In this study we find three different types of value pairs, each with different types of carbon footprints and willingness to take pro-environmental actions. However, research has also shown that positive pro-environmental attitudes (Valkila & Saari, 2012), perceptions (Bleys, Defloor, Van Ootegem, & Verhofstadt, 2018), knowledge and intentions do not always lead to pro-environmental behavior (see Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002). However, despite extensive research on the relationship between values and pro-environmental actions, these studies tend to examine a single pro-environmental action at a time, whereas studies on the relationship between values and environmental lifestyles (e.g. footprint of carbon) as a whole. are few, if any, non-existent.

For this reason, this study examines the relationship between values and carbon footprint - a proxy measure for pro-environmental lifestyle. These carbon footprints are then compared to participants' core values and pro-environmental attitudes, measured through questionnaires. This comparison provides insight into how consistent individuals with pro-environmental values are in their pro-environmental behavior and how values, actions and willingness to take action are interrelated.

Indeed, numerous studies have shown that individuals with bioshperic and altruistic values are more likely to engage in environmentally friendly behavior than individuals with hedonic or selfish values (Steg et al., 2014). However, as already mentioned, these studies tend to examine only one pro-environmental behavior at a time. Therefore, when studying the relationships between values and environmentally friendly behaviors, it is largely advisable and useful to consider that individuals can do both at the same time.

Therefore, this study examines the relationship between values, carbon footprint, and willingness to take pro-environmental actions and how these are related to the feedback effect, spillover effect, and goal-setting theory.

Method

Participants were asked to rate each of the 16 items using a nine-point Likert scale (-1 = contrary to my values to 7 = of supreme importance). We preliminarily performed an exploratory factor analysis and found that all items grouped under the four factors as expected (Steg et al. 2014), except for item A2 which loaded on the biospheric factor instead of the altruistic factor (cf. Since the reliability of the altruistic factor was increased by excluding item A2, and for theoretical importance, we removed variable A2 from the altruistic factor from further analyzes (see Table 1).

As shown in Table 3, participants' willingness to undertake mitigation action was measured using a 17-item questionnaire, adopted from literature (Tolppanen et al., 2020). Participants' carbon footprint was measured using an online tool, developed by the Finnish Environmental Institute SYKE (see SYKE, 2019). The tool is based on the ENVIMAT model and a wide range of literature (see Salo et al., 2019) and can therefore be considered a reliable assessment tool to measure an individual's carbon footprint.

For example, in the case of apartments, in addition to the question about the type of building and the size of the apartment, it asks what type of heating you use and how much electricity you use annually. For this research, participants answered questions as homework to determine what their carbon footprint was. First, LPA (latent profile analysis) was used to classify clusters based on participants' data on the four value types, using a robust maximum likelihood estimator with full information maximum likelihood to handle missing data in Mplus 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén, 2009).

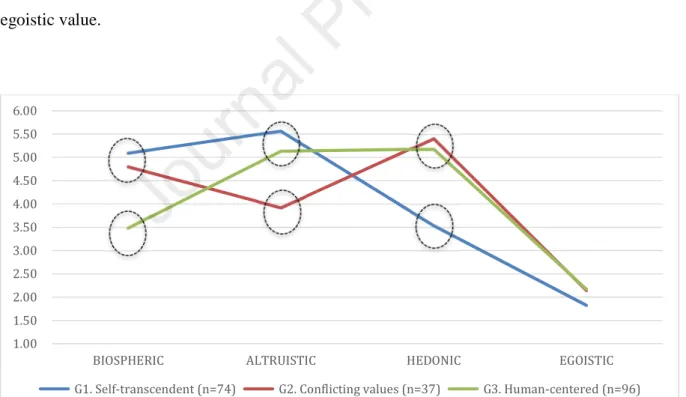

However, a closer analysis showed that the individuals in the Low values and High values groups were quite homogeneous, when examining how they ranked the four different values. For this reason, a second grouping was made in which primary values were the basis of the grouping. That is, individuals were divided into four groups based on which value they ranked highest, or as their primary value.

Individuals' primary values were determined by examining which of the four values (see Tables 1 and 2) they gave the highest mean score to. However, when we compared primary values with carbon footprints and willingness to take mitigating actions, no meaningful results were found. This clustering showed meaningful results when compared to individuals' ecological footprints and willingness to take mitigating actions.

Results

In terms of carbon footprint, most differences were found between the self-transcendence group and the human-centered group, the former showing a lower carbon footprint than the latter (see Table 5). The results also show that the conflicting value group and the human-centered group have differences in carbon footprint, the former showing a lower carbon footprint than the latter. Also, when this new group was compared with the group of human-centered values in relation to CFPs, significant differences were seen in most of the main categories, except for the category of living and transportation (see Table 6).

Looking at the group of human-centered values, we see that the group has large carbon footprints in most categories. This is seen in the way those in the questionable values group have a low carbon footprint even though they have hedonic values as a primary or secondary value. One explanation for why hedonic values do not appear to override biospheric values in the set of controversial values may be due to the decision-making process involved in climate change.

Combined with the notion that people tend to be short-sighted and act on the "spur of the moment," hedonic values often play an important role in decision-making. However, in the context of climate change mitigation, it is often the actions not taken in the moment that have the greatest impact on individuals' carbon footprint. First, it is possible that individuals are not truly aware of the social consequences of climate change, which would explain why those with altruistic values do not perceive climate change to threaten their values.

Since climate change will not have such strong societal effects in Finland as in some other parts of the world (Mendelsohn, Dinar, & Williams, 2006), the Finns participating in this study may not perceive climate change as a threat to their altruistic values. If this explanation holds true, the relationship between altruistic values and low-carbon lifestyles may differ in different parts of the world, as the societal impacts of climate change differ from country to country. On the one hand, the results clearly show that the self-transcendence group has the highest willingness to take mitigation actions while also having a low carbon footprint.

On the other hand, they have a similar environmental footprint to the controversial values group, although they have a significantly greater willingness to act. One of the limitations of this study is that it was conducted among university students, meaning that the participants are a somewhat homogeneous group, with similar academic backgrounds, academic interests and, presumably, disposable income levels. That said, in this study we did not measure the students' disposable income, but assumed that they are representative of Finnish students in general (see Potila et al., 2017).

Especially in a group with controversial values, it would be interesting to know how much the low-carbon lifestyle is influenced by values and how much by friends and family. Based on the study's findings and limitations, future studies should examine how value pairs affect carbon footprint in the general population.

Conclusion

However, in some cases the opposite may be true, as a more expensive product may have a lower carbon footprint than a cheaper one. Furthermore, the questionnaire asked to estimate expenses within the past year, but although individuals would be able to give accurate answers, the expenses in the previous year may not fully represent their normal lifestyle. Future studies should also examine how well the self-report carbon footprint calculations represent actual carbon footprints.

The results of such findings can provide further insight into how individuals with different values can be encouraged to take mitigating action to combat climate change. The Geographical Distribution and Correlates of Pro-Environmental Attitudes and Behavior in an Urban Region, Energies. The dragons of inaction: Psychological barriers limiting climate change mitigation and adaptation. consumption choices: Options and barriers to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Carbon Footprint Estimates Based on Spatial Consumption - A Review of Recent Developments in the Field, Journal of Cleaner Production. An IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and associated global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development and efforts to eradicate poverty [V. Think about the gap: Why people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior.

It can't hurt, it can help: examining spillover effects from the intentional adoption of a new pro-environmental behavior. Psychological barriers to energy conservation behavior: The role of worldviews and climate change risk perception. The Rebound Effect: an evaluation of the evidence for economy-wide energy savings from energy efficiency improvements.

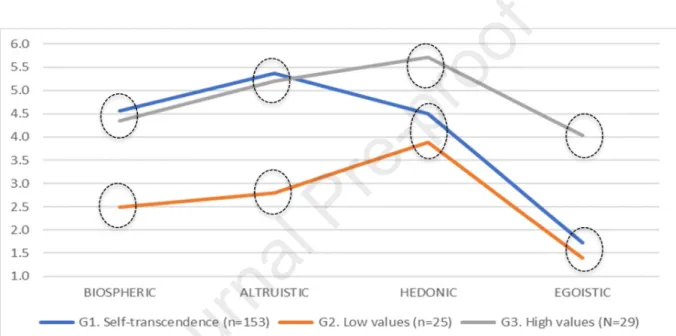

An integrated framework for encouraging pro-environmental behavior: The role of values, situational factors, and goals. Also, as shown in Figure 1B, profiles in the three-profile solution indicated significant group differences in terms of four values. As seen in Figure 1B, most of the participants belonged to the self-transcendence group (n=153) with high scores in biospheric and altruistic values, while having low scores in hedonic and egoistic values.

In addition, while both groups indicated significant group differences in all four values, the high values group and the low values group indicated a similar pattern in terms of the ranking of values, which. With these three clusters, we tested group differences in terms of willingness to take mitigation actions and carbon footprint.