This study describes the structure of oral health services in primary health care in Brazil and the instruments available for the provision of oral health care and to compare the number of instruments according to organizational characteristics of health services and among the macroregions. Of the 23,251 oral health teams (OHTs) in the Public Health System, 17,513 (75.3%) participated in this study. Trained researchers observed the structures of the health services and determined the presence of and whether a sufficient quantity of 36 dental instruments existed. The score of each oral health service was determined by the sum of the number of dental instruments present in sufficient quantity (0 to 36). Central tendency measures were compared along with the variability in these scores according to the organizational characteristics of the services and according to the Brazilian macroregion. No instrument was found to be present in all evaluated services. Basic, surgical and restorative instruments were the most frequently found. Periodontal, endodontic and prosthetic instruments exhibited the lowest percentages. The mean and median numbers of dental instruments were higher for teams that operated over more shifts, those with an oral health technician and those in the South and Southeast regions. The oral health services were equipped with basic, surgical and restorative instruments. Instruments designed for periodontal diagnosis, emergency care and denture rehabilitation were less frequently found in these services. The worst infrastructure conditions existed in the OHTs with the worst forms of care organization and in regions with greater social issues.

A Survey About Dental Instruments

at the Primary Health Care in Brazil

Joyce Lopes1, Andréa Clemente Palmier1, Marcos Azeredo Furquim Werneck1, Antônio Thomaz Gonzaga da Matta-Machado2, Mauro Henrique Nogueira Guimarães de Abreu1

1Department of Community and Preventive Dentistry, School of Dentistry, UFMG – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil

2Department of Preventive and Social Medicine, School of Medicine, UFMG – Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil

Correspondence: Mauro Henrique Nogueira Guimarães de Abreu, Av. Antônio Carlos, 6627, 31270-901, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil. Tel.: + 55-31-3409-2434. e-mail: maurohenriqueabreu@gmail.com

Key Words: Primary health care, oral health, dental instruments, public health dentistry.

Introduction

Public oral health policies have achieved important advances in recent decades in Brazil. The proposal to create polyarchic health care networks implies the construction of integrated practices in the Brazilian Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde – SUS, in Portuguese)

while respecting the characteristics of each region, which will enable the actions of oral health teams (OHTs) to become more effective and strengthen the attributes of first contact, longitudinality, completeness and coordination within Primary Health Care (PHC) (1,2). Data from February 2016 indicate the existence of at least one OHT in 5,007 Brazilian municipalities (89.9% of the total). Given this scale, it is important to evaluate oral health actions in Brazil. In 2014, the Brazilian Ministry of Health organized a second cycle of a program aiming to evaluate and improve PHC quality. This was called the National Program for Improving Access to and Quality of Primary Care (Programa Nacional de Melhoria do Acesso e da Qualidade da Atenção Básica - PMAQ-AB, in Portuguese),

which examined, among other factors, the structure of PHC oral health services, (3) as an adequate health equipment and the presence enough instruments should be considered when evaluating PHC quality (4,5). After the evaluation of the OHT, the performance will be classified as excellent,

very good, good, fair or poor. The amount of financial incentive that the health manager will receive depends on the team’s certification in relation to performance. For the purposes of team certification, some quality standards are evaluated. Dental instruments are classified as essential, meaning that OHT with no conformity to the PMAQ-AB standard will have their performance impaired (3).The World Health Organization recommends that the structure of health facilities should be monitored at a national level (6). In the health evaluation field, physical structure is one of the components highlighted by Donabedian, (7) who believes that good structural conditions are a prerequisite for good processes and increase the likelihood of a positive outcome. The health service’s structure is considered a key component in the analysis of a health care system. Although the presence of a good structure does not necessarily lead to good processes and results, one cannot ignore the importance to health outcomes of an adequate structure (7,8).No studies in the literature have examined the effect of organizational factors of health services on the oral health service infrastructure. Little is known about how to

Dental instruments at primary health care the creation of the Family Health Strategy (FHS), which

provides for the reorganization of PHC in the SUS and a

reformulation of the current health care model in Brazil, concern exists regarding its structuring and strengthening (10). Brazilian law places importance upon issues pertaining to the structure and funding of health services, with a priority of structuring the Basic Health Units in the form of Family Health teams (11).

Despite the expansion in populational coverage by the OHTs, for the activities proposed in this strategy to be performed in a quality manner, it is necessary that health facilities have a minimum structure (3). Specifically, clinical actions for dental care require sufficient equipment, instruments and materials to meet the health care demands required due to the oral disease burden (12).

Despite the large investment that has been made in the OHT structure, (10,11) factors that might explain differences in this structure among different oral health services have not been evaluated. Thus, to examine a topic that has rarely been researched in the organization of primary oral health care, that is, whether the organizational processes of oral health services affect their infrastructure, this study describes the structure of Brazilian PHC oral health services, focusing on the instruments available for the provision of oral health care. The study also compares the number of instruments according to organizational characteristics of the oral health services and according to Brazilian macroregion.

Material and Methods

The study was approved by the National Council for Research Ethics and by the Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais - UFMG) (Protocol CAAE 02396512.8.0000.5149). Data from the Brazilian Public Ministry of Health were analyzed, and no participant was identified at any stage of this study.

Of a total of 23,251 OHTs in Brazil in January 2014, 19,946 (85.8%) participated in this second PMAQ-AB cycle. Of these, 2,433 were not included because they did not follow PMAQ-AB regulations. Thus, 16,202 PHC oral health services were evaluated, corresponding to 17,513 (75.3%) OHTs.

An observational instrument, developed through a partnership between the Ministry of Health and six teaching and research institutions in Brazil, was applied by a team of trained health professionals with university degrees. After a pilot study, the questions and observations were recorded on tablets using a program designed specifically for the PMAQ-AB. The program contained photos of equipment and criteria for evaluating the presence (existence of at least one unit) and sufficient quantity (existence of a

quantity sufficient to meet the needs of the service, i.e., to perform oral health care during 40 hours per week) of the instruments, based on Ministry of Health regulations. The list of dental instruments was drawn randomly in the program. The observational instrumental was developed to prevent possible last minute purchases or instrumental loans. The teaching and research institutions validated the questionnaire responses. The Ministry of Health organized the database and made it available to the teaching and research institutions. A certification of the interviewer´s presence was made with a sample of the study, by phone.3

The questions were predominantly dichotomous and evaluated the presence of 36 clinical instruments from different clinical dentistry areas, including instruments for performing restorative, surgical, endodontic, prosthetic and periodontal procedures and clinical instruments used in various dental care areas. This variety of instruments is justified due to the scope of procedures performed by the OHT (emergency care, preventive care, restorations, oral surgery, basic periodontal treatment, dental prostheses). It is important to point out that OHT covers all age groups, from early childhood to seniors. Thirty-six instruments were defined in the list of Essential Dental Instruments of the Ministry of Health.

In addition to these variables, several oral health service characteristics were evaluated using structured interviews with the dental surgeons, including dental care shifts, performing dental care between 12pm and 2pm and at night; type of OHT (dentist and oral health assistant; dentist, oral health technician and oral health assistant; or no adherence to the FHS); and instrument sharing with other OHTs.

The statistical analysis involved the calculation of ratios for each evaluated instrument. The score of each oral health service was calculated as the sum of the number of dental instruments present in sufficient quantity (0 to 36). The central tendency measures were compared along with the variability in these scores according to organizational oral health service characteristics and geographical regions within Brazil. Confidence intervals and inferential statistics were not calculated because this was a census study of teams that had joined the second PMAQ cycle. The decision to not perform statistical tests and hence to not show p

values was also due to the number of evaluated OHTs, which could lead to the identification of statistical associations even where there were no relevant differences between groups (13). All analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows version 19.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, USA).

Results

J. Lopes et al.

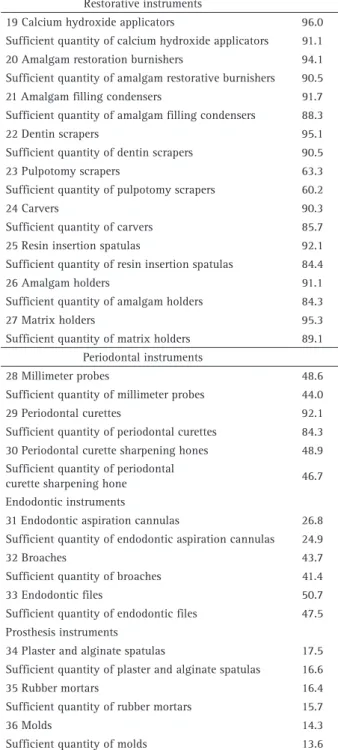

in the evaluation of the second PMAQ-AB cycle in 2013 and 2014. Basic, surgical and restorative instruments were the most frequently found instruments. Periodontal, endodontic and prosthetic instruments exhibited the lowest percentages.

The analysis of the number of instruments present in each oral health service (Fig. 1) showed that only 0.4% of these services (n=66) had all 36 dental instruments. One-quarter of the oral health services had up to 23 dental instruments, the median number was 27 instruments, and three-quarters of the teams had up to 30 instruments.

The different forms of oral health service organizations exhibited differences in the number of available instruments. Services that offered more shifts and longer opening hours had more instruments available. OHTs including an oral health technician (OHTech) and those sharing instruments with other OHTs reported a higher number of dental instruments (Table 2).

The mean and median values for the number of dental instruments were higher in the South and Southeast regions and lower in North, Northeast and Central-West Brazil (Table 3).

Discussion

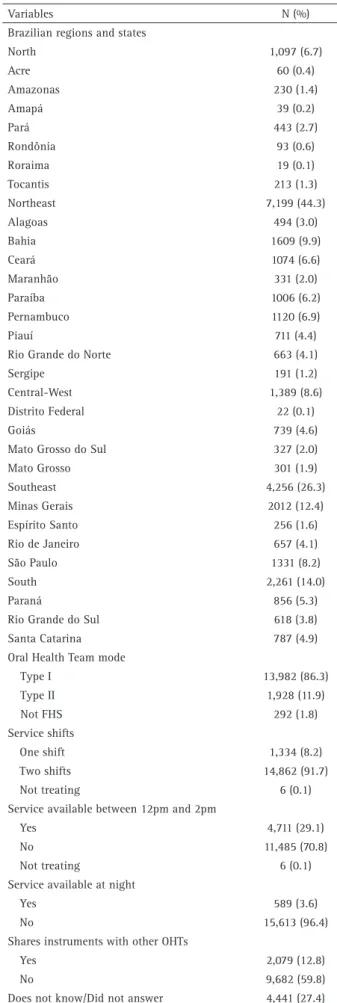

Health service infrastructure is a key component in the quality of a health system (5). PHC oral health services in Table 1. Description of primary oral health care units, SUS, Brazil,

2013-2014 (n=16,202)

Variables N (%)

Brazilian regions and states

North 1,097 (6.7)

Acre 60 (0.4)

Amazonas 230 (1.4)

Amapá 39 (0.2)

Pará 443 (2.7)

Rondônia 93 (0.6)

Roraima 19 (0.1)

Tocantis 213 (1.3)

Northeast 7,199 (44.3)

Alagoas 494 (3.0)

Bahia 1609 (9.9)

Ceará 1074 (6.6)

Maranhão 331 (2.0)

Paraíba 1006 (6.2)

Pernambuco 1120 (6.9)

Piauí 711 (4.4)

Rio Grande do Norte 663 (4.1)

Sergipe 191 (1.2)

Central-West 1,389 (8.6)

Distrito Federal 22 (0.1)

Goiás 739 (4.6)

Mato Grosso do Sul 327 (2.0)

Mato Grosso 301 (1.9)

Southeast 4,256 (26.3)

Minas Gerais 2012 (12.4)

Espírito Santo 256 (1.6)

Rio de Janeiro 657 (4.1)

São Paulo 1331 (8.2)

South 2,261 (14.0)

Paraná 856 (5.3)

Rio Grande do Sul 618 (3.8)

Santa Catarina 787 (4.9)

Oral Health Team mode

Type I 13,982 (86.3)

Type II 1,928 (11.9)

Not FHS 292 (1.8)

Service shifts

One shift 1,334 (8.2)

Two shifts 14,862 (91.7)

Not treating 6 (0.1)

Service available between 12pm and 2pm

Yes 4,711 (29.1)

No 11,485 (70.8)

Not treating 6 (0.1)

Service available at night

Yes 589 (3.6)

No 15,613 (96.4)

Shares instruments with other OHTs

Yes 2,079 (12.8)

No 9,682 (59.8)

Does not know/Did not answer 4,441 (27.4)

Dental instruments at primary health care Brazil have shortages of the instrumentation necessary

for performing dental care, and differences exist among OHTs according to organizational characteristics and across different Brazilian regions.

The evaluated dental instruments can be considered to form part of the minimum necessary equipment to perform PHC procedures. The lack of these instruments, as identified in this study, may be important in defining the work process and may hinder access to and the quality of oral health services (14,15).

In addition to the high frequency of basic dental

instruments that are used for many clinical interventions, surgical and restorative instruments, with few exceptions, were most commonly identified in the oral health services. This finding may reflect the fact that surgical-restorative practice is still very common in Brazil (16,17), despite the major changes that have occurred in public policy in recent years (1). However, the oral disease burden in the country, identified in recent epidemiological oral health surveys (12), requires the performance of surgical and restorative procedures, for which the Brazilian oral health services seem to have a good structure.

Table 2. Frequency of dental instruments in primary oral health care, SUS, Brazil, 2013-2014 (n=16,202)

Basic instruments %

1 Steel trays 92.3

Sufficient quantity of steel trays 84.5

2 Boxes with stainless steel covers 85.1

Sufficient quantity of boxes with stainless steel covers 77.6

3 Dental mirrors 98.4

Sufficient quantity of dental mirrors 91.7

4 Dental tweezers 98.3

Sufficient quantity of dental tweezers 93.9

5 Glass plates 97.9

Sufficient quantity of glass plates 91.5

6 Carpule syringes 98.6

Sufficient quantity of carpule syringes 93.9

7 Exploratory probes 96.7

Sufficient quantity of exploratory probes 93.0

Surgical instruments

8 Extracting forceps 81.6

Sufficient quantity of extracting forceps 74.6

9 Elevators 98.4

Sufficient quantity of elevators 91.9

10 Scalpel handles 90.9

Sufficient quantity of scalpel handles 83.0

11 Surgical curettes 86.9

Sufficient quantity of surgical curettes 81.1

12 Child forceps 89.1

Sufficient quantity of child forceps 79.4

13 Adult forceps 98.3

Sufficient quantity of adult forceps 96.1

14 Bone files 67.4

Sufficient quantity of bone files 61.7

15 Needle holders 96.9

Sufficient quantity of needle holders 90.1

16 Syndesmotomes 89.3

Sufficient quantity of syndesmotomes 84.1

17 Surgical aspirators 34.5

Sufficient quantity of surgical aspirators 32.7

18 Surgical scissors 93.4

Sufficient quantity of surgical scissors 84.6

Restorative instruments

19 Calcium hydroxide applicators 96.0

Sufficient quantity of calcium hydroxide applicators 91.1

20 Amalgam restoration burnishers 94.1

Sufficient quantity of amalgam restorative burnishers 90.5

21 Amalgam filling condensers 91.7

Sufficient quantity of amalgam filling condensers 88.3

22 Dentin scrapers 95.1

Sufficient quantity of dentin scrapers 90.5

23 Pulpotomy scrapers 63.3

Sufficient quantity of pulpotomy scrapers 60.2

24 Carvers 90.3

Sufficient quantity of carvers 85.7

25 Resin insertion spatulas 92.1

Sufficient quantity of resin insertion spatulas 84.4

26 Amalgam holders 91.1

Sufficient quantity of amalgam holders 84.3

27 Matrix holders 95.3

Sufficient quantity of matrix holders 89.1

Periodontal instruments

28 Millimeter probes 48.6

Sufficient quantity of millimeter probes 44.0

29 Periodontal curettes 92.1

Sufficient quantity of periodontal curettes 84.3

30 Periodontal curette sharpening hones 48.9

Sufficient quantity of periodontal

curette sharpening hone 46.7

Endodontic instruments

31 Endodontic aspiration cannulas 26.8

Sufficient quantity of endodontic aspiration cannulas 24.9

32 Broaches 43.7

Sufficient quantity of broaches 41.4

33 Endodontic files 50.7

Sufficient quantity of endodontic files 47.5

Prosthesis instruments

34 Plaster and alginate spatulas 17.5

Sufficient quantity of plaster and alginate spatulas 16.6

35 Rubber mortars 16.4

Sufficient quantity of rubber mortars 15.7

36 Molds 14.3

J. Lopes et al.

The lack of instruments necessary for the clinical diagnosis of periodontal disease in more than half of the oral health services is troubling. One of the principles of PHC is first contact (18), and in this regard, oral health care in the SUS provides the first scheduled dental appointment, which defines the clinical diagnosis to perform a preventive and therapeutic treatment plan (19). The diagnosis and treatment of periodontal disease in PHC is therefore important, given the disease burden and its interrelationships with systemic conditions (20).

Table 3. Comparison of the distribution of instrument presence scores (0 to 36) primary oral health care, SUS, Brazil (n=16,202) according to the health service’s organizational features, 2013-2014

Variable Mean (SD) Minimum Median Maximum

Service shifts

One shift (n=1,334) 22.50 (7.51) 0 24.00 36

Two shifts (n=14,862) 25.63 (6.14) 0 27.00 36

Not treating (n=6) 9.33 (14.51) 0 0.00 30

Service available between 12pm and 2pm

Yes (n=4,711) 25.77 (6.20) 0 27.00 36

No (n=11,485) 25.20 (6.38) 0 26.00 36

Not treating (n=6) 9.33(14.51) 0 0.00 30

Service available at night

Yes (n=589) 28.01 (6.15) 0 30.00 36

No (n=15,613) 25.26 (6.33) 0 26.00 36

OHT Mode

Type I (n=13,982) 25.15 (6.34) 0 26.00 36

Type II (n=1,928) 26.94 (5.95) 0 28.00 36

Not FHS (n=292) 25.39 (7.14) 0 27.00 36

Shares instruments with other OHTs

Yes (n=2,079) 25.66 (6.58) 0 27.00 36

No (n=9,682) 25.11 (6.25) 0 26.00 36

Does not know/Did not answer (n=4,441) 25.79 (6.41) 0 27.00 36

Table 4. Comparison of scores for the presence of instruments (0 to 36) primary oral health care, SUS (n=16,202), among Brazil’s five geographic regions, 2013-2014

Brazilian region Mean (SD) Minimum Median Maximum

North (n=1,097) 21.59 (8.20) 0 24.00 36

Northeast (n=7,199) 24.09 (6.41) 0 25.00 36

Central-West (n=1,389) 26.08 (6.38) 0 27.00 36

Southeast (n=4,256) 27.00 (5.20) 0 28.00 36

South (n=2,261) 27.71 (5.08) 0 29.00 35

The low numbers of endodontic instruments and curettes for pulpotomy may make the treatment of acute cases of odontogenic origin inviable and compromise the service’s ability to resolve issues, especially due to the relatively high prevalence of dental pain in Brazil (21).

Frequent and early tooth loss in the Brazilian population has led to the generation of policies to address its causes and its consequences. In this regard, the fitting of dental prostheses in PHC may increase access, especially among the adult and elderly population, to rehabilitation

procedures (22). Although it is not the only complicating factor of access to oral health services, the frequent absence of prosthesis instrumentation may contribute to the non-performance of such procedures in the PHC of most services, as has been identified in another study (23).

One of the characteristics of oral health in the FHS is the presence of oral health assistants and technicians. International studies (24,25) have suggested that the inclusion of these professionals in health teams can increase service access and productivity and reduce disparities in oral health and health care costs. Accordingly, the fact that OHT type II services (with an Oral Health Technician) have a greater mean number of instruments than type I services (without an Oral Health Technician) is consistent, as the inclusion of an Oral Health Technician facilitates increased productivity.

Dental instruments at primary health care cross-sectional design of this study, it is not possible to

ascertain whether the presence of an increased number of instruments was a cause or consequence of different working process strategies.

The regional differences identified in this study are similar to those found in other Brazilian oral health service evaluations (23) and likely reflect the social and economic diversity of the country. Previous studies have shown that social differences, including those identified at the municipal level, are key to the organization of oral health services and should be considered when formulating organizational strategies for these services (19).

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution regarding the external validity, given the significant percentage of OHTs that were not involved in the PMAQ-AB. It is not possible to define objectively the reliability and reproducibility of each measurement made by the trained researchers in this survey. Moreover, it is known that infrastructure of the OHT is more than dental instruments. The reason for describing dental instruments is based on the fact that there is a standardization of the minimum instruments necessary for the development of actions in primary care in oral health, which does not occur for other items analyzed by the PMAQ. The diagnoses of the structural conditions of oral health services of PHC at a national level are rare in the scientific literature, and such a diagnosis can contribute to advances in the planning and scheduling of oral health actions. In the case of the evaluated PHC system, a need was identified to improve the availability of dental instruments to satisfactorily meet the epidemiological reality of the Brazilian population. An inability to resolve the demands of the population due to a lack of adequate infrastructure has likely been an important factor in the work process and, ultimately, in outcomes in terms of morbidity, satisfaction and quality of life of the population served. World Health Organization has pointed out the relevance of evaluating inputs, outputs and outcomes in health services evaluation and monitoring (26, 27). In this regard, robust analytical studies, with outstanding quantitative methods (28), should be conducted to examine the associations between structure, process and results, given the need to really understand the relationship between these quality dimensions (7), especially in oral health services.

The studied Brazilian oral health services were equipped with basic, surgical and restorative dental instruments. Instruments designed for periodontal diagnosis, emergency care and prosthetic rehabilitation were less frequently found in these establishments. The worst infrastructure conditions existed in the OHTs with the worst forms of care organization and in regions with greater social issues.

Resumo

Este estudo descreve a estrutura dos serviços de saúde bucal na atenção primária em saúde no Brasil e os instrumentos disponíveis para a assistência à saúde bucal e compara o número de instrumentais de acordo com as características organizacionais dos serviços de saúde e entre as macrorregiões. Das 23.251 equipes de saúde bucal (ESB) no Sistema Único de Saúde, 17.513 (75,3%) participaram deste estudo. Pesquisadores treinados observaram a estrutura dos serviços de saúde e determinaram a presença e a existência de uma quantidade suficiente de 36 instrumentais odontológicos. A pontuação de cada serviço de saúde bucal foi determinada pela soma do número de instrumentos dentários presentes em quantidade suficiente (0 a 36). As medidas de tendência central e de variabilidade desse escore foram comparadas com as características organizacionais dos serviços e de acordo com a macrorregião brasileira. Nenhum instrumental foi encontrado em todos os serviços avaliados. Os instrumentos básicos, cirúrgicos e restauradores foram os mais frequentemente encontrados. Os instrumentos periodontais, endodônticos e para realização de prótese exibiram as percentagens mais baixas. O número médio e mediano de instrumentos dentários foi maior para as equipes que operavam em mais turnos, aqueles com um técnico em saúde bucal e aqueles nas regiões Sul e Sudeste. Os serviços de saúde bucal estavam equipados com instrumentos básicos, cirúrgicos e restauradores. Os instrumentos indicados para diagnóstico periodontal, cuidados de emergência e reabilitação com próteses dentárias foram menos frequentemente encontrados nesses serviços. As piores condições de infra-estrutura existiam nos ESB com as piores formas de organização de cuidados e em regiões com maiores problemas sociais.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - CNPq) for the support received (307617/2015- 7), Minas Gerais Research Support Foundation (FAPEMIG - process numbers - APQ-01218-15 and PPM-00148-17), Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) and also extend their thanks to the Pró-Reitoria de Pesquisa - UFMG.

References

1. Pucca Jr. GA, Gabriel M, de Araujo ME, de Almeida FC. Ten years of a national oral health policy in Brazil: innovation, boldness, and numerous challenges. J Dent Res 2015;94:1333-1337.

2. Mendes EV. [Health care networks]. Cien Saude Colet 2010;15:2297-2305.

3. PMAQ Segundo Ciclo. PMAQ Segundo Ciclo [Internet]. 2013 Janeiro 15. Available from: http://dab.saude.gov.br/portaldab/ape_pmaq. php?conteudo=2_ciclo.

4. Scholz S, Ngoli B, Flessa S. Rapid assessment of infrastructure of primary health care facilities - a relevant instrument for health care systems management. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:183.

5. Kondo KK, Damberg CL, Mendelson A, Motu’apuaka M, Freeman M, O’Neil M, et al. Implementation processes and pay for performance in healthcare: A systematic review. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:61-69. 6. World Health Organization. Core components for infection prevention

and control programmes [Internet]. 2008 June 26. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s16342e/s16342e.pdf. 7. Donabedian A. The quality of care: how can it be assessed? JAMA 1988;

260: 1743-1748.

8. Kringos DS, Boerma WG, Bourgueil Y, Cartier T, Hasvold T, Hutchinson A, et al. The European primary care monitor: structure, process and outcome indicators. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:81.

9. Goetz K, Campbell SM, Broge B, Brodowski M, Wensing M, Szecsenyi J. Effectiveness of a quality management program in dental care practices. BMC Oral Health 2014;14:41.

J. Lopes et al.

11. Domingos CM, Nunes Ede F, Carvalho BG, Mendonça Fde F. [Legislation on primary care in Brazilian Unified National Health System: document analysis]. Cad Saude Publica. 2016;32:e00181314.

12. Roncalli AG, Sheiham A, Tsakos G, Watt RG. Socially unequal improvements in dental caries levels in Brazilian adolescents between 2003 and 2010. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2015;43:317-324. 13. Wasserstein R, Lazar NA. The ASA´s statement on p-values: context,

process, and purpose. Am Statist 2016.70:129-133.

14. Pruksapong M, MacEntee MI. Quality of oral health services in residential care: towards an evaluation framework. Gerodontol 2007;24:224-230.

15. Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1966. Milbank Q 2005;83:691-729.

16. Nickel DA, Lima FG, Bidigaray da Silva B. [Dental care models in Brazil]. Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24:241-246.

17. Cunha MA, Lino PA, Santos TR, Vasconcelos M, Lucas SD, Abreu MH. A 15-year time-series study of tooth extraction in Brazil. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:e1924.

18. Pasarin MI, Berra S, Gonzalez A, Segura A, Tebe C, Garcia-Altes A, et al. Evaluation of primary care: The “Primary Care Assessment Tools - Facility version” for the Spanish health system. Gac Sanit 2013;27:12-18.

19. Esteves RS, Mambrini JV, Oliveira AC, Abreu MH. Performance of primary dental care services: an ecological study in a large Brazilian city. ScientificWorldJournal 2013;2013:176589.

20. Garcia RI, Compton R, Dietrich T. Risk assessment and periodontal prevention in primary care. Periodontol 2000 2016;71:10-21. 21. Souza JG, Martins AM. [Dental pain and associated factors in Brazilian

preschoolers]. Rev Paul Pediatr 2016 34:336-342.

22. Godoi H, Mello AL, Caetano JC. [An oral health care network organized by large municipalities in Santa Catarina State, Brazil]. Cad Saude Publica 2014;30:318-332.

23. dos Reis CMR, da Matta-Machado ATG, do Amaral JHL, Werneck MAF, de Abreu M. Describing the primary care actions of oral health teams in Brazil. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:667-678.

24. Bailit HL, Beazoglou TJ, DeVitto J, McGowan T, Myne-Joslin V. Impact of dental therapists on productivity and finances: I. Literature review. J Dent Educ 2012;76 (8):1061-1067.

25. Nash DA. Adding dental therapists to the health care team to improve access to oral health care for children. Acad Pediatr 2009;9:446-451. 26. Martinez J. Assessing quality, outcome and performance management.

World Health Organization. [Internet]. Available from: http://www. who.int/hrh/documents/en/Assessing_quality.pdf?ua=1. Latest Access: May 28, 2018.

27. Grun RE. Monitoring and Evaluating Projects: A step-by-step Primer on Monitoring, Benchmarking, and Impact Evaluation. The World Bank. [Internet]. Available from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/ bitstream/handle/10986/13640/3898300Impact01ual0REPLACEMENT0 FILE.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Latest Access: May 28, 2018. 28. The World Bank. Conducting quality impact evaluations under budget,

time and data constraints. [Internet]. Available from http://lnweb90. worldbank.org/oed/oeddoclib.nsf/DocUNIDViewForJavaSearch/757A 5CC0BAE22558852571770059D89C/$file/conduct_qual_impact.pdf. Latest Access: May 28, 2018.