In the report, we suggest two main ways of identifying what could be remote and rural areas of Scotland. However, population decline in remote and rural areas has not been offset by migration. The long-term success of the scheme will be assessed based on its potential to contribute to strategic mitigation in remote and rural areas facing depopulation.

All three schemes will be enhanced with complementary initiatives to support integration and settlement in remote and rural areas. The chapter discusses different approaches to identify which remote and rural areas can participate in the scheme.

1 Population Trends in

Remote and Rural Areas

Population Trends in Remote and Rural Areas

- Patterns of Population Change at the Local Level

- Classifying remote rural and sparsely population areas

- Population trends

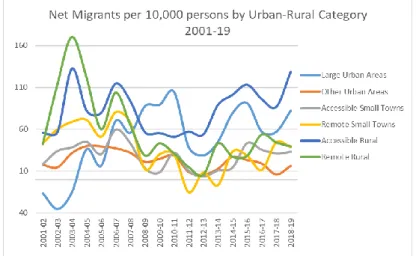

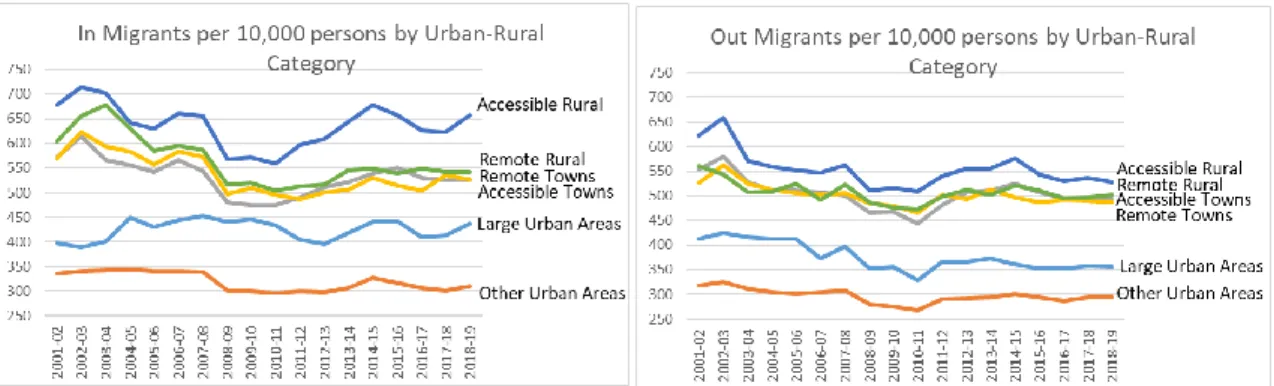

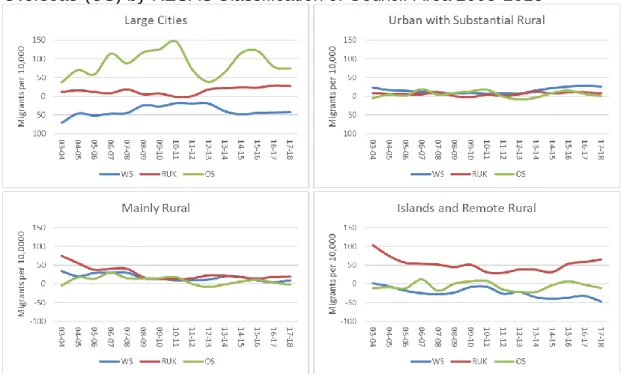

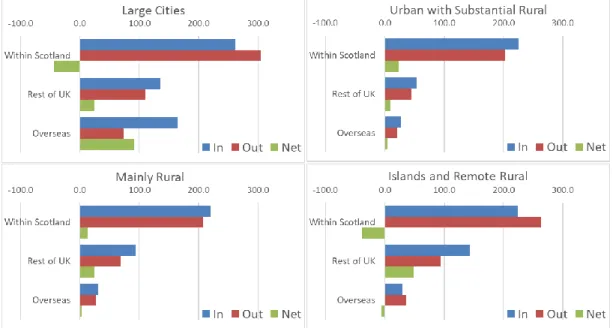

- Migration trends

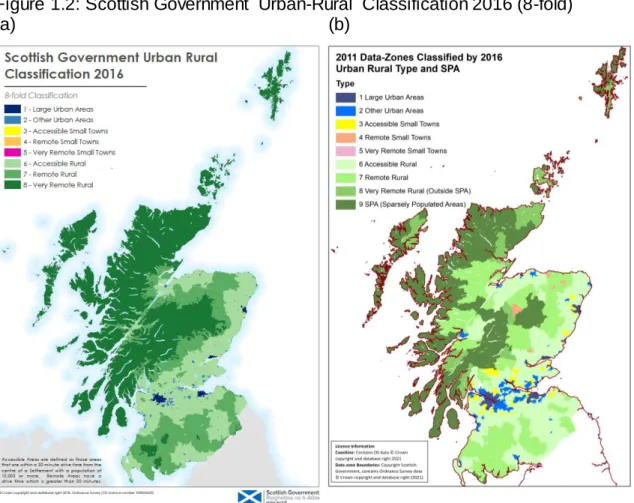

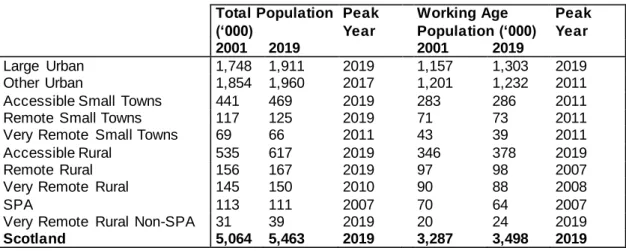

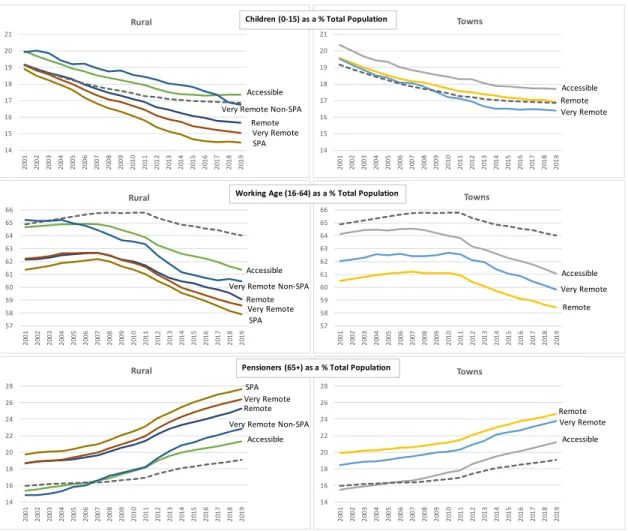

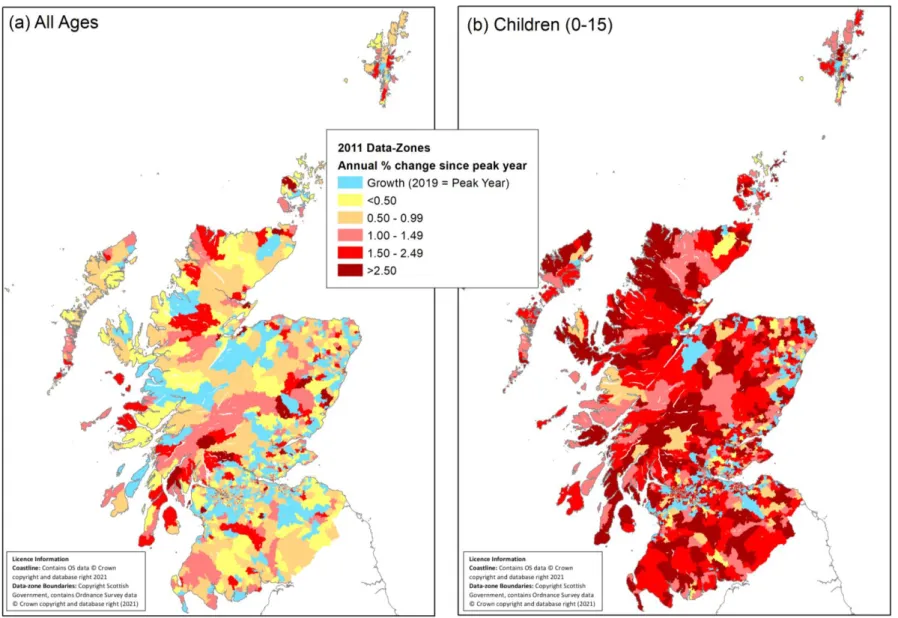

The specific demographic challenges faced by remote and rural areas can be illustrated in more detail by an analysis of the NRS Small Area Population Estimates (SAPE). Less than 10% of the total population lives in remote and very remote rural and small town data zones. Note: The table rows are a combination of the Scottish Government's 8-way urban/rural classification and the James Hutton Institute's SPA classification.

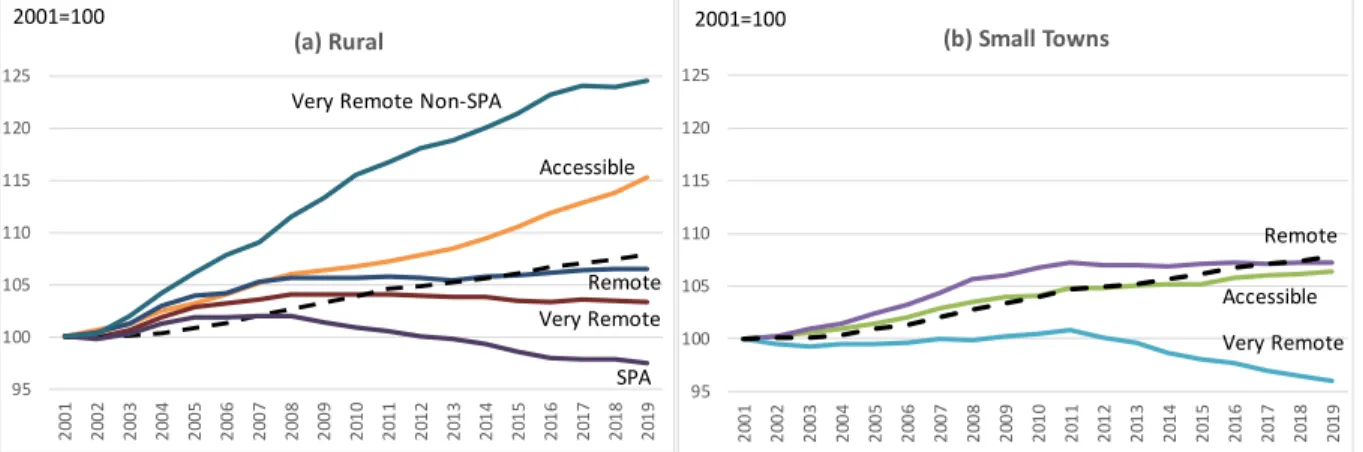

Accessible rural areas and the non-SPA proportion of very remote rural areas were both close to the Scottish average at the start of the period, but diverged steadily, so that in 2019 they were around 2.5% and 3.5%. During the first years of the century, it was remote and accessible rural areas that had the most.

2 Economic and Social Context

Economic and Social Context

- Employment Patterns in Remote Rural Scotland

- Incomes

- Social impacts

- Identifying designated areas

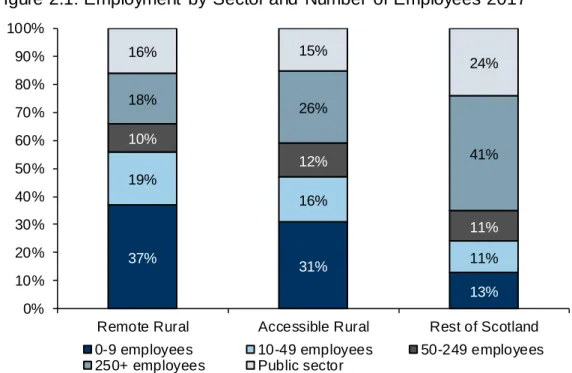

Nevertheless, people in remote rural areas tend to be more economically active than those in the rest of Scotland, albeit by a small margin. The self-employed account for 23% of employment in remote rural areas, 18% in accessible rural areas and just 11% in the rest of Scotland. In contrast, 18% of workers in remote rural areas are small employers and self-employed.

Unregistered businesses are likely to be relatively small and therefore disproportionately located in remote rural areas. It is also worth noting that remote rural areas have a significantly smaller share of employment (16%) in the public sector than is the case in the rest of. However, total employment in food and accommodation is almost the same as that in agriculture in registered businesses in remote rural areas.

This sector therefore represents a smaller proportion of total Scottish employment than agriculture in remote rural areas. Hourly wages in remote rural Scotland are lower than in the rest of the country. Data from the Scottish Household Survey suggests that the distribution of income in remote rural areas is closer to that of the rest of Scotland than it is to Scotland's accessible rural communities.

Our previous analysis shows that full-time work is less common in remote rural areas. As we have already seen, agriculture is one of the two most important industries in remote rural areas. But as we have seen, this work pattern is much less common in remote rural Scotland than in the rest of Scotland.

3 Policy Options

Policy Options

- Selection criteria

- Rights and conditions of stay

- Options

- Designing a Pilot Scheme

- Evaluating the Scheme

This may increase the likelihood that entrants to the scheme will settle in the host area. Participants enjoy extended rights from the outset – in the case of the Canadian scheme, similar to. However, as noted in Chapter 2, remote and rural areas will benefit most where migrants work and live in the designated area.

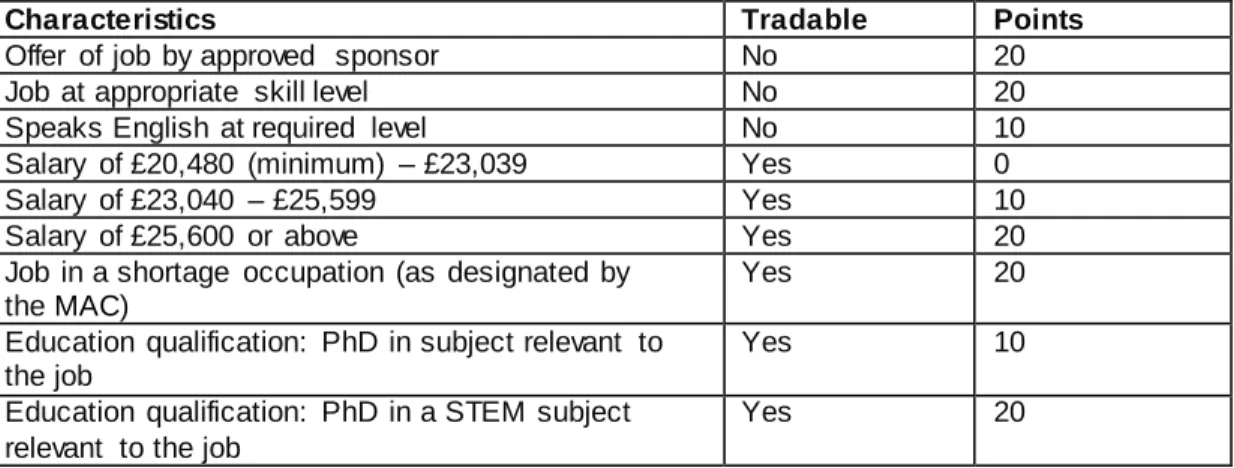

Alternatively, residence in a particular area is encouraged by designing the scheme in a way that increases the likelihood of residence in the area in question. We note that the points required to participate in the scheme would not be tradable, so strictly speaking it would be a threshold scheme (participants must meet a number of conditions to enter) rather than a points-based system. In order to maximize the benefits of this scheme for remote and rural areas, we suggest that the scheme should either encourage or require that entrants and their families also reside in a designated area.

For this reason, this route should build in incentives or requirements to stay in the designated area. This is based on the Manitoba Provincial Nominee Program within the Canadian immigration system, previously analyzed in the second EAG report. The first step in developing such a program would be to identify designated areas to participate in the program (see Chapter 2).

Second, employers with vacancies in occupations identified in the strategic mitigation plan could join the scheme. As discussed in Chapter 2, it would be most beneficial for local areas if participants both work and live in a particular area. It is clear that the RRMS could also include a requirement to reside in a designated area, although this would face the kinds of enforcement challenges described in the discussion of option (b), the Scottish visa.

In addition, the pilot scheme could incorporate the possibility of adjusting the criteria and points according to the number of applicants. An appropriate time frame for determining whether scheme participants are likely to settle in a particular area may be a period of 4 or 5 years.

4 Integration and Settlement

Integration and Settlement

- Integration in remote and rural areas

- Employment and employers

- Language learning and ESOL provision

This has been recognized in Scotland through the development of the New Scots Refugee Integration Strategy, much of which has been implemented in rural settings. A first and crucial stage in this could be a package of information and support, both before and on arrival, to ensure that potential migrants are well aware of the characteristics, opportunities and challenges offered by the area to which they are coming. plan to move. Detailed information on housing, schools, health and social services, benefit entitlements and leisure facilities could be made available to applicants as part of the selection process.

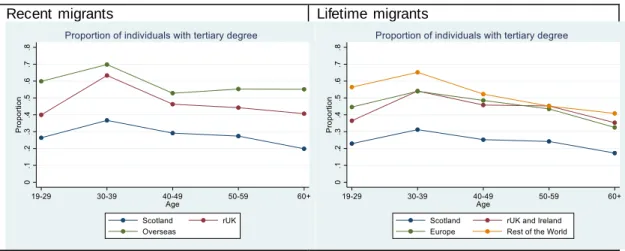

The following groups are distinguished: non-migrants to Scotland, migrants from the rest of the UK and from abroad for recent migrants; the population born in Scotland (83%), migrants from the rest of the UK and Ireland (10%), from continental Europe (2.8%) and from the rest of the world (3.7%) for lifelong migrants. Therefore, regardless of the exact parameters of RRMS, planning for the provision of English to speakers of other countries should also be considered. The ring-fencing of ESOL budgets in Scotland since 2012 has protected this provision from some of the more severe cuts seen in other parts of the UK, but funding has nevertheless fallen in real terms and the impacts of changing governance and funding streams since 2019 are still unknown.

Such an approach is also useful in understanding, a priori, that many of the more negative experiences and barriers or disincentives to settlement that migrants face are also problems for the wider local population. Such future planning should also pay attention to preparing public opinion, laying the foundations for positive community relations and countering a negative politicization of migration, which may have had slightly less traction in Scotland than parts of other parts of the UK, but undoubtedly contributed to the negative. perceptions and fears of migration in Scotland too. In the context of an RRMS, similar work would need to be done in advance so that host communities are aware of the specific issues that the RRMS seeks to mitigate in their area, and the benefits and advantages that the program can bring as the more immediate ones as well as in the immediate ones. long term.

Making family migration and longer-term settlement a specific objective of the RRMS is likely to be helpful in this regard. Studies of rural migration in many parts of Europe have shown that opportunities for family migration and migrants' perceptions of the prospects for their children in the new environment are essential to decisions about longer-term residence. Of the three proposed approaches, the partnership scheme would have particular advantages in this regard, particularly if partners, including local community groups and representatives, are involved from the outset in thinking about ways to make available locally specific 'cultural, historical and civic knowledge' for help, migrants adapt to the host society',54 and develop flexible approaches to facilitate the forging of local connections and two-way learning processes.

3 References

25 Expert Advisory Group on Migration and Population (2019) Immigration policy and demographic change in Scotland: learning from Australia, Canada and continental Europe, available at:. 30 SSAMIS (2016) 'Second interim report: Living and working in Scotland:. employment, housing, family and community', pp. 2020) 'Case studies of island repopulation initiatives', Rural Policy Centre, SRUC, pp. 41 Flynn and Kay (2017) 'Migrants' experiences of material and emotional security in rural Scotland: Implications for long-term settlement' Journal of Rural Studies p. 2012) ‘Border crossings: migration, belonging/non-belonging in rural Scotland’, in Hedberg.

Translocal countryside: mobility and connectivity in European rural spaces. 2017) 'Migrants' experiences of material and emotional security in rural Scotland: implications for long-term settlement', Journal of Rural Studies SSAMIS (2016) 'Interim Report January 2016', p. Migrants and Language Learning in Aberdeen/shire’, available at https://www.gla.ac.uk/media/Media_597469_smxx.pdf. 2012) ‘Border crossings: migration, belonging/non-belonging in rural Scotland’, in Hedberg. A Pilot Peer Education Project for New Scots' Social and Language Integration', available at: www.scottishrefugeecouncil.org.uk/wp- content/uploads/2019/10/Sharing_Lives_Sharing__Languages_REPORT.pdf. 46 The Migration Matters Scotland database developed and hosted by COSLA also has a section dedicated to language learning and ESOL which provides links to a variety of case studies and resources, available at:.

50 British Future (2018) National Conversation on Immigration: final report, available at: http://www.britishfuture.org/publication/national-conversation-immigration-final-report/. 2010) Capitalizing on Rural Migrants: Migrant Employment Strategies and Socio-Economic Implications for Rural Labor Markets. Schneider (2010) Context theory of comparative integration:. participation and belonging in various new European cities. immigrants in rural communities: The challenge of integration.