UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA

FACULDADE DE BELAS-ARTES

SUBSTITUTE LOCATION

Semiotics and Perception of Substitute Location

In Fiction Film - A Road Movie

Thomas Behrens

Orientadora: Profª. Doutora Maria João Pestana Noronha Gamito

Tese especialmente elaborada para obtenção do grau de

Doutor em Belas-Artes, Especialidade de Audiovisuais

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE BELAS-ARTES

SUBSTITUTE LOCATION

Semiotics and Perception of Substitute Location In Fiction Film - A Road Movie

Autor: Thomas Behrens

Orientadora: Profª. Doutora Maria João Pestana Noronha Gamito Tese especialmente elaborada para obtenção do grau de Doutor em Belas-Artes,

Especialidade de Audiovisuais Júri:

Presidente: Doutor Fernando António Baptista Pereira, Professor Associado e Presidente do Conselho Científico da Faculdade de Belas-Artes da Universidade de Lisboa

Vogais:

- Doutora Ana Margarida Duarte Brito Alves, Professora Auxiliar da Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade Nova de Lisboa

- Doutor Stephan Ferdinand Jurgens, Investigador de Pós-Doutoramento da Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da Universidade Nova de Lisboa

- Doutor Pedro Miguel Alves Felício Seco da Costa, Professor Auxiliar da Escola de Ciências Sociais e Humanas do ISCTE - Instituto Universitário de Lisboa

- Doutora Sílvia Lami Tavares Chicó, Professora Catedrática Aposentada da Faculdade de Belas-Artes da Universidade de Lisboa

- Doutora Maria João Pestana Noronha Gamito, Professora Catedrática da Faculdade de Belas-Artes da Universidade de Lisboa, orientadora

O presente trabalho foi realizado com o apoio financeiro da

RESUMO

Resultando de um Projecto de Pesquisa Artística, a minha tese é composta por uma parte teórica, com o título “Semiótica e perceção do Exterior Substituto (Substitute Location) no cinema de ficção”, e por um trabalho prático, um Road Movie. O Road Movie irá conduzir-nos através de um sistema de tópicos coordenados (alienação, assimilação, interpelação ideológica, imediatidade, etc.) que o trabalho teórico aborda sob um ângulo diferente.

Analisei uma série de filmes de ficção e obras de arte, focando-me na questão de como é que os lugares e locais são percecionados pelo sistema visual humano, que opera como um interface ou mesmo como um centro de tradução entre ver, percecionar, mapear e ser. A perceção visual é ao mesmo tempo a fonte que ancora a informação semiótica compreendida como representativa de um local real e fixo, e o ponto de projeção para mapear o mundo em esquemas de realidade virtual. Qualquer cineasta ou fotógrafo tem de encontrar a sua própria posição numa escala que vai desde a ‘projeção subjetiva total’ até à ‘documentação objetiva total’. Assim, a semiótica do espaço narrativo fílmico/fotográfico não é apenas uma categoria geográfica, geométrica, ou cinematográfica, mas é sempre também uma categoria moral. Isto é expresso no duplo sentido do termo ponto de vista, que designa simultaneamente uma dimensão topológica e uma dimensão ética.

Como objeto da minha investigação teórica escolhi uma prática comum em produções cinematográficas: o fenómeno chamado ‘Substitute Location’ (Exterior Substituto) servirá como ponto de partida para a minha viagem especulativa. O filme do James Bond Die another Day (Lee Tamahori, 2002), é um dos muitos filmes mainstream que ilustram esta prática. O enredo do filme passa-se em parte em Havana, em Cuba, e algumas das cenas mostram o ator Pierce Brosnan no papel do agente 007 passeando-se no famoso Malecón habanero, mas na realidade estas cenas foram filmadas em Cádiz, Espanha. Assim, Cádiz serve como uma ‘Substitute Location’ para Havana. Uma localização ou exterior é o local onde é filmado (parcial ou inteiramente) um filme ou série de TV, para além das cenas que são filmadas em estúdio ou cenários extras produzidos para o filme. Desde Roberto Rossellini e o Neorrealismo italiano, muitos realizadores preferem filmar nos locais onde supostamente se desenrola a ação por entenderem aproximar-se mais da realidade filmando num sítio real ao invés de num estúdio artificial fingindo ser um sítio real. Os realistas — e entre eles muitos documentaristas — assumem, na tradição filosófica de Aristóteles, que as estruturas básicas da realidade são confiáveis, podem em princípio ser refletidas pela

experiência, e podem ser adequadamente representadas através de formas linguísticas ou simbólicas (iconográficas).

O fenómeno particular da ‘Substitute Location’ aborda de uma forma concreta o como a desincorporação e a semiótica ideológica do «faz de conta» trabalham lado a lado. Substitute Location permite-nos presumir simultaneamente que alguém na equipa cinematográfica (o produtor / realizador / repéreur) acreditou que o local A “parece mais historicamente apropriado que” ou ‘será percecionado como’ o local B enquanto explora momentos de convergência e de conflito entre o significante e o significado. Uma Substitute Location torna-se um potencial, ainda que involuntário, meio para uma dialética do ver, onde os ‘pontos cegos’ das nossas projeções se tornam parte integral da nossa perceção individual e coletiva das identidades e da sua interpelação ideológica.

A minha abordagem artística à realidade é influenciada pela disciplina da Psicogeografia. Não existe uma definição consensual para Psicogeografia mas é inegável que esta disciplina foi profundamente influenciada, se não mesmo criada, por Guy Debord (1931 – 1994) e pela Internacional Situacionista (IS). O corpo de trabalho criado pela IS pode parecer trivial mas eu sou da opinião que os mecanismos e estratégias da IS são ferramentas úteis para compreender e combater as atuais circunstâncias da nossa sociedade, que fez do consumo passivo e do seu pré-requisito — o sucesso financeiro de cada um — a medida de todas as coisas. A psicogeografia tenta potenciar formas relevantes de olhar para ambientes passados, presentes e futuros; ambientes que hoje são em grande parte construídos pelos meios de comunicação de massa e os designados social-media. De alguma forma, a Psicogeografia tenta recuperar uma forma de viagem que foi outrora sinónimo de aventura. Hoje, só é possível constatar um declínio da viagem autêntica, que deixou de ser heroica ou individualizante. Os psicogeógrafos nutrem um desencanto pela rapidez com que os viajantes modernos se podem deslocar pelo planeta, sem riscos e sem a possibilidade de se confrontarem com o desconhecido. Antes da queda das barreiras globais na semiosfera, a viagem não equivalia a uma mudança quase instantânea de lugar, mas sim a um acontecimento transformador, carregado de importância histórica e psicológica.

Uma vez que a questão da identidade está intimamente relacionada com os lugares e os seus significados, a minha investigação foca-se nas modificações que o decorrente processo de mediatização acarreta e, em particular, o papel do ecrã neste processo. Assumo que a presença ubíqua de ecrãs traz uma sensação coletiva de dissociação, já que a identidade é cada vez mais construída fora de um corpo que a ancora. Com isto em mente,

proponho ampliar o conceito de Substitute Location e aplicá-lo a todas as nossas projeções. A abordagem interfacial para o mundo da vida gera um universo além, como nas Arcadas de Walter Benjamin, um espaço-sonho ersatz e frustrado (substitute location), que serve predominantemente para agitar desejos e impulsos consumistas. Uma vez que os nossos desejos são projetados para este espaço de mediático de sonho, os nossos corpos são deixados para trás. Ocasionalmente, aparece uma brecha, e podemos olhar para o mundo fora do sonho, que parece um gigantesco aterro para resíduos e detritos. Defino a minha tarefa como investigador no campo da Psicogeografia como um esforço para encontrar e construir imagens dialéticas a partir daquele repositório histórico. No entanto, estou igualmente interessado em descobrir como é que a medida de uma vida humana pode resistir a esta sensação coletiva de dissociação. Assim, o meu trabalho prático, o Road Movie tomou a forma de uma biografia. As biografias olham para o passado, que é tópico. Se as pessoas não tivessem laços a um lugar, não haveria identificação, não haveria cultura. A minha pesquisa analisa as modificações e transformações dos lugares quando estes são transpostos para um espaço mediado, quando passam de ‘sítios’ a ‘vistas’, à medida que são incorporados na narrativa fílmica. A memória de um lugar ou corpo físicos e reais, e o seu uso como significantes desencarnados ajuda a criar a forma de uma grande narrativa, que constitui uma paisagem estruturada de pensamento. A narrativa cinematográfica é solipsista. A subjetividade torna-se distanciada e é aplicada à sociedade como um todo, que reúne milhares de narrativas. Não só coisas e memórias mas também signos são localizados. Concentrando-se numa descrição espacial, a narrativa pode ser organizada em relação à História, bem como à sua interpelação ideológica com a identidade individual.

À primeira vista, existe apenas uma rua e o seu nome: Rua Ricardo Chibanga. A toponímia é uma parte importante da Geografia histórica e portanto da Psicogeografia: os topónimos são relativamente estáveis através dos tempos, documentando a história de uma povoação. Os movimentos migratórios dos indivíduos refletem-se na origem dos nomes, os antropónimos, que são particularmente instrutivos. Nomes de áreas residenciais como Lourenço Marques (uma cidade), o monte Evereste (uma montanha) ou a Rodésia (um país) são topónimos que, stricto sensu, referem a exploradores e colonizadores. Isto significa que estes locais são ideologicamente interpelados pelos seus próprios nomes. O que me surpreendeu quando me deparei com esta placa representando o nome da rua, foram os significantes ausentes: a placa informa-nos que Ricardo Chibanga é um toureiro, mas não indica que ele é de origem africana. No entanto, o seu nome torna este facto conspícuo pela sua ausência e não deixa de influenciar o sentido de um significante que é

utilizado. Outra forma de ausência carrega em si a etiqueta daquilo que «é evidente», ou seja, e neste caso, que a lide do touro é uma atividade geralmente reservada a uma classe aristocrática Ibérica predominantemente branca. Subitamente, a divisibilidade deste local emerge do seu próprio nome, da linguagem que o inscreve, tal como um ‘point de capture’ fixa um significante flutuante. Como esta linguagem tem de comunicar algo (algo mais do que ela própria), a placa não nomeia exatamente o local. Refere-se a uma pessoa, um toureiro africano, que veio viver para Portugal. Quando ele chegou, Portugal era uma potência colonial. A ideologia oficial em Portugal declarava que todos os territórios africanos eram parte integral do território Português e que não existiam colónias — os nativos desses territórios eram efetivamente cidadãos de Portugal. A estrada que encontrei transforma-se agora num local onde, da cisão entre a visão topográfica da África colonial e o nome real da Rua Ricardo Chibanga, emerge uma tensão que assombra este espaço urbano com um sentido adicional que é necessário abordar: o nome de uma pessoa viva tornou-se o nome de uma estrada. Este ato de assimilação é na verdade o encerramento de um debate com a história. O Road Movie, que no meu caso é um filme sobre uma estrada, tenta reabrir este ‘caso fechado’.

Palavras-Chave:

ABSTRACT

My thesis, the result of an Artistic Research Project, is composed of a theoretical part, which is titled “Semiotics and Perception of Substitute Location in Fiction Film” and a practical work, a Road Movie. The Road Movie will take us through a coordinate system of topics (alienation, assimilation, ideological interpellation, immediacy, etc.) that the theoretical work approaches from a different angle:

For the theoretical part, I have analyzed a number of fiction films and artworks with a special focus on the question how places and locations are perceived by the human visual system, which operates as an interface or even as a translation centre between seeing, perceiving, mapping and being. Visual perception is at the same time the source that anchors semiotic information perceived as representative for a real, physical location and the projection point for mapping the world in schemes of virtual environments. Any filmmaker or photographer has to find his own position on a scale that goes from 'total subjective projection' to 'total objective documentation'. Hence, the semiotics of a filmic/photographic narrative space is not only a geographical, geometrical, or a cinematographic category, but always also a moral category. This is expressed in the double meaning of the term point of view, which designates simultaneously a topological and an ethical dimension.

As the object of my theoretical research I have chosen a practice that is common in feature film production. It should serve as a point of departure for my speculative journey, and this phenomenon is called 'Substitute Location'. The James Bond movie Die another Day (Lee Tamahori, 2002) is one of many mainstream movies, which illustrate this practice. The film has a plot that takes place in part in Havana, Cuba and some of the scenes show the actor Pierce Brosnan as agent 007 walking along the famous Malecón in Havana, but these scenes were actually shot in Cádiz, Spain, so Cádiz serves as a ‘Substitute Location’ for Havana.

A location is a place where a film or a TV series is wholly or partially produced, in addition to the scenes that are shot in a film studio or on extra sets produced for the film. Since Roberto Rossellini and Italian neo-realism, many filmmakers prefer to shoot in real locations because they believe that they will catch more realism if they are in a real place, and not in an artificial studio set pretending to be a real place. The realists - among them many documentary filmmakers - assume, in the philosophical tradition of Aristotle, that the basic structures of reality are reliable, can be reflected by experience, and, in principle, can

be represented adequately in linguistic or other symbolic (iconographic) form.

The particular phenomenon of ‘Substitute Location’ addresses in a concrete way, how disembodiment and the ideological semiotics of 'make-believe' work hand in hand. Substitute Location allow us simultaneously to assume that somebody in the film team (the responsible producer/ director/ location scout) believed that location A 'looks more historically appropriate than' or 'will be perceived as' location B while exploring moments of convergence and conflict between the signifier and the signified. A Substitute Location then becomes a potential, yet involuntary, environment for a dialectics of seeing, where the blind spots of our projections become an integral part of our individual and collective perception of identities and their ideological interpellation.

My artistic approach to reality is influenced by the discipline of Psychogeography. There is no universal definition of what Psychogeography means, however, this discipline was undoubtedly influenced, if not created by Guy Debord and the Situationist International (SI). The body of work which has been created by the SI may seem trivial today but I think that the current state of our society, which has raised passive consumption and its prerequisite, individual financial success, to the measure of all things, can not only be grasped, but it also can be effectively countered with the methods and strategies of the SI. Psychogeography endeavors to develop relevant insights into past, contemporary and future environments, and today, these environments are constructed to a significant degree by mass and social media. In some respect, Psychogeography seeks to reclaim a form of travel that was once synonymous with adventure. Today, one can only state a demise of real travel that is no longer individualizing or heroic. Psychogeographers are disenchanted at the sense of inertia, with which modern travelers seem to move around the globe, taking no risks and facing no unknowns. Prior to the breakdown of global barriers in the semiosphere, travel was not an almost instant change of places, but a transforming event filled with historical and psychological significance.

Since the question of identity is closely related to places and their meaning, my research focused on the changes that the ongoing process of mediatization brings about and in particular, the role of the screen device in that process. I assume that the ubiquitous presence of screens brings forth a collective sense of dissociation, as identity is increasingly constructed outside of an anchoring body. With this in mind, I propose to broaden the concept of Substitute Location and apply it to all our projections. The interfacial approach to the lifeworld generates a universe beyond, that is, like Walter Benjamin's Arcades, an abortive ersatz dream-space (substitute location), which serves predominantly to stir desires

for consumerist impulses. Once our desires are projected into this dream media space, our bodies are left behind. Occasionally, an opening appears, and we can look back onto the world outside of the dream, which looks like a gigantic landfill for waste and debris. I define my task as a researcher in the field of Psychogeography as to find and construct dialectical images from that historical depository.

However, I am equally interested in finding out, how the measure of a human lifetime can resist that collective sense of dissociation. Therefore, my practical work, the

Road Movie took on the form of a biography. Biographies look back on a past, which is

topical. If people had no ties to a place, there would be no identity, no culture. My research analyzes the modifications and transformations of places into mediated space, from 'site' to 'sight', as it is constituted in the film narrative. The memory of a real, physical body or place, and their uses as disembodied signifiers helps creating the shape of a grand narrative, which constitutes a structured landscape of thinking. The film narrative is solipsistic. Subjectivity becomes distanced and is applied to society as a whole, which collects thousands of narratives. Not only things and memories but also signs are located. By focusing on a spatial description, the narrative can be organized in relation towards History as well as towards its ideological interpellation with individual identity.

At a first glance, there is only a road and its name: Rua Ricardo Chibanga. Toponymy is an important part of historical geography and henceforth of Psychogeography: toponyms are often very stable in time, and they document the history of a settlement. Migratory movements of individuals are reflected in the origin of names, the anthroponyms, which are particularly instructive. Residential site names like Lourenço Marques (city), Mount Everest (mountain) or Rhodesia (country) represent the reference of general toponyms to the names of explorers and colonizers in the strict sense, which means, those places are ideologically interpellated by their very names. What struck me when I came across this road sign are the absent signifiers: the sign says that Ricardo Chibanga is a bullfighter, but it does not say that he is of African origin. However, his name makes this fact conspicuous by its absence and nevertheless influences the meaning of a signifier actually used. Another form of absence has the specific label of 'that which goes without saying', in this case, the fact that usually bullfighting is an activity reserved for a predominantly white, Iberian aristocratic class.

Suddenly, the divisibility of this place emerges from the name, from the language that came to inscribe this place, just as a ‘point de capture’ keeps a floating signifier in place. As such a language must communicate something (something other than itself) the

road sign does not exactly name the just the place, but it creates a whole system of values. The street name refers to a person, an African bullfighter, who came to live in Portugal. Portugal had been a colonial power at the time when he came. The official ideology in Portugal stated that all territories in Africa were actually an integral part of Portugal and there was no such thing as a colony - the natives of these territories were actually citizens of Portugal. The road that I encountered now turns into a place where a tension emerges with the split between the topographic vision of colonial Africa and the proper name Rua Ricardo Chibanga haunts this urban space with an additional meaning that needed to be addressed: the name of a living person has become the name of a road. This act of assimilation is actually a historical 'closure'. The Road Movie, which is in my case a film about a road, aims at reopening this 'closed case'.

Key Words:

Acknowledgements

Although my gratitude cannot be expressed through a few sentences I would like to sincerely thank my supervisor Profª Drª Maria João Gamito for allowing me to learn and grow throughout my time at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Lisbon. Thank you for encouraging me to research and write this thesis my way and for guiding me through the mishaps and wrong turns. I hope that one day I will be able to reciprocate all the time you spent talking me through the original idea, working out the conceptual framework, and your constant support.

I am grateful to the FCT Portugal for making my work possible and for honoring the relevance of artistic research.

Finally, a great thanks to my wife Maia, my daughters Isabel and Evelyn, my family and friends and all those who listened to me and helped me work through the hardships. Thank you all for your patience, unceasing support, and constant encouragement. A special dedication goes to Lila Lacerda and to Uli Weber.

O presente trabalho foi realizado com o apoio financeiro da (this work was accomplished with the financial aid of)

Contents Page Resumo (PT) ii Abstract (EN) vi Acknowledgements x Table of content xi List of figures xv

Preliminary remark xix

Introduction 1

PART I: THE SITE AND ITS SYMBOLIC EFFICIENCY Chapter One: Place as Location

1.1. Germany Year Zero (Roberto Rossellini, 1946) 18

1.2. The place in the lifeworld and its double 22

1.3. Change of location: from nomads to tourists 24

Chapter Two: Places and Identity

2.1. Zelig (Woody Allen, 1983) 26

2.2. Subjective concepts of place 28

2.3. Social Identity 29

2.4. Influence of local culture on Identity 32

2.5. Bio-graphy and Geo-graphy 36

Chapter Three: Alienation

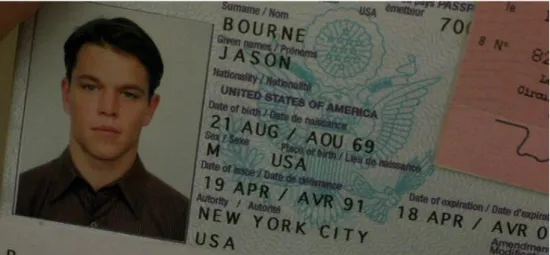

3.1. The Bourne Identity (Doug Liman, 2002) 37

3.2. Strangeness means not being at home 43

Chapter Four: Places as pictorial memory

4.1. Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1982) 46

4.2. Images as memory 48

4.3. Photography as an instrument of mimesis 50

Chapter Five: Structures provide “blank spaces”, where objects can be allocated

5.1. Blow-Up (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1967) 54

5.2. Semiosis: Emergence of meaning 57

5.3. The demise of symbolic efficiency 60

Summary Part I 63

PART II: MEDIATED SPACES AS A SUBSTITUTE FOR REAL-WORLD PLACES Chapter Six: Drawing lines - Locations and their moral implications

6.1. Dogville (Lars von Trier, 2003) 64

6.2. Enclosure 69

6.3. Mediatization is enclosure 72

6.4. Common ground 73

Chapter Seven: Media Space

7.1. Father Duffy. Times Square, New York City (Lee Friedlander, 1974) 76

7.2. Mass media and Social media 79

7.3. The medium provides the substance that ideas lack 81

Chapter Eight: The screen-based medium

8.1. Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983) 83

8.2. Ro.Go.Pa.G. , segment "Illibatezza – Chastity” (Roberto Rossellini, 1963) 85

8.3. The screen disembodies the place 88

8.4. The deceptive nature of screens 93

Chapter Nine: Transparency as a central discourse in a mediated environment

9.1. Open my Glade (flatten) (Piplotti Rist, 2000) 94 9.2. Transparency encapsulates a visual and moral concept 96 9.3. Consumption and production are part of the same process 98

9.4. Interference of the Real 101

Chapter Ten: Mediated spaces and the emergence of new categories of perception

10.1. Filme Socialisme (Jean-Luc Godard, 2010) 104

10.3. The screen as the central device in a consumerist society 109

10.4. Sites become sights - place as pure sign 112

Summary Part II 115

PART III : THE INSIDE OF MEDIA SPACE AND ‘ACTING OUT’ Chapter Eleven: Inside the hybrid media space

11.1. Teletubbies (BBC Children’s series, aired 1997-2001) 116

11.2. The view from the inside of a map 122

11.3. The map as an instrument of political power 124

Chapter Twelve: Simulacra

12.1. The Truman Show (Peter Weir, 1998) 128

12.2. Extra-diegetic elements 130

12.3. The instrumentalization of the gaze 132

Chapter Thirteen: The dominant symbolic order - the law

13.1. The Coral Reef (Mike Nelson, 2000) 135

13.2. The hidden supplement of the law and the taboo 142 13.3. Coming back from media space - a nightmare 145

Summary Part III 148

PART IV: THE OBJECT – A ROAD MOVIE

Chapter Fourteen: Constructing the Dialectical Image

14.1. Project: a road with the name - Rua Ricardo Chibanga 149 14.2. Process: Psychogeography - walking and contemplating 152 14.3.Process: analytical truth procedure or creative process? 158

14.4. Process: Why look at Bullfighting? 161

14.6. Product: the stranger is the extra-diegetic element 166

Conclusion 167

Attachments

List of Figures Page

Figure 1: Havana, Cuba 4

El Malecón. (2012, April 9).

Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

https://almejeiras.wordpress.com/2012/04/10/el-malecon/

Figure 2: Cádiz, Spain 5

Tags de Pueblos Blancos. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://www.urbecadiz.com/tag/pueblos-blancos/

Figure 3: Film still from Die another day (Lee Tamahori, 2002) 7 James Bond Locations. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

http://jamesbondlocations.blogspot.pt/2014_09_01_archive.html

Figure 4: Cádiz with the label ‘Havana’ 8

James Bond Locations. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://jamesbondlocations.blogspot.pt/2014_09_01_archive.html

Figure 5: The signifier as a symbol of an absence 15 Othello's Two Deaths. (2012, March 24). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

https://septemberschilds3.wordpress.com/2012/03/24/othellos-two-deaths/

Figure 6: Film still from Germany Year Zero (Roberto Rossellini, 1946) 18 Looking at the Landscape of Childhood in Ivan's Childhood

and Germany Year Zero. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from http://filmint.nu/?p=8916

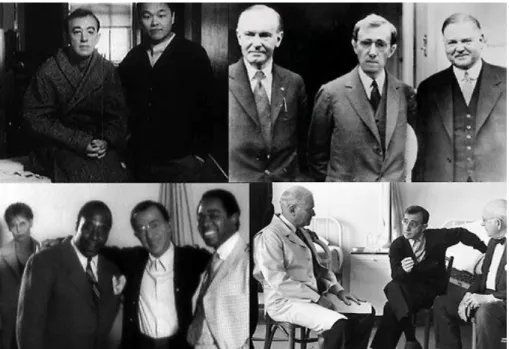

Figure 7: Compilation of four Film stills from Zelig (Woody Allen, 1983) 26 Bill O'Reilly: The Anti-Zelig with a very big mouth. (2015, February 26).

Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

https://richardbrenneman.wordpress.com/2015/02/26/41377/

Figure 8: Film still from The Bourne Identity (Doug Liman, 2002) 38 The Bourne Identity - Jason Bourne. (n.d.).

Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

http://wolfleben.deviantart.com/art/The-Bourne-Identity-Jason-Bourne-544062744

Figure 9: The parents of Madeleine ‘Maddie’ McCann, presenting an image, 40 generated with age progression software, of how her vanished daughter

could look like today.

Heather Saul: “Madeleine McCann:

Scotland Yard to release e-fit picture of possible suspect'” (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/madeleine-mccann-scotland-yard-to-release-e-fit-picture-of-possible-suspect-8868280.html

Figure 10: Fire Chief (Richard Roth, 1988) 42

Ridley Howard. Under the Influence: Interview with Richard Roth. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

Figure 11: Film still from Blade Runner (Ridley Scott, 1983) 46 Jordan Raup: ‘Blade Runner’ Writer Hampton Fancher

Returns For Ridley Scott’s Sequel; Will Feature Female Protagonist. (2012, May 17). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

http://thefilmstage.com/news/blade-runner-writer-hampton-fancher-returns-for-ridley-scotts-sequel-will-feature-female-protagonist/

Figure 12: Decorative Faux Wood Beams 48

Specializing in Decorative Faux Wood Beams | Superior Building Supplies. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

http://www.superiorbuildingsupplies.com/

Figure 13: Film still from Blow-Up (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966) 54 Lucie Horton: Blow Up Film Review | Smiths Magazine. (n.d.).

Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

http://www.smithsmagazine.co.uk/2014/06/10/blow-up-film-review/

Figure 14: Film still from Dogville (Lars von Trier, 2003) 64 DogVille de Lars Von Trier - Se ha escrito un Blog. (2007, August 20).

Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

http://www.davidgarcia.es/dogville-de-lars-von-trier/

Figure 15: The Location of Lines. Lines from the Midpoints of Lines. 66 (Sol Lewitt, 1975)

Sol Lewitt The Location of Lines. Lines from the Midpoints of Lines. (n.d.). Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

http://www.printed-editions.com/contemporary-art/sol-lewitt/sol-lewitt-the-location-of-lines-lines-from-the-midpoints-of-lines-11030

Figure 16: Father Duffy. Times Square, NYC (Lee Friedlander, 1974) 76 Friedlander. (n.d.).

Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

http://www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/113?locale=en

Figure 17: Film still from Videodrome (David Cronenberg, 1983) 83 Noel Murray, Keith Phipps, Nathan Rabin, Scott Tobias:

The sex, violence, and new flesh of Videodrome. (n.d.). Retrieved November 17, 2015, from

https://thedissolve.com/features/movie-of-the-week/559-the-sex-violence-and-new-flesh-of-videodrome/

Figure 18: Film still from the segment "Illibatezza-Chastity" of the film 85 RoGoPaG (Roberto Rossellini, 1962)

Peter Fuller. Pete's Peek | RoGoPaG - 1960s social satire from four of Europe's finest film-makers. (n.d.).

Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

http://www.whatsontv.co.uk/blog/movietalk/petes-peek-rogopag-1960s-social-satire-from-four-of-europes-finest-film-makers

Figure 19: Glovebox for handling hazardous material 92 Glovebox Gloves and Sleeves. (n.d.).

http://www.terrauniversal.com/glove-boxes/dry-box-gloves.php

Figure 20: Open my glade (flatten) (Pipilotti Rist, 2000) 95 Pipilotti Rist Public Art. (n.d.).

Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

http://www.hauserwirth.com/artists/25/pipilotti-rist/public-art/7/

Figure 21: The Transparent Factory in Dresden 97

Die Gläserne Manufaktur. (n.d.). Retrieved November 18, 2015, from https://www.glaesernemanufaktur.de/en/

Figure 22: Film still from Filme Socialisme (Jean-Luc Godard, 2010) 105 The BlowUp moment. (n.d.).

Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

http://theblowupmoment.blogspot.pt/2011/04/film-socialisme-jean-luc-godard-2010.html Figure 23: Screen shot of the website Sight to Site Film Locations 112 (n.d.).

Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

http://www.sighttositelocations.com/uploads/

Figure 24: Still from the BBC children’s TV series Teletubbies 117 Review of Teletubbies: Happy Birthday. (n.d.).

Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

http://www.myreviewer.com/DVD/93964/Teletubbies-Happy-Birthday-UK/93983/Review-by-Si-Wooldridge

Figure 25: Film still from Wall-E (Andrew Stanton, 2008) 120 Sci-fi interfaces. (n.d.).

Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

https://scifiinterfaces.wordpress.com/category/wall•e-2008/

Figure 26: The Naked City (Guy Debord, 1957) 123

ARTH Contemporary Study Guide (2013-14 Williams)-

Instructor Williams at Watkins College of Art, Design & Film - StudyBlue. (n.d.). Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

https://www.studyblue.com/notes/note/n/arth-contemporary-study-guide-2013-14-williams/deck/10071280

Figure 27: Map of the world in 1565 (detail) 124

(n.d.).

Retrieved November 18, 2015, from http://i.imgur.com/rgKO3Hw.jpg

Figure 28: Film still from The Truman Show (Peter Weir, 1998) 129 20 Movies: The Truman Show (1998). (2010, July 30).

Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

http://piddleville.com/2010/07/30/20-movies-the-truman-show-1998/

Figure 29: Mugshot of Martin Luther King, Jr. following 133 his 1963 arrest in Birmingham, Alabama

(n.d.).

Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:MLK_mugshot_birmingham.jpg

Figure 30: Film still from The Jewish Peril (Fritz Hippler, 1941) 134 Anti-faschismus. (n.d.).

Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

http://anti-faschismus.tumblr.com/post/70844182338/aestheticorthodoxy-le-péril-juif-1941 Figure 31: Detail from The Coral Reef (Mike Nelson, 2000) 135 (n.d.).

Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2010/jun/14/mike-nelson-coral-reef-masterpiece

Figure 32: Film still from The Lady in the Lake (Robert Montgomery, 1947) 140 Another Old Movie Blog. (n.d.).

Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

http://anotheroldmovieblog.blogspot.pt/2012/12/lady-in-lake-1947.html

Figure 33: Screen shot of the whysoserious website 146 WHY SO SERIOUS? (n.d.).

Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

http://www.42entertainment.com/work/whysoserious

Figure 34: Screen shot of the RTP website (Chibanga) 149 Rádio e Televisão de Portugal. (n.d.).

Retrieved November 19, 2015, from http://www.rtp.pt/programa/tv/p28091

Figure 35: Legendary bullfighter Ricardo Chibanga posing at 150 the sign of the street that was named after him in

the town of Golegã. (Thomas Behrens)

Behrens, T. (2007, October 27). Thomas.behrens-visual.com. Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

http://thomasbehrensvisualcom.blogspot.pt/search?updated-max=2007-10-27T15:45:00-07:00&max-results=7&start=14&by-date=false

Figure 36: Bullfight arena Monumental in Maputo, in 2014 151 Más de un mes en Namaacha, sur de Mozambique. (2014, July 22).

Retrieved November 18, 2015, from

https://bodhiroots.wordpress.com/2014/07/22/mas-de-un-mes-en-namaacha-sur-de-mozambique/

“Images contaminate us like viruses.”

Paul Virilio (b. 1932)Cultural theorist and Urbanist

ersatz

[er-zahts, -sahts, er-zahts, -sahts]

1. adjective

serving as a substitute; synthetic; artificial: an ersatz coffee made from grain.

2. noun

an artificial substance or article used to replace something natural or genuine; a substitute.

Word Origin: 1870-75; < German Ersatz a substitute (derivative of ersetzen to replace)

Introduction

My doctoral thesis on the subject Substitute Location has, as a result of an

artistic research project, a theoretical part (Semiotics and perception of Substitute Location in fiction film) and a practical part (a Road Movie). The central question of my thesis asks if the screen device is the contemporary expression of what Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) called phantasmagoria. In his essays, “Benjamin associates the

phantasmagoria with commodity culture's experience of its material and intellectual products, echoing Marx's use of the term in Capital.” (Cohen, 1989: 88)

In his 1939 essay On Some Motifs in Baudelaire,, Benjamin developed an original synthesis of Henri Bergson’s (1859–1941) philosophy of memory with Sigmund Freud’s (1856–1939) theory of trauma. Freud had argued in Beyond the Pleasure Principle that

traumatic experiences broke through the protective shield of individual consciousness and then returned as intrusive memories and disabling symptoms. Freud’s theory became for Benjamin an explanation of how cultural forms could also be approached as carrying the equivalent of unconscious memory traces and trauma. In his final theses On the Concept of History, Benjamin proposed that the critical practice of seizing upon these disturbing

images had the potential to shatter the dominant interpretation of the past. (Meek, 2007)

Today, the screen is not only the ‘protective shield’ that protects us from traumatic experiences, but also a central device for the functioning of global capitalism in the form of consumerism. Therefore, screens have to be everywhere. However, the fact that they are everywhere renders them also a banality, and as such, invisible. The inspiration for my artistic research comes from the French intellectual Georges Bataille (1897-1962), specifically from a text about art and cruelty:

As children, we have all suspected it: perhaps we are all, moving strangely beneath the sky, victims of a trap, a joke whose secret we will one day know. This reaction is certainly infantile and we turn away from it, living in a world imposed on us as though it were "perfectly natural", quite different from the one that used to exasperate us. As children, we did not know if we were going to laugh or cry but as adults, we "possess" this world, we make endless use of it; it is made of intelligible and utilizable objects. It is made of earth, stone, wood, plants, and animals. We work the earth, we build houses, and we eat bread and wine. We have forgotten, out of habit, our childish apprehensions. In a word, we have ceased to mistrust ourselves. Only a few of us, amid the great fabrications of society, hang on to our really childish reactions, still wonder naively what we are doing on the earth and what sort of joke is being played on us. We want to decipher skies and paintings, go behind these starry backgrounds or these painted canvases and, like kids trying to find a gap in a fence, try to look through the cracks in the world. (Bataille, 1993)

This section closes with an image that matches with the final shot of the movie

The Truman Show (Peter Weir, 1998). At the end, the protagonist Truman Burbank

faces an open door in the painted backdrop of a completely artificial world, which he held, until then, for the true and only existing world. Nobody had told him that he was the only real, non-acting person in this show. In my artistic research, such a perception of our immediate surrounding serves, as in the case of Truman, to prove that any environment is not only not immediate, but, moreover, conveys a sort of simulacra, a concept which was described by Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007) as a “third order simulacra, or simulation simulacra: based on information, the model, cybernetic play. Their aim is maximum operationality, Hyperreality, total control.” (Baudrillard, 1991)

Bataille believed that the ritual of sacrifice was mankind's culture's attempt to escape from the captivity of the simulacrum. Not only Bataille was fascinated by the tradition of bullfighting (Story of the eye, 1928), but also were many painters, like

Goya, Picasso, Dalí, but also Francis Bacon or Eric Fischl. I have chosen the subject of bullfighting for my practical work for two reasons: first, because in bullfighting, there are no screens. It is the opposite of a simulation. Secondly, because I learned that this seemingly anachronistic spectacle triggers distinct reactions in different spectators. A novel by Oedon von Horváth titled Der ewige Spiesser from 1929, describes a bullfight

in Barcelona, which leaves each of the three protagonists, travelers from Austria, with a distinct impression: disgust, grandiosity or sexual excitement. I was intrigued by the fact that one and the same phenomenon can lead to reactions that stand in quite extreme opposition to each other. For one spectator, something is deemed obscene while for the other, the very same thing is cheerful and uplifting. Could it be possible that one can hold these sensations all at once, combined?

Another observation left me intrigued: In a Portuguese or Spanish restaurant, the waiter would occasionally show me the raw dead animal, be it a fish or a hare, and ask for my approval: the waiter wanted to know if I preferred this particular fish grilled or baked on my plate - or the other one. Whenever I was having dinner with friends from countries like Germany or the U.S., I could feel the discomfort that this ritual of pre-approval would cause them. Obviously, there were worlds colliding in this very moment, and more than once, my friends would lose their appetite completely.

While some of the local customers would only order a meal that had been on display for approval, my friends could only enjoy their dinner if they were not obliged

to see the dead animal beforehand. Again, why is it that one and the same phenomenon results in distinct reactions? These questions are at the core of my investigation.

Bullfighting is a tradition (some stubbornly claim that Bullfighting is a form of art, or even the mother of all arts), which is no longer politically correct, for reasons that shall be investigated. My research will have come full circle with my practical work on a bullfighter, on a concrete biography, analyzed from multiple angles. In bullfighting, there resonates in a peculiar way the Freudian ‘death drive’ and it foreshadows that “every technology carries its own negativity, which is invented at the same time as technical progress." (Virilio, 1999: 89). Literary works such as James Graham Ballard's (1930–2009) Crash take up the issue of sacrifice and address it beyond any mythology:

the dimension of transcendence, that is inherent in all these phenomena, may apply for the spectator, but not for those involved, like Truman Burbank or the bullfighter or the victims of a car crash.

The child, it goes without saying, speaks of this to no one. He would feel ridiculous in a world where every object reinforces the image of his own limits, where he recognizes how small and "separate" he is. But he thirsts precisely for no longer being "separate," and it is only no longer being "separate" that would give him the sense of resolution without which he founders. The narrow prison of being "separate," of existence separated like an object, gives him the feeling of absurdity, exile, of being subject to a ridiculous conspiracy. The child would not be surprised to wake up as God, who for a time would put himself to the test, so that the imposture of his small position would be suddenly revealed. Henceforth the child, if only for a weak moment, remains with his forehead pressed to the window, waiting for his moment of illumination. It is to this wait that the bait of sacrifice responds. What we have been waiting for all our life is this disordering of the order that suffocates us. Some object should be destroyed in this disordering (destroyed as an object and, if possible, as something "separate"). We gravitate to the negation of that limit of death, which fascinates like light. For the disordering of the object, the destruction is only worthwhile insofar as it disorders us, insofar as it disorders the subject at the same time. We cannot directly lift the obstacle that "separates" us. But we can, if we lift the obstacle that separates the object (the victim of the sacrifice), participate in this denial of all separation. (Bataille, 1993)

This section resonates with Gilles Deleuze (1925-1995), who sees “simulacra as the avenue by which an accepted ideal or a privileged position could be challenged and overturned" (Deleuze, 1968: 69).

As object of my theoretical study, I have chosen a practice that is common in the area of feature film production. It should serve as a point of departure for my speculative journey, and this phenomenon is called Substitute Location. The theoretical work will expand the before mentioned concept, which consists in looking at an object from different angles, different points of view.

The James Bond movie Die another Day (Lee Tamahori, 2002) is one of many

mainstream movies, which illustrate this practice. The film has a plot that takes place in part in Havana, Cuba (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Havana, Cuba

Some of the scenes show actor Pierce Brosnan as Agent 007 walking along the famous Malecón in Havana, but these scenes were actually shot in Cádiz, Spain. (Fig. 2)

Figure 2: Cádiz, Spain

A location is a place where a film or a TV series is wholly or partially produced, in addition to the scenes that are shot in a film studio or on extra sets produced for the film. Since Roberto Rossellini and Italian neo-realism, many filmmakers prefer to shoot in real locations because they believe that they will catch more realism if they are in a real place, and not in an artificial studio set pretending to be a real place. The realists - among them many documentary filmmakers - assume, in the philosophical tradition of Aristotle, that the basic structures of reality are reliable, can be reflected by experience, in principle, and can be represented adequately in linguistic or other symbolic (iconographic) form. Until today, however, many fiction film producers shy away from the uncertainties of shooting on location: unstable weather, security issues, curious onlookers and many other aspects may threaten control of the production and thus of the film budget. Many movies shoot inside a studio and do additional recordings on location. It is often incorrectly assumed that the filming took place at the location where a scene is set within the action - but that's not always the case, as shown in the example of the James Bond movie.

The first ontological question therefore concerns the relationship between a real place and a location. It will be shown that the relationship could compare with the one between nakedness and nudity - take David Lynch's (b. 1946) film Blue Velvet (1986),

where the actress Isabella Rossellini is more than once shown as nude, and then, as she shows up on the street, confused and on the verge of a breakdown, she is no longer nude

– she is naked. The first thing one wants to do when seeing a naked and not a nude person, is to offer her some clothes to wear.

Again, although the object may seem one and the same from a factual standpoint, there exists a significant difference, and this difference is in our gaze, our perspective onto an object (be it a place or a person or a dead animal). Here, we are already employing the method of a parallax view, because we are able to consider the promenade in Cádiz as the Cádiz beach promenade or as the Malecón in Havana - it depends on which eye we close first to see how our object jumps before a fixed background.

For now, we content ourselves by stating that a location is an abstract concept, while a place is a concrete concept. Filmmakers and media professionals do not always distinguish clearly between these concepts, but as a rule of thumb we can say that scriptwriters, directors and producers who work in the area of fiction film, basically understand the location of a movie as an abstract concept. They do so in the philosophical tradition of the antirealists, or constructivists. Their approach is that the basic structures of reality are only projections of our thinking about the world. Whatever reality's nature is, regardless of our knowledge of it, is either not accessible for us, or, as more radical representatives of this position have it, is a pointless question, because reality is simply what we construct ourselves. In a strictly epistemological framework, these theories stand in insurmountable confrontation with each other; however, the ontological, descriptive content can match with the two concepts: one has to take into account that the anti-realistic, constructivist position just considers that we have created the structures in the perception process whereas the realist claims that these structures exist in the world – regardless if there is an observer or not.

Fiction film producers are motivated by the desire to control the production process and the look of the film as tightly as possible; among other things they do so because of the associated production costs. It is therefore no surprise that, with the advent of digital, computer generated image (CGI) sets, more and more movies resort to digital or semi-digital settings.

Documentary filmmakers, on the contrary let the camera run for many hours, only to see if something unexpected happens. They hope for some contingency outside

of their perception that would surprise them. They look for something they have not designed or even thought of. This practice must seem downright absurd for the producers of fiction films, for the above-mentioned reasons: it is waste of time and money. Another question of my research deals with the effects that the tendency to use digital sets has on our concept of reality. I think it goes without saying that the producers of the James Bond movie had no interest to trigger a sort of alienation effect inspired by Bertolt Brecht (1898-1956) in the cinema audience. Most probably it was necessary to find an alternative for the location of Havana, especially since it was not allowed for the production to shoot in Cuba. The plot had to be set in Havana, but for the production department, Havana was impossible, hence someone had the idea to use Cádiz as a replacement for Havana. (Fig. 3)

Figure 3: Film still from Die another day (Lee Tamahori, 2002)

For those in the audience who know Havana well, the sudden presence of lampposts on the Malecón and the absence of some typical socialist architecture could seem strange, and, scratching their heads, they could claim ‘That is not Havana!’ just as the child in Hans-Christian Andersen's (1805-1875) tale The Emperor's New Clothes

(1837) bursts out: ‘But the Emperor is naked!’ The, in this case unintentional, alienation effect could trigger a generalized sensation of disbelief; it could further completely spoil the enjoyment of two hours of entertainment. Usually, what happens is, of course, exactly the opposite in the mind of the viewer: the uneasy feeling of disbelief and cognitive dissonance is quickly pushed aside with the argument that this is a film, a

work of fiction, and the producers of fiction films are held accountable to make clear immediately at the beginning of each movie with a standard disclaimer: “This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.” (TVtropes, n.d.) Why should we expect truth or some analogy with reality, if the whole film is just a work of fiction? Had the film been made entirely with digital, CGI images, including those of Havana, no spectator would even think to complain about eventual inconsistencies.

However, the question would be much more complicated, had the film claimed to be a documentary, a non-fiction film, or a news report. We should be allowed for a moment to consider our reaction as spectators, if we realized, watching the news in the evening that some shots of Cádiz, Spain would be presented to us with the written label ‘Havana’. (Fig. 4)

Figure 4: Cádiz with the label ‘Havana’

My guess is that we would first ask whether this was a mistake. If we learned that this was done deliberately, to have us believe that the material had actually been gathered in Havana, that would qualify, in fact, as a scandal. Let us further imagine our reaction if the editor tried to justify the use of footage from Cádiz with the argument that he had no permission to shoot in Havana. That would be ridiculous and scandalous at the same time. The editor would then even go on to explain that the entire reasoning of the news report was not in any way affected or hampered by the replacement footage and that the message of the report is no less relevant due to the use of images from Cádiz. He wasn't able to get hold of some current pictures of Havana, where is the

problem? Well, we would argue that there is no moral or ethical justification to do this. News must be presented with facts and may not lie to us or mislead us in such blatant ways. We would ask back how we are to believe the entire reasoning of the report since our trust in the whole institution had been lost already due to this gross negligence.

This example shows us two different categories of perception. The media perpetuates the conflicts of ancient theorist who took very different epistemological positions, championing the reality principle or constructivist positions with regard to problems, which seem one and the same from an ontological position. Depending on whether we focus on the mimetic faculty of the film or its diegetic dimension, we also look for different truths. It follows that from the very outset, our perception is guided and regulated by ethical standards.

Throughout my dissertation, I will analyze examples of artistic works, especially, but not exclusively from fiction films, in order to operate a dialectical exploration, in which the well-established concept of Substitute Location will be transformed into a broader concept, which I label ‘substitute location’. This new concept aims at consciously creating a sensation of cognitive dissonance, yet not longer unintentionally and involuntarily, as abovementioned in the James Bond movie. These operations of dialectical processes may then serve as a driving force for further explorations in the fields of perception and semiotics. The chosen method for the creation of my work follows the logic of this duplicity; it is a parallax view, or a dialectics of seeing. This alternating point of view contrasts the site as a concept of a lifeworld with the place as a description of a position within a structure. Places survive today often only in images that bear witness to their existence, and the images have to carry all the memory. The spatial concept, and with it the concept of identity, are increasingly caught in transformation, since places in earlier periods represented duration - and now this duration is lost. Because we know many places only as pictures, they have won a presence of another kind. The relation of image and location is shifting. Today, we do not visit certain places, but the images of these places, just as we visit locations in an image. The electronic images have become places without substance. They are without a body, which could serve as an anchor. Once the locations are lost in the real world, they retreat into images, giving them an alternative status as a place. In the specific case of my investigation, they become substitute locations.

The overall methodology set out for the project is founded in artistic research, which is, in my case, a hybrid research approach, with some qualitative elements, but predominantly reflexive, since my practical work never pretends to seek evidence, but rather, should serve to illuminate and exemplify my theoretical findings, and vice versa. My theoretical analysis as well as my fieldwork is systematically guided by the principles of Psychogeography. There is no universal definition of what Psychogeography means, however, this discipline was undoubtedly influenced, if not created by Guy Debord (1931–1994) and the Situationist International (SI). The body

of work which has been created by the SI may seem trivial today, but I think that the current state of our society, which has raised passive consumption and its prerequisite, individual financial success, to the measure of all things, can not only be grasped but also be effectively countered with the methods and strategies of the SI. Psychogeography endeavors to develop relevant insights into past, contemporary and future environments, and today, these environments are constructed to a significant degree by mass and social media. In some respect, Psychogeography seeks to reclaim a form of travel that was once synonymous with adventure. Today, one can only state a demise of real travel that is no longer heroic or individualizing. Psychogeographers are disenchanted at the ease with which modern travelers move around the globe, taking no risks and facing no unknowns. Prior to the breakdown of global barriers in the semiosphere, travel was not an almost instant change of places, but a transforming event filled with historical and psychological significance.

The Situationist International was undertaking a rebellion in principle against

the pervasive uniformity and boredom of urban space. It stood for a revolution of daily life, caused by art, protest and aimless walking. Drifting (dérive) became one of its

central tactics and it grew finally into Psychogeography, an interdisciplinary practice, still waiting to gain full recognition in academic circles. Psychogeography demands from its practitioners to depart from routines, particularly from unquestioned mental tracks, to take different approaches off the beaten paths or to wander in new ways on the all-too-well known ones, to understand that it takes new experiences and free creation to define our lives. Today, Psychogeography could be useful as an active resistance strategy against the ongoing mediatization and commercialization of all areas of life.

The common feature of all Psychogeographers is, however, the habit of walking as creative practice, since travel as drifting has a three-part structure: departure -

passage – arrival. And so does its equivalent in creation: project - process - product.

When I start to walk, I must, from the outset, choose between two options: do I want to go to a specific destination on a predetermined route, perhaps even within a certain timeframe - or will I wander randomly, without knowing where I arrive and how long the walk will be? It is obvious that most people generally choose the former option, while the Psychogeographer prefers the latter. Most people will argue that it is the constraints of everyday life that determine this kind of movements. One should act efficiently, effectively and purposefully - this is a maxim of the capitalist ethics, which is rarely questioned. The word ‘should’ already indicates that this maxim is rooted in religion, where rules have been established and a catalogue of right or wrong behaviors such as the Ten Commandments had been issued. The moral and ethical buildings are

defined by appeal and command.

Today, there is also the Constitution and the Civil Code, in addition to the Ten Commandments but the most powerful individual structure is the super-ego, which

keeps our drives and emotional impulses (id) under control. The super-ego stands for the human ability to put brakes on actions that are emotionally triggered, or to make them, at least, more socially acceptable. Consciousness learns first from the closest caregivers (parents, teachers, etc.), which emotions are admitted and to what extend and how to, if necessary, suppress, or sublimate them. Later in life the super-ego provides us with alternatives to the programs that are already designed in the part of the brain that triggers emotions and which responds to external stimuli. As a result, it makes us more flexible and at the same time adaptable to complex situations. Depending on the context, the super-ego can also completely inhibit and paralyze, or install erratic, even pathological behavior. Human progress, according to Humanism, should rely mainly on the ability to control emotions, to be able to stop or modulate them. Aristotle (384 – 322 BC) described humans as the ‘rational animal’ but Sigmund Freud was skeptical. The irrational forces of the id put the weak ego under too much pressure. This also explains the suffering of many people, who feel helpless towards and overwhelmed by their emotions (they become addicted, behave aggressively, have eating disorders, suffer from anxiety disorders, etc.) and cannot understand that these problems are the price

that we have to pay to be able to live in a civilized society. It is extremely difficult to control emotions with the mind. This is because there are more nerve connections for passing information from the centers of emotion to the center of the conscious mind than vice versa. The part of the brain that is responsible for emotions has thus far more influence than the reasoning part. However, pure rationality, applied in excess, proves sometimes even more inhumane and cruel as the much maligned, suppressed and denied, deemed bestial, barbaric and demonic id. In this context one has to ask the question if the problems that are caused by a too much of emotion are not precisely a result of a so-called civilization, which, in its quest for seamless technological efficiency, is no longer able or willing to deal with feelings. Marquis de Sade (1740 – 1814) had prophetically foreseen this time. Any passion crime was for him rather an expression of humanity whereas the death penalty, which he opposed vehemently, was a sign of the cold, inhuman side of the law which functions like the indifferent machine in Franz Kafka’s (1883 –1924) In der Strafkolonie (1914).

Sigmund Freud called this dilemma the Uneasiness, or Discontent in Civilization and his investigations were running parallel to the industrial revolutions and the World Wars. Jacques Lacan, who added a topological dimension to the psychology of Sigmund Freud, described what we call the ego as a very narrow domain, which is under permanent siege, and the ego can easily lose ground against the super-ego or the id, as everyone who has ever been in a stressful situation, will readily admit.

My idea of a collective super-ego is that of a tourist city map; it tells us exactly where we should turn our gaze, which routes are recommended and what areas we should better avoid. These city maps usually leave no room for our own imagination.

Until now, we have always had large reserves of the imaginary, because the coefficient of reality is proportional to the imaginary, which provides the former with its specific gravity. This is also true of geographical and space exploration: when there is no more virgin ground left to the imagination, when the map covers all the territory, something like the reality principle disappears. (Baudrillard, 1991)

In most modern cities, there exists nonetheless an area where aimless strolling is strongly encouraged: it is the pedestrian zone with its many shop windows. Here, in the arcades, we are supposed to let loose, to dream away and be seduced to purchase questionable items. If we expand this geographical approach a bit further, we could

conclude that media is also part of the collective super-ego; media tells us what we should want, what we should dream of and what we have to be afraid of. Unlike anything else, media is pre-formatting our perspective on the world - it is not so much the content itself that counts, since it is constantly changing, but the gaze, which is formatted and takes on a standard which is then applied to every phenomenon - in the same fashion as an industrial DIN norm is applied to a variety of products.

The task of a Psychogeographer is to position himself as a stranger who comes from the outside, to break with firm or encrusted structures. It will be shown that any procedure of finding meaning is never complete if it stops short by analyzing a given phenomenon. A dialectics of seeing must leave the sphere of ontology in the sense of taxonomy since ontology works only descriptively and cannot explain the why behind a certain question. This is where special metaphysics goes deeper, in our case the attempt of an explicit conceptualization of media phenomena, arising from (in)congruencies between psychological and geographical spheres.

As in a criminal investigation, it is not sufficient to discover the perpetrators of a crime; is it perhaps even more important to ask why the crime was committed and what can be done in general to prevent such crimes. (If, such as in Nazi Germany, the crime was helping a Jew to survive, then the corresponding procedure to find meaning at the time, would have been to show that Nazi laws are inhumane and should be abolished. It is easy to indicate this today when everyone else has already adopted this point of view, but at the time, it would have been paramount to do just that).

The procedures to find meaning are only effective or even possible in specific situations. The situation as such may typically not seem obvious, since we tend to repress the fundamental inconsistency of being, mostly because we tend to conform to a widely accepted ideology, as the story of The Emperor's new Clothes shows. Certain

social conventions may protect us and our fellow human beings from the cruelty of the naked truth, and denial can go long distances, as in the saying of the ‘elephant in the room’, which everyone notices, but nobody mentions.

The following is a list of objectives set out for the project:

• Understand the theories of realism versus constructivism in relation to an urban context and to media space.

• Understand and commit to psychogeographic theory and practice in order to develop a dialectics of seeing and a parallax view.

• Apply psychogeographic theory and practice to media space in order to analyze films and artworks and develop the concept of substitute location further, reading the term 'substitute' in the Freudian sense of ersatz as in ersatzhandlung or ersatzbefriedigung

• Understand the passive and interactive role of screen devices in contemporary consumerist culture.

• Exemplify the feedback loops that media space generates in the formation of identity and its ideological interpellation

• Apply psychogeographic theory and practice to urban space in order to develop new and original approaches to the creation of films and photographs.

• Make a film that departs from a psychogeographic concept, as a détournement from the Road Movie genre

My own dialectical position seeks the confrontation of the realist and the constructivist perspectives and locates meaning right in the gap between these two discourses. In Jacques Derrida's (1930-2004) words, my task is to seek for “iterability as a differential structure (that) escapes the dialectical opposition of presence and absence, and instead implies both identity and difference.” (Anderson, 2012: 84)

The first part of this thesis will analyze a conventional, realist, non-mediatized concept of place, the influence of place on identity and a structuralist reading of place as location. In the second part, I will suppose that with mediatization, a pure realist concept of place has become impossible. Media space has supplanted all common ground in the lifeworld and it is now ubiquitous. The third part then seeks to answer the question if media space is inhabitable, and what would the ‘outside’ of this space look like? This question inverts the dichotomy gaze/body and assumes that we live in the world of the ideologically tinged gaze and look back at an arbitrary/indifferent world of

bodies. The fourth part finally is a reflection on my own film, which is in itself an attempt to construct a dialectical image.

Figure 5: The signifier as a symbol of an absence

As shown in Fig. 5, the Real has to pass through the membrane of the Imaginary, to become part of the Symbolic. The Real itself opposes and resists any representation; it is something that remains always on the outside - even if it is the Real of our own body, the Real of our own sensations. In other words, the place we usually call Cádiz, is only Cádiz if we apply the filter-membrane of non-fiction. As soon as we enter the territory of the fiction narrative (in this case a James Bond story), we are allowed to name the place formerly known as Cádiz ‘Havana’, since we applied as a filter-membrane the diegetic sphere of the film universe. Any given phenomenon must therefore always be embedded in its specific diegetic universe (discourse/ narrative), and this classification immediately requires a moral or ethical stand. This circumstance is inscribed in the term ‘point of view’, to express that a topographic dimension is, at the same time, a visual perspective and an opinion, a judgment obviously shaped by specific ethical or moral values and considerations.

The image or the sequence of images in a fiction film that depict a Substitute Location could thus be equated with the ‘floating signifier’ in the context of social interactions, since a “floating signifier may mean whatever their interpreters want them to mean. Such a floating signifier necessarily results to allow symbolic thought to operate despite the contradiction inherent in it.” (Mehlman, 1972: 10-37)