCE FROM CANADIAN OIL COMPANIES / FRANCISCO SAVIO MAURICIO ARAUJO ARAUJO. – 2018.

154 f. : il.

Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Federal do Ceará, Faculdade de Economia, Administração, Atuária e Contabilidade,Programa de Pós-Graduação em Administração e Controladoria, Fortaleza, 2018. Orientação: Prof. Dr. Mônica Cavalcanti Sá de Abreu.

1. Mudança climática. 2. estratégia de carbono. 3. empresas de energia. I. Título.

FRANCISCO SAVIO MAURICIO ARAUJO

STRATEGIC RESPONSES TO GLOBAL CLIMATE CHANGE: EVIDENCE FROM CANADIAN OIL COMPANIES

Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Administração e Controladoria da Faculdade de Economia, Administração, Atuária e Contabilidade da Universidade Federal do Ceará, como requisito parcial para obtenção do Título de Mestre em Administração e Controladoria. Área de concentração: Gestão Organizacional.

Aprovado em: ___/___/______

Banca Examinadora:

_________________________________________ Profª. Drª. Mônica Cavalcanti Sá de Abreu (Orientadora)

Universidade Federal do Ceará

_________________________________________ Profª. Drª. Silvia Maria Dias Pedro Rebouças

Universidade Federal do Ceará

_________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Anil Verma

AGRADECIMENTOS

Em primeiro lugar a Deus, que me permitiu chegar aos dias de hoje e ter a oportunidade de me desenvolver, desenvolver conhecimento e poder contribuir para a construção de uma sociedade melhor.

Em seguida, a meus pais, que garantiram minha educação, me deram carinho, amor, educação, se esforçaram para que eu chegasse até aqui, estão guardados em lugar especial em meu coração.

A minha orientadora, que me conduziu de forma coerente e reflexiva, sempre querendo o meu melhor.

A minha esposa que entendeu meu distanciamento, mas que se manteve compreensiva durante toda minha jornada

Aos meus irmãos e irmãs, cunhadas, cunhados, sobrinhos, tios e tias, que também contribuíram com meu crescimento e com a pessoa que hoje sou.

Aos meus coordenadores e colegas de trabalho que me apoiaram, me incentivaram e reconheceram meu comprometimento e minha necessidade de ir buscar meus sonhos.

Aos amigos que ganhei no mestrado, junto de quem enfrentei momentos difíceis e com quem compartilhei momentos maravilhosos.

RESUMO

Este trabalho aplica o modelo de estratégia de mudança climática para entender como as características organizacionais, as pressões institucionais e as perceções gerenciais de riscos e oportunidades afetam as estratégias de carbono das grandes empresas poluidoras de CO2 no Canadá. A fim de alcançar o principal objetivo, este artigo propõe identificar os agrupamentos de empresas e seu posicionamento em relação às estratégias climáticas corporativas e investigar o papel das partes interessadas, principais preocupações e problemas enfrentados pelas empresas no contexto canadense. O Canadá possui uma economia baseada em recursos, de matriz fóssil e, ao mesmo tempo, possui uma política climática desacelerada com a participação das empresas confinada as atividades defensivas de lobby. Por estas razões, justifica-se como um interessante ambiente analítico. Este trabalho é teoricamente apoiado pela teoria baseada em recursos, teoria institucional e teoria das partes interessadas. Os resultados são baseados em uma pesquisa com 127 gerentes de empresas de petróleo e gás e 18 entrevistas semiestruturadas com principais interessados no ambiente canadense (Acadêmicos, ONGs e governo) sensíveis às questões relacionadas às mudanças climáticas. Os dados da pesquisa foram trabalhados através de análise fatorial, modelagem de equações estruturais e agrupamento, enquanto as entrevistas foram avaliadas através da análise do discurso das partes interessadas em uma abordagem quantitativa-qualitativa. Os resultados mostram que as empresas adotam uma das quatro estratégias diferentes, desde uma abordagem “minimalist”

passando por “regulation shaper”, “pressure manager” ou “emission avoider”. Este trabalho contribui para a compreensão da importância dos efeitos da mudança climática em um modelo de negócios no mercados canadenses de petróleo e gás.

ABSTRACT

This work applies the climate change strategy model in order to understand how organizational characteristics, institutional pressures, and managerial perceptions of risks and opportunities affect the carbon strategies of large CO2 polluting firms in Canada. In order to achieve the main objectives, this paper proposes to identify the key clusters and their positioning in relation to corporate climate strategies and to investigate the role of stakeholders, main concerns, and problems faced by companies in the Canadian context. Canada is a leader resource-based economy built upon a fossil matrix and at the same time, a climate policy laggard with business participation confined to defensive lobbying activities. For these reasons, it is justified as an interesting analytical environment. This work is theoretically supported by resource-based, institutional, and stakeholder theories. The findings are based on a survey with 127 managers of oil & gas companies and 18 semi-structured interviews with key stakeholders of Canadian environment (Academics, NGOs, and government) which are sensitive to climate change issues. The survey data is performed through factorial analysis, structural equations modeling and clustering while the interviews were evaluated through content analysis of stakeholder´s speech in a quantitative-qualitative approach. The results show that companies undertake one of four different strategies ranging from a minimalist approach to the regulation shaper, pressure manager or greenhouse gas emission avoiders. This work contributes to an understanding of the importance of embedding climate change in a business model in Canadian oil and gas markets

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1 - Sources of provincial electricity generation in Canada in 2015 ... 23

Figure 2 - Canadian crude oil production in 2016 ... 24

Figure 3 - The Algae process. ... 36

Figure 4 - Corporate climate change strategy model………...40

Figure 5 - Path diagram - Corporate climate change strategy model ... 44

Figure 6 - Data collect flowchart ... 48

Figure 8 –Nodes………...59

Figure 9 - Path diagram of CFA –Climate change risk ………...73

Figure 10 - Path diagram of CFA - Perceived stakeholder pressure...78

Figure 11 - Path diagram of CFA - Carbon management practices... 82

Figure 12 - Path diagram of CFA - Performance perception... 87

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1 - Regulatory context for climate change policies in Canada ... 20

Table 2 - Overview of Canadian oil industries ... 25

Table 3 - Carbon strategy typologies ... 27

Table 4 - General response strategies to GHG reduction pressures ... 46

Table 5 - Demographic distribution of interviewees... 56

Table 6 - Relationship between climate change strategies elements, data collection and research question...59

Table 8 - Size...61

Table 9 - Foreign ownership...62

Table 10 - Supply chain...63

Table 11- Production and technology...64

Table 12 - Position of interviewee in the company...64

Table 13 - Work area of interviewee in the company...65

Table 14 - Climate change risk in companies...67

Table 15 - Perceived stakeholder’s pressure on companies...68

Table 16 - Carbon management practices by companies...68

Table 17 - Performance perception of managers...69

Table 18 - Exploratory factorial analysis: Climate change risk...71

Table 19 - KMO and Bartlett’s test: Climate change risk...71

Table 20 - Communalities: Climate change risk...72

Table 21 - Results of Confirmatory Factorial analysis: Climate change Risk... 73

Table 22 - Goodness-of-fit indices: Climate change risk...75

Table 23 - Exploratory factorial analysis: perceived stakeholder pressure...76

Table 24 - KMO and Bartlett’s test: perceived stakeholder pressure...76

Table 25 - Communalities: perceived stakeholder pressure...77

Table 26 - Confirmatory factorial analysis results: Perceived stakeholder pressure...78

Table 27 - Model adjustment indices: Perceived stakeholder pressure...79

Table 28 - Exploratory factorial analysis: Carbon management practices...80

Table 29 - KMO and Bartlett’s test: Carbon management practices...80

Table 30 - Communalities: Carbon management practices...81

Table 31 - Confirmatory factorial analysis results: Carbon management practices...81

Table 33 - Exploratory factorial analysis: Performance perception of managers...85

Table 34 - KMO and Bartlett’s test: Performance perception of managers...85

Table 35 - Communalities: Performance perception of managers...86

Table 36 - Confirmatory factorial analysis results: Performance perception...88

Table 37 - Model adjustment indices: Performance perception of managers...89

Table 38 - Results of the exploratory and confirmatory factorial analysis...89

Table 39 - SEM Results...91

Table 40 - Model adjustment índices...92

Table 41 - Result of cluster analysis...93

Table 42 - Characteristics of companies in different clusters...96

Table 43 - General response strategies to GHG reduction pressures...98

Table 44 – Climate change risks from Stakeholders perspectives ...98

Table 45 – Climate change risks from companies perspectives ...103

Table 46 – Stakeholder pressure from Stakeholders perspectives...104

Table 47 – Stakeholder pressure from companies perspectives...108

Table 48 – Carbon management practice from Stakeholder perspective...109

Table 49 – Carbon management practice from companies perspectives...111

Table 50 – Perceived performance perception from Stakeholder perspective ...113

Table 51 – Perceived performance perception from companies perspective ...113

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

UNFCCC United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change GHG Greenhouse Gases

CDP Carbon Disclosure Project GDP Gross Domestic Product

OPEC Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries COSIA Canada’s Oil Sands Innovation Alliance

AER Alberta Energy Regulator

NGOS Non-governmental Organizations CDM Clean Development Mechanism OPG Ontario Power Generation EFA Exploratory Factorial Analysis CFA Confirmatory Factorial Analysis KMO Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin

AVE Average Variance Extracted SEM Structural Equations Models ML Maximum Likelihood

GLS United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change ULS Unweighted Least Squares

ADF Asymptotically Distribution-free RMR Root Mean Square Residual GFI Goodness of Fit Index NFI Normed Fit Index CFI Comparative Fit Index TLI Tuker-lewis Index

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1 INTRODUCTION ... 4

1.2 Problem Statement ... 8

1.3 Study objectives ... 9

1.3.1 General objectives ... 9

1.3.2 Specific objectives... 9

1.4 Thesis organization ... 9

2 LITERATURE REVIEW ... 10

2.1 Canadian environments ... 10

2.2 Regulatory environment ... 11

2.2.1 Canadian constitutional division of powers………...12

2.2.2 Regulatory context for climate change….……….....13

2.3 Domestic context of corporate environmental actions ... 16

2.4 Canada’s energy landscape ... 17

2.4.1 Oil and gas companies ... 18

2.5 Corporate climate change options ... 21

2.5.1 Typologies ... 21

2.6 Evaluation model of climate change effects ... 23

2.6.1 Risks related to climate change ... 23

2.6.2 Stakeholders pressure related to climate change ... 26

2.6.3 Strategic responses to climate change and carbon management practices ... 30

2.6.4 Strategic responses to climate change and performance perception ... 32

2.6.5 Carbon response strategy grouping...35

2.6.6 Relevant strategies of GHG reduction in oil and gas sector...36

3 METHODOLOGY ... 38

3.1 Quantitative analysis... 38

3.1.1 Population and sample selection ... 40

3.1.2 Questionnaire ... 40

3.1.3 Data collection ... 42

3.1.4 Data analysis...43

3.1.4.1 Factorial analysis...44

3.1.4.2 Structural equation modeling...47

3.1.4.3 Cluster analysis....49

3.2 Qualitative analysis... 49

3.2.1 Selecting the interviewees ... 50

3.2.2 Developing an interview protocol ... 52

3.2.3 Analyzing interview’s data ... 53

3.3 Triangulation of results with secondary data.....55

4 RESULTS ... 56

4.1 Quantitative analysis... 56

4.1.1 Descriptive analysis of sampling ... 56

4.1.2 Descriptive analysis of construct’s variables ... 61

4.1.3 Factorial analysis of construct’s ... 65

4.1.4 Structural Equations Modeling: selection of the empirical model ... 85

5 QUALITATIVE ANALYSIS... 90

5.1 Climate change risks...96

5.1.2 Perceived stakeholder pressure...99

5.1.3 Carbon management practices...103

5.1.4 Perceived performance perception...107

6 DISCUSSIONS ... 111

7 CONCLUSIONS...117

REFERENCES ... 118

APPENDICES A...131

APPENDICES B...135

APPENDICES C-1...138

APPENDICES C-2...140

1 INTRODUCTION

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), in its Article

1, defines climate change as ‘a change of climate which is attributed directly or indirectly to

human activity that alters the composition of the global atmosphere and which is in addition to natural climate variability observed over comparable time periods’. The UNFCCC thus makes a distinction between climate change attributable to human activities altering the atmospheric composition, and climate variability attributable to natural causes. (IPCC, 2007).

Climate change is related to the greenhouse effect. The phenomenon we now call the greenhouse effect is a natural mechanism by which certain gases retain the heat emitted from

earth’s surface. A range of different gases act as greenhouse gases, and their common

characteristics is that each can absorb heat emitted from Earth and re-emit that heat – keeping it on our planet longer (IPCC, 2012). Observed changes to Earth’s climate that are due to the

additional anthropogenic GHGs retaining and emitting heat cause climate change. And this is in agreement with the work of several scholars, for example Hansen (1988) said that humans have added more than their fair share of greenhouse gases (GHGs) into the atmosphere and are now heating Earth too much and quickly. These human-caused, or anthropogenic, greenhouse effects are caused mostly by high concentration of the so-called “long lived” greenhouse gases, such as CO2, methane, nitrous oxide, and chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) gases (IPCC, 2012).

As Braasch (2013) reports, sea level increases affect millions of people around the world, and billions of dollars in property. In addition to homeless people, coastal areas’ fishing activities, tourism and the real estate market suffer. Sea level is increasing and the rate of such increase is accelerating. The combination of ocean water expansion from warming and rapid increase of polar ice melting has worsened the rate of sea level from an average of 17.27 centimeters during most of the last century to a current rate of 30 to 35 centimeters. Based on this increase in the rate of elevation, scientists estimate that by the end of this century, the oceans will rise from 50.8 centimeters to 91.4 centimeters this forecast has become increasingly.

Industries account for the largest share of emissions and are the actors that can most contribute to a change to a more favorable environment scenario. According to Rosen (2007), the development of business strategies, public policies, market mechanisms and innovative technologies towards a low carbon society is required in view of this problem. However, in the political context, where different countries have different positions on the future of international climate policies, companies are exposed to a very high level of regulatory uncertainty (KOLK; PINKSE, 2004; HOFFMANN; TRAUTMANN; HAMPRECHT, 2009).

It is difficult to predict how the regulatory framework will change when India, China and the United States, three of the five largest emitters, are still reluctant to make commitments (HARRISON; SUNDSTROM, 2007), even knowing of recent efforts by China to leave this group of environmentally backward countries to explore opportunities of bilateral cooperation with Germany, particularly in the area of emissions trading (MCC, 2017).

In the light of this, some companies tend to adopt a "wait and see" approach until the rules of the game become clearer (KOLK; PINKSE, 2004; BOIRAL, 2006; JESWANI; WEHRMEYER; MULUGETTA, 2008).This inertial behaviour, according to Boiral, Henri, & Talbot (2011), is reinforced by the uncertainty about the economic impacts of actions that companies can take to reduce GHG emissions. Surprisingly, these impacts remain relatively little studied despite the intensification of the international debate on this controversial issue. So, while companies are reluctant to address climate change issues in a consistent way, industrial activity, driven by growing societal demand, further aggravates the risks of this inaction.

energies and financial instruments aimed at the carbon market (HOFFMAN, 2006; KOLK; PINKSE, 2009). However, efforts are still shy toward a steady reduction. According to recent Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) results and despite increasing attention to climate change, many companies have not reduced their absolute GHG emissions (SLAWISNKI et al., 2017).

Canada is particularly interesting because, in this country, the energy sector is accounted

for approximately 10 per cent of Canadian’s GDP in 2013. The energy sector’s share of the GDP

was at or close to this percentage for the decade preceding 2013 (IMF, 2014). Canada is a net energy exporter, responding to global energy demand.

According to Canada’s government, among the G-20 countries, Canada is the 5th largest overall energy producer, and has the 5th largest energy surplus (production minus consumption). This country has the third largest global crude oil reserves in the world, Oil and Gas is a key driving force in the Canadian economy and accounts for close to 18% of all Canadian export.

At the same time that it is a great energy producer and exporter, it is also a great polluter. In 2010, oil and gas sector GHG emissions accounted for approximately 22% of all emissions in Canada, 7% of total emissions are from oil sands (SAINT-JACQUES; 2012). Therefore, in the global context, Canada is leader-edge player based on resource-dependence economy built upon a polluting energetic matrix, while at the same time, according to some scholars, Canada, has earned a reputation of climate policy laggard, and its business participation is traditionally confined to defensive lobbying activities (EBERLEIN; MATTEN, 2009). For these reasons, Canada is justified as a key element in this study.

It is also deeply tied to the environment because, obviously, the burning of fossil fuels cause air pollution and climate change. Moreover, companies, as a significant contributor to climate change and beneficiary of externalizing environmental costs, have an obligation to address their environmental impacts. Notwithstanding the necessity for firms to take action, there is limited progress in offering insights into firm adaptation mechanisms to climate change (PINKSE; GASBARRO, 2016). In fact, there is little work in the management literature that assesses the implications and consequences of climate change that firms and industries may need to adapt to (LINNENLUECKE; GRIFFITHS; WINN, 2013).

economy sector in its position of high competitiveness and pressure by the growth frame of its corporate climate change options vis a vis its competitors and the enhancement of their own chances of survival.

Nevertheless, empirical studies have been carried out to describe corporate climate change options (WEINHOFER, HOFFMANN, 2010; SPRENGEL; BUSCH, 2010; WEINHOFER; BUSCH, 2012; LEE, 2011; JESWANI; WEHRMEYER; MULUGETTA, 2008). However, reviews of these models shows a need for more elements or criteria to operationalize them (ABREU; FREITAS; REBOUÇAS, 2017).

Other studies have been developed to describe factors influencing corporate climate change strategy, including regulatory framework, societal demand, market positioning and technology availability (PINKSE; GASBARRO, 2016; CADEZ; CZERNY, 2016; JESWANI; WEHRMEYER; MULUGETTA, 2008). However, there is a lack in the body of knowledge related to using other factors that affect carbon strategies, such as organizational characteristics, institutional pressures, and managerial perceptions of risks and opportunities.

In the oil and gas companies, the risks of climate change are diverse, ranging from physical, regulatory to market damage. With regard to physical risks, those companies rely heavily on available natural sources and any natural disaster due to climate change, such as droughts and floods, could jeopardize the availability of energy. Regulatory risks involve increasing the requirement to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emission and more stringent legislation. The market-related risks are due to the fact that the energy sector is a highly competitive sector in terms of new energy demands and technology use (LASH; WELLINGTON, 2007; JONES; LEVY, 2007).

In addition to the risks inherent in climate change, another factor has changed the way companies respond to the issue of climate change. Their stakeholders, especially government, shareholders and customers, are pressuring companies to take measures that minimize the effects of climate change (WEINHOFER; HOFFMANN, 2010). As such, companies adopt strategic responses to climate change compensation and innovation.

efficiency, reducing costs, and improving the company's image and reputation (SCHULTZ; WILLIAMSON, 2005; HOFFMANN, 2006).

The complexity of the interrelationships among various facets of GHG reduction strategies requires the use of more comprehensive analytical models. It should incorporate multiple, non-linear interactions between the diverse variables that shape these strategies and their possible impacts (BOIRAL; HENRI; TALBOT, 2011; BÖTTCHER; MÜLLER, 2015). Abreu et al., (2017) proposes a conceptual model to corporate climate change strategy development that reflects the dynamic influence of climate change risks and stakeholder’s

pressures on carbon management practices adopted and the performance perception of managers. Using clusters analysis of 105 Brazilian energy firms, this study explained how managers apply carbon management practices to reduce ecological uncertainty caused by the firms’ direct dependence on nature and how stakeholders influence firm reactions to climate change. The results showed that companies undertake one of four different strategies ranging from a minimalist approach to the regulation shaper, pressure manager or greenhouse gas emission avoiders.

Based on this perspective, the present study aims to test and validate a structural model proposed by Abreu; Freitas; Rebouças (2017) through quantitative and qualitative analysis. The output of quantitative analysis is the firm’s grouping into strategic orientations that will be confirmed and expanded by content analysis of Canadian institutional actors in climate change strategies context. In this way, the results provide contributions to the literature on business responses to climate change, adding new empirical evidences of interrelationship between actors of corporate climate change strategies model chosen and their implications for business in Canadian oil companies.

1.2 Problem Statement

To shed more light on climate change options on the Canadian energy sector, we apply a conceptual model for developing the climate change strategy that seeks to answer two questions: (1) Do climate change risks and stakeholder requirements act as driving forces of carbon management practices? In addition, (2) what effect do carbon management practices have on a

1.3 Study objectives

1.3.1 General objectives

Understand the strategic positioning prevalent in Canadian oil and gas companies and the consequent main reasons and implications.

1.3.2 Specific objectives

a) Apply the corporate climate change strategies model provided by Abreu et al., (2017) b) Identify key clusters of companies based on their corporate climate change strategies. c) Verify the positioning of companies regarding climate change issue.

d) Investigate the role of stakeholders and companies, principal concerns, problem faced, institutional peculiarities, regulatory environment and future perspectives of oil and gas companies.

1.4 Thesis organization

The remainder of this dissertation is organized as follows. First, in section 2, we present the Canadian environment outlying its regulatory context and the policies of climate change development, characteristic of Canadian oil and gas companies, and several GHG emissions mitigation actions by the oil sector. After that, in the same section, we describe corporate climate change options with their typologies, and interlink the field of analysis with a valuation model of climate change effects. Then, we develop hypotheses linking the four elements of the corporate climate change model.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 Canadian environments

Canada is the second largest country in the world in landmass and the largest in coastline (CANADA, 2015). Canada has fewer people than California (38.8 million in 2014 and a land size of 423,967 km2) even though California is smaller than Saskatchewan (651,900 km2). Canada is huge but sparsely and unevenly populated. Most Canadian live in one of Canada’s four most populated provinces (Ontario, Quebec, British Columbia, and Alberta), and, in 2014, about

35 per cent live one of Canada’s three largest census metropolitan areas: Toronto, Montreal and

Vancouver. The distribution pattern means that vast areas of the country are unpopulated (OLIVE, 2017).

In terms of natural resources, there is an uneven mix. British Columbia is known for its forestry and hydroelectricity; Alberta for its oil, coal and some forestry. Also in the West, Saskatchewan contains vast supplies of potash, uranium, natural gas, and some oil; Manitoba has mining and some oil and forestry. Central Canada possesses hydroelectricity, minerals and forestry resources, and the Atlantic Provinces have the fisheries and some oil and minerals. (OLIVE, 2017). The North has water, fisheries, oil, gas, and minerals such as diamonds and gold (CANADA, 2013).

These natural resources first attracted Europeans to Canada and Canada has been developing and exploiting these resources ever since it became an independent country (MACDOWELL, 2012). Canadians use a lot of energy and produce a lot of energy. On both ends

For much of the twentieth century, the settlement and development of northern Canada has been experienced by Aboriginal people as a continuing process of encroachment on (and sometimes transformation of) their traditional territories, and of restriction of their customary livelihood. Examples of this process included the alteration of river systems by impoundment and diversion, the pollution and contamination of river systems, government restrictions on hunting and fishing and population relocation and sedentarization.

For this and other reasons, the relationship between Canadian government and the indigenous communities is very sensitive. The government has been looking for approval and co-sponsorship of his energy projects but the message from the indigenous community is: We do not trust the government. In part, this is due to the inertia of the government to legitimate this

community’s voice by right of being consulting and veto on environment legislations.

One great example is the Northern Gateway pipeline project that involves many levels of government, First Nations, industrial energy interests, and the international community. The developer Enbridge, Inc. claims that this project can contribute substantially to local economies, it was reported that many aboriginal groups opposed this project (CANADA, 2012). For example, a coalition of 6 First Nations groups called Yinka Dene Alliance has pledged to oppose the Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipeline.

Their declaration states that they will not allow the Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipelines or any projects associated with the tar sands to cross their land. Because there are so many stakeholders with their own ideas about what is most important, it is difficult to get everyone at the table in a fair way, and much harder still to come to a decision. However, if the developer can prove the positive impact of the project on Canadian economy and efficiently reduce the environmental damage associated with the pipeline, the conflicts among the stakeholders then are likely to be minimized (CHIA et al., 2015).

2.2 Regulatory environment

the legal framework of business and which govern its ethical, social and environmental responsibilities (EBERLEIN; MATTEN, 2009).

Regulation is normally issued by governmental bodies or supranational institutions with governmental authority, such as the European Union (EU) Commission or the WTO. On a generic level then, one could assume that complying with regulation is an intrinsic part of the ethical conduct of business (EBERLEIN; MATTEN, 2009). Before entering the regulatory context, it is important to understand the division of powers between federation and provinces because in terms of environmental issues, there is a complex jurisdiction, which sometimes cause competition or omission between them.

2.2.1 Canadian constitutional division of powers

The Constitution of Canada grants authority to the federal government for peace, order and good government along with various specified areas of jurisdiction. For any area of jurisdiction not explicitly assigned to provincial legislatures, the so-called residual powers are assigned to the federal government. The relevant specific powers granted to the federal government are: a) granting exclusive federal jurisdiction over trade and commerce including inter-provincial and international trade including export of crude oil, oil and gas pipelines, and transport across provincial and international boundaries, b) granting exclusive federal jurisdiction over navigation (navigable waters), and c) granting exclusive federal jurisdiction over inland fisheries (CANADA, 2018).

Furthermore, the relevant specific powers granted to the provincial government are granting exclusive provincial jurisdiction over the management and sale of public lands and granting exclusive provincial jurisdiction over exploration development, conservation, and management of non-renewable natural resources within a province (CANADA, 2018).

whereby provinces and the federal government will adopt bilateral agreements to address concurrent jurisdiction (GOSSELIN et al, 2010).

Obviously, this division of power in the regulatory environment between the federal government, provinces and municipalities that sometimes overlap and sometimes leave gaps creates barriers to the implementation of environmental policies in the Canadian energy sector, notably oil and gas companies. According to Eberlein e Matten (2009), not only the presence – but also the absence of – regulatory requirements affect the choices available to firms and shape the degree to which they can engage in proactive and innovative behavior.

In this perspective, a stringent regulatory regime may not only constrain but also enable certain strategic adaptations and proactive choices, while, in turn, business involvement and participation can be an important factor in regulatory framework stability and performance. Conversely, the lack of a coherent regulatory framework, resulting in uncertainty, may hamper innovative business responses, while also offering opportunities to shape a future regulatory framework (EBERLEIN; MATTEN, 2009).

2.2.2. Regulatory context for climate change

Adding to the complexity that comes from the sharing of attributions in the regulatory environment between federal, provincial and municipal governments, Canada, in term of regulatory regime, has earned a reputation as climate policy laggard, and business participation is traditionally confined to defensive lobbying activities. While other countries, like Germany, has been quite successful in meeting its emission reduction targets as set out in the Kyoto protocol, Canada has so far failed dramatically to comply with its Kyoto obligations (EBERLEIN; MATTEN, 2009). As an EU member country, Germany participates in the EU Emissions Trading Scheme, while Canada does not have any comparable regulatory approach and framework in place at the federal level. These contrasting attributes provide a perfect empirical terrain to study expected variations of the relationship between business ethics and regulation (EBERLEIN; MATTEN, 2009).

commits its Parties by setting internationally binding emission reduction targets. Recognizing that developed countries are principally responsible for the current high levels of GHG emissions in the atmosphere because of more than 150 years of industrial activity, the Protocol places a heavier burden on developed nations under the principle of "common but differentiated

responsibilities. “The Kyoto Protocol was adopted in Kyoto, Japan, on 11 December 1997 and

entered into force on 16 February 2005. The detailed rules for the implementation of the Protocol were adopted at COP 7 in Marrakesh, Morocco, in 2001, and are referred to as the "Marrakesh Accords." Its first commitment period started in 2008 and ended in 2012 (UNFCCC, 2017).

The Protocol, adopted in 1997 under the UNFCCC negotiations, includes commitments

(‘Kyoto targets’) by Annex B parties, which includes most developed countries, to achieve

emission reductions against base year emission levels. These reductions were to be achieved by the end of the Kyoto commitment period in 2012, which began in 2008 (IPCC, 2000, 2001, 2003; UNFCCC, 2005; LIU et al, 2016). Annex A of the Protocol lists five sectors/source categories, including energy, industrial processes, agriculture, waste, and solvent and other product use, which are used to calculate the carbon dioxide (CO2) equivalence of anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases (GHG) for developed countries from 2008 to 2012 (LIU et al, 2016).

Despite these international actions, Canada’s emissions increased dramatically by over

21% compared to the 1990 baseline, putting Canada almost 30% above its Kyoto target by 2006. Since the early 1990s, Canada has relied primarily on non-compulsory, voluntary approaches and policies to address climate change, eschewing emission caps, regulation and taxation as policy instruments. This approach is unlikely to achieve the government’s new overall commitment of

a 20% reduction from 2006 levels by 2020, let alone the much more ambitious Kyoto targets based on 1990 levels (JACCARD; RIVERS, 2007).

Table 1 - Regulatory context for climate change policies in Canada

Period Policies Outputs

1997- 2012 Kyoto protocol: Signed and ratified 2008-2012 GHG reduction

targets commitment period 1990 as base year

Target 6%

1990 - 2005 Early phase -30% over target, non-compulsory and voluntary approach

Since 2005 Late phase -Federal level: setting of modest intensity targets, continuation of existing approach

-Provincial level: Ontario, Quebec (both plan cap and trade, British Columbia (eco tax) imposed some mandatory regulation

Since 2005 Drive of policy

approach -Political system -Federal powers relatively week, provincial power relatively strong;

-Majoritarian electoral system prevents green movement from gaining political representation

-Civil society -Week green movement

-International context -US position on climate change fueled fears of competitive disadvantage

Natural energy resource Strong opposition to

addressing climate change by energy-rich Western provinces Source: Adapted from Eberlein; Matten (2009)

developed and developing countries. In this context, major emitting nations submitted an emission reduction plan (all Annex I and 39 non-Annex I countries, including China and India) (UNFCCC 2011). However, little progress was made until 2011, when COP-17 in Durban launched a new negotiation stream with the objective to develop a new legal instrument applicable to all Parties, to be adopted by 2015 and to come into force in 2020 (UNFCCC, 2011).

One year after that, COP-18 in Doha finally established a second Kyoto commitment period (2013–2020), even though not all countries joined this effort: Canada, Japan and Russia officially declared they did not intend to commit for a second period, while the US confirmed that they would not join the Kyoto Protocol.

After all, the Kyoto Protocol did not reach enough international consensus to achieve the abatement level necessary to mitigate future climate change (CLARKE et al. 2014). The adoption of the long-awaited Paris Agreement in 2015, which allows each country to determine mitigation action at national level, officially proposed a bottom-up approach also for the post-2020 period. Before the new agreement becomes operative in 2020, the action in the coming years will rely on the second Kyoto commitment period for the few countries that adopted it, and on the voluntary pledges for the others (CAMPAGNOLO et al, 2016).

2.3 Domestic context of corporate environmental actions

In the Canadian domestic context, in December of 2011, the Government of Canada withdrew from the Kyoto protocol, becoming the only country to have signed and ratified the agreement and then withdrawn. The Government of Canada defended the move by acknowledging that they were not on track to meet their greenhouse gas emissions reduction targets and did not want to purchase international carbon credits to achieve their target.

in Canada ‘could significantly put the cost structure for Canadian industries out of line from what competitors in the U.S. are facing (BERNSTEIN, 2002).

While not disagreeing, environmental organizations and government officials also emphasize that relative inaction or a slow response in the context of U.S. action runs the opposite danger, since U.S. companies will have an advantage if incentives that promote innovations in energy-efficient technologies or renewable energy sources.

At the same time, global competitive pressures work in both directions. Militating against aggressive action, Canadian manufacturing in energy-intensive sectors such as steel or auto manufacturing may compete against developing country manufacturers in, for example, South Korea or Brazil, while energy supply companies may compete against operations in OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries) countries, none of which face mandatory emission targets. Conversely, Kyoto may signal a broader shift to a less carbon-intensive global economy, which means the marketplace, will favor more carbon-efficient, eco-efficient and energy-efficient companies (BERNSTEIN, 2002).

In terms of domestic actions, Carbon policy is addressed in Canada by both the provincial and federal governments. The main policies are British Columbia´s Climate Action Plan,

Alberta’s Climate Change Strategy, Ontario Climate Change Policy, Quebec Climate Change

Action Plan and Canadian Federal Government´s Action on Climate Change.

This leads us to conclude that it is not the lack of international or domestic policy and market tools to reduce emissions but rather, in the Canadian context, the challenge to reduce GHG emissions while the global demand for energy is growing.

2.4 Canada’s energy landscape

The energy sector plays an important role in Canada’s economy, contributing about 10% of gross domestic product, employing approximately 270 000 people and was

responsible for about 18% of Canada’s exports in 2016. The energy sector contributes about

Figure 1 - Sources of provincial electricity generation in Canada, TWh in 2015

Source: UNFCCC (2017)

Energy resources are unevenly distributed across the country and most energy policy is determined at the sub-national level, resulting in diverse energy systems across provinces and territories. In the electricity sector for instance, certain provinces rely primarily on hydro resources (British Columbia, Quebec, Manitoba and Newfoundland and Labrador), while coal, and increasingly natural gas, play a major role in Alberta, Nova Scotia, and Saskatchewan. Nuclear energy makes up over 50% of the generation mix in Ontario, while the northern territories rely on hydro for grid-connected communities and diesel generation for off- grid areas (IEA, 2017). See Figure 1.

2.4.1 Oil and gas companies

The total Canadian oil resources are estimated at approximately 172 billion barrels,

exports go to the United States, with Canadian crude oil accounting for around 28% of total US crude imports in 2016 (CAPP, 2017).

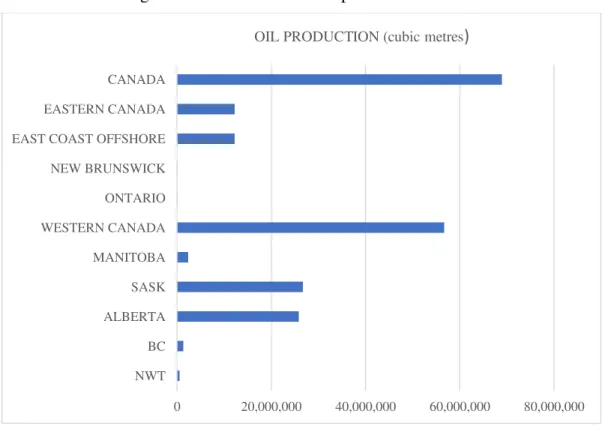

Canada's oil and natural gas industry is active in 12 of 13 provinces and territories. Alberta is Canada's largest oil and natural gas producer and is home to vast deposits of oil sands. Saskatchewan is Canada's second largest producer of oil. There are continued advancements being made in the development of new, more efficient technologies and reduced impact on the environment. British Columbia province is Canada's second largest natural gas producer. Alberta, British Columbia, Manitoba and Saskatchewan form the territory called Western Canada, which is primarily responsible for the production of petroleum in Canada, see figure 2 below. Nova Scotia has two producing natural gas projects and several companies are actively exploring offshore. Ontario's manufacturing sector is an important supplier for Canada's oil sands industry. Quebec in an important province because of new and significant deposits of natural gas from shale rock discovered along Québec's St. Lawrence Lowlands in 2008.

Figure 2 - Canadian crude oil production in 2016

Source: CAPP (2016)

0 20,000,000 40,000,000 60,000,000 80,000,000 NWT

BC ALBERTA SASK MANITOBA WESTERN CANADA ONTARIO NEW BRUNSWICK EAST COAST OFFSHORE EASTERN CANADA CANADA

Although a major producer and exporter of natural gas, Canadian natural gas production

is slowly declining. The country’s domestic production stood at 156.5 bcm in 2012, down from

187 bcm in 2005. Production levels are expected to continue to slowly decrease in coming years, reaching 154 bcm in 2018. Despite the decline, Canadian domestic production still exceeds domestic demand by around 55%. Domestic demand for gas in 2012 stood at around 100 billion cubic metres (bcm), leaving 56 bcm available for export that year. All this surplus production is exported to the United States. The natural gas market in Canada – and in North America as a whole – is resource-rich, efficient, vast, competitive and diversified (IEA, 2014).

The oil industry is dominated by a few large vertically integrated companies sharing many features. Moreover, the firms are classified into upstream operations (exploration and production of oil and gas), midstream operation (that involves the transportation, storage, and wholesale marketing of crude or refined petroleum products) and downstream operations (refining, distribution, and selling of oil and gas products). Most companies have traditionally been centralized due to the need for vertical and horizontal coordination. Table 2 shows an overview of main Canadian oil and gas companies, organized in sectors with dates of revenues, number of employees and percentage of market share related to total number of companies.

Table 2 - Overview of Canadian oil industries

Number of

companies Setor 2016 Revenue ($000s) Employees number Frequency (%)

64 producing and processing) Energy (Exploring, 187,135,03 70,788 66,0% 18 Oil & Gas service 958,723,98 25,595 18,6%

6 Engineering/Construction 7,729,12 5,851 6,2%

5 Utility/Pipelines 10,391,55 11,735 5,2%

4 Transportation 11,141,31 23,775 4,1%

Source: Author

afield to electricity generation and unrelated businesses such as office automation. (LEVY; KOLK, 2002).

2.5 Corporate climate change options

2.5.1 Typologies

The main goal that is behind our research is to shed light on why, despite increasing pressure to deal with climate change, firms have been slow to respond with effective action. For theoretical support, an appropriate corporate climate change framework was chosen in order to better understand the role of firms in reducing their absolute greenhouse gas emissions. However, we will first define what corporate climate change strategies are, show some relevant works in this area, their main contributions and justify the chosen model.

There are several definitions for climate change in business strategy. For example, Corporate CO2 strategy, carbon strategies, climate strategy (KOLK; PINSE, 2004) and business response to climate change (WEINHOFER, HOFFMANN, 2010; HOFFMAN, 2006; JESWANI; WEHRMEYER; MULUGETTA, 2008). These terms, which express subtle differences, have been used in various different contexts.

Lee (2012) defined corporate climate change strategy as a selection of the scope and level of carbon management activity. Weinhofer and Hoffman (2010) defined it as a pattern of activities associated with the management of direct and indirect GHG emissions. It can also be seen, according Sprengel and Busch (2011) as a set of goals and plans aimed at reducing GHG emissions and addressing changes in processes, markets and public policy. Kolk and Pinkse

(2004) considered the climate strategy to be a firm’s choice between among various strategic options in response to climate change. Jeswani, Wehrmeyer and Mulugetta (2008) focused on

the degree of a firm’s proactivity in response to carbon reduction requirements.

conceptually derived set of interrelated principles (LEE, 2012). Key outcomes from these continuum and typology models are presented on Table 3.

Table 3 - Carbon strategy typologies

Author (s) Key outcome(s) of research

Lee (2012) - Different levels of stakeholder pressure lead to different carbon strategies - Energy-intensive industries are liked to see opportunities and reduce risks - Financial performance and firm size were significantly related to carbon strategy Jeswani et al.

(2008) - Country, sector, size and ownership type influence carbon strategy - Owners, managers and regulatory agencies have more influence on carbon strategy - Cost saving, management commitment, corporate targets and regulatory compliance are most important drivers

Levy and Kolk (2002)

- Regulatory expectation, business-government conduct norms and fossil fuels assumptions influence carbon responses

- Institutional context of MNC’s home country, past investments losses and the specific history of each company influence carbon strategy

Kolk and Pinkse

(2005) -Emission trading schemes lead companies to compensate emissions instead of reducing -Companies are still in a preliminary phase regarding implementation of markets strategy - Development of climate strategies are to some extent path dependence

Weinhofer and Hoffmann

(2010)

- Large companies and high CO2 emissions undertake a broader spectrum of carbon strategies

- Significant differences among companies’ strategies in the E U, Japan and the USA Sprengel and

Busch (2011) - There are different sources of stakeholder pressures for each carbon response - Stakeholder pressures seem to be higher for companies that actually reduce their GHG emissions

Gasbarro, Rizzi and Frey

(2016)

- Changes in ecological resources induce precautionary measures, short-term adaptation and investments in innovation.

- Adaptation measures are driven by contingent resource availability and expected changes in market and policy.

Gasbarro and Pinske (2016)

- Companies perceive climate physical impacts differently

- Extreme climate event lead companies to reconsider their strategy and vulnerability Cadez and Czerny

(2016) -strategic priorities (internal carbon reduction, external carbon reduction and carbon Proposed conceptual framework of the climate change mitigation strategy includes three compensation), five alternative strategies to pursue these priorities and 19 constituent carbon practices.

Dahlmann et al (2016)

-Found evidence that only absolute targets, longer target time frames, and greater levels of target ambitiousness are associated with improvements in environmental performance Taebi and Safari

(2017) - Use ofcondemnation of such behaviour’ as effectively corporate climate change strategy. naming or ‘‘the public identification of noncompliance’’ and shaming or ‘‘public Damert et al

(2017) - positive effect of institutional and stakeholder pressure on emission reduction activities -positive relationship between carbon reduction activities and long-term improvements in carbon performance

Backman et al (2017)

- identifies investments in four firm-level resource domains (Governance, Information management, Systems, and Technology) to develop capabilities in climate change impact mitigation

These studies add to corporate climate change strategies body of knowledge and improve our understanding of carbon operational and management activities, and differences among

countries, industrial sectors and company’s size. However, there are also other factors affecting

carbon strategies, such as organizational characteristics, institutional pressures, and managerial perceptions of risks and opportunities.

This research has focused on this broad constructs of climate change strategies and the model of Abreu et al., (2017) integrating this dimensions into a framework through an empirical study of Brazilian energy companies. Whereas this framework can generate, among firms within or across industries, a different output, it is relevant to know the behavior of Canadian oil and gas firms by means of this corporate climate change model. Afterwards, it is proposed to classifying the Canadian firms into carbon response strategies groups with almost exclusively data-driven and based on Sprengel and Busch (2010) typology. In the next section the model of corporate climate change strategies chosen in their respective constructs will be detailed.

2.6 Evaluation model of climate change effects

2.6.1 Risks related to climate change

The model for corporate climate change strategy proposed by Abreu et al., (2017) incorporates the dynamic nature of these various factors discussed in previous sections which together lead firms to decide on a rational approach in light of the ecological uncertainty. The first element of the modelinvolves risk identification.

Lash and Wellington (2007) stated that executives typically manage environmental risk as a threefold problem of regulatory compliance, potential liability from industrial accidents and pollutant release mitigation. But climate change presents business risks that are different in kind because the impact is global, the problem is long-term, and the harm is essentially irreversible. This scholar proposed six categories of climate change risks:

a) Regulatory: Regulatory risk takes the form of controls on GHG emissions which can affect manufacturing process and products;

c) Supply chain:Supply chain risks can take the form of higher component and energy costs as supplier pass along the carbon-related cost to their customers;

d) Product and technology: Product and technology risks are those factors that influence the exploitation of new markets opportunities for climate-friendly products and services; e) Reputational: There are also reputational risks if companies face judgment in the court of public opinion, where they can be found guilty of selling or using products, processes, or practices that have a negative impact on climate change;

f) Physical:There is a physical risk posed by global warming and its effects;

According Kolk and Pinkse (2004), whether government regulation is viewed as a business risk or opportunity strongly depends on the type of industry. The most notable industries that perceive it as a risk are oil and gas, mining, metals and utilities. This is not surprising in view of the fact that emission reduction regulation is mainly directed at these industries. In the current design of the EU emissions trading scheme, for example, energy activities, the production and processing of metals, the mineral industry and the pulp and paper sector will be subject to a cap on greenhouse gas emissions. Government regulation is viewed as an opportunity by some financial companies, which believe that they can assist customers that are affected by such regulation through facilitating their emission trading or financing offset projects for them.

In the Canadian context, for example in Alberta province, the department of energy is responsible for developing the emission reductions policy. The Alberta Energy Regulator (AER), subordinate to energy department, is responsible for doing quality assurance, i.e., implementing that policy. The principal emission policy nowadays in this province is to reduce the methane emission by 45% by the year 2025 (ALBERTA, 2015). So, the Alberta regulator is responsible for implementing this policy through the introduction of regulations or requirements to the oil and gas industry, the largest source of methane emissions (25 times greater than carbon dioxide impact over a 100-year period) (ALBERTA, 2017).

The AER put in place the project called Measurement, Monitoring, and Reporting. This is where AER developing a system where companies will report their emissions. The AER assesses emissions based on their companies reporting. The AER can also go out and do its own audits to gauge compliance with their requirements. The AER doesn’t analyze the emissions

Porter and Reinhardt (2007) state that there is no one-size-fits-all approach to climate change. Each company’s approach will depend on its particular business and should mesh with its overall strategy. For every company, the approach must include initiatives to mitigate related costs and risks in its value chain. Every firm needs to evaluate its vulnerability to climate-related effects such as regional shifts in the availability of energy and water, the reliability of

infrastructures and supply chains, and the prevalence of infectious diseases. The firm’s leaders

should systematically assess these risks and then decide which to reduce through redesigning operations, which to transfer to others through insurance or hedging contracts, and which to bear. For some, but not all, companies, the approach to climate change can go beyond operational effectiveness and become strategic.

In working with firms as they assess their exposure to climate change and begin to develop climate strategies, Lash and Wellington (2007) found that the most successful efforts include four key steps, each of which requires strong leadership at the top and involves significant learning across the organization.

a) Quantify your carbon footprint;

b) Assess your carbon-related risks and opportunities;

c) Adapt your business in response to the risks and opportunities; d) Do it better than your competitors;

This work addresses the risks related to climate change and classifies them into three groups: market risks, regulatory risks and physical risks. Market risks refer to the risk of competitors developing environmentally responsible products and / or technologies and increasing demand for low GHG energy. Regulatory risks refer to regulatory restrictions related to emission reductions, such as the adoption of more restrictive legislation, fines and penalties, and increased enforcement. The physical risks are related to the physical impacts that the climate changes can cause to the company through natural disasters, lack of water availability, extreme climatic events, among others.

According to Abreu et al., (2017) , all of these risks can lead companies to fare better or worse than others in a carbon-constrained future.

Hypothesis 1: Increased climate change risks have a positive influence on the adoption of

carbon management practices by firms.

2.6.2 Stakeholders’ pressure related to climate change

The classic definition of a stakeholder is any group or individuals who can affect or is affected by the achievement of the organization's objective (FREEMAN, 1984). Interest in the concept of stakeholder has increased in recent years. Scholarly works on the topic of stakeholder theory that exemplify research and theorizing in this area include: Donaldson and Preston (1995), Mitchell, Agle, and Wood (1997), Friedman and Miles (2002),and Phillips; Freeman and Wicks. (2003).

There is a clear relationship between the definitions of what a stakeholder is and the identification of who the stakeholders are. The most common way of classifying a stakeholder is to consider groups of people with a distinguishable relationship with a corporation. The most common groups of stakeholders to be considered are:

a) Shareholders; b) Customers;

c) Suppliers and distributors; d) Employees;

e) Local communities.

In the strategic management aspect, the best-known model of management stakeholder is that proposed by Mitchell, Agle and Wood (1997). They proposed that an organization should

measure each stakeholder’s salience and then based on; it this should decide how to prioritize the needs of that stakeholder group. Stakeholder salience consists of power, urgency and legitimacy of the stakeholder group. If all three are present then the stakeholder requires a great deal of attention and must be prioritized within the strategic management of that organization. (COOPER, 2004)

These perceived differences in sources of stakeholder pressures then affect managers

formulating a response strategy. Hence the corporate response would reflect the differences in

The key issue is whether stakeholders are confined to those that are crucial for the achievement of corporate objectives or if they are merely any entity affected by corporate actions, especially if the latter includes alternative actions the corporation could have taken in order to achieve the objectives, but were not chosen (FRIEDMAN; MILES, 2006).

This study adopts two main types of stakeholders: primary stakeholders and secondary stakeholders or market stakeholders and non-market stakeholders.

According to Clarkson (1995), a primary stakeholder group is one without whose continuing participation the corporation cannot survive as a going concern. Primary stakeholder groups are typically are comprised of shareholders and investors, employees, customers, and suppliers, together with what is defined as the public stakeholder group: the governments and communities that provide infrastructures and markets, whose laws and regulations must be obeyed, and to whom taxes and other obligations may be due. There is a high level of interdependence between the corporation and its primary stakeholder groups.

According to Clarkson (1995), secondary stakeholder groups are defined as those who influence or affect, or are influenced or affected by, the corporation, but they are not engaged in transactions with the corporation and are not essential for its survival. The media and a wide range of special interest groups are considered as secondary stakeholders under this definition. They have the capacity to mobilize public opinion in favor of, or in opposition to, a corporation's performance. The corporation is not dependent on secondary stake-holder groups. Such groups, however, can cause significant damage to a corporation.

In the Canadian environment, it is important to outline the role of think tank organizations like Pembina institute and Canadian West Foundation. These “non-market” organizations are responsible for producing well-researched and highly-regarded reports and policy analyses. Because such reports often get media coverage and influence government policy makers, they

can be seen as fulfilling an important “interest group-like” function in climate governance in Canada (Olive, 2016).

Companies need to determine how the interests of their stakeholders relate to their goals and then move forward to establish mutually cooperative relationships. Environmentally concerned stakeholders create uncertainty for firms by threatening to withhold critical resource because of poor corporate environmental performance (ABREU; FREITAS; REBOUÇAS, 2017).

Regarding the adoption of environmental strategies, the stakeholder theory has contributed in a significant way. According to Gago and Antolin (2004), the natural environment has become an element of great importance in corporate social action, and the stakeholder theory has been fundamental in achieving a more practical view of corporate social responsibility to help top managers in their decision-making. Thus, it is interesting to study the stakeholders that can significantly influence corporate environmental management, or who are affected by it.

González-Benito and González-Benito (2008) show that the pressures of stakeholders contribute to the environmental proactivity of companies. These scholars in another work, González-Benito e Suárez-González (2010), investigate the effects of six relevant variables on stakeholder’s environmental pressure perceived by industrial companies: size, internationalization, location of manufacturing activities, position in the supply chain, industrial sector, and managerial values and attitudes. Throughout a sample of 186 Spanish manufacturers, the analyses reveal two dimensions of stakeholder pressure, governmental and nongovernmental, and show that variables such as environmental awareness among managers, internationalization, industrial sector and company size play important roles in determining both dimensions.

Sprengel and Busch (2010) stated that companies have to respond to stakeholder’s

consumers and investors are increasingly making decisions based on the environmental performance of a company including attention to climate change.

Abreu et al., (2017) claimed that another stakeholder response could be the general disclosure of the company’s efforts to reduce GHG emissions and engage in political debate. Companies can also increase their emissions limits by buying emission allowances, such as engaging in Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). On the Canadian market, there are usual CDM, carbon pricing policy and the disclosure projects discussed in previous sections.

However, Kolk and Mulder (2011) argued that since companies do not yet face stringent formal and informal constraints, they are not yet forced to take rational responses and may refrain from action altogether. From a market perspective, oil companies tend to be rewarded more for increasing the amount of oil they produce than for increasing the efficiency in producing that oil. There are many market incentives to produce. Renewable energy was explored in the 90s and the early 2000s, but then financially, they were all rewarded for divesting and selling those assets. Sometimes the market can encourage more focused or more short-term activities as opposed to longer-term, more diverse activities.

Kolk and Pinkse (2009) claimed that companies remain unprepared to deal with climate change, which shows considerable variety across locations not only in stakeholder expectations and government approaches but also in the locus and scope of potentially significant and unpredictable impacts.

Given these arguments the following hypothesis is proposed:

Hypothesis 2: Increased stakeholder pressures have a positive influence on the adoption of

carbon management practices by firms.

2.6.3 Strategic responses to climate change and carbon management practices

According Lee and Klassen (2015), carbon management practices or CMPs can be understood as systems and procedures that firms employ to respond to climate change, with a specific focus on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. They encompass a wide range of activities such as labeling (e.g. carbon footprint), reporting (e.g. carbon disclosure), new technologies (e.g. carbon capture and storage technologies) and financial trade-offs (e.g. emission trading schemes).

These practices are categorized regarding intra-organizational and inter-organizational areas. Intra-organizational CMPs are systems and procedures that primarily target internal activities related to climate change, such as product improvement, process improvement and employee engagement.

a) Product improvement means developing less carbon-intensive and/or more energy-efficient goods. In oil sands mining, sources of GHG emissions include the energy required to mine and transport the oil sands, to separate the oil from the sand, and to process the oil. In situ drilling operations require energy to generate steam that is then injected deep underground into the oil sands formation to warm the heavy oil so it can be pumped to the surface. Canadian oil

sands companies are working together, building on each other’s expertise and collaborating with

universities, government and research institutes on energy efficiency projects that help manage GHG emissions associated with oil sands production. One of these projects is the Algal Carbon Conversion Project (Algae Project), a pilot-scale bio-refinery that mixes CO2 emissions with algae to produce biofuel and biomass products (COSIA, 2017).

blended into heavy oil or synthetic crude oil. The leftover biomass can then be used to feed livestock and for land reclamation (COSIA, 2017). See Figure 3 bellow.

Figure 3 - The Algae process

Source: COSIA, 2017

b) Process improvement means improving energy efficiency and reducing emissions of GHG or substituting existing energy sources with cleaner and/or less carbon-intensive fuels. Examples include enhancing energy efficiency through better housekeeping and refurbishment (e.g. insulation) overhauling the entire production process and adopting the state-of-the art new process technologies (JESWANI; WEHRMEYER AND MULUGETTA, 2008; SCHULTZ; WILLIAMSON, 2005; WEINHOFER; HOFFMAN, 2010; LEE, 2012). In the Canadian context, in April 2014, Ontario Power Generation (OPG) stopped burning coal to produce electrical energy to Ontario converting its thermal electricity-generating stations to use biomass instead of coal. That was about 25% of generation and a huge amount of GHGs. The OPG are now, in terms of generation, 99% GHG-free (OPG, 2017).

c) Employee engagement emphasizes integrating carbon management issues into daily business routines. To do so, employees can be educated about environmental and/or

climate-change issues related to the firm’s operations, and given incentives to pursue lower targets for GHG emissions. Such a practice frequently serves as a catalyst for driving organizational change, which in turn facilitates product and process improvement CMPs.