We show that a temporary negative labor supply shock due to childbirth can create a wage trap and a permanent gender wage gap. Conversely, temporary maternal wage subsidies (preferably in the form of income tax credits) are not only useful for escaping the wage trap, but also for speeding up recovery and reducing the child penalty when the labor supply shock is small enough to avoid salary falls. We show that a temporary negative shock to labor supply (or more generally effort) due to childbirth can create a wage trap and a permanent divergence in labor earnings between otherwise identical individuals who did not experience the negative shock.

These subsidies are useful for exiting the wage trap and also for speeding up recovery and reducing the child penalty when the shock in labor supply is small enough to avoid the wage fall. This sign strongly depends on Kimball's coefficient of relative prudence PuR[x] =−xu000[x]/u00[x], the relative risk aversion coefficient Ru[x] and %b00ee (i.e. the comparison between the third derivatives of u [.] and v[.]).3.

Wage rate

Labor income

To study the existence and possible diversity of steady states e?, we could keep a fairly general specification and introduce assumptions about e] and/or ∆00[e].9 But instead of focusing on the properties ∆[.] think , that a better understanding of mothers. They illustrate the existence and importance of wage and income traps and can be used to examine potential policies to mitigate or eradicate child punishment.

Dynamics, steady-states and convergence

To summarize, when ϕ[.] is a monotonic increasing function of the wage rate, the income dynamics is monotonic (increasing or decreasing depending on the initial level y0). Assuming α= 0 so that et = bet, and proceeding as in Section 3 shows that the effort dynamics et and the payoff rateswt+1 for et−1 >0 and wt>0 are represented by. To get a complete specification; now assume that ψ[.] is given by the following sigmo¨ıd function (convex and then concave).

Consequently: if e−1 < e∗a then the path of e is increasing and converges to e∗a; if e∗a < e−1 < e∗b the dynamics is decreasing and converges to e∗a; if e∗b < e−1 < e∗c the dynamics is increasing and converges to e∗c; finally if e−1 > e∗c the dynamics is decreasing and converges to e∗c. Turning to panel (b), it shows that the function expressing the wage dynamics, Ω[.], is also increasing. As for effort, the time path of wage rates depends on the initial level of sajw0 and the convergence process is similar to that of et.

Remember that this dynamic, specifically the existence of three stable states and the associated trap at the bottom, is obtained from our illustration. Given this, one might suspect that the pattern we obtain (with three stable states and a trap) is due to the sigmo¨ıd (convex and then concave) specification of ψ[.] and that the monotonic dynamics requires an increasing specification of ϕ[.]. To illustrate this, we use a utility function that yields an effort level that is not monotonic in w and a functional form ψ[.] that is strictly convex; see Appendix A.1.

In addition, we can draw lessons for policy design to mitigate the gender gap in income and the child-related penalty.

![Figure 1: The different dynamics of our Illustration A. Representation of ∆[.], Ω[.] and Φ[.]](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/14378906.3021439/15.892.112.792.112.720/figure-different-dynamics-illustration-representation-ω-φ.webp)

Motherhood and child penalties

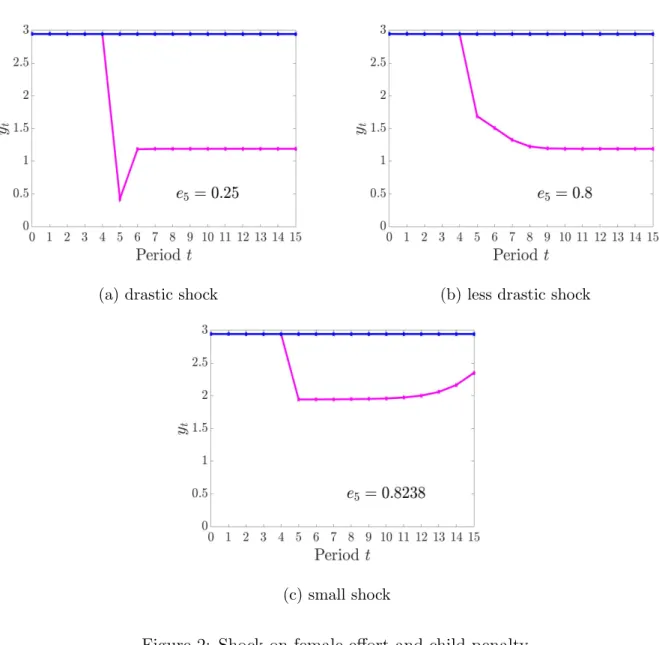

Assuming assortative matching in a pair, we can imagine two workers as spouses.14 In each of the panels in Figure 2, we present the path of earnings in 15 periods with the same parameter values as in the previous figures. This is in line with the definition used in the empirical literature; see Kleven et al. We have now shown that, given the magnitude of the shock, our model yields different earnings paths and the corresponding penalty for the child that match those reported in the empirical literature.

In the following periods, the effort and earnings increase but the mother remains trapped in the low steady state. As a result, her income will continue to decline in the following periods and eventually reach the low steady state. Now the shock is small enough to ensure that e gt; e∗b, so the dynamic converges to the high steady state.

Our illustration shows that a negative shock in effort, such as that caused by motherhood via the labor supply, could be enough to activate a negative spiral of low wages leading to a sustained wage fall. In the case of assortment-matched couples, the maternity trap may be highly relevant, despite the fact that women are a priori comparable to their husbands in terms of future income prospects. First, as Kleven et al. 2019a) pointed out, the prevailing social norms in the relevant social group might amplify the effects of motherhood.

Finally, a third source of heterogeneity is mothers' socioeconomic status, which we discuss in the next section.

Socioeconomic status

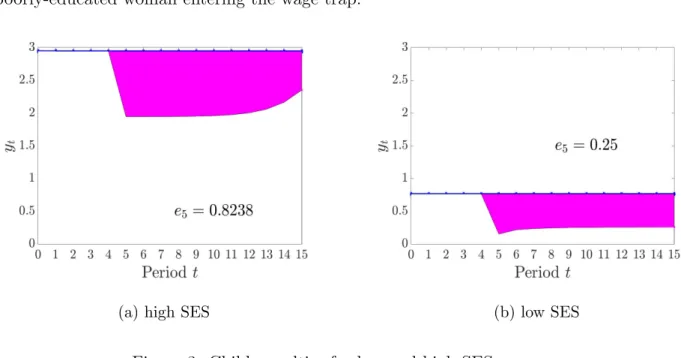

Following this interpretation, the model predicts that women with low SES are more likely to enter the wage trap and experience significant income losses. They use French administrative data from 2005 to 2015 and document the heterogeneity of the consequences of childbirth, along with the distribution of wages before childbirth. However, the fact that low SES women are more likely to enter the wage trap does not necessarily mean that they also suffer the highest child penalty.

Indeed, our model can also accommodate the situation in which earnings losses from motherhood are higher for high SES mothers. This occurs when the decline in effort and the wage rate after motherhood is sufficiently significant for highly educated mothers that slow and incomplete convergence to the "high" steady state implies losses greater than those experienced by a woman with poor education entering the wage trap. Children's sentences for high and low SES are shown in Figure 3, which is constructed as

With regard to the high SES, we consider two partners who are initially in the high equilibrium e?c. In Figure 3, in each of the panels, the child penalty, which corresponds to the total income loss (the sum of annual losses) due to motherhood, is represented by the pink area obtained by dividing the difference between the income trajectories of the two. integrate partners. This shows that while the low SES women are trapped in the low stable state, their overall child sentence is lower than for the highly educated women, even though they remain on a trajectory that would eventually converge to the high stable state (which they do not ). t range due to slow convergence speed).16.

We now consider family policies commonly used to increase mothers' attachment to the labor market and to reduce gender gaps in employment and earnings.

Ineffective and potentially backfiring policies

Our analysis only suggests that this negative effect should be offset by its positive effects on the well-being of mothers and children (which are not accounted for in our model), especially when determining the appropriate length of leave. Cash transfers to mothers with young children are very common in developing countries, where they tend to target the poorest families where children face the greatest challenges. In OECD countries, cash transfers often depend on wealth status and in this case their main objective is redistribution.

But cash transfers can also be unconditional and provided to parents for a specified period of time (months or even years), regardless of their income. Their study examines the effects of maternity leave on unemployment and wages in a labor market search and matching model. Crucial factors in their model are the bargaining power of women and the value of the leave for the employee in relation to the employer.

19 Child-related cash transfers to families with children include child allowances and public income support payments which may depend on the child's age and/or family size and are sometimes means-tested. In Appendix A.4, we derive the dynamics of effort, wages and earnings when cash transfers are provided. We show that they amplify the effects of the motherhood shock due to the negative sign of the derivatives ∂∆M/∂Mt and ∂ΩM/∂Mt (see A.8 and A.10, respectively).

Note that, as previously noted for maternity leave, our argument does not imply that remittances are generally a bad policy.

Potentially effective policies

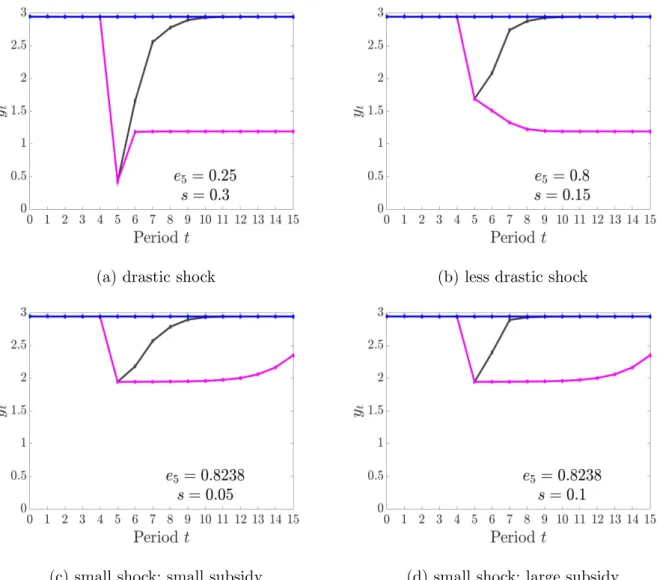

Our analysis simply shows that the negative impact on wages and labor income must be traded off against its positive effect on mothers' and children's welfare (not accounted for in our model). Intuitively, by encouraging mothers' effort, subsidies to mothers' wages mitigate the loss in human capital accumulation and activate a positive spiral of increasing effort and increasing wage rates that narrows the gender gap in earnings in the short run with positive spillover effects on the long term. run. 20 A large literature has examined the labor supply effects of EITC in the US; see Nichols and Rothstein (2016) for a survey.

Our simulations show that a temporary wage subsidy for mothers, given immediately after maternity leave, is highly effective not only in reducing the risk of a wage trap, but also in mitigating the child penalty for women, the income pathway of which converges towards the high level. steady state. We now discuss two other policies that have a more indirect effect on maternal labor supply but may still be effective. Provision of outdoor childcare and/or subsidies may reduce the extent and duration of the shock and possibly reduce mothers' costs of providing effort, again affecting function[1−et].

This can stimulate labor supply and reduce the risk of mothers falling into the wage trap. For example, Lefebvre and Merrigan (2008) find that childcare subsidies for four-year-old children, introduced in Québec in 1997 and combined with greater availability and quality services, increased maternal employment by 8 percentage points and generated 231 extra hours per year. In follow-up work, they find that these beneficial effects on maternal outcomes persist over the long term.25.

On the theoretical side, Barigozzi et al. 2018) have shown that subsidies for formal childcare ease the norm costs (the mother's guild) perceived by mothers who choose a high career path. Among these, the most direct effect on female labor supply is achieved by an EITC subsidy to mothers returning to work after maternity leave. Merrigan, 2008, Child-Care Policy and the Labor Supply of Mothers with Young Children: A Natural Experiment from Canada. Journal of Labor Economics.

Strictly convex specification of ψ[.] and non-monotonic de- sired effort level ϕ[.]

Derivation of equation (18)

Dynamics of the low SES case

Dynamics with cash transfers

Dynamics with a subsidy to mother’s wage rate

![Figure 5: The different dynamics of our Illustration B. Representation of ∆[.], Γ[.] and Φ[.]](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/14378906.3021439/37.892.116.783.224.834/figure-different-dynamics-illustration-b-representation-γ-φ.webp)

![Figure 6: Representation of ∆[.] and Φ[.] as specified by (16)–(19) with parameters α = 0, a = b = 0.65, ε = 0.6, ξ = 1, θ = 0.01 and n = 7.](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123doknet/14378906.3021439/38.892.100.775.141.623/figure-representation-φ-specified-parameters-α-ε-ξ.webp)