UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA

FACULDADE DE LETRAS

DEPARTAMENTO DE ESTUDOS ANGLÍSTICOS

ENGLISH AS A LINGUA FRANCA IN RUSSIA:

A SOCIOLINGUISTIC PROFILE OF

THREE GENERATIONS OF ENGLISH USERS

Olesya Lazaretnaya

DOUTORAMENTO EM LINGUÍSTICA

Especialidade em Linguística Inglesa

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA

FACULDADE DE LETRAS

DEPARTAMENTO DE ESTUDOS ANGLÍSTICOS

ENGLISH AS A LINGUA FRANCA IN RUSSIA:

A SOCIOLINGUISTIC PROFILE OF

THREE GENERATIONS OF ENGLISH USERS

Olesya Lazaretnaya

Tese orientada pela

Professora Doutora Maria Luísa Fernandes Azuaga

DOUTORAMENTO EM LINGUÍSTICA

Especialidade em Linguística Inglesa

… as English becomes more widely used as a global language, it will become expected that speakers will signal their nationality, and other aspects of their identity, through English.

iv

Acknowledgements

I want to thank all the people who have contributed to this dissertation in various ways.

I am also bound to the Faculty of Letters of the University of Lisbon for accepting me as a PhD student and giving the opportunity to start this research.

Foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor Luísa Azuaga who took up this challenge to guide my research and allowed me to find my own line of work. Her experience and invaluable feedback especially in the final phase substantially improved this study. I would also like to thank her for helping to integrate into the Centre for English Studies at the University of Lisbon and also for offering me opportunities to work on diverse projects. It was precious experience for me.

I thank all my colleagues from the Research Group: Linguistics: Language, Culture and Society (RG5) for their generous encouragement in difficult times. Their enthusiasm, interest, motivation and zeal in carrying out various research projects always served as an example.

I am especially grateful to Susana Clemente for her help in processing questionnaire data and later on for her feedback on the questionnaire analysis.

I have furthermore to thank Alexander I. Lysikov, the head of the Moscow Regional Pedagogical College, situated in the Moscow region, Serpukhov, for allowing me to carry out the survey of student population, making up one of the focus groups of the empirical study of this research.

I would like to thank all the researchers who gave me food for inspiration and helped me to clarify my own understanding of issues under discussion. During my investigation, I have largely benefited from Barbara Seidlhofer, David Graddol, Elizabeth Erling, Jennifer Jenkins, Marko Modiano, and many other researchers.

I am also grateful to the group of Russian scholars and educators who contributed for the visibility of Russian studies into the English language by sharing their experience in volume 24 of World Englishes. Particularly, I am indebted to Zoya G. Proshina and Irina P. Ustinova who served as a source of inspiration.

My thanks go to Liudmila Iabs and António Mendonça for their help at different stages of this research.

Last but not least, I would like to give special thanks to my family whose love and encouragement made this research possible.

v

Resumo

Há muito que a língua inglesa ultrapassou as fronteiras das comunidades dos seus falantes nativos, sendo a sua expansão pelo mundo um fenómeno único e sem paralelo, intimamente associada ao seu reconhecimento como língua franca global. Este estatuto da língua inglesa como recurso universal e meio de comunicação internacional e intercultural justifica o crescente número de pessoas que usa esta língua: de facto, há, hoje em dia, mais gente a recorrer ao inglês como segunda língua e/ou como língua estrangeira do que há falantes nativos. Assim, a língua inglesa é actualmente um bem partilhado por milhões de indivíduos e comunidades, independentemente da sua identidade nacional ou geográfica.

Neste quadro, considerando o caso particular da Rússia, verifica-se que o inglês, neste país, surge num vasto leque de domínios como a educação, o trabalho, os media, a publicidade e muitos outros, sendo esta sua utilização frequentemente atribuída ao prestígio de que gozam os falantes de inglês nas esferas social, cultural e económica.

Sublinhe-se que, presentemente, a comunidade dos falantes de inglês na Rússia é maioritariamente composta por indivíduos para quem o inglês é uma língua estrangeira, no entanto, em função da proficiência e da situação envolvida, a língua inglesa aparece relacionada com realidades linguísticas diversas, incluindo variedades locais de inglês russo como o Runglish e o Ruslish. Porém, a penetração da língua inglesa na sociedade russa não é tão profunda como noutros países, dependendo as particularidades da situação do inglês no contexto nacional da política linguística que é, em grande medida, produto de estratégias políticas dentro e fora do país.

Como a compreensão do corrente estatuto do inglês neste país será impossível sem uma descrição retrospetiva da forma como a língua se desenvolveu historicamente no contexto nacional russo, tendo em mente certos fatores condicionantes, a difusão do inglês na Rússia é apresentada neste trabalho numa perspectiva simultaneamente diacrónica e sincrónica, baseada em três períodos fundamentais da história russa moderna: a Guerra Fria (1947-1991), o período pós-Perestroika (1992-1999) e a Nova Rússia (a partir de 2000).

O quadro teórico em que se desenvolve a investigação baseia-se numa conceptualização inovadora do inglês como língua internacional, ou língua franca, ultimamente considerado em largo uso nos países com comunidades de falantes não nativos de inglês. Este termo, vem sendo aplicável à língua, quando se verefica que o inglês passou a ser usado como meio de comunicação por um elevado número de indivíduos, para quem este,

vi

não sendo língua mãe, não pode ser visto como uma língua estrangeira, pois faz parte da sua vida quotidiana, ou é a língua utilizada em diversas situações.

Esta dissertação revisita também abordagens anteriores desta questão, de um ponto de vista de uma nova ordem linguística, tendo em conta contextos emergentes de aquisição da língua, o seu presente uso e utilizadores, e novas funções e instâncias de interação. O cerne da reflexão, porém, é a maioria dos falantes da língua, que são predominantemente falantes não nativos. Sublinha ainda o facto de que os usos internacionais do inglês em novos contextos geográficos, históricos, comportamentais, linguísticos e sociolinguísticos acaba por resultar numa diminuição das diferenças entre falantes nativos e não-nativos.

Uma vez que os processos de globalização e internalização têm implicações distintas para diferentes comunidades, dependendo largamente da história, politica, cultura e política linguística de cada país, o presente trabalho examina a presença do inglês num contexto nacional particular. Procura assim esclarecer o estatuto do inglês na Rússia e o modo como os russos são afetados pela sua presença, bem como a forma como a língua é adaptada ao contexto local, e como os indivíduos reagem ao seu uso.

Devido à sua situação histórica peculiar e aos anos em que a Cortina de Ferro dominou a vida europeia, o desenvolvimento das relações anglo-russas viveu períodos de altos e baixos. Vale a pena mencionar que a Rússia procurou resistir à influência da língua inglesa na língua e na cultura russas durante a maior parte da sua história. Antes de 1985, não existiam praticamente contactos entre a União Soviética e o Ocidente; esta situação alterou-se com as reformas da Perestroika, trazendo uma abertura ao Ocidente na política externa, na economia e nos modos de vida. No entanto, mesmo hoje, quando o país parece ter finalmente completado a transição para uma ordem democrática numa perspetiva globalizada, a resistência politica, económica, cultural, social e linguística à influencia do inglês permanece forte. Esta característica da paisagem linguística russa deve-se a uma politica governamental orientada para a proteção da identidade nacional e cultural pelo reforço da posição da língua russa. A maior contradição, porém, é que, na Rússia atual, o inglês é reconhecido como língua franca universal, sendo a mais popular das línguas estrangeiras, aprendida em todos os níveis do sistema educativo.

O trabalho inclui também uma pesquisa empírica focada em três gerações de falantes russos da língua inglesa que evidencia as atitudes perante a presença do inglês na Rússia, os seus usos, modelos e variações, bem como as suas perspetivas no contexto nacional. O levantamento pretende mostrar como as transformações na política linguística e na

vii

aprendizagem das línguas influenciaram as atitudes em relação ao inglês e ao seu desenvolvimento em ambientes específicos.

Os resultados desta pesquisa revelam que a aprendizagem da língua tem efeitos significativos nas atitudes e perceções dos indivíduos face à língua inglesa, à sua aquisição e aos padrões de ensino. A maioria dos falantes de inglês na Rússia ainda se confronta com perceções estereotipadas, impostas por tradições pedagógicas; em consequência, avaliam a sua proficiência pela proximidade com os falantes nativos - na sua maioria, demonstrando a sua preferência pelo inglês britânico e proficiência equivalente à nativa.

Defendendo o princípio de uma nova abordagem do inglês no quadro do seu ensino, acentua-se que, hoje em dia, o largo leque de domínios de uso do inglês torna problemático avaliar o lugar da Rússia no conjunto de países onde o inglês é ensinado e aprendido exclusivamente como língua estrangeira. A esta luz, um passo importante é a tentativa de estabelecer novos modelos e estratégias de ensino da língua inglesa, questionando os modelos tradicionais dos falantes nativos e as normas exonormativas do inglês como língua nativa, em favor da competência e eficiência comunicativa em contextos internacionais alargados.

Os resultados desta pesquisa sugerem a necessidade de reajustamentos significativos na pesquisa teórica, em linguística aplicada e no ensino do inglês. Tais mudanças incluem uma reavaliação em termos de falantes de inglês, da dicotomia nativo versus não-nativo, das noções de padrão e de variação, e dos domínios do uso linguístico. Estudos recentes também sustentam uma reorientação do ensino do inglês como língua franca, envolvendo o estudo do inglês em vários contextos, a consciência pedagógica e a aceitação de variantes linguísticas para lado do padrão, a mudança de uma abordagem monolingue para pluricêntrica no ensino da língua, e a enfase na aquisição de aptidões comunicativas.

Com este estudo, esperamos que as considerações e implicações teóricas aqui assinaladas para a linguística aplicada e o ensino da língua possam servir de base para pesquisas posteriores nestes campos e nos seus usos, no contexto específico da Rússia. Pesquisas mais abrangentes sobre o estudo da política e da ideologia linguísticas são também necessárias.

Palavras-chaves:

Inglês como língua estrangeira, inglês como língua franca, variação, inglês russo, ensino de inglês.

viii

Abstract

The current spread of English is closely associated with the acknowledgement of the language as a world lingua franca, having the processes of globalization and internatialization different implications for various communities, largely depending on the specific history, politics, culture, and language policy of the country.

In Russia, such unprecedented spread, most frequently attributed to the status ensured to speakers of English in social, cultural, and economic spheres, manifests itself in a range of domains such as education, workplace, media, entertainment, advertising, creative and identity domains.

In use both as a foreign language and, more widely, as a lingua franca, English in Russia builds links to the international community, and serves as a language of expression of national and cultural identity, being related to many Englishes, including such local varieties as Russian English, Runglish and/or Ruslish, depending on the level of proficiency of its users and the situation involved.

This dissertation examines the presence of English in the particular national context of Russia by focusing on three generations of Russian users of English. The findings of the empirical research bring to the surface the attitudes towards the presence of English, its usages, models, variation, as well as its prospects in the national context.

This survey suggests the need for significant readjustments in theoretical research, applied linguistics, and English teaching. Such changes include the reappraisal of the native versus non-native dichotomy, the notions of “standard” and “variation”, and domains of language use. In English language teaching, the reorientation involves the study of English in various contexts, teaching awareness and acceptance of other varieties besides standard ones, the shift from the monolingual to the pluricentric approach in language instruction, and the emphasis on the acquisition and development of communicative abilities.

Key-words:

English as a foreign language, English as a lingua franca, variation, Russian English, English language teaching.

ix

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments iv

Resumo v

Abstract viii

List of Abbreviations xii

List of Figures xiv

List of Tables xv

Introduction 1

1. English in Russia: Historical Development and Current Status 6

1.1. English-Russian relations: a general historical overview 7

1.1.1. The period of the Cold War 7

1.1.2. The post-perestroika period 13

1.1.3. The New Russia epoch 16

1.2. Today’s English presence in Russia 16

1.2.1. Tourism 17

1.2.2. Employability 20

1.2.3. Internet communication 21

1.3. Languages and Russian society 22

1.3.1. Attitudes towards English 23

1.3.2. Incentives taken to protect the Russian language 25

1.3.3. Multilingualism as a plus factor 27

1.4. Summary 30

2. New Approaches to English: Russian Contributions and Other Theoretical Insights

32

2.1. English studies: Russia’s catching up with the West 33

2.2. Rethinking English: approaches and models 36

2.3. Overview of recent developments in the research 44

x

2.3.2. ELF: clarifying comparisons and misconceptions 49

2.3.3. ELF: an English variety or English varieties 55

2.4. Summary 59

3. Russian English: Forms, Interferences and Domains 61

3.1. Positioning Russia among other English-speaking countries 62

3.2. Russian English: variety and variation 63

3.2.1. The many names of English: Russian Englishes 65

3.3. English influencing Russian 72

3.3.1. Major periods of borrowing 72

3.3.2. Lexical transfers and loan words: adaptation processes 74

3.3.3. Code switching 77

3.4. Domains of English in Russia 78

3.4.1. Domains of ELF 81

3.4.2. Domains of expression 83

3.5. Summary 95

4. English in Formal Education and Approaches in ELT 97

4.1. English in the Russian educational system 98

4.1.1. English in the structure of secondary education 98

4.1.2. Tertiary education 101

4.1.3. Private tuition 103

4.1.4. English in academic research 103

4.2. Standard language ideology 105

4.3. Challenging the traditional ELT models 107

4.3.1. ELF and EFL in ELT 110

4.3.2. Towards the Lingua Franca Core 114

4.3.3. ELF: form or function 123

4.3.4. ELF: fears and apprehensions 125

4.4. Summary 130

5. A Sociolinguistic Study of Three Generations of Russian Users of English 132

xi

5.1.1. Questionnaire composition 135

5.2. Questionnaire analysis 137

5.2.1. Section A: Personal information 137

5.2.2. Section B: Languages learning background 146

5.2.3. Section C: Competence, types of English and motivation 154

5.2.4. Section D: Language acquisition and preference for an English variety 160 5.2.5. Section E: Attitudes towards the use of English in everyday life 167

5.2.6. Section F: The future of English 175

5.3. Conclusion 181

Conclusion 186

References 194

Appendix I 204

xii

List of Abbreviations

AmE American English

BBC British Broadcasting Corporation

BES Bilingual English Speaker

BrE British English

CIS The Commonwealth of Independent States

CNN Cable News Network

EF English First

EFL English as a Foreign Language

EIIL English as an International Auxiliary Language

EIL English as an International Language

ELF English as a Lingua Franca

ELO The English Language Office (Moscow)

ELT English Language Teaching

ENL English as a Native Language

ESL English as a Second Language

ESOL English for Speakers of Other Languages

ESP English for Special (Specific) Purposes

EU European Union

FCE First Certificate in English (Cambridge)

FEELTA Far Eastern English Language Teachers’ Association FID International Federation for Information and Documentation

FU Freie Universität (Berlin)

GA General American

HEI Higher Education Institution

IATEFL International Association of Teachers of English as a Foreign Language

IAWE International Association for World Englishes IELTS International English Language Testing System

IL Interlanguage

ILEC International Legal English Certificate

L1 First Language

xiii

LATEUM Linguistic Association of the Teachers of English at the University of Moscow

LSP Language for Special Purposes

MA Master of Arts

MES Monolingual English Speaker

MTV Music Television

NATE National Association of Teachers of English (in Russia)

NBES Non-bilingual English Speaker

NS(s) Native Speaker(s)

NNS(s) Non-native Speaker(s)

NTV National TV Broadcasting (in Russia)

OECD Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

ORT ‘Public Russian Television’

PhD Doctor Doctor of Philosophy

RP Received Pronunciation (of British English)

SAT empty acronym, stands for a standardized test for college admissions in the United States

SPELTA St. Petersburg Language Teachers’ Association SPSS Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

TESOL Teaching of English to Speakers of Other Languages TOEFL Test of English as a Foreign Language

WE(s) World English(es)

WS(S)E World Standard (Spoken) English

UK United Kingdom

UNESCO United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization USA / US United States of America

USE Unified State Examination

USSR Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

VOICE Vienna-Oxford International Corpus of English

xiv

List of Figures

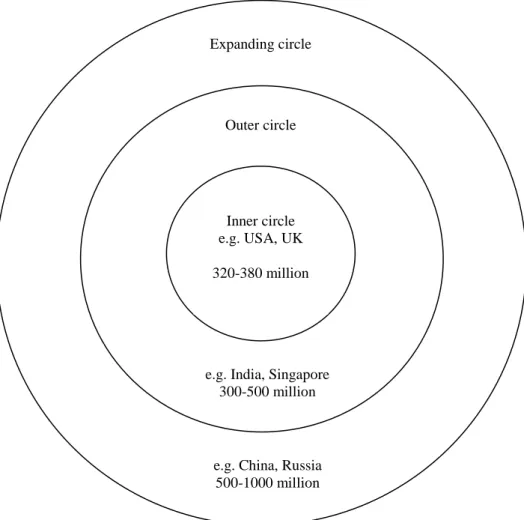

Figure 2.1. Kachru’s concentric circles of WEs 38

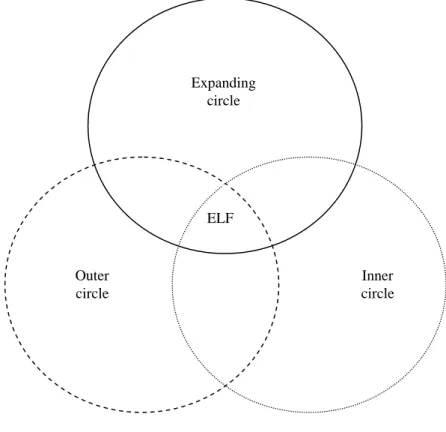

Figure 2.2. Graddol’s overlapping circles of English 40

Figure 2.3. Modiano’s centripetal circles of English 41

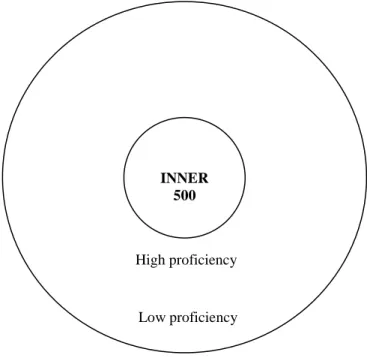

Figure 2.4. The circle of English conceived according to speakers’ language proficiency

42

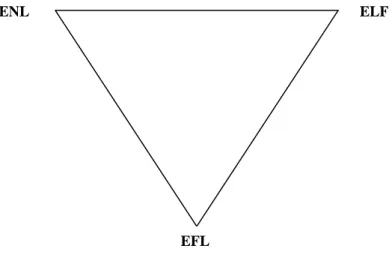

Figure 2.5. Kachru’s three-circle model as modified by Yano 43

Figure 2.6. Modiano’s circles of EIL speakers 47

Figure 2.7. Prodromou’s circles of WEs 48

Figure 2.8. McArthur’s circle of WE 52

Figure 4.1. Language acquisition targets for learners of EFL 112

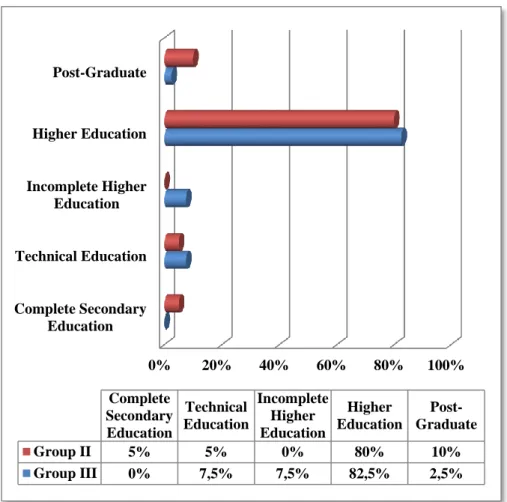

Figure 5.1. Levels of education by subjects from group II and group III 141

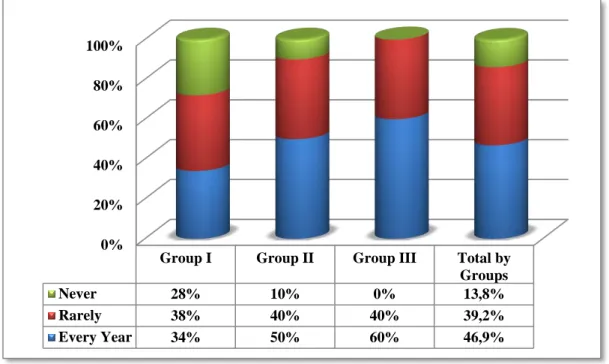

Figure 5.2. Amount of travelling 142

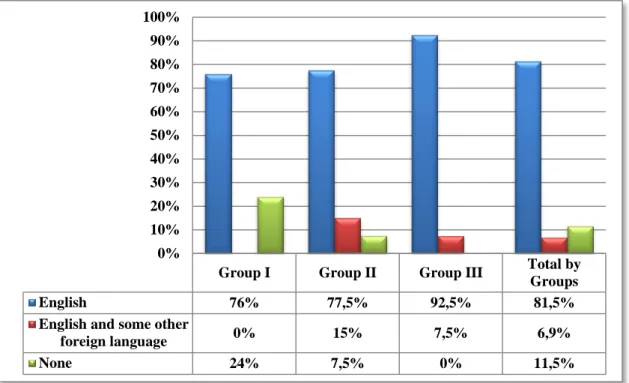

Figure 5.3. Language(s) used abroad to communicate 144

Figure 5.4. English-speaking countries visited by respondents 145

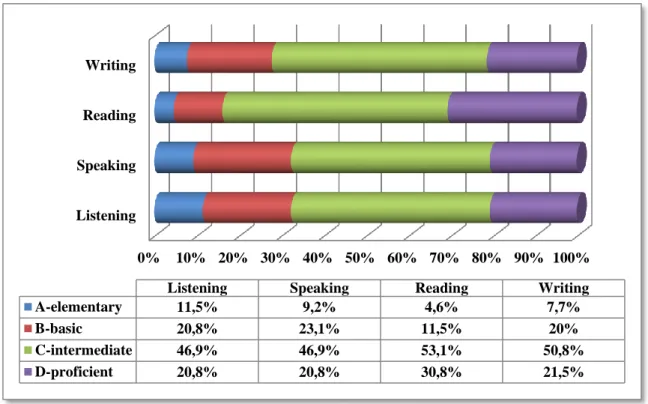

Figure 5.5. Language skills assessment 147

Figure 5.6. Knowledge of English and other foreign languages 149

Figure 5.7. English Plus 150

Figure 5.8. Group I: Language proficiency assessment 154

Figure 5.9. Group II: Language proficiency assessment 155

Figure 5.10. Group III: Language proficiency assessment 156

Figure 5.11. Respondents’ self-identification with the type of English they speak 157

Figure 5.12. Motivation to know English 159

Figure 5.13. The need to know English 160

Figure 5.14. Effective language acquisition means learning English… 161

Figure 5.15. Respondents’ opinion about the model variety to be taught at school 163

Figure 5.16. Respondents’ opinions about Standard English and English varieties 166

Figure 5.17. Respondents’ preference for a native-like variety 167

Figure 5.18. Respondents’ contacts with English 170

Figure 5.19. Respondents’ attitudes towards the use of English on TV and in films 171

Figure 5.20. Respondents’ opinions about the use of English in their speech 172

Figure 5.21. Respondents’ opinions about the presence of English in daily life 173

xv

List of Tables

Table 1.1. Top holiday destinations, in 2011 18

Table 2.1. Conceptual differences between EFL and ELF 55

Table 3.1. Survey carried out by the Heavy Metal portal 87

Table 4.1. Some distinctive features of ESOL vs. EIIL 113

Table 5.1. Age statistics, irrespective of focus groups 138

Table 5.2. Age group division 138

Table 5.3. Sex distribution 138

Table 5.4. Place of residence 139

Table 5.5. Occupation by level of education 140

Table 5.6. Top 10 holiday destinations 142

Table 5.7. Top holiday destinations by groups 143

Table 5.8. English-speaking countries visited by groups 145

Table 5.9. First foreign language 146

Table 5.10. Group I: Language skills assessment 147

Table 5.11. Group II: Language skills assessment 148

Table 5.12. Group III: Language skills assessment 148

Table 5.13. Foreign languages by their popularity among respondents in descending order

152

Table 5.14. Top three popular foreign languages by their popularity 152

Table 5.15. English educational background 153

Table 5.16. Respondents’ opinion about a native English teacher and a non-native

Russian teacher of English

162

Table 5.17. Respondents’ preference for British English and American English 165

Table 5.18. Respondents’ opinions about Standard English and English varieties 166

Table 5.19. Group I: Frequency of using English 168

Table 5.20. Group II: Frequency of using English 168

Table 5.21. Group III: Frequency of using English 169

Table 5.22. Respondents’ opinions about the use of English in speech by groups 172

Table 5.23. Opinions about English in Denmark, Germany and Russia 174

Table 5.24. Respondents’ opinions about the presence of English in daily life by

groups

175

xvi

Table 5.26. Importance of world languages among respondents 177

Table 5.27. Importance of world languages by groups 178

1

Introduction.

The spread of English is unprecedented and unparallel. No other language is so dispersed all over the world in myriads of its forms and uses in so many domains of everyday life as English. It is now universally acknowledged as a predominant world language whose status so far remains unrivaled by other world languages. “In the early 21st

century, English is not only an international language, but the international language” (Seidlhofer, 2011: 2).

So, in the framework of this research, the linguistic phenomenon under discussion is addressed as International English or English as a lingua franca which has come to mean “a language common to, or shared by, many cultures and communities at any or all social and educational levels, and used as an international tool” (McArthur, 2003b: 2).

In fact, there are more people using English as their second or international language than there are native speakers of it, and this unique situation the English language finds itself in nowadays makes it a possession of every individual or community, regardless of their national or geographical identity.

In a broad sense, this dissertation is focused on English and on the manifestation of its global spread, and in a narrower perspective, it studies a specific manifestation of English as a means of international and intercultural communication.

As Crystal notes, “A language achieves a genuinely global status when it develops a special role that is recognized in every country” (Crystal, 2003b: 3). In this meaning, “global” is interchangeable with “world”, in the sense that it “covers every kind of usage and use” (McArthur, 2003a: 2), and “international”, including all the communities where the label “English” is applied to many forms of the language: from native varieties to English used as a foreign language.

Furthermore, this research emphasizes the influence of English on the national discourse, and underlines how the English language is appropriated in national contexts,

2

taking into account the specific history, culture and politics to evaluate different outcomes. Therefore, it examines the spread of English in a particular national environment, giving insights into its presence in Russia.

This dissertation concentrates roughly on three major strands in theoretical research: 1. English as viewed from the global perspective (e.g. Crystal, 2003a and 2003b; Graddol, 1997 and 2006).

2. World Englishes paradigm, which approaches English from the viewpoint of its dissemination into different varieties of the language (e.g. Kachru, 1990 and 1992; McArthur, 1998 and 2003a; Melchers and Shaw, 2003), and the language in local contexts (e.g. Fonzari, 1999; Preisler, 1999).

English in the particular context of Russia is presented by Proshina, 2007, Ustinova, 2011, and a collection of papers, contributed by Russian scholars and educators to volume 24 of World Englishes.

Notice that, when a quotation from an original source written in Russian is included in this thesis (to be verified in the references list), its translation into English is by the author of this research.

3. The main body of research speaks in favor of approaches to English from a new perspective of English as a lingua franca, including research works by Breiteneder, Erling, Jenkins, Modiano, and Seidlhofer, among others.

For the convenience of this study, the research is divided into five chapters.

Chapter 1 provides with a detailed account of the spread and development of the English language in the specific national context of Russia from both a diachronic and synchronic perspective.

In the historical dimension, the development of English it related to the changes in political and economic strategy, largely affecting the language policy of the country. It may be noted as well that, in countries with communist regimes and centralized political systems, foreign language instruction is frequently availed of as a tool of political and ideological maneuvering.

For this reason, the account of the spread of English in Russia rests on three major periods of contemporary Russian history: the Cold War, the post-perestroika period and the New Russia epoch. It is largely through the close examination of the environment in which the English language operates and develops that the status of English, its spread and uses, as well as its implementation in teaching pedagogy are best understood.

3

In the contemporary dimension, chapter 1 highlights the presence of English in such contexts as tourism, employability and Internet communication in which the use of English is most frequently involved as a link to the international community. It also touches upon the issues of language protectionism and multilingualism, as being construed in the national context.

Chapter 2 is primarily concerned with the changing discourse about the English language. It is thus called “to close a conceptual gap”, – for, so far, the discourse about English has been concentrated predominantly on native speaker prescriptive norms and the acquisition of standard varieties.

This chapter first underlines the contribution of Russian linguists into English studies and points out those areas of research which are of particular interest to Russian scholarly community, still largely with the focus on standard varieties, although not exclusively, as the research has also shifted to countries in which English functions as a second official or dominant language.

Globally, however, already since the late 90s, a considerable bulk of research has been focused on English that emerges as the language of communication across linguistic and cultural boundaries, increasingly among people who may not have English as their mother tongue.

This new linguistic world order entails the reappraisal of the status of English speaker and language competence, and consequently of the type of English applied in new instances of intercultural exchange, themes which have come to be central to Russian researchers only in recent years.

Because of the ambiguity which may rise in the discourse about English, chapter 2 is also dedicated to explore current conceptions of the English language, and to establish consensus within the discipline and in the interdisciplinary discourse.

First, it reviews models and approaches that account for the spread of English primarily in terms of its speakers, and further validates the status of English as an international language or lingua franca, considering controversies and debates regarding this concept. Searching the way to better understand this new status of English, it is opposed to other terms for a comprehensive definition of the type of language used primarily among its non-native speakers.

Chapter 3 comes closer to the description of the English language from a synchronic perspective, including manifestations of different forms and uses of the language in the local

4

context. It also seeks to define the place of Russia among other English-speaking communities worldwide, grounding on the model of Kachru’s concentric circles of English.

Although in Russia the discourse about the English language is still bound to the traditional perceptions, in terms of its users and the type of English spoken in non-native communities, the English language used in the local contexts, as well as domains of its use allow referring the Russian community of English speakers to those countries, in which English functions as a lingua franca.

A description of the types and forms of English points out to the fact that, although within the national sociolinguistic and cultural contexts, the local variety of English is not recognized as an independent English variety, English in Russia has been diversified in a variety of forms that, nonetheless, have cultural and linguistic affinities to the native language of the people who use it.

In chapter 3, it is also argued that the extent in which the English language penetrates different domains of everyday Russian life establishes its status as a lingua franca in Russia. Thus the domains of its use has long ago surpassed the restricted contexts of tourism employability and Internet communication, increasingly expanding into different realms of everyday life, including intranational domains, in which English is used as a language of expression of cultural and national identity. As such, the domains of English in Russia are described within two major strands: domains, in which English is used as a lingua franca, and domains of expression.

To complete the description of the linguistic Russian landscape, as far as English is concerned, a general overview of the way the English language is implemented in Russian education system is given in chapter 4. It includes language acquisition at all stages of formal education, from kindergarten until the end of tertiary education, and further in university academe.

This chapter challenges “standard language ideology” as the traditional approach in English language teaching. It argues that conformity to Standard English varieties may be inefficient and counter-productive for those learners of English who need to operate in broader international settings.

As, nowadays, actual uses of English are increasingly those of a lingua franca, teaching targets for the majority of English learners cannot remain the same. It is thus attempted to provide grounds for introducing new teaching strategies in the classroom, with focus on intelligibility and communicative competence, rather than on the adoption of native

5

speaker norms and models, by promoting proposals of how this type of English should be taught, particularly with focus on Russian learners of English.

To test the awareness of new functions the English language fulfils in Russian society, as well as the possibility of introduction of new teaching strategies and models in ELT, it was considered to be relevant to examine various aspects of the English language in Russia, including attitudes towards the presence of English, its uses, forms and functions, as well as its prospects in the national context.

Chapter 5 of this survey is grounded on a qualitative research of three generations of Russian users of English. The instrument of the empirical study includes a questionnaire, completed by one hundred and thirty respondents, in 2010.

The findings of the research are related to the changes in the language policy and English language instruction, implemented at different periods of contemporary Russian history. It is thus hypothesized that respondents comingfrom different age groups diverge in their language proficiency, as well as in their attitudes and experience in the use of the language. The same outcome is believed to be observed by respondents with greater experience in international communication. Moreover, the younger participants are assumed to reveal better language proficiency and broader perceptions of different aspects of the English language in terms of its uses, variation and teaching models.

Having undertaken this study, it is hoped that the sociolinguistic survey of a heterogeneous community of English users in Russia will be helpful in, first, understanding the role of English in a particular national context and, second, in designing new practices for English language teaching for Russian users of English.

It must also be noted that the spread of English in Russia is similar to other post-communist countries of the former Soviet bloc. As a relatively young member of the global community, Russia is not as affected by the processes of globalization and internationalization as many other countries. Besides, feeling themselves as a part of a rich cultural heritage, Russians will always demonstrate the national unity in what concerns the protection of their identity, language and culture, and, as a consequence, will put up greater resistance towards foreign invasion.

Finally, as a last remark to be made, this dissertation is not a complete study but rather a foreword, setting up theoretical and empirical implications for further research. It offers room for new research perspectives and a testing of recent theories especially for English language teaching. Further investigations are needed in theoretical research, applied linguistics, and other interdisciplinary research areas.

6

1. English in Russia: Historical Development and Current Status.

Nowadays, English in Russia manifests itself in various contexts such as education, business, and tourism, being its unprecedented spread most frequently attributed to the privileged position ensured to the speakers of English in social, professional, cultural, and individual spheres. This linguistic situation is common to many other countries where English is learnt as a foreign language, and is used as a means of access to the international community.

However, the spread of English in Russia is different from most other regions of the world. In fact, it is believed that the understanding of the current status of English in Russia would be impossible without a retrospective account discussing chiefly two aspects:

1. what range of factors has pre-conditioned the spread of English in the national settings, and

2. how the English language has been implemented in teaching practices throughout different periods of contemporary Russian history.

Bearing in mind a great variety of conditioning factors of the presence of English in Russia nowadays, to present a general overview of this language, from a diachronic and a synchronic perspective, and reflect on attitudes towards English and Russian, as well as on growing multilingual processes worldwide, this chapter is divided into three subchapters.

The first subchapter gives insights into the English-Russian relations from the Cold War to the New Russia epoch, outlining three major periods, each with its impact on the role, spread and uses of English, as well as on English teaching pedagogy in the national contexts.

The second subchapter brings to the fore the presence of English in modern Russia, manifesting more prominently in such contexts as tourism, employability and Internet

7

communication, in which exchanges between Russia and the international community are substantially higher than in other realms of everyday life.

Finally, the last subchapter points out that, despite the extensive use of English as a vehicle of communication with the international community, recently the Russian authorities have made considerable efforts to protect the national language. The incentives taken in this direction, nonetheless, do not prevent Russians from growing aware that nowadays English proficiency is one of the fundamental conditions for being efficient in international settings. Knowledge of other world languages, however, is perceived as a plus factor.

1.1. English-Russian relations: a general historical overview.

The historical development of Russian-English contacts, contributing to the changes in foreign-language instruction from the post-war period up to nowadays, and pre-conditioning the spread of English in the national settings, may be divided into three major periods which coincide with the key moments of contemporary Russian history:

1. The Cold War: 1947-1991. 2. Post-perestroika: 19921-1999.

3. The New Russia epoch: from 2000 onwards.

Such broad demarcation, however, allows further subdivisions, reflecting different degrees of intensity in Russian-English language and culture contacts, especially during the period of the Cold War between the Soviet Union (USSR) and the Western world.

1.1.1. The period of the Cold War.

The period of the Cold War (1947-1991), which lasted through most part of the second half of the last century, experienced a remarkable setback in relations between Russia and English-speaking countries. However, the tension between the Soviet Union and the West was interrupted by a phase of temporary revival of Russian-English relations during the period of the “thaw” (1953-1964) and the beginning of gradual enhancement in the perestroika time (1985-1991). These political aspects are closely linked to the way learning and teaching English in the USSR was implemented.

1 Although 1992 is taken as a beginning of the post-perestroika period, the USSR was formally dissolved on December 25, 1991.

8

The beginning of the Cold War: Deterioration of relations with the West (1947-1952).

In the mid 1940s, relations between the USSR and the Western countries became rather strained. The ideological struggle between the United States of America (USA) and their allies reached its peak in 1947 and marked the beginning of the Cold War, giving way to hostile and negative attitudes on either side of the Iron Curtain. As it is noted, “the Iron Curtain had been working two way – not letting stuff and information in and not letting anyone out” (English Russia, 2009). The Soviet government effectively isolated its citizens from any contact with English-speaking countries. Soviet readers could not have access to periodicals in English without special permission. Likewise abroad traveling to the hostile capitalistic countries such as the USA and England existed “only for the best of the best comrades” (English Russia, 2009), but not for the rest of 99.99% of the Soviet people.

The isolation from the West largely contributed to the fact that “foreign language learning was entirely a homegrown affair: made in the USSR” (McCaughey, 2005: 456). At that time, English became a formal school subject as most pupils understood that they might never come in contact with a native English speaker. To those enrolled in the Faculties of Foreign Languages, teaching was likely to become their only line of work.

The thaw: “Breaking the ice” in Russian-English relations (1953-Oct. 1964).2

The “thaw” is known as a temporary break in the icy tension between the USSR and the USA. An attempt to achieve peaceful coexistence and reduce hostility between the two superpowers was proved by opening the doors to international visitors from all over the world. This defrosting in the Soviet-Western relationship became possible for the first time during the 6th World Festival of Youth and Students, held in the Soviet Union on July 28, 1957.

The festival attending foreign members brought with them their way of life, and such foreign trends as jeans, trainers and rock-n-roll, so characteristic of occidental youth culture. By then the song “Rock around the clock” became a music hit.

Trying to overcome the isolation from the West, on May 27, 1961, the Council of Ministers of the USSR adopted the decree “On the Improvement of Foreign Languages Teaching”. The intention was to create 700 specialized language schools and elaborate new teaching material (Litovskaya, 2008). However, despite this beginning in the 1960s, all English textbooks studied at school and university levels were published under careful control

2 This period, also known as Khrushchev’s Thaw, coincides with the years of Nikita S. Khrushchev’s government as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 until Oct. 1964.

9

of the Ministry of Education which continued to impose the doctrines of the Soviet ideology through the teaching process.

“Stagnation”: Back to tensity in relations with the West (Oct. 1964-1984).3

From 1964 to 1984, the Soviet authoritarian policy was partially restored, bringing back tension in the relations with the West. The greater part of this period is known as “stagnation”, characterized by a relatively stable policy and impossibility for real change.

Little progress was achieved in the contacts with the occidental world. The tensity was aggravated by the arms race and the position assumed by the Soviet Union in the Vietnam War. The Soviet invasion in Afghanistan in 1979 became the main reason for the United States to boycotte the 1980 Summer Olympics, held in the USSR.

In view of such downtime, not much can be said about foreign language instruction which followed the same teaching methods, within the frame of existing ideology.

Perestroika reforms: Looking up to the West (1985-1991).

In 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev was elected General Secretary by the Politburo. When Gorbachev came to power, his primary goal was to revive the Soviet economy, after years of stagnation, introducing glasnost’ (“openness”), perestroyka (“restructuring”), demokratizatsiya (“democratization”), and uskorenie (“acceleration” of economic development). Perestroika reforms marked the end of the Cold War and the subsequent reconstruction of the Soviet political and economic system which opened the Soviet Union to the rest of the world.

The new wave of industrialization based upon information technology had left the Soviet Union desperate for technology and information sharing with the West. The economic reforms gave a new impetus to Russian-English relations and allowed conducting foreign trade and establishing joint ventures with foreign investors.4

3 The period of “stagnation” starts with the beginning of Leonid I. Brezhnev’s government as First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in Oct. 1964 and lasts until Mikhail S. Gorbachev’s election in 1985. 4 Symbolically, the first successful Western business to take advantage of perestroika reforms was McDonalds, which opened in Moscow, on January 31, 1990.

10

Nevertheless, while Gorbachev’s political initiatives were positive for freedom and democracy in the Soviet Union and were largely hailed in the West,5 his economic reforms gradually brought the country to collapse.

In consequence of perestroika reforms, towards the end of 1980s, a lot of English words penetrated into the Russian language. They were to name new realities that did not exist in the Soviet Union, as it is further detailed in chapter 3.

Meanwhile, the traditional teaching practices, which failed to suit English learners looking up to the West, started being replaced by methods, prioritizing the development of communication skills.

Teaching English: Made in the USSR.

During the Cold War period, the use of English in Russia was basically limited to educational domains, not coming outside the school or university classroom. Children were generally introduced to English, when entering the secondary school, at the age 10 or 11.

In the long of the Soviet history, foreign language teaching in the USSR was, as it has been already stated,6 “entirely a homegrown affair” (McCaughey, 2005: 456). Intended to define the values of the country’s leading ideology, it was developing by its own rules, in isolation from English-speaking communities. It sought to establish a correct perspective on the foreign way of life, and protect the Soviet learner from influence and temptations of consumer society. In other words, the main objective of English teaching in the USSR was the development of a “proper” Soviet citizen rather than the acquaintance with a foreign language and culture.

Propaganda of the Soviet way of life was especially common in textbooks for senior pupils, where Soviet reality was introduced into English texts by means of politicized clichés, words and phrases, such as communist society, Komsomol members, five-year-plan periods, ideals of Marxism-Leninism, proletarian unity, etc.

The great majority of teaching material was edited, for the most part, by Soviet authors who had never lived in English-speaking countries. Nash (1971), while characterizing materials used in class, points out the political image they helped to create:

5

Gorbachev’s reorientation of the Soviet policy contributed to the end of the Cold War, and led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union. For these efforts, he was awarded Otto Hahn Peace Medal in Gold, in 1989, and the Nobel Peace Prize, in 1990.

6

11

[By and large] teaching material identif[ied] the political friends and enemies of the Soviet Union, and creat[ed] a favourable image of its people, its way of life, its accomplishments, and its position of leadership in scientific and cultural affairs.

(Nash, 1971: 5)

For instance, in Starkov and Dixon (1984), the pupil’s book Ninth Form English and Tenth Form English, 20 out of 45 texts, and 49 out of 59 articles, to a greater or smaller extent, include propaganda of the Soviet way of life. Thus, while the West is described as torn by various political and social problems such as strikes, demonstrations, unemployment, expensive medical care and rising living costs, the Soviet Union boosts industrial and technological development, better living conditions, growth of industrial output, free medical care and increasing labor demand – all this is secured by “a government of the people for people”.

On the elementary school levels, active propaganda was substituted by the description of daily routine of people deprived of national identity. In this imaginary unpoliticized world, people get up, have breakfast, go to school or work, read or watch TV. Consequently, the United Kingdom (UK) was replaced by the USSR, London by Moscow, Trafalgar Square by the Red Square, and the London underground by the Moscow underground. This all meant that “our” way of life, “our” people, and “our” cities, etc. are not at all different from “theirs” and are, by no means, worse.

Despite the introduction of new methods of teaching English in the 1960s, described at great length in Ermakov (n.d.), the traditional Soviet methodology involved in the teaching process had very limited scope of objectives and, with some exceptions, could be defined as the Grammar Translation Method. It required competence mostly in terms of reading, writing, grammar, vocabulary, and translation skills.

In whole, the teaching practices were focused on memorization of grammar patterns and numerous rules, and their application to new examples. Eventually the learner got involved into doing exercises based on repetitions of one and the same constructions, with only some insignificant variations, mostly in terms of vocabulary, e.g. Say what you like to do in summer; Say what you learn to do in winter; Say what you want to do at school.

The stress was laid on translating sentences, and even whole texts, into the mother tongue. Not one lesson missed the task Read and Translate.

As a result of teaching practices, students had little motivation to go beyond grammar rules. They were not called upon to speak the language in any communicative situations, and

12

were constantly involved in role-playing of artificial dialogues, based on the repetition of the same grammatical patterns and constructions, such as:

A: What are you going to do after school? B: I’m going to read a book.

A: And what are you going to do? B: I’m going to watch TV, etc.

The traditional method shaped an “attitude to the language as a system of grammatical constructions filled up with diverse lexical content” (Litovskaya, 2008) – what in itself could not result in any communicative proficiency. As a result, the whole process was uninspiring, overwhelmingly tedious and boring. “In general, the neglect of the individual [and his needs and problems in teaching process] was a pivot of Soviet ideology” (Ter-Minasova, 2005: 448).

Probably the only authentic material which was available to the Soviet learner during and after the period of the “thaw” was represented by texts of British less often American writers. Hardly a textbook missed an excerpt from Three Men in a Boat by Jerome K. Jerome. Texts of W. Shakespeare, J. London, M. Twain, O’Henry, and E. Hemingway were also widespread. The Foreign Languages Publishing House produced not only books but also newspapers and periodicals available for readers inside the country – The Moscow News, New Times, Soviet Russia, Sports in the USSR, Soviet Literature, and Soviet Inventions, among others. For many people studying English, these texts and publications became the only source of the language itself.

For decades English in the Soviet Union was taught as a dead language like Latin or Ancient Greek, because “the world of its users did not exist [and] the goals and techniques of dead language studies were applied to living ones” (Ter-Minasova, 2005: 447). In this light, only a small handful of scholars, academicians, diplomats, and foreign language specialists knew English well; the rest of English learners suffered from the so-called “English dumbness” and could not adequately express themselves at the basic level, unless in writing, and only with the use of a dictionary, after 6 years of study at school, and 2-4 years at a higher institution.

Nash, already in 1971, stresses this lack of contact with English speaking countries during this period:

13

English teaching in the Soviet Union suffers from the same malaise as society in general – lack of contact with English-speaking countries. It is tribute of Soviet educators that they have accomplished so much in the absence of such contact.

(Nash, 1971: 12)

In 2005, Ter-Minasova, when referring to English teaching in the Soviet Union, underlies the absence of proper equipment, authentic English learning, and teaching materials:

For decades, under such circumstances, generations of teachers, who never set their eyes – or ears! – on a native speaker of a foreign language, taught generations of students without any proper equipment, without authentic English Language Learning and Teaching (ELLT) materials, developing chalkboard theories and poor-but-honest, necessity-is-the-mother-of-invention techniques, and they did it brilliantly.

(Ter-Minasova, 2005: 446)

Nonetheless, as Nash (1971: 1) notes “the strangest contradiction” of all was that “English [was] given top priority over all foreign languages by official government policy”. English was especially emphasized at school levels. Its knowledge was also mandatory for getting into university.

1.1.2. The post-perestroika period.

In 1991, the new glasnost and perestroika reforms brought the Soviet system to collapse. In fact, the dissolution of the Soviet Union into independent nations began as early as in 1985, providing an impetus for political and economic reforms, and cultivating warmer relations and trade with the West.

Despite the gradual enhancement of the Russian-English relations, the post-perestroika period was a contradictory time for the Russian history. The intension to transform Russia’s socialist command economy into free-market economy by implementing economic shock therapy7 led to disastrous effects and economic downturn, enormous political and social problems that affected Russia and the former republics of the USSR. In foreign policy Russia

7 The first president of Russia, Boris Yeltsin turned to the advice of Western economists, and Western institutions such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the U.S. Treasury Department, which had developed a standard policy recipe for transition economies, in the late 1980s. This policy recipe came to be known as the “Washington Consensus” or “shock therapy”, a combination of measures intended to liberalize prices and stabilize the state’s budget.

14

was searching for a new identity, being torn between the East and the West, as close relations with the West were still considered a danger for its national security.

After the fall of the Iron Curtain, the linguistic situation in Russia drastically changed, mainly due to the growth of international contacts and opportunities for free travel. As such, Russia joined the global community where English served as the major tool uniting people from different national and cultural backgrounds. Strains to overcome the years of linguistic isolation caused what Proshina and Ettkin (2005: 443) define as “an English language boom in Russia”.

A great number of English words started to sporadically penetrate into the Russian language. The domains of the use of English rapidly expanded into media, advertising and professional spheres. However, English was seen not only as a tool of access to any culture in the global village, it also became a way of manifesting one’s own culture and identity through the language. In other words, “the English language serve[d] as a means for spreading Russian culture throughout the world” (Proshina and Ettkin, 2005: 443).

In a short period of time after the perestroika, a growing perception that English proficiency would provide access to better job opportunities and contacts with English-speaking countries, through information and technology sharing, created a considerable market of English teaching, including teaching materials, language courses, and private tutoring.8

In the 1990s, English learning and contacts with British and American cultures were fostered by the emergence of non-governmental organizations, foreign aid agencies, and cultural associations such as the British Council, the English Language Office (ELO), and the Soros Open Society, among many others (Ustinova, 2005b: 245-7). In 1992, the British Council opened in Moscow its first information centre. The English Language Office, supported by the US Department of State, was founded in Moscow, in 1993. The Soros Fund has been active in Russia since 1988. After the perestroika, its grants helped thousands of scholars, professors, teachers, and students to survive.

8 In the 90s, a Russian-English audio-course for express method by Ilona Davydova was considered a real breakthrough in teaching English. By that time, the name of the course was known virtually to everyone, due to the massive TV advertising campaign. After listening to the course, the learner was supposed to be able to communicate in Basic English in such circumstances as work, doctor’s office, shop, among friends, etc. All the learner had to do was to repeat a lesson 1-2 times a day, for one week. After repeating semantic clusters of words, phrases and suggestions several times, it was believed he would remember them at the level of automaticity. This method was considered to make English learning easy and fast.

15

However, despite a considerable breakthrough in Russian-English relations, the 1990s were the critical time for English language teaching, characterized by the absence of control from the state and rapidly declining educational standards.

The changes were enormous, as the period of the Soviet Union in which learners were confronted with limited teaching materials available was followed by the time when the increase in number of language teaching sources, coming from different parts of the English-speaking world, was nothing but “frustrating” (McCaughey, 2005: 457).

Under such circumstances the majority of English language teachers preferred to apply the same teaching methods and materials which had been adopted in the time of the Soviet Union. Thus, their students continued to learn English from such Soviet products for English learning as N.A. Bonk, V.D. Arakin, A.P. Starkov, K.V. Zhuravchenko, and V.S. Shakh-Nazarova.9 Other teachers, on their part, started to enthusiastically experiment with new teaching sources and methods not always comprehensible to Russian learners.

Meanwhile, Russians increasingly began identifying English language proficiency as an important step to secure footholds in international trade, technology and information sharing. This led to the demand for English language instruction and teaching materials. Recognizing its advantages for education and career opportunities, more students started to choose English as their first foreign language.

According to the findings of the Russia-wide poll carried out by the Public Opinion Foundation on November 6, 1999, designated to find out whether Russians spoke English, 70% of respondents did not speak English at all, 23% said their language skills were poor, 6% characterized their skills as good, and just 1% of those surveyed said their English was fluent. Near half of those surveyed in Moscow and Saint Petersburg spoke some English (16% defined their English as well or fluent; 30% as poor). It was also observed that, according to the poll results, the percentage of English speakers was increasing, from the older generation to the younger generation. In fact, only every eleventh among respondents over 60, spoke some English, while 50% of those under 35 had, at least, some knowledge of English.

9 These are famous Russian linguists and educators, developers of teaching materials, well-known to every learner in the USSR and in post-Soviet Russia. The following textbooks have been re-edited more than once and are still used in teaching practices in Russia: N.A. Bonk, eds., Textbook of the English Language, Step by Step; K.V. Zhuravchenko and V.S. Shakh-Nazarova, English for You; V.D. Arakin Practical Course of English, for college and university students; A.P. Starkov, eds., English textbooks for comprehensive secondary school pupils.

16

1.1.3. The New Russia epoch.

In 2000, after a surprise announcement of Yeltsin’s resignation, the power in the country passed to the young Prime Minister Vladimir Putin. His government marked the beginning of the New Russia epoch, leading to qualitative changes in the Russian policy and the recognition of the country on the global arena.

Since Russia has bounced back from the critical post-perestroika period, the demand for English is still increasing. In the second decade of the 21st century, English is spoken virtually in every part of the country, being primarily claimed as a means of international communications, and, thus, helping to build links across national and cultural borders all over the world. The excessive influx of foreign words Russia faced in the 90s has also stabilized and subsided and is no longer seen as a threat to Russian national identity.

As to the number of English speakers, no reliable figures can be obtained, since the level of proficiency greatly varies from native fluency to limited command of the English language. According to the survey carried out by Career magazine, 3.2% of all Russian population speak English fluently, 4.8% of English speakers “can read and make themselves understood” in English, and 28.9% “read in English and translate from English with a dictionary” (Galkin, 2006). The State Statistics Service estimates even a smaller percentage of fluent English speakers – only 1% of Russian population (Eremeeva, 2008).10

1.2. Today’s English presence in Russia.

As previously pointed out, the presence of English in Russia started to be particularly felt with the perestroika reforms, introduced in 1985. However, it was only after the fall of the Iron Curtain that it became even more prominent, mainly due to the growth of free travel, economic contacts with other countries, and the emergence of the Internet.

The thirst for learning English in Russia continues unquenched as Russians travel more, use English on the world-wide web, seek international business partners or simply wish to increase their career opportunities. Kalashnikova (2009) stresses these aspects, relating them to prosperous or difficult times:

10 To compare with, “38% of European Union citizens state that they have sufficient skills in English to have a conversation” (Special Eurobarometer, 2006).

17

When the country is prospering, people study languages in order to travel, as such knowledge gives them the opportunity to get the most enjoyment out of fulfilling this dream (…) In difficult times, they continue their education with the aim of moving abroad or looking for a job at a Western company.

(Kalashnikova, 2009)

Likewise, the motivation to study English is closely associated with new information technology such as the Internet, computer games, and software. More and more people need English to use different services on the web, share information and come in contact with people internationally.

As nowadays Russians come in touch with English in varied national and international settings, today’s Russia may be defined as an international country with several venues of English use, particularly in such contexts as tourism, employability, and Internet communication.

1.2.1. Tourism.

Tourism in Russia has seen rapid growth since the late Soviet times. Short after Russia opened its borders to its citizens and to the rest of the world, and the turbulent time after the post-perestroika period had been finally overcome, millions of Russians rushed in different directions to explore what had been under a ban not long ago.

“In Soviet times there was the myth of ‘abroad,’ wonderful countries that everyone dreamed of going to,” said Stanislav Chernyshov, director of Extra Class Language Center. “Ever since then, intelligent, educated Russians have strived to achieve that aim.”

(Kalashnikova, 2009)

According to the Russia Federal Agency for Tourism statistics, more than 14.5 million Russians went abroad as tourists in 2011 (Russia Federal Agency for Tourism, 2012b). This is six times more than the number of foreign tourists (Russia Federal Agency for Tourism, 2012a) who visited Russia during the same period.

Outbound tourism.

In fact, since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, travel abroad has become very popular among Russians. Quoting again the same source mentioned above, the Russia Federal Agency for Tourism (2012b), the most popular destinations in 2011 (see table 1.1) remain

18

such countries as Turkey and Egypt for their relative cheapness, good quality service and the absence of language barrier. Finland and China are frequently chosen for its geographical proximity.

By the number of visits, the UK occupies the 17th place, and the US is on the 20th position with the less number of visits.

Although the majority of Russians recognize the advantages of speaking English for international traveling, the language barrier still remains one of the major factors that prevent Russians from exploring a lot of destinations individually. Group tours with Russian-speaking guides are still preferred to traveling independently from tour operators.

Inbound tourism.

In 2010, Russia was attended by around 2.3 million foreign tourists (Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) countries not included) with the majority of visitors coming from

11 Million people. Country Mln11 1. Turkey 2,7 2. China 1,5 3. Egypt 1,5 4. Finland 0,9 5. Thailand 0,8 6. Germany 0,7 7. Spain 0,6 8. Greece 0,6 9. Italy 0,6 10. UAE 0,4 17. UK 0,2 20. USA 0,1 Table 1.1.

Top holiday destinations according to the Russia Federal Agency for Tourism,